Abstract

Generative text summaries often suffer from factual inconsistencies, where the summary deviates from the original text. This significantly reduces their usefulness. To address this issue, we propose a novel method for improving the factual accuracy of Chinese summaries by leveraging dependency graphs. Our approach involves analyzing the input text to build a dependency graph. This graph, along with the original text, is then processed by separate models: a Relational Graph Attention Neural Network for the dependency graph and a Transformer model for the text itself. Finally, a Transformer decoder generates the summary. We evaluate the factual consistency of the generated summaries using various methods. Experiments demonstrate that our approach improves about 7.79 points compared to the baseline Transformer model on the Chinese LCSTS dataset using ROUGE-1 metric, and 4.48 points in the factual consistency assessment model StructBERT.

1. Introduction

Generative text summarization aims to create short, concise, and easy-to-read summaries by extracting key information from a text. This approach offers greater flexibility than extractive summarization, allowing models to generate new words with some probability. This capability brings summaries closer to those manually created, leading to a surge in research on generative models [1,2,3].

However, despite significant advancements achieved through neural networks, a critical challenge remains. Maynez et al. [4] demonstrated that sequence-to-sequence generative models often introduce “hallucinatory contents”—factual errors not present in the original text. Research by Falke et al. [5] further highlights this problem, finding that 25% of summaries from state-of-the-art models contain factual errors. Table 1 showcases examples of these errors in three classical models [5]. As shown, the PGC model replaces the protagonist Jim Jeps with the unrelated Green Party leader Natalie Bainter, the FAS model transforms a viewpoint based on assumptions into definitive statements, and the BUS model incorrectly changes the protagonist of the document from a defender to a club. This issue plagues Chinese text summarization as well, significantly hindering the credibility and usability of generative text summarization models.

Table 1.

Demonstration of erroneous sentences produced by different summarization models on the CNN-DM test set.

This paper proposes the Dependency-Augmented Summarization Model (DASUM) to address the issue of hallucination in Chinese text summarization, where summaries contain factual inconsistencies. DASUM leverages jieba (https://github.com/fxsjy/jieba, accessed on 30 June 2024) for initial segmentation of the source document. It then employs Baidu’s DDParser [8] to analyze the dependency relationships between the resulting tokens. Dependency analysis is crucial for capturing the relationships between words in Chinese text. This analysis results in a dependency graph where each edge represents a relationship between two words (head and dependent). DASUM then employs the Relational Graph Attention Network (RGAT) [9] within its encoder to encode the dependency graph extracted from source document to obtain a representation for each node in the graph. This representation captures both the node’s information and its connection to other words. This, in turn, helps the model capture the relationships between important words in the sentence, thereby reducing potential distortions during summarization. The node representations are then integrated into a standard Transformer-based [10] encoder–decoder architecture. During decoding, the decoder attends to each graph node within each Transformer block, allowing it to focus on relevant information throughout the summarization process. This approach improves the model’s understanding of factual relationships within the source text, leading to summaries with improved factual accuracy.

Experiments conducted on the benchmark LCSTS dataset [11] demonstrate that DASUM effectively improves both the quality and factual correctness of generated summaries. Evaluated using ROUGE [12] metrics, DASUM outperformed the baseline Transformer model, achieving a substantial 7.79-point increase in the ROUGE-1 score and an 8.73-point improvement in the ROUGE-L score on the LCSTS dataset. Additionally, StructBERT [13] evaluation revealed a notable 4.48-point improvement in factual correctness for DASUM-generated summaries compared to the baseline. Finally, these quantitative results are corroborated by human evaluation, confirming the model’s effectiveness.

In summary, the contribution of this paper is threefold:

- The Dependency-Augmented Summarization Model (DASUM) is proposed to tackle the hallucination problem in Chinese text summarization.

- A dependency graph is constructed based on the dependency relationships in the source document to extract the relationships between keywords in the article.

- The Relational Graph Attention Network (RGAT) is employed to encode the dependency graph, thereby integrating factual information from the source document into the summary generation model.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Related works are reviewed in Section 2. Section 3 briefly introduces the system model. Furthermore, our experimental and evaluation results are provided and analyzed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential future directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Generative Text Summaries

Generative text summarization has been extensively studied in recent years, and most generative summarization models use an encoder–decoder architecture (seq2seq) [14]. In this architecture, the source text is processed by an encoder to generate representations, which are then passed to a decoder that outputs the summary word by word. Researchers have proposed various techniques to improve upon this foundation. For example, see [1]; moreover, Gu [15] introduced the copy–generate mechanism, allowing the model to both generate new words and directly copy words from the source document. Gehrmann et al. [7] employed a masking technique to control which phrases from the source document that the model should include in the summary. Additionally, Paulus et al. [2] utilized a reinforcement learning approach to improve the quality of summarization. Dong et al. [3] introduced UNILM, a pre-trained model capable of handling both natural language understanding and generative tasks, which achieves state-of-the-art results in various tasks including generative summarization.

