Abstract

Crowdsourced delivery plays a key role in fresh food retailing, where tight time limits and perishability require fast, reliable fulfillment. However, real-time order–courier assignment is challenging because orders arrive in bursts, couriers’ locations and availability change, capacities are limited, and many decisions must be made simultaneously. We propose Attn-QMIX, a novel attention-augmented multi-agent reinforcement learning framework that models each order as an agent and learns coordinated matching strategies through centralized training with decentralized execution. The framework develops a new capacity-aware multi-head attention mechanism that captures complex order–courier interactions and dynamically prevents courier overload and integrates it with a QMIX-based mixing network equipped with hypernetworks to enable effective credit assignment and global coordination. Extensive experiments on a real-world road network show that Attn-QMIX outperforms five representative methods. Compared with a novel cooperative ant colony optimization method, it reduces total cost by up to 2.30% while being up to 3403 times faster in computation.

1. Introduction

In on-demand fresh food retailing, delivering orders quickly and reliably is essential for improving customer satisfaction. Crowdsourced couriers provide a flexible workforce and elastic capacity that platforms can activate on short notice, enabling the timely fulfillment of perishable orders while improving both operational efficiency and service quality.

However, effectively assigning orders to available couriers is challenging. Fresh goods are time-sensitive, and customers expect rapid fulfillment, so the platform must respond quickly and match incoming orders efficiently to nearby, available couriers. Meanwhile, the platform may receive a large number of orders within short intervals, especially during peak periods, which expands the problem scale and further increases the difficulty of assignment. In addition, the availability and locations of crowdsourced couriers are dynamic, and order volumes and destinations fluctuate, which also complicates assignment. Timely and efficient order–courier matching under these conditions remains an open practical challenge.

The assignment of delivery orders in crowdsourced fresh grocery distribution can be regarded as an order dispatching or assignment task. Approaches for solving these problems can be divided into exact algorithms [1,2], heuristic algorithms [3,4,5,6], and deep learning-based methods [7,8,9,10]. Exact algorithms aim to find optimal solutions, although their practical applicability is often limited by computational complexity. Zhang et al. [11] proposed two exact algorithms based on integer programming and linear equation systems to solve the order matching problem in crowdsourcing last-mile delivery for up to 100 orders. Du et al. [12] introduced an exact algorithm based on bipartite graphs to solve the ride-hailing order dispatch problem for up to 375 orders. However, in real-world on-demand fresh food retailing, instances are larger, arrivals are bursty, and decisions must be produced within seconds, limiting the feasibility of exact methods.

To overcome these limitations, a variety of heuristic algorithms have been proposed. Gao et al. [13] proposed a heuristic depth-first search algorithm to address the user-knowledge task assignment problem for up to 250 tasks. Tao and Song [14] proposed a cooperative ant colony algorithm with swarm intelligence to address task allocation in mobile crowdsensing, scaling to 437 tasks. Shi et al. [15] proposed a memory-based ant colony optimization algorithm for dynamic order dispatch, handling up to 500 customer requests. Xie et al. [16] introduced a conflict-aware greedy algorithm to solve the satisfaction-aware task assignment problem in spatial crowdsourcing for up to 1200 tasks. Wu et al. [17] proposed a lightGBM-augmented heuristic that assigns spatial crowdsourcing tasks to appropriate workers, considering up to 1000 tasks. While these heuristics can handle larger instances with fast runtimes, they usually rely on hand-crafted rules and require re-tuning across scenarios. Moreover, complex dependencies among order–courier pairs are difficult for heuristics to capture, which can lead to suboptimal decisions.

In recent years, deep learning-based approaches have been widely applied to various combinatorial optimization problems [18,19,20], and order dispatching in crowdsourced delivery systems has attracted particular attention. Kavuk et al. [21] employed Deep Q-Networks [22] for order dispatching in ultra-fast delivery services, enabling optimal acceptance or cancelation decisions based on real-time courier availability and order characteristics to maximize successful deliveries within short time frames. Quan and Wang [23] proposed a deep reinforcement learning (DRL) framework for task assignment in dynamic environments. The framework leverages a convolutional spatiotemporal model to capture complex spatiotemporal correlations and incorporates a cluster-based voting method to estimate the distributions of both workers and tasks. Zhao et al. [24] proposed an adaptive task allocation method for spatio-temporal crowdsourcing based on proximal policy optimization [25] to optimize allocation utility and success rates. Wang et al. [26] proposed a DRL-based order recommendation framework for rider-centered food delivery systems, which consists of an actor–critic network, a rider behavior prediction network, and a feedback correlation network. Xu and Song [27] proposed a graph attention network–based DRL method for task allocation in mobile crowdsensing, which embeds worker–task graphs into vector representations to enhance generalization across instances and maximize platform profit under spatial and temporal constraints. Chen et al. [28] proposed a DRL-based optimization algorithm for order dispatching in on-demand food delivery services, which leverages a graph neural network [29] to model complex rider–order relationships and employs a greedy regret-based heuristic to ensure solution quality. However, these studies employ single-agent reinforcement learning, whereas in crowdsourced fresh grocery dispatch, orders simultaneously compete and cooperate over a shared pool of couriers. As a result, single-agent approaches may struggle to capture inter-order dependencies and coordinate simultaneous decisions.

