Abstract

We propose Heterogeneous Dual-path Contrastive Architecture (HDCA) for action recognition. Our model involves a spatial pathway and a temporal pathway; these two pathways employ distinct backbone networks and input formats, tailored to the specific properties of spatial features and temporal features. The spatial pathway processes super images to capture spatial semantics while the temporal pathway operates on frame sequences to model motion patterns. This targeted design can precisely capture the scenes and motions depicted in videos while improving parameter efficiency. To establish a cross-modality complementary enhancement mechanism, we develop cross-modality contrastive loss and intra-group contrastive loss to train the HDCA. These contrastive losses work synergistically to maximize the similarity of feature representations among videos belonging to the same class while minimizing similarity across different classes, achieving cross-modality alignment through cross-modality contrastive loss and enhancing intra-group compactness via intra-group contrastive loss. HDCA fully exploits the complementary strengths of spatial features and temporal features in action recognition. Systematic experiments on three benchmark datasets validate the effectiveness and superiority of our approach, which support the motivation and hypothesis of our model design. The experimental results demonstrate that our model achieves competitive performance compared to existing state-of-the-art approaches for action recognition. Notably, performance gains increase with dataset complexity, indicating that discriminative correlation information between modalities learned by HDCA yield greater performance gains in the recognition tasks of complex videos.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of mobile Internet technology and the popularization of consumer-grade video capture devices, video has become one of the most widely used multimedia information carriers in various fields of current society. While the exponential growth of video data enriches social life, it also puts forward higher technical requirements for information mining and content understanding of video data. Human action recognition technology for videos has become a research hotspot in the field of computer vision, demonstrating broad application prospects and significant theoretical value in the process of social intelligentization. Deep learning technology, through algorithmic innovation, enhanced computing power, and support from large-scale datasets, has gradually evolved into the mainstream technical approach to solving action recognition tasks, providing key technical support for unlocking the value of video and realizing application implementation. Based on the convolutional neural network of deep learning, this paper establishes an action recognition model to accurately extract the spatial features and temporal features of human actions in videos, and learn the discriminative correlation information between these two types of features, thereby improving the recognition accuracy and robustness of the model.

In video action recognition, researchers widely employ the spatiotemporal feature decoupling strategies [1,2,3,4,5], which decompose the action features of video into spatial appearance features and temporal dynamics features to independently model appearance semantics and motion patterns. This approach is theoretically grounded in the functional separation mechanism between the ventral stream and the dorsal stream in the human visual cortex [6]. The ventral stream extracts position-invariant spatial semantics (e.g., object shape, texture) from static retinal inputs. The dorsal stream encodes temporal dynamics (e.g., velocity fields, motion trajectories) by detecting the accumulation of motion energy between consecutive frames. Spatiotemporal decoupling strategies for action recognition typically extend on classic two-stream architecture [3]; the core principle is to employ independent yet synergistic modules to capture spatial features and temporal features separately, and then integrate the features of these two streams to generate the final classification result. Taking human gait analysis as an example, spatial features determine whether the target belongs to the “human” category, while the speed of motion trajectories discern walking or running. Neuroscientific studies reveal that “place cells” and “time cells” in the hippocampus collaboratively construct spatiotemporal memory maps [7], This biological mechanism explains how humans integrate spatial scenes with temporal sequences into coherent experiences. These findings impose critical requirements for action recognition models: the action recognition architecture should not only include effective spatial and temporal modeling but also establish a cross-modality complementary enhancement mechanism.

Informed by the foregoing principles, we propose a bio-inspired architecture for action recognition. In view of the distinct properties of spatial features and temporal features, this paper designs dedicated pathways to capture the two modalities of video. The proposed model consists of a spatial pathway and a temporal pathway, which are used to extract spatial features and temporal features, respectively. In the spatial pathway, spatial features are primarily contained in the static video frames. We perform uniform sampling of video frames and tile the sampled frames into a 2D grid, generating a super image enriched with spatial information. Given the inherent structural advantage of 2D CNNs in encoding static appearance semantics, we employ them to process super images, thereby precisely capturing scenes and objects depicted in the video. In the temporal pathway, to better capture the motion details in videos, we sample frames with high temporal resolution at low intervals in video clips. Generally, the number of video frames sampled for the temporal pathway is four times that of the spatial pathway, and the two samplings may or may not overlap. Three-dimensional CNNs have demonstrated significant advantages in extracting temporal dynamic features of videos due to their spatiotemporal joint modeling capability. Processing a high temporal resolution frame sequence with 3D CNNs enables precise extraction of rapidly changing motion patterns in videos.

We propose a Heterogeneous Dual-path Contrastive Architecture (HDCA) that extends the classic two-stream CNNs [3]. Although many scholars have conducted extensive extended research on this basis [8,9,10,11,12], they share a critical limitation: these studies usually adopt the same backbone in both pathways. This design not only introduces computational redundancy and efficiency loss but also prevents targeted deep semantic extraction for spatial features and temporal features simultaneously. To address this limitation, we adopt 2D CNNs and 3D CNNs to capture spatial features and temporal features respectively, fully leveraging the inherent structural advantages of CNNs in computer vision [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. In the spatial pathway, each video is represented by a single super image, allowing more videos to be processed per mini-batch and improving computational efficiency. In the temporal pathway, a channel compression strategy is employed due to the high correlation of motion information in the temporal axis. This strategy not only maintains good performance but also achieves model lightweighting. According to our observations, the number of parameters in the temporal pathway is 10% of that in the spatial pathway.

The optimal stage for spatiotemporal fusion and the weighting strategy selection for feature integration remain critical challenges in action recognition, because different modalities of various videos make different contributions to the final classification. Contrastive learning [22] effectively compresses modality-specific noise while preserving category-relevant shared information, demonstrating superior performance in image recognition [23,24] and action recognition [25,26,27]. However, existing methods typically apply contrastive learning within the same modality through different data augmentations. This paper extends this concept to cross-modality interactions for videos, attempting to correlate different video modalities through contrastive learning. This design aligns with ethological principles that spatial and temporal features in video recordings can be algorithmically correlated [28,29].

