Abstract

This paper presents an optimized control strategy based on a Doubly Fed Induction Generator (DFIG) and Gravity Energy Storage System (GESS) for AC voltage support in unbalanced grid conditions. The presented control aims to achieve precise rotational speed control, voltage stabilization, and harmonic component suppression. The optimization strategy responds to voltage and frequency fluctuations in an unbalanced grid. Based on Grid-Forming (GFM) control, it adjusts the DFIG’s operating state in real time. This ensures stable voltage support and mitigates harmonic distortion caused by the unbalanced grid. Simulation results, under a weak grid (SCR = 3) and unbalanced (0.9 p.u. voltage sag) conditions, validate the strategy, which reduces rotor current THD from 12.57% to 1.71% and maintains precise speed tracking during a 0.8 p.u. to 0.7 p.u. load change. The results demonstrate that the presented control method effectively improves grid power quality. It also enhances system stability and reliability. This approach provides strong support for integrating renewable energy into unbalanced grids.

1. Introduction

With the development and advancement of technology, the shares of renewable energy and power–electronic equipment in power systems are continuously increasing [1,2]. However, due to the real-time variability of natural factors such as wind speed and solar irradiance, the outputs of wind farms and photovoltaic plants exhibit fluctuations [3]. This instability leads to variations in grid voltage, current, and frequency. This variation affects power quality. It also increases system operating costs and dispatching complexity [4,5]. This creates an urgent need for energy storage as a means of peak shaving and valley filling [6,7]. GESS uses electric machines to realize bidirectional conversion between the mechanical energy of a payload and electrical energy. GESS provides large-scale storage capability. The systems are minimally affected by environmental factors. They are stable and reliable and offer a long service life with low maintenance costs. Consequently, they have attracted widespread attention in recent years [8,9,10].

Beyond the supply side, the electrification of transportation and the rise of hydrogen mobility are elevating power–electronic penetration on the demand side. High-power fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) [11,12,13] and hydrogen refueling stations, together with their auxiliary DC-link and AC interface converters, can aggravate voltage deviation, harmonic distortion, and negative-sequence currents in distribution feeders under high-penetration scenarios, thereby imposing stricter requirements on primary frequency regulation and voltage support. These observations further substantiate the need for deploying voltage-source-capable storage resources—such as the DFIG-based GESS studied in this work—to enhance power quality and operational resilience under weak and unbalanced grids.

The rotor speed of a DFIG does not need to synchronize with the stator frequency. By controlling the power output through the rotor-side converter, variable-speed and constant-frequency operation can be achieved [14]. By regulating rotor speed to control the translation velocity of the payload, the total energy input/output of the system can be further adjusted, which confers significant advantages for GESSs. However, the DFIG possesses relatively small rotational inertia and provides limited inherent grid support; therefore, grid-forming control is required to realize voltage support.

Wind-power DFIG controls focus on maximum power point tracking (MPPT) and active/reactive power regulation. A GESS instead prioritizes precise speed regulation because commanded speed schedules energy exchange. This shift imposes two requirements. First, there is speed–GFM coordination: the machine must present voltage-source (grid-forming) behavior at the PCC under weak or unreliable grids while the speed loop remains primary. Second, there is robustness to negative-sequence voltages: unbalance excites 2ω oscillations in currents, torque, and power that degrade speed tracking. The controller therefore co-designs the speed loop with frequency/voltage droops and selective 2ω mitigation, rather than inheriting a wind-orientated, power-centric hierarchy.

In recent years, research on GFM DFIGs aimed at supporting weak grids has been concentrated on wind-power scenarios. The core issues involve the coordination of voltage/current control under fault-current constraints, transient stability, and asymmetrical fault ride-through. Recent studies address fault-current limitation (FCL) and grid code compliance. They present time-sequential virtual-impedance or current-limiting schemes. These schemes satisfy emerging interconnection requirements. They focus on current response during low-voltage ride-through (LVRT). They also address post-fault power-recovery time. Conventional virtual-impedance-based FCL can cause transient overcurrent. It may also produce secondary shocks during recovery. Therefore, a cuttable or adaptive virtual impedance must be designed. This design balances capacity utilization and stability [15,16]. A study examines transient modeling and stability mechanisms [17]. It shows that when the rotor-side current is limited, the GFM-DFIG voltage controller dynamics couple with the current-limiting logic. This coupling leads to three typical post-fault behaviors. These emerge from limiting, high-frequency oscillations and locked saturation. This mechanism differs from that of conventional GFM voltage-source converters (VSCs), and stability assessment and parameter selection should consider the saturated current angle and power-angle trajectories. For asymmetrical fault ride-through (AFRT), existing work uses internal-voltage-vector/voltage-orientation concepts to coordinate current allocation and voltage support, thereby improving ride-through and resynchronization capability under unbalanced conditions [18,19]. An enhanced hybrid synchronization control (EHSC) has been presented to enhance transient synchronizing and damping [19]. EHSC is built upon voltage-orientated control (VOC). It adds an adaptive integral channel. This channel suppresses synchronization angle overshoot caused by active-power imbalance. Design guidelines for parameter tuning and minimum boundary-crossing time are provided. Results show the stability region expands under low SCR, deep voltage sag, or high power commands. A double-layer model predictive control (MPC) strategy for GFM-DFIG has been demonstrated [20]. This applies to primary-frequency-regulation and microgrid scenarios. The upper layer adaptively tunes VSG coefficients and corrects power commands. The lower layer uses finite-set tracking and circuit reconfiguration. This improves stator voltage/current dynamics, thereby enhancing frequency support and control quality. One study addresses electromechanical coupling/drivetrain oscillations [21]. It characterizes synchronization between GFL DFIGs and GFM devices. The focus is on the electromechanical time scale. It considers perspectives of electro-mechanical speed coupling and control switching. The study notes that power mismatch and control switching during faults can excite the rotor-speed channel. This excitation induces oscillations. A trade-off is needed between synchronization and current-limiting/reactive-power support. In addition, disturbance-rejection stator-flux control (DRSFC) strengthens inner-loop robustness and dynamic response. DRSFC clarifies functional partitioning and coupling paths. These paths exist among the RSC inner/outer loops and the grid-side VOC. Moreover, some work reconfigures the converter topology using SMES. This reinforces fault ride-through and grid-forming capability. This reflects a trend of “control–hardware” co-design [22,23]. In summary, existing GFM-DFIG research primarily targets optimal wind-power output. It emphasizes trade-offs between stability and dynamic performance. This occurs under maximum power point tracking (MPPT) conditions involving faults, weak grids, and frequency support.

