Abstract

Simulating what-if scenarios in 3D environments has become popular due to its potential to improve planning and operations for large-scale, complex events, such as the annual Hajj. Despite the extensive availability of spatial data through Geographic Information Systems (GIS)—information systems specialized in collecting, organizing, and analyzing geospatial information—these resources remain underutilized for such use cases. Three-dimensional modelers create simulations for these use cases and build them from scratch despite the availability of GIS data, which can be tedious and error-prone. We raise the question of whether it is reasonable to use machine learning (ML) algorithms to learn coordinate conversion systems, laying the foundations for accelerating the construction of 3D environments and achieving more accurate results. In this paper, we introduce a simple yet novel framework that facilitates learning coordinate conversion systems. Using our framework, we evaluate 35 ML models and provide a detailed analysis of their prediction performance, overfitting characteristics, and trade-offs in terms of time and model size. Notably, 14 of the ML models demonstrate near-perfect learning (i.e., R-squared very close to 1.0). Furthermore, we use grid search to find better parameter settings for underperforming models. Our results demonstrate that ML can help 3D modelers automate manual tasks and improve the efficiency of 3D modeling from GIS data.

1. Introduction

Three-dimensional simulation environments have become desirable for simulating complex operations in large-scale events, such as Hajj, as observed by the authors who have been working within the Hajj planning and operations ecosystem for many years. Building these 3D simulation environments is time-consuming, and professional 3D modelers start from scratch while consulting Geographic Information System (GIS) data that is available to them. GIS data are abundant due to the investment of the Hajj authorities in building such datasets, as they can be used to assist in planning, operations, and reporting. However, there is no integration between GIS and the process of building 3D simulation environments.

The integration of GIS data into 3D simulation environments represents a significant advancement in simulating real-world scenarios. This integration allows for a more accurate and detailed depiction of real-world landscapes, urban environments, natural features, and infrastructure. By incorporating GIS data, simulations can closely mimic the complexities and dynamics of real-world scenarios, making them more effective for various applications such as urban planning, disaster management, environmental modeling, and transportation analysis [1].

To address this integration challenge, we raise the question of whether it is reasonable to use machine learning (ML) algorithms and techniques to learn coordinate conversion systems, laying the foundations for accelerating the construction of 3D worlds and environments and achieving more accurate results.

This paper presents a novel framework that leverages ML techniques to facilitate this integration process. The framework is designed to optimize the mapping of GIS points to their corresponding 3D world points, enabling the creation of precise 3D objects that accurately represent real-world data within the simulation environment. By utilizing ML models trained on a subset of GIS data, the framework enhances the accuracy and efficiency of the integration process.

Mass crowd-gathering events, such as the Hajj pilgrimage, pose unique and complex simulation challenges that can be effectively addressed through the utilization of 3D gaming engines like Unreal and Unity engines. These advanced engines offer the capability to create immersive virtual environments that can realistically replicate such large-scale events, providing valuable insights and training opportunities [2].

However, the process of constructing these simulated environments, including the creation of buildings, roads, and other objects, presents significant hurdles. While GIS tools are commonly employed for building and managing these environments, achieving seamless compatibility between GIS data and 3D engines can be challenging (e.g, [3,4,5,6,7,8]). Importing GIS data as 3D world objects in Unity, in particular, lacks robust support and requires additional effort to ensure a smooth integration.

A critical aspect of this integration process is the development of accurate coordinate conversion models to transform GIS data from typical GIS coordinates (such as latitude and longitude) to the corresponding 3D engine coordinates. This paper focuses on addressing the foundational questions of how artificial intelligence can be used to build such conversion models.

This work is motivated by the following research questions:

- How can we learn coordinate conversion algorithms using ML approaches instead of manually designing them by hand?

- Using ML models, how to facilitate the generation of 3D objects from extensive GIS data be automated?

Addressing these questions requires solving the coordinate conversion problem with ML techniques, which serves as the central focus of this paper. The ultimate goal is to develop a system that utilizes ML techniques to predict the 3D coordinates of each point based on their corresponding 2D GIS coordinates. This advancement will contribute to the efficient and accurate creation of 3D simulation environments from GIS data, particularly benefiting the simulation of mass crowd-gathering events like Hajj.

However, traditional 3D modelers are likely to lack the advanced mathematical skills necessary to develop and code these equations. Instead, the proposed framework enables mapping functions to be learned directly from data, allowing for coordinate transformation without requiring complex mathematical formulations. Moreover, there are a couple of advantages of using our ML-based framework for this problem. First, our proposed framework handles the data preparation challenges (e.g., consistent and balanced training examples, unintended distortions, and noise). Secondly, ML models can learn from data directly with minimal parameters provided by 3D modelers.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- We develop a systematic ML-based framework for accurate coordinate conversion and demonstrate its effectiveness in transforming GIS coordinates to 3D engine coordinates.

- We conduct extensive experimental studies to evaluate the performance of 35 ML models in solving the coordinate conversion problem.

- We provide a comprehensive analysis of model performance, considering prediction accuracy, fit time and prediction time, model size, and sensitivity to different dataset sizes.

- We publicly release our code and empirical results to support transparency and reproducible research. Our code and data files can be found at: https://github.com/qadahtm/cslearn, accessed on 17 December 2025.

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 provides a discussion of related works, followed by an overview of the proposed framework in Section 3. Section 4 presents the framework used for training and evaluating the ML models used in our study. Also in Section 4, the experimental results and analysis are presented. Finally, this paper concludes with a summary of the contributions and suggests future research directions in Section 5.

2. Related Work

This section provides a comprehensive analysis of previous studies that are relevant to spatial reference frameworks, coordinate transformations, and their applications, covering a wide range of the literature to gather insights into the subject matter. It is organized into two subsections: Section 2.1, sheds light on traditional methods and mathematical models that take center stage in understanding coordinate transformations, while the Section 2.2, explores the cutting-edge intersection of artificial intelligence techniques and spatial reference advances.

