4. Proposed Hybrid DL-Enhanced

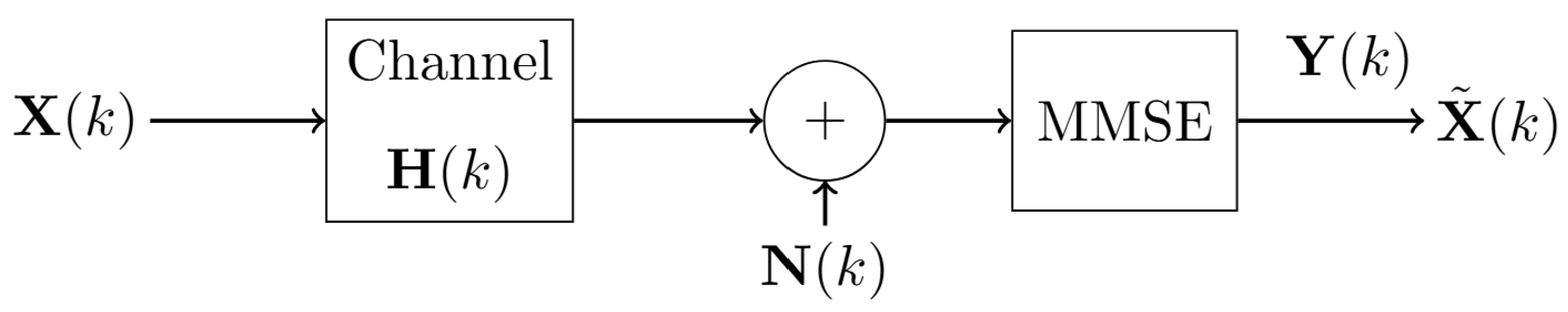

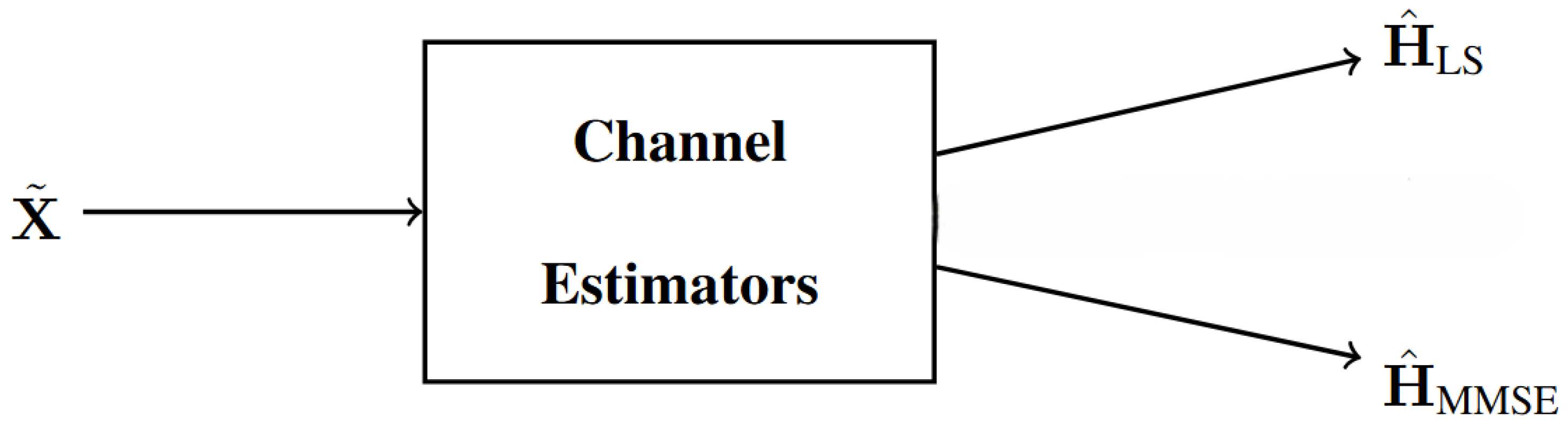

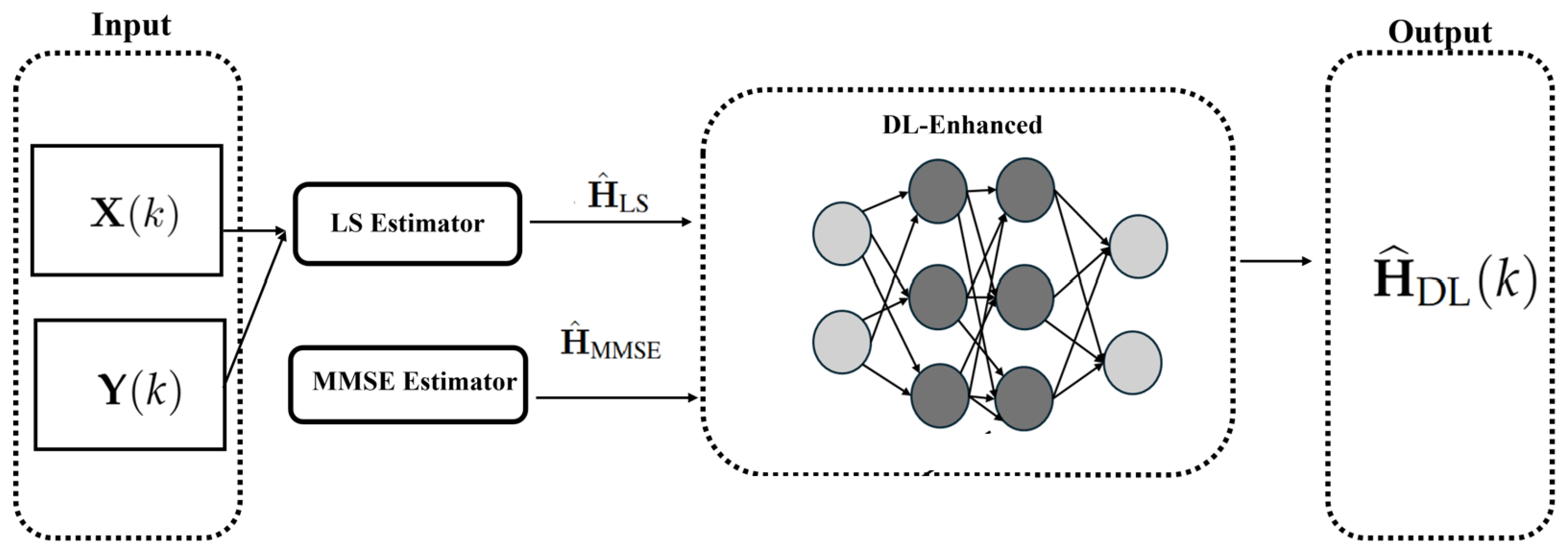

The proposed DL-Enhanced has two lightweight learning phases integrated with classical processing: a channel-level fusion that performs a convex magnitude combination of and under a simplex constraint while restoring the LS phase, and a symbol-level I/Q denoiser applied after linear MMSE equalization. A single decision-directed iteration refines the channel estimate using reliable hard decisions, and final detection uses MMSE equalization. At the channel estimation level, a compact fusion MLP consumes physics-inspired features distilled from the LS and MMSE estimates. At the symbol-processing level, a per-transmitter I/Q denoiser MLP is applied after linear MMSE equalization to refine the in-phase and quadrature components. This combination reduces the structural channel-estimation error while preserving the phase and mitigates residual post-equalization noise at negligible additional complexity.

In combination, the channel-level fusion reduces structural estimation errors while explicitly preserving the phase, whereas the symbol-level denoiser mitigates residual noise and mild distortions at the detector output. Both blocks add negligible complexity relative to standard equalization and are compatible with a single DD polishing step.

Figure 4 provides a block-level view of the two-phase DL-Enhanced receiver and its integration with classical methods.

4.1. Architecture

The DL fusion component uses self-supervised training. An MLP takes features extracted from

and

as input and outputs fusion weights

for

with

and

. The fused magnitude is combined with the LS phase to avoid angle drift:

A second DL component implements per-transmitter I/Q denoisers. After MMSE equalization, each denoiser refines the real and imaginary parts of the equalized symbols, reducing residual noise and mild distortions.

A single decision-directed iteration uses reliable hard decisions to update the channel estimate prior to the final MMSE detection. Final equalization on each subcarrier uses

4.2. Theoretical Rationale for Phase-Preserving Fusion

For a fixed subcarrier, let

be the true coefficient and let

and

be the pilot-aided hypotheses produced by LS and MMSE, respectively. We assume the standard small-error regime at moderate/high SNRs, where

are zero-mean circular complex random variables with finite second moments, possibly correlated (because the MMSE smoothing is built on the LS seed). Denote magnitudes

,

and the LS-phase error

.

Rationale for preserving phase. Write and . For small complex perturbations and circular noise, , hence and . Unconstrained complex regressors that average phases can introduce a bias and inflate by angle wrapping. For phase-modulated constellations, the effective SNR degrades as (QPSK) or, more generally, with modulation-dependent . Enforcing guarantees and to first order; the fusion then acts only on the magnitude, where convex gains are attainable.

Magnitude-risk dominance under convex fusion. Define the magnitude risk

. Since

is a convex quadratic on

, its minimum on the simplex never exceeds the endpoint risks:

Taking expectations and using Jensen,

Thus, an oracle

that selects the best convex combination per realization strictly dominates both LS and MMSE magnitudes in expected squared error. The learned weight

obeys the non-expansive simplex projection; if the MLP output is

L-Lipschitz in the features, the excess magnitude risk satisfies

for a constant

C that depends only on bounded magnitudes. With well-conditioned features, the learned fusion is stable and near-oracle.

MSE decomposition and scaling with the SNR. Let

with

being the fused magnitude error. For small

,

MMSE magnitude errors obey

, and LS has the same order with a larger constant due to interpolation noise amplification. By the dominance bound above, the fused magnitude term matches the better of the two to first order. The phase term is exactly that of LS (by construction) and scales as

. Therefore, the NMSE slope of the proposed estimator equals the best magnitude slope among {LS,MMSE} while inheriting the unbiased LS phase, which is the regime where BER gaps open at a medium/high SNR.

Impact on coherent detection (QPSK, first-order). With linear MMSE equalization and residual phase

at the channel estimate, the decision SNR degrades as

. Using

and

,

Byanchoring the phase to LS, we keep

at its unbiased LS value; the fusion then reduces

toward MMSE, yielding a strictly better (or equal) BER than either hypothesis alone. The empirical gaps reported in

Section 5 at 10–15 dB are consistent with this expression for the measured

.

Decision-directed single iteration and variance reduction. Let

be the fraction of subcarriers promoted to “virtual pilots” by the reliability mask and

be their average decision reliability (

). In the LS update with

true pilots, the effective sample size becomes

and the variance in the LS seed scales approximately as

For the pilot layouts used here, typical

in the 10–15 dB range yields a 3–4 dB NMSE improvement.

Stability and robustness. Simplex projection is 1-Lipschitz, so the fusion weights are robust to feature noise. Phase restitution prevents angle wrapping and ensures BIBO stability in the phase channel. Cross-SNR generalization follows from the continuity of the feature-to-weight map; empirically, the held-out SNR experiments in

Section 5 show negligible degradation, which is consistent with the excess-risk bound above.

Summary of quantitative takeaways. (i) The fused magnitude matches or improves LS/MMSE in expectation via convex dominance; (ii) the phase term equals the unbiased LS phase to first order, avoiding BER loss from phase drift; (iii) a single DD iteration shrinks variance roughly as , explaining the observed 3–4 dB NMSE gains over fusion-only.

