Abstract

The Modular Multilevel Matrix Converter (M3C) has the potential to contribute to onshore grid frequency response by utilizing the electrostatic energy stored in its submodules. However, in the current offshore wind power domain, control schemes for M3C-based Low-Frequency AC transmission systems (M3C-LFACs) fail to effectively exploit the capacitor energy of M3C to provide adequate inertia support. Existing M3C controls are typically grid-following and thus suffer from stability issues under weak-grid conditions. To address this challenge, a dual-port grid-forming control strategy for M3C-LFAC systems is proposed, based on an energy synchronization loop. This approach enables phase-locked-loop-free synchronization between the M3C and the grid while establishing low-frequency link voltage vectors. Building on this foundation, an optimized energy utilization method for M3C total energy is introduced, featuring a two-stage preset curve to maximize the system’s inherent energy for frequency response. Under varying levels of grid load disturbances, the proposed scheme ensures that M3C-LFAC systems can provide optimal inertia support. Finally, simulation studies in MATLAB 2024b/Simulink validate the effectiveness and advantages of the proposed method.

1. Introduction

With the increasingly prominent contradiction between the demand for rapid social development and the shortage of energy resources, countries around the world have attached growing importance to the development and utilization of renewable energy. Offshore wind power, owing to its abundant wind resources and the advantage of not occupying land, has attracted wide attention [1]. However, as more and more offshore wind farms are connected to onshore grids, the overall system inertia decreases, resulting in reduced frequency stability [2,3]. Consequently, extensive research has been conducted on the inertia support of offshore wind power systems for onshore grids. The most common approach is to exploit the mechanical rotational inertia of offshore wind turbines. When the onshore grid frequency fluctuates, HVDC systems transfer additional inertial power from the turbines to suppress frequency deviations [4]. For instance, Ref. [5] proposes a coordinated frequency regulation strategy for VSC-HVDC systems based on matching control, enabling offshore wind turbines to participate in the frequency response of the onshore grid. Considering that the Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC) is increasingly competitive in high-voltage, large-capacity HVDC applications, a large body of research has focused on MMC-HVDC systems. In [6], an inertia support strategy based on the transmission of offshore AC voltage amplitude is proposed, which effectively mitigates potential stability issues caused by high rates of change of frequency (RoCoF) affecting turbine phase-locked loops (PLLs). Moreover, since the arms of sending- and receiving-end MMCs are composed of multiple submodules containing capacitors, with a wide voltage regulation range—for example, submodule capacitor voltages can reach up to 1.5 p.u. [7]—MMC-HVDC systems inherently possess strong inertia support capability. As a result, several methods have been proposed to leverage the internal energy of MMCs. For example, Ref. [8] introduces an optimized utilization method for the arm energy of sending- and receiving-end MMCs. In addition, Ref. [9] proposes an inertia compensation scheme based on embedding supercapacitors within MMC arms, which can significantly enhance the system’s inertia support capability. As discussed above, current research on offshore wind power participation in onshore grid frequency response is primarily focused on HVDC systems, while studies on low-frequency AC (LFAC) systems remain limited. Nevertheless, LFAC offers the advantages of reducing line reactance and reactive power consumption over long distances, thereby extending transmission capacity and distance [10]. Therefore, investigating inertia support methods for LFAC systems is significant. For LFAC systems, some scholars have proposed a back-to-back MMC-based scheme for frequency conversion between the grid-side fundamental frequency and the offshore low frequency [11]. However, this approach requires a large number of power electronic devices. To address this issue, the Modular Multilevel Matrix Converter (M3C) has been proposed, which can directly achieve the conversion between onshore grid-frequency voltage and offshore low-frequency link voltage without the need for an internal DC bus [12]. Reference [13] develops an electromechanical transient model of the M3C, which can accurately characterize the operating characteristics of M3C-LFAC systems. As mentioned earlier, existing studies on M3C mainly focus on converter modeling and analysis of electrical characteristics, while research on enabling M3C-LFAC systems to provide offshore wind power inertia support for onshore grid frequency response remains limited.

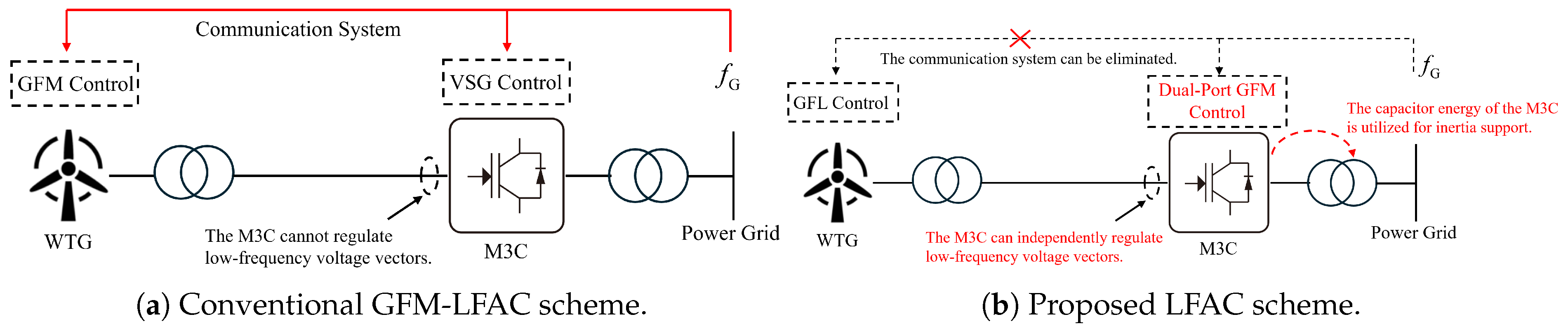

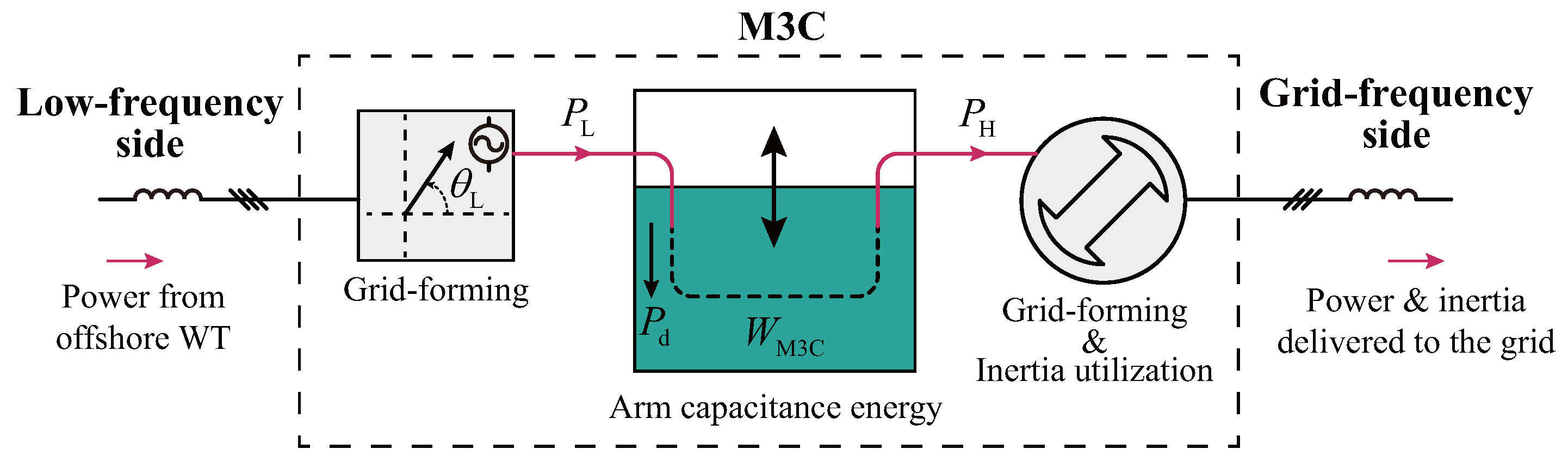

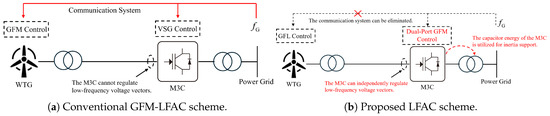

In existing studies, the grid-frequency side of M3C converters typically relies on PLL-based grid-following control [14], which makes them behave effectively as current sources with respect to the grid. However, with a high penetration of power-electronic devices, the reduced short-circuit capacity of the onshore grid can lead to stability issues under conventional grid-following control schemes [15,16]. Implementing grid-forming control on the M3C’s grid-frequency side is therefore a potential solution. As shown in Figure 1a, in conventional LFAC systems, when the M3C grid side uses VSG control, the offshore wind farm must operate in grid-forming mode to maintain the low-frequency AC link voltage—for instance, by employing grid-forming wind turbines. Meanwhile, because the M3C’s low-frequency side remains grid-following, the LFAC system cannot convey onshore grid frequency to the low-frequency link through frequency mapping. As a result, such systems typically require additional communication infrastructure to transmit grid frequency information (i.e., inertia power demand). The approach proposed in this work, illustrated in Figure 1b, enables the M3C to provide voltage-forming capability on both the grid-frequency and low-frequency sides. This eliminates the need for extra communication systems while allowing the M3C bridge-arm capacitors to directly supply additional inertia to the grid. Therefore, the critical challenge addressed here is achieving simultaneous low-frequency-side voltage formation and grid-frequency-side grid-forming operation in LFAC systems. Although recent advances in MMC research [17,18] have demonstrated that converters can operate in grid-forming modes on both the DC and AC sides, such investigations in the context of M3C are still lacking. On the other hand, similar to MMCs, the nine arms of the M3C contain a large number of capacitor submodules with wide voltage regulation capability. This provides the possibility of utilizing the arm capacitor energy of the M3C-LFAC system to deliver inertia support from offshore wind power to the onshore grid. Therefore, another pressing challenge is how to achieve independent regulation and optimized utilization of internal converter energy under dual-port grid-forming operation of M3C.

Figure 1.

Schematic comparison between the proposed and conventional GFM-LFAC schemes.

To this end, this paper proposes a dual-port grid-forming control strategy for M3C in offshore wind power LFAC systems, featuring independent regulation of the M3C arm capacitor energy. This approach enables the M3C to achieve synchronous operation with the grid without relying on a PLL. Building on this, a two-stage energy utilization strategy is introduced, which maximizes the use of the electrostatic energy stored in the M3C capacitors and further unlocks the LFAC system’s inertial support potential. The effectiveness of the proposed method is verified through electromagnetic simulations conducted in the MATLAB/Simulink environment.

2. Dual-Side Grid-Forming Control of M3C

In conventional control methods, the grid-frequency side of the M3C typically relies on a PLL to track the grid voltage vector and extract the rotating phase angle [19,20]. However, as reported in [21,22], grid-following converters based on PLL generally suffer from stability issues when connected to grids with a low short-circuit ratio (SCR). This makes it difficult for conventional methods to ensure stable operation of LFAC systems when interfaced with weak grids. To address this challenge, this paper proposes a dual-port grid-forming control strategy for M3C based on an energy synchronization loop. This chapter first outlines the M3C control framework under the dual transformation, then introduces the proposed dual-port grid-forming control method, and finally presents the equivalent relationship between M3C energy utilization and inertia support.

