A Novel Decomposition–Integration-Based Transformer Model for Multi-Scale Electricity Demand Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

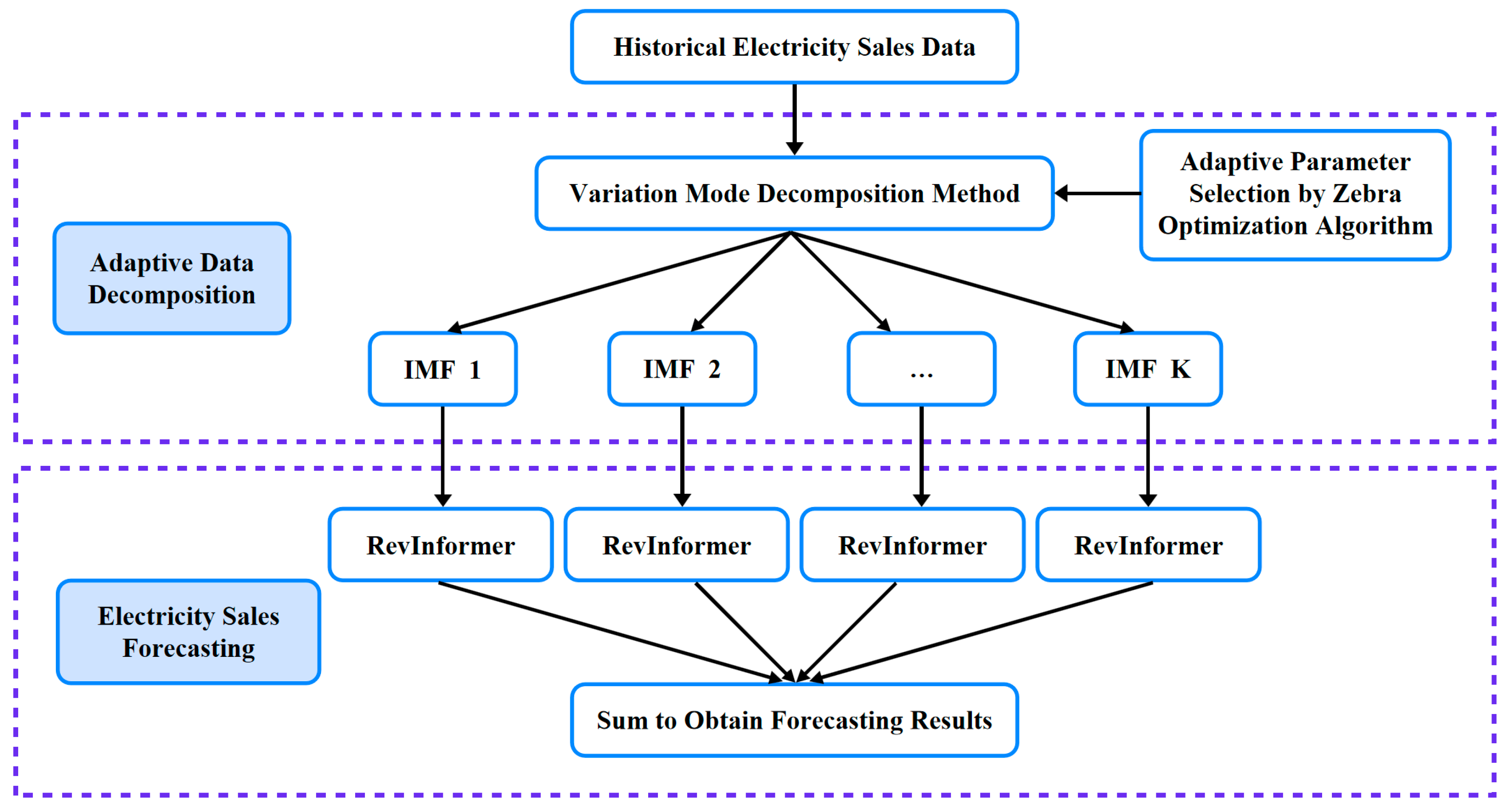

- A novel electricity sales forecasting method is proposed, employing a decomposition–integration framework. This approach adaptively decomposes the original sequence by integrating VMD with the ZOA, thus significantly reducing modeling complexity. Subsequently, an improved RevInformer model performs component-wise prediction on each subsequence, with final forecasts generated through aggregated integration of all component predictions.

- (2)

- An enhanced RevInformer model is developed by introducing Reversible Layers to the Informer architecture, strengthening deep feature propagation capabilities. Simultaneously, a bidirectional modeling mechanism is incorporated, effectively improving modeling capacity and prediction accuracy for complex non-stationary sequences.

- (3)

- The proposed methodology was validated using an annual electricity sales dataset from a commercial building. Simulation results demonstrate that our approach achieves 60–90% improvements across all evaluation metrics, surpassing the performance of existing benchmark methods.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. The Framework for the Proposed Method

3.2. Adaptive Data Decomposition

- (1)

- Insufficient subsequence settings increase reconstruction errors.

- (2)

- Excessive settings substantially escalate computational overhead.

