Robust Voltage Control in Distribution Networks via CVaR-Based Bayesian Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- This paper enhances the objective function with Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR). In our voltage regulation process, the regulation results are affected by uncertainties (environmental variables, noise, model errors, etc.). In the event of communication failures, applying decision variables derived from a specific load scenario to other scenarios may expose the system to extreme tail risks, resulting in insufficient robustness and vulnerability under high uncertainty. CVaR quantifies the risk measure of the average worst-case loss when the loss exceeds the Value at Risk (VaR) at a given confidence level [11].

- This paper employs Bayesian Evolutionary Optimization (BEO) to address this issue. For Volt/VAR power control issues, the BEO framework dynamically optimizes decision vectors. By constructing a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model to approximate computationally expensive multi-load-scenario power flow calculations, and actively selecting the most promising parameter points for evaluation based on acquisition functions such as Expected Improvement (EI), this approach significantly reduces the number of simulations required to accurately estimate the CVaR risk value. The method ensures optimization accuracy while substantially enhancing search efficiency, ultimately enabling effective solutions to high-dimensional, non-convex CVaR optimization problems with uncertain constraints under a limited computational budget.

2. The Formulation of Volt/VAR Control Rules Optimization

2.1. System Modeling

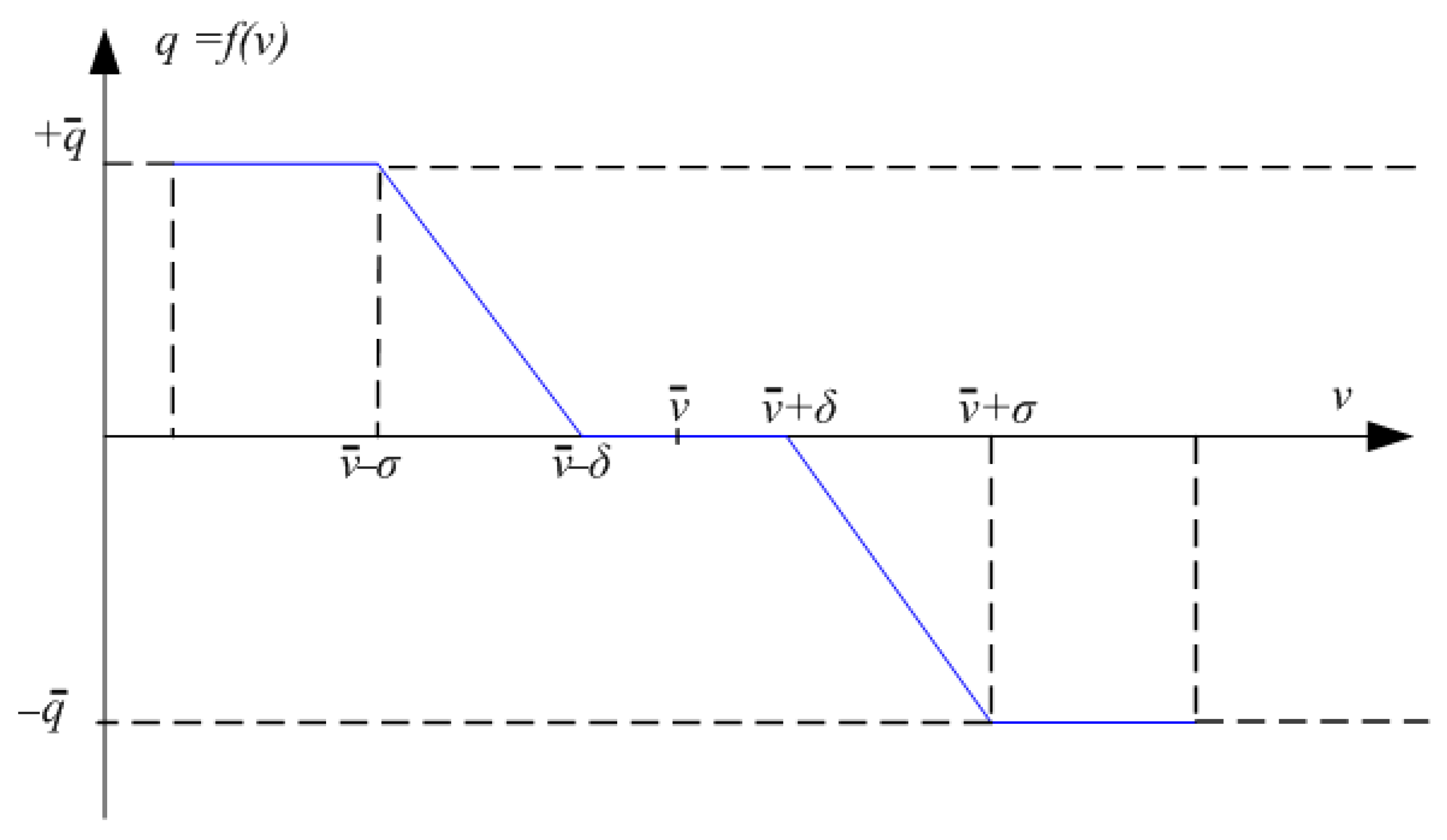

2.2. Volt/VAR Control Rule

3. The Proposed BEO-CVaR

3.1. BEO

3.1.1. Training a GP Surrogate Model

- Initialize the hyperparameters .

- Construct the kernel matrix using the current .

- Compute the current negative marginal log-likelihood (loss).

- Compute the gradients of the loss with respect to in (16).

- Update the hyperparameters using an optimizer (e.g., gradient descent as in (17)).

- Repeat Steps 2–5 until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., the gradient norm is sufficiently small, the maximum number of iterations is reached, or the change in the loss function is negligible).

3.1.2. Constructing and Optimizing the Acquisition Function

- EI: Measures the expected value of improvement of x over (improvement amount weighted by probability).

- UCB: Selects the next point based on the upper confidence bound.where is a parameter controlling the degree of exploration (which can be time-varying or fixed).

- MES: Aims to select an evaluation point x such that, after observing the function value y at this point, the uncertainty about the global maximum is maximally reduced, which can be expressed using conditional entropy as . This reduction in uncertainty is the information gain:where represents the remaining uncertainty about after sampling at candidate point x and obtaining observation y. This expectation is taken over possible values of y (which follows the predictive distribution of the current GP model at point x).

