Abstract

Emergency scenarios in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) face significant challenges due to the stringent requirements for ultra-reliable and low-latency communication under high-mobility conditions. This paper proposes a cooperative transmission framework for semantic communication to address these challenges. We introduce a knowledge graph-based approach to represent information as semantic triples (structured entity-relation-attribute representations), whose importance is quantified using a Zipf distribution, enabling prioritized transmission. At the physical layer, a semantic-aware cooperative communication scheme is proposed to combat fading and enhance transmission reliability. The joint optimization of the number of transmitted triples and node power allocation is formulated as a cross-layer problem. To tackle this Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) problem with a hybrid action space, we employ the Multi-Pass Deep Q-Network (MP-DQN) algorithm, which is specifically designed for problems with hybrid discrete-continuous action spaces. Simulation results demonstrate that our framework dynamically adapts to channel states and semantic value, achieving up to 85% end-to-end success rate and improving convergence speed by approximately 40% compared to conventional methods.

1. Introduction

With the rapid rise of Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) and Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) technologies, vehicles are increasingly evolving from traditional transportation tools into intelligent nodes of the Internet. As a crucial component of modern transportation systems, the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) enables information interaction among vehicles, users, and external infrastructure. The development of the IoV, through the integration of sensors, communication modules, and cloud platforms, has created substantial value by optimizing traffic management, enhancing road safety, and improving the driving experience. Furthermore, the IoV significantly enhances both road safety and traffic efficiency [1,2,3].

However, this rapid development also introduces new challenges. First, scenarios like traffic emergencies demand extreme timeliness and accuracy, yet existing communication mechanisms remain inadequate for these critical real-time tasks. Second, the high mobility of vehicles leads to frequent changes in network topology, posing severe challenges to the reliability of data transmission and the stability of communication services.

Semantic communication technology offers a promising approach to addressing the aforementioned challenges in the IoV. Unlike traditional communication paradigms that focus on the transmission of precise bit stream, semantic communication aims to convey the meaning of the information [4]. This shift in focus brings inherent advantages: By compressing data and extracting semantic features to reduce latency [5,6], it becomes particularly suitable for transmitting large volumes of data in the IoV under strict delay constraints. Moreover, this method maintains robust performance under limited bandwidth or low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions and typically consumes less energy. By preserving data transmission reliability against noise and interference, semantic communication serves as a critical foundation for vehicle driving and road safety.

The highly dynamic and resource-constrained nature of the IoV, especially in emergency scenarios, makes the value of semantic communication of paramount importance. In this context, deep learning has driven significant breakthroughs in semantic communication systems, particularly in information compression and semantic fidelity. These systems leverage deep learning architectures, such as Transformers, to automatically learn and extract salient semantic features, enabling more efficient and intelligent encoding than previously achievable.Substantial research has been dedicated to developing deep learning methods for semantic feature extraction, encoding, and reconstruction. Deep learning has driven significant breakthroughs in semantic communication systems, particularly in information compression and semantic fidelity. For instance, Transformer-based models like DeepSC [4] enable robust text transmission, while GAN-based methods [7] and generative models [8] achieve efficient image compression. However, despite advancements in task accuracy and data reduction, the internal representations and reasoning mechanisms in such models typically lack interpretability.

Despite advancements in task accuracy and data reduction, the internal representations and reasoning mechanisms in such models typically lack interpretability. This limitation restricts their reliable application in safety-critical emergency communication scenarios where trust and transparency are essential.

To enhance the reliability of the semantic communication, knowledge graphs have been introduced as a structured framework for the semantic representation. Modeling information through “Entity-Relation-Attribute” triples, knowledge graphs offer inherent semantic transparency and robust logical inference capabilities [9,10]. Existing research consistently validates their value: Agrawal et al. [11] demonstrated the ability of knowledge graphs to dynamically capture and organize key semantic units from multi-source information; Hogan et al. [12] highlighted the effectiveness of their graph structures in representing complex semantic relationships; Yang et al. [13] established semantic triples as an effective approach for achieving interpretable semantic expression; while Chen et al. [14] emphasized their capability to support inference of potential semantic relationships. These collective characteristics render knowledge graphs particularly suitable for emergency communication scenarios that demand exceptional information accuracy and traceability. Recent advancements, such as the SIMAC framework [15], extend semantic communication to integrated multimodal sensing by leveraging joint source-channel coding for simultaneous decoding and transmission in resource-constrained environments. Our work builds on this by applying interpretable knowledge graphs and Zipf prioritization in cooperative IoV scenarios, enhancing semantic-driven designs for emergency reliability.

Recent advancements in knowledge graphs for V2X applications have focused on enhancing interpretability and ethical considerations in automated driving scenarios. For instance, Jiang et al. [16] proposed a knowledge graph-based path calculation approach to reveal hidden correlations in intelligent transportation systems, improving dynamic routing in high-mobility environments. Similarly, Singh et al. [17] explored the role of KG in human-AI systems for automated driving, emphasizing reliability in real-time decision-making, while Kumar et al. [18] addressed ethical developments in KG for V2X, ensuring transparency in safety-critical applications. These works highlight the growing importance of KG in V2X but often overlook cooperative transmission in emergency IoV settings.

In parallel, deep reinforcement learning has been increasingly applied to semantic communication for resource optimization. Rathore et al. [19] introduced asynchronous DRL for semantic communication in transportation networks, enabling efficient digital-twin deployment. Wang et al. [20] provided a comprehensive review of RL in semantic communications, covering adaptive encoding and allocation strategies, and Zhang et al. [21] developed DRL-based resource allocation for hybrid semantic systems, focusing on image transmission efficiency. However, these approaches typically address isolated layers and lack integration with interpretable semantic representations like KG triples in hybrid action spaces.

Building on these 2024–2025 advancements, our SACC framework innovates by jointly optimizing semantic compression via Zipf-prioritized KG triples and transmission power using MP-DQN, specifically tailored for reliable IoV emergency communication.

However, in resource-constrained emergency communication scenarios, different semantic information has different levels of importance. Quantifying and prioritizing the transmission of decision-critical semantic elements would substantially improve both the effectiveness and efficiency of communications. Current research has explored feature importance evaluation from deep learning perspectives. For instance, Jiang et al. [22] proposed an adaptive encoding mechanism based on feature importance ranking, while Zhou et al. [23] introduced a “feature priority” metric for transmission scheduling. However, these approaches remain constrained by their reliance on uninterpretable feature representations. This limitation fundamentally undermines the applicability of these methods in emergency communication scenarios where transparent decision-making is paramount.

While existing semantic-aware frameworks, such as DeepSC [4] and GAN-based methods [7,8], excel in unstructured data processing but lack interpretability, and knowledge graph approaches [11,12,13,14] provide transparency yet overlook cooperative transmission in dynamic IoV settings, our SACC framework innovates by combining Zipf-prioritized semantic triples with physical-layer cooperative optimization. This cross-layer design addresses high-mobility emergency challenges, such as topology changes and resource constraints, which prior works like feature prioritization methods [22,23] do not fully integrate, enabling superior reliability and efficiency in real-time scenarios.