Our HDCA incorporates cross-modality contrastive loss and intra-group contrastive loss. For cross-modality contrastive loss, spatial features and temporal features from the same video form positive pairs, while any features from different videos form negative pairs. The contrastive loss function [23] is used to maximize similarity between positive pairs and minimize similarity between negative pairs. Meanwhile, features extracted from videos of the same class should share semantic content, leading us to design intra-group contrastive loss. We calculate the average of the same features within the same class videos, treating the averages of different features (spatial/temporal) from same class videos as positive pairs and averages of any features from different classes as negative pairs. Similarly, the contrastive loss function is used to maximize positive pair similarity and minimize negative pair similarity. The proposed HDCA leverages contrastive learning during parameter training to align spatial features and temporal features, and enhances similarity between different modalities within the same class. These features encode discriminative correlation information between modalities, which can achieve superior performance through simple late fusion.

To address the aforementioned challenges and limitations of deep neural networks in action recognition, this study draws inspiration from the collaborative mechanism of the ventral–dorsal dual pathways in the primate visual system [6] and the spatiotemporal memory encoding principle of the hippocampus [7]. We propose HDCA, and its innovations are reflected in the following three dimensions:

- 1.

- The spatial pathway and the temporal pathway in Heterogeneous Dual-path Contrastive Architecture (HDCA) employ distinct backbone networks and input formats tailored to the specific properties of spatial features and temporal features. The spatial pathway processes super images to capture spatial semantics, while the temporal pathway operates on frame sequences to model motion patterns. This targeted design can precisely capture the scenes and motions depicted in videos while improving parameter efficiency.

- 2.

- We devise a cross-modality contrastive loss. Training the HDCA with this loss maximizes the similarity between different feature representations from the same video. This process enables the model to discover discriminative correlation information between modalities while reducing the reliance of performance on spatiotemporal fusion strategies.

- 3.

- To address the potential intra-group feature dispersion caused by cross-modality contrastive loss, we introduce an intra-group contrastive loss. This loss function maximizes the similarity of feature representations among videos belonging to the same class. By enhancing intra-group compactness through intra-group contrastive loss, HDCA effectively leverages the complementary strengths of spatial features and temporal features in action recognition.

2. Related Work

2.1. Two-Stream CNNs

The two-stream 2D CNN framework generally contains two 2D CNN branches taking different input features extracted from the RGB videos for action recognition, and the final result is usually obtained through fusion strategies. Simonyan and Zisserman [3] propose the classic two-stream framework consisting of a spatial network and a temporal network. More specifically, given a video, each individual RGB frame and multi-frame-based optical flows are fed to the spatial stream and temporal stream, respectively. Hence, appearance features and temporal features are learned by these two streams for action recognition. Finally, the classification scores of these two streams are fused to generate the final classification result. Several studies endeavor to extend and improve over these classic two-stream CNNs, and they are reviewed below.

To extract long-term video-level information for action recognition, TSN [4] divides each video into three segments and processes each segment with a two-stream network. The classification scores of the three segments are then fused by an average pooling method to produce the video-level prediction. Feichtenhofer et al. [8] multiplied the appearance residual features with the temporal information at the feature level for gated modulation. Zong et al. [30] extend the two-stream CNN to a three-stream CNN by adding the temporal saliency stream to better capture the salient temporal information. To tackle the high computational cost of computing accurate optical flow, some works [31,32] aimed to mimic optical flow during training, in order to avoid the usage of optical flow during testing. To enhance the action recognition performance, several other works investigate two-stream 3D CNN models. I3D [1] introduce the two-stream Inflated 3D CNN inflating the convolutional and pooling kernels of a 2D CNN with an additional temporal dimension. SlowFast [2] design a two-stream 3D CNN framework containing a slow pathway and a fast pathway that operate on RGB frames at low and high frame rates to capture semantic and temporal, respectively. Li et al. [33] introduce a two-stream spatio-temporal deformable 3D CNN with attention mechanisms to capture the long-range temporal and long-distance spatial dependencies. There have also been some works extending the two-stream CNN architectures in other aspects. Zhang et al. [34] propose two video super-resolution methods producing high-resolution videos, which are fed to the spatial and temporal streams to predict the action class. Feichtenhofer et al. [5] studied several fusion strategies, showing that it is effective to fuse the spatial and temporal networks at the last convolution layer hence reducing the number of parameters while keeping the accuracy. ST-MFO [10] proposes a two-stream CNN based on spatial–temporal multiscale feature optimization. The model performs feature optimization on the multiscale features generated by the pyramid pooling network through a series of operations, which significantly improves the performance of the action recognition task.

Since many actions share similarities, an increasing number of researchers are improving action recognition performance through fine-grained modeling. Wang et al. [35] inferred missing clues through “Hallucination Streams” and focused on action-related spatial regions, effectively capturing fine-grained action dynamics. Liao et al. [36] combined fine-grained feature discrimination with template consistency constraints, which can significantly improve robustness in fine-grained scenarios. This perspective is highly relevant to the task of distinguishing similar actions (e.g., “sword fight” vs. “fencing”) in complex videos. Cho et al. [37] addressed the problem of “loss of hand details” in skeleton action recognition by proposing BHaRNet, which jointly models body movements and fine hand motions through a cross-attention mechanism between the “body expert stream” and “hand expert stream”.

With the development of action recognition technologies and the enhancement of computational capabilities, an increasing number of studies adopt frame sequences as an alternative optical flow to extract temporal features. Given the inherent structural differences between spatial features and temporal features, adapting the network architectures based on the structural characteristics of input data represents a more scientific approach. In this paper, sampled frames are preprocessed first to generate 2D and 3D volumetric inputs. Subsequently, we select backbones according to their inherent strengths in processing specific data modalities. This approach aims to achieve targeted scene representation in videos while optimizing the computational efficiency of model parameters.

2.2. Contrastive Learning

Contrastive learning [22] is widely applied in representation learning, which guides model to learn more discriminative features by constructing positive pairs (similar samples) and negative pairs (dissimilar samples). The core idea of contrastive learning is that similar samples should be brought closer in the representation space, while dissimilar samples should be pushed apart. Commonly used loss functions in contrastive learning include Contrastive Loss [22], Triplet Loss [38], N-pair Loss [39], InfoNCE [40], Logistic Loss. This concept has achieved good performance when applied to the field of computer vision.

