Abstract

The transition to electric vehicles (EVs) plays a critical role in reducing global carbon emissions. However, the end-of-life management of electric vehicle batteries (EVBs) presents significant sustainability and operational challenges. This study proposes a blockchain-based framework that enables full lifecycle tracking of EVBs, from production to disposal or reuse, while addressing issues of transparency, efficiency, and regulatory compliance. The framework incorporates a multi-criteria decision model to guide data-driven end-of-life routing—whether for second-life reuse or direct recycling—based on technical, environmental, and economic indicators. By integrating smart contracts with a hybrid web/mobile platform, the system ensures tamper-proof documentation, stakeholder accountability, and compliance with the EU battery passport regulation. A detailed cost analysis of deploying the framework on Ethereum is also presented. The proposed solution aims to enhance the sustainability of EVB management, reduce environmental impact, and promote circular economy practices within the EV industry.

1. Introduction

Electric vehicles (EVs) are important in the fight against climate change and carbon emissions, mainly due to their potential to reduce dependence on fossil fuels and improve energy efficiency. Usage of the EVs is very important because they have zero tailpipe emissions, which is a direct contribution to better air quality and reduced greenhouse gas emissions in urban areas. Switching from fuel-powered vehicles to EVs is crucial in the modern context of global efforts to limit temperature rise to a certain threshold and reduce the effects of climate change. This criticality is underscored by the fact that transportation is one of the major contributors to carbon emissions [1]. In addition, there is support for the shift to EVs through the development of renewable energy sources, which can also further reduce the carbon footprint of EVs. When EVs are powered by renewable energy, their overall emissions are very small compared to conventional ones that run on fossil fuel sources. This synergy between the adoption of EVs and the integration of renewable energy is the key to achieving net zero emission targets and will foster a sustainable energy future.

The management of electric vehicle batteries (EVBs) is a critical issue in the life cycle of EVs to ensure the environmental benefits of EVs. As EVBs degrade and lose capacity with age, repurposing them for secondary uses, such as energy storage, extends their useful life and reduces waste [2]. This practice will maximize resource efficiency and contribute to the circular economy aiming to minimize waste [3].

The end-of-life phase of EVBs presents several challenges that must be addressed to ensure sustainable and efficient battery lifecycle management. As EV batteries age, their capacity gradually diminishes until they can no longer function reliably in electric vehicles, prompting the need for appropriate downstream strategies. These batteries may either be repurposed for secondary applications—such as stationary energy storage—or recycled to recover valuable active materials. Selecting the most suitable route is critical for extending battery lifecycle, minimizing waste, and reducing the demand for raw materials. However, the sector currently lacks standardized and well-coordinated procedures for the collection, reuse, recycling, and final disposal of EVBs. Existing systems often operate in a fragmented manner across manufacturers, recyclers, and consumers, leading to significant gaps in traceability and proper management. Without a uniform governance framework, improper handling can result not only in resource losses but also in environmental harm, reinforcing the need for a circular economy approach that prioritizes material recovery and responsible recycling [4]. Recent advances in secure and decentralized communication technologies within intelligent transportation systems highlight the potential of blockchain to strengthen trust, transparency, and coordination among diverse stakeholders. For example, Tan et al. demonstrate how blockchain-assisted conditional anonymous authentication and group key agreement mechanisms can ensure secure, tamper-resistant interactions in dynamic vehicular environments [5]. Likewise, Sutrala et al. propose a conditional privacy-preserving batch verification scheme for Internet of Vehicles deployments, underscoring the role of efficient on-chain verification in enhancing data integrity and system scalability [6]. These developments illustrate how decentralized authentication and secure data-sharing frameworks can address systemic trust and coordination issues in multi-actor ecosystems similar to the EVB supply and recovery chain. Motivated by these insights, our study leverages blockchain’s transparency and immutability to create a unified, trustworthy mechanism for tracking EVBs throughout their lifecycle while enabling automated and objective end-of-life routing decisions.

Blockchain technology may be an appropriate solution to the challenges related to end-of-life management of EVBs. Particularly, it provides an enhanced traceability and transparency throughout each stage of the battery life cycle. Blockchain technology can help to ensure that the information is recorded on an immutable, decentralized ledger at every stage from production to eventual disposal of the batteries. This would ensure that stakeholders are in a position to trace the origin, usage, and end-of-life status of each battery. This increases accountability and reduces the chances of fraud in recycling processes. Beyond this, integration of smart contracts into blockchains will enable the automation and acceleration of several processes concerning batteries. Smart contracts are designed to establish agreements that bind manufacturers, recyclers, and consumers by enforcing regulations regarding battery disposal and recycling demands. For instance, with a smart contract in action, when a battery reaches a point where, conventionally, its life would be considered ended, it will autonomously undertake the duties of recycling mechanisms. This automation can reduce administrative burdens and improve operational efficiency [7].

Blockchain technology offers a significant advantage in enhancing collaboration among diverse stakeholders throughout the battery product lifecycle. Acting as a shared platform, blockchain facilitates seamless communication and coordination between manufacturers, recyclers, and regulatory agencies. The shift towards a circular economy model depends on such collaboration at every stage of the cycle [4,8]. By fostering trust among stakeholders, blockchain encourages active participation in sustainability efforts through transparent information sharing. It simultaneously supports traceability and builds confidence among participants to achieve the goals of environmental policy [7,9]. In addition, it enhances the economics in recycling processes, hence having traceable material with a full transaction trail. With such transparency in place, recyclers will find it easy to identify values of materials contained in the waste batteries for better profitability and efficiency of the operations of recycling.

Blockchain technology can go a long way in addressing the challenge of end-of-life management in EV batteries through enhanced traceability, process automation via smart contracts, collaboration among multiple stakeholders, and allowance for cost-effective solutions. In such context, blockchain technology has emerged as a potent tool to implement best practices in battery management. Considering the growing traction electric vehicles are gaining these days, the application of blockchain technology becomes all the more vital in addressing complex issues related to batteries at the end of their life cycle.

This study introduces a blockchain-based framework designed to address the challenges associated with the end-of-life phase of electric vehicle batteries (EVBs). The proposed system enhances transparency, traceability, and regulatory compliance while tackling critical inefficiencies in current battery recycling processes. In particular, it addresses key obstacles such as fragmented stakeholder coordination, insufficient lifecycle tracking, and suboptimal decision-making regarding the downstream use of retired batteries.

A distinctive contribution of this work lies in the integration of a multi-criteria optimization model that enables fully data-driven and explainable end-of-life routing decisions for EV batteries—determining whether a battery should be repurposed for second-life applications or sent to material recycling. Unlike many existing blockchain-based EVB traceability frameworks, which primarily focus on recording lifecycle events, the proposed system addresses a critical gap in the literature by moving beyond simple SOH-based heuristics and incorporating a comprehensive set of technical, economic, and environmental criteria. This structured decision model allows stakeholders to evaluate trade-offs transparently, apply configurable weighting schemes, and make balanced, quantifiable choices that reflect operational and sustainability priorities. By embedding this optimization mechanism within a decentralized architecture powered by smart contracts, the framework not only enforces recycling and reporting obligations but also ensures full alignment with the European Union’s Battery Passport Regulation, which mandates digital traceability for batteries above 2 kWh starting in 2024.

The scope of the study spans both conceptual and practical dimensions. On the theoretical side, it explores the benefits of blockchain and smart contracts in ensuring transparency and compliance across the battery lifecycle. Practically, the proposed system is implemented as a web and mobile application, enabling real-time interaction with blockchain-based smart contracts for various stakeholders in the EVB supply chain.

Specifically, the study focuses on

- -

- Enabling end-to-end lifecycle tracking of EV batteries, from manufacturing to reuse or recycling.

- -

- Automating stakeholder roles and obligations through smart contracts to reduce manual overhead.

- -

- Introducing a multi-criteria optimization model to support objective, traceable end-of-life decisions.

- -

- Aligning the system with emerging sustainability policies and regulatory frameworks.

Through these contributions, the study aims to support the development of scalable, transparent, and sustainable EV battery management systems that balance operational efficiency with environmental responsibility.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of EVB recycling, highlighting the lifecycle of EVBs, current recycling practices, and their limitations. Section 3 introduces blockchain technology, its principles, and its applications. In Section 4, we propose a blockchain-based framework tailored to EVB recycling, detailing its key features, integration with existing waste management systems, and smart contract implementation. Section 5 details the creation of the suggested hybrid framework that combines blockchain technology with web applications. It enables stakeholders to interact with Ethereum-based smart contracts via mobile and web platforms. Section 6 evaluates the expenses linked to executing the proposed framework on the Ethereum blockchain. Section 7 concludes the paper by summarizing the results and providing recommendations for future studies.