2.1. M3C Control Framework Based on Dual Transformation

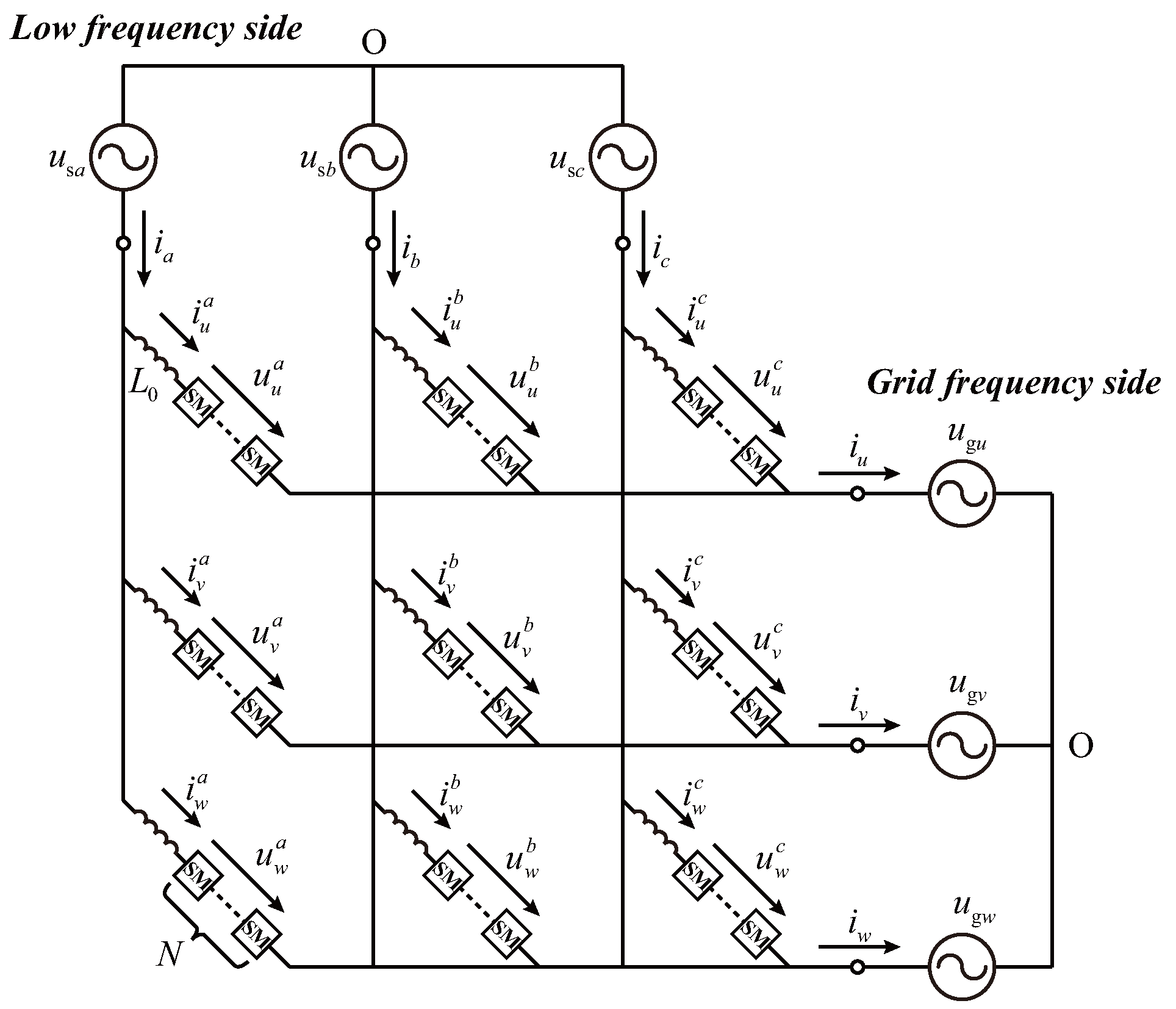

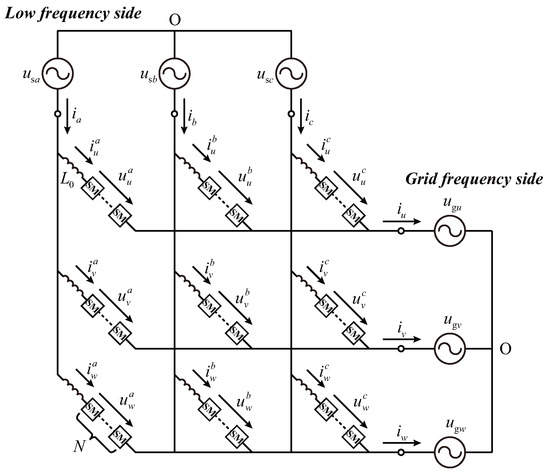

Figure 2 illustrates the M3C topology of the LFAC system, which consists of nine arms, each containing a series inductor and N full-bridge capacitor submodules. By using the voltages and currents of the nine arms, the M3C can be formulated as a state-space model:

where and , with and , represent the voltage and current of each phase arm, respectively; and denote the AC voltage on the low-frequency side and the grid voltage on the grid-frequency side, respectively. Since the arm voltage and current signals contain components from both the grid-frequency and low-frequency sides, the dual transformation is commonly employed to convert the signals from the frame to the frame [23]. Each term in Equation (1) is pre-multiplied by the transformation matrix from the abc frame to the frame, and post-multiplied by its transpose, The transformation matrix is defined as

Figure 2.

Topology of M3C in the LFAC system.

Equation (1) is transformed into the state-space representation in the reference frame:

where and represent the voltage components of the M3C on the low-frequency and grid-frequency sides in the reference frame, respectively; and denote the corresponding current components on the low-frequency and grid-frequency sides in the frame, respectively; represents the circulating component of the arm currents. When the three-phase systems on both sides are balanced, the zero-sequence components of voltage and current vanish, i.e., and . Based on this control framework, the M3C arm voltages and currents and , which contain components of different frequencies, are decoupled and transformed into the corresponding reference frame.

2.2. Dual-Port Grid-Forming Control of M3C

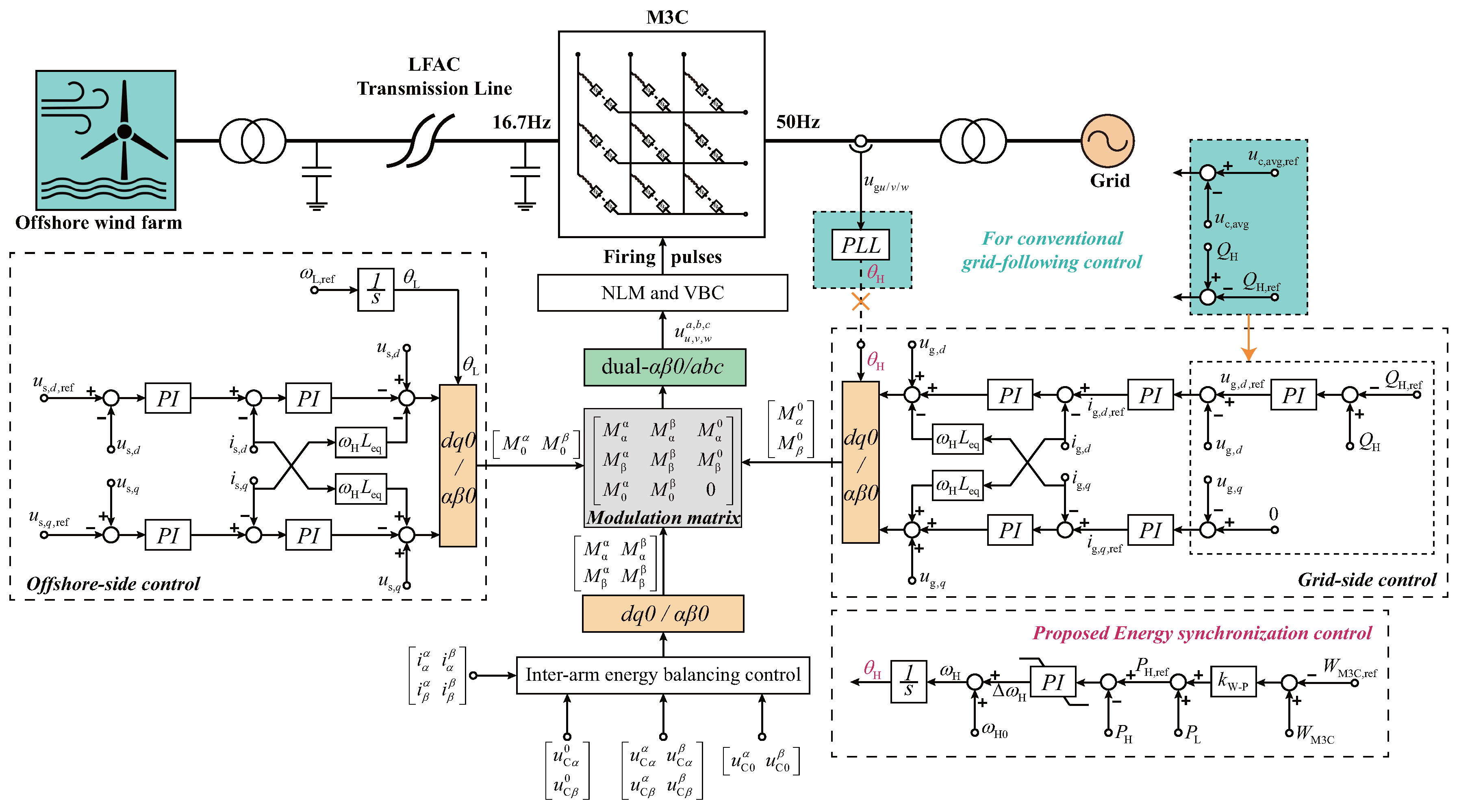

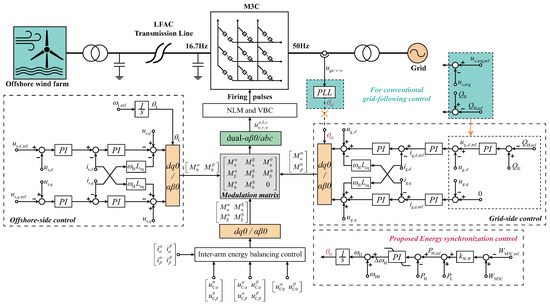

Figure 3 illustrates the LFAC system and the proposed dual-port grid-forming control method for M3C based on the energy synchronization loop. Unlike conventional grid-following control methods [24], which regulate the grid-side output voltage vector using the average voltage of submodules, the proposed method employs the total energy of M3C arm submodules, , as an explicit control variable. This enables grid-forming operation on both the low-frequency and grid-frequency sides simultaneously, eliminating the need for a PLL on the grid side, which is required in traditional approaches. In Figure 3, the blue block diagram indicates that the conventional grid-forming control components are replaced by the proposed grid-forming components, while the red text highlights the energy synchronization loop.

Figure 3.

Conventional grid-following control (in green) and proposed dual-port grid-forming control (in red) for M3C in LFAC.