- TS: Samples a function from the GP posterior distribution, and then takes the maximum point on as . No explicit calculation of is required.

3.1.3. Evaluation and Update

3.2. BEO-CVaR Algorithm Framework

| Algorithm 1: BEO-CVaR Framework |

| Input: Variable boundaries , initial sample size , optimization iteration count T, environmental sample count K, risk level Output: Optimal parameters , minimum CVaR 1: Normalize the training data to the range 2: for iteration = 1 to max_iterations T do 3: Normalize training data to the range [0,1] 4: Train a GP model: Use the RBF kernel function from (13); train the model hyperparameters using MLL (neural network gradient method) 5: Construct the acquisition function: Use the acquisition function strategy from Section 3.1, calculate the current optimum as the reference point, and construct the acquisition function 6: Optimize the acquisition function: Acquisition function optimization is performed via multi-start random restarts and random sampling points, using gradient-based optimization methods within the 8-dimensional standardized parameter space, while employing boundary handling and convergence checks to ensure numerical stability 7: Denormalize the candidate point to the original parameter space 8: Evaluate the black-box function at the candidate point: 9: for environment sample = 1 to K do 10: Randomly select a load scenario 11: Calculate power system voltage deviation cost 12: end for 13: Calculate CVaR at risk level 14: Update the training dataset with the new candidate point and its CVaR value 15: Periodically save the optimization progress 16: end for |

4. Experiment and Result Analysis

4.1. Test Case

4.2. Experimental Setting

- Hyperparameter Optimization: The GP kernel hyperparameters are optimized by maximizing the MLL using the L-BFGS-B algorithm. As a quasi-Newton method, this approximates the Hessian matrix to automatically adapt step sizes, eliminating the need for manual tuning of the learning rate and terminating the update when the gradient norm satisfies the convergence tolerance.

- Convergence Strategy: The outer optimization loop employs a fixed evaluation budget ( iterations) rather than an asymptotic convergence threshold. Given the computationally expensive nature of the CVaR objective, this budget strategy ensures a strictly bounded and predictable execution time (approx. 31 min) while sufficiently exploring the design space.

- Acquisition Maximization: To address the non-convexity of the acquisition function, we employ a multi-start optimization strategy. The algorithm generates random samples to identify high-potential regions, which are then used to initialize local gradient-based searches (via L-BFGS-B) to precisely locate the next sampling point.

