Abstract

Nowadays, malware remains a significant threat to the current cyberspace. More seriously, malware authors frequently use metamorphic techniques to create numerous variants, which throws malware researchers a heavy burden. Being able to classify these metamorphic malware samples into their corresponding families could accelerate the malware analysis task efficiently. Based on our comprehensive analysis, these variants are usually implemented by making changes to their assembly instruction sequences to a certain extent. Motivated by this finding, we present a streamlined and efficient framework of malware family classification named MalSEF, which leverages sampling and parallel processing to efficiently and effectively classify the vast number of metamorphic malware variants. At first, it attenuates the complexity of feature engineering by extracting a small portion of representative samples from the entire dataset and establishing a simple feature vector based on the Opcode sequences; then, it generates the feature matrix and conducts the classification task in parallel with collaboration utilizing multiple cores and a proactive recommendation scheme. At last, its practicality is strengthened to cope with the large volume of diversified malware variants based on common computing platforms. Our comprehensive experiments conducted on the Kaggle malware dataset demonstrate that MalSEF achieves a classification accuracy of up to 98.53% and reduces time overhead by 37.60% compared to the serial processing procedure.

1. Introduction

In the digital age, networks became a prime target for many attackers. Malware is a prevailing weapon for attackers to launch network attacks and became a major challenge to cyberspace worldwide. In spite of the fact that anti-malware researchers put considerable efforts into the analysis task, it is still not ideal to curb malware attacks. Especially with high returns earned by malware, a consistent surge was found in malware attacks and obfuscated variants [1]. These variants are usually produced by modifying their binary codes or assembly instructions based on obfuscation techniques. Through the obfuscation process, the malware samples can change their structural characteristics and evade detection while preserving malicious functions [2]. The AV-TEST Institute reported that more than 350,000 fresh malware samples are discovered every day [3]. The proliferation of malware variants created a significant challenge for anti-malware analysis. To tackle the malware challenges, a significant amount of previous work was devoted to malware detection [4]. However, it is still a challenging issue to tackle with the obfuscated malware variants detection.

Motivated by the above-mentioned challenge, this paper focuses on the issues of malware variants classification aiming at accurately and effectively classifying the sheer number of variants into their families. Because it is a time-consuming workload to cope with the large quantities of malware samples, the first issue we need to consider is to simplify the feature engineering phrase.

To extract features from malware, two traditional methods are often used: static analysis and dynamic analysis [5]. Behavioral information of malware is derived from a malware sample without actual execution in static analysis. On the contrary, a malware program needs to be run actually in dynamic analysis mode. Compared with dynamic analysis, static analysis can achieve high accuracy and efficiency due to being free from the overhead of execution cost [6]. Among the features extracted from static analysis, Opcode sequences garnered significant interest from malware researchers and are widely used in anti-malware analysis, which is because assembly instructions can reveal program behavior characteristics [7,8]. In order to accelerate the classification of a huge amount of malware, we decided to conduct static analysis and extract features from the assembly instructions. In addition to simplifying feature engineering, another strategy that we take into account is to employ parallel processing techniques to accelerate the classification of these massive malware variants by utilizing our ordinary computing platforms.

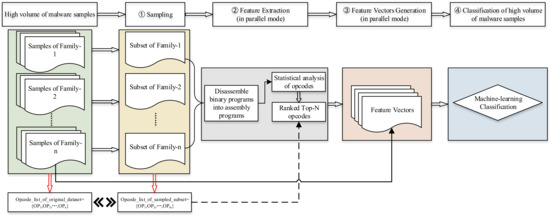

To this end, a light and parallel classification framework named MalSEF (a streamlined and efficient framework for detecting metamorphic malware families) is proposed in this paper. MalSEF mainly consists of four modules: sampling, feature extraction, feature matrix generation in parallel, and classification in parallel. MalSEF is implemented as follows. Firstly, select a small proportion of samples and construct a subset from the entire dataset according to a validated sampling criterion. Secondly, extract the Opcode sequence from the sampled subset to represent the entire dataset. Then, because the metamorphic technique is usually applied at the assembly instruction layer of malware, we analyze the behavioral characteristics based on the Opcode sequence, select the ranked Top-N Opcodes in frequency, and build a simple feature vector taking the frequency of Opcode as the eigenvalue to construct feature matrix in parallel for the initial dataset, based on the simple feature vector. The proposed parallel processing strategy is employed to reduce processing time and ameliorate processing efficiency for feature extraction and feature matrix generation from the entire dataset. By constructing the above lightweight feature set and applying the parallel processing strategy, the time overhead required for classifying large amounts of malware can be efficiently reduced. Finally, we evaluate MalSEF on the Microsoft Kaggle malware dataset and achieve promising classification accuracy. In addition, the processing time overhead can be reduced apparently compared with the serial processing mode. In conclusion, the following contributions are made in this paper:

- (1)

- We suggest to extract a small proportion of samples from the entire dataset according to the selection criteria and construct a simple and efficient feature vector from the assembly (ASM) files that can reflect the original dataset. The final evaluations prove that the lightweight eigenvector can not only attenuate the complexity of feature engineering, but also satisfy classification requirements.

- (2)

- We propose a parallel processing approach with commonly available hardware resources that utilizes collaboration of multi-core and active recommendation. The parallel strategy can run on the popular personal computer without high-performance hardware resources, and open the door for analysts to leverage general computers to tackle tough tasks due to the large volume of malware.

- (3)

- We conduct systematic assessments using the Microsoft Kaggle malware dataset. The classification accuracy can reach up to 98.53%. The parallel processing technique results in a 37.60% reduction in the processing time compared with the conventional serial process mode. MalSEF can deliver a similar performance to the first winner of the challenge competition with the feature space effectively simplified, outperforming the existing algorithms in terms of simplicity and efficiency.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides background information and summarizes related research; Section 3 describes the inspiration and framework of MalSEF; Section 4 presents the detailed implementation of MalSEF; Section 5 details the experiments and evaluations conducted on MalSEF; and the paper is concluded in Section 6.

2. Overview of Related Studies

A brief introduction of the necessary background knowledge and an overview of related research are provided in this section.

2.1. Background

2.1.1. Metamorphic Techniques

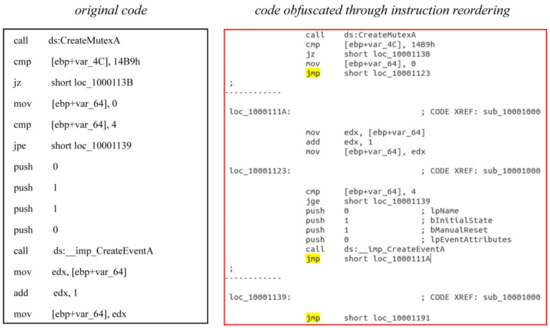

The purpose of metamorphism is to change its structure of the malware and generate new features at time of propagation, so as to avoid traditional feature-based detection [9]. Metamorphic techniques are quite widely used; some obfuscating method adopted in adversarial attacks [10] and backdoor attacks [11] can also be seen as metamorphism in a broader view, where metamorphism is usually implemented through resize and imperceptible perturbations [12]. As for malware, the metamorphic technique is usually applied in the assembly instruction layer, i.e., Opcode. The popular metamorphic methods include instruction reordering, dead/trash instruction insertion, and substitution [13]. The metamorphic technique is mainly applied at the assembly instruction level, which lies in the scope of this study (since the Kaggle dataset includes both assembly and binary formats of malware [14]). Below, we provide a brief overview of the common ways in which malware can be deformed.

- (1)

- Instruction reordering

Instruction reordering involves division of code into segments, permutation of these segments, and inserting branch instructions as necessary to maintain the initial functionality. This code manipulation is extremely effective in modifying the initial signature and may also be effective against structure inspection techniques, such as detecting the change in entropy [15].

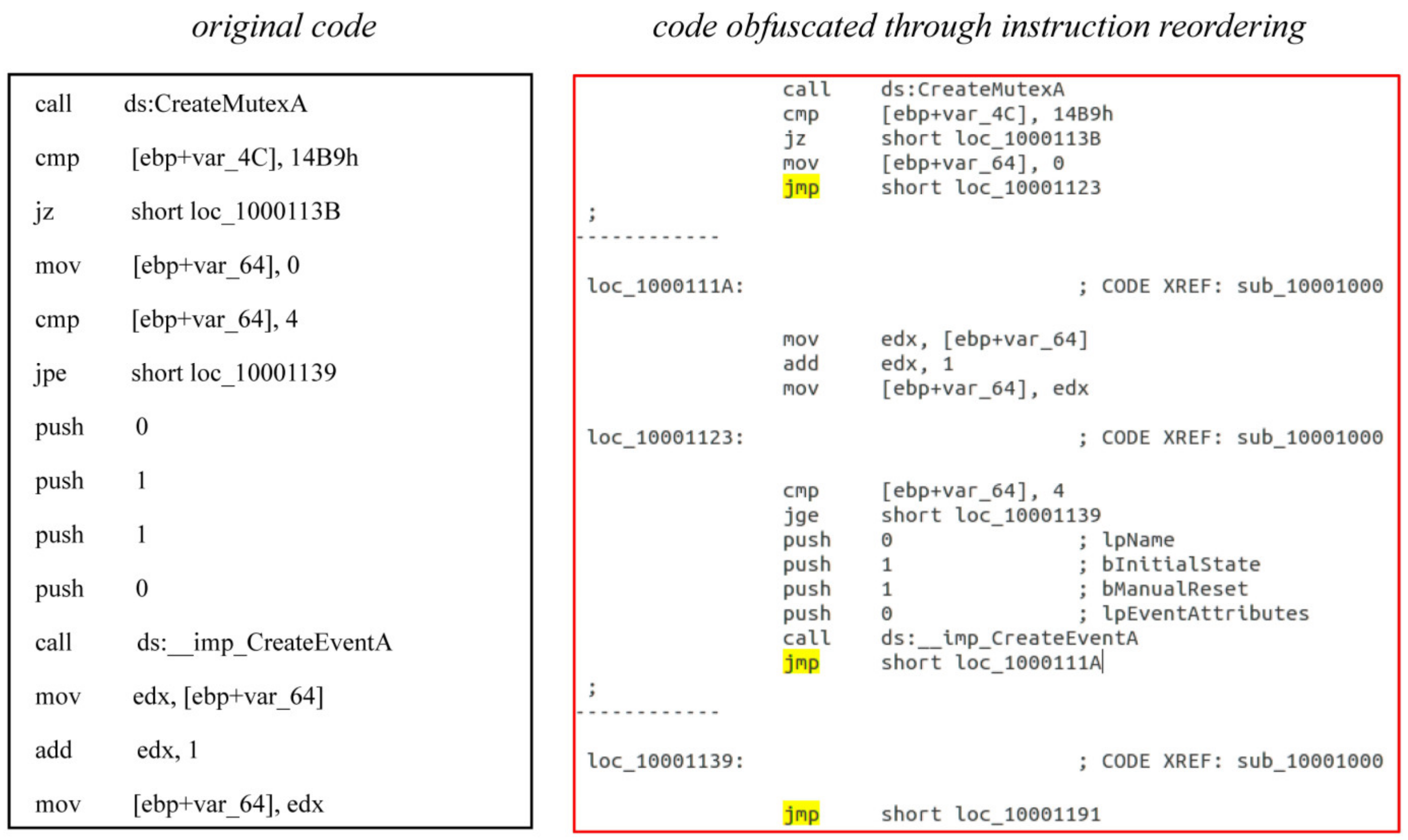

Instruction reordering can be realized in two ways. One way to accomplish instruction reordering is to randomize the sequence of instructions and remain the original control flow by inserting unconditional branches or jumps. As shown in Figure 1, the malware variant ‘BKXtxeYlLsprabEWIQhn’ in the Kaggle dataset employs this method to generate new variants. The other way is to swap independent instructions. Similar to compiling instructions, different compilers will generate different compilation instructions. The difference is that the goal of swapping instructions is to randomize the instruction stream.

Figure 1.

Example of metamorphism through instruction reordering.