Considering that the capacitor submodules in the arms possess power buffering capability, the unbalanced power between the low-frequency input power of the M3C, , and the grid-side output power, , can be expressed as

where denotes the deviation of the M3C energy from its nominal value per unit, is the nominal energy, and and represent the rated capacity of the converter and the nominal grid frequency, respectively. In the LFAC system, the low-frequency input power is determined by the operating power of the offshore wind turbines and cannot be independently regulated by the M3C. Therefore, when deviates from its reference value , the total energy can be controlled by adjusting the grid-side power either upward or downward. A droop relationship between and is established. Neglecting converter losses and assuming steady-state operation where , the reference value of the grid-side output power, , can be expressed as

where is the droop coefficient and is the power increment generated in response to the energy deviation. Equation (5) indicates that the larger the energy deviation, the greater the . In this case, the unbalanced power is nonzero, and the M3C arm energy gradually adjusts toward the reference value until the actual energy equals the specified reference . Based on the obtained , a power control loop can be designed as follows:

where and are the proportional and integral gains of the PI controller, respectively. The PI controller ensures that there is no steady-state error between and [25,26]. By adding the control term to the nominal angular frequency , the M3C grid-side output frequency and the corresponding rotating phase can be obtained. Based on the energy synchronization control process, the following relationship can be derived:

where is the phase angle between the M3C and the grid voltage vectors. It can be observed that, by utilizing the energy state of the M3C, the M3C output frequency can maintain self-synchronization with the grid frequency.

In the proposed energy synchronization loop, the grid-following control components on the grid-frequency side are replaced by grid-forming control components, as indicated by the yellow arrow on the right side of Figure 3. Based on the M3C control framework with dual transformation, the voltage and current measurements on both the low-frequency and grid-frequency sides are transformed into the corresponding dq rotating reference frames. Therefore, the commonly used dq dual-channel decoupled control framework can be applied [27].

In conventional grid-following control, the outer d-axis loop typically regulates the arm capacitor voltage by adjusting the active power output on the grid-frequency side, keeping the submodule voltage average at the specified reference , thereby ensuring active power balance between the M3C input and output. The q-axis loop usually performs reactive power control, ensuring that the grid-side reactive power tracks the reference value . However, in the proposed method, the energy synchronization loop handles the active power balance of the M3C. Consequently, the grid-frequency side has a complete voltage-current dual-loop structure, with reactive power control established outside the d-axis voltage loop, adjusting the grid-side voltage amplitude to regulate reactive power, while the q-axis voltage reference is set as .

The low-frequency side also implements grid-forming control (V/F), as shown on the left side of Figure 3. Based on the low-frequency reference , the low-frequency rotating phase can be obtained through an integrator. The low-frequency side has voltage and current loops similar to those on the grid side, with the d-axis voltage reference and the q-axis reference . Based on the modulation outputs of the voltage and current loops, and after transforming between the dq0 and frames, the fundamental frequency modulation signals on the low-frequency and grid-frequency sides, and , are obtained, respectively.

Moreover, to ensure balanced voltages among the nine arms, the arm voltage balancing control reported in [28] is adopted, where the corresponding circulating components are included in the modulation signals. Based on the outputs of the dual-side fundamental frequency control and the arm voltage balancing control, the modulation matrix M in the dual reference frames can be expressed as

Based on M, the nearest-level modulation (NLM) method and submodule voltage balancing control (VBC) reported in [29] are implemented to generate the trigger pulses for all M3C submodules. Due to space limitations, the NLM and VBC methods are not discussed in detail here.

2.3. Inertia Response Based on M3C Energy Utilization

To enable the M3C on the grid side to exhibit inertia characteristics similar to a synchronous generator, the relationship between internal energy regulation and the inertia support process must be clarified within the proposed energy synchronization control framework. The additional power provided by the M3C during the inertia response, , can be expressed as

where is the inertia constant of the M3C at rated capacity and is the deviation of the grid frequency f from the nominal frequency .

Since the buffer power provided by the M3C, , equals the negative of the unbalanced power , i.e., , we obtain

Consequently, the relationship between the desired inertia constant and the M3C energy increment corresponding to the frequency deviation can be derived as

where is the proportional coefficient relating the M3C energy increment to the grid frequency deviation when responding to . Adjusting allows flexible emulation of the M3C’s equivalent inertia.

In addition, the M3C provides an extra damping power component, which can be expressed as

where is the damping coefficient. Integrating both sides of the above equation yields the corresponding energy of the M3C arms when responding to :

Thus, the power relationship of the M3C can be expressed as

Since the proposed energy synchronization control loop employs a PI controller to explicitly regulate the total arm energy, when the control loop response time constant is sufficiently small, the actual energy can be considered to track the reference energy in real time. That is, the desired energy increment equals the reference energy increment:

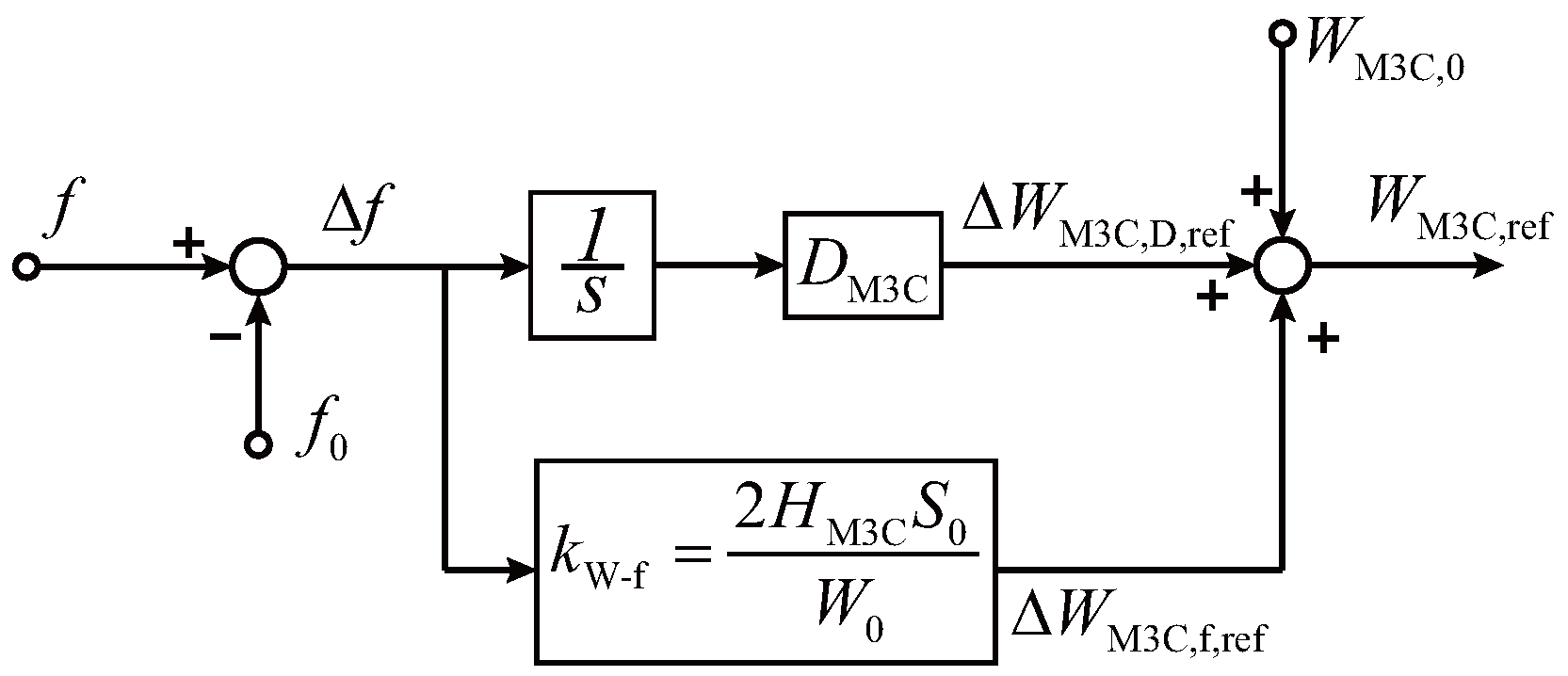

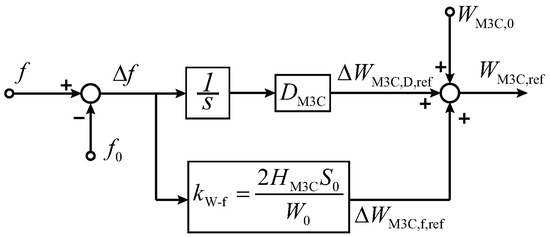

Accordingly, as illustrated in Figure 4, the reference energy of the M3C arms can be obtained as

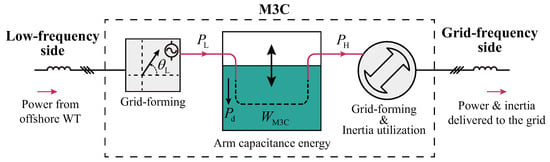

where is the initial arm energy. Figure 5 illustrates the operating characteristics of the M3C under the proposed method. The control framework ensures that the M3C can operate in grid-forming mode on both sides simultaneously. The low-frequency side constructs the offshore grid voltage vector with a constant amplitude and real-time adjustable operating frequency, while the grid-frequency side exhibits inertia characteristics similar to a synchronous generator. Through the proposed energy synchronization loop, the M3C can achieve PLL-free grid-forming synchronization with the onshore grid, and the arm capacitor energy can be transmitted to the grid in the form of additional inertia power.

Figure 4.

M3C inertia support control based on energy regulation.

Figure 5.

Schematic of M3C power and energy operation under the proposed dual-side grid-forming control.

3. Optimized Inertia Utilization Method for M3C-LFAC Systems

In Section 2, a dual-port grid-forming control method for the M3C with an energy synchronization loop is introduced. By regulating the total energy reference value of the M3C in response to grid frequency deviations, inertia support for the grid can be achieved. However, as shown in Equation (11), since is fixed, the total energy response of the M3C is only linearly dependent on the grid frequency deviation . This limitation prevents the converter energy from being fully utilized under small frequency disturbances.

