Abstract

This paper presents the design and experimental evaluation of a compact microstrip patch antenna and a 4 × 4 phased antenna array system tailored for Wi-Fi 6E applications, U-NII-5 band. A single inset-fed microstrip patch antenna was first optimized through full-wave simulations, achieving a resonant frequency of 5.96 GHz with a measured return loss of −17.5 dB and stable broadside radiation. Building on this element, a corporate-fed 4 × 4 array was implemented on an FR4 substrate, incorporating stepped-impedance transmission lines and λ/4 transformers to ensure equal power division and impedance matching across all ports. A 4-bit digital phase shifter, controlled by an ATmega328p microcontroller, was integrated to enable electronic beam steering. Simulated results demonstrated accurate beam control within ±28°, with directional gains above 13 dBi and minimal degradation compared to the broadside case. Over-the-air measurements validated these findings, showing main lobe steering at 0°, ±15°, +33° and −30° with peak gains between 7.8 and 11.5 dBi. The proposed design demonstrates a cost-effective and practical solution for Wi-Fi 6E phased array antennas, offering enhanced beamforming, improved spatial coverage, and reliable performance in next-generation wireless networks.

1. Introduction

With the rapid evolution of wireless communication technologies, Wi-Fi has progressed from the first IEEE 802.11 [1] standard in 1997 to Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be), driven by the increasing demand for multi-device connectivity, the Internet of Things (IoT), and high-bandwidth applications [2,3,4]. Among these, Wi-Fi 6E (an extension of IEEE 802.11ax) expands operation into the 5.925–7.125 GHz band, effectively alleviating congestion in the traditional 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands by providing an additional 1200 MHz of spectrum and more 160 MHz ultra-wide channels. However, the wider bandwidth also imposes significant challenges on antenna design. Microstrip patch antennas, widely adopted for their lightweight, low cost, and ease of fabrication, are limited by narrow bandwidth and low gain, making full-band coverage within the 6 GHz band difficult to achieve [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Consequently, the integration of advanced antenna architectures and beamforming techniques has become critical to improving the overall performance of Wi-Fi 6E.

Beamforming is a fundamental technique in modern wireless communication and radar systems, in which the amplitude and phase of individual antenna elements are carefully adjusted to achieve constructive and destructive interference, forming a directional radiation pattern with high gain and suppressed sidelobes [11,12]. This process concentrates radiated energy toward desired users, improving spectral efficiency and reducing interference. Beamforming has thus become central in multi-input multi-output (MIMO) and millimeter-wave (mmWave) technologies, and is widely applied in 5G, Wi-Fi 6E, and satellite communications. Beam-steering builds on beamforming and refers to dynamically adjusting the main lobe direction without physically rotating the antenna [13,14]. This is typically achieved through phase shifters, digital control circuits, or true-time-delay units, enabling rapid reconfiguration to support user tracking, adaptive coverage, and interference avoidance. In essence, beamforming generates a directional beam, whereas beam-steering controls its orientation. Their integration enhances communication reliability and meets next-generation demands for high capacity, low latency, and robust connectivity. Furthermore, phased array beamforming antennas, leveraging multiple elements and advanced signal processing, can focus energy to reduce interference and improve transmission efficiency [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Collectively, Wi-Fi 6E integrated with phased array beamforming establishes a key foundation for smart homes, smart offices, and other high-demand wireless services.

From a technical perspective, integrating phased arrays into Wi-Fi 6E requires careful RF and MAC-PHY co-design. To prevent grating lobes, element spacing must remain ≤λ/2 (approximately 25 mm at 6 GHz), making 4 × 4 or 8 × 8 arrays feasible in access point form factors [21,22]. Each element or subarray typically requires a phase shifter and, in some cases, dedicated amplification, which increases cost and thermal load; hybrid beamforming architectures help mitigate these challenges. The IEEE 802.11 standard already supports explicit beamforming feedback, enabling access points to optimize beam weights using channel state information (CSI) from clients. While access points can accommodate larger phased arrays for both uplink and downlink beam steering, most client devices remain limited to 2–4 elements due to space and power constraints. Current research includes compact 8–16 element indoor arrays achieving ±60° electronic steering with notable throughput improvements, multi-band shared-aperture designs covering both 5 GHz and 6 GHz, and machine learning-assisted beam selection methods that rapidly identify optimal beams from CSI without exhaustive scanning—an approach particularly promising for mobile Wi-Fi 6E applications [23,24].

Recent advances in beam-steering array antennas have focused on broadband operation, low-power design, flexible coverage, and reconfigurability. To overcome beam squint in conventional phase-shift steering, researchers have explored true-time-delay (TTD) and photonic beamforming. Wang et al. introduced a frequency-comb-based quasi-TTD beamformer for integrated communication and sensing [25], while Liebold et al. proposed a fractional-delay low-power TTD architecture [26]. Alavi et al. further enhanced photonic TTD performance in phased arrays, demonstrating potential for mmWave and terahertz systems [27]. Meanwhile, metasurface and reflectarray technologies enable versatile steering. Malik et al. presented a flexible conformal metasurface for MIMO [28], Paul et al. developed transparent reconfigurable units [29], and Dimousios et al. realized a polarization-reconfigurable reflectarray [30]. Zheng et al. reviewed wide-angle scanning strategies and highlighted metasurfaces and broadband compensation as key future directions [31]. In addition, Ahmed et al. demonstrated switchable branch-line couplers for scalable arrays with consistent amplitude [32]. Ding et al. [33] proposed a dual-polarized wide-beam passive antenna array that employs dual-polarized elements, etched reflectors, and improved radiating patches to achieve a wide beamwidth in the XOZ plane, thereby realizing stable high gain and broad coverage in the Wi-Fi 6E band. In addition, this article presents a comparison table of several recent works [4,21,33] on array antennas, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of four antenna designs.

