Abstract

Depthwise Separable Convolution (DSC) is widely used due to its significant reduction in parameters and computational cost. However, the depthwise convolution process leads to a decrease in spatial information integration, limiting the network’s expressive power. To address this, we propose a novel Preference-Value Convolution (PVConv) to enhance DSC’s expressiveness. By integrating PVConv into DSC, we introduce the Preference-Value Depthwise Separable Convolution (PVDSC) structure. We integrate both DSC and PVDSC into the YOLOv8 framework and conduct experiments on a beverage container dataset containing visually similar object categories and background interference. Results show that, with minimal increase in parameters and computational cost, introducing preference values significantly improves detection accuracy, F1 score, and attention consistency, especially at high IoU thresholds (mAP@50:95), where object localization is greatly enhanced and certain metrics even surpass complex baseline models. Overall, PVConv significantly enhances the expressiveness of DSC-based networks while maintaining low computational overhead, with promising applications.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid development of high-performance GPUs and other hardware has significantly accelerated progress in deep learning [1,2,3], particularly in computer-vision tasks such as image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation. Among various deep-learning models, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have emerged as a dominant approach due to their strong hierarchical feature extraction capabilities [2,4]. Early architectures such as LeNet [4] demonstrated the value of stacking convolutional and pooling layers for handwritten digit recognition. Subsequent breakthroughs—including AlexNet [2], which popularized ReLU activation and won the ILSVRC 2012 competition, and deeper networks like VGG [5] and ResNet [6]—showed that increased depth and improved structural design can substantially enhance performance. However, deeper and more complex networks inevitably introduce higher computational and parameter costs, motivating continued efforts toward lightweight architectures that maintain or even improve accuracy.

To address the computational and storage demands of modern CNNs, researchers have explored various strategies to balance efficiency and accuracy [7,8,9,10]. Representative examples include the MobileNet series [7,11,12] and the ShuffleNet series [8,13], both designed for mobile and embedded deployment. MobileNet introduced depthwise separable convolution (DSC), which decomposes standard convolution into a depthwise and a pointwise operation, greatly reducing parameters and FLOPs while preserving accuracy. ShuffleNet employed group convolution and channel shuffle to maintain information flow with minimal overhead. These designs demonstrate that lightweight networks can be achieved not only through reducing model size, but also by fundamentally improving convolutional efficiency. More recent architectures such as GhostNet [9] and EfficientNet [10] further refine this accuracy–efficiency balance through optimized module design and compound scaling.

Despite these advances, DSC-based methods still face inherent limitations in feature aggregation. During cross-channel fusion, all filters share the same spatial aggregation mechanism, restricting each filter’s ability to integrate spatial information independently and represent diverse feature combinations [14,15]. This uniform fusion strategy introduces representational bias: some features produce strong activations, while others—especially those associated with visually similar categories—are suppressed. For example, in a conventional DSC module, if one filter is designed to detect tigers and another to detect lions, both filters share similar cat-like semantics during cross-channel aggregation. As a result, the tiger filter, being more responsive to feline patterns, may dominate the activation even when the input is actually a lion. This example illustrates DSC’s difficulty in distinguishing visually similar classes, ultimately limiting its expressive power and potentially degrading detection accuracy.

To address these limitations, we propose a novel PVConv module. Unlike standard pointwise convolution, where all filters share the same spatial aggregation strategy, PVConv enables each filter to learn a preferred range of input feature values. When input features fall within this learned preference range, the corresponding filter response is amplified, enhancing discriminative capacity. The design of PVConv is inspired by the idea of attention, but its operational focus differs: instead of reweighting feature vectors based on their internal distributions, PVConv extracts preference-value information through a dedicated convolutional pathway and uses it to guide the feature processing of DSC, serving as an auxiliary enhancement rather than a direct feature reweighting mechanism. Integrating PVConv into DSC yields the PVDSC module, which we deploy in both the backbone and neck of YOLOv8. Extensive experiments on the Beverage Containers dataset show that PVDSC achieves superior detection performance compared to both standard convolution and DSC, while adding only modest computational and parameter overhead. The improvement is especially pronounced in scenarios with visually similar objects and complex backgrounds. These results confirm that the adaptive preference-learning mechanism effectively mitigates DSC’s inherent aggregation bias, enhancing fine-grained discrimination capability. Moreover, beverage container recognition has practical implications for environmental sustainability and public health. Accurate identification of bottles and cups can support automated recycling systems, improve waste management, and promote recycling awareness. By focusing on fine-grained differentiation among visually similar containers, this research contributes not only to CNN module design but also to real-world applications in environmental and resource management.

2. Related Work

2.1. Evolution of Efficient CNN Architectures

Balancing accuracy and efficiency has long been a central goal in convolutional neural network design. Early works such as MobileNet [7,11,12] and ShuffleNet [8,13] demonstrated the effectiveness of depthwise separable and group convolutions for substantial computational reduction. Subsequent architectures, including GhostNet [9] and EfficientNet [10], further improved feature reuse and scaling strategies. ConvNeXt [16] modernized CNN design with Transformer-inspired principles, followed by variants such as ConvUNeXt [17], LMFRNet [18], Lite-Mono [19], and EdgeNeXt [20]. RepViT [21] further explored convolution–Transformer synergy through structural re-parameterization.

Recent advances continue to broaden CNN design spaces, with large-kernel ConvNets [22] demonstrating strong generalization through expanded receptive fields, and ShiftwiseConv [23] showing that small kernels can approximate large-kernel behavior via spatial shift operations. These efforts reflect a sustained trend toward more expressive yet efficient convolutional structures.

