Abstract

Federated learning has won a lot of interest in recent years, due to its capability in collaborative learning and privacy preservation. To ensure the accuracy of outsourced training tasks, task publishers prefer to assign tasks to task workers with a high reputation. However, existing reputation-based incentive mechanisms assume that task publishers are honest, and only task workers would probably behave dishonestly to pollute the federated learning model. Different from existing work, we argue that task publishers would also behave dishonestly, where they would benefit from colluding with task workers to help task workers obtain a high reputation. In this paper, we propose a collusion-resistant and reliable incentive mechanism for federated learning. First, to measure the credibility of both task publishers and task workers, we devise a novel metric named reliability. Second, we devise a new method to compute the task publisher reliability, which is obtained by computing the deviation of reputation scores given by different task publishers, i.e., low reliability is assigned to a task publisher once its deviation is far away from that of other publishers. Third, we propose a bidirectional reputation calculation method based on the basic uncertain information model to compute reputation and reputation reliability for task workers. Furthermore, by integrating an incentive mechanism, our proposed scheme not only effectively defends against collusion attacks but also ensures that only task workers with high reputation, reputation reliability, and the capability to accomplish complex tasks can win a high reward. Finally, we conduct extensive experiments to verify the efficiency and efficacy of our proposed schemes. The results demonstrate that our proposed schemes are not only collusion-resistant but also achieve 6.31% higher test accuracy compared with the state of the art on the MNIST dataset.

1. Introduction

To address the challenge of the potential data breaches in centralized learning [1], federated learning (FL) has been introduced as a viable solution [2]. Unlike centralized learning, FL requires only the transmission of gradients from task workers to the task publisher, rather than the local data [3,4,5]. This not only mitigates the issue of data breaches but also reduces communication and storage costs [6].

Despite FL bringing us a lot of benefits, it also faces two main challenges. First, task workers require considerable computation and communication consumption for model training. Without an effective incentive mechanism, task workers would be unwilling to participate [7,8]. Second, malicious task workers would try to pollute global models by providing poisoned local models [9,10,11]. Without an efficient mechanism for selecting reliable and high-quality task workers, task publishers would receive a final model without guaranteed accuracy. To solve these two challenges, Kang et al. [6] proposed an optimization approach based on reputation and contract theory, which selects high-quality task workers with high reputations to participate in the FL task. Other studies [12,13,14,15,16,17,18] have deeply explored this field, and have proposed various reputation-based incentive mechanisms to establish a more reliable FL environment.

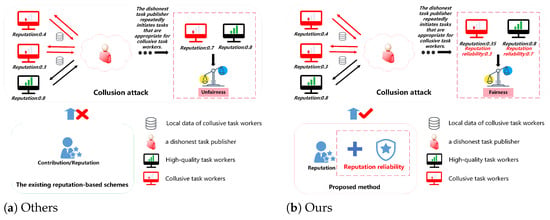

However, existing reputation-based incentive mechanisms assume that task publishers are honest [19,20,21,22], and only task workers would probably behave dishonestly to pollute the FL model. Different from existing work, we argue that task publishers would also behave dishonestly [23], where they would benefit from colluding with task workers to help task workers obtain a high reputation. As demonstrated in Figure 1, collusive task workers privately send their local data to the dishonest task publisher. Then, based on the local data received, the dishonest task publisher repeatedly initiates tasks that are appropriate for collusive task workers. By continuing to participate in these tailor-made tasks, collusive task workers can pretend to be high-quality workers with a forged high reputation score. These mechanisms lack the ability to audit the behavior of task publishers or detect abnormal task patterns, making them inherently vulnerable to such collusion attacks. Therefore, it is imperative to devise a collusion-resistant and reliable incentive mechanism in FL.

Figure 1.

The existing reputation-based schemes vs. BRCM.

Defending against collusion attacks has three main challenges: First, how to evaluate the reliability of both task publishers and task workers accurately? Second, when some dishonest task publishers collude with collusive task workers, how can a distinguishable reputation and reputation reliability be computed for all task workers? Third, how to devise an incentive mechanism to motivate task workers with both a high reputation and capability to participate in training?

In this paper, we propose a collusion-resistant and reliable incentive mechanism for FL. First, to measure the credibility of both task publishers and task workers, we devise a novel metric named reliability. Second, we devise a new method to compute the publisher reliability, which is obtained by computing the deviation of reputation scores given by different task publishers, i.e., low reliability is assigned to a publisher once its deviation is far away from that of other publishers. Third, we propose a bidirectional reputation calculation method (BRCM) based on the basic uncertain information model to compute reputation and reputation reliability for task workers. Specifically, we employ the multi-weight subjective logic model [6,24] to assign reputations, including the historical performance of the task workers (direct reputation) and their performance in other tasks (indirect reputation), to task workers. Based on the reliability of the task publishers and the comprehensive reputation of the task workers, we adopt the basic uncertain information (BUI) aggregation model [25,26] to compute the final reputation and reputation reliability of task workers. Furthermore, by integrating an incentive mechanism, our proposed scheme not only effectively defends against collusion attacks but also ensures that only task workers with high reputations and reputation reliability can win high rewards. Finally, we conduct extensive experiments to verify the efficiency and efficacy of our proposed schemes. The results demonstrate that our proposed schemes are not only collusion-resistant but also achieve 6.31% higher training accuracy compared with the state of the art on the MNIST dataset.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We propose a novel collusion-resistant incentive mechanism for federated learning that integrates reputation, reputation reliability, and task complexity, ensuring that only task workers with high reputation, strong reliability, and high capability are rewarded.

- We devise a novel metric named reliability to measure the credibility of both task publishers and task workers.

- We propose the BRCM based on the basic uncertain information model to compute reputation and reputation reliability for task workers.

- We conduct extensive experiments to verify the efficiency and efficacy of our proposed schemes. The results demonstrate that our proposed schemes are not only collusion-resistant but also achieve 6.31% higher test accuracy compared with the state of the art on the MNIST dataset.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 presents related work, and Section 3 introduces the preliminaries. Section 4 outlines the specific process of our proposed scheme. Section 5.1 details the computational process of BRCM. Section 5.2 introduces the collusion-resistant and reliable incentive mechanism. Performance evaluation is conducted in Section 6. The limitations of the proposed model and directions for future work are discussed in Section 7, and Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

In FL, the design of incentive mechanisms plays a crucial role in ensuring the enthusiasm of task workers and the overall performance of the system. The development of incentive mechanisms has been mainly focused on contract theory, reverse auction, auction, deep reinforcement learning, and the Stackelberg game. Specifically, contract theory [27,28,29] tailors differentiated contracts for task workers with varying data quality and computational resources, where the optimal reward can only be achieved when a task worker selects a contract that matches their profile. In the reverse auction mechanism [30], task publishers (bidders) specify task requirements and corresponding rewards to attract task workers (auctioneers) to bid. The system then selects the most suitable participants based on their bids and the quality requirements. Conversely, in the auction [31], task workers (bidders) provide resources (such as computational power and bandwidth) to attract task publishers (auctioneers) to select them for task training. However, these methods are mostly designed for static environments and fail to fully adapt to dynamically changing conditions. The incentive mechanism based on deep reinforcement learning [32] addresses this issue effectively by adjusting the incentive strategy in real time to adapt to environmental changes, thereby optimizing the overall system performance. Nonetheless, a common challenge with this approach is the extensive time and computational resources required for training. In the Stackelberg game [33,34] incentive mechanism, as a task publisher, it is necessary to optimize the incentive strategy while predicting the optimal response of the task workers, aiming to maximize the interests of both parties. Notably, the aforementioned incentive mechanisms have not fully considered the potential risks posed by malicious and low-quality task workers to the incentive mechanisms.