3.2.1. Variational Mode Decomposition

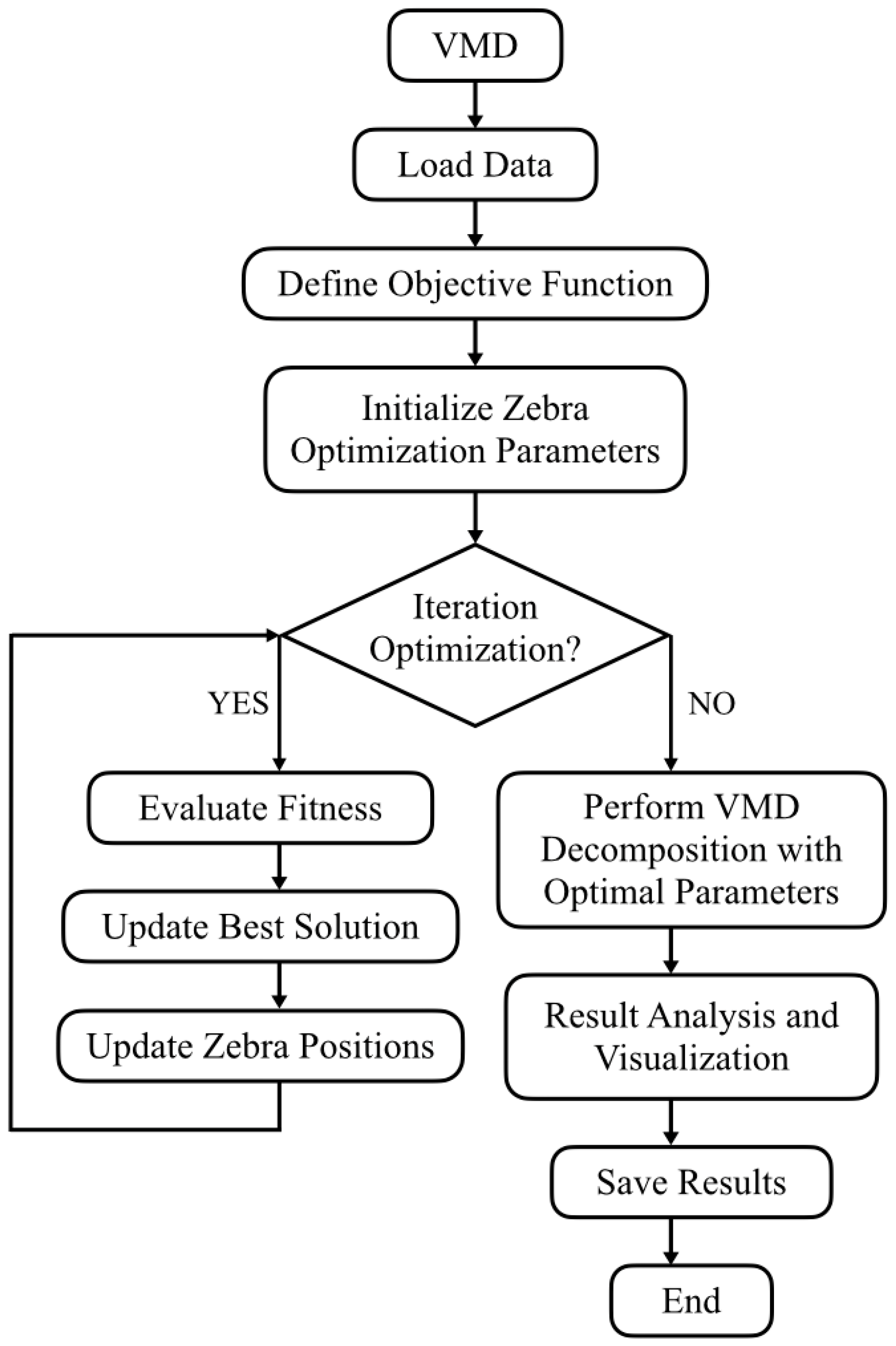

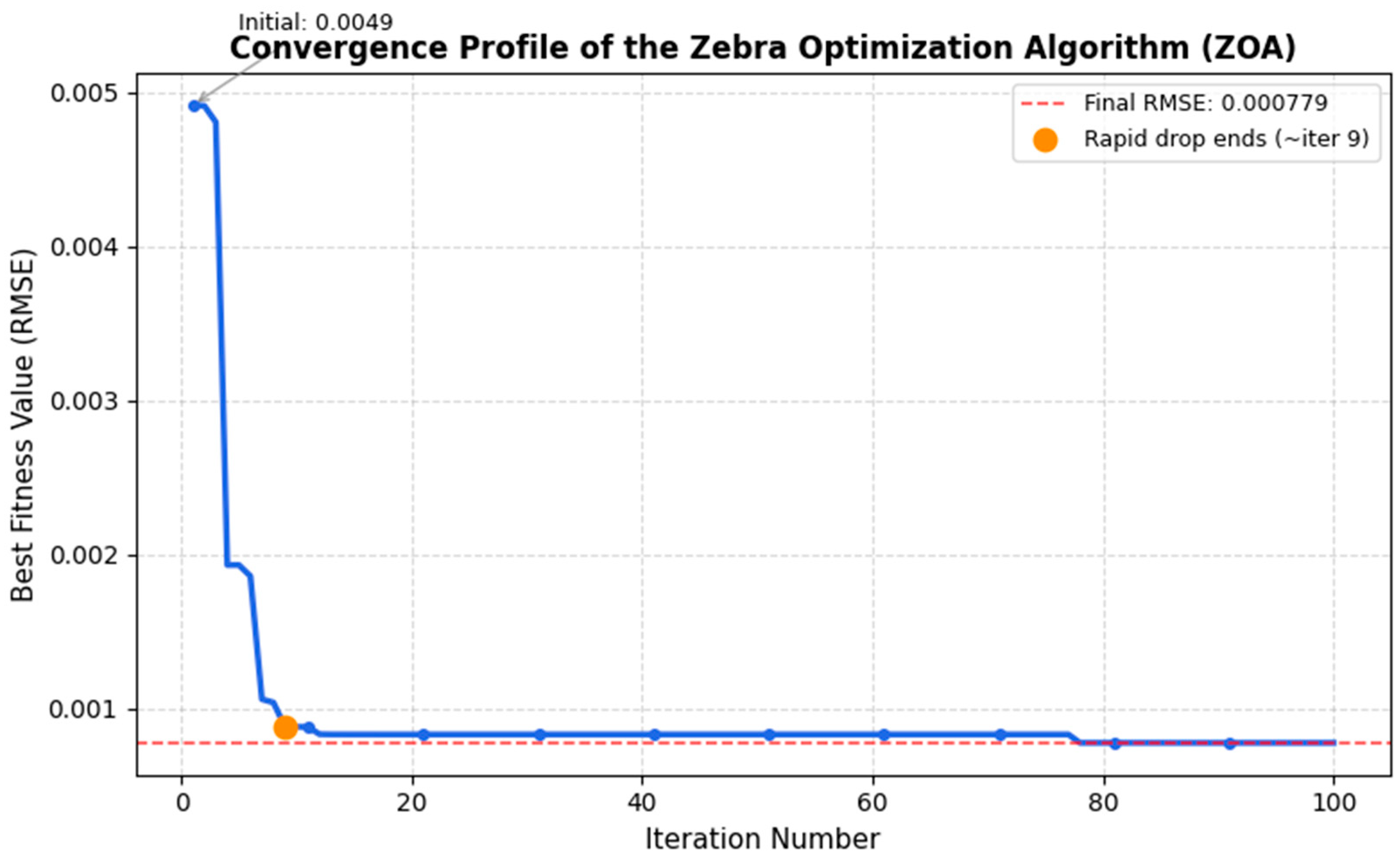

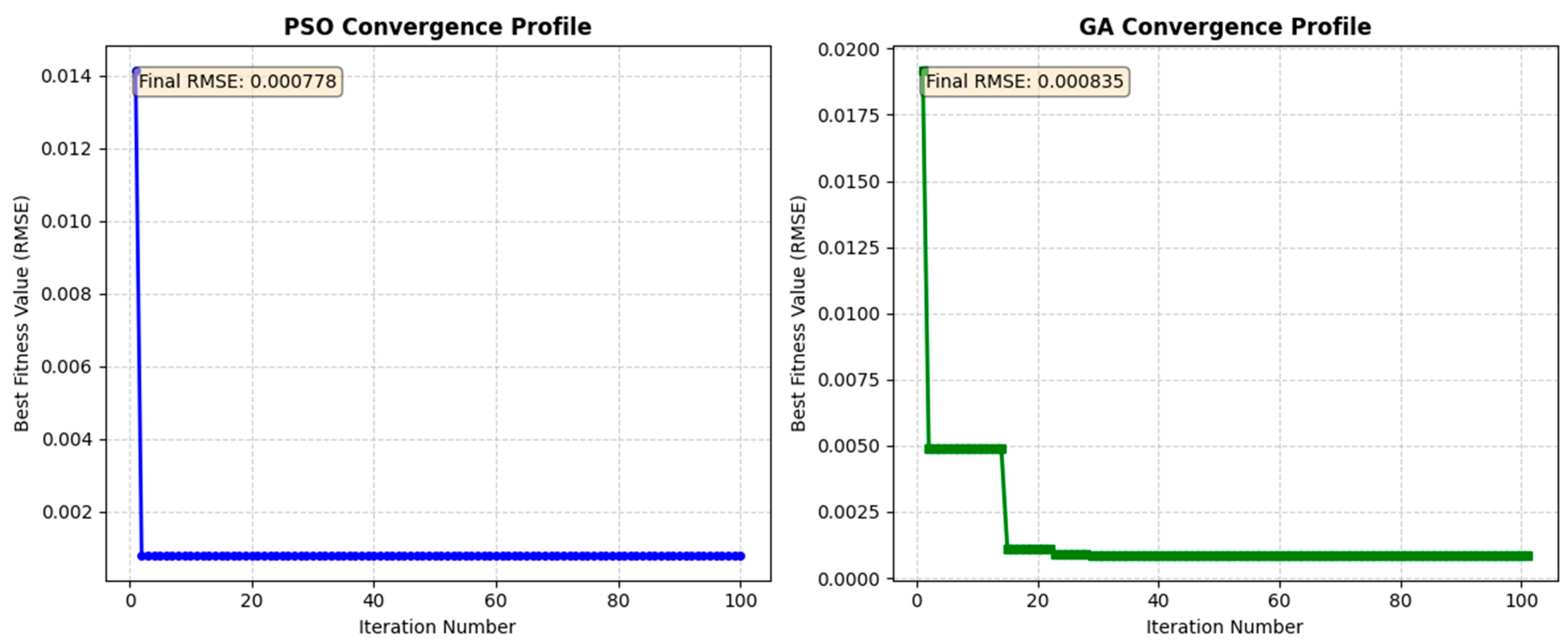

3.2.2. Self-Adaptive Parameter Selection Using Zebra Optimization Algorithm

- (1)

- Initialization: Randomly generate 15 parameter combinations (, ) within predefined bounds.

- (2)

- Iteration: Dynamically adjust combinations toward optimal solutions.

- (3)

- Evaluation: The objective function for the ZOA is RMSE between the original signal f(t) and the sum of all reconstructed IMFs after VMD. The algorithm seeks to minimize this reconstruction error.

- (4)

- Finalization: Deploy the optimal combination (, ) for VMD signal decomposition.

- (1)

- When searching for the optimal solution, ZOA extends its scope to the global range. The exploration phase of ZOA, characterized by long-distance jump properties, enables the algorithm to escape current local optimum regions and expand the search boundary. In contrast, traditional PSO relies on particle historical and social experiences, making it prone to stagnation in current regions and often limiting exploration outcomes to local optima.

- (2)

- As a meta-optimizer, ZOA possesses fewer parameters and a clearer structure, eliminating the need for additional computational overhead to tune its own parameters. However, the GA involves parameters such as crossover rate and mutation rate during the optimization process. Tuning these parameters can compromise the algorithm’s robustness and lead to an “infinite recursion” dilemma.