This kind of metamorphism may interfere with the manual analysis process. However, many automatic analysis approaches that rely on intermediate representations, such as control flow diagrams or program dependency diagrams [16], can effectively overcome it because they are less sensitive to the unwanted changes in the control flow.

- (2)

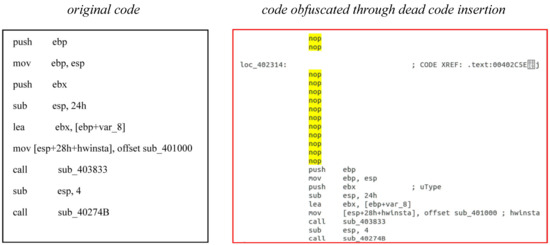

- Trash code or dead code insertion

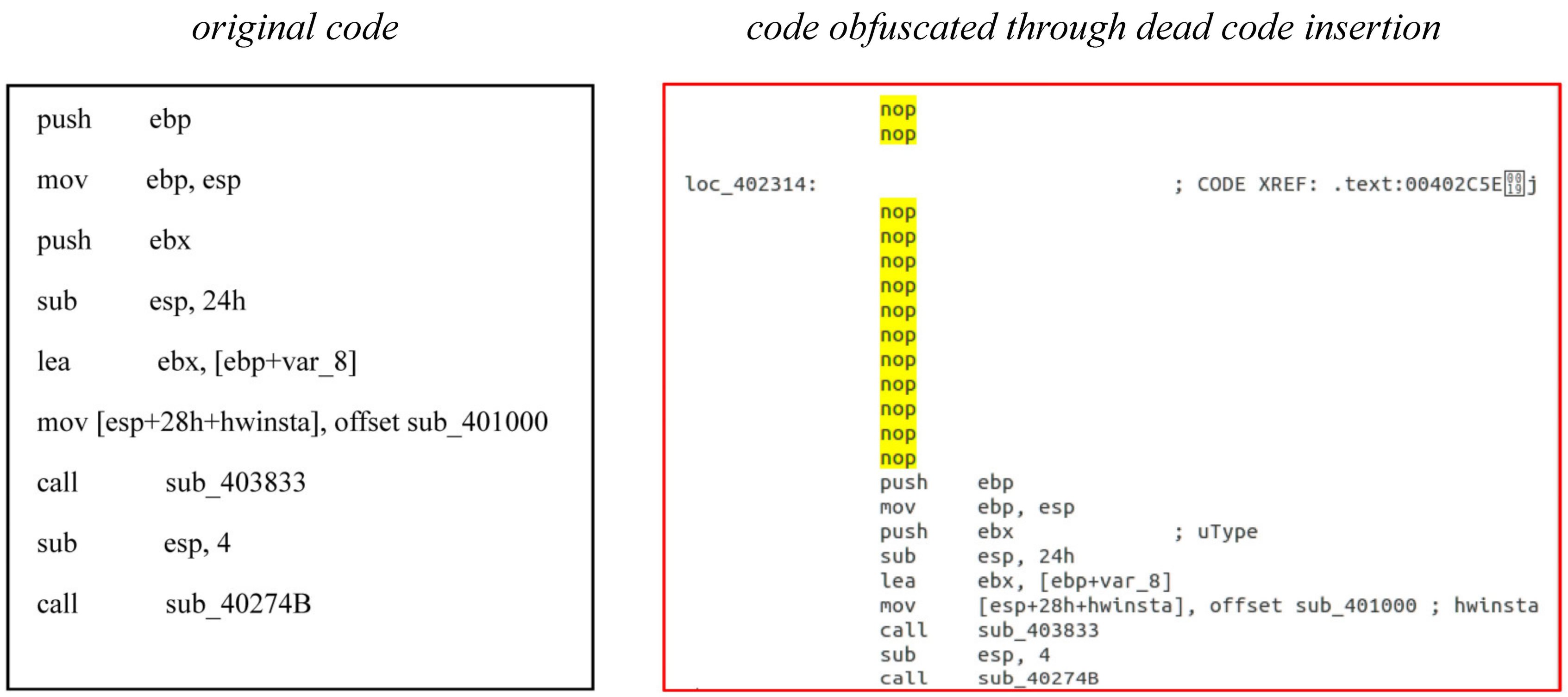

Trash instructions are “not do anything” instructions that are executed without any impact on program functionality. Trash/dead instruction insertion adds code to a program without changing the program’s original behavior. The simplest example is to insert a series of ‘nop’ instructions into a program. As shown in Figure 2, the malware variant ‘i5u2KDJ9t0OyAdokafj7’ in the Kaggle dataset employs this method to obfuscate and generate new variants.

Figure 2.

Example of metamorphism through dead code insertion.

Trash/dead instruction inserts are frequently used by malicious personnel to influence the detection based on features, and as for bypassing statistical detection, these metamorphic techniques are particularly effective.

- (3)

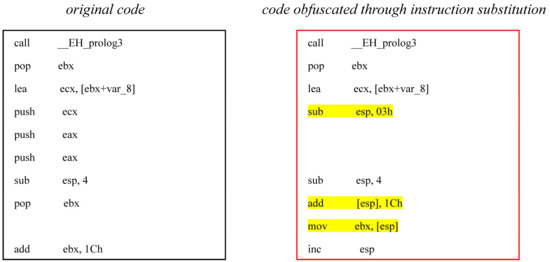

- Instruction substitution

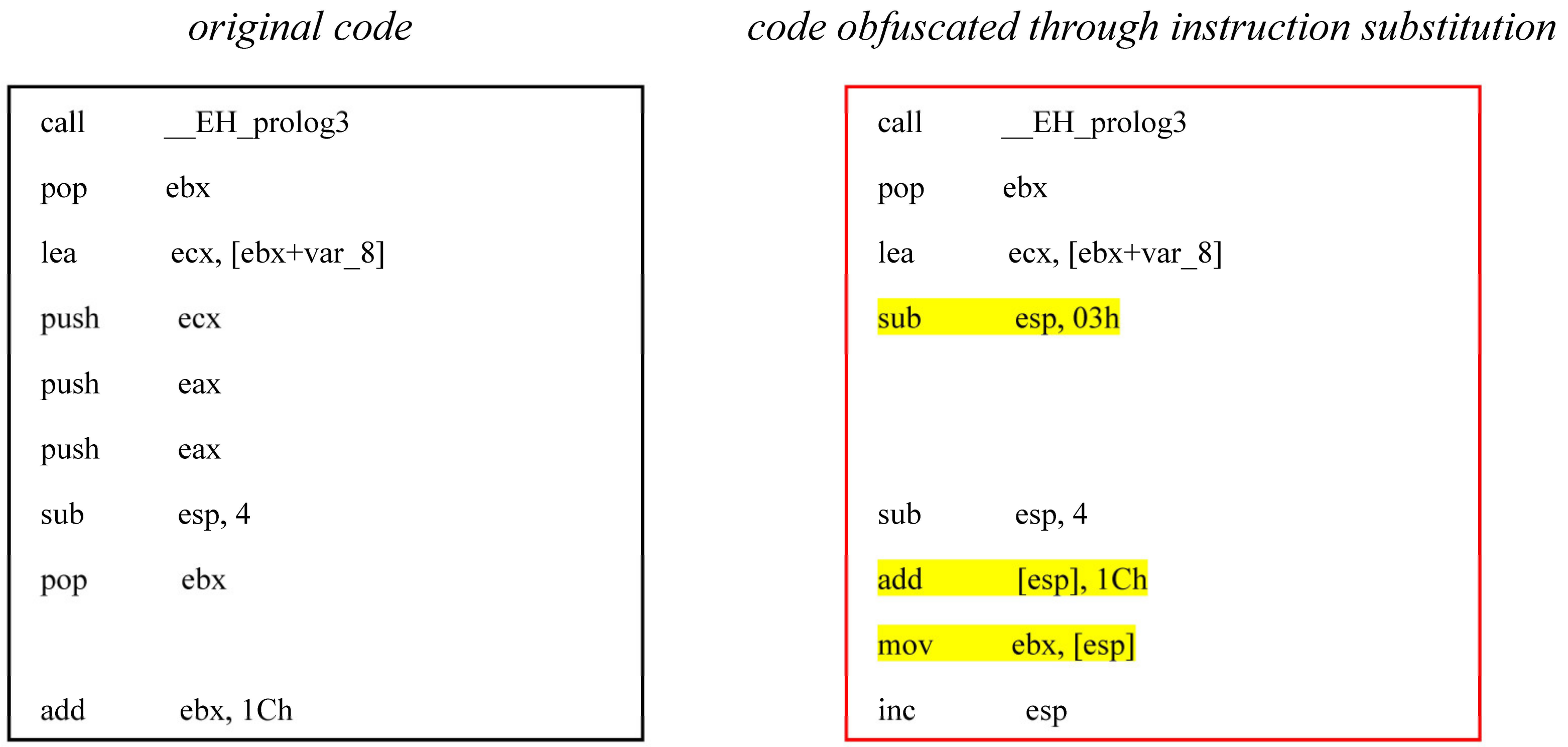

Instruction substitution means equivalent instruction replacement, which uses an equivalent instruction sequence dictionary to replace one instruction sequence with another.

The example of instruction substitution is illustrated in Figure 3. Because this modification relies on equivalent instruction knowledge, it makes the most serious obstacle to automatic analysis. The Intel Architecture 32-bit instruction set is abundant enough to perform the same operation in numerous ways. In addition, the IA-32 instruction set has some structural inconsistencies, such as a memory-based stack, which may be accessed by specialized instructions as a memory address. Operations of standard memory can also be accessed as a memory address, which makes the assembly language of IA-32 provide rich means for instruction replacement.

Figure 3.

Example of metamorphism through instruction substitution.

This kind of metamorphism is an effective way to evade feature-based detection and statistics-based detection. To tackle this form of obfuscation, an equivalent instruction sequence dictionary, which needs to be similar to the one used in generating the equivalent instruction, must be maintained for the analysis tool. This is not a fundamental way to tackle the instruction replacement problem, nevertheless, it is usually enough to handle usual situations.

2.1.2. Methods for Malware Analysis

In the field of malware analysis, two fundamental tasks are malware detection and malware classification [17]. To find malicious samples from unknown programs is the target of malware detection, while to separate malware into corresponding families is the target of malware classification. Features of programs extracted in the detection stage can still be used in the classification process. Based on the different ways of program feature extracting, methods of malware detection and classification are put into two categories: static and dynamic.

Static analysis does not run the program actually. To understand the malicious nature of a program, researchers usually gather information from its PE header, PE body, and binary code. Alternatively, they can disassemble the binary code and extract Opcodes or other pertinent details from the assembly program to characterize it [18]. The static analysis technique is more efficient but must contend with packaging and obfuscation disturbances.

Dynamic analysis is an approach based on behavior that needs to run the program to capture its run time behavior characteristics. The main behavior characteristics of the dynamic analysis method include program API sequence and behavior interaction with OS during run time. In order to avoid damage to the terminal system caused by malware, a virtual environment is usually used while dynamic analysis is performed [19,20].

Additionally, combining static and dynamic analysis, there are also researchers that conducted hybrid analysis. During the hybrid analysis, static and dynamic features are derived separately, and then fused together to overcome the defects of static or dynamic analysis alone, so as to achieve a more comprehensive and accurate analysis of malware [21,22].