Considering device selection and incentive mechanisms together can effectively address this issue. Kang et al. [12] reduced the detrimental impacts of malicious task workers and low-quality task workers by devising the multi-weight subjective logic model. This model dynamically adjusts reputation based on the performance of task workers in tasks. Moreover, they integrated reputation with contract theory to propose an incentive mechanism aimed at encouraging high-quality contributions [6]. Gao et al. [17] combined contribution and reputation to determine the reward for task workers, where contributions reflect immediate utility and reputation indicates trustworthiness over time. Zhang et al. [18,35,36,37] proposed the integration of reverse auctions with reputation as a strategy to attract a greater number of high-quality task workers to participate in FL tasks. Wherein Zheng et al. [18] utilize reputation and efficiency values for selecting task workers for training, where reputation reflects historical performance and efficiency values indicate computational power and dataset size.

Furthermore, to defend against attacks by free-riders and malicious task workers, Xu et al. [13] employed a reputation-based scheme that evaluates task workers’ credibility by comparing the similarity between task workers’ model updates and the aggregated global model. Similarly, Song et al. [14] proposed a secure FL framework to defend against data poisoning attacks. It distinguishes positive behaviors from negative behaviors by local model impact on the global model to dynamically adjust reputation. Wang et al. [15] assigned reputation to task workers based on the performance of local models and assigned aggregated weights to local models based on reputation. Ur et al. [16] proposed a blockchain-based reputation-aware fine-grained FL to ensure authenticity, traceability, trustworthy and fairness.

In addition, Smith et al. [38] proposed a federated multi-task learning framework (MOCHA) to address the heterogeneity among multiple participants, which provides theoretical support for multi-party and dynamic-role settings in federated learning. The existing reputation-based FL methods all allocate reputation based on the performance of task workers during task completion. These methods not only motivate high-quality task workers to actively participate in tasks but also effectively defend against attacks [39] from task workers, providing a reliable and fair FL. However, these methods are based on the assumption that task publishers are all honest. This assumption overlooks the potential for collusion between dishonest task publishers and collusive task workers. However, collusion between both parties will seriously undermine the fairness and reliability of FL. As a result, it is crucial to propose an innovative solution capable of detecting collusion attacks, as well as to stimulate the participation of high-quality task workers through the equitable distribution of rewards and the establishment of a secure and reliable environment. Table 1 summarizes the above methods.

Table 1.

Summary of representative incentive mechanisms in federated learning.

3. Preliminaries

This section presents an overview of the foundational knowledge of FL and the adversary model.

3.1. Federated Learning

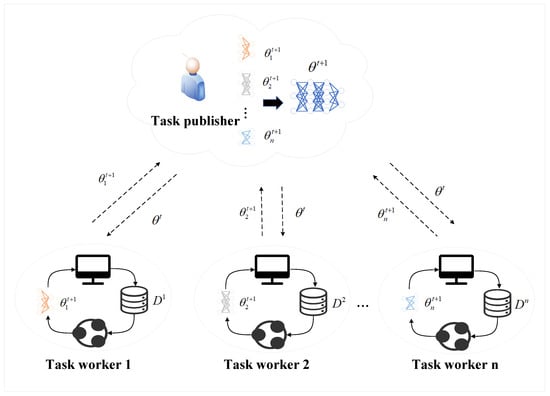

FL is a distributed machine learning approach that facilitates collaborative model training across multiple nodes (i.e., task workers), ensuring all training data remains on local devices [40]. This can preserve data privacy [41], given that it eliminates the need for centralized data storage or sharing and effectively harnesses data resources that are geographically dispersed [42], as follows Figure 2. A comprehensive depiction of all roles mentioned in the paper is provided in Table 2.

Figure 2.

The framework of FL.

Table 2.

Roles in the paper.

FL allows task publishers to construct a high-performance model in the context of insufficient local data. Specifically, the task publisher initiates a task through FL and extends invitations to task workers possessing relevant local data. These task workers decide whether to join the task based on their resource capabilities and data. The task publisher then takes into account multiple criteria, including the variety in the task workers’ data and their computational and communication power, when choosing task workers for the task. Subsequently, the initial global model is transmitted to task workers selected. Each task worker then trains independently model training using their local dataset and calculates gradients locally for the loss function , as follows:

where is the learning rate, and t is the current training round [43].

Subsequently, they transmit local models to the task publisher rather than the original data to minimize communication costs and enhance privacy protection. The task publisher aggregates all the received local models and updates the global model [44], as follows:

where J is the number of participating task workers.

The process of updating and evaluating the global model in FL is an iterative cycle until model performance indicators are satisfied or the maximum number of iterations is reached. Through the collaboration of data from all tasked workers, the task publisher obtains a robust global model. This process effectively uses data resources dispersed among different participants without leaking the privacy of individual data.

3.2. Adversary Model

In reputation-based FL, reputation serves to evaluate the trustworthiness of task workers; task workers with higher reputations have more chances to participate in future tasks. However, when collusive task workers collude with dishonest task publishers, a mechanism can be devised to destroy this assessment. Specifically, collusive task workers may share their private local data with task publishers. Then, unreliable publishers design tasks tailored to the local data of these task workers to make collusive task workers complete them flawlessly, thus “legitimately” enhancing their reputation. If the unreliable publisher repeats tailored tasks, the collusive worker’s reputation will continually rise to give them more opportunities to take part in future tasks and accrue more rewards. Such collusion increases the training time and compromises the model’s accuracy. Moreover, it destroys the system’s integrity, denying honest task workers, who truly provide high-quality work, their due incentives and diminishing their motivation to take part in future tasks, as shown in Figure 1. Consequently, there is an urgent need for a method to defend against collusion attacks to ensure the reliability of FL.

