Abstract

In high-mountain canyon areas, complex geological environments lead to frequent cascading disasters with unclear triggering mechanisms, posing severe threats to human life and property. Existing knowledge graph research in geology predominantly focuses on single-hazard types or general geological entities, lacking structured modeling and specialized datasets for cascading disaster processes, particularly the evolutionary chains in high-mountain canyon settings. To address this gap, this study proposes a method for constructing a knowledge graph tailored to cascading disasters in high-mountain canyon regions. First, a three-layer schema framework—comprising concept, relation, and instance layers—was designed to systematically characterize the knowledge elements and evolutionary relationships of disaster chains. To address the lack of a knowledge dataset for cascade disasters, this paper integrates multi-source heterogeneous data to construct a high-mountain canyon cascading disasters entity–relation dataset (DCER-MC), providing a reliable benchmark for related tasks. Based on this dataset, we implemented the knowledge graph and conducted disaster chain analysis. Experiments and applications demonstrate that the constructed knowledge graph effectively supports structured storage, centralized management, and scenario-based application of regional cascading disaster information. The main contributions of this work are (1) proposing a targeted schema framework for cascading-disaster knowledge graphs; (2) releasing a specialized dataset for cascading disasters in high-mountain canyon regions; and (3) establishing a complete pipeline from data to knowledge to scenario-based services, offering a novel knowledge-driven paradigm for disaster chain risk identification, inference prediction, and emergency decision-making in these areas.

1. Introduction

In recent years, influenced by climate change and human activities, the scale and frequency of geological disasters have intensified, making it increasingly urgent to study their causes and early-warning mechanisms. Such disasters are highly destructive and often trigger secondary hazards, forming cascading disasters [1].

The high-altitude canyon region features complex topography, active geological structures, and a fragile ecological environment, making it highly susceptible to cascading disasters; thus monitoring and prevention are particularly important [2,3]. At present, researchers have accumulated a large amount of multi-source geological data, but traditional databases have significant shortcomings—such as difficulty in cross-domain associative analysis, multiple definitions for the same disaster type, and historical data containing irrelevant information—which seriously affect data management [4,5,6,7]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for an effective method to integrate and streamline the data.

The emergence of knowledge graphs has offered a new solution to this problem [8]. In 1956, Richens proposed semantic networks, which became the origin of graphical knowledge representation [9]; in 1959, symbolic logic knowledge began to be used for reasoning and problem solving with the advent of general problem solvers [10]. Thereafter, the human knowledge representation community explored various formalisms, and Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation (MCC) launched the Cyc project aiming to encode knowledge in a machine-usable form. Subsequently, RDF and OWL became important standards for the Semantic Web and promoted the creation of numerous knowledge bases. In 1988, Stokman and Vries proposed modern ideas about structural knowledge in graphs, laying the foundation for graph structures [11]. To date, various knowledge graphs have been constructed, including encyclopedic knowledge graphs (such as YAGO and Freebase), lexical/semantic knowledge graphs (such as WordNet and ConceptNet), and commonsense knowledge graphs [12,13,14,15]. Domain-specific professional knowledge graphs have also emerged, focusing primarily on particular fields. Currently, knowledge graphs are widely applied in medicine, agriculture, ecology, and other domains [16,17,18]. In geosciences and disaster fields, they have numerous applications; knowledge graphs connect disaster processes to geoscientific environments, enabling cross-domain integration [19,20,21].

In recent years, deep learning technology has been widely applied in the field of natural language processing (NLP), which has significantly advanced the evolution of knowledge graph construction technology. In basic tasks, deep neural network models have achieved excellent performance in tasks such as named entity recognition [22], entity classification [23], entity linking [24], anaphora resolution, and relation extraction. In addition, deep knowledge representation models for refining knowledge graphs have also been developed. These models include completing tuples, which discover new tuples within a constructed knowledge graph through an internal graph structure, and merging knowledge graphs from different sources to build new knowledge graphs.

Research on chain disasters is closely related to geoscientific knowledge; the locations where disasters occur and the objects they affect all involve geoscience content. Zhou Chenghu examined the research of geoscience knowledge graphs in the era of big data, and Duan Yuxi proposed a framework for the representation of geological map knowledge that converts geological map information into knowledge graph form [25]. Xie Xuejing and others combined BERT with a BiGRU-Attention-CRF model to propose a geological named entity recognition method [26]. Qiu Qinjun et al., addressing challenges in constructing geological knowledge graphs such as inconsistent data structures, quality issues, balancing scale and quality and update delays, proposed a unified geological ontology representation model that integrates the “semantic concept layer—change mechanism layer—feature attribute layer” and constructed an iterative knowledge graph building framework based on expert crowd-intelligence collaboration to meet the needs for large-scale, high-quality, and efficient construction [27]. Existing studies have not yet summarized chain disasters in the high mountain canyon regions into a knowledge graph.

