Abstract

Multi-bit upsets (MBUs) are a growing reliability threat in high-density SDRAM, particularly in radiation-prone embedded systems. This paper presents a large-scale FPGA-based fault injection (FI) study targeting external SDRAM in a cache-enabled LEON3 SPARC V8 processor, with over 300,000 dual-bit MBUs injected across three diverse workloads: Fast Fourier transform (FFT), matrix multiplication (MulMatrix), and advanced encryption standard (AES). Our results reveal a profound dependence of MBU manifestation on application semantics: memory-intensive benchmarks (FFT, MulMatrix) exhibit high fault detectability through data store and access exceptions, while the AES workload demonstrates exceptional intrinsic masking, with the vast majority of MBUs producing no observable effect. These results demonstrate that processor vulnerability to MBUs is not uniform but fundamentally shaped by workload characteristics, including memory access patterns, control flow regularity, and algorithmic redundancy. The study provides a hardware-validated foundation for designing workload-aware fault tolerance strategies in space-grade and safety-critical embedded platforms.

1. Introduction

The reliability of modern electronic systems has become a critical concern in both terrestrial and space applications. While technology scaling enables higher integration density, performance, and energy efficiency, it simultaneously reduces the critical charge required to upset a storage node, rendering devices increasingly susceptible to transient faults. At ground level, such faults already pose significant challenges in data centers [1,2] and safety-critical embedded systems [3,4,5,6]. In the harsh radiation environment of space, exposed to cosmic rays, solar particles, and trapped radiation in Earth’s magnetosphere, the likelihood of such events is dramatically amplified. For spaceborne platforms such as satellites, rovers, and avionics, radiation-induced errors represent a direct threat to mission safety and long-term operability.

Radiation-induced effects can be broadly categorized into permanent and transient phenomena [7]. Permanent damage includes total ionizing dose (TID), where cumulative charge buildup in oxide layers degrades device characteristics, and displacement damage, caused by atomic lattice disruptions from energetic particles [8,9]. In contrast, transient effects, commonly known as soft errors, occur instantaneously upon particle strike [10]. Although they cause no physical damage, soft errors alter logical states in memory cells, registers, or flip-flops, potentially leading to software-visible failures if uncorrected.

The most basic soft error is the single-event upset (SEU), affecting a single storage element. However, as semiconductor geometries shrink, the charge deposited by a single energetic particle can perturb multiple adjacent cells simultaneously, leading to multi-bit upsets (MBUs). This phenomenon arises from charge diffusion and the increasing spatial density of memory cells in deep-submicron and FinFET technologies. Experimental studies consistently demonstrate that the MBU fraction grows significantly with each process node: Ibe et al. [11] reported that ~5% of neutron-induced upsets in 180 nm SRAMs are multi-bit, rising to over 45% in 22 nm devices. Similarly, Chabot et al. [12] observed MBU rates increasing from <4% at 180 nm to >44% at 22 nm. This trend confirms that MBUs are not rare anomalies but a systematic consequence of CMOS scaling, elevating them from a secondary concern to a dominant reliability challenge in modern integrated circuits.

MBUs are particularly critical in synchronous dynamic random-access memory (SDRAM), which serves as the primary memory in most embedded and space-grade processors. The dense, regular layout of SDRAM arrays increases the probability that a single particle strike affects multiple cells along a word line or within a burst access. Conventional error correction codes (ECCs), especially single-error-correction and double-error-detection (SEC–DED) schemes, effectively mitigate isolated SEUs but offer limited protection against MBUs that corrupt two or more bits within the same codeword [13,14,15].

Recent research has therefore explored enhanced fault-tolerance mechanisms. Lightweight hard-decoding ECC schemes have been proposed to detect and correct multi-bit errors in control memories with reduced overhead [16]. Hybrid approaches combining hardware ECC with software-implemented hardware fault tolerance (SIHFT) have demonstrated over 98% reduction in silent data corruption (SDC) by mitigating miscorrected MBUs [17]. Other studies propose architecture-level enhancements to mitigate MBU susceptibility while balancing reliability and hardware overhead. These include vulnerability-driven parity schemes, selective interleaving [18,19], double parity with single redundancy (DPSR) [12], and hybrid approaches combining hardened memory cells with ECC [20].

Despite these advances, a key challenge remains: quantifying system-level vulnerability to MBUs under realistic workloads. The behavior of a full computing stack, encompassing the processor, memory hierarchy, and software, cannot be fully characterized by analytical or protection-centric models alone. Empirical evaluation via fault injection (FI) is thus essential to understand how faults propagate across architectural layers and how applications respond to underlying memory corruption.

Fault injection methodologies fall into three categories: hardware-based, software-based, and emulation-based [21]. Hardware approaches (e.g., heavy-ion [22] or proton irradiation [23]) offer high realism but limited controllability and accessibility. Software-based techniques inject faults at the instruction or binary level, enabling flexibility and observability at the cost of timing and microarchitectural fidelity [24,25]. FPGA-based emulation strikes a compelling balance: by mapping a processor onto an FPGA and injecting controlled faults into configuration memory, registers, or external interfaces, researchers can reproduce hardware-level effects at high speed under deterministic, repeatable conditions [26].

For processor reliability assessment, FPGA emulation enables large-scale, workload-driven campaigns with hardware-validated fidelity. Significant effort has focused on soft-core processors, including ARM, RISC-V, and SPARC-based LEON variants. The LEON3, an open-source SPARC V8 processor widely deployed in space missions, has been extensively studied under SEU and single-event transient (SET) conditions, revealing high sensitivity in pipeline stages and control registers [27,28,29]. However, the impact of MBUs in external SDRAM, a critical vulnerability issue in radiation-prone environments, remains underexplored, despite SDRAM’s role as the primary memory in LEON3-based systems. While our experiments use a Xilinx Virtex-5 FPGA, a legacy but well-characterized platform, the conclusions focus on SDRAM-level MBU vulnerability, which is governed by universal radiation physics and workload semantics, not FPGA generation. LEON3 remains in active use in space missions (e.g., ESA’s Proba-3), and the observed vulnerability patterns are expected to generalize to modern platforms where SDRAM continues to serve as the primary memory.

This work addresses this gap by presenting a comprehensive FPGA-based MBU injection campaign targeting SDRAM in a cache-enabled LEON3 processor. We execute three diverse benchmarks, FFT, matrix multiplication, and AES, under over 300,000 dual-bit MBU injections per workload, classifying outcomes into masked faults, silent data corruption, crashes, and stopped-mode events. Our analysis reveals how workload semantics, memory access patterns, and algorithmic structure govern fault manifestation, providing actionable insights for the design of resilient space-grade embedded systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on fault injection, MBUs, and SDRAM reliability in LEON-class processors. Section 3 describes the experimental platform and methodology. Section 4 presents and analyzes results for the three benchmarks. Section 5 discusses implications for system design and mitigation strategies. Section 6 concludes with key findings and future directions.