In contrast, the work presented in this paper advances the field by introducing an active 4 × 4 phased-array architecture that integrates a 4-bit digital phase shifter controlled by a microcontroller, enabling electronic beam steering within a range of ±28°. Furthermore, the proposed design utilizes compact embedded-feed microstrip patches on an FR4 substrate, equipped with λ/4 transformers, thereby achieving flexible beam control and reliable gain performance across multiple steering angles, while maintaining cost-effective fabrication. Hence, the novelty of this study lies in integrating digital phase shifting technology into active beam steering for Wi-Fi 6E phased arrays, which complements the passive dual-polarized wide-beam approaches reported in the literature and highlights the contribution of our work to next-generation adaptive wireless communication systems.

2. Phase Shifting Array Antenna Design and Geometry

2.1. Single Microstrip Patch Line Antenna

The foundational design of the proposed microstrip line antenna is based on the computational methodology presented in [6,10]. A rectangular patch configuration is adopted, and full-wave simulations are carried out using Ansys HFSS to evaluate the impact of critical structural parameters—including patch length (L), width (W), and the inset feed gap (g)—on the antenna’s resonant frequency and impedance bandwidth. Through systematic parametric analysis, the optimal dimensions are extracted to ensure stable radiation characteristics and broadband operation while maintaining compactness at the designated 6 GHz frequency band. The antenna consists of three main parts: a rectangular metallic radiating patch on the top surface, a dielectric substrate layer, and a conducting ground plane at the bottom.

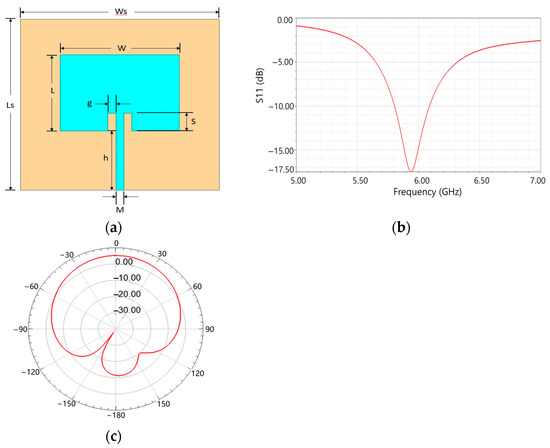

The proposed antenna, as depicted in Figure 1, is realized as a compact microstrip-fed rectangular patch radiator specifically optimized for 6 GHz band applications. Excitation is provided by a microstrip feedline that is coupled to the patch through a finely tuned inset structure. To enhance impedance matching and resonance stability, a narrow gap g and offset distance M are incorporated at the feed transition, while the inset depth h is optimized to minimize reflection loss at the target frequency. In addition, the slot width S is adjusted to fine-tune the input impedance and optimize the bandwidth. The substrate dimensions (Ls × Ws) provide a sufficiently large ground plane area to stabilize radiation characteristics, while maintaining a compact footprint well-suited for integration into modern wireless communication modules. The final optimized parameters of the antenna are summarized in Table 2, confirming its compact size and suitability for high-frequency operation.

Figure 1.

The proposed single microstrip line antenna: (a) antenna structure; (b) simulated return loss (S11); (c) simulated radiation pattern.

Table 2.

Parameters of the proposed single microstrip line antenna.

The performance of the proposed antenna is characterized in terms of its return loss and radiation pattern, as depicted in Figure 1b,c. The simulated S11 response in Figure 1b demonstrates a well-defined resonance centered at 5.96 GHz, where the return loss reaches approximately −17.50 dB, indicating excellent impedance matching and efficient power transfer at the design frequency. The −10 dB bandwidth extends across a range of about 5.70–6.10 GHz, confirming the antenna’s capability to support wideband operation within the sub-6 GHz spectrum. Such performance ensures stable matching characteristics suitable for wireless applications, including Wi-Fi 6E and emerging 5G systems. Complementarily, the radiation pattern in Figure 1c illustrates the antenna’s directional behavior at resonance, with a clear broadside main lobe and suppressed side lobes. The front-to-back radiation ratio is maintained at a moderate level, while cross-polarization components remain low compared to co-polarization, thereby enhancing polarization purity. This combination of wideband impedance matching and stable directional radiation validates the effectiveness of the antenna design for modern communication systems, ensuring both high radiation efficiency and reliable performance across the target operating band.

2.2. The Array Antenna Feed Network and Power Divider

The width of the feed line plays a critical role in the design of both single patch and array antenna configurations, as it directly influences impedance matching and power distribution [34,35]. The 4 × 4 patch array antenna is designed based on the configuration of a single patch element, where the width and length of the patch and feed lines can be determined using analytical expressions. Specifically, the characteristic impedance of a microstrip line can be expressed as

where εr is the substrate dielectric constant, L is the effective length, and W is the width of the transmission line. For inset-fed structures, the normalized feed position can be obtained using

where Z0 is the reference impedance, and Z1 is the transformed impedance. The transformed impedance itself is given by

According to (1)–(3), a quarter-wavelength section with an impedance of approximately 70.7 Ω serves as an impedance transformer to match 100 Ω and 50 Ω transmission lines. In the proposed 4 × 4 array configuration, each patch element is separated by two-thirds of a wavelength. Due to the use of inset feeding, the 50 Ω line is divided into two 100 Ω microstrip lines, thereby ensuring equal power and phase distribution among the array elements, which results in a uniform radiation aperture. The inset length y0, required for impedance matching, is determined directly from Formulas (1)–(3).