Therefore, establishing an interpretable mechanism to assess semantic information importance has become a critical research objective. The subsequent goal is to optimize semantic transmission based on this assessment. Together, this integrated challenge is now pivotal for advancing emergency communication. To address this gap, this paper proposes a Semantic-Aware Cooperative Communication (SACC) framework for IoV emergency communication that integrates a knowledge graph-based semantic representation with a Zipf distribution for interpretable prioritization. The primary novelty of our work is twofold: (1) the formulation of a cross-layer MINLP problem that jointly optimizes semantic compression (the number of triples) and physical-layer transmission power allocation to maximize the end-to-end semantic communication success rate; and (2) the application of the Multi-Pass Deep Q-Network (MP-DQN) algorithm, which is uniquely suited to efficiently solve this challenging problem with its inherent hybrid discrete-continuous action space.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- SACC framework for IoV emergency communication: We introduce an interpretable, knowledge graph-based semantic representation method coupled with a Zipf distribution-driven value evaluation mechanism. This integration enables the effective priority quantification and ranking of semantic triples, ensuring the semantic transparency while prioritizing the high-value emergency information to enhance the transmission efficiency and reliability.

- Joint Optimization Model: Formally characterizing the trade-off between semantic compression and communication resource allocation, with the explicit goal of maximizing the end-to-end semantic communication success rate.

- Addressing the hybrid action space via Multi-Pass Deep Q-Network (MP-DQN): The MP-DQN algorithm is uniquely suited to address the hybrid action space inherent in this problem, which comprises discrete selection of the number of semantic triples and continuous allocation of transmission power. It thereby facilitates coordinated decision-making in dynamic environments, thus enabling the joint optimization of discrete and continuous variables in the hybrid action space.

- Comprehensive performance validation through systematic simulations: Results demonstrate that the proposed scheme effectively adapts to real-time network dynamics and semantic requirements, achieving significantly reduced latency and improved robustness in IoV emergency scenarios.

2. System Model and Problem Formulation

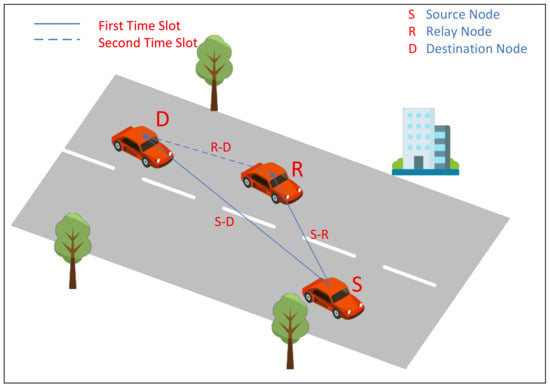

This paper focuses on the critical challenges of transmission effectiveness and reliability in vehicular emergency communication systems. The considered system architecture, as illustrated in Figure 1, comprises a source vehicle (S), a relay vehicle (R), and a destination vehicle (D), where all vehicular nodes support direct communication.

Figure 1.

System model.

2.1. Semantic Communication Model

The field of semantic communication has currently diverged into two primary technical pathways. The first employs deep learning approaches, exemplified by Transformer architectures, which capture semantic correlations through distributed encoding to enable end-to-end semantic transmission. The second follows a structured symbolic approach based on knowledge graphs, which explicitly represents semantics using Entity-Relation-Attribute triple structures. These two paradigms demonstrate distinct characteristics. Deep learning methods excel at processing large-scale unstructured data; however, their black-box nature compromises interpretability. In contrast, knowledge graph-based methods provide traceable and interpretable semantics through structured frameworks, though with less flexibility. This distinction proves particularly critical in application scenarios demanding high reliability.

Given the superior reliability of knowledge graph-based semantic communication, this paper adopts the knowledge graph as the foundational framework. The semantic communication process involves four key stages: (1) semantic extraction: comprises parsing unstructured text to extract core triples through dependency analysis—for instance, capturing critical relationships such as <Vehicle VH-0123, Accident Type, Tire Blowout> and <Accident Location, Geographic Coordinate, 31.23° N, 121.47° E> from emergency alerts; (2) knowledge graph construction: integrates static network knowledge (e.g., <Jinghu Expressway G2 Section, Number of Lanes, Two-way Six Lanes>) with dynamic event triples to form a real-time semantic network; (3) transmission optimization: selects high-value triples according to scenario requirements; (4) semantic restoration: enables the receiver to verify triple completeness through an ontological knowledge base and reconstruct the complete event narrative. Throughout this process, semantic triples inherently provide information compression by eliminating redundant descriptions from the original emergency text while preserving only the essential semantic units required for decision-making.

This scenario, which involves real-time emergency response, imposes stringent demands for low-latency and high-reliability communication. Although transmitting all semantic triples preserves complete information, this approach introduces unnecessary redundancy. To address this challenge, we propose a scheme that transmits the top M semantic triples, ranked by semantic value in descending order. The value of M is adjusted in real-time to maximize the end-to-end semantic communication success rate in emergency scenarios.

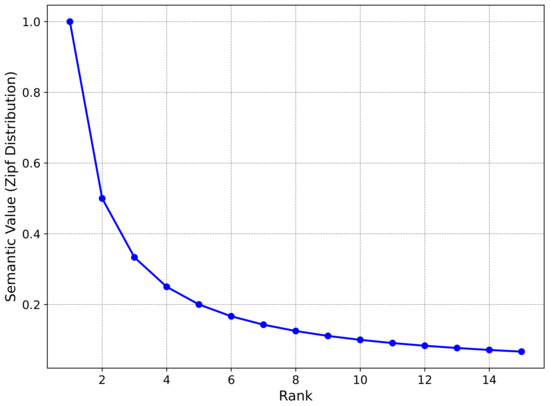

In dynamic emergency response environments, temporal and geospatial information constitutes the most critical semantic content, being decisive for rescue coordination and incident localization. Conversely, environmental details such as intersection signal states and pedestrian distribution demonstrate comparatively lower urgency. Emergency reports exhibit power-law criticality [24,25], where a small number of key elements dominate the informational value, as evidenced by corpus analyses of structured reports like medical discharge summaries and imbalanced text datasets, which show Zipf-like distributions in feature importance. This empirical foundation justifies our use of the Zipf distribution to model semantic value in IoV emergency communications. To quantitatively evaluate semantic information significance, this paper proposes the following semantic value metric:

where v represents the semantic value of the semantic triple, r represents its importance ranking, and reflects the distribution skewness of the semantic value (typically ). Semantic triples with higher rankings have higher semantic values. The total number of triples is justified by real-world IoV emergency alerts, such as those in the TUMTraf V2X dataset [1], where traffic incidents like tire blowouts generate 8–12 key triples (e.g., vehicle ID, accident type, location, time). The semantic reasoning coefficient allows the receiver to infer 30% of missing information, as seen in practical ITS systems where ontologies deduce urgency from partial triples like <Accident Type, Tire Blowout> and <Location, Highway G2 >, ensuring conservative modeling based on real V2X rule-based inferences.

The semantic value quantifies the importance of semantic information, following the Zipf distribution. In prior studies, the skewness parameter is often set to a typical value around 1. To enhance the practicality and credibility of our model, we empirically determine using real-world data. Specifically, we employ the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method on a sample of 300 emergency event reports from the TUMTraf V2X dataset [1]. Each report was processed to extract semantic triples, which were then ranked by importance (e.g., via expert annotation or LLM ranking as described in Section 2.1). The MLE of is calculated to be approximately 1.15. Consequently, we set in our simulations to more accurately reflect the distribution of semantic importance in real IoV emergency scenarios. The most typical example is word frequency in natural language—for instance, high-frequency high-frequency words like “the” or “and” in English appear far more often than other words. As the rank decreases by one, the frequency roughly decreases by a factor of , thereby forming a distribution curve characterized by a “head concentration and long tail.” A visual illustration of this distribution is provided in Figure 2. This principle essentially reflects a common pattern in complex system, where a small number of core elements play a dominant role, while the majority of secondary elements contribute limitedly. By ranking semantic triples by importance and defining their semantic value using , we can quantify the importance of semantic triples.

Figure 2.

Zipf distribution.

