Abstract

Single-stage detectors have drawbacks of insufficient accuracy and poor coverage capability. YOLOF (You Only Look One-level Feature) has achieved better performance in this regard, but there is still room for improvement. To enhance the coverage capability for objects of different scales, we propose an improved single-stage object detector: Dq-YOLOF. We have designed an output encoder that employs a series of modules utilizing deformable convolution and SimAM (Simple Attention Module). This module replaces the dilated convolution in YOLOF. This design significantly improves the ability to express details. Simultaneously, we have redefined the sample selection strategy, which optimizes the quality of positive samples based on SimOTA. It can dynamically allocate positive samples according to their quality, reducing computational load and making it more suitable for small objects. Experiments conducted on the COCO 2017 dataset also verify the effectiveness of our method. Dq-YOLOF achieved 38.7 , 1.5 higher than YOLOF. To confirm performance improvements on small objects, our method was tested on urinary sediment and aerial drone datasets for generalization. Notably, it enhances performance while also lowering computational costs.

1. Introduction

With the rise of deep learning technology, the field of object detection has experienced a revolutionary breakthrough, with a wide range of uses including in image recognition [1], multimodality [2] and object tracking [3]. In the medical field, traditional urinary sediment detection is influenced by many factors, such as consuming significant human and material resources. Consequently, deep learning is gradually replacing traditional urinary sediment detection. However, in practical applications, it is necessary to find a proper balance between accuracy and computational efficiency to ensure that object detection technology meets speed requirements while maintaining high accuracy.

Current object detection techniques are divided into two main types: two-stage algorithms and one-stage algorithms. Compared to two-stage algorithms, one-stage detectors are faster, simpler, and more efficient. One-stage algorithms, such as YOLO (You Only Look Once) and SSD [4] (Single Shot MultiBox Detector), transform the object detection problem into a single regression problem by directly learning the category probabilities and bounding box coordinates of the objects. RetinaNet [5] uses focal loss to avoid the category imbalance problem and employs FPNs [6] (Feature Pyramid Networks) to handle multi-scale features. EfficientDet [7] is the current leader among single-stage detection algorithms, improving efficiency and accuracy through an effective network structure and BiFPN (Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network). Most current detectors, such as YOLOv3 [8] and FCOS [9] (Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detection), rely on FPNs. Thanks to the divide-and-conquer approach and feature fusion of FPNs, these detectors can achieve higher accuracy. However, despite the significant improvement in accuracy, the multiple-input–multiple-output encoder has limitations: FPNs make the network structure complex and increase memory usage and inference time, making them difficult to deploy on less capable machines.

YOLOF [10] (You Only Look One-level Feature) proposes a dilation encoder designed to achieve feature separation of FPNs by integrating multiple dilation residual blocks of different sizes, effectively addressing the problem of multi-scale object detection. However, YOLOF is a single-stage feature detector, and the dilation rate parameter of the dilated convolution within the dilation encoder increases the number of model parameters, resulting in an enlarged model that requires more computation. Moreover, the sensory field of the dilated convolution is affected by the dilation rate and becomes larger, which may lead to information loss or blurring, limiting the model’s ability to acquire global information and restricting feature learning.

The YOLOF backbone network loses small-object information during multiple down sampling. Moreover, the purpose of dilated convolution is to cover more objects on the current feature map, making small objects difficult to cover. Sample selection plays a key role in model training, and uniform matching of YOLOF uses the k nearest anchors as positive samples for each ground truth but ignores positive samples with an IoU (Intersection over Union) < 0.15. This approach allows all ground truths to obtain checkerboard boxes that fit their scale as positive samples. However, although this method can achieve high accuracy, it is not applicable to small objects. Therefore, in this paper, we mainly improve feature extraction and sample selection, and the contributions are as follows:

- In this study, a more efficient deformable convolution combined with SimAM is utilized by dynamically adjusting the convolution kernel. Accuracy improvement is achieved on the COCO2017 dataset while maintaining a balance in computational resource consumption.

- This study proposes a dynamic sample selection mechanism based on SimOTA (Similarity Overlap Threshold Assigner) improvement, which optimizes the selection process of positive samples and dynamically determines their number. This results in an effective balance of positive sample label assignments. The method shows significant improvement in detecting objects of different scales, especially small objects.

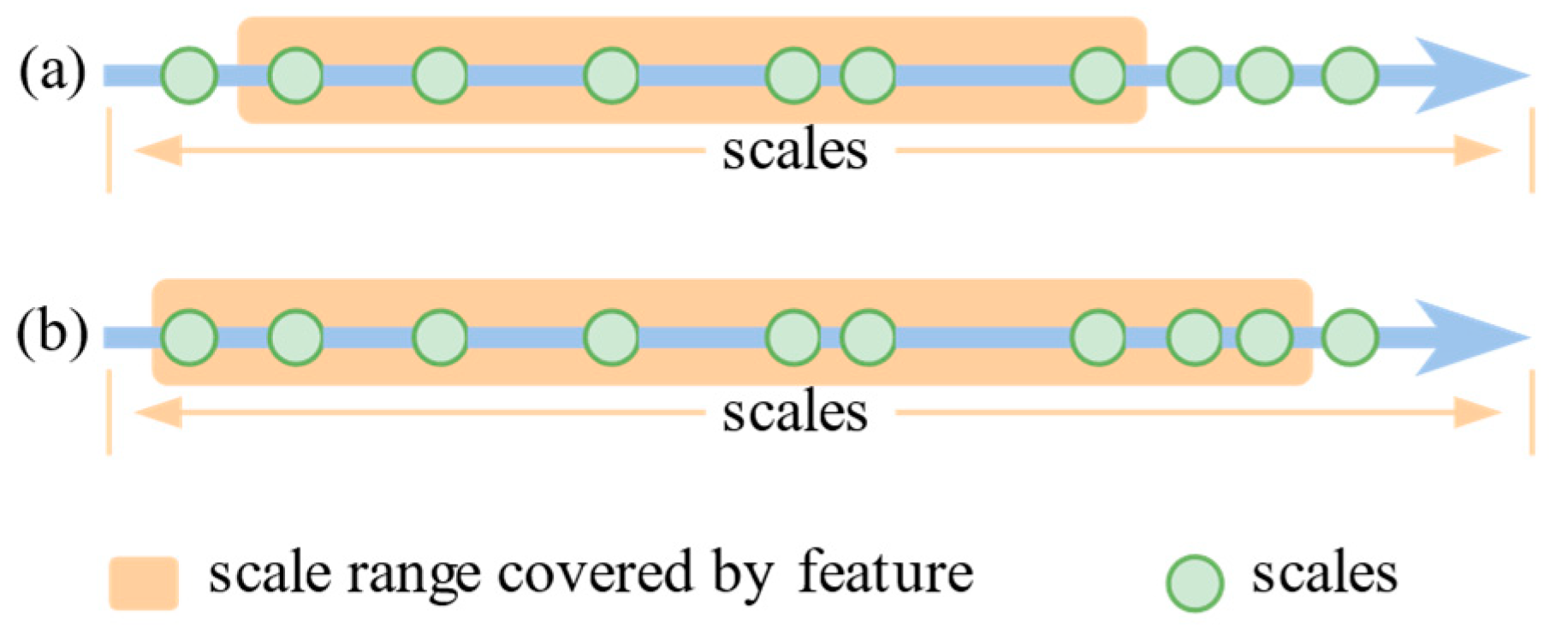

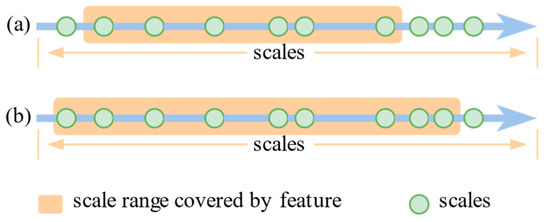

- The enhanced Dq-YOLOF is also validated on a specific urinary sediment dataset, and the experimental results demonstrate that the accuracy of Dq-YOLOF is improved across all scales and for various morphological objects, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. (a) is the receptive field coverage of YOLOF’s original method, which can cover features at multiple scales; (b) is the improved method, which further expands on YOLOF’s original coverage and improves on both small and large objects.

