Efficient Spiking Transformer Based on Temporal Multi-Scale Processing and Cross-Time-Step Distillation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Spiking Neural Networks

Training of Deep SNNs

- ANN-to-SNN Conversion: Replaces activation functions like ReLU with spiking neurons and adds scaling operations such as weight normalization and threshold balancing to convert pre-trained ANNs into SNNs.

- Surrogate Gradients: Uses continuous differentiable functions to approximate the derivative of the step function, providing gradients during backpropagation. This allows direct training and handling of temporal data with only a few time steps, achieving good performance on both static and dynamic datasets [16].

2.2. Knowledge Distillation

2.3. Spiking Transformer

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Multi-Scale Resolution Processing

3.2. Cross-Time-Step Distillation

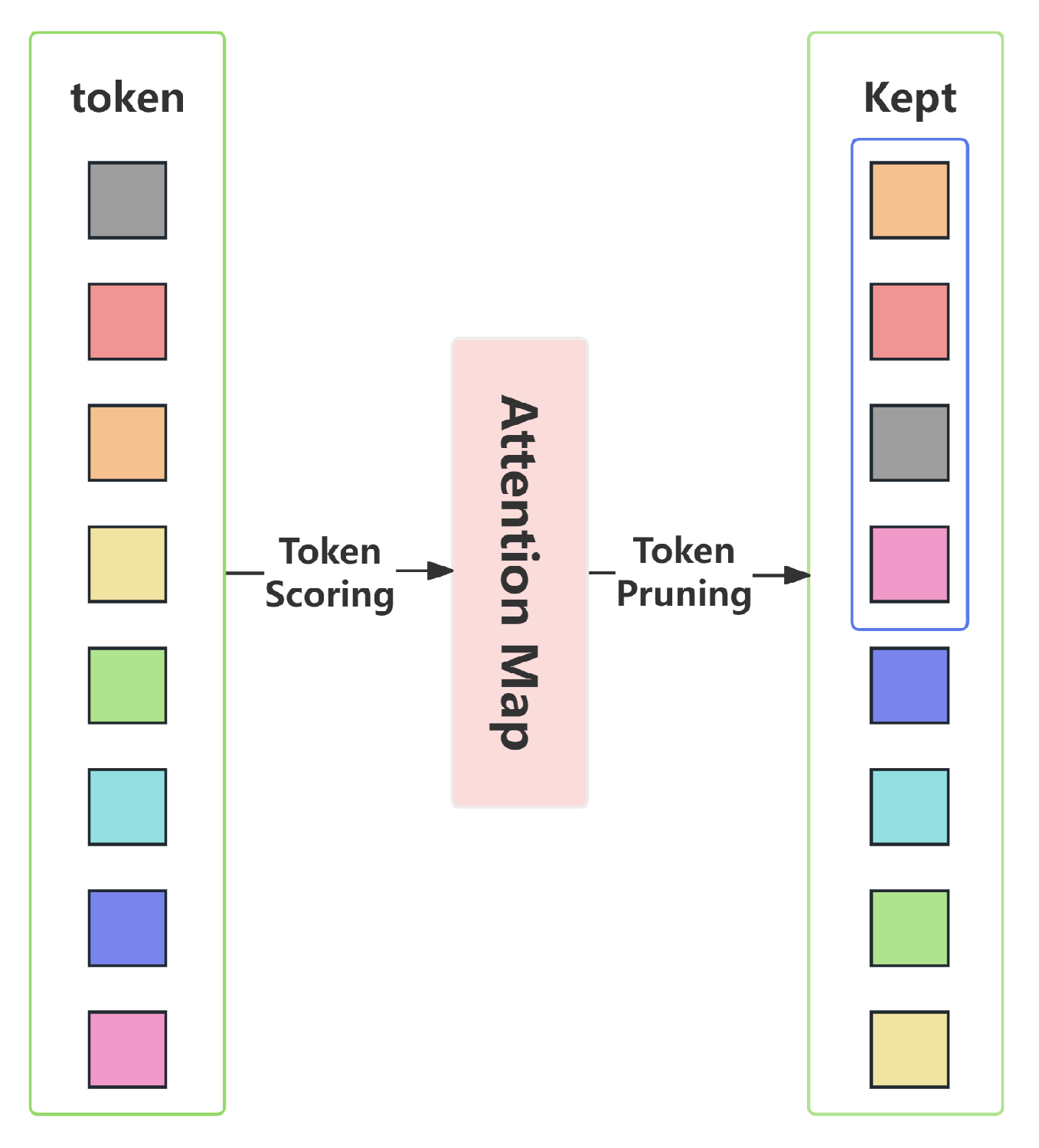

3.3. Attention-Based Token Pruning

3.4. Multi-Scale Feature Fusion

4. Experiments and Results Analysis

4.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

4.2. Results on Static Datasets

4.3. Results on Dynamic Datasets

4.4. Ablation Study

4.4.1. Cross-Time-Step Knowledge Distillation

4.4.2. Attention-Based Pruning

4.4.3. Multi-Scale Resolution Processing

4.4.4. Comparison of Energy Consumption and Computational Complexity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghosh-Dastidar, S.; Adeli, H. Spiking neural networks. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2009, 19, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, W.; Kistler, W.M. Spiking Neuron Models: Single Neurons, Populations, Plasticity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ponulak, F.; Kasiński, A. Introduction to spiking neural networks: Information processing, learning and applications. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2011, 71, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Gotarredona, T.; Linares-Barranco, B. A 128 × 128 1.5% contrast sensitivity 0.9% FPN 3 μs latency 4 mW asynchronous frame-free dynamic vision sensor using transimpedance preamplifiers. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2013, 48, 827–838. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.H.; So, S.K. Using admittance spectroscopy to quantify transport properties of P3HT thin films. J. Photonics Energy 2011, 1, 011112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, M.; Pfeil, T. Deep learning with spiking neurons: Opportunities and challenges. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavanaei, A.; Ghodrati, M.; Kheradpisheh, S.R.; Masquelier, T.; Maida, A. Deep learning in spiking neural networks. Neural Netw. 2019, 111, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.; Simeone, O.; Gardner, B.; Grüning, A. An introduction to spiking neural networks: Probabilistic models, learning rules, and applications. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2019, 36, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images; Technical Report; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, A.; Taba, B.; Berg, D.; Melano, T.; McKinstry, J.; Nolfo, C.D.; Nayak, T.; Andreopoulos, A.; Garreau, G.; Mendoza, M.; et al. A low power, fully event-based gesture recognition system. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7243–7252. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Ji, X.; Li, G.; Shi, L. CIFAR10-DVS: An event-stream dataset for object classification. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 1952, 117, 500–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neftci, E.O.; Mostafa, H.; Zenke, F. Surrogate gradient learning in spiking neural networks: Bringing the power of gradient-based optimization to spiking neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2019, 36, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Li, G.; Zhu, J.; Shi, L. Spatio-temporal backpropagation for training high-performance spiking neural networks. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 331. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Huang, T.; Masquelier, T.; Tian, Y. Incorporating learnable membrane time constant to enhance learning of spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2661–2671. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.; Ballas, N.; Kahou, S.E.; Chassang, A.; Gatta, C.; Bengio, Y. Fitnets: Hints for thin deep nets. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6550. [Google Scholar]

- Kushawaha, R.K.; Kumar, S.; Banerjee, B.; Chaudhuri, B.B. Distilling spikes: Knowledge distillation in spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Virtual, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 4536–4543. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K.; Yu, C.; Zhang, T.; Huang, T. Temporal separation with entropy regularization for knowledge distillation in spiking neural networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.03144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, H.; Pan, G. Constructing deep spiking neural networks from artificial neural networks with knowledge distillation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7886–7895. [Google Scholar]