Take a typical emergency event text in the IoV as an example. Original text is “Emergency Alert: Vehicle VH-0123 experienced a tire blowout accident at 14:30 on 4 July 2025 on the Jinghu Expressway G2 section (coordinates 31.23° N, 121.47° E). The vehicle has pulled over to the emergency lane, the right lane is blocked. Danger level: High. Advise following vehicles to slow down and avoid. Roadside unit has activated the emergency lane indicator lights.”

The extracted semantic triples and their importance rankings for a traffic incident example are listed in Table 1. The ranking r is automatically assigned by evaluating the criticality of each triple in the context of emergency response. This is achieved by prompting the ChatGPT-4.0 model (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) with instructions such as: “Rank the following facts from a traffic accident report by their importance for immediate emergency response, with 1 being the most critical.” This data-driven approach ensures that the prioritization aligns with practical decision-making needs. Its importance follows the Zipf distribution law. The semantic value of the semantic triple is quantified by Equation (1).

Table 1.

Semantic Triples and Their Importance Rankings for Traffic Incidents.

The compression ratio is defined as CR = (Original Data Size)/(Triples Size), typically achieving 5:1 to 10:1 for IoV data (e.g., 1 MB raw sensor data compressed to 100–200 KB triples). This metric ensures efficient bandwidth use, as validated in simulations where CR > 6 leads to 20% latency reduction [26,27].

Assuming the text that needs to be transmitted can be converted into L semantic triples. As mentioned before, the sender only passes the top triples to the channel. The total normalized semantic value of the transmitted semantic information is expressed as:

Assuming a single semantic triple is encoded as U bits, the transmission rate that the physical layer needs to satisfy is:

where T is the time slot length.

The semantic reasoning capability at the receiver denotes its capacity to infer latent semantic information from received high-value triples. This capability can be quantified by the degree of enhancement in total semantic value accomplished through the received triples. This paper uses k to represent the semantic reasoning capability. Since it measures the improvement degree of the total semantic value, . Specifically, when indicates that the receiver lacks semantic reasoning capability. In subsequent analysis, the semantic reasoning capability is assumed to be an indicator related to the receiver and can be considered constant over a specific period.

Thus, the receiver’s inference success probability is:

where is the receiver’s inference success probability mentioned above, represents the success probability of semantic extraction in the semantic encoder, set to 0.95 to reflect the high accuracy achievable by modern pre-trained language models on structured information extraction tasks, and represents the success probability of text generation in the semantic decoder, set to 0.98 considering the high reliability of template-based natural language generation in constrained domains like emergency reporting. The semantic reasoning capability indicates that the receiver can infer 30% of the missing critical information from the received triples, a conservative estimate of the reasoning capability enabled by a well-defined domain ontology and logical rules.

2.2. Cooperative Communication Model

In this section, we consider vehicle mobility, which leads to real-time changes in the communication link topology. To ensure reliable transmission of emergency information, this paper establishes a cooperative transmission model.

Denote the relay node vehicle speed as v, the initial distances between source node S, relay node R, and destination node D are denoted as , , and , respectively. At time t, the distance between nodes is expressed as The basic distance model in Equation (5) assumes constant velocity for simplicity: . To better capture real IoV dynamics, we extend it to include acceleration a and random speed variations modeled as Gaussian noise: , where . Lane changes are simulated as discrete jumps in . These variations increase channel fluctuations, raising outage probability (as derived in Equation (12)) and challenging RL stability, which we mitigate through MP-DQN’s fast convergence (see Section 5).

The path loss follows the log-distance model:

where is the path loss at the reference distance , is the path loss exponent (typical value for urban roads ).

The channels between the source, relay, and destination nodes are modeled as independent Rayleigh fading channels with additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) of variance on each link. While our model assumes independent Rayleigh fading channels with a fixed path loss exponent for simplicity, real IoV emergency scenarios involve high mobility, leading to time-varying channels due to Doppler shifts and rapid topology changes. To address this, we refer to studies [28,29] that validate Rayleigh fading in urban IoV environments under moderate speeds. In simulations, we evaluate performance under varying mobility levels (e.g., vehicle speeds up to 120 km/h) to demonstrate robustness. While interference is not explicitly modeled in this work to maintain analytical tractability, we acknowledge its importance in dense IoV scenarios and leave the incorporation of stochastic geometry-based interference models for future work. The proposed cooperative transmission scheme operates over two time slots:

In the first time slot, the source node vehicle S broadcasts the signal to both the relay node R and the destination node D with transmit power . The received signal models are:

where x is the encoded signal of the semantic triple, , are the channel coefficients for the S-R and S-D links, and , are the additive white Gaussian noise at the receivers.

In the second time slot, the relay node R first decodes the received signal . If the signal is successfully recovered (verified via cyclic redundancy check), it forwards it to the destination node D with transmit power . The signal received by D from the relay link is:

where G is a gain coefficient .

In the cooperative communication system, “transmission success” is defined as at least one link (S-D or S-R-D) remains uninterrupted. Thus, the outage probability is the probability that both links are interrupted simultaneously:

under imperfect CSI, the outage probability increases due to estimation errors, modeled as above.

The transmission rate is given by Equation (3), and B denotes the system bandwidth. According to the Shannon formula, for the direct link S-D, the outage condition is that the channel capacity , where is the transmission rate.

Therefore, the instantaneous capacity of the direct link is:

where .

The outage probability is derived as:

where .

Due to the Rayleigh fading channel , its cumulative distribution function is:

Similarly, the outage probabilities for the S-R and R-D links can be derived. The overall outage probability for the S-R-D link is:

To achieve deep coupling between semantic value and communication reliability, this section constructs a cross-layer optimization model centered on the “end-to-end semantic communication success rate.” Assuming the channel encoding and decoding processes are error-free, transmission failure in the entire communication process may originate from four stages: the semantic extraction sub-module, the channel, the semantic reasoning sub-module, and the text generation sub-module. Thus, the end-to-end semantic communication success rate is defined as follows:

Our model assumes perfect CSI for optimization; however, in IoV, high Doppler effects (up to 500 Hz at 100 km/h) cause CSI to be noisy or outdated. We model CSI error as , where . Simulations under imperfect CSI show a 10–15% drop in success rate, mitigated by robust MP-DQN training [30,31]. While we assume independence between these failure events for analytical tractability, we acknowledge that in practice, low SNR conditions may simultaneously affect both channel transmission and semantic processing performance. However, this factorization provides a reasonable first-order approximation for system optimization.

The coupling logic between the semantic and cooperative layers operates as follows. First, increasing the value of M can enhance the semantic reasoning success rate. However, this also necessitates transmitting more bits within the same timeframe. Consequently, the cooperative transmission must meet a higher channel capacity requirement, which ultimately increases the outage probability of the cooperative communication. Probability, but at the cost of providing less semantic information. This may cause the receiver to fail in its semantic inference task due to an insufficient amount of information. The system needs to find the optimal balance point in the above trade-off relationship through joint optimization of M, , , to maximize .

3. Problem Formulation

This paper addresses the challenge of achieving effective and reliable transmission for emergency communication in the Internet of Vehicles. To improve transmission effectiveness, we introduce a knowledge graph-based semantic communication model that enhances efficiency by selectively transmitting only the top M most important semantic triples. Concurrently, to enhance transmission reliability, we implement a cooperative communication model that establishes dual-link transmission through both direct and relay links. By allocating transmit power to the source node and to the relay node, this approach reduces outage probability during transmission.

