1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of robotics and mechatronics has enabled the development of robotic manipulators that accurately replicate the anatomy and functionality of the human hand. This paper presents the design and implementation of a humanoid robotic hand with 12 degrees of freedom (DOF), actuated by 15 high-precision servo motors. The structure includes four fingers, a functional opposable thumb, and a wrist with two DOF, allowing natural and coordinated motion.

To enable interaction with the environment, four force-sensitive resistors (FSRs) are embedded in the fingertips to detect contact with objects. This tactile information is transmitted to a haptic control glove, which also serves as the main input device. The glove is equipped with four flex sensors—one per finger—that capture the user’s hand movements and translate them into proportional robotic motion in real time. Wireless communication between the glove and robotic hand is achieved via the ESP-NOW protocol, ensuring low-latency and reliable data exchange. Central processing and servo control are handled by an Arduino Nano ESP32 microcontroller, which integrates motion data acquisition, signal interpretation, and feedback generation within a single system.

2. Related Works

The main scope of this research was to develop a highly biomimetic robotic hand using low-cost materials. The researchers tried to deploy as many degrees of freedom as possible in the real human hand but kept the cost of development low. The design had to be simple but effective. Additionally, a haptic glove was designed to control the robotic hand via teleoperation. Several studies have already been presented by researchers in the area of robotic hands, teleoperation, and haptics.

Tian et al. [

1] proposed a methodology to model and simulate realistic anthropomorphic robotic hands, emphasizing customization for specific applications. Their work integrates computer graphics techniques with robotics, enabling more lifelike hand simulations. This approach provides valuable insights for designing robotic hands that closely mimic human anatomy.

Wang et al. [

2] presented a highly underactuated robotic hand equipped with integrated force and joint angle sensors. Their design focused on achieving dexterity while minimizing actuation complexity. The inclusion of sensing capabilities allows for more precise grasp control and adaptability in dynamic environments.

Capelle et al. [

3] designed and implemented a haptic measurement glove to improve human–telerobot interaction. Their system captured detailed hand motion while providing tactile responses. This enabled more realistic and precise teleoperation experiences.

Hamad et al. [

4] present an augmented-reality system in which both a vibrotactile ring and a full haptic glove are compared, demonstrating that high-fidelity glove feedback significantly improves user performance in gesture-based interactions. This work highlights the increasing convergence of wearable haptic devices and interactive robotics, particularly in enabling more intuitive control of virtual or physical manipulators. Their results underscore the importance of rich feedback modalities to support fine-grained dexterous tasks.

Mittal et al. [

5] proposed an edge intelligence framework for remote robot control. Their architecture incorporated prediction and offloading to reduce latency and improve reliability. This advancement makes haptic teleoperation more feasible in real-world environments.

Recent studies by J. Colan, A. Davila, and Y. Hasegawa have explored advancements in robot-assisted minimally invasive surgery (RMIS), emphasizing the integration of tactile and force feedback systems to overcome the lack of haptic perception in robotic procedures [

6]. Their work highlights innovative sensor technologies and feedback modalities designed to enhance surgical precision and reduce tissue trauma. These developments demonstrate the growing importance of haptic feedback mechanisms in improving surgeon control, reducing cognitive load, and increasing patient safety—key considerations for future robotic surgical systems.

Li et al. developed an affordable soft robotic glove integrating fifteen inertial measurement units (IMUs) and a motor–tendon actuation system for virtual reality–based hand rehabilitation [

7]. The system enables accurate real-time tracking of finger motion and provides haptic feedback through controlled fingertip forces, enhancing patient engagement during therapy. Utilizing field-oriented control for precise torque regulation, the glove offers a cost-effective, modular, and lightweight solution compared to traditional exoskeleton designs. Their work demonstrates significant potential for combining soft robotics and immersive VR environments to improve hand rehabilitation effectiveness and accessibility.

Giudici et al. proposed a novel bilateral teleoperation framework that integrates tactile sensing and virtual reality (VR) for vision-independent robotic manipulation [

8]. Their system enables precise object interaction in complete visual blindness by relying solely on tactile data for both haptic feedback and real-time 3D object reconstruction, displayed through a VR headset. Using Gaussian Process modeling, the approach provides immersive tactile feedback to the operator while enhancing task accuracy and reducing fatigue. This work demonstrates the feasibility of fully haptic-based telemanipulation, representing a significant step toward autonomous and robust robotic control in visually constrained environments.

Cyriac et al. presented this year a haptic glove-guided robotic arm system enabling teleoperation in hazardous or remote environments [

9]. Their setup integrates wearable haptic gloves with a robotic arm, capturing hand gestures to control robotic motions in real-time. The system delivers tactile feedback to the operator, allowing perception of object interactions and improving task precision. By combining gesture-based control with haptic feedback, their approach enhances operator dexterity and control in complex manipulations. This work highlights the potential of haptic glove–robotic arm systems for immersive, safe, and accurate teleoperation across industrial, medical, and exploration applications.

Finally, G. Xu et al. developed a self-powered electrotactile textile haptic (SPETH) glove that integrates triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) to provide haptic feedback without external power sources [

10]. The glove harvests mechanical energy from hand movements or robotic interactions and delivers electrical stimulation through gas discharge tubes and textile electrodes, enabling tactile perception. The SPETH design leverages flexible, embroidered electrodes for comfort and efficiency, achieving controlled and safe tactile sensations. This approach addresses limitations of conventional haptic devices, including bulkiness, high voltage requirements, and power consumption, and demonstrates potential applications in VR/AR, prosthetics, and robotic teleoperation.