4.3. Training

Training is fully self-supervised and does not use the true channel as labels. Each sample is generated by drawing a random MIMO channel and building an OFDM frame with pilots and QPSK data, which is then transmitted to obtain .

From , the receiver first computes two classical channel estimates per link, Least Squares and MMSE-smoothed. Physics-inspired features are extracted from these hypotheses (normalized SNR, LS and MMSE variability, relative LS–MMSE gap, temporal dispersion from the power delay profile, and a bias term).

Each feature is normalized to the interval [0.01, 0.99] to keep inputs well-conditioned and to avoid outlier saturation. Specifically, the SNR is linearly mapped from the value in dB to a number proportional to the SNR in dB divided by 50 and then clipped to the [0.01, 0.99] range. LS and MMSE variability are expressed as dimensionless coefficients of variation in the magnitudes. The LS–MMSE discrepancy is a normalized mean absolute gap, temporal dispersion is the second central moment of the aggregate power-delay profile normalized by the subcarrier span. We kept exactly six inputs to cover noise level, within-estimator variability, cross-estimator discrepancy, and delay spread with minimal dimensionality, which empirically reduced overfitting and yielded stable validation loss.

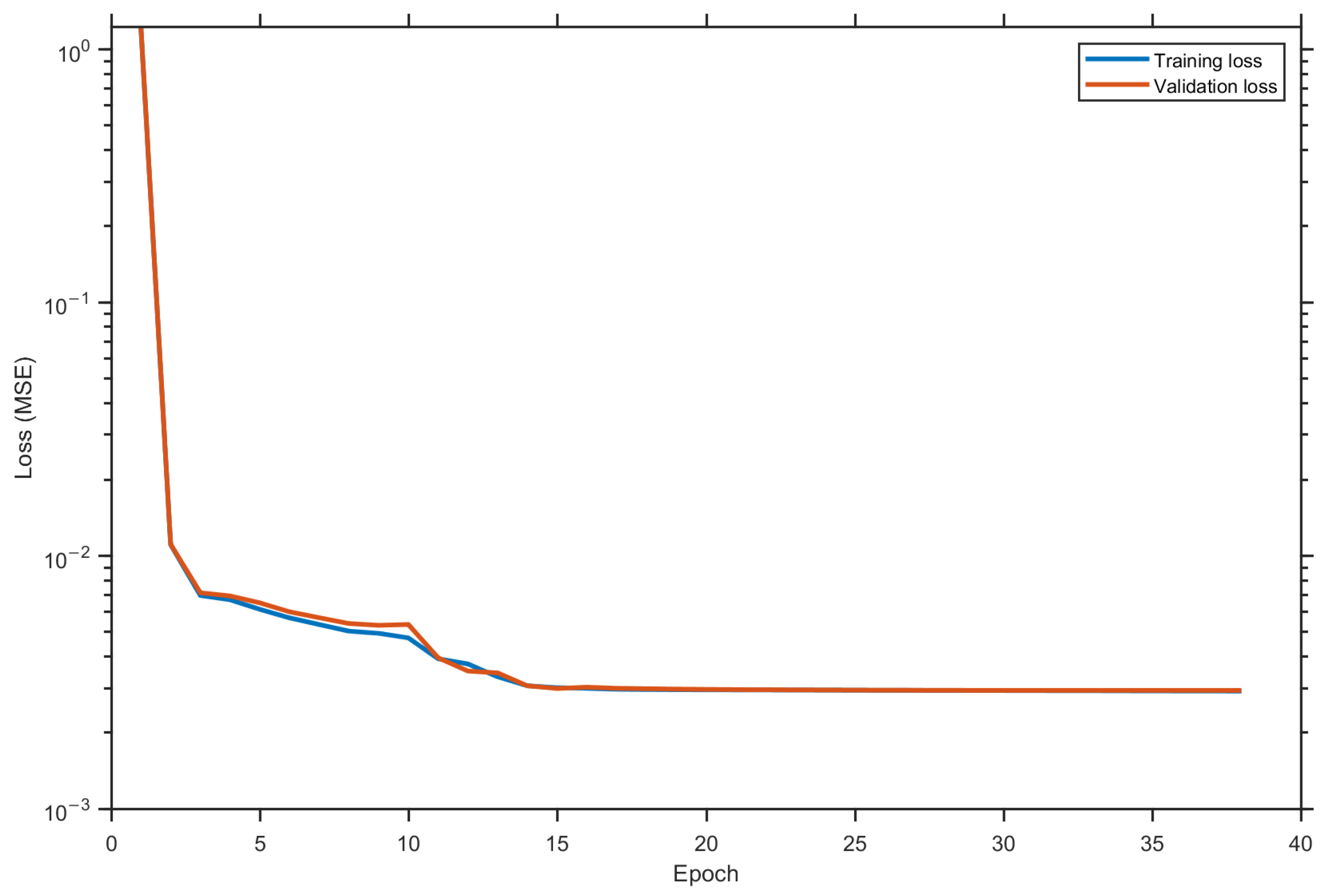

Figure 5 summarizes the learning dynamics of the self-supervised fusion network; the training and validation curves almost overlap over the epochs and reach a common plateau, indicating stable convergence with no signs of overfitting. This behavior suggests that the model constraints and training are sufficient to prevent the network from fitting noise patterns.

To ensure stable convergence without access to true channels, we combine model-based constraints with conservative training. The fusion network outputs are projected onto the probability simplex, enforcing non-negative weights that sum to one. The fused magnitude is always combined with the LS phase, which prevents angle drift in the receiver. For the symbol domain denoiser, we only use high-confidence hard decisions selected by a reliability mask, reducing target noise. Validation uses an 80/20 split by channel with no overlap across SNRs between training and validation, and the final model is selected by early stopping at the best validation epoch. The training and validation losses decrease together and flatten at the same level, indicating convergence without overfitting.

For each sample, optimal fusion weights are obtained without access to the true channel by matching the received vector through a real-valued Least-Squares problem that linearly combines the LS- and MMSE-predicted receive signals; the solution is projected onto the probability simplex to enforce non-negativity and unit sum, yielding the target weights. An MLP with topology maps to the predicted weights, trained with a mean-squared error between the simplex-projected output and the target.

A second self-supervised dataset is formed for symbol denoising. Equalization produces , hard QPSK decisions yield clean targets, and a confidence mask selects reliable samples. Inputs are the real and imaginary parts of . Targets are the corresponding parts of the reliable hard decisions. One MLP per transmit antenna with topology is trained with mean-squared error and later applied to refine the equalized symbols for all baselines.

The fusion MLP is trained with 1000 channel realizations on an SNR grid from 0 to 15 dB in 2 dB steps (9 points), producing 9000 samples. Data are split 80/20 by channel with no SNR overlap between training and validation. Optimization uses Levenberg–Marquardt (full-batch) with 200 maximum epochs and early stopping based on validation loss. The per-transmitter I/Q denoiser uses 1000 channels and the same 9-point SNR grid, and it is trained with Adam (initial learning rate 1 × 10−3, mini-batch 1024, 40 epochs) using reliability-filtered hard decisions as targets. For the auxiliary 4 × 2 and 8 × 4 results, the fusion MLP is trained with 300 channels on the same SNR grid (2700 samples) per configuration.

5. Simulation Setup and Results

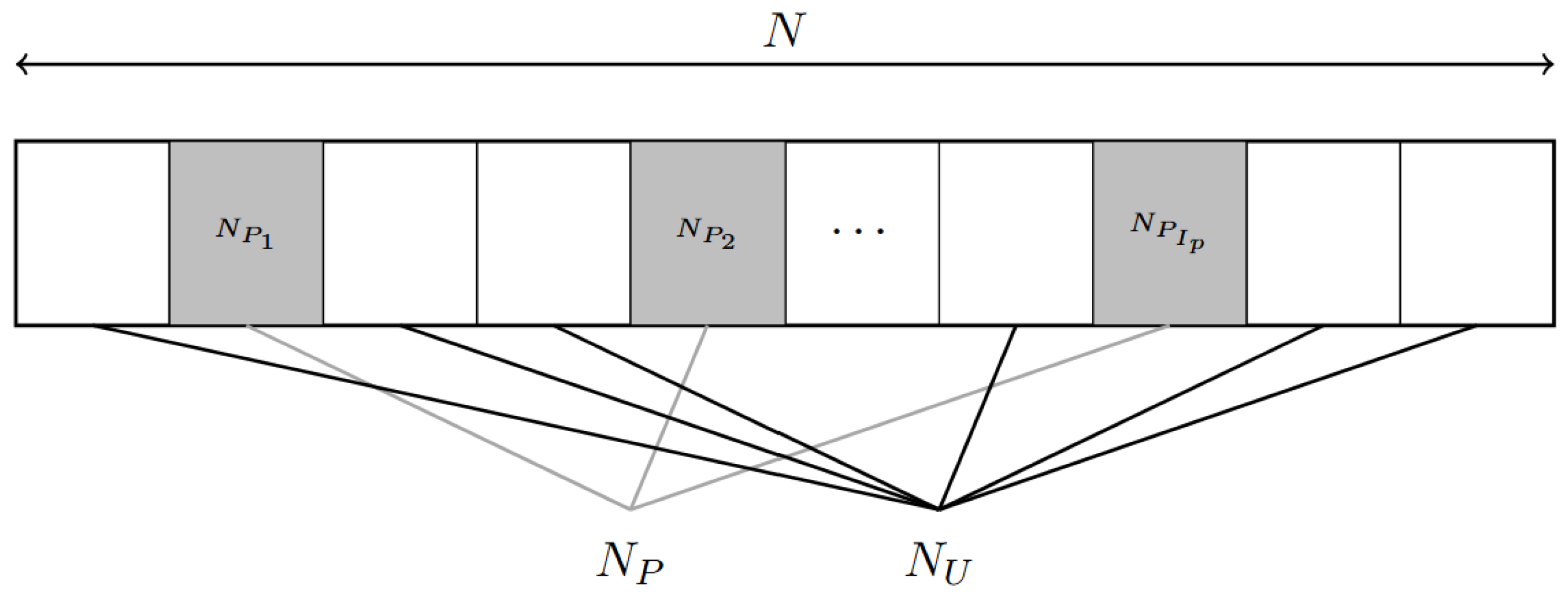

In this section, we evaluate the proposed hybrid channel estimation on a QPSK MIMO–OFDM system with three MIMO configurations using the convention , , and . We evaluate BER and effective throughput, where effective throughput is defined as the number of information bits successfully delivered per channel use computed by multiplying the fraction of subcarriers that carry data excluding pilots by the number of transmit antennas and the QPSK bits per symbol and scaling by one minus the measured Bit Error Rate (BER).The SNR is swept from 0 to 15 dB in 2 dB steps.

