Abstract

In the case of small disturbances in the power grid, virtual synchronous generators (VSGs) often exhibit active power steady-state errors and significant frequency overshoot, and it is difficult to balance the reduction of active power steady-state errors and the mitigation of frequency overshoot. This paper proposes an improved control method based on active power differential compensation (APDC). First, an active power differential compensation loop is introduced, effectively addressing the issues of active power steady-state deviation and frequency overshoot caused by fixed parameters in the traditional VSG. Secondly, by incorporating a fuzzy logic control (FLC) algorithm, an adaptive PID tuning strategy is proposed as a replacement for the traditional fixed virtual inertia; the PID parameters are dynamically adjusted in real time according to the power–angle deviation and its rate of change, thereby enhancing the small-disturbance dynamic performance of the VSG. Finally, MATLAB R2020b/Simulink simulations and StarSim hardware-in-the-loop simulations validate the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed control strategy. Simulation results indicate that, compared to traditional control strategies, under peak regulation conditions, the frequency overshoot is reduced by approximately 4.4%, and the active power overshoot is reduced by approximately 5%; under frequency regulation conditions, the frequency overshoot is reduced by approximately 0.26%, and the power overshoot is reduced by approximately 12%.

1. Introduction

Currently, renewable energy power generation has seen large-scale development, particularly in the photovoltaic (PV) sector where the cumulative installed capacity approaches 1 terawatt [1]. Renewable energy generation units are progressively being integrated into the grid at scale through inverters [2,3]. However, traditional photovoltaic systems employ grid-following control strategies, where inverters rely on external voltage support and lack inherent inertia and damping characteristics. The operational behavior of photovoltaic systems is significantly influenced by environmental factors. When subjected to disturbances, inverters have a limited capability to suppress power and frequency fluctuations, leading to system instability [4,5,6,7]. To address this issue, scholars have proposed the VSG control technology [8]. By emulating the inertia and damping characteristics similar to those of synchronous generators, VSG enables inverters to effectively resist grid frequency variations and active power fluctuations, thereby providing robust support for the stable operation of the power grid [9,10,11,12,13,14].

For key parameters in VSG control such as inertia J and damping coefficient D, the existing literature indicates that fixed parameters significantly affect the system’s output characteristics, manifesting as overcharging and oscillations while introducing steady-state errors [15,16]. Reference [15] indicated that when the grid angular frequency remains constant and the active power command undergoes a sudden change, the large J in traditional control strategies leads to significant power oscillations in the system while excessively supporting the VSG output frequency, causing frequency overshoot. When the grid angular frequency fluctuates, insufficient damping fails to suppress active power oscillations, whereas excessive damping results in increased steady-state deviations in active power. Therefore, to address the small-signal disturbance issues in traditional VSG, scholars both domestically and internationally have conducted further research. Reference [16] established a small-signal mathematical model of the VSG and determined the range of the damping coefficient, proposing an adaptive damping control strategy for the microgrid VSG based on the relationship between the damping and the maximum frequency deviation. Reference [17] analyzed the voltage phasor relationship of the micro–source–grid system under signal disturbances with the introduction of virtual impedance, proposing an adaptive virtual impedance control strategy to accelerate the active power regulation process of the VSG system. Reference [18] proposed two transient compensation-based VSG power oscillation suppression strategies, effectively mitigating VSG active power oscillations without causing steady-state deviations. Additionally, intelligent algorithms such as fuzzy control [19], deep learning [20], and radial basis functions [21,22] have been applied to optimize VSG control parameters, achieving decoupling between parameters and enabling adaptive compensation of system damping and virtual inertia with changes in system frequency or power, further enhancing system dynamic performance.

In addition to optimizing the key parameters, the existing research has also explored the active power of photovoltaic-storage VSG systems. Reference [23] designed a VSG system integrating energy storage, fully considering the dynamic characteristics of battery energy storage. They proposed an improved control strategy based on a radial basis function (RBF) neural network. This strategy accommodates the time-varying characteristics of the state of charge (SOC), approximating the nonlinear functional relationship between the SOC change rate and battery current via the RBF neural network, thereby achieving mechanical power regulation in the APL. References [24,25] employed model predictive control (MPC), constructing an objective function using the frequency deviation and rate of change of frequency as performance metrics. By dynamically adjusting the weighting factors of this objective function, they derived optimal active power adjustment values for APL. However, merely adjusting the active power regulation strategy within the APL cannot fundamentally resolve system instability caused by disturbance conditions. To address the challenges of power overshoot and frequency overshoot, comprehensive consideration must be given in conjunction with key parameter adjustments. Moreover, Reference [26] also introduced the photovoltaic simulation model and data.