2. Related Work

The continuous scaling of CMOS technology has heightened the susceptibility of digital circuits to radiation-induced soft errors, with MBUs increasingly supplanting SEUs as the dominant failure mode in dense memory and logic structures. As feature sizes shrink, charge sharing enables a single particle strike to perturb multiple adjacent storage elements, rendering traditional single-bit fault models inadequate for reliability assessment in modern systems. Early radiation experiments by Quinn et al. [30] already signaled this shift, reporting that MBUs accounted for up to 35% of all upsets in Xilinx FPGAs under high-linear energy transfer (LET) ion exposure.

Initial efforts to quantify processor vulnerability relied on simulation-based fault injection to estimate architectural vulnerability factors (AVF) and failure-in-time (FIT) rates [31,32,33,34]. While insightful, these approaches suffered from prohibitive simulation overhead. To address this, Ebrahim et al. [35] pioneered FPGA-based fault injection leveraging on-chip debug infrastructure, enabling accelerated SEU/MBU emulation with hardware-level fidelity. Similarly, Pournaghdali et al. [36] developed a VHDL-level fault injector and demonstrated that multi-bit errors propagate more aggressively than single-bit faults, with outcomes heavily dependent on fault location and workload semantics.

Subsequent work emphasized the critical role of spatial correlation in MBU modeling. Chatzidimitriou et al. [37] showed that ignoring multi-bit effects can underestimate vulnerability by up to 220% in ARM Cortex-A9 cores, underscoring the need for correlated fault models. Chabot et al. [38] further argued for application-aware fault injection, demonstrating that random fault placement yields misleading reliability estimates compared to workload-driven campaigns.

Within the FPGA domain, MBUs pose unique challenges due to the high density of configuration memory, look-up-tables (LUTs), block (BRAMs), and routing resources. Several hardware-assisted frameworks have emerged to address this: Souari et al. [39] injected SEUs/MBUs directly into LUT configuration bits on Xilinx FPGAs, achieving fine-grained control without external instrumentation. Ullah et al. [40] extended this to BRAMs via partial bitstream reconfiguration, enabling safe, localized MBU injection. Tarrillo et al. [41] and Mezzah et al. [42] applied FPGA emulation to complex systems (e.g., RFID, digital controllers), validating its feasibility for accelerated radiation testing. Chen et al. [43] integrated layout-aware back-annotation into a co-designed hardware-software platform, improving MBU realism in VLSI analysis.

More recently, machine learning has been explored to enhance fault injection efficiency. Rajkumar et al. [44,45] proposed long short-term memory (LSTM)-based models to predict failure-inducing bit patterns from spatial dependencies, reducing campaign time without proprietary layout data. Complementarily, Sharma et al. [46,47] developed FPGA-based frameworks targeting processor registers and flip-flops, confirming that MBUs in state elements often persist across multiple cycles and elevate SDC rates.

Parallel advances in hardware-instrumented injection have bridged simulation and emulation. Magliano et al. [48] exploited modern CPU debug units to inject multi-bit faults directly into processor registers and memory during operating system (OS)-level execution. Their results corroborated a key trend: while single-bit faults are frequently masked, MBUs significantly increase both SDC and crash rates, consistent with physical radiation studies [30].

Alternative architectural approaches have also been investigated. Khoshavi et al. [49] evaluated spin-transfer torque (STT-RAM) as a radiation-resilient SRAM replacement in chip multiprocessors, showing that selective data placement can mitigate MBU susceptibility. Abideen et al. [50] introduced EFIC-ME, an FPGA-based platform with precise fault timing and real-time observability, enabling fine-grained failure probability assessment in embedded systems.

Compared to traditional fault injection methodologies, our FPGA-based framework offers a favorable balance of realism, scalability, and control. Unlike software-based simulators [24,25], which lack cycle-accurate modeling of caches, buses, and memory controllers, our approach captures the full hardware execution context of the LEON3 processor. In contrast to physical radiation testing [22,23], which provides high realism but suffers from limited accessibility, high cost, and poor controllability, our method enables deterministic, repeatable, and address-accurate MBU injection at scale. However, it does not replicate the full stochastic nature of ion strikes (e.g., variable linear energy transfers or 3D charge diffusion). Despite this limitation, it provides an excellent platform for workload-driven, hardware-validated reliability analysis under controlled conditions.

Despite these advances, a critical gap persists: the majority of MBU studies focus on on-chip structures, configuration memory, flip-flops, memory caches, or BRAMs, while external SDRAM, despite its prevalence in embedded and space-grade systems, remains comparatively underexplored. SDRAM’s large capacity, dense cell organization, and exposure to radiation make it a high-risk component, yet its interaction with processor pipelines, memory controllers, and software workloads under MBU stress lacks systematic characterization. This work directly addresses this gap by conducting FPGA-based MBU injection campaigns targeting SDRAM in a cache-enabled LEON3 processor, under realistic benchmark execution.

3. Methodology

3.1. Experimental Setup

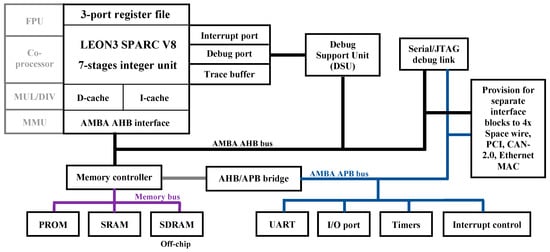

All experiments were conducted on a Xilinx Virtex-5 FXT ML507 development board, hosting a LEON3 SPARC V8 soft-core processor synthesized in the FPGA fabric. The system includes 64 MB of external SDRAM, which serves as the primary target for fault injection. The LEON3 processor interfaces with the SDRAM via the advanced high-performance bus (AHB), part of the advanced microcontroller bus architecture (AMBA) 2.0 on-chip interconnect standard (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

LEON3 soft-core processor architecture with AHB-SDRAM interface.

In this configuration, 8 KB direct-mapped instruction and data caches (I-cache and D-cache) are enabled with a write-through policy to emulate a realistic embedded processing environment. Fault injection is intentionally restricted to external SDRAM, as it represents a well-documented vulnerability surface in space and high-reliability applications, where off-chip memory is directly exposed to ionizing radiation.

Due to the cache hierarchy, injected faults in SDRAM do not immediately affect execution. A corrupted memory word influences the processor only upon a cache miss, when the data are loaded into the data cache. This introduces a temporal and spatial filtering effect: faults may be masked if corrupted data are never accessed, overwritten before use, or evicted from the cache. Conversely, faults in critical data or frequently accessed structures can propagate rapidly to software-level errors. Accurately interpreting fault outcomes therefore requires explicit consideration of cache behavior.

A custom FPGA-based fault injection controller (FIC) was implemented alongside the LEON3 core to enable precise, runtime-controlled MBU injection into SDRAM. In this study, we focus on dual-bit MBUs, defined as the simultaneous inversion of two bits within the same SDRAM word for each injection. This model reflects the most prevalent MBU pattern observed in radiation experiments on commercial SDRAMs [51,52], where ion tracks typically affect 2–3 adjacent cells. Bit positions were exhaustively varied across all possible pairs within each word to capture both contiguous and non-contiguous spatial correlations.

Each fault is injected by toggling the target bits in the SDRAM data path at a clock-cycle boundary synchronized with LEON3 memory transactions. This ensures that the corrupted value is presented to the processor on the next read or write access, closely emulating the timing and visibility of real radiation-induced upsets [53,54].