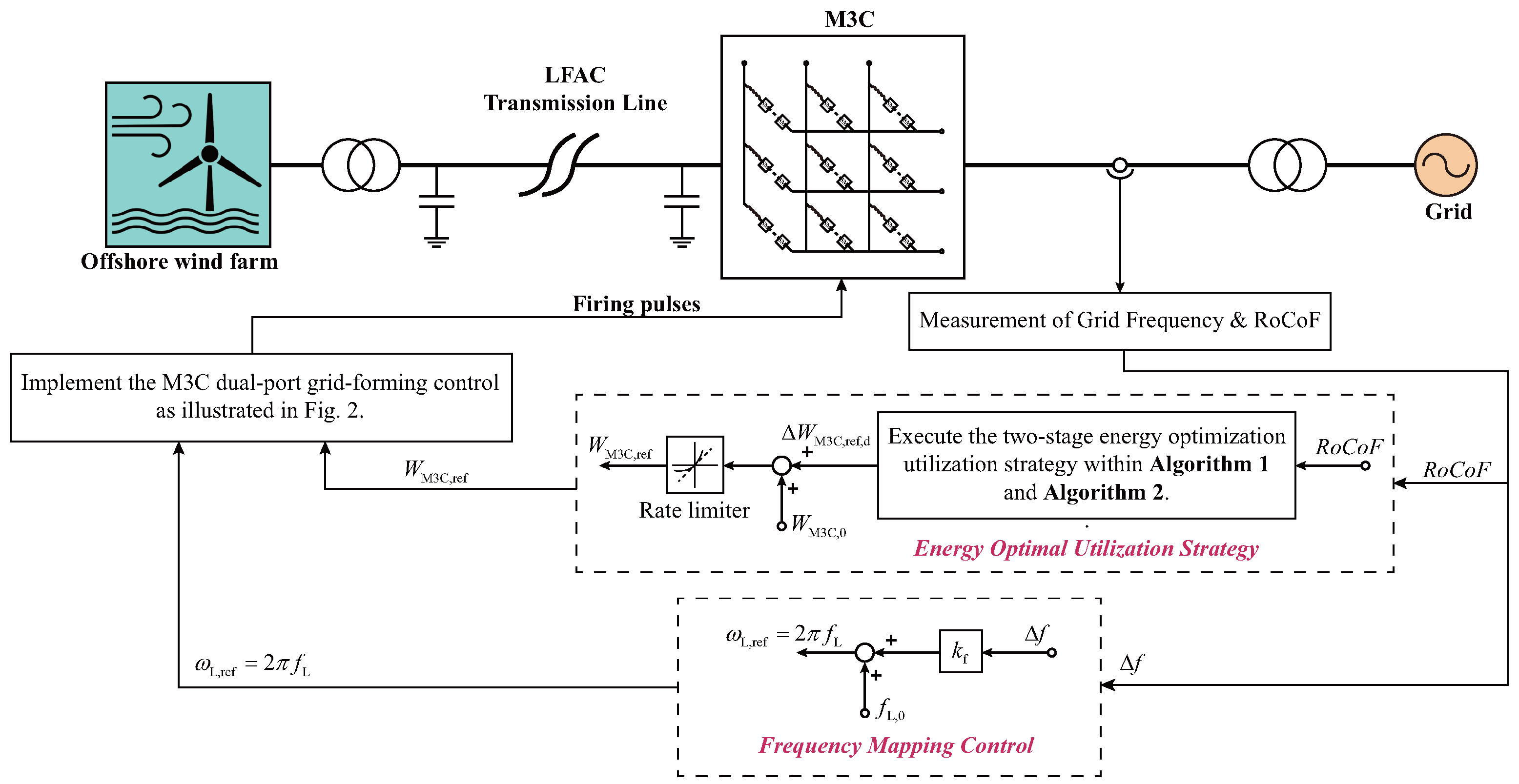

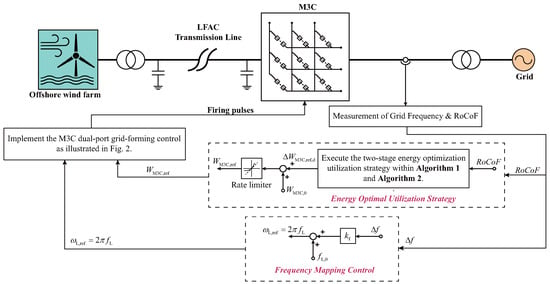

To address this issue, this paper proposes an optimized inertia utilization method for LFAC systems, as illustrated in Figure 6. The method is built upon the previously proposed M3C dual-port grid-forming control framework with an energy synchronization loop. Based on the rate of change of frequency (RoCoF), a two-stage energy optimization strategy is employed to maximize the utilization of the M3C’s internal energy for inertia response. Meanwhile, to ensure that offshore wind turbines in the wind farm can also participate in inertia response, a frequency mapping control scheme is incorporated. Finally, the resulting energy control reference value and low-frequency reference value are fed into the dual-port grid-forming control block diagram of the M3C presented in Figure 3.

Figure 6.

Inertia optimization method for LFAC based on dual-port grid-forming control of M3C.

3.1. Maximized Inertia Support Based on M3C Energy Utilization

Based on the previous analysis, it is clear that by regulating the M3C energy variation , the converter can release or absorb additional power, thereby providing an inertial power response:

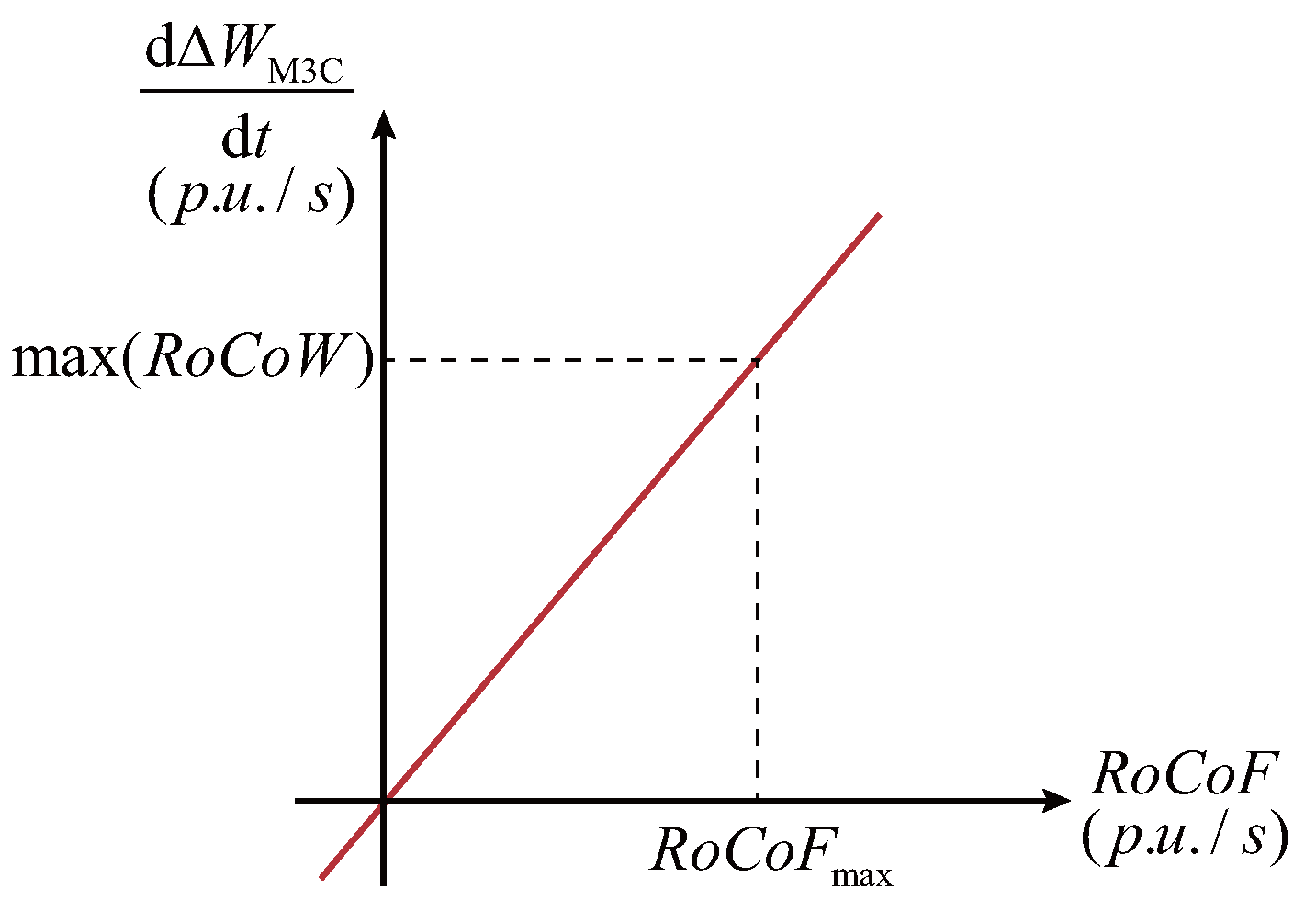

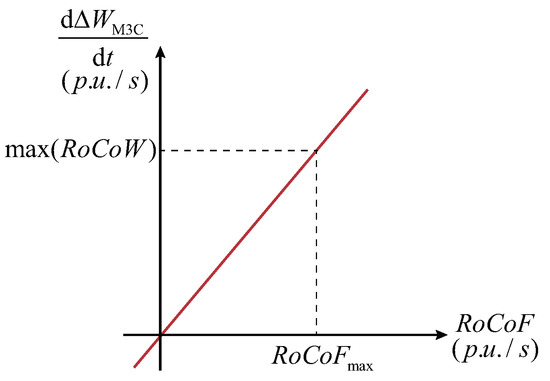

As illustrated in Figure 7, a proportional relationship can be established between the RoCoF and the required power for inertia support:

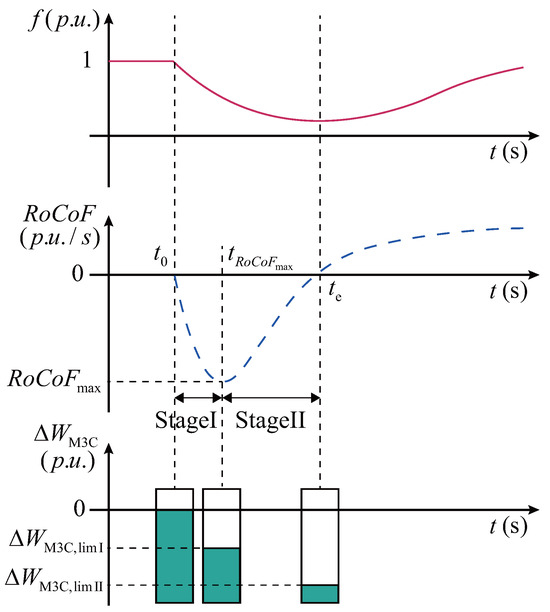

where the magnitude of is directly proportional to . Meanwhile, according to Equation (17), it can be observed that under the energy synchronization-based scheme, achieving inertia support must rely on controlling the energy variation rate . We denote this approach as control. However, as shown in Figure 8, the frequency trajectory and profile vary under different grid disturbances and synchronous generator responses. Therefore, relying solely on control does not guarantee that the M3C energy is always maximally utilized during a frequency excursion.

Figure 7.

Linear relationship between inertia response and M3C energy dynamics.

Figure 8.