2. Overview of Electric Vehicle Battery Recycling

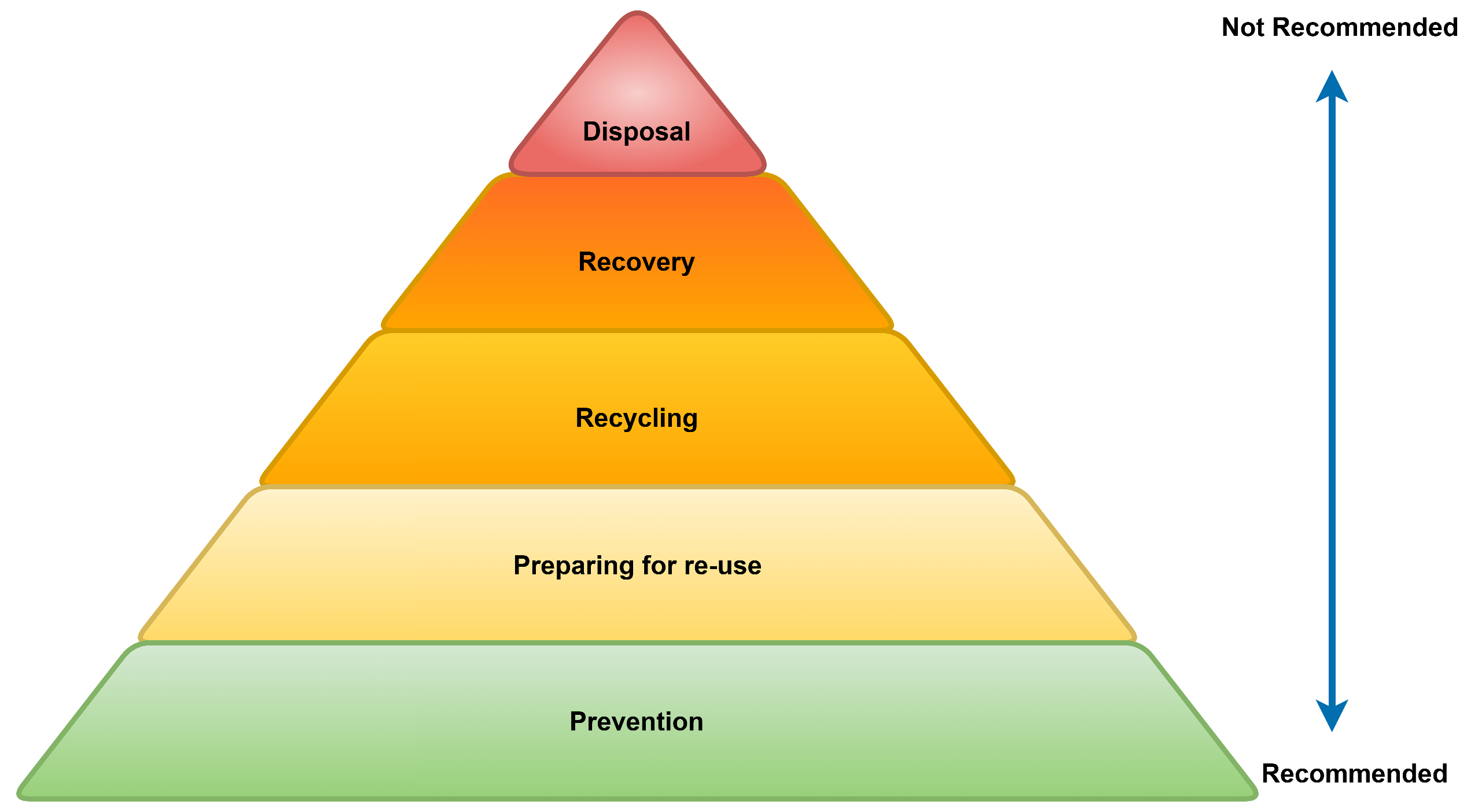

The importance of creating sustainable economic value increases with each passing day. The economic approach of the European Union has also been established within the framework of a sustainable economic model. Central to this model is the waste management framework, providing a system aimed at maximizing recyclability from production through to consumption and promoting production methods that enhance recycling [2,10]. The waste management hierarchy implemented in the European Union is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The waste management hierarchy implemented in the European Union.

The waste management hierarchy illustrated in Figure 1 represents a core concept of recycling and the sustainable economy, with its levels explained below.

Prevention aims to minimize the environmental impact and conserve natural resources by eliminating waste generation at its source. This layer represents the most effective and sustainable approach to waste management.

Reuse focuses on reevaluating waste without consuming resources or causing environmental harm. This reduces the need for raw materials to produce new products and diverts waste from the stream.

Recycling involves transforming waste materials into new products, aiming to reuse resources and reintegrate them into the economy, thereby reducing waste accumulation and environmental impact.

Energy Recovery focuses on extracting usable energy from waste instead of discarding it in landfills or through environmentally harmful methods. This approach not only minimizes the environmental footprint of waste but also conserves resources used for energy generation.

Disposal is considered the last option in the waste management hierarchy and is primarily used for waste that poses risks to the environment or cannot be repurposed. It emphasizes safe handling of hazardous waste while aiming to reduce the overall volume.

EVBs, like other products, are designed to align with the principles of the waste management hierarchy, as depicted in Figure 1. To reinforce these principles, the European Union introduced the Battery Passport Regulation in 2023, slated for implementation in 2024. This is the new ruling that demands all batteries above 2 kWh be embedded with a digital battery passport, enabling full traceability of the life cycle and carbon footprint of these batteries according to given waste management priorities [10].

After manufacturing, EVBs are installed in vehicles and act as their main energy source. Their performance degrades with aging. Once the capacities of these batteries are reduced, they are usually considered for reuse in secondary applications. Currently, one of the fast-growing solutions is to apply EVBs in renewable energy systems for energy storage. This not only prolongs the life cycle of the battery but also contributes to a greener future in general [2,11].

A circular economy of EVBs needs strong reverse supply chains for their collection, refurbishment, and recycling at the end of their first life. Reverse supply chains help minimize dependence on virgin resources by recovering valuable materials, thus reducing environmental degradation [3,8]. Disposal of retired EVBs is still a significant challenge, and improper disposal methods lead to the degradation of the environment and the loss of resources. In order to solve this challenge, effective recycling processes need to be established for critical material recovery such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel for re-introduction into the supply chain. Advanced recycling techniques, hydrometallurgy, and pyrometallurgy, together with standardized protocols, can greatly enhance the efficiency and sustainability of these efforts [2,3].

The lifecycle management of EVBs relies on the manufacturers. The companies are supposed to incorporate end-of-life considerations into their designs, guided by the principles of extended producer responsibility. It holds manufacturers responsible for the full life cycle of their products, from production to disposal, thereby encouraging sustainable practices within the industry.

IoT and blockchain will revolutionize the EVB lifecycle management landscape by introducing digital technologies. These tools allow for real-time monitoring of battery performance, enabling predictive maintenance and optimizing usage. They bring complete transparency in the supply chain, helping various stakeholders track batteries throughout their lifecycles, from production to end-of-life disposal [12].

3. Blockchain Technology

Blockchain technology gaining prominence across various industries and expanding its application areas. As the foundation of Web 3.0, this technology has evolved from being merely a concept to becoming a robust framework capable of addressing diverse challenges and enabling effective solutions. This section delves into the fundamental concepts of blockchain technology.

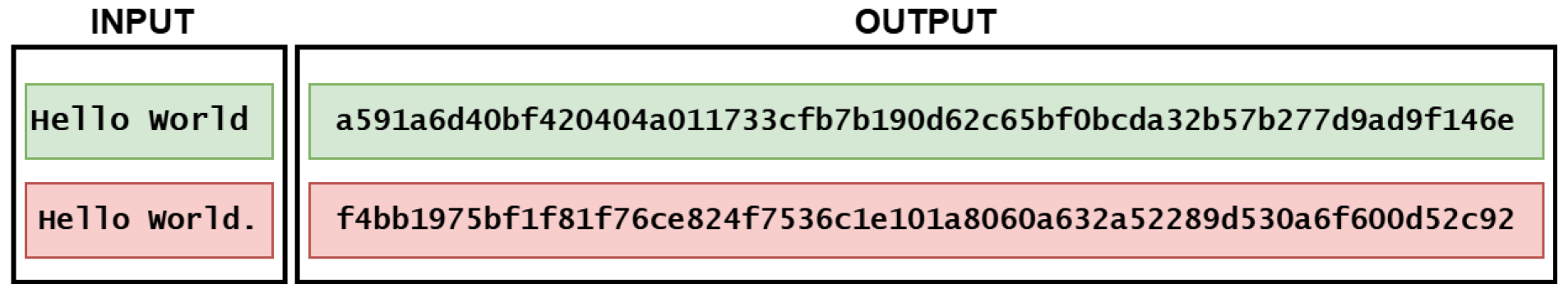

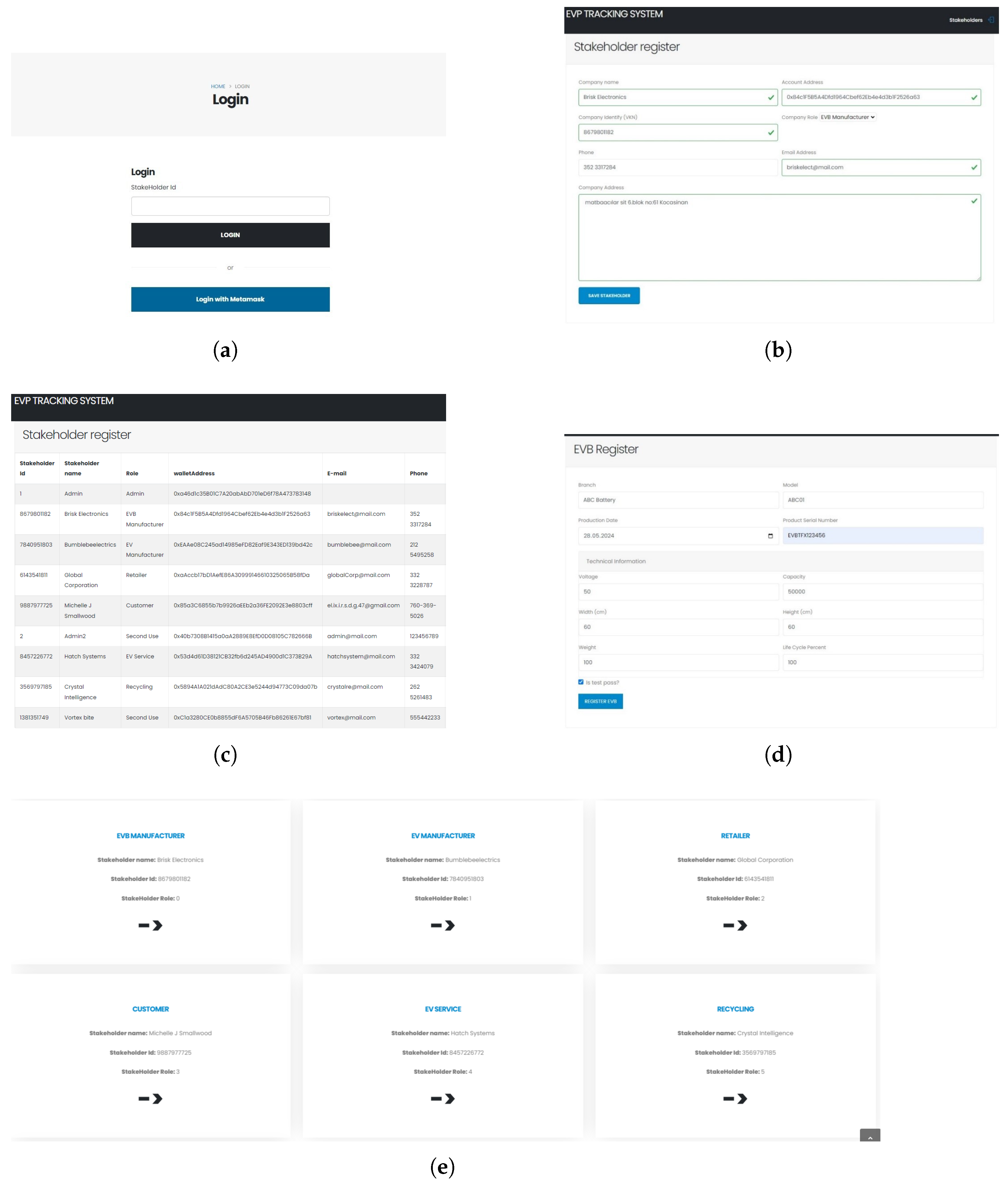

The blockchain operates as a decentralized ledger where data are organized into blocks linked via cryptographic hashes. This unique architecture ensures that each block maintains a reference to its predecessor, preserving the integrity and security of the chain [13,14]. At its heart, the blockchain relies on cryptographic hash functions to validate the authenticity of the data, making even minor changes detectable. For instance, the SHA-256 algorithm, widely employed in blockchain systems, guarantees tamper resistance by generating distinct outputs for each input. The sensitivity of hash functions is illustrated in Figure 2, where small data alterations result in completely different hash outputs.