The existing research lacks sufficient consideration for power overshoot and frequency overshoot issues under small-signal disturbances in the system. This paper proposes a VSG control strategy based on the APDC algorithm. Firstly, the inherent contradiction in the selection of the damping coefficient and rotational inertia for traditional VSG is analyzed. This contradiction is resolved by introducing the APDC algorithm into the active power-frequency control loop, thereby enhancing the system’s response capability to small disturbances. Building upon this, a virtual inertia adaptive adjustment strategy is designed by combining the FLC algorithm. This strategy dynamically sets the virtual inertia value through a real-time adjustment based on the system’s angular speed and its rate of change. Finally, the effectiveness of the VSG control strategy under the APDC with FLC algorithm in a photovoltaic storage system is verified using MATLAB/Simulink and StarSim hardware-in-the-loop experimental platforms.

2. VSG System Control

2.1. VSG Model for Photovoltaic Storage Systems

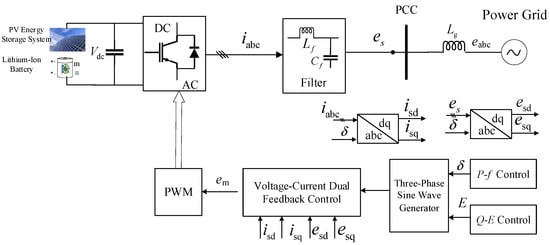

The traditional photovoltaic energy storage system with VSG model is shown in Figure 1. The photovoltaic energy generation unit is connected to the DC side of the inverter and integrates into an infinite grid via the point of common coupling, iabc and eabc represent the grid current and grid voltage, Cf is the filtering capacitor, and es is the PCC voltage. The grid current is and the PCC voltage es are transformed through dq transformation into isd, isq, esd, and esq, which are then sent to the voltage–current double closed-loop controller, ultimately generating the PWM modulation voltage. Lf is the filtering inductance and Lg is the line inductance, and δ is the phase displacement between the point-of-common-coupling voltage es and the grid voltage eabc, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the photovoltaic energy storage VSG circuit.

In traditional photovoltaic energy storage VSG, for excitation control considerations, the active-frequency control loop simulates the rotor motion equation, expressed as:

where Pref is the active power reference setpoint for the VSG; Pe denotes the electromagnetic power output of the VSG; J is the virtual inertia; D is the damping coefficient; Kω is the active droop coefficient; ω0 is the rated angular frequency of the grid; and ω is the output angular frequency of the VSG. Meanwhile, the reactive voltage control equation is given by:

where E is the VSG voltage magnitude; E0 is the voltage reference magnitude; Kq is the reactive power droop coefficient; Qref is the reactive power reference setpoint; and Qe is the actual output reactive power.

2.2. Traditional VSG Control Structure

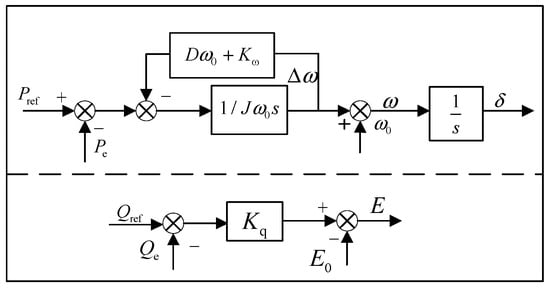

The control structure of this photovoltaic storage-based VSG includes active power-frequency and reactive power-voltage loops, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

VSG control diagram for photovoltaic and energy storage.

According to the principle of power transmission balance in the grid, neglecting the effects of the filtering capacitors, inductances, and line resistances, the active power Pe delivered by the photovoltaic energy storage unit to the grid is given by:

where Ug is the magnitude of the grid voltage; ωg is the angular frequency of the grid; δ is the phase difference between the VSG output voltage and the grid voltage, defined as the power angle; X is the equivalent line reactance; K = UgE/X; and s is the differential operator.

Based on the active-frequency closed-loop control structure in the control block diagram of Figure 2, the impact of a change in the power reference Pref or disturbances in the grid angular frequency ωg on the electromagnetic power Pe can be expressed using a transfer function as follows for Gω.VSG, GP.VSG:

where ΔPref is the steady-state deviation of the active power reference; ΔPe denotes the steady-state deviation of the electromagnetic power; and Δωg is the variation in grid frequency. Based on the above Equation (4), the damping ratio ξ and the natural oscillation frequency ωn can be expressed as:

When the photovoltaic energy storage VSG is connected to the grid to participate in frequency regulation, the output active power experiences a steady-state error ΔPe due to the droop characteristics, which can be expressed as:

According to Equation (5), it is known that if J remains constant, increasing D will enhance the damping ratio ξ, which is beneficial for system stability. However, if D is set overly high, it will lead to an increase in the steady-state deviation of the active power output during frequency regulation. If D = 0, the coupling effect between damping and the droop coefficient Kω on the steady-state error of the output power is eliminated. When D is held constant, increasing J results in a decrease in the natural oscillation frequency ωn, thereby enhancing the VSG’s ability to withstand frequency variations. However, an increase in J reduces ξ, leading to more pronounced system oscillations. Therefore, adjusting only the values of D and J cannot adequately balance the transient and steady-state characteristics of the photovoltaic energy storage VSG system.