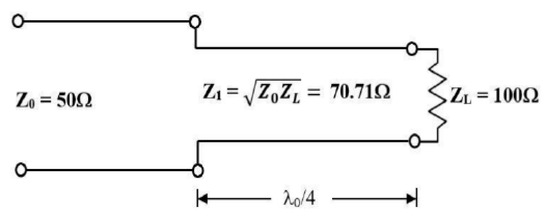

It follows that if the length of the matching line segment is an odd multiple of a quarter-wavelength, the characteristic impedance becomes the geometric mean of the load impedance and the line impedance, thereby enabling efficient impedance transformation. As illustrated in Figure 2, each array element feed line transitions between 50 Ω and 100 Ω through a quarter-wavelength transformer of 70.7 Ω. This ensures proper impedance matching at the output port, resulting in equal power distribution and stable array performance.

Figure 2.

Quarter-wavelength transformer.

Figure 3a illustrates the structure of a multi-level corporate-feed power divider designed to evenly distribute RF power from a single input port (Port 1) to sixteen output ports (Ports 2–17), thereby feeding a 4 × 4 microstrip patch antenna array. The divider incorporates three levels of power division, where each stage employs quarter-wavelength transmission line transformers to achieve impedance matching between cascaded feed sections. To suppress mutual coupling and maintain high port-to-port isolation, discrete isolation components (IC1–IC4) are introduced at critical junctions. This configuration ensures that all output ports exhibit equal amplitude and phase characteristics, which are essential for symmetrical array excitation. The stepped-impedance lines, together with λ/4 impedance transformers, are optimized for the design frequency, thereby minimizing insertion loss and ensuring efficient power transfer. In particular, a quarter-wavelength transformer with an impedance of 70.7 Ω is used to transition between 50 Ω feed lines and 100 Ω branch lines, guaranteeing smooth impedance transformation at each T-junction. As a result, the ideal power delivered to each output port is approximately −12 dB relative to the input.

Figure 3.

The proposed multi-port power divider: (a) structural layout; (b) simulated S-parameter results.

The feed network employs a corporate-feed structure to maintain equal power distribution while preserving phase coherence across all sixteen antenna elements. Each patch element is designed to present a nominal 50 Ω input impedance, enabling direct matching to the feed network. At the first branching level, a 70.7 Ω λ/4 transformer converts each 50 Ω element to 100 Ω, which is then combined in parallel to restore the impedance to 50 Ω along the trunk line. At higher branching levels, two 50 Ω trunks are paralleled to form 25 Ω; this is subsequently stepped back to 50 Ω through a 35.35 Ω λ/4 transformer, as indicated at the central feed junction. This hierarchical sequence of impedance transformations—50 Ω, 70.7 Ω, 100 Ω, and 35.35 Ω—ensures that the corporate-feed network achieves proper impedance matching from the input connector to all sixteen radiating elements, yielding a theoretically lossless power division scheme.

The physical implementation of the design on an FR4 substrate (εr = 4.4, tanδ = 0.025, thickness h = 1.6 mm) requires accurate calculation of microstrip widths, determined through the Hammerstad–Jensen model. The corresponding line widths are approximately 3.06 mm for 50 Ω, 1.60 mm for 70.7 Ω, 0.63 mm for 100 Ω, and 5.24 mm for 35.35 Ω. These dimensions provide reliable initial values, though fine-tuning via full-wave electromagnetic simulation (e.g., HFSS) is required to account for conductor thickness, etching tolerances, and dielectric losses at high frequencies. To further minimize insertion loss, transformer sections are fabricated with precise quarter-wavelength electrical lengths, T-junctions are designed with symmetry and short 100 Ω stubs to preserve balance, and unnecessary bends are avoided to reduce dissipative losses.

The input and output ports of the proposed power divider were designed with a characteristic impedance of 50 Ω and subsequently optimized using Ansys HFSS to achieve equal power division among the unit cells while maintaining minimal reflection loss. The simulated S-parameters are presented in Figure 3b. As observed, the reflection coefficient (S11) reaches a value of −14.06 dB at an operation frequency of 6.0 GHz, corresponding to an impedance bandwidth of approximately 21% under the −10 dB criterion. The transmission coefficients (S2,1–S17,1) exhibit uniform responses across the output ports, with an average insertion level of −14.15 dB, which indicates a power division loss of approximately 2.15 dB compared with the ideal −12 dB distribution. These results confirm that the power divider provides balanced output amplitudes with acceptable insertion loss and wideband impedance matching, demonstrating its suitability for feeding multi-element antenna arrays. Importantly, the proposed feed network and power divider architecture are highly compatible with Wi-Fi 6E systems operating in the 6 GHz band, where adaptive beamforming and multi-antenna techniques are vital for enhancing throughput, extending coverage, and mitigating interference in dense wireless environments.

