A Pipelined FPGA-Based Frame Synchronizer for Gaussian Noise Channels

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Improved Throughput: In our Frame Synchronizer, improvements are presented to address the performance issues of latency, clock and data throughput, FEC opportunity loss, and implementation complexity. The approach uses deep pipelining and parallelism and removes state machine structures that are typical in the traditional Frame Synchronizers, thus increasing processing throughput.

- Improved Clock/Data Performance: A direct linear pipeline and parallelism allows the clock rate to increase proportionally to the depth of the pipeline structures. Further, operating several pipelined structures in parallel allows higher levels of complex operations without the latency in typical synchronizer state machine designs.

- Reduced Latency: A further benefit of a pure forward path pipelined structure is that there are no feedback paths to create “bubbles” in processing. Bubbles in this context are similar to processor instruction execution pipelines, where a process direction change, such as a branch instruction, causes a feedback or feedforward change of direction. Any partially processed pipeline stage function is thrown away, reducing the overall pipeline efficiency. In traditional FS, when a flywheel state machine synchronizer changes state from flywheel to search, a feedback path stops FEC code processing and returns to the starting “search” and “verify” states. During these states, FEC processing is suspended while frame synchronization lock is re-established. In our synchronizer, there is no state machine and thus there are no feedback paths, eliminating the FEC opportunity loss typical in flywheel FS state machines.

- Reduced Implementation Complexity: By implementing our Frame Synchronizer in a pure linear pipeline, with no feedback loops, and utilizing parallelism in combination, a symmetrical structure can be used in an FPGA, without requiring the complexity of a state machine. Parallelism and pipelining are good fits for FPGAs as they are fundamentally parallel processing devices. Although the resource utilization may increase, the implementation is still simpler as no state machine analysis is required. Once the pipeline starts and is operational, a Frame Sync decision (pulse) appears at the pipeline output every clock cycle without complex decision making typical of state machines.