Figure 1. (a) is the receptive field coverage of YOLOF’s original method, which can cover features at multiple scales; (b) is the improved method, which further expands on YOLOF’s original coverage and improves on both small and large objects.

2. Related Works

2.1. Feature Extraction

Convolutional neural networks have demonstrated significant results in the fields of computer vision and deep learning. However, standard convolutional operations typically use convolutional kernels of fixed size and step size, limiting the ability to model objects with varying morphology. Several improved approaches address this problem. For example, grouped convolution [11] reduces the number of parameters by grouping them in channel dimensions and using a different convolution kernel for each grouping; depthwise separable convolution [12] further reduces the model parameters by dividing the convolution process into channel-by-channel and point-by-point convolution; and dilated convolution [13] increases the sensory field of the convolution operation by introducing an expansion rate. Nonetheless, these methods still perform convolution on a fixed square grid, which cannot fully match the morphology of real objects.

To overcome the above limitations, Dai et al. proposed the deformable convolution [14] network, an innovative convolutional network that adaptively adjusts the size and offset direction of the convolution kernel. When dealing with multi-scale and polymorphic objects, deformable convolution adapts to the size and aspect ratio of the object by dynamically adjusting the dimension and step size of the convolution kernel, thus achieving significant improvements in the accuracy and efficiency of object detection.

Recent research developments have seen the application of deformable convolution in various methods. For instance, Liu et al. [15] proposed a novel deformable convolution-based face modeling method, achieving adaptive capture of facial features by learning a deformable convolutional network. Additionally, Wang et al. [16] developed a method for image segmentation using deformable convolution, efficiently performing the segmentation task at different scales. These research results fully demonstrate the significant application potential of deformable convolution in complex visual tasks such as object detection and image segmentation.

On the other hand, the attention module can assign different weights to different channels or regions in the space, thus helping the model to focus on extracting more important information. The Transformer [17] architecture, through its self-attention mechanism, enhances the detection model’s ability to globally characterize the feature maps, which helps to moderate the model’s limitations in terms of perceptual range. DETR [18] employs a Transformer encoder to process the output of the last layer of the backbone network as well as the feature mapping embedded in the input query and locate the object entity in the Transformer decoder stage.

Existing attention mechanisms typically generate one- or two-dimensional weights in the channel or spatial dimensions, such as BAM [19] (Bottleneck Attention Module), which connects channel attention and spatial attention in parallel. This differs from CBAM [20] (Convolutional Block Attention Module), which connects both types of attention serially. However, during the generation process, each neuron or spatial location in each channel is treated with the same weight, limiting their learning ability. SimAM [21] is a unified weighted attention module that derives 3D attention weights for feature maps without requiring additional parameters. SimAM determines the attention weights directly by calculating the similarity between elements in the input sequences, thus avoiding the additional parameter learning process.

Together, deformable convolution and SimAM parameter-free attention are highly significant in object detection tasks. Deformable convolution can more accurately model objects with varying scales and aspect ratios by adaptively adjusting the size and step size of the convolution kernel, thereby enhancing the model’s adaptability and effectiveness. SimAM, as a parameter-free attention mechanism, determines the attention weights by calculating the similarity between elements in the input sequence, thus avoiding the need for additional parameter learning. The combination of these two techniques offers a more flexible and efficient solution for object detection tasks and plays a crucial role in our research work.

2.2. Sample Selection

Convolutional neural network-based object detection algorithms can be mainly categorized into anchor-based and anchor-free in terms of the selection of positive samples. For the task of object detection with multi-scale feature fusion, the anchor-free detector dispenses with the need to adjust the hyperparameters associated with the anchor, thus avoiding the large memory overhead required in calculating the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the real bounding box and the anchor box, and further enhancing the efficiency of training. For example, in the anchor-based detection method, YOLOv1 [22] selects the anchor boxes with the largest IoU, with the ground truth box as the positive sample. In contrast, adaptive training sample selection (ATSS [23]) is performed by calculating the L2 distance from each sampling point to the center of the ground truth box and retaining the first k points with the smallest distance. Subsequently, the IoU of these retained anchor points to the ground truth box is calculated, and the sum of the mean plus variance of these IoU is used as a threshold value, with only anchor points exceeding this threshold considered as positive samples.

In anchor-free detection methods, Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detector (FCOS) uses each point on the feature map that falls inside the true bounding box as a training sample and distinguishes between the foreground and the background based on whether the point is located inside the box. This approach reduces the number of hyperparameters and achieves high performance in single-stage detection without additional sophisticated techniques. SAPD [24] (Soft Anchor-Point Detector), in order to simultaneously achieve scale dimension and spatial dimension, proposes soft-weighted anchor points to generate a loss weight for each anchor point, and introduces soft-selected pyramid levels to weigh each feature layer. PP-YOLOE [25] (an evolved version of YOLO) employs a neck with CSPRepResStage and an EThead (Efficient Task-aligned Head), and leverages the TAL (Task-aligned Assignment) label assignment algorithm. However, in the task of object detection for single-scale features, the anchor-free detector is usually not advantageous in terms of its multi-scale object detection capability because of its inability to efficiently detect objects of different sizes in multiple feature map hierarchies.

In contrast, an anchor-based detector benefits from its predetermined a priori box, allowing each pixel in the feature map to detect objects at multiple scales. Moreover, the application of the anchor-based approach on a single-feature level does not lead to an additional increase in memory consumption. YOLOv2 [26] and YOLOv3 introduced anchor boxes where each grid cell produces three anchor boxes, and only the anchor box with the largest IoU to the ground truth box is responsible for predicting that ground truth box. This process employs a maximum IoU-matching strategy. Inspired by YOLOv3, PP-YOLOv1 [27] (An Effective and Efficient Implementation of Object Detector) did not use a complex backbone network or data augmentation techniques; it only employed a combination of tricks. PP-YOLOv2 [28] (a Practical Object Detector), built upon PP-YOLOv1, incorporates a Path Aggregation Network and utilizes the MISH (a Self Regularized Non-Monotonic Neural Activation Function) to enhance detector performance. In terms of loss calculation, PP-YOLOv2 computes it in the form of soft labels. For example, YOLOF performs object detection on a single-feature level by selecting the anchor points closest to each real bounding box as positive samples to improve training efficiency. Compared to FCOS, YOLOF sacrifices a certain amount of detection accuracy in exchange for faster detection. The dynamic sample-matching strategy allows the detector to dynamically adjust the number of positive samples during training.

SimOTA [29] is a well-known dynamic sample-matching strategy simplified and applied in YOLOX (You Only Look One-level eXtreme). The method first selects the top-k region proposals with the highest IoU with the ground truth box, then determines the number of positive samples based on these boxes, and selects the region proposal with the lowest loss as the relevant sample. SimOTA not only shortens training time but also reduces dependence on additional hyperparameters. In this study, we further enhance the efficacy of the sample quality selection strategy based on SimOTA. The method proposed in this paper aims to improve the accuracy of the detector while maintaining a balance between detection speed and memory consumption.