3. Improved APDC Algorithm for Photovoltaic Energy Storage VSG Control Strategy

3.1. APDC Algorithm Based on VSG

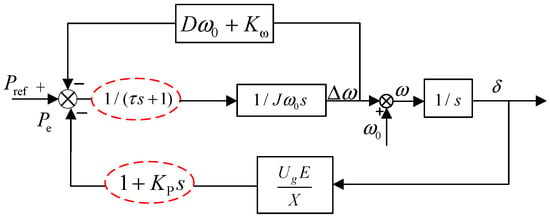

To effectively reduce the steady-state error of active power in photovoltaic energy storage VSG while suppressing frequency overshoot and active power oscillations during small disturbances, an improved active power-frequency control strategy based on the APDC algorithm is proposed. As illustrated in Figure 3, this strategy introduces a differential operation in the electromagnetic power negative feedback loop to smooth power fluctuations, thereby adaptively reducing steady-state active power errors. Additionally, a first-order low-pass filter is incorporated to mitigate high-frequency harmonic signals generated by the differential operation and to enhance the system’s inertial characteristics against grid frequency variations. In this context, Kp is the differential compensation coefficient, and τ denotes the time constant of the low-pass filter. To attenuate the effects of high-frequency noise and avoid inducing instability in the system, the VSG integrated with active differential compensation and a first-order delay element is referred to as APDC–VSG. Consequently, the rotor motion of the APDC–VSG is given by Equation (7).

Considering the challenges of implementing a differential component in engineering practice, the first-order high-pass filter Fv(s) is used in conjunction with the proportional component to replace the differential element within the switching frequency range.

Figure 3.

Active power-frequency control loop of PV and storage VSG based on APDC algorithm.

In this context, M denotes the parameter of the first-order high-pass filter corresponding to the cutoff frequency of fs/2, and fs is the sampling frequency, and its expression is given by:

The opened-loop and closed-loop transfer functions for active power control of APDC–VSG under active power disturbances and grid frequency disturbances are established as follows:

Based on Equation (10), it is evident that, since the value of K is typically large, introducing a smaller differential coefficient Kp can alter the pole distribution of the closed-loop transfer function, thereby affecting the transient stability of the system.

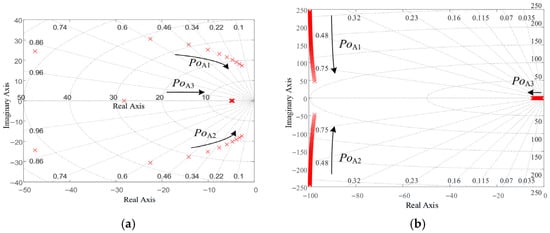

Figure 4 illustrates the pole distribution of the active power closed-loop transfer function for the APDC–VSG with varying values of Kp and τ when J = 2. As shown in Figure 4a, when Kp = 0.01, τ is increased from 0 to 0.01 with a compensation step of 0.001. The dominant poles POA1 and POA2 consistently move closer to the imaginary axis to the zero point, while POA3 approaches the imaginary axis from the −30 to 10 on the real axis along the real axis, with all three poles remaining in the left half-plane of the complex plane. The numerical values of POA3 remain less than the real values of the conjugate poles POA1 and POA2, with the damping ratios of POA1 and POA2 gradually decreasing. This indicates that the increase in τ is detrimental to system stability, as poles approaching the imaginary axis imply a reduced oscillation attenuation capability and slower transient convergence speed, weakening the system’s damping characteristics.

Figure 4.

Pole distribution diagram of APDC–VSG. (a) Pole distribution with variation τ. (b) Pole distribution with variation Kp.

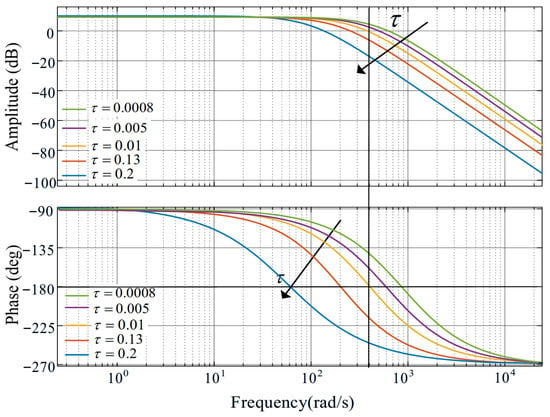

Therefore, in practical applications in Equation (10), it can be seen that GO.P.VSG depends solely on the time constant τ. The time constant τ can be directly tuned from the open-loop Bode diagram of the active-power loop, shown in Figure 5. An inspection of the magnitude trace reveals that raising τ progressively attenuates the high-frequency gain, i.e., the system amplifies high-frequency signals less and therefore rejects disturbances more strongly. Simultaneously, the phase trace steepens with increasing τ; the faster the phase drop, the smaller the phase margin and the heavier the suppression of high-frequency noise concomitantly. Nevertheless, at τ = 0.13, the phase margin already collapses to 0° where the system reaches a critically stable state. Any further increase drives the margin value to become negative and destabilizes the loop. Consequently, both the root–locus plot of Figure 4 and the Bode data of Figure 5 dictate that τ be kept small enough to preserve stability. In practice, τ is therefore chosen to use roughly one hundred switching periods to balance stability and a high-frequency disturbance rejection performance. In this paper, τ = 0.005 s.

