Abstract

This work introduces a tunable technique to push the low-frequency corner () of capacitively coupled instrumentation amplifiers (CCIAs) to the sub-mHz range for emerging biosensing applications. The proposed approach combines Complementary Transimpedance Boosting (CTB) to limit the DC feedback current and segmented duty-cycled resistors (SDR) for tunable resistance. The CTB-SDR technique achieves a stable effective post-layout pseudo-resistance of , equivalent to while occupying in a 180 nm process. According to JESD91 standards, it shows a standard deviation of under post-layout Monte Carlo + process analysis, spread under voltage variations and under temperature variations and . In addition, duty-cycling calibration can compensate for worst-case process corner variations and mismatch-induced feedback instability.

1. Introduction

In the biomedical field, applications that monitor vital signs have experienced significant growth in recent years. These advances aim to understand the physiological phenomena of the human body and their impact on daily life [1,2]. Consequently, the research and development of devices capable of detecting a wide range of biopotential signals has become essential to assess patient health [3,4].

Most electrophysiological interfaces are designed to operate in a typical frequency range of to several kilohertz [5,6,7]. However, relevant biological signals are present at low frequencies in the range of hundreds of millihertz (mHz), which are often ignored by such systems. This limitation restricts the ability to detect essential biopotentials, providing better disease prevention, detection, and treatment.

Recent studies show that there are components of clinical interest in the tens of mHz range, which are usually attenuated by conventional techniques. These signals are known as DC-biosignals. They can complement the diagnosis and prevention of multiple diseases and conditions. The recording of DC-biosignals focuses on preserving the very low-frequency components of biopotentials, which are often attenuated by the bandwidth of conventional front ends. For this reason, it is necessary to have acquisition systems with wider bandwidths that include very low frequencies, while maintaining low noise levels and power consumption.

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a fundamental technique for monitoring brain activity and detecting bioelectric changes associated with cognitive processes. DC-EEG enables the readout of ultra-low-frequency components below [8]. These signals reflect slow fluctuations in ionic currents and voltage oscillations, providing critical information to understand neuronal activity. The results of this information help diagnose and monitor conditions such as epilepsy [9].

Electrogastrography (EGG) is a non-invasive technique that detects electrical signals generated by the coordinated contractions of the stomach muscles, which helps identify gastric disorders [10,11]. It can also detect gastric arrhythmias, consisting of fast-frequency waves (tachygastrias) and slow-frequency waves (bradygastrias). In the presence of abnormal gastric bioelectric potentials, the frequency range of the EGG can range from to [5,12].

Capacitively coupled instrumentation amplifiers (CCIA) are widely used in biomedical applications in integrated circuits due to their well-defined gain, high DC rejection, and simple design [13]. CCIAs’ amplifiers use only one operational transconductance amplifier (OTA), and their gain depends on the ratio of the capacitors. That makes them advantageous because the capacitive mismatch is minimal compared to the resistive mismatch generated by process variations [2].

In CCIA amplifiers, the low-frequency corner is determined by the constant of the feedback network. In conventional biomedical applications, a low-frequency corner in the order of hundreds of mHz is required. To achieve this, high-value capacitors and resistors are needed, which is challenging due to area restrictions in technological processes. For DC-biosignal applications, the low-frequency corner requires a lower value than in conventional techniques, which increases complexity. A practical alternative is to increase , since increasing usually consumes a significant amount of die area for a few pF. However, polysilicon resistors also consume a significant amount of die area, even to achieve a few megaohms (M). Therefore, the development of techniques that provide equivalent resistances on the order of tens or hundreds of teraohms (T) is essential to ensure adequate bandwidth for detecting very low-frequency signals.

Several recent works employ CCIAs to develop low-power, portable systems for biosignal acquisition in very low-frequency ranges, achieving a low-frequency corner () below 100 mHz while maintaining high gain. In [14], a DC-Servo Loop (DSL) achieves . However, the feedback transconductance design can be complex and is affected by process, voltage, and temperature (PVT) variations. Similarly, in [15], an is achieved using a fully symmetric ring pseudo-resistor structure, reaching an equivalent pseudo-resistance on the order of gigaohms (G). However, this technique remains sensitive to variations in PVT. In [16], the Bootstrapped-PR technique is used to achieve an , however, chopping must be implemented to achieve good input-referred noise (IRN) performance, and the equivalent effective pseudo-resistance is not high enough. In [5], a non-continuous sampling mode called sample-level duty-cycling (SLDC) is used in a direct digitization ADC, capable of detecting signals down to through short sampling periods followed by oversampling and digital processing. However, this requires additional complex control logic, and information from fast or transient events can be lost since the circuit is mostly inactive. Finally, in [17], an is obtained by implementing a switched-capacitor-resistor-pseudo-resistor, which is a hybrid feedback resistor using switch-capacitor resistor (SCR) and pseudo-resistor (PR) techniques. This approach is robust to PVT variations. However, it requires precise control of multiple switching frequencies, and the resulting equivalent effective pseudo-resistance is insufficient for emerging biosignal applications.

The commonly used pseudo-resistors in CCIA feedback structures offer high resistance, a small size, and a low noise contribution [13,18]. However, they are susceptible to PVT and voltage non-linearities, resulting in variable bandwidth [19]. To solve this problem, techniques that are robust to these variations have been developed, such as the segmented duty-cycle resistor (SDR) [20]. This technique is based on single-rate-switched resistors, which are robust to PVT variations, and utilizes complementary linear switches to achieve resistances in the range. The use of SDR enables high resistance with a switching frequency that is outside the bandwidth of the signal of interest. Other techniques, such as switched capacitor resistors or duty-cycle resistors, require a switching frequency within or below the bandwidth of the signal of interest to achieve high equivalent resistance [20]. Another technique that has been proposed to achieve high feedback resistance in CCIAs is the Complementary Transimpedance Boosting (CTB) [21]. By combining positive and negative feedback, this technique can increase the effective feedback resistance to hundreds of . However, positive feedback can induce instability under mismatch variations [22].