3. Materials and Methods

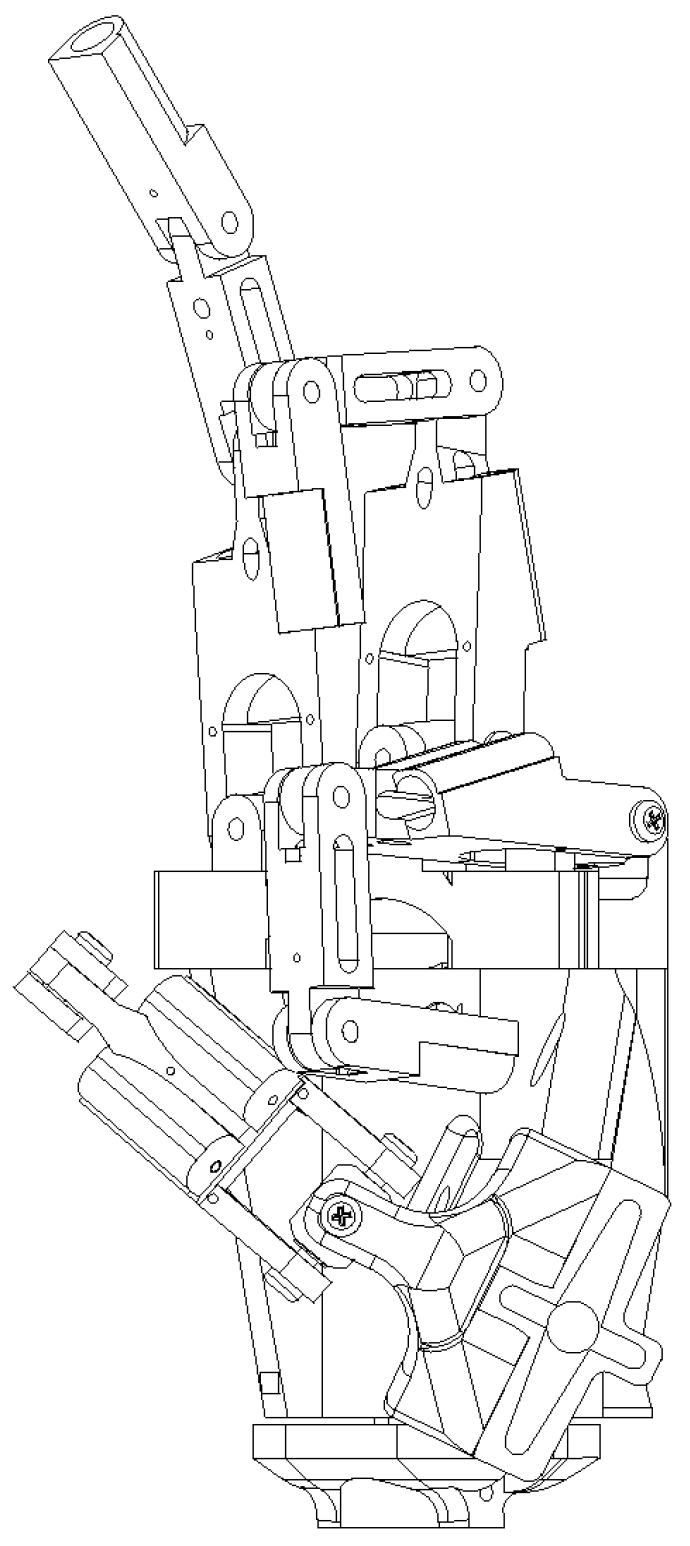

3.1. Design Analysis of the Robotic Arm

The basic design choice was to develop a robotic hand with four fingers in order to achieve a balance between construction, complexity and functionality.

Figure 1 shows a variety of finger postures. The presence of a thumb is crucial, as it is the determining factor that allows the human hand to perform complex movements such as gripping, grasping objects, and precise manipulations [

11]. The presence of a thumb is also very important in robotics, as the opposable thumb is key to a flexible and stable grip [

12]. The anatomy of the robotic hand was based on principles of biomimetic engineering, as this research focused on human hand anatomy. Each finger has joints corresponding to the MCP and IP joints of the human hand.

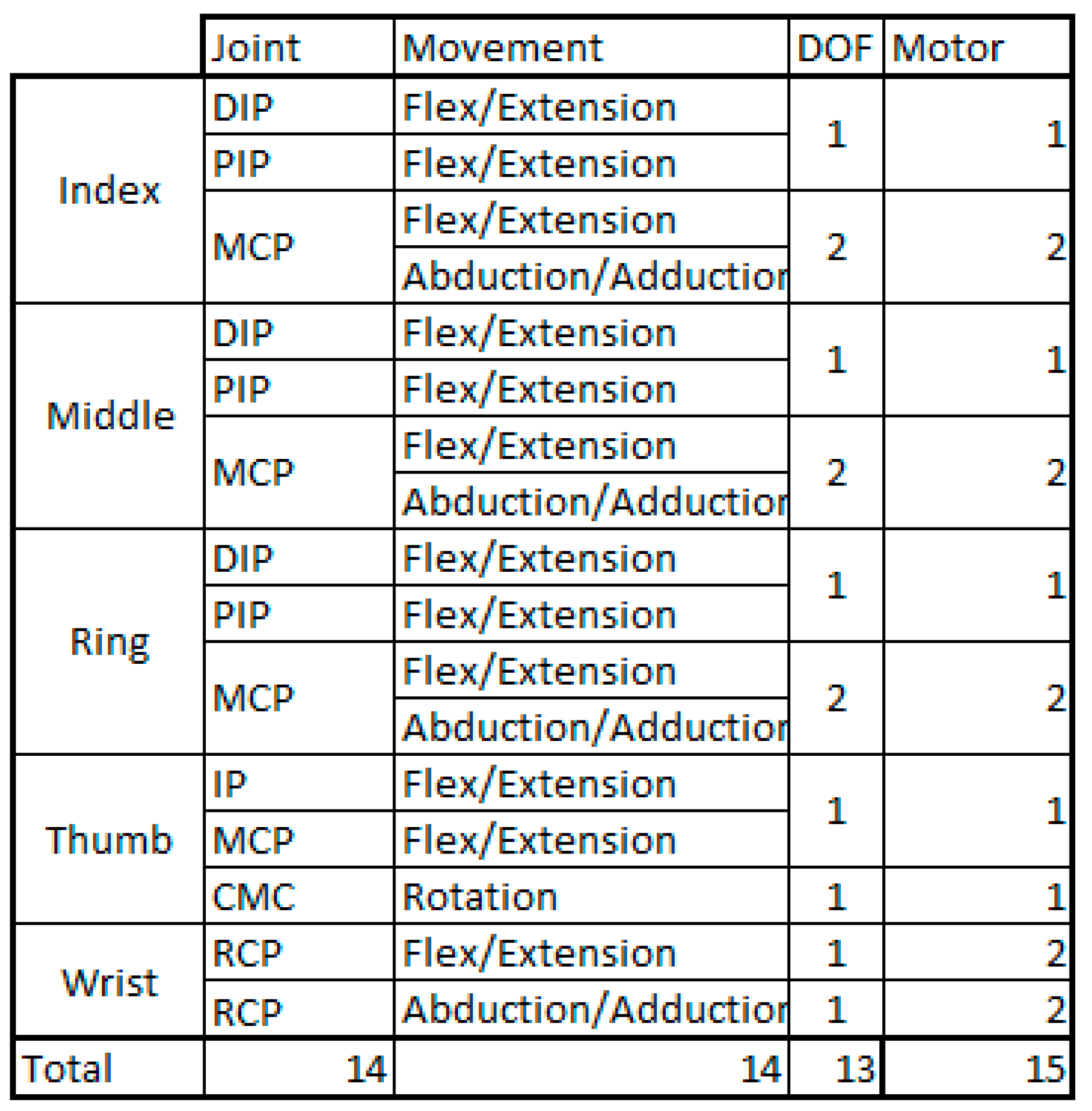

Figure 2 analyses the DOF-Joint relations. Total number of degrees of freedom is 13, distributed as follows. The three fingers, index, middle, and ring, have 3 degrees of freedom each, as they enable all human finger DOFs with flexion, abduction, and adduction. The thumb also has 2 degrees of freedom to mimic the human one. One DOF enables flexion and extension and the second DOF is a rotational joint that connects the palm with the thumb. The wrist has 2 DOFs, flexion-extension and abduction-adduction. This configuration allows the arm to perform both basic and more complex object manipulation movements, approximating the naturalness of human kinematics.