To address the above challenges, we propose Attn-QMIX, an attention-augmented multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) framework for fresh grocery crowdsourced order-courier assignment. Our approach introduces two major innovations to achieve real-time decision-making and high-quality solutions. First, we develop a capacity-aware multi-head attention mechanism that effectively captures complex order-courier interactions and dynamically penalizes courier overload, enabling the model to learn utilization-aware matching patterns. Second, we integrate this module into a MARL framework based on QMIX [30], which employs centralized training with decentralized execution and uses hypernetworks for adaptive credit assignment and global coordination.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- We propose Attn-QMIX, a novel QMIX-based deep reinforcement learning model that effectively solves crowdsourced order–courier matching in large-scale real-world scenarios.

- We first propose a capacity-aware attention mechanism that jointly encodes order and courier features, captures their interactions, and produces utilization-aware compatibilities that improve global coordination and mitigate courier overloading within the QMIX framework.

- Extensive computational experiments demonstrate that our approach consistently outperforms four representative heuristics and a recent DRL model in assignment quality and computation time.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the problem description, the corresponding mathematical model, and the Markov decision process (MDP) formulation. Section 3 introduces Attn-QMIX in detail. Section 4 describes the experimental settings. Section 5 reports the experimental results. Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future directions.

2. Problem Formulation

This section presents the formal formulation of the crowdsourced order assignment problem. The problem setting and assumptions are described first, followed by its mathematical modeling.

2.1. Problem Description

In an urban environment, multiple retail stores are distributed throughout the area, offering a variety of fresh food and daily products. Customers place orders through an online platform, specifying the required items and delivery addresses. Each order is associated with a pickup store, specifies the product demand, and has a promised latest delivery time.

A fleet of crowdsourced couriers is available to deliver these orders. These couriers are independent workers who can flexibly go online or offline at any time. At the beginning of each assignment period, the platform matches available couriers with all customer orders released during that period. Each courier has the same carrying capacity and may be assigned multiple orders simultaneously, provided that the total demand does not exceed their capacity. The objective is to assign orders to available couriers over a given period to optimize the overall delivery performance of the platform, accounting for penalties for late deliveries.

To facilitate the formulation of the mathematical model, the following assumptions are made:

- All orders are released to the platform at the beginning of each assignment period.

- The locations, associated pickup stores, and demands of all orders, as well as the real-time locations and availability of all online couriers, are known at the beginning of each assignment period.

- All couriers are homogeneous, with the same carrying capacity and a constant travel speed v.

- Couriers are allowed to wait anywhere in the city and are not required to return to their initial positions after completing their deliveries.

- The waiting time at pickup and delivery locations is assumed to be negligible.

- Each order is served by exactly one courier and cannot be reassigned or split within an assignment period.

- The number of crowdsourced couriers on the platform is sufficient to meet delivery demand at all times.

- Product spoilage during transportation is negligible due to cold-chain packaging and short travel times.

2.2. Mathematical Model

Let denotes an undirected graph, where is the set of all locations in the system, including retail stores (pickup nodes), delivery locations of orders (delivery nodes), the initial positions of available couriers at the beginning of the assignment period, and the virtual end nodes for each courier. The virtual end node is introduced to represent the termination of each courier’s route and to ensure flow balance in the mathematical model. The set represents all edges between pairs of nodes, where each edge is associated with a length and a travel time , calculated as . In this study, v is assumed to be 15 km/h, a reasonable approximation of the average speed of electric mopeds in urban areas.

Let denote the set of retail stores, with coordinates for each . The set of orders is denoted by . Each order is characterized by its delivery location with coordinates , an associated pickup store with coordinates , a delivery demand , and a delivery time requirement . Each order must be delivered within time units after being accepted by a courier; otherwise, a penalty at a rate of per unit of lateness is incurred. For notational simplicity, we let o also denote the delivery node corresponding to order o. Let denote the set of available couriers. All couriers are homogeneous, each with capacity Q. For each courier , let denote its initial location, and denote a virtual terminal node used to represent the end of courier k’s service route. Since is a virtual node introduced for modeling purposes, the travel time and cost to are not included in the actual route calculations. Each courier can serve multiple orders as long as the total delivery demand does not exceed Q.