The goal of the proposed work is to demonstrate a technique that pushes the low-frequency corner of CCIAs to the sub-mHz domain. This is achieved by the joint implementation of CTB and SDR techniques. We chose a standard folded-cascode OTA as a test amplifier to ensure objectivity and provide generality. The folded-cascode OTA has been implemented in real-world biomedical instrumentation applications [23]. Additionally, we used the recently proposed SDR in order to provide tunability in case of instability, which is inherent in the CTB technique [22].

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the principles of CCIA and amplifier design. Section 3 presents the performance of the Complementary Transimpedance Boosting implementation using the cascaded pseudo-resistor technique. Section 4 details the implementation of Complementary Transimpedance Boosting using the Segmented Duty-Cycled Resistor technique, Section 5 presents the results, and the conclusions are given in Section 6.

2. Capacitively Coupled Instrumentation Amplifiers

2.1. Basics of Capacitively Coupled Instrumentation Amplifiers

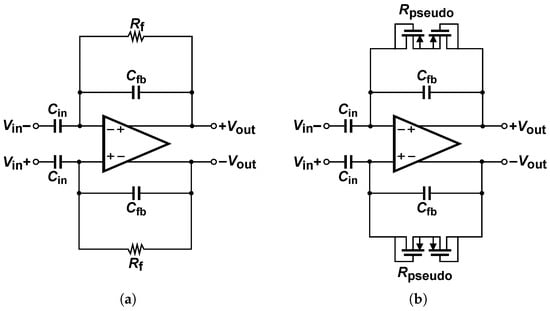

CCIAs are widely used to amplify biopotentials. Those low-amplitude and frequency signals pose various challenges when designing low-power, low-noise, and stable amplifiers [24]. CCIAs consist of a single-stage differential amplifier operating in a closed loop. The operating principle is based on an input capacitor (), a feedback capacitor (), and a feedback resistor (), as shown in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

(a) Conventional topology of CCIA. (b) Typical closed-loop using Pseudo-Resistor in CCIA.

A high value of the input capacitor results in lower input impedance, which can cause significant signal attenuation and distortion. Despite this drawback, the CCIAs topology continues to be used due to the manufacturing precision achieved in the technological process [13]. However, this results in considerable area consumption, as the closed-loop gain is determined by the ratio of the input capacitor to the feedback capacitor, as shown in Equation (1).

The value of the low-frequency corner depends on the product of the feedback elements and is determined by the expression shown in Equation (2).

Feedback resistance requires a high value to ensure sufficient bandwidth to detect low-frequency signals. In biomedical applications, the low-frequency corner is typically below , depending on the type of signal being detected.

The typical configuration of a CCIA using pseudo-resistors is shown in Figure 1b, where the low-frequency corner is typically on the order of hundreds of mHz, which is ideal for conventional clinical applications [2]. However, it may not be optimal for the detection of ultra-low-frequency biological signals.

2.2. Test Amplifier Design

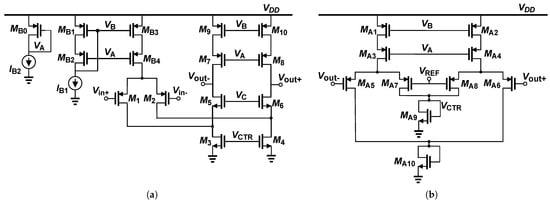

For simulation-based tests, a CCIA using a fully differential folded-cascode OTA topology was designed for this work, as shown in Figure 2a. The output voltage is set at by the differential-difference common-mode feedback (CMFB) stage shown in Figure 2b. Simulation results confirm the CMFB loop is stable and does not introduce oscillation or ringing.

Figure 2.

(a) Fully differential folded-cascode OTA topology. (b) Common-Mode Feedback topology.

Table 1 shows the dimensions and currents of each transistor in the amplifier implementation in a technological process of 180 nm. The first section of the table presents the dimensions for the main amplifier, followed by the current mirror and the CMFB circuit. All transistors are sized to operate in the weak inversion region () to minimize noise contribution and reduce power consumption.

Table 1.

Transistor dimensions for folded-cascode OTA and CMFB stages from Figure 2.

The current consumption of the main amplifier was measured as , while the total current consumption was , with a supply voltage of 1.8 V.

The additional parameters of the design related to the operating point are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Design and device parameters for 180 nm technology.

3. Complementary Transimpedance Boosting Based on Cascaded Pseudo-Resistor Feedback Network

3.1. Concept of Complementary Transimpedance Boosting

Using conventional DC resistive feedback techniques, it is possible to achieve high resistance values. However, these values are not high enough for applications that require detecting signals at extremely low frequencies to meet the required specifications. Other techniques have been proposed, such as cascaded pseudo-resistor (CPR) or employing a T-resistor feedback (TFB) topology. However, even these alternatives fail to generate a sufficiently high DC resistance to meet the requirements of these applications [21].

The complementary transimpedance boosting (CTB) technique forces partial cancellation of a portion of the feedback current before it reaches the virtual input node. To achieve this, the positive and negative feedback currents are forced to partially cancel each other at an intermediate node along the feedback path of the amplifier [21].

As shown in Figure 3, resistor forms the positive feedback branch, while corresponds to the negative feedback branch. Both are connected to the same virtual node where partial current cancellation occurs. Furthermore, the resistor isolates the amplifier input node from the mixing node, contributing to a low increase in input-referred noise.

Figure 3.

Complementary Transimpedance Boosting (CTB) applied to resistor.

The equivalent resistance obtained by this technique is described in Equation (3), where it can be seen that the increase in the feedback resistance is higher when the values of and are close.

