Abstract

Internet of Things (IoT) devices are increasingly deployed in homes and enterprises, yet they face a rising rate of cyberattacks. High-quality Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) is essential for data-driven, deep learning (DL)-based cybersecurity, as structured intelligence enables faster, automated detection. However, many CTI platforms still use unstructured or non-standard formats, hindering integration with ML systems.This study compares CTI from one commercial platform (AlienVault OTX) and public vulnerability databases (NVD’s CVE and CPE) in the IoT/smart home context. We assess their adherence to the Structured Threat Information Expression (STIX) v2.1 standard and the quality and coverage of their intelligence. Using 6.2K IoT-related CTI objects, we conducted syntactic and semantic analyses. Results showed that OTX achieved full STIX compliance. Based on our coverage metric, OTX demonstrated high intelligence completeness, whereas the NVD sources showed partial contextual coverage. IoT threats exhibited an upward trend, with Network as the dominant attack vector and Gain Access as the most common objective. The limited use of STIX-standardized vocabulary reduced machine readability, constraining data-driven applications. Our findings inform the design and selection of CTI feeds for intelligent intrusion detection and automated defense systems.

1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) has rapidly expanded across domains such as automotive, agriculture, healthcare, and home automation. In the smart home context (the home implementation of IoT), myriad smart devices continuously exchange data with their environment. This helps provide conveniences like automated tasks, energy savings, and enhanced security [1]. The adoption of IoT is accelerating; by 2034 the IoT market is projected to reach USD 356.2 billion (up from an expected USD 78 billion in 2025), and the number of IoT connections worldwide is expected to double from 19.8 billion in 2025 to about 40.6 billion by 2034 [2,3]. This explosive growth comes hand in hand with increased security risks. Many smart products reach the market with inadequate built-in security [4]. This introduces vulnerabilities that attackers can exploit to steal data, alter device functionality, or even render devices unusable [5]. In the first half of 2023 alone, there were 77 million IoT attacks, which is a 37% rise over the same period in 2022. In addition, the number of IoT attacks in 2023 was three times that of 2021 [6]. With such a massive and growing attack surface, gathering timely intelligence on emerging threats and appropriate mitigations is of extreme importance for IoT device owners and operators.

Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) refers to relevant information about cyber threats and incidents that helps defenders anticipate and respond to attacks. Enterprise incident response teams (CERTs) rely on CTI platforms and services to obtain actionable insights into the latest IoT vulnerabilities, malware, attack techniques, and indicators of compromise. However, CTI data from different sources often comes in incompatible, unstructured formats, which makes automated processing difficult and slows down response efforts. For example, one study found that organizations struggle to integrate threat feeds because intelligence is largely human-readable and lacks a common structure for machine processing [2]. Standardizing CTI has thus become crucial for efficiency. By being able to share threat information in a structured format, organizations can automate analysis, hence enabling faster defensive actions. Structured Threat Information Expression (STIX) is the de facto standard for structured CTI. It provides a JSON-based schema for representing cyber threat information (attack patterns, threat actors, indicators, etc.) in a machine-readable way. STIX’s widespread adoption by major vendors and platforms reflects its importance in facilitating CTI sharing and interoperability [7]. When CTI is provided in a structured, semantically rich form like STIX, it can directly feed advanced security analytics tools like Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs), including those based on machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) [8]. This enables data-driven cybersecurity systems to leverage up-to-date threat knowledge for improved detection and prediction. For instance, integrating CTI feeds into a DL-based IDS has been shown to help adapt the model to new attacks in real time [8].

Even with existing standards, CTI sources remain inconsistent. Each platform applies its own schema or partial STIX mapping and highlights different aspects of an incident. This fragmentation complicates the fusion of intelligence from multiple feeds, a process that could otherwise enrich the context for decision-making. In practice, security teams often need to consult several CTI platforms (both commercial and open/public sources) to obtain a comprehensive view. Yet, combining these feeds requires significant effort to normalize data formats and semantics. If DL models are to consume CTI from diverse sources, the consistency and quality of that data become critical factors for model accuracy. Low-quality or inconsistently formatted data can lead to garbage-in, garbage-out effects in automated systems [9]. On the other hand, high-quality CTI feeds refers to ones that are structured, complete, and up to date. These feeds can serve as valuable input features or training data for data-driven cybersecurity solutions that rely on Artificial Intelligence (AI), ML, and DL, thus enabling faster threat detection, forecasting, and automated response.

In this work, we carry out an exploratory study to assess how well current CTI platforms cater to the need for structured, high-quality intelligence in the IoT and smart home domain. We specifically examine a widely used commercial CTI platform (AlienVault Open Threat Exchange [OTX]) and the public National Vulnerability Database (NVD) feeds for CVE and CPE entries. For our study, we treat the NVD feeds as an open intelligence source. We focus on IoT/smart home-related threat intelligence from these platforms and evaluate them along two dimensions:

- STIX adherence: Both syntactic (data format/fields) and semantic (use of standard vocabularies) compliance with STIX 2.1;

- Intelligence quality: The richness and actionability of the information (e.g., does it answer key questions about each incident, and what trends or patterns can be observed?).

By highlighting the similarities and differences in how these platforms structure and present IoT threat intelligence, we aim to extend knowledge on the interoperability, quality, and usefulness of such CTI. This comparison is especially relevant as organizations design automated defenses. Understanding the strengths and gaps of each CTI source helps determine which feeds best support data-driven security systems.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically compare both commercial and public CTI sources with a focus on IoT and smart home threats. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- Comparative Analysis of CTI Structure: We evaluate the syntactic and semantic adherence to STIX 2.1 in each platform’s CTI data. Our analysis quantifies what fraction of each platform’s data fields conform to the STIX format and vocabulary versus what portion is platform-specific or unstructured. We also identify common fields across platforms that carry equivalent information, which could be leveraged to interconnect intelligence from different sources.

- Threat Intelligence Quality and Trends: We assess the coverage and completeness of the intelligence provided by each source using the 5W3H framework (Who, What, When, Where, Why, How, How long, and How often). This reveals how well each platform’s reports answer fundamental incident questions. In addition, we analyze the content of the CTI (vulnerability severity metrics and attack vectors) to uncover domain-specific trends. For instance, we show that network-based attacks are predominant in the IoT/smart home domain.

- Implications for ML-Based Security Systems: We discuss how our findings can guide the integration of CTI into intelligent cybersecurity solutions. The observed gaps in standard adherence suggest areas where CTI feeds might require preprocessing or augmentation before feeding into ML models. Conversely, platforms like OTX (with fully STIX-compliant feeds) can provide readily machine-readable intelligence that may streamline data ingestion for automated threat detection. We outline practical considerations for selecting or combining CTI sources to support DL models for intrusion detection, threat hunting, or automated incident response.

Overall, our study provides a clear picture of the current state of CTI interoperability and quality for IoT/smart home threats, and it bridges the CTI research with the needs of emerging data-driven cybersecurity tools. Our goal is to provide insights that benefit both researchers (in developing CTI-enhanced ML/DL-based solutions) and practitioners (in choosing CTI platforms that best fit their security operations).