The actual arrival time of courier k at node is denoted as . If courier k does not visit node i, is an auxiliary variable without practical meaning and can take any non-negative value. Let be the unit travel time cost coefficient, and be the fixed cost per courier. Define as a binary decision variable that equals 1 if courier k travels directly from node i to node j, and 0 otherwise. A binary variable takes the value 1 if courier k is assigned at least one order, and 0 otherwise. The mathematical formulation is as follows:

s.t.

The objective Equation (1) is to minimize the total cost, which includes the travel time cost, the penalty for late delivery, and the fixed cost associated with the number of couriers used. Equation (2) ensures that each courier departs from its initial location if and only if it is assigned at least one order. Equation (3) enforces flow balance at each intermediate node, ensuring route continuity. Equation (4) guarantees that each order is assigned to exactly one courier. Equation (5) restricts the total delivery demand assigned to each courier such that it does not exceed the courier’s capacity. Equation (6) enforces service precedence for each order, requiring the courier to visit the pickup store before the delivery location. Equation (7) maintains time consistency along each courier’s route, ensuring that the arrival time at each node accounts for the preceding travel time. Equation (8) defines the binary decision variables.

2.3. Reformulation as an Markov Decision Process

To solve the crowdsourced order assignment problem in fresh food retailing using reinforcement learning, we reformulate the problem as an MDP, where each order is modeled as an agent. At the beginning of each assignment period, all order agents observe the current environment and independently select couriers for themselves. The environment determines the delivery outcomes and provides feedback in the form of system rewards, enabling agents to learn collaborative strategies to minimize the overall delivery performance of the platform. Formally, the MDP is defined by the tuple , where S denotes the state space, A the joint action space, P the state transition function, and R the reward function.

State: The environment state consists of both courier states and order states. The state of courier k is defined as , where and denote the initial location coordinates of courier k. The state of order o is defined as , where and denote the pickup location coordinates of order o, and and denote the delivery location coordinates. Therefore, the overall environment observation is represented as .

Action: After all order agents make their decisions, a joint action is formed, where the action of order agent o choosing a specific courier for transportation is denoted as . Executing action a in state S means that all matched couriers move from their initial locations to the pickup retail stores and deliver the assigned orders to their destinations, which constitutes a complete episode. The overall joint action must also satisfy the courier capacity constraints and ensure that each order is assigned to exactly one courier.

Transition: After executing action a, state S transitions to , where the locations and capacities of couriers, as well as the status of each order (e.g., whether it has been picked up or delivered), are updated according to the assignment outcomes.

Reward: After each episode, the reward R is defined as the negative value of the objective function in (1).

3. The Proposed Attn-QMIX Model

This section presents the proposed Attn-QMIX model for solving the crowdsourced order assignment problem, outlining its architecture, core components, and training procedure.

3.1. Overview

The crowdsourced order assignment problem requires multiple order agents to make decentralized decisions that must be coordinated to optimize overall system performance. Each order agent independently selects a courier, yet the global outcome relies on effective cooperation among agents. The challenges are not only coordinating multi-agent actions under shared constraints but also assigning proper credit to each agent’s decision for its contribution to the overall objective. To address these issues, we adopt QMIX, a MARL algorithm with a simple yet powerful architecture. By introducing a mixing network, QMIX captures nonlinear interactions and complex cooperative patterns among agents while aggregating their contributions into a global value. This enables the system to learn coordinated matching strategies that enhance overall efficiency, making QMIX well suited for the crowdsourced order assignment problem.