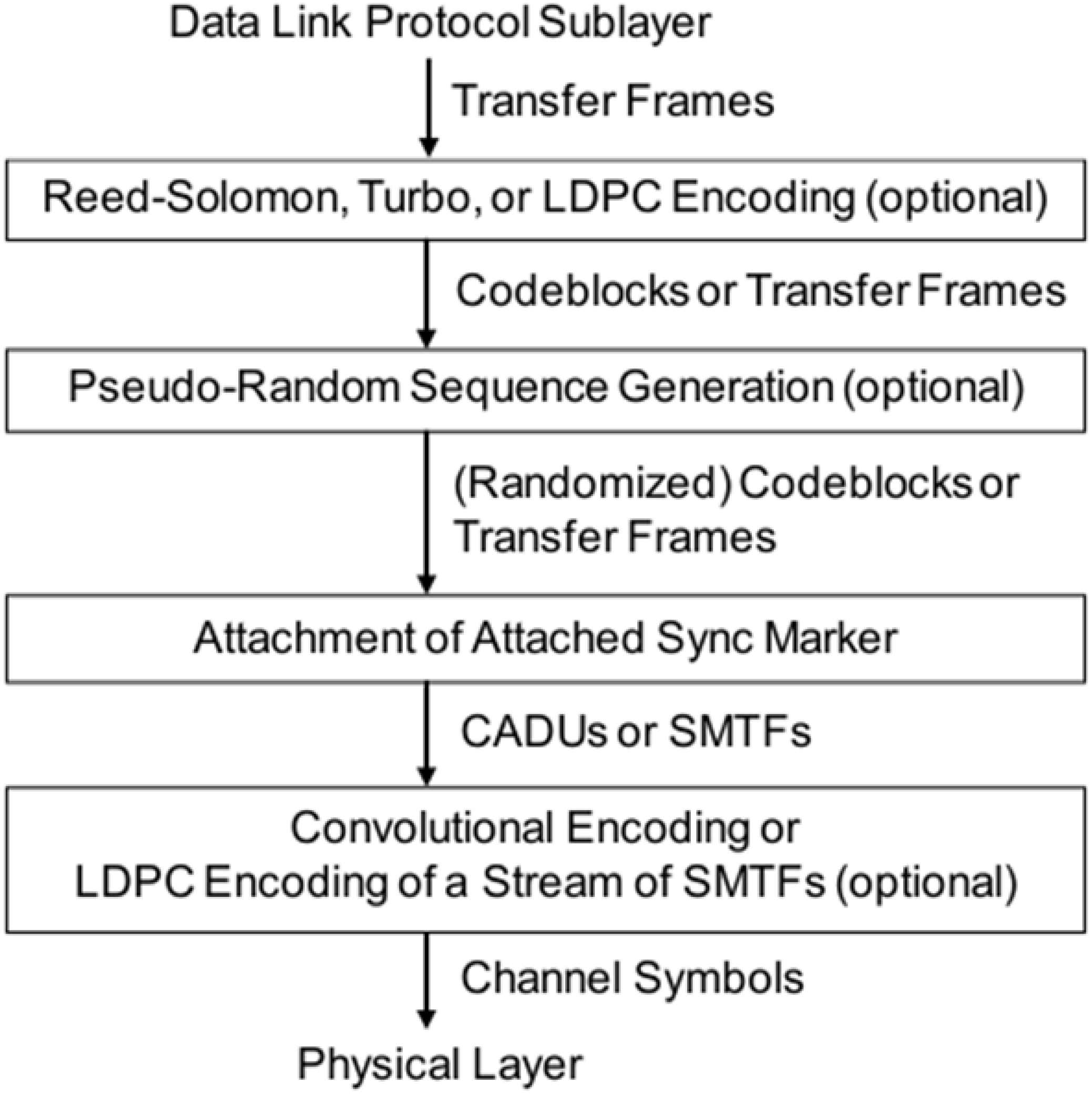

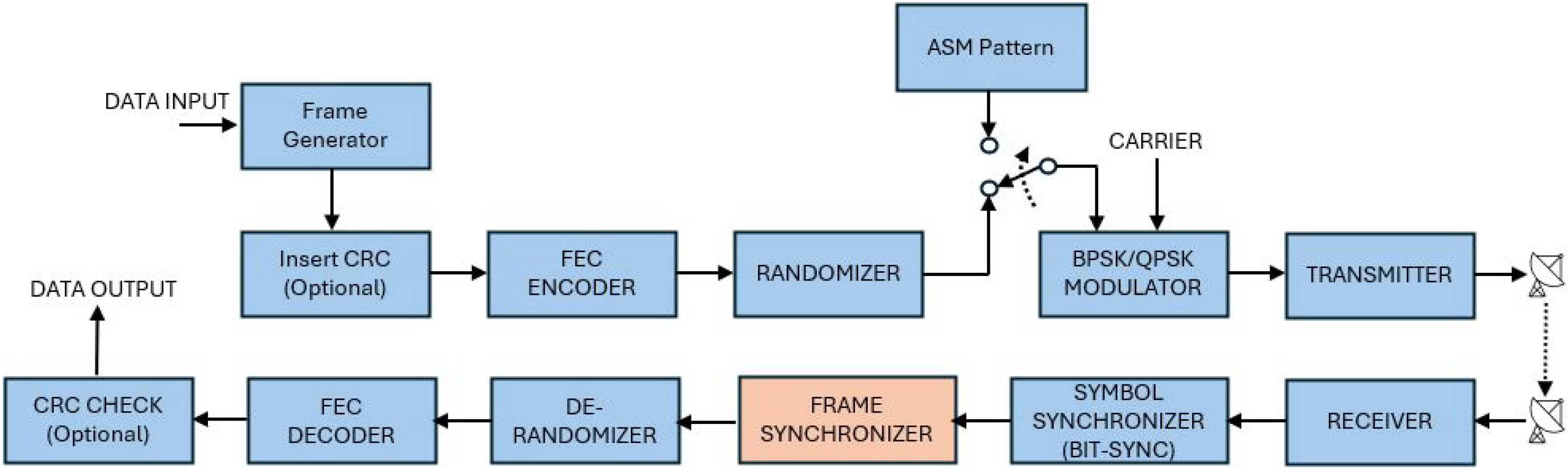

2. Background

2.1. Frame Synchronizers and Bit Error Rate

2.2. Bit Transition Density and Clock Recovery

2.3. Randomization

2.4. Existing Frame Synchronizers

3. An Alternative Frame Synchronizer

3.1. Random Data Around the ASM Marker

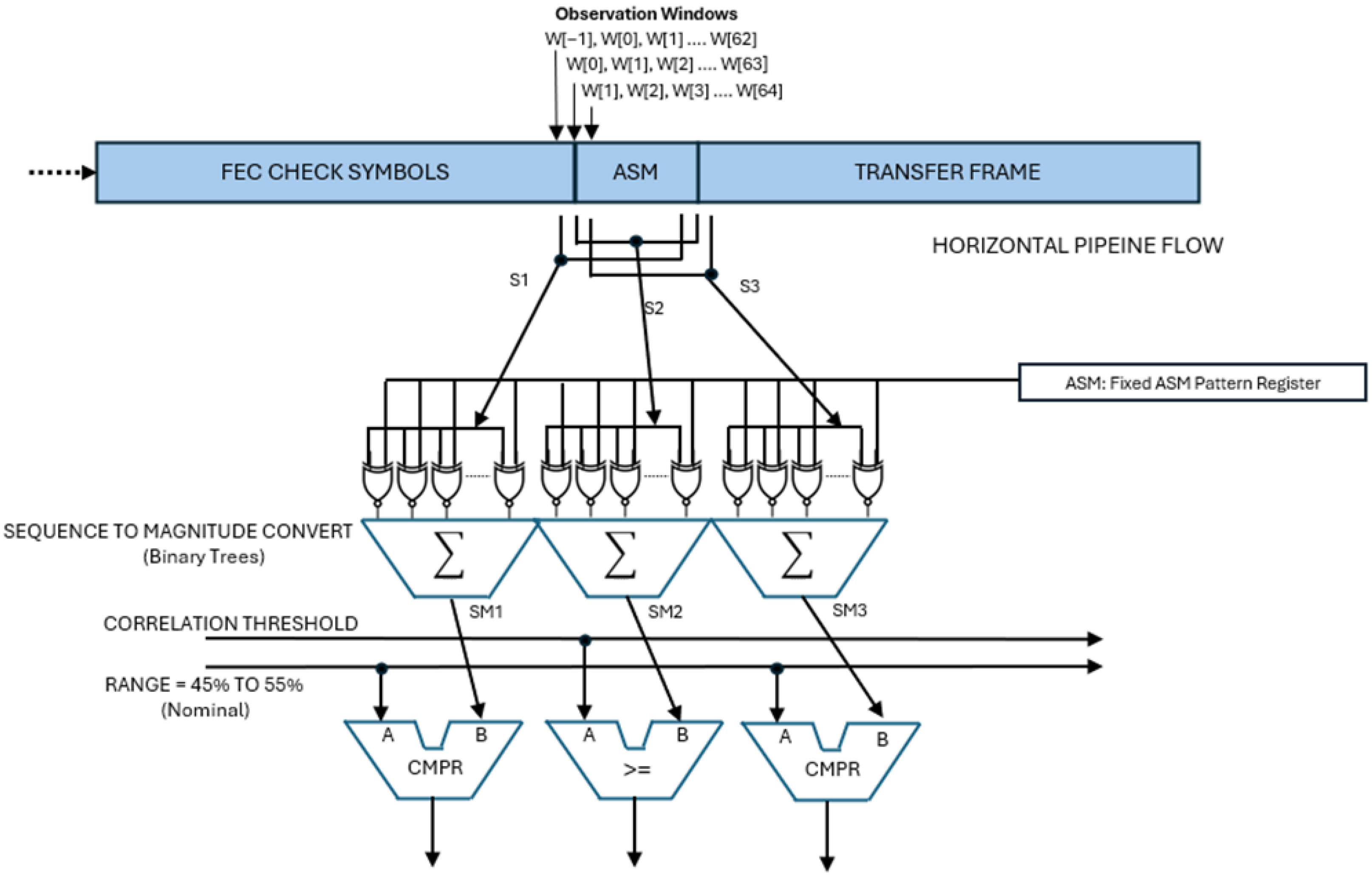