2.1.3. Parallel Processing Techniques

Parallel processing is a technique that allows for the execution of multiple tasks simultaneously by dividing a serial work process into multiple processes or threads [23,24,25]. Some common parallel processing methods are as follows:

- (1)

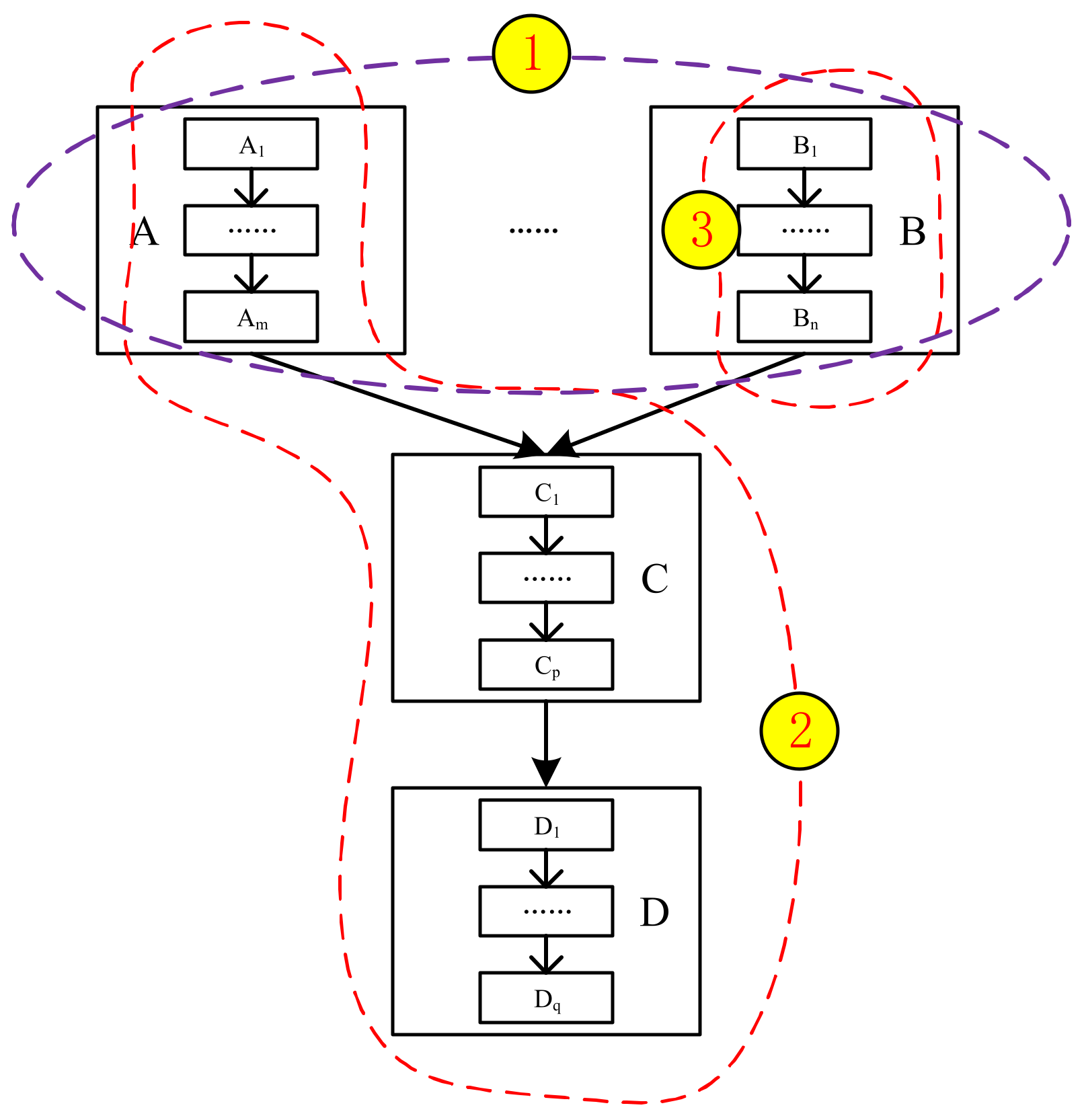

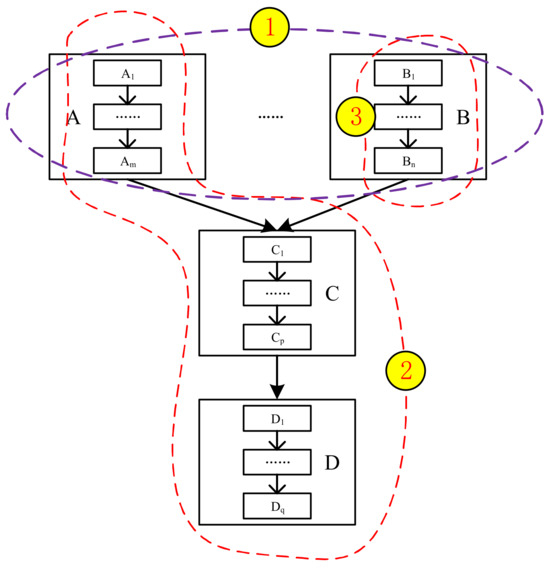

- Task parallel: during a complete working process, if there are some independent modules executing in parallel, this parallel processing method is called task parallelism. As shown in Figure 4, in this data flow diagram, when module A and B execute in parallel, it is called task parallel.

Figure 4. A data flow diagram.

Figure 4. A data flow diagram. - (2)

- Pipeline parallel: when a series of connected modules (forming a complete working process) process independent data elements in parallel (these data elements are usually a time series or an independent subset of a certain dataset), this parallel processing method is called pipeline parallelism. As shown in Figure 4, when modules A, C, and D execute in parallel, it is called pipeline parallel.

- (3)

- Data parallel: when a dataset can be divided into a number of subsets and these subsets can be processed simultaneously, this kind of parallel processing method is called data parallelism. As shown in Figure 4, if module B reads data in parallel, it is called data parallel.

2.2. Related Studies

Since the target of this research is malware family classification based on parallel processing technology, this section makes a brief summary of the relevant research work on malware family classification and malware analysis using parallel technologies.

In the process of malware classification, researchers usually extract different features to represent samples, and then select an automatic classifier to realize classification. For example, Bailey Michael et al. [26] proposed to describe malware behavior characteristics according to system state changes (such as file reading and writing, process creation, etc.). On this basis, malware is automatically classified into groups with similar behavior types in automatic mode, so as to handle the phenomenon of the sharp increase in malware scale and behavior difference. In addition, some researchers also proposed methods to analyze the binary code of malicious programs. Nataraj Lakshmanan et al. [27] applied the binary texture analysis method to analyze the malicious code and made a comprehensive comparison. The authors found that the binary texture analysis method not only achieves relatively high classification accuracy, but also surpasses the dynamic analysis by nearly 4000 times in speed. Furthermore, some of the current strategies can even be resisted by texture-based analysis.

In view of the sharp increase in the scale of malware variants, Ahmadi Mansour et al. [28] designed a novel classification strategy for malware family, utilizing the dataset of the Microsoft malware challenge as the research object. An innovative approach for feature set extraction and selection was devised to effectively characterize malware samples. According to the different characteristics of malicious code, the features were classified and weighted. This method can effectively address the challenge brought by the increasing variants of malware. To cope with the challenge of the increasing number of malware from an extensible perspective, Hu Xin et al. [29] proposed a machine learning framework that utilizes diverse content features (such as string, instruction sequence, section information, and other characteristics) and gathers intelligence information from external resources (such as anti-virus output). Several optimization methods were designed to further improve the performance of the classifier. Finally, an experiment was conducted on the Kaggle dataset of the Microsoft malware challenge to evaluate the performance of the propounded approach in processing malware datasets with a large scale. Considering that most malicious programs are variants created from existing malware, Lee Taejin et al. [30] presented a method for malware detection and classification in light of the local clustering coefficient. In this way, the classification reliability can be enhanced, the automatic selection and management of the malware family can be realized, and the large-scale malware can be classified efficiently.

Aiming at overcoming the limitations of current malware classification that requires domain knowledge, Raff Edward et al. [31] used a new representation named the SHWeL feature vector through expanding the concept of Lempel-Ziv Jaccard distance. The SHWeL vector improves the accuracy of LZJD, and its performance is better than the byte n-grams feature representation method, which can build an effective eigenvector input for classifier training and reasoning. In addition, Quan Le et al. [32] also presented a method of malware classification that does not require domain knowledge. This method converts a binary file into a one-dimensional representation and then constructs a deep learning network for automatic classification. The advantage of this method is that researchers do not need to extract features from malware, but only use the universal image scaling algorithm to convert a malware into a one-dimensional form of fixed size.

With the increase in the scale of malware, the analysis workload becomes more and more onerous. To ameliorate the efficiency of malware analysis, some researchers began to apply parallel and distributed processing technologies.

Junji NAKAZATO et al. [33] designed a new malware classification method to tackle the problems that existing methods are inadequate for achieving efficient and accurate classification. The authors initially conducted a dynamic analysis to automatically extract execution traces of malware, then employed their behavioral characteristics to classify them into distinct categories. In the process of obtaining behavior characteristics, the author adopted a parallel processing method to extract the API information of malware. Sheen Shina et al. [34] derived features of different categories from the executable file and applied them to the integrated classifier. The integration approach combined several separate pattern classifiers for better results. The problem was how to select classifiers of a minimum number and acquire the best results. This paper designed a compact integration technique using the harmony search method, which was derived from the music harmony-inspired algorithm. For malware detection, the simplified integrated classifier was used. For selecting the optimal subset of classifiers, multiple variegated classifiers were integrated into harmony and parallel search. Wang Xin et al. [35] used parallel machine learning and information fusion technology to achieve more effective detection. The author first extracted eight types of static features from the program and constructed two sets of features through feature selection; subsequently, a parallel machine learning model was employed to expedite the classification process. Finally, information fusion was achieved through probability analysis and Dempster–Shafer theory to complete the final detection.

Based on the above-introduced literature, the researchers made multi-aspect attempts at coping with the sharp increase in the scale of malware variants; nonetheless, there still exist apparent deficiencies as follows (as illustrated in Table 1):

Table 1.

Pros and cons of similar approaches for malware family classification and parallel processing.

- (1)

- The feature vectors constructed by these methods can usually effectively represent the features of malware. However, when applying to analyze massive malware, the feature space will become too large and bring a heavy burden to analysts. For example, the feature vector proposed by [28] can achieve perfect classification accuracy; however, its feature vector is too large to be realized under the condition of ordinary computing resources.

- (2)

- The parallel processing method above is usually applied to multiple classifiers for parallel detection. In essence, it is still a serial processing mode, and the parallel analysis target of massive samples is not achieved. When faced with a large scale of malware, it will inevitably affect the analysis efficiency.

3. Overview of MalSEF

3.1. Motivation

The malware detection process typically consists of two main stages: feature extraction and detection/classification, which constitute a serial process [6]. Malware detection and malware classification are two distinct tasks. The former aims to determine whether an unknown sample is malicious, while the latter involves grouping detected malware into its most appropriate family. In the current cyberspace environment, we are witnessing a surge in malware families, coupled with a high number of variants within each family, posing a significant challenge to the anti-malware community [2].

Actually, the scale of malware volume is increasing mainly due to the widespread application of metamorphic technologies. The metamorphic malware will modify its code structurally while maintaining its functionality at time of propagation. How to cope with the large volume of metamorphic malware variants and group them into appropriate families became a crucial task for the security community. During the grouping process, the following challenges need to be addressed:

- (1)

- The complexity of feature engineering may increase sharply due to the large scale of malware variants. The complexity is mainly derived from two aspects: (1) The feature set of the cutting-edge analysis methods is usually fairly complicated, because we often utilize APIs or Opcodes, or their combination (n-grams) as the feature vector to profile the malware. The number of API and Opcode on the Win32 platform is relatively large. (2) The increasing volume of malware variants will further aggravate the complexity, especially in the current massive malware environment.

- (2)

- The efficiency of coping with the sheer number of malware samples cannot be guaranteed. The existing detection methods mainly include the training stage and detection stage. These two stages are separately implemented and the detection process is essentially a serial processing one. We may inevitably fail to tackle the challenge facing the environment of large-scale malware.

Driven by the above issues, we put forward the following ideas in this paper:

- (1)

- How to establish a simple feature set for the large number of malware variants so as to alleviate the computation cost and deliver satisfactory classification performance simultaneously?

- (2)

- How to efficiently handle numerous malware variants and classify them into their homologous families to ensure the efficiency of the classification process?

- (3)

- How to implement the complicated task for analyzing a huge amount of malware on a simple personal computer, so as to enable ordinary researchers to accomplish the seemingly impossible task due to the conventional paradigm?

The answers to these questions were already provided in previous studies. Motivated by the above inspiration, we aim to propose a lightweight approach for ordinary researchers to perform heavy analysis tasks using common computing platforms.