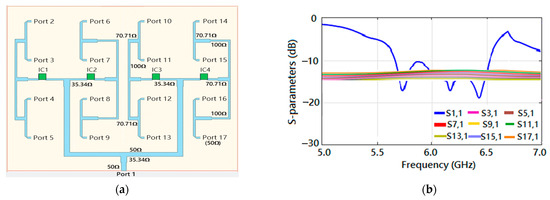

2.3. Digital Phase Shifter and Microcontroller

The Macom MAPS-010145 is a compact 4-bit digital phase shifter engineered to provide precise and discrete phase control across its operating bandwidth, and its block diagram is shown in Figure 4 [36,37]. The device incorporates four cascaded phase shift sections corresponding to −22.5°, −45°, −90°, and −180°, each activated by independent digital control inputs (D3–D6) as specified in the truth table, thereby enabling up to 16 unique phase states from 0° to 337.5° in 22.5° increments. Its internal switching architecture ensures stable, repeatable phase selection while preserving consistent amplitude performance across the designated frequency band. Functionally, the RF input signal propagates through the cascaded phase cells, with digital logic levels determining the exact phase configuration, making the device highly suitable for electronic beam steering in phased array antennas and adaptive wireless communication systems. Operating within the 3.5–6.0 GHz range, the MAPS-010145 is well-suited for broadband applications such as Wi-Fi 6E and sub-6 GHz 5G networks, offering an average insertion loss of about 5 dB with acceptable return loss, while supporting input powers up to +25 dBm for seamless integration into medium-power front-ends without the need for additional protection circuitry.

Figure 4.

Block diagram of the MAPS-010145 digital phase shifter and Atmega328 Microcontroller.

For control, the ATmega328p microprocessor on the Arduino UNO R3 functions as a cost-effective and versatile digital interface. It generates the required logic signals (D1–D6) to configure the desired phase states, as specified in the truth table presented in Table 3. Python 3.13.2 scripts running on a PC can issue high-level commands over USB serial to the Arduino, specifying the required phase for each channel. The Arduino interprets these commands, translates the requested phase shift into the correct digital word, and applies it to the phase shifter with precise timing. This combination of Python for high-level control and the ATmega328p for hardware interfacing provides a powerful yet simple solution for real-time phase adjustment, enabling efficient beamforming, RF alignment, and adaptive array applications.

Table 3.

Truth table of digital phase shifter.

Consider a uniform 4 × 4 planar array with inter-element spacing d = λ/2. The array steering law that maximizes coherent addition in the look direction (θ0, ϕ0) assigns to the (m,n)-th element (row m ∈ {0,1,2,3}, column n ∈ {0,1,2,3}) the phase

For azimuth ϕ0 = 0°, (4) reduces to a 1-D progression along columns,

so all rows share identical column phases. With d = λ/2 and θ0 = 30°, one obtains kd = π and sin30° = 0.5, hence the per-column increment is Δφ = −π/2= −90°:

Expressed in degrees modulo for digital phase shifters, the phase matrix is

(i.e., each row is identical). The corresponding complex weights are [1, −j, −1, +j] along each row. Any common phase offset added to all entries leaves the beampoint unchanged; however, non-uniform row-wise offsets would steer/elevate the beam undesirably. Using discrete 4-bit phase shifters with −22.5° resolution, the above phases are exact multiples and require no quantization error. For wider scan angles, maintain d ≤ λ/2 to suppress grating lobes and consider amplitude tapering (e.g., Taylor/Chebyshev) to further reduce sidelobes without altering the steering law in Equation (5).

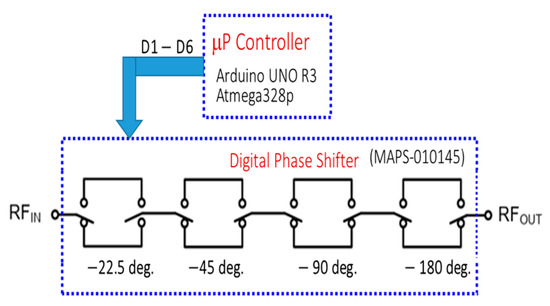

2.4. Microstrip Patch Antenna Array

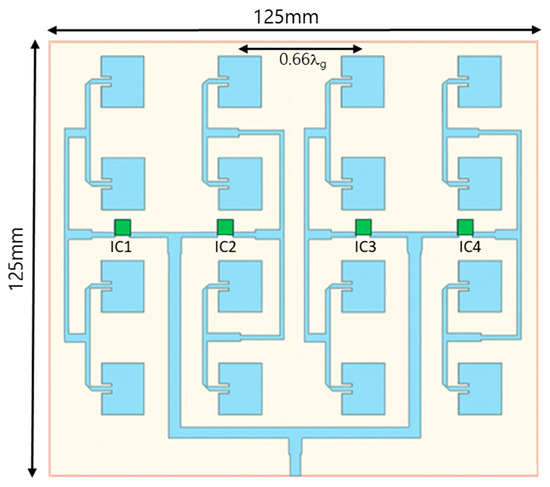

The design of a 4 × 4 digital phase-shift array antenna integrates advanced feed network engineering with precise phase control to achieve adaptive beamforming capabilities essential for modern wireless communication systems, as shown in Figure 5. The array consists of sixteen microstrip patch elements arranged in a square configuration of 125 mm × 125 mm, with inter-element spacing determined by the guided wavelength described as follows:

where c is the speed of light, f is the operating frequency, and εeff is the effective permittivity of the FR4 substrate. This spacing, typically around 0.66λg, ensures minimal mutual coupling while maintaining constructive interference in the desired beam direction. The radiating patches are designed for an input impedance of approximately 50 Ω, which is matched through a carefully constructed corporate-feed network. To evenly distribute RF power from a single feed port to all sixteen radiating elements, a multi-stage impedance transformation scheme is employed, incorporating quarter-wave transformers with characteristic impedances of 70.7 Ω and 35.35 Ω at different branching levels. This architecture guarantees that the input impedance is preserved at 50 Ω, minimizing reflection loss and maintaining uniform amplitude distribution across the array.

