Abstract

Smart contracts rely on blockchain oracles to access off-chain data, yet existing oracle designs often face challenges such as untrustworthy data sources, weak temporal guarantees, and limited verifiability. This work presents Ivy Oracle, a robust and time-trustworthy data feed framework that enhances the reliability and auditability of off-chain information for smart contracts. Ivy Oracle integrates trusted execution environments (TEEs) for secure data acquisition, an external time server for authenticated timestamps, and a PageRank-based trust model to evaluate source credibility. We implement and evaluate Ivy Oracle on the Ethereum Sepolia testnet, demonstrating that it achieves up to 63.6% lower on-chain gas consumption than Chainlink for signature verification while maintaining only a slight increase in communication overhead due to its dual-attestation mechanism. These results confirm that Ivy Oracle provides strong time trustworthiness and data reliability with minimal performance cost, making it suitable for latency-sensitive blockchain applications.

1. Introduction

The rise of blockchain technology and decentralized applications (DApps) has spurred innovation across diverse domains, including decentralized finance (DeFi), supply chain traceability, and automated insurance [1,2,3,4]. At the core of these applications lies the smart contract, a self-executing piece of code that enforces business logic in a transparent and verifiable manner, without relying on trusted intermediaries [5,6,7,8]. However, despite their autonomy, smart contracts are inherently limited in accessing data beyond the blockchain. This isolation presents a fundamental barrier to real-world applicability, as smart contracts cannot natively perceive off-chain events such as asset prices, sensor readings, or weather conditions [9,10,11].

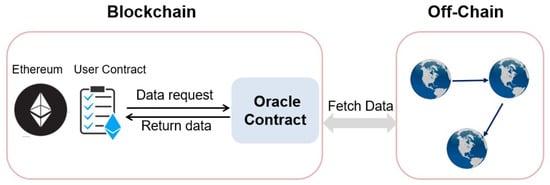

To overcome this limitation, blockchain oracles have emerged as trusted intermediaries that retrieve, verify, and inject external data into the on-chain environment [12,13,14]. As shown in Figure 1, oracles act as a bridge between smart contracts and external data sources: they fetch data from off-chain sources and return the verified results on-chain, enabling smart contracts to execute in response to real-world events. Without robust and trustworthy oracles, the practical utility of smart contracts remains severely constrained.

Figure 1.

Oracles act as a bridge between blockchain-based smart contracts and external data sources.

Despite the growing attention to blockchain oracle design, existing solutions still suffer from critical limitations and strong assumptions. One fundamental issue is the lack of a time-trustworthy source in Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs). For example, Town Crier [12] assume that Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) such as Intel SGX can provide accurate and tamper-proof timestamps [12], while Ekiden [15] points out that TEEs can only provide a “no-earlier-than” notion of time. In practice, this limitation enables host-level delay attacks, where a malicious host can postpone oracle queries and feed outdated or manipulated data into smart contracts, undermining their reliability and timeliness.

Another challenge lies in the assumption of data source robustness. Many existing oracle designs, such as Chainlink [16], assume that authoritative or popular data sources tend to produce accurate results or can be aggregated via majority voting. However, this assumption often fails in adversarial environments, where subtle correlations among data sources can synchronously bias results and mislead the oracle [13]. Furthermore, even reliable data sources may unintentionally link to low-quality or outdated content, introducing noise and latency into the aggregation process [17].

These limitations are not only theoretical but have been repeatedly observed in practice. For example, DeFi platforms such as Aave and Compound have suffered liquidation failures when delayed or inaccurate oracle price feeds prevented timely collateral settlement during volatile markets. Similarly, attackers have exploited oracle latency in flash-loan attacks, manipulating asset prices within a single block to extract arbitrage profits and cause multi-million-dollar losses [18,19]. These real-world incidents underscore the urgent need for a robust and time-trustworthy oracle framework, which directly motivates the design of Ivy Oracle.

1.1. Technical Challenges

To design a robust and time trustworthy oracle, several technical challenges must be addressed:

- Enduring Failure of TEE Time Source. TEEs such as Intel SGX and Arm TrustZone lack native support for trusted, high-resolution timekeeping. Existing approaches either rely on enclave timers (which are manipulable by the host) or assume external synchrony. This opens the door to time-delay attacks [20], where the host can freeze or replay stale data. However, in many time-sensitive applications (e.g., DeFi liquidations), ensuring that the datagram reflects the correct timestamp is critical to maintaining on-chain consistency and fairness.

- Malicious TEE Host. Although TEEs offer strong guarantees of execution integrity and confidentiality, they rely on a host machine for power, I/O, and scheduling. A malicious or compromised host may abort the TEE, tamper with data flow, or selectively censor outputs. Given that TEEs are often deployed in untrusted infrastructure (e.g., public cloud), ensuring liveness and delivery of oracle responses despite a hostile host remains an open problem.

- Unreliable Data Sources. To achieve robust blockchain oracle, the primary issue is to obtain reliable data from data sources. However, there is no, of course, fully trustworthy data sources in real-world. Thus, lots of schemes acquire data from multiple data sources and aggregate data as a final answer, e.g., the majority voting. That is, if majority of data sources return an identical answer, then the oracle returns this answer. Unfortunately, there exist many correlated data sources that inaccurate data from will definitely have influence on .

- Atomic Delivery of Datagrams. In traditional smart contract workflows, the user pays a transaction fee to invoke the oracle but may not receive any useful response if the oracle fails to deliver. This leads to both economic loss and poor user experience. Therefore, ensuring atomic delivery, meaning that the data and the fee are either both successfully exchanged or both withheld, is a key requirement for practical oracle adoption.