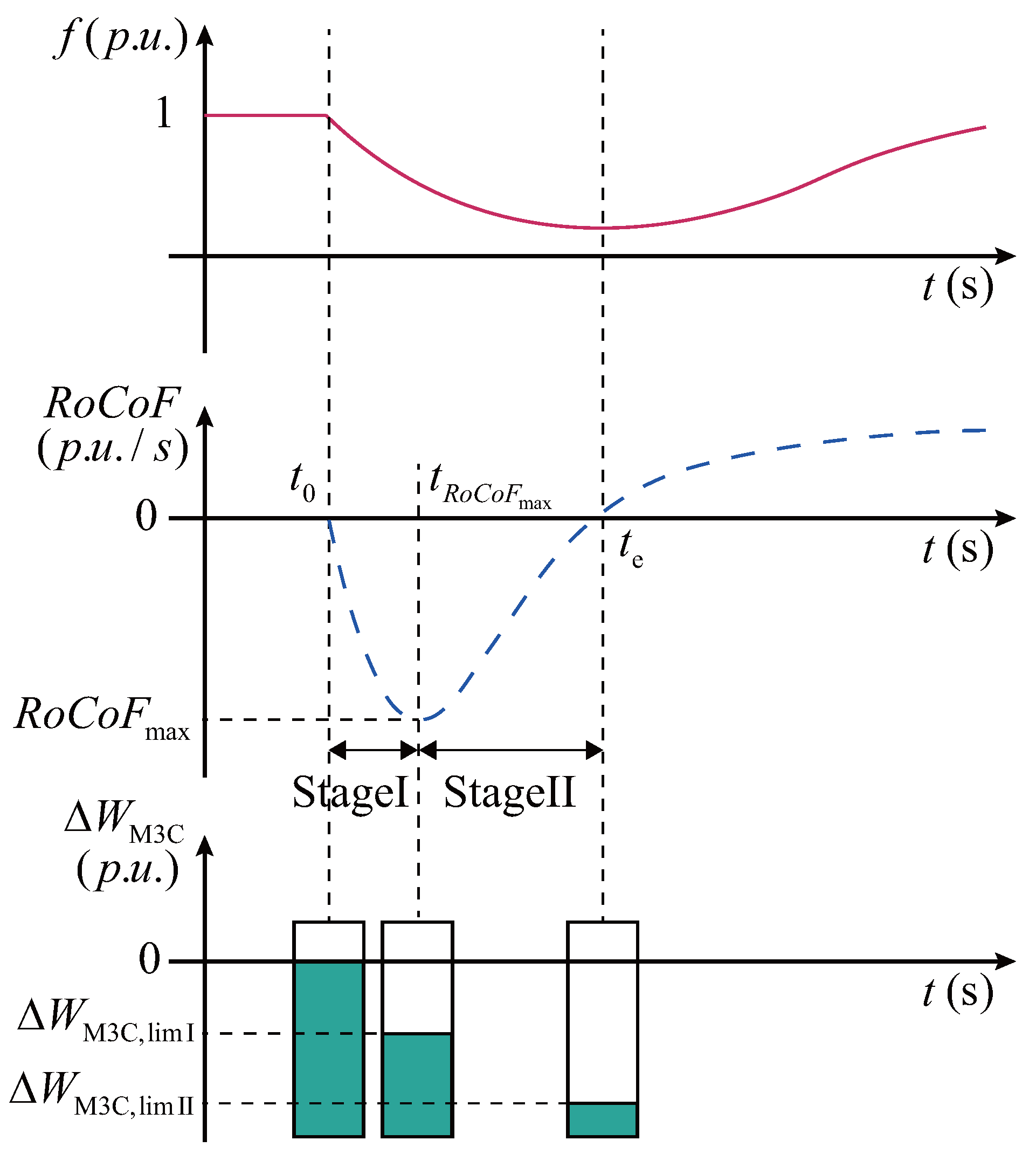

Grid frequency curve (in red) and RoCoF curve (in blue).

Considering the available M3C energy range, the optimal utilization conditions during the inertia response process can be formulated as the energy conditions and the conditions:

where denotes the instant when a grid frequency disturbance occurs, at which point the M3C energy is at its nominal value, ready to deliver inertia support. When the trajectory reaches its maximum , the M3C energy is released to the first-stage utilization limit during the interval . In the second stage , as the gradually returns toward zero, the M3C energy continues to be released until reaching the second-stage utilization limit at .

Since the curve remains positive for a short oscillatory period after , we set

where denotes the maximum exploitable M3C energy, thus ensuring that the converter provides maximized inertia support during the first frequency swing. In addition, to satisfy the proportional relationship in (18), the M3C energy variation rate must also reach its maximum when the reaches , i.e., , where denotes the maximum operator.

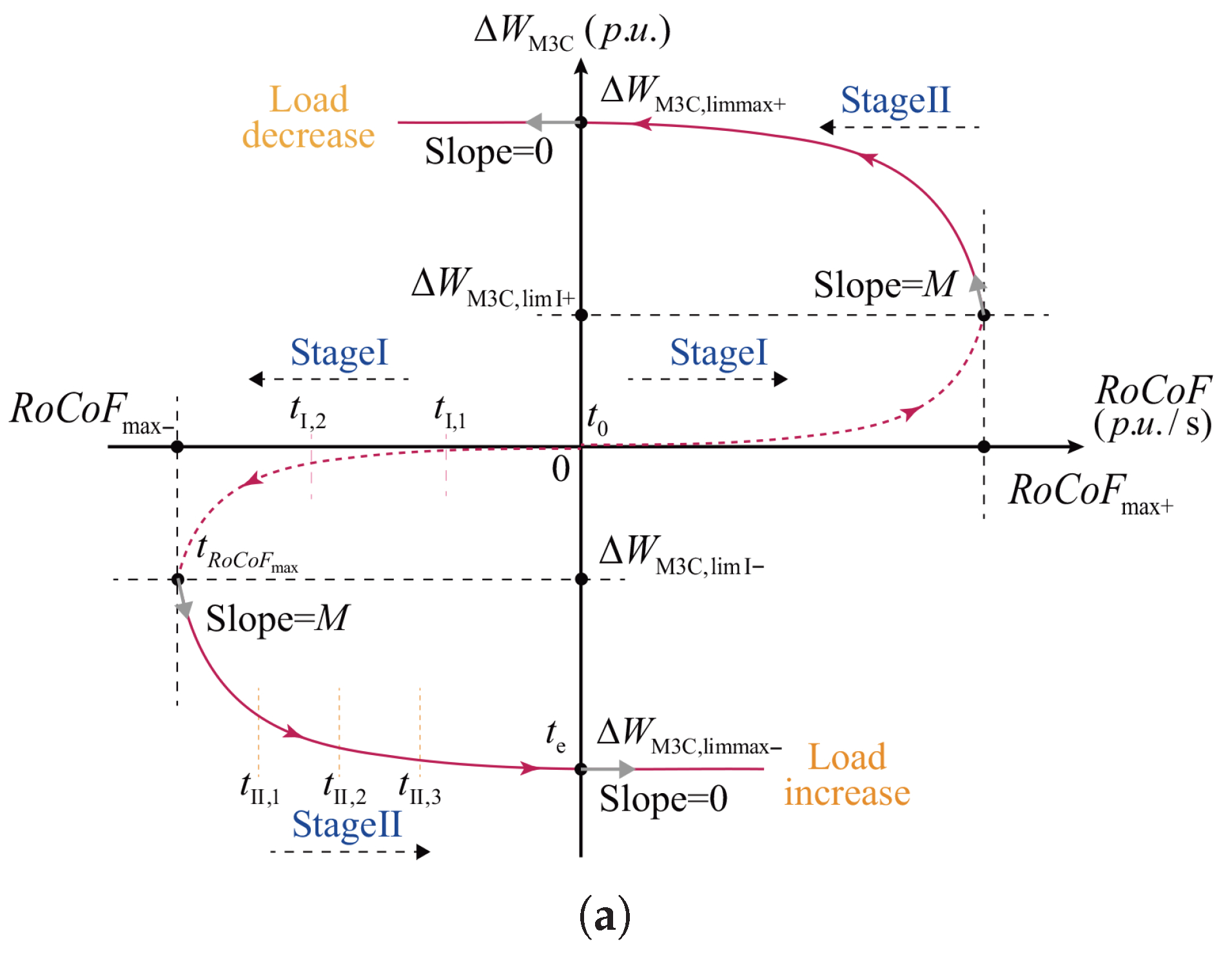

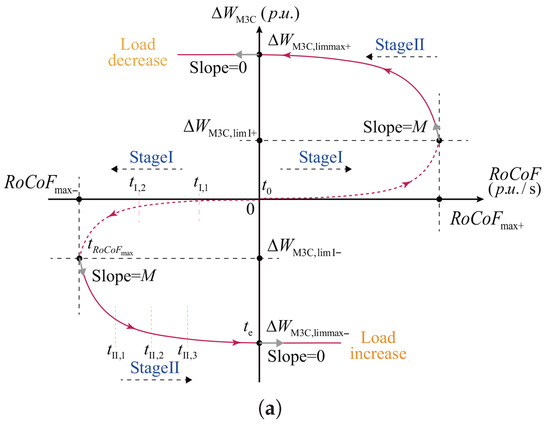

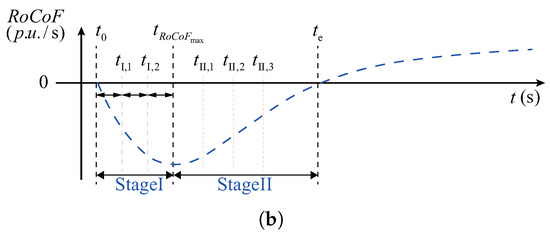

Since the curve remains monotonic in both Stage I and Stage II, an inertia support control strategy can be established based on explicit energy regulation (i.e., control), rather than the conventional energy rate control ( control). Figure 9a illustrates the designed – energy utilization curve under control, which covers both Stage I and Stage II and accounts for two possible scenarios of grid load increase and decrease. For comparison, Figure 9b presents the corresponding time scales of the curve during the first frequency swing.

Figure 9.

Proposed – curve and the corresponding time scale of the first frequency swing. (a) Proposed – curve; (b) Corresponding time scale of the first frequency swing.

- (1)

- Stage I

Considering that it is usually difficult to accurately predict under complex grid load disturbances, a droop controller is adopted in the first stage to regulate the additional inertia power according to the real-time value:

By integrating , the reference value for the M3C e ergy deviation can be obtained as

In Figure 9a, Stage I is depicted by the dashed curve. When reaches , the M3C attains the first-stage energy utilization limits, denoted as or .

- (2)

- Stage II

For Stage II, a cubic – curve is designed to achieve optimal utilization of M3C energy:

where x and y denote the axes and , respectively; represents and ; denotes and ; and M indicates the slope of the curve at , constraining the energy variation rate. The designed cubic – curve fully satisfies the and conditions given in Equations (19) and (20). Thus, by mapping the real-time measured onto the curve, the M3C energy deviation can be determined to realize inertia support for the onshore grid. During the first frequency swing, the M3C releases or absorbs its energy maximally through the two stages.