Figure 2.

Hash function demonstration.

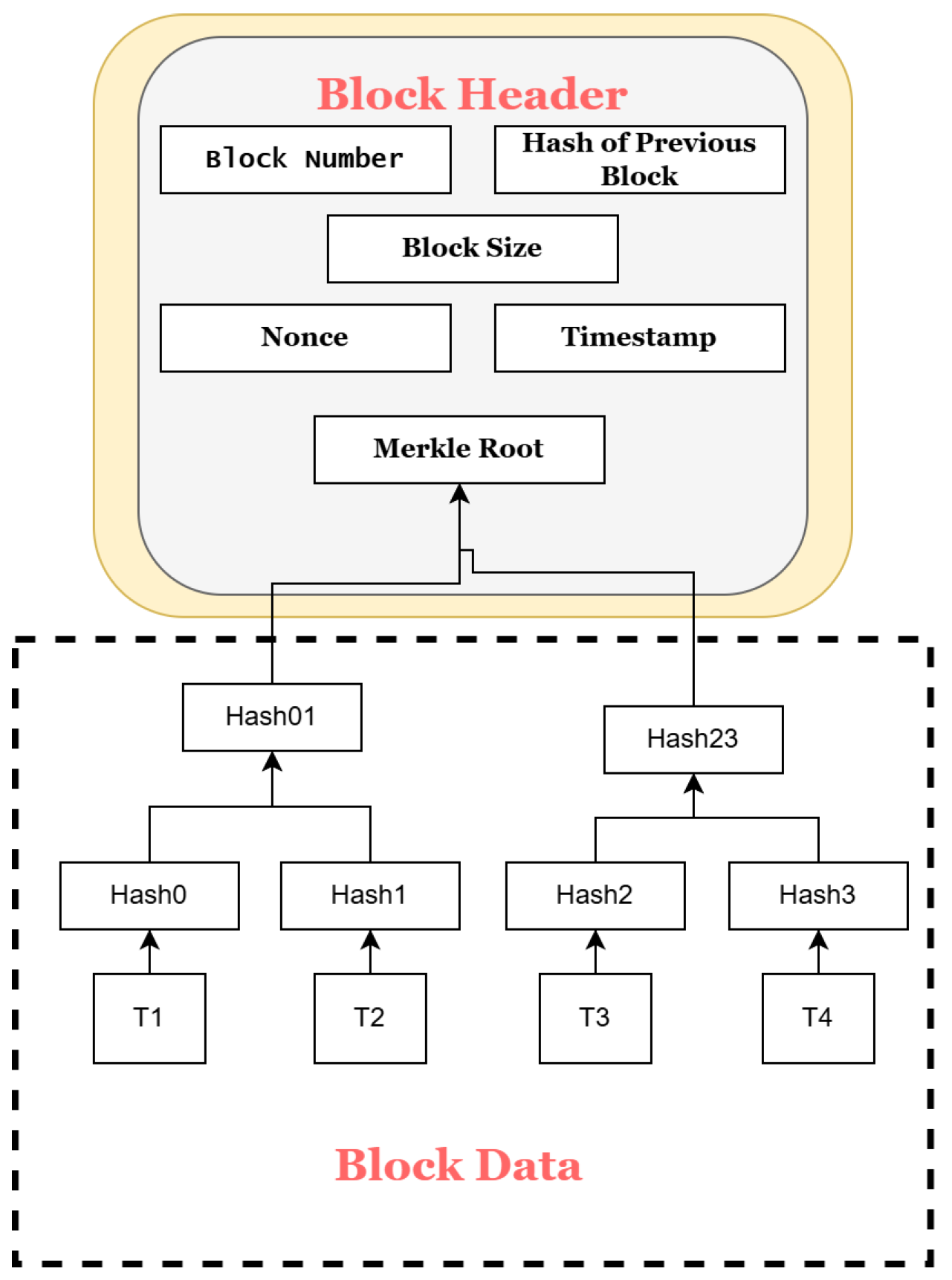

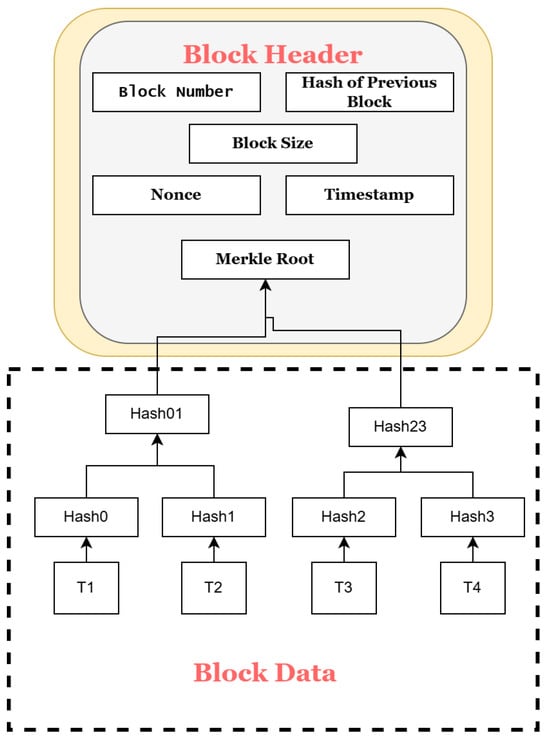

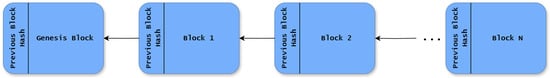

Blocks are the fundamental building units of a blockchain, and their interconnected structure underpins the security and reliability of the entire system [15,16]. Each block is composed of two primary components: the block header and the block data. The header of the block includes metadata such as the timestamp, a unique identifier of the block (nonce) and a cryptographic hash of the previous block. The structure of the block header is shown in Figure 3. The block data contains the list of verified transactions included in that block. This structure ensures that each block is securely linked to its predecessor.

Figure 3.

The structure of the block header.

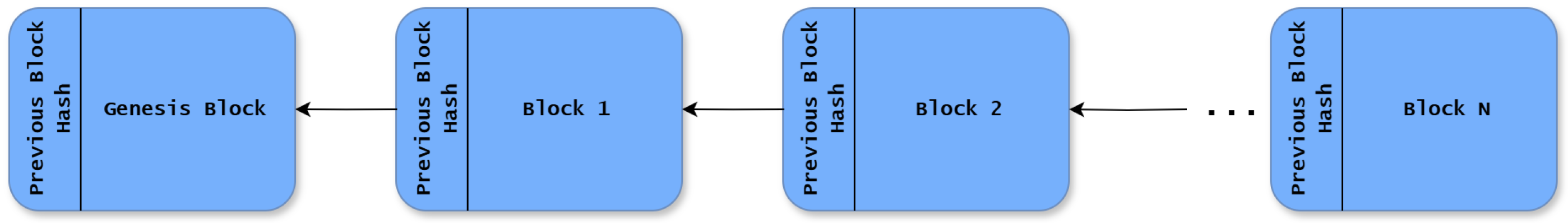

The chaining of blocks is achieved through the inclusion of the previous block’s hash in the current block header. This mechanism creates a dependency, such that altering any data in a block requires recalculating the hashes of all subsequent blocks [17]. Figure 4 provides a visual representation of the block structure and its interlinking through cryptographic hashes. This design makes the blockchain tamper resistant, as any modification to a single block would invalidate the hashes of all subsequent blocks, signaling unauthorized changes. The use of hash functions and their irreversible properties further enhances security by ensuring that data cannot be feasibly reversed or altered once committed to the blockchain.

Figure 4.

Blockchain structure.

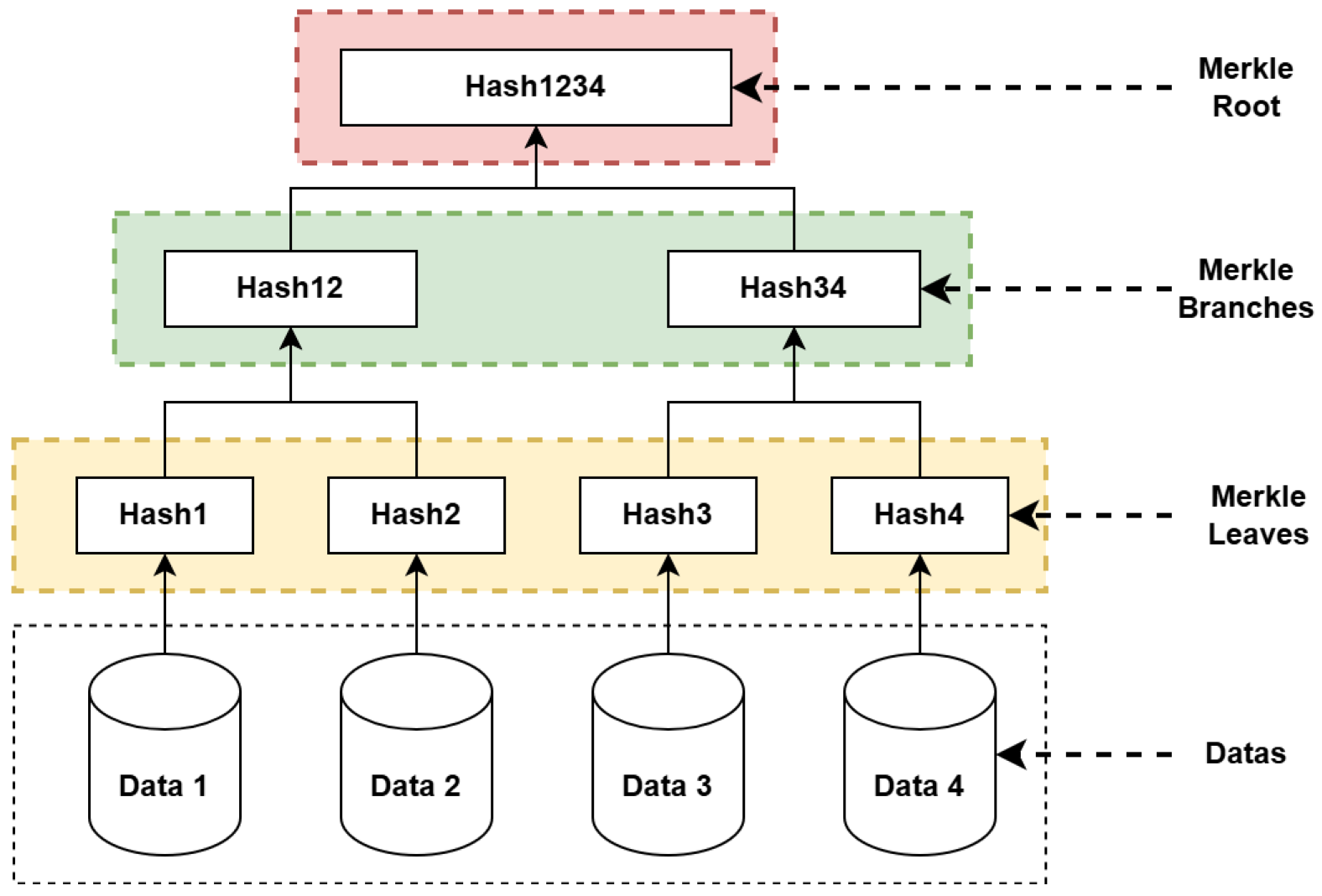

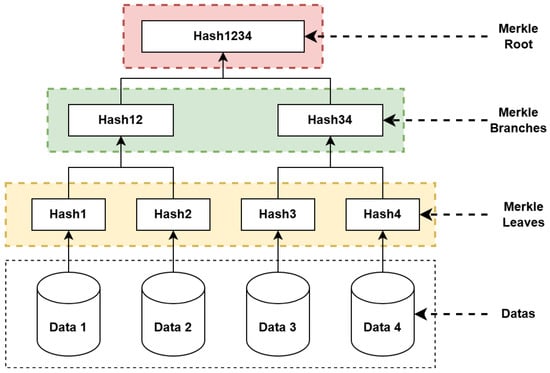

The root hash value for all data contained in the block is determined using Merkle trees. Merkle trees within each block facilitate efficient transaction verification. As depicted in Figure 5, the transactions are hashed and combined in pairs, forming a hierarchical structure that culminates in a single root hash stored in the block header. This Merkle root summarizes all transactions in the block, enabling quick and secure verification without needing to check each transaction individually.