1.2. Contributions

To overcome the above challenges, we propose Ivy Oracle, a robust and time trustworthy oracle framework that systematically addresses the limitations of existing designs. The contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Identification and formalization of key challenges. We rigorously analyze the weaknesses of prior oracle systems and highlight two fundamental obstacles: the lack of a time trustworthy source in TEEs, which enables delay or replay attacks, and the prevalence of unreliable or correlated data sources, which undermines aggregation-based trust models.

- Hybrid architecture with verifiable time and trust evaluation. We design Ivy Oracle as a modular architecture that integrates TEE-based secure execution, an external time server for authenticated timestamp attestation, and a PageRank-inspired trust model for evaluating and weighting data sources. This hybrid design ensures both robustness and time trustworthiness, going beyond majority-voting assumptions.

- Configurable and auditable data feed. Ivy Oracle supports multi-round data collection and user-defined aggregation strategies (e.g., majority vote, averaging, or custom functions), allowing flexibility for diverse smart contract applications. All trust scores and timestamp attestations are committed on-chain, enabling auditability and dispute resolution in case of misbehavior.

- Atomic and incentive-compatible delivery. We incorporate an atomic delivery mechanism tied to deposits and signatures, ensuring that users either obtain both the data and pay the fee, or neither. This reduces economic risk and improves usability for latency-sensitive decentralized finance (DeFi) and supply-chain scenarios.

- Prototype implementation and evaluation. We implement Ivy Oracle on the Ethereum Sepolia testnet, demonstrating end-to-end feasibility. Our evaluation shows that Ivy Oracle achieves strong guarantees of robustness, time trustworthiness, and trust configurability with minimal off-chain and on-chain overhead, confirming its practicality for real-world deployment.

1.3. Paper Organization

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related works. Section 3 summarizes preliminaries. Section 4 presents the system overview, security model, workflow, and desired properties of Ivy Oracle. Section 5 details the Ivy Oracle protocol. The security analysis and performance analysis are respectively provided in Section 6 and Section 7. Section 8 concludes and discusses future directions.

2. Related Works

Reliable data feed systems play a crucial role in enabling smart contracts to consume off-chain information. As the accuracy and timeliness of data directly affect the correctness of on-chain execution, numerous oracle frameworks have been proposed to bridge the gap between blockchain platforms and external data sources.

Town Crier [12] is one of the earliest authenticated oracle systems, leveraging Intel SGX to retrieve data from HTTPS-enabled sources and return signed results to smart contracts. While it ensures integrity through enclave execution, it relies on the host system’s clock and lacks protection against delayed data injection attacks, which is a critical issue in latency-sensitive applications such as financial derivatives and insurance contracts. Ekiden [15] follows a similar TEE-based approach but explicitly identifies the absence of trusted time sources in SGX as a major limitation. Their analysis demonstrates that timestamp ambiguity may arise even under hardware attestation, thereby undermining freshness guarantees.

To improve resilience and decentralization, Chainlink [16] proposed a widely adopted multi-source data feed network that aggregates responses using majority voting. While this improves fault tolerance, it assumes source independence and consistent quality, assumptions which have been challenged by later studies. Al-Breiki et al. [13] show that mirrored or correlated APIs can introduce synchronized biases, resulting in inaccurate consensus even in the absence of malicious behavior. Additionally, the quality of retrieved data is often not structurally validated. Ordoñez et al. [17] address this by performing multi-label data validation, but their approach does not incorporate graph-based linkage analysis or support adaptive source selection.

To further enhance data authenticity and accountability, Guarnizo and Szalachowski [21] proposed PDFS, which leverages cryptographic attestations and TLS transparency logs to build an authenticated data delivery channel between web sources and smart contracts. While PDFS ensures that data has not been tampered with in transit, it does not evaluate the trustworthiness or freshness of the data source itself, leaving the system vulnerable to stale but valid data.

Meanwhile, Park et al. [22] designed a privacy-preserving oracle framework that enables selective disclosure of sensitive off-chain data to smart contracts through encrypted transmission and access control. Their system addresses confidentiality but does not incorporate dynamic source evaluation or verifiable timestamps, limiting its robustness in adversarial environments.

Feng et al. [23] propose a novel off-chain data feed mechanism leveraging a blockchain oracle network based on a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)-based distributed ledger. Their approach improves scalability and network throughput by avoiding traditional consensus bottlenecks. However, their work does not focus on structural evaluation of data sources or temporal trust anchoring, which are critical for applications requiring verifiable data timeliness and quality.

Unlike prior work, Ivy Oracle incorporates a PageRank-based trust scoring mechanism that evaluates the structural importance of web-based data sources. By constructing a hyperlink graph and computing inlink/outlink scores, Ivy Oracle identifies data sources that are authoritative, non-redundant, and structurally central in the information ecosystem. This trust score is publicly committed on-chain, enabling transparency and dispute resolution. Ivy Oracle further supports periodic timestamp validation via external time servers, enhancing resistance to backdating and delay attacks. Finally, it allows user-defined aggregation strategies, such as maximum, average, or majority, to provide application-specific flexibility.

To clearly position Ivy Oracle among existing designs, Table 1 compares representative blockchain oracle systems across four core design dimensions: authenticity, TEE-based execution, trusted timestamping, and data-source trust evaluation. As shown in the Table 1, most prior schemes provide only partial guarantees, typically authenticity or secure execution, while lacking verifiable temporal integrity or adaptive trust management. In contrast, Ivy Oracle integrates all four properties into a unified framework, combining PageRank-based trust scoring, time server-assisted freshness verification, and modular aggregation. This comprehensive design makes Ivy Oracle more robust and suitable for real-world decentralized applications that require jointly verifiable data provenance, timestamp assurance, and trustworthy source evaluation.

Table 1.

Feature comparison of representative blockchain oracle systems.