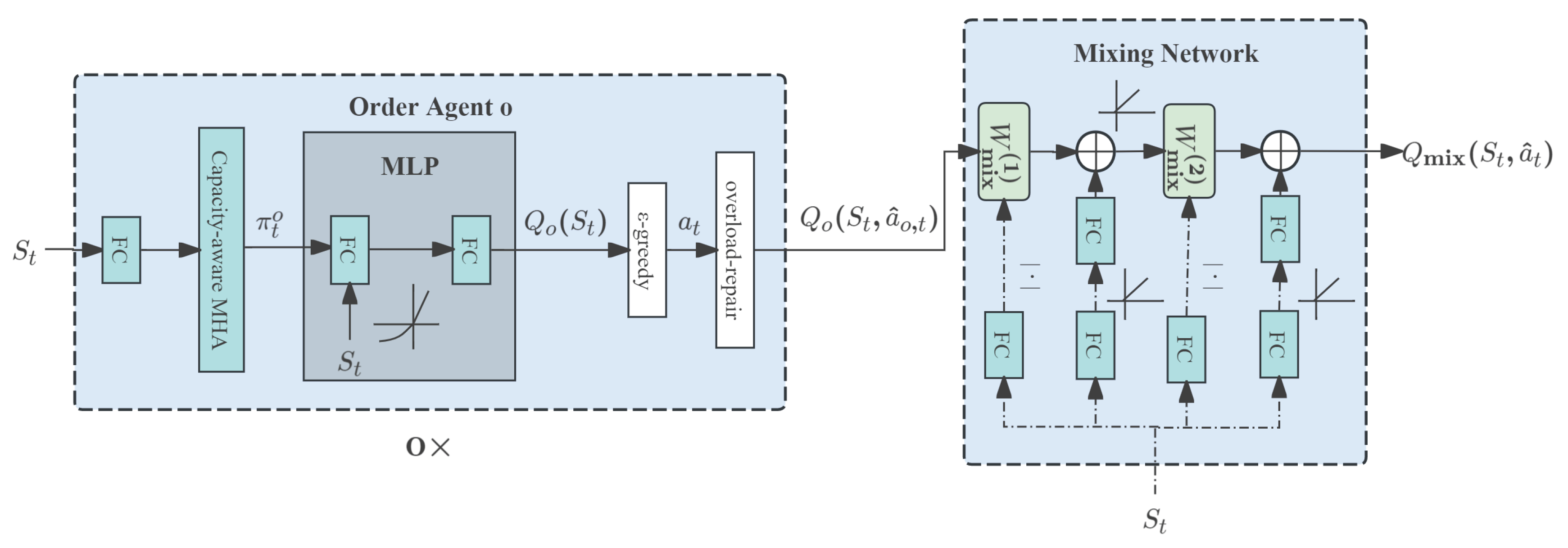

Building upon this framework, we design the Attn-QMIX model for the crowdsourced order assignment problem. As illustrated in Figure 1, the model consists of O order-agent networks with shared parameters and a mixing network with hypernetworks. The dashed components denote the hypernetworks. The order-agent network consists of a fully connected layer that embeds each order and courier state, a capacity-aware multi-head attention (MHA) layer that computes order–courier compatibility, and a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) that outputs per-order action values. At each step t, it takes the current environment state as input, consisting of per-courier states and per-order states , which is processed through a fully connected layer and a multi-head capacity-aware attention layer to produce the per-order distribution over couriers. The MLP then takes as input and outputs an action-value vector , whose k-th component equals the estimated expected return when order o takes action under state . Orders select couriers with -greedy over to form a joint action . For each order o, the action is the courier assigned to order o at time step t, which is chosen greedily with probability and uniformly at random with probability . When multiple orders choose the same courier, the combined load on a courier k may exceed its capacity. To repair overloads, we apply an overload-repair reassignment procedure. Specifically, for any overloaded k, we rank its assigned orders by their Q-values and retain the highest-Q subset within k’s capacity; the remaining orders enter a pending pool. We then process the pending pool sequentially and, for each order o, choose a courier with remaining capacity that maximizes . This yields the repaired joint action . For each used courier, we construct a feasible route by greedy insertion under pickup-before-delivery precedence, then refine it with local search (relocate, 2-opt, cross-exchange) to reduce travel time and induced tardiness. From the resulting routes, we compute travel times and order-level lateness and aggregate them into the episode reward corresponding to the repaired joint action .

Figure 1.

Architectures of Attn-QMIX.

Next, we feed the per-order chosen action values together with the state feature vector into the mixing network (as shown in Figure 1) to aggregate them via a monotonic mixing function into the joint expected return . The mixing function’s weights W and bias b are generated by hypernetworks conditioned on . To enforce monotonicity, the weights are constrained to be nonnegative by applying an absolute value operation to a linear projection; the bias is produced by a two-layer MLP with ReLU activations.

3.2. Order-Agent Network

In each decision period, all order agents act once to select couriers, after which the environment executes delivery and returns a terminal reward. Following this single-step setting, the order-agent network is designed to map the current environment state to per-order action values over couriers. At step t, the order-agent network takes as input the environment state , consisting of per-courier states for each courier and per-order states for each order (detailed in Section 3.1). Each and is passed through a fully connected layer to obtain embeddings and . These embeddings are then fed into a capacity-aware attention module that produces the per-order distribution over couriers. Specifically, an MHA layer [31] computes an initial matching score matrix , where each entry represents the initial compatibility between order o and courier k at step t based on their embeddings. Using H attention heads, the initial compatibility is calculated as

where and are learnable projection matrices for head h, d is the projection dimension, and H is the number of heads. For each order o, a softmax over couriers yields a probability distribution over couriers