The denominator of Equation (3) determines the stability of the system when using the CTB technique. Three cases are presented depending on the relationship between the resistances and .

Case 1: > , the positive feedback branch predominates over the negative one, resulting in an equivalent positive resistance. In this case, the system is stable.

Case 2: < , negative feedback predominates over positive feedback, generating equivalent negative resistance. This condition causes instability in the system.

Case 3: = , both feedback branches are equal, ideally generating an infinite equivalent resistance. However, this case is not achievable in practice due to technological process mismatches.

The CTB technique introduced in [21] does not report CMFB interference in the stability of the feedback loop. Stability depends on the values of resistors and , enabling a reliable evaluation of the techniques proposed in the amplifier.

3.2. Implementation of Complementary Transimpedance Boosting

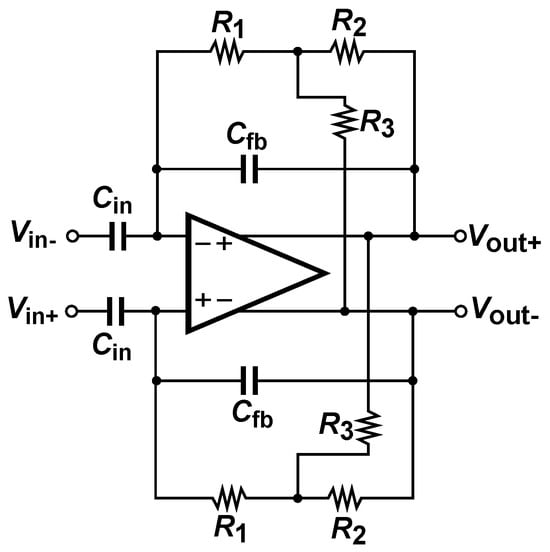

The topology presented in [21] employs the CTB-DC approach to compensate for the application of CTB-AC, without focusing primarily on increasing the equivalent feedback resistance. To realize this compensation, resistors , , and were implemented using conventional pseudo-resistors, as shown in Figure 4a. However, these pseudo-resistors exhibit high sensitivity to process, voltage, and temperature (PVT) variations. To improve these limitations, the CPR technique shown in Figure 4b was applied. This technique increases the equivalent resistance of , , and , achieving a high effective pseudo-resistance that enables reaching a low-frequency corner in the sub-mHz range.

Figure 4.

(a) Complementary Transimpedance Boosting (CTB) applied to pseudo-resistor. (b) Complementary Transimpedance Boosting (CTB) applied to a cascaded pseudo-resistor.

In this proposal, the sizing of the pseudo-resistors is crucial for achieving an adequate low-frequency corner in DC-biosignal acquisition, while maintaining feedback-loop stability with the CTB technique. To ensure stability in the feedback loop and obtain a useful equivalent resistance for DC-biosignal acquisition, we adopt the condition , as shown in Equation (3). This condition maintains the equivalent resistance at a positive value. However, as and approach each other, the equivalent resistance increases. If they become too close, the condition may be violated, leading to instability in the feedback loop.

This evidences the trade-off between stability and maximum equivalent resistance. To balance these two requirements, is implemented with a transistor size of . is sized in the same way as to maintain a greater contribution to the equivalent resistance, because does not participate in the condition of instability. For , the channel width is fixed to match that of and . The equivalent resistance of is adjusted by varying the channel length. This allows better control over the equivalent resistance. It also ensures that the size differences between the pseudo-resistors are sufficient to prevent mismatch-induced instability. The sizing of resistor must be determined in order to achieve the desired , considering maintaining PVT robustness. Based on these considerations, was implemented using four pseudo-resistors in cascade, whereas and were implemented with three pseudo-resistors in cascade. This configuration increases the equivalent resistance enough to enable the detection of DC-biosignals without compromising feedback-loop stability.

This implementation is suitable when high precision of the low-frequency corner is not required, and the area is constrained. In such cases, pseudo-resistors can achieve very high resistances on the order of hundreds of G and even some T with minimal area. Therefore, using the CTB–CPR technique, it is possible to achieve high equivalent resistances while maintaining a low-area implementation. Furthermore, implementation using pseudo-resistors does not increase the power consumption of the circuit, as it does not require additional tuning circuitry. However, this simplicity is directly dependent on sizing, with no ability to adjust for mismatch and PVT variations.

4. Complementary Transimpedance Boosting Based on Segmented Duty-Cycled Resistor Feedback Network

4.1. Concept of Segmented Duty-Cycled Resistor

The leakage currents in the pseudo-resistors make the resistance obtained highly sensitive to the variations in process, voltage, and temperature [25,26,27]. In addition, they present a non-linear response to voltage, which reduces accuracy and affects system stability [28,29,30].

Other techniques robust to PVT variations, such as switched-capacitor resistors (SCR) or duty-cycled resistors (DCR), can generate high and stable resistances. However, a disadvantage of these techniques is that they require a switching frequency within or below the range of the signal of interest, which can deteriorate the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and introduce artifacts in the acquired signal [20].

The segmented duty-cycled resistor technique (SDR) allows resistances of the order of without switching artifacts in the band of interest and remains robust to PVT variations. It uses a segmented switched resistor that distributes the parasitic capacitance present in the resistor. This causes the capacitance to discharge toward the average voltage between the switching nodes.