In terms of the construction of a disaster knowledge graph, Xie Yanhong and other scholars have proposed a knowledge graph construction method for earthquake disaster prevention and control, which improves the ease of use and operability of the earthquake disaster prevention and mitigation information service system, and solves the problem that the relevant service information is difficult to popularize and apply [28]. Xu Qiang et al. proposed a landslide knowledge graph construction method for the field of engineering geology, which is related to other disciplines, promotes the deep intersection and integration of disciplines, and provides reference for other types of disaster knowledge graph research [29]. Qiu Qinjun innovatively proposed a knowledge graph construction method of geological disaster chains designed for disaster emergency response scenarios. This method successfully opened up the transformation path from original data to structured information and then to deep knowledge, which provided a technical framework and practical paradigm for the systematic construction of knowledge graph in the field of geological disaster prevention and control [30]. Lu et al. constructed a knowledge map of the typhoon disaster chain, and established a risk assessment model of the typhoon disaster chain based on Bayesian network [31]. At present, geological disaster data show the characteristics of multi-source heterogeneity, and the types of disasters are also rich and diverse. However, in the field of research on the spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of geological disaster chains, the existing research has failed to systematically analyze the complex correlation network between geological disasters and core elements such as geological environment background and geospatial entities.

This paper focuses on strategies for constructing a knowledge graph of cascading disasters in high-mountain canyon regions, centering on earthquake- and rainfall-induced cascading disasters. It investigates efficient representation mechanisms at the schema layer with the aim of extracting, representing, and storing information on cascading disasters from multi-source heterogeneous data, thereby enabling the transformation from raw data to deeper knowledge. Through knowledge-driven entity relational inference techniques, it seeks to build a knowledge graph system that intuitively presents complex relationships and facilitates retrieval. The research content includes: constructing the schema layer to restore cascading-disaster elements, build abstract concepts, and extract internal relations to provide a framework for the data layer; constructing the data layer by collecting and preprocessing textual data, annotating data, and building an entity–relation dataset; constructing and applying the knowledge graph by integrating multiple types of data for knowledge fusion, storing it in a graph database, enabling visualization and knowledge search, and ultimately building event-specific cascading-disaster knowledge graphs for particular times and locations.

2. Construction Process of a Cascading Disaster Knowledge Graph

2.1. Concept and System of Cascading Disasters

Cascading disasters are a series of secondary or derivative disasters triggered by a primary disaster (such as earthquakes or heavy rain), forming a chain with causal relationships. These disasters exhibit diverse types and complex combinations, featuring significant chain reaction characteristics. This leads to continuously expanding disaster losses and affected areas, severely threatening human life, property safety, and social stability [32,33]. The core of this disaster system lies in revealing the coupling mechanism of “disaster-causing environment–disaster-inducing factor–disaster entity–chain effect.” A complete understanding of this mechanism requires integrating various factors such as the disaster’s geological environment, disaster attributes, and impact consequences, constructing a hierarchical knowledge framework of “conceptual layer–relational layer–instance layer” to support the intelligent prediction and risk prevention system of cascading disaster.