Figure 5.

Bode diagram of APDC–VSG active power open-loop system when τ changes.

In Figure 4b, with τ = 0.005, Kp is increased from 0 to 1 in steps of 0.01. The dominant pole POA3 slightly moves away from the imaginary axis near the zero point, while the root locus of POA1 and POA2 exhibits a symmetrical distribution, gradually approaching the real axis in an approximately vertical manner. The system’s damping ratio increases rapidly, indicating that the increase in Kp is beneficial for system stability. However, it simultaneously weakens the dynamic response performance, such as through a slower response speed and compromised command tracking rapidity. Therefore, selecting an appropriate value for Kp is crucial for optimizing the transient response characteristics of the system.

3.2. Optimal Design of Kp via Particle Swarm Optimization in Electrical Engineering

Based on the preceding analysis, the selection of Kp plays a decisive role in enhancing system stability, whereas a sufficiently small τ renders the influence of the high-order differential terms in the transfer function negligible; consequently, Equation (7) can be equivalently reduced to a second-order closed-loop system model.

By reducing the model to second order, Kp can be determined using canonical second-order tuning rules, whereby the resulting natural angular frequency ωn1 and damping ratio ξ1 are expressed as follows:

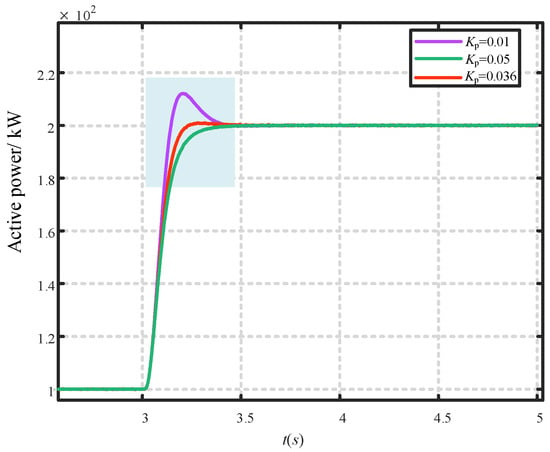

To meet practical engineering requirements, an objective function F is formulated by optimizing two key dynamic performance indices, system rise time and active overshoot, where α ∈ [0, 1] is a weighting coefficient, e is typically set to 0.02 (2%) of the steady-state error allowed by the system, γ is the phase margin, and h is the gain margin. Assuming equal priority between the two conflicting objectives—active overshoot and rise time—α = 0.5. Substituting Equations (10) and (14) into the cost function, the particle-swarm optimizer is executed to minimize F, yielding the globally optimal proportional gain Kp = 0.036.

Figure 6 demonstrates that when the active power is step-changed from 100 kW to 200 kW at t = 3 s, the controller tuned with Kp = 0.036, obtained via the proposed particle swarm optimization, simultaneously minimizes overshoot and maximizes response speed, thereby achieving the best dynamic trade-off. In contrast, a smaller gain (Kp = 0.01) shortens the rise time yet markedly increases overshoot, whereas a larger gain (Kp = 0.05) eliminates overshoot at the expense of a sluggish response. These results corroborate that the PSO-based framework efficiently resolves the optimal Kp selection problem, offering a novel and effective paradigm for parameter design in power electronics-dominated systems.

Figure 6.

Comparative transient response of active power output for different Kp values.

4. FLC-Based Flexible Virtual Inertia Control for APDC–VSG

4.1. Relationship Between Power–Angle Dynamics and Virtual Inertia in VSGs

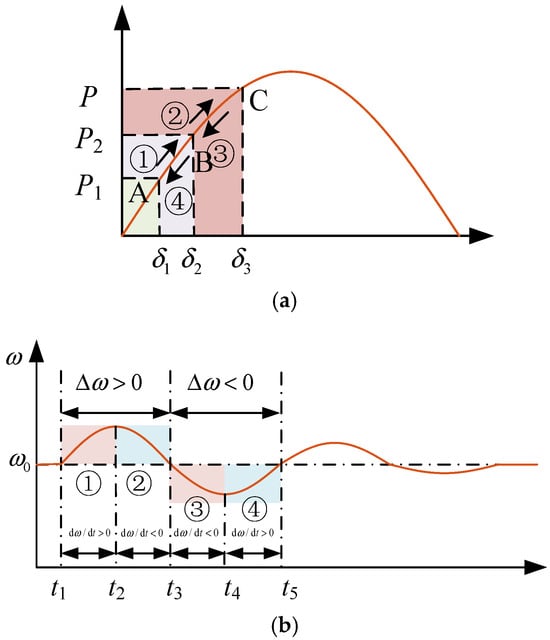

In this study, VSG is shown to exhibit power–angle dynamics analogous to those of a conventional synchronous machine. Figure 7 illustrates the trajectory of the power angle δ versus the angular frequency deviation Δω. Following a step change in the active-power reference from P1 to P2, the system undergoes four distinct oscillatory phases (B→C, C→B, B→A and A→B) before converging to the stable equilibrium point B.