In previous research work, contrastive learning has typically been applied in self-supervised learning. In image recognition tasks, SimCLR [23] proposes a simplified contrastive learning framework that emphasizes the importance of data augmentation combinations (e.g., cropping, color distortion) and nonlinear projection heads. By optimizing feature representations through large-batch training, visual representation learning has advanced toward greater efficiency and broader applicability. MoCo [24] introduces a momentum contrast mechanism, which expands negative sample capacity via dynamically updated memory bank to address insufficient negative samples in small-batch training. MoCov2 [41] and v3 [42] further improve data augmentation strategies and network architectures. Following the success of contrastive learning in image recognition, researchers extended this concept to video understanding. VideoMoCo [26] employs temporally adversarial examples and dynamic queue decay mechanisms, effectively enhancing the temporal robustness of video representations and the efficiency of contrastive learning. Qian et al. [27] employ spatial augmentation via random cropping and color distortion, combined with temporal augmentation through random sampling, while introducing dynamic temperature parameter and dynamic encoder to optimize contrastive loss, thereby achieving efficient training of video representation learning. SCVRL [25] innovatively integrates shuffling pretext tasks with Transformer architectures, optimizing feature space distributions through contrastive learning to jointly capture spatial semantics and motion patterns and using contrastive learning to optimize the feature space distribution.

Traditional self-supervised recognition methods based on contrastive learning primarily rely on single-modality data augmentation to construct positive/negative sample pairs. Such methods face limitations in modeling cross-modality correlations due to misalignment in the representation space. When contrastive learning is introduced into supervised learning frameworks for action recognition, it enables the learning of discriminative associations between features, mitigates inter-class confusion, and enhances model generalization capabilities. This study proposes cross-modality contrastive learning and intra-group contrastive learning. Positive sample pairs are formed using different modalities from the same or similar samples, while the negative sample set comprises all modalities from other samples. A contrastive loss function is constructed to train the model, which enables the model to learn discriminative correlation information between modalities.

3. Method

The idea of Heterogeneous Dual-path Contrastive Architecture (HDCA) is generic, allowing flexible selection of backbone for instantiation as required. In this section, we first introduce the design ideas and example instantiations of spatial pathway and temporal pathway, and then introduce the working principles and formula expressions of cross-modality contrastive loss and intra-group contrastive loss.

3.1. Spatial Pathway

Considering that spatial information is primarily embedded in the pixel-level representation of 2D video frames, and 2D convolutional operations can effectively capture texture patterns, shape semantics, and local spatial correlations of video frames in the spatial dimension, the spatial pathway uses a 2D-CNN to extract spatial features from video frames.

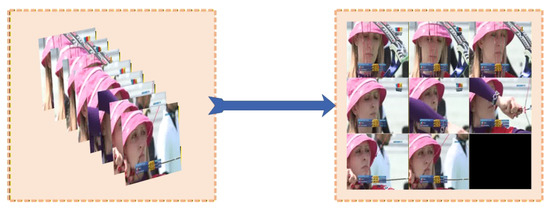

This study employs super images constructed from multiple video frames as the input to the spatial pathway. We uniformly sample M frames, i.e., , from video . To fully leverage the representational capacity of 2D convolutional operations on 2D images, inspired by Fan et al. [43], we tile sampled frames into a 2D grid as illustrated in Figure 1, generating a super image enriched with spatial information. The height and width of the super image are determined by the square root of M and the original dimensions of video frames.

and denote the height and width of the super image, represents the ceiling of the square root of M, and correspond to the height and width of original video frame. If video frames are insufficient to fill the grid, the remaining empty spaces will be filled with padding images. We denote the super image of the i-th video input to the spatial pathway as .

Figure 1.

Construction of super image.

An example instantiation of HDCA is specified in Table 1; the spatial pathway is modified from ResNet-50 [15], denoted by . We replace the original conv1 with conv0 and conv1 in the table. This modification effectively expands the receptive field, enabling subsequent convolutional layers to capture richer spatial information. We sparsely and uniformly sample 8 frames from video as the input to this pathway. Experimental observations reveal that the spatial path achieves a throughput of 1043 fps. Benefiting from the super image design, the HDCA’s spatial path processes video frames 5.96 times more efficiently than that of ResNet-50.The FLOPs for the spatial pathway are 4.23 G.

Table 1.

An example instantiation of the HDCA.

3.2. Temporal Pathway

Different from the spatial pathway, the temporal pathway employs 3D CNN to explicitly capture temporal features (action features) between video frames. During the video frame sampling phase, to obtain finer representation in the temporal axis, we first randomly select video clips with same time span from the input video . Because frames per second (fps) of different videos vary, we adjust the number of frames in each clip according to the ratio between the predefined fps and the real fps, ensuring that each video clip has the same time span. This time-normalized sampling aligns with the temporal frequency response characteristics of primate retinal ganglion cells. Then, following the approach in TSN [4], N frames, i.e., are uniformly sampled from the clip to represent the video . We denote the frame sequence of the i-th video input to the temporal pathway as . N is much larger than M; in general, N is four times M.

The temporal pathway in Table 1 applies 3D ResNet as backbone, modified from ST-ResNet [44]. In the following text, represents the computational process of the temporal pathway. It can be seen that the input size of the spatial pathway is , indicating that the temporal dimension is composed of 32 frames, i.e., , and the height and width of video frames are adjusted to 224. The contents in brackets indicate the dimensions of convolution kernel; non-degenerate temporal convolutions are used in conv1, pool1 and res2 stages, while degenerate temporal convolutions are employed in res3, res4 and res5. The temporal dimension of the feature tensor obtained by res5 is . Reducing the temporal dimension of the feature tensor can alleviate the problem of feature information dilution caused by global pooling operations. Although using degenerate temporal convolutions sacrifices part of the temporal resolution, it expands the receptive field, allowing neurons to cover a broader temporal range and enabling high-level features to capture global temporal semantics.

Given the high correlation of motion information between video frames, the temporal feature matrix along the temporal axis exhibits a strong low-rank property. Our temporal pathway implements a channel compression strategy, setting its channel count to of the spatial pathway. This approach maintains competitive accuracy while achieving model lightweighting and improving parameter efficiency. According to our observations, the FLOPs for the temporal pathway are 0.45 G, containing 2.84 M parameters, which is 10% of the spatial pathway parameters.