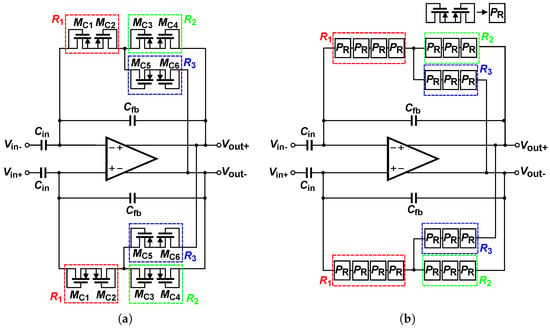

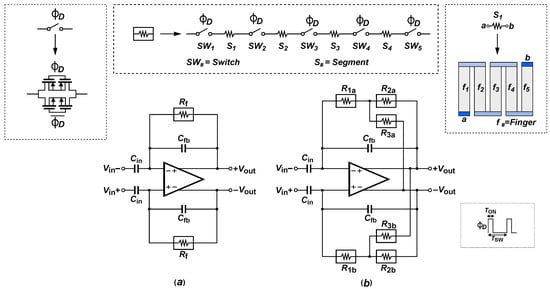

Figure 5a shows the implementation of the SDR technique in a CCIA amplifier, where the gain is defined by the capacitors and . The low-frequency corner is set by the RC ratio implemented in the feedback network. In this network, the resistance consists of four polysilicon segments, each composed of multiple fingers connected in series. These segments are interspersed with complementary switches with dimensions of , utilizing a pseudo-resistor configuration that helps reduce current leakage.

Figure 5.

(a) Conventional closed-loop gain amplifier with Segmented Duty-Cycled Resistor (SDR). (b) Complementary Transimpedance Boosting (CTB) applied to Segmented Duty-Cycled Resistor (SDR).

Equation (4) shows the effective transconductance, which depends on the duty-cycle (), the number of segments (N), the value of each polysilicon resistance segment (), the total parasitic capacitance of the polysilicon resistors (), and the on/off resistances of the complementary switches ( and ). In the SDR technique, the on resistance is given by , and the off resistance is given by .

Equation (5) shows the effective low-frequency corner, which depends on effective transconductance and the feedback capacitor.

The SDR technique offers advantages such as high equivalent resistance and robustness to process, voltage, and temperature (PVT) variations. However, detecting DC-signals requires hundreds of of feedback resistance.

4.2. Implementation of CTB–CPR Technique

For the reasons mentioned above, this work proposes combining the CTB technique with the SDR technique, enabling an effective pseudo-resistance on the order of hundreds of . This combination shifts the low-frequency corner into the sub-mHz range while maintaining high robustness against process, voltage, and temperature variations. Moreover, the duty-cycled implementation provides tunability, allowing the bandwidth to be adjusted to specific application requirements and thereby offering greater system flexibility.

The CTB-SDR technique focuses on maximizing equivalent resistance while maintaining the switching frequency above the band of interest, minimizing the presence of artifacts, and maintaining the integrity of DC-biosignals. Using a switching frequency and a , a high equivalent resistance can be obtained that achieves a low-frequency corner in the sub-mHz range.

The amplifier used in the CCIA is designed to maintain low power consumption. However, in architectures that use duty-cycling, there is additional overhead associated with the duty-cycle generator circuit. Therefore, in systems for portable and continuous monitoring applications, it is essential that the duty-cycle generator be designed to maintain low power consumption. In addition, topologies that improve performance should be employed, such as the use of complementary switches in a pseudo-resistor configuration to reduce leakage currents, as implemented in [20]. On the other hand, duty-cycling enables very high equivalent resistances through charge transfer, but it also introduces switching noise that can increase distortion. Therefore, careful layout and noise-mitigation techniques are required to minimize its impact.

For the implementation of the SDR technique presented in [20], the resistive segments are constructed by connecting multiple identical fingers, which allows the multiplicity of each resistive segment to be controlled while maintaining a compact design. The CTB–SDR technique shown in Figure 5b incorporates a positive feedback loop whose stability requires that the condition be satisfied, as shown in Equation (3). To facilitate fine-tuning through design, a value of per finger was used, similar to that described in [20], so that the equivalent value of each segment can be scaled linearly by adding or removing fingers. Based on the above, was implemented with four segments of 13 fingers each. The same configuration was used for to maximize its contribution to the equivalent resistance, since it does not affect the stability condition imposed by the CTB technique. To satisfy , the resistance was designed with the same number of segments as but with 9 fingers per segment, thus reducing its value relative to . This means that is 30.8% lower than .

Finally, simulations confirmed that this choice places the low-frequency corner in the sub-mHz range required for DC-biosignals acquisition, maintaining loop stability against PVT variations and mismatch.

5. Results

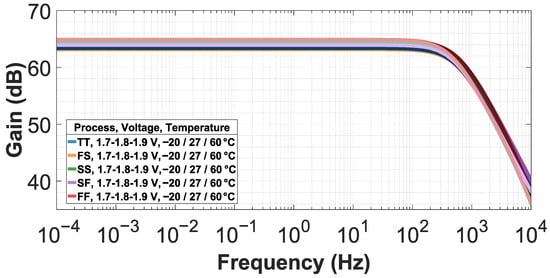

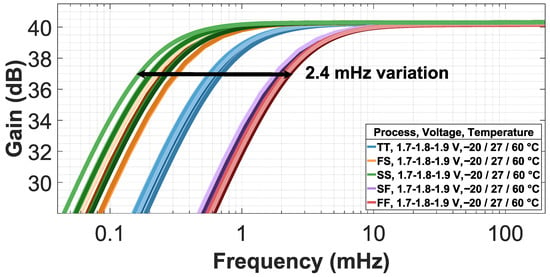

The open-loop gain obtained for the test folded-cascode OTA is approximately , with a variation of across PVT. Figure 6 shows the open-loop frequency-gain results of the test folded-cascode OTA. The PVT verification was performed considering the following process (TT, SS, FF, SF, FS), voltage (), and temperature (−20 °C, 27 °C, 60 °C) variations. The temperature variation is in agreement with the standards of biomedical integrated circuits [20].

Figure 6.

Open-loop gain frequency response of test folded-cascode OTA against different PVT corners.