4. Reputation-Based Task Worker Selection Scheme

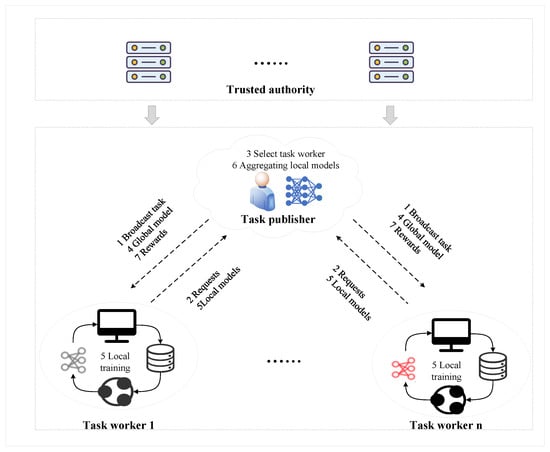

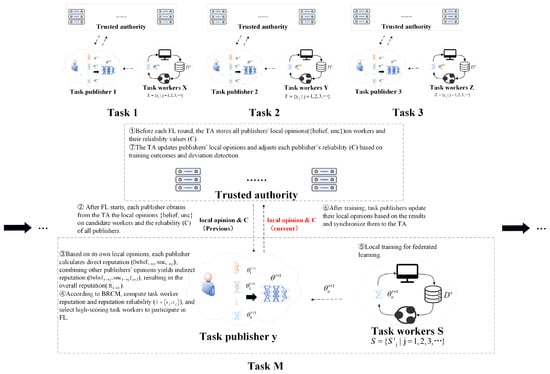

To address collusion attacks, we propose BRCM, which assigns reputation reliability to each task worker. Task publishers can prevent the participation of collusive task workers by setting a threshold for reputation and reputation reliability. The overall framework is illustrated in Figure 3, building on the overall framework shown in Figure 3, we have added Figure 4 to clearly illustrate the communication flow between task workers, task publishers, and the Trusted Authority (TA) in one iteration of federated learning. The specific details are as follows:

Figure 3.

The overall framework for our proposed scheme in FL.

Figure 4.

Communication flow between task workers, task publishers, and TA in one iteration of federated learning. Since there are multiple task publishers, each task involves a distinct set of task workers. In each training round, the publishers and workers interact following the illustrated process until all rounds of training for the corresponding task are completed.

- Step 1: Broadcasting Tasks and Sending Requests: The task publisher initiates tasks based on their model requirements. Send task requests to task workers, including the task worker’s resource requirements (computing resources and communication resources). Task workers who are idle and meet these resource requirements become candidate task workers by sending requests to join the task.

- Step 2: Selection of Task Workers: Firstly, the task publisher employs the improved multi-weight subjective logic model to compute the comprehensive reputation of each candidate task worker. This needs to use both direct reputation opinions and indirect reputation opinions stored in TA. Then, the BUI aggregation model obtains the reputation of the task worker and the reputation reliability based on the comprehensive reputation of the task worker and the reliability of the task publisher in TA. Finally, task publishers select reliable and high-quality task workers to participate in tasks by setting thresholds. More detailed information on reputation and reputation reliability will be introduced in Section 5.1.

- Step 3: Local Model Training: The task publisher distributes an initial global model to selected high-quality task workers. These task workers then conduct several iterations of local training using their local datasets. Upon completion, the resulting local models are transmitted back to the task publishers.

- Step 4: Model Aggregation: In this phase, the task publisher utilizes an aggregation algorithm, like federated averaging, to aggregate the local models received from task workers into an updated global model. The global model is then redistributed to the task workers for a subsequent round of training. The repetition of Steps 3 and 4 continues until the global model satisfies the predetermined accuracy criteria.

- Step 5: Reputation and Reliability Update: After the completion of a task, the direct reputation of task workers and the reliability of task publishers within the TA are updated based on their performance in the current round. On the one hand, the direct reputation of task workers is determined by the task publishers, based on the count of positive and negative events associated with each worker during the task. On the other hand, assessing the reliability of task publishers begins by comparing the gap between the direct reputation given to collusive task workers by a task publisher and the reputations provided by other task publishers. A significant deviation beyond a set threshold suggests the potential unreliability of the task publisher. The suspicious task publisher is then evaluated further based on two key aspects: the task publisher’s tendency to assign unrealistically high reputations, and the frequency of interaction with collusive task workers. Conversely, if the discrepancy is below the threshold, it indicates a lack of suspicion regarding the unreliability of the task publisher, and therefore, there is no need to update the task publisher’s reliability. This ensures a comprehensive and accurate update of reputations and reliability in TA.

- Step 6: Distribution of Rewards: Finally, task publishers will determine the allocation of rewards based on the performance of task workers during the execution of tasks. Task workers’ reputation, the contributions of computational resources, and communication resources are comprehensively considered as key factors in determining rewards. Reputation not only directly influences the allocation of rewards but also indirectly affects the incentive mechanism. For instance, by setting a reputation threshold, task workers with high reputations are provided with more opportunities to participate in future tasks to obtain more rewards over time. Such a strategy is aimed at encouraging and rewarding task workers who provide high-quality work.

5. Methodology

5.1. Reputation Calculation Using BUI Aggregation Model

In FL, it is crucial to defend against collusion between dishonest task publishers and collusive task workers and to select high-quality task workers for training. In this section, we introduce BRCM defense against collusion attacks in detail. Specifically, we firstly adopt the multi-weight subjective logic model proposed in previous research [6,24], which integrates both direct and indirect reputations to obtain a comprehensive reputation score. Among these, both direct and indirect reputations are stored within TA. Moreover, the TA decides whether to update the task publisher’s reliability by monitoring the task publisher’s behavior in this task. Finally, we use the BUI aggregation model to objectively evaluate task workers’ final reputation and reputation reliability to more accurately represent reputation information. This comprehensive assessment creates a secure and fair framework that effectively motivates high-quality task workers to actively participate in FL tasks.

5.1.1. Task Worker Comprehensive Reputation Calculation

Direct Reputation Calculation

In the multi-weight subjective logic model, direct reputation refers to the historical reputation opinions of task worker j assigned by task publisher i, based on the performance of task worker j in past tasks. The direct reputation is computed based on a local opinion, denoted as {} [24]. Specifically, is computed as

Here, and are the number of positive events and negative events (e.g., low-quality model, model transmission error), respectively. and are the weights assigned to and , respectively. To suppress the value of when task worker j is correlated with negative events, is set with a higher value compared with [6]. Additionally, , i.e., uncertainty, denotes the probability of transmission failures between task worker j and task publisher i.

Finally, direct reputation is computed based on belief and uncertainty, namely , where represents the weight of uncertainty on reputation.

Indirect Reputation Calculation

Indirect reputation refers to the historical reputation opinions of task worker j assigned by other task publishers Y, based on the performance of task worker j in past tasks. The indirect reputation is denoted as , where . is computed as

Meanwhile, is computed as

Here, represents the similarity between task publishers i and y, which serves as a weight to adjust the influence of each publisher’s opinion in the aggregation process. To accurately assess this similarity, we adopt an amendatory cosine similarity function [24], which evaluates the consistency of reputation assessments provided by different task publishers. When aggregating indirect reputation opinions from multiple publishers, the amendatory cosine similarity between publishers i and y is calculated as

where and are the direct reputation opinions, and are their mean values, and denotes the set of common task workers shared by both publishers. Finally, the overall similarity weight is expressed as

where is a scaling factor used to adjust the relative importance of the similarity measure.