2.2. Basic Process of Constructing a Knowledge Graph for Cascading Disasters

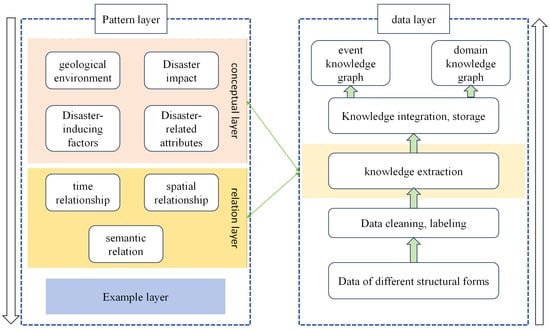

Building a knowledge graph requires extracting machine-understandable knowledge from massive, complex, and structurally diverse data, encompassing multiple stages such as knowledge modeling, extraction, fusion, and storage management; it is a complex systems engineering task [34]. A knowledge graph consists of a schema layer and a data layer: the former is the conceptual model and logical foundation that constrains and standardizes the latter [35]; the latter is the concrete manifestation and instance-level representation of the former. There are two primary approaches to constructing knowledge graphs: bottom-up, which automatically derives entities and relations from data to form the data layer and then generalizes to build the schema layer; and top-down, which first constructs the schema layer and then refines and supplements entities and relations to build the data layer. General-purpose knowledge graphs, due to their broad scope, large information scale, and tolerance for some error, commonly adopt the bottom-up approach; domain-specific knowledge graphs, which emphasize professional depth and precision, more often use the top-down approach. The top-down approach can reveal hierarchical conceptual relationships but requires substantial human resources and time and lacks automated updating capability; the bottom-up approach has clear advantages in update speed and processing large volumes of data, but when used alone it may produce a schema layer that is incomplete, imprecise, and nonstandard. Therefore, combining both approaches can complement their respective strengths. This work adopts a combined approach to construct the knowledge graph, ensuring the comprehensiveness, accuracy, and standardization of the cascading disaster knowledge graph while accommodating the needs for big data processing and rapid updates. Figure 1 illustrates the construction process of the cascading-disaster knowledge graph presented in this paper.

Figure 1.

Chain Disaster Knowledge Graph for High Mountain Canyon Areas Construction Process.

3. Construction of the Model Layer of Chain-Generated Disasters Knowledge Graph in High Mountain and Canyon Areas

3.1. Conceptual Layer of the Knowledge Graph of Chain-Generated Disasters in High Mountain and Canyon Areas

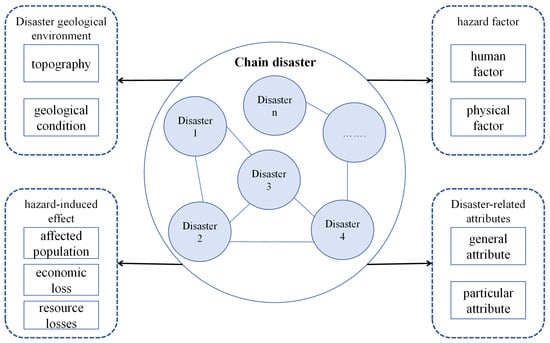

Chain-generated disasters typically manifest as the simultaneous or sequential occurrence of multiple disasters, with significant mutual influences and correlations among different disasters. The construction of evolutionary relationships between disasters is the key to the study of cascading disasters. Thus, the design of conceptual layer in this section focuses on sorting out and modeling relevant concepts within the disaster context. systematically clarifying the core concepts and elemental relationships within each disaster type. By systematically clarifying the core concepts and elemental relationships within each disaster type, we lay the foundation for constructing a comprehensive conceptual system of chain disasters, enabling a clear expression of the overall knowledge structure of disaster chains. Figure 2 presents the conceptual system of chain-generated disaster knowledge. Chain-generated disasters has a correlation, and each disaster possesses its own unique knowledge concept. This thesis divides the concept of single disaster into four aspects: disaster geological environment, disaster impact, disaster-causing factors, and disaster-related attributes.

Figure 2.

Concept classification of chain-generated disasters in high mountain and canyon areas.

3.2. Relational Layer of the Knowledge Graph of Chain-Generated Disasters in High Mountain and Canyon Areas

Model layer of chain-generated disaster knowledge graph should include a set of concept nodes and a set of concept relationships. And it illustrates the construction and condensation of the knowledge system related to chain disasters, but it does not specify the connections between the knowledge elements. Therefore, we construct the relationship set of the pattern layer combining the spatiotemporal characteristics among disasters. The relational layer of the knowledge graph for cascading disasters is categorized into temporal relationships, spatial relationships, and semantic relationships.

3.2.1. Time Relationship of Chain-Generated Disasters

In the occurrence of chain-generated disasters, the time factor permeates through all stages: before, during, and after the disaster. As shown in Table 1:Time information can clearly depict the sequential order of different disaster events, which contribute the judgment of whether there is a causal connection or mutual influence between disasters. It serves as a crucial basis for constructing chain relationships and analyzing the propagation paths of disasters. Temporal relationships primarily encompass time points and time slots. Time points denote the specific moments when events occur, such as the commencement and cessation of a disaster or rainfall. Time slots represent the span of time during which an event takes place, like the duration from the initiation to the conclusion of a landslide or debris flow [36]. Due to the complex interconnections among chain disasters, time periods can better reflect their connections, for example, when two disasters occur simultaneously, when one disaster suddenly occurs during the occurrence of another disaster, or when one disaster follows closely after another. The 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, for instance, immediately triggered landslides and collapses, weakening the mountain mass. Subsequently, due to weathering and rainfall, further landslides and debris flows occurred. Assuming that the time periods of two events are A and B, respectively, and that A occurs before or at the same time as B, the temporal relationship can be described as follows.

Table 1.

Temporal Relationships in Chain-Generated Disasters.