Moreover, with the increasing penetration of electric vehicles (EVs) and their bidirectional charging interactions, emerging studies have begun to investigate the coordinated control between GFM-DFIGs and large-scale EV charging infrastructures to mitigate voltage fluctuations and enhance overall stability in weak distribution grids [24,25,26,27].

Recent grid-forming strategies for DFIGs target wind turbines and emphasize power regulation and grid support during faults, weak grids, or frequency excursions. Direct transfer to a GESS leaves the speed objective under-served and fails to coordinate speed regulation with grid-forming behavior. In GESS applications, the controller prioritizes speed tracking as the outer-loop task, ensures voltage-source characteristics, and suppresses 2ω-induced torque and power ripples. This integration yields accurate motion control and reliable grid support.

Meanwhile, asymmetrical grid faults are more frequent and more likely than symmetrical faults as listed in Table 1. Voltage unbalance must be considered in the DFIG-GESS control system design. Even a small unbalanced (negative-sequence) voltage will cause severe imbalance. This imbalance affects both stator and rotor currents. It leads to unbalanced heating of the windings, torque pulsations, and power oscillations.

Table 1.

Sequence components and their effects in generator mode (DFIG).

Therefore, this paper designs an optimized grid-forming control strategy for DFIG-based GESS to achieve three control objectives: (1) precise control of the payload translation velocity (i.e., rotor speed); (2) voltage support; and (3) suppression of harmonic components under unbalanced grids. This strategy can be applied to provide effective AC voltage support under unbalanced grid conditions. Leveraging the unique characteristics of the DFIG, the system integrates precise speed control, voltage stability, and harmonic suppression to ensure sustained and reliable grid support. The method enhances grid stability. It utilizes the distinctive capabilities of the DFIG and GESS. It provides a scalable and sustainable solution. This solution offers strong support for renewable-energy integration under unbalanced grid conditions.

Section 2 develops the DFIG–GESS model, the grid-following baseline, and the mechanism that produces twice-fundamental oscillations under unbalance. Section 3 designs a speed–GFM co-design: the speed outer loop, frequency/voltage droops, and targeted 2ω mitigation in current control. Section 4 validates the method under weak and unbalanced conditions, showing voltage support and high-fidelity speed tracking. Section 5 concludes and outlines future work.

2. DFIG–GESS Mathematical Modeling and Control Strategy

This chapter begins with DFIG modeling. The mathematical model in the dq coordinate frame is used. This obtains the grid-following control block diagram for DFIGs in conventional wind power applications. Next, the theory is developed to explain the characteristic twice-fundamental oscillations in output power and electro-magnetic torque exhibited by DFIG-based systems under unbalanced grids, together with the corresponding mitigation measures. Finally, aligned with the control objectives of DFIG-GESS, improvements are made to the theoretically constructed control block diagram to progressively realize these objectives. Switching and conduction losses affect efficiency but not the state evolution at the control bandwidths considered. We omit explicit loss terms from the state equations and account for them in power and efficiency calculations. Including a constant or a fine loss term shifts the steady-state power balance but does not modify the loop structure or the stability margins.

2.1. DFIG Mathematical Modeling and Grid-Following Control

Mathematical modeling of the DFIG starts by establishing its three-phase model. This model is for the stator and rotor in the stationary coordinate frame. It yields a set of nonlinear, time-varying, and strongly coupled multivariable system equations. Through coordinate transformation for decoupling and simplification, the mathematical model in the synchronous dq frame is obtained as follows [28]:

The flux-linkage equations are as follows:

The voltage equations are as follows:

The torque and motion equations are as follows:

where ω1 is the synchronous electrical angular speed; ωr is the rotor electrical angular speed; ωslip is the slip speed; np is the number of pole pairs; J is the moment of inertia; Te is the electromagnetic torque; TL is the mechanical torque; Rs is the stator resistance; Rr is the rotor resistance; isd and isq are the stator current components on the d- and q-axes of the rotating frame, respectively; ird and irq are the rotor current components on the d- and q-axes of the rotating frame, respectively; Lr is the rotor inductance; Lm is the magnetizing (stator–rotor mutual) inductance; Ls is the stator inductance; ψsd and ψsq are the stator flux linkage on the d- and q-axes of the rotating frame, respectively; ψrd and ψrq are the rotor flux linkage on the d- and q-axes of the rotating frame, respectively; usd and usq are the stator-side voltages on the d- and q-axes, respectively; and urd and urq are the rotor-side voltages on the d- and q-axes, respectively.

For a doubly fed induction machine, the stator is directly connected to the grid; thus, grid-voltage orientation is equivalent to stator-voltage orientation, leading to the following relation:

Here, Us denotes the stator-side output-voltage vector, i.e., the grid-voltage vector. By substituting the above equation into the rotor-voltage equations in the dq frame, we obtain the corresponding expressions:

Under grid-voltage orientation, the active power Ps and reactive power Qs delivered from the stator side to the grid can be expressed in terms of the rotor dq-axis currents as follows:

It is evident that, with grid-voltage orientation, ird and irq serve as the current components associated with active and reactive power, respectively. Therefore, the active and reactive power injected from the stator to the grid can be independently regulated, i.e., decoupled, by controlling the rotor d- and q-axis currents, respectively. Let

where σ = 1 − Lm2/(LsLr) is the leakage coefficient. To eliminate steady-state error, an integral term (integral action) can be introduced,

where ird* and irq* are the rotor current commands on the d- and q-axes, respectively; kirp, kiri are the proportional and integral gains of the rotor current controller. By substituting (1) and (2) into (3), the required reference voltage for the rotor-side PWM converter is

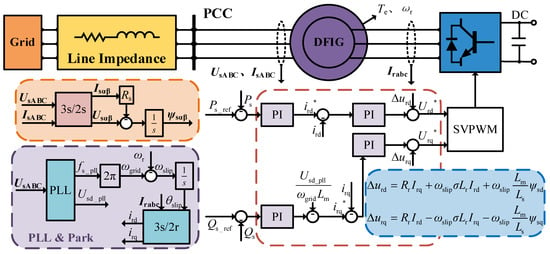

The control block diagram is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Grid-following control block diagram of the DFIG.