Figure 5.

Structure of the 4 × 4 antenna array.

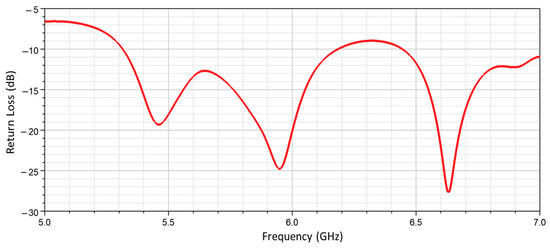

The simulated return loss response of the designed antenna within the frequency range of 5.0–7.0 GHz is illustrated in Figure 6. The curve reveals multiple resonant frequencies with effective impedance matching, as indicated by return loss values significantly below −10 dB at several points. A prominent resonance is observed near 5.96 GHz with a return loss of approximately −25 dB, signifying efficient power transfer and minimal reflection. The deepest resonance occurs around 6.65 GHz, achieving a return loss of nearly −28 dB, which further confirms excellent impedance matching. Two additional resonant dips appear in the ranges of 5.75–6.05 GHz and 6.55–6.73 GHz, both with return loss levels below −15 dB, ensuring reliable operation across multiple bands. These results demonstrate the antenna’s wideband capability with multiple resonant modes, making it highly suitable for sub-6 GHz wireless applications, including Wi-Fi 6E and next-generation 5G systems.

Figure 6.

Simulated return loss of the proposed 4 × 4 array antenna.

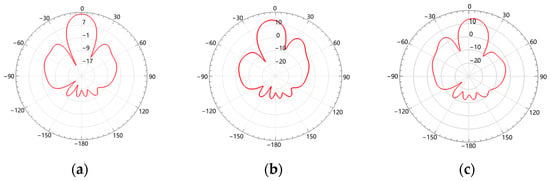

Figure 7a–e illustrate the simulated radiation patterns of the proposed 4 × 4 phased array antenna under different steering angles θ = 0°, −8°, −26°, +8°, +26° with fixed azimuth ϕ0 = 0°, realized using a 4-bit digital phase shifter (MAPS-010145). As shown in Figure 7a, the broadside case (θ0 = 0°) exhibits a symmetric main lobe centered at broadside with a directional gain of approximately 14.85 dBi and sidelobe levels below −1 dB. When the phase states are adjusted to steer the beam toward θ0 = −8° and −26°, shown in Figure 7b,c, the main lobe shifts toward the negative elevation direction with directional gains of about 13.5 dBi and 13 dBi, respectively, while the sidelobe structure becomes slightly more pronounced due to finite quantization of the 4-bit phase control. Conversely, for positive scan angles at θ0 = +8° and +26°, shown in Figure 7d,e, the main beam is successfully steered toward the desired directions with directional gains of about 13.65 dBi and 13.10 dB, respectively, and with gain reduction less than 2 dB compared to broadside (θ0 = 0°). These results confirm that the 4-bit digital shifter enables accurate and reconfigurable beam steering across a wide angular range, while maintaining a stable main lobe directional gain, although sidelobe asymmetry and quantization effects become more evident at larger scan angles.

Figure 7.

Simulated radiation patterns of the proposed 4 × 4 array antenna: (a) main lobe at 0°; (b) main lobe at −8°; (c) main lobe at +8°; (d) main lobe at −28°; (e) main lobe at +28°.

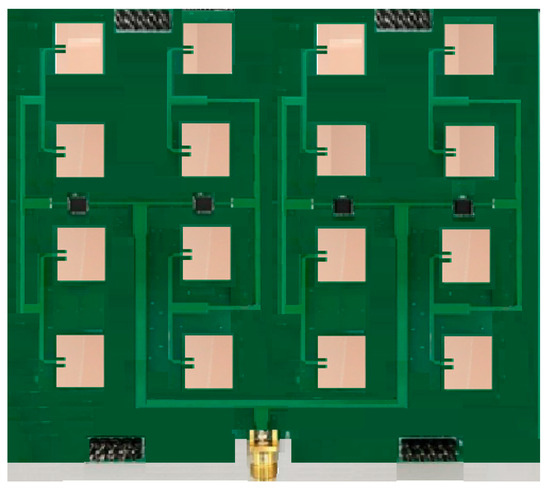

Figure 8 shows the fabricated 4 × 4 microstrip antenna array implemented on an FR4 substrate, integrated with a corporate-feed power divider network for equal signal distribution. The array consists of sixteen rectangular patch elements arranged in a uniform grid configuration, excited through a microstrip feed network designed to maintain impedance matching and phase consistency. The use of FR4 material (εr = 4.4, tanδ ≈ 0.025, thickness 1.6 mm) provides a cost-effective and manufacturable solution, though it introduces moderate dielectric loss at higher frequencies. The power divider is realized using cascaded quarter-wavelength impedance transformers to ensure balanced amplitude and in-phase excitation of each radiating element.

Figure 8.

The fabricated 4 × 4 structure antenna array with a power divider.