3. Preliminary Review

3.1. Smart Contract and Transaction

Particularly, the review of main features on blockchain can be listed as follows: (1) Complete Decentralization: it is based on distributed P2P network that many untrusted nodes can achieve fair data exchange without reliance on a central party. (2) Correct Execution: blockchain is a global computer that each blockchain node can trace and verify the correctness of the data computation. (3) Tamper-resistance: the data (i.e., blocks and transactions) are tamper-resistant since they are organized in a special data structure (Merkle tree and hash chain).

And also, smart contracts are designed to construct the decentralized application (DApp) [5] that facilitates the process of an application to be executed automatically and verifiably. People could participate in one DApp by providing valid inputs through on-chain transactions to call a function in smart contract.

3.2. Blockchain Oracle

A blockchain oracle is a trusted bridge between blockchain-based smart contracts and external data sources, enabling access to off-chain information that is not inherently available within the blockchain environment [18]. Since smart contracts are deterministic and do not have native access to external systems, oracles serve as intermediaries that retrieve, verify, and transmit real-world data to on-chain applications for conditional execution [24].

Oracles can be classified along multiple dimensions, such as directionality (inbound or outbound), trust model (centralized or decentralized), and data origin (software, hardware, or human). Inbound oracles deliver off-chain data to smart contracts (e.g., asset prices, weather, sensor data), while outbound oracles relay blockchain events to external systems (e.g., payment triggers or API calls) [25].

To enhance reliability and trust, modern oracles employ various mechanisms including decentralized consensus (e.g., Chainlink [16]), secure hardware such as trusted execution environments (TEEs), or authenticated data feeds. These techniques help mitigate risks such as data manipulation, single-point-of-failure, or timestamp forgery [12].

3.3. Time Server

A time server is a networked service that provides accurate and synchronized time information to client devices. It typically obtains the current time from a high-precision reference source, such as a GPS receiver, atomic clock, or radio time signal, and distributes this information over a network using standardized protocols. The most widely adopted protocol for time synchronization is the Network Time Protocol (NTP), which is designed to deliver millisecond-level accuracy even in the presence of variable network delays. Since its introduction, NTP has become the widely adopted standard for time coordination in distributed systems [26].

In security-sensitive applications, such as blockchain oracles, financial systems, and digital forensics, verifiable and tamper-resistant time is crucial. For such use cases, a trusted time server can act as a third-party authority to timestamp events, provide auditability, and prevent replay or backdating attacks.

3.4. Trust Execution Environment

A key building block of Ivy Oracle is a trusted execution environment (TEE) that protects the confidentiality and integrity of computations, and can issue proofs, known as attestations, of computation correctness. Ivy Oracle is implemented with Intel SGX [27,28], a specific TEE technology, but we emphasize that it may use any comparable TEE with attestation capabilities, such as the ongoing effort Keystone-enclave [29] aiming to realize open-source secure hardware enclave. We now offer brief background on TEEs, with a focus on Intel SGX.

Intel SGX is a set of security-related instruction codes that are built into modern Intel CPUs. It enables the creation of secure enclaves, which are protected areas of execution in memory and are isolated from the rest of the system. These enclaves ensure confidentiality and integrity even in the presence of a compromised operating system or hypervisor, making them ideal for sensitive applications. Furthermore, SGX supports remote attestation, allowing a third party to verify that the correct application code is running inside the enclave. These properties make SGX a practical and widely adopted TEE platform for secure data feeds in blockchain-based applications like Town Crier [12].

3.5. PageRank

PageRank is an algorithm originally developed by Google to rank web pages in their search engine results [30,31]. It estimates the importance of each node in a directed graph based on the structure of incoming edges, following the intuition that a node is important if it is referenced by other important nodes.

Formally, PageRank computes the stationary distribution of a random walk over the graph, where the probability of visiting each node reflects its relative significance. The basic idea is that each node distributes its rank value equally among all the nodes it links to. To handle dangling nodes and ensure convergence, the algorithm introduces a damping factor, typically set to 0.85, that allows random jumps to any node in the graph.

Beyond web search, PageRank has also been applied in software engineering to assess the importance of program elements [32,33,34]. For example, a method that is frequently invoked by other central methods is regarded as more important than one with fewer or less influential callers.

4. Overview of Ivy Oracle

4.1. System Model

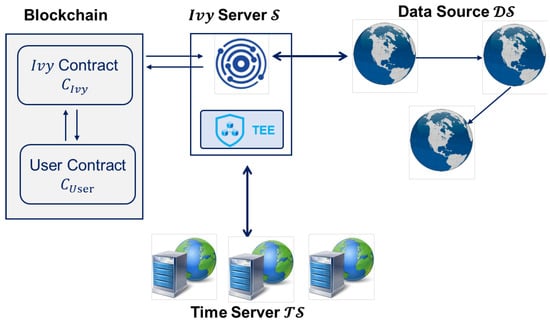

The architecture of the Ivy Oracle revealing its interaction with different types of entities is illustrated in Figure 2. It contains four main components: the Ivy contract (), the Ivy server (), the time server (), and a set of external data sources ().

Figure 2.

The system model of Ivy Oracle.

- Ivy contract (): Deployed on the blockchain, it interacts directly with user contracts. It acts as the on-chain interface that receives data requests from users and dispatches them to the Ivy server based on the “Event” mechanism.

- Ivy Server (): It acts as a relay to acquire data from external data sources after receiving a request. Specifically, it embeds with TEE (e.g., SGX) that acquires data based on the HTTPS-enabled internet services, and is designed with a wallet that returns message to the user contract in a signed transaction.