In wind power systems, MPPT determines the “maximum-generation” reference according to the optimal tip–speed ratio to obtain Ps_ref, which serves as the active-power outer-loop reference of the RSC. In the stator-voltage-orientated dq frame, the P outer loop regulates the torque-component current idr. This works with the inner current loop, feedforward decoupling, and SVPWM. Consequently, this combination imposes the electromagnetic torque on the rotor rapidly and accurately. The reactive power (via an independently controlled Q channel) is essentially decoupled from MPPT. In the below-rated wind speed, the system “tracks maximum power”, whereas in the above-rated one, it switches to rated-power limiting and cooperates with the pitch angle increase to suppress overspeed, thereby improving energy capture while satisfying grid integration and safety constraints.

In gravity energy storage systems, the mechanical input load torque is proportional to the carried payload (neglecting mechanical damping), and the payload’s translation velocity is controllable. Therefore, it is unnecessary to employ MPPT to generate an outer-loop reference corresponding to “maximum generation”. Meanwhile, to realize a controllable payload translation velocity, the control strategy must be reconsidered.

2.2. Mathematical Modeling of DFIG-GESS Under Unbalanced Grid Conditions

We model the machine with the Asynchronous Machine pu Units block (wound-rotor). In this block, stator and rotor windings are Y-connected to an internal neutral point. The stator is interfaced as a three-wire terminal without an external neutral, and the rotor is connected to a three-wire back-to-back converter. Therefore zero-sequence currents cannot circulate in either stator or rotor windings; any zero-sequence voltage appears only as common-mode and is handled by the converter interface. These settings match the block documentation.

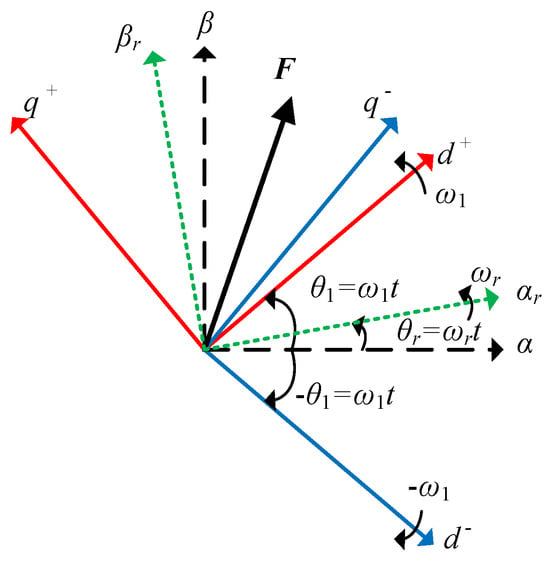

Given that the DFIG-GESS is connected to the grid using a three-phase three-wire wiring configuration, there is no path for zero-sequence components in the system. Consequently, the asymmetrical three-phase electromagnetic quantities can be decomposed into symmetrical positive-sequence and negative-sequence components using the instantaneous symmetrical component method. The corresponding spatial positional relationships among the two-phase stationary αβ reference frame, the dq+ reference frame rotating at the synchronous-speed ω1, and the dq− reference frame rotating at the negative synchronous speed -ω1 are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The corresponding spatial positional relationships among the two-phase stationary αβ reference frame, the dq+ reference frame rotating at the synchronous-speed ω1, and the dq− reference frame rotating at the negative synchronous speed −ω1.

After coordinate transformation, the electromagnetic quantity space vector Fαβ is expressed as

Here, the superscript ‘+’ and ‘−’ denote the forward- and reverse-rotating synchronous-speed reference frames, respectively, while the subscript ‘+’ and ‘−’ represent the positive-sequence and negative-sequence components, respectively as listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of vectors in different spatial coordinate systems.

Neglecting the copper losses in the stator and rotor windings, the expressions for stator-side electromagnetic power, total system electromagnetic power, rotor-side electromagnetic power, and electromagnetic torque under unbalanced grid conditions can be derived as follows and Table 3:

Table 3.

Description of vector in dq coordinate system.

Among them, Ωr = ωr/np is the synchronous mechanical angular velocity, and np is the polar logarithm. The presence of negative-sequence components causes second-order harmonic fluctuations. These fluctuations occur in the stator-side electromagnetic power. They also appear in the total system electromagnetic power, rotor-side electromagnetic power, and electromagnetic torque.

An unbalanced three-phase voltage contains a negative-sequence term. In the synchronous frame, the positive-sequence flux interacts with the negative-sequence current yields. Hence currents and torque contain a component at 2ω0. This motivates the PI–R current loop and the droop-path 2ω filtering used in this paper.

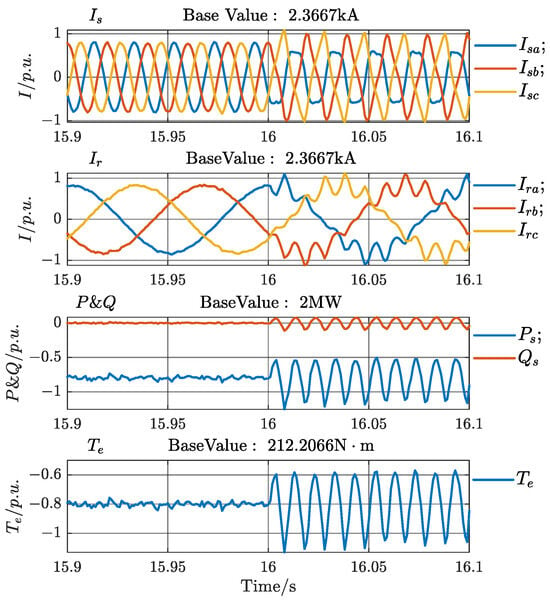

Simulation results illustrate the unbalanced grid’s impact on the DFIG-GESS. These are shown in Figure 3. The figure provides waveforms for stator and rotor currents. It also shows stator-side power and electromagnetic torque.