Figure 3 shows the robotic arm holding an egg.

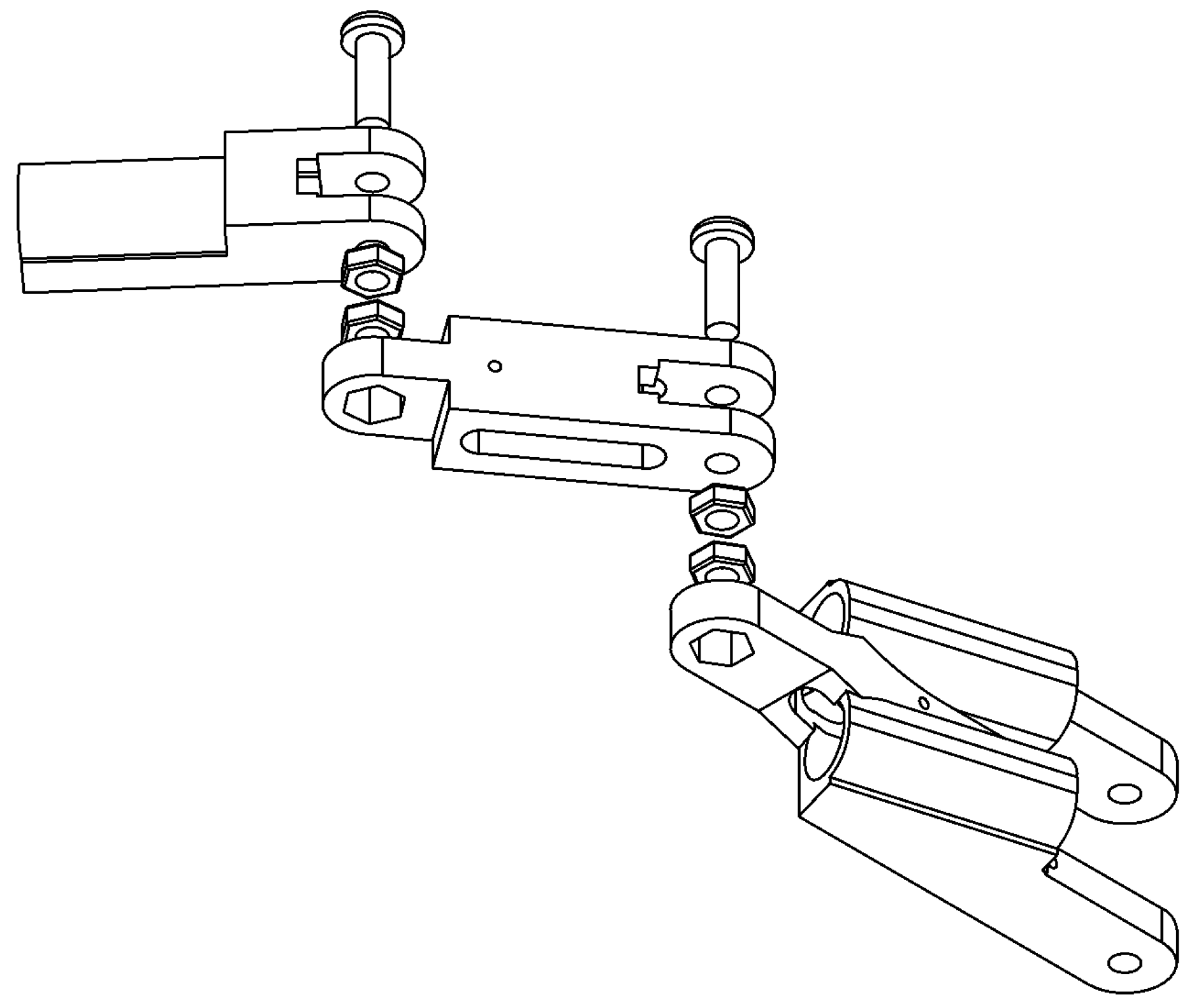

3.2. Materials and Construction Structure of the Robotic Arm

The mechanical structure of the robotic hand was designed with durability, low weight, and low-cost materials. The main parts of the fingers and wrist were made using 3D printing (FDM), using PLA and ABS materials, which offer sufficient mechanical strength and ease of replacement/modification. Small metal axles and screws were used for the joints, as shown in

Figure 4, to ensure smooth movement and resistance to repetitive loads. Motion is transmitted from the motors to the fingers via nylon thread, which acts as artificial tendons. This choice mimics the normal mechanism of the human hand, where tendons transfer movement from the muscles to the joints [

13].

This approach gives the robotic hand a high degree of biomimicry while reducing its volume, weight, and manufacturing cost. The construction is controlled by 15 servo motors distributed across the thumb base and wrist. Each finger (index, middle, ring) uses 3 servo motors. The thumb uses 2 servo motors. Finally, the wrist uses 4 servo motors. The motors were selected based on torque, speed, precision, and cost. For reliability reasons, servo motors with metal gears were used, reducing the risk of wear under repeated loads.

The “heart” of the system is the ESP32 microcontroller, which provides the necessary computing power to control the 15 servo motors, in conjunction with the PCA 9685 driver, while simultaneously managing wireless communication with the control glove. To implement a self-contained robotic arm, the use of batteries to power the system was deemed necessary. For this reason, four INR18650 batteries were selected, capable of providing sufficient power for the operation of all 15 motors, the development board, and the servo driver—two in parallel with two others in series. The motors are powered through a buck converter power supply board. This particular power electronics configuration was chosen to convert the nominal voltage of 7.4 V provided by the batteries to a stable value of 6 V. Both, the development board and the motor driver unit are powered by a different buck converter power supply board with a maximum output of 1.5 A, which covers the power requirements for the Arduino ESP32 Nano development board, as the maximum current consumption is 500 mA for the integrated processing unit [

14]. This configuration of the two buck converters prevents the appearance of ripple in the microcontroller’s power supply, which would otherwise result in distortion of the PWM signal [

15].

Figure 5 illustrates this configuration.