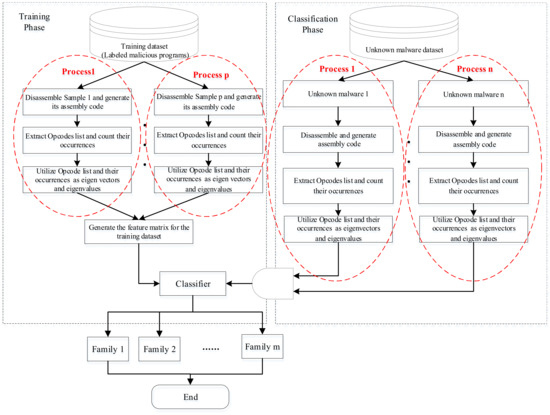

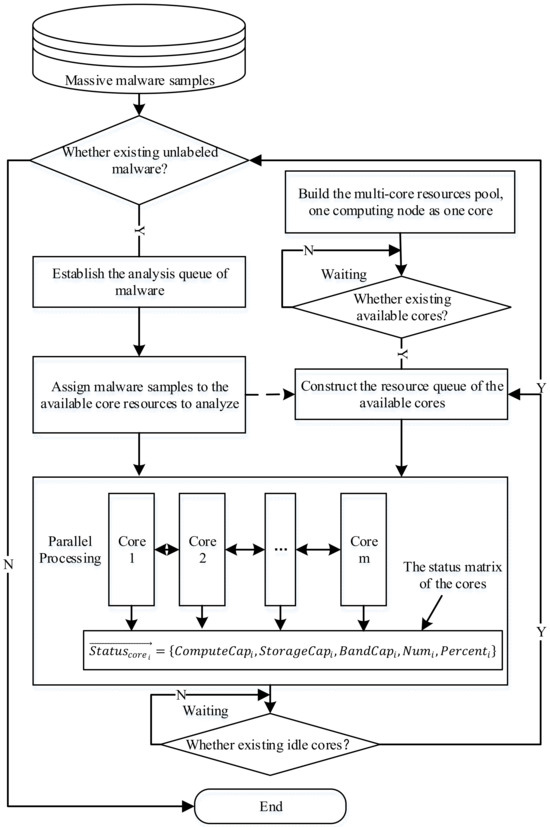

3.2. Parallel Processing Model of Massive Malware Classification

Based on the principle of parallel processing technology, the procedures in malware detection that can be optimized by parallel processing include:

- (1)

- In the training stage, the process of extracting features from the training set include “assembly commands of samples → extracting Opcode lists → counting the occurrences of every Opcode → generating feature vectors → generating feature matrices”, which can be implemented in parallel mode.

- (2)

- In the detection stage, the process performing on unknown samples include “assembly commands of samples → generating feature vectors → classification”, which can be implemented in parallel mode.

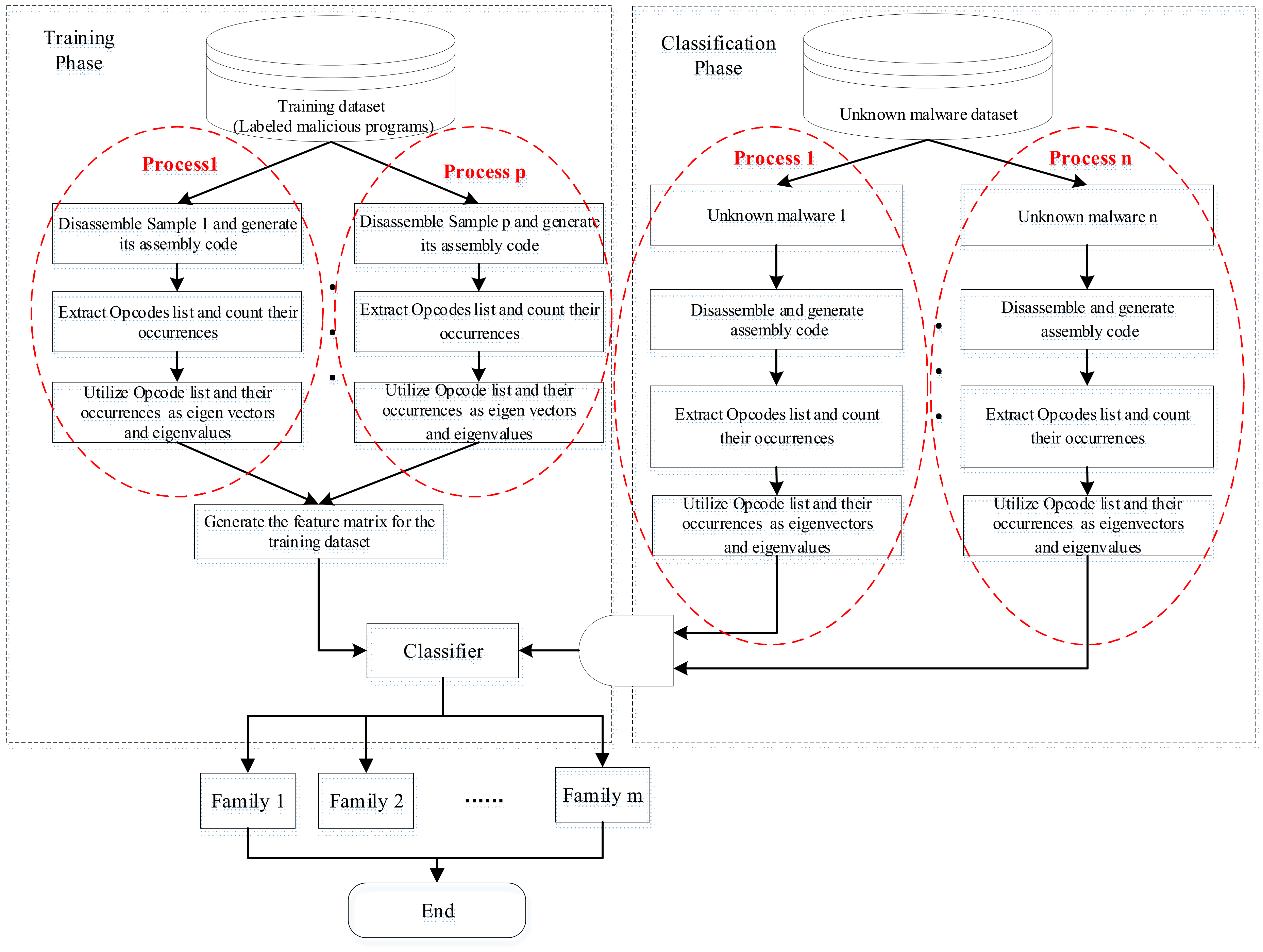

By considering the above malware analysis process, we employ parallel processing techniques to compress the needed analysis time and boost the malware classification efficiency. According to the above discussion, the malware classification process in parallel is designed as displayed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Parallel classification model of massive malware.

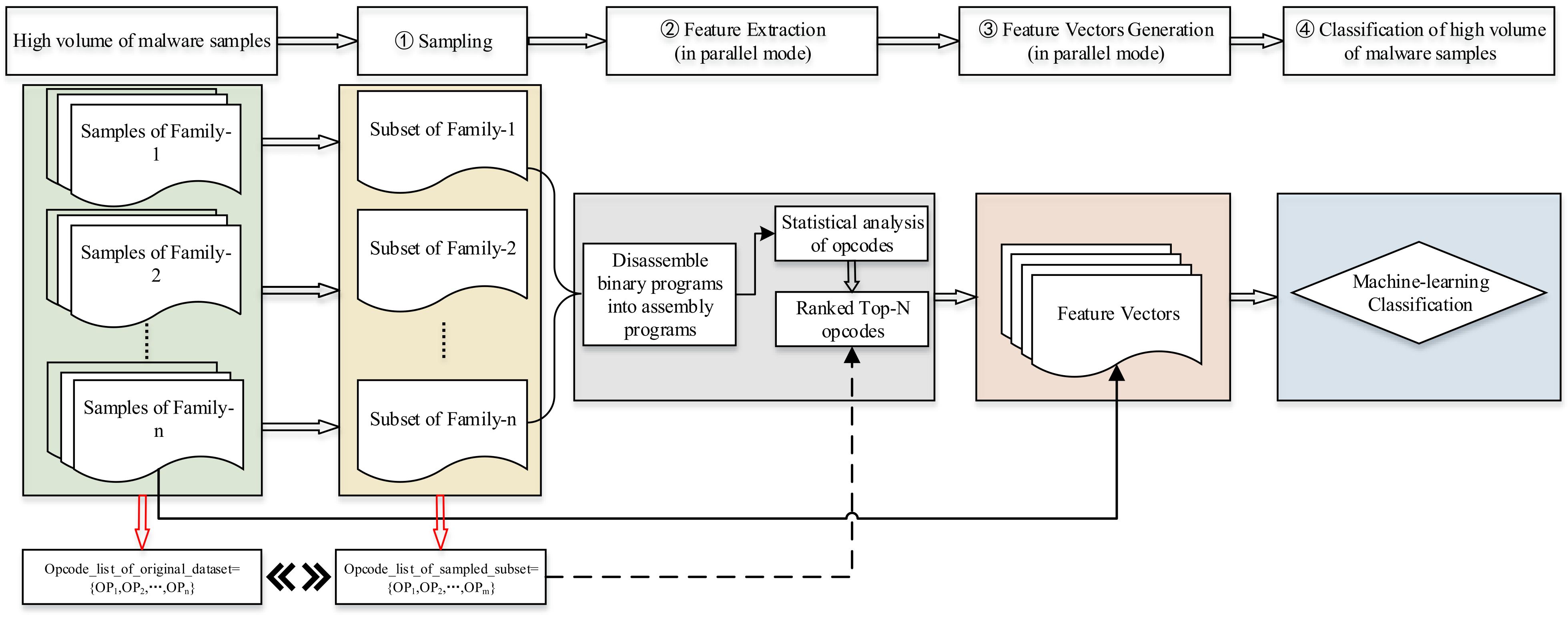

3.3. Overall Framework of MalSEF

MalSEF mainly includes four modules, namely, sampling of massive samples, feature extraction, feature vector generation, and classification, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The framework of MalSEF.

- (1)

- Sampling of massive samples

The task of this module is to construct sampled subsets that consist of a small part of samples randomly selected from each family of the massive samples collected, which will be used as the data source for feature extraction. The purpose of this module is to select features from subsets of samples to represent the original dataset rather than extract features directly from massive samples, so as to attenuate the complexity of the extraction of features. The subset size is determined on the criteria of selecting a smaller quantity of samples from the entire dataset and obtaining the same results that reflect the original dataset as previously as needed [36].

- (2)

- Feature extraction

Because the malware program is often in the form of binary code, we have to firstly convert the binary malware programs into assembly programs. The most frequently used disassembling tool is IDA Pro. In our study, because the experiment dataset of this paper is released by Microsoft in Kaggle, which is in the form of the assembly instructions after disassembling, accordingly, features can be extracted statically from the assembly programs of malware samples. This module first counts the occurrences of every Opcode in the sample subsets and then ranks Opcodes according to their occurrence frequencies. Finally, the Top-N ranked Opcodes are selected as the feature vector (Top-N is set by researchers flexibly) and the number of occurrences of each Opcode is taken as its feature value.

- (3)

- Feature matrix generation

After generating feature vectors in the previous module, the task of this module is to generate the feature matrix for the samples. According to the experimental method of cross-validation, we need to generate feature matrices for the samples in the training set and testing set, respectively. Among them, the training set is a labeled dataset, and the test set is an unlabeled dataset. Since the number of samples in the testing set is much larger than that in the training set, it requires more time to construct feature matrices for the testing set. To this end, we adopted a parallel processing approach to generate feature matrices for the testing set.

- (4)

- Classification of massive malware samples

Having gotten the feature matrix as illustrated above, we can verify the result of MalSEF by cross-validation.

4. Detailed Implementations of MalSEF

This section describes the implementation of MalSEF in detail.