Figure 3.

DFIG-GESS stator and rotor currents, stator electromagnetic power, and electromagnetic torque waveform under the unbalanced grid at unit values.

In Figure 3, the system operates under a balanced grid condition before 16 s. At 16 s, a sudden voltage sag in phase B of the power supply is introduced, plunging the system into an unbalanced grid condition. Under the unbalanced grid, the rotor current is affected. It contains the fundamental component at the slip frequency sf1. It also contains harmonic components at the frequency of |−(ω1 + ωr)f1/ω1|. These harmonic components manifest as twice the fundamental frequency (100 Hz for a 50 Hz system) alternating quantities in the dq+ reference frame rotating at the positive synchronous speed ω1. Grid voltage imbalance induces unbalance in the DFIG stator currents. This leads to second-order harmonic fluctuations (twice the fundamental frequency). These fluctuations appear in the active/reactive power and electromagnetic torque. Simultaneously, it jeopardizes the stability of the DC bus voltage, therefore having significant adverse impacts on the overall stability and safety operation of the system.

3. DFIG–GESS Control Objectives and Strategies

Based on the foregoing derivations, the conventional grid-following control strategy for DFIGs in wind power systems proceeds as follows: MPPT-based control achieves power decoupling via grid-voltage d-axis vector control, thereby converting active and reactive power regulation into control of the rotor d- and q-axis currents. In this way, the DFIG-based wind power system is controlled. In contrast, for a DFIG applied to GESS, it is unnecessary to obtain, via MPPT, the state variables corresponding to the real-time maximum power. Meanwhile, the DFIG possesses a variable-speed, constant-frequency control characteristic, enabling the system to operate according to a preassigned speed command so as to meet the application requirements of GESS. Accordingly, Control Objective 1 for DFIG-GESS is presented: precise control of the payload translation velocity. The implementation scheme is as follows:

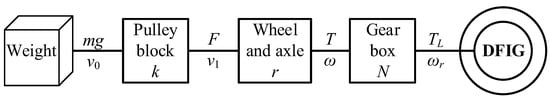

In a DFIG-GESS, the payload is mechanically coupled to the DFIG rotor through a mechanical assembly. As shown in Figure 4, this assembly includes a pulley block, a drum, and a gearbox. The pulley block serves as a multi-stage force-transmission node; its combination of fixed and movable pulleys can be designed according to specific GESS application scenarios to realize directional deflection and magnitude scaling of the force vector. The drum acts as the hub for linear-to-rotational conversion: by winding the rope, linear displacement is converted into rotational motion of the shaft, while simultaneously mapping tension to torque and translation velocity to angular speed. The gearbox functions as a speed-adaptation unit: by reducing speed to increase torque (or increasing speed to reduce torque), it matches the system power flow and is used to adjust speed and torque. Under ideal conditions, the mechanical torque TL is as follows:

where k is the pulley-block mechanical advantage, r is the drum radius, N is the gearbox ratio, m is the payload mass, and g is the gravitational acceleration.

Figure 4.

Mechanical transmission electronic control collaborative system.

Friction torque is small compared with the rated electromagnetic torque in the operating region. We therefore treat friction as a bounded disturbance, dT. A linear viscous term, bωm, can be lumped into dT without altering the state dimension. At very low speeds, friction becomes non-negligible. If needed, the model admits Tf = bωm + dT (viscous plus Coulomb) and the control structure remains unchanged.

The DFIG can regulate the rotational speed of the air-gap magnetic field by adjusting the rotor excitation current via the rotor-side converter, thereby controlling the rotor speed, i.e., the output-shaft speed of the gearbox. Since the drum’s angular speed is strictly synchronized with the gearbox input shaft, controlling the DFIG rotor speed is equivalent to controlling the payload translation velocity. This velocity is given by the following expression:

where v0 is the payload translation speed.

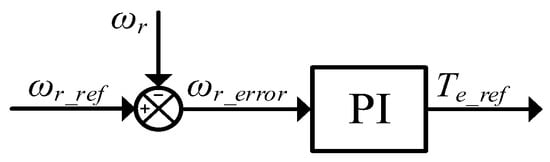

According to the rotor motion equation, the variation in the rotor speed ωr is driven solely by the difference between the mechanical torque and the electromagnetic torque. The mechanical torque depends on the payload and the mechanical assembly; therefore, direct regulation of the electromagnetic torque is the only means to control the speed. A speed closed-loop control is thus configured as shown in Figure 5:

Figure 5.

ωr_ref is the preset speed reference. The speed error ωr_error is obtained by subtracting ωr_ref from ωr, and an electromagnetic torque reference Te_ref is generated through a proportional–integral controller.

When the doubly fed machine operates in generating mode, the expression for the output electromagnetic active power is

where Pes is the stator-side electromagnetic power, Per is the rotor-side electromagnetic power, and Pe is the total electromagnetic power. According to previous work, in the supersynchronous mode, i.e., when the rotor speed exceeds the synchronous speed, Per > 0, and the rotor delivers active power. In the subsynchronous mode, i.e., when the rotor speed is lower than the synchronous speed, Per < 0, and the rotor absorbs active power. The rotor electromagnetic power adjusts dynamically with the rotor speed so as to keep the stator electromagnetic power approximately constant.

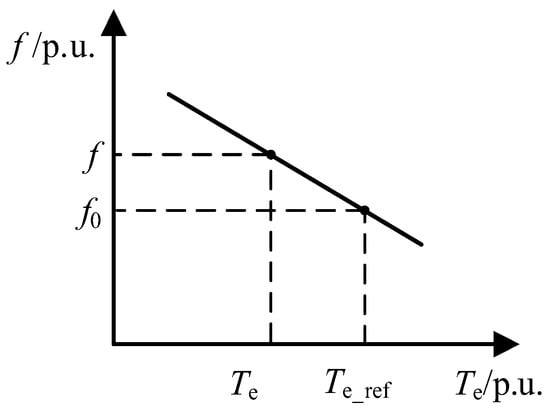

During normal system operation, variations in synchronous speed can be neglected, and the stator-side electromagnetic power is proportional to the electromagnetic torque. Therefore, by analogy with the droop characteristic of a synchronous generator, a droop curve between electromagnetic torque and frequency is constructed as in Figure 6:

where f0 is the rated grid frequency, Te_ref is the electromagnetic torque reference produced by the speed closed loop, Te is the actual electromagnetic torque, KTe is the electromagnetic-torque droop coefficient, and f is the frequency reference output by the droop control.

