Abstract

Deep learning (DL), a hierarchical feature extraction method, has garnered increasing attention in the remote sensing community. Recently, self-supervised learning (SSL) methods in DL have gained wide recognition due to their ability to mitigate the dependence on both the quantity and quality of samples. This advantage is particularly significant when dealing with limited labeled samples in hyperspectral images (HSIs). However, conventional SSL methods face two main challenges. They struggle to construct self-supervised signals based on the unique characteristics of HSI. Moreover, they fail to design network optimization strategies that leverage the intrinsic manifold geometry within HSI. To tackle these issues, we propose a novel self-supervised learning method termed Manifold Geometry-Leveraged Self-supervised Learning (MSSL) for HSI classification. The approach employs a two-stage training strategy. In the initial pre-training stage, it develops self-supervised signals that exploit spatial homogeneity and spectral coherence properties of HSI. Furthermore, it introduces a manifold geometry-guided loss function that enhances feature discrimination by increasing intra-class compactness and inter-class separation. The second stage is a fine-tuning phase utilizing a small set of labeled samples. This stage optimizes the pre-trained model, enabling effective feature extraction from hyperspectral data for classification tasks. Experiments conducted on real-world HSI datasets demonstrate that MSSL achieves superior classification performance compared to several relevant state-of-the-art methods.

1. Introduction

Imaging spectroscopy in Earth observation plays a pivotal role in efficiently comprehending land surface cover. It is a crucial means for geospatial applications such as urban planning, mineral exploration, and precision agriculture [1,2,3]. In recent years, the use of remote sensing imagery for land cover information acquisition has emerged as a research hotspot [4,5]. Hyperspectral imagery (HSI) possesses not only spatial information but also rich spectral properties of land covers [6]. It can invert the land object categories of each component pixel by leveraging the unique spectral curve characteristics of different materials, such as agricultural land, residential land, roads, and water bodies. This process provides effective technical support for the fine classification of ground objects [7,8]. However, due to high inter-band correlations within the spectral domain, HSI exhibits substantial information redundancy. This not only consumes extensive computational resources but also potentially degrades classification accuracy [9,10,11]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to derive discriminative features from the abundant spectral band information of HSI for classification.

After preprocessing steps such as geometric correction, feature extraction becomes the focus of hyperspectral data classification tasks [12]. Feature extraction is crucial for providing highly discriminative and low-redundancy information to classifiers. It plays a key role in reducing computational costs and achieving significant classification performance [13,14,15]. Over the past decade, numerous classical feature extraction algorithms have been developed. Among them, subspace methods learn feature mapping relationships using data statistical properties, retaining the intrinsic information in the subspace. Related algorithms include Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [16], Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [17], and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [18]. However, research has indicated that the spectral curves of objects display nonlinear characteristics and possess manifold geometric structures due to the influence of the external environment during hyperspectral imaging. These linear subspace approaches focus on statistical properties and ignore the inherent nonlinear structural relationships within HSI. Consequently, various manifold learning approaches have been proposed for revealing inherent geometric structures within hyperspectral data. These methods analyze data either on or adjacent to the manifold in the original space, such as Locality Preserving Projection (LPP) [19], Local Geometric Structure Fisher Analysis (LGSFA) [20], and Neighborhood Preserving Embedding (NPE) [21]. Nevertheless, these traditional feature extraction approaches rely on shallow-level feature descriptors and cannot capture higher-level abstract representations that handle nonlinear relationships in complex scenes.

Deep learning methods excel in learning complex nonlinear relationships through multi-layer networks, demonstrating outstanding performance in image classification and object recognition [22,23,24]. Simultaneously, light scattering effects between objects and distinct atmospheric scattering conditions may distort spectral characteristics of objects [25]. Deep learning methods generate more abstract and robust higher-level feature representations through hierarchical feature extraction, enhancing the generalization capabilities of the models [26,27,28]. This capability has popularized deep learning methods in feature extraction and classification tasks of HSI. Representative methods include Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [29], Deep Belief Networks (DBNs) [30], Manifold-based Multi-DBN (MMDBN) [31], 1-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1DCNN) [32], 2-Dimensional CNN (2DCNN) [33], 3-Dimensional CNN (3DCNN) [34], and mini-batch Graph Convolutional Network (miniGCN) [35]. Among them, miniGCN employs a small batch strategy to optimize large-scale graph convolutional neural networks, delivering enhanced diversity and discriminative capability in feature representations for HSI classification applications. However, despite promising classification results, these deep learning methods still struggle to adequately represent spectral sequence information and capture subtle spectral differences.

In recent years, Transformer networks, initially designed for natural language processing tasks, have attracted considerable interest in image processing [36,37]. Several Transformer-based models have been introduced in HSI classification tasks [38]. These models effectively overcome the constraints of conventional deep learning methods in exploring long spectral sequences and modeling sequence information [39]. For instance, Vision Transformer (ViT) achieves classification by extracting effective features from long-range spectral relationships and integrating them with Multi-layer Perceptrons (MLP) [40]. The spatial-spectral Transformer (SST) model employs a convolutional neural network architecture for spatial feature extraction. It then learns the sequential relationship between adjacent bands through a multi-layer Transformer network and employs an MLP to derive classification results [41]. The SpectralFormer model, also based on Transformers, learns spectral feature representations from adjacent bands. It adaptively learns inter-layer fusion residuals by constructing a cross-level Transformer encoder module, thereby minimizing information loss [42]. However, despite the significant advantages of the aforementioned deep learning models in feature extraction through hierarchical networks, they necessitate extensive labeled samples for training. Insufficient training samples and weakly discriminative object features may cause these models to converge to local optima, potentially compromising their accuracy and generalization capabilities.

Self-supervised learning (SSL) strategies overcome the limitations imposed by labeled samples, effectively leveraging extensive unlabeled data for model training. These approaches optimize models through pseudo-label construction and explicit learning signals, which ensures a robust correlation between the extracted features and the target task [43]. Self-supervised contrastive learning (SSCL) leverages contrastive learning (CL) principles to identify positive and negative sample relationships, serving as a pretext task within the self-supervised training framework [44]. The resulting pre-trained model is subsequently transferable to downstream classification problems, often yielding significant improvements in performance. However, current approaches rely on traditional data augmentation techniques, including scaling, rotation, cropping, and translation operations, for generating positive and negative sample pairs within self-supervised signals. This practice may disrupt the continuity of spectral bands and hinder the effective utilization of sequence information. Furthermore, they neglect the exploration of the intrinsic manifold geometric structure within hyperspectral data, thereby constraining discriminative features that can be extracted.