4.3. Results and Analysis

4.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis and Selection of Risk Parameter

- Under-Protection Region (): At , the algorithm behaves similarly to a risk-neutral expectation minimization. While it achieves a moderate average deviation ( p.u.), it fails to sufficiently penalize extreme violations. Consequently, the system exhibits the highest tail risk ( p.u.), indicating vulnerability to rare but severe load fluctuations.

- Over-Conservatism Region (): As increases to , the optimizer focuses exclusively on the worst of scenarios. This excessive risk aversion leads to “over-regulation,” where inverters adopt aggressive control rules that are suboptimal for the majority of normal scenarios. As a result, the average voltage deviation degrades to p.u. Furthermore, estimating the extreme tail with finite samples introduces higher variance into the GP surrogate, resulting in a slight increase in the measured risk ( p.u.) compared to .

- Optimal Balance (): The value of is identified as the optimal trade-off point. It achieves the global minimum for the average voltage deviation (0.0102 p.u.), which prioritizes and guarantees the highest efficiency under day-to-day nominal conditions. While a marginally lower extreme tail risk is observed at , this gain is minimal and comes at the cost of a significant degradation in average performance. Therefore, is the superior choice, as it robustly constrains the tail risk (0.0478 p.u.) without sacrificing crucial operational efficiency. This indicates that focusing on the worst of scenarios provides sufficient data for the BEO algorithm to learn robust control boundaries without sacrificing performance in nominal states.

4.3.2. Optimization Process and Convergence Analysis

- reaches its peak around the 35th iteration, and then declines rapidly and stabilizes at a low value, indicating early active exploration of high-uncertainty regions and improved model reliability. The delayed convergence of underscores its role as a key parameter requiring careful calibration.

- undergoes a sharp drop around the 10th iteration and quickly converges to a stable value, reflecting the algorithm’s rapid calibration of the overall variation amplitude of the target function in the initial phase (with early emphasis on exploring extreme regions), ultimately determining an appropriate scale.