Comprehensive Reputation Calculation

To enhance the accuracy of reputation, the comprehensive reputation opinion {} integrates both local and global opinions, and is computed based on the aforementioned direct and indirect reputations. Specifically, the comprehensive reputation is computed with three steps. First, compute an integrated value of .

Second, compute an integrated value of .

Finally, compute the comprehensive reputation opinion based on and with the following equation:

5.1.2. Task Publisher Reliability Calculation

In FL, dishonest task publishers might collude with collusive task workers for additional profits, which compromises the fairness of the system. Existing reputation-based schemes tend to focus on the performance of task workers, often overlooking the reliability of task publishers, thereby assuming that all reputations provided are reliable. To address this issue, we introduce a reliability metric for task publishers, offering a real-time reflection of the credibility of the reputations they provide.

In cases of collusion, task publishers may assign higher reputation scores to collusive task workers compared to honest task workers. To detect such anomalies, we compare the direct reputation provided to task worker j by task publisher i with the average direct reputation given by other task publishers Y. This aids in identifying a set of potentially collusive task workers, as follows:

Here, Y is the set of other task publishers with a size of . If the discrepancy exceeds a predefined threshold, denoted as , this indicates a high probability that task worker j is a collusive task worker.

After assessing all task workers, if the set of suspicious collusive task workers J is empty, it suggests that the task publisher is not involved in collusion. In this case, there is no need to update its reliability in the TA. Conversely, if the set J is not empty, further observation is required to determine whether the task publisher is unreliable. The reliability of task publisher i is then updated as follows:

where and are weighting coefficients that determine the importance of each behavioral indicator, and . A larger value of or corresponds to a stronger indication of dishonest behavior, resulting in a smaller . When falls below a threshold , the task publisher is regarded as unreliable, and its corresponding weight in the subsequent reputation aggregation process is reduced or ignored. At this stage, the two main factors that affect are the publisher’s tendency to assign unrealistically high scores () and its interaction frequency with collusive task workers (). The meanings and computation of these two indicators are described in detail below.

The rating tendency reflects the extent to which a task publisher assigns high reputation values to collusive task workers and is expressed as

Here, J denotes the set of collusive task workers identified through the deviation test, and is the number of task workers in the set. If is smaller than the given threshold, it indicates that task publisher i has a high tendency to favor collusive workers and can thus be considered dishonest.

The interaction frequency measures how frequently a task publisher interacts with collusive task workers. It is defined as

where represents the number of interactions between task publisher i and collusive task worker j, and is the total number of interactions between publisher i and all task workers. A larger indicates that the task publisher frequently collaborates with collusive workers, which reduces its reliability .

The significance of each factor is determined by their respective weights, for and for . Upon task completion, the task publisher’s credibility score is updated in the TA. This dynamic mechanism enables the system to detect and gradually suppress dishonest publishers, thereby ensuring the fairness and robustness of the federated learning framework.

5.2. Incentive Mechanism Based on Reputation Scheme

FL aims to ensure data security and uphold user privacy; however, its effectiveness largely depends on incentive mechanisms. Inadequate detection of collusion attacks within FL can lead to an inadvertent selection of collusive task workers for subsequent tasks. This can result in collusive task workers receiving more rewards. Such disparities undermine the motivation of high-quality task workers. BRCM can effectively defend against collusion attacks. Assigning low reputation and reputation reliability to collusive task workers and publishers can robustly suppress collusive behaviors. Furthermore, integrating reputation and reputation reliability assessments generated by BRCM into the incentive structure can not only provide task workers with a collusion-resistant and reliable FL environment but also improve the motivation for high-quality task workers to participate.

5.2.1. An Example

FMore [45] is a lightweight multi-dimensional auction model that enhances the overall performance of FL by incentivizing more high-quality task workers to participate at a low cost. Specifically, the model requires candidate task workers to submit resource vectors and expected rewards to the task publisher. Subsequently, the task publisher selects the top K task workers as task participants based on the scoring rules.

Although FMore has achieved success in incentivizing high-quality task workers to participate in tasks, it is ineffective in defending against attacks from malicious task workers. For instance, low-quality task workers (with limited data volume and data types) may inflate their data volume and data types to bid for tasks, thereby illegally obtaining participation opportunities. This behavior severely undermines the fairness of FL, reduces the motivation of high-quality task workers, and decreases the accuracy of the model. To defend against the attack, incorporating a reputation into FMore is a viable option. Malicious or low-quality task workers, due to their poor data quality, insufficient computational resources, or unstable training results, would be assigned low reputations, thereby being restricted or denied participation in subsequent training tasks. However, relying solely on a reputation is insufficient to fully defend against more complex malicious behaviors, such as collusion attacks. Therefore, integrating BRCM with FMore is crucial. The following is a brief process of FMore combined with BRCM:

- Step 1: Publish Tasks and Scoring Rules: The task publisher releases an FL task, clearly specifying the task requirements and objectives, including the required training data volume and bandwidth resources. Additionally, the task publisher will announce the scoring rules (as shown in (15)), where represents the data volume, represents the data types, represents the computational resources, represents the bandwidth, p represents the task worker’s expected rewards, and , , , and are the corresponding weights for , , , and , respectively.

- Step 2: Bidding: Task workers interested in participating in the task submit their bids based on the task requirements, providing their resource vectors (r) and the corresponding expected rewards (p).

- Step 3: Select Task Workers: After receiving participation requests from a set of candidate task workers , the task publisher first obtains from the TA not only the reputations of the task workers but also the reliability scores of all relevant task publishers, including its own, since these values are required for fair and accurate trust evaluation. Subsequently, the task publisher calculates the reputation and reputation reliability of task workers based on BRCM. Furthermore, the task publisher selects the set of reliable and reputable task workers by setting the reputation threshold and reputation reliability threshold . Finally, the task publisher selects the top K workers in as task participants according to the scoring rules and sends the global model to the selected participants.

- Step 4: Train Local Model: After receiving the global model, the selected task worker uses its local data and computing resources to train the local model.

- Step 5: Update the Global Model: The task publisher collects all local models from the task workers and aggregates these local models to update the global model. The updated global model is then fed back to all participating task workers for use in the next round of training.

- Step 6: Complete the Task: Repeat Steps 2 through 6 until the global model reaches the predetermined accuracy target. Finally, TA updates reputation and reliability based on the performance of the task workers and task publishers in that round, respectively.

- Step 7: Distribute Rewards: Reward Distribution: The task publisher allocates rewards based on the scores of the task workers, incentivizing nodes to continuously participate and provide high-quality resources.