4.1. Sampling from the Massive Samples Set and Feature Extraction

4.1.1. Sampling from the Massive Sample Set

The aim of this module is to select a certain number of samples from each family to form a subset for each family. The size of each subset is determined by a sample size determination criterion. The required sample size is decided based on the following formula.

where: is expected sample size; is standard normal deviation of expected confidence level; is the assumed proportion of the target population with an estimated particular characteristic; ; and is the degree of accuracy expected in estimated proportion. This is a theoretical formula that is used to determine the number of selected samples under a certain expected confidence level and certain marginal error, allowing to represent the overall samples in a statistical sense. It is based on the assumption that the samples follow a normal distribution, noting that the expected confidence level is determined by z (e.g., z = 1.96 for 95% confidence level), and the marginal error is determined by d (e.g., d = 0.01 for a margin of error of 1%). As for p, when z and d are given and the estimator p is not known, p = 0.5 can be used to yield the largest sample size, which is the p value we used in this research.

The formal description of the sampling process is as follows:

where , and .

Description of the algorithm implementation of the sampling process is illustrated as Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Sample a subset from the original dataset | |||

| //S represents the original dataset. | |||

| // represents the set of standard normal deviations for desired confidence level of original dataset. | |||

| // represents the set of assumed proportions in the target population of original dataset. | |||

| // represents the set of degrees of accuracy desired in the estimated proportion of the original dataset. | |||

| Input: the original malware dataset S, , , | |||

| Output: the sampled malware subset S’ | |||

| 1: | trainLabels = readDataset() //read the original dataset | ||

| 2: | labels = getLabels(S) //read the labels of the original dataset | ||

| 3: | for i = 1 to labels do | ||

| 4: | mids = trainLabels[trainLabels.Class == i] //get the samples of Class == i | ||

| 5: | mids = mids.reset_index() //reset the index of the samples of Class == i | ||

| 6: | //calculate size of the subset for the ith original dataset | ||

| 7: | for j=1 to do | ||

| 8: | rchoice = randit(0, ) //select digits from 1 to 100 randomly | ||

| 9: | rids = mids [1, rchoice] //build the subset for the Class = i | ||

| 10: | end for | ||

| 11: | S’.append(rids) //append the subset of Class == i to S’ | ||

| 12: | end for | ||

| 13: | return S’ | ||

4.1.2. Feature Extraction and Feature Vectors Construction

Opcode is a mnemonic of machine code, which is usually represented by assembly command [2]. Because this paper is based on a dataset released by Microsoft in Kaggle, which contains the assembly program of malware, we build the features of samples by extracting Opcodes from the assembly program. The procedure of extracting features using the sampled subset is as follows:

- (1)

- Analyze samples in the subset one by one and extract Opcodes from each sample;

- (2)

- Count the occurrences of each Opcode in the subset;

- (3)

- Sort Opcodes based on their occurrences;

- (4)

- Select Top-N Opcodes as the feature vector (the value of Top-N is set by the researchers flexibly).

- (5)

- Construct the feature matrix by counting the occurrence numbers of each opcode in each set as the feature value for the feature element.

The description of the implementation process of feature extraction and feature vectors construction is illustrated as Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: Feature matrix construction | ||

| Input: assembly programs of the malware samples | ||

| Output: the feature matrix | ||

| 1: | for i=1 to do | |

| 2: | //Append the opcodes of the analyzed program to the Opcode list | |

| 3: | ||

| 4: | //Build the opcode sequence of all the programs | |

| 5: | ||

| 6: | //Count the occurrence times of each Opcode | |

| 7: | ||

| 8: | end for | |

| 9: | //Sort the Opcode sequence based on occurrences | |

| 10: | ||

| 11: | //Select the ranked Top-N Opcodes as the feature vector and their occurrences as the feature values | |

| 12: | ||

| 13: | return | |

4.2. Feature Extraction with Multi-Core Collaboration and Active Recommendation in Parallel

Parallel processing in the procedures of massive malware detection has the following characteristics:

- (1)

- Within the two procedures of parallel processing described in Section 3.2, the relationship between tasks in each procedure is loosely coupled.

- (2)

- In the two procedures of parallel processing described in Section 3.2, we should adopt the iteration method to tackle the distributed parallel tasks load in the practical processing.

- (3)

- In the procedure of parallel processing, different tasks will inevitably lead to different running speeds because of the different performance of the running environment and different computational load. Thus, tasks should be adaptively distributed according to the practical performance of each running node.

Based on the characteristics of the above procedures of parallel processing, we consider using the idea of multi-core to build multiple task nodes to extract code features in parallel. According to the practical implementation of each task, we can actively assign processing tasks to better performance nodes or faster nodes, so as to achieve parallel feature extraction of massive malware.

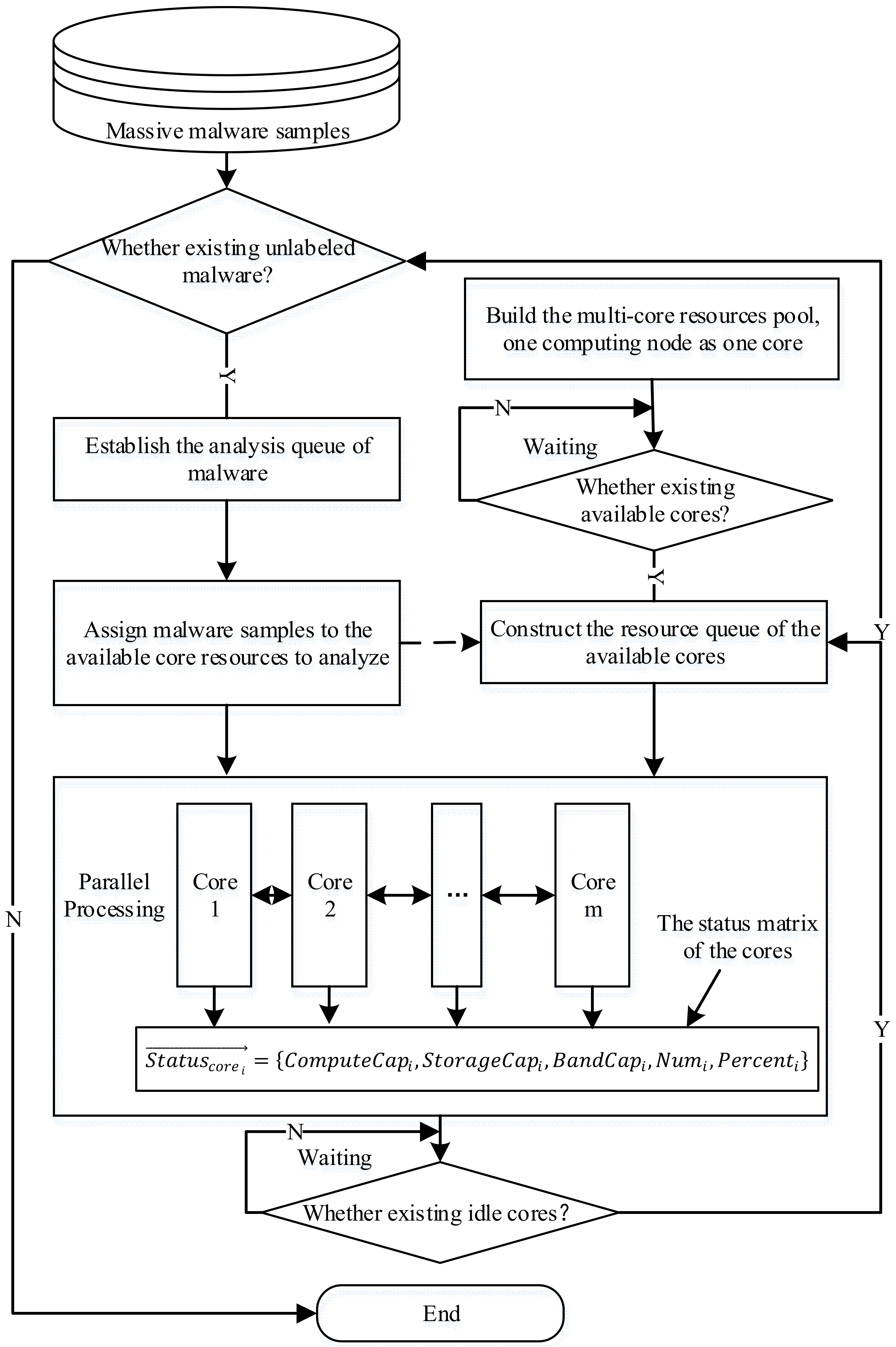

To this end, we design a parallel processing method with collaboration among multi-cores and active recommendation. Figure 7 illustrates the procedure, and the comprehensive implementation process is as listed below:

Figure 7.

Feature extraction with multi-core collaboration and active recommendation in parallel.

- (1)

- Construct the analysis sample queue based on the malware sample sets. The queue is illustrated as follows:

- (2)

- Construct a multi-core resource pool based on the computing resource nodes, each of which serves as a processing core. The core pool is illustrated as follows:

- (3)

- Query the current available resources in the resource pool and establish a queue of current available resources. The available resource queue is depicted as below:

- (4)

- According to the currently available resource queue, the master node (the node that stores the sample sets) fetches samples from the sample sets and allocates them to the resource queue for processing.

- (5)

- In the procedure of task parallel processing, each node monitors its own running state in real time, maintains and updates its own state vector in real time, and communicates the state vector information with each other. Based on the real-time interactive state vector information among the cores, the state vectors are combined to form a global state matrix within the cores.

The state vector describes the progress of current task processing, computational resource consumption, storage resource consumption, bandwidth resource consumption, and the number of tasks that were assigned in a node. The state vector is illustrated as follows:

The elements in the state vector are defined as follows:

- (1)

- : computational resource consumption of node i;

- (2)

- : storage resource consumption of node i;

- (3)

- : bandwidth resource consumption of node i;

- (4)

- : the number of tasks assigned to node i;

- (5)

- : the progress of current task processing of node i.

In order to ensure a reasonable allocation of the subsequent tasks when combining the state vectors of each node to construct the state matrix, it is essential to rank the nodes based on their real-time status. Nodes with a lighter load are positioned higher, while those with a heavier load are placed lower.

To this end, after receiving the state vectors from other nodes, each node compares the values of each element in the state vector according to the importance order of “”, and forms the final state matrix, which is described as follows:

- (6)

- The master node will continuously monitor the state matrix and sort the samples to be analyzed. Once a node finishes its task, it notifies the master node, which then assigns new samples to that node, allowing it to start a new processing task. By this way, our method realizes the real-time and active pushing of processing tasks.

- (7)

- Run continuously until the samples are processed entirely according to the above scheme.

5. Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Configuration

Hardware: Lenovo ThinkStation, Intel® CoRE™ i7-6700U CPU@3.40GHz×8, 8 GB memory (Made by Lenovo in China).

Operating system: 64 bit Ubuntu 14.04.

5.1.1. Dataset

In the evaluation phase, we use the training dataset released by Microsoft in Kaggle, which includes 10,868 malicious samples. We carry out cross-validation on the training dataset directly because we could not obtain the labels of the testing samples. Each malware sample has a 20-character hash value as its ID. The dataset comprises nine distinct malware families, namely Ramnit (R), Lollipop (L), Kelihos ver3 (K3), Vundo (V), Simda (S), Tracur (T), Kelihos_ver1 (K1), Obfuscator.ACY (O), and Gatak (G). Each sample family is assigned a class label from 1 to 9. The training dataset is shown in Table 2, which illustrates the distribution of each malware family.

Table 2.

Experimental dataset.

5.1.2. Classifier

During the malware classification stage, we use data mining techniques to automate the task. To evaluate the effectiveness of MalSEF, we apply four different classifiers for identifying malware, including decision tree (DT), random forest (RF), K-nearest neighbor (KNN), and extreme gradient boosting (XGB), which are commonly used in the fields of data mining, information security, and intrusion detection [37].

5.2. Experimental Results and Discussion

We evaluate MalSEF comprehensively through detailed experiments in this section. Firstly, we build Opcode lists from the original samples set and the sampled subset separately and evaluate the classification effect of the total sample set using different Top-N Opcode lists, which are selected to construct feature vectors. Secondly, we apply the parallel processing technology in the procedure of classification based on the origin sample set and sampled subset separately, and verify the effect of parallel classification. Finally, we compare MalSEF with similar studies comprehensively.