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the background on IoT threats and STIX. Section 3 reviews related work in the areas of CTI sharing and quality. Section 4 describes our methodology, including data collection and the analysis approach. Section 5 presents the results of our comparative analysis. In Section 6, we discuss the implications of these results and note this study’s limitations. Finally, Section 7 concludes this paper and suggests future work.

2. Background

Like traditional IT systems, IoT devices are susceptible to a wide range of cyberattacks, though some attack vectors differ from those in conventional computing. Prior work by Sasi et al. [5] categorized six main types of attacks on IoT devices:

- Physical attacks: Attacks on the physical hardware layer, usually requiring the adversary to be in close proximity to the device or network. Examples include device tampering and RF (radio-frequency) jamming or spoofing.

- Network attacks: Attacks on the network communication layer. These target weaknesses in network protocols, communication channels, or device connectivity. Examples include traffic interception/analysis and routing attacks.

- Software/Application attacks: Exploits targeting vulnerabilities in the device’s software, firmware, or operating system. This category includes malware infections, authentication bypass, and code injection attacks that compromise the device’s software stack.

- Encryption attacks: Attacks aiming to break or bypass cryptographic measures in IoT systems. Attackers use cryptanalysis to decrypt or spoof encrypted data by taking advantage of weak encryption algorithms.

- Data attacks: Attacks focusing on the data within IoT systems, violating the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of that data. Examples are data tampering and device impersonation to feed false data into the system.

- Side-channel attacks: Techniques that exploit indirect information leakage from IoT devices (such as power consumption) to extract sensitive information like encryption keys.

Recent industry reports highlight how prevalent and diverse IoT attacks have become. In a 2022 report, Bitdefender found that most IoT attacks aimed at denial of service (84%), followed by data theft (11%) and direct device exploitation (2%) [10]. Separately, Kaspersky’s analysis for 2023 noted that exploiting vulnerabilities in network services and brute-forcing weak passwords were the two main attack vectors observed in IoT environments [11]. The volume of attacks is increasing steeply, with over 77 million IoT attacks observed in the first half of 2023, a 37% rise compared to the first half of 2022 [6]. Between 2021 and 2023, the number of IoT attacks reportedly tripled [6], underscoring the growing risk as IoT adoption expands.

With such a broad attack surface and high stakes, organizations are investing heavily in cybersecurity solutions tailored to IoT. The CTI market is forecast to expand from USD 4.9 billion in 2023 to USD 24.9 billion by 2032—nearly a five-fold rise within a decade. [12]. This reflects increasing executive awareness that timely, actionable CTI is crucial for business continuity in the face of cyber threats. However, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for IoT security, as each organization has different risk profiles and resources. Companies often end up using a combination of commercial security products and in-house tools to meet their specific needs [12]. A corporate security team might integrate multiple CTI feeds and tools to build a comprehensive view of threats relevant to their environment. For instance, a team may combine a commercial threat feed (providing curated intelligence) with open-source or community feeds (offering additional indicators) and internal telemetry. To successfully integrate these diverse sources, it is essential that the data is standardized and interoperable across systems. A common practice is to rely on structured formats like STIX for CTI data sharing, which allows custom tools and different vendor products to “speak the same language.” Using standardized CTI from multiple sources enables correlation of threat data and supports automated pipelines that aggregate intelligence on emerging attacks.

As IoT attacks grow, rapidly identifying attackers’ tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) becomes crucial for defense. CTI that characterizes these TTPs can enable organizations to deploy proactive measures (e.g., updated detection signatures, patched vulnerabilities, and tightened access controls) before an attack hits or as soon as indicators emerge. In this context, our study examines whether current CTI platforms provide the necessary structured, high-quality data to support such proactive defense mechanisms. We specifically aim to measure the practical utility of both commercial and public CTI solutions by exploring their reporting in the context of IoT/smart homes. The goal is to understand to what extent these platforms can be leveraged (in their current form) by security teams and AI/ML/DL-driven tools to enhance protection of IoT devices.

STIX

STIX is a standardized language and serialization format for CTI, initially developed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in 2012 [13] and now maintained by OASIS’s CTI Technical Committee [7]. STIX provides a common schema for representing threat information so that it can be easily shared, stored, and automatically analyzed. In STIX 2.1 (the version used in this study), threat information is organized into the following:

- STIX Domain Objects (SDOs): These are 18 types of objects, such as threat actor, attack pattern, indicator, and vulnerability;

- STIX Relationship Objects (SROs), which link domain objects (e.g., an indicator “indicates” a malware or an Attack Pattern “uses” a particular Malware).

STIX objects are represented in JSON format, where each object has a type and a set of standardized fields (properties). For example, an indicator object might have properties like name, description, valid_from (date), etc., as defined by the STIX specification. STIX 2.1 defines a core set of common properties (applicable to multiple SDOs) as well as specific required or optional fields for each SDO. Many leading CTI platforms support STIX, including (but not limited to) ThreatConnect, Anomali ThreatStream, Palo Alto Networks AutoFocus, EclecticIQ, IBM X-Force, and AlienVault OTX, which all utilize STIX to some degree in their products or data feeds [14,15,16,17]. The advantage of STIX adoption is that it promotes interoperability. A security analyst can ingest STIX reports from different sources into a single system, and automated tools can parse those reports knowing that they follow a standardized structure.

3. Related Work

The proliferation of CTI services and platforms has been documented in prior research. Ring [18] observed that many well-known security vendors (Symantec, FireEye, Kaspersky, etc.) offer real-time threat intelligence feeds to their customers, yet users often question the effectiveness of these products and complain that feeds become outdated quickly. In Ponemon’s Threat Intelligence survey [19], 78% of respondents rated their threat intelligence tools’ usefulness in the lower tiers (1–6 on a 10-point scale), while only 22% gave them a high rating (7–10). This suggests a significant gap between the availability of CTI services and their perceived value to organizations. In this sense, Ring [18] highlights a cultural challenge in which security professionals acknowledge the critical importance of sharing intelligence, but there is a lack of routine information sharing even internally within organizations. Both Ring and the Ponemon Institute argue for establishing a nationwide platform where businesses can share threat intelligence in real time, irrespective of their size or resources, for mutual benefit. These findings underline a core issue in CTI: simply having feeds is not enough. The intelligence must be relevant, timely, and easily shareable to be actionable.

Sauerwein et al. [20] examined 22 CTI platforms and noted that most are closed-source and focus primarily on providing indicators of compromise (IoCs). Their analysis found an absence of a common definition or data structure among threat-sharing platforms. Each platform tended to use its own format for representing intelligence. Nevertheless, certain standards emerged as popular choices; STIX was the most commonly supported format (compared to alternatives like OpenIOC or IODEF) [20]. The lack of uniform structure across platforms means that consuming intelligence from multiple sources often requires custom translators for each source. This reinforces the importance of efforts to standardize CTI representation, a theme central to our study.

In a white paper, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) outlines several key challenges in CTI [21]. First, no single organization (public or private) can collect all relevant cyber data on its own; partnerships and intelligence sharing are essential. Also, turning raw data into true “intelligence” requires processing steps that ensure data is interoperable, contextualized, and actionable. In other words, CTI should not just be a raw feed of IoCs, but also be enriched with context and standardized so that various stakeholders can easily utilize it and made actionable to help inform decision-making.