A Monitor/Checker module concurrently observes processor state, memory exceptions, and program outputs, classifying system responses in real time into four categories:

- −

- masked faults,

- −

- silent data corruptions,

- −

- crashes, and

- −

- stopped-mode events.

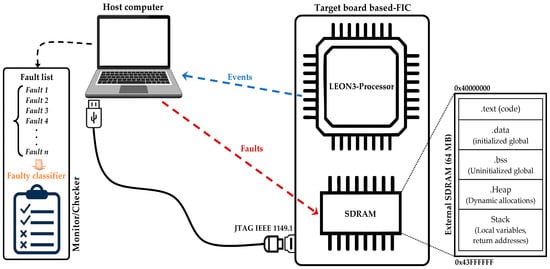

Both the FIC and the Monitor/Checker communicate with a host computer via a JTAG (IEEE 1149.1) interface [55]. The host computer orchestrates the injection campaign, configures fault parameters, and logs results for offline analysis. The overall architecture of this FPGA-based framework is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

High-level overview of the FPGA-based fault injection framework. The host computer controls the LEON3 target via JTAG (IEEE 1149.1) to configure, trigger, and monitor MBU injection campaigns in SDRAM.

3.2. Fault Model and Injection Mechanism

This study focuses on dual-bit MBUs, a representative fault model for modern high-density memory systems under radiation or electromagnetic stress. Each MBU consists of two simultaneous bit flips within the same SDRAM word, reflecting the spatial correlation of charge deposition from a single energetic particle strike [51,52].

While our study focuses on dual-bit MBUs within a single SDRAM word, this model aligns with radiation test data showing that 2–3 adjacent bit flips constitute the most frequent MBU pattern in commercial SDRAM under neutron or proton irradiation [51,52]. Larger or spatially dispersed clusters do occur but with significantly lower probability [11,12]. Thus, dual-bit upsets represent a pragmatic and representative starting point for empirical characterization. Although this work does not directly test 3-bit or 4-bit MBUs, the observed workload-dependent vulnerability trends are expected to hold qualitatively for higher-order MBUs, as error propagation is primarily governed by application semantics (e.g., memory access patterns, data reuse, algorithmic redundancy) rather than cluster size alone.

Fault injection is performed using a two-phase, script-driven framework executed on the host computer:

- 1.

- Memory mapping phase: The benchmark is executed in a dry-run mode to dynamically identify the base address and size of its data segment in SDRAM. This yields a runtime memory map that defines the injection target region.

- 2.

- Injection phase: Using the precomputed map, the FIC iteratively selects each word in the allocated region and flips two bits at configurable offsets (e.g., adjacent or spaced positions). After each injection, the benchmark resumes execution, and the Monitor/Checker records the system response.

This approach ensures deterministic, address-accurate injection while preserving the natural memory access and caching behavior of the application.

3.3. Benchmark Suite

Three representative benchmarks were selected to cover diverse computational and memory access patterns, enabling a comprehensive assessment of workload-dependent vulnerability:

- Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): A memory-intensive signal processing kernel with strided and butterfly access patterns. Its numerical output enables precise detection of silent data error through comparison against a golden reference within a tolerance threshold.

- Matrix Multiplication (MulMatrix): A compute- and memory-bound linear algebra workload operating on two 30 × 30 dense matrices of 32-bit signed integers. It stresses accumulation logic and loop control, making it sensitive to both silent data corruption and catastrophic failures (e.g., illegal memory accesses or arithmetic exceptions).

- AES-128 encryption: A security-critical algorithm with deterministic control flow and structured memory accesses (e.g., substitution-box (S-box) lookups). Due to its strict correctness requirements, even minor corruptions in key or state data produce detectable output deviations, making it ideal for evaluating fault masking versus error exposure in cryptographic contexts. In the AES implementation, the 128-bit state buffer and 256-byte S-box lookup table are allocated in the heap. The state is updated in-place during each round, while S-box accesses follow a fixed, word-aligned pattern. This localized and repetitive memory behavior contributes to the algorithm’s high fault masking, as corrupted values are often overwritten before affecting the final ciphertext.

All benchmarks are implemented in C, cross-compiled for LEON3 using the GNU GCC SPARC toolchain, and natively executed on the FPGA-based processor.

3.4. Experimental Protocol

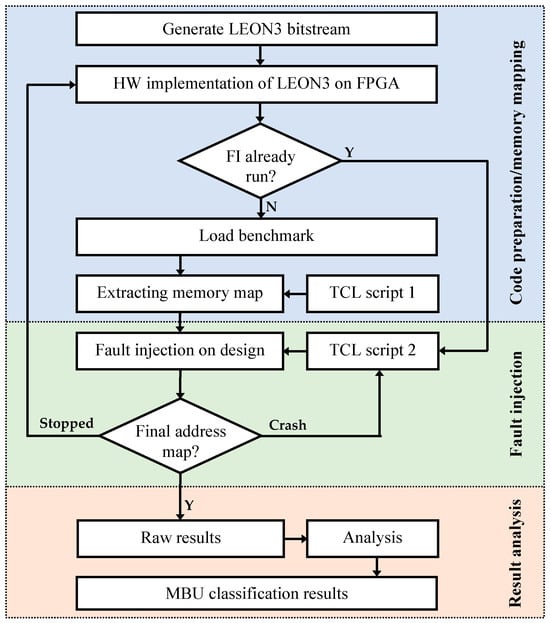

The fault injection campaign follows a controlled, iterative, and recovery-aware protocol to ensure exhaustive coverage and result integrity. As illustrated in Figure 3, the workflow consists of four conceptual phases; code preparation, memory mapping, fault injection, and result analysis, which are implemented through the following concrete steps:

Figure 3.

Workflow of the MBU fault injection campaign.

- The LEON3 system is initialized by loading the synthesized bitstream onto the FPGA.

- To start the fault injection campaign, the benchmark is cross-compiled for the SPARC V8 architecture and loaded onto the LEON3 processor.

- The GRMON debug monitor executes script 1 to run the benchmark in profiling mode and generate a dynamic memory map of the data segment.

- Script 2 drives the injection loop over multiple independent execution runs, referred to as series. Each series to a distinct heap allocation layout in SDRAM, resulting from the dynamic nature of memory allocation in C (e.g., via malloc). For every word in the mapped region of a given series, the FIC applies a dual-bit MBU to SDRAM, and the benchmark resumes execution.

- The Monitor/Checker classifies each outcome into one of four mutually exclusive categories:

- Masked faults: No observable effect on execution or output (e.g., data never read or overwritten before use).

- Silent data corruption: Incorrect output with normal program termination and no exception raised.

- Crash: Abnormal termination due to a hardware exception (e.g., illegal instruction, memory alignment fault, or AHB error).

- Stopped mode: Implicit termination without output (e.g., due to watchdog timeout or unrecoverable stall), without a standard exception.

- Upon a stopped mode, the host computer reloads the FPGA bitstream, and resumes injection from the last untested address within the current series. This ensures continuity and full coverage without re-executing the benchmark. The memory layout (established during script 1) is preserved, so the execution context remains consistent across injections. Upon crash mode, the system reloads an updated script 2 and resumes injection from the next address, preserving the memory layout and ensuring full coverage.