3. Approach

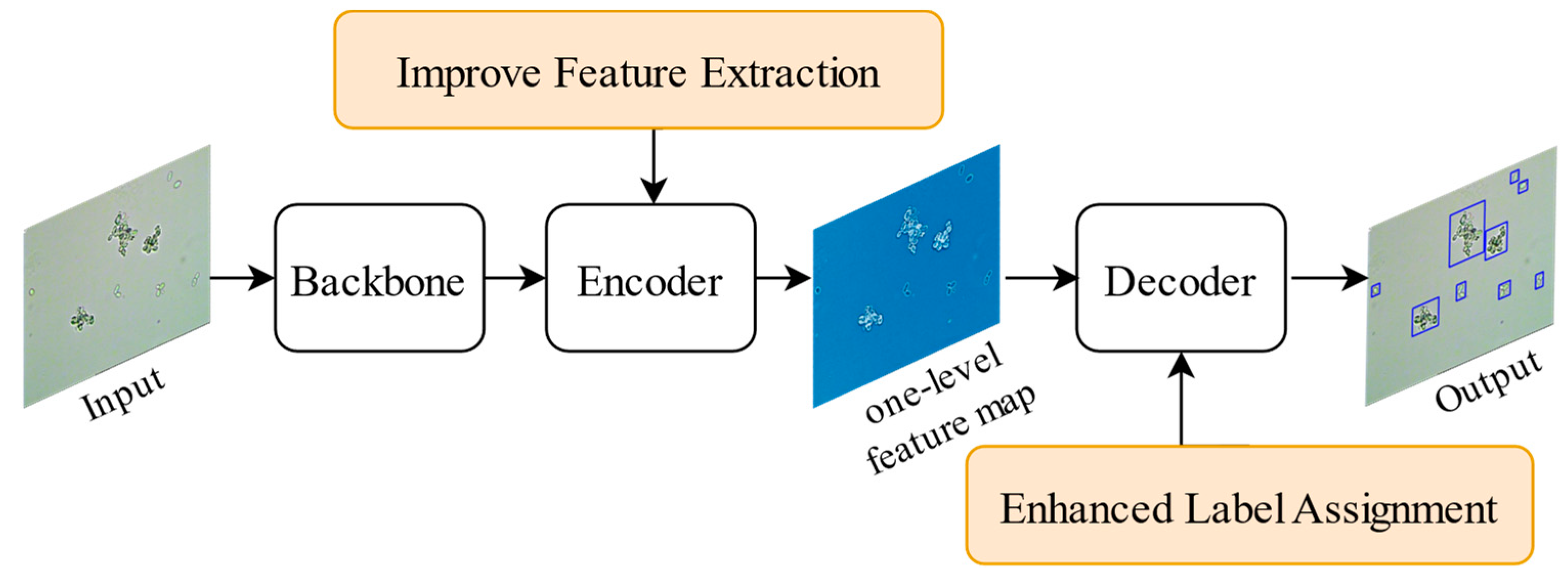

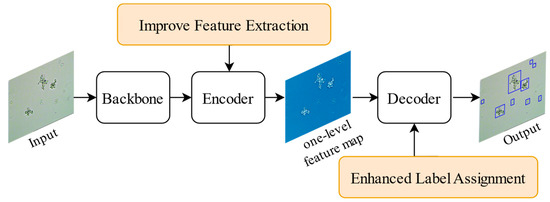

To address the challenges faced by single-stage feature detectors in capturing objects at different scales, this study optimizes the detection performance of YOLOF. By integrating a parallel deformable convolution module into the output encoder, the detector can dynamically adjust the sensory field size to more efficiently adapt to the diversity of object morphologies and poses in the image, facilitating the capture of multi-scale feature information. Additionally, more accurate label assignment is achieved through improvements based on the quality of positive samples. The enhanced quality of the positive samples provides the model with better learning objectives. Together, these improvements significantly enhance the performance of the detector. A process map of the method is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The figure shows the main process of our method, where we focused on improving the encoder and decoder.

3.1. Feature Extraction

YOLOF, a single-stage feature detector that discards the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) structure, performs poorly with objects of varying scales. This study enhances its output encoder by replacing the dilated convolution with a deformable convolution to capture feature information at different scales more efficiently, optimizing detection performance for multi-scale objects. This improvement significantly reduces the disparity in detection effectiveness between small and large objects, further enhancing the model’s applicability and robustness in complex scenarios.

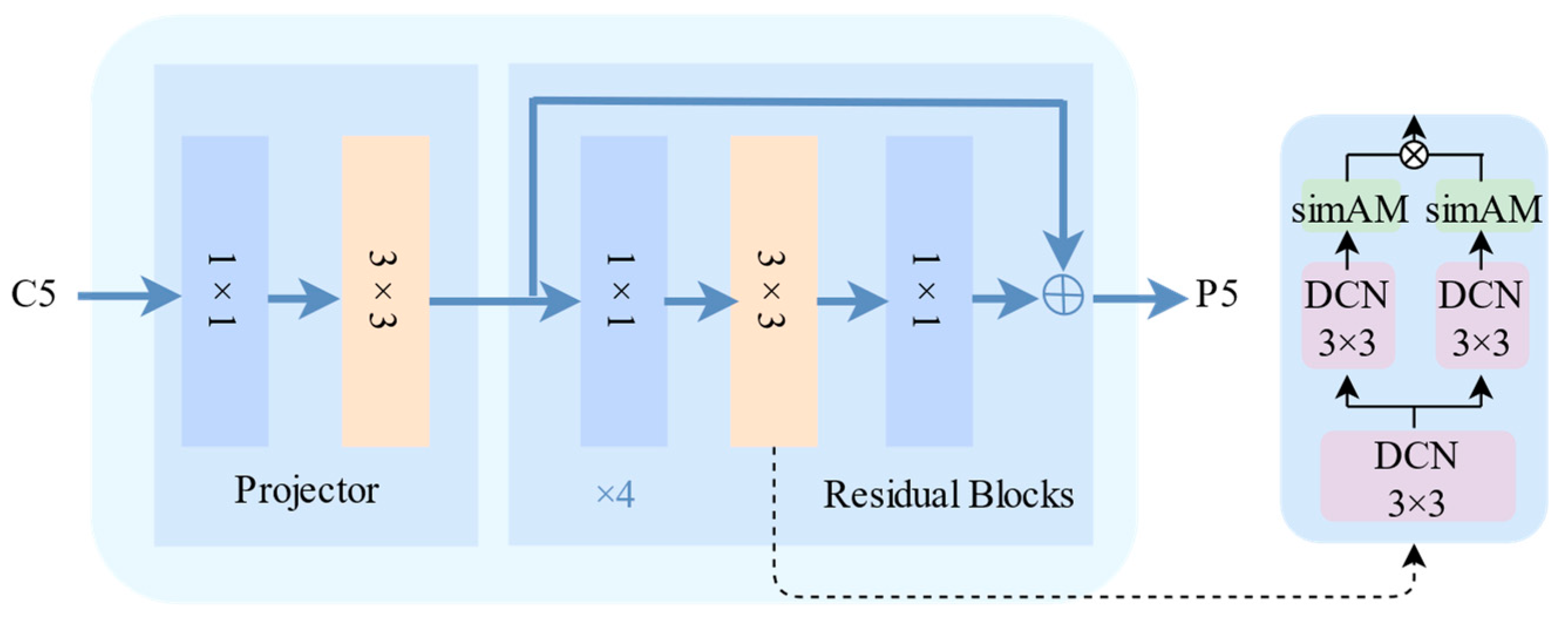

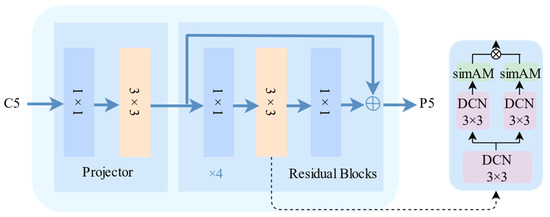

In this study, a module is proposed and designed based on deformable convolution and SimAM to enhance the performance of the YOLOF output encoder, which we named the DS module.

The architecture of the encoder consists of a projector and a residual block. The projection layer is stacked using two convolution layers: a 1 × 1 convolution for dimensionality reduction, followed by a 3 × 3 convolution for refining the semantic context to output a 512-channel feature map similar to that in a FPN. Four consecutively dilated residual blocks with different inflation rates are then stacked to achieve output features with multi-scale receptive fields to cover objects at different scales. In each residual block, a 1 × 1 convolution is used for channel reduction (with a reduction rate of 4), followed by a 3 × 3 expansion convolution to adjust the receptive field according to different dilation factors, and a final 1 × 1 convolution to recover the number of channels.