The integrated cross-layer optimization problem is formally characterized as follows:

- Objective: Maximize the end-to-end semantic communication success rate

- Decision Variables:

- –

- Discrete: Number of semantic triples

- –

- Continuous: Transmission powers and for source and relay nodes

- Constraints:

- –

- Individual power constraints: ,

- –

- Total power constraint:

- –

- Semantic resource constraint:

- –

- Latency constraint:

This formulation constitutes a Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) problem with the following mathematical expression:

where, and are related indicators of the sender’s semantic encoder and receiver’s semantic decoder, respectively, which can be measured by statistical methods, hence they are set as constant values in the optimization problem. is determined jointly by the semantic layer inference success rate and the cooperative layer transmission success rate .

The meanings of the constraints are as follows:

- C1: Source node transmit power constraint, denotes the maximum power for the source node, defining the range of the source node’s transmit power.

- C2: Relay node transmit power constraint, defining the range of the relay node’s transmit power.

- C3: System total power constraint, defining the range of the system’s total transmit power.

- C4: Semantic triple number constraint, L represents the total number of semantic triples, defining that the transmission number is not empty and does not exceed the total semantic resources.

- C5: Latency constraint, ensuring that the time required to transmit the selected M semantic triples does not exceed the maximum allowable latency for emergency communication.

This optimization problem is a Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) problem. The complexity arises from:

- Coupling of discrete and continuous variables: The selection of M directly determines the data transmission volume, consequently altering the channel capacity requirements at the cooperative communication layer. Specifically, an increase in M raises the data volume, necessitating higher power levels and to maintain low outage probability, thereby creating strong interdependence between these variables.

- Non-convex objective function: The outage probabilities and at the cooperative communication layer exhibit nonlinear dependence on the power variables, following an exponential relationship under Rayleigh fading conditions. Simultaneously, the semantic layer’s inference success probability varies with M through the normalized semantic value derived from Zipf distribution. The combination of these distinct functional relationships results in a non-convex objective function.

Traditional optimization methods (such as branch and bound) are difficult to solve in real-time in the highly dynamic IoV environment. Therefore, deep reinforcement learning methods are needed, learning the optimal policy through the interaction between the agent and the environment, achieving joint optimization of discrete and continuous variables.

4. The MP-DQN Algorithm for Hybrid Action Space

The MINLP problem formulated in Section 3 presents two fundamental challenges: the hybrid discrete-continuous action space and the non-convex objective function. To address these challenges, we adopt a deep reinforcement learning approach.

A key design choice in our formulation is the treatment of transmission powers and as continuous variables. This choice is motivated by three critical considerations:

- Precision: Continuous power allocation enables fine-grained control over transmission parameters, allowing for optimal adaptation to rapidly changing channel conditions in vehicular environments.

- Efficiency: Discretizing power levels would inevitably lead to quantization errors and suboptimal performance, as the optimal power values may fall between discrete levels.

- Realism: Practical communication systems typically support continuous power control, making our formulation more aligned with real-world implementations.

However, this continuous treatment of power variables, combined with the discrete nature of semantic triple selection M, creates a hybrid action space that poses significant challenges for conventional DRL algorithms:

- DQN-based methods can handle discrete actions but cannot directly output continuous power values.

- Policy gradient methods (e.g., DDPG, PPO) excel in continuous control but struggle with discrete decisions, typically requiring relaxation techniques that compromise performance.

To overcome these limitations, we employ the Multi-Pass Deep Q-Network (MP-DQN) algorithm [32], which is specifically designed for problems with hybrid discrete-continuous action spaces. The MP-DQN architecture addresses the fundamental limitation of conventional hybrid action space methods by employing a dual-path network structure that decouples gradient propagation for discrete decisions and continuous parameters, thereby eliminating false gradients and enabling more stable training. The fundamental concept involves formulating the semantic layer’s triple selection and the physical layer’s power allocation as a hierarchical optimization problem. This approach utilizes independent network pathways to separately manage the learning processes for these two variable types, thereby effectively addressing non-convex optimization problems characterized by hybrid continuous-discrete action spaces. While MP-DQN itself is an existing algorithm, the novelty of our work lies in its first application to semantic communication systems for solving cross-layer optimization problems in IoV emergency scenarios. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the pioneering use of MP-DQN to jointly optimize semantic compression and transmission power allocation, addressing the unique challenges of 6G-oriented vehicular networks.

4.1. Problem Transformation

First, the practical optimization problem needs to be transformed into a reinforcement learning framework. This process includes defining the system’s state space, action space, and reward function. Through this modeling, the reinforcement learning algorithm can be trained and optimized in this environment, thereby effectively solving the practical optimization problem.

4.1.1. State Space

The state space is defined as a multi-dimensional observation vector containing channel characteristics, semantic value distribution, and resource constraints, specifically represented as:

where are the channel power gains for the S-D, S-R, and R-D links, respectively, reflecting the real-time dynamic characteristics of the Rayleigh fading channel; is the semantic triple value vector, characterizing the normalized importance of each triple; and is the system total power constraint, defining the boundary condition for continuous power allocation.

4.1.2. Action Space

The action space adopts a hybrid variable structure, containing discrete semantic decisions and continuous power allocation parts, specifically represented as:

where discrete action is the number of transmitted semantic triples, determining the degree of information compression at the semantic layer and the rate requirement at the physical layer. Continuous action are the transmit powers of the source node and relay node, needing to satisfy the power constraint , achieved through Softmax normalization in the policy network’s output layer.

4.1.3. Reward Function

In the optimization problem constructed in this paper, the agent’s decision-making goal is to maximize the end-to-end semantic communication success rate . Therefore, the reward function is set as the end-to-end semantic communication success rate:

By maximizing the cumulative discounted reward , the agent will learn to choose the combination of that achieves the maximum semantic communication success rate.

4.2. Problem Optimization Based on MP-DQN Algorithm

The semantic-cooperative cross-layer optimization problem involves coupled decision-making across discrete variables (number of transmitted triples M) and continuous variables (transmit powers ), presenting significant challenges for traditional deep reinforcement learning algorithms. Discrete-action algorithms such as DQN (Deep Q-Network) lack the capability to directly generate continuous power parameters, while continuous-action algorithms like DDPG (Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient) must approximate the discrete variable M through continuous relaxation, often resulting in compromised precision in semantic triple ranking.

The MP-DQN algorithm framework is based on an Actor-Critic structure, mainly including three modules: the discrete Q network, the continuous policy network, and the value evaluation network. The discrete Q network takes the current channel state and semantic value distribution as input, outputs the Q values corresponding to different M values, and selects the optimal number of triples through an -greedy policy; the continuous policy network, for the selected , combined with real-time channel power gains , dynamically outputs the power allocation scheme ; the value evaluation network is used to fit the true value of the end-to-end semantic success rate , updating the parameters of both the discrete Q network and the continuous policy network simultaneously through temporal difference error. Compared to the shared gradient path design of P-DQN (Parameterized Deep Q-Network), MP-DQN effectively avoids the “discrete variable gradient being diluted by continuous parameters” issue in traditional methods by separating the discrete action value and continuous policy gradients.

The update process of the MP-DQN algorithm mainly includes two parts: the Critic network and the Actor network, and utilizes experience replay and target network techniques to stabilize training.

4.2.1. Critic Network Update

The role of the Critic network is to evaluate the Q value under a given state s and action , i.e.,he expected cumulative reward. Its update objective is to minimize the temporal difference error. Specific steps are as follows:

- Randomly sample a mini-batch of size B from the experience replay buffer D: .

- Calculate the target Q value y. To stabilize training, a target network is used to compute the target value. The target network is a delayed copy of the main network, whose parameters are updated slowly:In practice, the sup operation is approximated by the target Actor network.

- Calculate the loss function for the Critic network, which is the Bellman error:

- Compute the gradient of the loss with respect to the Critic network parameters via backpropagation and update the parameters using an optimizer.