3. Experimental Setup and Results

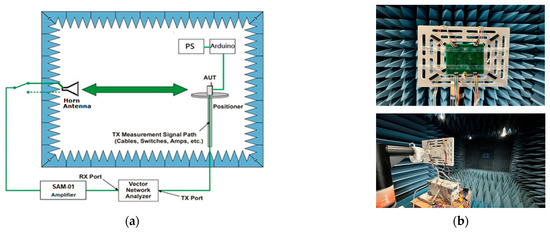

Over-the-air (OTA) antenna testing is a widely adopted methodology for evaluating the radiation performance of wireless communication antennas under realistic propagation conditions. As illustrated in Figure 9a, the antenna under test (AUT), together with an Arduino UNO R3 ATmega 328P microcontroller and a regulated power supply, is positioned at the center of a fully anechoic chamber as shown in Figure 9b to ensure an interference-free environment. The measurement process is coordinated using the EMQuest EMQ-220 software, which controls the positioner, including the azimuthal turntable (θ) and the elevation axis of the AUT (φ). Radiation patterns are acquired in three-dimensional space with a step resolution of 15°, and subsequently transformed into the required two-dimensional radiation profiles (X–Y, X–Z, and Y–Z planes) for analysis.

Figure 9.

Measurement setup as: (a) block diagram of measurement chamber; (b) far-field measurements in the anechoic chamber.

On the instrumentation side, the transmission path originates from the TX port of a Keysight E5080B vector network analyzer (VNA) and is amplified through an ETS SAM-01 amplifier prior to being delivered to the AUT. The radiated signal is then captured by a calibrated horn antenna, which is connected through an additional amplifier and routed to the RX port of the VNA. The collected measurement data are processed and analyzed by the EMQuest EMQ-220 software to compute the final radiation characteristics, including gain, efficiency, and pattern accuracy, thereby providing a comprehensive evaluation of the antenna’s performance in an over-the-air environment.

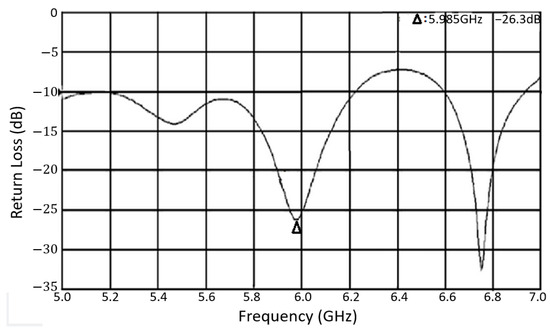

Figure 10 presents the measured return loss (S11) characteristics of the proposed antenna over the frequency range of 5.0–7.0 GHz. The antenna demonstrates two well-defined resonant frequencies, with the primary deep resonance observed at 5.985 GHz, achieving a return loss of approximately −26.30 dB, and a secondary deep resonance near 6.75 GHz, with a return loss exceeding −32.60 dB. These values indicate efficient impedance matching and minimal reflection at the resonant frequencies, signifying effective power transfer between the antenna and the feeding network.

Figure 10.

The measured return loss.

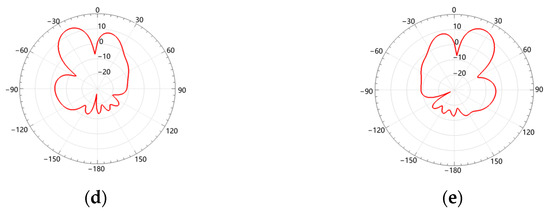

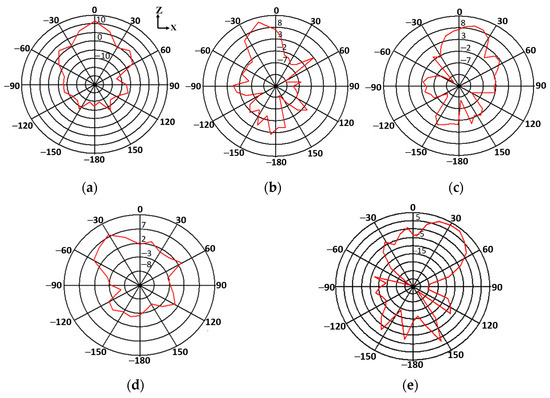

The measured radiation patterns of the proposed phased array antenna, as depicted in Figure 11a–e, provide a comprehensive evaluation of its far-field performance and beam steering capability across the designed operating range. To realize the measured beam patterns, a 4-bit digital phase shifter (MAPS-010145) was employed to implement quantized array phase control. The progressive phase shift along the column direction of the array is determined by Equation (2) for a desired steering angle (θ0, ϕ0), where θ denotes the elevation angle, and ϕ denotes the azimuth angle. For the broadside case (θ0 = 0°, ϕ0 = 0°), all elements are excited in-phase, resulting in a uniform 4 × 4 phase matrix of [0°]. When steering to θ0 = −15°, the required inter-column phase increment is approximately +46°, which is quantized to +45° in the digital phase shifter, yielding a row-wise progression of [0°, 45°, 90°, 135°]. Conversely, for θ = +15°, the calculated increment is −46°, quantized to −45°, giving [0°, 315°, 270°, 225°]. For larger steering angles, θ0 = −30° requires a phase step of approximately +90°, implemented as [0°, 90°, 180°, 270°], while θ0 = +30° corresponds to −90°, implemented as [0°, 270°, 180°, 90°]. In each case, the same phase progression is replicated across all four rows of the array since steering in the elevation plane requires only column-wise phase adjustments.

Figure 11.

Measured radiation patterns represented by the red lines at 6 GHz: (a) main lobe at 0°; (b) main lobe at −15°; (c) main lobe at +15°; (d) main lobe at −30°; (e) main lobe at +33°.