2.1. Classical Approaches for Coordinate System Conversion

Rudnicki and Meyer [9] discussed the techniques for transforming local sampling coordinates into globally referenced coordinate systems, such as latitude/longitude or planimetric systems like Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) or State Plane Coordinate System (SPCS). The authors outlined the mathematical formulas required for this conversion and offered approaches to ascertain the planimetric coordinates of new transects. Additionally, they delved into the significance of choosing the correct geodetic datum corresponding to the area of interest.

In his work, Sudano [10] introduced a precise conversion method from an Earth-centered coordinate system to latitude, longitude, and altitude. Utilizing the Newton–Raphson method for root finding, the author devised a robust implementation applicable across all latitudes. The proposed technique offers an exact solution for determining the coordinates of a trajectory from an Earth-centered coordinate system, making it valuable for spectrum consumption modeling applications [11].

Julier and Uhlmann [12] tackled the problem of accurately transforming uncertain state estimates between Cartesian and spherical coordinate systems, crucial for tracking and estimation tasks. The authors point out the inefficiency of conventional linearization methods when dealing with significant uncertainties, often resulting in biases and discrepancies between the results. Additionally, they highlight the complexities associated with higher-order transformation modes, citing substantial implementation burdens. The authors proposed the Consistent Debiased method, which strategically employs discrete samples to capture the first four moments of measurements. The proposed approach aims to enhance consistency and performance while eliminating the need for derivative calculations. Shank [13] addressed the necessity of a coordinate conversion algorithm in multisensor data-processing systems utilized by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Following an examination of various cartographic projection techniques, the paper advocates for the adoption of stereographic projection and outlines the implementation of a refined stereographic projection algorithm. This proposed algorithm incorporates approximations and a correction term to ensure compliance with the accuracy standards of the data processing system.

Moreover, Ligas and Banasik [14] proposed a method for converting Cartesian coordinates on an ellipsoid to geodetic coordinates. The approach relies on applying Newton’s method to solve a system of nonlinear equations. This method was successfully evaluated across various height ranges and outperforms other iterative methods, as demonstrated by comparisons with [15,16]. Dawod and Alnaggar [17] proposed a stepwise multiple regression technique for converting GPS coordinates from the global geocentric WGS84 datum to the local Egyptian non-geocentric coordinate system. The authors propose that the determination of the number of unknowns in the regression equations should consider factors like statistical measures and the availability of coordinates. This approach has shown improved accuracy when compared to traditional transformation methods such as the Bursa–Wolf and Molodensky–Badekas models.

On the other hand, other researchers have developed a method for evaluating the performance of coordinate transformations, as discussed in [18]. In this study, the authors utilized quality indicators such as precision and conformality for the evaluation process. The objective was to determine the most suitable transformation for a geodetic network. Furthermore, some researchers have explored algebraic solutions for transforming Cartesian coordinates to geodetic coordinates. Guo and Shen [19] presented a solution that involves solving a quadratic equation and determining the integer root of the equation. Notably, their algorithm does not rely on approximations and effectively addresses the instability issues that were encountered with previous algebraic solutions.

2.2. AI-Based Approaches for Coordinate System Conversions

In their study, Ziggah et al. [20] investigated the application of ANN in converting geodetic coordinates to Cartesian coordinates during coordinate transformations between global and local datums. The researchers compared three techniques, including multiple linear regression (MLR), backpropagation artificial neural networks (BPANN), and radial basis function neural networks (RBFNN). The study utilized 328 GPS geodetic coordinates from Tarkwa, Ghana, and all geodetic data were converted to cartesian coordinates using the standard forward transformation equation from [21]. The geodetic points were divided among the BPANN and RBFNN models for training, validation, and testing purposes, with 150 points allocated for training, 78 points for validation, and 100 points for testing. The results revealed that RBFNN was the most accurate and stable approach. The study concludes that RBFNN provides satisfactory prediction results, indicating its potential to address function approximation challenges in geodesy.

Following this, Ziggah et al. [22] explored the use of ANN and the Bursa–Wolf model for coordinate transformation in Ghana. They identified a limitation with the traditional hold-out cross-validation approach, which could result in biased outcomes due to improper data partitioning. To address this issue, the authors investigated the effectiveness of employing the K-fold cross-validation method to assess the performance of these models in Ghana’s geodetic reference network. Their findings revealed that the RBFNN model outperformed the Bursa–Wolf model, exhibiting a lower root mean square error.

Additionally, Yilmaz and Gullu [23] studied the use of BPANN for georeferencing historical maps. The study focused on comparing a modern map of Cyprus Island with one made by Piri Reis in the 1500s. The findings indicated that ANN methods can effectively transform the coordinates of historical maps onto modern maps, enhancing graphic accuracy. Furthermore, the growing need for precise coordinate transformations across various reference frames was studied by Turgut [24]. The author utilized back-propagation artificial neural networks (BPANNs) to convert coordinates between the European Datum 1950 (ED50) and the World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS84) in Turkey. A comparison between the BPANN and the Molodensky–Badekas method revealed BPANN’s superior accuracy and how it can be useful for 3D coordinate transformation between ED50 and WGS84.

Maria [25] utilized ANN to tackle the challenge of coordinate transformations necessary for incorporating map data into the new geocentric European system. The study proposes an ANN-based method for coordinate transformation and compares it with the Molodensky–Badekas method. The findings reveal that the ANN-based approach outperforms in terms of accuracy and efficiency when navigating across various reference systems.

Furthermore, there are other research efforts that have also employed ANN techniques for coordinate transformation between different coordinate systems, as evidenced by studies [26,27,28,29,30]. This trend underscores the growing recognition and adoption of ANN techniques in geospatial data processing due to their capability to remove the need for pre-determined transformation parameters, commonly associated with transformation models’ hypotheses, enabling a faster and more accurate solution to the conversion problem without relying on specific transformation assumptions [31].