Here, denotes applying the softmax function over . Since each courier may be chosen by multiple orders, their cumulative demand can exceed the capacity Q. To let the model identify couriers more likely to be over-assigned, we aggregate the expected cumulative demand of courier k and normalize by capacity to obtain the utilization

We then modify the compatibility scores to reduce the scores of couriers that are likely to be over-assigned

where is a soft utilization threshold indicating near saturation of courier capacity, is a temperature that controls the smoothness of the penalty, and controls the penalty strength. The softplus function is . The final per-order distribution over couriers is

Then, a two-layer MLP with ELU activation [32] takes as input to compute the action value vector, where . The forward propagation is given in Equations (14) and (15),

where and denote the learnable projection matrices of the hidden and output layers, respectively, and and are the corresponding learnable bias vectors. The ELU nonlinearity used in Equation (16) is

Based on the resulting action value vector over , orders select couriers via an -greedy strategy to form the joint action . To avoid potential capacity violations, we then repair infeasible assignments through an overload-repair procedure (detailed in Section 3.1), and finally obtain the repaired joint action and corresponding per-order chosen action values .

3.3. Mixing Network and Hypernetworks

Given the per-order chosen action values for all orders, QMIX aggregates them into a joint expected return via a state-conditioned monotonic mixing network whose parameters are produced by hypernetworks. Specifically, we adopt a two-layer mixer,

where . The weights and the biases are generated by hypernetworks conditioned on the environment state .

To make sure that, for each order, the action that maximizes its own Q-value also maximizes , we constrain the mixing network to be monotonic in every per-order value ,

Under Equation (19), maximizing the joint value decomposes across agents,

We enforce monotonicity by constraining mixer weights (i.e., ) to be nonnegative via an absolute-value transform of the output of a feedforward layer. Biases (i.e., ) are produced through a two-layer MLP with ReLU activations.

3.4. Model Training

To improve robustness and prevent gradient explosion, we train our QMIX model with the Huber loss [33], parameterized by . For a minibatch of size B, the objective is

where is the global reward after executing the joint action (i.e., the negative of the total objective). The Huber loss is defined as

We optimize Equation (21) using RMSProp with global-norm gradient clipping. To ensure training stability, we adopt an experience replay buffer that samples minibatches from the replay buffer for updates. Gradients are computed with PyTorch’s autograd, and the optimizer updates the parameters . After sufficient episodes, we obtain the trained network parameters .

4. Experiment Settings

This section details the experimental setup, including instance generation, implementation configurations, and baselines.

4.1. Instance Generation

The experiments are conducted on the road network within Chengdu’s Fourth Ring Road. The underlying network data are extracted from OpenStreetMap, comprising 1746 nodes and 4274 edges, where each edge represents a road link with its length. We compute shortest-path distances between all node pairs using Dijkstra’s algorithm and convert them to travel times with a constant speed v = 15 km/h, thereby obtaining the shortest travel-time matrix for routing and cost evaluation.

The number of retail stores is set to , and pickup locations are selected by uniformly sampling 80 nodes from the network. To evaluate our approach across different problem scales, we consider four instance settings defined by the order–courier pairs . Each instance generates O orders by randomly sampling delivery nodes from the remaining network nodes and assigning each order to its nearest store. The demand for each order is randomly sampled between 1 and 9. The delivery-time requirement is sampled uniformly from minutes. The initial locations of K couriers are randomly sampled from the remaining network nodes. We set the courier capacity to in all problem instances. The unit travel-time cost , unit lateness penalty , and per-courier fixed cost are set to 1/min, 4/min, and 10/courier, respectively.

4.2. Implementation Details

The model consists of O order-agent networks with shared parameters and a mixing network with hypernetworks. For the order-agent network, the embedding dimension for order and courier features is 128. The capacity-aware multi-head attention uses 4 heads with a projection dimension of 64. The MLP in the order-agent network and the mixing network both use a hidden size of 128.

We generate 22,000 instances following Section 4.1 and split them into 20,000, 1000, and 1000 for training, validation, and testing, respectively. Training proceeds in single-step episodes, each corresponding to one assignment period, for a total of 20,000 episodes; at each episode a training instance is sampled to produce a transition that is inserted into the replay buffer. We train the model with the Huber loss using RMSProp optimizer (learning rate 0.0001) and apply global-norm gradient clipping at 10. We maintain a fixed-size replay buffer of 128 transitions. The buffer is filled with the first 128 transitions and then updated in a first-in–first-out manner. At each parameter update, the batch size is 128 from the replay buffer. Exploration uses -greedy with . We evaluate on the validation set every 100 episodes and keep the checkpoint with the best validation performance. These hyperparameters were selected via a preliminary grid search. Specifically, we systematically evaluate combinations of learning rates , embedding dimensions , numbers of attention heads , projection dimensions per head , and MLP hidden sizes to optimize the model’s performance while maintaining computational efficiency.