- Time Server (): This trusted off-chain entity provides authenticated timestamps. It issues signatures on time-sensitive data operations initiated by the Ivy server or the data source using its private key . The corresponding public key is published on-chain so that the Ivy contract can verify the validity of time attestations before accepting results.

The Ivy server is a critical off-chain component that bridges smart contracts with the external world. To support diverse user requirements, it integrates multiple functional modules that analyze query parameters, coordinate with data sources, and perform data aggregation before forwarding the final result to the Ivy contract . In addition, has a key pair, i.e., . The public key is public on the blockchain while the private key is only known to . Besides, there exist many data sources (identified by ) which refer to the HTTP-enabled websites in our system model. As mentioned before, considering the nonsynchronous correlated data between different data sources, we assume that data sources are untrustworthy.

4.2. Security Model

We present the security model for the Ivy Oracle. The assumptions are listed as follows.

The Ivy contract. is a smart contract deployed on the blockchain. Its source code is publicly accessible and is executed automatically upon receiving valid inputs. Following the majority-honest assumption [35,36], we assume that behaves faithfully as specified in its code.

The Ivy server. In terms of the security of Ivy server, we adopts the standard TEE assumption, namely that enclave execution provides confidentiality and integrity guarantees. Although side-channel attacks (e.g., transient execution or cache-based leakage) have been reported against TEEs, recent research has proposed effective countermeasures such as constant-time programming, oblivious memory access, and speculative execution barriers [20,27]. These mitigation techniques are complementary to Ivy Oracle and can be incorporated into its TEE component if required. As our focus is on the technical challenges described in Section 1.1, especially on enhancing temporal integrity and data source robustness, we rely on the widely adopted TEE security assumption.

Moreover, we assume that the Ivy server is an ordinary server that might be compromised by malicious users or be vulnerable to denial-of-service attack. That is, the host of the Ivy server might be crashed or be power off. Thus, the Ivy server should be recognized as stateless that the state of data might be lost at any point. Based on the two assumptions, we consider the Ivy server behaves dishonestly. In addition, a malicious or compromised host might manipulate the task executed in Enclave arbitrarily, e.g., delaying the Enclave request. Thus, we consider TEE as a non-trusted timer that it cannot provide the accurate time.

Time server. Although the Ivy server has a trusted relative timer, while the Ivy server is untrustworthy, thus our proposed Oracle should minimize reliance on the Ivy server timer. We assume the time server is an honest Internet standard time server. It provides an accurate timestamp for the Ivy Oracle. A time server has a key pair (i.e., public key and private key ) that the public key is known to others and the private key keeps secret. For each request, the time server will sign on the request and others could verify it publicly.

Data source. The ideal blockchain oracle is hard to achieve due to the untrustworthy data sources. Parts of the data sources obtain data from other data sources, while they do not synchronize data with the original data sources timely, or the data may be tampered by malicious internal attacks, leading to inaccurate data providing. Furthermore, instead of assuming that datagrams are consistent during a requester’s time interval as in [12], Ivy Oracle supposes that datagrams can be variable even within a specific small time interval.

Network communication. The integrity of data can be ensured and the quality of network keeps well that any data request or providing can be achieved efficiently.

4.3. Workflow

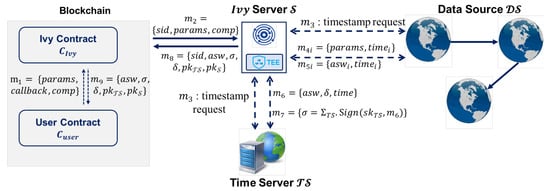

As illustrated in Figure 3, the diagram presents the data flow of the Ivy Oracle at a high level, which facilitates secure off-chain data acquisition for on-chain contracts. To initiate a request, the user contract calls the Ivy contract and sends a message . Here, encodes the query configuration. The field identifies the targeted data sources, while specifies the content to be queried, e.g., a weather report at a specific time. T specifies the delivery time of the answer. and specifies the range of the request time, and n is the number of the request during this time, i.e., the Ivy Oracle is required to acquire data from for n times between and . The parameter designates the entry function in where the final datagram will be returned. The field specifies an aggregation function to be applied to the multiple responses collected from different rounds, such as majority voting, averaging, or user-defined logic. The Ivy contract generates a unique session identifier for this request and sends to the Ivy server for further processing.

Figure 3.

The data flow of Ivy Oracle.

Before forwarding the requests, the Ivy server analyzes the requested data source on whether it is reliable and original by utilizing the PageRank algorithm. Specifically, to ensure the correctness of the analysis, the output of the PageRank algorithm, denoted as , must be committed to the blockchain, i.e., , where refers to the data sources’ relationship graph based on the Link Checker. If there exists a dispute, e.g., a user contract claims the data feed is inaccurate and intends to redeem deposits, then the details of the output are required to be published on the chain.

To ensure temporal reliability without compromising efficiency, the Ivy server periodically performs timestamp consistency checks. At fixed intervals (e.g., every 12 h), it simultaneously queries the candidate data source and the trusted time server for their current timestamps. If the reported times are sufficiently close, is considered temporally reliable for subsequent data requests.

Subsequently, the Ivy server sends n individual requests to the selected data source at a specific time within the interval , where . Each request includes the query details and the target timestamp for the i-th round. In response, the data source returns a response message to , where denotes the result of the query at time . After collecting the valid responses from the selected data source , applies the user-specified aggregation function to compute the final datagram .

To establish a trusted temporal reference for the final output, the Ivy server sends to the time server , where is a digital signature. Subsequently returns a signature .

Finally, returns to the Ivy contract . first verifies the signature using to ensure the result is anchored to a valid timestamp. If successful, it then verifies the signature using to confirm the authenticity of the aggregated result. If both checks pass, invokes the function in and passes to complete the delivery. Upon receiving , the user contract performs the same signature verifications. If either signature is invalid, the result is rejected.