While previous studies have successfully applied ANNs and other ML techniques to transform coordinates, there is a lack of automated methods for effectively linking GIS coordinate systems to 3D simulation models [3]. This limits efficient model preparation for applications such as crowd movement simulation. Therefore, this study contributes to the advancement of this field by being one of the first to employ a ML approach as a fully automated workflow specifically designed to transform GIS coordinates into 3D simulation coordinates, thus addressing a practical gap identified in previous work.

3. Methodology

This section provides an overview of the primary phases and elements of the proposed approach, followed by a detailed explanation of each phase, including data pre-processing, learning coordinates’ conversion, hyperparameter optimization, training data generation algorithm, building coordinate conversion model, hyperparameter optimization, and ML models.

3.1. Proposed Framework

This paper presents a novel framework designed to convert GIS data into 3D engine data, facilitating the simulation of various scenarios within 3D simulation environments. The proposed framework bridges the gap between the rich and detailed geospatial data provided by GIS and the immersive, dynamic simulation capabilities of 3D engines. By taking advantage of this transformation, the framework aims to enhance the realism and accuracy of simulations that can be applied in fields as diverse as urban and transportation planning, healthcare systems, social simulations, and disaster management.

Several ML models are used in this work to convert the geographical data into a format that is appropriate for the 3D simulation environment. These models have the ability to learn the patterns, relationships, and mappings between GIS points and the corresponding 3D engine points, enabling accurate and efficient conversion.

The transformation process involves feeding the GIS data into the trained ML models, which then generate the necessary mappings and transformations. These mappings allow for the creation of 3D objects, which accurately represent the real-world data within the simulation environment. These 3D objects can include buildings, terrain features, infrastructure, and other relevant elements. The integration of ML models into the conversion process elevates the accuracy of the proposed framework within the simulation environment. By employing models, the framework ensures that the transformed 3D objects closely mirror real-world GIS data, making simulations more realistic and attractive.

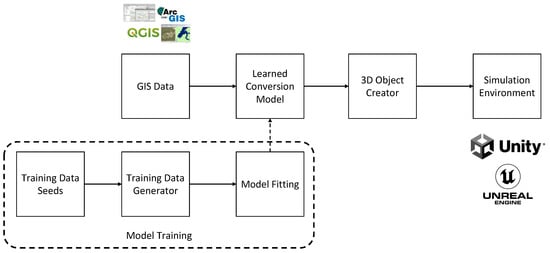

Figure 1 shows the proposed framework that illustrates how the proposed system seamlessly integrates ML models into the transformation process. This illustration highlights the importance of this integration in enhancing the realism and accuracy of simulations within the 3D environment.

Figure 1.

Our proposed GIS-to-3D framework. The framework trains an ML model using generated data. The model converts GIS coordinates to 3D environment coordinates, which the 3D object creator module uses to create objects for simulation environments.

The process begins with training an ML model using generated data from training data seeds to create a Learned Conversion Model. Then, GIS Data (e.g., geospatial objects’ coordinates) from existing GIS databases are used as input to the Learned Conversion Model to predict the 3D coordinates from GIS coordinates. These coordinates are used instantly by the 3D Object Creator to create 3D object structures. Lastly, these precise 3D objects are then integrated into the Simulation Environment (e.g., Unity or Unreal Engine) for detailed simulation scenarios.

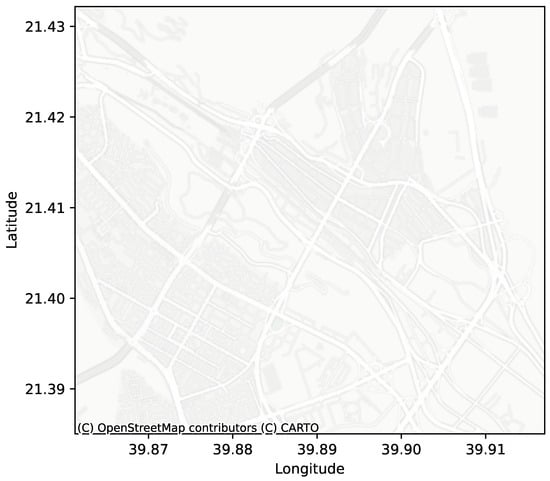

As an example of real-world application, Figure 2 represents the specific area of interest in our study, which is located in Mina, Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Mina is considered the largest tent city in the world, with about 160,000 tents designed to accommodate pilgrims [32].

Figure 2.

Example of a GIS area of interest, which is the bounding rectangle of Mina site. The x-axis represents real-world longitude values and the y-axis represents real-world latitude values. This area’s bounding box is presented in Table 1 and used as a running example throughout this paper.

This area is accurately depicted in both GIS and 3D simulation engine coordinate systems (e.g., Unity), as outlined in Table 1. The coordinate points provided in the table, including the top-left and bottom-right coordinates, provide essential information for precisely defining the targeted area within the simulation environment.

Table 1.

An example of seed data to train ML models for a specific area, which is the Mina site, as shown in Figure 2.

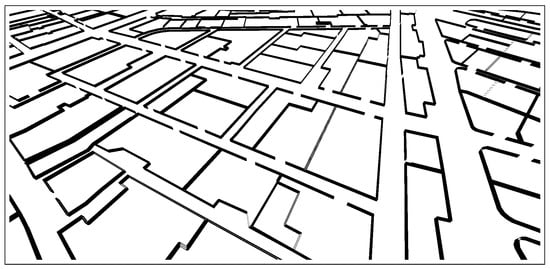

The seed points are employed to synthetically generate additional data points, which are then utilized to train the ML model. This trained model enables the inference of any other point within the area of interest in 3D engine coordinates. Once the model is trained, it is deployed to map all GIS points to their corresponding 3D engine points. These 3D engine points are then utilized to construct the 3D objects crucial for the simulation process. An example of the generated 3D objects, specifically corresponding to the camps in Mina, is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

An example of generated 3D objects in Unity, which corresponds to the 3D objects used to represent camps in Mina.

