Abstract

This systematic literature review uses the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology to assess progress in blockchain-based Federated learning (FL) and Machine Learning (ML) for detecting financial fraud over the last five years (2020–2025). An initial pool of 29,274 records identified across IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and ScienceDirect yielded 1585 peer-reviewed studies that met the inclusion criteria. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches were used. The examined papers were classified according to algorithm type, fraud types, and evaluation measures. Credit card fraud and cryptocurrency fraud dominated the literature, with supervised learning (e.g., XGBoost, 95% accuracy) and federated learning (e.g., FedAvg, 91% accuracy) emerging as dominant methodologies. Centralized ML outperforms FL in latency but poses privacy risks. FL–blockchain hybrids reduce false positives. While precision, recall, and F1-score are commonly used, few studies use cost-sensitive criteria. Future research should prioritize adaptive FL aggregation, privacy-preserving ML, and cross-industry collaboration.

1. Introduction

Financial fraud is a major issue in industries such as banking, insurance, and healthcare, resulting in enormous economic losses and societal harm [1,2]. Traditional detection approaches, which rely on human processes, are inefficient, expensive, and prone to errors [3,4]. As the number of digital transactions increases, fraudsters use more complex strategies necessitating better detection mechanisms [5,6].

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have developed as effective fraud detection methods, utilizing big datasets to discover aberrant patterns [7,8].

Supervised and unsupervised machine learning approaches, including classification algorithms, are frequently employed [6,9]. However, centralized ML techniques face several issues, including data privacy concerns, single points of failure, and vulnerability to adversarial attacks [10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Blockchain technology provides a decentralized, transparent, and immutable framework for fraud detection systems, increasing their security and trustworthiness [17,18,19,20]. Coupled with federated learning (FL), a privacy-preserving ML paradigm in which models are trained cooperatively without disclosing raw data [21,22] addresses significant drawbacks of centralized systems [23,24,25,26]. FL addresses privacy problems under legislation such as GDPR [27], whilst blockchain ensures auditability and resilience to tampering [28,29]. Despite increased interest, recent studies have mainly focused on specific sectors such as credit card fraud [30,31], healthcare fraud [32], and payment fraud [33], with no systematic comparison of blockchain–FL frameworks to standard ML. Recent research has highlighted FL’s potential for fraud detection [34,35] and blockchain’s role in securing FL [18,36,37] but none have thoroughly evaluated their combined efficacy for financial fraud [38]. Recent architectural work proves a unified blockchain-enabled FL framework is capable of cross-silo collaboration and secure update verification, underscoring the feasibility of such integration in financial domains [39]. However, recent emphasis on the emerging need for comparative frameworks and privacy-preserving mechanisms in federated learning for financial fraud detection stresses the same research gap addressed here [39].

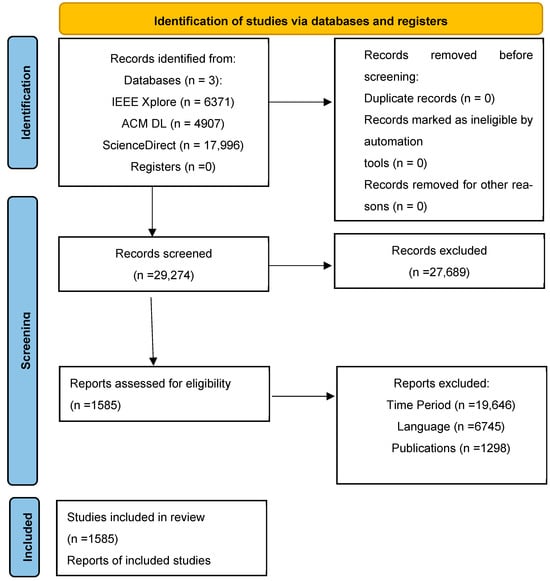

This systematic literature review (SLR) closes the gap by identifying blockchain-based fraud detection systems with ML/FL integrations [20,24,40,41]; comparing the performance, privacy, and scalability of FL and standard ML for fraud detection [34,42,43]; evaluating datasets (e.g., Fed-Fraud [44]) and metrics for blockchain–FL research [26,36]; highlighting research gaps, including adversarial attacks [11,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] and regulatory compliance [27]; and comparing decentralized and centralized ML techniques [24,26,41,52]. Prior reviews emphasized components of FL, blockchain, or IoT security but rarely provided a systematic comparison of ML against FL for financial fraud or synthesized differential privacy constraints specific to finance [53,54]. The Study Selection Process is presented as a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1. The search strategy commenced with an extensive search across three major academic databases, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and ScienceDirect, yielding a total of 29,274 records. No additional records were identified through registers or other sources. After exclusions by time period (n = 19,646), language (n = 6745), and publication type (n = 1298), 1585 studies were included in the final review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search strategy.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the research methodology, including the search criteria, study selection, data extraction, and quality evaluation. The SLR findings and the responses to the study questions are subsequently presented. The results and possible challenges that undermined the validity of this review are addressed, respectively. Finally, we provide a discussion and a conclusion of the study in the last section. This review helps researchers choose approaches for secure, scalable fraud detection. In this section, we present the results of the 1585 studies that met our inclusion and quality assessment criteria.

We included only those studies that satisfied our rigorous selection standards and were not flagged for bias during the screening process. Once the studies passed our inclusion criteria and underwent thorough coding and analysis, we did not conduct further bias assessments on their internal findings. Previous reviews often excluded recent conference papers and emerging empirical studies. Our analysis was based on quantitative descriptive summaries derived from these high-quality studies.

2. Materials and Methods

With financial services going digital, there is a lot more data out there for payment fraud, credit card fraud, scams, identity theft, and money laundering, etc., despite the ability for fraud detection with ML and blockchain technology. Blockchain’s secure ledgers and federated learning could help train models together without exposing private information [55,56]. However, these technologies remain under integrated in practice. Other options like basic rule-based systems and centralized ML make things worse, with a lot of false alarms, slow detection, and easy data hacks. So, this review compares machine learning and federated learning in the blockchain world, bridging the gap between theoretical advances and real-world implementation. The PICOC (Population Intervention Comparison Outcome Context) framework is written in Table 1.

Table 1.

PICOC framework.

Research String:

(“Blockchain”)

AND

(“Machine Learning” OR “Federated Learning” OR “Financial Transactions”

OR “Fraud Detection”)

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are written in Table 2.

Table 2.

Exclusion and inclusion criteria.

Quality Assessment Questions (QA)

(Each QA item was scored 0–2 (low to high) and the total score determined inclusion quality)

QA1: Is the domain of the study related to financial fraud detection? (2)

QA2: Does the study apply machine learning, federated learning, or blockchain for fraud detection? (2)

QA3: Are evaluation metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score or AUC clearly reported? (2)

Research Questions:

RQ1: What are the machine learning techniques employed for financial fraud detection employed in the literature?

RQ2: What are the evaluation metrics employed to detect financial fraud?

RQ3: What are the different types of financial fraudulent transactions covered in the literature review?

RQ4: How do blockchain-based federated learning and machine learning approaches differ in detecting financial fraud?

RQ5: What are the machine learning techniques employed for financial fraud detection employed in the literature?

ML has significantly changed how we catch money fraud. Each method is good at spotting different kinds of fake transactions. We can sort these methods into supervised, unsupervised, and hybrid types. We will look at how they perform, how they work, and how they are used in real life to stop fraud. By investigating these methods, we want to make it easier to understand what they are good at and what they are not good at when it comes to protecting money from new fraud tricks.

The extracted machine learning methods used across the selected studies are listed in Table 3, providing insight into how financial fraud detection has been approached in the literature.

Table 3.

Machine learning techniques employed for financial fraud detection as identified in the literature.

Federated Averaging (FedAvg):

FedAvg enables decentralized collaborative training without data sharing [22,97]. Clients train locally and share updates, which are averaged into a global model. It achieves 91–92% accuracy and 0.89 F1 [22,56], proving effective in healthcare and finance [56,68]. However, it faces poisoning risks, straggler issues, and reduced accuracy with skewed data [73,74].