- Takuya, S.; Zhang, R.; Nakashima, Y. Training low-latency spiking neural network through knowledge distillation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Symposium in Low-Power and High-Speed Chips (COOL CHIPS), Tokyo, Japan, 14–16 April 2021; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; Ning, M.; Song, Z.; Pan, G. Self-architectural knowledge distillation for spiking neural networks. Neural Netw. 2024, 178, 106475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bertasius, G.; Tran, D.; Torresani, L. Long-short temporal contrastive learning of video transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 14010–14020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, Y.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Yan, S.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, L. Spikformer: When spiking neural network meets transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.15425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Che, K.; Fang, W.; Yu, Z.; Tian, Y. Spikformer v2: Join the high accuracy club on imagenet with an snn ticket. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.02020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tian, Y. Spikingformer: Spike-driven residual learning for transformer-based spiking neural network. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.11954. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, L.; Tian, Y. Enhancing the performance of transformer-based spiking neural networks by SNN-optimized downsampling with precise gradient backpropagation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.05954. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, M.; Hu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, L.; Tian, Y. Spike-driven transformer. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 64043–64058. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, C.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Tian, Y. SGLFormer: Spiking global-local-fusion transformer with high performance. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1371290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, L.; Tian, Y. Qkformer: Hierarchical spiking transformer using qk attention. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.16552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Zuo, W.; Fan, X.; Tian, Y. Multi-Timescale Motion-Decoupled Spiking Transformer for Audio-Visual Zero-Shot Learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 10772–10786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Learning Rate | 6 |

| Warm-up Epochs | 5 |

| Weight Decay | 0.05 |

| Batch Size | 256 |

| Epochs | 200 |

| Algorithm Model | Dataset | Improvement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIFAR10 | CIFAR100 | ImageNet-1K | ||

| Spikformer [26] | 95.51 | 78.21 | 74.81 | - |

| Spikformer (Ours) | 96.73 | 78.62 | 75.84 | +1.22/+0.41/+1.03 |

| S-D Transformer [28] | 95.60 | 78.40 | 77.07 | - |

| S-D Transformer (Ours) | 96.82 | 79.12 | 78.62 | +1.22/+0.72/+1.55 |

| SGLFormer [31] | 96.76 | 82.26 | 83.73 | - |

| SGLFormer (Ours) | 97.12 | 83.07 | 84.33 | +0.36/+0.81/+0.60 |

| S-D Transformer V2 [27] | 96.86 | 81.36 | 80.02 | - |

| S-D Transformer V2 (Ours) | 97.37 | 82.07 | 80.75 | +0.51/+0.71/+0.73 |

| QKFormer [32] | 96.18 | 81.15 | 84.22 | - |

| QKFormer (Ours) | 97.02 | 81.92 | 84.76 | +0.84/+0.77/+0.54 |

| Algorithm Model | DVS128-Gesture | CIFAR10-DVS |

|---|---|---|

| Spikformer [26] | 98.30 | 80.90 |

| Spikformer (Ours) | 98.74 | 81.56 |

| S-D Transformer [28] | 99.30 | 80.00 |

| S-D Transformer (Ours) | 99.42 | 80.73 |

| SGLFormer [31] | 98.60 | 82.90 |

| SGLFormer (Ours) | 99.00 | 83.72 |

| Module Configuration | CIFAR10 (%) | CIFAR100 (%) | Power (mJ) | Training Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spikformer [26] (Baseline) | 95.51 | 78.21 | 7.73 | 1.00× |

| + Time-step Distillation | 96.93 | 79.12 | 7.62 | 0.92× |

| + Attention Pruning | 95.21 | 77.92 | 6.82 | 1.38× |

| + Classification Evaluation | 94.11 | 76.37 | 5.11 | 2.42× |

| Full Model (Ours) | 96.73 | 78.62 | 5.43 | 1.82× |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Yang, Z.; Kong, X. Efficient Spiking Transformer Based on Temporal Multi-Scale Processing and Cross-Time-Step Distillation. Electronics 2025, 14, 4918. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244918

Sun L, Li Y, Liu G, Yang Z, Kong X. Efficient Spiking Transformer Based on Temporal Multi-Scale Processing and Cross-Time-Step Distillation. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4918. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244918

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Lei, Yao Li, Gushuai Liu, Zengjian Yang, and Xuecheng Kong. 2025. "Efficient Spiking Transformer Based on Temporal Multi-Scale Processing and Cross-Time-Step Distillation" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4918. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244918

APA StyleSun, L., Li, Y., Liu, G., Yang, Z., & Kong, X. (2025). Efficient Spiking Transformer Based on Temporal Multi-Scale Processing and Cross-Time-Step Distillation. Electronics, 14(24), 4918. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244918