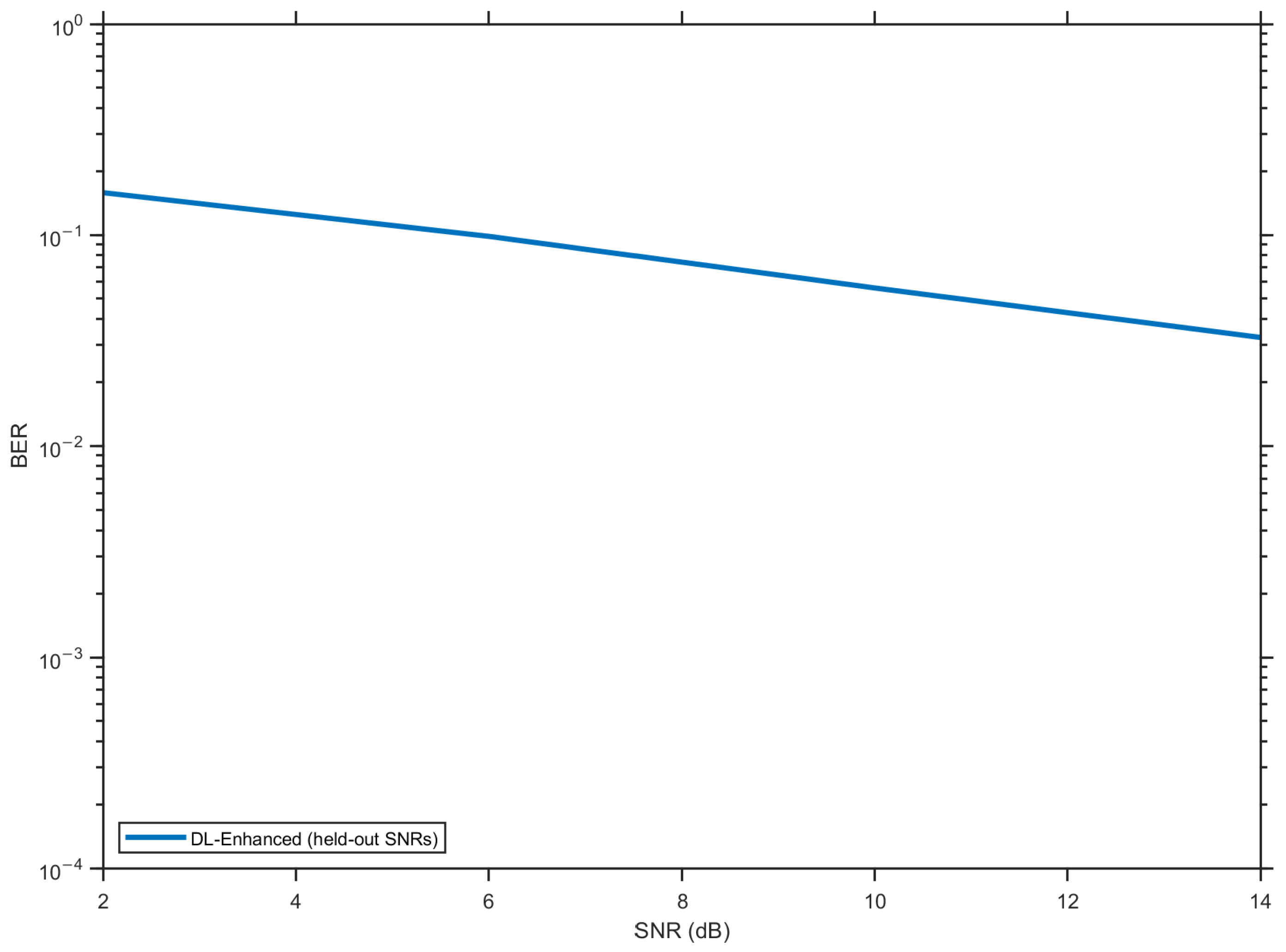

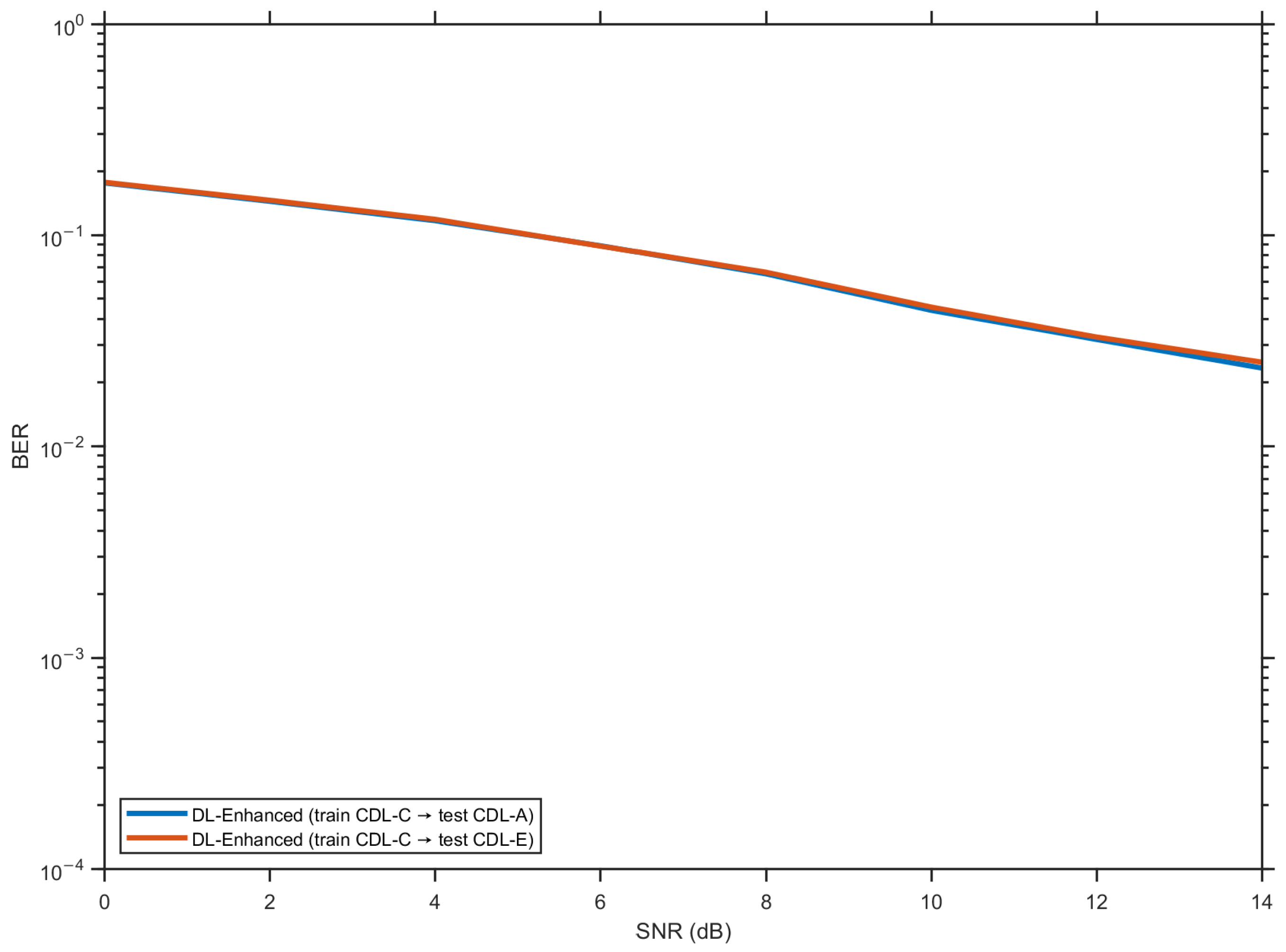

Beyond the main setup, we explicitly assess generalization along three axes. First, we test on unseen SNR points via an SNR hold-out, training on alternating SNRs (e.g., {0,4,8,12,15} dB) and evaluating on the interleaved set ({2,6,10,14} dB). Second, we examine scalability across antenna configurations by reporting results for 2 × 2, 4 × 2, and 8 × 4 arrays (the compact fusion MLP is retrained per array size, and no architectural changes are needed). Third, we evaluate zero-shot channel-profile transfer by training on CDL-C and testing, without retraining, on CDL-A and CDL-E. In all cases, the DL-Enhanced estimator preserves its margin over MMSE in both BER and NMSE. The two plots in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 illustrate the hold-out SNR and the CDL-C→A/E transfers, respectively.