The combination ensures that high-quality task workers are more likely to be selected for future tasks. As these task workers accrue rewards over successive engagements, a positive feedback loop is engendered, enhancing their motivation. In contrast, the participation of malicious and low-quality task workers is effectively impeded, safeguarding the integrity of FL outcomes and exerting a deterrent effect on malicious and low-quality task workers. This not only mitigates potential threats to the FL process but also motivates all task workers to elevate their reputation and reputation reliability.

5.2.2. Analysis

Although the proposed reputation scheme effectively mitigates collusion attacks, it encounters a challenge: task workers with high reputations but insufficient capabilities to handle complex tasks may unfairly suffer reputation loss due to poor performance on such tasks. To address this issue, we have refined and supplemented the original reputation scheme. Initially, we introduce an assumption that each task worker possesses a self-assessed task complexity index, which measures their ability to handle tasks. Concurrently, each task is assigned a specific complexity level. Moreover, when task publishers issue tasks, they are required to not only specify the resource requirements but also indicate the task’s complexity coefficient. This approach ensures that task workers with lower complexity indices are not selected for tasks of higher complexity. It is noteworthy that to prevent task workers with lower complexity indices from masquerading as capable of handling higher complexity tasks for additional rewards, our scheme effectively counters this behavior by reducing their reputation. This adjustment mechanism aims to maintain the fairness and integrity of the task allocation process.

6. Performance Evaluation

6.1. Dataset

In this subsection, we describe the datasets used in this study. Two widely recognized benchmark datasets, MNIST and CIFAR-10, were employed to validate the effectiveness and generalization capability of the proposed scheme under different data characteristics. These datasets were selected because they represent two distinct visual learning scenarios: MNIST provides a simple, low-dimensional grayscale digit recognition task, whereas CIFAR-10 offers a more complex, high-dimensional color image classification challenge. It contains a total of 70,000 images of handwritten digits ranging from 0 to 9. Each image is a grayscale sample of size pixels, centered and size-normalized to ensure consistency. Among these, 60,000 samples are used for model training and 10,000 samples for testing. Due to its low noise level and balanced class distribution, MNIST serves as a standard benchmark for evaluating the convergence and robustness of machine learning and federated learning algorithms.

The CIFAR-10 dataset consists of 60,000 natural RGB images of size , evenly categorized into 10 classes that include both animals (such as cats, dogs, and birds) and vehicles (such as airplanes, cars, and ships). Of these, 50,000 images are used for training and 10,000 for testing. Compared with MNIST, CIFAR-10 is more challenging because it involves color variations, complex textures, and inter-class similarities, making it suitable for testing the scalability and stability of the proposed model under diverse data distributions.

A summary of the two datasets, including their image size, class composition, and data split ratio, is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the datasets used in experiments.

6.2. Simulation Setting

In this subsection, we present the experimental configuration used to evaluate the proposed scheme. The experiments involve a federated learning environment comprising diverse participants: 50 task workers (including 5 collusive task workers, 15 normal low-quality task workers, and 30 high-quality task workers) and 10 task publishers (including 2 dishonest task publishers and 8 honest task publishers). Low-quality task workers possess only three classes of data, while high-quality task workers have datasets covering all classes. Collusive task workers cooperate with dishonest task publishers to gain unfair advantages.

During the experiment, task workers updated their local models using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), and task publishers performed global aggregation using the FedAvg algorithm. Detailed simulation parameters are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parameter setting in the simulation.

6.3. Experiments

We validate the effectiveness of the proposed scheme through a series of detailed experiments. First, in experiment 1, we discuss the impact of low-quality task workers on FL systems. Subsequently, experiments 2, 3, and 4 test the feasibility of BRCM in defending against collusion attacks and compare it with the multi-weight subjective logic model. Experiment 5 is dedicated to validating the adaptability of BRCM across various levels of collusion, demonstrating whether the proposed scheme has robustness in addressing the challenges of collusion attacks. Lastly, validate the feasibility of applying BRCM to incentive mechanisms (e.g., FMore) through experiment 6.

6.3.1. Experiment 1

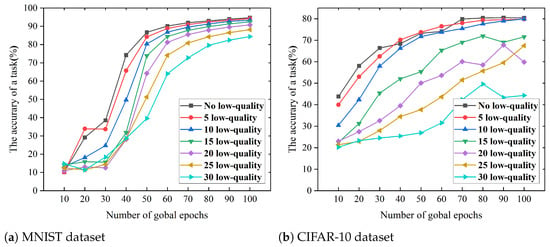

To evaluate the influence of low-quality task workers on the training dynamics of FL models, this study meticulously structured seven distinct experimental scenarios. These scenarios ranged from a baseline with no low-quality task workers to configurations including 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 low-quality task workers to capture the hierarchical impact of different numbers of low-quality task workers on the learning process. As illustrated in Figure 5, an obvious trend was observed: The participation of more low-quality task workers in a task proportionally reduces the accuracy of the model. This phenomenon highlights the detrimental effect of low-quality task workers on FL, emphasizing the importance of mitigating the influence of collusion attacks. For instance, in a scenario of no low-quality task workers, the accuracy of training models using MNIST and CIFAR-10 databases reached peaks of 94.69% and 80.53%, respectively. However, when the model was trained with the participation of 30 low-quality task workers, its accuracy sharply decreased to only 84.36% and 49.61%, respectively, marking a significant compromise in performance.

Figure 5.

The accuracy of a task under different numbers of low-quality task workers.

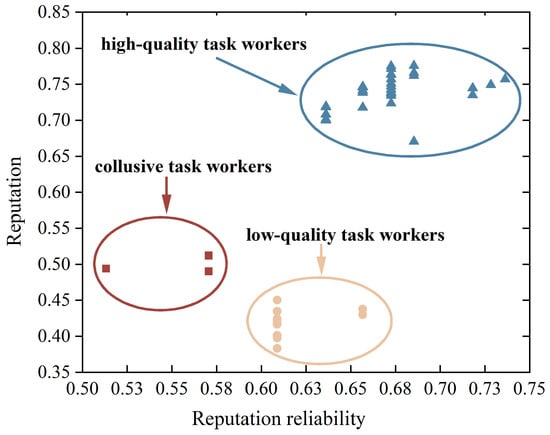

6.3.2. Experiment 2

In order to better validate our proposed scheme, we added a warm-up phase in the simulation experiment. The warm-up phase consists of ten rounds, with each of the 10 task publishers initiating one round of tasks. After the warm-up phase (in the 11th round), use BRCM to calculate the reputation value of candidate task workers and select high-quality task workers by setting thresholds. Figure 6 shows that when collusive task workers collude with dishonest task publishers, the reputation reliability of collusive task workers is 0.57, which is lower than that of normal low-quality and high-quality task workers. This is because reputation reliability is aggregated by the reliability of the publishers participating in the task. Collusive task workers will frequently interact with dishonest task publishers, so their reputation reliability will be very low. In addition, the reputation of high-quality task workers is much greater than that of malicious and normal low-quality task workers, but the reputation value of collusive task workers is slightly higher than that of normal low-quality task workers. The reason is that in the experiment, we set the reputation value given by dishonest task publishers to affect the final reputation with a weight of 0.2. Consequently, task publishers can enhance the efficiency and fairness of the training process by setting thresholds for reputation and reputation reliability. Our proposed scheme effectively filters out collusive pseudo-high-reputation task workers and selects reliable and high-quality task workers for participation.