Figure 6.

The droop curve between electromagnetic torque and frequency.

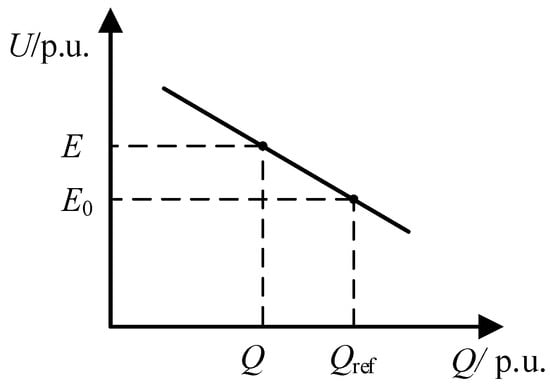

Meanwhile, the stator-side voltage-magnitude reference EEE is constructed using the conventional droop characteristic between reactive power and voltage as in Figure 7:

where E0 is the rated grid voltage magnitude, Qref is the stator-side reactive-power reference, Q is the actual stator-side reactive power, KQ is the reactive-power droop coefficient, and E is the stator-side voltage magnitude output by the droop control.

Figure 7.

The droop curve between reactive power and voltage.

Distinct from conventional grid-following control, which relies on a PLL to track the grid voltage, we add a current-source characteristic to the grid, which can cause the system output voltage to change abruptly when the PCC voltage experiences a sudden variation, thereby offering limited grid-support capability; the presented strategy synthesizes the three-phase stator voltage EABC using the frequency reference and voltage-magnitude reference obtained from the torque–frequency droop and the reactive-power–voltage droop, respectively. This retains the benefits of traditional droop control and presents a voltage-source characteristic to the grid: when a PCC voltage jump occurs due to a fault, EABC does not undergo a sudden change, providing a certain level of grid support while also enabling stand-alone supply to local loads.

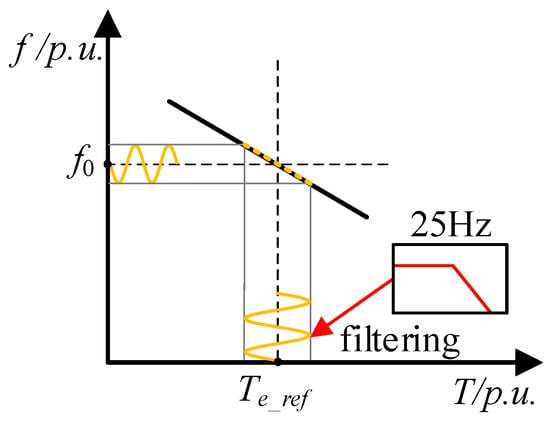

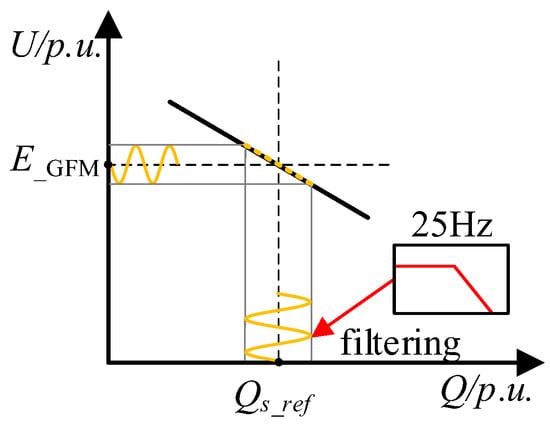

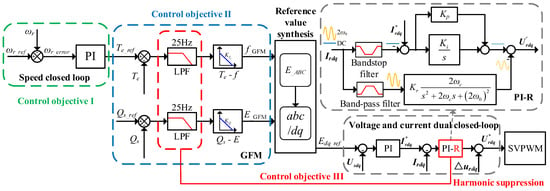

Finally, for unbalanced-grid scenarios, Control Objective 3 is presented: suppression of harmonic components introduced by grid unbalance. The strategy comprises two parts. The first measure is phenomenological: it directly address the twice-fundamental harmonic components in power and electromagnetic torque. In the grid-forming control, filters are introduced to remove the twice-fundamental components from the electromagnetic torque reference, as well as from the feedback signals of electromagnetic torque and reactive power.

As shown in Figure 8, based on the aforementioned grid-forming control, when a DFIG-based system operates under an unbalanced grid, the twice-fundamental oscillation of the electromagnetic torque is fed back to the frequency reference through the constructed Te–f droop characteristic. This causes the synthesized frequency reference f_GFM to contain a twice-fundamental component, whereby subsequent control stages are affected and system stability is degraded. Therefore, when setting the frequency reference f_GFM, a low-pass filter is employed to preferentially remove the twice-fundamental component that deteriorates the control system, so that the frequency reference f_GFM remains relatively stable.

Figure 8.

The filter was introduced in the f-T droop curve.

Similarly, the voltage-magnitude reference is treated in the same way. As shown in Figure 9, when a DFIG-based system operates under an unbalanced grid, the twice-fundamental oscillation of reactive power is fed back to the voltage-magnitude reference through the constructed Q-V droop characteristic. This causes the synthesized voltage-magnitude reference E_GFM to contain a twice-fundamental component, whereby subsequent control stages are affected and system stability is degraded. Therefore, when setting the voltage-magnitude reference E_GFM, a low-pass filter is employed to preferentially remove the twice-fundamental component that deteriorates the control system, so that the voltage-magnitude reference E_GFM remains relatively stable.

Figure 9.

The filter was introduced in the U-Q droop curve.

We implement a second-order low-pass with a cutoff of 25 Hz and damping ζ = 0.707 in both Te–f and Q–V droop paths to attenuate 2ω ripple while preserving slow droop dynamics. When required, we add a second-order notch centered at 100 Hz (2ω0 = 200π rad/s) with a 3 dB bandwidth of 10 rad/s (≈ 1.59 Hz). This gives Q≈62.83 for the resonant section. All filters execute at fs = 10 kHz.