- Results, including fault location, outcome class, and execution context, are logged in raw form to structured text files for statistical analysis.

This protocol guarantees complete coverage of the allocated SDRAM data segment while accounting for cache-induced fault masking and propagation delays.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Classification and Analysis of MBU Effects During FFT Execution

To evaluate the resilience of the LEON3 processor to MBUs, a comprehensive fault injection campaign was conducted on the external SDRAM while executing the FFT benchmark. A total of 311,310 dual-bit MBUs were injected across multiple memory regions, with system responses classified according to the processor’s exception mechanism and observable behavior.

As detailed in Table 1, the vast majority of injected faults triggered precise hardware exceptions, with only 2.95% resulting in masked or silent outcomes. This high detection rate (97.05%) underscores the effectiveness of LEON3′s built-in fault observability mechanisms in a cache-enabled configuration.

Table 1.

MBU fault injection results for the FFT benchmark on LEON3 SDRAM.

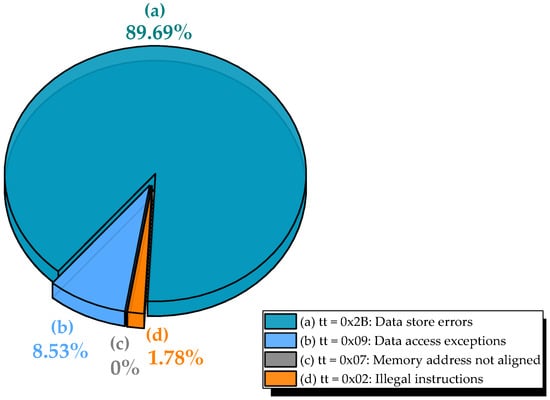

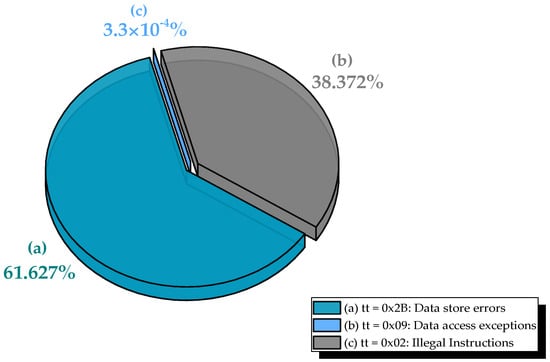

As shown in Figure 4, the dominant fault manifestation is the data store error (trap type tt = 0x2B), accounting for 89.7% of all observed exceptions. In LEON3, this trap is raised when the AHB returns an error response during a store operation, typically due to corrupted address or data values being written to an invalid or protected memory region. Because the data cache employs a write-through policy, every store accesses SDRAM directly. Thus, MBUs affecting store operands or addresses are immediately exposed. A marked increase in data store errors emerged from Series 3 onward, confirming that memory corruption predominantly surfaces during write operations.

Figure 4.

Distribution of observed exceptions during MBU injection in SDRAM for the FFT benchmark: (a) data store errors, (b) data access exceptions, (c) memory address not aligned, and (d) illegal instructions.

The second most frequent category is data access exceptions (tt = 0x09, 8.53%), which occur when a load or store instruction attempts to access an invalid or unmapped memory address. These are precise traps, notably observed in Series 2, allowing the processor to identify the exact faulting instruction. In LEON3, such exceptions are triggered by an AHB error response during a data cache line fill. If only a portion of the line is corrupted, the entire line is marked invalid, but a trap is generated only upon access to the corrupted word.

Less frequent but critical are illegal instruction faults (tt = 0x02, 1.78%), caused when MBUs corrupt instructions in memory, leading to the fetch of undefined or unimplemented opcodes. Although injection targets data memory, such errors can arise if the benchmark’s memory layout places executable code near the injection region (e.g., due to dynamic allocation near the code segment). Given the enabled instruction cache, these faults manifest only after the corrupted instruction is loaded into the I-cache and decoded, highlighting that MBUs can indirectly disrupt control flow even in data-only injection campaigns.

Unaligned memory access exceptions (tt = 0x07) were extremely rare (0.001%), occurring only when MBUs altered address bits such that a memory access violated AHB alignment rules (e.g., a 32-bit access to a non-word-aligned address). While infrequent, these events confirm that MBUs can perturb address generation logic, not just data values.

Critically, masked faults (2.76%) and silent data corruption (0.01%) were negligible, indicating that the combination of LEON3′s exception handling, write-through cache policy, and AHB error signaling provides strong observability for MBUs in SDRAM. From a reliability standpoint, this behavior is highly desirable: most errors are either detected immediately or lead to program termination, minimizing the risk of undetected corruption in safety- or mission-critical applications. A small number of injections led to stopped mode (hang state), typically due to unrecoverable exceptions or watchdog timeouts, triggering FPGA reinitialization and campaign resumption.

These results confirm that, under realistic cache-enabled operation, the LEON3 processor exhibits high sensitivity to MBUs in external memory, with its exception mechanism serving as a robust first line of defense against memory corruption.

4.2. Classification and Analysis of MBU Effects During Matrix Multiplication Execution

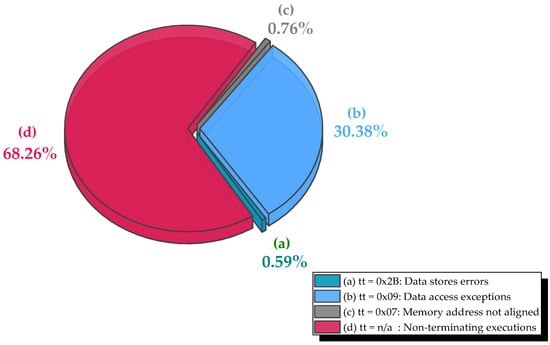

To assess the vulnerability of compute-intensive workloads to memory corruption, a fault injection campaign was conducted on the matrix multiplication (MulMatrix) benchmark running on the LEON3 processor. A total of 303,000 dual-bit MBUs were injected into SDRAM across two independent execution series, with system responses classified by exception type and functional impact, as detailed in Table 2 and Figure 5.

Table 2.

MBU fault injection results for the MulMatrix benchmark on LEON3 SDRAM.

Figure 5.

Distribution of observed exceptions during MBU injection in SDRAM for the MulMatrix benchmark: (a) data store errors, (b) data access exceptions, and (c) illegal instructions.

A striking observation is the significant divergence in fault manifestation between the two series, which stems from differences in the benchmark’s memory layout during execution. In Series 1, the injection window overlapped with the instruction segment, likely due to dynamic allocation near the code region or stack placement, whereas Series 2 targeted a pure data region (e.g., heap-allocated 30 × 30 matrices). This distinction fully explains the contrasting error profiles:

- In Series 1, illegal instruction faults (tt = 0x02) dominated, accounting for 116,264 events (38.37% of total injections). These occur when MBUs corrupt instructions in memory, causing the processor to fetch undefined or unimplemented opcodes. The high incidence confirms that the injection region included executable code or data aliased with the instruction stream.