The ESP32 microcontroller was chosen over others because of its built-in Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, its support for the ESP-NOW protocol [

16], which permits low-latency communication without the need for a local router. It has a high processing speed (dual-core Tensilica LX6, up to 240 MHz) and low cost. The microcontroller receives data from the glove, translates it into movement commands, and executes the corresponding PWM pulses to the servo motors.

Each fingertip of the robotic hand is instrumented with a SEN0065 force-sensitive resistor (FSR), with the sensor mounted directly at the fingertip surface. The SEN0065 features a 4 mm (0.16”) diameter active sensing area, and two 0.1”-pitch leads for straightforward PCB or breadboard integration; the full sensor body measures approximately 1.75″ in length and 0.28” in width.

The SEN0065 operates as a passive variable resistor: with no applied force, its resistance exceeds 1 MΩ; as pressure is applied, resistance decreases—under full fingertip pressure its resistance can approach ≈2.5 kΩ.

In operation the sensor output is read via a simple voltage-divider circuit and analog-to-digital converter. This allows continuous (analog) measurement of contact pressure, enabling the system to detect and quantify fingertip forces during manipulation. Because the SEN0065 is a thin, polymer-film FSR optimized for human touch–style force sensing, it is ideally suited for applications requiring detection of contact, grasp, and pressure feedback—though it is not intended for high-precision force measurement comparable to a load cell or strain gauge.

Finally, like typical FSR devices, the SEN0065 exhibits fast response (on the order of milliseconds), very low power consumption, and a large dynamic range (from light touch to firm press), making it a practical and effective solution for providing real-time tactile feedback across all fingertips of the robotic hand.

3.3. Design and Implementation of the Haptic Glove

The implementation of the Haptic Glove, as shown in

Figure 6, is based on the Arduino Nano ESP32 microcontroller, which acts as the central processing and communication platform. The ESP32 offers Wi-Fi capabilities, allowing wireless connection to the arm without cable restrictions.

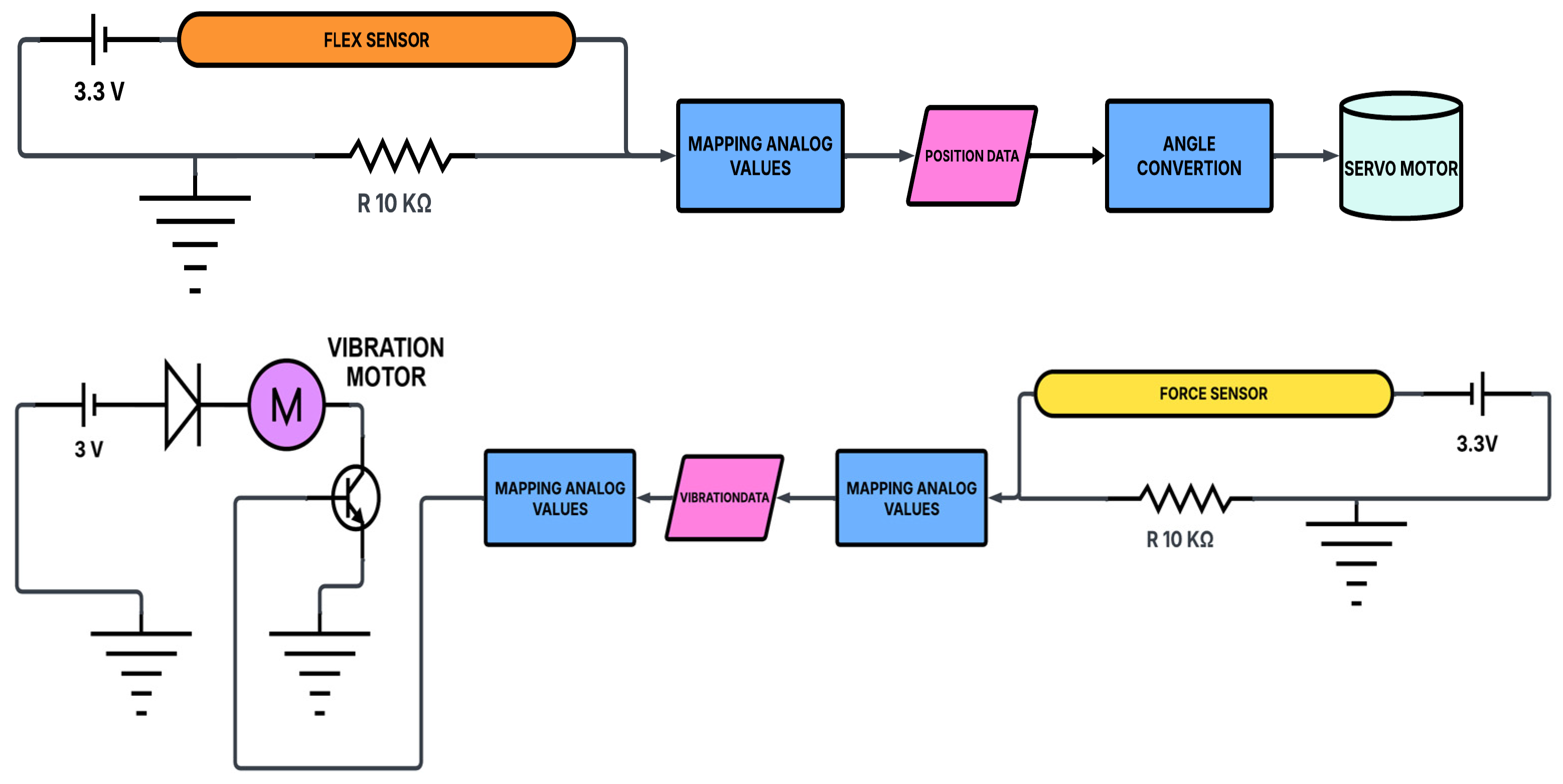

Flex sensors were integrated into the glove’s fingers to record the flexion angle, with each sensor connected via a voltage-divider circuit so that the microcontroller can convert resistance changes into analog voltage signals. The SEN10264 is a 2.2-inch (≈56 mm) resistive flex sensor, with an active sensing region of about 55 mm and a thickness of approximately 0.43 mm. In its neutral (flat) state the sensor exhibits a nominal resistance of roughly 25 kΩ (±30% tolerance); when bent, the resistance increases—depending on the bending radius, the resistance can climb to the order of 45 kΩ to 125 kΩ. The sensor supports continuous power dissipation around 0.5 W (with 1 W peak), and operates reliably across a temperature range from −35 °C to +80 °C.

In our design, one end of the SEN10264 is tied to a reference voltage (e.g., 3.3 V), while the other end is connected to ground through a fixed resistor. The junction between the sensor and the fixed resistor (10 KΩ) is connected to an analog input of the microcontroller. As the flex sensor bends, its resistance increases—the resulting change in the voltage at the junction is read by the ADC and mapped to flex angle. This simple voltage-divider configuration provides a stable analog output corresponding to finger flexion.