4.4. Desired Properties

We list the desired properties of our proposed solution.

- Robustness. The Ivy Oracle could obtain robust values from reliable data sources, that is, users can still obtain trustworthy data in spite of limited knowledge on selecting reliable data sources.

- Time-insensitivity. Data is called time-sensitive data when it changes dramatically within a small time interval. As for this type of data, the Ivy Oracle can provide reliable data based on users’ setting, which enables it to be time-insensitive data.

- Flexibility. As for the time-sensitive data, the Ivy Oracle allows user to select the model of data feed flexibly, e.g., setting data from Oracle as maximum value or average value.

5. The Ivy Oracle Protocol

We present the concrete protocol of the Ivy Oracle. It is worth noting that our proposed Oracle could be deployed as multiple instances (i.e., multiple Ivy servers and time servers), which means that different Ivy Oracles provide more trustworthy and reliable answers based on the reputation mechanism and majority voting. For simplicity, we consider a single Ivy server and a time server here. Basically, the main process of the Ivy Oracle protocol can be specified as five phases: initialization, contract deployment, request analysis, data retrieval, and data delivery.

5.1. Initialization

The initialization phase is to set up the whole Ivy Oracle system. Without generalization, we assume that the Ivy server has been allocated a blockchain wallet which corresponds with a key pair . Let represent the current balance of ’s wallet. To ensure sufficient gas for executing smart contract operations, must deposit a certain amount of cryptocurrency into in advance. In addition, timestamp synchronization must be verified. Specifically, sends simultaneous timestamp requests to both the blockchain and a trusted time server. Let and denote the timestamps of the full node and the time server that connects to, respectively. We require that the difference value between and should be no more than ,

where denotes the average time of block generation. could choose the connected full node and time server until they satisfy this requirement.

5.2. Contract Deployment

After the initialization phase, the Ivy Oracle could deploy the contract onto the blockchain. To mitigate potential misbehavior from the Ivy server , we incorporate a time-locked deposit mechanism into the contract. Specifically, the entity that deploys is required to lock a deposit within the contract. This deposit acts as a deterrent against dishonest behavior and can be reclaimed by users under the following conditions: (1) does not receive the expected data from the Ivy Oracle before a predefined deadline. (2) receives data that is clearly erroneous, which can be checked by leveraging the majority voting mechanism between multiple blockchain oracles. Specifically, users can provide evidence to the smart contract to redeem the deposits, and the blockchain nodes could check its validation.

5.3. Request Analysis

In this phase, a user initiates a data request by calling the Ivy contract to obtain off-chain information. Similar to Town Crier [12], the user constructs a request and submits it to , where the parameter set is defined in Section 4.3.

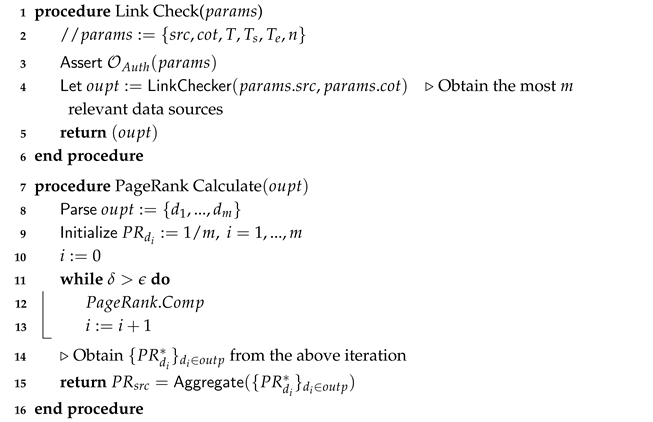

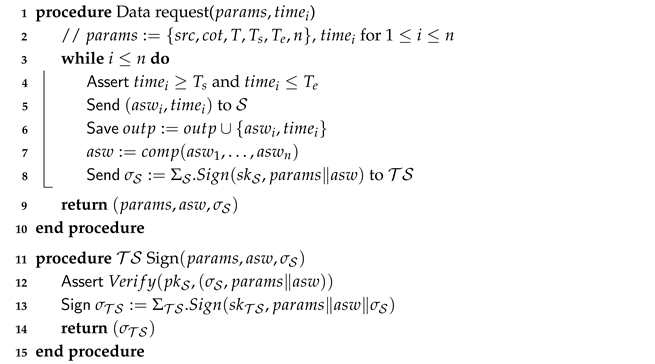

The process of selecting a credible data source is illustrated in Algorithm 1. The Ivy server continuously listens to the blockchain for events emitted by . Once a new request is detected, it retrieves the corresponding data and verifies its authenticity by checking the digital signature. This is handled by the function , which ensures the request originates from a valid blockchain entity.

| Algorithm 1: Data source selection based on LinkChecker and PageRank |

|

To evaluate the trustworthiness of the specified data source , invokes its internal PageRank-based verification module. The process begins with hyperlink analysis using the algorithm, a recursive scanning utility that explores both inlinks and outlinks among HTTP-enabled sources. Based on the discovered hyperlinks, constructs a data relationship graph (DRG) that reflects the interconnection structure among sources.

Let denote the set of data nodes discovered through this process. Each represents a data source that links to or is linked from , forming its semantic or structural neighborhood. For instance, if retrieves data from , then is treated as an inlink. If itself links to , then is considered an outlink. These relationships are encoded in the DRG and used for trust score computation.

The PageRank module then calculates a credibility score for each node in through iterative updates. The initialization step, denoted as , assigns an equal probability to each node , as defined in Equation (2):

where is the number of nodes. For each iteration , the computation step updates the score for each node according to Equation (3):

where denotes a hyperlink from to , is the number of outgoing links from , and is the damping factor, typically set to .