5.2.1. Classification Using Features Derived from the Original Set and the Sampled Subset

This section indirectly evaluates the effect of using a sampled subset to characterize the original dataset. Features are extracted from the original set and the sampled subset, respectively, and then we classify the Train dataset to evaluate its classification effect.

Composition of the Sampled Dataset—Subtrain

In the experimental stage, we first select a small part of samples from the whole experimental dataset to form the subset, which is used to construct feature vectors. Because the experimental dataset we applied in this research is the Train dataset from Microsoft in Kaggle, we named this subset as Subtrain. Subtrain consists of 803 samples with specific information as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Subtrain: the sampled dataset from the Train dataset.

Evaluation of the Classification Results Using Features Extracted from the Entire Train Dataset

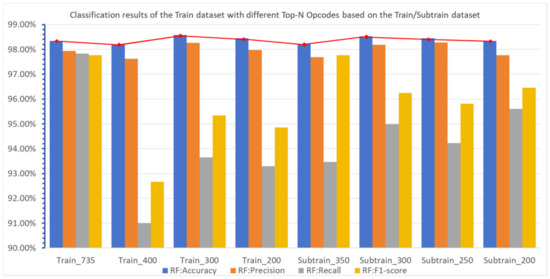

By analyzing the dataset released by Microsoft in Kaggle, we find that there are 735 Opcodes in the Train dataset. To verify the impact of the 735 Opcodes on classification results, we rank them according to their occurrences and select Top-N Opcodes as the feature vector to verify the final classification effect.

We first select various Top-N Opcodes to generate feature vectors, followed by conducting 10-fold cross-validation experiments using random forest (RF), decision trees (DT), support vector machine (SVM), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBST) classifiers. We utilize the open-source Python library Scikit learn (version 1.0.2) and opt for the default values when it comes to setting the hyper parameters for various classification methods which makes it easier to ensure the generalization ability of MalSEF without intentional optimization. The classification outcomes are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Evaluation of the classification results according to various Top-N Opcodes extracted from the Train dataset.

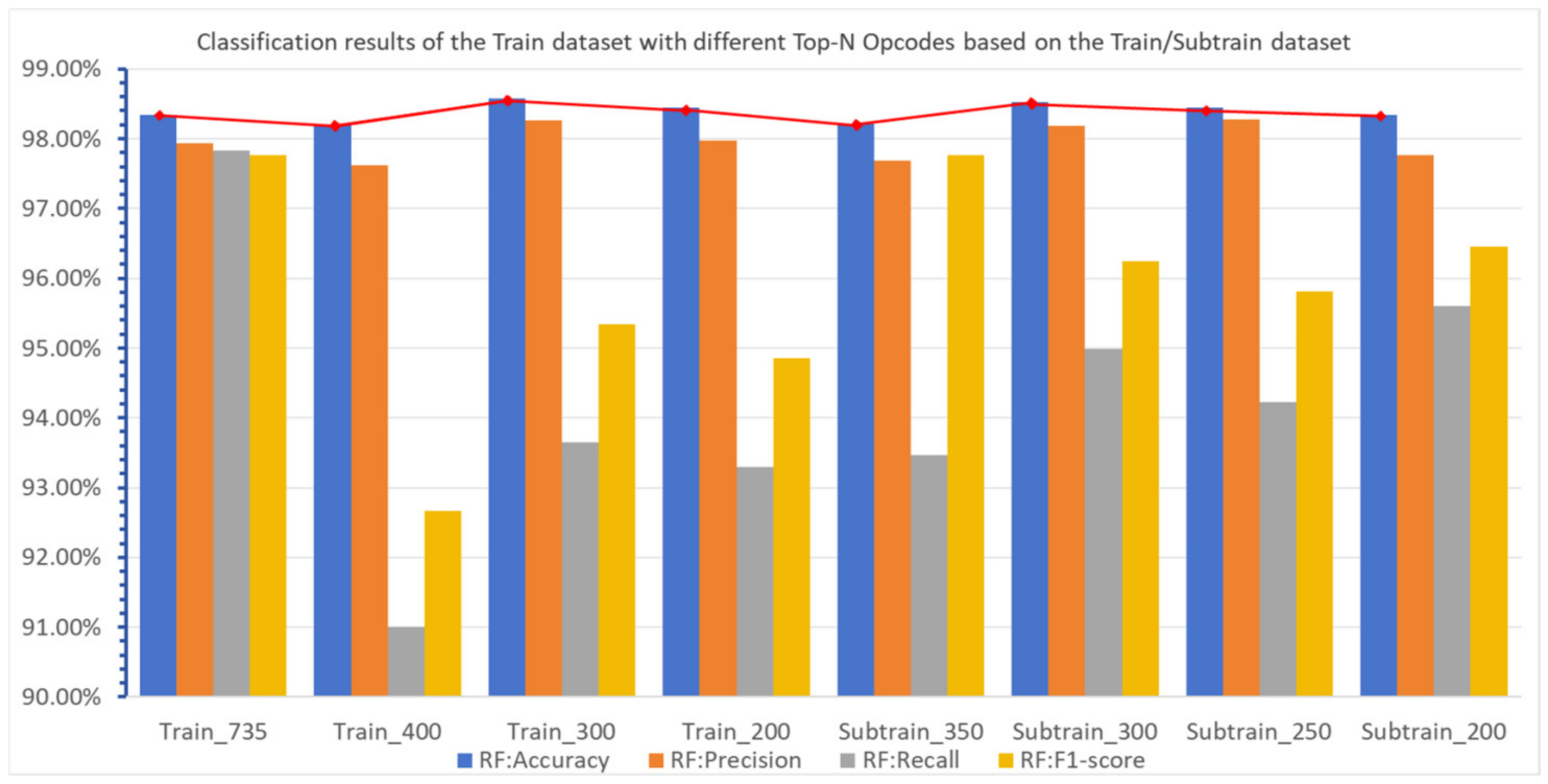

As can be seen from Table 4, results of classification are similar using different Top-N Opcodes. The classification effect of the RF classifier with different Top-N opcodes is as shown in Figure 8, where Train_N stands for Top-N Opcodes extracted from the Train dataset and the fold line at the top portrays the variation in accuracy when the selected number of opcodes is changed.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the classification results of RF classifier with different Top-N Opcodes based on Train/Subtrain dataset.

The results of this experiment demonstrate that selecting all Opcodes as feature vectors is not necessary to represent the characteristics of samples. Because there exists redundancy in the extracted Opcode lists, only a part of key Opcodes is needed to achieve the desired classification effect.

Evaluation of the Classification Results Using Features Extracted from the Sampled Subtrain Dataset

In order to verify whether the sampled set Subtrain can comprehensively and effectively represent the features of the Train set, in this section, we use the sampled Subtrain set as a data source to count the occurrences of all Opcodes and sort them. Subsequently, various Top-N opcodes are chosen as the feature vector to create feature matrices for the original Train set. Finally, we carry out cross-validation experiments on the Train set to verify the validity of using the sampled subset to classify the original set.

There are 394 different Opcodes extracted from the Subtrain set, and we chose different Top-N Opcodes to classify the Train set separately. Outcomes of the experiment are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Evaluation of the classification results according to various Top-N Opcodes extracted from the Subtrain dataset.

We compare the classification effects of RF classifier with different Top-N Opcodes, and the outcome is as follows, illustrated in Figure 8, where Subtrain_N stands for Top-N Opcodes extracted from the subTrain dataset and the fold line at the top portrays the variation in accuracy when the selected number of opcodes is changed. We can see that when 350, 300, 250, and 200 Opcodes are selected as the feature vector, the classification accuracy all exceed 98%, and the highest reaches up to 98.53%. We can draw the conclusion from this part of the experiments that the classification effect can meet our requirements when we use the Subtrain dataset to characterize the original Train dataset.

5.2.2. Experimental Results of Parallel Processing

This section is divided into stages of feature extraction, classifier training, and practical detection. We carry out cross-validation according to serial processing and parallel processing separately, and compare the experimental results of the two different processing modes.

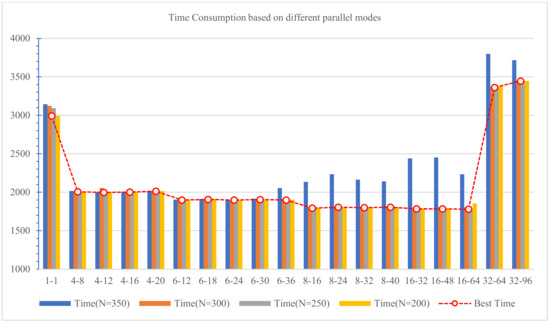

Experimental Results of Parallel Processing of Train Dataset with Top-N Opcodes Extracted from Subtrain

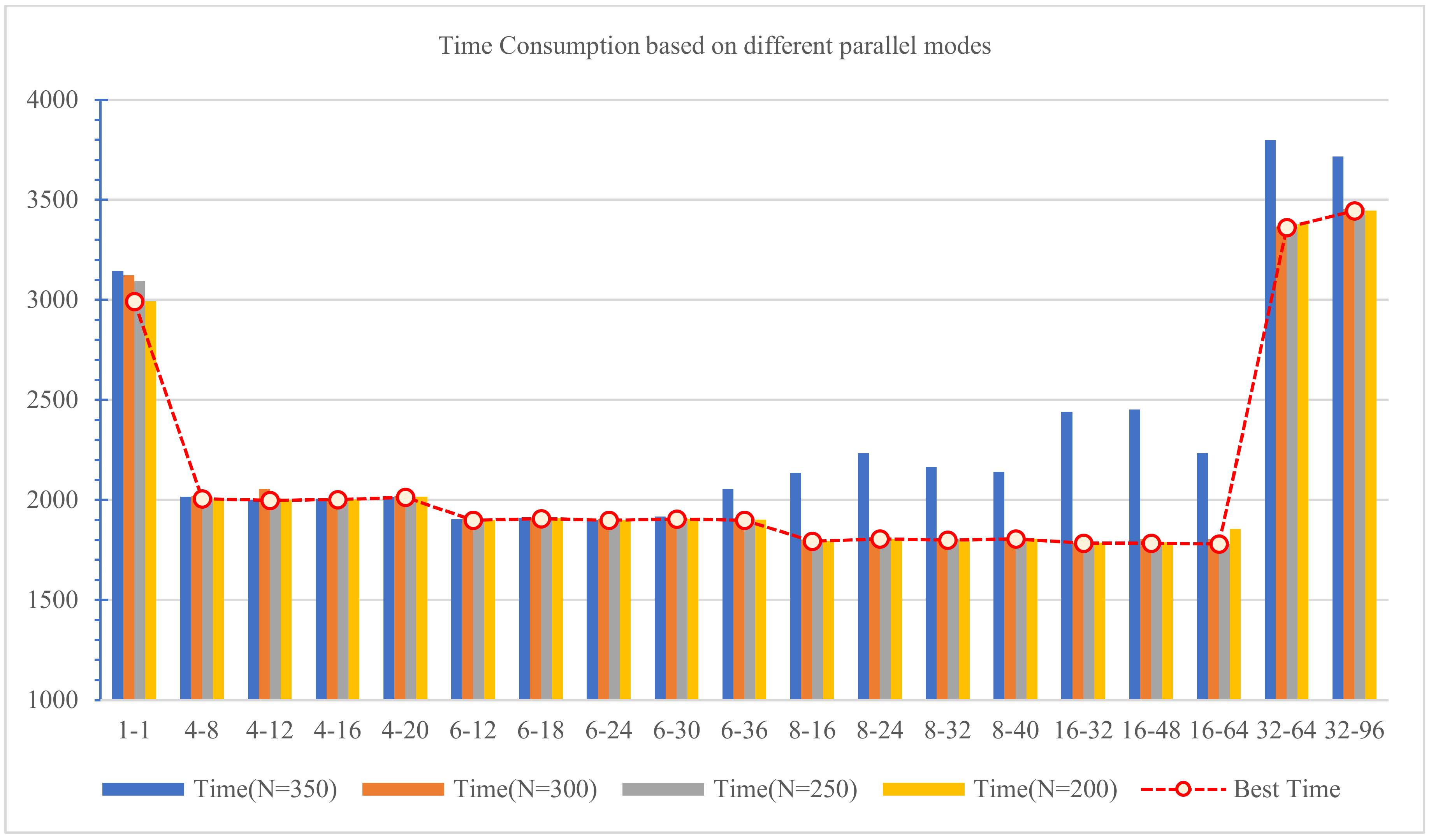

Because the Subtrain is small, it takes only 3.86 s to extract the Opcode lists from the Subtrain subset. Then Top-N Opcodes are selected as the feature vectors to generate the feature matrix for the Train dataset, which is a time-consuming process. We use the parallel processing mode designed in Section 4.2 to realize the feature generation process. The effect of parallel processing with different parameters is shown in Table 6, where the first row, designated with a yellow background, is serial processing, and the most efficient parameter settings for parallel processing are indicated in red. We compare the experimental result of parallel processing visually and compare the optimal time performance of each parallel setting with different Top-N, as shown in Figure 9.