We implement the model in PyTorch (v2.5.1). Our experiments were performed on a Windows 11 server with an Intel i9-14900 CPU (128 GB RAM), and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB VRAM).

4.3. Baselines

We compare our proposed approach with the following five baseline methods:

- Random: Assigns each order to a random courier among those with sufficient residual capacity. It serves as a lower-bound benchmark resulting from stochastic assignment.

- Greedy: A simple and fast construction heuristic that assigns each order to the feasible courier whose current location is closest to its assigned retail store, reflecting a cost-driven local decision rule.

- CACO: A cooperative ant colony algorithm developed by Tao and Song [14] to address task allocation, employing pheromone-guided worker–task selection with cooperative swarm intelligence, which can obtain an approximation to the optimal solution within reasonable computational time.

- CA-Greedy: A conflict-aware greedy algorithm proposed by Xie et al. [16] for the SATA problem in spatial crowdsourcing, introducing a conflict-resolution mechanism and an iterative selection strategy that balances satisfaction and feasibility, and providing an optimal theoretical approximation guarantee with efficient computation.

- GDRL: A graph attention–based deep reinforcement learning method proposed by Xu and Song [27] for task allocation, which integrates a graph attention network encoder with a double DQN policy to enable fast inference and strong generalization, demonstrating superior performance and efficiency validated by extensive experiments.

5. Experiment Results

This section reports the performance of the proposed Attn-QMIX model, including comparisons with baselines, robustness under dynamic order and courier volumes, and ablation studies.

5.1. Comparison with Baselines

Table 1 reports a comprehensive comparison between the proposed Attn-QMIX and five baselines over four problem scales, , , , and , where each pair denotes the numbers of orders and couriers. For each scale, we evaluate all methods on 1000 generated instances without repetition, following Section 4. The “Cost” column records the average total cost over 1000 instances. “Gap (%)” is the relative percentage difference between the cost of a given method and the CACO cost, where negative values indicate improvement over CACO. “Time” reports the average computational time to process a batch of 100 instances.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of different methods.

From Table 1 we can find that (1) compared with CACO, Attn-QMIX consistently achieves lower costs across all four scales, with relative reductions of , , , and , while also requiring significantly less computation time. Specifically, Attn-QMIX is markedly faster, reducing runtime from hours to seconds and achieving a speedup of 2703–3403 times. (2) Compared with Greedy, Attn-QMIX requires a similar amount of computation time but achieves substantial performance gains of 5.11% to 7.19%. (3) CA-Greedy performs slightly worse than CACO in solution quality and is consistently outperformed by Attn-QMIX, with improvements of 2.65–3.11%, while also being faster. (4) GDRL outperforms CACO across all scales with improvements of 0.51–0.78%. However, it remains consistently inferior to Attn-QMIX by 1.21–1.43% and incurs higher computational costs. (5) Random is the fastest method but yields the worst solutions.

These results demonstrate that Attn-QMIX achieves a favorable balance between solution quality and efficiency. From a practical perspective, for a platform handling thousands of orders daily, the observed 1.9–2.1% improvement translates into hundreds of kilometers of reduced travel distance and several hours of courier time saved per day. Beyond direct distance and time savings, such improvements also imply higher courier utilization efficiency, faster order fulfillment for customers, and lower overall operational costs. These benefits are valuable for on-demand delivery platforms that operate under tight service-level commitments.

5.2. Robustness Under Dynamic Order and Courier Volumes

We further evaluate the robustness of Attn-QMIX under dynamically varying order and courier volumes, since in practice the numbers of orders and available couriers change over time. Table 2 reports the performance comparison of different methods under these dynamic settings. In this table, “(300, 500)” means that for each of the 1000 test instances, we first sample the number of orders O from 1 to 300 and then sample the number of couriers K from to 500, where denotes the ceiling operator. The other three entries are defined in the same way.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of different methods under dynamic order and courier volumes.

From Table 2 we observe that (1) Attn-QMIX maintains a clear advantage under dynamically varying volumes. Compared with CACO, it reduces the total cost by 1.99%, 2.04%, 2.30%, and 2.21% across the four scales, respectively. (2) Relative to Greedy, Attn-QMIX achieves cost reductions of 5.03–7.29%. (3) CA-Greedy slightly trails CACO (within 1.13%) and is substantially outperformed by Attn-QMIX, with improvements ranging from 2.90% to 3.28%. (4) GDRL performs better than CACO but worse than our proposed Attn-QMIX. Specifically, GDRL reduces cost over CACO by 0.64–1.13%, yet it is surpassed by Attn-QMIX, which achieves 1.09–1.45% lower cost than GDRL. (5) Random remains the weakest, with costs 7.29–9.98% higher than CACO across all dynamic settings. These results indicate that our Attn-QMIX model generalizes well when O and K fluctuate.