The other measure is theoretically motivated: a resonant controller is incorporated into the inner current loop to suppress the twice-fundamental harmonic components of the rotor d- and q-axis currents, thereby attenuating the twice-fundamental harmonics in electromagnetic torque and reactive power.

In Figure 10, in the PI-R part, Irdq = [ird, irq]T represents the actual rotor current measured in the dq reference frame, encompassing both positive-sequence and negative-sequence components. Specifically, the positive-sequence component appears as a DC component. And the PI path tracks the DC component,

where Kp is the proportional gain, and Ki is the integral gain, while the negative-sequence component manifests as an AC component at twice the fundamental frequency. And the resonant path suppresses the 2ω0 component,

where Kr is the resonant gain, and ωc is the cutoff frequency, typically selected within the range of 5–15 rad/s, and ω0 is the angular frequency corresponding to the second-order harmonic fluctuations at twice the fundamental frequency. We set the resonant 3 dB bandwidth BW = 10 rad/s (consistent with the paper’s ωc = 5 − 15 rad/s). Thus Q = 2ω0/BW ≈ 62.8. Irdq* = [ird*, irq*]T denotes the reference rotor current in the dq reference frame output by the outer control loop.

Figure 10.

The overall rotor-side control block diagram.

The overall rotor-side control block diagram is shown in the following figure.

4. Simulation Verification and Case Analysis

A simulation model of the grid-type doubly fed gravity energy storage system is built in Simulink. At the same time, considering the large-scale access to new energy, the short-circuit ratio of parallel grid point is set to be equal to 3, which is a weak current network, and the primary frequency regulation characteristics of the synchronous generator are simulated at the grid end. The unbalanced grid is set and discussed under different working conditions to verify the harmonic suppression and AC voltage support ability of the presented machine network cooperative control strategy. The simulation parameters are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Simulation parameters.

Before 16 s, the power grid is ideal. The B-phase voltage drops sharply from 1 p.u. of the per-unit value to 0.9 p.u. at 16 s. The system motor parameters are shown in the table below.

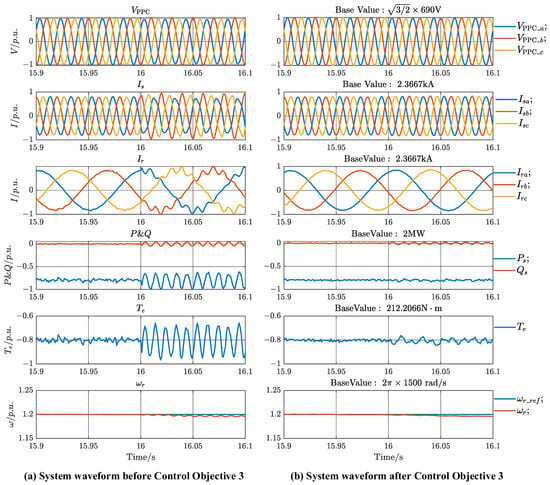

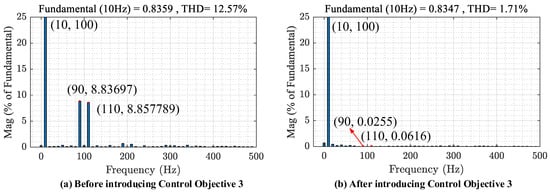

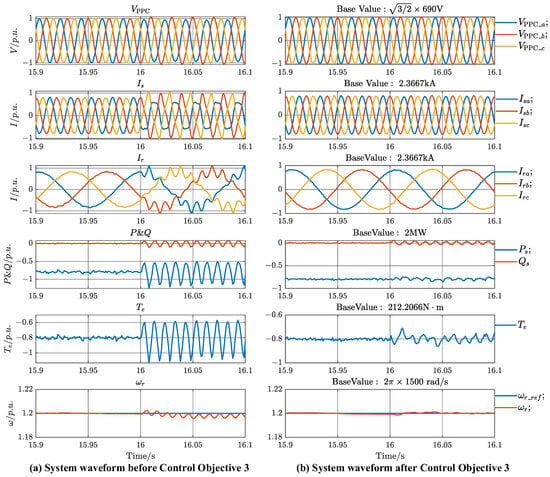

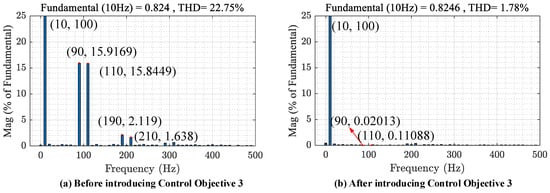

4.1. Harmonic Suppression Effect Under Unbalanced Grid

The waveforms of DFIG-GESS PCC voltage, stator, and rotor currents, stator electromagnetic power, and electromagnetic torque under the unit value are shown in Figure 11. The second-order harmonic fluctuations at twice the fundamental frequency of the rotor current in the dq+ coordinate system in the figure is effectively suppressed. The stator and rotor currents in the abc three-phase static coordinate system are closer to sinusoidal with less distortion. Figure 12 shows the THD analysis of the rotor current, and the harmonic (90 Hz, 110 Hz) of the rotor current is effectively suppressed under the Control Objective 3. Comparing Figure 12a,b, it can be seen that the machine network coordinated control including Control Objective 3 can effectively suppress the negative sequence component of the stator and rotor current, which reduces the rotor current THD from 12.57% to 1.71%, so as to suppress the second-order harmonic fluctuations at twice the fundamental frequency of the stator electromagnetic power and torque.

Figure 11.

DFIG-GESS PCC voltage, stator, and rotor currents, stator electromagnetic power, and electromagnetic torque waveform at per-unit values when the voltage of phase B dropped by 10%. (a) System waveform before introducing Control Objective 3. (b) System waveform after introducing Control Objective 3.

Figure 12.

The THD analysis results for ira when the voltage of phase B dropped by 10%. (a) before introducing Control Objective 3, (b) after introducing Control Objective 3.