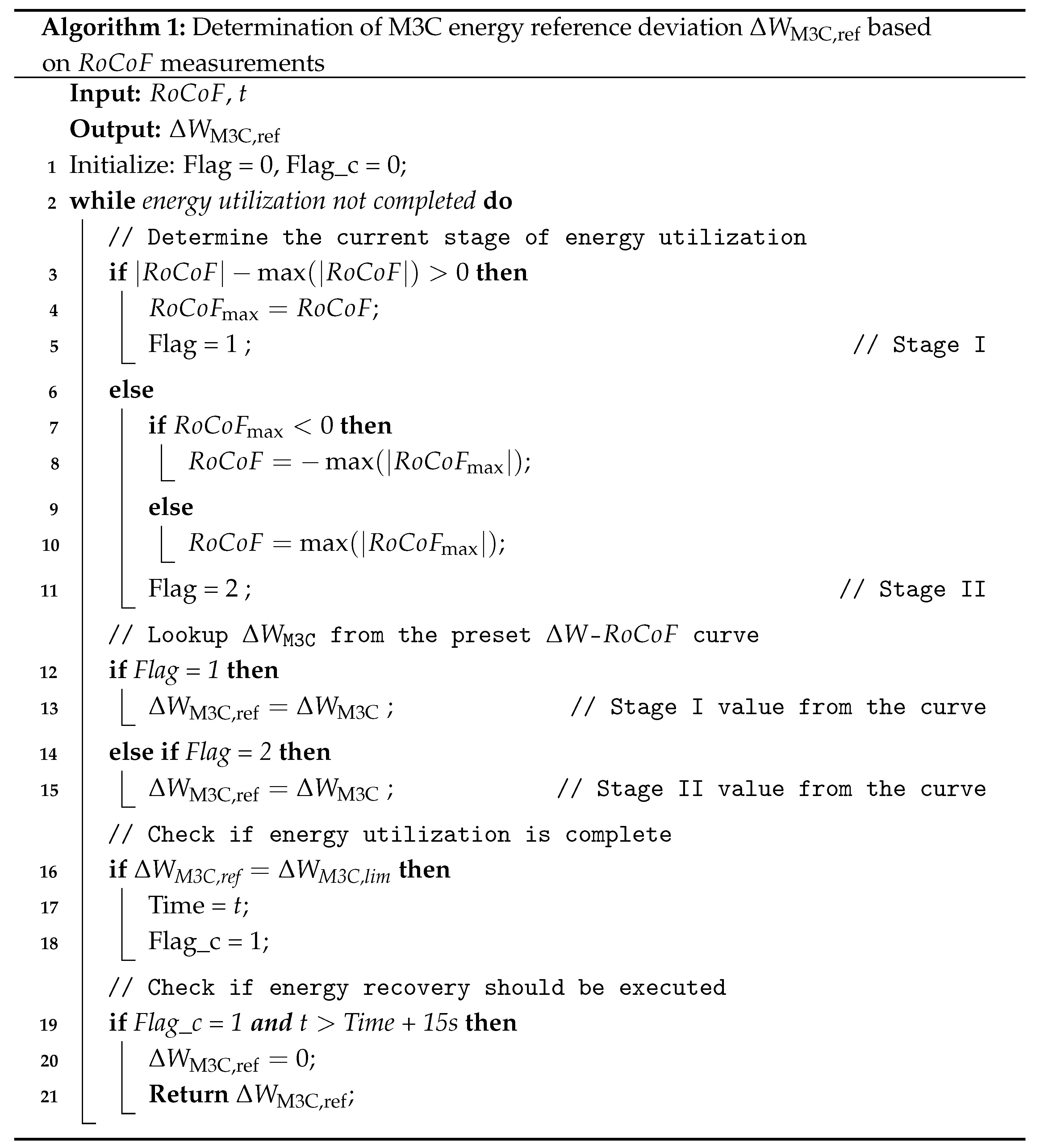

Algorithm 1 outlines the procedure for deriving the M3C energy reference deviation from the measurements and the preset – curve. Here, denotes the operator that identifies the maximum value from historical and current measurements. If the absolute value of real-time continues to exceed its historical maximum, the grid frequency has not yet reached . In this case, the Flag is set to 1, and the M3C executes the Stage I curve. Once the algorithm detects , the M3C switches to Stage II energy utilization strategy, where is obtained from the cubic curve.

Moreover, to prevent reverse increases in caused by unexpected non-monotonic behavior of the curve in Stage II, a one-directional constraint method is designed (Algorithm 2). This method records the historical maximum and compares it with the curve-derived values to ensure that always evolves monotonically along the – curve, as indicated by the arrows in Figure 9a. Thus, energy oscillations caused by non-monotonic are avoided. As shown in Figure 6, Algorithm 2 outputs the constrained energy reference , which is added to the initial M3C energy and passed through a slope limiter to generate the reference required by the M3C energy control framework introduced in Section 2.

Once Stage II utilization is completed, the M3C reaches its maximum or minimum adjustable energy and can no longer provide inertia support. To address this, a delay-based energy recovery strategy is employed to restore the M3C arm capacitor voltages to their nominal value. Based on the study in [8], a recommended time constant of 15 s is applied for stable grid frequency. Thus, after 15 s of reaching the maximum energy utilization limit, the converter initiates recovery control as follows:

3.2. Frequency-Mapped Transmission of Grid Inertia Information

Considering the limited energy absorption and release capability of the converter arm capacitors, the inertia constant of M3C is typically only 200–300 ms. Therefore, relying solely on the M3C’s internal energy is often insufficient to provide adequate inertial power support to the grid [30,31]. In this context, the mechanical rotational inertia of offshore wind turbines can serve as a supplementary source. However, in conventional LFAC systems, the M3C low-frequency side maintains a constant frequency, preventing offshore wind turbines located tens to hundreds of kilometers away from the shore from obtaining real-time grid frequency information [4]. To address this, a dual-side frequency mapping-based inertial support control strategy for offshore wind farms is proposed, leveraging the M3C dual-port grid-forming control. The low-frequency side reference of M3C can be expressed as

where is the mapping coefficient between the grid frequency and the M3C low-frequency side and is the nominal low-frequency value. Equation (26) ensures that the M3C low-frequency side is no longer fixed as in conventional LFAC systems but dynamically adjusts in real time according to the grid frequency deviation. As a result, offshore wind turbines can detect the frequency at the offshore connection point and generate a corresponding inertial response.

4. Simulation Verification

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed M3C dual-port grid-forming control method, a M3C-LFAC simulation system is established on the MATLAB/Simulink platform. The simulation parameters are listed in Table 1. The simulation setup is illustrated in Figure 6, where the offshore wind turbines operate as grid-following units.

Table 1.

Simulation parameters of the system.

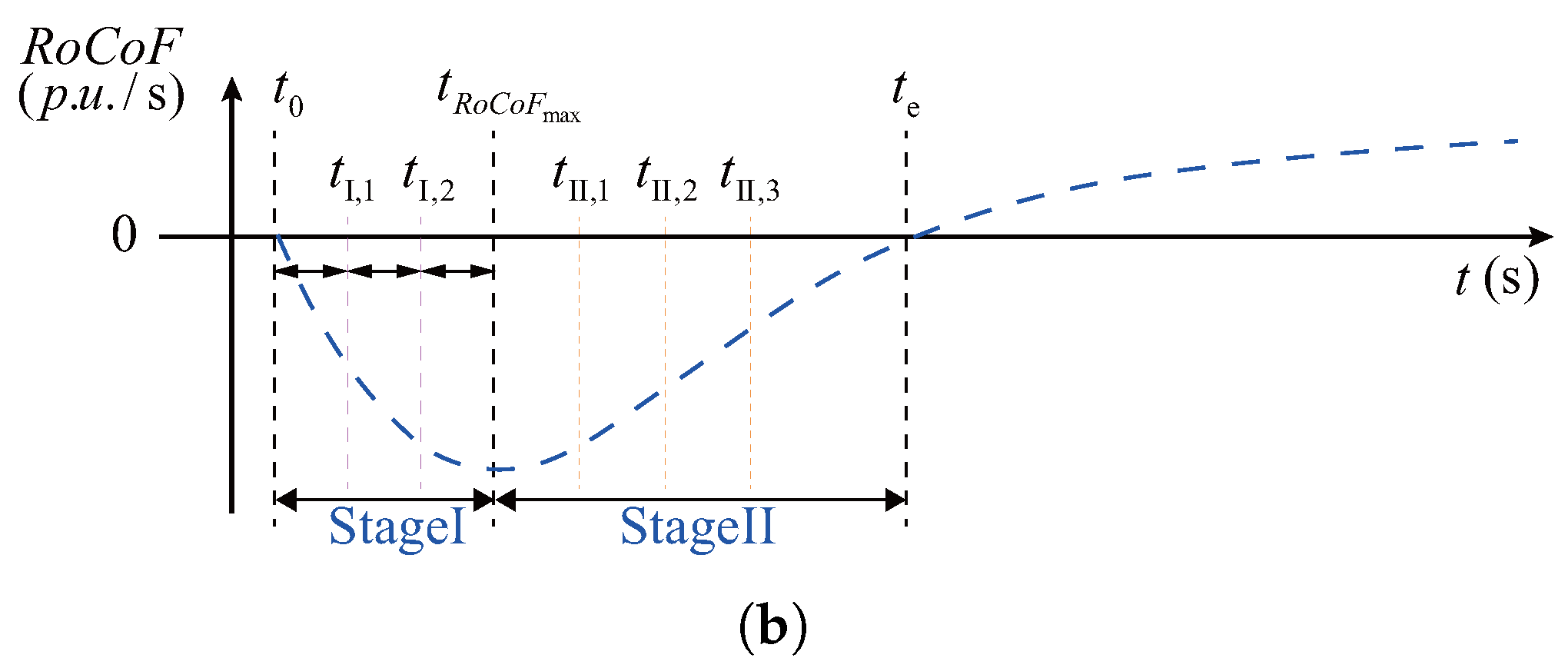

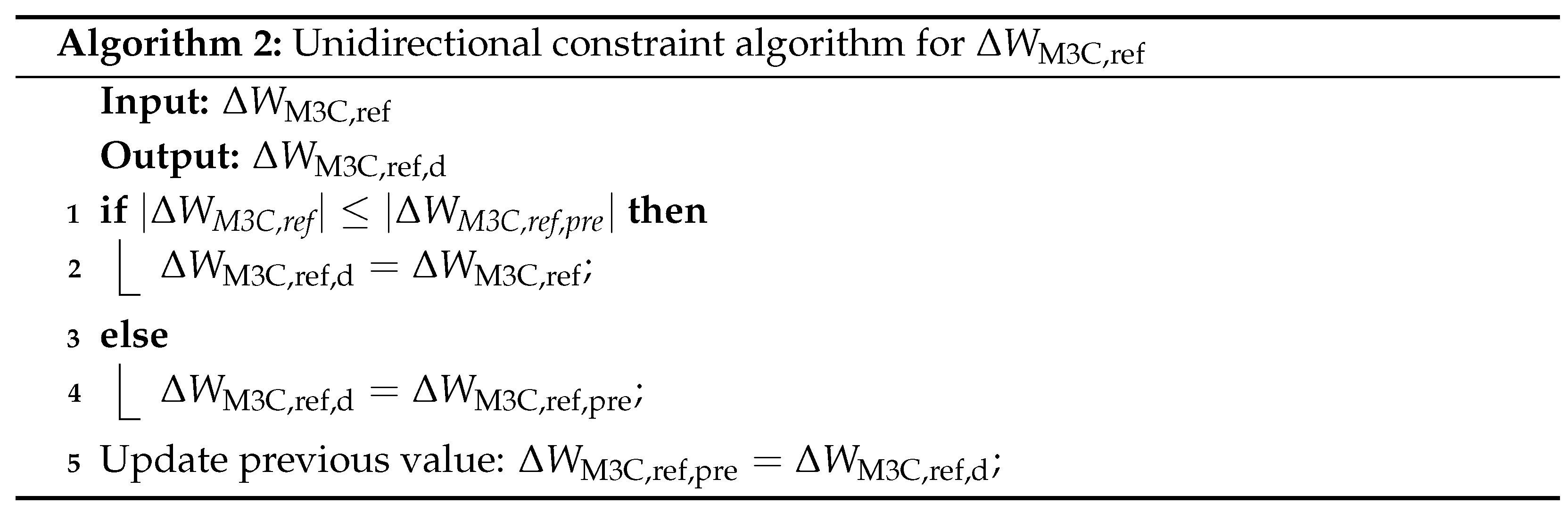

Figure 10 shows the simulation results of the total converter energy and the grid-side power under different values of the droop coefficient . In the simulation, the power injected by the offshore wind turbine into the M3C is kept constant at 0.2 p.u., while at s, the reference energy is increased from 1 p.u. to 1.2 p.u. to emulate a rise in the onshore grid frequency and the corresponding absorption of excess grid power by the M3C. According to Equation (11), a smaller corresponds to a smaller equivalent inertia time constant of the M3C, which results in a slower energy regulation response. It can be observed that as decreases, the time required for to reach becomes longer. Conversely, an excessively large causes an overactive additional power response in the LFAC system, as shown in Figure 10b, leading to significant overshoot in the grid-side output power and oscillations in . Therefore, considering both energy response speed and overshoot, is set to 0.2 in this study.