The results under dynamic order and courier volumes reveal Attn-QMIX’s strong adaptability to fluctuating real-world conditions. In practical delivery operations, the numbers of available couriers and incoming orders vary significantly over time, for example, surging during peak hours and declining late at night. The fact that Attn-QMIX consistently maintains superior cost efficiency across these varied settings highlights its robustness and generalization capability. Such adaptability is crucial for online platforms that must operate continuously under changing supply-demand conditions.

5.3. Ablation Study

To further validate the effectiveness of the capacity-aware MHA mechanism and QMIX, we conduct ablation experiments. We consider two variants. The first is “w/o capacity-aware MHA”, which removes the attention module from the order-agent network. The second is “w/o Mixing Network”, which discards the state-conditioned mixer and hypernetworks; each order-agent network is trained independently without centralized value aggregation.

The results demonstrate that both the capacity-aware MHA and the mixing network contribute significantly to overall performance. It can be found from Table 3 that (1) adding the capacity-aware MHA yields notable improvements, as Attn-QMIX surpasses the “w/o Capacity-aware MHA” variant by 1.68–1.89%, confirming the effectiveness of the capacity-aware MHA mechanism. (2) Incorporating the mixing network brings additional gains, as Attn-QMIX surpasses the “w/o Mixing Network” variant by 2.62–2.74%, highlighting the importance of centralized credit assignment for coordinating decentralized decisions. (3) The computational overhead introduced by these components is minimal. Compared with the two variants, Attn-QMIX exhibits comparable runtime, with a maximum difference of 0.67 s, thus improving effectiveness without sacrificing efficiency.

Table 3.

Results of ablation study.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes Attn-QMIX, an attention-augmented QMIX framework for crowdsourced order assignment in fresh food retail, aiming to improve delivery efficiency and reduce costs. The model introduces a novel capacity-aware attention mechanism that captures order-courier compatibilities while preventing overload, combined with a mixing network and hypernetworks that enable effective credit assignment and coordinated multi-agent decisions, thereby enhancing both effectiveness and efficiency in cooperative order allocation to achieve real-time, high-quality decision-making.