2.2. Fact-Aware Text Summaries

Recent years have seen a surge in research studies targeting the hallucination problem in generative text summarization models. A popular strategy focuses on architectural improvements to the widely used encoder–decoder models. Researchers have explored modifications to the encoder, decoder, and encoder–decoder structure to reduce this issue.

Among the encoder enhancement approaches, Zhu et al. [16] proposed using graph neural networks to encode factual relations extracted from source documents. Huang et al. [17] developed a reinforcement learning reward mechanism based on multiple-choice fill-in-the-blank questions to encourage the model to better understand the interactions between entities. In addition, Gunel et al. [18] used external knowledge from Wikipedia for knowledge embedding, which was shown to be useful in alleviating the hallucination problem.

In the decoder improvement approaches, Song et al. [19] proposed combining a sequential decoder with a tree-based decoder to generate text summaries. Aralikatte et al. [20] introduced the focal attention mechanism, which encourages the decoder to generate summaries that are similar or semantically related to the source document.

In approaches on encoder–decoder enhancements, Cao [21] extracted factual descriptions from the source text and applied a dual-attention framework to ensure summaries align with both source and the extracted factual information. Li [22] proposed an implication-aware architecture with multi-task learning that incorporates implication knowledge into the abstract summarization model.

Several research efforts have explored alternative training methods to mitigate the hallucination problem. Cao and Wang et al. [23] introduced a contrast learning method for training summarization models. This method utilizes positive training data consisting of reference summaries and negative data containing automatically generated hallucinations. A contrast learning system then distinguishes between these two types of summaries. Similarly, Tang et al. [24] proposed CONFIT, a contrast fine-tuning strategy that improves factual consistency and overall summary quality.

Some research works focus on post-editing techniques. Dong et al. [25] proposed SpanFact, a fact-correction model that leverages knowledge learned from QA models to rectify errors in summaries. Similarly, Cao [26] introduced a post-editing correction module to identify and correct hallucinatory content in generated summaries The correction module was trained on synthesizing data that were created by applying a series of heuristic transformations to reference summaries. Another research by Chen [27] introduced a contrast candidate generation and selection system for post-processing. This system first replaces named entities in the generated summaries with those from the source document, and then the system selects the best candidate as the final output summary.

3. System Models

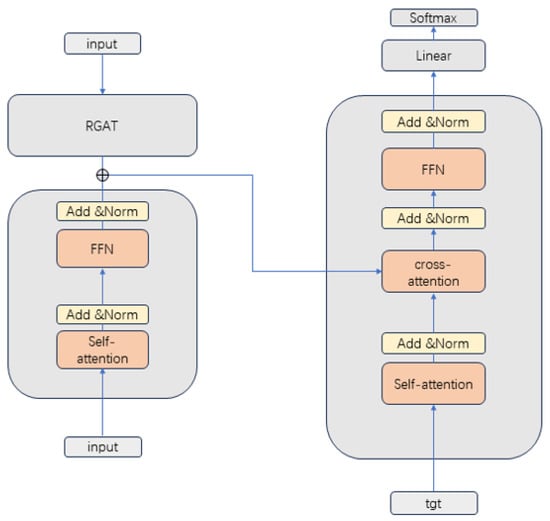

Our model employs a Transformer-based architecture without pre-training. To leverage dependency relationships within the source document, we incorporate a Relational Graph Attention Network (R-GAT) [9] on top of the Transformer. Sentence embeddings are initially generated by the sentence encoder. Subsequently, R-GAT produces node embeddings for the dependency graph, capturing inter-word relationships. During decoding, the model attends to both sentence and node embeddings, enabling the generation of informative and factually accurate summaries. The model architecture is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

DASUM model architecture.