This setup, combined with independent pressure sensors (FSRs) on the robotic arm’s fingertips (providing force feedback), enables simultaneous capture of finger bending and contact force. Haptic feedback is then delivered to the user via vibration motors at the glove’s fingertips, while servo motors on the arm replicate the sensed motion (see

Figure 7). In the mechanical design the flex sensors were embedded in a neoprene glove to maximize comfort and wearability while ensuring reliable sensor placement and signal integrity.

To deliver this haptic feedback, each fingertip of the glove is equipped with an SS-0104 miniature vibration motor. These motors are compact (≈10 mm diameter, 1.23 g) and operate at 3 V with a typical current draw of 90–120 mA, making them suitable for wearable integration. Because the ESP32 cannot directly supply the current required to drive the motors, each unit is connected through a dedicated transistor-based driver circuit. Specifically, an NPN transistor (2N2222 type) is used in a low-side switching configuration, where the motor’s positive terminal is tied to the regulated supply and its negative terminal passes through the transistor collector; the emitter is connected to ground. The base of the transistor is driven by an ESP32 GPIO pin through a current-limiting resistor, ensuring proper base current and protecting the microcontroller. A flyback diode is placed across each motor to suppress inductive voltage spikes generated during switching, ensuring electrical stability and preventing damage to the transistor or ESP32.

During operation, when an FSR on the robotic hand makes contact with an object or an increase in applied force, the ESP32 activates the corresponding transistor, energizing the SS-0104 motor on the matching finger of the glove. This produces a localized vibration, allowing the user to perceive tactile events occurring on the robotic hand in real time.

To achieve wireless and autonomous operation of the system, the integration of a battery as a power source was studied and implemented. We opted for a 3.7 V 980 mAh and 3.63 Wh Li-Po (Lithium Polymer) battery. Since the battery cannot be integrated into the system by connecting it directly to the microcontroller, it is necessary to use an intermediate Lithium Battery Charger. The protection module 1A USB-C—TP4056 is necessary to protect the circuit from poor connections and to charge the battery.

3.4. System Communication

The system’s operation is based on two-way information flow. The user moves their fingers, and the bent sensors record the movements. The data is sent wirelessly to the arm, which adjusts the position of the joints via servo motors. When the arm touches an object, pressure sensors activate the vibration motors, transferring the sense of touch to the user.

The glove communicates with the robotic hand using the ESP-NOW protocol, which provides low latency (<10 ms), which is critical for real-time motion synchronization, reliable data transmission, and bidirectional communication, so that motion commands are sent from the glove to the arm and haptic feedback is sent from the arm to the glove. The choice of ESP-NOW makes the system more efficient and suitable for remote control applications, unlike the classic use of Bluetooth, which introduces delays.

Motion synchronization is achieved by mapping the values from the glove’s flex sensors, which are translated into the movement angles of the servomotors. The bending of the sensor is converted into an analog signal and then into an angular value. Each flex sensor on the glove is mapped to the corresponding finger of the robotic arm, so bending a finger on the glove directly controls the same finger on the arm. A linear interpolation filter is applied to this value for a smooth transition from one position to another. As the user moves their hand, the robotic arm mirrors each finger and joint motion instantly and with high accuracy, providing a highly faithful real-time imitation. Data is exchanged in packets containing both the current status of the sensors and the commands to the actuators. The result is a handling experience that simulates real interaction with objects, see

Figure 8.

The system was programmed in Arduino IDE. The code was organized into structures that allow for direct and reliable communication. For each finger, a struct object is created which contains the following parameters:

The input pin of the bending sensor value;

The minimum reading value minValue;

The maximum reading value maxValue;

The vibration activation output pin vibrationPin.

The microcontroller reads the values of the bending sensor, converts them into degrees of angle through a mapping, where the minimum value minValue corresponds to 0 degrees and the maximum value maxValue to 90 degrees. This value is filtered by a low-pass EMA (Exponential Moving Average) filter for smooth and more stable finger movement. It then converts the values to JSON format and sends them to the arm via the local ESP-NOW network.

At the same time, the robotic arm receives the values in JSON format and converts them back to degrees of angle to activate the servo motors. At the same time, for each finger of the arm, a struct type object is created, as in the glove, which contains as parameters:

The motor activation output pin

The angular value (received)

The pressure sensor value input pin

The pressure sensor value

It then activates the servo motors to turn to the appropriate position. At the same time, it reads the pressure sensor value from each finger and converts it to JSON format to send it to the glove. Finally, the glove receives the pressure value from the arm and compares it with the threshold set to activate the vibrating feedback.

3.5. Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted with the aim of finding the optimal energy consumption of the robotic arm during the grasping of various objects through the manipulation of the haptic glove. It was also monitored the time needed to achieve the grasp at the optimal consumption point. The recordings of the energy and time were obtained using a Joulscope JS220 by Jetperch LLC (Olney, MD, USA). The Joulscope was placed between the batteries and the two DC-DC converters and through the Joulscope UI (v. 1.3.6), that is provided by Jetperch LLC, we generated energy usage. Firstly, the grasp point was measured for each object separately, with and then without vibratory feedback. The time it took the user to achieve the grasp of the objects at the optimal point of consumption was also recorded. Three objects were selected from the list of household objects presented by Y. S. Choi, T. Deyle, T. Chen, J. Glass, and C. Kemp (ICORR 2009) [

17] and were evaluated as most important for retrieval by robotic systems, as determined by ALS patients through interviews and evaluations, more specifically:

The experiment goes as follows, each participant underwent two procedures, first they would grip the robotic hands gripper with full force through the haptic glove while recording the average energy consumption of the robotic hand. Then they would rest for about two or three seconds and afterwards they would grip the hand again with full strength aiming to find the optimal point. The optimal point is the position where the robotic hand holds the object but consumes less energy compared to when the user applied full force. We measured the average energy consumption at full force, the average energy consumption at the optimal point for each participant and we also recorded the time required for each participant to identify the optimal point. We also present standard deviation for each object.