3.3. Electricity Sales Forecasting

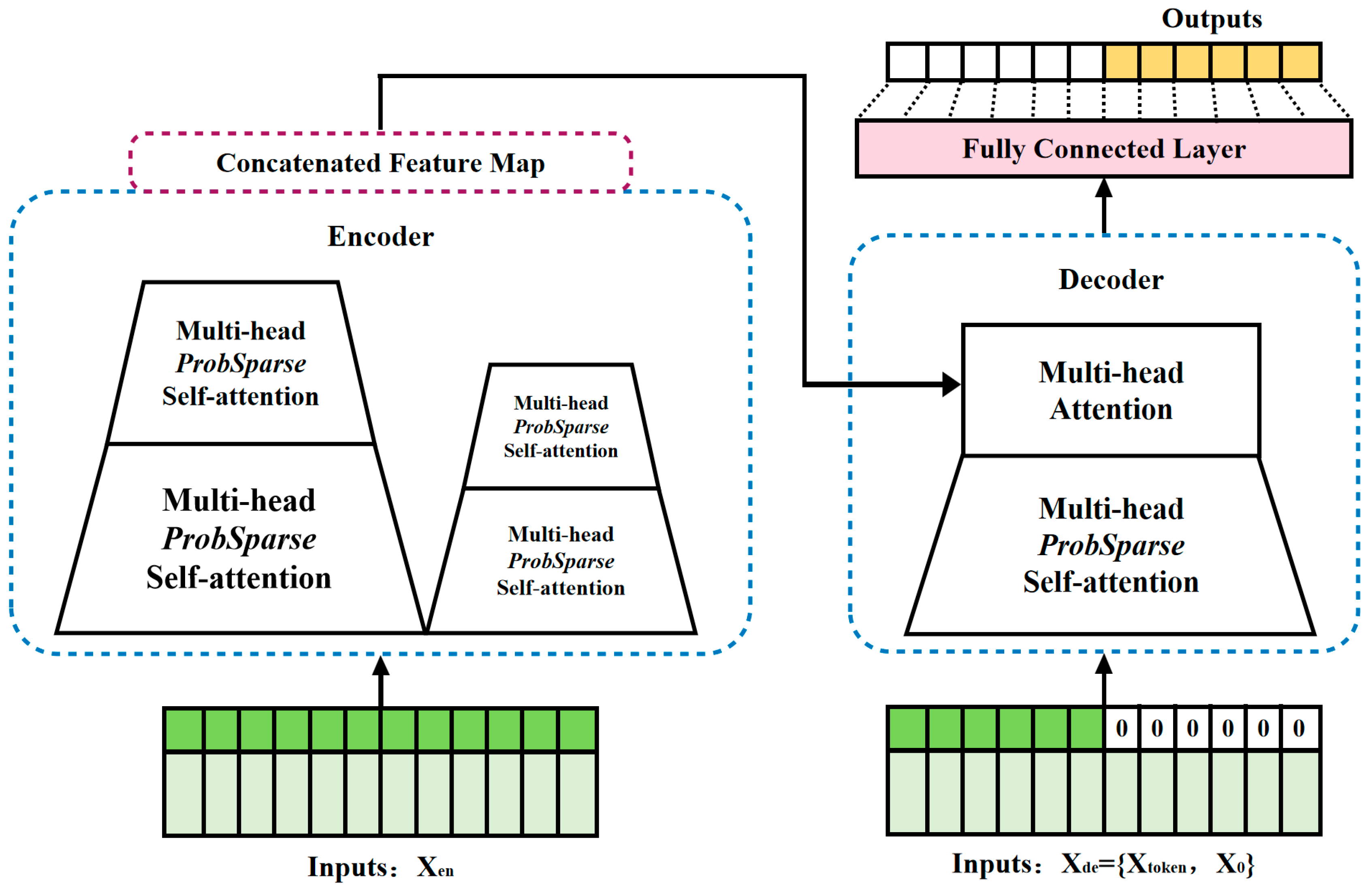

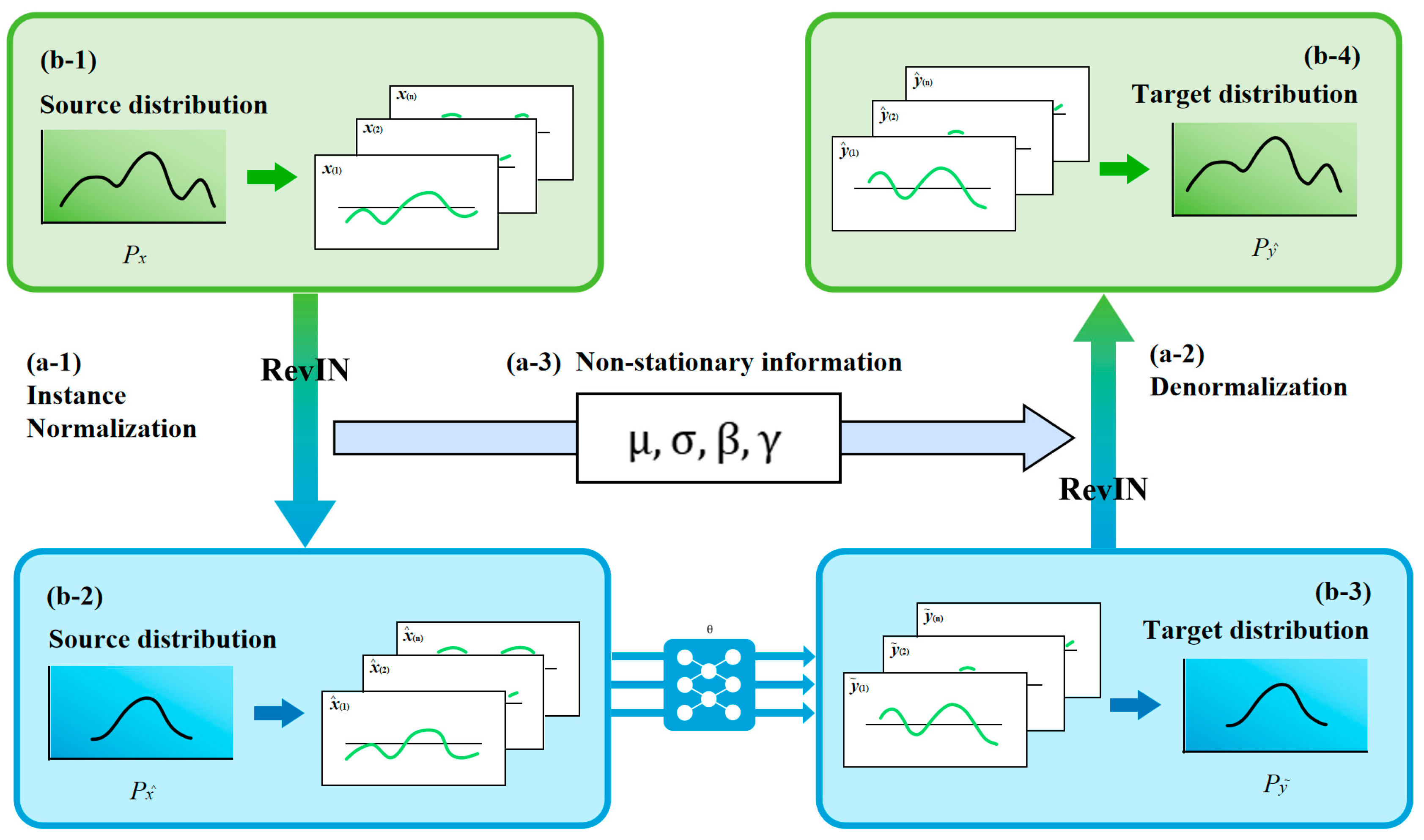

3.3.1. RevInformer

- Elimination of input-output distribution discrepancies;

- Effective resolution of distribution shift in forecasting;

- Preservation and reversible recovery of non-stationary information;