3.3. Cross-Modality Contrastive Loss

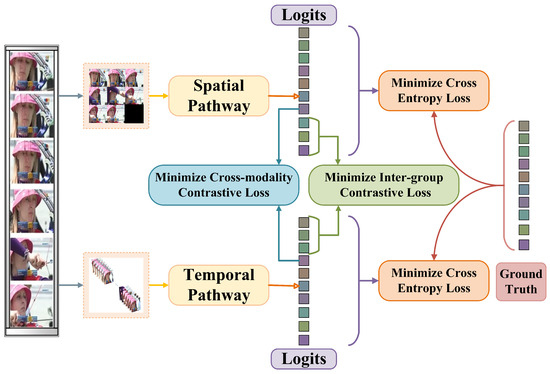

Figure 2 illustrates the schematic diagram of HDCA. During the training phase, we first compute the cross-entropy loss of the two pathways to enhance the fitting capability of the model. We further introduce contrastive loss to enable our model to learn discriminative correlation information between modalities, mitigate the interference of noisy information, and improve the overall performance of action recognition. This subsection introduces the cross-entropy loss and cross-modality contrastive loss, while the next subsection will detail the intra-group contrastive loss.

Figure 2.

Heterogeneous dual-path contrastive architecture (HDCA).

We need to ensure the modeling capabilities of the two pathways for spatial features and temporal features. The sampled data and from video pass through the spatial pathway and the temporal pathway respectively to obtain feature representations and . We minimize the cross-entropy loss to enhance the representation capability of the model.

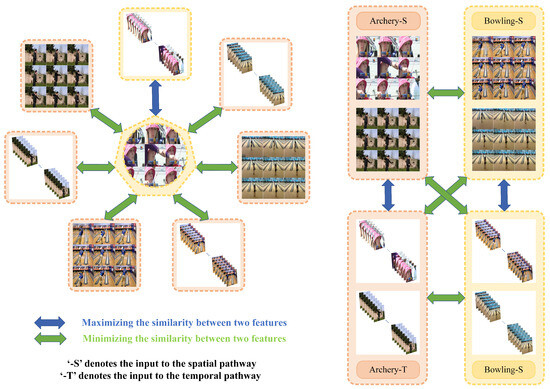

Action recognition involves a multimodality fusion process. Traditional multimodality fusion methods integrate spatiotemporal features through simple concatenation or weighted summation, which often leads to the loss of discriminative correlation information between modalities and degrades the classification accuracy. To address this limitation, we design a cross-modality contrastive loss for training the spatial pathway and temporal pathway, as shown on the left side of Figure 3. This loss function, leveraging the InfoNCE framework [40], enforces alignment between the spatial features and temporal features of the same video in the latent space, simultaneously pushing apart all the modality features of different videos. The exponential form of cosine similarity commonly used in contrastive loss measures the similarity between feature vectors. Let denote the exponential form of cosine similarity between feature vectors A and B, then

is a temperature parameter that controls the shape of the loss function.

Figure 3.

Cross-modality contrastive loss vs intra-group contrastive loss.

During the training phase, the super image and frame sequence are fed into spatial pathway and temporal pathway respectively to obtain spatial features and temporal features of video . For a training mini-batch of size C, the spatial feature and temporal feature of video form a positive pair. We use the exponential of cosine similarity to measure the similarity between the positive pair and .

forms negative pairs with each modality feature from other videos, where the spatial features and temporal features of the remaining videos constitute negative pairs with . The similarity of these negative pairs can be expressed as and . The cross-modality contrastive loss for positive pairs formed by the two modalities of video can be expressed as follows:

represents an indicator function, while both m and n represent the video indices within the mini-batch. The indicator function takes the value of 1 when , and 0 otherwise. The spatial features and temporal features of video form positive pairs with each other, and and denote the cross-modality contrastive losses for the two positive pairs of video . We use the average of the cross-modality contrastive losses for all positive pairs to train the spatial pathway and temporal pathway.

Our aim is to maximize the similarity between different features of the same video.

3.4. Intra-Group Contrastive Loss

The aforementioned cross-modality contrastive loss fails to capture the high-level action semantics within videos of the same class, and even inadvertently push apart the same action samples. We introduce an intra-group contrastive loss, as shown on the right side of Figure 3. It pulls closer the feature representations of videos within the same class and pushes apart the feature representations between different classes, thereby ensuring separability between classes for action recognition. Let denote the ground-truth label of the video . The same features with the same label form a group, and the average of the features within the group is used to represent the group. This approach encourages the model to learn similar representations for videos belonging to the same class.

Let and denote the averages of the spatial features and temporal features classified as q within the mini-batch, while Y is the set of all video classification and q denotes a specific class within this set, i.e., . The indicator function takes the value of 1 when the label of video satisfies , and 0 otherwise. The total number of samples classified as q in the mini-batch is denoted by T.

Based on the Modality-Invariance Theory [45], for video samples of the same class, their spatial features and temporal features should share discriminative semantic information. Therefore, in the intra-group contrastive loss, for videos categorized as q, the spatial features average and the temporal features average form positive pairs with each other. The similarities of these two positive pairs are expressed as and respectively.

and respectively form negative pairs with , where represents the spatial feature or temporal feature, . The similarity between the negative pair and can be expressed as . The intra-group contrastive loss for and can be formulated as follows:

D represents the number of classifications for all videos in a mini-batch. Similar to the cross-modality contrastive loss, we calculate the average of the intra-group contrastive losses for all positive pairs within the mini-batch.

We separately combine the cross-entropy losses and with the cross-modality contrastive loss and the intra-group contrastive loss , yielding the objective losses and for training the two pathways.

where is the weight assigned to the cross-modality contrastive loss, and is the weight assigned to the intra-group contrastive loss.

4. Experiment

In this section, we evaluate our approach on three video recognition benchmark datasets using standard evaluation protocols. We first introduce the evaluation datasets and implementation details of our method. Then, we conduct systematic ablation studies to validate the motivation of the model design and the importance of Heterogeneous Dual-path Contrastive Architecture (HDCA) components. Finally, we compare the performance of our method with state-of-the-art approaches on three benchmark datasets.