To tackle the aforementioned drawbacks, a novel self-supervised learning method named Manifold Geometry-Leveraged Self-supervised Learning (MSSL) is proposed. MSSL employs a two-stage model training process, starting with a self-supervised model pre-training phase. This phase utilizes the spatial homogeneity and spectral similarity properties of HSI. It aims to develop a self-supervised signal construction method that aligns with the characteristics of hyperspectral data. This approach avoids the destruction of spectral information often caused by traditional data augmentation methods. Additionally, MSSL incorporates a manifold geometry-guided contrastive loss function that mines the inherent manifold geometric structure within HSI. By leveraging the geometric structural information among samples, including their positive and negative pairs, the method enhances intra-class compactness and inter-class separation. This process improves the discriminability of the extracted features. The second stage involves model fine-tuning, wherein a limited quantity of labeled samples is employed to optimize model parameters and enhance the feature extraction capabilities. It is noteworthy to emphasize several advantages of MSSL compared to existing methods.

- MSSL introduces a self-supervised signal construction method specifically designed for hyperspectral data characteristics. It leverages the spatial homogeneity and spectral similarity of HSI to select positive and negative samples. As a result, it preserves spectral information integrity, avoiding the potential distortions caused by conventional data augmentation techniques.

- By combining manifold learning with self-supervised learning, MSSL formulates a manifold geometry-guided contrastive loss function. This function investigates the inherent manifold geometric structure of HSI. It decreases the proximity among positive sample pairs and simultaneously increases the separation among negative sample pairs. Consequently, the model enhances its ability to discriminate between sample categories and to learn the corresponding mapping function.

- The manifold geometry-leveraged self-supervised learning strategy optimizes model parameters through a two-stage learning process: pre-training and fine-tuning. This approach leverages both unlabeled and labeled data effectively.

- MSSL underwent rigorous qualitative and quantitative evaluation of its classification performance across three representative datasets. Empirical findings reveal that MSSL effectively exploits information from unlabeled samples, yielding superior performance metrics compared to existing methods.

The subsequent sections are organized as follows. An overview of Transformer and self-supervised learning is provided in Section 2. Section 3 elaborates on the proposed MSSL methods. Section 4 performs comprehensive experimental validation to demonstrate the efficacy of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 5 summarizes this work.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Brief Review of Transformers

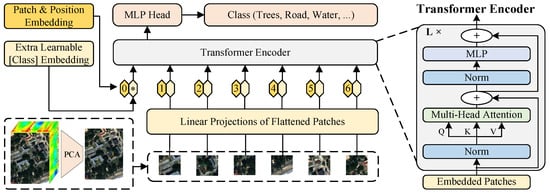

Transformers, a pivotal innovation in sequence modeling, have revolutionized multifarious research domains encompassing natural language processing (NLP) and computer vision (CV) [36]. By introducing the self-attention mechanism, they overcome the sequential constraints of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), allowing the acquisition of long-range dependencies and comprehensive contextual information within sequences [45,46,47]. The Vision Transformer (ViT), which adapts Transformer frameworks for vision tasks, represents a significant advancement in computer vision. Unlike RNNs that process images sequentially or through specialized convolutional operations, ViT treats images as sequences of patches. This allows for the direct application of the self-attention mechanism within the Transformer architecture to capture global dependencies among image patches. The schematic diagram of ViT is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram of ViT (“*”: extra learnable class embedding, for global feature aggregation in classification).

The fundamental architecture of Transformer models, including ViT, is centered around their self-attention mechanism. This mechanism allows each element in the sequence to dynamically attend to all other elements, effectively capturing complex long-range dependencies. Concretely, the self-attention mechanism can be operationalized according to the subsequent six operations.

- Input Sequences: An input sequence x of length m containing scalar or vector elements .

- Feature Embedding: Feature embeddings for each are computed using a shared transformation matrix W.

- Query, Key, Value Calculation: The embeddings are transformed into query (Q), key (K), and value (V) vectors through linear projections.

- Attention Computation: Attention scores are calculated based on dot product of Q and K, followed by scaling normalization.

- Softmax Activation: The softmax function is applied to obtain normalized attention weights.

- Attention Representation Generation: Attention representations z are computed using a weighted sum of values V based on normalized weights.

The self-attention mechanism is mathematically expressed as follows:

where d denotes the dimensionality of K and Q, and the scaling factor avoids the dot product from growing excessively large, which would otherwise lead to extremely small gradients in the softmax function.

This adaptation of the Transformer architecture in ViT showcases its versatility across diverse domains. It highlights the departure from traditional RNN-based approaches in computer vision tasks. In conclusion, Transformers and their variants have demonstrated effectiveness in capturing global dependencies across sequences, across diverse fields including NLP or CV tasks, thereby transcending the inherent sequential processing constraints of RNNs.

2.1.2. Self-Supervised Learning

Self-supervised learning (SSL) represents a pivotal methodology in machine learning, offering a paradigm shift by allowing models to autonomously extract intricate representations from extensive unlabeled data [48,49]. This approach contrasts with supervised methods, presenting an innovative avenue to leverage intrinsic data structures and relationships during the training process.

The implementation of SSL involves a systematic series of essential steps. First, the input data undergoes data augmentation to generate multiple interrelated samples. These samples are subsequently used to construct pairs, with similar samples serving as positive pairs and dissimilar samples as negative pairs. Second, similarity metrics between samples are calculated, and then a contrastive loss function is applied. This function optimizes the consistency between positive pairs while reducing similarity among negative pairs.

The robustness and efficacy of SSL in deriving complex representations from unlabeled data enable the extraction of comprehensive and generalized features. These features provide a foundation for various downstream tasks.

2.2. Related Work Related Work

Building on the theoretical background of Transformers, notable efforts have adapted this architecture for hyperspectral image (HSI) classification to address limitations of CNNs and Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) in modeling spectral sequence dependencies, particularly their inability to capture fine-grained inter-band correlations. Among these, Hong et al. proposed SpectralFormer, a pure Transformer architecture tailored explicitly for HSI tasks. Distinct from CNN-Transformer hybrid models, it employs a sequential learning paradigm that leverages the Transformer’s inherent strength in modeling long-range dependencies across spectral bands while avoiding the local inductive bias of convolutional operations.

SpectralFormer integrates two key innovations for hyperspectral data characteristics. The Group-wise Spectral Embedding (GSE) module learns local spectral representations from neighboring bands instead of individual bands. For a spectral signature , GSE performs an overlapping grouping operation to generate grouped spectral vectors , where each grouped vector (with n denoting the number of neighboring bands) consists of and its adjacent bands, i.e., to . Local embeddings are then computed as , where is the linear transformation matrix and denotes the GSE output. This design preserves fine-grained spectral correlations that standard Transformers overlook when treating individual bands as independent tokens.