- Mitigation of information loss through parameter retention.

3.3.2. RevInformer-Based Sales Forecasting

4. Numerical Verification and Discussion

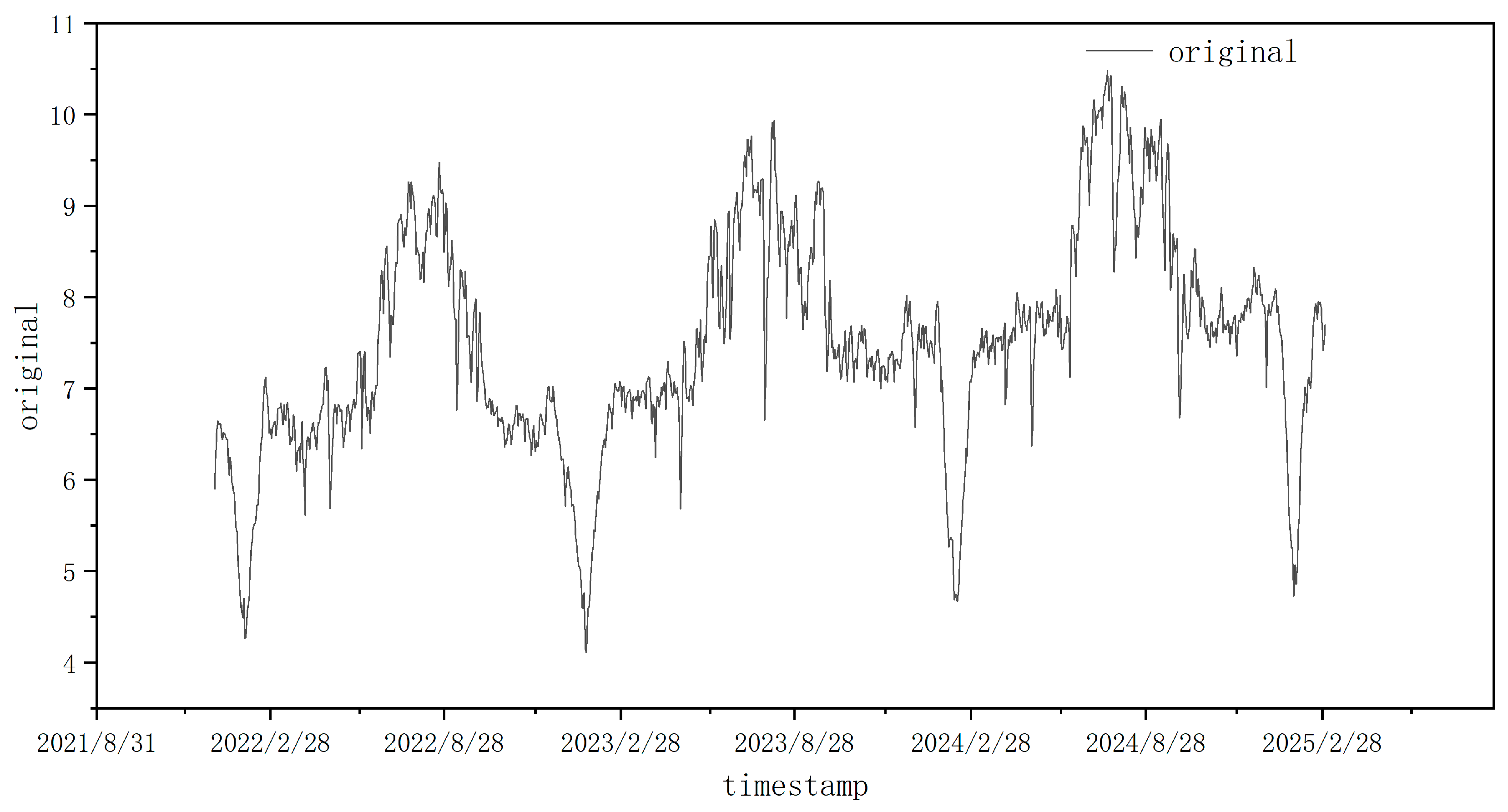

4.1. Dataset Introduction

- (1)

- Temporal Features: Day of the week, month, a binary indicator for holidays/weekends, and a sequential day index.