Tounsi and Rais [22] discuss the overwhelming volume of threat data that modern CTI vendors collect (up to a million/day) and note that quantity often overtakes quality. With such high volumes, it becomes impossible for human analysts to validate or richly annotate every threat datum. Two major challenges arise: (1) timeliness, which requires intelligence to be shared quickly, especially for zero-day threats, and (2) the limited value of quickly sharing simple IoCs for targeted attacks. Attackers carrying out targeted or APT-style attacks might use a unique indicator (like a one-off domain or hash) that, once shared, is of little use because it will not be reused. Thus, organizations need to focus on CTI relevant to their environment instead of having big data feeds of IoCs. CERTs must filter CTI feeds for relevance to their own likely threats and vulnerabilities, rather than chasing every alert.

In terms of CTI data quality, Schlette et al. [23] proposed a set of quantitative metrics to evaluate CTI quality. Using STIX 2 as the reference model, they define metrics at the (a) attribute, (b) object, and (c) report levels. While some metrics can be computed automatically, others may require expert judgement. The authors interestingly note that presenting these quality metrics visually can help analysts understand why a piece of intelligence scored as it did. Visualization could break down which aspects of a report are strong or weak, guiding trust in the CTI. While our study does not directly measure “quality scores”, it resonates with this work by examining aspects like completeness and standard compliance, which can be seen as components of quality.

With regard to completeness, De Melo e Silva et al. [24] proposed a comprehensive evaluation methodology for analyzing CTI standards and platforms, addressing the lack of consistency and interoperability across the CTI ecosystem. The authors used a systematic selection strategy and a multi-criteria framework based on the intelligence cycle and 5W3H dimensions. The authors assessed major CTI standards (STIX/TAXII, IODEF/RID, and OpenIOC) and open-source platforms (MISP, OpenCTI, CRITs, CIF, and Anomali STAXX), ranking them by usability, integration capability, and architectural completeness. Their results indicate that STIX/TAXII are the most holistic and interoperable standards, while MISP and OpenCTI stand out as the most comprehensive and flexible open-source platforms for threat information sharing and correlation. They conclude that no platform covers all CTI processes and stress the need to consolidate standards and integrate platforms for actionable defense. We leverage their 5W3H approach (see Section 4.3.1 for details) to study the completeness of our collection of CTI data objects.

Interoperability has been addressed in a broader sense by Rantos et al. [25], who proposed a four-layer interoperability model, (1) legal, (2) policy and procedures, (3) semantic and syntactic, and (4) technical, to tackle the various barriers to CTI exchange. The authors found that handling of intelligence is extremely diverse across their 32 studied sources and that overall CTI interoperability is limited in practice, which negatively impacts the actionability of intelligence. They advocate holistic solutions that address not just data formats, but also legal and procedural hurdles to sharing. Our work sits mainly in the semantic and syntactic layer; we investigate how semantic and syntactic differences between CTI sources limit or enable their integration. Also, we provide empirical evidence of the semantic/syntactic disparities by directly comparing data from multiple platforms against STIX, as we show in the following sections.

Our work relates that of Ramsdale et al. [26], who investigated the generation of defensive measures from CTI, particularly focusing on IoCs. They describe how organizations use internal sources (like system logs) and external sources (news feeds, dark web monitoring, and community-based IoCs) to build blocklists and detection rules (for firewalls, IDSs, etc.). A limitation noted in their study is that much external intelligence is shared in human-oriented formats rather than structured, machine-readable forms. This makes it necessary to use Natural Language Processing (NLP) and AI techniques for structured intelligence generation. Although industry and the community support STIX, implementation remains weak. Many feeds share rich data in simple lists or reports (IP addresses, hashes, etc.) rather than machine-readable STIX format. Their results showed that STIX fields were underutilized even when STIX could have represented that information. Our work adds a new perspective by examining data from specific popular CTI platforms (including one that generates STIX reports) and focusing on IoT threats. We empirically assess the extent of STIX usage and underutilization in these platforms’ data, as well as how the content could support building defensive measures.

Regarding how applying ML and AI to CTI can be leveraged to create actionable solutions, Lin et al. [8] introduced DICI (Dynamic Intrusion Detection System with CTI Integrated), a framework that enhances ML-based IDSs through continuous integration of CTI. The framework uses a CTI Transfer Model to convert structured CTI (e.g., VirusTotal) into labeled data for dynamic IDS re-training. By combining supervised and unsupervised ML, DICI adapts to new and evolving threats in near real time. Experimental results showed that incorporating CTI improved the IDS’s detection performance, increasing the F1-score by 9.3% and recall by 15.95%, while remaining computationally efficient. In this paper, we address the quality of input intelligence data to IDSs with a focus on IoT/smart home CTI. Thus, through our work, we demonstrate how automatically updated CTI data-driven models can inform IDSs. This in turn, helps make IDSs more adaptive and resilient to emerging attack behaviors.

4. Methodology

We describe our approach to collecting and analyzing CTI data from the selected platforms. Figure 1 provides an overview of the data collection process and the preliminary analysis steps. Our methodology consists of the following:

Figure 1.

Data collection and preliminary analysis.

- Data Collection: Gathering IoT-related threat intelligence data from each platform in a structured format (STIX 2.1 where available).

- Preliminary Analysis: Manually inspecting and transforming the raw data to understand its structure, which will then inform the detailed analysis plan.

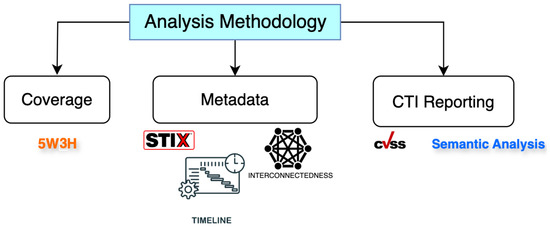

- Detailed Analysis: Evaluating the data along specific dimensions. These dimensions are (a) coverage of intelligence, (b) metadata structure (including STIX compliance and cross-platform field mapping), and (c) the content of threat intelligence reports. Figure 2 illustrates the phases of this analysis pipeline.

Figure 2. The analysis methodology phases.

Figure 2. The analysis methodology phases.

4.1. Data Collection

Our study focused on 3 CTI sources: a commercial CTI platform and 2 open/public databases.

4.1.1. Selection of Platforms

We selected AlienVault OTX (herafter, OTX) as the commercial platform because it is a large-scale CTI service that offers free access options and explicitly supports STIX 2.1 data export. OTX is a community-driven platform with over 200,000 participants sharing threat intelligence pulses. These pulses encapsulate a summary of a threat along with IoCs associated with that threat. OTX’s popularity and its daily generation of around 20 million threat indicators make it a rich source of community-sourced CTI data. This platform represents state-of-the-art commercial CTI offerings and, importantly, allows users to obtain threat data objects in a STIX-based structured JSON format, which is ideal for our analysis of standard adherence. For simplicity, we refer to this platform as the commercial platform in the remainder of this paper. We initially selected IBM’s X-Force as a second platform to analyze. However, after inspecting the resulting data objects from our queries (see Section 4.1.2), we found that they did not address the IoT/smart home scope and thus were discarded. As for other commercial platforms mentioned in Section 2, e.g., Anoamli ThreatStream, they did not offer a free option. Thus, we were not able to use them in the scope of this work.