The Cross-layer Adaptive Fusion (CAF) module mitigates information loss in deep network propagation via middle-range skip connections. For outputs of the l-th and -th layers and , CAF adaptively fuses these two-layer features using the learnable parameter , resulting in the fused feature. This skip-one-encoder design balances semantic gap reduction and information preservation, avoiding insufficient fusion of long-range skip connections and limited memory of short-range ones. Experimental evaluations on benchmark HSI datasets demonstrate that SpectralFormer outperforms CNN-based and GCN-based baselines, with an overall accuracy improvement over miniGCN on the Indian Pines dataset, but is limited by adjacent band grouping when capturing non-local spectral dependencies in complex mixtures.

3. Proposed Approach

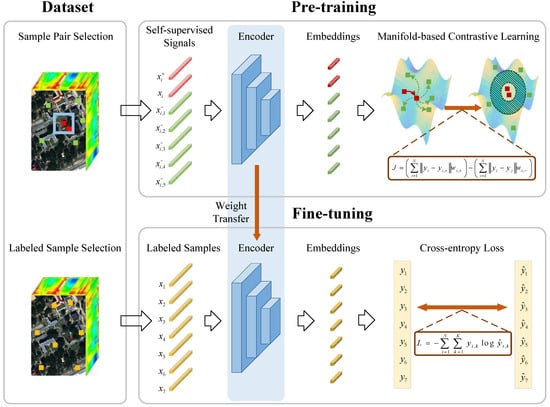

Hyperspectral images exhibit spatial consistency among adjacent pixels and spectral similarity for the same type of land cover. However, traditional self-supervised learning methods ignore these characteristics and fail to construct effective self-supervised signals for hyperspectral images. Additionally, the intrinsic nonlinear manifold geometric structure has been identified in HSI, but traditional self-supervised learning methods cannot enhance feature separability by exploring this structure during the process of maximizing positive sample similarity and minimizing negative sample similarity. To resolve this issue, we propose a new self-supervised learning method called MSSL. MSSL constructs self-supervised signals tailored to hyperspectral images by leveraging their spatial and spectral characteristics. It avoids the disruption of spectral sequence information caused by traditional self-supervised signal construction strategies. Furthermore, MSSL introduces the exploration of such manifold geometric structures. It maintains the local geometric properties of hyperspectral images within low-dimensional space, thereby achieving the extraction of intrinsic features. The Schematic representation of the proposed MSSL is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the manifold geometry-leveraged self-supervised learning (MSSL).

For mathematical clarity and consistency, essential symbols utilized throughout this work are introduced preliminarily. Let the HSI dataset be mathematically formulated as , where N denotes the overall count of samples, while every sample consists of D bands. represents the category label of , with C representing the number of classes in HSI.

3.1. Self-Supervised Signal Construction Strategy for HSI

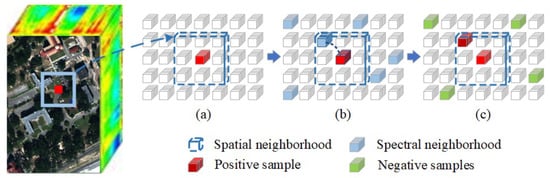

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has achieved remarkable results in image processing applications, particularly in learning useful feature representations without labeled data. However, most current methods heavily rely on traditional data augmentation strategies to construct positive and negative sample pairs as self-supervised signals. For example, after dimensionality reduction of HSI using PCA, traditional SSL methods apply geometric transformations such as rotation and cropping operations on the resulting lower-dimensional HSI. These techniques are similar to those used for RGB images to construct self-supervised signals. Although these approaches are convenient, they exhibit significant limitations in exploiting the rich spectral characteristics inherent in HSI, often compromising the integrity of critical spectral information. To overcome this challenge, we propose a self-supervised signal construction strategy specifically designed for HSI. This strategy takes into account the spatial consistency among adjacent pixels and the spectral similarity of the same type of land cover in hyperspectral data. By leveraging these characteristics, the strategy constructs positive and negative sample pairs to capture intrinsic information in HSI. The schematic diagram of the self-supervised signal construction strategy is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Self-supervised signal construction strategy. (a) Spatial neighbors acquisition. (b) Spatial-spectral joint neighbors construction. (c) Positive sample and negative samples determination.

Spatial consistency refers to the continuity and uniformity in the spatial distribution of adjacent pixels within an image. For HSI, this means that spatially adjacent or clustered sample points are likely to belong to the same land cover type [50,51]. Therefore, leveraging the spatial relationships of pixels in the construction of self-supervised signals can improve the accuracy of generating positive and negative samples. For a sample , assuming are its spatial coordinates, and (where r is a positive odd number) is the size of the spatial neighborhood window, the spatial neighborhood set centered at can be represented as follows:

where .

Spectral similarity refers to the phenomenon where substances exhibit corresponding specific spectral characteristics in different bands. The spectral characteristics of the identical substance typically demonstrate high degrees of similarity. This similarity can be quantitatively assessed by calculating the distance between different samples.

For the neighborhood space of sample , Euclidean distances between each sample within the region and are calculated to measure the similarity of their spectral characteristics. Subsequently, the distance values are ordered in ascending sequence, allowing the identification of the spatial-spectral joint neighbors of within the specified region, denoted as follows:

Considering that the initial sample in the collection not only shares spatial proximity with the target sample but also exhibits the highest spectral similarity, it is designated as the positive sample for the target sample.

After obtaining the spatial-spectral joint neighbor as the positive sample for , the method proceeds to randomly choose a specified quantity of samples from the HSI as negative examples for . The selection of negative samples must satisfy the following conditions:

With the positive and negative samples constructed as described, the self-supervised signals can be obtained for the self-supervised learning process.

3.2. Manifold Geometry-Guided Contrastive Learning

During the self-supervised learning process, a manifold geometry-guided contrastive learning method is proposed to extract discriminative representations through leveraging intrinsic manifold geometric structure within HSI. HSI data typically consist of tens to hundreds of spectral channels. The feature extraction process through neural networks can be conceptualized as capturing the intrinsic characteristics of HSI within a low-dimensional embedding space. This process systematically explores the manifold geometric structure through preserving local geometric relationships among samples. Assuming that MSSL is an L-layer network, the functional mapping applied to the i-th sample at the l-th layer () produces the feature representation .

For investigating the intrinsic structure information in HSI, a manifold geometry-guided contrastive loss function is designed to maintain local geometric relationships between samples during feature mapping. Given that and represent self-supervised signals in HSI, MSSL seeks to preserve the structural dependency between and (hereafter simplified as and ). To mathematically encode the discriminative manifold geometric structure, MSSL constructs a positive graph and a negative graph . The edge weights in contain a single non-zero value, which is the weight of the edge between and , denoted as . Correspondingly, edge weights in are denoted as . These weight parameters are determined by the following mathematical formulation:

where and the heat kernel parameter is defined as and , and means the negative sample size.