- (2)

- Meteorological Features: Daily maximum, minimum, and average temperature obtained from a local weather station.

- (3)

- Historical Load Features: Lagged values and rolling statistics.

4.2. Simulation Setup

4.2.1. Performance Indicators

- (1)

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

- (2)

- Mean Squared Error (MSE)

- (3)

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

- (4)

- Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)

- (5)

- Mean Squared Percentage Error (MSPE)

4.2.2. Parameter Settings

4.2.3. Software and Hardware Platform

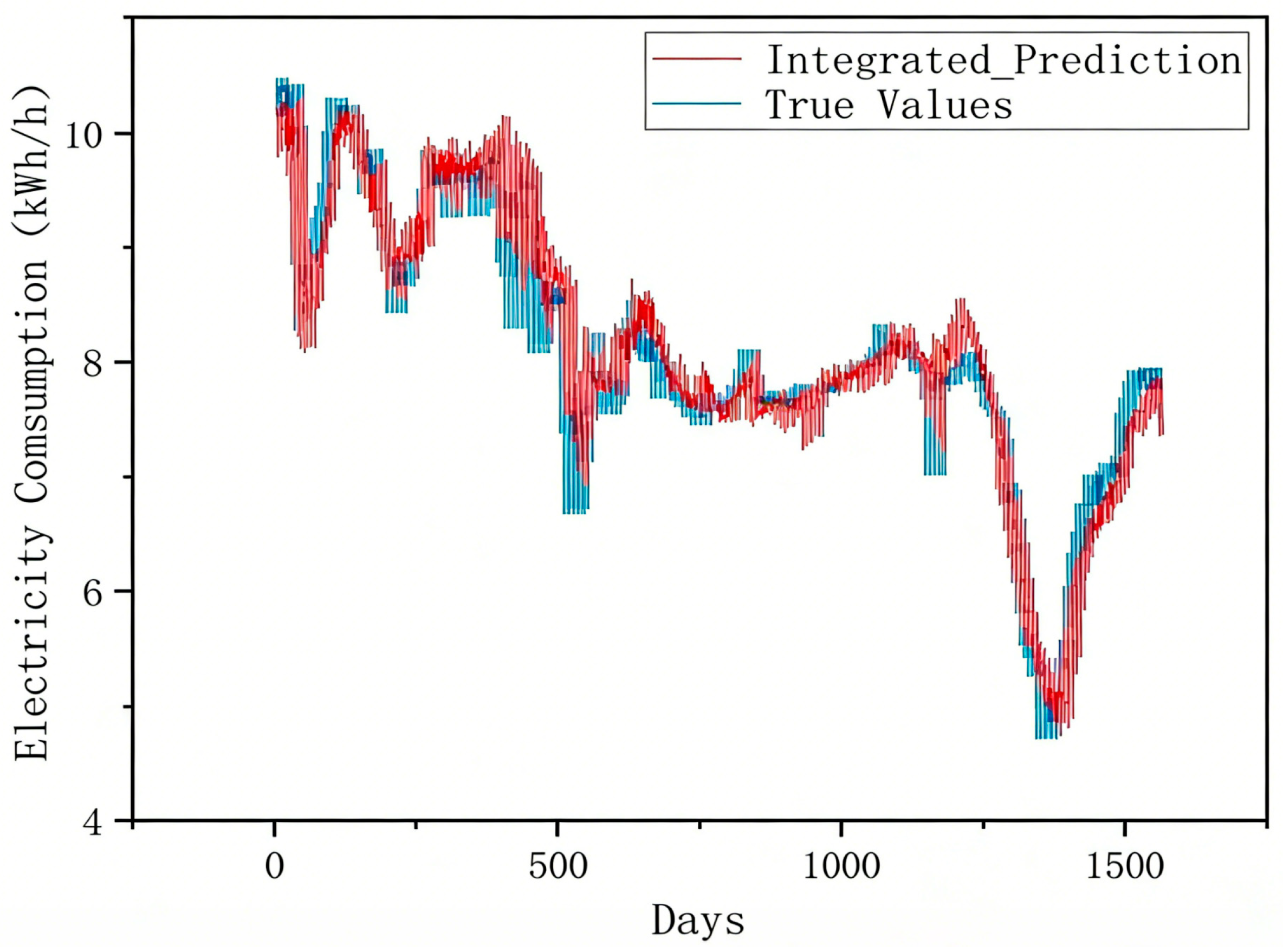

4.3. Comparations with Other Methods

4.4. Robustness and Stability Analysis

- (1)

- Stability and Repeatability (Multiple Runs): To evaluate the stability of our results, each model (LSTM, Informer, RevInformer, VMD-RevInformer) was independently run 10 times with different random seeds. The mean and standard deviation of the key performance metrics across these runs are reported in Table 5. The low standard deviations observed for the VMD-RevInformer model confirm that its superior performance is consistent and not an artifact of a single favorable initialization.

- (2)

- Sensitivity Analysis: We investigated the sensitivity of the VMD-RevInformer framework to its two most critical hyperparameters:

- (a)

- VMD Mode Number (K): We varied K by ±1 and ±2 around the optimized value (K = 8). The resulting changes in RMSE were less than 3.5% and 6.1%, respectively.

- (b)

- RevInformer Learning Rate: We perturbed the optimal learning rate by ±50%. The corresponding fluctuation in RMSE was within 2.8%.