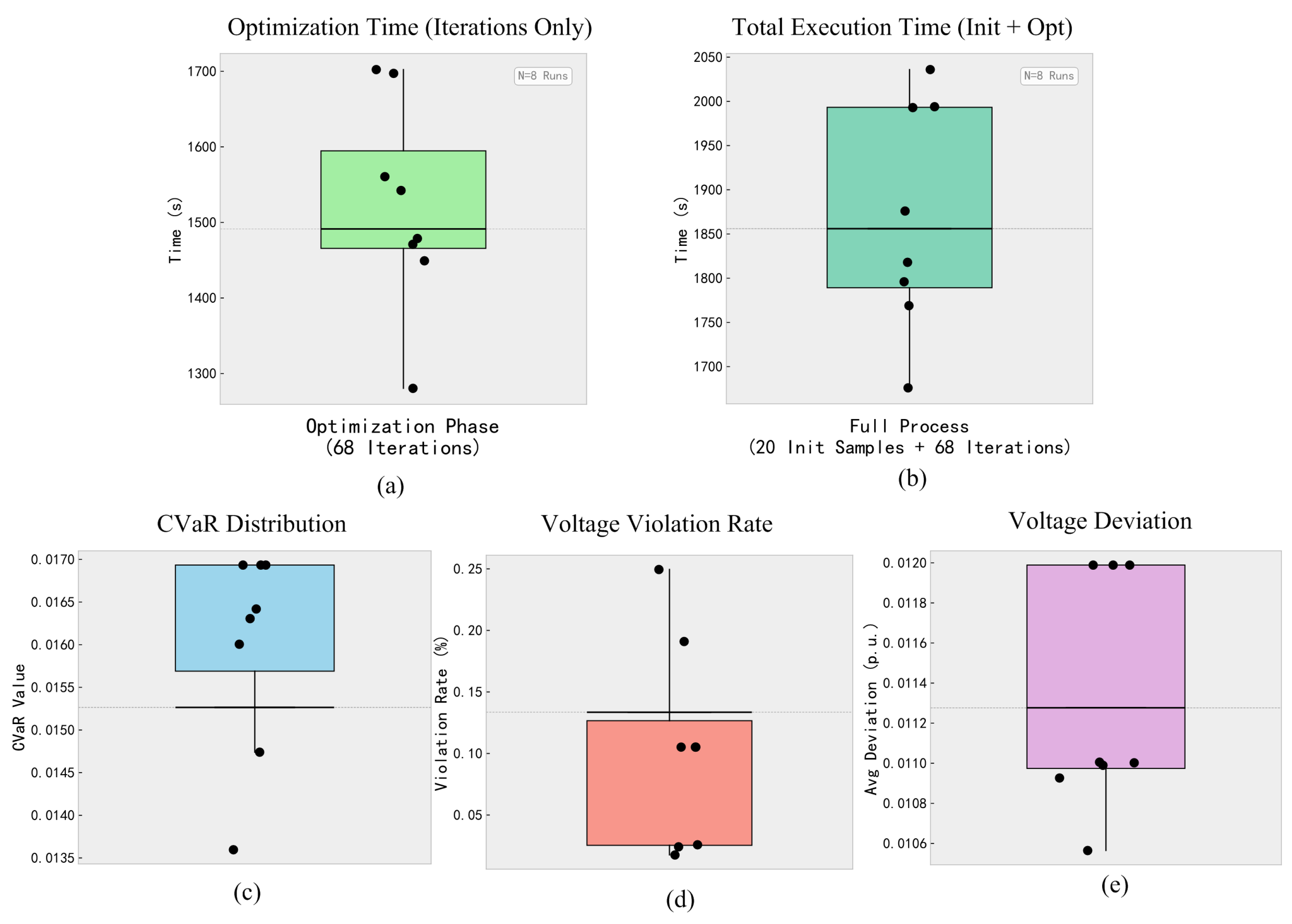

4.3.3. Statistical Reproducibility and Computational Efficiency

4.3.4. Performance Validation on Standard Test Scenarios

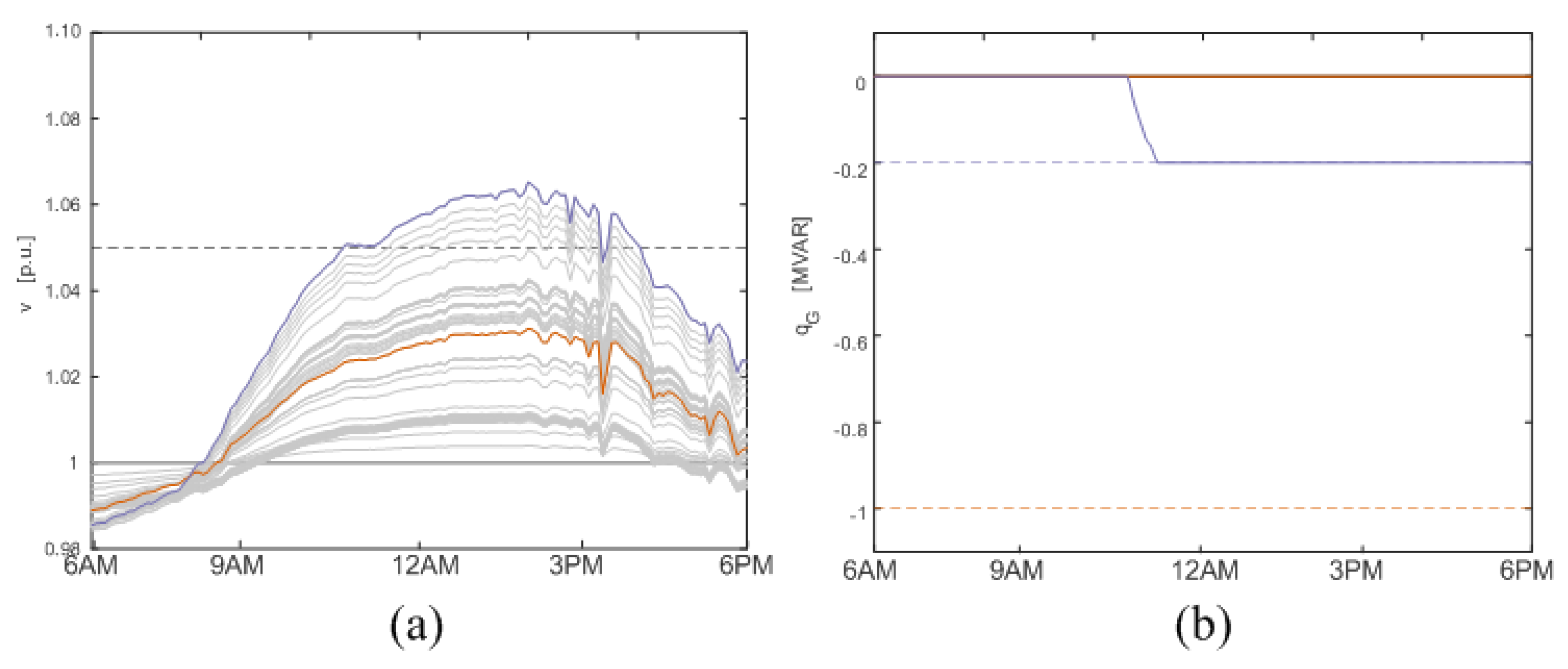

- Strict Safety Compliance: The proposed BEO-CVaR method achieved a remarkably low voltage violation rate of 0.026% (violations occurred in only a negligible fraction of the 8640 scenarios). This demonstrates that the algorithm effectively learned to mitigate tail risks, ensuring that the grid operates within the IEEE 1547 safety limits (≤1.05 p.u.) under almost all uncertainty realizations.

- Coordinated Inverter Response: As shown in the bottom panel of Figure 12, the inverters exhibit a distinct coordinated behavior. The smaller Inverter 2 (Green) operates near its saturation limit to provide baseload reactive support, while the larger Inverter 1 (Orange) dynamically adjusts its output, reaching full saturation only during peak solar generation periods (scenario indices 4000–6000).

4.4. Comparison with Traditional and Meta-Heuristic Strategies

4.4.1. Comparison with Traditional Decentralized Methods

- Uncontrolled Scenario: In the uncontrolled case, the two PV inverters inject active power at a unitary power factor (i.e., zero reactive power). This results in voltage violations, with the magnitude exceeding the 1.05 p.u. upper limit at multiple buses (Figure 13, uncontrolled panel). These overvoltage issues highlight the necessity of reactive power control strategies to maintain grid voltage stability.

- Fully Decentralized Control (Static Feedback): This scenario evaluates the static local feedback law proposed in [2,9,10,19]. The control law relies on purely local measurements. It adjusts reactive power injection based on a predefined control strategy with a reference voltage of 1.0 p.u., a deadband voltage of ±0.01 p.u., a saturation voltage of ±0.04 p.u., and maximum reactive power injections of 1.0 p.u. for one PV inverter and 0.2 p.u. for the other. As shown in Figure 14 (Fully decentralized control (static)), while some buses exhibit improved voltage profiles, violations persist at certain nodes, including generator buses. This indicates that static decentralized control strategies are insufficient for effectively mitigating overvoltage in all cases.