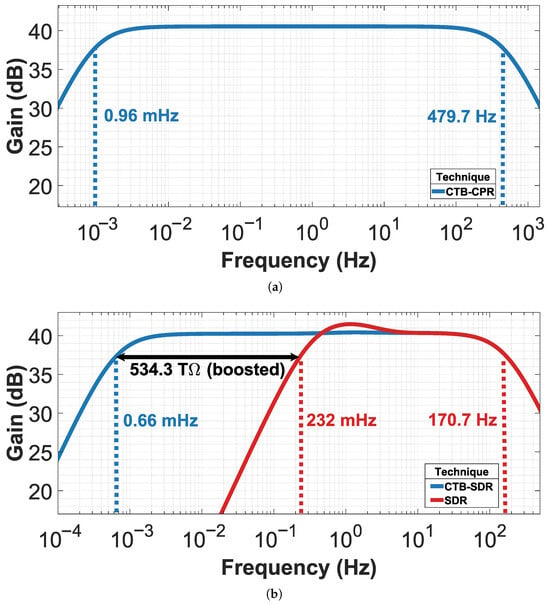

The frequency response of the CCIA with CTB-CPR technique is shown in Figure 7a. With an size of we achieve an equivalent effective pseudo-resistance of 368.4 . This enables a low-frequency corner of 960 and a high-frequency corner of 479.7 Hz, providing an ideal bandwidth for detecting a wide range of DC-biosignals.

Figure 7.

Frequency response of CCIA with (a) CTB-CPR and (b) comparative of CTB-SDR and SDR techniques.

Figure 7b shows the post-layout frequency response of the SDR and CTB-SDR techniques implemented in the CCIA. The conventional SDR technique achieves an equivalent effective pseudo-resistance of 1.5 , resulting in a low-frequency corner of 232 mHz, which is suitable for conventional biomedical applications. However, this equivalent effective pseudo-resistance is not enough for applications that require the detection of very low frequencies. Combining the CTB technique with the SDR technique, an increase of 543.3 is achieved, reaching an equivalent effective pseudo-resistance of 535.8 , which allows for a low-frequency corner of 660 while maintaining a high-frequency corner of 170.7 Hz. This provides an optimal bandwidth for detecting very low-frequency biosignals.

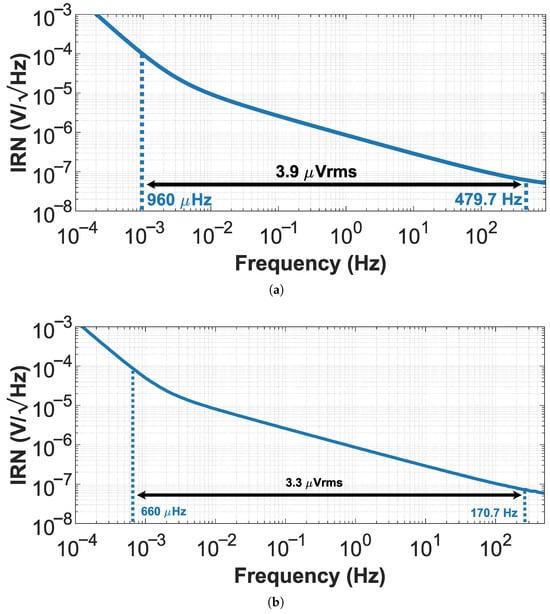

Table 3 shows the noise contributions and noise-related parameters obtained from the implementation of the CTB-CPR and CTB-SDR techniques. Both configurations achieve low noise contributions.

Table 3.

Noise-related parameters and noise contributions.

For the test folded-cascode OTA, the noise contribution of each transistor can be seen as the sum of the thermal noise contribution and flicker noise, as shown in Equation (6). Where k is the Boltzmann constant, is the white-noise factor, and is a process-dependent constant.

The noise contribution to the output of transistors and , in the following associated as () = (), i.e., , , and , is given by Equation (7).

Dividing by of the amplifier, using the value shown in Equation (8).

The input-referred noise is obtained, which is shown in Equation (9).

where the main noise contribution comes from transistors , because by design , where the current of is greater than that of and . The noise of the cascode and is negligible at low frequencies because the gain of the noise voltage source at the output is much lower than the gain of the amplifier [31].

The total input-referred noise considering the entire bandwidth (Hz–479.7 Hz) is as shown in Figure 8a, and for the CTB-SDR technique, the total noise referred to the input considering the entire bandwidth (–) is as shown in Figure 8b.

Figure 8.

Input-referred noise of CCIA with (a) CTB-CPR and (b) CTB-SDR.

PVT verification evaluates amplifier performance using CTB-CPR and CTB-SDR feedback techniques under process variations (TT, SS, FF, SF, FS), voltage (), and temperature conditions (−20 °C, 27 °C, 60 °C).

Using the CTB–CPR technique, a very high equivalent effective pseudo-resistance was achieved, enabling a low-frequency corner in the sub-mHz range, which is ideal for detecting very low-frequency biosignals. However, using pseudo-resistors generates variations in equivalent resistances , , and , which affect the equivalent effective pseudo-resistance obtained using the CTB technique. This occurs because the CPR implementation exhibits low robustness against PVT variations. As a consequence, the likelihood of instability increases, or the equivalent resistance is reduced, resulting in a low-frequency corner that is insufficient to meet the bandwidth requirements for DC-biosignal detection. In the proposed design, the low-frequency corner obtained with the CTB–CPR technique ranged from 17.8 mHz to 0.34 mHz.

The CTB–SDR technique provides greater robustness than CTB–CPR while maintaining a low-frequency corner in the sub-mHz range. This improvement is due to the robustness of the SDR technique against PVT variations. The nominal condition is TT corner, with and °C. The variation in the low-frequency corner for supply voltage is 20.7 for . Temperature variation is 168 for °C to 60 °C. Finally, process variation is 2.13 mHz for TT, SS, FF, SF, and FS corners. The total variation is 2.4 mHz, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

CCIA with CTB-SDR technique under process, voltage, and temperature variations.