Support Vector Machine (SVM):

SVM constructs optimal hyperplanes for classification, excelling in high-dimensional fraud detection with 94% precision and 0.91 recall. Kernel functions enable non-linear mapping, boosting resilience [31]. It outperforms LR and DT in imbalanced datasets [17,60], though it needs careful tuning. Despite scalability limits, it remains favored in regulated industries due to interpretability and risk minimization [31,59].

Random Forest (RF):

RF gathers multiple decision trees, reducing overfitting and achieving AUC-ROC 0.95–0.97. It handles imbalanced and noisy data effectively and is widely applied in credit rating and anomaly detection. While computationally heavier than single trees, RF’s robustness, parallelization, and adaptability ensure strong adoption in finance and cybersecurity [3,6,17].

LSTM Autoencoders:

These deep models combine autoencoder compression with temporal modeling, achieving 88% anomaly detection in federated setups [83]. They preserve privacy by only sharing parameters, which is useful in IoT and healthcare. Applied to sequential anomalies, they detect faults and abnormal signals [32]. Recent improvements include differential privacy and attention mechanisms [89,98].

XGBoost:

A gradient-boosted tree algorithm achieving 95% accuracy and 0.93 F1 in fraud detection. Its regularization, parallelism, and imbalance handling make it superior to simpler ML models [6]. However, it requires fine-tuning and is less interpretable [59]. XGBoost is widely applied in credit risk, fraud scoring, and anti-money laundering [66].

Federated XGBoost:

An FL variant using secure aggregation, achieving 90% accuracy and 0.88 AUC [68,69]. It preserves privacy while retaining strong predictive power compared to centralized XGBoost [6]. Cryptographic costs add complexity, but hybrid blockchain approaches improve security [99]. Studies show it outperforms FedAvg in tabular fraud tasks [66].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs):

GNNs model fraud as transaction graphs, detecting organized fraud with 89% recall [24]. They propagate relational information, outperforming non-graph ML by 18–30% [59,70]. Despite challenges in scaling and adversarial attacks, attention-based GNNs (GAT) improve performance. Applications include cryptocurrency and DeFi fraud detection [72].

FedProx:

FedProx introduces a proximal term to stabilize training with non-IID data, achieving 91% accuracy. It outperforms FedAvg in heterogeneous cross-silo settings like healthcare [73]. By mitigating stragglers and integrating differential privacy, it improves FL robustness [62,74]. It is being increasingly applied to finance under data restriction challenges.

Differential Privacy FL:

DP-FL adds calibrated noise to protect updates, ensuring ε = 2.0 privacy with 87% accuracy. It safeguards GDPR/HIPAA compliance in sensitive domains [27,77]. While noise reduces accuracy (up to 15% vs. non-private FL), it is stronger than k-anonymity [100]. Ongoing work is combining it with secure multiparty computation for resilience [94].

Q-Learning (Reinforcement Learning):

A reinforcement learning method that adapts policies in real time, reaching 93% accuracy in FL settings. It handles shifting fraud strategies and non-stationary patterns [11]. Blockchain-enhanced versions ensure secure logging and integrate Deep Q-Networks [68,82]. Studies show 16–20% recall improvement over rule-based systems [11].

Decision Tree (DT):

DTs achieve 88–92% accuracy in fraud detection, offering transparency, which is critical in banking regulation. They are prone to overfitting unless pruned but remain efficient for credit scoring. Recent hybrids improve anomaly detection in imbalanced fraud datasets. Their interpretability ensures continued relevance in fintech [9,17,21].

Logistic Regression (LR):

LR achieves 86–88% AUC-ROC in fraud detection. It is fast, interpretable, and regulator-friendly but struggles with non-linear patterns. Regularization (L1/L2) improves performance, though ensembles outperform LR by 5–10% [30,101]. Federated LR extends its use to privacy-preserving cross-bank applications [56,69].

Deep Neural Networks (DNNs):

DNNs achieve 90–93% F1-scores, capturing complex fraud patterns in high-dimensional data. Applications include NLP-based fraud analysis and check forgery detection. However, they demand high computation and labeled data [5]. Federated DNNs reduce risks of gradient leakage while enabling collaboration.

Autoencoders:

Unsupervised models with 88–91% accuracy in anomaly detection. They learn normal transaction patterns and detect deviations. Hybrid autoencoders with attention or SHAP improve interpretability and robustness. Real-world applications report a 30% false positive reduction in payment monitoring [1].

Isolation Forest (IF):

An unsupervised method using random splits, achieving 89% detection [14,84]. It is efficient (O(n)) and scalable, outperforming One-Class SVM in speed [34]. Extended IF improves stability for categorical features [85]. Deployed in banking, it cuts fraud inquiry times by 40% [84].

K-Means Clustering:

Detects suspicious groups with 77–85% cluster purity. Useful where labeled data is scarce, especially for AML. Variants like X-Means improve performance though are sensitive to scaling and K value [63,86]. Secure multi-party K-Means supports collaborative fraud detection [68]. Real deployments reduce false positives by 25% [86].

AdaBoost:

An ensemble-boosting model achieving 93% accuracy on imbalanced fraud data [21,60]. It emphasizes hard-to-classify cases and preserves interpretability [21]. Federated AdaBoost secures collaboration by exchanging only classifier weights [102]. Recall improvements of 15–20% are reported for minority fraud classes [60].

LightGBM:

A gradient-boosting framework with 94% AUC-ROC. Optimized for speed and large datasets, it supports categorical features and GPU acceleration [6,17]. Federated LightGBM secures distributed training [66,69]. In real deployments, it reduces false declines by 15% and improves fraud detection by 30% [17].

SMOTE + Random Forest:

Hybrid method addressing class imbalance with 91% recall. Used in rare fraud and medical claim datasets. It reduces false negatives by 40% compared to under- sampling [89]. Federated variants preserve privacy while sharing synthetic data [62].

Transformer Models:

Achieve 92% F1-score in sequential fraud detection [91]. They capture contextual dependencies in transactions and support transfer learning (e.g., Fin BERT) [89]. High computational costs are mitigated by aggregation and gradient masking in FL [103]. Real-world deployments detect coordinated multi-merchant attacks effectively [91].

Hybrid SVM-DT:

Combines SVM’s classification strength with DT interpretability, reaching 90% precision [10]. Effective in regulated credit scoring where explanations are required [5]. Federated implementations ensure decentralized learning [104]. Studies show an 18% reduction in unjustified rejections compared to standalone models [10].

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL):

Achieves 95% adaptive accuracy for fraud detection in FL. Excels in dynamic contexts like cryptocurrency fraud. Innovations include curiosity-driven exploration and blockchain-secured logging [11,82]. Applied in AML, it improves fraud response times by 30% [105].

Homomorphic Encryption FL:

Enables encrypted model training with 86% accuracy. Though 10–100× slower, hardware acceleration aids deployment in SWIFT monitoring [62]. EU GDPR drives adoption, keeping performance within 5% of plaintext models. Hybrid methods combine encryption with secure multi-party computation for efficiency [91,93].

Zero-Knowledge Proof FL:

Provides verifiable model integrity with 88% accuracy [96]. Useful in credit scoring and AML audits [106]. Blockchain-enabled ZKPs ensure audit trails and detect poisoning attacks [107]. They address data sovereignty concerns in cross-border fraud networks, enhancing trust [96]. With their own benefits, FL and ML techniques have shown great promise in blockchain-based fraud detection systems as in RQ1.

RQ2: What are the evaluation metrics employed to detect financial fraud?

In order for fraud detection algorithms to be effective, their performance must be rigorously evaluated using metrics that take into consideration the unbalanced nature of financial datasets, where illicit transactions make up a very small portion of total activity. In these situations, traditional accuracy metrics frequently turn out to be deceptive, leading researchers to use specialized metrics that more accurately reflect model precision, recall trade-offs, and economic consequences [15]. The main assessment frameworks used in the literature are examined in this part, along with their applicability to various fraud detection scenarios. These frameworks include precision-recall analysis, ROC-AUC, F1-score, and cost-sensitive metrics. We examine how these metrics tackle important issues such as unreported fraud cases and false positives in transaction monitoring, giving practitioners a methodological basis on which to choose the best validation techniques for their particular use cases. The evaluation metrics are written in Table 4.