- In Series 2, no illegal instruction faults were observed, as injections were confined to data-only regions. Instead, data store errors (tt = 0x2B) prevailed, with 186,495 occurrences (61.625% of total injections), reflecting corruption during write-back of computed matrix elements to SDRAM.

Across both series, masked faults were exceedingly rare: only 9 masked events (0.003%) and 1 silent data corruption (0.0003%) were observed. This near-absence of undetected errors underscores the high observability of MBUs in this workload, either through precise traps or program termination.

Other exception types were negligible:

- Data access exceptions (tt = 0x09) occurred only once (in Series 1), consistent with MulMatrix’s regular, contiguous memory access pattern, which rarely generates invalid addresses.

- Memory alignment faults (tt = 0x07) were not observed, as the benchmark exclusively uses aligned data structures.

- Stopped mode occurred once in Series 1, triggering FPGA reinitialization and resumption of the campaign from the last untested address, a robust recovery mechanism that ensured full coverage.

These results demonstrate that the LEON3 processor exhibits strong fault detection capabilities during dense linear algebra workloads, with the dominant error type critically dependent on the targeted memory region. When MBUs affect data, they manifest as data store errors. When they affect code (even indirectly), they trigger illegal instruction traps. Critically, silent data corruption remains virtually absent, confirming that MulMatrix, despite its numerical sensitivity, is effectively monitored by the processor’s exception infrastructure.

4.3. Classification and Analysis of MBU Effects During AES Execution

To evaluate the resilience of security-critical workloads to memory corruption, a fault injection campaign was conducted on the AES-128 encryption benchmark running on the LEON3 processor. A total of 303,161 dual-bit MBUs were injected into SDRAM across five execution series, with system responses classified by functional impact. As quantified in Table 3, the results reveal a strikingly different fault tolerance profile compared to FFT and MulMatrix: the AES workload exhibits exceptionally high masking behavior, with the vast majority of injected faults producing no observable effect on execution or output.

Table 3.

MBU fault injection results for the AES benchmark on LEON3 SDRAM.

The overwhelming majority of masked faults occurred in Series 5, which alone accounted for 280,220 injections (92.43% of the total). These correspond to MBUs that neither triggered a processor exception nor altered the final ciphertext when compared against a golden reference. This high masking rate stems from the algorithmic properties of AES, including its fixed control flow, heap-allocated state and S-box tables, localized lookups, and diffusion characteristics, which often absorb or overwrite corrupted intermediate values before they affect the final result.

In contrast, silent data corruption, where the output is incorrect but no exception occurs, was extremely rare, with only 78 instances (0.026% of total injections) across all series. This low SDC rate is critical for cryptographic integrity: it indicates that when errors do propagate to the output, they are typically detectable through validation mechanisms (e.g., message authentication code (MAC) mismatch or decryption failure), rather than producing undetected corrupted ciphertexts.

Figure 6.

Distribution of observed exceptions during MBU injection in SDRAM for the AES benchmark: (a) data store errors, (b) data access exceptions, (c) memory address not aligned, and (d) non-terminating executions.

- Non-terminating executions (requiring watchdog timeout) occurred in 2770 cases (0.913% of total injections), representing 68.26% of all observed exceptions. These were concentrated in Series 1 and 2, suggesting heightened sensitivity to faults during early key-scheduling phases.

- Data access exceptions (tt = 0x09) totaled 1233 cases (0.406%), arising when MBUs corrupted pointers or indices used in S-box or state array accesses (30.38% of exceptions).

- Data store errors (tt = 0x2B) were minimal (24 cases, 0.007%), consistent with AES’s limited number of store operations relative to its compute-intensive rounds (0.76% of exceptions).

- Unaligned memory accesses (tt = 0x07) occurred in 31 cases (0.010%), likely due to bit flips in address LSBs during table lookups (0.59% of exceptions).

Transitions to stopped mode were observed once per series in the first four runs (4 total, 0.001%), triggering FPGA reinitialization and resumption of the campaign from the last untested address, ensuring full coverage without data loss.

These results demonstrate that the LEON3 processor executing AES is highly robust to MBUs in external memory, primarily due to the inherent error-masking properties of the AES algorithm. From a reliability perspective, the combination of high masking and very low SDC is favorable: most random MBUs are either harmless or lead to detectable failures. However, a systematic evaluation of intentional fault attacks, such as differential fault analysis (DFA) [56,57], remains beyond the scope of this work. This behavior underscores the importance of workload-aware reliability analysis in safety- and security-critical embedded systems.

4.4. Comparative Fault Outcome Summary

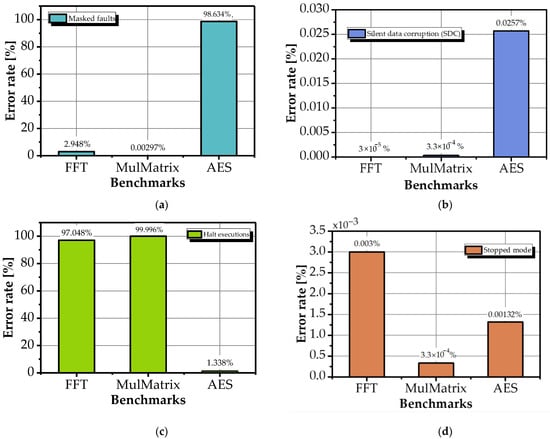

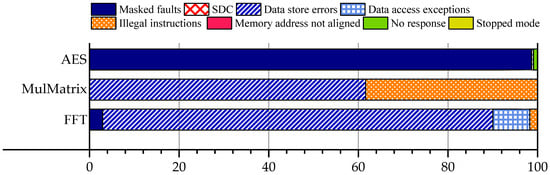

To facilitate direct cross-benchmark comparison, Figure 7 presents the aggregate distribution of key fault outcomes for FFT, MulMatrix, and AES under dual-bit MBU injection in SDRAM.

Figure 7.

Comparative distribution of key fault outcomes across FFT, MulMatrix, and AES benchmarks under dual-bit MBU injection in SDRAM: (a) masked faults, (b) silent data corruption (SDC), (c) halt executions, and (d) stopped mode.

The data show that AES exhibits dominant masking (98.63%), while FFT and MulMatrix show near-total fault exposure, with detectable exceptions (halt executions and stopped mode) accounting for 97.05% and 99.996% of outcomes, respectively. Silent data corruption remains negligible across all benchmarks (<0.03%).

5. Cross-Benchmark Comparison

A comparative analysis of the AES, MulMatrix, and FFT benchmarks reveals how workload characteristics fundamentally influence the manifestation and observability of MBUs in the LEON3 processor. The distinct computational patterns, memory access behaviors, and data flow structures of these benchmarks lead to markedly different fault tolerance profiles, as summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Error rate distribution across MBU fault injection campaigns in SDRAM for FFT, MulMatrix, AES. benchmarks.

In the FFT benchmark, fault manifestations were dominated by data store and data access exceptions, with illegal instruction and alignment faults occurring only sporadically. Critically, masked and silent outcomes were nearly absent, indicating that memory corruptions in this workload are almost always exposed through the processor’s exception mechanism. This high observability aligns with FFT’s memory-intensive nature, characterized by frequent and structured read–write operations that amplify the visibility of even minor memory perturbations.