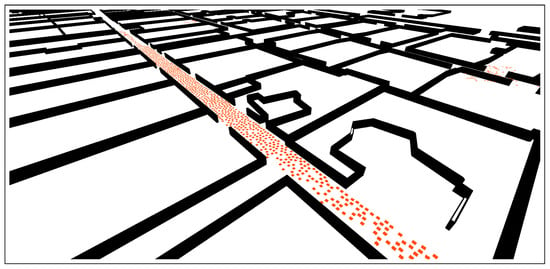

Finally, the 3D world created within the simulation environment serves as the foundation for simulating various scenarios, such as scheduling trips and managing crowds, in the final step of the framework. Figure 4 shows a screenshot of our simulation scenario for simulating people moving from two points in the world. This scenario simulates a plan for crowd management. In this example, the red squares represent people moving according to the planned scenario. The aim of the simulation is to estimate the time required and the success of the crowd management plans. Thus, the integration of GIS data into the 3D simulation environment facilitates more realistic and accurate simulations, applicable to addressing diverse challenges and requirements across various domains.

Figure 4.

A screenshot for the simulation environment for the Mina usecase. The red squares represent pilgrims in the simulation environment.

3.2. Learning Coordinates’ Conversion

To build an ML model for coordinate conversion, we need a training dataset. A naive approach to preparing the training dataset is to do manual mapping. Manually creating training data is difficult, error-prone, and time-consuming. The naive approach in our case requires manually finding matching GIS and 3D world coordinates for each object, as well as ensuring that these coordinates are appropriately aligned with each other. Tens of coordinates may specify a single object, and there can be thousands of objects. The person creating the dataset must ensure accuracy and consistency across the two coordinate systems and within the target coordinate system. For example, consider points A and B in GIS and their matching points in Unity C and D, respectively. Points C and D must have the same relative distance as points A and B, respectively. Creating more points must also maintain the relative distances precisely. Otherwise, the mapping becomes non-linear and inaccurate. Instead, we propose a method that generates training data based on seed points. In the remainder of the section, we use the example shown in Table 1 and describe our approach in the context of building 3D camp objects in Unity from their corresponding GIS coordinates.

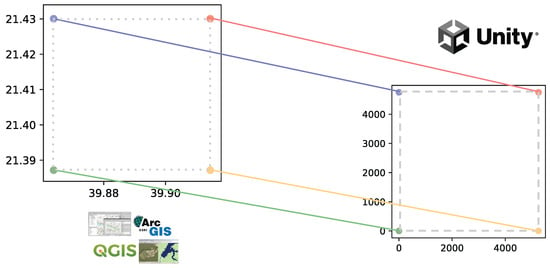

Our approach depends on the assumption that the area containing all coordinates is rectangular in both coordinate systems. Figure 5 shows the four points that represent the corners of the rectangles in each system. The dotted line on the left side represents the area of interest in GIS coordinates, while the dashed line represents the corresponding area of interest in Unity coordinates. The rectangular shape of the area of interest assumption is leveraged in our design for the training data generation algorithm. By utilizing the corner points, the algorithm generates additional training points.

Figure 5.

The boundary coordinates in the GIS system (left) and their corresponding counterparts in the Unity system (right).

3.3. Training Data Generation Algorithm

The intuition behind the algorithm is to generate uniformly distributed points with the area of the rectangle specified by the given corner points. We generate points along each pair of corner points so that the relative distances between them are maintained. We denote the rectangle in the GIS (source) coordinate system as S, and the corresponding rectangle in the Unity (target) coordinate system as T. To help illustrate our algorithm, we use common object-oriented notation. Thus, each rectangle is basically a tuple containing the attributes [top-left, top-right, bottom-left, bottom-right] representing the corners of the rectangle. The notation ‘S.topleft’ is used to refer to the point representing the top-left corner of the rectangle S. The same approach is applied to other attributes. Each attribute is a point object consisting of the attributes .

Furthermore, we define function to compute the sequence of n points that have equal distances from each other along the line formed by any two points and , as follows:

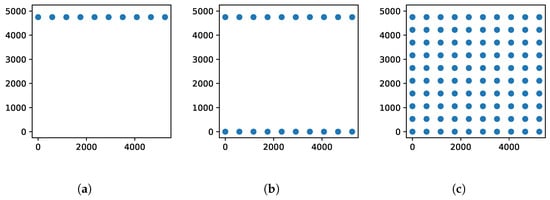

Algorithm 1 describes of the point generation concept with a vertical orientation. The basic idea of the vertical algorithm is to compute interpolated points along the top edge of the rectangle (Line 2, see Figure 6a). Then, it computes the points for the bottom edge (Line 3, see Figure 6b). After that, for each pair of points that forms a vertical line (Line 5), we compute n additional points between them and include them in the output results for the procedure (Line 4, see Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Example visualization of points generated at different lines of Algorithm 1 with . (a) Points generated after Line 2 in Algorithm 1. (b) Points generated after Line 3 in Algorithm 1. (c) Points generated after Line 7 in Algorithm 1.

It is worth noting that the same results can be obtained using a horizontal generation algorithm. The algorithm starts by computing points on the left and right edges. Then, the points between every horizontal line between the generated points are generated.

| Algorithm 1 Pseudocode for the vertical point generation algorithm |

|

Dataset Generation Example. To generate points with , for S, the algorithm runs with the following arguments:

Similarly, we generate points for T with the following arguments:

Figure 6 shows the visualizations of points in different steps for this example. It is worth noting that the result is constructed such that data point is assigned the label point . In other words, is the dataset that will be used to build coordinates conversion model.

4. Experimental Evaluation and Analysis

In this section, we discuss our evaluation methodology and present an analysis of our results. We aim to provide a comprehensive evaluation of ML models to solve the problem of coordinate conversion.