2.2. Advances in Efficient Convolution Operators

Efficient CNNs rely on operator-level innovations to preserve representational capacity while reducing computational cost. MobileNet [7] popularized depthwise separable convolution (DSC), decomposing standard convolution into depthwise and pointwise stages. ShuffleNet [8] introduced group convolutions with channel shuffling to maintain cross-group information flow. GhostNet [9] generated inexpensive “ghost” feature maps to reduce computation while preserving accuracy. Adaptivity further enhances convolutional flexibility. Deformable Convolutional Networks [24] introduced learnable sampling offsets, allowing kernels to adapt to object geometry. DSConv [25] shifts feature maps in multiple directions to enrich spatial dependencies with minimal overhead. Optimized Separable Convolution (OSC) [26] refines separable convolutions through optimized grouping and kernel decomposition, achieving favorable accuracy–parameter trade-offs. More recently, LDConv [27] employs linear deformable convolutions for fine-grained structure modeling, while RapidNet [28] leverages multi-level dilated convolutions for efficient receptive-field expansion. In parallel, lightweight depthwise convolutional shortcuts in ViT demonstrate the effectiveness of reintroducing local inductive bias with negligible computational overhead [29].

2.3. Food and Beverage Object Detection

Beyond general-purpose CNN design, several studies have focused on fine-grained recognition tasks involving beverages and packaged goods, which are closely related to our application scenario. The Smart Unmanned Vending Machines dataset [30] provides a comprehensive benchmark for beverage and retail product recognition under real-world illumination, occlusion, and shelf-layout variations. Similarly, the work in [31] conducts a detailed comparison of modern object detection models on egocentric food and beverage images, highlighting challenges such as small object size, visual similarity among categories, and complex backgrounds. These findings underscore the need for efficient and discriminative feature extractors, especially when dealing with fine-grained object differences in constrained environments, which aligns with the design goals of our PVConv and PVDSC modules.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Depthwise Separable Convolution

Depthwise Separable Convolution, first introduced by Chollet et al. [32], has become a fundamental building block in lightweight convolutional neural networks such as MobileNet [7] and Xception [32]. Unlike standard convolution (stdC), which simultaneously extracts spatial and cross-channel information, DSC decomposes this process into two sequential operations, substantially reducing computational cost and parameter count while maintaining competitive performance in visual recognition tasks.

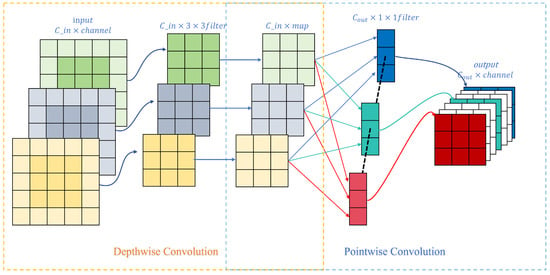

Specifically, DSC consists of two components:

- Depthwise Convolution (DWConv): Applies a K × K kernel to each input channel independently, focusing purely on spatial feature extraction without inter-channel mixing.

- Pointwise Convolution (PWConv): Performs a 1 × 1 convolution across all depthwise outputs to achieve inter-channel feature fusion.

Figure 1 provides an overview of this factorized convolution process.

Figure 1.

Overview of Depthwise Separable Convolution, consisting of Depthwise and Pointwise operations.

The computational cost and parameter count of a standard convolution with M input channels, N output channels, kernel size K, and feature map size H × W are:

For DSC, the total cost can be expressed as:

This decomposition dramatically reduces both computational and parameter overhead compared to standard convolution. In such cases, DSC avoids the quadratic growth of parameters associated with full channel coupling in stdC. However, this efficiency comes at the cost of weakened spatial information integration. In standard convolution, each filter independently aggregates spatial and cross-channel cues, allowing it to form unique, discriminative spatial representations. By contrast, DSC confines spatial extraction to per-channel processing in the depthwise stage, leaving the pointwise convolution to perform only linear channel mixing. This separation causes each filter to lose the ability to independently integrate diverse spatial patterns, reducing discriminative power when handling visually similar objects or complex backgrounds.

3.2. Preference-Value Convolution

Standard pointwise convolution (PWConv) performs linear aggregation of input channels but cannot discern which feature values are most relevant to each filter. To address this, we propose PVConv, which introduces a learnable preference parameter set for each filter j, where denotes the preferred input value of filter j for channel i, and M is the number of input channels. These parameters enable filters to adaptively modulate their responses according to the alignment between input features and learned preferences, capturing fine-grained, filter-specific interactions-especially in scenes with visually similar targets or cluttered backgrounds.

During training, each filter learns preference values corresponding to meaningful semantic patterns. For example, in a scene containing both target and background regions, the network learns preferences numerically closer to the target feature distribution while diverging from the background. Consequently, when similar inputs appear, features near the learned preference range are strongly activated, while irrelevant ones are suppressed. This allows PVConv to perform selective activation based on semantic tendencies, instead of the uniform channel weighting in conventional PWConv.

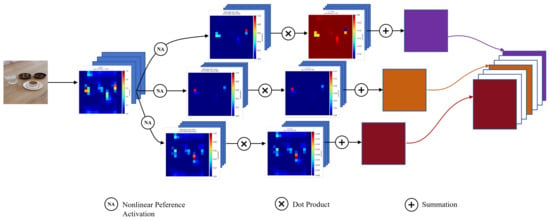

PVConv operates in two stages:

- Nonlinear preference activation: For each position (h, w) and input channel m, the feature value xb,m,h,w (where b is the batch index) is modulated according to its proximity to the filter’s preference value :where f(·) emphasizes values close to the preferred range and attenuates others. The resulting activation map reflects how well the input aligns with each filter’s learned preference.