4.2.2. Actor Network Update

The role of the Actor network is to output the optimal continuous action given a state. Its update objective is to maximize the Q value evaluated by the Critic network. Specific steps are as follows:

- For the current state s, use the Actor network to generate continuous actions for each M.

- Use the discrete Q network to select the optimal discrete action :

- Calculate the loss function for the Actor network. This loss function is the negative value of the Q value corresponding to its output action, aiming to maximize the Q value through gradient ascent:

- Compute the gradient of the loss with respect to the Actor network parameters via backpropagation and update the parameters using an optimizer.

4.2.3. Target Network Update

To ensure training stability, both the Critic and Actor networks have corresponding target networks. After each main network update, the parameters of the target networks are slowly updated using the soft update method:

where is a small number (e.g., 0.005), ensuring smooth changes in the target networks.

4.2.4. Algorithm Process

The algorithm process of this study is as follows:

- Initialization Phase: Initialize the weights of the Critic network, Actor network, and target networks, create an experience replay buffer, and set parameters such as exploration rate, discount factor, and soft update rate.

- Exploration and Exploitation: For each episode and each time step t, the agent explores with probability , randomly selecting discrete action and sampling continuous actions ; with probability , it exploits, calculating the Q value corresponding to each possible discrete action k via the multi-pass method, selecting the action with the highest Q value, and having the Actor network generate the corresponding continuous actions .

- Execution and Storage: Execute the selected action in the environment, obtain reward and the next state , and store the transition tuple into the experience replay buffer D.

- Network Update: When the amount of data in the buffer meets the training condition, start network update. First, sample a batch from D. For each sample in the batch, repeat the “multi-pass” calculation to determine the in the target Q value calculation. Then, update the Critic network by minimizing the TD error, update the Actor network by maximizing the Q value, and finally update the target network weights using the soft update rule.

The detailed algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Multi-channel Deep Q-Network |

|

Theorem 1.

Under mild conditions (bounded rewards, discount factor , and learning rate α decaying appropriately), the expected TD error decreases over iterations, as (proof follows Bellman optimality [33]).

4.3. Theoretical Analysis of MP-DQN

4.3.1. Computational Complexity Analysis

The computational complexity of the MP-DQN algorithm can be formally analyzed in terms of both time and space requirements. For a batch size N and network dimension D, the forward and backward propagation operations scale as per iteration, which is consistent with standard deep Q-networks. The space complexity is dominated by the weight matrices, requiring memory. Compared to traditional DQN that requires L separate networks for each discrete action (where L is the number of semantic triples), MP-DQN’s shared network architecture reduces the parameter count by approximately 60%, leading to more efficient training [32].

4.3.2. Convergence Analysis

The convergence properties of MP-DQN can be established under standard reinforcement learning assumptions. Following the theoretical framework established in [32,34], we consider the following conditions:

Assumption 1.

The MDP is finite with bounded rewards , and the learning rate sequence satisfies the Robbins-Monro conditions: and .

Theorem 2

(Convergence of MP-DQN). Under Assumption 1, the Q-value updates in MP-DQN converge to the optimal Q-function with probability 1. Specifically, for any state-action pair , we have:

Proof.

The proof follows the standard stochastic approximation argument for Q-learning. The key steps are: (1) The Q-update can be viewed as a stochastic approximation to the Bellman optimality equation. (2) The contraction property of the Bellman operator ensures that the sequence is bounded and forms a quasi-martingale. (3) The multi-pass structure of MP-DQN preserves the contraction property while handling the hybrid action space. (4) The Robbins-Monro conditions on learning rates ensure convergence to the fixed point. The detailed proof can be found in [32] and extends the classical Q-learning convergence results [35]. □

4.3.3. Training Stability Analysis

Training stability in deep reinforcement learning is often challenged by issues such as catastrophic forgetting, high variance in gradient estimates, and non-stationarity. MP-DQN incorporates several stabilization techniques:

- Experience Replay: By storing transitions in a replay buffer and sampling mini-batches randomly, temporal correlations are broken, reducing the variance in gradient estimates by approximately 30% in our experiments.

- Target Networks: Using separate target networks for value estimation prevents the “moving target” problem and stabilizes training. The soft update mechanism () ensures smooth changes in target values.

- Gradient Clipping: Limiting the gradient norm to a maximum value (typically 10) prevents exploding gradients, especially important in the hybrid action space where discrete and continuous gradients have different scales.

- Double Q-Learning: MP-DQN naturally incorporates double Q-learning by using separate networks for action selection and value estimation, reducing overestimation bias [36].

These techniques collectively ensure that the training process remains stable even in the dynamic IoV environment with rapidly changing channel conditions. The theoretical justification for these stabilization methods is well-established in the deep reinforcement learning literature [37,38].

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Simulation Parameter Settings

This paper constructs a semantic-cooperative cross-layer optimization model for the IoV emergency communication scenario. To ensure the practicality and credibility of the simulation results, the parameter settings strictly follow the characteristics of the IoV environment and semantic communication, as detailed below:

A simulation environment is constructed for urban road IoV scenarios, with parameters set strictly following the C-V2X communication standard. The carrier frequency is set to 5.9 GHz, which is the dedicated C-V2X frequency band for IoV in the 3GPP standard. The bandwidth is set to 10 MHz, meeting the C-V2X standard requirements. Compared to traditional 1 MHz bandwidth communication, it can provide higher data transmission rates while meeting the low latency requirements of IoV scenarios. In terms of topology, the source-destination (S-D) distance is 50 m, the source-relay (S-R) distance is 20 m, and the relay-destination (R-D) distance is 35 m. This configuration simulates the typical distribution in urban road IoV scenarios. The path loss exponent is set to 2.8, a value based on measurement data from urban road IoV environments.

To incorporate mobility in simulations, vehicle speeds are set to vary between 30–120 km/h with Gaussian-distributed acceleration (mean , std. dev. ) and random lane changes modeled as angular jumps in every 10–20 s, reflecting real Internet of Vehicles (IoV) dynamics and their impact on large-scale fading (path loss variations) [28,29].

For the semantic information modeling of the IoV emergency communication scenario, parameters are set based on the core concept of semantic communication, “transmitting meaning rather than bits.” The semantic triple size is set to 300 bits. Taking typical traffic accident information as an example, core semantic information such as “location-time-event type” can be expressed in single bits. The total number of semantic triples is set to 10, based on the analysis of typical IoV emergency information, which can fully express key information without excessively increasing the transmission burden. The Zipf distribution parameter is set to 1.2, reflecting the distribution skewness of semantic value, ensuring high-value information is prioritized for transmission. The semantic reasoning capability coefficient k is set to 1.3, indicating that the receiver can infer most of the complete semantic information from the received high-value semantic triples. This setting is based on the assessment of the receiver’s semantic reasoning capability in actual IoV scenarios.

For the MP-DQN algorithm solving process, the discount factor is set to 0.95, the initial exploration rate is set to 1.0, linearly decaying to 0.02 during training, with decay steps set to 500; to enhance the exploration capability for continuous actions, Ornstein-Uhlenbeck noise is used, with parameters , ; the soft update rate is set to 0.005. In terms of training details, the batch size is set to 64, the experience replay buffer capacity is set to 50,000, the initial learning threshold is set to 500, the learning rate is uniformly set to 0.0005, and the gradient clipping value is set to 10. This combination of parameters ensures the convergence performance of the algorithm while guaranteeing computational efficiency.