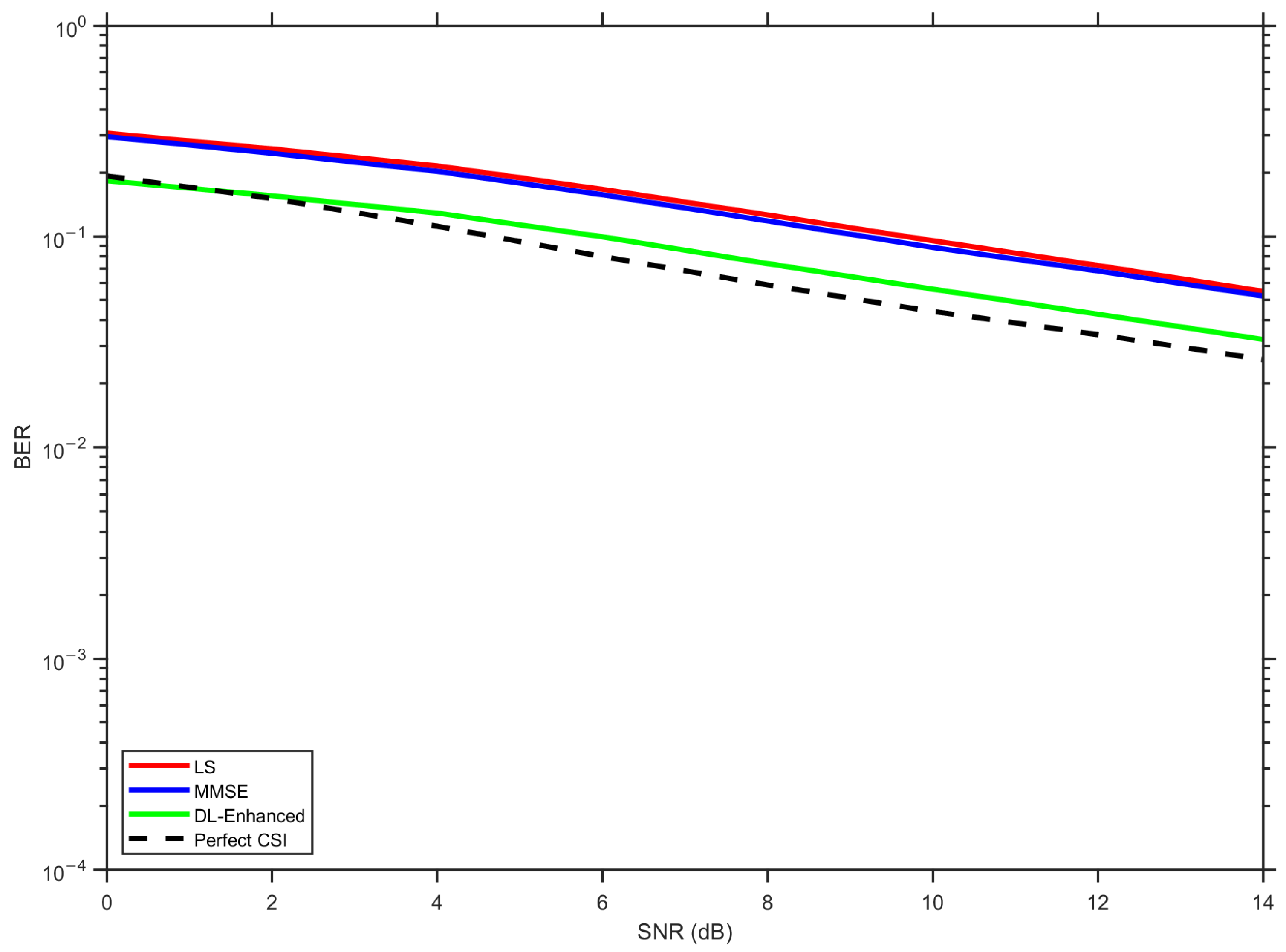

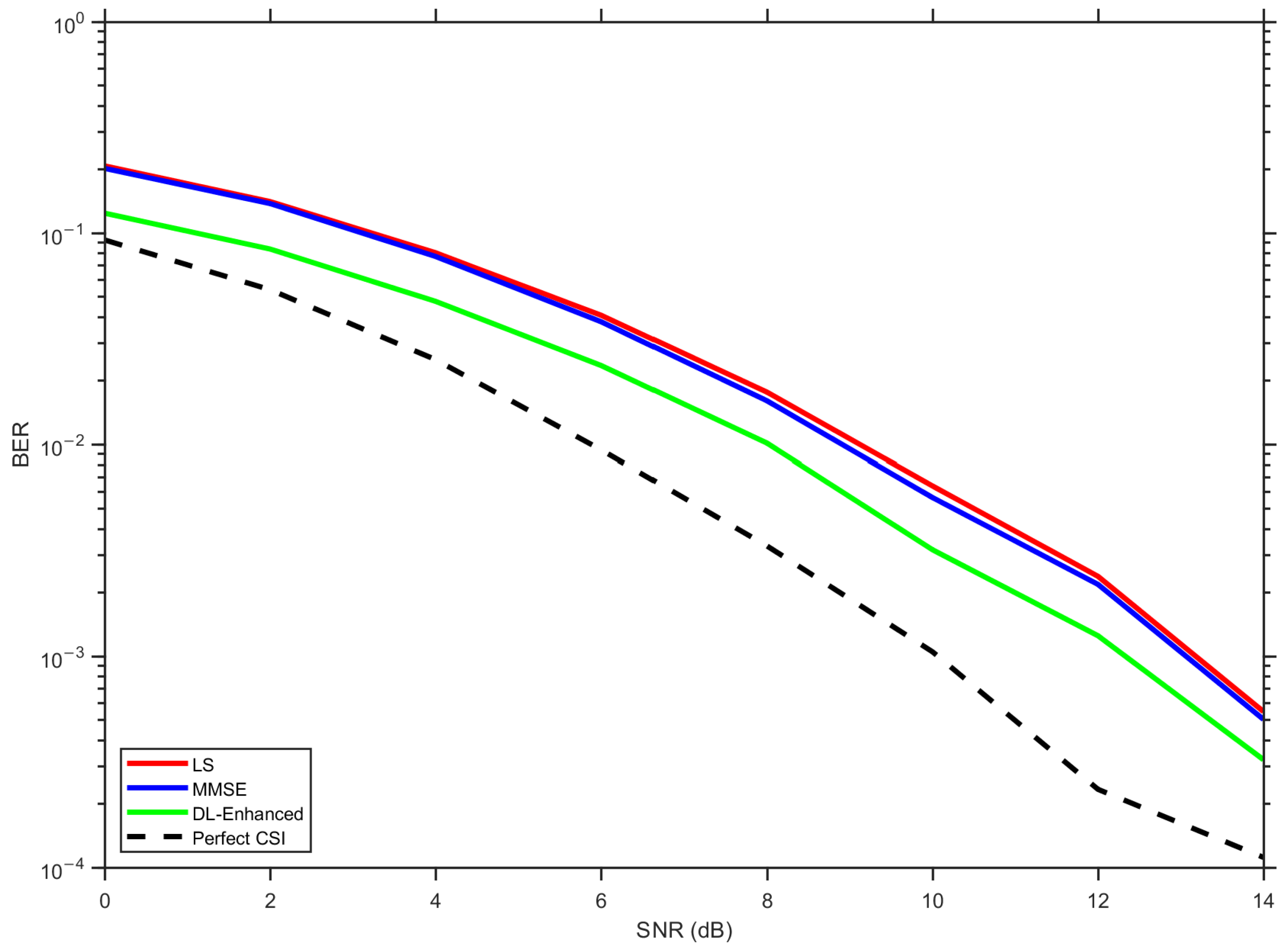

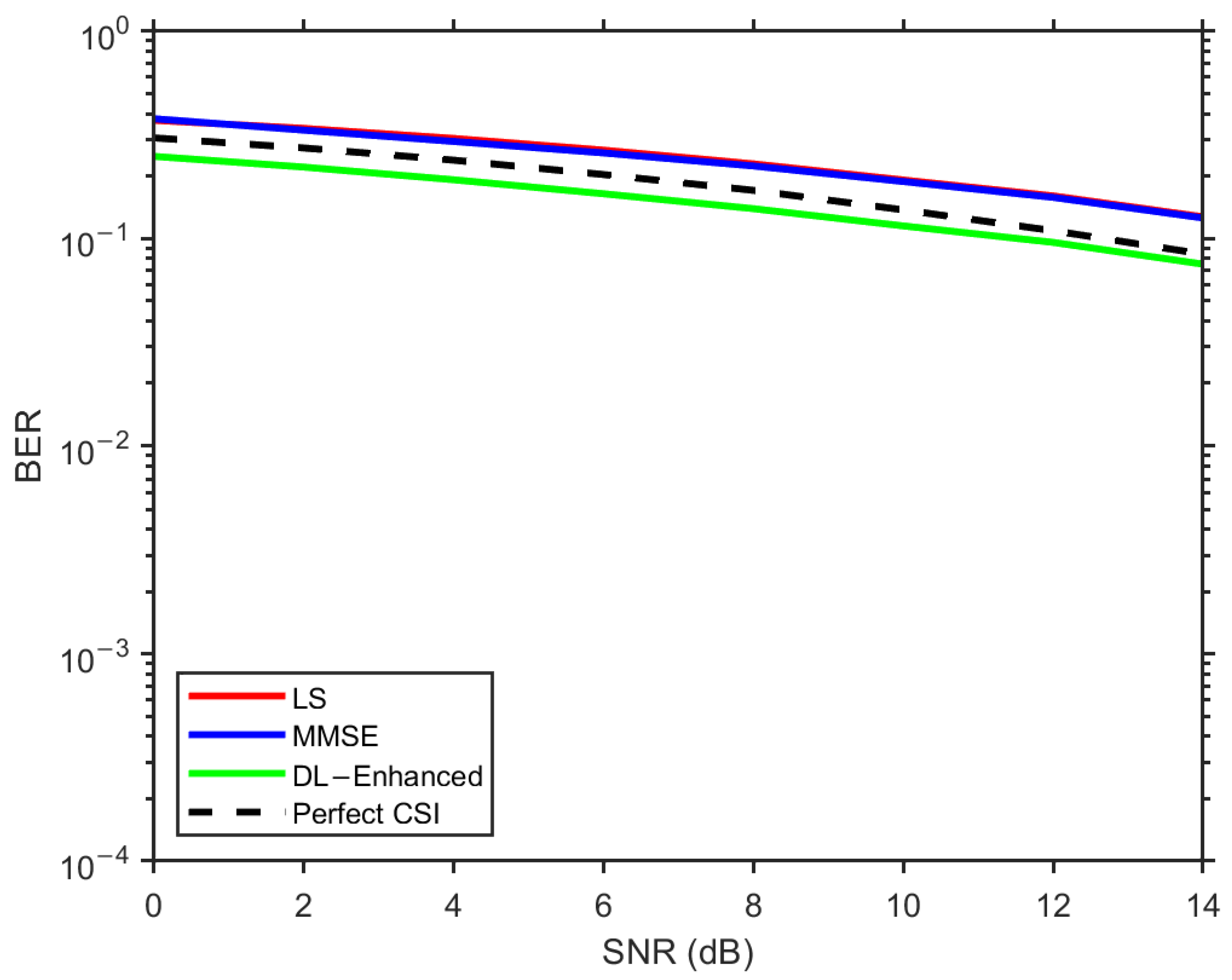

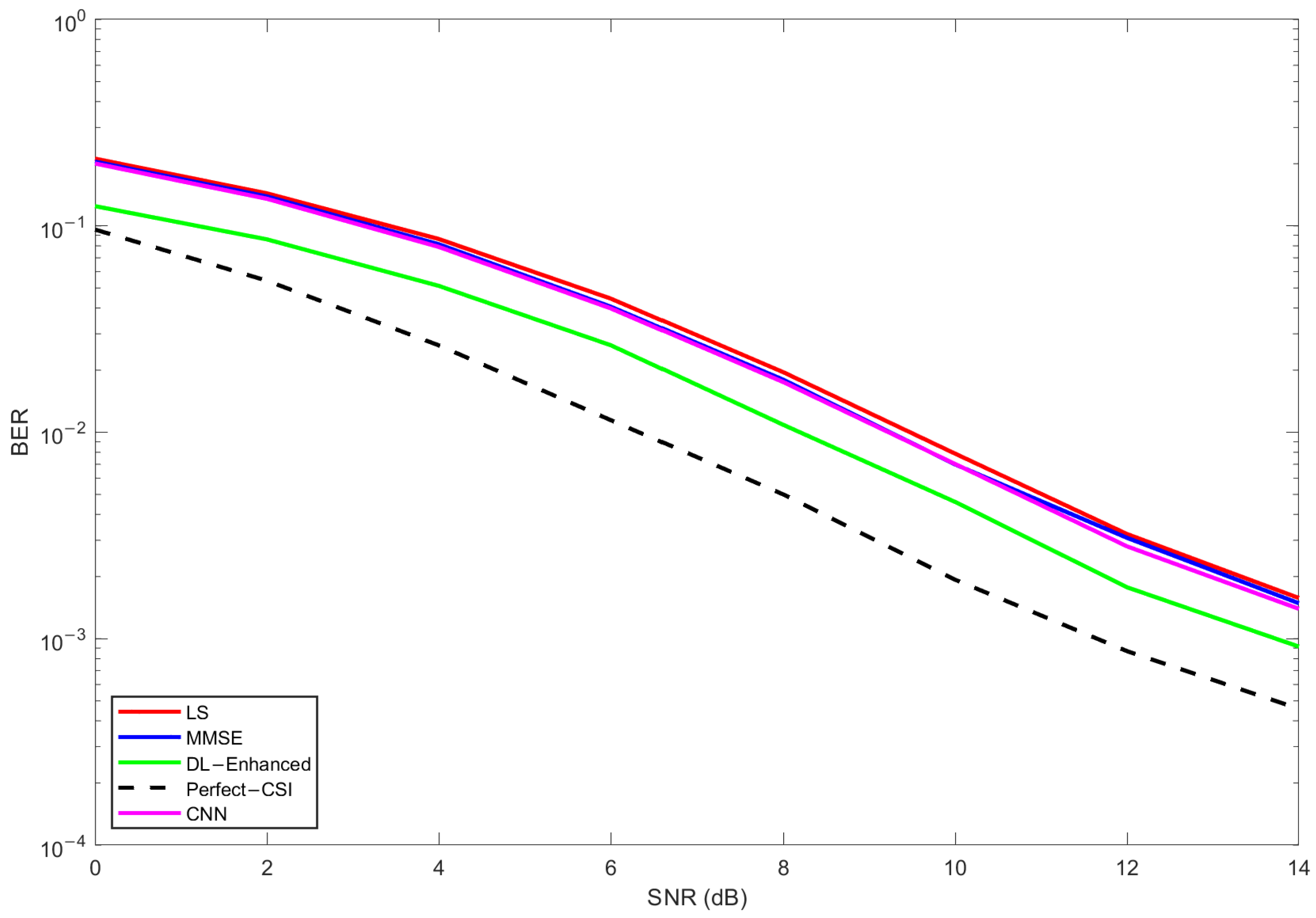

Figure 8 shows the BER obtained with a

MIMO configuration.