- Linear aggregation: The preference-activated features are linearly combined using filter weights wjm:where j indexes output channels.

This two-stage process allows each filter to selectively emphasize semantically aligned features and suppress noisy or irrelevant responses. By introducing preference-guided nonlinear modulation before linear fusion, PVConv bridges value-based attention and contribution-based convolution, yielding more expressive and context-aware feature representations.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the difference between standard PWConv and PVConv using identical input features. In PWConv (Figure 2), the intermediate maps largely mirror the input distribution, as linear operations only scale feature intensities without changing their spatial patterns. In contrast, PVConv (Figure 3) generates filter-specific activation maps where each filter highlights different spatial regions based on learned preferences. This selective modulation leads to diverse, informative heatmaps that emphasize relevant structures and enhance the discriminative capacity of the network.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the pointwise convolution process.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the Preference-Value Convolution process.

3.3. Nonlinear Preference Activation Functions

In PVConv, input features are modulated by nonlinear preference activation functions before being linearly aggregated. These functions determine the degree to which each input feature contributes to a specific filter based on the learned preference values. This selective modulation helps focus on relevant features while suppressing irrelevant ones. In this subsection, we introduce two widely used activation types: Gaussian-type and Laplace-type functions.

3.3.1. Gaussian-Type Activation

The Gaussian-type activation function is commonly used in neural networks for feature modulation. It is defined as:

where is the preference value for filter j on input channel i, and σ controls the spread of the activation. The function peaks at and decays exponentially with the squared difference between xi and the preference value, resembling a Gaussian function.

This smooth, bell-shaped response allows the network to focus on features near the preference value while suppressing irrelevant ones. The gradual decay around the center reduces overfitting to small variations in the input, promoting model stability. At the function’s tails, the rapid decay ensures non-informative features are effectively suppressed. This behavior acts as a soft selection mechanism, preserving relevant features and enhancing robustness and generalization [33].

The Gaussian activation is particularly effective in tasks with smooth feature distributions, as demonstrated by Broomhead and Lowe [33]. It is well-suited for scenarios requiring stability and generalization. Additionally, Hertz [34] highlights that Gaussian activations balance feature selectivity and model stability, making them ideal for robust learning in neural networks.

3.3.2. Laplace-Type Activation

The Laplace-type activation function is an alternative to the Gaussian-type function, offering sharper responses to inputs near the preference value. It is defined as:

where b controls the decay rate. Compared to the Gaussian-type function, the Laplace function exhibits a steeper decay near the center, leading to a sharper peak. This characteristic makes it more sensitive to small variations in the input, which can enhance the ability to distinguish subtle differences between features.

The sharper peak enables higher discriminability between similar features, making the Laplace-type activation particularly useful in tasks requiring fine-grained feature selection. However, the steepness of the peak also results in more abrupt gradient changes, which may lead to instability during training or slow convergence, particularly in deep networks [34].

In contrast to the Gaussian-type function, the Laplace-type activation provides a more focused response, making it ideal for scenarios where distinguishing subtle feature differences is critical; However, its sharpness must be balanced against potential training instability. In practical applications, the Laplace function can be employed when higher sensitivity to input variations is required, especially for tasks that demand high-resolution feature discrimination.

Figure 4 illustrates the output characteristics of both functions. The left panel compares the shapes and gradient behaviors of the two functions, where darker regions indicate smaller gradients (slower response), and lighter regions correspond to larger gradients (more sensitive to input variations). The right panel presents the activation distributions of both functions, where the input interval [−4, 4] is uniformly divided into 1000 bins, with values normalized to the [0, 1] range (step size 0.05). In this comparison, the Laplace parameter is set to b = 1, and the Gaussian variance is set to 2σ2 = 1, providing a representative view of the activation behaviors under typical conditions.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Gaussian-type and Laplace-type Activation Functions.

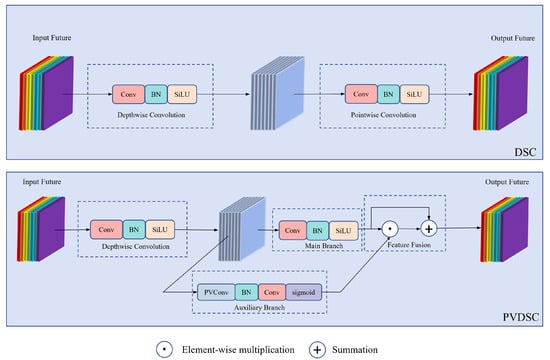

3.4. Preference-Value Depthwise Separable Convolution

The proposed Preference-Value Depthwise Separable Convolution (PVDSC) introduces an auxiliary branch to enhance feature representation in the DSC framework. The main branch performs standard 1 × 1 pointwise convolution (PWConv) to aggregate channel information, while the auxiliary branch employs PVConv to extract preference-based responses. These responses form a preference tensor that adaptively modulates the main branch output via a residual gating mechanism, emphasizing salient features while keeping computational cost low. Figure 5 compares DSC and PVDSC structures.

Figure 5.

Structures of DSC and PVDSC.

3.4.1. Main Branch: Pointwise Convolution

The main branch uses 1 × 1 convolution to mix channel features while preserving spatial resolution. This lightweight transformation serves as the primary semantic path, providing a stable foundation for subsequent preference-based modulation.

3.4.2. PVConv Auxiliary Branch

PVConv extracts value-sensitive responses from the same input tensor, enabling each filter to selectively highlight features aligned with its learned preference. This fine-grained modulation complements the main branch and improves feature discrimination.