3.2.2. Spatial Relationship of Chain-Generated Disasters

The spatial information of chain-generated disasters is also extremely complex, with descriptions of space including points (longitude and latitude), lines (highways, railways), and areas (villages, towns), etc. This thesis utilizes existing spatial relationships to describe the spatial positional relationships among chain disasters. Referring to the classification of spatial relationships by Zhang Xueying et al. [37], the spatial relationships are divided into topological relationships, distance relationships, and directional relationships.

Topological relationships describes the spatial structural characteristics of how spatial objects are connected, adjacent, or contained to each other. It focuses on the relative positions and connectivity between spatial entities, without considering their specific shapes or sizes. This thesis utilizes the Dimensionally-Extended 9 Intersection Matrix model (DE-9IM) [38] to describe the topological relationships between spatial objects. In this model, each spatial entity is meticulously divided into three parts: interior, boundary, and exterior. Assuming that there are two disaster spatial entities E and F, and their spatial topological relationships are described as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Topological Relationships of Chain-Generated Disasters.

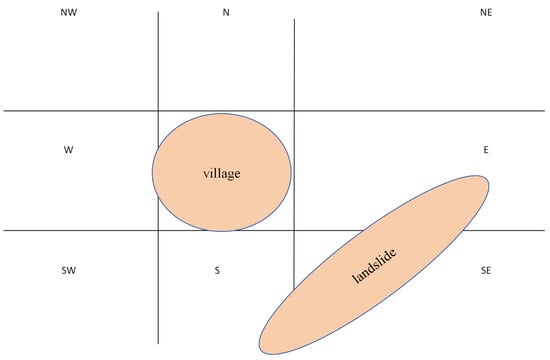

Directional relationships refers to the description of the relative direction between objects or locations in space. Directional relationships is crucial for comprehending natural phenomena such as terrain, climate patterns, and population distribution. This thesis chooses to describe the directional relationships between spatial entities on a two-dimensional plane. Based on the directional relationship matrix model proposed by Goyal et al. [39], the space is divided into nine regions, with the two-dimensional minimum bounding rectangle of the spatial entities as the fundamental unit. As shown in Figure 3, the center is represented by O, and the remaining areas are denoted by their geographical orientations, with clockwise being North (N), Northeast (NE), East (E), Southeast (SE), South (S), Southwest (SW), West (W), and Northwest (NW). Subsequently, the azimuth direction is represented by the overlap between the target and each region, and the region with the largest overlap is selected for description. As the landslide location located in the southwest of the village shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The spatial relationship of chain-generated disasters.

Distance relationships measure the closeness or remoteness between objects, locations, or events in space, and can be represented by precise numerical values or vague qualitative descriptions (such as near, medium, or far). This thesis defines different distance scales based on spatial scope, disaster impact capacity, and the impact degree of the same disaster. For instance, in a strong earthquake, within 20 km of the epicenter is considered “very close”, within 50 km is “near”, 200 km is “medium”, and above 200 km is “far”. Within 20 to 50 km of the epicenter, strong tremors and building collapses may occur. Within 50 to 200 km, the tremor will weaken, but it may cause secondary disasters such as landslides and fires. Over 200 km, there is usually only slight vibration, which has a relatively small impact.

3.2.3. Semantic Relations of Chain-Generated Disasters

Semantic relations mainly explain the relationships among geological disasters and are an important manifestation of the mutual influence among chain-induced disasters. The detailed description is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Semantic Relations of Chain-Generated Disasters.

3.3. Instance Layer of Chain-Generated Disaster Knowledge Graph in High Mountain and Canyon Areas

An instance represents a specific object of a certain entity. For example, the Baige landslide is an example of disasters. The instance layer is the hierarchy that contains specific objects and their related attributes. For a certain disaster instance, the specific definition is as follows:

Among them, Dis represents a certain disaster, represents the geological environment of the disaster, Imp represents the impact of the disaster, Fac represents the disaster-causing factor, Prop represents the disaster-related attribute, and Rel represents the relationship, referring to the relationship between concepts, between concepts and instances, as well as the hierarchical relationship.

During the chain-generated disaster process, there are many single disasters. Describing only the instance layer of a single disaster is not sufficient. Therefore, for a certain chain-generated disaster, the instance definitions are as follows:

Among them, represents the disaster chain instance, represents the disaster instance, n represents n disasters in the disaster chain, represents the influence relationship between disasters, represents the influence relationship between and , and t < n. As stated in the semantic relationship of the chain-generated disaster knowledge graph, the relationships among disasters are complex. For instance, there exists a chain-generated disaster with only and , but no , meaning that and have no relation.