3.1. Problem Formulation

Given a tokenized input sentence , where n is the number of tokens, and a corresponding summary with , we conduct dependency analysis to construct a dependency graph . In this graph, V represents the set of nodes, E represents the set of edges, and each edge is defined as , where , , and . denotes the set of dependency labels. Our objective is to generate the target summary Y given input sentence X and its dependency graph G. While the Transformer’s time complexity is , R-GAT’s complexity is for a graph with V vertices, E edges, and feature dimension F. Despite this, parallel training maintains an overall complexity. Our proposed method offers enhanced expressive power compared to a baseline Transformer model. Algorithm 1 shows the training process of DASUM.

| Algorithm 1 Training Process of the Dependency-Augmented Summarization Model |

|

3.2. Graph Encoder

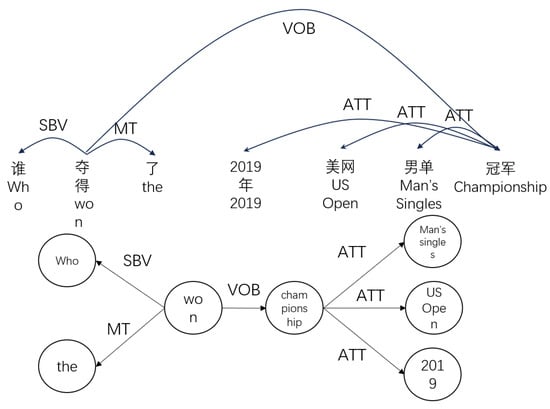

We employed DDParser, a Chinese dependency analysis tool built on the PaddlePaddle platform, to extract dependencies between words. Directed graphs were then constructed from these dependencies (as shown in Figure 2). Subsequently, we obtained node representations using the Relational Graph Attention Neural Network (R-GAT).

Figure 2.

Words and word dependency graphs.

R-GAT extends the Graph Attention Network (GAT) to incorporate edge labels. In this paper, a dependency tree is modeled as a graph G with n nodes representing words, and edges denoting dependency relations. GAT iteratively updates node representations by aggregating information from neighboring nodes using a multi-head attention mechanism:

where is the attention head of node i at layer , and denotes the concatenation of vectors from to . represents the normalized attention coefficient computed by the attention head at layer l, and is the input transformation matrix. This paper employs dot-product attention for .

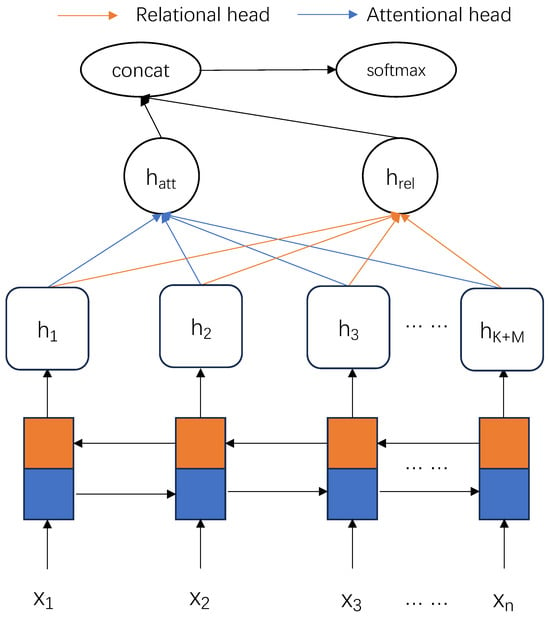

While GAT aggregates information from neighboring nodes, it overlooks dependency relationships, potentially missing crucial information. To solve this problem, we introduce R-GAT, which has relation-specific attention heads, allowing for differentiated information flow based on dependency types. Intuitively, nodes connected by different dependency relations should have varying influences. By capturing and leveraging these fine-grained dependency details, our model excels at comprehending and representing sentence structure. This improved understanding benefits subsequent natural language processing tasks. The overall architecture is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

R-GAT architecture diagram.

Specifically, we first map the dependencies to vector representations and then compute the relation header as

where denotes the relational embedding between node i and node j. R-GAT contains K attention heads and M relational heads. The final representation of each node is computed by

3.3. Sentence Encoder

The sentence encoder processes the input sentence to generate contextual representations, mirroring the standard Transformer architecture. It comprises multiple layers, each consisting of multi-head attention followed by Add & Norm, and a feed-forward layer followed by another Add & Norm layer. To account for word order, essential for language understanding, positional encoding (PE) is incorporated. PE vectors, identical in dimension to word embeddings, are added to the word embeddings. These PE vectors are computed using a predetermined formula:

where denotes the position of the word in the sentence and denotes the dimension of the PE.