3.4.3. Batch Normalization

To stabilize training and expand feature variations, Batch Normalization (BN) is applied to PVConv outputs [35]:

where μB and are batch mean and variance, and γ, β are learnable parameters.

3.4.4. Dimensional Alignment

Since PVConv often outputs fewer channels, a 1 × 1 convolution restores the preference tensor to the main branch dimensionality before fusion. This ensures compatibility and allows balancing representation capacity with efficiency.

3.4.5. Preference-Based Feature Fusion

The normalized preference tensor P′ is passed through a Sigmoid activation to constrain values to [0, 1] and fused with the main output Y via element-wise residual connection:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. Inspired by SE-ResNet [36], this mechanism adaptively recalibrates features while preserving the original content, enhancing discriminative power for task-specific patterns.

3.4.6. Parameter and Computational Cost of PVDSC

To evaluate the efficiency of the proposed PVDSC module, we analyze its learnable parameters and computational complexity in terms of Floating-Point Operations (FLOPs). The module comprises four primary components: depthwise convolution, pointwise convolution, PVConv, and a 1 × 1 convolution for dimensional alignment. The parameter count and FLOPs for each component are derived as follows and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameter and FLOPs estimation of the PVDSC module.

Here, M and N denote the input and output channels, respectively; Nmid is the number of filters in PVConv; K is the depthwise kernel size; and H × W is the spatial resolution of the output feature map. For PVConv, the factor n = 5 accounts for the additional operations introduced by the nonlinear activation function (Gaussian or Laplace), which includes exponentiation, subtraction, and multiplication for preference modulation.

4. Experiments and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Framework

To evaluate the proposed PVDSC, we integrate three convolution types into the backbone and neck of YOLOv8s: standard convolution (Conv), depthwise separable convolution (DSC), and the proposed preference-enhanced version (PVDSC). The models are denoted as:

- YOLOv8-Conv: baseline with standard convolutions.

- YOLOv8-DSC: lightweight variant replacing eligible convolutions with DSC.

- YOLOv8-PVDSC: the proposed model, replacing DSC layers with PVDSC modules.

This setup ensures fair comparison under identical architecture and training settings. Figure 6 illustrates the overall YOLOv8 framework, where the Candidate Conv Module serves as a placeholder that can adopt any of the three convolution types.

Figure 6.

Overall YOLOv8 architecture with candidate convolution modules (Conv, DSC, or PVDSC).

4.2. Dataset

The dataset used in this study is Beverage Containers -v3, an open-source dataset from the Roboflow Universe platform [37]. It contains 15,645 training images and 1303 validation images, each annotated with bounding boxes and class labels in YOLOv8 format.

For preprocessing, all images were resized to 640 × 640 pixels and standard data augmentation techniques were applied to improve model generalization under complex conditions.

This dataset was chosen because the target categories are visually similar—e.g., slender sports bottles and plastic bottles—and include numerous background distractors such as bottle caps or reflections, which challenge conventional CNNs. Therefore, it is suitable for evaluating both discrimination among similar targets and suppression of false activations in cluttered scenes. Beyond these technical motivations, beverage containers are prevalent in daily life and contribute substantially to recyclable waste streams. Accurate recognition of such containers can support automated recycling systems, waste management, and environmental monitoring, highlighting the broader practical significance of this dataset.

Random Subsampling and Bias Mitigation

To reduce computational cost while maintaining representativeness, a subset of 8715 training images was randomly selected. This subset preserves the overall distribution of target categories and retains tens of thousands of annotated instances, ensuring that training remains stable and unbiased. The subset size is sufficiently large to allow effective convergence of YOLO-based detectors, which are known to perform reliably even on smaller datasets, and maintains a reasonable ratio with the 1303 validation images.

The category distribution is shown in Figure 7, and representative sample images illustrating target diversity and background complexity are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Number of labeled objects per category in the dataset.

Figure 8.

Representative sample images illustrating target diversity and background complexity. Red boxes highlight visually similar distractors.

4.3. Experimental Environment and Settings

All experiments were conducted on a deep-learning workstation running Ubuntu 22.04 with an Intel Xeon Silver 4214R CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 Ti GPU (12 GB VRAM). The software environment includes NVIDIA driver version 580.76, CUDA 12.1, and PyTorch 2.4.1.

Preference Parameter Scaling

The preference parameter (pref) exhibits a wide dynamic range ([−5, 5]), making it challenging to train effectively under standard optimization. To facilitate effective updates, pref is scaled down by a factor of 0.01 during optimization, and a detached compensatory term (+99× pref.detach()) is applied during the forward pass to restore its effective magnitude for computation. These specific scaling values (0.01 and +99) were determined empirically through systematic experiments: starting from the initial parameter values, we monitored the update magnitudes of pref in the first few training epochs to ensure that all parameters received effective updates. We then iteratively adjusted the scaling and compensation such that, at the end of training, the majority of pref values were distributed within a reasonable and meaningful range, confirming that the preference information was effectively learned. Additionally, pref is excluded from weight decay regularization to prevent suppression of its learned bias.

To ensure statistical robustness against randomness introduced by data sampling, weight initialization, and data augmentation, all experiments are repeated using five independent random seeds: 0, 10, 100, 1000, and 10,000. Each experiment is trained from scratch under identical hyperparameter settings. The reported results include both the best-performing checkpoint and the mean ± std over all five runs.

Note that while all dataset images are 640 × 640, models were trained at 512 × 512 for our custom CUDA implementation; reported FLOPs are computed at 640 × 640 for standardization.