4. Construction and Application of Chain Disaster Knowledge Graph in Alpine Canyon Area

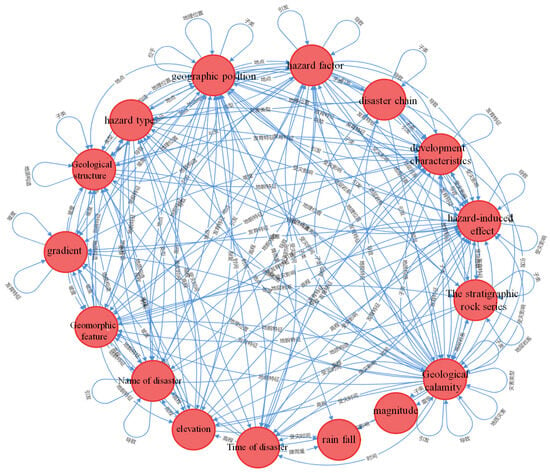

4.1. Pattern Layer of Chain Disaster Knowledge Graph in High Mountain Canyon Area

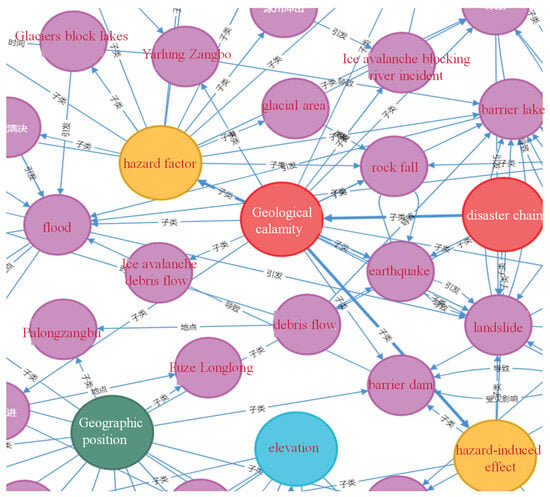

The interrelationships between some concepts of the chain disaster schema layer are shown in Figure 4, and the relationships are derived from the labelled unstructured data samples. For each unstructured data sample, it contains the data itself and entity labels, and the labels are its important means of connecting the schema layer; the labels are equivalent to the concepts of the schema layer, while the sample itself is the conceptual concretisation of the labels. Therefore, according to the interrelationship between labels, the interrelationship between schema layer concepts can be derived. Of course, only a part of the interrelationships between the concepts of the schema layer connected to the data layer can be shown here.

Figure 4.

Chain Disaster Knowledge Graph schema layers in the alpine valley area (partial).

4.2. Data Layer of Chain Disaster Knowledge Graph in Alpine Canyon Area

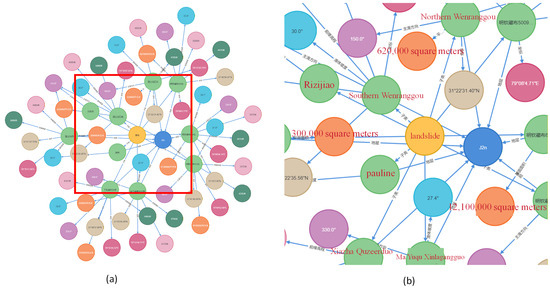

The knowledge graph constructed from structured data is shown in Figure 5. Among them, the yellow colour indicates the landslide concept, the green colour indicates the landslide instance, which belongs to the concept subcategory, and the orange, pink and blue colours indicate the geographic location, leading and trailing edge elevation and other information of the landslide instance. The chain disaster knowledge graph produced by structured data has accurate data and a standardised and concise description. Different from unstructured data, the knowledge graph of structured data has fixed concept types, no missing data, consistent description categories for each disaster, and neat data.

Figure 5.

Knowledge map of structured data on chain disaster in the alpine valley area (where (b) is the content of the red box of (a), among them, blue represents the slope of the sliding body, orange represents the area, and green represents the specific area.).

The knowledge graph constructed by unstructured data through knowledge extraction is shown in Figure 6. Unstructured data knowledge graph description is affected by the labelled data, the data is not streamlined enough, but it contains a large amount of information that is not counted by structured data, which is of great significance in information retrieval.

Figure 6.

Knowledge graph of unstructured data on chain disaster in the alpine valley area (partial).

In order to represent the relationship between the schema layer and the data layer more clearly, the data layer data is divided according to the schema layer concepts, as shown in Figure 7. In the figure, the purple colour indicates the data layer entities, and the rest of the colours are the concept layer concepts. The mapping from the conceptual layer to the data layer is represented by “subclasses”.