- Fully Decentralized Control (Incremental Feedback): This paper also implements the incremental feedback strategy, which adjusts reactive power iteratively based on local voltage deviation [20,21,22]. The results, depicted in Figure 15, demonstrate that while incremental feedback offers some improvements, it fails to strictly regulate voltages below the 1.05 p.u. threshold. The persistent overvoltage issues at certain nodes underscore the limitations of purely decentralized strategies.

4.4.2. Comparison with Meta-Heuristic Optimization (PSO)

- Superior Robustness in High-Risk Scenarios: While PSO achieves a reasonable overall compliance rate, it struggles significantly under stress. In the high-risk interval (scenarios 4500–6000), PSO exhibits a violation rate of 2.34%. This reveals a critical limitation: standard PSO optimizes for average performance (expectation minimization) and ignores tail risks. In sharp contrast, BEO-CVaR maintains a violation rate of only 0.50% in the same high-stress window—an improvement of nearly 80% over PSO. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the CVaR component, which explicitly penalizes voltage violations in worst-case scenarios, ensuring grid safety even during peak volatility.

- Computational Efficiency: Regarding computational cost, the optimization process for PSO required approximately 54.5 min, whereas BEO-CVaR required only about 31 min. PSO relies on stochastic exploration of the search space by a population, necessitating a large number of function evaluations. Conversely, BEO-CVaR leverages a GP surrogate model to efficiently “learn” the grid behavior, achieving superior convergence with significantly fewer samples. This demonstrates the superior sample efficiency of the Bayesian optimization framework.