The MulMatrix benchmark exhibited a bimodal fault profile, reflecting its sensitivity to both data and instruction integrity. Depending on the targeted memory region, MBUs predominantly triggered either data store errors (when affecting data structures) or illegal instruction traps (when overlapping with executable code). In both cases, undetected faults were exceptionally rare, confirming that dense linear algebra workloads provide strong coverage through LEON3′s hardware exception infrastructure.

In stark contrast, the AES benchmark demonstrated exceptionally high fault masking, with the overwhelming majority of injected MBUs producing no observable effect on execution or output. Detectable exceptions, such as non-terminating executions, data access faults, or store errors, were infrequent and limited to specific phases of the algorithm. This resilience stems from AES’s deterministic control flow, localized data accesses, and cryptographic diffusion properties, which collectively limit the propagation of memory corruptions to the architectural level.

Across all benchmarks, stopped mode events occurred only sporadically, consistent with their role as a campaign recovery mechanism rather than a common failure mode. The aggregate comparison reveals a clear trend: workloads with high memory throughput and complex data movement (FFT, MulMatrix) tend to expose MBUs through detectable exceptions, whereas compute-intensive, register-local workloads (AES) exhibit strong intrinsic masking.

While real space-grade systems universally deploy ECC for SDRAM, our unprotected baseline reveals the intrinsic vulnerability of each workload, providing the foundation for workload-aware hardening. Specifically, standard SEC–DED codes can detect (but not correct) double-bit errors that occur within the same codeword, potentially converting otherwise masked faults into detectable uncorrectable error (UE) traps. In workloads like AES, where most MBUs are currently masked due to algorithmic redundancy, ECC could increase fault observability by exposing corruptions that would otherwise remain silent. Conversely, in memory-intensive workloads like FFT or MulMatrix, where exceptions already dominate, ECC may offer limited additional benefit unless augmented with techniques such as bit interleaving or adjacent double-error-correcting codes, which can correct spatially correlated MBUs. This suggests that ECC strategy should be tailored to workload behavior: correction-focused schemes for compute-intensive kernels with high masking potential, and detection-optimized approaches for memory-intensive workloads where faults are already highly observable.

Recent frameworks such as [17] combine SIHFT with ECC to suppress SDC) while [46,47] focus on register-level fault injection. In contrast, our platform enables application-driven injection of MBUs directly into SDRAM, with cycle-accurate visibility into memory transactions. Unlike software-based injectors, our approach captures cache and bus effects; unlike register-focused methods, it targets the dominant off-chip vulnerability surface in embedded systems. This makes our work complementary: it provides the empirical foundation needed to guide the deployment of targeted mitigations, such as [17], in workload-aware reliability designs.

This cross-benchmark analysis underscores a critical principle: processor reliability is inherently workload-dependent. The interaction between application semantics, memory hierarchy, and fault location fundamentally shapes how errors manifest at the system level. Consequently, evaluating resilience based on a single benchmark may yield an incomplete picture of system vulnerability. These findings highlight that memory-intensive operations serve as primary vectors for MBU propagation, while localized or cache-contained computation can inherently suppress fault visibility, an insight essential for guiding the design of selective, application-aware fault tolerance mechanisms in embedded and space-grade systems.

6. Conclusions

This work presents an FPGA-based fault injection framework for studying the impact of radiation-induced multi-bit upsets (MBUs) in the external SDRAM of a LEON3 processor, an aspect of system vulnerability that remains largely unexplored in prior literature. Focusing on dual-bit MBUs, the dominant MBU pattern in SDRAM under radiation, faults were systematically injected during the execution of three representative workloads (FFT, MulMatrix, and AES), providing a detailed characterization of how MBUs propagate through the memory hierarchy and influence software-level execution on a space-grade embedded processor.

A key finding is that fault manifestation is fundamentally shaped by workload semantics. Compute-intensive applications with frequent memory writes (FFT, MulMatrix) exhibit high observability through data store and access exceptions, whereas AES, characterized by stable control flow and limited SDRAM interaction, masks more than 98% of MBUs. These results demonstrate that perceived processor vulnerability is highly benchmark-dependent, and that system-level resilience cannot be accurately assessed using a single workload or fault model. Moreover, the extremely low rate of silent data corruption (<0.03%) across all campaigns confirms that LEON3′s exception mechanisms provide robust detection of SDRAM-level MBUs.

Beyond empirical characterization, this work underscores the growing importance of workload-aware reliability analysis. As technology scaling increases the prevalence of spatially correlated memory upsets, understanding how real applications interact with corrupted SDRAM becomes essential for designing dependable architectures in space and safety-critical domains. The proposed framework enables reproducible, hardware-accurate, and high-throughput fault campaigns without requiring radiation facilities, making it suitable not only for vulnerability assessment but also for guiding memory protection schemes, validating error detection mechanisms, and supporting early-stage reliability engineering.

Future work will extend this framework to additional processor architectures (e.g., RISC-V), explore timing-aware MBU models, and evaluate hybrid mitigation strategies that combine hardware redundancy with algorithmic resilience. To deepen our understanding of architectural versus workload-driven effects, we will conduct cache ablation studies, systematically varying cache size and policy (write-through vs. write-back), to isolate how memory hierarchy configuration influences MBU masking and propagation.

Future work will include controlled ablation studies using static memory mapping, where data structures are placed at fixed addresses to isolate algorithmic vulnerability from linker-induced layout variance. This will complement our current dynamic-allocation approach, which reflects real-world embedded deployment scenarios.

While this study focuses on radiation-induced MBUs in embedded processors, recent works, such as membership inference attacks in transfer learning [58] and smart contract vulnerability detection [59], highlight that subtle, state-dependent behaviors can expose systems to adversarial exploitation. Although these works address software-level security in ML/blockchain, they share a core insight with our work: vulnerability emerges from the interaction between low-level perturbations and high-level system semantics. This motivates future work to extend our MBU framework with state-aware fault activation analysis, enabling the characterization not only of reliability impacts but also of latent security risks (e.g., fault-induced key leakage in AES).