As public CTI sources, we included the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) feeds for Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs) and Common Platform Enumeration (CPE). NVD is a U.S. government repository that provides a standardized catalog of vulnerabilities (CVE entries) and a dictionary of product identifiers (CPE). We consider NVD as a CTI source since it provides enriched information on vulnerabilities (for instance, CVEs include descriptions, severity scores, references, etc.) which is valuable threat intelligence for defenders. Both CVE and CPE data are freely accessible via an API. Including CVE/CPE gives a contrast between commercially oriented intelligence (OTX) and publicly maintained vulnerability data (NVD). For simplicity, we will refer to the CVE and CPE feeds together as our public platforms throughout the rest of this paper.

4.1.2. Data Collection Method

For OTX, we retrieved data through its web interface using relevant keywords. Specifically, we queried the platform for the terms iot and smart home, which are likely to surface intelligence reports related to IoT devices or smart home contexts. We performed searches in the community portal for these terms and downloaded the resulting STIX 2.1 JSON files for the matching pulses. Using keyword searches inevitably introduces some noise (e.g., a generic string like iot could match content in an unrelated context or appear as part of another word). Thus, we chose smart home specifically to improve precision, as it is a distinct phrase unlikely to appear unless the content truly relates to smart home devices. Moreover, many IoT products used in enterprises (smart cameras, connected sensors, etc.) also appear in home contexts, so “Smart Home” intelligence overlaps with general IoT security. While it was not feasible to manually review every retrieved object, we visually inspected a random sample of entries to confirm explicit IoT or smart home context. This spot-check process’s objective is to minimize false matches and ensure that the final dataset aligns with the intended research scope.

For the NVD data, we utilized the official NVD REST API to fetch CVE and CPE entries. We constrained our query by using the same keywords within the NVD feeds as well to mirror the focus on IoT-related data. The NVD API returns JSON data. We note that NVD’s JSON data objects for CVEs and CPEs are not in STIX format, but rather have their own structured schemas. However, NVD data is enriched. For example, CVE entries from NVD include CVSS severity scores and other metadata that are not present in the basic MITRE CVE dictionary. Regarding CPE, its entries provide a structured naming scheme for products, which can be linked to CVEs to identify what products are affected by which vulnerabilities. To minimize noise for the collected entries, we applied the same approach as in the case of the commercial platform.

We conducted the data collection in two phases to capture a broad set of intelligence over time. An initial collection was conducted in July 2022 and an updated collection was performed in April 2023. In total, we collected 6206 unique data objects from the 3 sources. Table 1 summarizes the number of CTI objects obtained from each platform and their types. Notably, the OTX pulses are all considered a single class. The table shows that OTX contributed 1180 pulses (19%) and NVD provided 3776 CVE entries (60.8%) and 1250 CPE entries (20.1%). This distribution reflects how much relevant IoT intelligence each source had available via our search criteria. For instance, the large number of CVEs suggests that many vulnerabilities in IoT or smart home products have been catalogued. In contrast, OTX’s count is smaller, potentially because community tagging with “IoT” or “Smart Home” might be less common or more selective. Overall, our dataset provides a substantial basis to compare the content and format of CTI from commercial vs. public sources.

Table 1.

Obtained CTI objects from each platform using keywords “IoT” and “Smart Home”.

4.2. Preliminary Analysis

Once the data was collected, we proceeded with carrying out an exploratory visually based manual analysis. This involved converting the JSON structure to MS Excel sheet format for better visualization. Wherever any nested fields were found, we flattened them. The total number of fields in OTX objects is 19, in CPE is 11, and in CVE is 60 consecutively. Visual inspection of object types and structures helped us understand the dataset and define the next analysis steps.

4.3. Detailed Analysis

After the preliminary exploration, we defined a structured methodology to analyze the CTI data in depth. Our scripts parsed each object to support three analyses: coverage, metadata/STIX structure, and CTI content. Figure 2 illustrates the detailed analysis pipeline.

4.3.1. Coverage of Intelligence

We evaluate how complete and contextual the information in each data object type is. Using the 5W3H framework as defined by Melo e Silva et al. [24] (see Table 2), we checked which of these fundamental questions each object type could answer by manually analyzing its fields. This gives a sense of how useful or actionable an intelligence data object is (an object that answers most of these questions is considered high-utility). We propose a simple scoring scheme to rate the utility of each object type based on the number of 5W3H questions answered. This approach was inspired by the Ponemon Institute’s work, which discussed the quality of threat intelligence [19], and by Schlette et al.’s, which used visualization as a quick evaluation approach for threat intelligence [23]. Our suggested scoring scheme addresses the intelligence quality directly; a higher score means the CTI provides a more complete picture of the incident or threat described. We applied this analysis to each data object type shown in Table 1. We consider an object as having high utility if it answers 6–8 questions, medium if 3–5, and low if fewer than 3. We note that in our proposed scoring scheme, all the 5W3H questions have the same weight of 1. Studying the weight of each of the 8 questions is beyond the scope of this study and thus we leave it for future work.

Table 2.

The 5W3H method. Table from [24].

4.3.2. Metadata and STIX Structure Analysis

We study the fields present in the CTI objects from the OTX platform to assess the adherence to the STIX 2.1 format. This involves identifying which fields in each object type are standard STIX fields and which are custom/non-STIX fields. Within the STIX fields, we further distinguish common properties (fields that are common to all SDO types) and SDO-specific properties. Moreover, we check how many of those STIX fields are required vs. optional within the SDO type as defined by STIX. By doing this, we gauge each platform’s syntactic alignment with the standard. In addition, for the commercial platform, we measure the distribution of its data objects based on the 18 STIX SDO types as already highlighted in Section 2.

Additionally, to explore interoperability and interconnectedness among the platforms, we look at equivalent or similar fields across platforms. For instance, if OTX and CVE both have a field for the label, those are equivalent fields carrying the same type of information. On the other hand, if the content of the field is generally the same but has a different format, we denote the fields as similar. We compile a mapping of such overlapping fields and note where values could be directly matched or correlated between different sources. This cross-platform field analysis reveals how easily one could join or integrate data from the platforms.

4.3.3. CTI Content Analysis

Beyond structural considerations, we analyze the actual content of the threat intelligence objects that are focused on IoT/smart homes. This includes two sub-analyses:

- Vulnerability and Attack Pattern Analysis: Using NVD CVE entries, we examine the distribution of attack vectors and how it relates to the attack severity. This helps identify the predominant attack vectors in IoT vulnerabilities and whether network-based issues tend to be rated more severe.

- Semantic Analysis of Threat Descriptions: We scan the free-text fields of the commercial platform for the presence of standard threat keywords. The objective is to see to what extent the content of reports uses common threat terminology that could be leveraged by NLP for automated classification. If a platform extensively uses standardized terms in descriptions, this could be very useful for ML models to parse those descriptions. We specifically look for keywords from STIX’s open vocabulary (https://docs.oasis-open.org/cti/stix/v2.1/csprd02/stix-v2.1-csprd02.pdf, accessed on 17 November, 2025) and count their frequency. This semantic check complements the structural analysis by checking if the intelligence is not just structurally standardized, but also speaking a “common language” of threats. Further analysis of how NLP techniques can be leveraged to enrich CTI objects is beyond the scope of this paper and is thus left for future work.