Table 6.

Experimental result of the parallel generation of feature vectors with Top-N Opcodes extracted from Subtrain.

Figure 9.

Comparison of time consumption based on different parallel modes.

The experimental outcomes allow us to draw the following conclusions:

- (1)

- The smaller the Top-N that is selected, the less the processing time is, because the shorter feature vector will result in less processing workload and less time consumption.

- (2)

- The time of parallel processing is the shortest when generating 16 processes and processing 32 samples each time, i.e., 2 samples are allocated to each process for analysis. This is because the personal PC workstation used in our experiment has eight cores. According to this setting, we can make the best use of computing resources and obtain the best results.

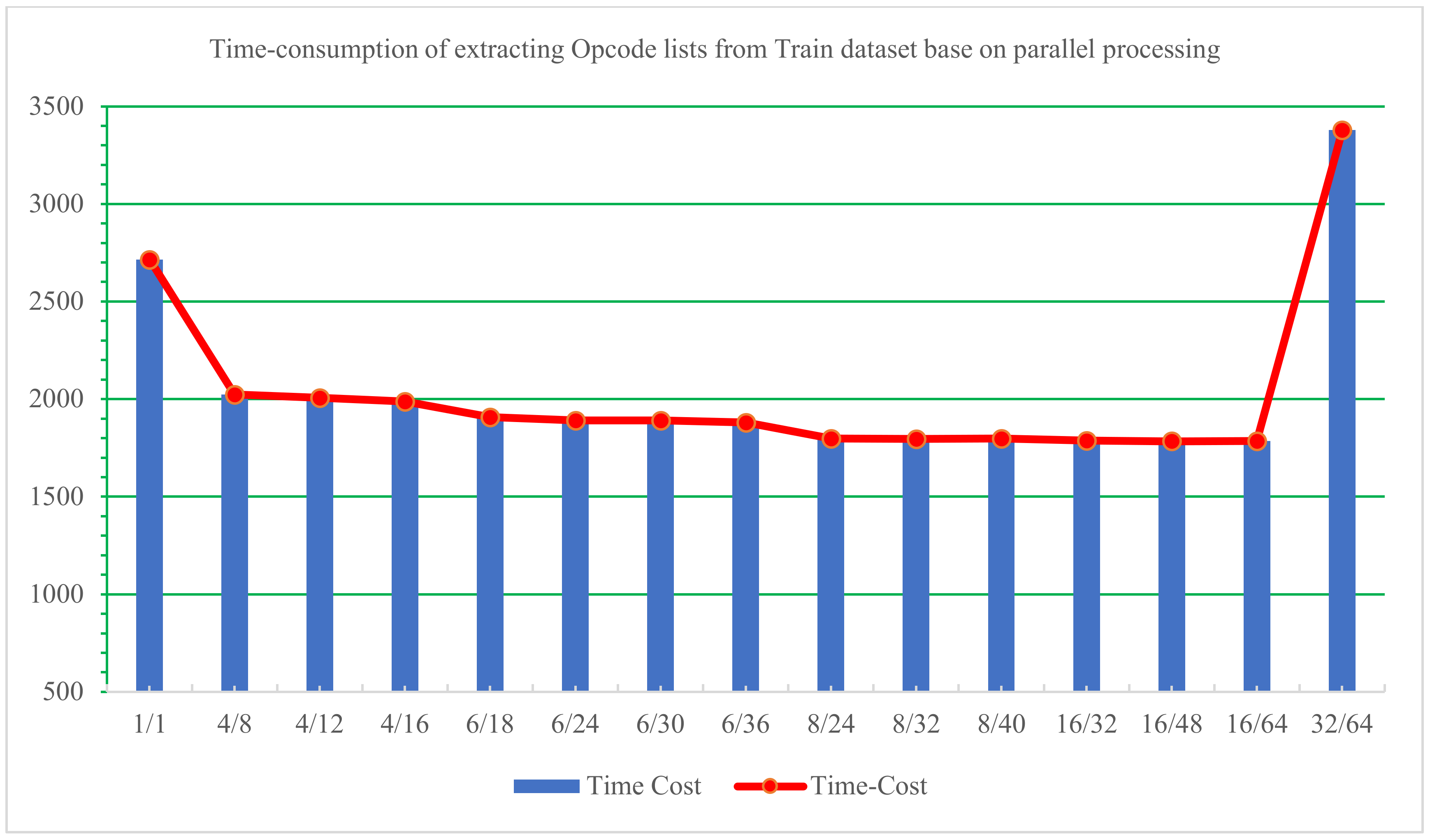

Experimental Results of Parallel Processing of Train dataset with Top-N Opcodes Extracted from Train

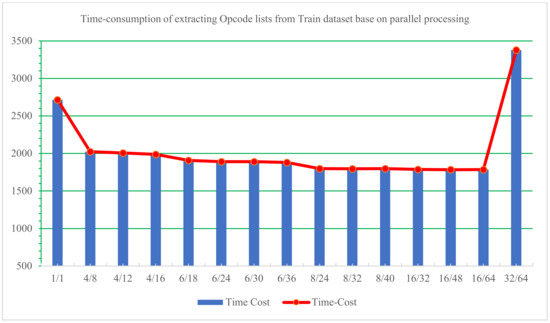

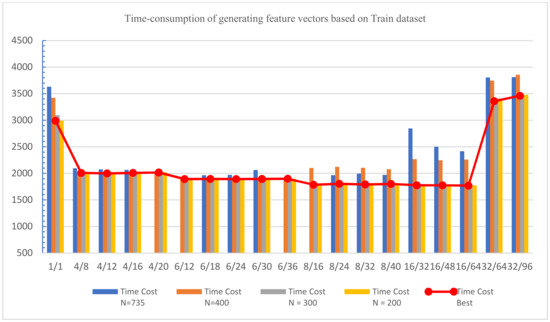

The workload will increase significantly if we extract Opcode lists directly from the Train dataset as a feature vector and then generate a feature matrix for the Train dataset. In this section, we extract feature vectors directly from the Train dataset and then carry out cross-validation. In the process of cross-validation, we extract Opcode lists from Train and construct a feature vector space for Train based on the extracted Opcode lists. Because of the large number of samples in Train dataset, these two steps are time-consuming. Therefore, we use parallel processing technology to implement these two processes, and the experimental result of parallel processing are shown in Table 7 and Table 8, respectively.

Table 7.

Experimental result of parallel extraction of Opcode lists from the Train dataset.

Table 8.

Experimental results of generating Opcode feature vectors based on parallel processing of the Train dataset.

Firstly, we utilized various parallel processing configurations to compile Opcode lists from the Train dataset. The findings are presented in Table 7, with the most effective parameter settings for parallel processing depicted in red, and another competitive setting depicted with a green background. A visual representation of the time-consuming comparison is illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Time consumption of extracting Opcode lists from the Train dataset base on parallel processing.

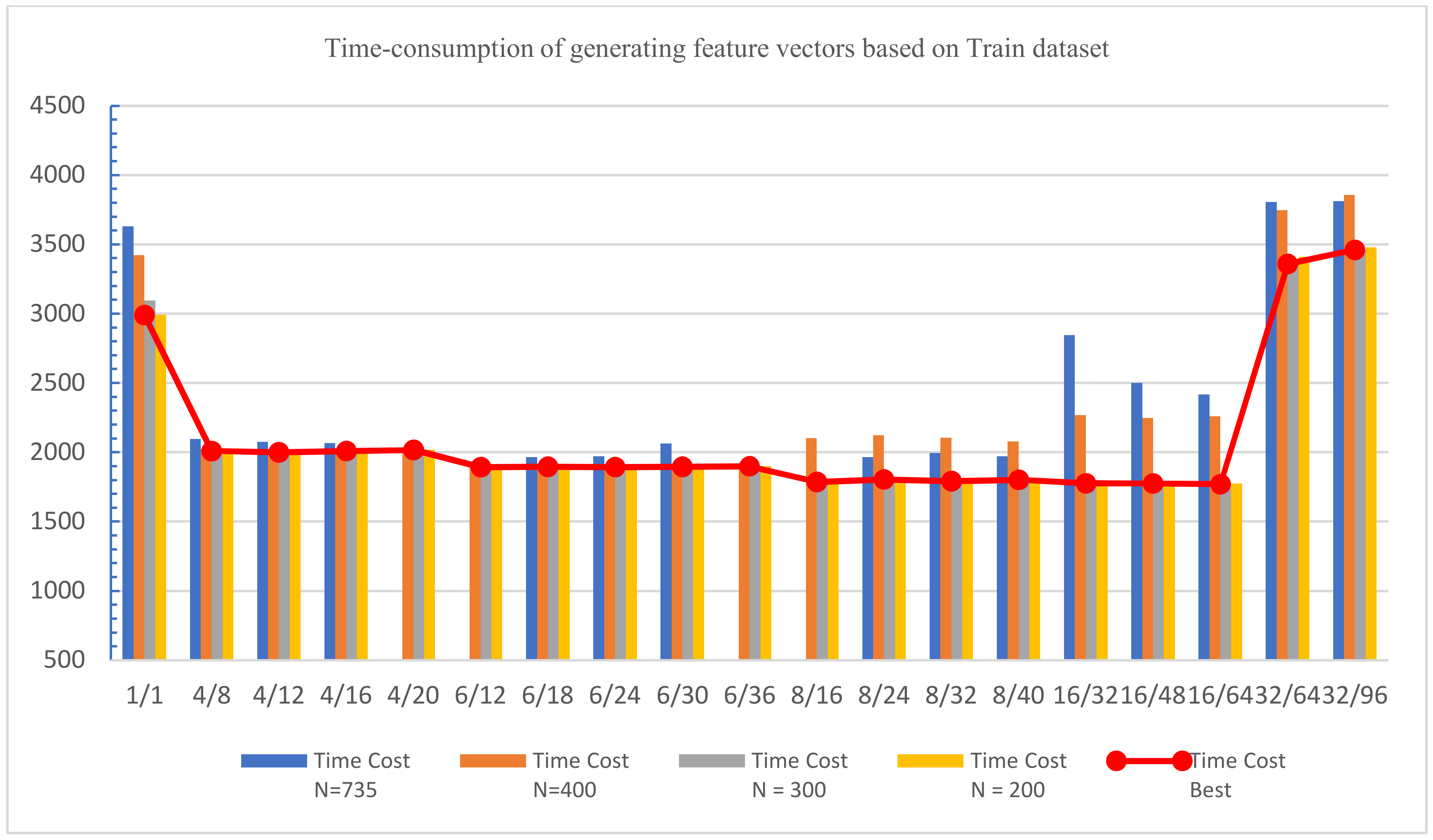

On the basis of extracting Opcode lists from the Train dataset, the experimental results of generating feature vectors of the Train dataset based on parallel processing are shown in Table 8, with the most effective parameter settings depicted in red for each different N. The visual display of comparison of time consumption is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Time consumption of generating feature vectors based on the Train dataset.