The corresponding measured results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed beam-steering approach. As shown in Figure 11a, the broadside radiation pattern exhibits a symmetric main lobe directed at 0°, with a peak gain of approximately 11.50 dBi, verifying correct in-phase excitation of the array. When the beam is steered toward negative elevation angles at θ = −15° and −30°, shown in Figure 11b,d, the main lobe shifts clearly toward the intended directions, achieving peak gains of 10.35 dBi and 7.78 dBi, respectively. Although a moderate reduction in gain is observed relative to the broadside case, stable directivity is maintained, demonstrating effective beam control in negative-angle steering. Conversely, for positive steering angles θ = +15° and +33°, shown in Figure 11c,e, the main beam is successfully directed upward, yielding peak gains of 9.66 dBi and 8.15 dBi, respectively. At larger scan angles, sidelobe levels and asymmetry become more pronounced due to aperture and quantization effects; however, the array consistently preserves main-lobe integrity with less than 3 dB variation across the steering range, confirming its robustness for adaptive beamforming applications.

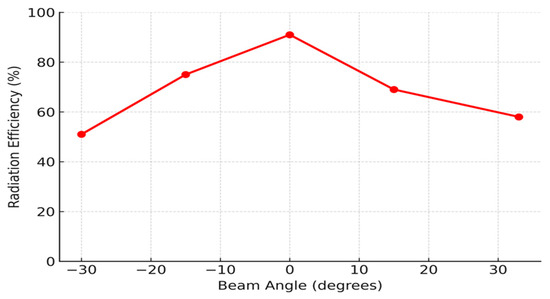

Figure 12 presents the measured radiation efficiency of the proposed 4 × 4 phased array antenna as a function of beam steering angle at 5.96 GHz. The measured data points correspond to −15°, −30°, 0°, +15°, and +33°, yielding efficiencies of 74%, 51%, 91%, 69%, and 58%, respectively. As observed, the antenna achieves its maximum efficiency of 91% at broadside (0°), while maintaining above 50% efficiency across the full steering range. This performance demonstrates the robustness of the feeding network and the compact inset-fed microstrip patch structure implemented on an FR4 substrate. Even at large scan angles, such as ±30°, the array sustains reasonable efficiency, highlighting the effectiveness of the integrated λ/4 transformers and digitally controlled phase shifters in mitigating losses.

Figure 12.

Radiation efficiency as a function of beam angle at 5.96 GHz.

Overall, the experimental results confirm that the quantized mapping of the 4-bit digital phase shifter provides sufficient resolution to approximate the required progressive phase values for beam steering about ±30°. The proposed phased array thereby achieves accurate and reconfigurable beam control while maintaining stable directional gain, effectively reproducing the measured radiation responses. These findings underscore the antenna’s capability to realize efficient electronic beam steering through digital phase control, establishing it as a strong candidate for next-generation adaptive wireless communication systems. Notably, the demonstrated beam-steering functionality is well aligned with the performance requirements of Wi-Fi 6E systems, where adaptive beamforming plays a critical role in enhancing data throughput, reducing co-channel interference, and improving spatial coverage across the newly allocated 6 GHz spectrum.

4. Conclusions

This work has presented the design and evaluation of a compact microstrip patch antenna and a 4 × 4 phased array configuration tailored for Wi-Fi 6E applications in the 5.925–6.425 GHz U-NII 5 band. The single patch antenna achieved a well-matched resonance at 5.96 GHz with a −17.5 dB return loss and stable directional radiation, confirming its suitability as the fundamental element for array integration. The proposed phased array, implemented on FR4 substrate and controlled by digital phase shifters, demonstrated effective beam steering across about ±30° with measured gains above 7.8 dBi. The corporate-feed network and impedance-matching techniques ensured uniform excitation and minimized reflection losses, while OTA measurements validated the array’s ability to provide high directivity and adaptive coverage. These results confirm that the proposed antenna system offers a cost-effective and practical solution for Wi-Fi 6E beamforming, supporting enhanced data throughput, reduced interference, and reliable performance in next-generation wireless networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-P.L.; Methodology, C.-Y.L.; Software, C.-Y.L.; Formal analysis, W.-P.L.; Data curation, C.-Y.L.; Writing—original draft, W.-P.L.; Supervision, W.-P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to Chang Gung University, Taiwan, for funding this research work through the project number (BMRP740).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bianchi, G. Performance analysis of the IEEE 802.11 distributed coordination function. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2000, 18, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfan, M.; Fabrice, T.; Michael, M. A survey of Wi-Fi 6: Technologies, advances, and challenges. Future Internet 2022, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolín-Arnau, L.M.; Orozco-Santos, F.; Sempere-Payá, V.; Silvestre-Blanes, J.; Albero-Albero, T.; Llacer-García, D. Exploring the potential of wi-fi in industrial environments: A comparative performance analysis of IEEE 802.11 standards. Telecom 2025, 6, 40–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H. Design of laptop computer antenna for Wi-Fi 6E band. Electronics 2025, 92, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A.S.B.; Ain, M.F.; Ahmad, Z.A.; Ullah, U.; Othman, M.; Hussin, R.; Rahman, M.F.A. Microstrip patch antenna: A review and the current state of the art. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 2019, 11, 510–524. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, S.; Fatin Muzamil, N.F.; Malek, N.A.; Motakabber, S. Design and analysis of a microstrip patch antenna at 7.5 GHz for X-band VSAT application. IIUM Eng. J. 2022, 23, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.; Verma, R.K.; Yashwanth, N.; Singh, R.K. A review on microstrip patch antenna parameters of different geometry and bandwidth enhancement techniques. Int. J. Microw. Wirel. Technol. 2022, 14, 652–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, K.P.; Jaiswal, R.C. Design and simulation of inset-feed microstrip patch antenna. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2023, 11, 859–864. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath, D.; Marichamy, P. On the design and analysis of multi-band micro-strip patch antenna for wireless body area network applications. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2025, 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavaraju, D.R.; Sukumar, R. Design and analysis of microstrip patch antennas for Sub-6 GHz applications. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2024, 11, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, M.A.; Aadil, F.; Ali, U.; Shah, U.A.; Ahmad, R.; Cho, S.-H. A review of beamforming microstrip patch antenna array for communication systems. Front. Mech. Eng. 2024, 10, 1288171–1288186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Akhtar, F.; Riaz, S.; Ali, A.; Shah, S.A.A.; Golubkov, D. A phased array antenna with novel composite right/left-handed (CRLH) phase shifters for Wi-Fi 6 communication systems. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2085–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, H.; Handa, Y.; Tanaka, R.; Tamura, K.; Cha, J.; Ahn, C.-J. Hybrid beamforming structure using grouping with reduced number of phase shifters in multi-user MISO. Electronics 2024, 13, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Singh, R.; Al-Hassani, M.; Nguyen, T. Multi-band beamforming antenna system for Wi-Fi 6E and Wi-Fi 7. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2025, 73, 4567–4578. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Liu, P. Design of a compact 8×8 phased array antenna for Wi-Fi 6E access points. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 45678–45690. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, H.; Chen, T.; Lin, J.; Su, S. Compact asymmetric T-feed closed-slot antennas for 2.4/5/6 GHz Wi-Fi 6E devices. Electronics 2024, 13, 2430. [Google Scholar]