Figure 5.

Merkle tree structure.

As the amount of data in the blockchain grows, it becomes necessary to append new blocks. The process of adding blocks is governed by consensus mechanisms that validate the legitimacy of new blocks before adding them to the chain [18]. These mechanisms, such as Proof of Work (PoW) and Proof of Stake (PoS), play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of the blockchain. Miners solve complex mathematical challenges, whereas validators stake cryptocurrency assets to achieve consensus.

The distributed nature of blockchain ensures redundancy and reliability. Each node on the network maintains a copy of the entire blockchain, making it highly resistant to loss or manipulation of data. This decentralized architecture, combined with cryptographic security, underpins the robustness of the blockchain.

On the application aspect of this research, Ethereum technology, leveraging blockchain technology as its foundation, was utilized. Ethereum, spearheaded by Vitalik Buterin, extended blockchain’s capabilities by introducing smart contracts and decentralized applications (dApps) [19]. Central to Ethereum’s functionality is the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), a universal environment for processing smart contracts and transactions. Smart contracts represent a transformative application of blockchain technology. By automating processes through predefined conditions, smart contracts ensure transparency and operational efficiency [20,21]. These contracts have found widespread use in supply chain management, where they can trigger payments upon delivery verification, thereby reducing administrative overhead and improving reliability.

4. Proposed Blockchain Framework for EV Battery Recycling

This section introduces a blockchain-based framework designed to manage the identity, tracking, and recovery processes of EVBs throughout their lifecycle. The proposed system enables transparent and tamper-proof tracking of all stakeholders involved, from manufacturing to recycling or second-life use. In addition to supporting data traceability and lifecycle accountability, the framework incorporates a multi-criteria optimization model to guide end-of-life decisions. This model helps determine whether each battery should be reused or recycled, based on a balanced evaluation of technical, economic, and environmental factors.

4.1. Electric Vehicle Battery Life Cycle and Stakeholders

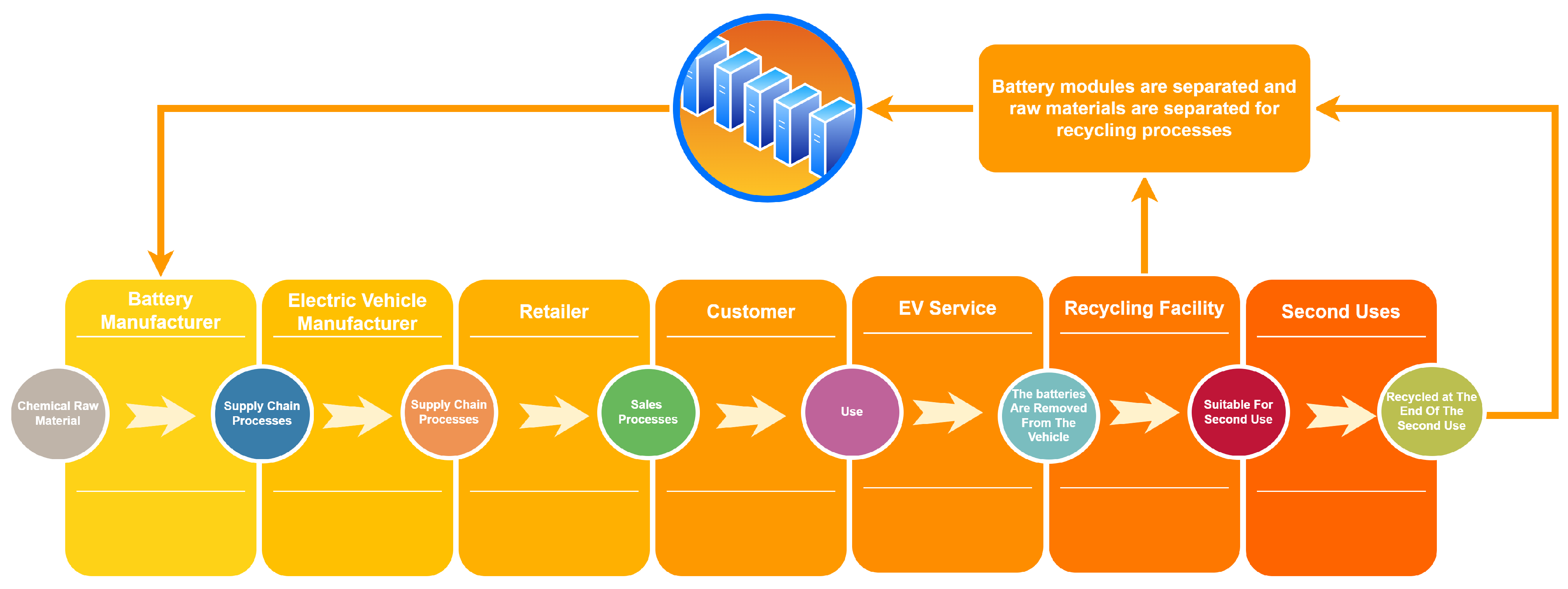

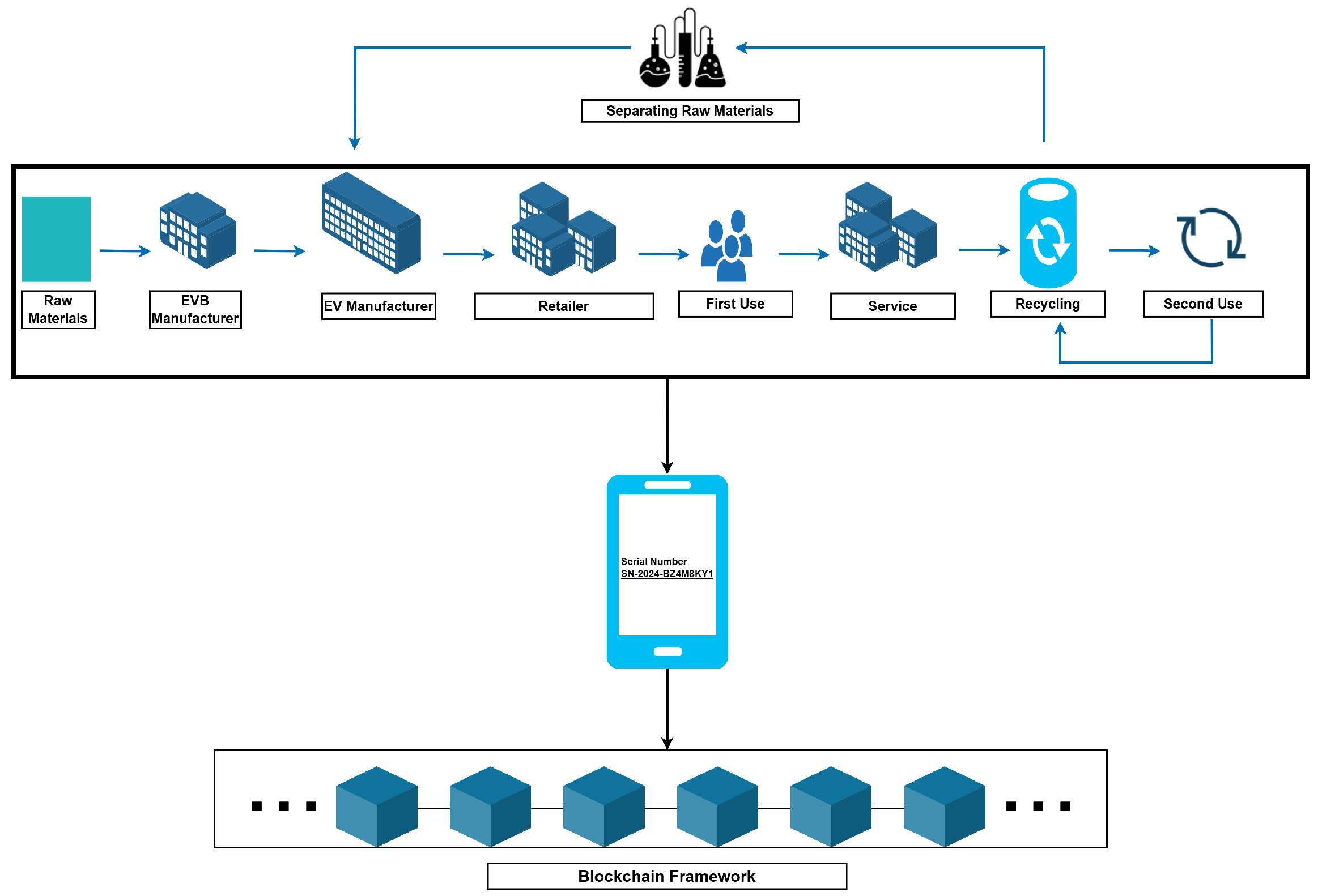

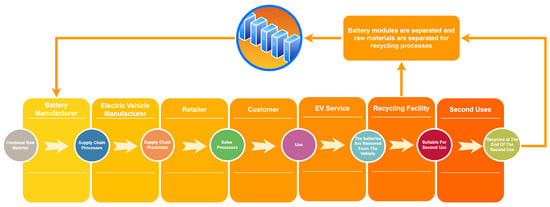

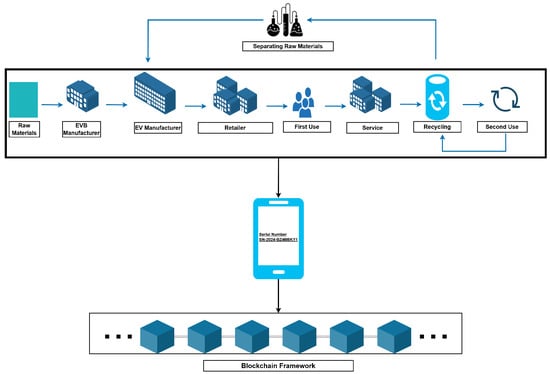

Figure 6 illustrates the life cycle of EV batteries (EVBs), covering the entire process. The cycle includes seven key stakeholders who sequentially interact with the EVBs from production to the completion of their life cycle. These stakeholders and the life cycle were determined based on standard EVB production processes and designed according to the waste management hierarchy [2,10,22]. Each stage within the life cycle is concisely outlined below.