3.2. Parallel Three-Part Observation Windows

4. Implementation in an FPGA

4.1. Horizontal and Vertical Pipelines

4.2. Sequence-to-Magnitude Conversion

4.3. Extending the Effective ASM Length

4.4. Alternative Observation Windows

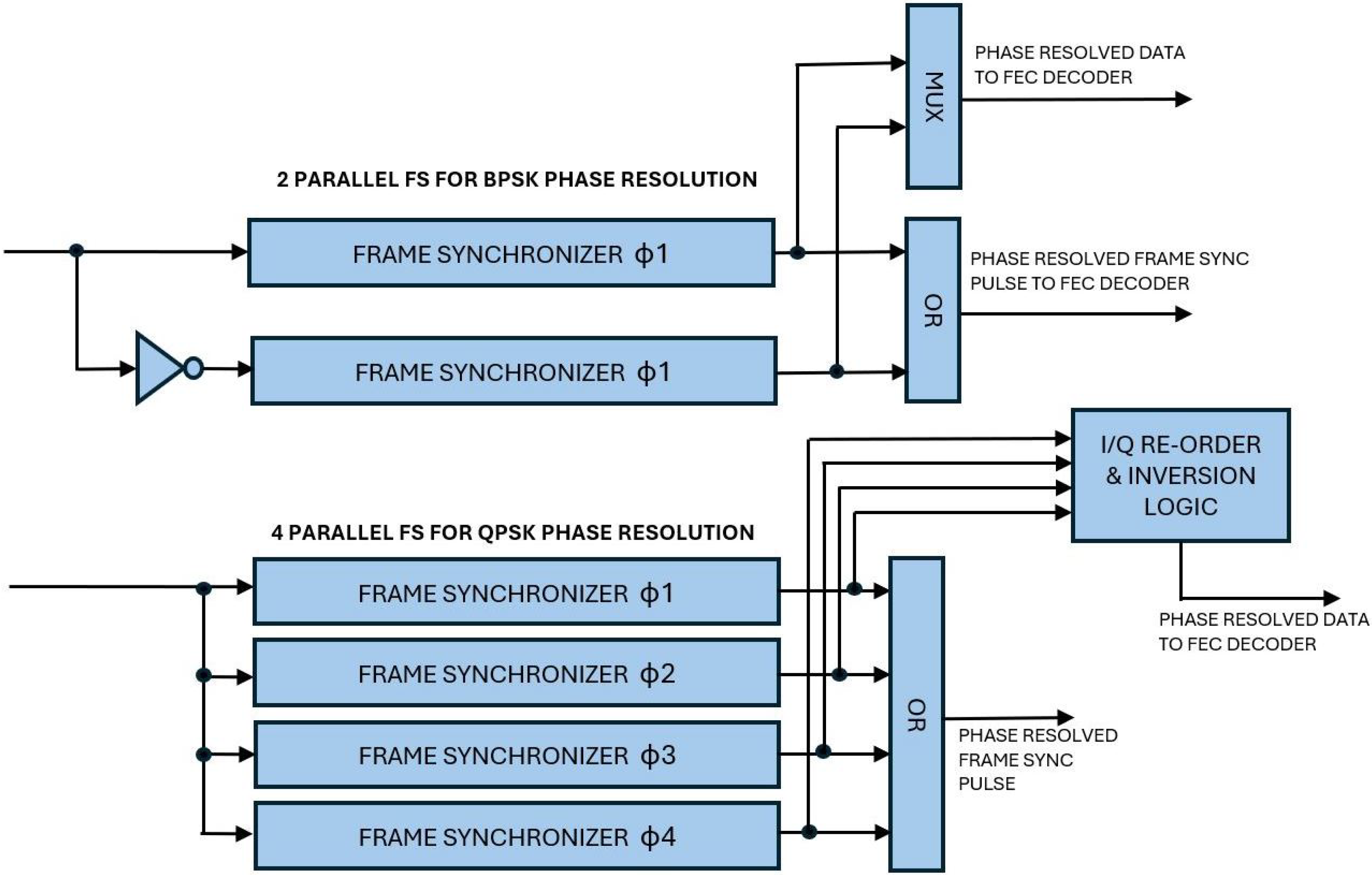

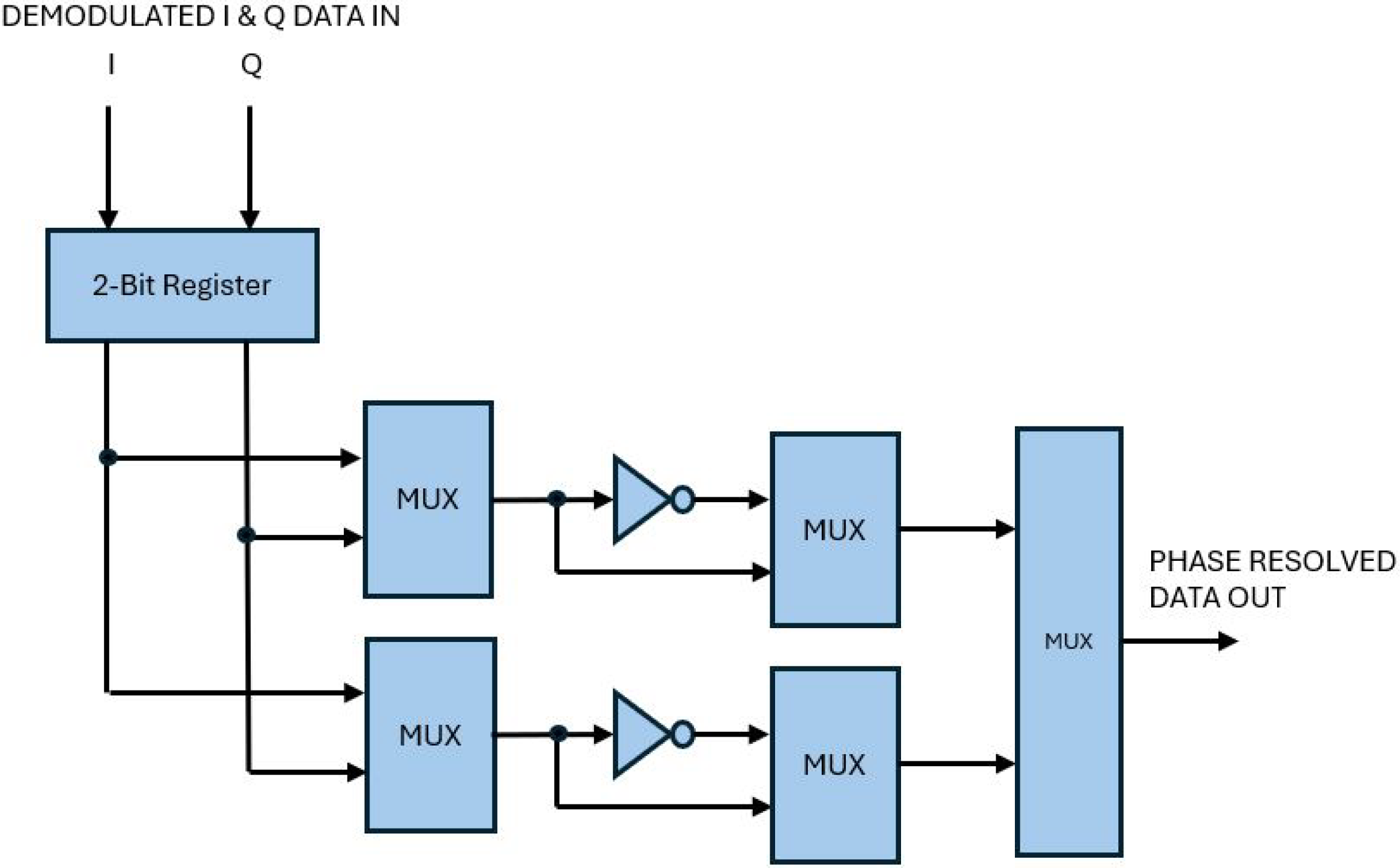

4.5. Phase Rotation Ambiguity Resolution

4.6. BPSK and QPSK Modulation

5. Synthesis Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A/D | Analog-to-Digital |

| ASM | Attached Synchronization Marker |

| AWGN | Additive White Gaussian Noise |

| BER | Bit Error Rate |

| BPSK | Binary Phase Shift Key |

| CADU | Channel Access Data Unit |

| CCSDS | Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems |

| CLPS | Commercial Lunar Space Services |

| Eb | Energy per Bit |

| Eb/No | Energy per Bit over Noise Spectral Density |

| FEC | Forward Error Correction |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| FS | Frame Synchronizer |

| ISS | International Space Station |

| LDPC | Low-Density Parity Check |

| No | Noise Spectral Density |

| QPSK | Quadrature Phase Shift Key |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