MSSL aims to learn effective data representations by exploring manifold geometric structural relationships during contrastive learning, simultaneously minimizing distances between positive samples and enlarging those among negative samples. Therefore, the composite loss function is defined as follows:

Equation (7) can be reduced with some algebraic manipulation to the following:

where , , , .

Based on the manifold geometry-guided contrastive loss derivation, MSSL employs stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimization with an iterative strategy to update network parameters. The partial derivative of the objective function J, taken with regard to the weight matrix of layer l, is given by the following:

where means the mapping matrix associated with the l-th computational layer.

Through designing a manifold geometry-guided contrastive learning method, target samples and their positive counterparts achieve enhanced feature space compactness, while maintaining increased separation from negative samples. This improved feature discrimination enables the model to distinguish different types of ground cover.

3.3. Model Training Process

MSSL implements a two-stage learning architecture consisting of pre-training and fine-tuning phases. This design optimizes structural information extraction from unlabeled data while effectively utilizing limited labeled samples for task-specific optimization. The methodology centers on manifold geometric structure exploration during pre-training, followed by discriminative feature enhancement during fine-tuning to improve classification accuracy.

Pre-training phase. MSSL implements a self-supervised signal construction strategy specifically tailored for hyperspectral data, which facilitates the generation of positive and negative samples. This approach supports the learning of inherent characteristics of various land covers through a novel manifold geometry-guided contrastive learning method. This method operates independently of external labels, thereby improving the capacity of the model to extract the discriminative features.

Fine-tuning phase. MSSL optimizes the network parameters obtained during the pre-training stage. The framework incorporates and optimizes a new fully connected layer appended to the network terminus for implementing the classifier function. The layer-by-layer feature mapping relationship within the network, learned during the pre-training phase, serves as prior knowledge to help the model learn effectively on limited labeled data. Specifically addressing the prevalent label scarcity challenge in hyperspectral analysis, this stage effectively overcomes overfitting and obtains higher classification performance.

The procedural details of the MSSL algorithm are outlined in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 MSSL. |

|

4. Experiment Results and Analysis

4.1. Datasets

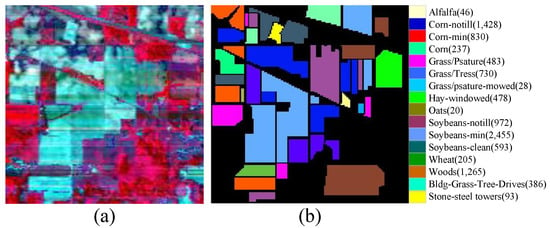

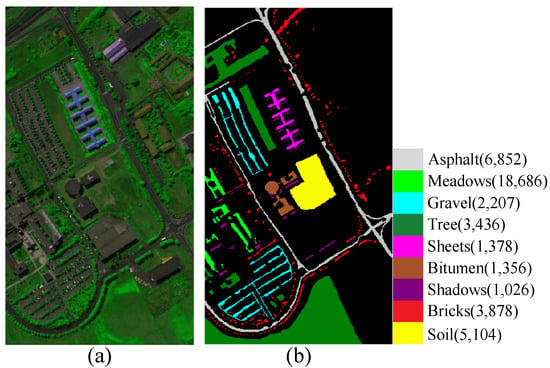

IndianPines Dataset: The first HSI dataset was obtained in 1992 employing the AVIRIS sensor (NASA, Washington, DC, USA) above an agricultural zone in Northwestern Indiana, USA. This imagery contains pixels with 20 m ground sampling distance, originally comprising 220 spectral channels. After removing 20 channels impacted by atmospheric absorption and water vapor interference, 200 radiometrically calibrated bands remain available. The study area contains 16 distinct land cover classes, with Figure 4 illustrating the pseudo-color map and ground truth containing detailed information. Parenthetical annotations indicate sample counts per class.

Figure 4.

IndianPines hyperspectral dataset visualization. (a) HSI in pseudo-color; (b) ground-truth map.

PaviaU Dataset: This dataset, widely adopted in HSI research, was acquired using the ROSIS sensor (German Aerospace Center, Wessling, Germany; GKSS Research Center, Geesthacht, Germany; Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm GmbH, Ottobrunn, Germany) at the University of Pavia, Italy. The image comprises pixels and includes 115 spectral channels covering the wavelength interval of 0.43–0.86 μm. Following elimination of water absorption wavelengths, 103 radiometric bands were retained for experimental purposes. The dataset encompasses nine distinct types of land cover. Figure 5 presents the composite color representation alongside the associated reference data.

Figure 5.

PaviaU hyperspectral dataset visualization. (a) HSI in pseudo-color; (b) ground-truth map.

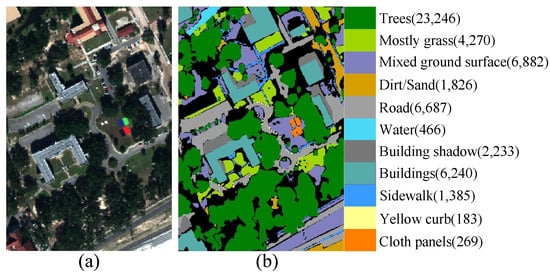

MUUFL Gulfport Dataset [52]: The dataset was collected via the ITRES CASI-1500 sensor (ITRES Research Ltd., Calgary, AB, Canada) over the Gulf Park Campus, University of Southern Mississippi, Gulfport, MS, USA. This 1-m resolution image captures pixels across 64 spectral bands, representing 11 complex urban land use types. Additional comprehensive details regarding this dataset are detailed in Figure 6. In subsequent sections of this article, this dataset will be referred to as MGP for brevity.

Figure 6.

MGP hyperspectral dataset visualization. (a) HSI in pseudo-color; (b) ground-truth map.

4.2. Experimental Setup

For each experiment, a randomly chosen 30% of samples from each HSI dataset were allocated to the pre-training phase. During the fine-tuning phase under supervised learning, the data were divided into training and testing subsets.

4.2.1. Evaluation Metrics

The classification performance is evaluated through four established metrics that are widely adopted as standard benchmarks in HSI classification tasks. These metrics provide complementary perspectives on algorithmic effectiveness and enable comprehensive assessment of model performance across different evaluation criteria.

Overall Accuracy (OA) quantifies the global classification performance across all test samples:

Per-class accuracy measures the classification performance for individual land cover class i:

Average Accuracy (AA) computes the arithmetic mean of per-class accuracies, providing balanced assessment across all categories:

Kappa coefficient () measures inter-rater agreement while accounting for chance agreement:

where denotes correctly classified samples for class i, represents total reference samples in class i, indicates total classified samples as class i, N is the total number of test samples, and C is the number of classes. OA provides overall performance assessment, per-class accuracy reveals individual class discrimination capability, AA ensures unbiased evaluation across imbalanced datasets, and offers statistical significance by correcting for chance agreement.