The iteration continues until convergence. The final trust score of is then computed by aggregating the scores of its neighbors:

where represents a user-defined strategy, such as a weighted average or credibility threshold.

To ensure transparency and auditability, the final result is committed to the blockchain. In the event of a dispute, for example, if a user suspects that an incorrect or manipulated data source was used, the committed trust score and the underlying DRG can be publicly verified on-chain.

After structural verification, the Ivy server conducts a timestamp consistency check to evaluate the temporal accuracy of the selected data source. Specifically, simultaneously queries the candidate source and a trusted time server , obtaining timestamps and , respectively. then calculates the absolute time deviation:

If , where is a predefined threshold, the data source is considered temporally reliable and eligible for data acquisition. Otherwise, it is excluded from the current query session and flagged for revalidation.

5.4. Data Retrieval

After the data source has been selected and its temporal reliability verified, the Ivy server proceeds to retrieve the actual data from the target provider . Specifically, as illustrated in Algorithm 2, to ensure temporal coverage and statistical robustness, the Ivy Oracle is required to collect n responses within a specified time interval . For each , generates a timestamp and sends the data query to the data source .

| Algorithm 2: Data retrieval from stable data sources |

|

Upon receiving the query, responds with messages , where denotes the result of the query at timestamp . This interaction is repeated n times to form a result set .

After collecting all valid responses, applies the user-specified aggregation function to compute a consolidated result . This function can implement majority voting, averaging, or any custom logic provided in the initial request.

To anchor the aggregated result to a trusted temporal reference, signs the result together with the query parameters and sends to the time server for temporal certification, where . replies with a signature .

The resulting pair forms a dual attestation of the answer : the former ensures authenticity, while the latter guarantees freshness. These signed results are then packaged into message and returned to the Ivy contract for on-chain verification and delivery to the user.

5.5. Data Delivery

After obtaining both the aggregated result and the timestamp certificate from the time server, the Ivy server transmits back to the Ivy contract deployed on the blockchain. Upon receiving this message, first verifies the timestamp signature using the public key of the time server. This step ensures that the result is anchored to a recent and authenticated timestamp. If the timestamp verification succeeds, proceeds to verify the signature using the public key of the Ivy server to confirm the authenticity of the response.

Once both signatures are successfully verified, invokes the callback function previously specified by the user in the original request. It sends to the user contract . performs the same signature verifications locally to validate the freshness and authenticity of the received data. If either signature verification fails, the result is rejected by the user contract . In this case, the user may initiate an on-chain dispute using the time-locked deposit mechanism embedded in . By providing verifiable evidence, such as an invalid signature or delayed response, the user can claim the locked deposit from the Ivy server as compensation. If both signatures are valid, the result is accepted and used in subsequent on-chain logic, such as conditional execution, automated transactions, or state updates.

6. Security Analysis

In this section, we analyze the security of the Ivy Oracle in terms of data trustworthiness, temporal integrity, and resilience against adversarial behavior.

- Authenticity and Integrity. The final result is accompanied by dual signatures: from the Ivy server and from the time server. These signatures are verified both by the Ivy contract and the user contract before any data is accepted on-chain. This ensures that responses are authentic and tamper-proof.

- Resilience Against Untrusted Data Sources. Given that external sources may return inaccurate or inconsistent values, the Ivy server employs a dual defense strategy. First, it assesses the trustworthiness of candidate sources using a PageRank score derived from the data relationship graph (DRG), built from inlinks and outlinks via hyperlink analysis. This score is committed to the blockchain for transparency and later audit. Second, performs timestamp consistency checks by comparing source time with a trusted time server, filtering out unreliable or manipulated sources.During retrieval, queries the selected source n times and applies a user-defined aggregation function (e.g., majority voting or averaging) over the results. This reduces the impact of individual corrupted responses and mitigates the influence of faulty or adversarial data providers.

- Freshness and Temporal Integrity. The system guarantees that retrieved data is recent and not replayed. This is achieved via two mechanisms: (1) sources are only selected if their clocks are aligned with a trusted time server, and (2) after aggregation, the final result is timestamped and signed by . This signature proves that was computed within the validity window specified in the request, preventing the use of outdated data.

- Dispute Resolution and Verifiability. In the event of incorrect or missing data, users can challenge the Ivy Oracle by invoking the time-locked deposit mechanism. Since the trust score computation, source selection, and timestamp checks are either logged or committed on-chain, any misbehavior can be publicly verified, and the user’s claim can be adjudicated automatically by smart contract logic. This incentivizes honest behavior from the Ivy server.

7. Performance Analysis

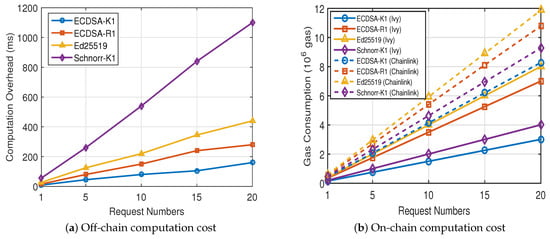

To evaluate the efficiency of the proposed Ivy Oracle, we conduct experiments on both off-chain and on-chain performance, focusing on computational latency and communication overhead. The evaluation includes (i) the computational overhead of digital signature generation and verification under four algorithms—ECDSA-K1, ECDSA-R1, Ed25519, and Schnorr-K1; (ii) the PageRank-based trust evaluation cost; and (iii) the execution time of major protocol phases, including initialization, contract deployment, and data retrieval. The experiments are performed on a laptop equipped with an Intel Core i5 processor, 16 GB RAM, and running Windows 10.