Figure 6.

Life cycle of EVBs, covering the entire process from production to recycling.

Battery manufacturers are the primary stakeholders responsible for producing EVBs. Batteries produced from raw materials are sold to electric vehicle manufacturers. In the proposed system, after production EVBs are immediately registered on a blockchain with a unique serial number. Also, technical details such as battery size, weight, capacity, voltage, cycle count/state of health, production date, and manufacturer information are added to the blockchain. This creates a digital identity for each battery, enabling traceability.

Electric vehicle manufacturers are stakeholders who assemble batteries into their vehicles after procuring them from battery manufacturers. In this system, electric vehicle manufacturers scan the serial numbers of the batteries they receive and update the EVB identity with information such as the vehicle brand, model, assembly date, and manufacturer details. This information is then recorded on the blockchain. Moreover, the battery status is updated to “Electric Vehicle Manufacturer”.

Retailers are stakeholders who sell vehicles produced by electric vehicle manufacturers to customers. Retailers scan the serial numbers of the EVBs in the vehicles they receive, update the battery status to “Retailer”, and add retailer-specific information to the EVB identity. These data are subsequently recorded on the blockchain.

Customers are stakeholders who purchase electric vehicles from retailers and are identified as the first owners. The serial numbers of the EVBs in the purchased vehicle are scanned, the EVB status is updated to “Customer”, and customer-specific information is added to the EVB identity and recorded on the blockchain. Furthermore, during the customer’s use of the vehicle, data such as battery health status and cycle count are regularly uploaded to the blockchain. This process aligns with the concept of smart electric vehicles, which rely on cloud technologies to manage vehicle data and software updates through a network.

Service centers represent the stakeholder group where electric vehicles are brought for battery lifespan or performance issues. At these service points, the serial numbers of the removed batteries are scanned, relevant information is added to the EVB identity, and these data are recorded on the blockchain. Batteries collected at the service centers are then sent to recycling facilities.

Recycling facilities are where EVBs received from service centers are inspected and recycled. At these facilities, the suitability of EVBs for second-life use is determined. If suitable, the EVB serial number is scanned, and information such as the recycling facility details and the “suitable for second use” status is added to the EVB identity and recorded on the blockchain. If the EVB is found unsuitable or is already in “Second Use” status, the recycling facility details and the “not suitable for second use” status are added to the EVB identity, which is then updated to “Recycling” on the blockchain.

The Second Use stakeholder group consists of individuals who utilize EVBs considered suitable for second-life applications from recycling centers. The serial number of the EVB is scanned and information about the second-use stakeholder is added to the EVB identity and recorded on the blockchain.

4.2. Multi-Criteria Optimization Model for Battery End-of-Life Decision

End-of-life (EoL) EVBs are required to be routed either to second-life reuse or material recycling. While earlier methods have typically emphasized a limited number of economic or environmental indicators, real-world decisions are influenced by a wider array of technical, financial, and sustainability criteria. In this section, an extended multi-criteria decision model (MCDM) is presented, through which each battery is evaluated based on several normalized parameters, scaled from 1 (least desirable) to 10 (most desirable). The optimal route for each battery is determined by maximizing an aggregated utility function, thereby ensuring a transparent and data-driven decision-making process.

The set of batteries under consideration is denoted by I. For each battery , a binary decision variable is defined as follows:

Each battery is evaluated across a set of K parameters. For reuse, the following is defined:

- -

- : score of battery i on criterion k under reuse scenario;

- -

- : score of battery i on criterion k under recycling scenario.

Typical criteria may include remaining state-of-health (SOH), cost of refurbishing, resale value in second-life markets, emissions avoided, risk of safety incidents, recyclability index, material recovery efficiency, savings from material substitution, logistical complexity, and regulatory compliance value. The number of criteria K can be adapted as needed.

Let denote the weight assigned to criterion k, such that . These weights reflect stakeholder preferences or policy priorities and can be set by decision-makers. For example, an environmentally driven organization might assign higher weights to emissions-related criteria.

The total utility scores for reuse and recycling are defined as follows:

The objective is to maximize the overall utility from routing decisions:

This formulation ensures that for each battery, the model selects the path—reuse or recycle—that delivers the highest utility based on all available criteria.

Subject to

Constraint (2) enforces binary decisions. Constraint (3) prevents batteries with state-of-health below a specified threshold from being routed to reuse. This reflects industry norms that batteries with, for example, SOH below 70% are not eligible for second-life deployment.

The use of normalized scores between 1 and 10 allows for flexible, modular evaluation across diverse criteria, and supports a decision process that is easily explainable to stakeholders. If all are set equally (e.g., for ), the model represents an unweighted average. If policymakers or companies prioritize environmental goals, they may increase for emissions-related parameters, effectively steering the decision process toward more sustainable outcomes.

To strengthen the practical relevance and operational coherence of the proposed framework, the MCDM has been fully integrated into the smart contract layer. The MCDM procedure is invoked automatically within the recycling stage, allowing the blockchain to execute the end-of-life routing decision without manual intervention from stakeholders. When a battery reaches the recycling facility, the smart contract internally computes the reuse and recycling utility scores using the weighted criteria, normalized performance indicators, and the defined SOH threshold. The resulting decision—whether the battery is suitable for second-life reuse or must be directed to material recycling—is determined on-chain and recorded immutably as part of the EVB’s lifecycle state.

4.2.1. Illustrative Case Example for Model Validation

To validate the practical performance of the proposed multi-criteria decision model, a synthetic dataset of five end-of-life EV batteries () was developed. Each battery was evaluated under both reuseand recycling scenarios across five normalized criteria:

- -

- Health status (HS);

- -

- Refurbishment or recycling cost;

- -

- Market value or material recovery value;

- -

- Environmental benefit;

- -

- Safety risk (inverse scale).

All scores were normalized to a range of 1–10. The SOH threshold for reuse eligibility was fixed at

Table 1.

Normalized scores for reuse scenario ().

Table 2.

Normalized scores for recycling scenario ().

Table 3.

Measured SOH and reuse eligibility.

The weighting score for each criterion is given below:

Utility Scores

Routing Decisions

Only qualifies for second-life reuse, while the remaining batteries are routed to recycling due to either inferior reuse utility or insufficient SOH. The coherence of decisions across different weighting structures demonstrates the robustness and adaptability of the proposed optimization model to varying policy priorities and stakeholder preferences. Table 4 summarizes the final routing decisions for each battery based on the calculated utility scores and SOH constraints.

Table 4.

Routing decisions with sustainability-oriented weights.

4.3. Smart Contracts

Within the suggested framework, process management is facilitated through the use of smart contracts powered by blockchain technology. These smart contracts are self-executing agreements with predefined rules that automatically execute actions when certain conditions are met. Within the system, two primary smart contracts are utilized: the Stakeholder Contract and the EVB Identity Contract. Both contracts are developed using the Solidity programming language and implemented with the REMIX IDE, a popular tool for building and deploying Ethereum-based smart contracts.

4.3.1. Stakeholder Contract

The Stakeholder Contract is responsible for managing the details and roles of the various stakeholders involved in the EVB lifecycle. This contract defines eight distinct roles, each aligned with specific stages and functions within the EVB lifecycle. These roles ensure that the responsibilities and interactions of each stakeholder are clearly defined and governed throughout the process.

- -

- EVBManufacturer: Defines the stakeholder responsible for the manufacturing of EVB.

- -

- EVManufacturer: Defines the stakeholder responsible for the manufacture of EVs.

- -

- Retailer: Defines the retailer involved in the system.

- -

- Customer: Defines the customer in the system.

- -

- EVService: Defines the EV service providers.

- -

- Recycling: Defines the recycling facility.

- -

- SecondUses: Defines the stakeholders involved in the second-use process.

- -

- Admin: Represents the institution/organization that manages the contract, adding, and editing stakeholders.

The Stakeholder Contract additionally keeps the subsequent details for each stakeholder. A user with the Admin role submits these data:

- -

- Name: Defines the title of the stakeholder.

- -

- WalletAddress: The public key of the Ethereum wallet associated with the stakeholder. With this information, regulatory institutions can access account details and balances related to the stakeholder.

- -

- Id: Defines the identification number assigned to companies or individuals by regulatory institutions based on current processes. Allows the integration of external systems with the smart contract.

- -

- CompanyLocation: Address of the stakeholder.

- -

- Phone: The phone number of the stakeholder.

- -

- Email: The email of the stakeholder.

- -

- Role: Defines the role of the stakeholder, as mentioned above.

In the Stakeholder Contract, the user who deploys the contract on the blockchain is assigned the Administrator role, which represents the regulatory institution or organization. The Administrator is responsible for registering, managing, and updating stakeholders within the smart contract. A user with the Administrator role can register a stakeholder by collecting the necessary information and executing the createStakeholder function, which records the stakeholder on the blockchain or updates the existing information. The Stakeholder Contract presents a structure that enables comprehensive management of stakeholder roles and data during the EVB lifecycle.