As can be observed from the figure, LS and MMSE estimators follow the expected trend, and LS exhibits the largest error floor due to noise amplification and interpolation errors, while MMSE improves on LS by incorporating prior delay-domain statistics but still departs from the perfect CSI bound at a moderate-to-high SNR. The proposed DL-Enhanced fusion remains consistently below MMSE for the entire SNR range, with visible gains, especially as the SNR increases. At low-SNR values between 0 and 5 dB, the curves are close because detection is fundamentally noise-limited and none of the estimators can fully overcome the random perturbations. In this regime, the fusion network assigns relatively balanced weights to both hypotheses, effectively averaging their contributions. As the SNR increases to the range of 10–15 dB, the performance gap becomes more evident. The convex fusion mechanism shifts emphasis toward the higher-quality hypothesis, which allows the magnitude estimate to remain accurate even when the individual methods diverge. At the same time, LS-phase anchoring prevents the angle drift that typically arises in purely data-driven complex regression, ensuring that the fused channel maintains consistent phase information for coherent detection. The optional DD update also contributes in this region. With more reliable symbol estimates available at higher SNRs, a single DD iteration can reinforce the pilot set with additional subcarriers while keeping the computational overhead low. This further stabilizes the equalizer without the cost of multiple feedback loops. The combined effect is a performance that lies significantly closer to the perfect CSI reference than MMSE and is well-separated from LS. These results confirm that the proposed hybrid architecture not only generalizes well in training but also translates into tangible performance gains under practical operating conditions.

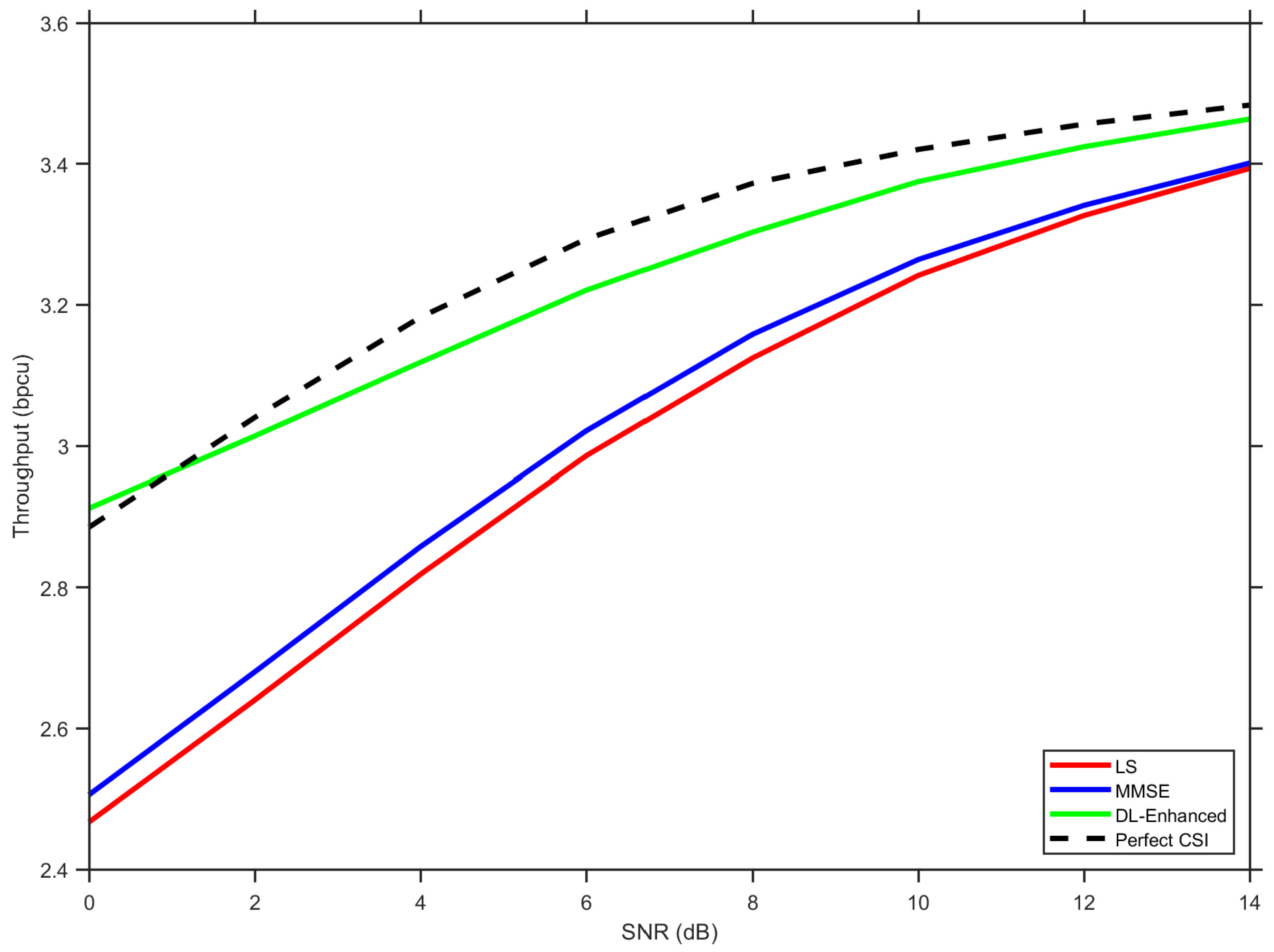

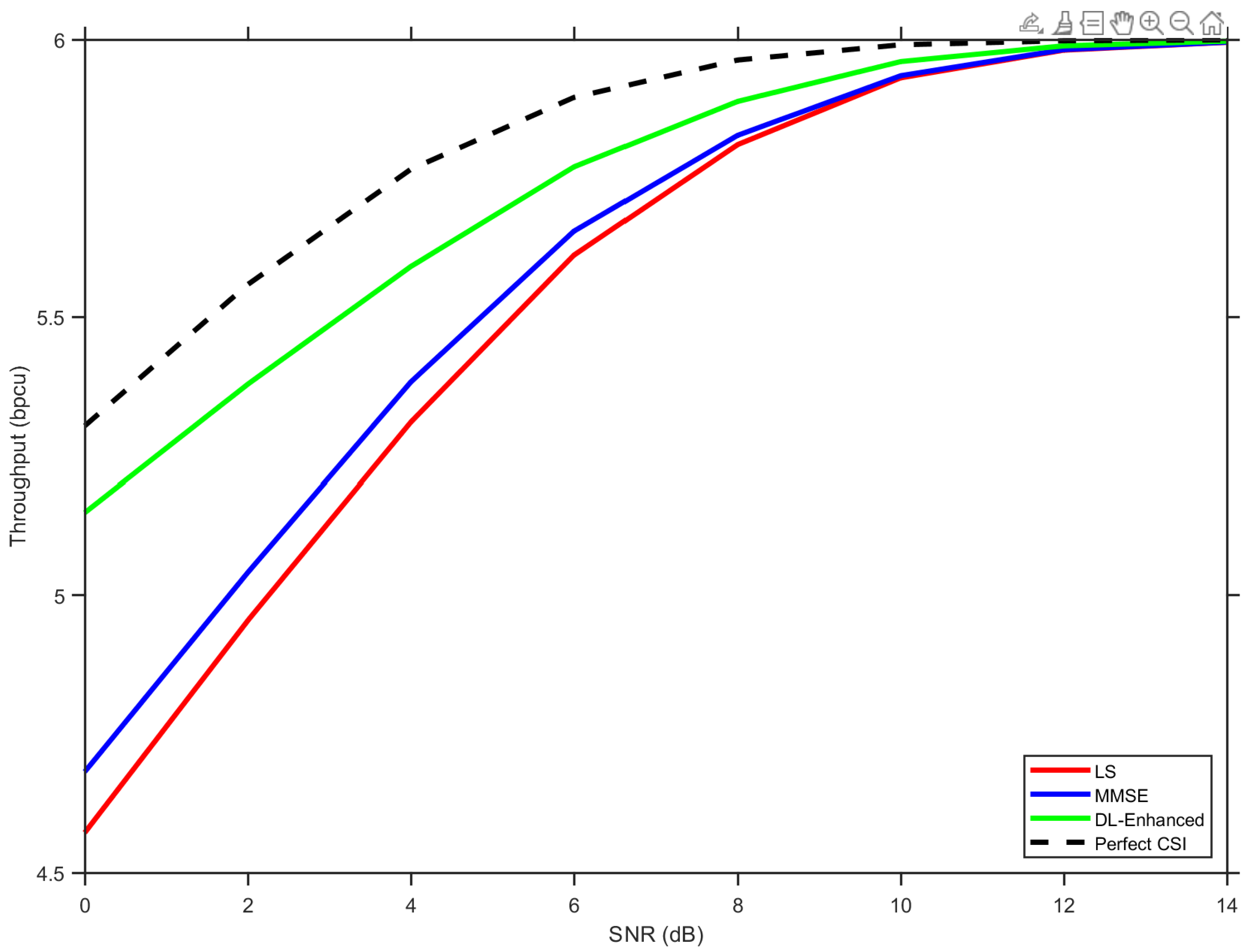

Figure 9 illustrates the throughput performance across the considered SNR range. At a low SNR (0–5 dB), all methods suffer from significant BER-induced capacity loss, with LS performing worst due to its higher error floor. The DL-Enhanced approach maintains a consistent advantage over both baselines, approaching the perfect CSI bound more closely as the SNR increases.

The throughput gap becomes particularly pronounced at higher SNR values. At 15 dB, DL-Enhanced achieves approximately 3.46 bpcu compared to 3.41 bpcu for MMSE and 3.40 bpcu for LS, representing relative improvements of 1.5% and 1.8%, respectively. While these gains may appear modest in absolute terms, they translate to meaningful capacity increases in bandwidth-limited scenarios. The consistent separation from the baselines across the entire SNR range demonstrates the robustness of the hybrid fusion approach.

The throughput analysis confirms that the proposed method not only reduces BER but also translates these gains into practical system-level improvements. The convex fusion mechanism effectively leverages the complementary strengths of LS and MMSE estimation, while the phase anchoring and DD refinement maintain reliable performance without significant computational overhead.