These efforts aim to bridge empirical fault characterization with the development of adaptive, workload-aware reliability mechanisms for radiation-prone and safety-critical embedded systems, enabling selective hardening where it matters most.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and S.S.; methodology, A.K. and S.S.; software, A.K.; validation, A.K., S.S. and H.G.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.S. and H.G.; resources, A.K. and S.S.; data curation, A.K. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, A.K., H.G. and S.S.; visualization, A.K., S.S. and H.G.; supervision, S.S. and H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Sehmi Saad was employed by the company RF2S Spectrum Solutions. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript (alphabetic order):

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| AHB | Advanced High-Performance Bus |

| AMBA | Advanced Microcontroller Bus Architecture |

| ARM | Advanced RISC Machine |

| AVF | Architectural Vulnerability Factors |

| BRAM | Block Random-Access Memory |

| CAN | Controller Area Network |

| CMOS | Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| D-Cache | Data Cache |

| DEC | Double Error Correction |

| DFA | Differential Fault Analysis |

| DPSR | Double Parity Single Redundancy |

| DSU | Debug Support Unit |

| ECC | Error Correction Code |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| FI | Fault Injection |

| FIC | Fault Injection Controller |

| FinFET | Fin Field Effect Transistor |

| FIT | Failure-in-Time |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| FPU | Floating-Point Unit |

| GCC | GNU Compiler Collection |

| HW | Hardware |

| I-Cache | Instruction Cache |

| I/O | Input/Output |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| JTAG | Joint Test Access Group |

| KB | Kilobyte |

| LET | Linear Energy Transfer |

| LSB | Least-Significant Bit |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| LUT | Look-Up-Table |