Figure 7.

Synchronous generator power–angle and angular frequency–variation curves. (a) Power–angle curve. (b) Frequency oscillation curve.

Phase ①: The angular frequency experiences a rapid upsurge, with ∆ω = (ω–ω0) > 0, while the rate of change of frequency dω/dt initially rises and subsequently decays to 0. Augmenting the virtual inertia J during this interval attenuates the peak dω/dt, thereby suppressing ∆ω, the initial swing magnitude.

Phase ②: The ω declines and the dω/dt becomes negative, indicating a deceleration period ∆ω = (ω–ω0) > 0. Temporarily reducing J in this phase enlarges the dω/dt, accelerating ω toward ω0. Moreover, Phases ③ and ④ employ the same principles as the analysis described above. The results of the selection rules for J are consolidated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selection rules for J under different dynamic processes.

To further enhance the dynamic stability of the VSG, the preceding analysis indicates that a judicious design of the virtual inertia J can significantly reinforce the frequency–support capability of the ADPC–VSG. Nevertheless, conventional VSG implementations employ a constant J, which is incapable of increasing when the frequency deviates from its nominal value so as to curb the maximum excursion, or of decreasing adaptively when the frequency returns toward the nominal value so as to shorten the settling interval. In order to simultaneously mitigate the peak frequency deviation and accelerate the recovery time objectives that are inherently contradictory under a fixed–J paradigm, this paper proposes a fuzzy PID controller algorithm that treats the frequency error and its time derivative as real-time inputs, thereby enabling an on-line, adaptive modulation of J, and, consequently, a pronounced enhancement of the system’s dynamic stability.

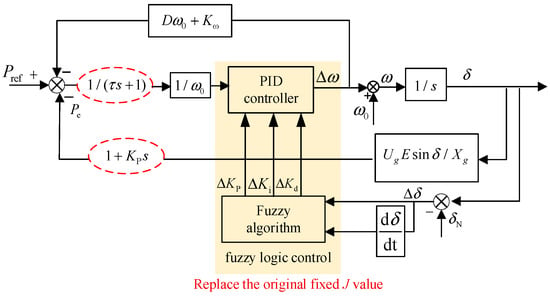

4.2. Fuzzy PID Controller Structure Based on Active Power-Frequency Loop Control

In various control systems, PID control offers high control accuracy, robust performance, and an excellent dynamic tracking quality, making it widely used in various engineering practices. To ensure good power angle stability during fault conditions in GFM–VSC, the set input value δN and the actual feedback output value δ form the control deviation ∆δ, which adjusts and corrects the controlled variable, so that the actual output value of the controlled object, under the control of the PID algorithm, increasingly approaches the desired power angle setpoint, ultimately causing the deviation to approach zero.

For a virtual inertia value that is output reasonably, the mathematical model of the PID controller is as follows:

where u(t) is the input at time t, Kp is the proportional gain, Ki is the integral time, and Kd is the derivative coefficient. Since the control parameters of a traditional PID controller remain fixed once set, it can achieve the ideal performance when the system model parameters are time-invariant. However, when applied to time-varying or nonlinear systems, its lack of adaptive capability can lead to degraded system performance or even instability. To further enhance the dynamic performance of the transient response of GFM–VSC during faults, a fuzzy PID control algorithm is introduced in the control process, allowing the three PID parameters to better handle severe fault conditions.

Fuzzy PID control is based on conventional PID control, using error and the rate of change of error as the inputs, and adjusting or correcting the three output parameters of the PID controller in real-time according to the designed fuzzy control rules [27]. The key feature is that it does not rely on precise modeling of the controlled object. Compared to traditional control methods, its stability and anti–interference ability are improved. It solves the problem of the inability to dynamically adjust output parameters in conventional PID control. The structure of the fuzzy PID controller is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Active power-frequency block diagram based on fuzzy PID control.