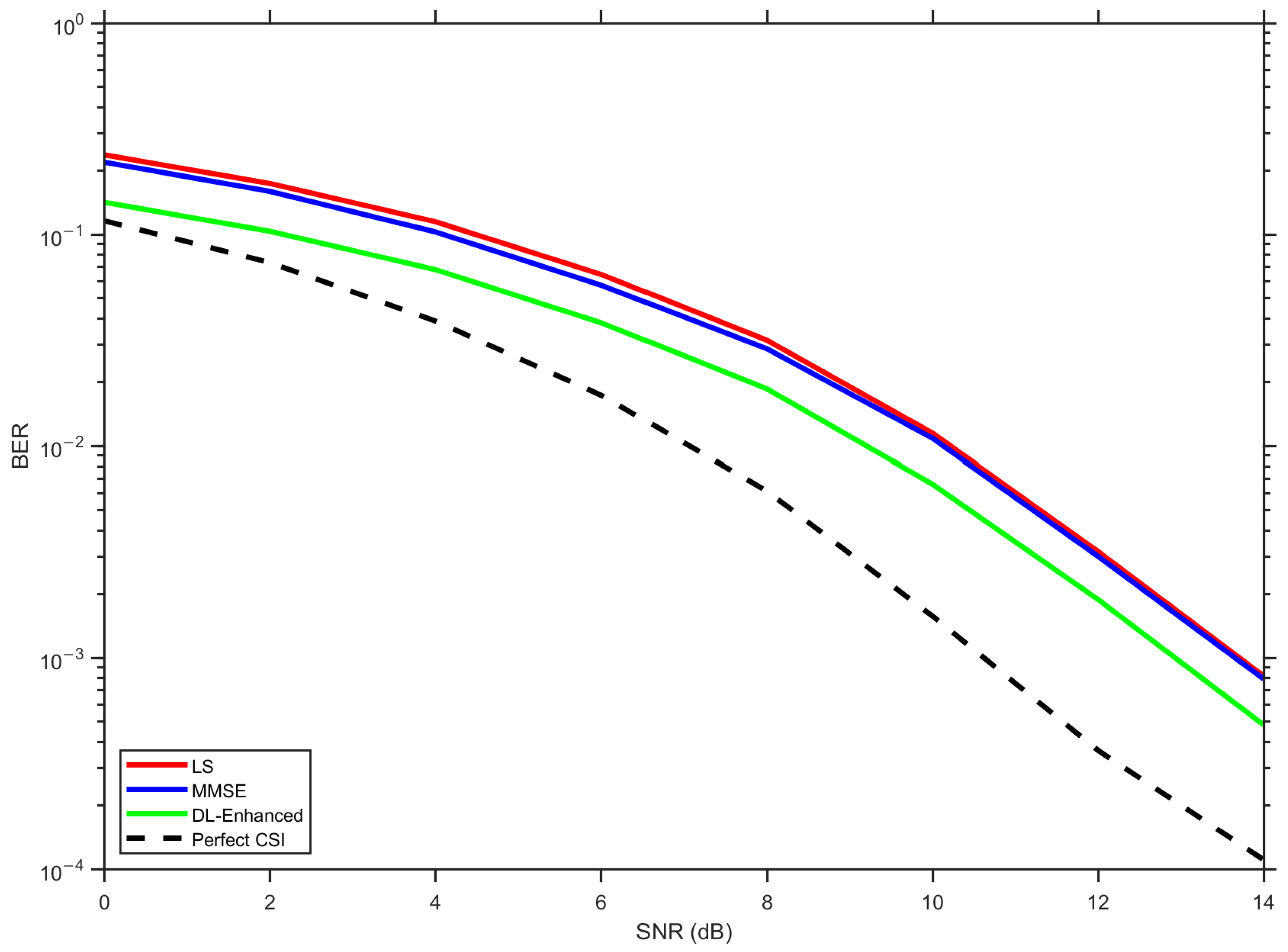

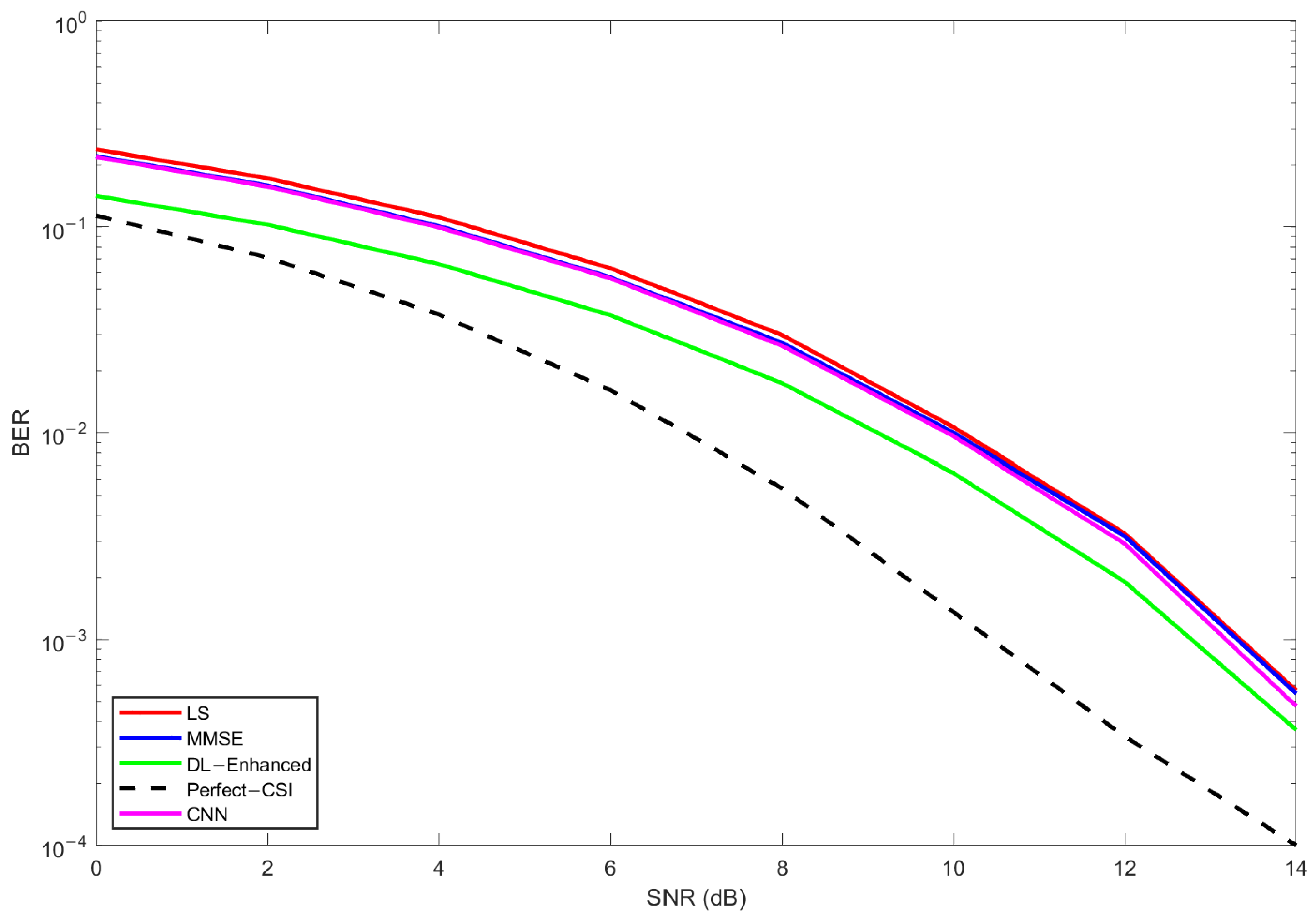

Figure 10 illustrates the impact of increasing the number of receive antennas from

to

while keeping

. As expected, receive diversity shifts all curves downward, since additional spatial observations improve estimation quality and detection robustness.

The relative ordering of the methods is preserved, with LS showing the highest BER, MMSE offering a moderate improvement, and the proposed DL-Enhanced approach producing the best performance among the practical estimators. The performance gap between DL-Enhanced and MMSE becomes more pronounced in the medium-to-high SNR range. Above about an SNR of 10 dB, the fusion network benefits from richer statistics discrepancies between the LS and MMSE, and hypotheses become more informative, allowing the MLP to assign weights more decisively depending on channel conditions. The simplex projection guarantees that the learned weights remain stable and non-negative, while LS-based phase anchoring prevents phase slips that can otherwise impair coherent detection at high SNRs when magnitudes are already nearly noise-free. These mechanisms yield a BER curve that tracks the perfect CSI bound more closely than MMSE, especially as the SNR grows. The results confirm that the proposed hybrid retains its generalization ability when scaling to larger antenna configurations and that its benefits increase with receive diversity. This demonstrates that the architecture is not only robust in small arrays but also scalable to larger and richer MIMO scenarios, preserving the balance between data-driven adaptation and physically grounded constraints.

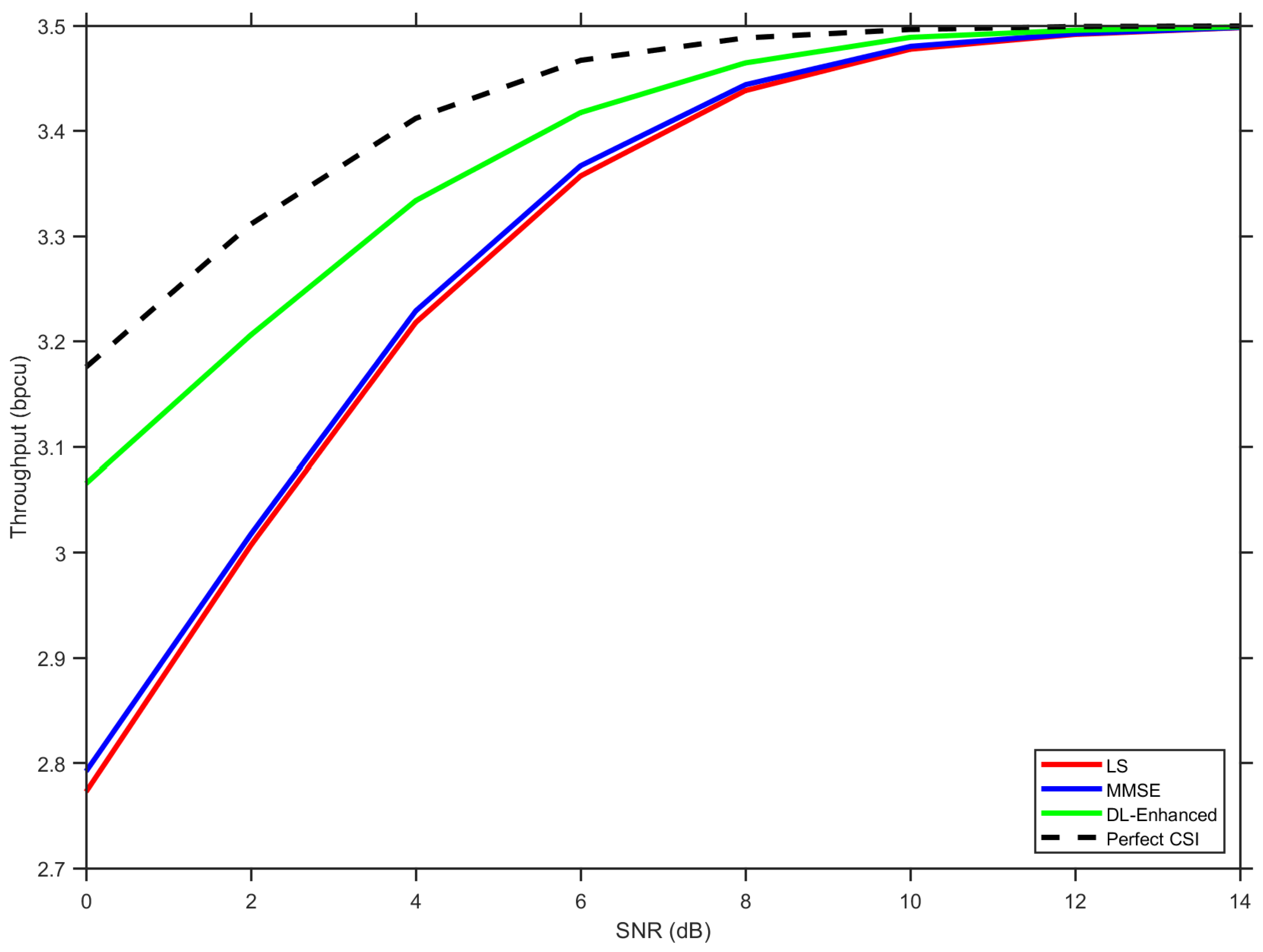

Figure 11 demonstrates the benefit of additional receive antennas on the throughput performance. The four receive antennas provide enhanced spatial diversity, allowing all estimation methods to achieve higher effective capacity at lower SNR values compared to the

case. At an SNR of 0 dB, the system achieves approximately 2.77 bpcu across all methods, representing improved noise resilience.