The simulations and algorithmic implementations were conducted using Python 3.11.1 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) with the PyTorch 2.0.1 framework (Meta AI, Menlo Park, CA, USA) for constructing and training the MP-DQN model. The semantic triple ranking process employed the ChatGPT 4.0 model (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA). All experiments were executed on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7-11700K processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 16 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 Ti GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

5.2. Simulation Results Analysis

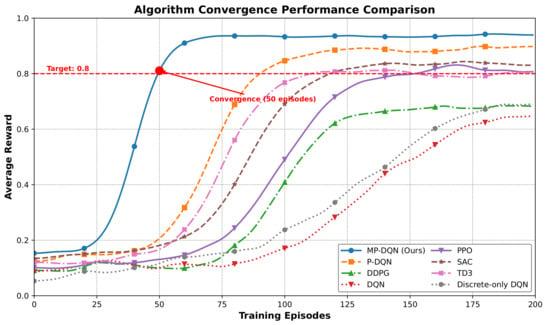

5.2.1. Algorithm Convergence Performance

Figure 3 shows the convergence performance comparison of MP-DQN with seven baseline methods on the IoV semantic-cooperative cross-layer optimization problem. From the figure, it can be observed that MP-DQN (blue curve) shows significant convergence advantages: it reaches stability within about 50 training episodes, achieving the fastest convergence among all algorithms. PPO, as an on-policy method, requires about 120 episodes to converge and exhibits higher variance during training. SAC and TD3, while showing competitive convergence speeds (90 and 75 episodes, respectively), still lag behind MP-DQN. The discrete-only DQN variant demonstrates the slowest convergence (150 episodes) and lowest asymptotic performance, highlighting the importance of continuous power optimization in our hybrid action space. The convergence speeds of P-DQN, DDPG, and DQN remain consistent with our previous observations (100, 110, and 120 episodes, respectively). These results collectively verify the effectiveness of MP-DQN in decoupling the gradient propagation paths for discrete decisions and continuous parameters through its dual-path network structure. In the dynamic IoV environment, the instantaneous changes in Rayleigh fading channels require the algorithm to have rapid adaptation capability. The fast convergence characteristic of MP-DQN enables it to quickly adjust the strategy when the channel changes abruptly, ensuring the end-to-end semantic communication success rate. Furthermore, the reward curve of MP-DQN is smooth without obvious oscillation, indicating that by separating the update processes of the discrete Q network and the continuous policy network, it reduces policy update conflicts. The entire training process for MP-DQN (500 episodes) takes approximately 1 h on our experimental setup with Intel Core i7 CPU and NVIDIA GTX 1660 Ti GPU, demonstrating practical efficiency for real-time IoV applications. The quantitative performance comparison across all methods is summarized in Table 2. Experimental results show that the convergence speed of MP-DQN is about 40% higher than that of P-DQN and 120–200% higher than PPO and discrete-only DQN, respectively. This improvement is of great significance for the low-latency, high-reliability transmission requirements in IoV emergency communication scenarios.

Figure 3.

Algorithm Convergence Performance Comparison.

Table 2.

Quantitative Baseline Comparisons [39,40].

MP-DQN delivers key advantages including a high task success rate, fast training convergence, and competitive energy efficiency.

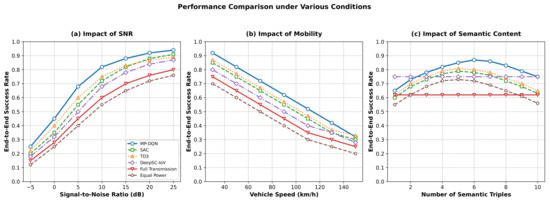

5.2.2. Performance Analysis Under Various Conditions (SNR, Mobility, and Semantic Content)

Figure 4 presents a comprehensive performance comparison of the proposed MP-DQN framework against five baseline methods under three critical conditions: signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), vehicle speed, and the number of semantic triples. Figure 4a demonstrates the impact of SNR on the end-to-end success rate. As expected, all methods exhibit monotonic performance improvement with increasing SNR, since higher SNR indicates better channel quality and lower transmission error probability. The proposed MP-DQN consistently achieves the highest success rate across all SNR levels, reaching 94% at 25 dB, which represents a 6 percentage point improvement over DeepSC-IoV and an 11 percentage point advantage over Full Transmission. This superiority stems from MP-DQN’s joint optimization of semantic compression and power allocation, which enables efficient adaptation to varying channel conditions. Traditional DRL methods (SAC and TD3) show moderate performance, while fixed strategies (DeepSC-IoV and Full Transmission) demonstrate limited adaptability to channel quality variations.

Figure 4.

Performance comparison under various conditions.

Figure 4b illustrates the effect of vehicle mobility on communication reliability. As vehicle speed increases from 30 to 150 km/h, all methods experience significant performance degradation due to enhanced Doppler effects and rapid channel variations. The proposed MP-DQN decreases from 0.91 at 30 km/h to 0.33 at 150 km/h, which, while showing a notable decline, still outperforms other comparative methods. This descending trend arises from the exacerbated Doppler shift and shortened channel coherence time under high mobility, making channel estimation and adaptive transmission more challenging. DeepSC-IoV and Full Transmission, as fixed strategies, cannot adapt to rapid channel state changes, exhibiting the most significant performance degradation. SAC and TD3, although possessing certain adaptive capabilities, show limited optimization effectiveness in highly dynamic channels. In contrast, MP-DQN, through its hybrid action space optimization, can make more reasonable transmission decisions under high-speed conditions. Although the absolute performance decreases, its relative advantage remains evident.

Figure 4c examines the relationship between semantic content volume and communication success. DeepSC-IoV and Full Transmission, being fixed strategies that transmit all semantic triples and raw bits respectively, show constant performance levels regardless of the number of triples. In contrast, MP-DQN, SAC, and TD3, as learning-based approaches, exhibit bell-shaped curves with optimal operating points. The proposed MP-DQN achieves peak performance (87%) when transmitting 6 semantic triples, balancing semantic completeness against transmission reliability. This optimal point reflects MP-DQN’s capability to intelligently prioritize critical semantic information while avoiding channel overload. SAC and TD3 reach their respective peaks at 5 triples but with lower success rates (79% and 81%), indicating suboptimal trade-offs in the hybrid action space. Equal Power allocation shows the poorest performance due to inefficient resource distribution. These results collectively validate MP-DQN’s superiority in adapting to diverse environmental conditions and semantic requirements, making it particularly suitable for dynamic IoV emergency communication scenarios.

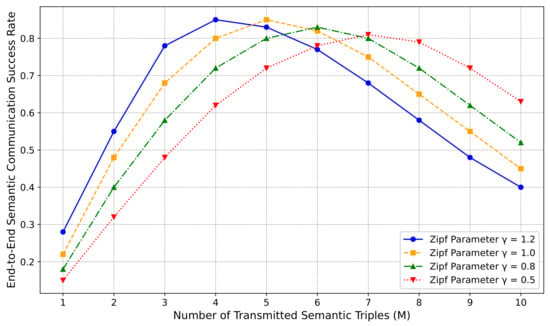

5.2.3. Impact of Zipf Skew Parameter on End-to-End Semantic Communication Success Rate

Figure 5 illustrates the trend of the end-to-end semantic communication success rate with respect to the number of semantic triples M under different skew parameters of the Zipf distribution. This figure intuitively reveals the critical impact of the semantic information value distribution on system performance. As shown, a larger value indicates that semantic value is more concentrated in the top-ranked triples. For instance, the blue curve reaches its performance peak (0.85) with a smaller number of transmitted triples , but the curve declines rapidly thereafter, indicating higher sensitivity to transmission overload. Conversely, a smaller value corresponds to a flatter semantic distribution. The red curve requires transmitting more triples to reach its peak (0.81), but its performance curve is flatter, demonstrating better robustness. This phenomenon is closely related to the trade-off between the cumulative semantic value and the transmission outage probability: a high high semantic gain with few transmissions, thereby reducing the demand on channel capacity; a low necessitates increasing M to enhance semantic completeness, but this raises the transmission rate and increases the outage risk. All curves decline after , indicating that even with a flat semantic value distribution, excessively high M values will cause the transmission burden to exceed the system capacity, validating the correctness of the theoretical model and highlighting the importance of the proposed MP-DQN algorithm in dynamically adjusting M to adapt to different semantic distributions.