The detailed training configuration, including key hyperparameters such as learning rate, optimizer, and batch size, is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Training hyperparameter configuration.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed method, standard object detection metrics are employed, covering classification, localization, and efficiency:

- Precision (P) and Recall (R):where TP (true positives) and FP (false positives) are determined by both class prediction and Intersection over Union (IoU) with ground-truth boxes. FN denotes false negatives.

- F1-score:

- Average Precision (AP) and Mean Average Precision (mAP): For each class, the precision–recall curve is computed by varying the confidence threshold. AP is the area under the precision–recall curve:Mean Average Precision (mAP) is obtained by averaging the AP over all classes:

- –

- mAP@50: IoU threshold = 0.5

- –

- mAP@50:95: average over IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 with step 0.05

- Model Efficiency: FLOPs and number of parameters

4.5. Analysis of Experimental Results

4.5.1. Parameter and Computational Analysis

To evaluate the performance of the proposed convolution modules, we computed the parameter counts and FLOPs of the standard convolution (Conv), depthwise separable convolution (DSC), and Preference-Value Depthwise Separable Convolution (PVDSC) across several representative layers in the network’s backbone and neck. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Layer-wise comparison of convolution modules in terms of input/output feature map size, parameters, and FLOPs, including PVDSC variants (imgsize = 640).

As observed, DSC significantly reduces both the parameter count and FLOPs compared to standard convolution. On average, DSC reduces the number of parameters by approximately 85% and FLOPs by about 75% across the selected layers, making it a highly efficient alternative to Conv.

PVDSC introduces additional operations on top of DSC. Compared to DSC, the inclusion of the PVDSC module leads to increases in both the parameter count and computational complexity. However, it still remains significantly more lightweight than Conv. The parameters and computational complexity of the three modules maintain relatively stable proportions. Specifically, the parameters and FLOPs of DSC are approximately of those of PVDSC, while the parameters and FLOPs of PVDSC are about of those of Conv.

4.5.2. Analysis of Detection Performance

We evaluate the detection performance of four convolution modules—standard convolution (Conv), depthwise separable convolution (DSC), and the proposed PVDSC variants with Gaussian (PVDSC_G) and Laplace (PVDSC_L) activations—integrated into the YOLOv8s framework. FLOPs are computed under an input resolution of 640 × 640. For each model, the reported best results correspond to the checkpoint achieving an mAP@50:95 close to the training peak while maintaining a balanced trade-off among precision, recall, and F1-score.To assess robustness, all models are trained with five different random seeds, and the mean ± sample standard deviation (std) of mAP metrics are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Detection performance and resource usage comparison for different convolution modules in YOLOv8s. Best values correspond to a single checkpoint; mean ± std are computed over 5 repeated runs.

As summarized in Table 4, Conv achieves the highest single-run mAP@50 (0.930), whereas DSC slightly decreases both mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 (0.917/0.766), reflecting its reduced representational capacity. The PVDSC variants maintain comparable mAP@50 values to Conv and DSC (0.920–0.923), but consistently achieve higher mAP@50:95 (0.775–0.776), indicating improved localization performance under stricter IoU thresholds. This improvement originates from the preference-based modulation mechanism, which enhances the network’s ability to emphasize relevant semantic responses while suppressing background activations.

The multi-run statistics further confirm this trend. PVDSC_G and PVDSC_L achieve the higher averaged mAP@50 (0.9246 ± 0.0103 and 0.9231 ± 0.0114) and competitive mAP@50:95 means (0.7691 ± 0.0060 and 0.7710 ± 0.0066), calculated from five independent training runs. These results indicate that the proposed modules not only reach high peak accuracy but also maintain stable performance across repeated experiments.

Regarding resource usage, Conv has the highest computational cost (28.7 GFLOPs, 11.14 M parameters), while DSC reduces both to 25.3 GFLOPs and 9.11 M parameters at the expense of accuracy. PVDSC modules provide a favorable balance, with only marginal increases over DSC (26.18 GFLOPs, 9.58 M parameters) while delivering improved fine-grained localization. Reference FPS and memory usage on our custom CUDA implementation are also provided: Conv: 108.42 FPS/6.56 GB, DSC: 125.85 FPS/6.66 GB, PVDSC_G: 112.85 FPS/6.96 GB, PVDSC_L: 114.15 FPS/6.96 GB. The slightly higher memory usage of DSC and PVDSC arises from additional intermediate tensors during depthwise separable convolution and preference modulation, which scale with batch size. These FPS values are indicative only, as our custom kernels are experimental and not fully optimized; actual performance may differ on optimized hardware or embedded devices.

For convergence behavior, Conv reaches stability the earliest (205 epochs), followed by DSC (226 epochs). PVDSC_G and PVDSC_L require more epochs (261 and 297), reflecting the additional optimization introduced by the preference parameters. As shown in Figure 9, PVDSC variants converge more gradually yet ultimately achieve higher performance.

Figure 9.

Training curves of (a) mAP@50 and (b) mAP@50:95 for Conv, DSC, PVDSC_G, and PVDSC_L in YOLOv8s. PVDSC variants show slower yet more stable convergence, achieving higher final accuracy.

Overall, the PVDSC modules deliver a strong trade-off between accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency. They outperform DSC and surpass Conv under high-IoU evaluation metrics, demonstrating their effectiveness for efficient and precise object detection.