4.2.2. Comparison Methods

In experiments, we compared MSSL with several state-of-the-art algorithms, including one subspace method (LDA), one manifold learning method (LGSFA), and four deep learning methods (1DCNN, miniGCN, ViT, and SpectralFormer). To achieve optimal performance for different algorithms, cross-validation is adopted to determine optimal parameters for each method.

- LDA applies Fisher linear discriminant criterion with optimal parameters determined through cross-validation.

- LGSFA utilizes local geometric structure analysis with neighborhood parameter set to .

- 1DCNN employs one-dimensional convolutions with kernel size 128, batch normalization, and ReLU activation.

- miniGCN implements graph convolutional networks with 128 neuron units and k-nearest neighbor adjacency where .

- ViT adopts five transformer encoder blocks specifically configured for hyperspectral image classification.

- SpectralFormer adopts five cascaded transformer encoder blocks with embedded spectrum of 64 units. Each encoder block consists of four-head self-attention layers, MLP components with eight hidden dimensions, and GELU activation.

4.2.3. Implementation Details

The proposed MSSL is architected on the PyTorch 2.0.1 deep learning platform with a systematically designed training protocol. It leverages the transformer encoder architecture consistent with the ViT network. Its backbone consists of five sequential encoder blocks for feature extraction, and these blocks process 64-dimensional features. Each encoder block incorporates a four-head multi-attention mechanism. The optimization process utilizes the Adam algorithm with an initial learning rate of , which undergoes multiplicative decay by a factor of 0.9 upon completion of each decile of the total training epochs. Mini-batch stochastic gradient descent is implemented with a fixed size of 64 samples per iteration to balance computational efficiency and gradient estimation stability. The maximum training duration is set to 400 epochs across all experimental datasets to ensure complete model convergence. All computational experiments are executed on a dedicated workstation equipped with an Intel i7-6850K central processing unit, 128 GB DDR4 memory, and an NVIDIA GTX 1080Ti graphics processing unit with 11 GB VRAM. This hardware configuration provides the necessary computational throughput for large-scale hyperspectral data processing while maintaining experimental reproducibility.

4.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the contribution of model parameters to MSSL capability, we conducted extensive experimental studies applying the IndianPines dataset within this subsection. During the fine-tuning phase, 50 samples per class were randomly sampled as the training set, while the rest were allocated for testing. For minor classes such as Grass/pasture-mowed, Alfalfa, and Oats, which are characterized by limited labeled samples, the number of training samples was set to 15 per class to balance sufficient class representation and an adequate test sample size. Additionally, for the training set size experiment, the data division follows the experimental setup.

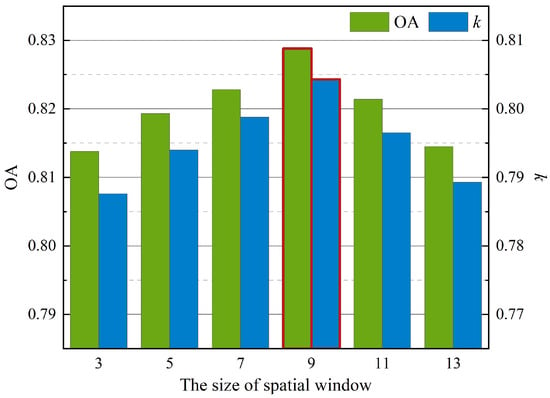

4.3.1. Spatial Neighborhood Window Scale

The spatial window scale r is a critical hyperparameter for self-supervised signal generation, as it directly determines the spatial extent for positive and negative sample selection. In order to choose a suitable r for the proposed approach, experimental trials were executed to investigate the performance of MSSL across different window scales. The parameter r was selected from the set {3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13}. Figure 7 indicates the relationship between r and classification accuracies of MSSL.

Figure 7.

OAs under different sizes of spatial window for MSSL.

Figure 7 reveals that classification accuracy initially improves with increasing window size r, reaching peak performance before exhibiting a gradual decline. This phenomenon arises because increasing r allows more spatial neighbors to be considered in the construction of the self-supervised signal, thereby significantly enhancing the quality of the obtained positive samples. However, excessive window expansion introduces redundant information that saturates discriminative information gains. The optimal balance between feature discriminability and information redundancy is achieved at r = 9.

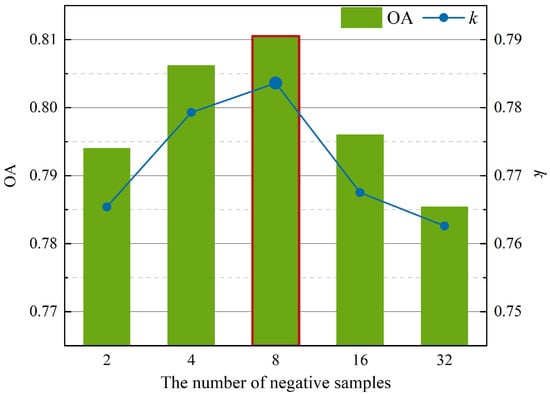

4.3.2. Negative Samples Number with Pre-Training Phase

As an important parameter in contrastive learning, the negative sample quantity significantly influences the efficacy of network parameter optimization during pre-training. The experimental evaluation considered five candidate values ∈{2, 4, 8, 16, 32}. The relationship between OAs of MSSL and different values of is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

OAs under different numbers of negative samples for MSSL.

According to Figure 8, with the increase in the negative samples quantity, the accuracy of MSSL first increases and then rapidly declines. This non-monotonic trend originates from the trade-off between intrinsic and redundant information extraction. With increasing negative sample scale, MSSL gains more effective knowledge to learn the differences between samples and their negative counterparts. However, excessive negative samples introduce spectral-spatial redundancy that diminishes classification discriminability.

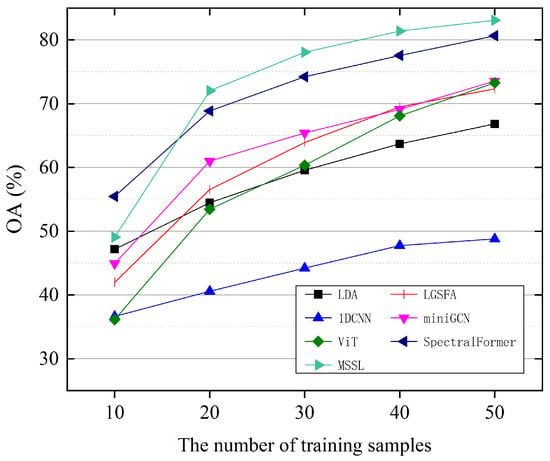

4.3.3. Training Set Size with Fine-Tuning Phase

The scale of labeled training data significantly influences the effectiveness of feature extraction approaches. To assess the performance of MSSL with varying training set sizes during fine-tuning, the number of labeled samples per class () was varied over the set {10, 20, 30, 40, 50}, leaving the remainder for evaluation. Figure 9 presents the OA of MSSL with different .