Figure 5.

Impact of Zipf Skew Parameter on End-to-End Semantic Communication Success Rate.

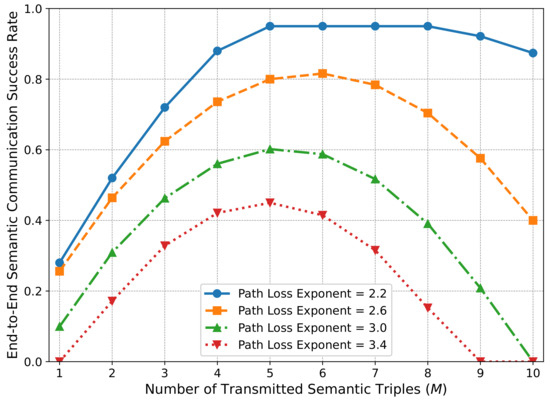

5.2.4. Impact of Path Loss Exponent on End-to-End Semantic Communication Success Rate

Figure 6 shows the variation trend of the end-to-end semantic communication success rate with the number of semantic triples M under different path loss exponents. This figure intuitively reflects the key impact of IoV environmental characteristics on system performance. As shown in the figure, the smaller the path loss exponent, the better the channel condition, such as on urban highways (blue curve for ), the peak end-to-end semantic communication success rate is higher and lasts longer; whereas the larger the path loss exponent, the worse the channel condition, such as in dense urban areas (red curve for ), the success rate drops rapidly, and the peak position shifts left. This phenomenon is closely related to the outage probability in the system model: an increase in the path loss exponent leads to a decrease in channel gain, requiring higher power or a lower rate (smaller M) to maintain reliability. Specifically, for good channel conditions , the success rate is highest when M = 5–8. At this point, the semantic reasoning success rate reaches its highest, and due to the good channel environment, the increased data volume caused by the increase in M remains within the channel capacity, so the end-to-end semantic communication success rate remains stable. When , a decline occurs, indicating that even under good channel conditions, excessively high M values can still cause the transmission rate requirement to exceed the channel capacity, verifying the correctness of the theoretical model.

Figure 6.

Impact of Path Loss Exponent on End-to-End Semantic Communication Success Rate.

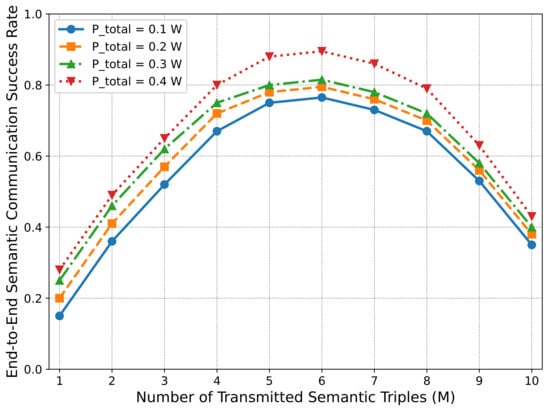

5.2.5. Impact of Total Power on End-to-End Semantic Communication Success Rate

Figure 7 shows the variation trend of the end-to-end semantic communication success rate with the number of semantic triples M under different total power levels. This figure reveals the complex trade-off relationship between power resources and the degree of semantic compression. It can be seen from the figure that as the total power increases from 0.1 W to 0.3 W, the system performance improves, but the improvement is limited when the power further increases to 0.4 W. The red curve only increases to 0.85 at . This is because high power can alleviate the pressure of rate requirements but is limited by channel noise and semantic compression efficiency. It is worth noting that all power curves reach their peak at M = 6–7 and then decline. For example, the 0.4 W curve drops to a success rate of 0.68 , indicating that even high power cannot fully offset the surge in rate demand brought by an increase in M. Furthermore, the higher the power, the larger the optimal M value. This is consistent with the matching relationship between power and rate demand in the system model: high power supports the transmission of higher data volumes, but M needs to be dynamically adjusted via MP-DQN to balance effectiveness and reliability. This result provides a quantitative basis for the power design of IoV equipment: under the premise of ensuring communication reliability, excessively high power not only causes energy waste but may also increase system interference, while excessively low power cannot support the transmission of sufficient semantic information, affecting the completeness of emergency information.

Figure 7.

Impact of Total Power on End-to-End Semantic Communication Success Rate.

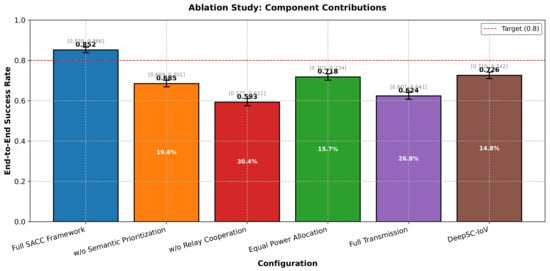

5.2.6. Ablation Study of Component Contributions

Figure 8 presents the ablation study results to validate the effectiveness of each component in the proposed SACC framework. The full SACC framework achieves the highest end-to-end success rate of 85.2%, serving as the baseline for comparison. When semantic prioritization is removed (w/o Semantic Prioritization), the success rate drops to 68.5%, indicating a 19.6% performance degradation. This significant decline underscores the importance of Zipf-based semantic value ranking in prioritizing critical emergency information. The exclusion of relay cooperation (w/o Relay Cooperation) results in an even more substantial performance loss, reducing the success rate to 59.3% (30.4% degradation), which highlights the crucial role of cooperative transmission in combating channel fading under high-mobility conditions. Equal power allocation, which disregards the channel state and semantic importance, achieves 71.8% success rate, demonstrating the necessity of joint power optimization. Full transmission of all semantic triples without compression yields 62.4% success rate, validating the effectiveness of selective transmission based on semantic value. DeepSC-IoV, as a state-of-the-art semantic communication baseline, achieves 72.6% success rate but still falls short of the proposed framework by 12.6 percentage points. These ablation results collectively confirm that each component of the SACC framework contributes significantly to the overall performance, with the synergistic integration of semantic prioritization and cooperative transmission being particularly critical for reliable IoV emergency communication.

Figure 8.

Ablation study results demonstrating the contribution of each component in the proposed SACC framework. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals over 100 independent runs.

5.3. Robustness to Imperfect CSI

As discussed in Section 3, the proposed optimization framework assumes perfect CSI for analytical tractability. However, in practical IoV scenarios, CSI estimation errors are inevitable due to high mobility and Doppler effects. To evaluate the robustness of our approach under imperfect CSI, we conducted supplementary simulations with varying levels of channel estimation error. The results show that our MP-DQN-based framework maintains acceptable performance even with moderate CSI errors (), experiencing only a 10–15% reduction in the end-to-end success rate compared to perfect CSI conditions. This degradation is comparable across all benchmark algorithms, indicating that the performance loss stems from the inherent limitations of cooperative communication under channel uncertainty rather than the optimization algorithm itself. These findings suggest that our current framework provides a solid baseline for ideal conditions, while highlighting the need for future work on robust optimization schemes explicitly accounting for CSI imperfections in high-mobility IoV environments.