- Touhami, A.; Collaredy, S.; Sharaiha, A. Compact superdirective electronically-beam-switchable antenna array for 5G indoor gateway. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Stockholm, Sweden, 30 March 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Hu, J.; Yang, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y. Miniaturized wide scanning angle phased array using compact radiating elements. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2022, 2022, 8769164–8769171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal-Katziri, M.; Fikes, A.; Hajimiri, A. Flexible active antenna arrays. NPJ Flex. Electron. 2022, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraso, U.E.; Sánchez-Azqueta, C.; Aldea, C.; Celma, S. A multi-band shared-aperture phased array antenna for next-generation WLAN applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 11234–11249. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, S.; Choudhary, R.; Singh, G.; Kumar, A. Design of 8×8 phased array antenna for sub-6 GHz 5G automotive wireless communications. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), Noida, India, 21–22 March 2024; pp. 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Saqib, N.U.; Hou, S.; Chae, S.H.; Jeon, S.-W. Reconfigurable intelligent surface aided hybrid beamforming: Optimal placement and beamforming design. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 12003–12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Farahbakhsh, A.; Sebak, A.-R. Ridge gap waveguide multilevel sequential feeding network for high-gain circularly polarized array antenna. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2019, 67, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Wide-band and wide-angle scanning phased array antenna for mobile communication systems. IEEE Open J. Antennas Propag. 2021, 2, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Frequency-comb-steered ultrawideband quasi-true-time-delay beamformer for integrated sensing and communication. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7571–7583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebold, Z.; Broughton, B.; Shemelya, C. Effects of fractional time delay as a low-power true time delay digital beamforming architecture. Electronics 2024, 13, 2723–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Kavanagh, K.; Brzozowski, M.; O’Connor, M.; Kelly, N.; Peters, F. Performance improvement of true time delay based photonic beamforming for phased array antennas. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 42, 1829–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, B.T.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Tang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhou, H. Beam steerable MIMO antenna based on conformal metasurface. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24086–24101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Sertel, K.; Nahar, N.K. Photonic beamforming for 5G and beyond: A review of true time delaydevices enabling ultra-wideband beamforming for mmwave communications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 75513–75526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimousios, T.D.; Mitilineos, S.A.; Panagiotou, S.C.; Capsalis, C.N. Design of a corner-reflector reactively controlled antenna for maximum directivity and multiple beam forming at 2.4 GHz. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2021, 59, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Sun, K.; Wu, J.; Li, T. Enabling beam-scanning antenna technologies for future networks: A review. ETT, 2025; Early View. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, F.H.; Khan, M.; Tariq, M.; Shah, S.; Ali, A.; Raza, M. Large-and small-scale beam-steering phased array systems based on switchable branch-line couplers. Sensors 2025, 25, 3714–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Rao, L.; Feng, B.; Sim, C.Y.D. A dual-polarized wide-beam antenna array with stable high gain for WiFi-6E (U-NII 6-GHz) communications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 114573–114583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovski, S.L.; Kolundžija, B.M. The impedance variation with feed position of a microstrip line-fed patch antenna. Serbian J. Electr. Eng. 2014, 11, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Celik, A.R. Effects of the Feedline Position on Microstrip Patch Antenna Performance. Eng. Technol. J. 2021, 6, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MACOM Inc. MAPS-010145: Digital Phase Shifter V4. In Datasheet; MACOM Technology Solutions: Lowell, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Microchip Technology Inc. ATmega328P—8-bit AVR Microcontroller. In Datasheet 7810D–AVR–01/15; Microchip Technology Inc.: Chandler, AZ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).