Figure 9.

OAs under different sizes of training set with fine-tuning phase for MSSL.

Figure 9 reveals that MSSL achieves progressive improvement in OA with increasing . This occurs because a large-scale labeled training set provides richer discriminative knowledge for learning underlying feature representations. However, labeled data for HSI are often insufficient, making it necessary to classify image pixels with a limited number of labeled pixels. MSSL efficiently learns the intrinsic features of hyperspectral data by constructing self-supervised learning signals and designing a manifold geometry-guided contrastive loss function, which holds high application value.

4.4. Ablation Study

To validate the effectiveness of each component in the proposed MSSL framework, comprehensive ablation experiments were conducted on the IndianPines dataset. The ablation study systematically evaluates the contribution of key components by comparing: (1) using only the standard InfoNCE contrastive loss [53], (2) using only the self-supervised signal construction (SSSC) strategy with standard contrastive learning, and (3) the complete MSSL framework combining both the SSSC strategy and manifold geometry-guided contrastive loss (MGCL). The experimental setup follows the same protocol as the parameter sensitivity analysis experiments. Table 1 presents the detailed ablation study results. Specifically, the boldfaced numbers in the table denote the maximum values of the corresponding evaluation metrics, and this formatting convention is consistently applied to all subsequent tables.

Table 1.

Ablation study results on the IndianPines dataset.

In detail, the baseline method that only uses InfoNCE loss without the SSCC and MGCL modules achieves the lowest classification accuracy. This indicates to a certain extent that traditional contrastive learning methods are not fully suitable for hyperspectral image classification. The combination of SSCC and InfoNCE leads to a significant improvement in classification results, demonstrating that constructing self-supervised signals tailored to the characteristics of hyperspectral datasets can effectively enhance the extraction of intrinsic features. Furthermore, introducing MGCL on the basis of the SSCC strategy brings a further notable performance improvement. In other words, the proposed MSSL can capture the intrinsic manifold structure of hyperspectral images by incorporating manifold geometry-guided contrastive learning, thus achieving performance significantly superior to other configurations.

4.5. Comparisons with Other State-of-the-Art Feature Extraction Methods

To validate the significant advantages of MSSL, several state-of-the-art feature extraction algorithms were utilized in comparative analysis.

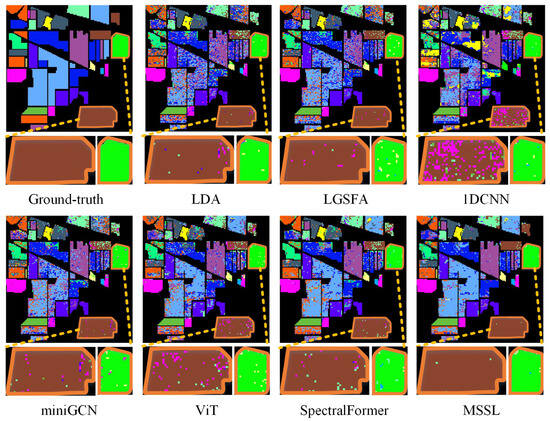

4.5.1. Experiments on the IndianPines

The IndianPines dataset was employed to assess the feature extraction performance of different methods across various land cover categories. To maintain data consistency, the division of training and testing sets was performed following the same protocol as the parameter sensitivity analysis. Quantitative evaluation metrics, including OA, AA, and k, appear within Table 2, whereas visual classification results are displayed through Figure 10.

Table 2.

Per-category classification performance across various algorithms on IndianPines dataset (%).

Figure 10.

Visual classification outcomes through diverse approaches using IndianPines dataset.

As shown in Table 2, the manifold learning method LGSFA achieved better results than the subspace method LDA, due to its consideration of the spatial geometric relationships between samples. Deep learning methods demonstrate superior performance over conventional subspace and manifold learning methods, as hierarchical network structures can learn more intrinsic features of different sample classes. However, 1DCNN exhibits overfitting tendencies on datasets such as IndianPines, which contains hundreds of spectral bands, because it focuses on spectral band relationships and fails to consider the local geometric structure of the samples. SpectralFormer achieves better results than miniGCN and ViT through its integrated analysis of spectral sequence continuity and spatial structure information. MSSL approach achieves competitive results compared to other feature extraction methods. This effectiveness stems from its capability to construct self-supervised signals by jointly exploring spatial and spectral neighborhoods. Simultaneously, the method employs a manifold geometry-guided contrastive loss function to effectively explore the local geometric relationships in sample distributions. Additionally, the optimization of the network structure enhances the ability to extract intrinsic features.

Furthermore, Figure 10 corroborates the numerical results through the visual classification outcomes. MSSL generates smoother classification maps with notably fewer misclassified points compared to other methods, particularly evident in the outlined regions. This is attributed to MSSL effectively learning the intrinsic information from various land cover types. It constructs self-supervised signals tailored for hyperspectral data and extracts high-level features of different samples via a hierarchical network. For datasets with complex land cover types, such as IndianPines, MSSL can more effectively learn the differences between various types.

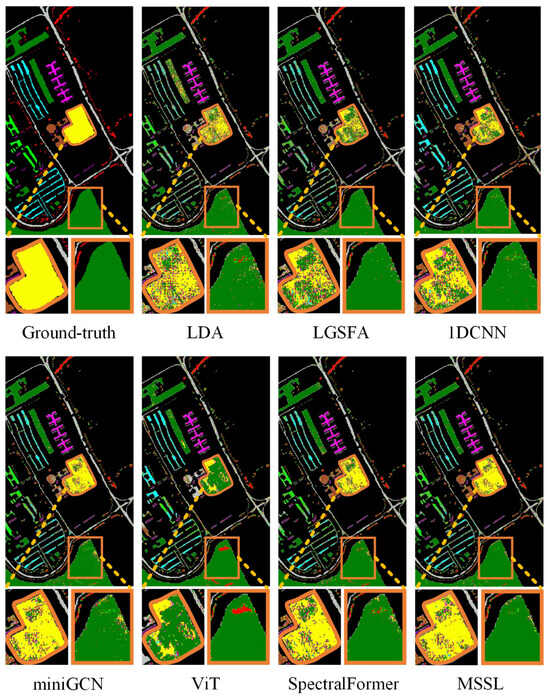

4.5.2. Experiments on the PaviaU

To further validate the efficacy of MSSL, the PaviaU dataset was introduced for quantitative experimental analysis, and classification maps were generated for visual assessments. A randomly chosen 2% of labeled data constituted the training set, with the complement allocated to testing. The corresponding experimental results are presented in Table 3 and Figure 11.