The DL-Enhanced approach maintains its performance advantage throughout the SNR range, with the gap becoming particularly evident in the transition region between 2 and 8 dB. The fusion network’s ability to exploit the complementary characteristics of LS and MMSE estimates becomes more pronounced with increased receive diversity, as the additional spatial observations provide richer statistical information for the adaptive weighting mechanism. In the high-SNR regime above 10 dB, all curves approach the theoretical limit more closely than in the configuration. At 15 dB, DL-Enhanced achieves approximately 3.49 bpcu, virtually identical to the perfect CSI bound, while MMSE reaches 3.48 bpcu and LS attains 3.47 bpcu. The relative improvements remain consistent with the case but occur at more favorable operating SNRs due to the diversity gain.

The

case in

Figure 12 further reduces absolute BER thanks to higher spatial diversity and multiplexing. Importantly, the DL-Enhanced approach remains the most accurate non-genie estimator at all tested SNRs and the closest to perfect CSI, which indicates that the two main ingredients of the architecture—simplex-constrained fusion and LS-phase preservation with one DD refinement—generalize beyond small arrays. As the arrays become larger, the gap to perfect CSI shrinks, especially at medium–high SNRs, suggesting that the residual error of the hybrid is dominated by small magnitude mismatches, since phase errors have been effectively suppressed. The

configuration demonstrates the scalability of the proposed method, achieving BER values approaching

at a 15 dB SNR while maintaining consistent gains over traditional methods.

Figure 13 demonstrates the substantial capacity benefits of the larger array. At an SNR of 0 dB, all methods achieve approximately 4.6–4.7 bpcu, representing a significant improvement in noise-limited performance compared to the smaller configurations. This reflects the powerful combination of receive diversity (reducing estimation noise) and spatial multiplexing (increasing data rate).

The DL-Enhanced approach maintains its consistent advantage across the entire SNR range, with particularly notable gains in the critical transition region between 2 and 8 dB. The adaptive weighting mechanism of the fusion network becomes increasingly effective as the spatial richness of the channel provides more diverse statistical information for the MLP to exploit. At a high SNR (15 dB), the throughput hierarchy converges near the theoretical maximum, with DL-Enhanced achieving approximately 5.98 bpcu, closely followed by MMSE at 5.96 bpcu and LS at 5.94 bpcu. The perfect CSI bound reaches the full 6.0 bpcu, demonstrating that even with the sophisticated hybrid approach, small residual estimation errors still impose a modest capacity penalty. The results confirm the scalability of the proposed architecture to high-capacity MIMO scenarios. The consistent performance gains across all three MIMO configurations (2 × 2, 4 × 2, 8 × 4) demonstrate that the simplex-constrained fusion and LS-phase anchoring principles retain their effectiveness as the system complexity increases, making the approach suitable for next-generation MIMO deployments requiring both high spectral efficiency and robust channel estimation.

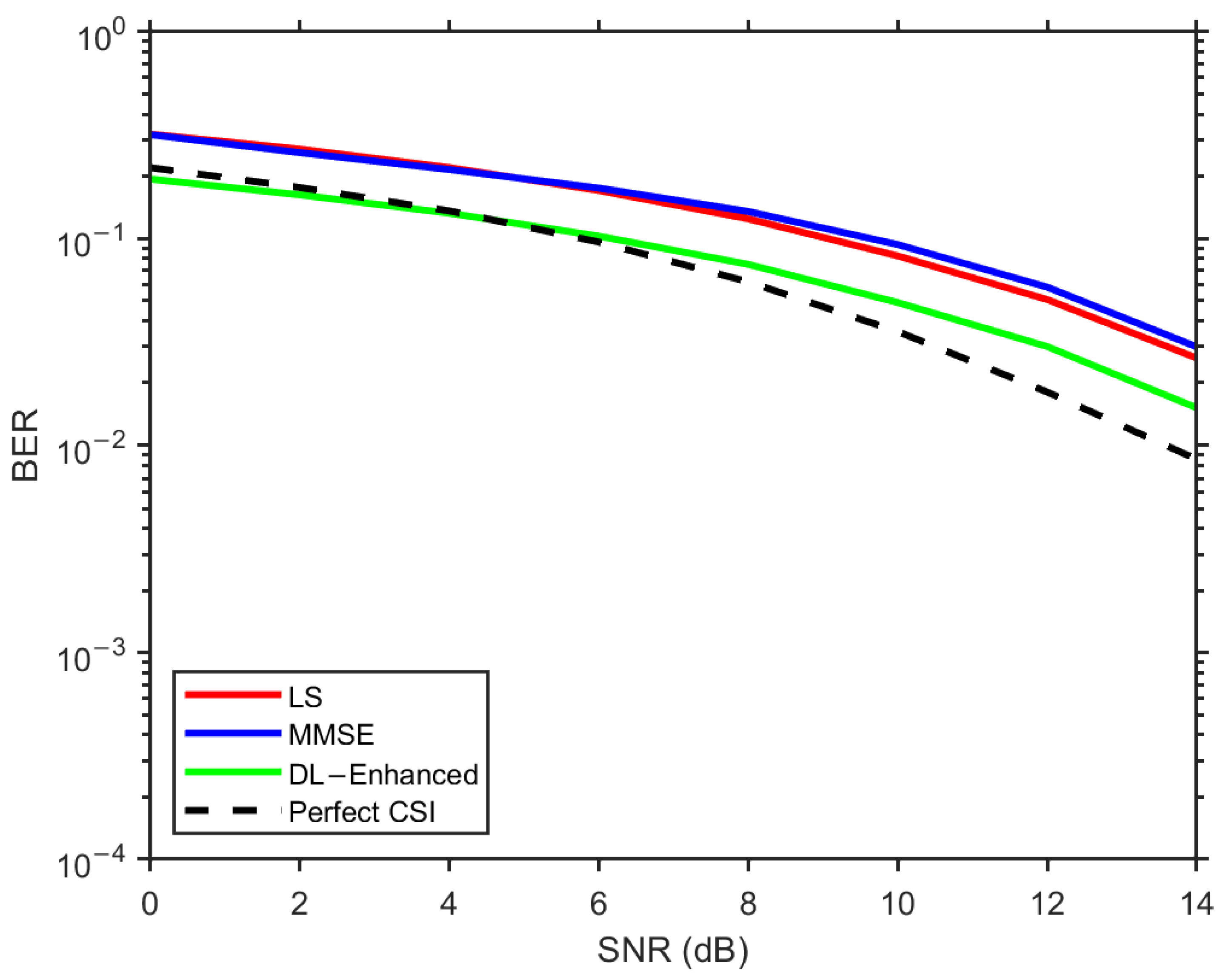

To further assess the impact of phase sensitivity and higher-order constellations, we extended the analysis to 16-QAM while keeping the same pilot pattern and channel models used in the QPSK experiments.

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 show the resulting BER curves for the

and

configurations, respectively. As expected, moving from QPSK to 16-QAM increases the absolute BER level across all estimators, since the smaller decision regions make the detector more vulnerable to both amplitude errors and residual phase rotations. Still, the relative behavior of the estimators remains consistent with the QPSK case.

In

Figure 14, corresponding to the

configuration, LS exhibits the highest BER over the entire SNR range, MMSE provides a clear improvement owing to its use of delay-domain statistics, and the proposed DL-Enhanced estimator yields the best performance among the practical schemes. The gap between DL-Enhanced and MMSE becomes more pronounced at medium-to-high SNRs (around 10–14 dB), where the effect of phase errors is more critical for 16-QAM. In this regime, the magnitude-domain fusion of LS and MMSE, combined with LS-based phase anchoring and a single DD refinement, effectively limits phase sensitivity and prevents additional error floors, allowing the hybrid curve to track the perfect CSI reference more closely.

Figure 15 reports the 16-QAM results for the

configuration. Increasing the number of receive antennas from

to

introduces additional spatial diversity and shifts all curves downward, reducing the BER required to support a given SNR. The ordering of the estimators is again preserved: LS performs worst, MMSE yields a consistent gain, and DL-Enhanced remains the most accurate non-genie estimator. The advantage of the hybrid approach is particularly visible from about 8 dB onwards, where the richer spatial observations accentuate the differences between LS and MMSE and provide more informative features for the fusion MLP. The learned simplex-constrained weights adapt to these conditions, producing a fused estimate whose BER stays closer to the perfect CSI bound while retaining robustness under 16-QAM. Overall, these results confirm that the proposed architecture remains effective and phase-robust when moving to higher-order modulations and when scaling from

to

arrays.