Table 4.

Evaluation metrics.

In financial fraud detection, the evaluation metric is critical for assessing model performance [87,101,118,119].

However, no defined assessment measures are strictly employed to evaluate ML methods for fraud detection [101]. Different researchers have recently used a variety of performance evaluations as shown below:

Accuracy:

Accuracy = (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN) measures overall correctness [3,17]. In fraud datasets with >99% legitimate cases, it can be misleading (e.g., 99% accuracy with 0% fraud detection) [21]. Studies show it overestimates performance by 16–30% compared to balanced metrics [17]. It should be reported only alongside class-sensitive metrics like F1 [3].

Precision:

Precision = TP/(TP + FP), vital where false positives incur costS. Banking systems often prioritize >90% precision to maintain trust, though this lowers recall [71]. Precision is GDPR-relevant under “right to explanation”. Increasing thresholds (95% → 98%) may cut fraud detection by 40% [31,59].

Recall (Sensitivity):

Recall = TP/(TP + FN), crucial where missed frauds are costly. Banks often tolerate more FPs to maximize recall, though this raises review workload [108]. In FL, recall variance highlights fraud heterogeneity (e.g., 15% gap between banks). High recall may increase costs by 25–50% [6,115].

F1-Score:

F1 = 2. (precision × recall)/(precision + recall), balancing both [56,68]. It is more reliable than accuracy for imbalanced fraud data, with Kaggle winners prioritizing it 3:1 [42]. Yet, equal weighting may mask real-world trade-offs (e.g., 80/90 vs. 90/80 precision/recall yield the same F1 = 0.85) [68].

Specificity:

Specificity measures correct recognition of legitimate cases, often >99.9% in fraud systems [9,21]. Even 0.1% FP can cause thousands of alerts in high-volume systems [87]. Thresholds are adjusted seasonally (e.g., holiday shopping surges) to minimize customer disruption [21].

AUC-ROC:

AUC-ROC measures discrimination across thresholds [17,59]. It is threshold-independent, making it good for early model selection. However, with an imbalance a 0.95 AUC may still miss 40% of fraud [71]. Basel III rates AUC ≥0.90 as “excellent” for compliance reporting [59].

False Positive Rate (FPR):

FPR = FP/(FP + TN), directly tied to costs and customer satisfaction [3]. Banks typically cap FPR at 0.5%, requiring ensemble methods [111]. Even a 0.1% drop in FPR can save ~USD 2M annually in AML investigations [114].

False Negative Rate (FNR):

FNR = FN/(FN + TP), where missed fraud poses high risk [30,101]. Credit networks apply tiered FNR (2% for standard vs. 0.5% for premium clients) [40]. Deep learning reduces FNR by ~30% compared to classical models but raises compute costs by 5–8× [101].

AUC-PR:

Better than ROC for extreme imbalance, especially in crypto fraud (<0.01% positives). A model with a 0.95 AUC-ROC may score only 0.30 AUC-PR, showing practical limits [44]. IEEE-CIS fraud winners prioritized AUC-PR over ROC consistently [32,87].

Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC):

MCC balances TP, TN, FP, and FN in a (−1, 1) range [1,21]. A 0.60 MCC cut USD 8M false claims despite only 85% accuracy in healthcare fraud [113]. Stronger than accuracy for imbalanced data, though heavy in computation [21].

G-Mean:

G-Mean = √ (recall × specificity), balancing fraud detection and legitimate protection [63,86]. Insurance fraud systems using G-Mean achieve 15% better recovery–retention trade-off [88]. FL adaptations weight G-Mean by institution to balance fairness.

Cohen’s Kappa:

Kappa measures agreement beyond chance, 0.6–0.8 = strong reliability [17,60]. Stricter than accuracy under rare fraud (<5%) [67]. EU fintechs require κ ≥ 0.75 for GDPR-compliant deployment [17].

Balanced Accuracy:

Balanced Accuracy = (recall + specificity)/2, a simple imbalance-adjusted metric [3] Easier to explain than G-Mean, often used in executive reporting. Fraud APIs apply balanced accuracy (≈92%) for auto-scaling during traffic spikes [53,114].

Detection Prevalence = (TP + FP)/total, monitoring alert volume [31,59]. Banks target 1–3% prevalence; Amazon cut it from 5% → 1.2%, saving USD 20M/year [96]. High prevalence (>5%) indicates drift and retraining needed [59].

Positive Predictive Value (PPV):

Equivalent to precision, critical in costly fraud checks [6,55]. Crypto exchanges require ≥95% PPV to avoid wasteful blockchain investigations [115]. PPV varies by channel (80% card-not-present vs. 30% cross-border) [6].

Negative Predictive Value (NPV):

NPV = TN/(TN + FN), ensuring genuine approvals [9,21]. Gateways achieve >99.9% NPV with cascade models [116]. NPV decline often signals system drift weeks before accuracy drops [21].

Youden’s J Index:

J = recall + specificity − 1, balancing missed fraud vs. false alerts [33,84]. Medicare fraud detection saw 12% more recovery using J over 0.5 cutoff [120]. Useful for cross-model comparisons [33].

Lift Score:

Measures improvement over random detection; fraud systems need 5–10× lift [17,59]. E-commerce uses lift to calibrate rules, e.g., blocking Nigerian IPs gave 15× lift with 0.1% FP [74]. Lift decays over time, requiring monthly recalibration [59].

Cost-sensitive Accuracy:

Weighted accuracy (w1 × TN + w2 × TP) aligns metrics with financial impact [3,114]. Example: w2 = 10 prioritizing fraud detection gives 85% cost-sensitive vs. 95% raw accuracy [118]. Poor FP weighting caused 20% attrition at PayPal in 2019 [114].

Expected Cost:

Estimates fraud detection cost trade-offs in USD terms [30,101]. JPMorgan saved USD 43M by weighing FN cost 5× FP cost [110]. Misestimating FN cost by 300% caused USD 8M of losses in insurance [101]. Used for threshold tuning, Basel III compliance, and RL-based adaptive systems [82,110].

Developers of fraud detection systems can extensively evaluate performance in a variety of areas, from vital classification accuracy to expected cost efficacy, thanks to this extensive array of assessment indicators in section RQ2. Which metrics offer the most valuable insights for system optimization and deployment decisions is largely dependent on the particular application context with elements such as class imbalance and error cost asymmetry as well as operational requirements all playing a role.

RQ3: What are the different types of financial fraudulent transactions covered in the literature review?

This section tries to answer RQ3 by presenting different fraudulent activities that were addressed in this literature review. Based on the reviewed articles, the fraudulent activities in the financial sector can be broadly categorized into credit card fraud, financial statement fraud, bitcoin [105] and cryptocurrency, insurance fraud, online payments, etc. This can be further explained in the following subsections. The different types of financial fraudulent transactions are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Different types of financial fraudulent transactions.

As technology has advanced, the landscape of fraudulent activity has changed dramatically, creating difficult problems for detection systems. The main categories of fraud are identified and categorized in this systematic study according to their operational traits, detection challenges, and pertinent academic research, as shown in Table 5.

Credit Card Fraud:

Credit card fraud remains widespread, involving phishing, skimming, and online misuse [3,59]. Challenges include extreme class imbalance (less than 0.1% fraud) and the need for real-time detection [5,9]. Balancing false positives and false negatives is critical [31,59]. Federated learning with blockchain supports secure cross-bank detection [34,62,68]. LSTM networks capture sequential transaction patterns effectively [6,114].

Financial Statement Fraud:

This involves accounting manipulation and earnings misreporting [23,30]. Few confirmed cases and scarce labeled data hinder ML detection [121]. Both ratios and governance quality must be analyzed [130]. NLP detects misleading language in reports [30]. Progress depends on richer datasets and institutional collaboration [121].

Cryptocurrency Fraud:

Common forms include exchange hacks, wash trading, and flash loan exploits [59,109,113,122]. Challenges are irreversible transactions, pseudonymity, and evolving attacks [109]. GNNs help detect suspicious subgraphs in blockchain networks [24,59]. Ongoing research tackles validator collusion and cross-chain risks [122].