Table 4 compares the low-frequency corner and gain parameters obtained with the CTB–CPR and CTB–SDR techniques. In both cases, the gain shows minimal variation. However, the low-frequency corner variation is significantly reduced, from a maximum of 17.8 mHz with the CTB–CPR technique to 2.4 mHz with the CTB–SDR technique, demonstrating improved performance and high robustness against PVT variations.

Table 4.

Parameters obtained from the PVT analysis.

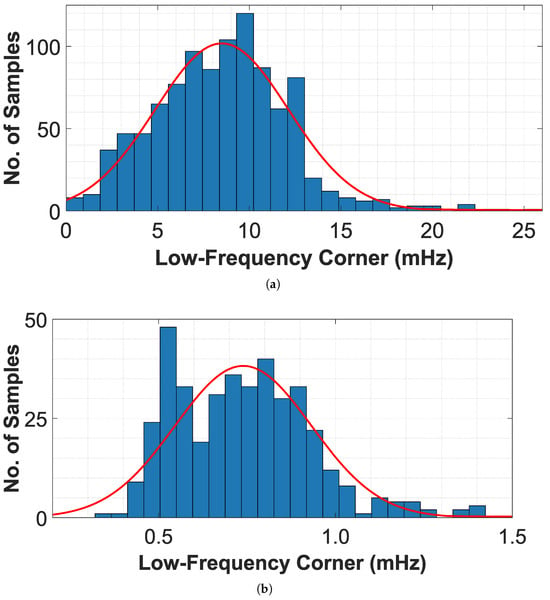

The Monte Carlo analysis was performed under nominal conditions with and a temperature of for a run of 400 samples, to evaluate the performance of the CTB-SDR technique under mismatch variations. Table 5 shows the parameters obtained.

Table 5.

Parameters obtained from the Monte Carlo analysis.

Using the CTB-CPR technique, the low-frequency corner showed an average value of 7.79 mHz with a standard deviation of 4.68 mHz according to JESD91 standards [32], where 99% of the cases remain below 16 mHz. However, this value is not sufficiently low to ensure the detection of a wide range of DC-biosignals. On the other hand with the CTB-SDR technique, the low-frequency corner achieved an average value of 0.73 mHz with a standard deviation of 0.19 mHz, and 99% of the cases remain below 1.3 mHz. This allows for greater bandwidth, which is ideal for detecting DC-biosignals.

Figure 10a,b show the histograms of the low-frequency corner using the CTB–CPR and CTB–SDR techniques, respectively. The average value decreased from 7.79 to 0.73 mHz, representing a 90.6% reduction, which demonstrates the improved robustness and precision of the CTB–SDR technique. Using the CTB–CPR technique, an average gain of 36.24 dB with a standard deviation of 3.7 dB was obtained, with 99% of cases maintaining a gain above 26 dB. With the CTB–SDR technique, the average gain increased to 40.12 dB with a standard deviation of 3.2 dB, and 99% of cases maintained a gain above 34 dB, demonstrating improved performance under mismatch.

Figure 10.

Histogram of the low-frequency corner from Monte Carlo analysis of CCIA with (a) CTB-CPR technique and (b) CTB-SDR technique.

Monte Carlo analysis revealed variations in gain with both methods that deviate significantly from the design specifications. This can be attributed to the inherent instabilities of the CTB technique caused by mismatch, which affects the system response. Compared to CPR, the SDR technique is more robust against PVT and allows tuning of the equivalent effective pseudo-resistance through duty-cycling. This enables the low-frequency corner to be adjusted and compensates for variations caused by mismatch, thereby restoring stability to the design.

In the CTB–SDR technique, the resistive segments implemented with polysilicon have relatively large dimensions, making them less susceptible to mismatch variations. On the other hand, the elements that have the greatest impact on this technique are the complementary switches. Mismatch variations can modify their resistances, and . As a result, the equivalent resistances of , , and change, which can compromise stability when and become too close in value. This issue can be mitigated by adjusting the duty-cycle, as the equivalent values of , , and depend on the duty-cycle, as shown in Equation (4). By tuning the duty-cycle, the ratio between and can be adjusted so that the stability condition described in Equation (3) is satisfied. This tuning helps compensate for voltage and temperature variations, as well as mitigate mismatch variations introduced by the manufacturing process.

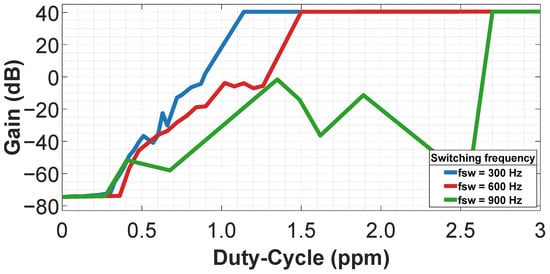

To demonstrate this, we force an unstable situation in the amplifier using the CTB–SDR technique, as shown in Figure 5a. The instability is introduced by varying the sizing of the complementary switches in the resistor branches. Each resistor branch is implemented with five complementary switches, whose widths are summarized in Table 6. These asymmetric width assignments intentionally break the symmetry of the CTB–SDR network and increase its sensitivity to mismatch. The idea is to restore the circuit to a stable state via duty-cycling tuning. Figure 11 illustrates this for three switching frequencies of 300 Hz, 600 Hz and 900 Hz. The operating point is recovered by tuning the duty cycle. This procedure provides enhanced control and represents a significant advantage over the inherent limitations of the CTB technique.

Table 6.

Switch widths used in the unstable CTB-SDR case.

Figure 11.

Duty-cycle (ppm) as a function of gain, showing tuning to restore the operating point.