Figure 7.

Mapping of Chain Disaster Model Layers and Data Layers in the Alpine Canyon Area (partial).

In terms of information querying, the Neo4j-based Chain Disaster Knowledge Graph clearly presents conceptual terms, attributes, attribute characteristics (attribute values), and relationships between entities (edges) related to chain disaster in a structured and multidimensional visualisation. In addition to the knowledge graph visualisation, the Neo4j graph database can be queried for specific information and displayed in a graphical style.

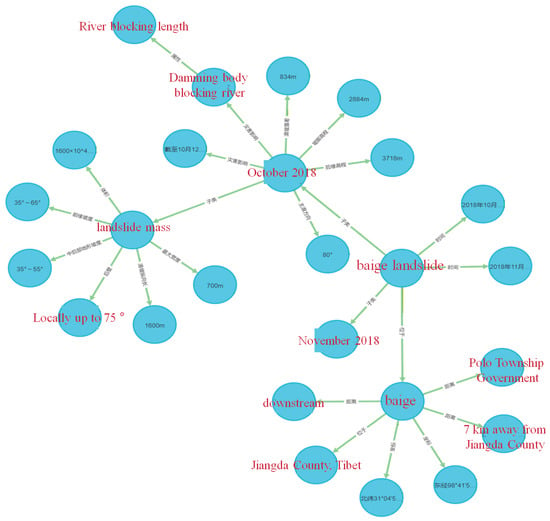

In the chain disaster knowledge graph, the query is performed related to the Baige landslide, as shown in Figure 8, which shows some information about Baige landslide, including the cause of Baige landslide, the time of the disaster, geographic location, geomorphological features, geological structure and so on.

Figure 8.

Some relevant information on the Baige landslide.

4.3. Event Application of Chain Disaster Knowledge Graph in Alpine Canyon Area

Overview of the Study Area

To demonstrate the utility of the constructed knowledge graph in supporting disaster chain analysis, this section presents a focused case study on the Baige landslide. We showcase how the graph facilitates integrated hazard analysis by querying and visualizing the interconnected disaster elements, geological context, and temporal sequences. This case serves to validate the framework’s capacity for organizing complex disaster information and revealing underlying relationships, which forms the essential foundation for more advanced applications such as trend prediction and impact assessment.

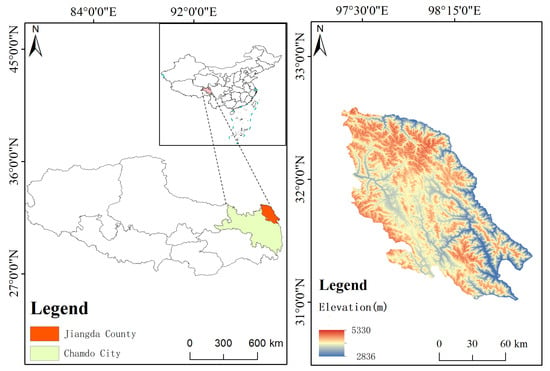

Baige is located in Jiangda County, Qamdo, Xizang, situated in the valley area upstream of the Jinsha River, separated from Baiyu County in Ganzi, Sichuan, by just the river. Due to the strong geological tectonic influence, the regional gullies and ravines across the force of the region, the regional average elevation of 3800 m belongs to the typical alpine canyon geomorphology. Baiyu landslides have also caused several river blockage events, such as on 10 October and 3 November 2018, two consecutive large-scale landslides occurred, resulting in the blockage of the Jinsha River and the formation of a weir, as shown in Figure 9. The geographical location of Baige as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

River blockage by the Baige landslide.

Figure 10.

Overview of the Baige study area.

Figure 8 presents the results of a multi-dimensional hazard analysis query centered on the “Baige Landslide”. Beyond listing factual attributes, the graph visually reveals the causal and spatial linkages between the triggering factors (e.g., seismic activity), the geological environment, and the consequent disaster events. The knowledge graph of some of the information on the Baige Chain Disaster is shown in Figure 11, and only part of the information is shown due to the large amount of complete information, which is not displayed well. Selected data are available from papers and reports related to the Baig landslide, made by extracting ternary groups through manual labelling. The graph records in detail the disaster description information such as the occurrence event, location, landslide characteristics, landslide body description, etc. of the Baige chain disaster. Using “disaster time” and “Baige” as keywords, we can search in the graph, and get that Baige had two landslides on 10 October and 3 November 2018, which blocked the Jinsha River.

Figure 11.

Knowledge Graph of the Baige Chain Disaster (partial).