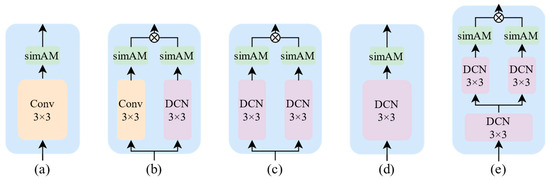

In this paper’s approach (shown in Figure 3), the traditional 3 × 3 dilated convolution is replaced by a combined module of deformable convolution and SimAM to capture scale variations more efficiently and enhance detection performance. The DS module leverages the deformable convolution’s ability to apply independent projection weights at each sampling point, enhancing the model’s adaptability and flexibility to diversified features, as well as its ability to adapt to different location and scale feature variations, thereby improving the network’s generalization ability.

Figure 3.

Diagrammatic representation of the dilated encoder structure. C5 is the input feature, and P5 is the output feature. The label 3 × 3 represents the dilated convolution, SimAM is the parameter-free attention, and DCN is the deformable convolution.

On the other hand, SimAM, as a parameter-free attention mechanism, can be learned without additional parameters, reducing model complexity and the risk of overfitting while being computationally concise and efficient. Through clever design, the DS module enhances the feature extraction capability of the backbone network, fully leveraging the advantages of deformable convolution and SimAM.

3.2. qOTA-Matching

The OTA (Optimal Transport Assignment) algorithm transforms the label assignment problem into a globally optimal transmission problem. However, one of the main drawbacks of the OTA [30] algorithm is its heavy reliance on the Sinkhorn–Knopp algorithm, which increases time consumption during the optimization process. The subsequent optimal transmission allocation (SimOTA) method simplifies the optimization process of OTA, addresses its defects, reduces training time, and offers a more efficient label assignment strategy for research in the field of object detection.

Inspired by erfOTA [31], this study proposes a label assignment strategy based on object quality optimization (qOTA). qOTA optimizes the sample selection strategy according to the principle of SimOTA, considering the area ratio of the prediction box to the ground truth box. It focuses on improving the quality of positive samples, especially when detecting small-scale objects, as for small objects, the quality of positive samples has a much greater impact on performance than quantity.

Generally, based on the prediction boxes predicted by the decoder, qOTA-matching will first analyze the number of positive samples corresponding to each ground truth, and then select consistent positive samples from the anchors. The process is divided into two main phases: positive sample identification and positive sample selection. The improvement in this paper is mainly in the phase of positive sample confirmation.

In the positive sample confirmation phase, a new parameter is defined, which represents the weight between the predicted box and the ground truth box. represents the Euclidean distance between the centers of the predicted box and the ground truth box, while indicates the perception range of the backbone k. When is bigger than , it equals 1; otherwise, it equals 0. is the ratio of the area of the predicted box to the truth box. When the predicted box is smaller than the actual box, represents the prediction box. represents the ground truth box when the predicted box is larger than the ground truth box. The opposite occurs when the predicted bounding box is larger than the ground truth box.

The label assignment based on the sample object quality (qOTA) strategy proposed in this study integrates the area ratios of predicted and ground truth boxes in the matching mechanism, which is the main difference from the erfOTA method. After the detector outputs the prediction box, for each real object, the qOTA strategy will select a set of closest prediction boxes as region proposals. represents the weight between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth box, and denotes the positive sample quality factor of the ground truth box. indicates rounding up. The process by which the qOTA strategy employs this meticulous matching method to ensure that each ground truth object is matched with a set of can be described as follows:

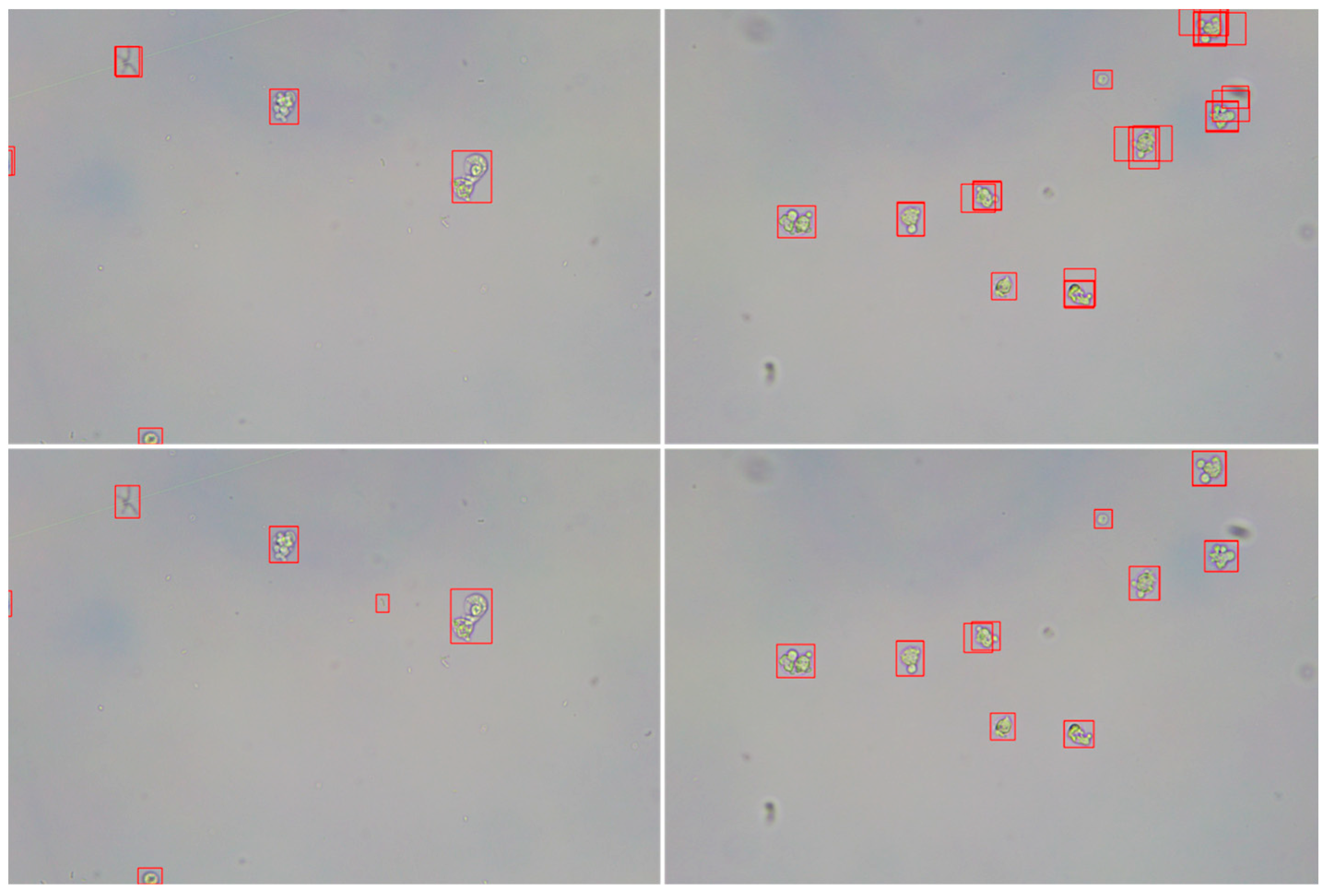

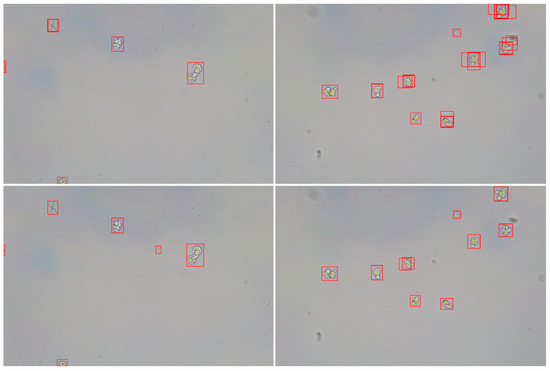

At this stage of positive sample selection, for each ground truth, the number of anchors is chosen as the positive sample. Finally, classification is performed using focal loss, and regression is performed using GIoU [32] (Generalized Intersection over Union). As shown in Figure 4, it can be observed that qOTA labels fewer boxes but is slightly more accurate and works better for small objects and objects with diverse shapes.