Table 3.

Per-category classification performance across various algorithms on PaviaU dataset (%).

Figure 11.

Visual classification outcomes through diverse approaches using PaviaU dataset.

As shown in Table 3, the manifold learning approach outperforms the subspace method on the PaviaU dataset. However, deep learning methods do not exhibit significant advantages over the manifold learning approach in this case. This is because 1DCNN focuses on exploring the relationships between spectral bands but fails to adequately learn spatial structural relationships. Consequently, it produces poor classification results for land cover types like trees, which have large homogeneous areas. Additionally, the heterogeneity of samples within categories like Gravel impairs the ability of ViT to learn sufficient discriminative information for classification. MSSL yields optimal OA, AA, and k, exhibiting superior classification performance across multiple categories. This is attributed to its ability to construct self-supervised signals through joint exploration of spatial and spectral neighborhoods, while optimizing the correlation between positive sample pairs while reducing the similarity between negative sample pairs through a manifold geometry-guided contrastive loss function. Furthermore, as illustrated in Figure 11, MSSL generates classification maps with larger homogeneous regions and achieves optimal results across several categories by effectively leveraging the local geometric structural relationships inherent in HSI.

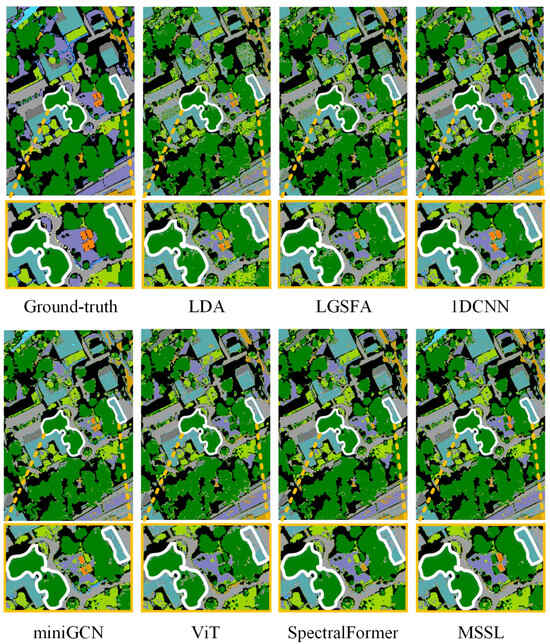

4.5.3. Experiments on the MGP

The MGP dataset was employed to evaluate the performance of different algorithms for each land cover type. A randomly chosen 1% of the labeled data in each class comprised the training set, with the remaining samples were formed to constitute the test set. The quantitative results from diverse approaches are summarized in Table 4, and Figure 12 displays the corresponding classification maps.

Table 4.

Per-category classification performance across various algorithms on MGP dataset (%).

Figure 12.

Visual classification outcomes through diverse approaches using MGP dataset.

As presented in Table 4, the experimental results show that deep learning methods have a significant performance advantage over traditional methods, particularly in analyzing the complex urban landscape characteristics of the MGP dataset. Deep learning can learn the complex spatial distribution patterns of land cover types with hierarchical networks. The category presents particular classification challenges due to its scattered spatial distribution, with most methods exhibiting limited classification accuracy. However, both 1DCNN and the proposed MSSL achieved breakthrough performance in classifying this category because they fully learned the critical information between spectral bands. MSSL demonstrates superior overall performance, generating classification maps with significantly reduced misclassification errors. The relatively lower AA metric of on the MGP dataset compared to other datasets reflects the inherent complexity of urban hyperspectral classification. This performance is primarily attributed to the high spectral similarity between urban materials, particularly the Building shadow and Sidewalk classes, which leads to frequent misclassification and consequently reduces individual class accuracies that comprise the AA calculation. Furthermore, the complex urban environment characterized by mixed pixels and irregular spatial distributions degrades the quality of self-supervised feature representations, resulting in inconsistent per-class performance across different urban material categories. Since AA computes the arithmetic mean of all per-class accuracies, these classification difficulties in specific urban classes directly lower the overall AA metric. Nevertheless, MSSL demonstrates superior performance by achieving the highest AA among all comparative methods under these challenging conditions. This spatial advantage is visually confirmed in Figure 12, where MSSL not only yields more contiguous boundaries for scattered targets but also generates larger homogeneous regions with fewer misclassified points in complex urban areas, surpassing other methods in spatial consistency. This enhanced performance can be attributed to its pre-training phase, where it constructs effective self-supervised signals and the contrastive loss function based on manifold learning. This approach enhances the affinity between positive pairs while maximizing the divergence among negative pairs, thereby enabling the model to fully explore the intrinsic features for each land cover category and their discriminative differences.

5. Conclusions

In this article, a novel feature extraction method called MSSL is proposed. This approach enhances representational learning capability of the network by exploring the intrinsic manifold geometric structure within HSI.

The approach implements a two-stage learning paradigm. The pre-training phase introduces a self-supervised signal construction strategy specifically designed for hyperspectral data. This strategy exploits two intrinsic properties of HSI: spatial consistency among adjacent pixels and spectral similarity within the same land cover category. These properties jointly facilitate the generation of positive and negative samples. On this basis, the manifold geometric structure is explored to cluster intra-class instances while maximizing inter-class divergence, thereby strengthening the ability of the model in characterizing differences between various types of samples. In the fine-tuning phase, the learned weights of the pre-trained model are preserved, while supervised optimization of these parameters is performed through a limited collection of labeled samples. Experiments on a wide range of hyperspectral datasets show that MSSL significantly outperforms other state-of-the-art feature extraction methods.