4.5. Comparison of Four Acquisition Function Strategies

4.6. Scalability Analysis in Multi-Inverter Scenarios

4.7. Quantitative Analysis of Communication Efficiency and Robustness

4.7.1. Reduction in Mandatory Control Updates

4.7.2. Robustness Against Communication Failures

- Traditional Methods (High Real-Time Dependency): A downlink failure causes the loss of crucial 3 min optimal setpoint dispatches ( updates missed). Inverters, unable to receive these updates, must revert to unoptimized fallback modes.

- BEO-CVaR (Asynchronous Robustness): In contrast, BEO-CVaR transmits a robust Volt/VAR curve, enabling local control execution. Even if communication is severed immediately after the single initial update (losing all subsequent monitoring data), inverters autonomously adjust reactive power based on local voltage.

4.8. Stress Testing Under Extreme Physical Conditions

- High Impedance (Weak Grid): All line impedances (Z) are scaled by a factor of , significantly exacerbating voltage sensitivity to power injections.

- Heavy Loading: The active and reactive load demands are scaled by , pushing the system far beyond its nominal operating point.

- Limited Capacity: The reactive power capacity () of all inverters is reduced to of the nominal value.

- Voltage Profile (Top Panel): It can be observed that, despite severe physical constraints, the vast majority of voltage curves remain within the safety band. Only during the middle period with the most intense PV and load fluctuations (approximately scenarios 3500 to 7500) did a few specific nodes exhibit voltage violations.

- Inverter Response (Bottom Panel): The bottom panel clearly explains the cause of these violations. During the violation periods, both the large-capacity Inverter 1 (orange line) and the small-capacity Inverter 2 (green line) demonstrated coordinated stress response behavior; both reached and sustained their physical output lower limits (saturation state) for extended periods.

5. Conclusions

- Ensures Robust Voltage Stability: Maintains voltage deviation within strict safety limits under diverse uncertainty scenarios, achieving near-perfect voltage compliance across standard and high-risk tested conditions.

- Mitigates Extreme Risks: Explicitly minimizes the impact of worst-case uncertainty realizations through CVaR, enhancing grid resilience.

- Reduces Operational Burden: The framework requires only infrequent updates of decision variables (once every 12 h), reducing the critical control downlink frequency by 99.3% compared to standard 3 min real-time control cycles. This significantly lowers the communication overhead and ensures high robustness against communication outages.

- Outperforms Comparative Baselines: Significantly improves voltage profiles compared to traditional decentralized strategies and achieves superior sample efficiency and risk control compared to the meta-heuristic benchmark (i.e., PSO).

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murzakhanov, I.; Gupta, S.; Chatzivasileiadis, S.; Kekatos, V. Optimal Design of Volt/VAR Control Rules for Inverter-Interfaced Distributed Energy Resources. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE. IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces. [Online]. 2018. Available online: https://standards.ieee.org/ieee/1547/5915/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Iranpour Mobarakeh, S.; Sadeghi, R.; Saghafi, H.; Delshad, M. Hierarchical integrated energy system management considering energy market, demand response and uncertainties: A robust optimization approach. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 123, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, X.; Sun, M.; Sun, C. Hybrid Policy-Based Reinforcement Learning of Adaptive Energy Management for the Energy Transmission-Constrained Island Group. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 10751–10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colot, A.; Perotti, E.; Glavic, M.; Dall’Anese, E. Incremental Volt/Var Control for Distribution Networks via Chance-Constrained Optimization. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 4561–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, R.; Huang, H.; Guo, Z. Morphology, key technologies and prospects of active support type VSC-HVDC for enhancing the stability of receiving end power grid. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 6818–6830. [Google Scholar]