Figure 4.

The top is the box labeled for the original YOLOF sample selection and the bottom is the box labeled for the Dq-YOLOF sample selection.

3.3. Urinary Sediment Dataset

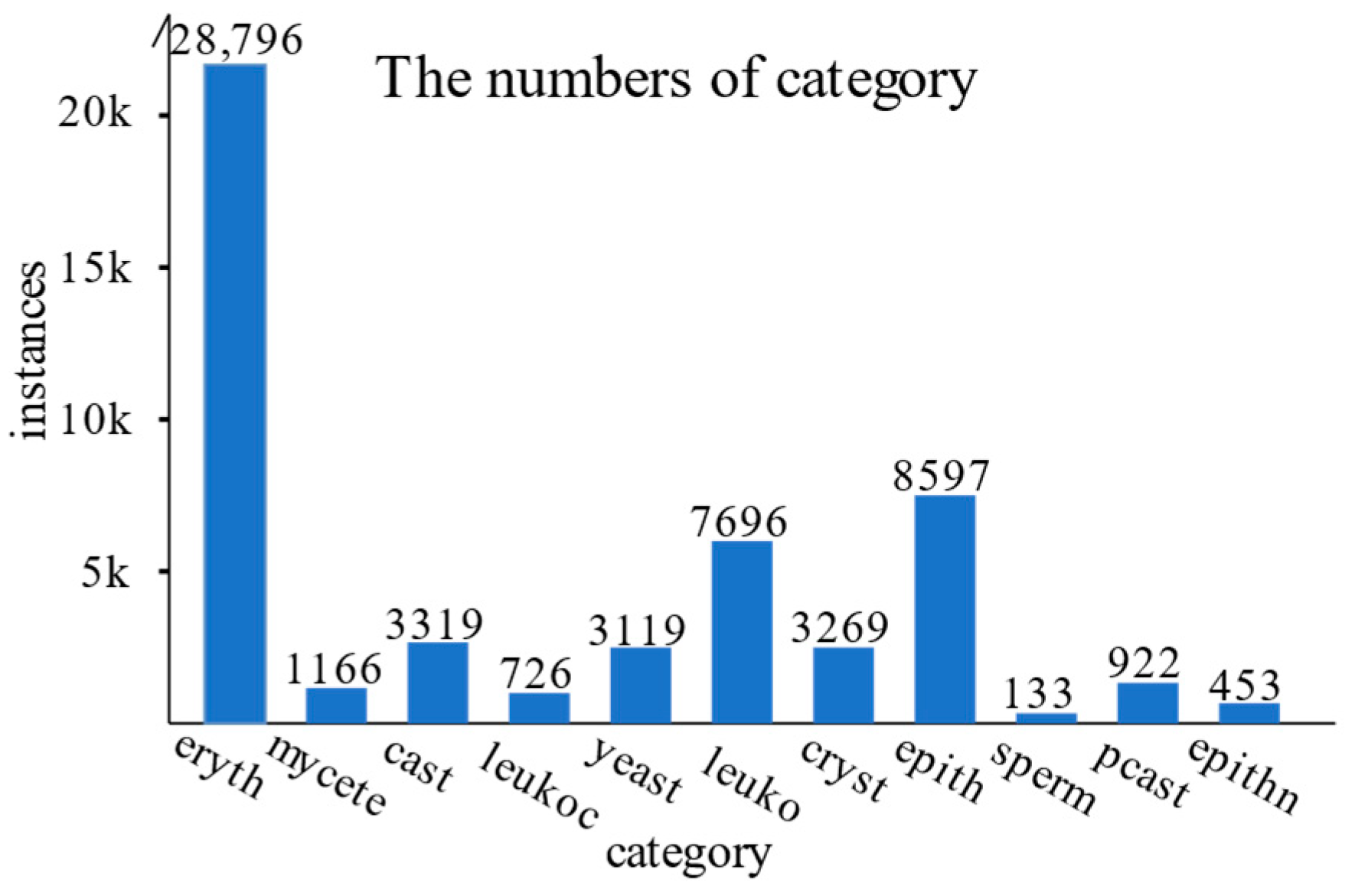

To validate the performance of Dq-YOLOF against morphologically diverse objects, we decided to test it on a urinary sediment dataset containing images from the Hefei Institute of Physical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences. We primarily screened the dataset and selected images with better annotation quality and clarity for retention. The dataset mainly includes 11 components: erythrocytes (Eryth), leukocytes (Leuko), leukocyte clusters (Leukoc), squamous epithelial cells (Epith), non-squamous epithelial cells (Epithn), clear tubular (Cast), pathological tubular (Pcast), spermatozoa (Sperm), yeasts (Yeast), molds (Mycete), and crystals (Cryst). Hence, it is named Urised11.