In the multi-head self-attention mechanism, attention scores are computed from query (Q), key (K), and value (V) matrices. To mitigate the impact of large inner products between Q and K, the result is scaled by the square root of the key dimension (). Subsequently, a softmax function is applied to obtain attention weights, which are then used to compute a weighted sum of the values:

Following the multi-head attention mechanism, a feed-forward network is applied. Both components are wrapped in residual connections and Layer Normalization (Add & Norm). The encoder processes the input matrix X through multiple layers of this structure, generating the following output representation:

A single encoder processes the input matrix and outputs a matrix O of identical dimensions. To enhance representation learning, multiple encoder layers can be stacked sequentially. The output of each layer becomes the input to the subsequent one, with the final output derived from the last encoder.

3.4. Decoder

The decoder combines the outputs of the sentence encoder and graph encoder into a unified representation:

Specifically, the decoder employs two multi-head attention layers. The first layer utilizes masked self-attention to prevent the model from attending to future tokens during training, akin to the standard Transformer. The second layer’s K and V matrices are computed from a concatenation of the sentence encoder’s and graph encoder’s outputs, while the Q matrix is derived from the previous decoder layer’s output. This allows the decoder to access information from both the sentence and dependency graph for each generated token. Finally, a softmax layer predicts the next word based on the decoder’s output.

4. Experimentation and Evaluation

This paper compares our proposed model, DASUM, to a baseline Transformer and a GAT+Transformer model to evaluate the effectiveness of the R-GAT module. While R-GAT and GAT models excel at modeling graph-structured data, they are rarely applied to natural language generation tasks. Therefore, in this study, we did not conduct separate comparative experiments on text summarization using R-GAT or GAT. Additional text summarization models will be incorporated for a comprehensive evaluation.

4.1. Datasets

We train and evaluate our model on the LCSTS [11] dataset, a benchmark for Chinese text summarization. Characterized by short text length and noise, LCSTS comprises three main parts. The first part of LCSTS, which contains 2,400,591 summary-text pairs across domains such as politics, athletics, military, movies, games, etc., offering diverse summarization topics and styles, is used as the training set of this paper. The second part of 10,666 manually annotated pairs including scores ranging from 1 to 5, indicating the correlation between the texts and the corresponding summary, is used as the validation set.

The third and final part of the dataset is a test set comprising 1106 samples. This set was manually curated based on the relevance between short texts and abstracts. To ensure data quality, duplicates, obvious mismatches, and other inconsistencies were removed, resulting in a final test set of 1012 samples. Table 2 presents the names and sizes of the three subsets within the LCSTS dataset.

Table 2.

LCSTS dataset details.

4.2. Model Hyperparameters

Our model leverages the Transformer architecture as its foundation, integrating an R-GAT network for enhanced performance (the complete source code for the experiment described in this paper can be found on the following website: https://gitee.com/liyandewangzhan/dasum, accessed on 20 July 2024). Based on previous findings [28,29] which suggest that smaller dimensions are effective for low-resource tasks like short-text summarization, we set the word embedding and hidden layer dimensions for both the sentence encoder and decoder to 512. Additionally, we limit the maximum sentence length to 512 tokens. To efficiently capture inter-sentence relationships, we adopt a 6-layer, 8-head multi-head attention mechanism as our base model. Future experiments will explore larger-scale attention mechanisms. To ensure consistency with the Transformer module, we employ the same hyperparameter configuration for the R-GAT network. This includes a 6-layer, 8-head self-attention mechanism with a word embedding dimension and hidden state size of 512. To promote the model’s generalization ability, we introduce a dropout rate of 0.1. We utilize the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1e-3 and momentum parameters of (0.9, 0.98). These hyperparameter configurations improve our model’s effectiveness in processing text tasks, leading to enhanced performance and efficiency.

4.3. Assessment Criteria

To evaluate the quality of generated summaries, we employed the standard ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L metrics. These metrics correlate well with human judgments and assess the accuracy of words, bi-gram matching, and longest common subsequences, respectively. Table 3 presents the ROUGE scores for all experiments.

Table 3.

Rouge scores for models on the LCSTS test set.

Experimental results demonstrate that the Transformer baseline significantly outperformed the RNN model, achieving 12.92, 11.54, and 11.59 points higher F1 scores on ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L, respectively, demonstrating the Transformer’s superiority. Our model further improved upon this foundation, surpassing the Transformer by 7.79, 4.70, and 8.73 points on ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L F1 scores, respectively. These findings underscore the effectiveness of the DASUM model.