The fuzzy PID controller designed in this paper uses the output angular velocity deviation ∆ω and deviation rate of change dω/dt from the VSC as input variables. Through the fuzzy control algorithm, the three physical increment parameters ∆Kp, ∆Ki, and ∆Kd are inferred. The control parameter expression is as follows:

4.3. Design of Fuzzy PID Controller

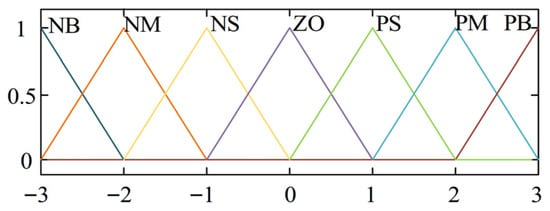

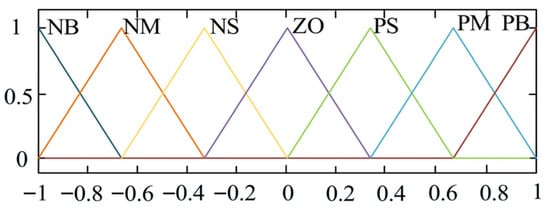

To design a fuzzy controller, the first step is to determine the domains of the output and input. The control input variables are selected as ∆ω and the rate of change of deviation dω/dt, while the output variables of the controller are the three parameter adjustments ∆Kp, ∆Ki, and ∆Kd. To facilitate the conversion between domains, the fuzzy domains for ∆δ and dδ/dt are chosen as [−3, 3]. For a more intuitive output quantity, the fuzzy domains for ΔKp, ΔKi, and ΔKd are defined as [−1, 1], [−0.5, 0.5], and [−0.01, 0.01], respectively, and to obtain an intuitive output, its fuzzy universe is set to [−1, 1], based on the model adjustment effects. The inputs and outputs of the fuzzy controller are defined as seven linguistic variables, with fuzzy subsets as {NB, NM, NS, ZO, PS, PM, PB}, where the variables represent negative large, negative medium, negative small, zero, positive small, positive medium, and positive large, respectively. Each input and output variables are adjusted through the values of quantization factors and scaling factors to transition between the basic domain and the fuzzy domain, while triangular membership functions are employed to quantify the designed linguistic variables. The membership functions for the input and output variables are illustrated in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Membership function graph of ∆δ and dδ/dt.

Figure 10.

Membership function graph of ∆Kp, ∆Ki, ∆Kd.

The reasonable design of fuzzy control rules is the core of the entire fuzzy controller. Through fuzzy rules, the fuzzy relationship between input and output can be determined.

The Mamdani inference method can map the fuzzy sets of input variables to the fuzzy sets of output variables, so the Mamdani inference method is chosen for fuzzy reasoning of the rules. Based on the different impacts of the three parameters Kp, Ki, and Kd on the system’s control characteristics, incorporating the practical control experience of relevant experts allows for the establishment of a fuzzy control rule regarding the relationship between the input and output parameters, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Fuzzy control rules table.

Defuzzification is the process of converting the fuzzy output set produced by fuzzy inference into a precise value. This paper adopts the centroid method for defuzzification, as this method yields stable control effects and provides clearer control values. The expression for it is as follows:

In the formula, μpj(∆Kp) is the combined membership degree of ∆Kp at point j, and the crisp values of ∆Ki and ∆Kd can also be derived using the above method.

5. Simulation Verification

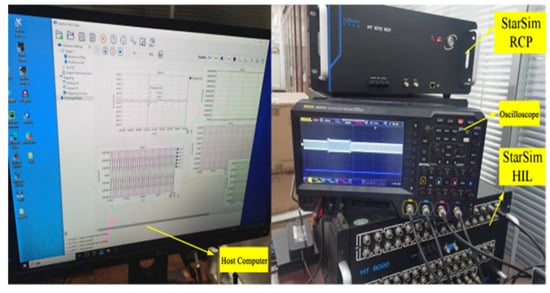

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed APDC–VSG-based control strategy integrated with fuzzy logic algorithm for the photovoltaic energy storage system, a simulation model adhering to the topology shown in Figure 1 is constructed in Matlab/Simulink. Further verification is conducted on the StarSim hardware-in-the-loop simulation platform, whose sampling frequency is 10 kHz, and real-time step is 1 × 10−5 s, as illustrated in Figure 11. The simulation parameters of the photovoltaic storage system are listed in Table 3.

Figure 11.

Semi-physical simulation experiment platform.

Table 3.

Simulation parameters.

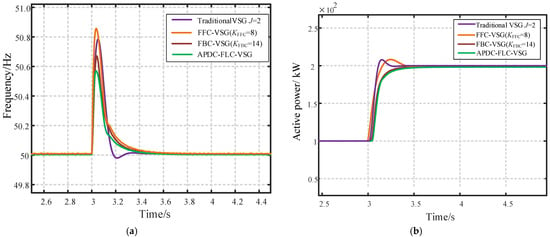

In the simulation, the rated capacity of photovoltaic storage is assumed to be 100 kVA, with an active power output command of Pref = 100 kW. The disturbance scenario is configured as follows: the grid frequency remains at 50 Hz, and at t = 3 s, the active power command increases abruptly from 100 kW to 200 kW due to load-demand variation.