5. Results

In this section, we highlight the findings from our detailed analysis of the CTI data, as described in Section 4.

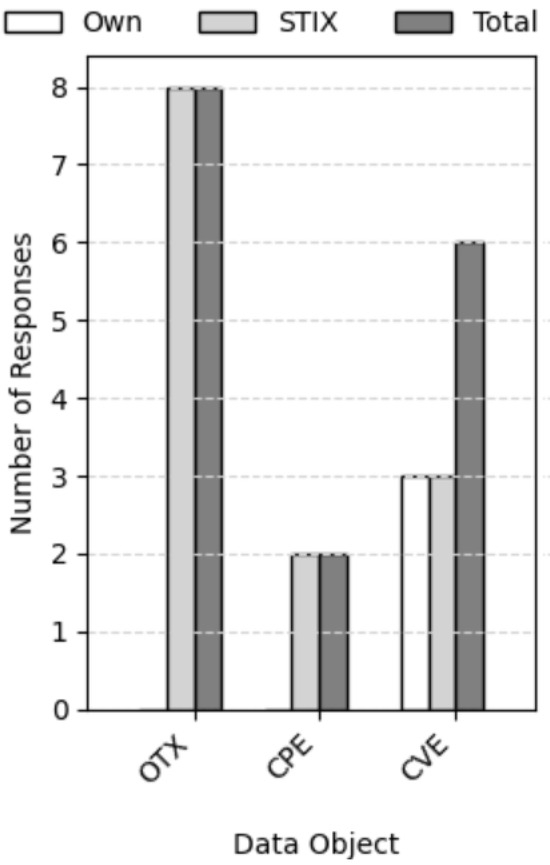

5.1. Intelligence Coverage Analysis

Using manual inspection of the fields of each data object, this step involves answering the questions proposed by the 5W3H method for each of the data object types referred to in Table 1. Figure 3 provides an overview of the coverage results and the percentage of STIX 2.1 fields used in coverage for each data object type.

Figure 3.

Replies obtained after manually analyzing data object classes from the commercial platform OTX and public platforms CVE and CPE.

5.1.1. Commercial Platform

We found that OTX pulses provide very comprehensive intelligence. All of the eight questions were answerable for OTX pulses, yielding a high utility score according to our criteria. Moreover, OTX uses only STIX 2.1 fields to convey this information, which means that the relevant details are in structured fields. This shows that OTX pulses present a complete and well-structured picture of an incident, which is ideal for feeding an automated system.

5.1.2. Public Platforms

With regard to the public platforms, we carried out the same coverage analysis. For CVE objects, we found that they had high utility, as we were able to obtain a total of six responses, three of which were from STIX 2.1 fields. Neither the WHO nor the HOW LONG questions were answered. In CPE objects’ case, they only contained two responses (for the WHEN and WHAT questions), thus indicating low utility. Both response were obtained from STIX 2.1-based fields. Hence, data objects from two out of the three platforms demonstrated high utility, while one showed low utility.

5.2. Analyzing Metadata of Data Objects

In this part, we measure how well the data object types from our set of platforms adhere to the STIX structure and how their fields compare and connect across sources.

5.2.1. Adherence to STIX 2.1 Structure

We examined commercial objects from OTX to measure how many fields follow the STIX 2.1 standard versus custom platform fields. We found that all OTX fields adhere to the STIX 2.1 structure.

- Comm.: Of the STIX fields that are in the data object type, we measure the percentage of fields that fall under the “common properties” as defined by the STIX 2.1 structure.

- Required: For the fields that are adopted from the STIX 2.1 structure, we determine the percentage of required fields as per the STIX standard.

- Optional: Similar to the “Required” column, for the fields that are adopted from the STIX 2.1 structure, we measure the percentage of optional fields as per the STIX standard. Both optional and required complement each other, and thus the sum of both in any given row will always be 100.

In addition, for full adherence, we found that about 42% are common properties and 58% are object-specific. With regard to required vs. optional, values were very close, with each of the designations having roughly half of the fields (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of STIX 2.1 fields and use of common, required, and optional STIX 2.1 fields in AlienVault OTX data objects.

We did not run this experiment for the CVE and CPE data types because, as noted in Section 4, NVD’s schema is not STIX but rather a different JSON format altogether. Instead, we handle CVE/CPE by focusing on content overlap demonstrated through interconnectedness among platforms’ data object types, as shown later.

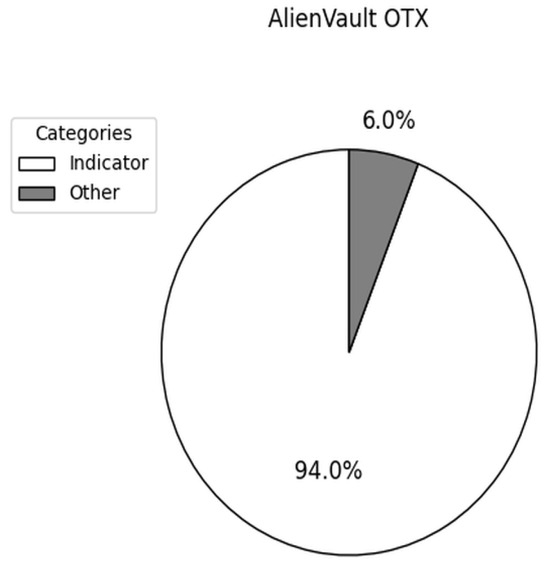

5.2.2. Distribution of Classes of Data Objects in the Commercial Platform

Based on information extracted from the data objects, we measured the distribution of STIX SDO types of the data objects that we obtained from OTX. As shown in Figure 4, we found that the majority of data objects are concentrated in one SDO type for OTX, with 94% being of type indicator.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the types of data objects in AlienVault OTX.

5.2.3. Timeline of IoT and Smart Home Threat Intelligence

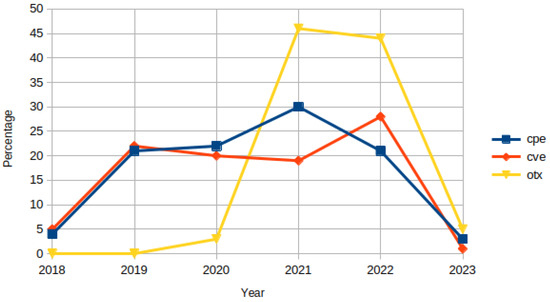

Commercial Platform. In our analysis of OTX data objects, using data from the created field, we found that 46.6% and 44.8% of objects were created in 2022 and 2021, respectively. Figure 5 shows how data objects are distributed between 2018 and 2023 for the different platforms (commercial and public).

Figure 5.

Distribution of data objects for the 3 platforms between the years 2018 and 2023.

Public Platforms. We found that the year with most CVEs published was 2022, with a total of 28.4% of the data objects. With regard to CPE, after analyzing the modification date-based field, titled cpes.lastModifiedDate, we found that 30.4% of the data objects were from 2021 and 20.7% from 2022. In addition, the number of data objects modified in years 2019, 2020, and 2022 are very close. Also, we note that while other platforms provide date fields related to the creation/publishing of the data objects, CPE only offers a field related to the modification date, as we demonstrate later in Section 5.2.4.