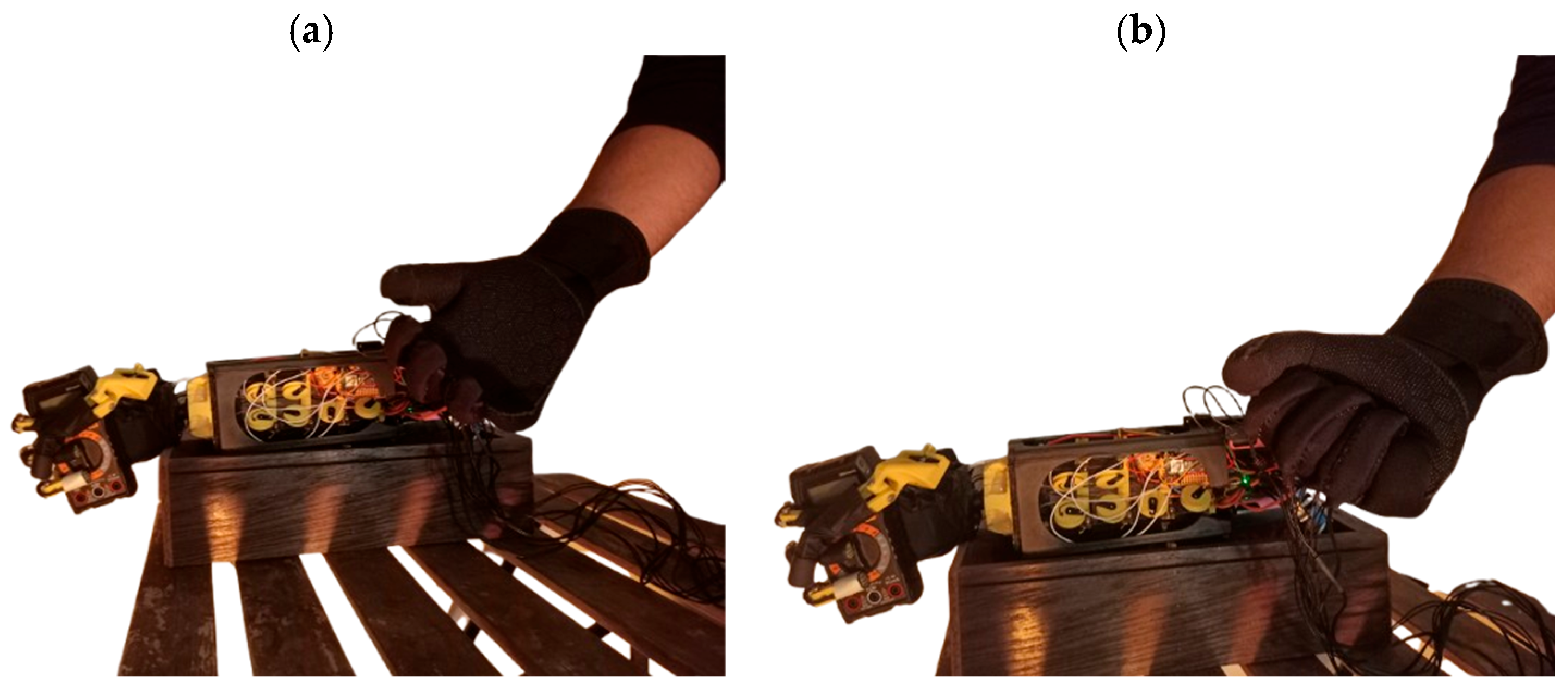

Following the aforementioned procedures, both with and without vibratory feedback, the operator positioned each of the specified objects within the gripper, which was securely mounted to the side of a platform, as illustrated in

Figure 9. Additionally, the participant was able to monitor the energy consumption in real time through a digital oscilloscope (Joulescope, Olney, MD, USA).