4.5.3. Analysis of Precision

Figure 10 presents the precision–confidence curves for all categories using four models: standard convolution (Conv), depthwise separable convolution (DSC), and PVDSC with Gaussian (PVDSC_G) or Laplace activation (PVDSC_L). DSC slightly improves precision over Conv at very low confidence for some easily distinguishable categories, but exhibits noticeable fluctuations at higher confidence levels, indicating less stable predictions and limited discriminative ability in challenging scenarios. In contrast, PVDSC consistently enhances both precision and stability: both PVDSC_G and PVDSC_L show rapid precision improvement at low confidence and maintain high precision across the full confidence range, with smaller fluctuations compared to DSC. PVDSC_L generates stronger responses for certain categories due to the sharper Laplace peak, which emphasizes subtle inter-class differences, whereas PVDSC_G, with its smoother Gaussian peak, produces more consistent precision across categories and favors generalization. These results highlight the effectiveness of preference-guided convolution in enabling filters to selectively focus on semantically relevant features, improving classification reliability across different confidence levels, and mitigating the instability observed in DSC, especially when distinguishing visually similar objects or handling complex backgrounds.

Figure 10.

Precision–confidence curves for each model using a different convolution module. Each line corresponds to one object category.

4.5.4. F1-Score Curve Analysis

Following the observation that preference-guided convolutions raise precision but slightly reduce recall, we further examine their overall balance using F1-score curves (Figure 11). As shown in Figure 11a, the comparison of all-class F1 curves reveals that both PVDSC variants achieve higher and more stable performance than the baseline DSC across confidence thresholds. DSC attains a peak F1 of 0.87 at a confidence of 0.489, while PVDSC_G and PVDSC_L both reach 0.88 at 0.507 and 0.568, respectively. Despite similar peak values, the preference-guided models maintain higher F1 scores over a wider confidence range—PVDSC_G performs better in low-confidence regions, and PVDSC_L achieves stronger results at high confidence levels—indicating a better precision–recall equilibrium overall. In contrast, DSC shows larger fluctuations and steeper declines at both ends, reflecting less stable confidence calibration.

Figure 11.

F1-score curves across confidence thresholds for different convolution modules: (a) overall comparison of all-class curves; (b–d) per-class F1 curves for DSC, PVDSC_L, and PVDSC_G.

Figure 11b–d further display per-class F1 curves. The DSC model exhibits uneven class-wise performance, whereas both PVDSC variants yield more compact and consistent trajectories, suggesting enhanced inter-class balance. Among them, PVDSC_L provides sharper discrimination at high confidence, while PVDSC_G offers smoother, more uniformly distributed responses. These results verify that introducing preference-guided convolution improves the model’s decision stability and maintains a higher overall F1 balance, complementing the precision–recall trade-off observed earlier.

4.5.5. Analysis of Similar-Class and Background Detections

This section analyzes how preference-guided convolutions affect detections of visually similar categories and background regions. Figure 12 compares DSC with PVDSC_G and PVDSC_L using confusion matrices, while Table 5 summarizes false positives among bottle-related categories and background.

Figure 12.

Confusion matrices for DSC and preference-guided PVDSC variants. Diagonal elements represent correct predictions, off-diagonal elements indicate misclassifications.

Table 5.

False positives among bottle-related categories and background. Values in PVDSC columns indicate absolute counts and relative change vs. DSC.

Both PVDSC variants substantially reduce false positives compared to DSC: total counts drop from 143 to 102 (↓29%) with PVDSC_G and to 98 (↓31%) with PVDSC_L. PVDSC_L achieves the best results for similar bottle types—for instance, misclassifications from bottle-glass to bottle-plastic fall from 20 to 9 (↓55%), and from bottle-plastic to gym-bottle from 13 to 6 (↓54%). Background confusions also decrease notably, from 83 (DSC) to 57 (PVDSC_G, ↓31%) and 59 (PVDSC_L, ↓29%).

Across all categories, inter-class misdetections decline from 154 (DSC) to 124 (PVDSC_G, ↓19%) and 136 (PVDSC_L, ↓12%), while background-induced false detections reduce from 185 to 151 (↓18%) and 157 (↓15%), respectively. Although missed detections slightly increase (↑14% and ↑11%), this reflects a more conservative prediction strategy favoring precision over recall.

Overall, preference-guided convolutions improve fine-grained discrimination and suppress background noise, leading to more stable and reliable detection behavior.

4.5.6. Generalization and Model Transfer Experiments

To further validate the effectiveness and transferability of the proposed PVDSC module, we conducted experiments by integrating it into different YOLO architectures to demonstrate that PVDSC consistently improves performance when replacing standard convolution modules, highlighting its applicability across multiple backbones. Specifically, in YOLOv5s, YOLOv10s, and YOLOv11s, the original convolutional layers were replaced with either standard DSC or PVDSC. The replacement positions are layers 3, 5, 7, 18, 21 for YOLOv5s; layers 3, 19 (Conv), and 5, 7, 20 (SCDown) for YOLOv10s; and layers 3, 5, 7, 17, 20 for YOLOv11s. The PVDSC variants employ Gaussian-type activation functions. Experimental results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of DSC and PVDSC (Gaussian-type) integrated into different YOLO models.

From the results, it can be observed that integrating PVDSC consistently improves performance compared to standard DSC across YOLOv5s, YOLOv10s, and YOLOv11s, while introducing only a minor increase in parameters and computation. This demonstrates that PVDSC consistently outperforms standard DSC across multiple YOLO backbones and, while incurring only marginal increases in parameters and FLOPs relative to DSC, is able to approach the detection accuracy of the original Conv-based YOLO models.

4.5.7. Evaluation on Additional Benchmark Datasets

To further assess the generalizability of the proposed PVDSC module, we conducted supplementary experiments on two benchmark datasets: the Bird Subset of the Animals Detection Images Dataset [38] and the WaRP Dataset [39].