On the off-chain side, we assess the cost of PageRank-based data source selection, TEE and signature generation, and signature verification. As shown in Figure 4a, the computation cost scales proportionally with the number of requests, while maintaining responsiveness suitable for real-time oracle tasks. In particular, Table 2 shows that the PageRank computation overhead grows linearly with the number of requests and remains under 12 milliseconds even for the largest tested configuration. This demonstrates that Ivy Oracle’s trust evaluation mechanism introduces negligible latency while retaining scalability, which is essential for practical deployment in latency-sensitive scenarios. When comparing different signature schemes, ECDSA-K1 consistently incurs the lowest overhead, followed by ECDSA-R1 and Ed25519, whereas Schnorr-K1 shows the highest computational cost due to its heavier verification step.

Figure 4.

Off-chain and On-chain Computation Cost.

Table 2.

Computation overhead of PageRank Algorithm.

In the on-chain comparison, Ivy Oracle is evaluated against Chainlink [16], a representative decentralized oracle network, focusing on the gas cost and calldata size for signature verifications. As shown in Figure 4b and Table 3, Ivy Oracle exhibits lower on-chain gas consumption but slightly higher communication overhead. On average, Ivy Oracle reduces the on-chain gas cost by 32–63.6% across different signature schemes compared with Chainlink, primarily because its lightweight single-enclave architecture and direct timestamp attestation eliminate the need for multi-node aggregation and consensus operations. The slightly increased payload results from its dual-attestation mechanism, where both the Ivy server and the time server provide signatures to ensure timestamp verifiability. We do not perform off-chain comparison with Chainlink, since its decentralized architecture and network-level consensus make off-chain latency inherently incomparable with Ivy’s TEE-based single-server model.

Table 3.

On-chain communication sizes of Chainlink and Ivy using various signature schemes.

To provide a more comprehensive view of system performance beyond cryptographic operations, we further measure the execution time of the major phases in Ivy Oracle, including initialization, contract deployment, and data retrieval. The results are summarized in Table 4. The initialization phase mainly involves key generation, timestamp synchronization, and wallet setup, requiring about 13.241 s. The contract deployment phase, dominated by on-chain contract compilation and deployment, takes approximately 66.779 s, which is a one-time cost amortized over multiple oracle requests. In contrast, the data retrieval phase is highly efficient, completing within 0.132 s per request on average. These measurements confirm that the additional operations introduced by Ivy Oracle incur minimal overhead and do not hinder real-time oracle performance.

Table 4.

Execution Time of different phases.

Overall, the evaluation confirms that Ivy Oracle achieves strong guarantees of source trustworthiness and temporal consistency with minimal additional performance and communication costs, making it well-suited for latency-sensitive and high-integrity smart contract applications.

8. Conclusions

In this paper, we present Ivy Oracle, a robust and flexible data feed framework designed to improve the reliability, timeliness, and verifiability of off-chain information consumed by smart contracts. To address key limitations of existing oracle systems, Ivy Oracle integrates TEEs for secure data acquisition, an external time server for authenticated timestamping, and a PageRank-based trust model for assessing data source credibility. It further supports customizable aggregation strategies, allowing users to adapt data delivery to specific application requirements. We formalize the system model and security assumptions, and implement the core components on the Ethereum Sepolia testnet. Our evaluation shows that Ivy Oracle reduces on-chain gas consumption by up to 63.6% compared with Chainlink for signature verification, maintains low PageRank computation latency, and keeps data retrieval overhead within 0.132 s, despite introducing a slightly higher communication cost. These results confirm that Ivy Oracle achieves a practical balance of robustness, freshness, and verifiability, making it well suited for latency-sensitive blockchain applications.

Future work will focus on extending Ivy Oracle to support decentralized server instances and integrating zero-knowledge-based data attestations to further improve scalability and strengthen privacy guaranties. In particular, decentralizing Ivy Oracle into multiple independent servers coordinated by lightweight consensus can eliminate the single-relay assumption, enhance fault tolerance, and reduce reliance on any single TEE host. Another promising direction is to incorporate zero-knowledge proofs, enabling oracles to attest to the correctness of data acquisition and timestamp validation without revealing raw data, thereby improving both scalability and privacy. Ultimately, combining decentralization with zero-knowledge attestations will pave the way for a fully distributed, privacy-preserving, and verifiably trustworthy oracle ecosystem suitable for large-scale blockchain applications such as DeFi, supply chain management, and IoT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X.; Methodology, H.X.; Software, H.X.; Validation, Y.Y. and K.Z.; Formal analysis, Z.L.; Investigation, Y.Y.; Resources, X.Y.; Data curation, K.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation, H.X.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Y., X.Y., K.Z., Y.L. and Z.L.; Visualization, Z.L. and Y.L.; Supervision, X.Y.; Project administration, X.Y.; Funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the 2024 Digital Technology Platform Adaptive Transformation Project (Trusted Space Construction) under Project No. 037800HK24090095.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors were employed by Guangdong Power Grid Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Dos Santos, S.; Singh, J.; Thulasiram, R.K.; Kamali, S.; Sirico, L.; Loud, L. A new era of blockchain-powered decentralized finance (DeFi)—A review. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 46th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 27 June–1 July 2022; pp. 1286–1292. [Google Scholar]