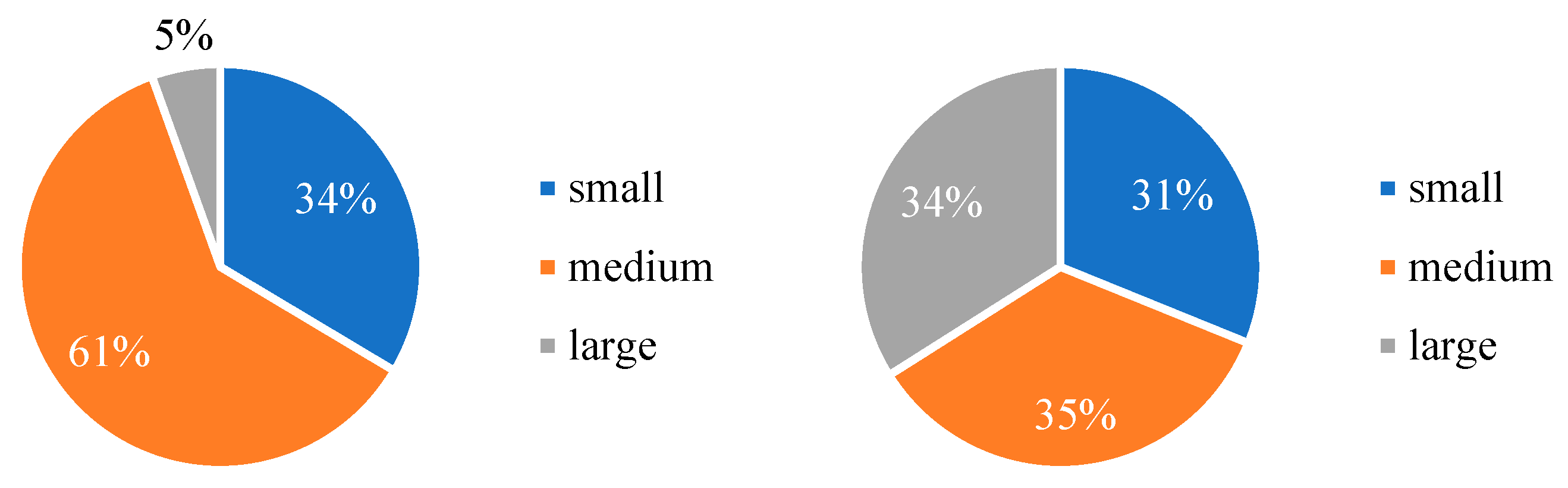

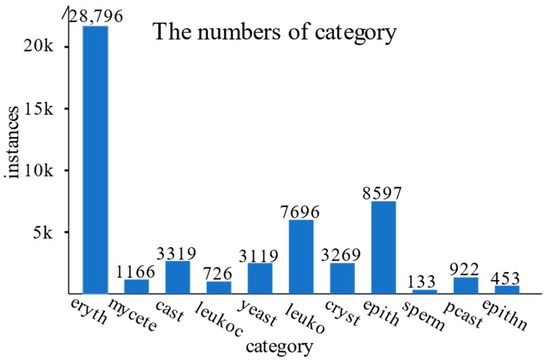

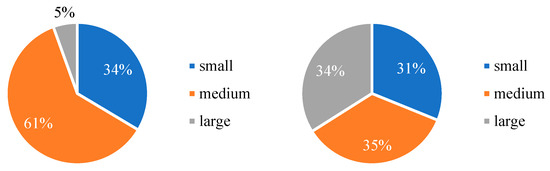

The Urised11 dataset contains 7364 urinary sediment images, all sized 720 × 576, with a total of 58,063 labels. The training and validation sets were divided in a 4:1 ratio. The training dataset contains 5891 images, while the test dataset has 1473 images. Figure 5 shows the number of labels in each category of the dataset, and Figure 6 illustrates the percentage of small, medium, and large objects. It is evident that the percentage of small and medium objects in the Urised11 dataset is significantly higher than that of large objects, with small objects comprising 34%. In contrast, the COCO2017 dataset has a near 1:1:1 ratio for small-, medium-, and large-object labels. Therefore, the Urised11 dataset is more suitable for validating Dq-YOLOF.

Figure 5.

Number of labels per each category in the dataset.

Figure 6.

Number of small, medium, and large objects in the Urised11 dataset and COCO2017 dataset: the left is the Urised11 dataset, and the right is the COCO2017 dataset.

The intraclass variation in the Urised11 dataset is also relatively large. This paper uses the Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS [33]) and the structural similarity (SSIM [34]) to evaluate the similarity of images within each class of urinary components. For LPIPS, we randomly selected 100 objects in the dataset for each class of urinary component and then used VGG [35] (Visual Geometry Group) to calculate the average similarity between them pairwise. SSIM also uses the same method, as shown in Table 1, which demonstrates some of the urinary sediment with large intraclass differences.

Table 1.

Examples of 11 different categories of cells.

A smaller LPIPS value means higher similarity, while for SSIM, a larger value indicates higher similarity. As shown in Table 1, which lists the LPIPS and SSIM values for the eleven classes of example images, the mean LPIPS value is 0.510, with seven of the classes below this mean. The lowest LPIPS is for erythrocytes, indicating that the morphology of erythrocytes is relatively similar. The mean SSIM value is 0.48, with six classes above this mean. The highest SSIM is for sperm, indicating that spermatozoa are more structurally uniform. The two values, LPIPS and SSIM, reflect a more similar intraclass variation. Morphologically, there is significant intraclass variation in each category, with different colors and morphologies, despite being the same cells. The most noticeable differences to the naked eye are in the tubular cells and yeast cells. According to the example images, the Urised11 dataset has a more homogeneous background for the images. The intraclass difference is mainly due to morphological changes in the objects, making it challenging to use the Urised11 dataset for detection.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Details and Environment

The experiments were conducted on a Dell T640 server equipped with a GeForce RTX 3090 GPU (24G RAM) using the software Ubuntu 20.04, CUDA 11.2, Python 3.9, and PyTorch 1.12.1. The main experiments in this paper were carried out using the detectron2 [36] platform, a deep learning object detection toolkit based on the PyTorch framework.

Gradient descent and updating were performed using SGD [37] (Stochastic Gradient Descent), and all models were trained with an initial learning rate of 0.12. The batch size was set to 16 and all models were trained for 100,000 iterations.

4.2. Assessment of Indicators

The evaluation metric of the experiment uses COCO evaluation standards. (average with IoU at [0.5:0.95]), ( with IoU = 0.50), ( with IoU = 0.75), ( for small objects), ( for medium objects), and ( for large objects) were used as evaluation metrics in this paper. is used to measure the size of the model, (Giga Floating-point Operations Per Second) describe the complexity of the algorithm, and (Frames Per Second) indicates how many images can be processed per second.

4.3. Comparison with Previous Detectors

This paper compares the Dq-YOLOF model with other state-of-the-art object detectors on the COCO2017 validation dataset. The different detectors, where possible, all use backbone networks of similar sizes and dimensions. The backbone network for Yolov3 uses Darknet53 with an input image size of 416 × 416. SSD and Faster R-CNN use a backbone network, ResNet101. RetinaNet, TridentNet, and FCOS all use ResNet50 as the backbone network. It can be seen that Dq-YOLOF exceeds the performance of many other methods.

Yolov5 is the more widely used model today, and its accuracy is better than Dq-YOLOF with a ResNet50 backbone, but lower than Dq-YOLOF with a ResNet101 backbone. TridentNet [38] was the first model to use single-input–multiple-output (SiMo) encoders, and in Table 2, the GFLOPs of TridentNet are smaller because it only uses the C4 layer output of the backbone network. However, the results show that the average accuracy is still lower than that of the method in this paper. FCOS outperforms Dq-YOLOF in terms of FPS and computation due to the use of the Multiple-In–Multiple-Out (MiMo) encoder and is only a little more accurate in terms of than Dq-YOLOF. Nevertheless, weighing the costs and benefits, this result is acceptable. Finally, we compare the YOLOF method, which is the basic detector used in this paper. Our method, Dq-YOLOF-R50, is 1.5 higher than YOLOF-R50. It is worth noting that for the difficult small-object detection task, Dq-YOLOF improves by 0.7 , while Dq-YOLOF using ResNet101 as the backbone reaches the highest for each . It can be seen that not only are the improved, but also the results are better for medium and large objects.

Table 2.

Comparison of results of different object detection methods on COCO2017 dataset.

4.4. Ablation Experiments

Since the Dq-YOLOF improvement involves two components, we need to verify their impact on performance. The baseline is a YOLOF detector with an input image size [1333, 800] and a backbone network of ResNet50.

4.4.1. Impact of Components

Table 3 presents the experimental results of our ablation study. Our baseline achieved an of 37.2, which is the lowest among the tested configurations. When the DS block was added, we observed an increase in to 37.9, representing a 0.7 improvement over the baseline detector. However, there was almost no improvement in the for small objects, with the main gains seen in large objects. While there were improvements in all precision metrics when the Transformer was utilized, they were relatively small, with the increasing by only 0.3 and even decreasing by 0.2 in some cases. When qOTA-matching was employed, the increased from 37.2 to 38.2, and the for small objects improved by 1.2. Finally, our method, which incorporates both the DS module and qQTA, results in Dq-YOLOF improving the by 1.5, with enhancements seen across all scales. This aligns with our initial vision for Dq-YOLOF, which is to enhance its ability to process features at various scales.

Table 3.

Ablation experiments on the COCO2017 dataset.

4.4.2. Impact of Transformer and CNN

To explore the CNN, the Transformer, and our method, we conducted experiments as shown in Table 4. From the table, it can be seen that when the Transformer is used, the is improved by 0.7 compared to YOLOF. When the CNN is used, the decreases by 0.3. However, when both methods are used, the improvement reaches 1.3, but the model becomes significantly more complex, resulting in poorer performance. Moreover, when both the Transformer and CNN are used simultaneously, training becomes very difficult, and the time consumed is much greater than that of Dq-YOLOF, and the AP will decrease by 0.2 points.

Table 4.

The impact of CNN and Transformer.

4.4.3. Impact of Topk

To verify the feasibility of our method, we experimented with some parameters. Firstly, a comparison test was conducted for region proposal, specifically the number of region proposals in qOTA-matching, which is used to calculate the number of positive samples corresponding to each ground truth. As shown in Table 5, when = 7, the is the highest, reaching 38.7. Considering all factors, we chose = 7 as the default number of region proposals. When topk is too large, it increases the complexity of the algorithm and leads to incorrect matches, making the results more susceptible to interference and thus reducing accuracy.

Table 5.