Insurance Fraud:

Frequent in healthcare and auto sectors, involving upcoding, fake treatments, or staged accidents [7,87,114,127]. Systems must process large, varied claims while allowing genuine variations [111]. Auto fraud requires image and estimates analysis [61,143,144,145,146]. Multimodal DL aids unstructured/structured data processing while ensuring explainability [87,127].

Online Payment Fraud:

Includes account takeover, merchant fraud, and chargeback abuse [34,68,117,123]. Detection must balance user experience with security [70]. Device fingerprinting and biometrics assist but raise privacy concerns [123,147]. FL offers privacy-preserving detection across platforms [68].

Identity Theft:

Ranges from impersonation to synthetic identities [125,126]. Challenges include linking cross-institution data, hidden “sleep periods,” and breach-driven data leaks [96,125]. Graph-based anomaly detection identifies hidden identity ties [126]. Privacy-preserving cross-bank data sharing would improve detection [124,148].

Healthcare Fraud:

Involves phantom billing, kickbacks, and unbundling [28,114,127]. Systems must analyze both clinical notes and structured claims [52]. Hybrid unsupervised + supervised methods detect new fraud [111]. Explainable AI is vital for regulatory compliance [127].

Tax Fraud:

Covers corporate evasion and false deductions [11,121]. Few labeled cases and global complexity pose detection issues [128]. Anomaly detection and network analysis reveal suspicious filing patterns [11]. NLP helps analyze narratives and verify deductions [121].

E-Commerce Fraud:

Includes fake reviews, non-delivery, and triangulation schemes [24,33]. Detecting cross-border scams and transient fraud is difficult [35]. Multimodal methods combine seller graphs, product images, and NLP [24]. To establish a healthy e-commerce ecosystem, robust cybersecurity and antifraud measures are important [129].

Mortgage Fraud:

Involves falsified assets, income, or flipping schemes [10,130]. Long loan cycles and collusion complicate detection [108]. AI assists with document verification and anomaly detection [130]. Privacy-preserving cross-lender data sharing is needed [10].

Employment Fraud:

Ghost employees and credential falsification are common. Detection is limited by poor verification and insider collusion. Blockchain aids credential authentication, while anomaly detection flags payroll fraud. Remote work raises new risks [112,131].

Telecom Fraud:

Includes IRSF and subscription fraud. Fast onboarding demands real-time detection [134]. Device fingerprinting and behavior analytics detect fraud but attackers evolve with VoIP and burners. FL helps cross-carrier fraud detection with privacy [132,133].

Social Media Fraud:

Covers influencer scams, fake followers, and impersonation [59,109]. Bots mimic human behavior, complicating detection. Current methods combine network, content, and behavioral analysis [89]. The fraudsters’ adaptability remains a challenge.

Public Sector Fraud:

Includes procurement, benefits, and grant misuse. Challenges are political sensitivity, fragmented oversight, and data complexity [27]. Network and anomaly analysis reveal suspicious spending. Balancing fraud detection with bureaucratic processes is essential [136].

Supply Chain Fraud:

Global networks and document fraud complicate detection and detecting such fraud is difficult because of multiparty coordination gaps [138]. Semi-supervised approaches show promise for supply chain applications where labeled data is scarce [137].

Investment Fraud:

Includes pump-and-dump and boiler-room schemes [73,113]. Difficulties include market volatility and multi-platform scams. Detection uses social media monitoring and SEC data [73]. Stronger integration of communication and market analysis is needed [122,149].

Academic Fraud:

Encompasses plagiarism, fake degrees, and paper mills. Complex paraphrasing and lack of shared verification hinder detection. NLP and citation analysis are common tools. Shared academic databases would strengthen prevention [139,140].

AI/ML System Fraud:

Targets fraud detection systems themselves through data poisoning or adversarial attacks. Detecting tainted training data is difficult [78]. Robust ML and anomaly detection in model behavior show promise. The arms race nature requires ongoing research [14,141,150].

Charity Fraud:

Exploits disasters or misuses funds. Emotional giving and reputational risks make detection delicate [27]. Network and flow analysis track suspicious activity [27,57]. Stronger donor transparency frameworks are needed.

Rental Fraud:

Includes phantom rentals and fake deposits [24]. Detecting duplicate listings

and ownership fraud is difficult [135]. Image and geospatial analysis aid

detection [24].

A tabulated breakdown of fraud categories and publication counts is provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Fraud types with the total no. of papers.

RQ4: How do blockchain-based federated learning and machine learning approaches differ in detecting financial frauds?

Fraud detection systems that can balance accuracy, privacy, and scalability are required due to the financial services industry’s fast digitization. This section provides a comparison framework for choosing the best approach in financial fraud detection by analyzing the main distinctions between these methods, as in Table 7, in terms of data handling, privacy protection, computational efficiency, regulatory compliance, and real-world applicability.

Table 7.

Federated learning and machine learning approaches.

Data Handling and Privacy:

FL keeps raw data on local devices, sharing only model updates over blockchain, reducing breach risks by 60–75% compared to centralized ML [6,56,68,78,152]. Privacy is reinforced with homomorphic encryption and differential privacy (ε = 0.5–5) [77,78]. Centralized ML requires large repositories, creating single points of failure and heavy compliance needs under GDPR [100,151].

Security and Scalability:

FL with blockchain provides tamper-proof updates via hashing and consensus, detecting poisoning attacks early [14,18,41,153]. Optimizations like sharding and BFT boost throughput to 2k–5k TPS [53,156]. Centralized ML avoids consensus costs but scales poorly, often needing 30–50% more storage/computation for equal datasets [60,73]. FL has scaled to 100+ institutions with sub-second fraud detection [53].

Regulatory Compliance and Model Performance:

FL aligns with GDPR and data localization, cutting compliance costs by 40–60% [27,136]. Smart contracts speed “right to be forgotten” requests from weeks to 2–3 days [27]. Centralized ML benefits from global data access and faster convergence but risks privacy. FL lags 5–15% in accuracy with non-IID data, though FedAvg/FedProx reduce this gap to 2–7% [42,158,160].

Use Cases and Fraud Detection:

FL excels in multi-bank collaboration, detecting 15–20% more novel frauds but with 100–300 ms latency [8,34,40,70]. ML dominates in single-bank, high-throughput scenarios with 50–100 ms latency [3,60]. Hybrid use in healthcare shows ML achieving 93–95% accuracy on claims, while FL secures 88–92% across hospitals [20,111].

Incentives and Transparency:

Blockchain-based incentives reward nodes for quality updates, ensuring sustained FL participation [132,161]. Immutable audit trails provide fairness and accountability [29,162,173,174,175,176,177]. Zero-knowledge proof enhances explainability [71,96]. Centralized ML depends on agreements and lacks decentralized transparency, making dataset bias harder to trace [18,41].

Latency and Resource Efficiency:

FL incurs 200–500 ms latency from aggregation and consensus [133,163]. Edge computing reduces delay but adds blockchain energy costs (PoW/PoS) [28,134]. ML achieves <100 ms latency, critical for instant fraud detection [34,70]. FL lowers storage needs but raises blockchain overhead, while centralized ML requires costly, large-scale servers [53,103].

Adversarial Robustness and Interoperability:

FL resists poisoning since multiple nodes must be compromised, with DP boosting resilience [167,168,169,170,171]. Centralized ML is more exposed to inversion/evasion attacks [14,155]. Frameworks like FATE and OpenFL enable cross-institution FL [140,151], while ML models often need proprietary APIs to integrate [26,36].

Auditing and Cost:

FL automates compliance via blockchain smart contracts, reducing fraud detection compliance costs by 20–30% [27,172]. Centralized ML requires manual audits, raising costs [96]. FL cuts storage expenses but adds blockchain fees [60,132]. ML incurs high upfront server costs and scales poorly with data [53,103].

Adoption Trends:

FL is growing in cross-bank fraud detection, cutting false positives by 25–40% [40,68]. In healthcare, FL boosted anomaly detection by 30% across 50+ institutions [20]. ML still dominates credit card fraud, covering 80% of global transactions [24,59]. Hybrids combining FL (privacy) and ML (real-time) reach 90–93% accuracy and reduce compliance costs by 35% [103,112]. FL adoption in finance is projected to grow 300% by 2025 [40,53].