4.1. Evaluation Methodology Overview

After generating the dataset, i.e., , we are ready to build our models. In this section, we describe our methodology for evaluating ML models for coordinate conversions, and present our evaluation results.

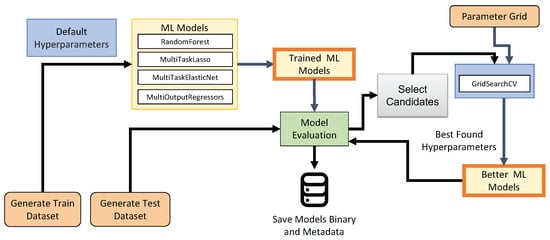

Figure 7 illustrates our proposed framework. We generate training data and test data separately.

Figure 7.

The proposed evaluation framework. Our evaluation framework uses generated data as described by Algorithm 1 in Section 3.3. A set of 35 ML models with default hyperparameters is created (shown in Table 2). We fit every model in the set and save its binary state. For those models, we use GridSearchCV to find better hyperparameters. The models with the newly found better hyperparameters are trained and evaluated using the same generated training datasets.

We train and evaluate thirty-five models taken from the ScikitLearn [33]. Table 2 lists the names of all the models we used in our evaluation. We use as our scoring metric for all models, which is the default metric set by ScikitLearn (i.e., ). After analyzing the results, we select a subset as candidates for hyperparmeter grid search to find better parameters to tune them.

Table 2.

We included 35 models in our study. Models 1–3 can handle predicting multiple values while models 4–35 are based on the MultiOutputRegressor (MOP) model where the model name in the paranthsis is used as an estimator for MOP. MOP is used to predict multiple values (two in our case) using the underlying estimators.

Grid search and cross-validation methods are used to determine the most suitable parameters for the ML models. These methods are often employed for optimizing hyper-parameters [34,35]. The grid search methodically assesses every potential combination of parameters within a set range and identifies the optimal one based on a predetermined evaluation metric. Cross-validation involves dividing the data into K separate subsets, using for training and the remaining fold for validation. The final result is obtained by averaging the evaluation of K fold validation findings. We utilize the GridSearchCV function to optimize the hyperparameters of the ML models by combining grid search and cross-validation.

From the thirty-five models we included in our study, models 1–3 can handle predicting multiple values, while models 4–35 are based on the MultiOutputRegressor (MOP) model where the model name in parenthesis is used as an estimator for MOP. MOP is used to predict multiple values (two in our case) using the underlying estimators.

4.2. Prediction Performance Analysis

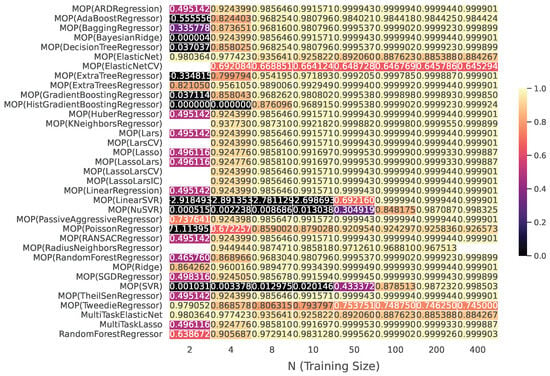

Our results are shown in Figure 8, which is a heatmap representing all test scores without hyperparameter tuning. The x-axis represents the values of N. The y-axis represents the model numbers. The color intensity represents the score. Darker colors represent bad scores, while lighter colors represent good scores. Negative values are colored with the same color as zero values to help emphases the variations in scores between and . Blank values indicate that the model implementation cannot handle the respective value of N. For exampple, MOP(RadiusNeighborsRegressor) had errors during execution for (insuffient number of traning data samples) and (out-of-memory).

Figure 8.

A heatmap representing the test scores of all 35 models. Dark colors indicate low scores, while bright colors indicate high scores. Higher is better.

Most models perform very well, achieving a near-perfect score with a sufficiently large training size.

For most models, test scores improve as N grows, which suggests that larger training datasets lead to better generalization. This is especially visible for models that initially exhibit low test scores at small N, then quickly climb to near-perfect performance as N increases. Interestingly with , 29 models obtain near-perfect scores.

However, some models, e.g., MOP(PoissonRegressor), MOP(TweedieRegressor), MOP(ElasticNet), and MOP(ElasticNetCV), struggle to learn the coordinate conversion problem. The MOP(TweedieRegressor) and MultiTaskElastiNet scores degrade as we increase the training size. MOP(ElasticNet) remains relatively flat regardless of increasing the training size.

Our results show that ML models can learn the coordinate conversion formula with near-perfect scores. This is due to the “simple” relationship between the source and target coordinate systems. Also, our area is relatively small (i.e., a few square kilometers). We leave the study of larger areas that may not be planar geometrically to future work. While developing conversion algorithms analytically is intended to achieve perfect accuracy, it requires sophisticated skills. Alternatively, an ML-based approach can yield acceptable results in many common cases without requiring sophisticated skill sets.

With so many models achieving near-perfect scores, the selection criteria might shift from pure accuracy to other considerations such as computational efficiency (fit time, scoring time) and model size (memory requirements).

4.3. Fit Time Analysis

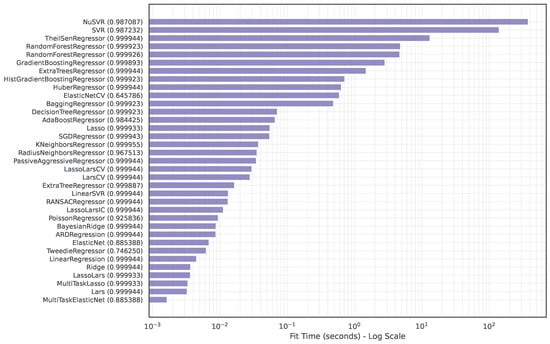

Figure 9 shows the fit time for each model when . It is worth noting that the fit times span 5.4 orders of magnitude (from milliseconds to hundreds of seconds). For example, MOP(NuSVR) takes five orders of magnitude more time than MOP(Lars) to fit the model. Furthermore, using more time for fitting does not mean that the model will have high performance. This means slower models use resources inefficiently compared to faster models with the same test score.