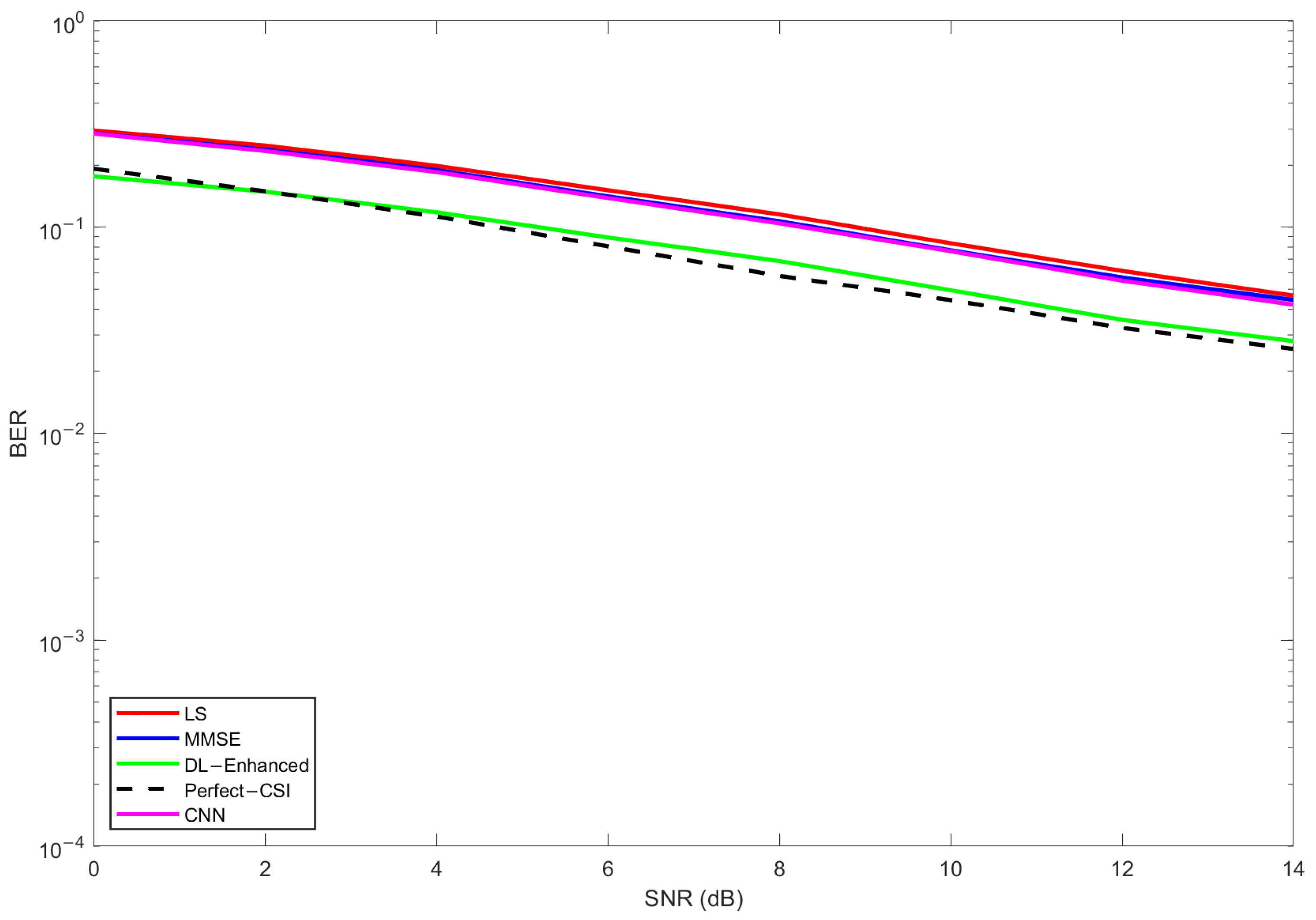

5.1. Comparison with a One-Dimensional CNN Baseline

To contextualize the gains of the proposed hybrid estimator, we include a lightweight 1D-CNN baseline that maps the LS hypothesis to an MMSE-like estimate by processing the

stacks of

with short convolutional blocks and a 1 × 1 head. To avoid phase wrapping, the CNN output is used only in magnitude while the phase is taken from LS, i.e.,

.

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 report BER for the three MIMO configurations, comparing LS (red), MMSE (blue), DL-Enhanced (green), perfect CSI (black dashed), and CNN-1D (magenta).

Across all antenna settings, the CNN-1D curve closely tracks the MMSE reference and consistently lies above the DL-Enhanced estimator. This behavior indicates that the CNN largely behaves as a learned frequency-smoothing operator seeded by LS and therefore inherits the MMSE performance ceiling. In the case, the five curves are tightly grouped at low SNRs since detection is noise-limited, but differences emerge from about 8–10 dB onward. The CNN remains essentially coincident with MMSE, while DL-Enhanced bends earlier toward the perfect CSI slope, producing a visible BER reduction in the 10–14 dB region where reliable decisions allow the single decision-directed pass to act as virtual pilots and where preserving the LS phase prevents the small-phase biases that penalize coherent detection under QPSK.

The results reinforce the same trend under higher receive diversity. Additional observations per subcarrier reduce the absolute BER for all methods, yet the ordering is preserved: LS shows the highest error floor, CNN and MMSE are nearly indistinguishable over the whole sweep, and DL-Enhanced remains the most accurate non-genie estimator. The gap between DL-Enhanced and the CNN/MMSE pair widens in the mid-to-high SNR regime. In this region, the physics-inspired features make the magnitude fusion more decisive, selecting the better hypothesis per realization under a simplex constraint, while the LS-anchored phase keeps the equalizer unbiased as magnitudes become nearly noise-free. The outcome is a curve that approaches the genie bound faster than the CNN baseline without incurring iterative complexity.

In the configuration, spatial richness further suppresses absolute error rates and brings all practical estimators closer to perfect CSI. Even in this favorable regime, the CNN remains essentially locked to the MMSE trajectory, whereas DL-Enhanced continues to be the closest practical curve to the genie bound at all tested SNRs. The residual gap at a high SNR is small and mainly attributable to tiny magnitude mismatches, as phase errors have been effectively neutralized by design. This confirms that the two ingredients of the proposed architecture—convex magnitude fusion and explicit LS-phase preservation with a single decision-directed refinement—scale cleanly with array size and remain beneficial when the operating point is dominated by subtle estimation biases rather than gross noise.

Overall, the CNN-1D baseline is a strong learned smoother that reliably reproduces MMSE-like behavior, but it does not overcome MMSE because it lacks a per-tone convex dominance mechanism and does not couple learning with decision-directed polishing. The hybrid DL-Enhanced estimator combines model-based priors and lightweight learning to reduce magnitude risk relative to either LS or MMSE while guaranteeing phase fidelity, which explains its consistent advantage over both MMSE and the CNN across , , and configuration.

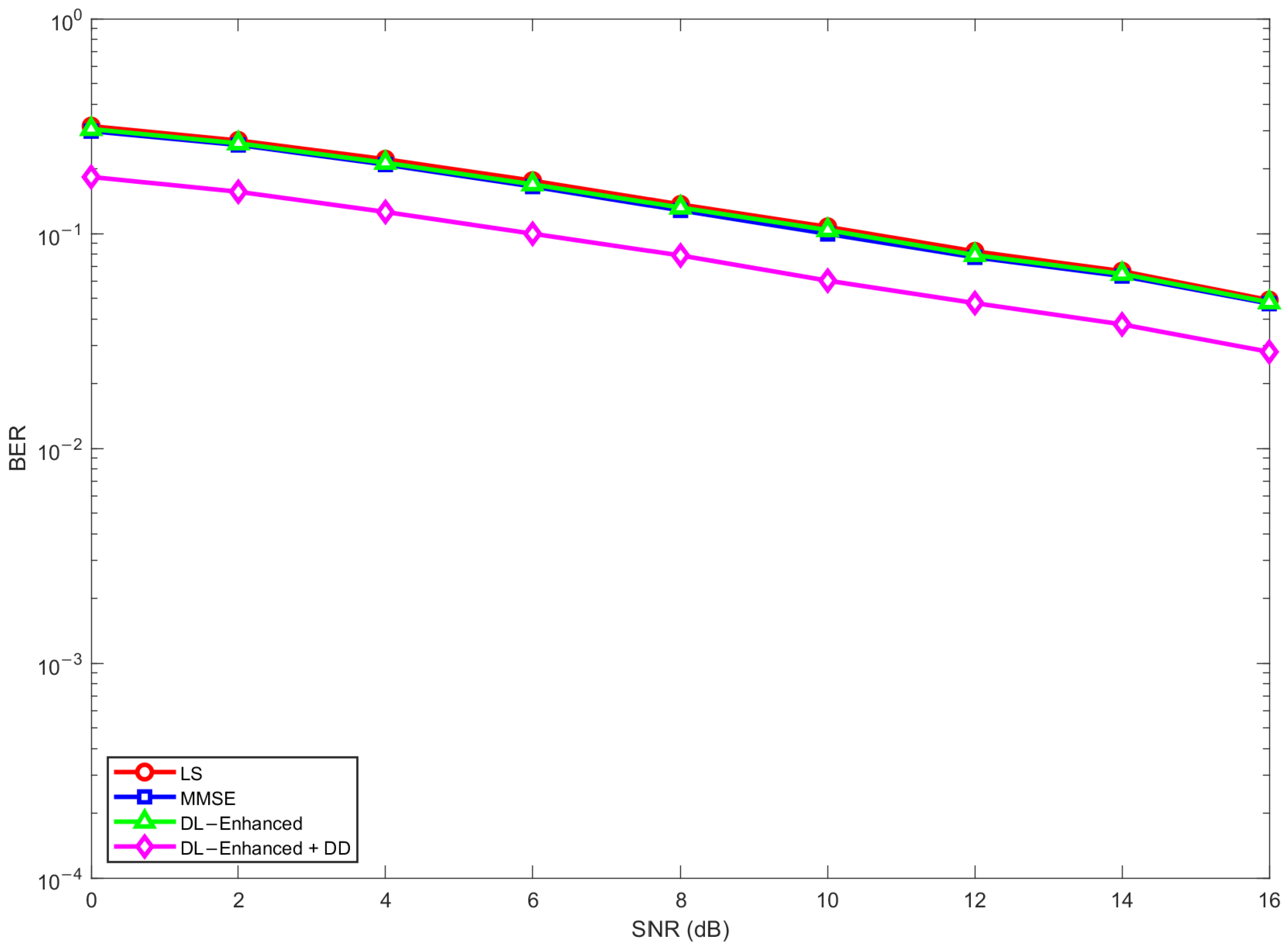

5.2. Complexity, Ablation, and Sensitivity Analysis

Following the implementation used in our simulations, we count complex multiply–accumulate (MAC) operations per OFDM frame with subcarriers and assume a baseband processor and an OFDM symbol duration of . For the main configuration, LS and MMSE channel estimation require about MACs/frame (approximately FLOPs), corresponding to a latency of (about of ). The proposed DL-Enhanced estimator (fusion MLP + LS/MMSE magnitude-domain combination + one decision-directed refinement) requires about MACs/frame (approximately FLOPs), which translates into a latency of , i.e., only about of the OFDM symbol duration.

Similar trends are observed for the larger arrays. For a system, LS/MMSE require approximately MACs/frame, while DL-Enhanced requires approximately MACs/frame (latencies of and , respectively). For an configuration, LS/MMSE require approximately MACs/frame versus approximately MACs/frame for DL-Enhanced, corresponding to latencies of and (about and of , respectively). Overall, the hybrid estimator is about more expensive in MACs than LS/MMSE, but its absolute latency remains well below the OFDM symbol duration for all considered MIMO sizes. In terms of power consumption, the overhead scales roughly linearly with the MAC count, so on modern baseband SoCs with tens to hundreds of GMAC/s capability, the additional energy cost of the hybrid estimator is expected to be modest, a full hardware-in-the-loop characterization is left for future work.

To quantify the contribution of each module, we perform an ablation study for the

QPSK CDL-C scenario, comparing (i) LS, (ii) MMSE, (iii) LS/MMSE fusion without decision-directed refinement (“DL-Enhanced”), and (iv) the full hybrid estimator with one decision-directed iteration (“DL-Enhanced + DD”), see

Figure 19. The fusion-only variant yields BER curves that closely track the MMSE baseline across the SNR range, indicating that the LS/MMSE combination is essentially lossless and provides only a modest gain over MMSE. In contrast, adding the decision-directed refinement produces a consistent BER reduction, typically on the order of 3–4 dB at BER levels between

and

. This confirms that the decision-directed refinement is the main driver of the performance gains of the proposed hybrid estimator.

We also evaluate the robustness of the DL-Enhanced estimator to the SNR and channel-profile mismatch. First, in an SNR hold-out experiment, the fusion network is trained only on alternating SNR points, while evaluation is carried out on the interleaved, unseen SNR values. The resulting BER/NMSE curves remain very close to those obtained when training on the full SNR grid, showing that the learned fusion generalizes smoothly in the SNR. Second, in a cross-profile experiment, the fusion is trained on CDL-C channels and tested zero-shot on CDL-A and CDL-E profiles. Although a small degradation (typically in NMSE and BER) is observed relative to the matched-profile case, the DL-Enhanced estimator still outperforms LS and closely tracks (or slightly improves on) MMSE over the whole SNR range. These ablation and sensitivity results support the necessity of both the fusion and decision-directed blocks and demonstrate that the proposed hybrid architecture is robust to moderate changes in the SNR and channel statistics.