References

- G, A.; R, S.V.; Gupta Poddar, P. Framing and Synchronization of Satellite TTC Data. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belgaum, India, 27–29 May 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohith, P.; R, M. Comparative Analysis and Review of FPGA based FEC Codes. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Interdisciplinary Humanitarian Conference for Sustainability, Bengaluru, India, 18–19 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Galijasevic, S.; Wang, L.; Hamkins, J.; Wesel, R.; Divsalar, D. Construction of Low-Rate LDPC Codes from Rate-1/2 CCSDS Standard LDPC Codes. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 1–8 March 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeshma, T.N.; P, K. High-Speed Design Approaches for CCSDS LDPC Encoder Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE North Karnataka Subsection Flagship International Conference, Bagalkote, India, 21–22 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.; Zhang, G.; Jia, K.; Qin, Y. An efficient Multi-code LDPC Encoder for Deep Space Communication. In Proceedings of the 2024 The 9th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems, Xi’an, China, 19–22 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mostacero-Agama, L.; Shiguihara, P. Analysis of Internet Service Latency and its Impact on Internet of Things (IoT) Applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Engineering International Research Conference (EIRCON), Lima, Peru, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavinilavu, V.; Salivahanan, S.; Bhaaskaran, V.S.K.; Sakthikumaran, S.; Brindha, B.; Vinoth, C. Implementation of Convolutional encoder and Viterbi decoder using Verilog HDL. In Proceedings of the 2011 3rd International Conference on Electronics Computer Technology, Kanyakumari, India, 8–10 April 2011; Volume 1, pp. 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staphorst, L.; Linde, L. On the viterbi decoding of linear block codes. Trans. S. Afr. Inst. Electr. Eng. 2003, 94, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, L.; Pagani, E.; Bertolucci, M.; Fanucci, L. Implementation Strategies for Highly-accurate and Efficient Frame Synchronization Modules in Satellite Communication Receivers. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd Industrial Electronics Society Annual On-Line Conference (ONCON), Virtual, 8–10 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, N.; Allen, S.; Andrews, K.; Elliott, H.; Gladden, R.; Hamkins, J.; Kuperman, I.; Mendoza, R. Implementing Low-Density Parity-Check Codes in the Mars Relay Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Aerospace Conference (AERO), Big Sky, MT, USA, 5–12 March 2022; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maopei, L.; Tingxian, Z. Extrinsic Information Aided Frame Synchronizer for Turbo Code. In Proceedings of the 2005 5th International Conference on Information Communications & Signal Processing, Bangkok, Thailand, 6–9 December 2005; pp. 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdaljlil, S.A.; Zerek, A.R.; Daeri, A.; Eissa, H. BER Performance Analysis using TCM Coding Over AWGN and Fading Channels. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 2nd International Maghreb Meeting of the Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (MI-STA), Sabratha, Libya, 23–25 May 2022; pp. 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, P.S.; Utami, E.Y.D.; Timotius, I.K. Bit Error Rate Performance Comparison of Low-Density Parity-Check Code and Polar Code. In Proceedings of the 2023 29th International Conference on Telecommunications (ICT), Toba, Indonesia, 8–9 November 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, K.V.; Kumar, V.P.; Naidu, Y.N.G.; Reddy, B.P. Multi-Symbol Detection of QPSK Signal in Noisy Channel. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Modern Age Technologies for Health and Engineering Science (AMATHE), Shivamogga, India, 16–17 May 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, C.S.; Chie, C. Effect of signal transition variation on bit synchronizer performance. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1993, 41, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhitama, B.S.; Nasution, A.S.; Safitri, Y.D.; Rasyidy, F.H.; Dwi, A.A.P.B.; Jatmiko, N.W.; Suhermanto; Gunawan, H.; Munawar, S.T.A.; Darlis, D. Development of CCSDS Remote Sensing Satellite Raw data Extraction Based on Reed Solomon Code Using SoC Development Board. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Information Technology, Information Systems and Electrical Engineering (ICITISEE), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 29–30 August 2024; pp. 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šajić, S.; Maletić, N.; Šunjevarić, M.; Todorović, B. Low-cost digital correlator for frequency hopping radio. In Proceedings of the 2011 18th International Conference on Systems, Signals and Image Processing, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 16–18 June 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, C.; Swanson, L.; Pitt, G., III. Frame synchronization performance and analysis. In The Telecommunications and Data Acquisition Report; NASA: Pasadena, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, J. Optimum Frame Synchronization. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1972, 20, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiani, M.; Martini, M.G. Analysis of Optimum Frame Synchronization Based on Periodically Embedded Sync Words. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2007, 55, 2056–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shongwe, T. Analysis of the Probability of Sync-Words in Reed–Solomon Codes. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2017, 21, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; Jun, Y.; Eryang, Z. The research on joint frame synchronization and phase ambiguity resolution for high data rate M-PSK systems. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd IEEE International Conference on Information Management and Engineering, Chengdu, China, 16–18 April 2010; pp. 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotindjo, P.; Agossou, C.M.M.; Sanya, M.F.O.; Comlan, M.; Akakpo, M.A.; Vianou, A. Study of the impact of constellation rotation in a BAB+ transmission. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th Interdisciplinary Conference on Electrics and Computer (INTCEC), Chicago, IL, USA, 11–13 June 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierhuis, M.; Clancey, W.J.; van Hoof, R.J.; Seah, C.H.; Scott, M.S.; Nado, R.A.; Blumenberg, S.F.; Shafto, M.G.; Anderson, B.L.; Bruins, A.C.; et al. NASA’s OCA Mirroring System: An application of multiagent systems in Mission Control. In Proceedings of the Autonomous Agents and Multi Agent Conference, Budapest, Hungary, 10–15 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, P.; Heckler, G.; Arnold, B.; Berner, J.; Weir, E.; McCarthy, A. NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) Lunar Exploration Upgrades (DLEU). In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Space Operations, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 6–10 March 2023. ID #558. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Geng, T.; Ma, S.; Li, L.; Gao, S.; Li, Y. Non-Data-Aided Cycle Slip Self-Correcting Carrier Phase Estimation for QPSK Modulation Format of Coherent Wireless Optical Communication System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 110451–110462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, I. Error Control: Please Send It Again. In Principles of Data Transfer Through Communications Networks, the Internet, and Autonomous Mobiles; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 397–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 9.0 | SYNCHRONIZATION |