Figure 9.

The average fit time for each evaluated model on a dataset with . The values are sorted. Lower is better. Model accuracy is shown in parentheses.

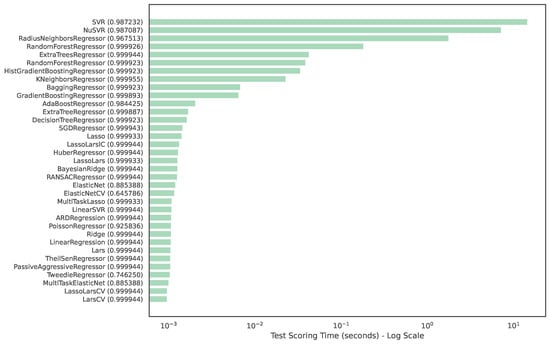

The scoring time bar plot exhibits less variation compared to fit times (see Figure 10). Scoring times span 4.2 orders of magnitude (from milliseconds to tens of seconds). The score time is computed based on a test dataset generated using the same methodology using . This allows us to compare fairly between the variations in N. 13 models have score-times less than or around 1 milliseconds. Out of these 13, 10 models have near-perfect scores.

Figure 10.

The average score time for each evaluated model on a dataset with . The values are sorted. Lower is better. Model accuracy is shown in parentheses.

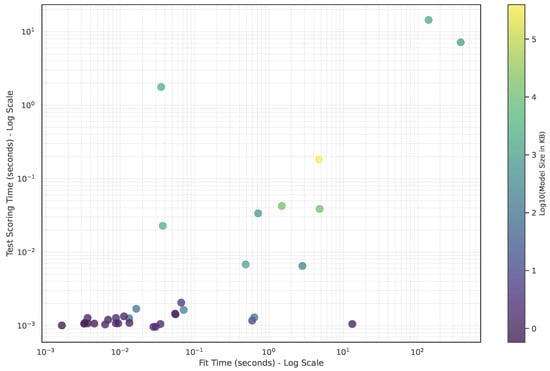

To better visualize the position of each model in respect to fit and score times, we turn to Figure 11. In this figure, there is a clear clustering of models in the lower left corner of the plot, indicating that many near-perfect-scoring models have both low fit times and low score times.

Figure 11.

A scatter plot showing the fit time versus the score time for each evaluated model on a dataset with . The plot uses a log scale.

The color gradient reveals that smaller models (darker colors) are predominantly clustered in the lower left corner, confirming that simpler models tend to be computationally efficient in both training and testing. Using K-Means clustering on this data with , the three identidied clusters have the characterics shown in Table 3. Cluster 0 contains the fastest models (fit times with s and scoring times within s).

Table 3.

The table shows the fit and test scoring times for the identified cluster.

Interestingly, model size does not seem to strongly correlate with score time for many models, as we see both large and small models with similar scoring times.

For applications where both training and inference speed are critical, models in the lower left corner would be optimal choices. MOP(LarsCV) and MOP(LinearRegression) strike an optimal balance between fit and score times. If refitting is infrequent but inference must be fast, models with higher fit times but low score times might still be acceptable.

4.4. Model Size Analysis

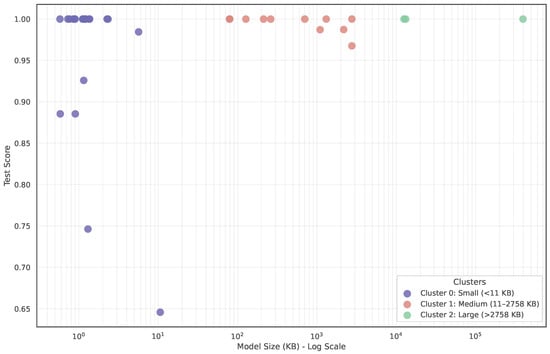

Figure 12 reveals interesting patterns in the relationship between model size and test performance and Table 4 summarizes the basic information about the clusters. Cluster 0 represents small models (<11 ). Many small models (<2 ) achieve near-perfect test scores, demonstrating that model complexity is not always required for high performance.

Figure 12.

A scatter plot showing the test scores versus the model size for each evaluated model, with cluster color-coded on a dataset with .

Table 4.

A summary of identified clusters based the size of the model.

Most MOP-based linear models (LinearRegression, Ridge, Lasso, Lars, LinearSVR, etc.) are included in Cluster 0. Despite the simplicity of linear models, many achieve near-perfect test scores. However, overall performance varies widely in this cluster.

Cluster 1 includes medium-sized models (79 to ). These include neighbor-based models (e.g, KNeighborsRegressor, RadiusNeighborsRegressor) and some SVR variants (e.g., SVR, NuSVR). The performance is near-perfect for many of them, but some provide high performance in general.

The largest three models clustered into Cluster 2 ( to 395 ) include the RandomForestRegressor, which is the largest model. It achieves near-perfect performance as well, but at the cost of more complexity reflected in its size. Interestingly, the MOP with RandomForestRegressor as its estimator has a smaller model size, while it achieves similar test scores. This reveals the efficient implementation of MOP. The third model in this cluster is the MOP(ExtraTreesRegressor).

From an efficiency perspective, models like MOP(LinearRegression), MOP(BayesianRidge), and MOP(TheilSenRegressor) offer the best balance of near-perfect scores with minimal model sizes. These models would be particularly valuable in resource-constrained environments.