4. Results

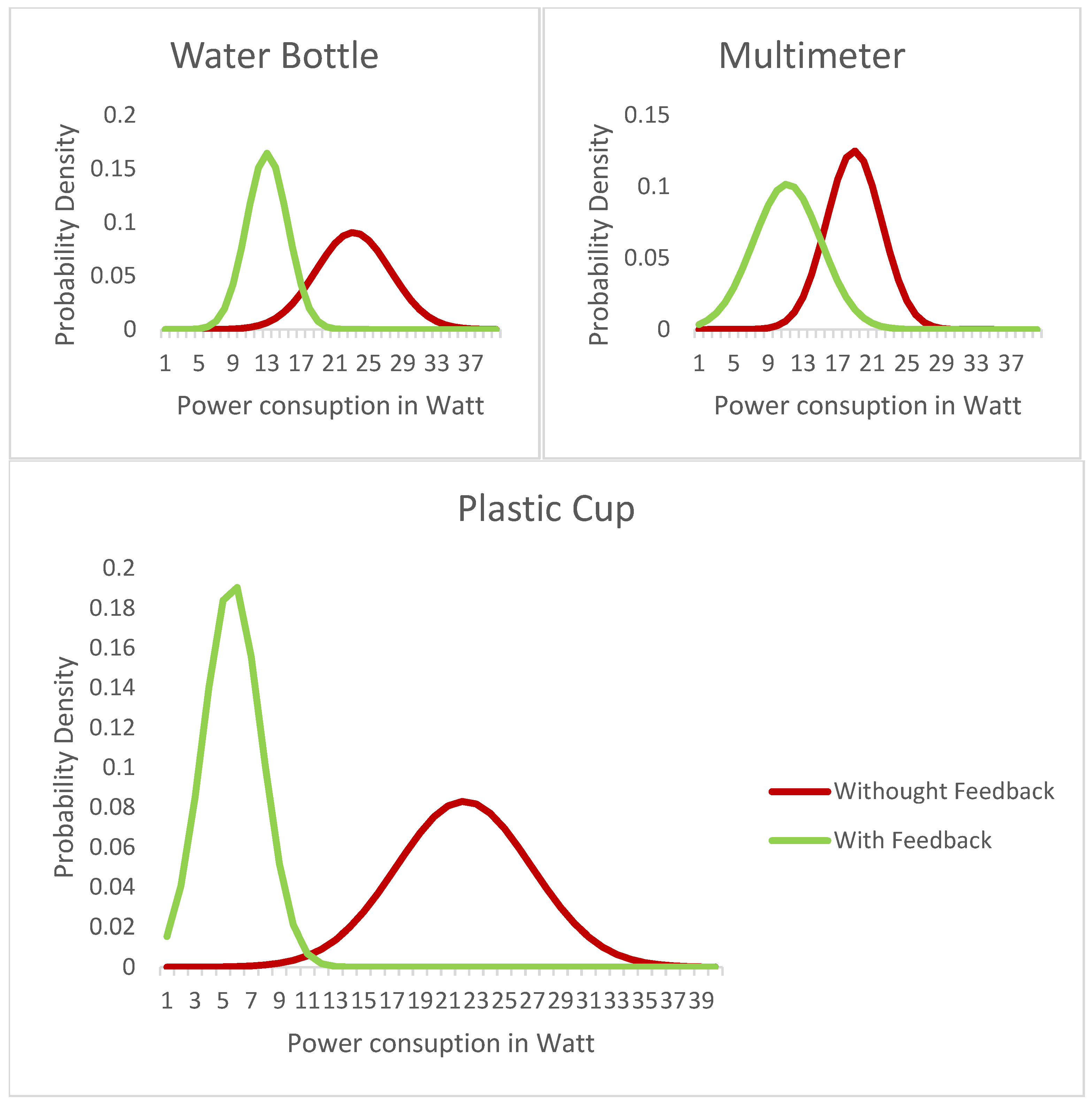

Using the haptic glove without the haptic feedback function, the operator performed the action of closing the gripper. While closing the gripper, the robotic arm exhibited maximum energy consumption. This phenomenon is attributed to the fact that the operator’s palm closing movement translates into a full closing command for the mechanical gripper. As the finger segments of the gripper came into contact with the surface of the object, the required torque of the electric motors increased significantly, resulting in an increase in the total power required. The experiment was then repeated, this time activating the haptic feedback function in the glove. During the experiment, it was observed that the presence of haptic feedback allowed the operator to perceive the moment of first contact between the gripper and the object. This improved sensory information led to more refined control of the position and pressure of the gripper. As a result, the operator was able to optimally modify the trajectory and gripping force, avoiding unnecessary or excessive movements that lead to a sharp increase in torque. Consequently, there was a significant reduction in the total power required to operate the electric motors while achieving smooth and controlled rotation.

Figure 10 shows the gripping of the multimeter with and without the tactile feedback function in the glove. In the case of haptic feedback, the user has awareness of the holding object and holds his hand posture more relaxed.

Figure 11 shows experimental data, highlighting the difference in power consumption while enforcing the vibration interaction.

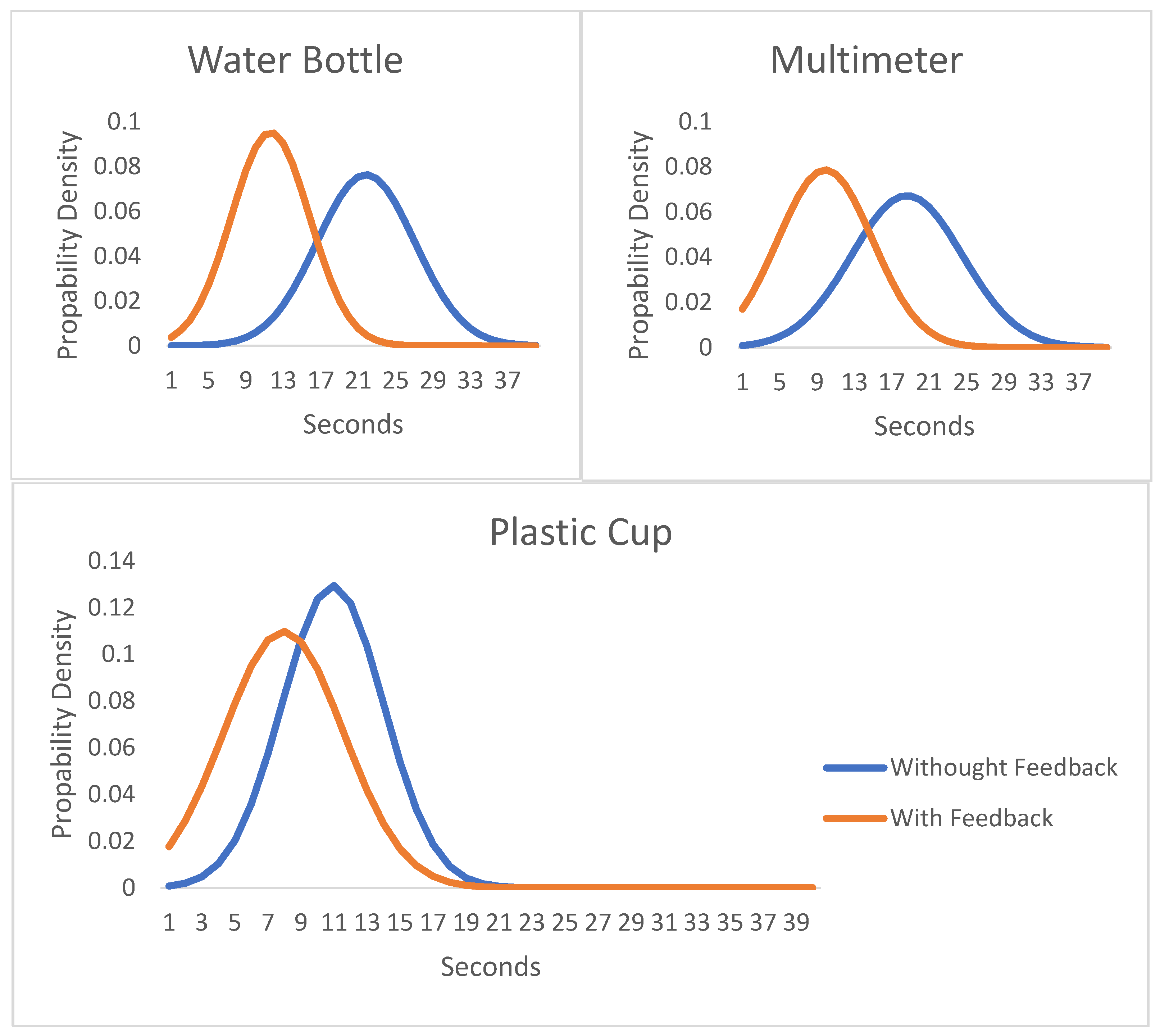

In the second stage of the experimental procedure, the time required to grasp the objects was systematically recorded and measured, with the aim of achieving the optimal position in terms of energy consumption. This method was applied under two distinct conditions: First, with the haptic feedback function activated, and later without its use. The chronometric data obtained shows a clear difference between the two conditions, as shown in

Figure 12. Specifically, under tactile feedback conditions, a reduction in the time required to locate and finally grasp the optimal point was observed, compared to the corresponding results obtained without tactile feedback. This observation suggests that access to tactile information improves the efficiency and accuracy of the process, leading to faster goal achievement while minimizing energy expenditure.

A total of 11 participants completed the post-experiment questionnaire. Overall, the responses indicated a positive evaluation of the haptic-feedback system used to control the robotic arm. Most participants reported that the grasping sensations were realistic, with 54.6% rating the feedback as “high” or “very high”. Perceived ease of control also scored favorably, while 81.8% of respondents stated that haptic feedback improved their ability to manipulate the robotic arm compared to trials without feedback. In terms of usability, the glove was rated as comfortable by most of participants. User responses indicate that the glove imposed minimal physical strain, with the majority of participants reported low levels of fatigue throughout the manipulation trials. Collectively, the questionnaire data demonstrates that participants experienced improved control, greater confidence in task execution, and overall enhanced user experience when haptic feedback was enabled.