In general, for the three platforms, there is an increasing trend of reported incidents between 2018 and 2022 (where we have data objects from the full years), which is logical given the increasing adoption of IoT. Please refer to Figure 5 for details on the distribution of objects/year and platform.

5.2.4. Interconnectedness Between Fields Across Platforms

To identify interconnectedness, we examined the fields in each data object type in our set of platforms. We were able to identify several fields that carried equivalent (identical in format) or similar information (providing the same information in a slightly different format). We present the mappings of these fields in Table 4, where the fields that are identical in format are denominated as equivalent (equiv.) and those that provide the same information but in different format are denoted as similar. We found mappings that covered object types across two and three fields.For instance, OTX and CVE shared the labels and data description fields. Regarding fields that were found across all the platforms, these included last modified date and data type.

Table 4.

Similarity between fields of the platforms. Classif indicates whether the fields have a similar (similar) notion or are exactly the same (equiv.). The CVE fields are dot-separated to indicate the nested nature of the fields.

5.3. Analyzing CTI Reporting

In this section, we highlight our main findings from analyzing the contents of our collection of data objects. This covers both the vulnerabilities and the text within the objects.

5.3.1. Vulnerability Analysis in IoT and Smart Home Devices

We analyzed the fields that represented CVSS v3.0/3.1 and CVSS v2.0 within the CVE data objects. We found that of the 3776 objects, 3629 (96.1%) contained CVSS v3.0 data and 3398 (90%) had CVSS v2.0 data. Our results show that network-based vulnerabilities are dominant. More than 60% of the IoT CVE objects had their attack vector field as Network. This refers to a vulnerability that can be exploited remotely across a network, which is typical for IoT devices that are often accessible over Wi-Fi or the Internet. Moreover, we found that for these same data objects, the CVSS v3 severity score was high or critical in over 90%, and the CVSS v2 severity score was high in over 65%. This suggests that whenever the attack vector is through the network, it is most likely to be a severe attack. The details are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Analysis of severity degrees of attack vectors in CVE objects. ATK VEC. refers to the attack vector, ADJ_NET. stands for ADJACENT_NETWORK, LOC. means LOCAL, NET. indicates NETWORK, and PHY is for PHYSICAL. The two % columns represent the percentage of reports with CVSS v3 and CVSS v2 data, respectively.

For CPE objects, we examined the cpes.cpe23Uri field to identify the causes for which the data objects were created. We found that applications were the leading cause in 57.2%, operating systems in 39.4% and, hardware in 13.4% of cases.

5.3.2. Semantic Analysis of Commercial Platform Fields for STIX 2.1 Keywords

We have already reported the results of adherence to STIX 2.1’s structure in Section 5.2.1; we further carried out a semantic analysis of the commercial platform fields using TTP keyphrases extracted from STIX properties that use the STIX open/suggested vocabulary. This analysis helps identify the level of usage of a set of STIX 2.1 vocabulary that we believe to be the most relevant. The STIX properties from which we extracted the keywords are as follows:

- malware_type;

- indicator_type;

- malware_result_type;

- infrastructure_type;

- report_type;

- malware_capabilities;

- grouping;

- tool_type.

STIX open vocabulary uses the “-” character to separate words, e.g., denial-of-service. We extend this list of expressions by using natural language separation (the space character), e.g., denial of service instead of denial-of-service. We searched for the keyword list in the fields designated name and description in data objects from OTX. Our results, provided in Table 6, show that for keyphrases (with more than word), i.e., involving a separation character, the natural language separation character (space) is more commonly used compared to hyphen separation. Notably, of the 58 expressions that we searched for, 20 (34%) were not found in the list. Additionally, the expressions in the malware_capabilities category returned no results.

Table 6.

Number of STIX open-vocabulary entries with name- and description-based fields in OTX. Grey cells indicate that a space character replaced the dash character. web shell is the only case where a space was added in the middle of the keyword compared to the original webshell.

6. Discussion

Based on the analysis presented above, we discuss the implications of these findings for both CTI practice and the integration of CTI with advanced cybersecurity systems (particularly those using ML/DL). We also address the limitations of our study.

6.1. Quality of CTI Data and Implications for ML/DL Systems

Our results demonstrate that the quality and format of CTI data vary significantly across sources, directly affecting their use in ML/DL models. On one hand, OTX pulses stood out for their complete adherence to STIX’s structured format and high information coverage. For an organization developing a DL-based threat detection system, OTX provides a feed that is both rich in context and readily machine-readable. Integrating OTX data into a data pipeline would involve minimal preprocessing, giving it a clear advantage when building automated systems. Moreover, because OTX answers all the 5W3H questions, it could supply a model with comprehensive features regarding each threat incident, potentially improving the model’s situational awareness and accuracy. If OTX pulses were to have high semantic content (not the case as shown in Section 5.3.2), a DL model would be able to learn correlations between certain IoCs and attack contexts if fed enough pulses.

With regard to the NVD public platforms, they are highly valuable for vulnerabilities but also highlight a limitation. For CVE, by itself, its data are structured and standardized (in the CVE schema) but not in STIX, and it does not directly link to threats (only vulnerabilities). However, for ML-based risk assessment, the CVE feed gives hard, verifiable data (CVE IDs and severity scores) that could serve as labels or features. For instance, it is possible to train a model that predicts whether a new IoT vulnerability will be exploited in the wild using features from CVE (like presence of network attack vector with high severity) combined with threat feed data. Through analyzing CVE objects, our results confirmed that network-based, high-severity vulnerabilities are common; a model could likely learn that pattern as indicative of urgent threats.

6.2. Interoperability, Correlation, and Data Fusion

We found multiple overlapping fields that act as common touchpoints between platforms. For practitioners, this is a positive sign, as it means integrating feeds is not an impossible task. In practical terms, a security engineer can correlate information using filters. For instance, they could connect all objects within a creation date range that include a certain keyword, thereby enriching each vulnerability record with both context (OTX) and risk analysis (NVD CVE). Such a technique would require the use of NLP to ensure the existence of a relation between the objects from the different sources. This kind of data fusion can also benefit ML models in which an algorithm could take features from both sources. A knowledge graph or unified database of IoT threats could then be constructed where nodes from different sources link via these common fields. A unified view provides security engineers with the capacity to build situational awareness using tools like OpenCTI [27]. Also, unified views enable advanced analytics, such as graph-based ML, to uncover hidden patterns in isolated feeds. However, our findings highlight the challenges in interoperability and correlation. The lack of complete STIX standard use (especially semantically) means that automated correlation is not straightforward in all cases and that NLP is critical for building such a system. Structured data must use standardized vocabularies to achieve real interoperability. Current CTI platforms have room to improve on this front, and the community (e.g., OASIS) and national cybersecurity bodies may need to push not just the format but also the usage of common IDs and terms to guarantee that organizations—regardless of their size—are able to protect their infrastructure. For now, organizations aiming to integrate CTI sources should be prepared to use text analysis or mapping tables for common threat keywords and names, in addition to structured field matching. This is an area where research from the NLP domain can help, as noted by Ramsdale et al. [26], effectively bridging the gap by extracting key expressions from text where structured links are missing.