Figure 10.

Responses of and under different values of .

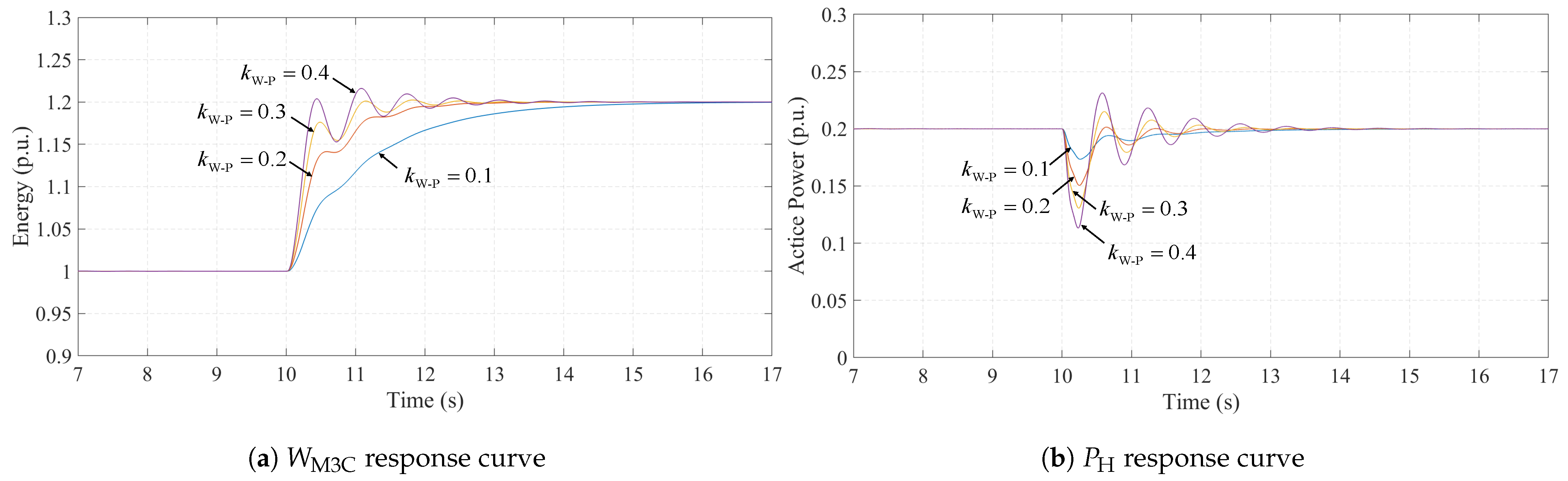

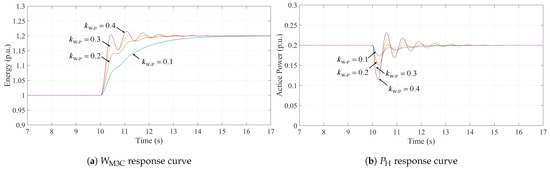

Figure 11 presents the simulation results of the proposed inertia support method based on optimized utilization of M3C energy. The simulation assumes a step increase in load of 0.1 p.u. of the LFAC system capacity at 15 s. Additionally, the synchronous generator in the grid is set to have a generation capacity ten times that of the LFAC system, with a grid inertia constant of 10 s. From the grid frequency curve shown in Figure 11a, it can be observed that the proposed method raises the frequency nadir from 49.984 Hz (without inertia support) to 49.987 Hz, reducing the maximum frequency deviation by 18.8%. Furthermore, Figure 11b illustrates the corresponding RoCoF curve. It can be seen that following the load disturbance, the proposed method effectively reduces the rate of change of frequency. The average RoCoF during the first swing interval decreases from −0.0095 Hz/s (without inertia support) to −0.0077 Hz/s, representing an 18.9% reduction, which verifies the effectiveness of utilizing M3C energy to provide grid inertia support in the LFAC system.

Figure 11.

Comparison of simulation results for grid inertia support using the proposed M3C energy-optimized method. (a) Grid frequency waveforms with the proposed method and without inertia support; (b) RoCoF waveforms; (c) M3C energy ; (d) M3C low-frequency side and grid-side active power.

Since the load disturbance is a step change, the frequency curve exhibits a parabolic shape, and RoCoF reaches at the instant of load increase. Therefore, the proposed method can detect at the initial stage of the inertia response, allowing M3C to immediately enter the second stage of energy-optimized utilization. Figure 11c shows the waveform of M3C energy . The slope limiter parameter for the energy reference is set to 0.2 p.u./s. During the inertia support period, gradually decreases from 1 p.u. to 0.7 p.u. The resulting power response is depicted in Figure 11d. It can be seen that even when the offshore wind power injection remains constant at 0.2 p.u. (not actively participating in inertia support), the release of M3C energy alone enables the grid-side output power to reach a maximum of 0.219 p.u., providing additional inertia power that effectively suppresses grid frequency decline and reduces RoCoF.

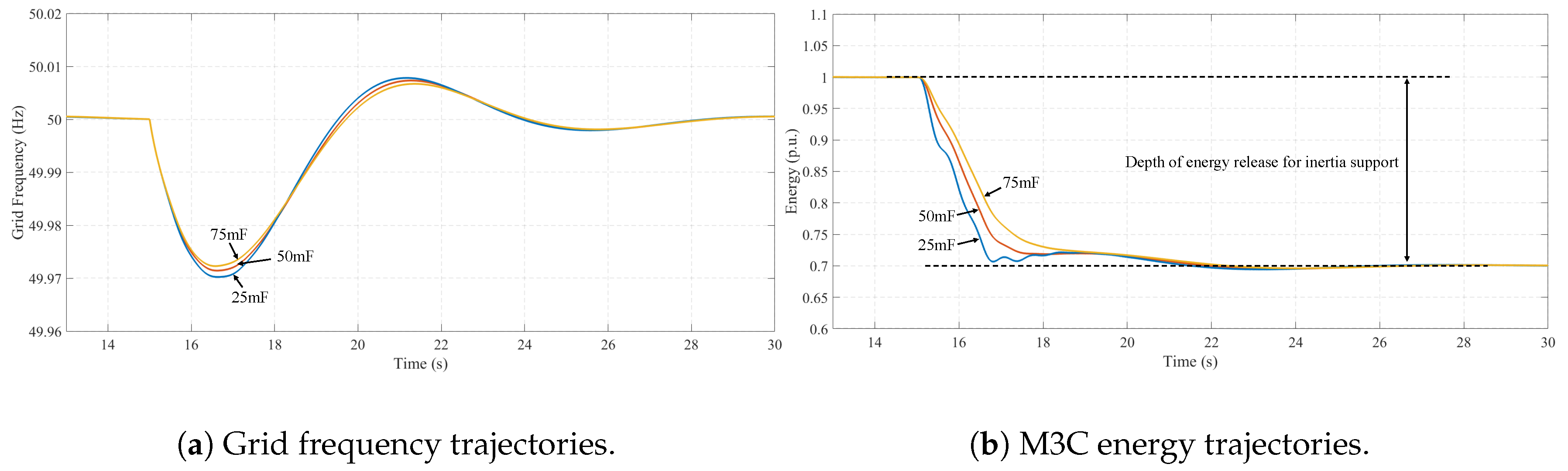

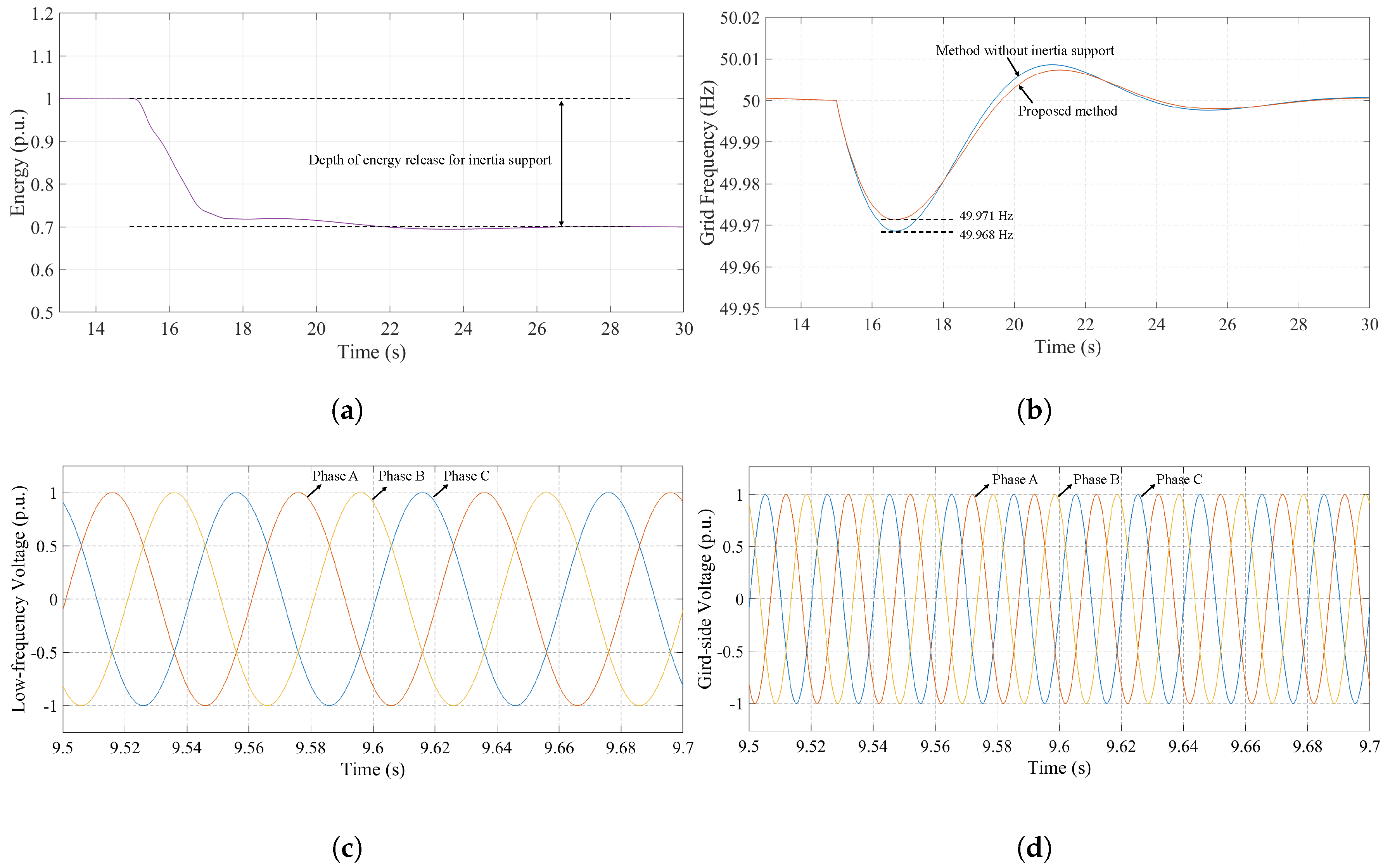

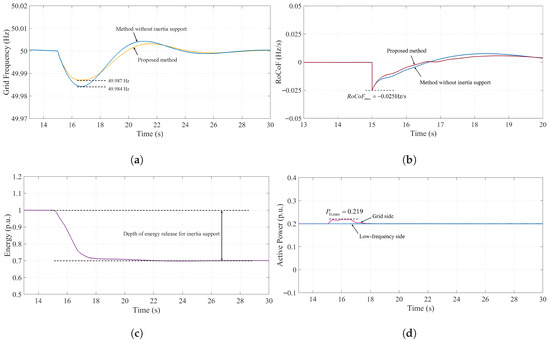

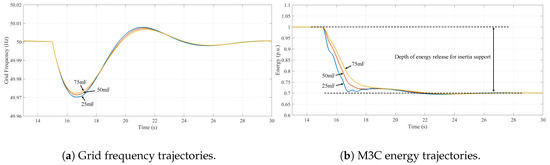

Figure 12a,b illustrate the grid frequency and M3C energy trajectories, respectively, for M3C submodule capacitances of 25 mF, 50 mF, and 75 mF. According to Equation (10), for the same depth of energy release, a larger results in a higher equivalent inertia constant for the M3C, thereby enhancing its contribution to grid inertial support. It is evident that increasing improves the M3C’s ability to mitigate the frequency nadir of the grid. Specifically, when is increased from 25 mF to 75 mF, the minimum grid frequency rises from 49.970 Hz to 49.972 Hz.