Figure 6.

Reputation and reputation reliability of task workers in collusion attacks.

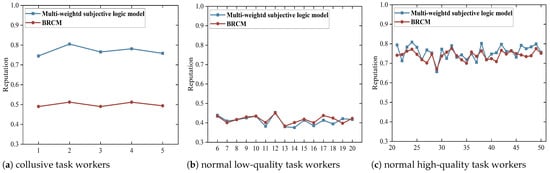

6.3.3. Experiment 3

To substantiate the effectiveness of BRCM further, we conducted a comparative analysis of the reputation metrics between our proposed scheme and the multi-weight subjective logic model. As illustrated in Figure 7, under scenarios involving collusion between collusive task workers and unreliable publishers, the proposed scheme discernibly demarcates the reputation of collusive task workers (1–5) as lower than that determined by the multi-weight subjective logic model. The reputation of normal low-quality (6–20) and high-quality (21–50) task workers remains comparably consistent with those derived from the multi-weight subjective logic model. For instance, the reputation scores assigned to collusive task workers by the multi-weight subjective logic model and our method are 0.75 and 0.49, respectively. This discrepancy stems from the fact that the multi-weight subjective logic model overlooks the reliability of task publishers, presuming all to be trustworthy. In contrast, our method effectively defends against the collusion attack by diminishing the weight of the reputation that dishonest task publishers allocated to collusive task workers. Given the prevalence of collusion attacks in FL, our proposed scheme demonstrates enhanced suitability for device selection within this domain, offering a more robust and discerning approach than the multi-weight subjective logic mode.

Figure 7.

Reputation values of task workers.

6.3.4. Experiment 4

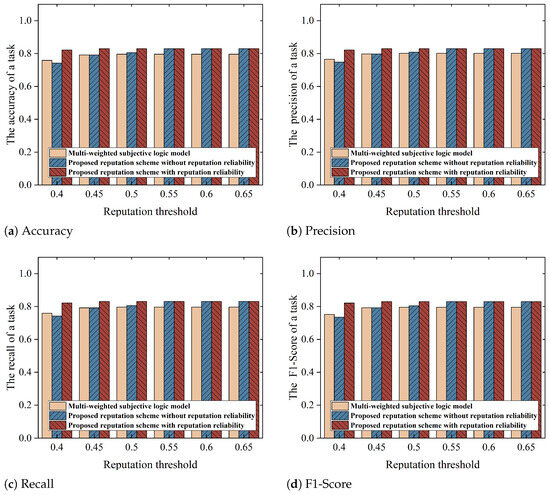

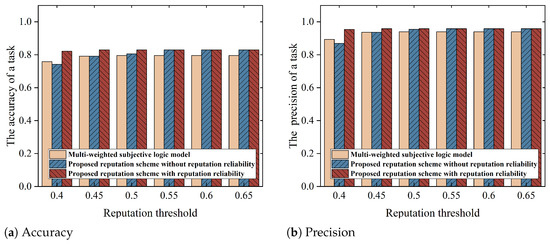

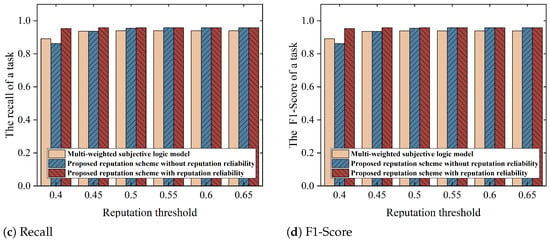

To explore the impact of threshold settings on the accuracy of an FL task, our study tested the accuracy of the model for different schemes under a variety of threshold conditions. In this experiment, we employed the hold-out cross-validation method, where the MNIST dataset with 60,000 training images was randomly divided into 80% training data (48,000 images) and 20% testing data (12,000 images) to evaluate the generalization performance of the federated learning model. Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 illustrate that setting reputation and reputation reliability thresholds reasonably in the proposed scheme can improve the accuracy of FL tasks.

Figure 8.

Model accuracy under various reputation thresholds on the MNIST dataset (the threshold for reputation reliability is 0.61).

Figure 9.

Model accuracy under various reputation thresholds on the CIFAR-10 dataset (the threshold for reputation reliability is 0.61).

Figure 10.

Model accuracy under different threshold for reputation reliability (the threshold of reputation is 0.4).

Specifically, when the threshold exceeds 0.5, the accuracy of the model under our proposed reputation scheme without reputation reliability is higher than the scheme utilizing a multi-weight subjective logic model. The difference stems from the fact that the multi-weight subjective logic model is unable to defend against collusion attacks. It will be influenced by false high praise provided by dishonest task publishers to collusive task workers to mistakenly choose collusive task workers to participate in the task. In contrast, our reputation scheme without reputation reliability effectively diminishes the weight of unreliable reputations through the use of a BUI aggregation model, creating a more authentic and precise system of reputation assessment for task workers. Furthermore, when the reputation threshold is set at 0.4, both our reputation scheme without reputation reliability and the multi-weight subjective logic model are unable to prevent collusion attacks, as all task workers (collusive, normal low-quality, and high-quality task workers) have reputations exceeding the threshold. However, in our reputation scheme with reputation reliability, when the reputation threshold is kept at 0.4 and the reputation reliability threshold is set at 0.59 or higher, the accuracy of the model significantly improves further. This is because setting a high threshold for reputation reliability can effectively prevent collusive task workers from being selected. So, introducing the reputation reliability threshold effectively filters out collusive task workers and enhances the model’s performance.

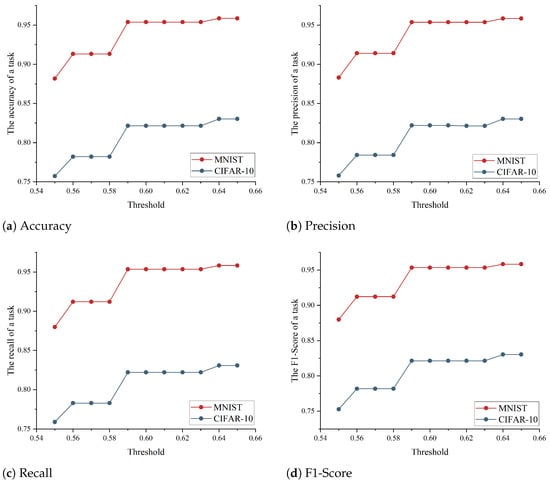

6.3.5. Experiment 5

To verify the feasibility of the proposed scheme under different degrees of collusion, this study designed six experimental scenarios: scenarios with task workers not colluding with dishonest task publishers, task workers colluding with a dishonest task publisher, task workers colluding with two dishonest task publishers, task workers colluding with three dishonest task publishers, task workers colluding with four dishonest task publishers, and task workers colluding with five dishonest task publishers. As shown in Figure 11, the more publishers collude with unreliable tasks, the lower the reputation reliability of collusive task workers. For example, the reputation reliability of normal low-quality tasks is 0.8, but the reputation reliability of collusive task workers colluding with five dishonest task publishers is only 0.39. This is because the reputation reliability of task workers is the average aggregation of the reliability of task publishers, so the more malicious task publishers collude with task workers, the lower the reputation reliability.