- Betti, Q.; Khoury, R.; Hallé, S.; Montreuil, B. Improving hyperconnected logistics with blockchains and smart contracts. IT Prof. 2019, 21, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Dedeoglu, V.; Kanhere, S.S.; Jurdak, R. PrivChain: Provenance and privacy preservation in blockchain enabled supply chains. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain), Espoo, Finland, 22–25 August 2022; pp. 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sriman, B.; Kumar, S.G. Decentralized finance (defi): The future of finance and defi application for ethereum blockchain based finance market. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Applied Informatics (ACCAI), Chennai, India, 28–29 January 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, G. Ethereum: A Secure Decentralised Generalised Transaction Ledger. Technical Report, Ethereum Project. 2014. Available online: https://ethereum.github.io/yellowpaper/paper.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Zou, W.; Lo, D.; Kochhar, P.S.; Le, X.B.D.; Xia, X.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xu, B. Smart contract development: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2019, 47, 2084–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Qin, R.; Wang, F.Y. An overview of smart contract: Architecture, applications, and future trends. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Changshu, Suzhou, China, 26–30 June 2018; pp. 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Weng, J.; Weng, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, D.; Xu, G.; Deng, R. IvyCross: A Privacy-Preserving and Concurrency Control Framework for Blockchain Interoperability. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 9334–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniiche, A. A study of blockchain oracles. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.07140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarelli, G. Understanding the blockchain oracle problem: A call for action. Information 2020, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.N.; Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Weng, J.; Imran, M. An overview on smart contracts: Challenges, advances and platforms. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 105, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Cecchetti, E.; Croman, K.; Juels, A.; Shi, E. Town crier: An authenticated data feed for smart contracts. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; pp. 270–282. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Breiki, H.; Rehman, M.H.U.; Salah, K.; Svetinovic, D. Trustworthy blockchain oracles: Review, comparison, and open research challenges. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 85675–85685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Makhdoom, I.; Iqbal, W.; Ahmad, A.; Raza, A. From trust to truth: Advancements in mitigating the Blockchain Oracle problem. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2023, 217, 103672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Zhang, F.; Kos, J.; He, W.; Hynes, N.; Johnson, N.; Juels, A.; Miller, A.; Song, D. Ekiden: A platform for confidentiality-preserving, trustworthy, and performant smart contracts. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), Stockholm, Sweden, 17–19 June 2019; pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Breidenbach, L.; Cachin, C.; Chan, B.; Coventry, A.; Ellis, S.; Koushanfar, F.; Magauran, B.; Miller, A.; Moroz, D.; Nazarov, S.; et al. Chainlink 2.0: Next Steps in the Evolution of Decentralized Oracle Networks. White Paper. 2021. Available online: https://research.chain.link/whitepaper-v2.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Ordoñez, C.C.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, G.; Corrales, J.C. Enhancing Data Integrity in Blockchain Oracles Through Multi-Label Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, S.; Salehi, M.; Gu, W.C.; Clark, J. Sok: Oracles from the ground truth to market manipulation. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM Conference on Advances in Financial Technologies, Arlington, VA, USA, 26–28 September 2021; pp. 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, K.; Zhou, L.; Livshits, B.; Gervais, A. Attacking the defi ecosystem with flash loans for fun and profit. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Virtual, 1–5 March 2021; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, J.; Cao, A.; Skeggs, C.; Belay, A.; Kaashoek, M.F.; Zeldovich, N. Efficiently mitigating transient execution attacks using the unmapped speculation contract. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20), Online, 4–6 November 2020; pp. 1139–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnizo, J.; Szalachowski, P. PDFS: Practical data feed service for smart contracts. In Proceedings of the European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Luxembourg, 23–27 September 2019; pp. 767–789. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, G.; Ryou, J. Smart contract data feed framework for privacy-preserving oracle system on blockchain. Computers 2021, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhu, H.; Yu, B.; Yao, S. Efficient Off-chain Data Feed Mechanism Using a Novel Blockchain Oracle Network Combined with Directed Acyclic Graph-Distributed Ledger. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 2810–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasdar, A.; Lee, Y.C.; Dong, Z. Connect API with blockchain: A survey on blockchain oracle implementation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosba, A.; Miller, A.; Shi, E.; Wen, Z.; Papamanthou, C. Hawk: The blockchain model of cryptography and privacy-preserving smart contracts. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Jose, CA, USA, 23–25 May 2016; pp. 839–858. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, D.L. Network Time Protocol (Version 3) Specification, Implementation and Analysis. Rfc 1305, University of Delaware, 1992. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc1305 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Zheng, W.; Wu, Y.; Wu, X.; Feng, C.; Sui, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Y. A survey of Intel SGX and its applications. Front. Comput. Sci. 2021, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costan, V.; Devadas, S. Intel SGX explained. Cryptology ePrint Archive 2016. Available online: https://ia.cr/2016/086 (accessed on 31 January 2016).

- Lee, D.; Kohlbrenner, D.; Shinde, S.; Asanović, K.; Song, D. Keystone: An open framework for architecting trusted execution environments. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth European Conference on Computer Systems, Heraklion, Greece, 27–30 April 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Haveliwala, T.H. Topic-sensitive pagerank. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on World Wide Web, Honolulu, HI, USA, 7–11 May 2002; pp. 517–526. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, I. The Google Pagerank Algorithm and How It Works. 2002. Available online: http://www.iprcom.com/papers/pagerank/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- McBurney, P.W.; Liu, C.; McMillan, C. Automated feature discovery via sentence selection and source code summarization. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2016, 28, 120–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Yokomori, R.; Fujiwara, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Matsushita, M.; Kusumoto, S. Component rank: Relative significance rank for software component search. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Software Engineering, Portland, OR, USA, 3–10 May 2003; pp. 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gleich, D.F. PageRank beyond the web. Siam Rev. 2015, 57, 321–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, J.; Kiayias, A.; Leonardos, N. The bitcoin backbone protocol: Analysis and applications. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Sofia, Bulgaria, 26–30 April 2015; pp. 281–310. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Weng, J.; Yang, A.; Lu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, L.; Liu, J.N.; Xiang, Y.; Deng, R. CrowdBC: A blockchain-based decentralized framework for crowdsourcing. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2018, 30, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).