3. Results

In this section, we present the results of the 1585 studies that met our inclusion and quality assessment criteria. We included only those studies that satisfied our rigorous selection standards and were not flagged for bias during the screening process. Once studies passed our inclusion criteria and underwent thorough coding and analysis, we did not conduct further bias assessments on their internal findings. Our analysis was based on quantitative summary statistics and qualitative thematic summaries derived from these high-quality studies.

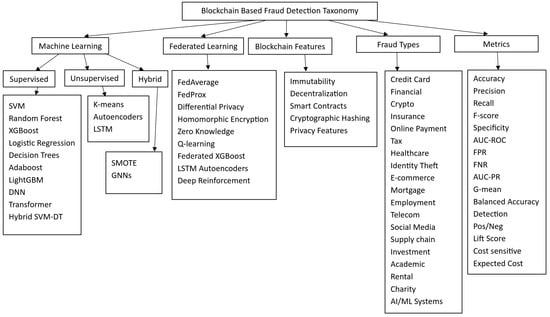

The taxonomy presented in Figure 2 systematically organizes the key components of blockchain-based fraud detection systems into three main categories: machine learning techniques, federated learning frameworks, and blockchain features.

Figure 2.

Taxonomy of blockchain-based fraud detection.

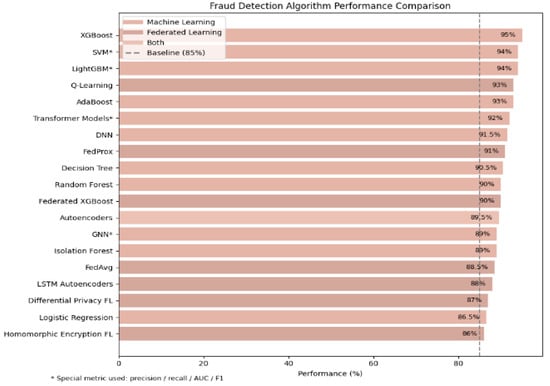

Figure 3 presents a comparative analysis of fraud detection algorithm performance across three methodological ML, FL, and hybrid approaches. The results demonstrate that XGboost [6,59,67] achieves the highest performance at 95% when combining ML and FL paradigms, underscoring its effectiveness in handling structured financial data while accommodating privacy-preserving requirements. This review is methodological and does not present experimental benchmarking; future work should empirically evaluate cross-framework performance.

Figure 3.

Bar chart of all algorithms.

This comparative framework informs the selection of algorithms based on operational priorities of performance versus privacy in blockchain fraud detection systems.

4. Discussion

Comparative analysis reveals that while centralized machine learning models such as XGBoost, SVM, and Random Forest excel in achieving higher accuracy (93–95%) on structured and labeled datasets, they remain limited by privacy and compliance constraints. Federated learning (FL) and its blockchain-enhanced variants achieve slightly lower accuracy (85–92%) but ensure secure, cross-institutional collaboration without raw data exchange. Integrating blockchain consensus mechanisms with FL strengthens traceability and robustness against poisoning attacks [68].

The recent literature emphasizes the need to balance performance with privacy. It is stressed that hybrid systems combining FL with blockchain can better manage data silos and regulatory diversity, aligning with real-world multi-bank use cases.

In practical terms, FL-based systems show a 25–40% reduction in false positives, especially when enhanced by blockchain audit trails and token-based incentives [20,40]. However, computational overhead and communication latency remain challenges [89]. This review identifies three emerging research needs: (1) lightweight consensus algorithms to improve scalability, (2) adaptive aggregation to handle non-IID data, and (3) explainable federated architectures for transparent financial regulation compliance. Addressing these issues will accelerate the adoption of blockchain–FL frameworks in enterprise fraud analytics.

When you compare them, XGBoost and similar machine learning methods perform better at finding fraud in organized data than older models. For example, SVM scores 94%, and RF scores between 0.95 and 0.97 on the AUC-ROC scale. Methods that are not supervised, like LSTM autoencoders (88%) and Isolation Forest (89%), are great at spotting unusual activity, but they need some adjustments to work well. Federated learning (with 85–92% accuracy) keeps data private and allows different groups to work together. While it does have some delays because of communication needs, federated XGBoost (90%) is a good mix of both. Usually, experts check how well these systems work by looking at precision, recall, and the F1-score. Just using accuracy can be misleading when the data is not balanced. Because of this, options like AUC-ROC/PR and measures that consider the cost of mistakes are becoming more useful in banking.

Most studies look at credit card fraud and fraud in financial statements (10 studies each). But there is also more interest in finding fraud related to cryptocurrency and insurance, since each has its own special problems [26,44,48,99,107]. Comparisons show that machine learning is more accurate and faster (under 100 ms). On the other hand, federated learning with blockchain offers privacy, follows GDPR rules, is easy to check, and is tough to break, but it is slower. Systems that mix blockchain and federated learning cut down on false positives, which seems like a good way to go in the future. Some big problems still exist, like dealing with data that is not consistent, making blockchain bigger, and protecting against attacks. This means there is room to develop things like adaptive aggregation, sharding, and AI that can explain itself better in fraud detection research.

Proposed Theoretical Framework for Blockchain-Based Federated Learning Fraud Detection

The proposed theoretical framework by the authors integrates blockchain’s decentralized consensus with federated learning’s privacy-preserving model aggregation to address current limitations in fraud detection research. As outlined, blockchain-enabled FL systems establish a verifiable architecture where transaction data remains local and only encrypted model parameters are exchanged across participants. This structure mitigates data leakage risks, ensures auditability, and supports GDPR compliance. This architecture can be deployed using permissioned blockchains such as Hyperledger Fabric or Ethereum PoA networks to ensure auditability and throughput. Our framework extends this concept by incorporating adaptive differential privacy and fairness-aware aggregation to balance data heterogeneity across financial institutions. This approach directly addresses the observed literature gaps related to privacy, scalability, and a conceptual foundation guiding future empirical studies. The comparison is explained with the help of Table 8.

Table 8.

Comparison of ML, FL, and hybrid blockchain–FL.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the review underscores that no single approach dominates fraud detection; instead, the choice between ML, FL, or hybrid models depends on operational priorities:

- Centralized ML for high-speed, single-organization fraud detection.

- FL-blockchain for privacy-preserving, cross-institutional collaboration.

- Hybrid systems for balancing real-time performance with security.

Future advancements in differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, and lightweight consensus algorithms will further enhance blockchain-based fraud detection systems, making them more scalable and resilient.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F., S.Z. and A.A.S.; methodology, H.F., S.Z., A.A.S. and N.A.; software, Z.U.R.; validation, H.F., S.Z., and Z.U.R.; formal analysis, A.A.S., and N.A.; investigation, S.Z.; resources, N.A.; data curation, Z.U.R. and N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.S. and N.A.; writing—review and editing, H.F. and S.Z.; visualization, Z.U.R.; supervision, Z.U.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at the Northern Border University, Arar, KSA, for their contribution in funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-1584-02”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jeragh, M.; Alsulaimi, M. Combining Auto Encoders and One Class Support Vectors Machine for Fraudulant Credit Card Transactions Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 Second World Conference on Smart Trends in Systems, Security and Sustainability (WorldS4), London, UK, 30–31 October 2018; pp. 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- West, J.; Bhattacharya, M. Some experimental issues in financial fraud mining. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 80, 1734–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Jha, S.; Tharakunnel, K.; Westland, J.C. Data mining for credit card fraud: A comparative study. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareeswari, V.; Gunasekaran, G. Prevention of credit card fraud detection based on HSVM. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Information Communication and Embedded Systems (ICICES), Chennai, India, 25–26 February 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A.; Yadav, M.; Basu, S.; Salunkhe, S.; Shabad, M. Credit card fraud detection at merchant side using neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 16–18 March 2016; pp. 667–670. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Pozzolo, A.; Boracchi, G.; Caelen, O.; Alippi, C.; Bontempi, G. Credit card fraud detection: A realistic modeling and a novel learning strategy. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 29, 3784–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirlidog, M.; Asuk, C. A Fraud Detection Approach with Data Mining in Health Insurance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 62, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Survey on categorical data for neural networks. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, J.R.D.; Vea, L.A. Credit card fraud detection based on transaction behavior. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2017-2017 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Penang, Malaysia, 5–8 November 2017; pp. 1880–1884. [Google Scholar]