Additionally, we evaluated the three models (DASUM, GAT+Transformer and Transformer) on the NLPCC test dataset (NLPCC 2017 Shared Task Test Data (Task 3), available at: http://tcci.ccf.org.cn/conference/2017/taskdata.php, accessed on 20 July 2024), which contains significantly longer text compared to the LCSTS dataset. Due to resource limitations, we directly tested the models trained on LCSTS without retraining them on NLPCC. As shown in Table 4, model performance on NLPCC is notably lower than on LCSTS. This is primarily attributed to the discrepancy in data distribution, with NLPCC predominantly featuring longer texts. Nevertheless, the DASUM model consistently outperforms both the GAT+Transformer and Transformer models on the NLPCC dataset.

Table 4.

Rouge scores for models on the NLPCC test set.

Meanwhile, we employed the StructBERT Chinese natural language inference model and ChatGPT-3.5-turbo large language model to evaluate factual correctness of summary texts. StructBERT, trained on CMNLI and OCNLI datasets, determines the semantic relationship between the source document and the generated summary. Using the dialogue template presented in Table 5, we instructed the ChatGPT-3.5-turbo model to provide a factual correctness score between 0 and 5 for each generated summary. By averaging these scores across all summaries in the test set via the ChatGPT API, we determined the model’s overall factual correctness.

Table 5.

ChatGPT dialogue template.

A comparative analysis of DASUM, the baseline Transformer, and GAT+Transformer across these evaluation metrics (presented in Table 6) demonstrates the superior factual correctness of our proposed model. Furthermore, manual evaluations of randomly selected samples support these findings.

Table 6.

Results of the factual consistency assessment.

4.4. Manual Assessment

To further assess our model’s ability to enhance semantic relevance and mitigate content bias, we conducted a manual evaluation focusing on fidelity, informativeness, and fluency. Representative examples are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Examples of manual assessments.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper explores the utilization of dependency graphs to enhance Chinese text summarization models. We introduce DASUM, a novel model that effectively integrates original text with dependency information to guide summary generation. Experimental results on the LCSTS dataset demonstrate the model’s effectiveness in improving semantic relevance and overall summary quality. While dependency relations offer valuable insights, challenges such as parsing errors in complex sentences and limited handling of cross-sentence dependencies persist. Future work will attempt to address the aforementioned issues, including the following:

- Incorporating multiple dependency parsers to mitigate the impact of errors from individual parsers;

- Enhancing dependency graph construction by considering the unique syntactic patterns and idiomatic expressions of the Chinese language;

- Leveraging human-in-the-loop reinforcement learning to iteratively refine summary generation quality.

Furthermore, we aim to develop more comprehensive evaluation metrics to assess summary quality from multiple perspectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.; methodology, R.C. and Y.J.; software, Y.L., B.S. and J.W.; validation, R.C., Y.L. and Z.L.; formal analysis, R.C. and Y.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, R.C. and Z.L.; visualization, Y.L.; project administration, R.C. and Y.J.; funding acquisition, R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was jointly supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (grant number L233008) and Promoting the Diversified Development of Universities—College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program, Beijing Information Science and Technology University, Computer School (grant number 5112410852).

Data Availability Statement

The LCSTS dataset used in this paper is available upon application from the following website: http://icrc.hitsz.edu.cn/Article/show/139.html. The NLPCC 2017 Shared Task Test Data (Task 3) is available from the following website: http://tcci.ccf.org.cn/conference/2017/taskdata.php.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- See, A.; Liu, P.J.; Manning, C.D. Get To The Point: Summarization with Pointer-Generator Networks. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 1073–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, R.; Xiong, C.; Socher, R. A Deep Reinforced Model for Abstractive Summarization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Yang, N.; Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, M.; Hon, H.W. Unified language model pre-training for natural language understanding and generation. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maynez, J.; Narayan, S.; Bohnet, B.; McDonald, R. On Faithfulness and Factuality in Abstractive Summarization. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 1906–1919. [Google Scholar]

- Falke, T.; Ribeiro, L.F.R.; Utama, P.A.; Dagan, I.; Gurevych, I. Ranking Generated Summaries by Correctness: An Interesting but Challenging Application for Natural Language Inference. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 2214–2220. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.C.; Bansal, M. Fast Abstractive Summarization with Reinforce-Selected Sentence Rewriting. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 675–686. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann, S.; Deng, Y.; Rush, A. Bottom-Up Abstractive Summarization. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October– 4 November 2018; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 4098–4109. [Google Scholar]