Figure 11.

Reputation reliability of task workers in collusion with different numbers of dishonest task publishers.

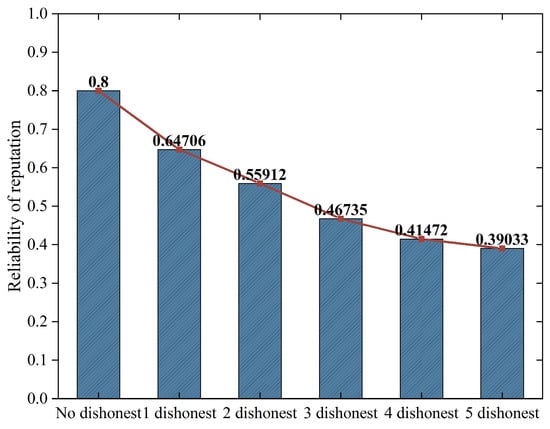

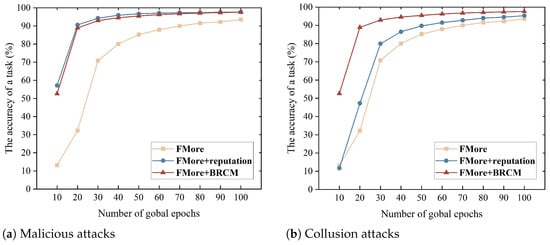

6.3.6. Experiment 6

To validate the feasibility of applying BRCM to FMore, we simulate a FL environment with 20 task workers. Among them, five are malicious/collusive task workers, all of whom are low-quality task workers. Additionally, there are 5 normal low-quality task workers and 10 high-quality task workers. The local data volume of low-quality task workers ranges from [915, 960], while high-quality task workers have a local data volume of 3000. Moreover, low-quality task workers only possess three classes of local data, whereas high-quality task workers have data from all classes. The bandwidth of all task workers ranges from [5 M, 50 M], and their computational resources are determined by the number of CPU cores, with possible options being [2, 4, 8, 16]. By calculating the scoring rules, the task publisher will select the top 10 task workers to participate in the training. In the experiment, we focus particularly on two types of special task workers: malicious task workers and collusive task workers. Malicious task workers falsely inflate the data volume and data types in their bids (set to 3000 and 10, respectively) to illegally secure participation opportunities. Collusive task workers go a step further by not only falsely inflating their data volume and data types but also colluding with the task publisher to obtain high reputations, thereby influencing model training in a more covert manner.

Figure 12a shows that FMore reduces model accuracy when subjected to malicious attacks, whereas FMore combined with a reputation mechanism and FMore combined with BRCM effectively defend against such attacks. In the latter two schemes, malicious task workers receive low reputations, and the task publisher can set reputation thresholds to prevent them from participating in training tasks, thereby ensuring the protection of model accuracy. Figure 12b indicates that when facing collusion attacks, both FMore and FMore combined with a reputation mechanism perform poorly, while FMore combined with BRCM demonstrates better defensive capabilities. This is because BRCM not only considers the reputation of task workers but also incorporates an evaluation of reputation reliability, which effectively detects and suppresses collusive behavior.

Figure 12.

The accuracy of a task in different attacks.

7. Discussion

In our proposed framework, we assume the existence of a logically trustworthy task authority (TA) responsible for the unified management and updating of reputation and reliability information. The TA serves as a central coordinator that collects feedback, aggregates reputations, and maintains system-wide trust consistency. However, this assumption introduces a certain limitation, as the model’s applicability is constrained in environments where such a trusted authority does not exist or cannot be guaranteed.

To address this limitation, a potential extension of our work is to replace the centralized TA with a decentralized consensus mechanism. For example, a blockchain-based or distributed consensus approach could be employed, allowing task publishers and task workers to jointly maintain and update reputation information in a verifiable and tamper-resistant manner. Such an extension would enhance the robustness, transparency, and scalability of the reputation system, enabling its deployment in fully decentralized federated learning environments.

Moreover, in a multi-publisher federated learning setting, this decentralized design naturally supports dynamic role transitions between task publishers and task workers. Each participant can alternately act as a publisher or worker in different learning rounds while sharing reputation information through a common ledger. The blockchain consensus ensures that all updates to reputation and reliability values are synchronized and auditable, effectively eliminating the single point of trust and enhancing fairness among all participants.