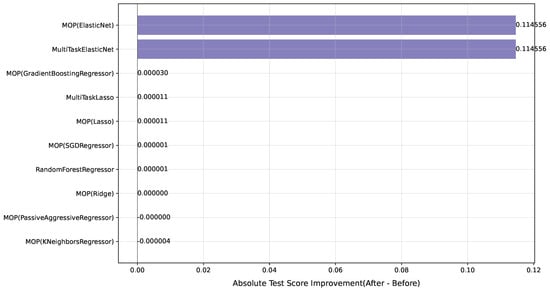

4.5. Improving Test Scores with Hyperparameter Grid Search

So far, we have used default hyperparameter settings for each model. Hyperparameter tuning is crucial for optimizing ML model performance. In this subsection, we look into improving the models’ test score performance by finding better hyperparameters via grid search. We pick our values for the grid search based on our literature review. We aim to answer the following question: Are there better hyperparameter values that can help us achieve better performance of the models we selected? If so, what are these values?

We will focus on hyperparameter tuning on the following ten models: RandomForestRegressor, MultiTaskLasso, MultiTaskElasticNet, MOP(Lasso), MOP(ElasticNet) MOP(SGDRegressor), MOP(Ridge), MOP(KNeighborsRegressor), MOP(GradientBoostingRegressor), and MOP(PassiveAggressiveRegressor). The values of hyperparameters used in the grid search process for each model are displayed in Table 5. We show the default values (in boldface) and the final values of each hyperparameter that resulted in the best performance.

Table 5.

Models and hyperparameter values used in the grid search tuning process. Default hyperparameter values are in boldface. * The symbol ∞ corresponds to the “None” configuration in the Python 3 code which is the default configuration.

Figure 13 shows the test scores for the ten selected models. Two models show improved performance, which are the two versions of the ElasticNet model. Their scores improved by . The remainder of the models showed almost no improvement as they are near-perfect already. This indicates that the grid search for finding hyperparameters is not needed and does not help significantly improve the performance any further. Some models showed a decrease in performance, but it is negligible.

Figure 13.

The performance improvement of models selected for hyperparameter grid search with a dataset with .

5. Concluding and Future Work

This paper proposed an integrated machine learning (ML) framework model that automates the conversion of GIS coordinates to highly accurate 3D coordinates. The framework can simplify the construction of 3D environments, resulting in higher accuracy and reliability in simulation-based analysis and decision-making. The proposed framework was extensively evaluated using 35 ML models across multiple training dataset sizes, measuring prediction accuracy , overfitting behavior, fit time, prediction time, and the impact of the training dataset sizes N. We also study how to improve the performance of underperforming ML models using grid search to demonstrate the ability of these models and give insights into their hyperparameter selection.

The simulation results showed that coordinate conversion is a highly learnable problem, as about 29 out of 35 models are able to perform near-perfectly () with 400. In addition, most of the simulation results, especially for moderate dataset sizes (N = 100∼200), were above = 0.90. Moreover, there is an evident difference in the test scoring time (in milliseconds) of the tested ML models. LarsCV, LassoLarsCV, and MultiTaskElasticNet models were the fastest models with scoring times of 0.96, 0.963, and 1.01 ms, respectively, whereas the model that recorded the slowest scoring time was SVR at 987.232 ms. Interestingly, the results indicate that model size does not strongly correlate with scoring time, as both large and small models exhibited similar performance. The statistics also show that 60% of the ML models are lightweight (under 11 kB, mostly MOP-based linear models), whereas the largest model was the Random Forest Regressor, with an approximate size of 395 MB.

Our results demonstrate that ML models can learn the coordinate conversion formula with near-perfect scores. Moreover, our proposed framework has significant potential applications in several critical areas, such as urban planning, where it can be used for cityscape visualization and infrastructure development simulations; crowd management, for planning and executing large-scale events; environmental studies, to simulate natural disasters and their effects on landscapes; and disaster management, where it can help in planning evacuation routes and emergency response strategies. This potential is supported by ML’s proven track record in automating complex engineering tasks, as demonstrated in the literature [36,37,38].

Future work includes evaluating deep learning models for our problem and studying the problem of mapping GIS data to large-scale 3D environments (e.g., the whole area of a Makkah city), improving the 3D object construction to be more realistic by mapping LiDAR data, and developing more sophisticated 3D object construction algorithms.

Author Contributions

T.M.Q.—Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Project Administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Writing—Review and Editing. A.N.A.-H.—Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration, Writing—Review and Editing. S.A.—Investigation, Software, Writing—Original Draft Preparation. M.M.—Software. M.K.S.—Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques Institute for Hajj and Umrah Research at Umm Al-Qura University under project No. 22/109.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available upon request. Moreover, the data and code for this research paper will be made publicly available after the completion of the peer-review process.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Wang, X.; Xie, M. Integration of 3DGIS and BIM and its application in visual detection of concealed facilities. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungherr, A.; Schlarb, D.B. The extended reach of game engine companies: How companies like epic games and Unity technologies provide platforms for extended reality applications and the metaverse. Soc. Media + Soc. 2022, 8, 20563051221107641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyuksalih, I.; Bayburt, S.; Buyuksalih, G.; Baskaraca, A.P.; Karim, H.; Rahman, A.A. 3D modelling and visualization based on the unity game engine–advantages and challenges. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 4, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossowski, J.; Szandała, T.; Mazurkiewicz, J. Predicting Desire Paths: Agent-Based Simulation for Neighbourhood Route Planning. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2025, 117, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fata, A.Z.A.; Rahim, M.S.M.; Kari, S. Autonomous Tawaf Crowd Simulation. Borneo Sci. 2015, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Boccardo, P.; La Riccia, L.; Yadav, Y. Urban Echoes: Exploring the Dynamic Realities of Cities through Digital Twins. Land 2024, 13, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksa, F.I.; Ashar, M.; Siswanto, H.W.; Malem, Z.Z. Immersive virtual reality for improving flood evacuation behaviour and self-efficacy. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2025, 17, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlqvist, J.; Ronchi, E.; Gwynne, S.M.V.; Kinateder, M.; Rein, G.; Mitchell, H.; Bénichou, N.; Ma, C.; Kimball, A.; Kuligowski, E. The simulation of wildland-urban interface fire evacuation: The WUI-NITY platform. Saf. Sci. 2021, 136, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicki, M.; Meyer, T.H. Methods to convert local sampling coordinates into geographic information system/global positioning systems (GIS/GPS)–compatible coordinate systems. North. J. Appl. For. 2007, 24, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudano, J.J. An exact conversion from an Earth-centered coordinate system to latitude, longitude and altitude. In Proceedings of the IEEE 1997 National Aerospace and Electronics Conference, NAECON 1997, Dayton, OH, USA, 14–17 July 1997; IEEE: Dayton, OH, USA, 1997; Volume 2, pp. 646–650. [Google Scholar]