- Dozat, T.; Manning, C.D. Deep Biaffine Attention for Neural Dependency Parsing. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2017, Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Shen, W.; Yang, Y.; Quan, X.; Wang, R. Relational Graph Attention Network for Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; Jurafsky, D., Chai, J., Schluter, N., Tetreault, J., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 3229–3238. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, F. LCSTS: A Large Scale Chinese Short Text Summarization Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–21 September 2015; Màrquez, L., Callison-Burch, C., Su, J., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 1967–1972.12. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.Y. ROUGE: A Package for Automatic Evaluation of Summaries. In Proceedings of the Text Summarization Branches Out, Barcelona, Spain, 25–26 July 2004; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Bi, B.; Yan, M.; Wu, C.; Xia, J.; Bao, Z.; Peng, L.; Si, L. StructBERT: Incorporating Language Structures into Pre-training for Deep Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Online, 26 April–1 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q.V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. In NIPS’14: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 3104–3112. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Lu, Z.; Li, H.; Li, V.O. Incorporating Copying Mechanism in Sequence-to-Sequence Learning. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; Erk, K., Smith, N.A., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 1631–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Hinthorn, W.; Xu, R.; Zeng, Q.; Zeng, M.; Huang, X.; Jiang, M. Enhancing Factual Consistency of Abstractive Summarization. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online, 6–11 June 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 718–733. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, L. Knowledge Graph-Augmented Abstractive Summarization with Semantic-Driven Cloze Reward. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 5094–5107. [Google Scholar]

- Gunel, B.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M.; Huang, X. Mind The Facts: Knowledge-Boosted Coherent Abstractive Text Summarization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.15435. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.; Lebanoff, L.; Guo, Q.; Qiu, X.; Xue, X.; Li, C.; Yu, D.; Liu, F. Joint Parsing and Generation for Abstractive Summarization. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 8894–8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aralikatte, R.; Narayan, S.; Maynez, J.; Rothe, S.; McDonald, R. Focus Attention: Promoting Faithfulness and Diversity in Summarization. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), Virtual Event, 1–6 August 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 6078–6095. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Wei, F.; Li, W.; Li, S. Faithful to the Original: Fact Aware Neural Abstractive Summarization. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirtieth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Eighth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zong, C. Ensure the Correctness of the Summary: Incorporate Entailment Knowledge into Abstractive Sentence Summarization. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–26 August 2018; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 1430–1441. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Wang, L. CLIFF: Contrastive Learning for Improving Faithfulness and Factuality in Abstractive Summarization. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Virtual Event, 7–11 November 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 6633–6649. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Nair, A.; Wang, B.; Wang, B.; Desai, J.; Wade, A.; Li, H.; Celikyilmaz, A.; Mehdad, Y.; Radev, D. CONFIT: Toward Faithful Dialogue Summarization with Linguistically-Informed Contrastive Fine-tuning. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online, 10–15 July 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 5657–5668. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, S.; Gan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Cheung, J.C.K.; Liu, J. Multi-Fact Correction in Abstractive Text Summarization. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; Webber, B., Cohn, T., He, Y., Liu, Y., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 9320–9331. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, M.; Dong, Y.; Wu, J.; Cheung, J.C.K. Factual Error Correction for Abstractive Summarization Models. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; Webber, B., Cohn, T., He, Y., Liu, Y., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 6251–6258. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, F.; Sone, K.; Roth, D. Improving Faithfulness in Abstractive Summarization with Contrast Candidate Generation and Selection. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online, 6–11 June 2021; Toutanova, K., Rumshisky, A., Zettlemoyer, L., Hakkani-Tur, D., Beltagy, I., Bethard, S., Cotterell, R., Chakraborty, T., Zhou, Y., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 5935–5941. [Google Scholar]

- Houlsby, N.; Giurgiu, A.; Jastrzebski, S.; Morrone, B.; De Laroussilhe, Q.; Gesmundo, A.; Attariyan, M.; Gelly, S. Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning for NLP. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; Volume 97, pp. 2790–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Bapna, A.; Firat, O. Simple, Scalable Adaptation for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; Inui, K., Jiang, J., Ng, V., Wan, X., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 1538–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.; Liu, Y.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Mohamed, A.; Levy, O.; Stoyanov, V.; Zettlemoyer, L. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; Jurafsky, D., Chai, J., Schluter, N., Tetreault, J., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 7871–7880. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Lam, W.; Bing, L.; Wang, Z. Deep Recurrent Generative Decoder for Abstractive Text Summarization. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 7–11 September 2017; Palmer, M., Hwa, R., Riedel, S., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 2091–2100. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).