The original Animals Detection Images Dataset contains multiple animal categories. We extracted all images containing at least one instance of 12 bird species: Eagle, Sparrow, Magpie, Goose, Duck, Canary, Raven, Swan, Owl, Parrot, Woodpecker, and Penguin. After removing corrupted or mislabeled samples, the resulting Bird Subset contains 3869 images with preserved bounding-box annotations. This subset provides a diverse and challenging fine-grained detection setting due to substantial intra-class variation and inter-class visual similarity.

The WaRP Dataset (Waste Recycling Plant) is a standardized benchmark for industrial waste detection. We selected 28 recyclable waste categories, including 17 types of plastic bottles (bottle- prefix), 3 glass bottles (glass- prefix), 2 cardboard types, 4 detergent types, canisters, and cans. The -full postfix indicates bottles filled with air. The WaRP-D subset contains 2452 training images and 522 validation images, each with 1920 × 1080 resolution.

We evaluated three models—YOLOv8 (Conv), YOLOv8_DSC, and YOLOv8_PVDSC_G using identical training configurations on both datasets. Each model was trained five times to account for randomness. Both the best single-run performance and the mean ± standard deviation across runs are reported in Table 7.

Table 7.

Performance comparison of Conv, DSC, and PVDSC_G on Bird Subset and WaRP Dataset.

Across all metrics, PVDSC-G consistently outperformed DSC and approached the accuracy of standard convolution-based YOLOv8 on both datasets. The improvements are particularly evident in mAP@50:95, indicating that the preference-value refinement mechanism effectively enhances fine-grained discrimination across visually similar categories. These findings demonstrate that PVDSC maintains strong generalization ability beyond the primary dataset and is effective in multi-instance, visually similar detection scenarios.

4.5.8. Visualization of Detection Results and Heatmaps

To further demonstrate the effectiveness of PVConv in distinguishing visually similar targets and suppressing background interference, we visualize the detection results (Figure 13) and Grad-CAM++ [40] heatmaps of YOLOv8s, YOLOv8s-DSC, and YOLOv8s-PVDSC_L across three datasets: the main dataset, the Bird Subset, and the WaRP Dataset. Grad-CAM++ generates more continuous and informative activation maps, highlighting the regions most attended to by the model.

Figure 13.

Detection results of YOLOv8s, YOLOv8s-DSC, and YOLOv8s-PVDSC_L on three datasets. PVConv effectively suppresses distractors and improves localization accuracy compared to Conv and DSC-based models.

As highlighted in the visualizations (Figure 14), standard convolution and DSC-based models are easily misled by visually similar distractors, resulting in false detections. In contrast, PVConv consistently suppresses such interference by learning preference-guided feature responses that emphasize the most discriminative attributes of the true targets. Although confidence scores may be slightly lower in some cases, PVConv achieves more stable and accurate localization across all datasets. The PVDSC_L variant, in particular, exhibits more compact and focused heatmap activations on the actual target regions.

Figure 14.

Grad-CAM++ heatmaps of YOLOv8s, YOLOv8s-DSC, and YOLOv8s-PVDSC_L for the three datasets. Ellipses indicate visually similar distractors in baseline models, while no annotations are shown for the WaRP Dataset due to its higher complexity. PVConv focuses on the most discriminative target regions and suppresses background interference.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this work, we propose a novel convolution module, PVConv, which introduces a preference-guided mechanism to enhance feature fusion within depthwise separable convolution (DSC). Unlike conventional pointwise convolution that aggregates channels uniformly, PVConv enables each filter to selectively focus on different feature distributions, thereby improving the granularity and discriminative power of feature representations while maintaining a lightweight computational profile. By integrating PVConv into DSC, we construct the PVDSC module and evaluate its performance within the YOLOv8 framework on the Beverage Containers dataset, which contains visually similar categories of objects relevant to applications in waste management, recycling, and environmental monitoring.

Experimental results show that PVDSC achieves superior performance under high IoU thresholds (mAP@50:95), reflecting more accurate and robust object localization. Analyses of precision curves and confusion matrices further reveal that incorporating preference-guided information into DSC leads to more cautious and discriminative detection behavior: PVDSC significantly reduces misclassifications among visually similar categories and suppresses false positives in complex backgrounds, while exhibiting a slight increase in missed detections due to higher precision. Correspondingly, F1-score curve analysis confirms that this balance results in higher overall stability, as PVDSC maintains superior F1 scores across a wide range of confidence thresholds, indicating an improved precision–recall equilibrium. Grad-CAM++ visualizations illustrate that PVConv provides each filter with a “selective viewing perspective,” enabling the model to focus on true target regions and enhancing interpretability. These results not only validate the module’s effectiveness but also highlight its real-world potential in practical scenarios where accurate discrimination of visually similar objects is critical, such as monitoring recycling streams, managing beverage container waste, or supporting automated public health inspections.

Future work will focus on improving the efficiency of nonlinear activation functions, exploring more sophisticated preference extraction strategies (such as continuous curve fitting), and extending preference-guided feature fusion to other network components, including convolutional blocks, attention modules, and transformers, aiming to further enhance inference efficiency and broaden the applicability of the approach. Overall, PVDSC effectively addresses the limitations of standard DSC in spatial information integration, enhances fine-grained feature discrimination, and demonstrates strong potential for deployment in real-world vision systems that require accurate recognition of similar objects in cluttered or dynamic environments, thus bridging the gap between methodological innovation and practical impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.P. and X.Q.; methodology, W.P. and B.L.; validation, W.P., B.L., and Y.Z.; formal analysis, W.P.; investigation, W.P. and B.L.; data curation, W.P.; writing—original draft preparation, W.P.; writing—review and editing, X.Q., Y.Z., and B.L.; visualization, W.P.; supervision, X.Q.; project administration, P.W. and H.H.; funding acquisition, P.W. and H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Equipment Development Department of the People’s Republic of China Central Military Commission, grant number 62502010223, and by the Department of Science and Technology of Jilin Province Key R&D Project, grant number 20230201097GX.