Figure 12.

Grid frequency and M3C energy under different submodule capacitances .

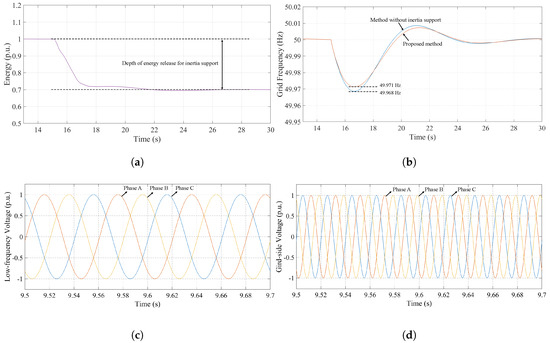

Figure 13 presents the simulation results of the proposed method when the load increment is increased to 0.2 p.u. under the same parameters as in the previous case. From the M3C energy curve in Figure 13a, it can be observed that even with different load increments, the maximum utilization of remains consistently at 0.3 p.u., as in the previous experiment. This verifies the effectiveness of the proposed M3C energy optimization strategy: regardless of the grid load increment, the –RoCoF utilization curve ensures that the M3C energy is always maximized. From the grid frequency waveform in Figure 13b, the minimum frequency increases from 49.968 Hz (without support) to 49.971 Hz with the proposed method. Under the 0.3 p.u. energy utilization condition, the maximum frequency deviation is reduced by 9.4%. Furthermore, Figure 13c,d show the output voltage waveforms at the 16.67 Hz low-frequency side and the 50 Hz grid-frequency side, respectively. These results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed method in actively constructing voltages on both sides.

Figure 13.

Simulation results of the proposed method under a 0.2 p.u. load increment. (a) M3C energy curve; (b) Grid frequency waveform; (c) Low-frequency side (16.67 Hz) output voltage waveform; (d) Grid-frequency side (50 Hz) output voltage waveform.

Table 2 summarizes the inertial support characteristics of different LFAC schemes. In the proposed method, the M3C is equipped with dual-port grid-forming capability and independent regulation of the capacitor-stored energy. As a result, its inertia is sourced from both the WTGs and the M3C itself. Moreover, the proposed scheme can independently control the voltage of the low-frequency link, eliminating the need for a communication system. Even if the WTGs fail to provide an inertial response due to unforeseen circumstances, the M3C can utilize its internal energy to suppress grid frequency deviations, endowing the proposed method with exceptionally high robustness against disturbances.

Table 2.

Comparison of different LFAC inertial support schemes.

5. Conclusions

In response to the conventional M3C-LFAC system’s vulnerability to PLL stability issues under weak grid conditions, this paper proposes an M3C-based dual-port grid-forming control strategy equipped with an energy synchronization loop. This method enables autonomous synchronization between the M3C and the grid without relying on a PLL while actively constructing a 16.667 Hz voltage on the low-frequency side to support offshore wind turbine operation. Building upon this foundation, a novel inertia support scheme based on M3C energy control is introduced. Furthermore, to address the limitation that a fixed inertia constant cannot ensure full utilization of the M3C arm energy under varying grid frequency disturbances, an energy-optimized inertia support method based on a cubic –RoCoF curve is proposed. Simulation results demonstrate that under different load disturbances, the M3C-LFAC system can consistently release energy to the same depth, thereby achieving maximized inertia support for the grid. The maximum frequency deviation of the grid is reduced by more than 9%, while the average RoCoF within the first frequency swing is reduced by over 18%, validating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and J.L.; methodology, C.W.; validation, W.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.L.; writing—review and editing, Q.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Zhejiang Electric Power Co., Ltd., “Coordinated Control Technology of Integrated Onshore–Offshore Wind Power with Quasi-Synchronous Active Support” (Grant No. B311DS24001B), and by the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, “Construction Method and Application of a Techno-Economic and Flexible-HVDC-Connection Compact Converter Station for Islanded Renewable Energy Sources Consumption” (Grant No. 52307210).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Junchao Ma, Jianing Liu, Chenxu Wang and Wen Hua were employed by the company State Grid Zhejiang Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Vilmann, B.; Randewijk, P.J.; Jóhannsson, H.; Hjerrild, J.; Khalil, A. Frequency and Voltage Compliance Capabilities of Grid-Forming Wind Turbines in Offshore Wind Farms in Weak AC Grids. Electronics 2023, 12, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imgart, P.; Narula, A.; Bongiorno, M.; Beza, M.; Svensson, J.R. External Inertia Emulation to Facilitate Active-Power Limitation in Grid-Forming Converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 9145–9156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struwe, J.; Wrede, H.; Vennegeerts, H. Validation Aspects for Grid-Forming Converters Based on System Characteristics and Inertia Impact. Energies 2023, 16, 7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, H.; Li, G.; Xin, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y. A Novel Coordinated Control Strategy for Frequency Regulation of MMC-HVDC Connecting Offshore Wind Farms. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2024, 15, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cabero, A.; Roldán-Pérez, J.; Prodanovic, M.; Suul, J.A.; D’Arco, S. Coupling of AC Grids via VSC-HVDC Interconnections for Oscillation Damping Based on Differential and Common Power Control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 6548–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabsha, M.M.; Rather, Z.H. A New Control Scheme for Fast Frequency Support From HVDC Connected Offshore Wind Farm in Low-Inertia System. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2020, 11, 1829–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, W.; Tai, N.; Yu, M.; Li, R.; Li, C. An Adaptive Inertia Transferring Control Scheme for Interconnected Offshore-Platform Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2024, 39, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiang, W.; He, Y.; Wen, J. Optimal Energy Utilization of MMC-HVDC System Integrating Offshore Wind Farms for Onshore Weak Grid Inertia Support. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Li, R.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.; Cai, X. Approach to Inertial Compensation of HVdc Offshore Wind Farms by MMC with Ultracapacitor Energy Storage Integration. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 12988–12998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yan, S.; Wu, K.; Ning, L.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. Comparative economic analysis of low frequency AC transmission system for the integration of large offshore wind farms. Renew. Energy 2021, 179, 1955–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibaceta, E.; Diaz, M.; Rajendran, S.; Arias, Y.; Cárdenas, R.; Rodriguez, J. Experimental Assessment of a Decentralized Control Strategy for a Back-to-Back Modular Multilevel Converter Operating in Low-Frequency AC Transmission. Processes 2024, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tameemi, M.; Liu, J.; Bevrani, H.; Ise, T. A Dual VSG-Based M3C Control Scheme for Frequency Regulation Support of a Remote AC Grid Via Low-Frequency AC Transmission System. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 66085–66094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z. Electromechanical Transient Modeling of the Low-Frequency AC System with Modular Multilevel Matrix Converter Stations. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Xu, Z. Modeling and Control of Modular Multilevel Matrix Converter for Low-Frequency AC Transmission. Energies 2023, 16, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, R.; Wang, X.; Liserre, M.; Lu, X.; Engelken, S. Grid-Forming Converters: Control Approaches, Grid-Synchronization, and Future Trends—A Review. IEEE Open J. Ind. Appl. 2021, 2, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Li, F.; Zhao, W. Stability Control for Grid-Connected Inverters Based on Hybrid-Mode of Grid-Following and Grid-Forming. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 10750–10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spier, D.W.; Prieto-Araujo, E.; López-Mestre, J.; Mehrjerdi, H.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O. On the Roles and Interactions of the MMC Internal Energy Balancing Degrees of Freedom for Three-Wire Three-Phase Connections. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 2023, 38, 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiang, W.; Wen, J. Dual Grid-Forming Control with Energy Regulation Capability of MMC-HVDC System Integrating Offshore Wind Farms and Weak Grids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Song, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Zou, C.; Qiao, X.; Liu, W. Transmission Topology and Control for Ultra-Large Offshore Wind Bases Integrating Multiple Offshore Low-Frequency AC Links and Onshore HVDC Link. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2024, 39, 2797–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, N.; Liu, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, K.; Li, Y. Low-Frequency Offshore Wind Power Transmission System with Dual-End Grid-Forming Control. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Renewable Energy and Power Engineering (REPE), Beijing, China, 25–27 September 2024; pp. 256–261, ISSN 2771-7011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xiang, W.; Lin, W.; Wen, J. Grid Forming Converters in Renewable Energy Sources Dominated Power Grid: Control Strategy, Stability, Application, and Challenges. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2021, 9, 1239–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Boroyevich, D.; Burgos, R.; Mattavelli, P.; Shen, Z. Analysis of D-Q Small-Signal Impedance of Grid-Tied Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, K.; Li, Y. Submodule Fault-Tolerant Control of Modular Multilevel Matrix Converters with Adaptive Optimum Common-Mode Voltage Injection. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 7548–7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z. Design and control of modular multilevel matrix converter with symmetrically integrated energy storage for low frequency AC system. Iet Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, W.; Tai, N.; Yu, M.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y. A Bidirectional Virtual Inertia Control Strategy for the Interconnected Converter of Standalone AC/DC Hybrid Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J.A.; Groß, D.; Araujo, E.P.; Bellmunt, O.G. Interconnecting Power Converter Control Role Assignment in Grids with Multiple AC and DC Subgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 2058–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo-Soler, J.; Nahalparvari, M.; Groß, D.; Prieto-Araujo, E.; Norrga, S.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O. Small-Signal Stability and Hardware Validation of Dual-Port Grid-Forming Interconnecting Power Converters in Hybrid AC/DC Grids. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2024, 13, 809–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Wang, K.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, L.; Li, Y. Optimized Branch Current Control of Modular Multilevel Matrix Converters Under Branch Fault Conditions. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 4578–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sanchez, E.; Prieto-Araujo, E.; Junyent-Ferre, A.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O. Analysis of MMC Energy-Based Control Structures for VSC-HVDC Links. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2018, 6, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Shi, J.; Yang, B. Adaptive integrated control strategy for MMC-MTDC transmission system considering dynamic frequency response and power sharing. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 147, 108858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, B.; Moursi, M.S.E.; Al-Durra, A.; El-Saadany, E.F. DC Inertia Support Scheme for MMCs in HVDC Transmission System Integrating Offshore Wind Farm. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery 2024, 39, 3374–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).