6.3. Actionability and Timeliness

One of the motivations of CTI is to enable timely action. Our analysis of the timeline of IoT intelligence (Figure 5) showed that OTX and CVE had most of their IoT threat content in recent years (2021–2022 primarily), reflecting that these platforms are actively reporting current threats. This shows that if we were to feed an ML model with this data, it would mostly reflect the recent threat landscape, thus making it more likely for training models to detect present-day attack patterns. Indeed, Lin et al. [8] showed how integrating CTI with IDSs can offer better protection through their CTI-based IDS system.

The notable difference in data volume between OTX and CVE implies that community-driven reporting on IoT threats may still lag behind the actual attack surface or that our keyword-based retrieval did not capture all relevant records. In either case, relying on a single feed risks blind spots. Combining heterogeneous CTI sources is therefore essential for completeness and operational value. In this context, CVE offers authoritative vulnerability baselines, while OTX contributes up-to-date community sightings. Most OTX objects in our dataset were of the indicator type, which, as defined by the STIX 2.1 standard [7], “contain a pattern that can be used to detect suspicious or malicious cyber activity.” Thus, these objects are limited with regard to providing intelligence on attack campaigns and other deeper CTI and need to be complemented with other CTI objects that offer more context on threats.

For data-driven defense systems, multi-source CTI can also improve generalization. One persistent risk in ML for cybersecurity is overfitting to the style or bias of a single feed. Training on combined, structurally diverse datasets mitigates this risk and can produce models that are more resilient and representative of the evolving IoT threat ecosystem.

6.4. Support for DL and AI in CTI

Our study sheds light on how CTI can feed into DL-based cybersecurity systems. One clear message is that structured CTI data can significantly ease the burden of data preprocessing for ML. In traditional setups, analysts spend a lot of time converting unstructured threats, e.g., system logs, news feeds, etc. [26], into data that tools can use. With STIX-enabled feeds like OTX, a lot of that work is already performed, as they provide JSON objects that can directly be turned into feature vectors. This accelerates the development of explainable AI models as well, since features correspond to meaningful fields (e.g., “severity = high”). Our findings indicate that DL can enhance CTI through semantic enrichment. The relatively low usage of standardized vocabularies in CTI feeds implies that a DL model (especially NLP-based) could be employed to tag or classify CTI entries into a common taxonomy. For instance, a language model could read the description of an OTX pulse and classify it into MITRE ATT&CK [28] technique categories or extract the malware family mentioned, effectively aligning the data object towards STIX both semantically and syntactically by adding the labels in their proper fields that the feed initially lacked. This could be performed post hoc to improve the dataset before feeding it into another detection model. DL can supply the “missing semantics” that make structured CTI more useful. A recent work [29] already demonstrated this through using transformers to map CTI text to ATT&CK techniques. Our study confirms the need for this approach by showing how underutilized those semantics are currently, particularly for IoT.

6.5. Practical Recommendations

From a practitioner’s standpoint, e.g., a security architect or SOC manager who considers CTI feeds for an ML/DL/AI threat detection-based system, our comparison yields the following actionable insights:

- If structured data with completeness are needed, OTX is a strong candidate, especially given that it is free. It gives a standardized feed that covers the 5W3H of incidents well. However, practitioners should be aware that it is community data. Thus, it might include a mix of very relevant and some less relevant information. Also, it often lacks deeper analysis as it mostly provides raw indicators. Yet, these indicators can be enriched with CTI from other sources.

- NVD’s CVE/CPE feed is an essential complement for anything vulnerability-related in IoT. In a proactive defense system, linking threat intelligence about attacks to the known vulnerabilities on one’s devices is crucial. We suggest always including CVE data in the CTI mix for IoT security programs. The good news is that NVD data is consistently structured (though not STIX), and our analysis shows that it can connect to other intel via CVE IDs.

- Focus on network-threat detection: Since most IoT threats use network vectors and show high severity, investing in network traffic analysis with CTI matching is worthwhile. If one is developing a DL-based IDS for IoT, integrating CTI that highlights network indicators (like malicious IPs or domains from OTX pulses) can improve detection of inbound attacks. Our findings support approaches like that of Lin et al. [8], which integrates CTI lookups with an IDS model. Given that CTI can tell when an IP is associated with known IoT malware, the IDS can be more confident in flagging that traffic.

6.6. Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations in our study:

- Given that our collection was in the thousands, we could not verify the resulting objects of our collection manually. Any limitations within the querying processes of the platforms automatically propagate to our work. We only relied on the fact that the platforms enabled the capability to search using keywords. However, our visual review of randomly selected data objects aimed to minimize the noise by making sure that the objects were relevant.

- Our data collection relied solely on keyword searches (“IoT” and “Smart Home”), which may not have captured all relevant CTI. It is possible that some IoT-related threats were described without those keywords and thus were missed. This means that our dataset might not be exhaustive. However, we sought to mitigate this limitation by using two keywords to ensure the results were indeed IoT-related. The inclusion of “Smart Home” (a specific phrase) likely improved precision at the cost of possibly missing generic IoT mentions. Future work could expand the keyword set (e.g., include specific IoT device names or protocol names) to cast a wider net.

- We used the free/public version of the commercial platform. Commercial CTI platforms often have premium data or features we could not access. For example, OTX has only community data, and a paid threat feed might have more consistent semantic labeling. We cannot generalize our results to all CTI platforms or even the full capacities of the ones studied. What we did was establish a baseline for publicly available data. It is possible that the paid versions use STIX more “lazily” or more fully; e.g., Ramsdale et al. [26] talk about “laziness” in using STIX fields correctly, which we did observe to an extent. This point remains open and organizations evaluating CTI should consider that internal formats might differ.

- We did not deeply verify the correctness of every data object. For example, OTX pulses are user-contributed and could contain mistakes. Our assumption was that any noise (like irrelevant hits or erroneous data) is minimal relative to the large dataset (>6K objects). Indeed, we noted a few odd entries (e.g., a CVE from 1998 that probably matched “IoT” as a string in some description erroneously). These very few (pre-2017) CVEs were <3% of CVEs we pulled, so they likely do not impact trends much.

- With a total of 90 fields among the three types of data objects, our cross-platform field equivalence analysis might have missed some relationships. We identified overlaps manually. There could be other relationships that are more subtle, and thus we were unable to capture them. A thorough automated correlation that is based on values (using hash matching or URL matching across datasets) could reveal more interconnections. We leave that level of correlation analysis to future work, as it requires a different approach.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, we studied CTI related to smart home and IoT devices by examining data from three platforms: AlienVault OTX, NVD’s CVE, and NVD’s CPE. Using a dataset of approximately 6.2K CTI objects, our analysis, which covered statistical information about the objects and syntactic and semantic aspects of them, yielded several main findings. First, we observed an upward trend in IoT/smart home threat intelligence over recent years in the platforms’ data. This indicates that as IoT adoption grows, relevant threat intelligence is also ramping up, which is a positive sign for defenders. On the syntactic level, we found that the commercial CTI platform does incorporate STIX 2.1 fields with full adherence. Notably, most of the STIX-based data objects in the commercial platform belonged to a particular SDO (94% of OTX objects were of the type indicator). With regard to the mapping of the fields across platforms, there were several similar and equivalent fields among the platforms. On the semantic and content level, the main threat vector in the data was network-based attacks. In this context, we noted that the STIX-based data objects in the commercial platform failed to adapt the STIX open vocabulary to an acceptable level. This showed the limited actionability that these data object types offer to practitioners when they try to protect their organization’s infrastructure against attacks. The efficacy of a DL model for threat detection or prediction is directly tied to the quality of the input data. Improving CTI data along the lines suggested (structured formats, consistent semantics, and comprehensive coverage) helps in feeding better information to the models, thus enabling them to learn more accurate patterns of malicious vs. benign behavior.