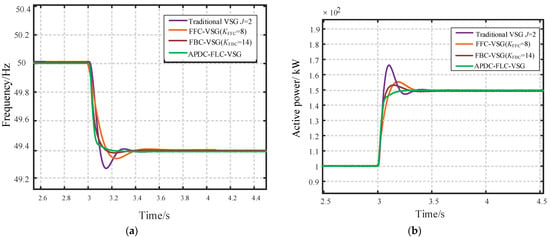

As shown in Figure 12a, when comparing the frequency variations between the traditional VSG and APDC–FLC control, the frequency peak of the traditional VSG is 50.78 Hz, while the frequency peak using the APDC–FLC control strategy is 50.56 Hz. The maximum frequency overshoots are 1.56% and 1.12%, respectively, and the adjustment times are 0.33 s and 0.35 s, respectively. It also outperforms the FFC and FBC strategies proposed in the literature [18]. By further optimizing the angular velocity ω output based on the optimal parameter Kp, it can be concluded that the frequency overshoot of the APDC–FLC control is smaller than that of the traditional VSG control, with a reduction of 4.4%.

Figure 12.

Comparison of active disturbance output results. (a) Frequency variation. (b) Active power output variation.

As shown in Figure 12b, if the traditional VSG control sets J = 2, it will cause an active power overshoot, with the active overshoot reaching 5%. However, using the APDC–FLC–VSG strategy results in no overshoot, with the overshoot reduced by approximately 5% compared to the traditional VSG. This indicates that the APDC–FLC–VSG strategy can effectively balance frequency regulation performance and active power overshoot suppression, achieving optimal adaptive inertia design. Furthermore, the APDC–FLC–VSG control can achieve oscillation-free frequency recovery, with its transient response reaching steady-state within approximately 3.5 s. This characteristic highlights the core advantage of the APDC–FLC–VSG control: it combines the low-frequency deviation characteristics of a high-inertia system with a dynamic response that is essentially oscillation-free during the recovery process, as Table 4 shows. This demonstrates that the APDC–FLC–VSG framework can effectively balance dynamic stability and response speeds, overcoming the inherent relationship between high inertia and increased power overshoot in traditional control, reducing the impact of grid power fluctuations on power electronics devices, and thus providing better protection for equipment with limited overcurrent tolerance.

Table 4.

Dynamic performance comparison under operating condition 1.

When the active power output command is Pref = 100 kW, the disturbance condition is set as follows: at 3 s, due to load-demand changes, the grid frequency drops from 50 Hz to 49.4 Hz. The comparison of system output results using various control strategies under this condition is shown in Figure 13a. When using the traditional VSG strategy with J = 2, the peak frequency decrease is 49.27 Hz, and the frequency overshoot reaches 0.26%. As shown in Figure 13b, when using the traditional VSG strategy, the peak active power overshoot is 168 kW, and the overshoot reaches 12%. However, there is no overshoot when using the APDC–FLC–VSG strategy. The results indicate that compared to the traditional VSG, the APDC–FLC–VSG control strategy performs prominently in frequency deviation suppression and power overshoot control. The frequency overshoot is reduced by approximately 0.26%, and the power overshoot is reduced by approximately 12%. Meanwhile, the adjustment times are 0.33 s and 0.14 s, respectively. Furthermore, its comprehensive performance is superior to the FFC and FBC strategies in Reference [18], making it the optimal control scheme in this comparison, as Table 5 shows.

Figure 13.

Comparison of frequency disturbance output results. (a) Frequency variation. (b) Active power output variation.

Table 5.

Dynamic performance comparison under operating condition 2.

Furthermore, the operational metrics of different control strategies under the afore-mentioned two operating conditions are summarized in Table 4 and Table 5. It is evident that the proposed control strategy achieves overall optimal performance across multiple operational metrics, validating its superiority and rationality.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes an optimized control strategy based on APDC–FLC–VSG. The strategy improves the dynamic response characteristics of the system under small disturbances and incorporates an FLC to design an adaptive control method for flexible virtual inertia regulation, thereby enhancing the transient stability of the photovoltaic storage system. The simulation and experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method offers the following advantages:

- (1)

- In the active power-frequency control loop, a derivative and first-order inertial element is introduced, and the APDC algorithm is applied to reconstruct the system transfer function. Additionally, a particle swarm optimization algorithm is employed to determine the optimal derivative coefficient Kp, and following a grid active-power change, the VSG active-power output reaches the commanded steady-state value within 0.4 s, exhibiting neither overshoot nor oscillation.

- (2)

- The proposed FLC–APDC–VSG control strategy requires the online evaluation of 49 fuzzy rules and a rolling update of PID gains; with an interrupt period of 100 μs, the measured CPU load is ≈ 42%. The computational burden grows exponentially with the number of rules or the swarm size; a table lookup-based order-reduction approach will be pursued next to cut the execution time.