4.1. Datasets

We evaluate our approach on three widely used challenging action recognition benchmark datasets: UCF101 [46], HMDB51 [47], and Kinetics-400 [48]. The UCF101 is a commonly used human action recognition dataset, comprising 13,320 video clips across 101 action categories. These categories span diverse scenarios including human–human interaction, human–object interaction, playing musical instruments, daily sports, etc. All videos maintain a consistent frame rate of 25 fps with 320 × 240 pixel resolution. The HMDB51 focuses on human actions and consists of 6766 videos across 51 action classes, collected from realistic videos from various sources, such as movies and web videos. All videos in HMDB51 have a fixed frame rate of 30 fps. The Kinetics-400 is the largest dataset among the three, consisting of 306,245 videos across 400 action categories with each class having at least 400 clips. The average length of the videos is 10 seconds. Most videos in Kinetics-400 are sourced from YouTube and have frame rates ranging from 24 to 30 fps, which aligns with standard video recording practices. Both UCF101 and HMDB51 provide three training/testing splits; we follow the standard evaluation protocol and report the average accuracy across the three splits. Our evaluation metric across all datasets consistently uses Top-1 classification accuracy (%) as the primary performance indicator.

4.2. Implementation Details

Training. Our models are trained from random initialization (“from scratch”), without using ImageNet [49] or any pre-training. We sparsely and uniformly sample eight frames from each video to construct the input for the spatial pathway, apply multi-scale cropping technique [4] for data augmentation, and then resize each frame to . The sampled frames are arranged in a grid to generate super image with pixels. For the temporal pathway, we randomly extract a clip of same duration from each video; a total of 32 frames are uniformly sampled from clip and processed through scale jittering followed by center cropping to pixels. These processed frames are subsequently stacked along the temporal axis to form 3D volumetric inputs for 3D convolutional networks. All models are trained end-to-end using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer with weight decay of 0.0001, momentum of 0.9, and the learning rate initialized as 0.01 that reduces with cosine learning rate scheduler. The and values (refer Equations (12) and (13)) are set to 0.4 and 0.6 unless specified.

Inference. In accordance with practice, this paper uses three-crop testing [2,50,51] for inference. Three-crop testing refers to uniformly sampling 10 clips along video temporal axis, scale the short side of each clips to 256 pixels and randomly take three crops of to cover the spatial dimensions. Three-crop testing is used as the approximation of spatially fully-convolutional testing; we average the softmax scores as the final prediction.

4.3. Ablation Studies

We conduct ablation experiments on the components of HDCA. To validate the generalization ability of HDCA, the first round of ablation experiments is conducted on two benchmarks: HMDB51 and Kinetics-400. Subsequent ablation experiments are performed on HMDB-51 without affecting the comparative analysis.

The impacts of super image, cross-modality contrastive loss and inter-group contrastive loss. We evaluate the impact of the three core strategies, i.e., super image, cross-modality contrastive loss and inter-group contrastive loss, in our HDCA on two challenging benchmarks including HMDB51 and Kinetics-400. Table 2 compares the ablation results of different configurations based on Top-1 accuracy. Replacing super image with single-frame input in the spatial pathway causes performance drops from 78.6% to 74.8% on HMDB51 and 78.3% to 74.0% on kinetics-400. This demonstrates that the use of super image can capture richer spatial information without additional computational cost. Compared with our full model, removing cross-modality contrastive loss leads to accuracy reductions of 0.7% on HMDB51 and 0.9% on Kinetics-400 respectively. The performance of the variant model without inter-group contrastive loss decreases by 1.4% and 2.4% on HMDB51 and Kinetics-400 respectively. The Top-1 accuracy drop is more significant when the inter-group contrastive loss is removed, indicating that inter-group contrastive loss is more effective than cross-modality contrastive loss when only one contrastive loss is used. These findings collectively validate the importance of three strategies in our method.

Table 2.

Ablation results on HMDB51 and Kinetics-400.

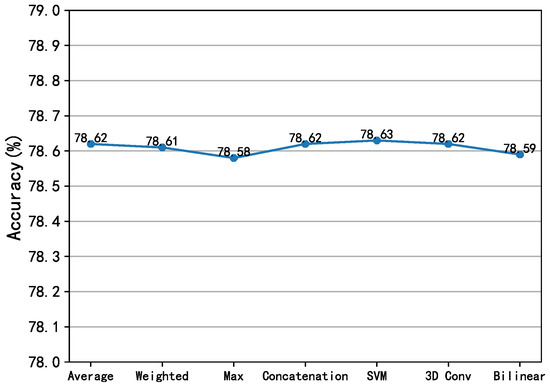

Evaluation of late fusion strategies. The fusion of spatial and temporal pathway features has been extensively studied as a critical component in video action recognition frameworks [4,5,52,53]. This paper systematically evaluates multiple late fusion strategies to aggregate the softmax scores from both modalities: (1) average fusion, (2) weighted fusion, (3) max fusion, (4) concatenation fusion, (5) SVM fusion, (6) 3D Conv fusion, (7) bilinear fusion. The experimental results on the HMDB51 test set are summarized in Figure 4, where it can be observed that all strategies perform comparably. To verify whether there are statistically significant differences in recognition accuracy among different late fusion strategies, paired t-tests were conducted between each pair of fusion strategies based on their recognition accuracy across three splits of the validation set. With a significance level set at 0.05, the results showed that the p-values of all paired t-tests were greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant differences in recognition accuracy among all late fusion strategies. These results validate our core hypothesis: discriminative correlation information between modalities encoded through contrastive learning inherently reduces reliance on fusion mechanisms; simple late fusion suffices to preserve superior performance.

Figure 4.

Experimental results of different fusion strategies.