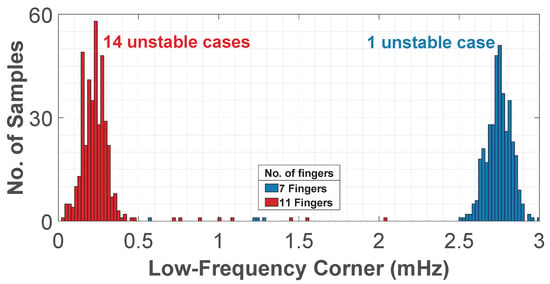

Finally, Figure 12 presents a Monte Carlo analysis with 400 samples of the low-frequency corner. Two values are compared for the segmentation of resistor , while resistor is kept constant with 13 fingers. In the more stable case, 7 fingers are used in the segments, resulting in a larger resistance difference between and . In the less stable case, 11 fingers are used in the segments, which reduces this resistance difference to only two fingers. For 7 fingers, the low-frequency corner remained above 1 mHz. For 11 fingers, it shifted below 1 mHz, but with more unstable cases. This confirms the trade-off of the CTB–SDR technique, where higher equivalent resistances increase sensitivity to mismatch and the risk of instability. Therefore, it is crucial to choose appropriate values for and to minimize instabilities caused by mismatch, and to use duty-cycle tuning to compensate for the remaining instabilities.

Figure 12.

Monte Carlo analysis of the low-frequency corner using the CTB-SDR technique, with of 4 segments with 7 fingers and 11 fingers.

Table 7 shows the performance comparison of the proposed design in relation to the parameters reported in the state-of-the-art of the amplifiers used to acquire DC-biosignals. A higher bandwidth is observed as a result of the increased equivalent resistance by implementing the CTB technique. Moreover, the design provides tunability, allowing the bandwidth to be adjusted for better accuracy and adaptability to specific application requirements, which is ideal for detecting DC-biosignals and portable systems.

Table 7.

Parameter Comparison.

6. Conclusions

This work introduces the integration of two techniques to achieve equivalent feedback resistances in the order of hundreds of in a CCIA, enabling a low-frequency corner in the microhertz range for DC-biosignal detection.

The CTB technique provides high equivalent resistance with minimal area overhead and can be implemented using multiple techniques. Using cascaded pseudo-resistors, resistances of up to 368.4 were achieved, corresponding to = 960 Hz. However, this approach is vulnerable to process, voltage, and temperature (PVT) variations.

The Segmented Duty-Cycled Resistor technique was implemented to overcome this limitation, enabling tunable pseudo-resistances robust to PVT variations. In combination, the CTB-SDR approach achieved a resistance of 535.8 with = 660 Hz, maintaining tunability and PVT robustness, while ensuring low noise, and reducing the instability associated with the CTB technique.

Finally, adjusting the low-pass corner using duty-cycling enables the bandwidth to be adapted to various bio-applications, such as EEG and DC-EEG, while tuning compensates for instabilities generated by mismatches, ensuring reliable performance in acquisition systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.-R., J.L.V. and A.D.-S.; Methodology, J.L.V. and A.D.-S.; Software, M.B.-R. and J.L.V.; Validation, M.B.-R. and J.L.V.; Formal analysis, M.B.-R., J.L.V. and A.D.-S.; Investigation, M.B.-R., J.L.V. and A.D.-S.; Resources, J.L.V.; Writing—original draft, M.B.-R., J.L.V. and A.D.-S.; Writing—review & editing, E.T.-C.; Supervision, J.L.V., E.T.-C. and A.D.-S.; Project administration, J.L.V. All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank SECIHTI for the scholarship CVU: 1287569.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCIA | Capacitively Coupled Instrumentation Amplifiers |