- Stine, J.A. Model-based spectrum management: Loose coupling spectrum management and spectrum access. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Symposium on Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks (DySPAN), Aachen, Germany, 3–6 May 2011; IEEE: Aachen, Germany, 2011; pp. 628–631. [Google Scholar]

- Julier, S.J.; Uhlmann, J.K. Consistent debiased method for converting between polar and Cartesian coordinate systems. In Proceedings of the Acquisition, Tracking, and Pointing XI, Orlando, FL, USA, 23–24 April 1997; SPIE: Orlando, FL, USA, 1997; Volume 3086, pp. 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Shank, E.M. A Coordinate Conversion Algorithm for Multisensor Data Processing; Technical report; Lincoln Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Lexington, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ligas, M.; Banasik, P. Conversion between Cartesian and geodetic coordinates on a rotational ellipsoid by solving a system of nonlinear equations. Geod. Cartogr. 2011, 60, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.C.; Wang, J. Transformation from geocentric to geodetic coordinates using Newton’s iteration. Bull. Geod. 1995, 69, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, K.M. Accurate algorithms to transform geocentric to geodetic coordinates. Bull. Géodésique 1989, 63, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawod, G.; Alnaggar, D. Optimum geodetic datum transformation techniques for GPS surveys in Egypt. In Proceedings of the Al-Azhar Engineering Sixth International Engineering Conference, Cairo, Egypt, 1–4 September 2000; Al-Azhar University: Cairo, Egypt, 2000; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Hill, C. Evaluation Procedure for Coordinate Transformation. J. Surv. Eng. 2005, 131, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.C.; Shen, W.B. A new algebraic solution for transforming Cartesian to geodetic coordinates. Surv. Rev. 2022, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziggah, Y.Y.; Youjian, H.; Yu, X.; Basommi, L.P. Capability of Artificial Neural Network for Forward Conversion of Geodetic Coordinates (ϕ, λ, h) to Cartesian Coordinates (X, Y, Z). Math. Geosci. 2016, 48, 687–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, W.A.; Moritz, H. Physical Geodesy; W. H. Freeman and Company: San Francisco, CA, USA; London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Ziggah, Y.Y.; Youjian, H.; Tierra, A.R.; Laari, P.B. Coordinate transformation between global and local data based on artificial neural network with k-fold cross-validation in Ghana. Earth Sci. Res. J. 2019, 23, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, I.; Gullu, M. Georeferencing of historical maps using back propagation artificial neural network. Exp. Tech. 2012, 36, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, B. A back-propagation artificial neural network approach for three-dimensional coordinate transformation. Sci. Res. Essays 2010, 5, 3330–3335. [Google Scholar]

- Maria, M.F.R. Coordinate Transformations for Integrating Map Information in the New Geocentric European System Using Artificial Neuronal Networks. Available online: http://revcad.uab.ro/upload/21_68_Paper31_RevCAD12_2012.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Abbas, A.I.; Alhamadani, O.Y.M.; Mohammed, M.U. The application of an artificial neural network for 2D coordinate transformation. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 31, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierra, A.; De Freitas, S.; Guevara, P.M. Using an Artificial Neural Network to Transformation of Coordinates from PSAD56 to SIRGAS95. In Geodetic Reference Frames; Drewes, H., Ed.; Series Title: International Association of Geodesy Symposia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 134, pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konakoglu, B.; Cakır, L.; Gökalp, E. 2D coordinate transformation using artificial neural networks. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, 42, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullu, M. Coordinate transformation by radial basis function neural network. Sci. Res. Essays 2010, 5, 3141–3146. [Google Scholar]

- Elshambaky, H.T.; Kaloop, M.R.; Hu, J.W. A novel three-direction datum transformation of geodetic coordinates for Egypt using artificial neural network approach. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiman, Y.; Sugaipova, L. On the coordinate systems transformation. Geod. Cartogr. 2022, 987, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambour, M.K.Y.; Khan, E.A. A late acceptance hyper-heuristic approach for the optimization problem of distributing pilgrims over Mina Tents. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2022, 28, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scikit-Learn. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python—Scikit-Learn 1.4 Documentation. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/1.4/index.html (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X. Grid search with a weighted error function: Hyper-parameter optimization for financial time series forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 154, 111362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.F.F.; Boutros, P.C. The parameter sensitivity of random forests. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusban, M.; Alhusban, M.; Alkhawaldeh, A.A. The efficiency of using machine learning techniques in fiber-reinforced-polymer applications in structural engineering. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Văduva, B.; Avram, A.; Matei, O.; Andreica, L.; Rusu, T. A GIS-Driven, Machine Learning-Enhanced Framework for Adaptive Land Bonitation. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, N.A.; Bal, S.; Inayathulla, M. GIS Applications and Machine Learning Approaches in Civil Engineering. In Recent Advances in Civil Engineering for Sustainable Communities: Select Proceeding of IACESD 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 459, p. 157. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.