Experiments on a real-world road network show that Attn-QMIX outperforms five effective baselines, including three representative heuristics (Random, Greedy, and CA-Greedy), a novel metaheuristic (CACO), and a recent DRL method (GDRL). Compared with CACO, Attn-QMIX reduces total cost by up to 2.30% and is up to 3403 times faster. Moreover, under dynamically varying numbers of orders and couriers, Attn-QMIX maintains a 1.99–2.30% cost reduction over CACO, demonstrating strong robustness to fluctuations in O and K. From a practical perspective, these performance improvements translate into hundreds of kilometers of reduced travel distance and several hours of courier time saved per day, delivering tangible operational and environmental benefits for large-scale delivery platforms. The ablation study confirms that both components are important; removing the capacity-aware attention increases cost by 1.68–1.89%, and removing the mixing network increases cost by 2.62–2.74%, indicating that coordination and capacity awareness jointly drive the gains.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The current experiments employ synthetic instances constructed from real road networks and assume homogeneous couriers and static travel speeds. These simplifications may constrain the model’s applicability to real-world environments characterized by time-dependent travel speeds, variable service times, and heterogeneous courier capacities. Future research could extend the framework to multi-period rolling assignments under stochastic and dynamic conditions, making it applicable to realistic dynamic and stochastic environments with continuously incoming orders. It would also be valuable to investigate integrating deep learning-augmented routing models into our Attn-QMIX framework to further improve performance. Additionally, experiments on other cities and real operational datasets can further validate the generalizability and robustness of the proposed model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and C.W.; methodology, J.H.; software, J.H.; validation, C.W.; investigation, J.H.; resources, C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, C.W.; supervision, C.W.; project administration, C.W.; funding acquisition, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71972136) and National Social Science Fund of China (No. 23FGLB044).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zheng, L.; Chen, L. Maximizing Acceptance in Rejection-Aware Spatial Crowdsourcing. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2017, 29, 1943–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vass, J.; Lackner, M.L.; Mrkvicka, C.; Musliu, N.; Winter, F. Exact and Meta-Heuristic Approaches for the Production Leveling Problem. J. Sched. 2022, 25, 339–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Ngai, E.W.; Wu, Y. Toward a Real-Time and Budget-Aware Task Package Allocation in Spatial Crowdsourcing. Decis. Support Syst. 2018, 110, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Ding, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, L. Two-Sided Online Micro-Task Assignment in Spatial Crowdsourcing. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2019, 33, 2295–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Huang, J.; Guo, L. Reliable Fog-Based Crowdsourcing: A Temporal–Spatial Task Allocation Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 7, 3968–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cheng, P.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, L. Minimizing Maximum Delay of Task Assignment in Spatial Crowdsourcing. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 35th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Macao, China, 8–11 April 2019; pp. 1454–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, C.; Mamoulis, N.; Cheng, R.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Qian, Y. An End-to-End Deep RL Framework for Task Arrangement in Crowdsourcing Platforms. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 36th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Dallas, TX, USA, 20–24 April 2020; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Sai, A.M.V.V.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Tong, X.; Cai, Z. Task Assignment for Hybrid Scenarios in Spatial Crowdsourcing: A q-Learning-Based Approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 131, 109749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Huang, X.; Xu, J.; Gao, W.; Xu, M. Efficient Adaptive Matching for Real-Time City Express Delivery. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 5767–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Pan, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Ding, X. A Matching Algorithm with Reinforcement Learning and Decoupling Strategy for Order Dispatching in On-Demand Food Delivery. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2023, 29, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, Z.; Li, F.; Xu, Z.; Chen, Z. Stable Matching for Crowdsourcing Last-Mile Delivery. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 8174–8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Li, X.; Cheng, L.; Lu, W.; Li, W. Order Matching Optimization of the Ridesplitting Service: A Scenario with Midway Stops. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 194, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Gan, Y.; Zhou, B.; Dong, M. A User-Knowledge Crowdsourcing Task Assignment Model and Heuristic Algorithm for Expert Knowledge Recommendation Systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 96, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Song, W. Profit-Oriented Task Allocation for Mobile Crowdsensing with Worker Dynamics: Cooperative Offline Solution and Predictive Online Solution. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2020, 20, 2637–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhan, Z.H.; Liang, D.; Zhang, J. Memory-Based Ant Colony System Approach for Multi-Source Data Associated Dynamic Electric Vehicle Dispatch Optimization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 17491–17505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, K. Satisfaction-Aware Task Assignment in Spatial Crowdsourcing. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 512–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Peng, L.; Xiang, C. Assuring Quality and Waiting Time in Real-Time Spatial Crowdsourcing. Decis. Support Syst. 2023, 164, 113869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, P.; Zheng, N.; Chen, B.; Principe, J.C.; Wang, F.Y. Associations between MSE and SSIM as cost functions in linear decomposition with application to bit allocation for sparse coding. Neurocomputing 2021, 422, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallestad, J.; Hasibi, R.; Hemmati, A.; Sörensen, K. A general deep reinforcement learning hyperheuristic framework for solving combinatorial optimization problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 309, 446–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Teng, L.; Wu, G. Deep reinforcement learning for solving vehicle routing problems with backhauls. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 4779–4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavuk, E.M.; Tosun, A.; Cevik, M.; Bozanta, A.; Sonuç, S.B.; Tutuncu, M.; Kosucu, B.; Basar, A. Order Dispatching for an Ultra-Fast Delivery Service via Deep Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 4274–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G. Human-Level Control through Deep Reinforcement Learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Wang, N. An Optimized Task Assignment Framework Based on Crowdsourcing Knowledge Graph and Prediction. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 260, 110096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y.; Pan, T. PPO-TA: Adaptive Task Allocation via Proximal Policy Optimization for Spatio-Temporal Crowdsourcing. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 264, 110330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Dong, C.; Ren, H.; Xing, K. An Online Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Order Recommendation Framework for Rider-Centered Food Delivery System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 5640–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Song, W. Intelligent Task Allocation for Mobile Crowdsensing with Graph Attention Network and Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Wang, L.; Liang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhao, J.; Ding, X. Order Dispatching via GNN-based Optimization Algorithm for on-Demand Food Delivery. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 13147–13162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Stark, H.; Jegelka, S.; Jaakkola, T.; Barzilay, R. Graph Neural Networks. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T.; Samvelyan, M.; De Witt, C.S.; Farquhar, G.; Foerster, J.; Whiteson, S. Monotonic Value Function Factorisation for Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 7234–7284. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing System, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Clevert, D.A.; Unterthiner, T.; Hochreiter, S. Fast and Accurate Deep Network Learning by Exponential Linear Units (Elus). In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Learning Representations, San Juan, PR, USA, 2–4 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, P.J. Robust Estimation of a Location Parameter. In Breakthroughs in Statistics; Kotz, S., Johnson, N.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 492–518. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).