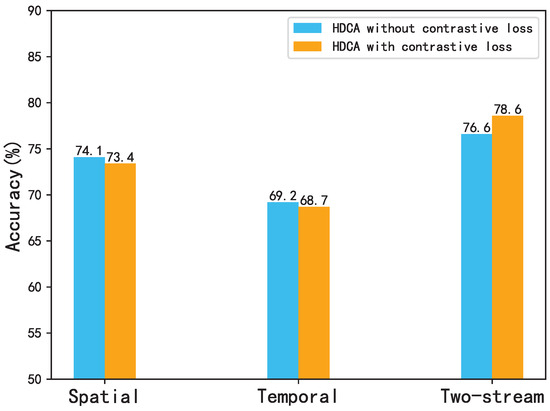

The role of contrastive losses in HDCA. To systematically investigate the functions of the two contrastive losses in our HDCA model, we conduct a phased performance analysis, as visualized in Figure 5, comparing single-modality classification accuracy and two-stream fusion performance before/after implementing contrastive learning. In spatial pathway and temporal pathway, implementing contrastive losses decreases single-modality classification accuracy. The model no longer pursues isolated modality optimization, but actively learns discriminative correlation information between modalities through contrastive constraints. Despite single-modality accuracy reductions, two-stream fusion performance increases 2.0% when contrastive losses are applied on HMDB51. This phenomenon demonstrates the dual role of contrastive losses: aligning features cross-modality and enforcing intra-group compactness. The contrastive losses act as information bottlenecks, compressing modality-specific noise while preserving category-relevant shared information. This aligns with the information bottleneck principle [54], where the mutual information is maximized under classification constraints.

Figure 5.

Comparing single-modality classification accuracy and two-stream fusion performance before/after implementing contrastive learning.

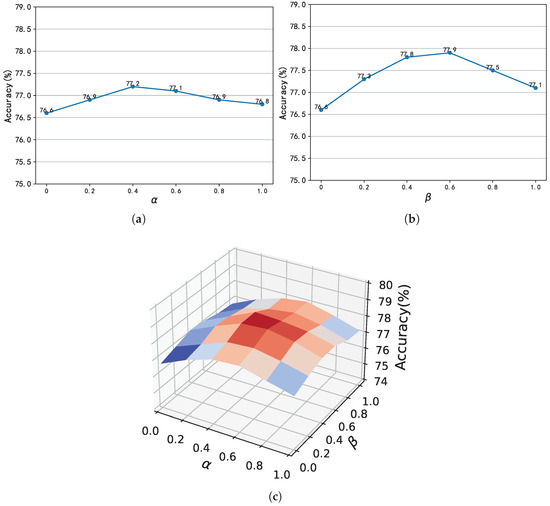

Hyperparameter sensitivity analysis. We investigate the impact of weighting coefficients and in our composite loss functions (refer Equations (12) and (13)) through comparative experiments on HMDB51. To ensure the network model’s ability to fit both spatial and temporal features, the cross-modality contrastive loss weight and the intra-group contrastive loss weight should be smaller than the cross-entropy loss weight. Therefore, the valid range for and is . In the first phase, we evaluate the cross-modality contrastive loss coefficient by maintaining and varying . The results are shown in Figure 6a, whereby optimal performance emerged at , with accuracy decreasing monotonically beyond this value. Subsequently, we examined the intra-group contrastive loss coefficient under analogous conditions (fixing , varying ). Figure 6b demonstrates that yields peak performance, suggesting distinct optimal ranges for each coefficient. Finally, we combined the cross-modality contrastive loss and the intra-group contrastive loss for systematic experiments. As shown in Figure 6c, simultaneously tuning and yields results consistent with single experiments. Based on these findings, we set and as default weighting factors, achieving an optimal balance between cross-modality alignment and inter-group discriminability.

Figure 6.

Effects of hyperparameters. (a) Parameter analysis of . (b) Parameter analysis of . (c) Parameter analysis of and .

Influences of Input Frame Count. To comprehensively analyze the performance of our model across varying numbers of input frames, we conduct additional experiments on HMDB51 by adjusting the frame numbers. As shown in Table 3, three experimental settings are evaluated; the input frames of spatial pathway and temporal pathway were taken as 4 and 16, 8 and 32, 16 and 64 respectively. Correspondingly, in the spatial pathway, the layout of the super image also changes to 2 × 2, 3 × 3, 4 × 4 along with the change in the input frames (empty spaces in the grid are filled with padding images). The experimental results demonstrate that few frames limit the performance of HDCA. Increasing the number of input frames tends to bring rich information and the performance of HDCA will also be better. To balance efficiency and accuracy, we adopt 8 frames for the spatial pathway and 32 frames for the temporal pathway as the default setting.

Table 3.

Comparison results with different numbers of frames are adopted.

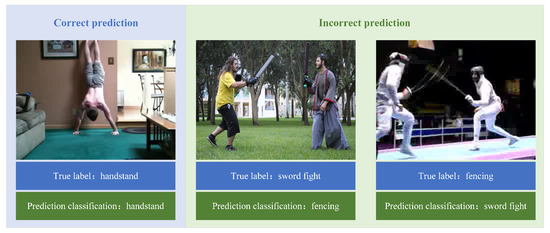

Analyze the model’s performance across different action categories. To investigate the performance differences of HDCA across different action categories, this study statistically analyzed the recognition accuracy of various action categories based on split1 of the HMDB51 dataset. Table 4 and Table 5 list the top five and bottom five action categories in terms of recognition accuracy, respectively. Figure 7 provides visual examples of correct and incorrect predictions. Experimental results indicate that HDCA achieves the best recognition performance on general body movements, particularly repetitive actions, but exhibits suboptimal recognition performance on human–human interaction actions in complex environments. This stems from HDCA’s robust spatio-temporal representation capabilities, enabling it to accurately classify actions that exhibit key discriminative features within short time windows, such as "handstand" shown on the left side of Figure 7. However, the limited receptive field of convolutional neural networks constrains HDCA’s ability to model long-term spatio-temporal dependencies, leading to a decline in recognition performance for similar complex actions. An example is the “sword fight” on the right side of Figure 7, which may be misclassified as “fencing” due to insufficient long-term spatio-temporal contextual information. How to efficiently encode long-term contextual information into video representations and enhance the model’s fine-grained video classification capability is the focus of subsequent research.

Table 4.

Action categories with good recognition performance.

Table 5.

Action categories with suboptimal recognition performance.

Figure 7.

Visual examples of correct and incorrect predictions.