- HaratiNik, M.R.; Akrami, M.; Khadivi, S.; Shajari, M. FUZZGY: A hybrid model for credit card fraud detection. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Telecommunications (IST), Tehran, Iran, 6–8 November 2012; pp. 1088–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Gutierrez, D.M.; Falkouskaya, Y.; Hernandez-Ramos, J.L.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Chatzigiannakis, I.; Vitaletti, A. On the Security and Privacy of Federated Learning: A Survey with Attacks, Defenses, Frameworks, Applications, and Future Directions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qammar, A.; Karim, A.; Ning, H.; Ding, J. Securing Federated Learning with Blockchain: A Systematic Literature Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 3951–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Xu, K.; Huang, Y.; Yu, F.; Wang, X. Privacy-Enhanced Data Fusion for Federated Learning Empowered Internet of Things. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 3850246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xu, X.; Wang, W. Threats attacks and defenses to federated learning: Issues taxonomy and perspectives. Cybersecurity 2022, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Wu, D.; Cai, T.; Zhu, Y.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Tang, Z.; Li, Y. Deep learning model inversion attacks and defenses: A comprehensive survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, L.; Song, C.; De Cristofaro, E.; Shmatikov, V. Inference attacks against collaborative learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.04049. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, H.A.M.; Shah, A.A.; Muhammad, A.; Kananah, A.; Aslam, A. Resolving Security Issues in the IoT Using Blockchain. Electronics 2022, 11, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhoseny, M.; Haseeb, K.; Shah, A.A.; Ahmad, I.; Jan, Z.; Alghamdi, M.I. IoT Solution for AI-Enabled PRIVACY-PREServing with Big Data Transferring: An Application for Healthcare Using Blockchain. Energies 2021, 14, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Gao, L.; Luan, T.H.; Xiang, Y.; Yu, S.; Li, B.; Zheng, G. Decentralized Privacy Using Blockchain-Enabled Federated Learning in Fog Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 5171–5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, T.; Haseeb, K.; Shah, A.A.; Rehman, A.; Tariq, U.; Mehmood, Z. A Machine-Learning-Based Approach for Autonomous IoT Security. IT Prof. 2021, 23, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Ghorpade, C. Credit Card Fraud Detection on the Skewed Data Using Various Classification and Ensemble Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS), Bhopal, India, 24–25 February 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (PMLR), Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Ravisankar, P.; Ravi, V.; Rao, G.R.; Bose, I. Detection of financial statement fraud and feature selection using data mining techniques. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baabdullah, T.; Alzahrani, A.; Rawat, D.B.; Liu, C. Efficiency of federated learning and blockchain in preserving privacy and enhancing the performance of credit card fraud detection (CCFD) systems. Future Internet 2024, 16, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Meese, C.; Li, W.; Shen, C.-C.; Nejad, M. B²SFL: A Bi-Level Blockchained Architecture for Secure Federated Learning-Based Traffic Prediction. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2023, 16, 4360–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, H.B.; Ramage, D.; Talwar, K.; Zhang, L. Learning differentially private recurrent language models. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.06963. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, P.; Von dem Bussche, A. The eu general data protection regulation (gdpr). In A Practical Guide, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10, p. 10-5555. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Niyato, D.; Leung, C.; Miao, C. Optimizing task assignment for reliable blockchain-empowered federated edge learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 1910–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Li, C.; Josh, J. Blockchain-based transparency framework for privacy-preserving third-party services. IEEE Trans. Depend. Secur. Comput. 2023, 20, 2302–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.; Albrecht, C.; Vance, A.; Hansen, J. Metafraud: A meta-learning framework for detecting financial fraud. Mis Q. 2012, 36, 1293–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L. A financial statement fraud detection model based on hybrid data mining methods. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Big Data (ICAIBD), Chengdu, China, 26–28 May 2018; pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Singh, T.; Sinhal, A.; Khan, A.; Singh, T. Implement credit card fraudulent detection system using observation probabilistic in hidden Markov model. In Proceedings of the 2012 Nirma University International Conference on Engineering (NUiCONE), Ahmedabad, India, 6–8 December 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Emmott, A.F.; Das, S.; Dietterich, T.; Fern, A.; Wong, W.K. Systematic construction of anomaly detection benchmarks from real data. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD Workshop on Outlier Detection and Description, Chicago, IL, USA, 11 August 2013; pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, K.; Li, L.; Xu, C.Z. Ffd: A federated learning based method for credit card fraud detection. In International Conference on Big Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aurna, N.F.; Hossain, M.D.; Taenaka, Y.; Kadobayashi, Y. Federated Learning-Based Credit Card Fraud Detection: Performance Analysis with Sampling Methods and Deep Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR), Montreal, Canada, 27–29 June 2023; pp. 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Q.; Xu, M.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, X. A systematic survey of blockchained federated learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.02182. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Uddin, M.P.; Gan, C.; Xiang, Y.; Gao, L.; Yearwood, J. Blockchain-enabled federated learning: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, S.; Xuan, S. Decentralized Federated Learning Based on Blockchain: Concepts, Framework, and Challenges. Comput. Commun. 2024, 216, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lv, N.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y. Recent Advances on Federated Learning: A Systematic Survey. Neurocomputing 2024, 597, 128019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J. Co-Construction Scheme of Credit Risk Control Model for Small and Medium-Sized Banks Based on Federated Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 2nd International Conference on Digital Economy, Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence, Dalian, China, 1–21 November 2025; pp. 370–376. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, S.; Abdelmoniem, A.M.; Gill, S.S. Centralised and Decentralised Fraud Detection Approaches in Federated Learning. In Applications of AI for Interdisciplinary Research; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, NW, USA, 2024; p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Qu, Z.; Zeng, D.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Zomaya, A.Y. Adaptive Vertical Federated Learning on Unbalanced Features. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2022, 33, 4006–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhasawi, Y.; Almtrf, A.A.; Asad, M. A Federated Approach to Scalable and Trustworthy Financial Fraud Detection. Secur. Priv. 2025, 8, e70099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, N.; Wagner, D. Towards evaluating the robustness of neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–24 May 2017; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.M.; Fawzi, A.; Frossard, P. Deepfool: A simple and accurate method to fool deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2574–2582. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C. Adversarial examples: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 31, 2578–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Song, D. Delving into transferable adversarial examples and black-box attacks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1611.02770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Vargas, D.V.; Sakurai, K. One Pixel Attack for Fooling Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2019, 23, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; He, P.; Zhu, Q.; Li, X. Adversarial examples: Attacks and defenses for deep learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 2805–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramèr, F.; Kurakin, A.; Papernot, N.; Goodfellow, I.; Boneh, D.; McDaniel, P. Ensemble adversarial training: Attacks and defenses. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07204. [Google Scholar]