| 9.2 | ATTACHED SYNC MARKER (ASM) |

| 9.4 | LOCATION OF ASM |

| 10 | PSEUDO-RANDOMIZER |

| 11 | TRANSFER FRAME LENGTHS |

| PIPELINE STAGES | LOGIC ELEMENTS | COMBINATIONAL | REGISTERS | MEMORY BITS | FMAX (MHz) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparators | 1 | 90 | 89 | 19 | 0 | 277 |

| Adders | 1 | 14 | 7 | 14 | 0 | 340 |

| Horizontal Pipeline | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2176 | 163 |

| PIPELINE STAGES | LOGIC ELEMENTS | COMBINATIONAL | REGISTERS | MEMORY BITS | FMAX (MHz) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparators | 2 | 96 | 92 | 27 | 0 | 336 |

| Adders | 2 | 24 | 7 | 21 | 0 | 340 |

| Horizontal Pipeline | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2176 | 163 |

| PIPELINE STAGES | LOGIC ELEMENTS | COMBINATIONAL | REGISTERS | MEMORY BITS | FMAX (MHz) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparators | 3 | 96 | 92 | 28 | 0 | 340 |

| Adders | 3 | 32 | 7 | 78 | 0 | 340 |

| Horizontal Pipeline | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2176 | 163 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cavazos, J.; Chen, Y. A Pipelined FPGA-Based Frame Synchronizer for Gaussian Noise Channels. Electronics 2025, 14, 4724. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234724

Cavazos J, Chen Y. A Pipelined FPGA-Based Frame Synchronizer for Gaussian Noise Channels. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4724. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234724

Chicago/Turabian StyleCavazos, Joe, and Yuhua Chen. 2025. "A Pipelined FPGA-Based Frame Synchronizer for Gaussian Noise Channels" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4724. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234724

APA StyleCavazos, J., & Chen, Y. (2025). A Pipelined FPGA-Based Frame Synchronizer for Gaussian Noise Channels. Electronics, 14(23), 4724. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234724