| CTB | Complementary Transimpedance Boosting |

| CPR | Cascaded Pseudo-Resistor |

| SDR | Segmented Duty-Cycled Resistor |

| High-Frequency Corner | |

| Low-Frequency Corner |

References

- Fang, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, S.; Zeng, X.; Hong, Z.; Xu, J. A 107.6 dB-DR Three-Step Incremental ADC for Motion-Tolerate Biopotential Signals Recording. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2024, 18, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjay, R.; Senthil Rajan, V.; Venkataramani, B. A low-power low-noise and high swing biopotential amplifier in 0.18 μm CMOS. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 2018, 96, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yazicioglu, R.F.; Grundlehner, B.; Harpe, P.; Makinwa, K.A.A.; Van Hoof, C. A 160 μW 8-Channel Active Electrode System for EEG Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2011, 5, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Mitra, S.; Van Hoof, C.; Yazicioglu, R.F.; Makinwa, K.A.A. Active Electrodes for Wearable EEG Acquisition: Review and Electronics Design Methodology. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 10, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Akinin, A.; Somayajulu, J.; Lee, M.S.; Paul, A.; Lu, H.; Park, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Mercier, P.P.; Cauwenberghs, G. A Low-Noise Low-Power 0.001Hz–1kHz Neural Recording System-on-Chip With Sample-Level Duty-Cycling. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2024, 18, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.; Jung, Y.; Yun, G.; Youn, D.; Jo, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Ha, S.; Je, M. A PVT-Robust AFE-Embedded Error-Feedback Noise-Shaping SAR ADC With Chopper-Based Passive High-Pass IIR Filtering for Direct Neural Recording. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Choi, Y.; Kim, G.; Baik, S.; Seol, T.; Jang, H.; Lee, D.; Je, M.; Choi, J.W.; George, A.K.; et al. A 0.7 V 17 fJ/Step-FOMW 178.1 dB-FOMSNDR 10 kHz-BW 560 mVPP True-ExG Biopotential Acquisition System with Parasitic-Insensitive 421 MΩ Input Impedance in 0.18 μm CMOS. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–26 February 2022; Volume 65, pp. 336–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastany, Z.J.; Askari, S.; Dumont, G.A.; Kellinghaus, C.; Askari, B.; Gharagozli, K.; Gorji, A. Concurrent recordings of slow DC-potentials and epileptiform discharges: Novel EEG amplifier and signal processing techniques. J. Neurosci. Methods 2023, 393, 109894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins-Ferreira, H.; Nedergaard, M.; Nicholson, C. Perspectives on spreading depression. Brain Res. Rev. 2000, 32, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindasamy, G.; Ramachandran, N.; Porkumaran, K.; Shekar, M. Investigation of digestive system disorders with electrogastrogram using wavelet transform denoising. Int. J. Mach. Intell. 2010, 2, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, J.F.; Tjhia, B.; Wu, V.M.; Shin, A.; Sit, N.L.J.; Pham, T.; Nguyen, A.; Li, C.; Kumar, R.; Aguilar-Rivera, M.; et al. An Adhesive-Integrated Stretchable Silver-Silver Chloride Electrode Array for Unobtrusive Monitoring of Gastric Neuromuscular Activity. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2001229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.L.; Stern, R.M. Handbook of Electrogastrography; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, L.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S. Capacitively Coupled Instrumentation amplifier with optimized feedback pseudo-resistor for wet-gel based electrodes. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 28, 1467–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Law, M.K.; Mak, P.I.; Martins, R.P. A 1.83 μW, 0.78 μVrms input referred noise neural recording front end. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Beijing, China, 19–23 May 2013; pp. 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Yu, Q.; Wu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Ning, N. A programmable analog front-end with independent biasing technique for ECG signal acquisition. Microelectron. J. 2023, 136, 105792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincorena-Arraiza, M.; De La Cruz-Blas, C.A.; Carlosena, A. Low-Power Capacitively Coupled AC Amplifiers with Tunable Ultra Low-Frequency Operation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, L.; Shi, G.; Li, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. A PVT-Insensitive instrumentation amplifier with 17.95 mHz high-pass corner based on a PSSP hybrid feedback resistor. Microelectron. J. 2025, 159, 106640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Ghovanloo, M. A Low-Noise Preamplifier with Adjustable Gain and Bandwidth for Biopotential Recording Applications. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), New Orleans, LA, USA, 27–30 May 2007; pp. 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, R.; Cho, M.; Choo, K.; Jeong, S.; Oh, S.; Lee, J.; Sylvester, D.; Blaauw, D. A Delta Sigma-Modulated Sample and Average Common-Mode Feedback Technique for Capacitively Coupled Amplifiers in a 192-nW Acoustic Analog Front-End. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2022, 57, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livanelioglu, C.; Choi, W.; Kim, D.; Liao, J.; Incandela, R.; Jang, T. A Compact and PVT-Robust Segmented Duty-Cycled Resistor Realizing TΩ Impedances for Neural Recording Interface Circuits. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Lett. 2023, 6, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann Ng, K.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Tang, T.; Yoo, J. A Single-Stage, Capacitively-Coupled Instrumentation Amplifier with Complementary Transimpedance Boosting. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 2989–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtashamnia, M.; Yavari, M. A closed-loop neural recording analog front-end with low noise and automatic gain control amplifiers. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2025, 201, 155976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.Y.; Pinto, S.; Chung, S.; Merolla, P.; Koh, T.W.; Seo, D. A 1024-Channel Simultaneous Recording Neural SoC with Stimulation and Real-Time Spike Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 Symposium on VLSI Circuits, Kyoto, Japan, 13–19 June 2021; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramones, A.J.; Villacorta, P.M.; Juruena, K.M.; Obar, T.E.; Siglos, J.R.; Manzano, J.M.; Sanchez, Z.R.; Leynes, A.; Ralota, M.S.; Hizon, J.R.; et al. A 288nV/ low-noise capacitively-coupled instrumentation amplifier (CCIA) in 22-nm UTBB FD-SOI for signal conditioning of MEMS piezoresistive pressure sensors. In Proceedings of the 2023 20th International SoC Design Conference (ISOCC), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 25–28 October 2023; pp. 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.P. Temperature-insensitive Pseudo-resistor. J. Semicond. Technol. Sci. 2022, 22, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, R.; Li, J.; Lyu, H. A 16-Channel Neural Signal Recording IC Achieving a 4-to-90-Hz Tunable High-Pass Cutoff Frequency based on a PVT-Insensitive Pseudo-Resistance Technique. In Proceedings of the 2024 International VLSI Symposium on Technology, Systems and Applications (VLSI TSA), Hsinchu, Taiwan, 22–25 April 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, D.; Fantner, G.; Behrends, J.; Lips, K.; Ortmanns, M.; Anders, J. A transimpedance amplifier using a widely tunable PVT-independent pseudo-resistor for high-performance current sensing applications. In Proceedings of the ESSCIRC 2017—43rd IEEE European Solid State Circuits Conference, Leuven, Belgium, 11–14 September 2017; pp. 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuShawish, I.Y.I.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Majzoub, S.; Hussain, A.J. Biomedical Amplifiers Design Based on Pseudo-Resistors: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 15225–15238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, S.; Fritschi, D.; Sporer, M.; Ortmanns, M. An Experimental Reliability Study of Pseudo-Resistors in Biomedical Applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Austin, TX, USA, 27 May–1 June 2022; 2022; pp. 1892–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.C.; Lin, T.H. Measurement and parameter characterization of pseudo-resistor based CCIA for biomedical applications. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Bioelectronics and Bioinformatics (IEEE ISBB 2014), Chung Li, Taiwan, 11–14 April 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procedural design scenarios. In Structured Analog CMOS Design; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 117–167. [CrossRef]

- Global Standards for the Microelectronics Industry. Method for Developing Acceleration Models for Electronic Device Failure Mechanisms. 2022. Available online: https://www.jedec.org/standards-documents/docs/jesd-91 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).