4.3.2. EVB Identity Contract

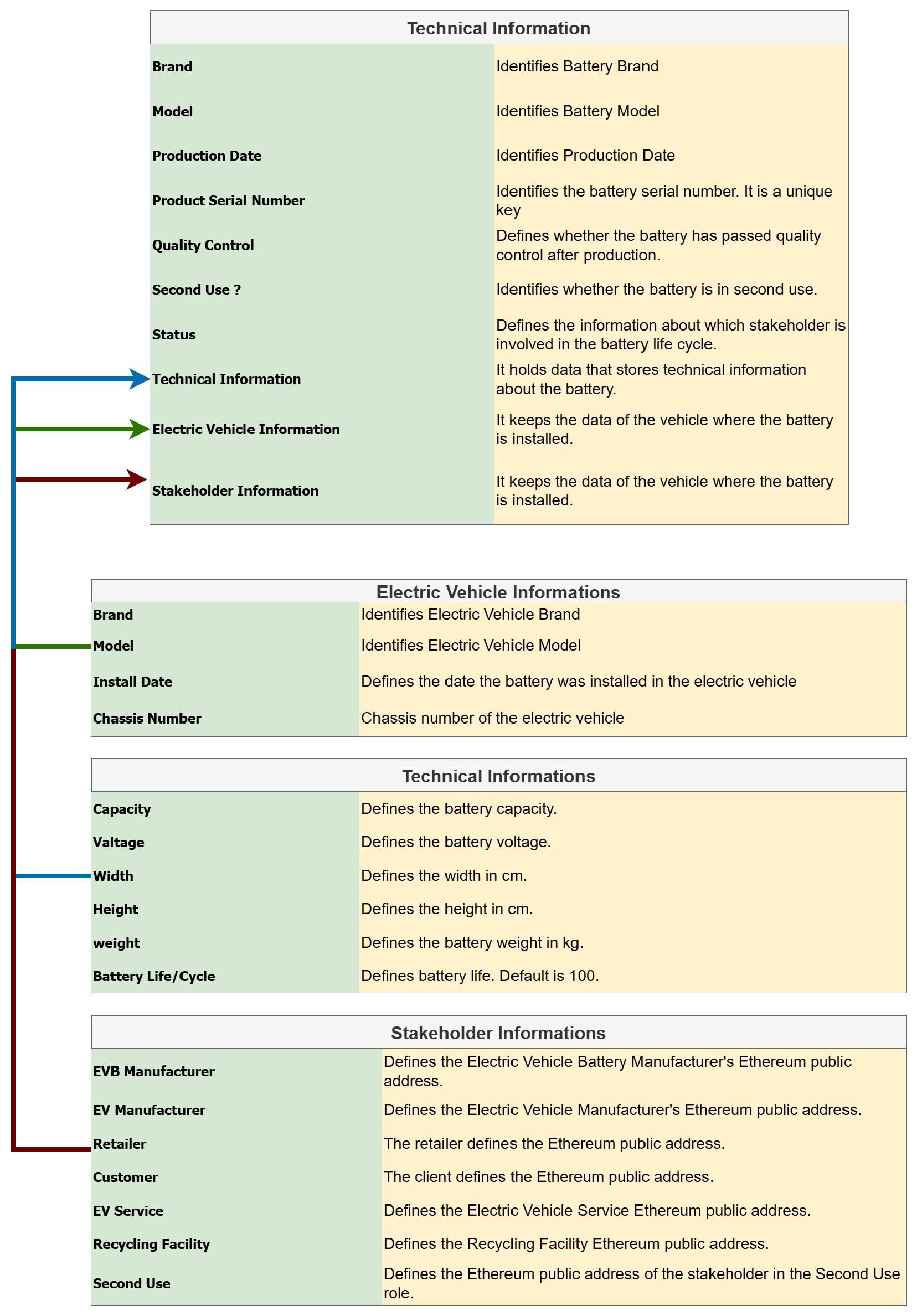

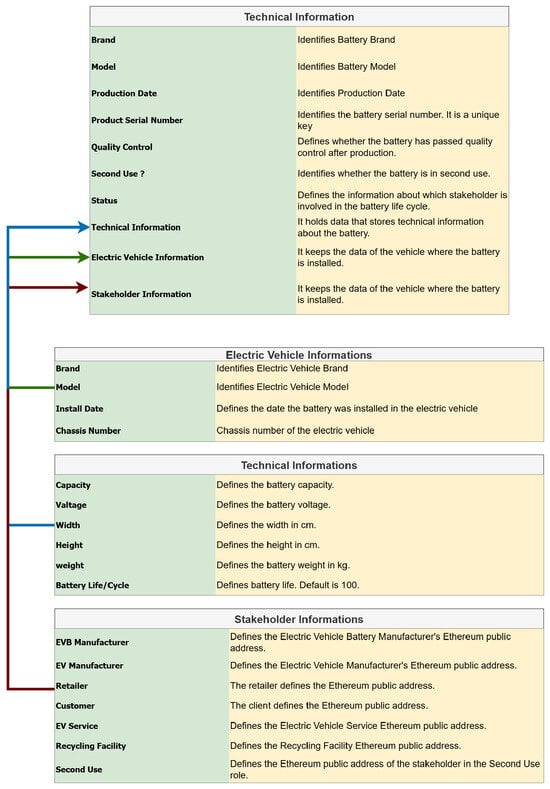

The EVB Identity Contract is designed to define and manage the identities of EVBs. The system ensures the tracking and management of critical information at each stage. The contract is organized into four key categories, each serving a specific purpose in storing essential data: General Information, Technical Information, Electric Vehicle Information, and Stakeholder Information. Together, these categories facilitate comprehensive lifecycle management by capturing the relevant status, specifications, and stakeholder details associated with each EVB.

The General Information category contains the basic details of the EVB. This includes brand, model, production date, unique serial number, quality control status, second-use suitability, and lifecycle stages. These details are registered on the blockchain by the EVB manufacturer.

The Technical Information category covers the physical and performance characteristics of the EVB. This includes data such as height, width, weight, battery capacity, voltage, and battery life that the electric vehicle battery manufacturer adds.

The Electric Vehicle Information category includes data on the EV to which the EVB is integrated. This information comprises the vehicle’s brand and model, chassis number, and assembly date. These details are recorded by the electric vehicle manufacturer.

The Stakeholder Information category maintains the public Ethereum addresses related to stakeholders. This category plays a crucial role in ensuring transparency and traceability by securely linking stakeholders to their respective blockchain identities.

The relationships between the categories are visualized in Figure 7. The General Information category is directly related to the Stakeholder Information, Technical Information, and Electric Vehicle Information categories. These relationships are defined using the Solidity struct data structure, which helps to organize the information systematically across categories and ensures the integrity of the system.

Figure 7.

Category diagram of the EVB identity contract. Blue arrows represent the technical information, green arrows represent the electric vehicle information, and red arrows represent the stakeholder information.

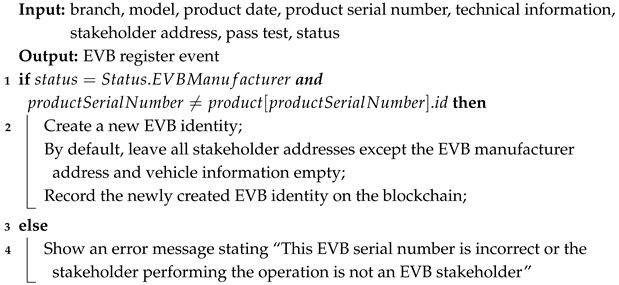

The EVB identity contract is designed to facilitate the creation and management of EVB identities. Two essential verifications are conducted in the EVB identities creation procedure, as illustrated in Algorithm 1. The first verification involves confirming the uniqueness of the serial number for the battery being registered. The second verification requires ensuring that the stakeholder executing the action possesses the EVB manufacturer role. Upon successful completion of these verification steps, the EVB identity is created and registered on the blockchain.

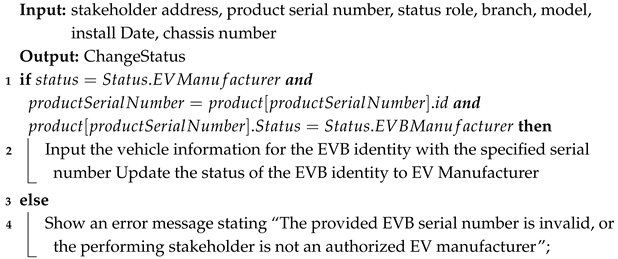

The EVB identity that has been created is upgraded to EV Manufacturer status by calling the change status EV manufacturer method in the contract. The flow of the algorithm for this method is shown in Algorithm 2. As input to this method, the EV manufacturer provides information about the vehicle in which the battery will be integrated. Before proceeding, it is verified that the battery serial number exists on the blockchain, that the current status of the battery is assigned to the EVB manufacturer, and that the transaction details are correctly recorded. The stakeholder performing the operation is an EV manufacturer. Following these verifications, vehicle data is inscribed on the EVB ID, the status of the EVB ID is revised to reflect the EV manufacturer, and the information is stored on the blockchain.

| Algorithm 1: Register EVB: Algorithm for registering a new EVB on the blockchain. This process validates the serial number and ensures that the operation is performed by a legitimate EVB manufacturer. If valid, it creates a new EVB identity with default values and records it on the blockchain. Otherwise, it prompts an error message for invalid serial numbers or unauthorized stakeholders. |

|

| Algorithm 2: Change status EV manufacturer: Algorithm for updating the status of an Electric Vehicle Battery (EVB) to reflect its assignment to an Electric Vehicle (EV) Manufacturer. The process verifies the serial number, checks the current status of the EVB, and ensures the operation is performed by an authorized EV manufacturer. If valid, it updates the EVB identity with vehicle information and changes its status. Otherwise, an error message is displayed for invalid serial numbers or unauthorized actions. |

|

An EVB identifier associated with an EV in the role of an EV producer can be updated to the next role, that of a retailer, using the changeStatusRetailer method. This method requires two inputs: the EVB serial number and the account address of the stakeholder in the retailer role. Using this input, the system performs checks to ensure that the battery serial number exists on the blockchain, that the battery’s status is currently in the EA producer role, and that the stakeholder initiating the transaction is authorized as a retailer. Once these checks are successfully validated, the status of the EVB identifier is provided to the retailer.

When an electric vehicle equipped with an EVB is sold by a retailer to a customer, the EVB’s status is updated for the customer using the changeStatusCustomer method. Similar to the retailer method, this method requires the EVB serial number and the account address of the stakeholder in the customer role as input. Based on this information, the system verifies that the battery serial number exists on the blockchain, that the battery status is currently in the retailer role, and that the stakeholder initiating the transaction is authorized as a customer. Following these verifications, the EVB identifier’s status is updated and communicated to the customer and recorded on the blockchain.

Additionally, the changeLifeCycle method in the contract is used to update the battery lifecycle of the EVBs in the customer role. This method ensures that the battery can be tracked throughout its entire lifecycle, providing valuable information for recycling processes. Furthermore, the presence of such a method in the contract enables automated updates of the battery status on the blockchain through application programming interfaces (APIs) in next-generation smart electric vehicles.

The contract contains the changeStatusEVService method to change the status of the EVB from a customer to an EV service. This method, similar to the others, requires the EVB serial number and the account address of the stakeholder in an EV service role. It performs checks to ensure that the battery serial number exists on the blockchain, that the battery’s status is currently in the customer role, and that the stakeholder initiating the transaction is authorized as an EV service provider.

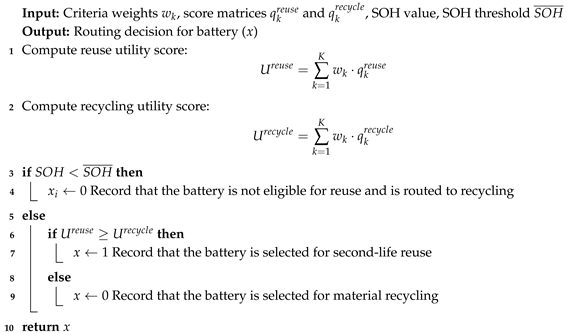

Algorithm 3 formalizes the decision-making logic of the proposed MCDM by computing the relative utility of second-life reuse and direct recycling for battery. The algorithm evaluates all criteria using their assigned weights, aggregates the normalized performance scores, and applies the SOH threshold as a mandatory eligibility constraint. By comparing the resulting utility values, the algorithm determines the optimal routing outcome and outputs a binary decision variable indicating whether the battery should proceed to second-life applications or be directed to material recovery.