- Guembe, B.; Azeta, A.; Osamor, V.; Ekpo, R. Federated learning for decentralized anti-money laundering. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (ICBC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 4–7 May 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Moamen, A.A.; Jamali, N. An actor-based middleware for crowd-sourced services. ICST Trans. Mob. Commun. Appl. 2017, 3, e1. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, A.; Postolache, O.; Oliveira, S.; Pereira, J.D. Securing IoT Sensors Using Sharding-Based Blockchain Network Technology Integration: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapowicz, M.; Zbikowski, K. Detecting fraudulent accounts on blockchain: A supervised approach. In Web Information Systems Engineering–WISE 2019: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference, Hong Kong, China, 19–22 January 2020; Proceedings 20; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, P.; Das, D.; Rawat, D. Securing Financial Transactions: Exploring the Role of Federated Learning and Blockchain in Credit Card Fraud Detection. Authorea Prepr. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 2019, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundokun, R.O.; Misra, S.; Maskeliunas, R.; Damasevicius, R. A review on federated learning and machine learning approaches: Categorization, application areas, and blockchain technology. Information 2022, 13, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, I.; Mathai, K.J. Intelligent fraudulent detection system based SVM and optimized by danger theory. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Computer, Communication and Control (IC4), Indore, India, 10–12 September 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Stefánsson, H.P.; Grímsson, H.S.; Þórðarson, J.K.; Óskarsdóttir, M. Detecting Potential Money Laundering Addresses in the Bitcoin Blockchain Using Unsupervised Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the HICSS, Online, 4–7 January 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Randhawa, K.; Loo, C.K.; Seera, M.; Lim, C.P.; Nandi, A.K. Credit Card Fraud Detection Using AdaBoost and Majority Voting. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 14277–14284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subudhi, S.; Panigrahi, S. Effect of Class Imbalanceness in Detecting Automobile Insurance Fraud. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Data Science and Business Analytics (ICDSBA), Changsha, China, 21–23 September 2018; pp. 528–531. [Google Scholar]

- Ouadrhiri, A.E.; Abdelhadi, A. Differential Privacy for Deep and Federated Learning: A Survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 22359–22380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J. Credit card fraud detection based on unsupervised attentional anomaly detection network. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Shenzhen, China, 1–3 July 2019; pp. 146–148. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 2002, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madni, H.A.; Umer, R.M.; Foresti, G.L. Blockchain-based swarm learning for the mitigation of gradient leakage in federated learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 16549–16556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.K.; Liu, Y.; Nguyen, Q.M.; Liu, Q.; Liu, F.; Cai, Q.; Hirche, S. Fedxgboost: Privacy-preserving xgboost for federated learning. arXiv Prepr. 2021, arXiv:2106.10662. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Alabi, O.O. Secure and scalable blockchain-based federated learning for cryptocurrency fraud detection: A systematic review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 102219–102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wen, Z.; He, B. Practical federated gradient boosting decision trees. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 4642–4649. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, D.; Zou, Y.; Xiang, S.; Jiang, C. Graph Neural Networks for Real-Time Fraud Detection in Payment Networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 123456–123470. [Google Scholar]

- Effendi, F.; Chattopadhyay, A. Privacy-Preserving Graph-Based Machine Learning with Fully Homomorphic Encryption for Collaborative Anti-Money Laundering. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Security, Privacy, and Applied Cryptography Engineering, Kottayam, India, 14–17 December 2024; pp. 80–105. [Google Scholar]

- Shahsavari, Y.; Dambri, O.A.; Baseri, Y.; Hafid, A.S.; Makrakis, D. Integration of Federated Learning and Blockchain in Healthcare: A Tutorial. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2404.10092. [Google Scholar]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; Bellet, A.; Bennis, M.; Bhagoji, A.N.; Bonawitz, K.; Charles, Z.; Cormode, G.; Cummings, R.; et al. Advances and Open Problems in Federated Learning. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2021, 14, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truex, S.; Baracaldo, N.; Anwar, A.; Steinke, T.; Ludwig, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, Y. A hybrid approach to privacy-preserving federated learning. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM workshop on artificial intelligence and security, London, UK, 15 November 2019; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, W.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Su, C. Blockchain-Based Two-Stage Federated Learning with Non-IID Data in IoMT System. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 10, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Ding, M.; Pathirana, P.N.; Seneviratne, A.; Li, J.; Poor, H.V. Federated learning for internet of things: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1622–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Li, J.; Ding, M.; Ma, C.; Yang, H.H.; Farokhi, F.; Jin, S.; Quek, T.Q.S.; Poor, H.V. Federated Learning with Differential Privacy: Algorithms and Performance Analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 15, 3454–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitaj, B.; Ateniese, G.; Perez-Cruz, F. Deep models under the GAN: Information leakage from collaborative deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Dallas, TX, USA, 30 October 2017–3 November 2017; pp. 603–618. [Google Scholar]

- Skovajsova, L.; Hluchý, L.; Staňo, M. A Review of Multi-Objective and Multi-Task Federated Learning Approaches. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 23rd World Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI), Stará Lesná, Slovakia, 23–25 January 2025; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Okoroafor, N. An ML-powered risk assessment system for predicting prospective mass shooting. Computers 2023, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, S.; Gong, L. Combustion optimization study of pulverized coal boiler based on proximal policy optimization algorithm. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 254, 123857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, J.; Assael, I.A.; De Freitas, N.; Whiteson, S. Learning to Communicate with Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, arXiv:1605.06676. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, B.; Song, Q.; Min, M.R.; Cheng, W.; Lumezanu, C.; Cho, D.; Chen, H. Deep autoencoding gaussian mixture model for unsupervised anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.T.; Ting, K.M.; Zhou, Z.H. Isolation forest. In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Pisa, Italy, 15–19 December 2008; pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Bauder, R.; da Rosa, R.; Khoshgoftaar, T. Identifying Medicare Provider Fraud with Unsupervised Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration (IRI), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 7–9 July 2018; pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Alghushairy, O.; Alsini, R.; Soule, T.; Ma, X. A review of local outlier factor algorithms for outlier detection in big data streams. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2020, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbarasi, M.S.; Dhivya, S. Fraud detection using outlier predictor in health insurance data. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Information Communication and Embedded Systems (ICICES), Chennai, India, 23–24 February 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Salam, M.; Fouad, K.M.; Elbably, D.L.; Elsayed, S.M. Federated Learning Model for Credit Card Fraud Detection with Data Balancing Techniques. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 6231–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Tran, K.P.; Koehl, L.; Li, S. AnoFed: Adaptive anomaly detection for digital health using transformer-based federated learning and support vector data description. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 121, 106051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Razumovskaia, E.; Vulić, I.; Korhonen, A. Analyzing and adapting large language models for few-shot multilingual nlu: Are we there yet? Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2025, 13, 1096–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N.; Erez, T.; Tassa, Y.; Silver, D.; Wierstra, D. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Baracaldo, N.; Shaul, H.; Martineau, K.; Murphy, M.; Drucker, N.; Kadhe, S.; Ludwig, H. Federated Learning Meets Homomorphic Encryption. IBM Res. Blog 2023. Available online: https://research.ibm.com/blog/federated-learning-homomorphic-encryption?trk=public_post_main-feed-card_feed-article-content (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Madi, A.; Stan, O.; Mayoue, A.; Grivet-Sébert, A.; Gouy-Pailler, C.; Sirdey, R. A Secure Federated Learning Framework Using Homomorphic Encryption and Verifiable Computing. In Proceedings of the 2021 Reconciling Data Analytics, Automation, Privacy, and Security: A Big Data Challenge (RDAAPS), Montreal, Canada, 14–16 July 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Deng, X.; Pei, X.; Jiang, P.; Mushtaq, H. A Verifiable and Privacy-Preserving Blockchain-Based Federated Learning Approach. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2023, 16, 2256–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhu, L.; et al. Zero-Knowledge Proof-Based Verifiable Decentralized Machine Learning in Communication Network: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hard, A.; Rao, K.; Mathews, R.; Ramaswamy, S.; Beaufays, F.; Augenstein, S.; Eichner, H.; Kiddon, C.; Ramage, D. Federated learning for mobile keyboard prediction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.03604. [Google Scholar]

- Soydaner, D. Attention mechanism in neural networks: Where it comes and where it goes. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 13371–13385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.P.; Xiang, Y.; Hasan, M.; Bai, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L. A Systematic Literature Review of Robust Federated Learning: Issues, Solutions, and Future Research Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubaie, M.; Chang, J.M. Privacy-preserving machine learning: Threats and solutions. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2019, 17, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; You, M. The Health Care Fraud Detection Using the Pharmacopoeia Spectrum Tree and Neural Network Analytic Contribution Hierarchy Process. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA, Tianjin, China, 23–26 August 2016; pp. 2006–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, B.; Dong, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, J. Federated graph machine learning: A survey of concepts, techniques, and applications. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2022, 24, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M. Federated Learning Models for Privacy-Preserving AI In Enterprise Decision Systems. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Insights 2025, 5, 238–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Chen, X.; Deng, W. Homomorphic Encryption and Secure Aggregation Based Vertical-Horizontal Federated Learning for Flight Operation Data Sharing. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Seminar on Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Information Technology (AINIT), Nanjing, China, 29–31 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alowolodu, O.D. Ensemble Learning Approach to Fraud Detection in Cryptocurrency Blockchain. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2025, 186, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, N.; Bhavana, N.; Sindhu, T.H.; Harshitha, P.; Johny, U. Enhancing Financial Fraud Detection with Explainable AI and Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Technology Enabled Economic Changes (InTech), Shanghai, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 1181–1191. [Google Scholar]