- (3)

- Computational Cost (Implicit Stability Metric): While primarily an efficiency measure, consistent computational cost across runs also implies stable behavior. As shown in Table 5, the average training and inference times for our model show low variance (±5%) across the 10 runs, further attesting to its operational stability.

4.5. Contribution of Each Module

- (1)

- Baseline: Original Informer model;

- (2)

- VMD-Informer: Baseline enhanced with Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) for data preprocessing;

- (3)

- VMD-RevInformer: VMD-Informer with its core module replaced by the proposed RevInformer.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

- (1)

- An innovative adaptive decomposition–integration forecasting framework is proposed. By integrating the ZOA with VMD, we achieved adaptive decomposition of the original series, effectively mitigating the difficulties posed by data non-stationarity and strong coupling for modeling, thereby laying a foundation for subsequent accurate predictions.

- (2)

- An improved RevInformer model is developed. The introduction of the RevIN layer significantly enhances the model’s adaptability to distribution shifts in temporal data. Concurrently, its ProbSparse self-attention mechanism and generative decoder design ensure long-range dependency modeling while markedly improving the efficiency of long-sequence forecasting.

- (3)

- The framework’s effectiveness and superiority are demonstrated through comprehensive simulations. Empirical studies on a commercial building electricity dataset show that our proposed VMD-RevInformer model significantly outperforms benchmark models such as LSTM and Informer across key metrics including MAE, RMSE, and MSPE, with performance improvements ranging from 60% to 90%. This robustly validates the advancement and practicality of the proposed solution.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, S.; Miao, Y.; Chung, C.Y.; Chen, Z. Probabilistic Residential Load Forecasting with Sequence-to-Sequence Adversarial Domain Adaptation Networks. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 12, 1559–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Deo, R.C.; Casillas-Pérez, D.; Salcedo-Sanz, S. Two-step deep learning framework with error compensation technique for short-term, half-hourly electricity price forecasting. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Qian, T.; Li, W.; Tang, W.; Xu, Z. An individualized adaptive distributed approach for fast energy-carbon coordination in transactive multi-community integrated energy systems considering power transformer loading capacity. Appl. Energy 2024, 375, 124189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, X.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.; He, Y.; Long, C.; Geng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, J.; Liu, T. More flexibility and waste heat recovery of a combined heat and power system for renewable consumption and higher efficiency. Energy 2025, 315, 134392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Rong, F.; Lin, C. A multi-energy loads forecasting model based on dual attention mechanism and multi-scale hierarchical residual network with gated recurrent unit. Energy 2025, 320, 134975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Lu, Y. Power System Load Forecasting and Energy Management Model Based on Data-Driven. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Electrical Drives, Power Electronics & Engineering (EDPEE), Athens, Greece, 26–28 March 2025; pp. 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbandi, A.; Brockmann, G.; Kriegel, M. Improving heat demand forecasting with feature reduction in an Encoder–Decoder LSTM model. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 5048–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Xing, H. Predicting the highest and lowest stock price indices: A combined BiLSTM-SAM-TCN deep learning model based on re-decomposition. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 167, 112393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G. Box and Jenkins: Time Series Analysis, Forecasting and Control. In A Very British Affair; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 161–215. ISBN 978-1-349-35027-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Zhai, D.; Xu, W.; Gong, W.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, L. Accurate and efficient daily carbon emission forecasting based on improved ARIMA. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Zhu, F.; Xiong, G.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F.; Liu, T. Short-term traffic flow forecasting based on wavelet transform and neural network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Yokohama, Japan, 16–19 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lichev, L.; Mitsche, D.; Pérez-Giménez, X. Random spanning trees and forests: A geometric focus. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2026, 59, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.K. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 August 1995; Volume 1, pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, M.I.; Conway, E.; Farrelly, K.; Grodin, J.; Keller, B.; Mozer, M.; Navon, D.; Parkinson, S. Serial Order: A Parallel Distrmuted Processing Approach. 2009. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/SERIAL-ORDER%3A-A-PARALLEL-DISTRmUTED-PROCESSING-Jordan-Conway/f8d77bb8da085ec419866e0f87e4efc2577b6141?p2df (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Elman, J.L. Finding structure in time. Cogn. Sci. 1990, 14, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.-T.; Hoang, D.-H.; Phan, T.; Tran, M.-T.; Patel, B.; Adjeroh, D.; Le, N. TSRNet: Simple Framework for Real-time ECG Anomaly Detection with Multimodal Time and Spectrogram Restoration Network. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.10187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to forget: Continual prediction with LSTM. In Proceedings of the 1999 Ninth International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks ICANN 99. (Conference Publish No. 470), Edinburgh, UK, 7–10 September 1999; Volume 2, pp. 850–855. [Google Scholar]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, D.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Tao, Z. DTSFormer: Decoupled temporal-spatial diffusion transformer for enhanced long-term time series forecasting. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 309, 112828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, Z.; Wen, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. FEDformer: Frequency Enhanced Decomposed Transformer for Long-term Series Forecasting. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mchara, W.; Manai, L.; Khalfa, M.A.; Raissi, M.; Dimassi, W.; Hannachi, S. A hybrid deep learning framework for global irradiance prediction using fuzzy C-Means, CNN-WNN, and Informer models. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 28, 101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Dai, Y.; Ren, T.; Leng, M. Short-time photovoltaic power forecasting based on Informer model integrating Attention Mechanism. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 178, 113345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-C.; Sun, L.-P.; Wu, X.; Tao, C. Enhancing financial time series forecasting with hybrid Deep Learning: CEEMDAN-Informer-LSTM model. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 177, 113241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yan, R.; Zhang, J.; Fan, J.; Yan, G.; Li, P. Harnessing dynamic carbon intensity for energy-data co-optimization in internet data centers. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armah, M.; Bossman, A.; Amewu, G. Information flow between global financial market stress and African equity markets: An EEMD-based transfer entropy analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xu, B.; Liu, H.; Hou, J.; Zhang, J. Wind Power Prediction Based on Variational Mode Decomposition and Feature Selection. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2021, 9, 1520–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiuzzaman, M.; Safayet Islam, M.; Rubaith Bashar, T.M.; Munem, M.; Nahiduzzaman, M.; Ahsan, M.; Haider, J. Enhanced very short-term load forecasting with multi-lag feature engineering and prophet-XGBoost-CatBoost architecture. Energy 2025, 335, 137981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Ju, Z.; Xie, B.; Chen, J.; Ma, Q.; Li, M. Signal processing for miniature mass spectrometer based on LSTM-EEMD feature digging. Talanta 2025, 281, 126904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Kim, J.; Tae, Y.; Park, C.; Choi, J.-H.; Choo, J. Reversible Instance Normalization for Accurate Time-Series Forecasting Against Distribution Shift. Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=cGDAkQo1C0p (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- AlSmadi, L.; Lei, G.; Li, L. Enhanced Electricity Demand Forecasting in Australia Using a CNN-LSTM Model with Heating and Cooling Degree Days Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Future Energy Electronics Conference (IFEEC), Sydney, Australia, 20–23 November 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.; Tian, X.; Wang, K.; Yang, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, J. Enhanced load forecasting for distributed multi-energy system: A stacking ensemble learning method with deep reinforcement learning and model fusion. Energy 2025, 319, 135031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Xiang, L.; Zhu, S.; Lin, Q. Scenario probabilistic data-driven two-stage robust optimal operation strategy for regional integrated energy systems considering ladder-type carbon trading. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Minimum | Maximum | Optimum | Population | Maximum Number of Iterations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | 5 | 15 | 8 | 15 | 100 |