4.4. Comparison with the State of the Art

As shown in Table 6, this study conducts a systematic comparative analysis of the HDCA and state-of-the-art methods on the UCF-101, HMDB-51, and Kinetics-400 datasets. These methods can be divided into three categories: two-stream based methods, RNN-based methods, 3D CNN-based methods. Table 6 also lists the input information required for each method; it can be observed that, except for MSNet [55], all two-stream-based methods require RGB and pre-computed optical flow as inputs, and some RNN-based methods and 3D CNN-based methods also require RGB and optical flow as inputs. Our model is an extension of the two-stream 2D CNN, but the input only requires RGB, thereby omitting the cumbersome process of calculating the optical flow. The temporal pathway processes video frames as input and incorporates a channel compression strategy to learn the temporal features while discarding redundant spatial modeling capabilities. This design makes the temporal pathway able to achieve significantly higher computational efficiency compared to the spatial pathway; the temporal pathway consumes merely ∼10% of the total computation in our experiments. HDCA learns spatial, temporal features, and their complementary relationships directly from raw videos in an end-to-end learning framework. The experimental results show that HDCA achieves competitive performance in all benchmarks, which proves the scientificity and effectiveness of our work.

Table 6.

Comparison with the state of the art on the UCF101, HMDB51, and Kinectis-400 datasets.

As shown in Table 6, the performance of our model only uses RGB as input and does not use extra video datasets for pre-training. HDCA achieves 94.0% on UCF101, which is respectively lower than TSN [4] based on two stream 2D CCN and I3D [1] based on 3D CNN. TSN divided each video into three segments and processed each segment with a two-stream network to extract long-term video-level information. I3D proposed 3D CNN models with two-stream design and conducted pre-training on Kinetics-400. These operations of TSN and I3D significantly increase computational demands, which is the reason for its better performance. HDCA achieves an accuracy of 78.6% on HMDB51, which is lower than I3D; the reason is the same as we analyzed above. Our method outperforms all other methods on the kinetic-400 dataset, with an accuracy of 78.3%. The experimental results demonstrate that the more complex the video content of the dataset, the better our method performs. This indicates that the discriminative correlation information between modalities learned by HDCA yields greater performance gains for the recognition task of complex videos.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes an Heterogeneous Dual-path Contrastive Architecture (HDCA). Firstly, according to the inherent properties of spatial features and temporal features in video data, we construct different feature extraction pathways respectively. Then, we design cross-modality contrastive loss and intra-group contrastive loss to learn discriminative correlation information between modalities. The heterogeneous dual-path design effectively improves parameter efficiency and recognition accuracy. Achieving cross-modality alignment through cross-modality contrastive loss and enhancing intra-group compactness via intra-group contrastive loss, HDCA fully exploits the complementary strengths of spatial features and temporal features in action recognition. Systematic experiments on multiple benchmark datasets validate the effectiveness and superiority of our method, supporting the motivation and hypothesis of our model design. The discriminative correlation information between modalities is the key to breaking through the bottleneck of action recognition. In future work, we aim to further explore more adaptable and efficient learning strategies that can effectively capture discriminative correlation information between modalities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and L.M.; methodology, S.K. and H.H.; software, S.K.; validation, S.K., J.W. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, J.W.; resources, A.M.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K., L.M. and J.W.; visualization, L.M. and J.W. supervision, H.H.; project administration, H.H.; funding acquisition, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 61672210, the Major Science and Technology Program of Henan Province under Grant No. 221100210500, and the Central Government Guiding Local Science and Technology Development Fund Program of Henan Province under Grant No. Z20221343032.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We clarify that our research findings are based on the analysis of publicly available datasets: UCF101: https://www.crcv.ucf.edu/research/data-sets/ucf101/ (accessed on 6 September 2025). HMDB51: https://serre-lab.clps.brown.edu/resource/hmdb-a-large-human-motion-database/ (accessed on 6 September 2025). Kinetics-400: https://deepmind.com/research/open-source/kinetics (accessed on 11 September 2025).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Henan Provincial Medical Big Data and Computational Intelligence Engineering Technology Research Center for providing the experimental equipment and research facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carreira, J.; Zisserman, A. Quo vadis, action recognition? A new model and the kinetics dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6299–6308. [Google Scholar]

- Feichtenhofer, C.; Fan, H.; Malik, J.; He, K. Slowfast networks for video recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October 27–2 November 2019; pp. 6202–6211. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Two-stream convolutional networks for action recognition in videos. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 568–576. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, D.; Tang, X.; Van Gool, L. Temporal segment networks for action recognition in videos. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 41, 2740–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtenhofer, C.; Pinz, A.; Zisserman, A. Convolutional two-stream network fusion for video action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 1933–1941. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.; Han, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z. A dual-stream neural network explains the functional segregation of dorsal and ventral visual pathways in human brains. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 50408–50428. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Cheng, N.; Chen, X.; Wang, C. Integration and competition between space and time in the hippocampus. Neuron 2024, 112, 3651–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtenhofer, C.; Pinz, A.; Wildes, R.P. Spatiotemporal multiplier networks for video action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Wanyan, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, C.; Xu, C. Active exploration of multimodal complementarity for few-shot action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 6492–6502. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.; Fu, W. Spatial-temporal multiscale feature optimization based two-stream convolutional neural network for action recognition. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 11611–11626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Rai, N.; Sikka, K.; Sharma, G. Adascan: Adaptive scan pooling in deep convolutional neural networks for human action recognition in videos. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3376–3385. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Xing, H.; Qu, R.; Li, H.; Cheng, X.; Xu, L.; Feng, L.; Wan, Q. Heterogeneous Mutual Knowledge Distillation for Wearable Human Activity Recognition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 16589–16603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganj, A.; Ebadpour, M.; Darvish, M.; Bahador, H. LR-net: A block-based convolutional neural network for low-resolution image classification. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 2023, 47, 1561–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; Volume 31, pp. 4278–4284. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Xu, W.; Yang, M.; Yu, K. 3D convolutional neural networks for human action recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 35, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feichtenhofer, C. X3d: Expanding architectures for efficient video recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, K.; Kataoka, H.; Satoh, Y. Can spatiotemporal 3d cnns retrace the history of 2d cnns and imagenet? In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 6546–6555. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D.; Wang, H.; Torresani, L.; Feiszli, M. Video classification with channel-separated convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 5552–5561. [Google Scholar]