Impact of region proposals on results.

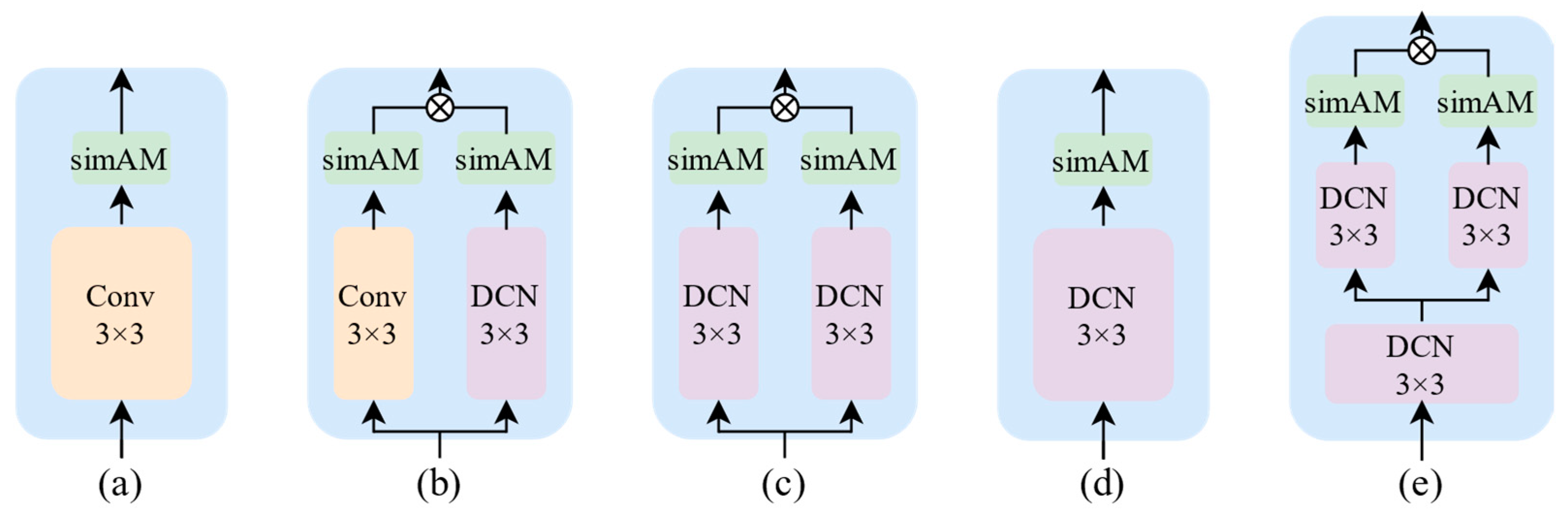

4.4.4. Effect of Different Structural Convolution Blocks

According to Table 6, we can see that the highest accuracy is achieved when using method e, and according to the table, we can see that the structures of b and c, and a and d are the same, but the accuracy of c is higher than that of b. The reason is that the sensory field of the dilated convolution will be affected by the dilation rate, which may lead to a certain degree of loss of information or blurring, and the feature learning will be limited, so the accuracy is not as high as when using the deformable convolution.

Table 6.

Accuracy of five different structures.

According to Table 7 and Figure 7, it can be seen that the number of parameters and complexity of a and b are greater than the other three structures because a and b use the dilated convolution, which introduces the dilation rate parameter to increase the number of parameters in the model, increasing model size. It introduces spacing on the inputs, which requires more computation to process, and higher computational clutter compared to deformable convolution. After comprehensive balancing, Dq-YOLOF uses structure e.

Table 7.

Costs consumed by five different methods.

Figure 7.

Five structures compared with the original method, where (a) is the original method, Conv stands for dilated convolution, DCN stands for deformable convolution, and simAM stands for parameter-free attention. (b) employs parallel dilated convolution and deformable convolution, followed by a simAM module in series after each convolution. (c) replaces the dilated convolution in (b) with deformable convolution. (d) replaces the dilated convolution in a with deformable convolution. (e) combines both (c,d).

4.4.5. Effects of Deformable Convolution Blocks

Method e combines c and d, so it is necessary to explore the impact of the number of serial deformable convolution blocks on the results. Thus, comparative experiments were conducted, as shown in Table 8. Finally, the number of serial deformable convolution blocks was chosen to be two.

Table 8.

The effect of stringing different numbers of deformable convolutional blocks in method e.

4.5. Comparisons on the Urised11 Dataset

To verify whether Dq-YOLOF can enhance the detection of objects with various shapes, we conducted experiments on the Urised11 dataset. As shown in Table 9, we found that only the accuracy decreased, while all other aspects showed improvements. Notably, the greatest improvement was observed in the detection of small objects. The experiment also tested the accuracy of each of the 11 categories in the dataset, as presented in Table 10. Among them, Leuko and Epith achieved the highest of 60.0, likely because they both have a relatively high number of labels and significant intracellular variability, making them easier to identify. The of Mycete, Sperm, and Epith increased significantly by 5.1, 4.6, and 4.0, respectively. This can be attributed to their higher SSIMS, greater intraclass similarity, and more dispersed distribution, which make them easier to detect and thus result in higher improvements during Dq-YOLOF training. The growth of Eryth and Epithn was smaller, with increases of only 0.8 and 0.2, respectively. This is because these two categories have larger intraclass differences, significant variations in cell color, and the cells tend to cluster together, leading to missed or mis-detected instances. Leuko, Cryst, Cast, and Pcast all showed improvements, but the improvements were not significant. This is because these categories exhibit partial cell adhesion or aggregation, resulting in moderate improvements. Leukoc, however, did not show any improvement due to its small number of labels, high intraclass variability, and blurred background. Overall, our method demonstrates good improvements in detecting small-scale objects and detecting in complex environments. However, there are still some instances of missed or mis-detected objects, and with a smaller training dataset, it becomes difficult to achieve further improvements.

Table 9.

Comparison of accuracy on the Urised11 dataset.

Table 10.

Comparison of accuracy for each category on a given urinary sediment dataset.