| α | 500 | 5000 | 511 |

| Name | Numerical Value | Explain |

|---|---|---|

| Model | Informer | Use the Informer model |

| enc_in | 31 | Encoder input feature dimension (dynamic setting according to the dynamic number of data features) |

| dec_in | 31 | Decoder input characteristic dimension (consistent with the encoder) |

| c_out | 8 | Output dimension (predict the number of target columns, dynamically set by the data parser data_parser) |

| c_out | 8 | Output dimension (predict the number of target columns, dynamically set by the data parser data_parser) |

| d_model | 512 | Model hidden layer dimension |

| n_heads | 8 | The number of heads of the multi-head attention mechanism |

| e_layers | 2 | Number of encoder layers |

| d_layers | 1 | Number of decoder layers |

| d_ff | 2048 | Feedforward grid dimension |

| attn | Prob | Attention type (ProbSparse) |

| factor | 5 | Sparse attention factor |

| distil | TRUE | The encoder uses the distillation mechanism |

| mix | TRUE | The decoder uses mixed attention |

| Name | Scope | Explain |

|---|---|---|

| data | custom | Custom data set |

| root_path | \ | Data root directory path |

| data_path | \ | Data file name |

| features | S/M/MS | Prediction mode |

| target | \ | Target column name |

| seq_len | 30 | Input sequence length |

| label_len | 15 | Decoder starting mark length |

| pred_len | 7 | Predict the length of the sequence |

| freq | d | Time characteristic coding frequency |

| train_epochs | 150/200 | Total rounds of training |

| batch_size | 6 | Batch size |

| learning_rate | 0.0001 | Initial learning frequency of Adam optimizer |

| loss | mse | Loss function |

| dropout | 0.05 | Random discardment rate |

| MSE | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | MSPE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.506737 | 0.469673 | 0.685327 | 6.416559 | 0.813309 |

| Informer | 0.457568 | 0.456091 | 0.622173 | 5.985666 | 0.721323 |

| RevInformer | 0.387774 | 0.375074 | 0.612433 | 5.594999 | 0.625999 |

| VMD-RevInformer | 0.155937 | 0.044783 | 0.211621 | 1.986559 | 0.074951 |

| MAE | RMSE | MSPE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informer | 0.456 ± 0.012 | 0.623 ± 0.016 | 0.722 ± 0.019 |

| RevInformer | 0.375 ± 0.009 | 0.612 ± 0.011 | 0.626 ± 0.015 |

| VMD-RevInformer | 0.045 ± 0.002 | 0.212 ± 0.004 | 0.075 ± 0.002 |

| MSE | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | MSPE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informer | 0.506737 | 0.469673 | 0.685327 | 6.416559 | 0.813309 |

| VMD-Informer | 0.155937 | 0.165839 | 0.220879 | 2.066998 | 0.075588 |

| VMD-RevInformer | 0.048788 | 0.044783 | 0.211621 | 1.986559 | 0.074951 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, X.; Wang, D.; Shen, M.; Deng, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q.; Hou, L.; Wang, Q. A Novel Decomposition–Integration-Based Transformer Model for Multi-Scale Electricity Demand Prediction. Electronics 2025, 14, 4936. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244936

Yu X, Wang D, Shen M, Deng Y, Liu H, Liu Q, Hou L, Wang Q. A Novel Decomposition–Integration-Based Transformer Model for Multi-Scale Electricity Demand Prediction. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4936. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244936

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Xiang, Dong Wang, Manlin Shen, Yong Deng, Haoyue Liu, Qing Liu, Luyang Hou, and Qiangbing Wang. 2025. "A Novel Decomposition–Integration-Based Transformer Model for Multi-Scale Electricity Demand Prediction" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4936. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244936

APA StyleYu, X., Wang, D., Shen, M., Deng, Y., Liu, H., Liu, Q., Hou, L., & Wang, Q. (2025). A Novel Decomposition–Integration-Based Transformer Model for Multi-Scale Electricity Demand Prediction. Electronics, 14(24), 4936. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244936