| MAC | Message Authentication Code |

| MB | Megabyte |

| MBU | Multiple-Bit Upset |

| MMU | Memory Management Unit |

| OS | Operating System |

| PCI | Peripheral Component Interconnect |

| PROBA | Project for On-Board Autonomy |

| PROM | Programmable Read-Only Memory |

| RFID | Radio Frequency Identification |

| RISC | Reduced Instruction Set Computing |

| SDC | Silent Data Corruption |

| SDRAM | Synchronous Dynamic Random-Access Memory |

| SEC | Single Error Correction |

| SET | Single-Event Transient |

| SEU | Single-Event Upset |

| SPARC | Scalable Processor Architecture |

| SRAM | Synchronous Random-Access Memory |

| STT-RAM | Spin-Transfer Torque Random-Access Memory |

| TCL | Tool Command Language |

| TID | Total Ionizing Dose |

| UART | Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter |

| UE | Uncorrectable Error |

| VHDL | VHSIC Hardware Description Language |

| VHSIC | Very High Speed Integrated Circuits |

References

- Papadimitriou, G.; Gizopoulos, D. Silent data corruptions: Microarchitectural perspectives. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2023, 72, 3072–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittel, B.; Shamsa, M.; Inkley, B.; Gur, A.; Lerner, D.; Adams, M. Data center silent data errors: Implications to artificial intelligence workloads & mitigations. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), Grapevine, TX, USA, 14–18 April 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Li, H.; Rahman, F.; Tehranipoor, M.M.; Farahmandi, F. Sofi: Security property-driven vulnerability assessments of ics against fault-injection attacks. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2021, 41, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, S.; Ansari, M.; Khdr, H.; Gohari-Nazari, P.; Yari-Karin, S.; Yeganeh-Khaksar, A.; Hessabi, S.; Ejlali, A.; Henkel, J. A survey of fault-tolerance techniques for embedded systems from the perspective of power, energy, and thermal issues. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 12229–12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.; De Sio, C.; Portaluri, A.; Rizzieri, D.; Vacca, E.; Sterpone, L.; Merodio Codinachs, D. Exploring the impact of soft errors on the reliability of real-time embedded operating systems. Electronics 2022, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangolli, A.; Mahmoud, Q.H.; Azim, A. A systematic review of fault injection attacks on iot systems. Electronics 2023, 11, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhu, M.; Xu, D.; Liu, M.; Dai, X.; Wang, S.; Li, L. Overview on radiation damage effects and protection techniques in microelectronic devices. Sci. Technol. Nucl. Install. 2024, 1, 3616902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, T.R.; McLean, F.B. Total ionizing dose effects in MOS oxides and devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2003, 50, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titze, M.; Belianinov, A.; Tonigan, A.; Su, S.S.; Vizkelethy, G.; Wampler, W.; Hehr, B.; Wang, M.; Zhou, H.; Narayanan, V.; et al. Displacement damage, total ionizing dose, and transient ionization effects in gate-all-around field effect transistors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 5759–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.; Garibotti, R.; Ost, L.C.; Calazans, N.; Moraes, F.G. A Complementary Survey of Radiation-Induced Soft Error Research: Facilities, Particles, Devices and Trends. J. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2024, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibe, E.; Taniguchi, H.; Yahagi, Y.; Shimbo, K.I.; Toba, T. Impact of scaling on neutron-induced soft error in SRAMs from a 250 nm to a 22 nm design rule. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2010, 57, 1527–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabot, A.; Alouani, I.; Niar, S.; Nouacer, R. A new memory reliability technique for multiple bit upsets mitigation. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Conference on Computing Frontiers, Alghero, Italy, 30 April–2 May 2019; pp. 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, H.Y.; Lee, Y.S. Single error correction, double error detection and double adjacent error correction with no mis-correction code. IEICE Electron. Express 2013, 10, 20130743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, A.; Sachdev, M. A new SEC-DED error correction code subclass for adjacent MBU tolerance in embedded memory. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2012, 13, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, A.; Jonkman, M.; Sachdev, M. Adjacent-MBU-tolerant SEC-DED-TAEC-yAED codes for embedded SRAMs. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2014, 62, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepanjali, S.; Sk, N.M. Fault tolerant micro-programmed control unit for SEU and MBU mitigation in space based digital systems. Microelectron. Reliab. 2024, 155, 115360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunig, R.; Borchert, C.; Kober, U.; Schirmeier, H. Hybrid Hardware/Software Detection of Multi-Bit Upsets in Memory. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks Workshops (DSN-W), Brisbane, Australia, 24–27 June 2024; pp. 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatakos, M.; Michael, M.K.; Makris, Y. Vulnerability-based interleaving for multi-bit upset (MBU) protection in modern microprocessors. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Test Conference (ITC), Anaheim, CA, USA, 5–8 November 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatakos, M.; Michael, M.K.; Makris, Y. Multiple-bit upset protection in microprocessor memory arrays using vulnerability-based parity optimization and interleaving. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 2015, 23, 2447–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Tomas, D.; Saiz-Adalid, L.J.; Gracia-Moran, J.; Baraza-Calvo, J.C.; Gil-Vicente, P.J. A Hybrid Technique Based on ECC and Hardened Cells for Tolerating Random Multiple-Bit Upsets in SRAM Arrays. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 70662–70675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziade, H.; Ayoubi, R.A.; Velazco, R. A survey on fault injection techniques. Int. Arab. J. Inf. Technol. 2004, 1, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gunneflo, U.; Karlsson, J.; Torin, J. Evaluation of error detection schemes using fault injection by heavy-ion radiation. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth International Symposium on Fault-Tolerant Computing, Chicago, IL, USA, 21–23 June 1989; pp. 340–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, K.; Zhang, Y.; Itsuji, H.; Uezono, T.; Toba, T.; Hashimoto, M. Analyzing due errors on gpus with neutron irradiation test and fault injection to control flow. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2021, 68, 1668–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Evans, A.; Tahoori, M.B.; Costenaro, E.; Alexandrescu, D.; Chandra, V.; Seyyedi, R. Comprehensive analysis of sequential and combinational soft errors in an embedded processor. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. 2015, 34, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natella, R.; Cotroneo, D.; Madeira, H.S. Assessing dependability with software fault injection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2016, 48, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano, Ó.; García-Herrero, F.; Aranda, L.A.; Sánchez-Macián, A.; Rodriguez, L.; Maestro, J.A. Fault injection emulation for systems in fpgas: Tools, techniques and methodology, a tutorial. Sensors 2021, 21, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasitabar, H.; Zarandi, H.R.; Salamat, R. Susceptibility analysis of LEON3 embedded processor against multiple event transients and upsets. In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering (CSE), Paphos, Cyprus, 5–7 December 2011; pp. 548–553. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnoit, T.; Coelho, A.; Zergainoh, N.E.; Velazco, R. SEU impact in processor’s control-unit: Preliminary results obtained for LEON3 soft-core. In Proceedings of the 18th IEEE Latin American Test Symposium (LATS), Bogota, Columbia, 13–15 March 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kchaou, A.; Saad, S.; Garrab, H.; Machhout, M. Reliability of LEON3 Processor’s Program Counter Against SEU, MBU, and SET Fault Injection. Cryptography 2025, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, H.; Graham, P.; Krone, J.; Caffrey, M.; Rezgui, S. Radiation-induced multi-bit upsets in SRAM-based FPGAs. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2006, 52, 2455–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.S.; Weaver, C.; Emer, J.; Reinhardt, S.K.; Austin, T. A systematic methodology to compute the architectural vulnerability factors for a high-performance microprocessor. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO-36), San Diego, CA, USA, 5 December 2003; pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.S.; Weaver, C.T.; Emer, J.; Reinhardt, S.K.; Austin, T. Measuring architectural vulnerability factors. IEEE Micro 2004, 23, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Li, B.; Peng, L. Versatile prediction and fast estimation of architectural vulnerability factor from processor performance metrics. In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE International Symposium on High Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), Raleigh, NC, USA, 18 February 2009; pp. 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatakos, M.; Michael, M.K.; Makris, Y. Investigating the limits of AVF analysis in the presence of multiple bit errors. In Proceedings of the IEEE 19th International On-Line Testing Symposium (IOLTS), Chania, Greece, 8–10 July 2013; pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Ejlali, A.; Miremadi, S.G. A fast, flexible, and easy-to-develop FPGA-based fault injection technique. Microelectron. Reliab. 2014, 54, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pournaghdali, F.; Rajabzadeh, A.; Ahmadi, M. VHDLSFI: A simulation-based multi-bit fault injection for dependability analysis. In Proceedings of the 3rd International eConference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE), Mashhad, Iran, 31 October–1 November 2013; pp. 354–360. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidimitriou, A.; Papadimitriou, G.; Gavanas, C.; Katsoridas, G.; Gizopoulos, D. Multi-bit upsets vulnerability analysis of modern microprocessors. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Workload Characterization (IISWC), Orlando, FL, USA, 3–5 November 2019; pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Chabot, A.; Alouani, I.; Niar, S.; Nouacer, R. A comprehensive fault injection strategy for embedded systems reliability assessment. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Rapid System Prototyping (RSP), Turin, Italy, 4–5 October 2018; pp. 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Souari, A.; Thibeault, C.; Blaquière, Y.; Velazco, R. An automated fault injection for evaluation of LUTs robustness in SRAM-based FPGAs. In Proceedings of the IEEE East-West Design & Test Symposium (EWDTS), Batumi, Georgia, 26–29 September 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A.; Reviriego, P.; Sánchez-Macián, A.; Maestro, J.A. Multiple cell upset injection in BRAMs for Xilinx FPGAs. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2018, 18, 636–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrillo, J.; Tonfat, J.; Tambara, L.; Kastensmidt, F.L.; Reis, R. Multiple fault injection platform for SRAM-based FPGA based on ground-level radiation experiments. In Proceedings of the 16th Latin-American Test Symposium (LATS), Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 25–27 March 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzah, I.; Kermia, O.; Chemali, H. Extensive fault emulation on RFID tags for fault tolerance and security evaluation. Microelectron. Reliab. 2021, 124, 114263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huo, L.; Xie, Y.; Shen, Z.; Xiang, Z.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Y. Fpga-based cross-hardware mbu emulation platform for layout-level digital vlsi. In Proceedings of the IEEE 32nd Asian Test Symposium (ATS), Beijing, China, 14–17 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar, T.; Öberg, J. On Predictive Modeling of Multi-Bit Upsets for Emulated Fault Injection. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks-Supplemental Volume (DSN-S), Naples, Italy, 23–26 June 2025; pp. 236–238. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar, T.; Öberg, J. Exploring the Potential of LSTM On Emulating Multiple-bit Fault Injection in SRAM-FPGA. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security, Stockholm, Sweden, 9–12 September 2025; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 226–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, J.; Rao, N.; Ait Mohamed, O. Fault Injection Controller Based Framework to Characterize Multiple Bit Upsets for FPGA Designs. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on the Physical and Failure Analysis of Integrated Circuits (IPFA), Singapore, 20–23 July 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, J.; Rao, N. The characterization of errors in an FPGA-based RISC-V processor due to single event transients. Microelectron. J. 2022, 123, 105392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, E.; Savino, A.; Di Carlo, S. Real-time Embedded System Fault Injector Framework for Micro-architectural State Based Reliability Assessment. J. Electron. Test. 2025, 41, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshavi, N.; Samiei, A. The Study of Transient Faults Propagation in Multithread Applications. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.08523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abideen, Z.U.; Rashid, M. EFIC-ME: A fast emulation based fault injection control and monitoring enhancement. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 207705–207716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakos, G.; Huber, P.; Ostermayr, M.; Amirante, E.; Ruckerbauer, F. Investigation of increased multi-bit failure rate due to neutron induced SEU in advanced embedded SRAMs. In Proceedings of the IEEE symposium on VLSI circuits, Kyoto, Japan, 14–16 June 2007; pp. 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, A.; Wood, A. The impact of new technology on soft error rates. In Proceedings of the International Reliability Physics Symposium, Monterey, CA, USA, 10–14 April 2011; pp. 5B.4.1–5B.4.7. [Google Scholar]

- Benevenuti, F.; Kastensmidt, F.L. Comparing exhaustive and random fault injection methods for configuration memory on SRAM-based FPGAs. In Proceedings of the IEEE Latin American Test Symposium (LATS), Santiago, Chile, 11–13 March 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kchaou, A.; Saad, S.; Garrab, H. Emulation-Based Analysis of Multiple Cell Upsets in LEON3 SDRAM: A Workload-Dependent Vulnerability Study. Electronics 2025, 14, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE 1149.1-2013; IEEE Standard for Test Access Port and Boundary-Scan Architecture. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Piret, G.; Quisquater, J.J. A differential fault attack technique against SPN structures, with application to the AES and KHAZAD. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, Cologne, Germany, 8–10 September 2003; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall, M.; Mukhopadhyay, D.; Ali, S. Differential fault analysis of the advanced encryption standard using a single fault. In Proceedings of the 5th IFIP International Workshop on Information Security Theory and Practices, Heraklion Crete, Greece, 1–3 June 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Chen, J.; Fang, Q.; He, K.; Zhao, Z.; Ren, H.; Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, Y. Rethinking Membership Inference Attacks against Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 6441–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Chen, J.; Wu, C.; He, K.; Wu, Y.; Cao, R.; Du, R.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y. VULSEYE: Detect Smart Contract Vulnerabilities via Stateful Directed Graybox Fuzzing. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 2157–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).