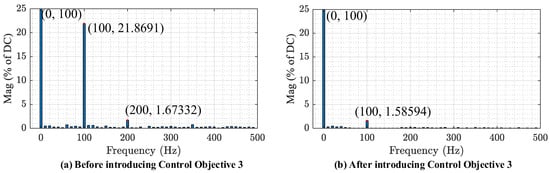

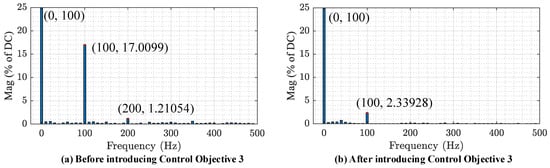

The results of FFT analyses of the stator electromagnetic power Ps and the electromagnetic torque Te are shown in Figure 13 and Figure 14. Under the baseline PI controller, the 2ω0 component in Ps accounts for 21.869% of the DC component, and the 2ω0 component in Te accounts for 17.01%. After introducing Control Objective 3, the 2ω0 components are effectively suppressed, decreasing from 21.869% to 1.586% in Ps and from 17.01% to 2.339% in Te.

Figure 13.

The FFT analysis results for Ps (a) before introducing Control Objective 3, (b) after introducing Control Objective 3.

Figure 14.

The FFT analysis results for Te (a) before introducing Control Objective 3, (b) after introducing Control Objective 3.

We set the second unbalanced scenario: at t = 16 s, the voltage sags to 0.9 p.u., while phase-A is raised to 1.1 p.u. The waveforms of DFIG-GESS PCC voltage, stator, and rotor currents, stator electromagnetic power, and electromagnetic torque under the unit value are shown in Figure 15. And Figure 16 shows the THD analysis of rotor current, and the harmonic (90 Hz, 110 Hz) of rotor current is effectively suppressed under the Control Objective 3, which reduces the rotor current THD from 22.75% to 1.78%.

Figure 15.

DFIG-GESS PCC voltage, stator, and rotor currents, stator electromagnetic power, and electromagnetic torque waveform at per-unit values when the voltage of phase A is raised to 1.1 p.u. (a) System waveform before introducing Control Objective 3. (b) System waveform after introducing Control Objective 3.

Figure 16.

The THD analysis results for ira when the voltage of phase A is raised to 1.1 p.u (a) before introducing Control Objective 3, (b) after introducing Control Objective 3.

4.2. AC Voltage Support at PCC

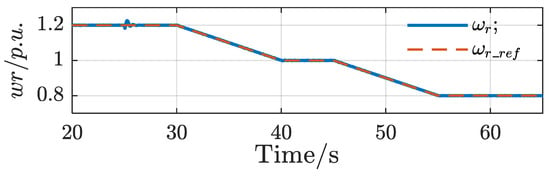

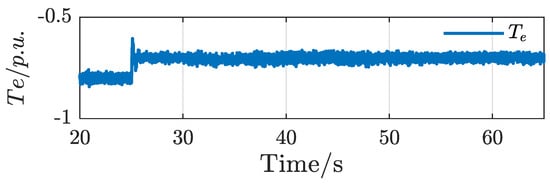

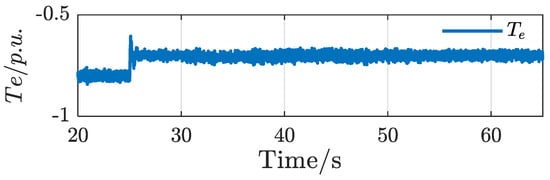

The rotor speed is set under the unbalanced grid as shown in Figure 17, where the orange dotted line (ωr_ref) is the unit value of the rotor speed under the unit value. The weight on the shaft of the DFIG-GESS is 0.8 p.u. before 60 s. Part of the weight input is cut off at 60 s and suddenly changes to 0.7 p.u. The corresponding electromagnetic torque of the system is shown in Figure 18. The blue solid line (ωr_ref) in Figure 17 is the actual value of the rotor speed under the unit value, which almost overlaps with the reference value of the speed. Only slight fluctuations occur when the weight is suddenly reduced, reflecting that the system has accurate control of the speed under the unbalanced grid.

Figure 17.

Waveform diagram of ωr under per-unit value.

Figure 18.

Waveform diagram of Te under per-unit value.

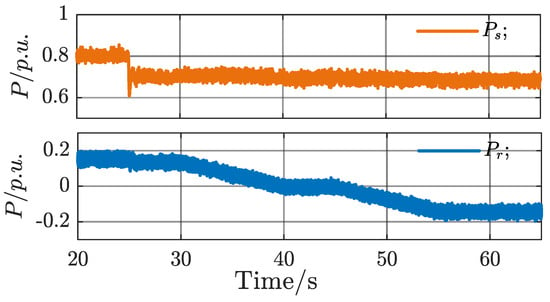

The power curve is drawn as shown in Figure 19. The orange line (Ps) is the stator electromagnetic power, which is directly fed into the grid through the stator side, does not change with the speed, and is proportional to the electromagnetic torque. The blue line (Pr) is the rotor electromagnetic power, which is fed into the grid through the AC-DC-AC converter and is related to the speed slip and electromagnetic power. Combined with Figure 17 and Figure 18, it can be seen that the active power fed into the grid of the system can be flexibly adjusted by adjusting the rotor speed and cutting the weight, so as to change the active power sent out by the power supply end and adjust the grid frequency while balancing the source load. As shown in Figure 20, the change trend of the grid frequency is similar to the total power fed into the grid of the system, and the grid frequency can be adjusted from 50.05 Hz at 20 s to 49.92 Hz at 65 s.

Figure 19.

Waveform diagram of active power under per-unit value.

Figure 20.

Waveform diagram of PCC frequency under per-unit value.

5. Conclusions

This work addresses the control requirements of DFIG–GESS under unbalanced grid conditions by developing a synchronous-dq model, revealing the twice-fundamental mechanisms in output power and electromagnetic torque and proposing a speed–grid-forming co-design framework. With precise speed regulation as the outer-loop objective, a stator-side voltage-source GFM together with 2ω suppression measures enables the integrated fulfillment of (i) closed-loop control of payload translation velocity, (ii) PCC-voltage support, (iii) mitigation of twice-fundamental harmonics. Compared with the wind-orientated, MPPT-centric paradigm, the presented scheme fuses the mechanical–electromagnetic coupling (pulley–drum–gearbox) with the variable-speed, constant-frequency capability of the DFIG, offering a transferable control pathway for energy-storage integration in unbalanced and weak grids. Our simulation shows clear quantitative gains. Under a weak grid (SCR = 3) and unbalanced (0.9 p.u. voltage sag) conditions, it validates the strategy, which reduces the rotor current THD from 12.57% to 1.71%.