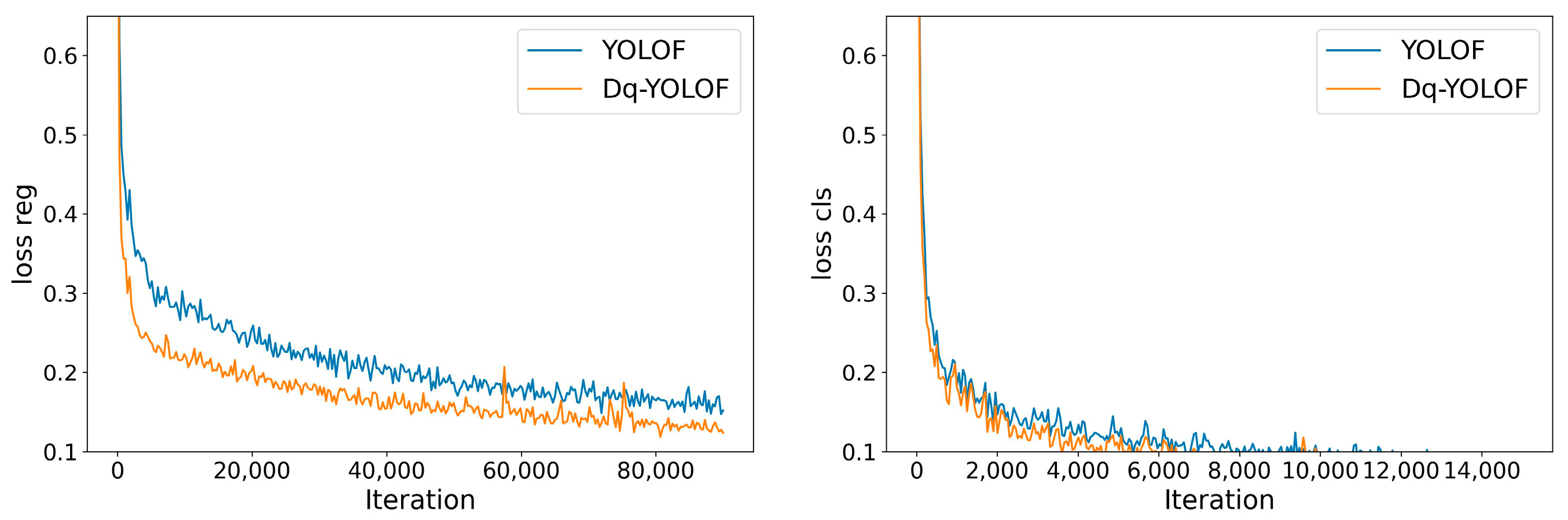

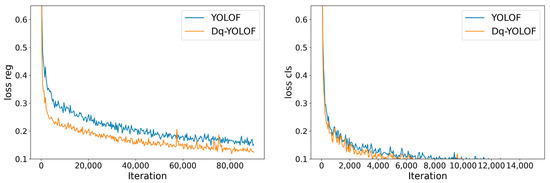

Loss Analysis

We plotted loss curves to analyze the training process. As shown in Figure 8, the regression loss of this paper’s method is much lower than that of YOLOF when the input images are the same, and the classification loss of Dq-YOLOF decreases faster at the beginning, which may mean that it learns faster at this stage. The main reason for this is that the urinary sediment data are mainly small and medium objects and only a few are large objects. Since the classification loss reaches a better result at 20,000 iterations, a line graph of the data between 0 and 20,000 is shown. It can be seen that both the classification loss of Dq-YOLOF and the classification loss of YOLOF converge to very small values in the end, but Dq-YOLOF is a little faster. This indicates that the model converges faster and is more accurate. Based on these curves, we can conclude that the Dq-YOLOF model shows faster learning speed in training both in classification and regression tasks, which indicates that it is more efficient compared to YOLOF.

Figure 8.

Loss curves for YOLOF and Dq-YOLOF. The left is the regression loss and the right is the classification loss.

4.6. Comparisons on the VisDrone Dataset

To verify the generalization capability of our research method, we conducted validation experiments on the VisDrone2019 [39] dataset. The VisDrone2019 dataset is an open-source dataset for object detection and tracking in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) surveillance videos. It consists of 10,209 images, including 6471 images for training, 3190 images for testing, and 548 images for validation. It covers various traffic objects and pedestrians in daily life scenarios, with a primary focus on small-object detection, making it suitable for object detection research in complex environments. Therefore, this dataset can effectively validate the effectiveness of our method.

According to Table 11, our method improves the average precision () by 1.9 compared to the original method. The of YOLOF is lower than that of TridentNet, ATSS, and Faster RCNN. However, our method’s is higher than those, although our precision on is the same as ATSS.

Table 11.

Comparison of precision on the VisDrone2019 dataset.

5. Conclusions

To address the issues of insufficient accuracy and poor coverage capability for multi-scale targets in single-stage detectors, this study has improved the YOLOF by focusing on the output encoder and label assignment strategy. In terms of encoder design, a novel deformable convolution module has been adopted to replace the traditional dilated convolution, effectively accommodating the scale and morphological variations of the detected targets. Additionally, based on the principles of SimOTA, the sample selection strategy has been optimized to emphasize the quality of positive samples over the quantity. This is particularly crucial when detecting small-scale targets, as the quality of positive samples has a significantly greater impact on detection performance than their quantity for such targets.

Initially, comparative experiments were conducted on the COCO2017 dataset with YOLOF and other models, verifying the effectiveness of the improved Dq-YOLOF. Furthermore, experiments were carried out on the Urised11 dataset, and the results indicated a significant improvement in accuracy for targets with complex shapes and multi-scale characteristics using Dq-YOLOF. Lastly, the VisDrone2019 dataset was utilized to validate the generalization capability of Dq-YOLOF. Ultimately, it was demonstrated that Dq-YOLOF is a valuable and effective method for addressing challenging scenarios in object detection. However, we also found that for targets with a small number of labels and significant intraclass variations, the improvement in accuracy with Dq-YOLOF was not pronounced. In future research, we plan to further optimize the regression loss function and explore more efficient encoder structures.

Author Contributions

X.Q. provided the theoretical foundation for the research, identified the main innovative points of the paper, determined the paper’s content, and assisted in resolving encountered difficulties. L.C. organized the dataset, constructed the preliminary theoretical framework, and conducted partial experiments. M.G.M.J. was responsible for methodological guidance. A.K. and J.T. were responsible for supervision and oversight. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Anhui Province Quality Engineering Project (No. 2014zytz035, No. 2015xnzx024, No. 2016mooc188, No. 2023ylyjh059) and Anhui Province Training Project for Academic Leaders in Disciplines (No. DTR2024056).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, A.; Magnani, A.; Maio, D. A multimodal approach for human activity recognition based on skeleton and RGB data. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 131, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendorfer, P. Mot20: A benchmark for multi-object tracking in crowded scenes. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.09003. [Google Scholar]

- Leibe, B.; Matas, J.; Sebe, N.; Welling, M. (Eds.) Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Farhadi, A.; Redmon, J. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. In Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. FCOS: Fully convolutional one-stage object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9627–9636. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Chen, Q.; Xu, J.; Koltun, V. Seeing motion in the dark. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 13039–13048. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Chen, P.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, D.; Huang, Z.; Hou, X.; Cottrell, G. Understanding convolution for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 1451–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Qi, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y. Deformable Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 764–773. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Li, K.; Luo, X.; Xu, X.; He, S.; Zhang, K. Fully Deformable Network for Multiview Face Image Synthesis. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 8854–8868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Dai, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Hu, X.; Lu, T.; Lu, L.; Li, H.; et al. InternImage: Exploring Large-Scale Vision Foundation Models With Deformable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 14408–14419. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L. Attention is all you need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Woo, S.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Bam: Bottleneck Attention Module. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06514. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, R.-Y.; Li, L.; Xie, X. SimAM: A simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR), Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 11863–11874. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Chi, C.; Yao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Li, S.Z. Bridging the gap between anchor-based and anchor-free detection via adaptive training sample selection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 9759–9768. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Chen, F.; Shen, Z.; Savvides, M. Soft anchor-point object detection. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020, Proceedings, Part IX 16; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Wang, X.; Lv, W.; Chang, Q.; Cui, C.; Deng, K.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Wei, S.; Du, Y.; et al. PP-YOLOE: An evolved version of YOLO. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.16250. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 7263–7271. [Google Scholar]

- Long, X.; Deng, K.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Dang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Shen, H.; Ren, J.; Han, S.; Ding, E.; et al. PP-YOLO: An effective and efficient implementation of object detector. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.12099. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Lv, W.; Bai, X.; Long, X.; Deng, K.; Dang, Q.; Han, S.; Liu, Q.; Hu, X.; et al. PP-YOLOv2: A practical object detector. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.10419. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. Yolox: Exceeding yolo series in 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.08430. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yoshie, O.; Sun, J. Optimal transport assignment for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Qian, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, C.; Ye, X.; Wang, H. M2YOLOF: Based on effective receptive fields and multiple-in-single-out encoder for object detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 118928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Zhu, T.; Kaskman, R.; Motlagh, F.T.; Shi, J.Q.; Milan, A.; Cremers, D.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Reid, I. Learn to predict sets using feed-forward neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Deep Features as a Perceptual Metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Kirillov, A.; Massa, F.; Lo, W.-Y.; Girshick, R. Detectron2. 2019. Available online: https://www.github.com/facebookresearch/detectron2 (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Stich, S.U.; Cordonnier, J.B.; Jaggi, M. Sparsified SGD with memory. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Z. Scale-Aware Trident Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6054–6063. [Google Scholar]

- Du, D.; Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Lin, H.; Hu, Q.; Peng, T.; Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. VisDrone-DET2019: The vision meets drone object detection in image challenge results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).