- (3)

- Throughout the paper, the grid–side reactance Xg and filter inductance Lf are assumed to be exactly their nominal values; the robustness margin of the controller against ±20% parametric drifts has not been quantified. Moreover, this paper focuses exclusively on improving small-disturbance stability; no Lyapunov-strict stability proof is provided for large-disturbance scenarios. These topics are reserved for future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G.; methodology, F.G. and X.X.; software, W.H.; validation, X.L.; formal analysis, W.H. and Y.Z.; investigation, X.L.; resources, X.L. and Y.Z.; data curation, W.H.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G.; writing—review and editing, F.G. and X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, X.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2025JJ50231) and the Key Project of Hunan Vocational College of Engineering of China (GC21ZD03).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Martinho, F. Challenges for the future of tandem photovoltaics on the path to terawatt levels: A technology review. Energy Environ. 2021, 4, 3840–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhao, X.; Liang, J. A Novel Control Strategy to Enhance the Transient Performance of Grid–Forming Converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Xia, X.; Huang, X.; Zhao, X.; Deng, H.; Gong, Y.; Huang, R. Dynamic response characterization and multi–parameter cooperative control of virtual synchronous generator. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 247, 111839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, B. Active Disturbance Rejection Control Based Control Strategy for Virtual Synchronous Generators. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2020, 35, 747–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Tian, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y. An overview of stability studies of grid–forming voltage source converters. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2023, 43, 2339–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Z.; Jin, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. A weighted voltage model predictive control method for a virtual synchronous generator with enhanced parameter robustness. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2021, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Chen, Z.; Qian, W.; Zhou, S. A Virtual Synchronous Generator Low–Voltage Ride–Through Control Strategy Considering Complex Grid Faults. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.; Zheng, C.; Sun, H. Transient Stability mechanism analysis of the grid forming voltage source converter and the improved limiting method. Proc. CSEE 2023, 44, 3753–3765. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Yu, Z. Control of Virtual Synchronous Generator for Frequency Regulation Using a Coordinated Self–adaptive Method. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 10, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, S.; Fan, H.; Liang, J.; Yu, T.; Li, T.; Liu, J. Research on inertia coordinated control strategy of multiple VSG cells. J. Electr. Power Sci. Technol. 2024, 39, 170–180. [Google Scholar]

- Suvorov, A.; Askarov, A.; Ruban, N.; Rudnik, V.; Radko, P.; Achitaev, A.; Suslov, K. An adaptive inertia and damping control strategy based on enhanced virtual synchronous generator model. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Lan, T.; Dong, H. Control strategy and stability analysis of virtual synchronous generators combined with photovoltaic dynamic characteristics. J. Power Electron. 2019, 19, 1270–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Feng, X.; Guo, H. An adaptive control strategy for virtual synchronous generator. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 5124–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, B.; Xu, Z. Virtual synchronous control strategy and inertia analysis of large-scale energy storage. J. Electr. Power Sci. Technol. 2024, 39, 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Yu, P.; Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Shu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Blaabjerg, F. Phase feedforward damping control method for virtual synchronous generators. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 9790–9806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wen, B.; Wang, H. A self–adaptive damping control strategy of virtual synchronous generator to improve frequency stability. Processes 2020, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Li, T.; Shi, K.; Xu, P.; Sun, Y. Coordinated control strategy of virtual synchronous generator based on adaptive moment of inertia and virtual impedance. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2021, 11, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Long, Y.; Zeng, J.H.; Tu, C.M.; Xiao, F.; Guo, Q. Transient power oscillation suppression strategy of virtual synchronous generator considering overshoot. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, A.; Khayat, Y.; Naderi, M.; Dragicevic, T.; Mirzaei, R.; Blaabjerg, F.; Bevrani, H. Inertia response improvement in AC microgrids: A fuzzy–based virtual synchronous generator control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 35, 4321–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wai, R.-J. Adaptive fuzzy–neural–network power decoupling strategy for virtual synchronous generator in micro–grid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 37, 3878–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Mao, L.; Qu, K. RBF neural network based virtual synchronous generator control with improved frequency stability. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 4014–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.H.; Yao, F.J.; Hao, P.F.; Lu, H. Adaptive inertia control for VSG based on improved RBF neural network. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 2021, 58, 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Zhao, J.; Mao, L.; Qu, K.; Gao, Z. An improved virtual synchronous generator power control strategy considering time–varying characteristics of SOC. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 144, 108454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Wang, X. Optimization of frequency dynamic characteristics in microgrids: An improved MPC–VSG control. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 156, 109783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B.; Liao, Y.; Chong, K.T.; Rodriguez, J.; Guerrero, J.M. MPC–Controlled Virtual Synchronous Generator to Enhance Frequency and Voltage Dynamic Performance in Islanded Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 12, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, C.; Valastro, S.; Calogero, G.; Smecca, E.; Mannino, G.; Arena, V.; Balestrini, R.; Sillo, F.; Ciná, L.; La Magna, A.; et al. Improved radicchio seedling growth under CsPbI3 perovskite rooftop in a laboratory-scale greenhouse for Agrivoltaics application. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.K.; Nørremark, M.; Green, O. Sensor and control for consistent seed drill coulter depth. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 127, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).