The case study confirms that the knowledge graph provides a structured and analyzable representation of cascading disaster chains. The established network of entities, relationships, and spatio-temporal attributes creates a ready-to-use knowledge base for further scenario-based applications.

5. Conclusions

With the diversification of chain disaster data sources and the expansion of scale, traditional information processing methods can hardly meet the needs of in-depth expression and efficient application. Knowledge graph, as a semantic knowledge organization, provides a new technical path for the transformation of “information-knowledge-application”. In this paper, we focus on the earthquake and rainstorm chain disaster in high mountain valley area, and systematically study the construction method of the knowledge graph of the chain disaster, and achieve the following results: we constructed the schema layer of the knowledge graph, including the concept layer, the relationship layer, and the instance layer, in which the concept layer is modeled from the four aspects of the disaster geologic environment, the disaster-causing factor, the impact of the disaster, and the disaster-related attributes, and the relationship layer covers the temporal, spatial, and semantic relationships, and the instance layer is used to express specific events; the data layer is constructed to integrate heterogeneous data from multiple sources to form the chain disaster entity-relationship dataset (DCER-MC) in alpine valley area, which provides the basic resources for the construction of the knowledge graph, improves the consistency and accuracy of the graph, and realises the functions of efficient storage, visualisation and complex query by using the Neo4j graph database, and verifies the practical application value of the graph by taking the Baige area as an example.

Despite these advances, the current framework has limitations that also indicate directions for future work. The reliance on manual annotation presents a bottleneck for scaling the dataset, calling for more automated knowledge extraction methods. The static dataset may also lead to update delays, which could be mitigated by integrating real-time monitoring data from IoT and sensor networks. Furthermore, enhancing the scalability and contextual awareness of the system through linkage with global disaster databases (e.g., GDACS) would support broader application. Addressing these aspects, along with the adoption of advanced large language models for knowledge acquisition, will be key to advancing intelligent disaster management services in alpine canyon regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X. (Jiangbo Xi) and H.S.; methodology, H.S. and L.J.; software, J.X. (Jiahuan Xu) and L.J.; validation, H.S., J.X. (Jiahuan Xu) and C.R.; formal analysis, H.S.; investigation, H.S. and L.J.; resources, J.X. (Jiangbo Xi) and C.R.; data curation, H.S. and J.X. (Jiahuan Xu); writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, J.X. (Jiangbo Xi) and C.R.; visualization, H.S.; supervision, J.X. (Jiangbo Xi); project administration, J.X. (Jiangbo Xi); funding acquisition, J.X. (Jiangbo Xi). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3008300 & 2023YFC3008304, 2022YFC3004302); in part by Major Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41941019); in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42371356, 42171348, 41929001); in part by the Shaanxi Province Science and Technology Innovation Team (2021TD-51), the Shaanxi Province Geoscience Big Data and Geohazard Prevention Innovation Team (2022); in part by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (300102262202, 300102260301/087, 300102264915, 300102260404/087, 300102262902, 300102269103, 300102269304, 300102269205, 300102262712); in part by the Northwest Engineering Corporation Limited Major Science and Technology Projects (XBY-YBKJ-2023-23); in part by The Key Scientific and Technological Project of Power China Corporation (KJ-2023-022).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Haixing Shang was employed by the company Northwest Engineering Corporation Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- He, N.; Qu, X.; Yang, Z.; Xu, L.; Gurkalo, F. Disaster mechanism and evolution characteristics of landslide–debris-flow geohazard chain due to strong earthquake—A case study of niumian gully. Water 2023, 15, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Huang, M.; Liu, S.; You, Q.; Meng, F. Research on the Construction and Application of Earthquake Emergency Information Knowledge Graph Based on Large Language Models. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 127742–127757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yin, C.; Liu, K.; Zhai, X.; Sun, Y.; Du, M. Research on the construction of geographic knowledge graph integrating natural disaster information. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 10, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniest, A.; Schellart, W.P. A geological map of the Scotia Sea area constrained by bathymetry, geological data, geophysical data and seismic tomography models from the deep mantle. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 210, 103391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, C. A new structure for representing and tracking version information in a deep time knowledge graph. Comput. Geosci. 2020, 145, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ji, X.; Dong, Y.; He, M.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y. Chinese mineral question and answering system based on knowledge graph. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 231, 120841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Ma, K.; Lv, H.; Tao, L.; Xie, Z. Construction and application of a knowledge graph for iron deposits using text mining analytics and a deep learning algorithm. Math. Geosci. 2023, 55, 423–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Peng, L. Disaster prediction knowledge graph based on multi-source spatio-temporal information. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richens, R.H. Preprogramming for mechanical translation. Mech. Transl. Comput. Linguist. 1956, 3, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, L.; Hou, M.; Yang, J.; Zhong, H.; Wang, C. Climate paleogeography knowledge graph and deep time paleoclimate classifications. Geosci. Front. 2023, 14, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokman, F.N.; de Vries, P.H. Structuring knowledge in a graph. In Human-Computer Interaction: Psychonomic Aspects; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 186–206. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Ying, S.; Luo, Q.; Luo, H.; Kuai, X.; Xia, H.; Shen, H. A bibliometric and visual analysis of global geo-ontology research. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 99, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, M.; Murphy, K.; Tresp, V.; Gabrilovich, E. A review of relational machine learning for knowledge graphs. Proc. IEEE 2015, 104, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; He, S. Dynamic simulation of a mountain disaster chain: Landslides, barrier lakes, and outburst floods. Nat. Hazards 2018, 90, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Xie, Z.; Wu, L.; Li, W. Geoscience keyphrase extraction algorithm using enhanced word embedding. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 125, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzanzanica, M.; Mercorio, F.; Cesarini, M.; Moscato, V.; Picariello, A. GraphDBLP: A system for analysing networks of computer scientists through graph databases: GraphDBLP. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 18657–18688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Xue, Y.; Dong, J.; Hu, Y.; Hill, R.; Guang, J.; Li, C. Grid workflow validation using ontology-based tacit knowledge: A case study for quantitative remote sensing applications. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 98, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R. Mineral exploration using subtle or negative geochemical anomalies. J. Earth Sci. 2021, 32, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, H.; Zhu, K.; Yu, S.; Li, J. Multistage assignment optimization for emergency rescue teams in the disaster chain. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2017, 137, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, H. Preliminary study on geological hazard chains. Earth Sci. Front. 2007, 14, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jia, S.; Xiang, Y. A review: Knowledge reasoning over knowledge graph. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 141, 112948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, W.; Yu, K. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF models for sequence tagging. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.01991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Barbosa, D. Neural fine-grained entity type classification with hierarchy-aware loss. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.03378. [Google Scholar]