Future work will extend our analysis to additional platforms and delve into automating the integration of CTI for AI systems. One promising avenue is developing a CTI-driven threat prediction model, which could use the time series of CTI reports to predict the next big IoT malware campaign or which vulnerability will be exploited next, i.e., threat forecasting. The insights into trends and common fields from this study provide a foundation for feature-engineering such models. Another direction is exploring knowledge graph representations of CTI (with nodes for threats, vulnerabilities, threat actors, etc.), which could be an excellent structure for graph neural networks to reason over. Given the interconnectedness that could be established from the different sources, CTI is naturally graph-shaped data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R., I.T.-D.V., and A.I.G.-T.; methodology, A.I.G.-T.; software, I.T.-D.V. and M.R.; validation, M.R.; formal analysis, M.R.; investigation, M.R. and I.T.-D.V.; resources, I.T.-D.V. and M.R.; data curation, I.T.-D.V. and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R. and I.T.-D.V.; writing—review and editing, M.R.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, M.R. and A.I.G.-T.; project administration, A.I.G.-T.; funding acquisition, M.R. and A.I.G.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The TED2021-131681B-I00 (CIOMET) grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities and the funding received from the EU Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No. 101021377 (TRUST aWARE). This work is supported by grant DISCOVERY (PID2023-148716OB-C33) funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and by the Comunidad de Madrid (Spain) under the project RAMONES-CM (TEC2024-COM504), co-financed by European Structural Funds (ESF and FEDER). This work is part of the I-Shaper Project (C114/23), a collaboration agreement between Instituto Nacional de Ciberseguridad (INCIBE) and Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. This initiative is being carried out within the framework of the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan funds, funded by the European Union (Next Generation).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- What is the Internet of Things? Definition and Explanation. Available online: https://www.kaspersky.com/resource-center/definitions/what-is-iot (accessed on 4 September 2023).[Green Version]

- Internet of Things (IoT) Market Advancements Driving Smart Connectivity Solutions. Available online: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/internet-of-things-market (accessed on 28 October 2025).[Green Version]

- Number of Internet of Things (IoT) Connections Worldwide from 2022 to 2023, with Forecasts from 2024 to 2033. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1183457/iot-connected-devices-worldwide/ (accessed on 28 August 2024).[Green Version]

- Top 10 IoT Device Vulnerabilities to Enhance IoT Security. Available online: https://www.hostduplex.com/blog/top-iot-device-vulnerabilities/ (accessed on 28 August 2024).[Green Version]

- Sasi, T.; Lashkari, A.H.; Lu, R.; Xiong, P.; Iqbal, S. A comprehensive survey on IoT attacks: Taxonomy, detection mechanisms and challenges. J. Inf. Intell. 2024, 2, 455–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MID-YEAR UPDATE 2023 SonicWall Cyber Threat Report. Available online: https://www.loophold.com/mid-year-2023-cyber-threat-report-sonicwall/ (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Introduction to STIX. Available online: https://oasis-open.github.io/cti-documentation/stix/intro (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Lin, Y.D.; Lu, Y.H.; Hwang, R.H.; Lai, Y.C.; Sudyana, D.; Lee, W.B. Evolving ML-based Intrusion Detection: Cyber Threat Intelligence for Dynamic Model Updates. IEEE Trans. Mach. Learn. Commun. Netw. 2025, 3, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Bélanger, F.; Daultrey, S. Promoting research on cyber threat intelligence sharing in ecosystems. J. Cybersecur. 2025, 11, tyaf016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 2023 IOT Security Landscape Report. Available online: https://www.bitdefender.com/files/News/CaseStudies/study/429/2023-IoT-Security-Landscape-Report.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Overview of IoT Threats in 2023. Available online: https://securelist.com/iot-threat-report-2023/110644/ (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Roberts, A. Cyber Threat Intelligence: The No-Nonsense Guide for Cisos and Security Managers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barnum, S. Standardizing cyber threat intelligence information with the structured threat information expression (stix). Mitre Corp. 2012, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- STIX and CybOX Parser Data Mappings. Available online: https://knowledge.threatconnect.com/docs/stix-and-cybox-parser-data-mappings (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Anomali. Available online: https://www.anomali.com/products/threatstream (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- AutoFocus API STIX Support. Available online: https://docs.paloaltonetworks.com/autofocus/autofocus-api/about-the-autofocus-api/autofocus-api-stix-support (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Our Journey to Support STIX 2.1. Available online: https://blog.eclecticiq.com/our-journey-to-support-stix-2.1 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Ring, T. Threat intelligence: Why people don’t share. Comput. Fraud Secur. 2014, 2014, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponemon Institute and Norse, July 2013. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20160401134059/https://pages.ipvenger.com/PonemonImpactReport_LP.html (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Sauerwein, C.; Sillaber, C.; Mussmann, A.; Breu, R. Threat Intelligence Sharing Platforms: An Exploratory Study of Software Vendors and Research Perspectives. Proceedings der 13; Internationalen Tagung Wirtschaftsinformatik: St. Gallen, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 837–851. [Google Scholar]

- A White Paper on the Key Challenges in Cyber Threat Intelligence: Explaining the “See It, Sense It, Share It, Use It” Approach to Thinking About Cyber Intelligence. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20250326005710/https://www.odni.gov/files/NSP/Private_Sector/Feature/1-15-2020-Loretta_Dusek-ODNI_Key_Challenges_in_CTI_White_Paper_Unclass_FINAL-BW2.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Tounsi, W.; Rais, H. A survey on technical threat intelligence in the age of sophisticated cyber attacks. Comput. Secur. 2018, 72, 212–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlette, D.; Böhm, F.; Caselli, M.; Pernul, G. Measuring and visualizing cyber threat intelligence quality. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2021, 20, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo e Silva, A.; Costa Gondim, J.J.; de Oliveira Albuquerque, R.; García Villalba, L.J. A Methodology to Evaluate Standards and Platforms within Cyber Threat Intelligence. Future Internet 2020, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantos, K.; Spyros, A.; Papanikolaou, A.; Kritsas, A.; Ilioudis, C.; Katos, V. Interoperability challenges in the cybersecurity information sharing ecosystem. Computers 2020, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsdale, A.; Shiaeles, S.; Kolokotronis, N. A comparative analysis of cyber-threat intelligence sources, formats and languages. Electronics 2020, 9, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCTI Documentation Space. Available online: https://docs.opencti.io/latest/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- ATT&CK Matrix for Enterprise. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/ (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Ampel, B.; Vahedi, T.; Samtani, S.; Chen, H. Mapping exploit code on paste sites to the mitre att&ck framework: A multi-label transformer approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Charlotte, NC, USA, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).