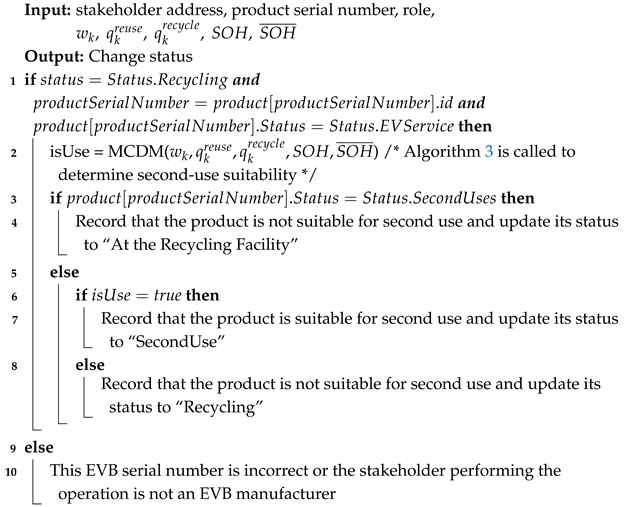

The recycling or second-use processes of an EVB are carried out in collaboration with the stakeholder assigned to the recycling role. When an EVB arrives at an electric vehicle service center and is removed from the vehicle, its transition to the recycling stage is executed through the changeStatusRecycling method defined in the smart contract. Algorithm 4 presents the procedure, which incorporates embedded MCDM to autonomously determine second-use suitability. Before the decision process begins, the system verifies that the EVB’s serial number is registered on the blockchain, that its current status is “Electric Vehicle Service,” and that the stakeholder initiating the operation possesses the recycling role. Once these conditions are satisfied, the smart contract invokes the MCDM algorithm (Algorithm 3) internally. This algorithm evaluates the battery’s weighted criteria scores together with its SOH value and SOH threshold, producing an automated on-chain decision indicating whether the battery is suitable for second-life reuse. If the computed decision is positive, the EVB’s status is updated to “SecondUse” and the information is recorded on the blockchain. If the MCDM evaluation determines that the battery is unsuitable for reuse, the EVB identifier is updated to “Recycling” and recorded accordingly. In both cases, the account address of the recycling stakeholder is appended to the EVB record, ensuring that all actions remain transparent, traceable, and tamper-proof. Through this integration, the routing of EVBs no longer depends on stakeholder judgment but is performed fully automatically by the smart contract logic.

| Algorithm 3: MCDM Algorithm for Determining EVB End-of-Life Routing. The algorithm computes reuse and recycling utility scores based on weighted criteria, checks SOH eligibility, and assigns each battery to second-life reuse or material recycling. Ineligible or low-utility batteries are routed directly to recycling. |

|

| Algorithm 4: Change status recycling: This algorithm updates the status of an EVB by combining conventional recycling verification steps with MCDM procedure. The smart contract internally calls the MCDM function (Algorithm 3) to autonomously determine whether the battery is suitable for second-life reuse based on its technical condition, weighted criteria scores, and SOH threshold. The final routing decision—either “SecondUse” or “Recycling”—is executed on-chain. |

|

If an EVB is considered suitable for the second use, the changeStatusSecondUses method is activated. Similar to other methods, the EVB serial number and the account address of the relevant stakeholder are checked. Once these checks are validated, the EVB status is updated to ‘second use’, and the stakeholder’s account address is appended to the identifier, recording all changes on the blockchain.

5. Framework Implementation

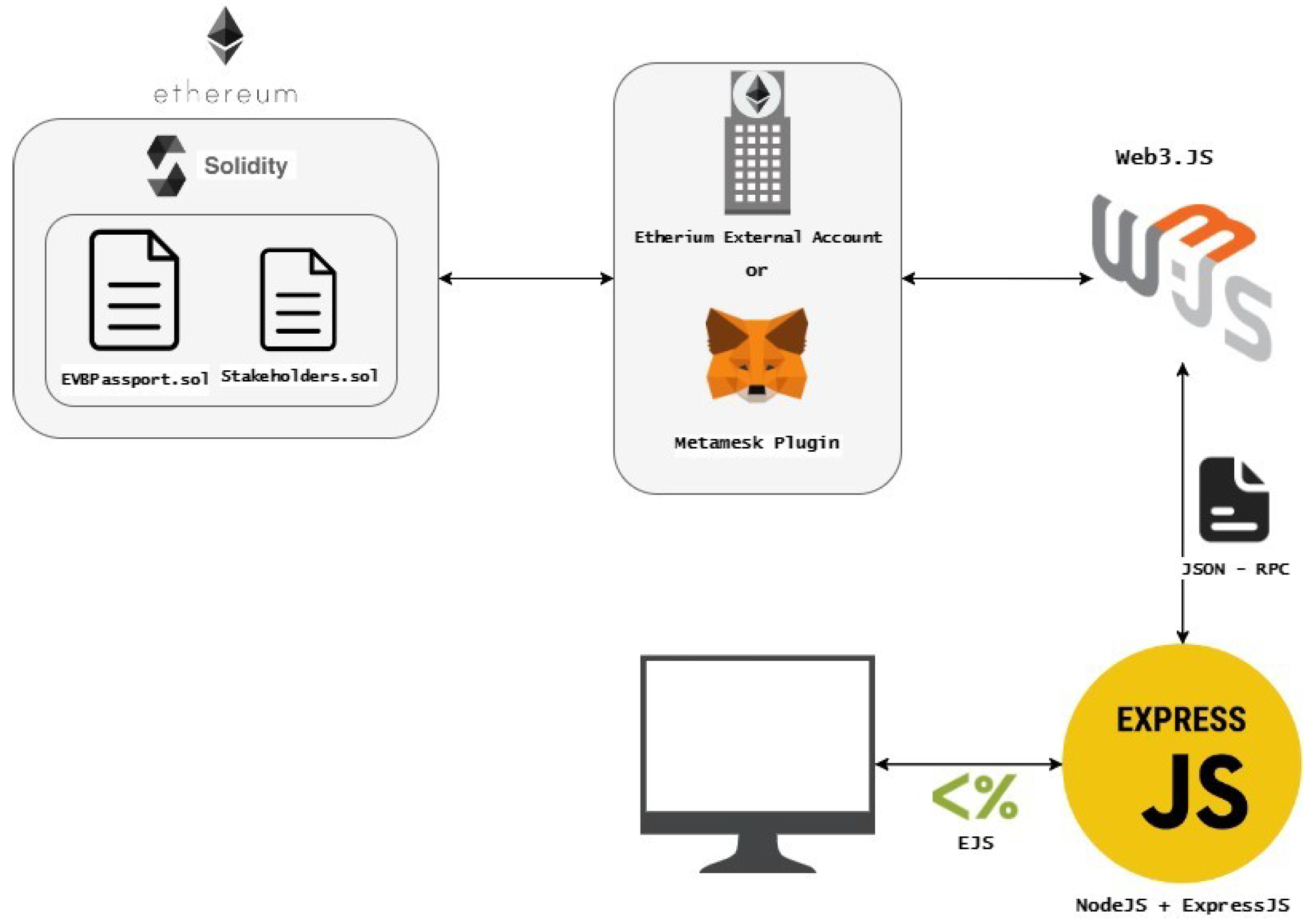

The architecture of the proposed framework is designed to operate as a hybrid system, combining blockchain technology with traditional web applications. It supports a dual-layer structure in which stakeholders can interact with Ethereum-based smart contracts, regardless of the underlying system they use.

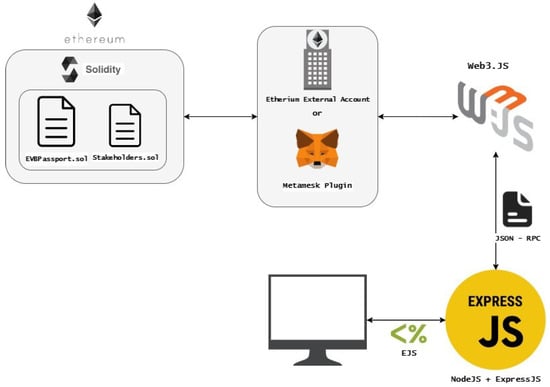

The architecture design, as illustrated in Figure 8, integrates the Ethereum blockchain technology with traditional web systems to facilitate the interaction between stakeholders and smart contracts. At the core, smart contracts (EVBPassport.sol and Stakeholders.sol) are developed using Solidity and deployed on the Ethereum blockchain to securely manage data and processes. Stakeholders interact with these contracts via Ethereum external accounts or the MetaMask plugin, which acts as a digital wallet interface. The Web3.js library serves as a communication bridge, enabling data retrieval and interaction with the blockchain in JSON-RPC format. This data is processed through an Express.js backend, which creates APIs to translate blockchain data into formats compatible with traditional applications. Finally, the front-end leverages the EJS templating engine to dynamically present the processed data in a user-friendly web interface. This architecture ensures a smooth integration of Web 3.0 decentralized components with Web 2.0 systems.

Figure 8.

Application architecture.

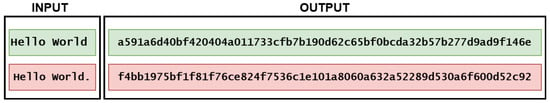

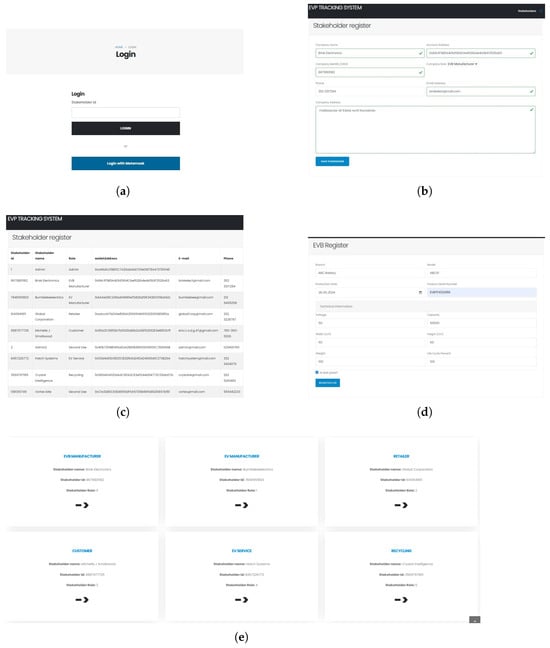

In Figure 9, the scenario and processes of the software are illustrated. The process in the implemented framework begins with a user in the “Administrator” role who adds and manages stakeholders according to the Stakeholder smart contract. The stakeholders then log in to the system using their ID or MetaMask wallets, as shown in Figure 10. The login process is handled by the getCompany() method within the Stakeholder smart contract, which verifies whether the user attempting to log in is registered as a stakeholder on the blockchain. Upon successful verification, access to the system is granted.