- Le, P.; Titov, I. Improving entity linking by modeling latent relations between mentions. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.10637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Tian, M.; Ma, K.; Xie, Z.; Tao, L.; Liu, J. Geological map-oriented knowledge graph construction and intelligent Q&A application. Chin. J. Geol. 2024, 59, 588–602. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, M.; Xie, N.; Jiang, L.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y. Research on the Construction of Knowledge Graphs for Agricultural Meteorological Disasters: A Review. Chin. J. Agrometeorol. 2024, 45, 1216. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Fan, L.; Li, X.; Jiang, H.; Lu, N. Construction and analysis of knowledge graphs for multi-source heterogeneous data of soil pollution. Soil Use Manag. 2023, 39, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Dong, C.; Kang, F. Research on the construction method of earthquake disaster prevention knowledge graph. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 2021, 46, 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Cui, S.; Huang, W.; Pei, X.; Fan, X.; Ai, Y.; Zhao, W.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Construction of a landslide knowledge graph in the field of engineering geology. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2023, 48, 1601–1615. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Q.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, D.; Ma, K.; Tao, L.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, B. Knowledge graph for identifying geological disasters by integrating computer vision with ontology. J. Earth Sci. 2023, 34, 1418–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Qiao, S.; Yao, Y. Risk Assessment of Typhoon Disaster Chain Based on Knowledge Graph and Bayesian Network. Sustainability 2025, 17, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ye, P. Geoscience knowledge graph (GeoKG): Development, construction and challenges. Trans. GIS 2022, 26, 2480–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Hou, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Shen, S.; Cheng, Q.; Feng, Z.; Wang, X.; Lv, H.; et al. Geoscience knowledge graph in the big data era. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2021, 64, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, E.; Etminani, K. Knowledge-graph-based explainable AI: A systematic review. J. Inf. Sci. 2024, 50, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Tang, B.; Li, Y.; Lei, K. CBN: Constructing a clinical Bayesian network based on data from the electronic medical record. J. Biomed. Inform. 2018, 88, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Qian, H.; Wu, F.; Liu, J. A method for constructing geographical knowledge graph from multisource data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, C.J.; Zhu, S.N. Annotation for geographical spatial relations in Chinese text. Acta Geod. Et Cartogr. Sin. 2012, 41, 468–474. [Google Scholar]

- Clementini, E.; Sharma, J.; Egenhofer, M.J. Modelling topological spatial relations: Strategies for query processing. Comput. Graph. 1994, 18, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L. Basic issues and research agenda of geospatial knowledge service. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2023, 44, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).