Future research will explore cross-data-collection-platform generalization of the MSSL framework through transfer learning techniques. This includes developing domain-adaptive self-supervised mechanisms to mitigate spectral-spatial distribution shifts caused by heterogeneous sensor characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and H.H.; methodology, Z.L.; software, C.G.; validation, Z.L. and C.G.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Z.L. and C.G.; resources, Z.L. and T.W.; data curation, C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L. and C.G.; visualization, C.G.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, Z.L. and T.W.; funding acquisition, Z.L. and H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 42201342 and 42571416.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and associate editor for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhengying Li and Tao Wang are employed by both JD Intelligent Cities Research and JD Technology. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Hong, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, B.; Yokoya, N.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Chanussot, J. Multimodal artificial intelligence foundation models: Unleashing the power of remote sensing big data in Earth observation. Innov. Geosci. 2024, 2, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Du, P. Characterizing Markov Random Fields and Coefficient of Variations as Measures of Spatial Distributions for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 5509705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Artificial intelligence for remote sensing data analysis: A review of challenges and opportunities. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 270–294. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, F.; Zhang, L.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. Dimensionality reduction with enhanced hybrid-graph discriminant learning for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 5336–5353. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Du, Q. Deep Cross-Domain Few-Shot Learning for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5501618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Shi, W.; Xiao, Z.; Ali, T.A.A.; Ye, F.; Jiao, L. Achieving better category separability for hyperspectral image classification: A spatial-spectral approach. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 9621–9635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Hu, J.; Kang, X.; Duan, P.; Li, S. Multilayer global spectral-spatial attention network for wetland hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5518913. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Hong, D.; Chanussot, J. S2MAE: A spatial-spectral pretraining foundation model for spectral remote sensing data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 27696–27705. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Dual selective fusion transformer network for hyperspectral image classification. Neural Netw. 2025, 187, 107311. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.; Zhong, Y. LPCN: Lightweight Precise Classification Network for Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Imagery Based on Multiobjective Optimization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5523514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T. A Multi-Hyperspectral Image Collaborative Mapping Model Based on Adaptive Learning for Fine Classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1384. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, C.; Gao, L.; Zhang, B. Multiscale Residual Network with Mixed Depthwise Convolution for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 3396–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Meng, Y.; Shen, T. DF2Net: Differential Feature Fusion Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 10660–10673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Chen, N.; Peng, J.; Sun, W. A Prototype and Active Learning Network for Small-Sample Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 5510805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, Y. Manifold Learning-Based Semisupervised Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5508712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fan, Y.; Fang, B.; Dai, S. Generalized linear discriminant analysis based on Euclidean norm for gait recognition. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2018, 9, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.-H.; Lu, C.-P.; Wu, D.-C.; Wen, C.-Y. A histogram based data reducing algorithm for the fixed-point independent component analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2008, 29, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyo, J.S.; Konsolakis, A.; Diersen, D.I.; Olsen, R.C. Principal components-based display strategy for spectral imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2003, 41, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Li, H.; Pan, L.; Shao, L.; Du, Q.; Emery, W.J. Modified tensor locality preserving projection for dimensionality reduction of hyperspectral images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Huang, H.; Duan, Y.; Liu, J.; Liao, Y. Local geometric structure feature for dimensionality reduction of hyperspectral imagery. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 6197–6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Jin, Z.; Zou, J. Face recognition using discriminant sparsity neighborhood preserving embedding. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2012, 31, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, G.; Gu, Y. Deep learning-based classification of hyperspectral data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 2094–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Shen, W.; Zhang, Q. Hyperspectral Image Classification Using a Spectral-Cube Gated Harmony Network. Electronics 2025, 14, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez García, J.A.; Lazzeri, G.; Tapete, D. Airborne and Spaceborne Hyperspectral Remote Sensing in Urban Areas: Methods, Applications, and Trends. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3126. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Yao, J.; Yokoya, N.; Li, H.; Ghamisi, P.; Jia, X.; et al. SpectralGPT: Spectral remote sensing foundation model. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 5227–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Shang, X.; Pan, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J. MSFF: A Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Convolutional Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. Electronics 2025, 14, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, S.; Xu, M.; Jia, X. Graph-in-Graph Convolutional Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 1157–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, C.; Liu, Y.; Lin, S.; Shi, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, H. Multimodal Deep Learning for Semisupervised Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2024, 11, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, L.; Ghamisi, P.; Zhu, X.X. Deep recurrent neural networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 3639–3655. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jia, X. Spectral-spatial classification of hyperspectral data based on deep belief network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 2381–2392. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, G. Manifold-Based Multi-Deep Belief Network for Feature Extraction of Hyperspectral Image. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1484. [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti, M.E.; Haut, J.M.; Plaza, J.; Plaza, A. A new deep convolutional neural network for fast hyperspectral image classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 145, 120–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, H. A fast dynamic graph convolutional network and CNN parallel network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5530215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Plaza, A. Gabor-modulated grouped separable convolutional network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5518817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yao, J.; Zhang, B.; Plaza, A.; Chanussot, J. Graph convolutional networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 5966–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhao, Y. WTCMC: A Hyperspectral Image Classification Network Based on Wavelet Transform Combining Mamba and Convolutional Neural Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; He, W.; Zhang, H. Transformer Network with Total Variation Loss for Hyperspectral Image Denoising. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 5503105. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, S.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Cai, H.; Du, Q. Hyperspectral image classification using attention-based bidirectional long short-term memory network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5509612. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, X.; Li, S.; Plaza, A. Hyperspectral Image Classification Using Groupwise Separable Convolutional Vision Transformer Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5511817. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Spatial-spectral transformer for hyperspectral image denoising. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 1368–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.; Han, Z.; Yao, J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, B.; Plaza, A.; Chanussot, J. SpectralFormer: Rethinking Hyperspectral Image Classification with Transformers. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5518615. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Chanussot, J. CTF-SSCL: CNN-transformer for few-shot hyperspectral image classification assisted by semisupervised contrastive learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5532617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Shi, H.; Cao, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, L. Hyperspectral imagery classification based on contrastive learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5521213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z. Spatial-Spectral Transformer for Hyperspectral Image Classification. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Feng, C.; Dian, R.; Li, S. SSTF-Unet: Spatial-Spectral Transformer-Based U-Net for High-Resolution Hyperspectral Image Acquisition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 18222–18236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.K.; Sukul, A.; Jamali, A.; Haut, J.M.; Ghamisi, P. Cross Hyperspectral and LiDAR Attention Transformer: An Extended Self-Attention for Land Use and Land Cover Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5512815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Swersky, K.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. Big self-supervised models are strong semi-supervised learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 22243–22255. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Wei, E.; Wen, Y.; Jiao, L. Cross-Dataset Model Training for Hyperspectral Image Classification Using Self-Supervised Learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5538017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shang, S.; Tang, X.; Feng, J.; Jiao, L. Spectral Partitioning Residual Network with Spatial Attention Mechanism for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5507714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Xue, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, A.; Su, H. Spectral-Spatial Score Fusion Attention Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification with Limited Samples. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 14521–14542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gader, P.; Zare, A.; Close, R.; Aitken, J.; Tuell, G. MUUFL Gulfport Hyperspectral and LiDAR Airborne Data Set; Tech. Rep. REP-2013-570; Dept. CISE, Univ. Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van den Oord, A.; Li, Y.; Vinyals, O. Representation Learning with Contrastive Predictive Coding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.03748. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).