- El Bouchti, A.; Chakroun, A.; Abbar, H.; Okar, C. Fraud detection in banking using deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 Seventh International Conference on Innovative Computing Technology (INTECH), Luton, UK, 16–18 August 2017; pp. 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, G.; Ohara, M.; Calomiris, C.W. Federated Learning for Real Time Fraud Detection in Decentralized Exchanges. Multidiscip. Stud. Innov. Res. 2021, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.F.M.S.S.; Karabulut, M.A.; Akhter, A.F.M.S.; Mustari, N.; Pathan, A.-S.K.; Rabie, K.M.; Shongwe, T. On the Vital Aspects and Characteristics of Cryptocurrency—A Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 9451–9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Irfan, M.M.; Bomai, A.; Zhao, C. Towards privacy-preserving deep learning: Opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 7th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6–9 October 2020; pp. 673–682. [Google Scholar]

- Cholakoska, A.; Pfitzner, B.; Gjoreski, H.; Rakovic, V.; Arnrich, B.; Kalendar, M. Differentially Private Federated Learning for Anomaly Detection in eHealth Networks. In Adjunct Proceedings of the 2021 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2021 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 514–518. [Google Scholar]

- Ojo, I.P.; Tomy, A. Explainable AI for credit card fraud detection: Bridging the gap between accuracy and interpretability. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 25, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoletti, M.; Pes, B.; Serusi, S. Data Mining for Detecting Bitcoin Ponzi Schemes. In Proceedings of the 2018 Crypto Valley Conference on Blockchain Technology (CVCBT), Zug, Switzerland, 20–22 June 2018; pp. 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chalapathy, R.; Chawla, S. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection: A Survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.03407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdasaryan, E.; Poursaeed, O.; Shmatikov, V. Differential Privacy Has Disparate Impact on Model Accuracy. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dwork, C.; Roth, A. The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy. Found. Trends® Theor. Comput. Sci. 2014, 9, 211–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, A.; Selvaraj, A.; Venkatachalam, D. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for Synthetic Financial Data Generation: Enhancing Risk Modeling and Fraud Detection in Banking and Insurance. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2022, 2, 230–269. [Google Scholar]

- Badriyah, T.; Rahmaniah, L.; Syarif, I. Nearest Neighbour and Statistics Method based for Detecting Fraud in Auto Insurance. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Applied Engineering (ICAE), Batam, Indonesia, 3–4 October 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; He, Y.; Chen, T.; Yang, Q. Self-Supervised Cross-Silo Federated Neural Architecture Search. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.11896. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, M.; Fang, X.; Du, B.; Yuen, P.C.; Tao, D. Heterogeneous federated learning: State-of-the-art and research challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, P.; Henriques, R. Mining corporate annual reports for intelligent detection of financial statement fraud—A comparative study of machine learning methods. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2017, 128, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.M.; Mahto, R.; Goel, K.; Das, A.; Kumar, P.; Saxena, A. Modified Genetic Algorithm with Deep Learning for Fraud Transactions of Ethereum Smart Contract. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Cheng, X. Blockchain and federated edge learning for privacy-preserving mobile crowdsensing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10(14), 12000–12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashatan, A.; Sangari, M.S.; Dehghani, M. How perceptions of information privacy and security impact consumer trust in crypto-payment: An empirical study. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 69441–69454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, M.; Mehedi, S.T.; Anwar, A.; Rahman, Z.; Islam, R. A systematic literature review on blockchain enabled federated learning framework for Internet of Vehicles. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecko, A.; Kajati, E.; Koziorek, J.; Zolotova, I. Federated learning for edge computing: A survey. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgapal, P.; Kataria, P.; Garg, G.; Anand, A.S. A comprehensive distributed framework for cross-silo federated learning using blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2023 Fifth International Conference on Blockchain Computing and Applications (BCCA), Kuwait, Kuwait, 24–26 October 2023; pp. 538–545. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A. A model and middleware for composable IoT services. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Internet Computing (ICOMP), Athens, Greece, 3–6 June 2019; pp. 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S.X.; Jiang, J.; Han, Z.; Yin, H. Fraud Detection in E-Commerce: A Systematic Review of Transaction Risk Prevention. In Anomaly Detection-Methods, Complexities and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Glancy, F.H.; Yadav, S.B. A computational model for financial reporting fraud detection. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalapaaking, A.P.; Khalil, I.; Rahman, M.S.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Yi, X.; Almashor, M. Blockchain-based federated learning with secure aggregation in trusted execution environment for Internet-of-Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2023, 19, 1703–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Q.; Li, R.; Xu, M.; Xiong, Z. Incentive mechanism design for joint resource allocation in blockchain-based federated learning. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2023, 34, 1536–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Hosseinalipour, S.; Love, D.J.; Pathirana, P.N.; Brinton, C.G. Latency Optimization for Blockchain-Empowered Federated Learning in Multi-Server Edge Computing. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 3373–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Sharma, P.; Gope, P.; Puthal, D. Blockchain and Federated Learning-Enabled Distributed Secure and Privacy-Preserving Computing Architecture for IoT Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), Genoa, Italy, 27–30 June 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, B.; Song, Y. Secure multi-party computing for financial sector based on blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 14th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), Beijing, China, 17–18 October 2023; pp. 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, J.P. How the GDPR will change the world. Eur. Data Prot. Law Rev. 2016, 2, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Ó.; Sánchez, P.; Alcaraz, E. A Review of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Fraud Detection Across Financial and Supply Chain Domains. Res. Sq. 2025, preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, E.; Zeng, L.; Luo, K.; Zhang, J. Edge intelligence: Paving the last mile of artificial intelligence with edge computing. Proc. IEEE 2019, 107, 1738–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Ahmad, T. Federated transfer learning: Concept and applications. Intell. Artif. 2021, 15, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, N.; Lyu, L.; Niyato, D.; Lam, K.-Y. Local differential privacy-based federated learning for internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 8836–8853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonawitz, K.; Ivanov, V.; Kreuter, B.; Marcedone, A.; McMahan, H.B.; Patel, S.; Ramage, D.; Segal, A.; Seth, K. Practical secure aggregation for privacy-preserving machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Dallas, TX, USA, 30 October–3 November 2017; pp. 1175–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qian, P.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; He, Q. Smart Contract Vulnerability Detection Using Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Yokohama, Japan, 19–27 August 2021; pp. 3283–3290. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9650–9660. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Younesi, A.; Ansari, M.; Fazli, M.; Ejlali, A.; Shafique, M.; Henkel, J. A comprehensive survey of convolutions in deep learning: Applications, challenges, and future trends. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 41180–41218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, G.; Zhang, X. Privacy-enhanced and verification-traceable aggregation for federated learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 24933–24948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Yang, Q. Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserving AI. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, O.; Pouriyeh, S.; Parizi, R.M.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Srivastava, G.; Zhao, L. Communication efficiency in federated learning: Achievements and challenges. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.10996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Beams, A.; Chatzigiannis, P.; Meiser, S.; Patel, K.; Raghuraman, S.; Rindal, P.; Shah, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; et al. Privacy-Preserving Financial Anomaly Detection via Federated Learning & Multi-Party Computation. In Proceedings of the 2024 Annual Computer Security Applications Conference Workshops (ACSAC Workshops), Austin, TX, USA, 9–13 December 2024; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, A.; White, T.; Dumoulin, V.; Arulkumaran, K.; Sengupta, B.; Bharath, A.A. Generative adversarial networks: An overview. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2018, 35, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]