Future work will pursue experimental and hardware-in-the-loop validation for parameter robustness and grid-code compliance, investigate optimal tuning under current-limiting synchronization coordination, and develop multi-device coordination strategies for high renewable penetration scenarios to further enhance engineering applicability and scalability.

Author Contributions

Software, J.D. and J.Z.; Formal analysis, D.H. and F.T.; Investigation, Y.L.; Data curation, J.Z.; Writing—original draft, Y.L. and D.H.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Project of State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd. grant number J2024225.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yan Li, Darui He, Jiao Dai, Jiaqi Zheng, and Fangyuan Tian were employed by the company State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Guo, H.; Wu, R.; Ma, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, Y.; Qi, B.; Gao, J.; Xu, C. Synergy-Payoff-Maximization-Based Rechargeable Adaptive Energy-Efficient Dual-Mode Data Gathering Using Renewable Energy Sources. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 35292–35305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qian, W.; Ye, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Long, Y.; Duan, M. A novel non-intrusive load monitoring method based on ResNet-seq2seq networks for energy disaggregation of distributed energy resources integrated with residential houses. Appl. Energy 2023, 349, 121703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Du, X.; Chen, T.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J. Capacity configuration of hybrid energy storage system for ocean renewables. J. Energy Storage 2025, 116, 116090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. Optimal Operation with Dynamic Partitioning Strategy for Centralized Shared Energy Storage Station with Integration of Large-scale Renewable Energy. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 12, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Li, P.; Dong, L. Simultaneous optimization of renewable energy and energy storage capacity with the hierarchical control. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 8, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, T.; Chen, T.; Hu, Q.; Chen, H.; Hu, X.; Jiang, Z. A high-resolution electric vehicle charging transaction dataset with multidimensional features in China. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zou, B.; Jin, X.; Luo, Y.; Song, M.; Ye, Y.; Hu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Zambroni, A.C. Mitigating power grid impact from proactive data center workload shifts: A coordinated scheduling strategy integrating synergistic traffic-data-power networks. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojetola, S.T.; Wold, J.; Trudnowski, D.J. Multi-Loop Transient Stability Control via Power Modulation From Energy Storage Devices. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 5153–5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, N.; Wang, X.; Kuang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Qian, T.; Zhao, H.; Hu, J. Day-Ahead Scheduling of a Gravity Energy Storage System Considering the Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, 12, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, L.; Shi, C.; Zhao, C. A Review of Gravity Energy Storage. Energies 2025, 18, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Liu, W.; He, H.; Chau, K.T. Health-conscious energy management for fuel cell vehicles: An integrated thermal management strategy for cabin and energy source systems. Energy 2025, 333, 137330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhou, J.; Jia, C.; Yi, F.; Zhang, C. Energy sources durability energy management for fuel cell hybrid electric bus based on deep reinforcement learning considering future terrain information. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Yi, F.; Hu, D.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J. Online optimization of energy management strategy for FCV control parameters considering dual power source lifespan decay synergy. Appl. Energy 2023, 348, 121516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, T.; Fang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H. A Power Shock Mitigation Method of Gravity Energy Storage System Based on Sliding Mode Control. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Electrical Energy Conversion Systems and Control (IEECSC), Shanghai, China, 8–10 November 2024; pp. 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xie, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, S.; Zhang, X. Analysis and Mitigation of Electromechanical Oscillations in Drivetrain for Hybrid Synchronization Control of DFIG-Based Wind Turbines. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 3002–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Time-Sequential Fault Current Limiting Method for Grid-Forming DFIGs in Compliance with Emerging Grid Codes. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2025, 40, 2228–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Hu, B.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, L.; Nian, H.; Qi, D. Transient Modeling and Postfault Stability Analysis of GFM-DFIG Considering Rotor-Side Current Limitation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 11979–11984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chang, Y.; Kocar, I. Grid-Forming Control of DFIG-Based Wind Turbine Generator by Using Internal Voltage Vectors for Asymmetrical Fault Ride-Through. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 2562–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhang, X. Improving Transient Stability of Grid-Forming DFIG Based on Enhanced Hybrid Synchronization Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 15881–15894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, D.; Zhao, C.; Gu, Z.; Nian, H. Enhanced Grid-Forming Control Strategy for DFIG Participating in Primary Frequency Regulation Based on Double-Layer MPC in Microgrid. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 2679–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, B.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Transient Stability Analysis Between Grid-Following DFIG-WT and Grid-Forming Converter in Electromechanical Timescale. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 2485–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, X. An Improved Strategy of Grid-Forming DFIG Based on Disturbance Rejection Stator Flux Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 2498–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Zheng, Z.; Ren, J.; Li, C.; Xie, Q. SMES Based Reconfigured Converter Architecture for DFIG to Enhance FRT and Grid Forming Capability. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 5402605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.; Liang, Z.; Chen, S.; Hu, Q.; Wu, Z. A tri-level demand response framework for EVCS flexibility enhancement in coupled power and transportation networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 16, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Qian, T.; Korkali, M.; Glatt, R.; Hu, Q. A Vehicle-to-Grid planning framework incorporating electric vehicle user equilibrium and distribution network flexibility enhancement. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Qian, T.; Shao, C.; Hu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zheng, J. A Strategic EV Charging Networks Planning Framework for Intercity Highway with Time-Expanded User Equilibrium. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.; Fang, M.; Hu, Q.; Shao, C.; Zheng, J. V2Sim: An Open-Source Microscopic V2G Simulation Platform in Urban Power and Transportation Network. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 3167–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghennam, T.; Berkouk, E.; Francois, B. Modeling and control of a doubly fed induction generator (DFIG) based wind conversion system. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Power Engineering, Energy and Electrical Drives, Lisbon, Portugal, 18–20 March 2009; pp. 507–512. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).