- Hadsell, R.; Chopra, S.; LeCun, Y. Dimensionality reduction by learning an invariant mapping. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’06), New York, NY, USA, 17–22 June 2006; Volume 2, pp. 1735–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PmLR, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 9729–9738. [Google Scholar]

- Dorkenwald, M.; Xiao, F.; Brattoli, B.; Tighe, J.; Modolo, D. Scvrl: Shuffled contrastive video representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 4132–4141. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, T.; Song, Y.; Yang, T.; Jiang, W.; Liu, W. Videomoco: Contrastive video representation learning with temporally adversarial examples. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 11205–11214. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, R.; Meng, T.; Gong, B.; Yang, M.H.; Wang, H.; Belongie, S.; Cui, Y. Spatiotemporal contrastive video representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 6964–6974. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, B.; Zha, K.; Cao, H.; Tang, J.; Yu, M.; Lu, C. Complex sequential understanding through the awareness of spatial and temporal concepts. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Han, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, R.; Han, M.H.; Liu, Q.; Wei, P. Anti-drift pose tracker (ADPT), a transformer-based network for robust animal pose estimation cross-species. eLife 2025, 13, RP95709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, M.; Wang, R.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Gong, Y. Motion saliency based multi-stream multiplier ResNets for action recognition. Image Vis. Comput. 2021, 107, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, H. Real-time action recognition with enhanced motion vector CNNs. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2718–2726. [Google Scholar]

- Piergiovanni, A.; Ryoo, M.S. Representation flow for action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9945–9953. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D. Spatio-temporal deformable 3d convnets with attention for action recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 98, 107037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, D.; Xiong, Z. Two-stream action recognition-oriented video super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October 27–2 November 2019; pp. 8799–8808. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Koniusz, P. Feature Hallucination for Self-supervised Action Recognition. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.20342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Shu, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yuan, D.; Chang, X.; He, Z. Fine-grained feature and template reconstruction for tir object tracking. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 9276–9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kim, T.K. Body-Hand Modality Expertized Networks with Cross-attention for Fine-grained Skeleton Action Recognition. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.14960. [Google Scholar]

- Schroff, F.; Kalenichenko, D.; Philbin, J. Facenet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 815–823. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, K. Improved deep metric learning with multi-class n-pair loss objective. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Oord, A.v.d.; Li, Y.; Vinyals, O. Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.03748. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Fan, H.; Girshick, R.; He, K. Improved baselines with momentum contrastive learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.04297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xie, S.; He, K. An empirical study of training self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 9640–9649. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Q.; Chen, C.F.; Panda, R. Can an image classifier suffice for action recognition? arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.14104. [Google Scholar]

- Christoph, R.; Pinz, F.A. Spatiotemporal residual networks for video action recognition. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 2, 3468–3476. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Z.; Wang, C.; Pan, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Guo, M. MIMR: Modality-invariance modeling and refinement for unsupervised visible-infrared person re-identification. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 285, 111350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, K.; Zamir, A.R.; Shah, M. A dataset of 101 human action classes from videos in the wild. Cent. Res. Comput. Vis. 2012, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehne, H.; Jhuang, H.; Garrote, E.; Poggio, T.; Serre, T. HMDB: A large video database for human motion recognition. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 2556–2563. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, W.; Carreira, J.; Simonyan, K.; Zhang, B.; Hillier, C.; Vijayanarasimhan, S.; Viola, F.; Green, T.; Back, T.; Natsev, P.; et al. The kinetics human action video dataset. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.06950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Xu, Y.; Shi, J.; Dai, B.; Zhou, B. Temporal pyramid network for action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 591–600. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-local neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Ma, Y.; Yang, W.; Ji, W.; Wang, R.; Jiang, P. Spatial-temporal interaction learning based two-stream network for action recognition. Inf. Sci. 2022, 606, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lan, Z.; Newsam, S.; Hauptmann, A. Hidden two-stream convolutional networks for action recognition. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ACCV 2018: 14th Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Perth, Australia, 2–6 December 2018; Revised Selected Papers, Part III 14. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Tishby, N.; Pereira, F.C.; Bialek, W. The information bottleneck method. arXiv 2000, arXiv:physics/0004057. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.; Kim, M.; Kwak, S.; Cho, M. Motionsqueeze: Neural motion feature learning for video understanding. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XVI 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 345–362. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Qiao, Y.; Tang, X. Action recognition with trajectory-pooled deep-convolutional descriptors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 4305–4314. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Yu, W.; Pang, Y.; Wang, H. Few-shot action recognition via multi-view representation learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 8522–8535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Qing, Z.; Zuo, Z.; Gao, C.; Jin, R.; Sang, N. HyRSM++: Hybrid relation guided temporal set matching for few-shot action recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 147, 110110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, J.; Anne Hendricks, L.; Guadarrama, S.; Rohrbach, M.; Venugopalan, S.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Long-term recurrent convolutional networks for visual recognition and description. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 2625–2634. [Google Scholar]

- Majd, M.; Safabakhsh, R. Correlational convolutional LSTM for human action recognition. Neurocomputing 2020, 396, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, R.; Zong, M.; Ji, W. Spatiotemporal saliency-based multi-stream networks with attention-aware LSTM for action recognition. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 14593–14602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diba, A.; Fayyaz, M.; Sharma, V.; Karami, A.H.; Arzani, M.M.; Yousefzadeh, R.; Van Gool, L. Temporal 3d convnets: New architecture and transfer learning for video classification. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.08200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasgani, S.H.; Chen, Y.; Shkurti, F. Slic: Self-supervised learning with iterative clustering for human action videos. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 16091–16101. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q.; Zhang, H.B.; Li, Z.; Du, J.X.; Lei, Q.; Liu, J.H. Shuffle-invariant network for action recognition in videos. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. (TOMM) 2022, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Wu, S.; Jin, X.; Shan, S. Hierarchical compositional representations for few-shot action recognition. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2024, 240, 103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yan, Y.; Hu, H.M.; Li, B.; Wang, H. Cross-modal contrastive learning network for few-shot action recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).