Data Availability Statement

Data are openly available in the Roboflow Universe repository “Beverage Containers > YOLOv8” at https://universe.roboflow.com/roboflow-universe-projects/beverage-containers-3atxb (accessed on 24 October 2025), provided by a Roboflow user under the CC BY 4.0 license. The Animals Detection Images Dataset is available on Kaggle at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/antoreepjana/animals-detection-images-dataset (accessed on 29 November 2025), provided under the Kaggle Terms of Use. The WaRP Dataset (Waste Recycling Plant) is publicly accessible via its publication at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0952197623017268 (accessed on 3 December 2025) [39], which includes 28 recyclable waste categories with labeled bounding boxes, provided under the publisher’s terms.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the support provided by their institutions.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Ping Wang and Huiping Huang were employed by Avic Xi’an Aircraft Industry Group Co., Ltd. The company provided project administration and funding for this research but had no role in study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2012; Pereira, F., Burges, C., Bottou, L., Weinberger, K., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Nice, France, 2012; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, D.; Kil, D.; Kim, S.h. A Survey on Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks and Hardware Acceleration. Electronics 2022, 11, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet: An Extremely Efficient Convolutional Neural Network for Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. GhostNet: More Features From Cheap Operations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; Chaudhuri, K., Salakhutdinov, R., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 97, pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.T.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet V2: Practical Guidelines for Efficient CNN Architecture Design. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, B.; Ding, Y. DSXplore: Optimizing Convolutional Neural Networks via Sliding-Channel Convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS), Portland, OR, USA, 17–21 May 2021; pp. 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Amthor, M. Rethinking Depthwise Separable Convolutions: How Intra-Kernel Correlations Lead to Improved MobileNets. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Jian, M.; Wang, G.G. ConvUNeXt: An efficient convolution neural network for medical image segmentation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 253, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; Yao, L. LMFRNet: A Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network Model for Image Analysis. Electronics 2024, 13, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Nex, F.; Vosselman, G.; Kerle, N. Lite-Mono: A Lightweight CNN and Transformer Architecture for Self-Supervised Monocular Depth Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 18537–18546. [Google Scholar]

- Maaz, M.; Shaker, A.; Cholakkal, H.; Khan, S.; Zamir, S.W.; Anwer, R.M.; Shahbaz Khan, F. EdgeNeXt: Efficiently Amalgamated CNN-Transformer Architecture for Mobile Vision Applications. In Computer Vision, Proceedings of the ECCV 2022 Workshops, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Karlinsky, L., Michaeli, T., Nishino, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. RepViT: Revisiting Mobile CNN From ViT Perspective. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 15909–15920. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Yue, X. Scaling Up Your Kernels: Large Kernel Design in ConvNets Toward Universal Representations. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 11692–11707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, J. ShiftwiseConv: Small Convolutional Kernel with Large Kernel Effect. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025; pp. 25281–25291. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Qi, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y. Deformable Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, M.G.d.; Fawcett, R.; Prisacariu, V.A. DSConv: Efficient Convolution Operator. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Chen, C.W. Optimized separable convolution: Yet another efficient convolution operator. AI Open 2022, 3, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Song, T.; Yang, D.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L. LDConv: Linear deformable convolution for improving convolutional neural networks. Image Vis. Comput. 2024, 149, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Marculescu, R. RapidNet: Multi-Level Dilated Convolution Based Mobile Backbone. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 8302–8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, W.; Luo, B.; Wang, G. Depth-Wise Convolutions in Vision Transformers for efficient training on small datasets. Neurocomputing 2025, 617, 128998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wu, W.; Liu, K. Toward New Retail: A Benchmark Dataset for Smart Unmanned Vending Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 7722–7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B.; Sazonov, E. Enhancing Egocentric Insights: Comparison of Deep Learning Models for Food and Beverage Object Detection from Egocentric Images. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Sensing and Instrumentation in 5G and IoT Era (ISSI), Lagoa, Portugal, 29–30 August 2024; Volume 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning With Depthwise Separable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Broomhead, D.S.; Lowe, D. Radial basis functions, multi-variable functional interpolation and adaptive networks. Complex Syst. 1988, 2, 321–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, J.; Krogh, A.; Palmer, R.G. Introduction to the Theory of Neural Computation; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. In Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning, Lille, France, 7–9 July 2015; Bach, F., Blei, D., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 37, pp. 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Projects, R.U. Beverage Containers Dataset. 2024. Available online: https://universe.roboflow.com/roboflow-universe-projects/beverage-containers-3atxb (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Antoreepjana. Animals Detection Images Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/antoreepjana/animals-detection-images-dataset (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Yudin, D.; Zakharenko, N.; Smetanin, A.; Filonov, R.; Kichik, M.; Kuznetsov, V.; Larichev, D.; Gudov, E.; Budennyy, S.; Panov, A. Hierarchical waste detection with weakly supervised segmentation in images from recycling plants. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhay, A.; Sarkar, A.; Howlader, P.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Grad-CAM++: Generalized Gradient-Based Visual Explanations for Deep Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).