- Farivar, M.; Neal, R.; Clarke, C.; Low, S. Optimal inverter VAR control in distribution systems with high PV penetration. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–26 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bolognani, S.; Carli, R.; Cavraro, G.; Zampieri, S. Distributed reactive power feedback control for voltage regulation and loss minimization. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2015, 60, 966–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turitsyn, K.; Šulc, P.; Backhaus, S.; Chertkov, M. Options for control of reactive power by distributed photovoltaic generators. Proc. IEEE 2011, 99, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, P.; Aliprantis, D.C. Distributed Volt/VAr control by PV inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 3429–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, A.; Erdinc, O. Optimal Bidding Strategy Considering Bilevel Approach and Multistage Process for a Renewable Energy Portfolio Manager Managing RESs With ESS. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 6062–6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognani, S.; Carli, R.; Cavraro, G.; Zampieri, S. On the need for communication for voltage regulation of power distribution grids. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2019, 6, 1111–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognani, S. Networked-Volt-Var: A Comparison of Volt/VAR Feedback Control Laws: Fully Decentralized vs. Networked Strategies. GitHub Repository. 2018. Available online: https://github.com/saveriob/networked-volt-var (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Nguyen, Q.P.; Dai, Z.; Low, B.K.H.; Jaillet, P. Optimizing Conditional Value-at-Risk of Black-Box Functions. In Proceedings of the 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2021), Online, 6–14 December 2021; Volume 34, pp. 4170–4180. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.P.; Dai, Z.; Low, B.K.H.; Jaillet, P. Value-at-Risk Optimization with Gaussian Processes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Online, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8063–8072. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q. Bayesian Optimization in Action; Manning Publications Co.: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-61729-932-8. Available online: https://www.manning.com/books/bayesian-optimization-in-action (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Sain, R.; Mittal, V.; Gupta, V. A Comprehensive Review on Recent Advances in Variational Bayesian Inference. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Advances in Computer Engineering and Applications, Ghaziabad, India, 19–20 March 2015; pp. 488–492. [Google Scholar]

- Bolognani, S.; Zampieri, S. On the existence and linear approximation of the power flow solution in power distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vovos, P.N.; Kiprakis, A.E.; Wallace, A.R.; Harrison, G.P. Centralized and distributed voltage control: Impact on distributed generation penetration. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2007, 22, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Qu, G.; Dahleh, M. Real-time decentralized voltage control in distribution networks. In Proceedings of the Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing, Allerton, IL, USA, 30 September–3 October 2014; pp. 582–588. [Google Scholar]

- Farivar, M.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L. Local voltage control in distribution systems: An incremental control algorithm. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications, Miami, FL, USA, 2–5 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kekatos, V.; Zhang, L.; Giannakis, G.B.; Baldick, R. Voltage regulation algorithms for multiphase power distribution grids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 3913–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, H. A Holistic Power Management Strategy of Microgrids Based on Model Predictive Control and Particle Swarm Optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 5115–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, H.; Hu, Q.; Su, B.; Lyu, L. An Adaptive Droop Control Strategy for Islanded Microgrid Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 3579–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, W.H. Radial distribution test feeders. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES Winter Meeting, Columbus, OH, USA, 28 January–1 February 2001; Volume 2, pp. 908–912. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | 8 | Restarts | 50 |

| Initial samples | 20 | Raw samples | 200 |

| Optimization iterations | 68 | Risk level () | See Section 4.3.1 |

| Parameter | Min | Max | Parameter | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.05 | ||

| 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | ||

| 0.03 | 0.180 | 0.03 | 0.180 | ||

| −1.0 | 1.0 | −0.2 | 0.2 |

| Metrics | Mean ± Std | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| CVaR | - | |

| Voltage Violation Rate | % | |

| Avg. Voltage Deviation | p.u. |

| Metric | Mean ± Std | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Time (68 Iterations) | s | |

| Initialization Time (20 Samples) | s | |

| Total Execution Time | 1869.75 ± 127.68 | s |

| Strategy | Overall Compliance | Non-Compliant Bus Count | High-Risk Violation Rate | Comm. Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled | 95.75% | 6 | 10.71% | – |

| Static Feedback | 98.61% | 4 | 5.21% | Real-time |

| Incremental Feedback | 97.17% | 5 | 8.64% | Real-time |

| PSO (Meta-heuristic) | 99.47% | 2 | 2.34% | 12 h |

| BEO-CVaR (Proposed) | 99.90% | 1 | 0.50% | 12 h |

| Number of Inverters | Voltage Violation Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| 2 | 0.3121% |

| 5 | 0.0062% |

| 10 | 0.1007% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, Y.-N. Robust Voltage Control in Distribution Networks via CVaR-Based Bayesian Optimization. Electronics 2026, 15, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010154

Tian Y-N. Robust Voltage Control in Distribution Networks via CVaR-Based Bayesian Optimization. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010154

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Ye-Ning. 2026. "Robust Voltage Control in Distribution Networks via CVaR-Based Bayesian Optimization" Electronics 15, no. 1: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010154

APA StyleTian, Y.-N. (2026). Robust Voltage Control in Distribution Networks via CVaR-Based Bayesian Optimization. Electronics, 15(1), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010154