8. Conclusions

In this paper, we consider a more practical assumption that both task publishers and task workers collude with each other to help collusive task workers obtain a high reputation. Based on this assumption, we propose a collusion-resistant and reliable incentive mechanism for FL. First, we devise a novel metric named reliability to measure the credibility of both task publishers and task workers. Second, we devise a new method to compute the publisher reliability. Specifically, we compute the deviation of reputation scores among different task publishers and assign a low-reliability value to a publisher once its deviation is far away from that of other publishers. Third, we propose the BRCM based on the basic uncertain information model to compute reputation and reputation reliability for task workers. Furthermore, different from existing incentive mechanisms, we identify task complexity as a primary factor when assigning incentive rewards, which ensures that only workers with a high reputation, reliable reputation, and the capability to accomplish complex tasks can win a high reward. Notably, the proposed incentive mechanisms can not only prevent collusion attacks but also motivate high-quality workers to participate. Finally, we conduct extensive experiments to verify the efficiency and efficacy of our proposed schemes. The results demonstrate that our proposed schemes are not only collusion-resistant but also achieve higher training accuracy compared with the state of the art on the MNIST dataset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.; software, validation, formal analysis, visualization, M.L.; investigation, resources, writing—review and editing, Y.W.; supervision, project administration, writing—review and editing, L.L.; formal analysis, data interpretation, W.C.; supervision, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing, H.P.; literature search, data collection, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of china under Grant 2023YFC3305002, NSFC under Grant 62376092, Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province under Grant 2024JJ5113, in part by the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province under Grant 23A0462 and 23B0592.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yan Wang is employed by KylinSoft Corporation, Changsha 410003, China. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Neto, N.N.; Madnick, S.; Paula, A.M.G.D.; Borges, N.M. Developing a global data breach database and the challenges encountered. J. Data Inf. Qual. JDIQ 2021, 13, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fan, Y.; Tse, M.; Lin, K.-Y. A review of applications in federated learning. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.U.; Saad, W.; Han, Z.; Hossain, E.; Hong, C.S. Federated learning for internet of things: Recent advances, taxonomy, and open challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1759–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Wang, D.; Shen, L.; Luo, Y.; Hu, H.; Du, B.; Wen, Y.; Tao, D. Federated Learning with Only Positive Labels by Exploring Label Correlations. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 7651–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Ding, H.; Zhao, S.; Ren, S.; Wang, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhou, S. Practical and robust federated learning with highly scalable regression training. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 35, 13801–13815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Niyato, D.; Xie, S.; Zhang, J. Incentive mechanism for reliable federated learning: A joint optimization approach to combining reputation and contract theory. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 10700–10714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, Q.; Yu, P.; Ni, W.; Liu, R.P. Ironforge: An open, secure, fair, decentralized federated learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 36, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Yu, H.; Leung, C. Towards fairness-aware federated learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 35, 11922–11938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Yu, H.; Ma, X.; Chen, C.; Sun, L.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Q.; Yu, P.S. Privacy and robustness in federated learning: Attacks and defenses. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 8726–8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebreel, N.M.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Blanco-Justicia, A.; Sánchez, D. Enhanced security and privacy via fragmented federated learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 6703–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yuan, X.; Zheng, J.; Ni, W.; Dressler, F.; Jamalipour, A. Leverage Variational Graph Representation for Model Poisoning on Federated Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Niyato, D.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guizani, M. Reliable federated learning for mobile networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2020, 27, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lyu, L. A reputation mechanism is all you need: Collaborative fairness and adversarial robustness in federated learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.10464. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Sun, H.; Yang, H.H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Quek, T.Q.S. Reputation-based federated learning for secure wireless networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 1212–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kantarci, B. Reputation-enabled federated learning model aggregation in mobile platforms. In Proceedings of the ICC 2021 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–23 June 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- ur Rehman, M.H.; Salah, K.; Damiani, E.; Svetinovic, D. Towards blockchain-based reputation-aware federated learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2020 IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–9 July 2020; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, W.; Xu, C.; Xu, M. Fifl: A fair incentive mechanism for federated learning. In Proceedings of the 50th International Conference on Parallel Processing, Lemont, IL, USA, 9–12 August 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Qin, Z.; Li, D.; Li, K.; Xu, G. A holistic client selection scheme in federated mobile crowdsensing based on reverse auction. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), Hangzhou, China, 4–6 May 2022; pp. 1305–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Lin, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wu, J.; Zhou, S. Privacy preserving ranked multi-keyword search for multiple data owners in cloud computing. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2015, 65, 1566–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Li, H.; Liu, S.; Yang, K.; Lin, X. Verifynet: Secure and verifiable federated learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 15, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, N.; Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J. VFL: A verifiable federated learning with privacy-preserving for big data in industrial IoT. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 18, 3316–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, J.; Hou, B.; Dong, C.; Baker, T. VeriFL: Communication-efficient and fast verifiable aggregation for federated learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 16, 1736–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalapaaking, A.P.; Khalil, I.; Yi, X.; Lam, K.-Y.; Huang, G.-B.; Wang, N. Auditable and Verifiable Federated Learning Based on Blockchain-Enabled Decentralization. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Niyato, D.; Ye, D.; Kim, D.I.; Zhao, J. Toward Secure Blockchain-Enabled Internet of Vehicles: Optimizing Consensus Management Using Reputation and Contract Theory. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 2906–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Mesiar, R.; Borkotokey, S.; Kalina, M. Certainty aggregation and the certainty fuzzy measures. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2018, 33, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.-S.; Pedrycz, W.; Gómez, M.; Bustince, H. Using I-subgroup-based weighted generalized interval t-norms for aggregating basic uncertain information. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2024, 476, 108771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.K.; Tran-Truong, P.T.; Trang, N.T.H. An Enhanced Incentive Mechanism for Crowdsourced Federated Learning Based on Contract Theory and Shapley Value. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Future Data and Security Engineering, Da Nang, Vietnam, 22–24 November 2023; pp. 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, H.; Wen, W.; Xia, W.; Wang, B.; Zhu, H. Contract Theory Based Incentive Mechanism for Clustered Vehicular Federated Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 8134–8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Man, D.; Yang, W. An Incentive Mechanism Design for Federated Learning with Multiple Task Publishers by Contract Theory Approach. Inf. Sci. 2024, 644, 120330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Long, S.; Guo, S. Federated learning privacy incentives: Reverse auctions and negotiations. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2023, 8, 1538–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.T.; Tran, N.H.; Tun, Y.K.; Nguyen, M.N.H.; Pandey, S.R.; Han, Z.; Hong, C.S. An incentive mechanism for federated learning in wireless cellular networks: An auction approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 4874–4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Pei, Y.; Liang, Y.-C.; Niyato, D. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning based incentive mechanism for multi-task federated edge learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 13530–13535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, P. Incentive mechanism design for Federated Learning with Stackelberg game perspective in the industrial scenario. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 184, 109592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, T.; Li, J.; Zhou, H. Multi-factor incentive mechanism for federated learning in IoT: A stackelberg game approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 21595–21606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Pan, R. Incentive mechanism for horizontal federated learning based on reputation and reverse auction. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 947–956. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, A.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, S.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, S. A truthful and reliable incentive mechanism for federated learning based on reputation mechanism and reverse auction. Electronics 2023, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ni, L.; Qi, L. Reliable federated learning based on dual-reputation reverse auction mechanism in Internet of Things. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 156, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.; Chiang, C.-K.; Sanjabi, M.; Talwalkar, A.S. Federated multi-task learning. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing System, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Shen, F.; Yan, F.; Lin, J.; Qiu, Y. Reputation-based regional federated learning for knowledge trading in blockchain-enhanced IoV. In Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Nanjing, China, 29 March–1 April 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ziller, A.; Trask, A.; Lopardo, A.; Szymkow, B.; Wagner, B.; Bluemke, E.; Nounahon, J.-M.; Passerat-Palmbach, J.; Prakash, K.; Rose, N.; et al. Pysyft: A library for easy federated learning. In Federated Learning Systems: Towards Next-Generation AI; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 111–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mothukuri, V.; Parizi, R.M.; Pouriyeh, S.; Huang, Y.; Dehghantanha, A.; Srivastava, G. A survey on security and privacy of federated learning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 115, 619–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Kamani, M.M.; Mahdavi, M. Adaptive personalized federated learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.13461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, H.B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Agüera y Arcas, B. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Hard, A.; Rao, K.; Mathews, R.; Ramaswamy, S.; Beaufays, F.; Augenstein, S.; Eichner, H.; Kiddon, C.; Ramage, D. Federated learning for mobile keyboard prediction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.03604. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Chu, X. Fmore: An incentive scheme of multi-dimensional auction for federated learning in MEC. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 40th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Singapore, 29 November–1 December 2020; pp. 278–288. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).