5. Discussion

This study presented the design, implementation, and experimental evaluation of a teleoperation system integrating a biomimetic robotic arm and a custom haptic glove with bidirectional tactile feedback. The primary objective was to investigate the effect of vibrotactile feedback on the performance and efficiency of remote object manipulation. The experimental findings conclusively demonstrate that the integration of tactile feedback yields statistically significant benefits. Compared to teleoperation without haptic cues, the system with enabled feedback resulted in:

Users achieved more precise control over the robotic gripper, allowing for finer adjustments during object contact and grasp stabilization.

The time required to achieve a stable and efficient grasp was notably shorter, as the tactile signal provided an immediate and intuitive indication of contact, streamlining the manipulation process.

A significant reduction in overall power consumption was observed. The haptic feedback enabled users to modulate the gripping force more effectively, avoiding excessive motor torque and the associated energy spikes during object contact.

These results underscore the critical role of haptic feedback in closing the perception-action loop in teleoperation, transforming it from a purely visual task to a multi-sensory one. This leads to more refined motor control, mimicking the natural human ability to use touch for manipulation, which is paramount for applications requiring dexterity and delicacy.

Since the proposed setup aims for low-cost implementation the biggest drawback is the low quality of the materials and consequently this makes the construction sensitive and unreliable over time, after the use of the system by the participants. Regarding the choice of specific tactile sensing. This technology was chosen because it is low cost and easy to integrate into the system. However, there are also other promising technologies such as piezoelectric sensors, capacitive touch sensors and optical tactile sensors each with its own advantages and applications. Prospects include the integration of more sophisticated touch sensors capable of capturing texture and temperature, as well as the development of robot fingers with a more natural sense of touch. Increasing the surface area of the force sensor would also provide better contact and a more accurate understanding of the grasped object. Furthermore, incorporating machine learning techniques to predict movements and optimizing wireless communication for near-zero latency would offer substantial upgrades to the system. Although our current implementation is not yet mature enough for high-stakes applications such as telesurgery, advanced virtual-environment training, or industrial production, it already delivers solid and valuable user experience. Finally, transitioning to a flex PCB for the wiring would represent another significant improvement for the next iteration of the design.

6. Conclusions

In summary, this work validates the hypothesis that tactile feedback is a crucial enabler for efficient and intuitive teleoperation. The proposed system represents a significant step toward more natural and effective human–robot interaction, with promising potential for deployment in complex fields such as minimally invasive telesurgery, remote exploration, and advanced assistive technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P. and K.G. and G.K.; methodology, C.P. and M.S.P.; software, C.P. and G.K.; validation, C.P. and K.G.; formal analysis, C.P., K.G. and G.K.; investigation, C.P. and K.G.; resources, C.P. and K.G.; data curation, C.P. and K.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P., K.G. and G.K.; writing—review and editing, G.K. and M.S.P.; visualization, G.K. and M.S.P.; supervision, M.S.P.; project administration, G.K. and M.S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are provided on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| FSRs | Force-Sensitive Resistors |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| RMIS | Robot-assisted Minimally Invasive Surgery |

| SPETH | Self-Powered Electrotactile Textile Haptic |

| TENGs | TriboElectric NanoGenerators |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| EMA | Exponential Moving Average |

| DIP | Distal interphalangeal |

| PIP | Proximal interphalangea |

| MCP | Metacarpophalangeal |

| IP | Interphalangeal |

| CMC | Carpometacarpal |

| RCP | Radiocarpal |

References

- Tian, L.; Magnenat-Thalmann, N.; Thalmann, D.; Zheng, J. A Methodology to Model and Simulate Customized Realistic Anthropomorphic Robotic Hands. In Proceedings of the Computer Graphics International 2018, Bintan Island, Indonesia, 11–14 June 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; DelPreto, J.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Weisz, J.; Allen, P.K. A Highly-Underactuated Robotic Hand with Force and Joint Angle Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 September 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle, E.; Benson, W.N.; Anderson, Z.; Weinberg, J.B.; Gorlewicz, J.L. Design and Implementation of a Haptic Measurement Glove to Create Realistic Human-Telerobot Interactions. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 9781–9788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, J.; Bianchi, M.; Ferrari, V. Integrated Haptic Feedback with Augmented Reality to Improve Pinching and Fine Moving of Objects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, H.; Patel, A.S.; Gandotra, P.; Kherani, A.A.; Lall, B. Enabling Edge Intelligence in Remote Robot Control: Architecture, Prediction Mechanism and Offloading. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommunications Systems (ANTS), Gandhinagar, India, 18–21 December 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 359–362. [Google Scholar]

- Colan, J.; Davila, A.; Hasegawa, Y. Tactile Feedback in Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Surgery: A Systematic Review. Robot. Comput. Surg. 2024, 20, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Chen, J.; Ye, G.; Dong, S.; Gao, Z.; Zhou, Y. Soft Robotic Glove with Sensing and Force Feedback for Rehabilitation in Virtual Reality. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudici, G.; Bonzini, A.A.; Coppola, C.; Althoefer, K.; Farkhatdinov, I.; Jamone, L. Leveraging Tactile Sensing to Render Both Haptic Feedback and Virtual Reality 3D Object Reconstruction in Robotic Telemanipulation. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyriac, M.; Gopakumar, A.; Nazeer, N.P.; Ds, S.; Warrier, S. Haptic Glove Guided Robotic Arm. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2025, 7, 35718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Zhao, G.; Fu, J.; Yao, K.; Jia, S.; Shi, R.; Huang, X.; Wu, P.; Li, J.; et al. Self-Powered Electrotactile Textile Haptic Glove for Enhanced Human-Machine Interface. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt0318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapandji, I.A. The Physiology of the Joints: Annotated Diagrams of the Mechanics of the Human Joints, 5th ed.; Honoré, L.H., Translator; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchi, A. Hands for Dexterous Manipulation and Robust Grasping: A Difficult Road toward Simplicity. IEEE Trans. Robot. Automat. 2000, 16, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.L.; Dalley, A.F.; Agur, A.M.R. Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 7th ed.; Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arduino Nano ESP32 Product Reference Manual. 2023. Available online: https://www.mouser.com/pdfdocs/ABX00083-datasheet.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- NORA-W10 Series Data Sheet. 2025. Available online: https://content.u-blox.com/sites/default/files/documents/NORA-W10_DataSheet_UBX-21036702.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- ESP32-S3 Series Datasheet. 2021. Available online: https://www.espressif.com/sites/default/files/documentation/esp32-s3_datasheet_en.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Choi, Y.S.; Deyle, T.; Chen, T.; Glass, J.D.; Kemp, C.C. A List of Household Objects for Robotic Retrieval Prioritized by People with ALS. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, Kyoto, Japan, 23–26 June 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).