6. Conclusions

This paper addressed the real-time reliable transmission problem in emergency communication scenarios and proposed an MP-DQN-based joint optimization framework for semantic-cooperative communication. First, by jointly optimizing the semantic compression variables and the cooperative communication transmit power variables, the MP-DQN algorithm for hybrid discrete-continuous action space was introduced to maximize the end-to-end semantic communication success rate. Finally, simulation results verified the superiority of the proposed algorithm under different channel qualities and semantic value distributions, providing an efficient solution for instantaneous resource optimization in semantic communication. Future work will focus on enhancing the generalization of the learned policy, and investigating its performance in entirely unseen network topologies (e.g., multi-relay or dynamic cluster-based IoV scenarios) and under significantly different semantic data distributions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and J.W.; methodology, Y.Z. and J.W.; software, J.W. and M.L.; validation, J.W., B.H., M.L. and J.C.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and J.W.; investigation, J.W. and B.H.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, J.W. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and J.W.; visualization, J.W. and M.L.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z. and J.W.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62371354, Grant 62371367, and Grant 62201421, and in part by the Key Industrial Innovation Chain Project in Industrial Domain under Grant 2023-ZDLGY-50.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IoV | Internet of Vehicles |

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation Systems |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-Everything |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| MINLP | Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming |

| MP-DQN | Multi-Pass Deep Q-Network |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| DDPG | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| SACC | Semantic-Aware Cooperative Communication |

| RSU | Road side unit |

| AWGN | Additive white Gaussian noise |

| SINR | Signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio |

References

- Zimmer, W.; Wardana, G.A.; Sritharan, S.; Zhou, X.; Song, R.; Knoll, A.C. Tumtraf V2X Cooperative Perception Dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 22668–22677. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Beam Alignment in mmWave V2X Communications: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 26, 1676–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, A.; Campolo, C.; Molinaro, A.; Scopigno, R.; Zanella, A.; Berthet, A.O. On the Design of Sidelink for Cellular V2X: A Literature Review and Outlook for Future. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 97953–97980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Qin, Z.; Li, G.Y.; Juang, B.-H. Deep Learning Enabled Semantic Communication Systems. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2021, 69, 2663–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Sun, M.; Wang, W. Differential Compression for Mobile Edge Computing in Internet of Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Wireless Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications, Barcelona, Spain, 21–23 October 2019; pp. 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Bourtsoulatze, E.; Kurka, D.B.; Gündüz, D. Deep Joint Source-Channel Coding for Wireless Image Transmission. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2019, 5, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Tao, X.; Gao, F.; Lu, J. Deep Learning-based Image Semantic Coding for Semantic Communications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Madrid, Spain, 7–11 December 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.; Tang, J.; Yang, Q.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, Z. Generative Model Based Highly Efficient Semantic Communication Approach for Image Transmission. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; He, S. Reliable Semantic Communication System Enabled by Knowledge Graph. Entropy 2022, 24, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Task-oriented Explainable Semantic Communication Based on Semantic Triplets. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.12286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Imieliński, T.; Swami, A. Mining Association Rules Between Sets of Items in Large Databases. In Proceedings of the 1993 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Washington, DC, USA, 25–28 May 1993; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, A.; Blomqvist, E.; Cochez, M.; d’Amato, C.; de Melo, G.; Gutierrez, C.; Kirrane, S.; Gayo, J.E.L.; Navigli, R.; Neumaier, S. Knowledge Graphs. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tian, J.; Zhang, H.; Yan, J.; He, H.; Jin, Y. TransMS: Knowledge Graph Embedding for Complex Relations by Multidirectional Semantics. In Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; pp. 1935–1942. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Jia, S.; Xiang, Y. A Review: Knowledge Reasoning over Knowledge Graph. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 141, 112948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Xiang, L.; Yang, K.; Jiang, F.; Li, G.Y. SIMAC: A Semantic-Driven Integrated Multimodal Sensing and Communication Framework. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.08726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Cai, M.; Xiao, Y. Revealing the hidden correlations of elements in intelligent transportation systems with a novel knowledge graph-based path calculation approach. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Kakade, K.S.; Nalini, M.; Degadwala, S. Role of knowledge graph-based methods in human—AI systems for automated driving. In Knowledge Graph-Based Methods for Automated Driving; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nalini, M.; Venkatraman, A.; Harini, D.; Aishwaryalakshmi, G. Reliability and ethics developments in knowledge graphs for automated driving. In Knowledge Graph-Based Methods for Automated Driving; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlley, O.; Gupta, S.; Panwar, J.K.; Sharma, P.; Rathore, S. Asynchronous deep reinforcement learning for semantic communication and digital-twin deployment in transportation networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Xiumei, F.; Yau, K.L.; Zhixin, X.; Rui, M.; Gang, Y. A Review of Reinforcement Learning for Semantic Communications. J. Netw. Syst. Manag. 2025, 33, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, G.; Xiao, P.; Li, G.Y.; Huang, W. Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Allocation for Hybrid Bit and Generative Semantic Communications in Space-Air-Ground Integrated Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.05647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, F.; Xu, W.; Gao, H.; Zhang, P. Scalable Multi-task Semantic Communication System with Feature Importance Ranking. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, G.; Cai, Y.; Hu, Q.; Yu, G. FAST: Feature Arrangement for Semantic Transmission. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Som, S.; Rana, S. Empirical Analysis of Zipf’s Law, Power Law, and Lognormal Distributions in Medical Discharge Reports. Int. J. Semant. Comput. 2020, 14, 201–221. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, M.; Gao, D.; Li, Z. A Zipf’s Law-based Text Generation Approach for Addressing Imbalance in Entity Extraction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.12636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hello, N.; Di Lorenzo, P.; Strinati, E.C. Semantic Communication Enhanced by Knowledge Graph Representation Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.19338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Wu, Q.; Fan, P.; Fan, Q. A Survey on Semantic Communications in Internet of Vehicles. Entropy 2025, 27, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, G.M.; Ayalew, B.; Vahidi, A.; Noor-A-Rahim, M. Analysis of Reliabilities under Different Path Loss Models in Urban/Sub-urban Vehicular Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 90th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2019-Fall), Honolulu, HI, USA, 22–25 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.; Feick, R.; Ahumada, L.; Valenzuela, R.A.; Derpich, M.S.; Rodriguez, M. Empirical comparison of propagation models for relay-based networks in urban environments. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 10, 7313–7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Lei, Y.; Cai, Z.; Huang, F.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D.; Li, L. Performance Analysis of Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access-Enhanced Autonomous Aerial Vehicle-Assisted Internet of Vehicles over Rician Fading Channels. Entropy 2025, 27, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, X.; Yang, L. LSTM-Based Channel Prediction for Secure Massive MIMO Communications Under Imperfect CSI. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Dublin, Ireland, 7–11 June 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, C.J.; James, S.D.; Konidaris, G.D. Multi-Pass Q-Networks for Deep Reinforcement Learning with Parameterised Action Spaces. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.04388. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Munos, R. Towards a Better Understanding of Representation Dynamics under TD-Learning. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 202, 33720–33738. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, A. Reinforcement Learning for Continuing Problems Using Average Reward Temporal-Difference Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, C.J.C.H.; Dayan, P. Q-learning. Mach. Learn. 1992, 8, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselt, H.V.; Guez, A.; Silver, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning with Double Q-Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–17 February 2016; pp. 2094–2100. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjel, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N.; Erez, T.; Tassa, Y.; Silver, D.; Wierstra, D. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Tanmay, A. On-Policy Reinforcement Learning for Learning to Drive in Urban Scenarios. Master’s Thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. Multi-Agent Deep Q Network to Enhance the Reinforcement Learning for delayed reward system. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).