Figure 9.

Diagram illustrating the operation of the designed software.

Figure 10.

The web-based software developed for implementing the proposed blockchain-based EVB tracking framework provides user-friendly interfaces to manage and monitor the system effectively. The figures include (a) the login page for accessing the system, (b) the stakeholder registration page for adding new participants to the framework, (c) the stakeholder list page for viewing registered stakeholders, (d) the EVB registration page for recording new EVBs into the system, and (e) displaying the current status of an EVB, along with its associated stakeholders. These interfaces ensure seamless interaction with the blockchain while maintaining transparency and efficiency in the EVB lifecycle management.

Figures from some modules of the software are provided in Figure 10. These images illustrate key interfaces that support various functionalities within the system. The login page (Figure 10a) offers a secure entry point for users, allowing authentication via stakeholder ID or MetaMask wallet. The stakeholder registration page (Figure 10b) enables the addition of new stakeholders with essential details such as their name, role, and wallet address. The stakeholder list page (Figure 10c) provides an overview of all registered stakeholders, enhancing transparency and management. The EVB registration page (Figure 10d) facilitates the entry of detailed information about electric vehicle batteries, ensuring they are securely recorded on the blockchain. Finally, Figure 10e displays the current status of EVBs and provides a detailed view of the stakeholders involved with each EVB throughout its lifecycle. Together, these interfaces highlight the software’s comprehensive design and usability.

When the smart contract is deployed on the blockchain, the user account that runs the contract is assigned the ‘Administrator’ role. When a user with administrator privileges logs into the application, their information is verified on the blockchain, and the stakeholder role data is returned to the application.

If the user is verified to possess the administrator role, the screen for adding stakeholders, as illustrated in Figure 10b, is displayed. In alignment with the contract, the necessary data for the new stakeholder, including name, Ethereum address, identification number, position, contact details, and address information, are gathered and recorded. The createStakeHolder() method, as implemented within the Stakeholder Smart Contract, carries out the recording process.

6. Operational Cost of the Framework on the Ethereum Platform

The framework proposed in this study introduces certain costs when deployed on a blockchain. In this section, the framework was implemented on the Ethereum blockchain to evaluate its feasibility. A cost analysis based on the Ethereum blockchain is conducted to assess the operational expenses of the system. It is important to emphasize that the proposed framework is not restricted to Ethereum and can be integrated with other blockchain platforms. The cost figures shown here may vary depending on the specific blockchain infrastructure utilized. This analysis seeks to offer theoretical insight into the possible expenses associated with the deployment of the framework.

On the Ethereum network, gas acts as a fundamental metric for evaluating the computational resources necessary for processing transactions or running smart contracts. Diverse operations on the Ethereum blockchain, including data storage, variable management, loop execution, conditional logic processing (such as if-else statements), mapping utilization, and data manipulation, demand gas. The gas consumption amounts of the smart contracts designed in the proposed system are detailed in Table 5. Upon examination, the operation with the highest gas costs is the deployment of the smart contracts to the Ethereum blockchain network. Nevertheless, the cost associated with deployment is a one-time expense incurred at the initiation of the application.

Table 5.

Expenses associated with the proposed framework’s transactions on the Ethereum Network.

Through an examination of costs at the individual operation level, it was concluded that the top three expenses are associated with the operations of adding a stakeholder, creating an EVB identity, and changing the status of an EV manufacturer. The reason for these high costs is that operations involve substantial data generation and control mechanisms within smart contracts.

When evaluating the total costs, the gas consumption for the operations carried out throughout the lifecycle of an EVB was 1,439,827 Gwei, while the gas consumption for contract deployment operations was 7,762,282 Gwei. Furthermore, it was found that the minimum gas consumption occurs during changes in the EVB identity status.

In addition to the gas-based cost analysis, the performance characteristics of the Ethereum network were also examined to provide a more realistic assessment of deployment feasibility. Empirical findings by [23] demonstrate that as the number of concurrent users increases, median transaction latencies typically range from 12.5 to 23.9 s in the Preliminary Agreement Phase and 10.9–24.7 s in the Enforcement Phase. Their analysis further shows that when smart-contract logic is more computationally intensive, block volume becomes the dominant factor influencing latency, whereas in lighter-weight transactions gas price has a stronger effect on confirmation times. These observations align with widely reported latency characteristics of Ethereum, where transaction completion may vary from a few seconds to several minutes depending on network congestion, and throughput remains constrained to the low tens of transactions per second.

Given these limitations, especially in scenarios involving high-volume registration or frequent status updates as required by large-scale EV battery lifecycle management, more scalable blockchain platforms were also considered. Layer-2 rollup solutions (such as Optimistic Rollups and zk-Rollups) significantly reduce both transaction latency and cost while preserving Ethereum’s security guarantees. Sidechains like Polygon PoS offer higher throughput with substantially lower operational overhead, whereas permissioned blockchain frameworks such as Hyperledger Fabric provide transaction rates in the thousands of TPS alongside customizable governance and enhanced data-privacy features.

Because the proposed framework follows a modular and platform-agnostic architectural design, it can be deployed on these alternative infrastructures with minimal modification. This flexibility strengthens the framework’s suitability for industrial-scale applications where performance, cost-efficiency, and scalability are critical.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a novel blockchain-based framework for managing the end-of-life phase of electric vehicle batteries, offering a decentralized and transparent solution to one of the key sustainability challenges in the EV ecosystem. The system not only tracks battery lifecycles across multiple stakeholders but also introduces a multi-criteria optimization model to evaluate whether batteries should be routed for reuse or recycling. By automating decision-making and regulatory enforcement through smart contracts, the framework increases accountability and reduces administrative overhead. The integration of web and mobile interfaces ensures stakeholder accessibility, while compliance with the EU battery passport regulation enhances its policy relevance.

Cost analyses confirm the feasibility of deploying the solution on public blockchain platforms such as Ethereum, although scalability challenges and transaction fees suggest a need to explore alternatives like Layer 2 solutions. Future work could expand the framework’s applicability across industries or incorporate dynamic criteria weights based on real-time policy updates or market shifts. Overall, this research offers a technically sound and practically relevant contribution toward a circular battery economy and paves the way for more intelligent and sustainable waste management infrastructures.

As future work, we plan to conduct a formal security audit of the smart contracts using industry-standard analysis tools, along with comprehensive usability testing involving real stakeholders. These steps will further strengthen the reliability, user adoption potential, and real-world applicability of the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, İ.K. and S.Y.; Methodology, S.Y. and İ.K.; Software, S.Y.; Validation, S.Y. and İ.K.; Formal analysis, S.Y.; Investigation, S.Y.; Resources, İ.K.; Data curation, S.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation, İ.K. and S.Y.; Writing—review and editing, İ.K. and S.Y.; Visualization, S.Y.; Supervision, İ.K.; Project administration, İ.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| EVB | Electric Vehicle Battery |

| EAP | Electric Automotive Platform |

| SOH | State of Health |

| EoL | End of Life |

| dApp | Decentralized Application |

| EVM | Ethereum Virtual Machine |

| PoW | Proof of Work |

| PoS | Proof of Stake |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| EU | European Union |

| BC | Blockchain |

| ETH | Ether (Ethereum Cryptocurrency Unit) |

| Gwei | Giga-Wei (Gas Unit in Ethereum) |

| UI | User Interface |

| JSON-RPC | JavaScript Object Notation-Remote Procedure Call |

| EJS | Embedded JavaScript Templates |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision Making |

| SHA-256 | Secure Hash Algorithm-256 bit |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| EU BPR | European Union Battery Passport Regulation |

References

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Subramanian, N.; Ghadge, A.; Belhadi, A.; Venkatesh, M. Blockchain technology’s impact on supply chain integration and sustainable supply chain performance: Evidence from the automotive industry. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 327, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampker, A.; Heimes, H.H.; Offermanns, C.; Frieges, M.H.; Graaf, M.; Soldan Cattani, N.; Späth, B. Cost-benefit analysis of downstream applications for retired electric vehicle batteries. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamerew, Y.A.; Brissaud, D. Modelling reverse supply chain through system dynamics for realizing the transition towards the circular economy: A case study on electric vehicle batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T.; Jæger, B. Circularity for electric and electronic equipment (EEE), the edge and distributed ledger (Edge&DL) model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Wang, M.; Shen, J.; Vijayakumar, P.; Moh, S.; Wu, Q.M.J. Blockchain-Assisted Conditional Anonymous Authentication and Adaptive Tree-Based Group Key Agreement for VANETs. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrala, A.K.; Bagga, P.; Das, A.K.; Kumar, N.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C.; Lorenz, P. On the Design of Conditional Privacy Preserving Batch Verification-Based Authentication Scheme for Internet of Vehicles Deployment. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 5535–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Zhang, L.; You, S.; Van Fan, Y.; Tan, R.R.; Klemeš, J.J.; You, F. Blockchain technology applications in waste management: Overview, challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.R.; Lohmer, J.; Rohla, M.; Angelis, J. Unleashing the circular economy in the electric vehicle battery supply chain: A case study on data sharing and blockchain potential. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 193, 106969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D.; Sangwan, K.S.; Singh, A. Blockchain-enabled architecture for lead acid battery circularity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2023/1542 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1542/oj/eng (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Bonsu, N.O. Towards a circular and low-carbon economy: Insights from the transitioning to electric vehicles and net zero economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.A.; MacCarthy, B.L. Blockchain-enabled supply chain traceability—How wide? How deep? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 263, 108963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ruan, Y.; Guo, L.; Lu, H. BCVehis: A blockchain-based service prototype of vehicle history tracking for used-car trades in China. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 214842–214851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System; bitcoin.org: Online, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, I. Mastering Blockchain; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yaga, D.; Mell, P.; Roby, N.; Scarfone, K. Blockchain technology overview. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.11078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kösesoy, İ. Nesnelerin İnterneti Güvenliğinde Blok Zinciri Uygulamaları. Veri Bilim. 2019, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, Z.; Salama, M.A.; El-Rahman, S.A. Evolution of blockchain consensus algorithms: A review on the latest milestones of blockchain consensus algorithms. Cybersecurity 2023, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buterin, V. A next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform. White Pap. 2014, 3, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, G. Ethereum: A secure decentralised generalised transaction ledger. Ethereum Proj. Yellow Pap. 2014, 151, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zghaibeh, M. A Blockchain-Based, Smart Contract and IoT-Enabled Recycling System. J. Br. Blockchain Assoc. 2023, 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D.; Elgqvist, E.; Santhanagopalan, S. Automotive Lithium-Ion Cell Manufacturing: Regional Cost Structures and Supply Chain Considerations; Technical Report; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2016.

- Javed, F.; Mangues-Bafalluy, J. An Empirical Smart Contracts Latency Analysis on Ethereum Blockchain for Trustworthy Inter-Provider Agreements. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.01397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).