Comparative Analysis of Overhead between Parallel Process and Serial Process

From the above experimental results of serial processing and parallel processing, we can draw the following conclusions:

- (1)

- Parallel processing can effectively ameliorate processing efficiency

The serial processing procedures based on Train and Subtrain datasets include “extracting the feature vector from dataset → generating feature matrix for the training dataset → training classifier → practical classification”. The two stages of “extracting the feature vector from dataset” and “generating feature matrix for the training dataset” are time-consuming in analyzing a massive sample set, and the application of parallel processing technology can effectively reduce the processing time.

As mentioned above, the time required to complete feature extraction and feature vector generation (Top-N = 200) based on the Subtrain subset with serial processing is 3.86 + 2991.99 = 2995.85 (s). In contrast, the optimal time consumption to complete the above process with parallel processing is 3.86 + 1786.38 = 1790.24 (s), which takes only 59.76% of the original one.

If feature extraction is based on the Train dataset, the time required to complete feature extraction and feature vector generation (Top-N = 200) is 2714.30 + 2992.25 = 5706.55 (s) with serial processing. By contrast, the optimal time consumption to complete the above process is 1784.62 + 1776.38 = 3561 (s) with parallel processing, which takes 62.4% of the original one. The parallel processing achieved promising results.

- (2)

- Choosing the best parallel processing setting based on computing resource condition

Computing the resource platform has a fundamental impact on the parallel processing settings. As shown in the table, because our personal workstation platform has eight cores and the workload of analyzing a single malware sample is not large, the parallel processing effect is usually the best when generating 16 processes. That is to say, two processes are allocated to each core for the process, which can maximize the advantage of hardware resources. In addition, considering the allocation of computing resources on eight cores, we should not allocate too many samples to each process in parallel processing. We should ensure that each process is not overloaded to maximize the performance of each process.

5.2.3. Comparison with Similar Studies

To assess the performance of MalSEF, we compare it with related studies in terms of classification accuracy and time efficiency in this section. Since we utilize the dataset released by Microsoft in Kaggle, we select similar studies utilizing the same dataset for comparison. The four baseline models in Table 9 are classic methods that utilize the Kaggle dataset and hold significant influence, making them ideal candidates for comparison with MalSEF. The outcomes of the comparison are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Comparison with analogous approaches.

In comparison to similar studies, MalSEF offers the following benefits:

- (1)

- MalSEF strikes an optimal balance between the feature space and classification accuracy while sampling the feature vectors. When only 300 features are needed, MalSEF can achieve an accuracy of 98.53%. In contrast, the Ahmadi Mansour method [28] employed 1804 features, and the Hu Xin et al. method [29] required 2000 features, both more than six times the number of features in MalSEF. Their accuracy was only marginally higher than MalSEF by no more than 1.30%. Meanwhile, the time cost of MalSEF is significantly lower than other comparable methods. Although the classification accuracy of MalSEF may be slightly lower than the above-mentioned research, it still meets the requirements. Furthermore, when compared to other similar studies, MalSEF’s feature vector is the most succinct and readily available, achieving promising classification results while minimizing the complexity of feature extraction.

- (2)

- MalSEF really realized the parallel analysis of massive malware, which can effectively reduce the analysis time. Compared with the serial processing, the time efficiency is improved by 37.60%. Compared with similar research, the handing time required by MalSEF is the shortest. There may be concerns over whether the baselines could achieve better time efficiency if they use a smaller feature set. The aforementioned comparison of models is conducted under the terms of their respective required feature size. When only 300 features are used, MalSEF can achieve ideal detection results. However, if the size of the features in the baseline modes decreases, it is not confirmed whether their accuracy can remain. This raises a promising question for future research. It can also be observed that the time reduction is not especially significant when the feature size is decreased. This is because the dataset is not particularly large, and as the size of the dataset increases, the time efficiency of MalSEF will become more apparent.

- (3)

- The performance of the hardware platform required by MalSEF is moderate, so ordinary researchers can earn the opportunity. As a consequence, it can be generalized in the field of popular network security and has good applicability.

- (4)

- As for the similarities among variants of malware, MalSEF provides and verifies semantic explanations by extracting and mining Opcode information from malware samples, which compensates for the lack of semantic explanations in deep learning-based malware classification.

6. Conclusions

Considering the widespread use of metamorphic techniques by malware to evade detection, we conducted a comparative analysis of the similarities between malware variants. We found that variants are reproduced in the form of filling old wine in a new bottle actually, and there are manifest similarities between variants. To enhance the efficiency of malware analysis, accurately classifying these variants into their families is of theoretical and practical value. To achieve this goal, we proposed a new malware classification framework called MalSEF. MalSEF adopts a lightweight feature engineering framework by extracting a small part of the samples from the larger dataset to construct a sampled subset. Based on the sampled subset, it generates feature vectors to represent the original samples dataset, and then generates lightweight feature matrices, thereby reducing the workload of generating feature matrices from a large number of samples. Based on the above theory, our method uses multi-core parallel processing to analyze malware, thus making full use of the computing resources of the modern personal PC. Compared with the traditional serial processing, the time consumption is decreased and the analysis efficiency is promoted significantly. The key advantage of this paper is that MalSEF provides a practical and effective approach for analyzing and processing vast amounts of malware on personal computers. Going forward, we aim to explore the following areas: (1) Since cloud computing platforms are extensively utilized in the realm of network security, we can leverage these resources to conduct extensive parallel processing [38]; (2) utilizing Opcode to depict malware’s features is a practical approach. By doing so, we can conduct a multi-dimensional malware analysis and utilize various features for a more comprehensive portrayal of malware [39]. (3) With the increasing frequency of APT attacks and the large-scale malware outbreaks in APT, how to apply parallel processing technology to detect APT attacks and take timely response measures is also a valuable research direction in the future [40,41].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H.; Methodology, J.L.; Software, W.H.; Validation, J.L.; Investigation, Q.Z.; Data curation, Y.Z.; Writing—original draft, W.H.; Writing—review & editing, J.L. and Q.Z.; Supervision, J.X.; Project administration, J.X.; Funding acquisition, J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62172042), the National Key Research & Development Program of China (2020YFB1712104), and the Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Projects of Shandong Province (2020CXGC010116).

Data Availability Statement

The data used to validate the outcomes of this investigation can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no potential conflict of interest in the submission of this manuscript, and all authors have approved its publication.

References

- Rezaei, T.; Manavi, F.; Hamzeh, A. A PE header-based method for malware detection using clustering and deep embedding techniques. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 60, 102876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darem, A.; Abawajy, J.; Makkar, A.; Alhashmi, A.; Alanazi, S. Visualization and deep-learning-based malware variant detection using OpCode-level features. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 125, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malware. Available online: https://www.av-test.org/en/statistics/malware/ (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Singh, J.; Singh, J. A survey on machine learning-based malware detection in executable files. J. Syst. Archit. 2021, 112, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botacin, M.; Ceschin, F.; Sun, R.; Oliveira, D.; Grégio, A. Challenges and pitfalls in malware research. Comput. Secur. 2021, 106, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Kong, Z.; Mao, L. MalDAE: Detecting and explaining malware based on correlation and fusion of static and dynamic characteristics. Comput. Secur. 2019, 83, 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.; Brezo, F.; Ugarte-Pedrero, X.; Bringas, P.G. Opcode sequences as representation of executables for data-mining-based unknown malware detection. Inf. Sci. 2013, 231, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, C.W.; Chen, S.W.; Ban, T.; Kuo, S.Y. Machine learning framework to analyze IoT malware using elf and opcode features. Digit. Threat. Res. Pract. 2020, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.T.; Sani, N.F.M.; Abdullah, M.T.; Hamid, N.A.W.A. Structural features with nonnegative matrix factorization for metamorphic malware detection. Comput. Secur. 2021, 104, 102216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, S.; Yu, X. Towards Evaluating the Robustness of Adversarial Attacks Against Image Scaling Transformation. Chin. J. Electron. 2023, 32, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Li, Y. Backdoor attacks on image classification models in deep neural networks. Chin. J. Electron. 2022, 31, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Kuang, X.; Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Tan, Y.A. Detecting adversarial examples via prediction difference for deep neural networks. Inf. Sci. 2019, 501, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, E.M.; Rozsa, A.; Günther, M.; Boult, T.E. A survey of stealth malware attacks, mitigation measures, and steps toward autonomous open world solutions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 19, 1145–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge, Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/c/malware-classification (accessed on 27 October 2022).

- Radkani, E.; Hashemi, S.; Keshavarz-Haddad, A.; Amir Haeri, M. An entropy-based distance measure for analyzing and detecting metamorphic malware. Appl. Intell. 2018, 48, 1536–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagemann, C.; Sultana, S.; Chen, L.; Lee, W. Barnum: Detecting document malware via control flow anomalies in hardware traces. In Proceedings of the Information Security: 22nd International Conference, ISC 2019, New York City, NY, USA, 16–18 September 2019; Proceedings 22. Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 341–359. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Li, T.; Adjeroh, D.; Iyengar, S.S. A survey on malware detection using data mining techniques. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2017, 50, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Ye, Y.; Chen, L. Malicious sequential pattern mining for automatic malware detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 52, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnap, P.; French, R.; Turner, F.; Jones, K. Malware classification using self organising feature maps and machine activity data. Comput. Secur. 2018, 73, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.E.; DeCastro-Garcia, N. Optimal feature configuration for dynamic malware detection. Comput. Secur. 2021, 105, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Kong, Z. MalInsight: A systematic profiling based malware detection framework. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 125, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Manzanares, A.; Bahsi, H.; Nõmm, S. Kronodroid: Time-based hybrid-featured dataset for effective android malware detection and characterization. Comput. Secur. 2021, 110, 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Xie, Z.Q.; Yang, J. A load balance oriented cost efficient scheduling method for parallel tasks. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 81, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilovich, D.; Radovitzky, R.; Dvorkin, E. A parallel staggered hydraulic fracture simulator incorporating fluid lag. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 384, 114003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Li, P.; Gupta, S.M. A genetic simulated annealing algorithm for parallel partial disassembly line balancing problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 107, 107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.; Oberheide, J.; Andersen, J.; Mao, Z.M.; Jahanian, F.; Nazario, J. Automated classification and analysis of internet malware. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Intrusion Detection: 10th International Symposium, RAID 2007, Gold Goast, Australia, 5–7 September 2007; Proceedings 10. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 178–197. [Google Scholar]

- Nataraj, L.; Yegneswaran, V.; Porras, P.; Zhang, J. A comparative assessment of malware classification using binary texture analysis and dynamic analysis. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM Workshop on Security and Artificial Intelligence, Chicago, IL, USA, 21 October 2011; pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, M.; Ulyanov, D.; Semenov, S.; Trofimov, M.; Giacinto, G. Novel feature extraction, selection and fusion for effective malware family classification. In Proceedings of the Sixth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, New Orleans, LA, USA, 9–11 March 2016; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Jang, J.; Wang, T.; Ashraf, Z.; Stoecklin, M.P.; Kirat, D. Scalable malware classification with multifaceted content features and threat intelligence. IBM J. Res. Dev. 2016, 60, 6:1–6:11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Kwak, J. Effective and reliable malware group classification for a massive malware environment. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2016, 12, 4601847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raff, E.; Nicholas, C. Malware classification and class imbalance via stochastic hashed lzjd. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security, Dallas, TX, USA, 3 November 2017; pp. 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Q.; Boydell, O.; Mac Namee, B.; Scanlon, M. Deep learning at the shallow end: Malware classification for non-domain experts. Digit. Investig. 2018, 26, S118–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazato, J.; Song, J.; Eto, M.; Inoue, D.; Nakao, K. A novel malware clustering method using frequency of function call traces in parallel threads. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2011, 94, 2150–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, S.; Anitha, R.; Sirisha, P. Malware detection by pruning of parallel ensembles using harmony search. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2013, 34, 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Su, X.; Li, W. Mlifdect: Android malware detection based on parallel machine learning and information fusion. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2017, 2017, 6451260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Hu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhuo, G. A novel statistical technique for intrusion detection systems. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 79, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusitta, A.; Li, M.Q.; Fung, B.C. Malware classification and composition analysis: A survey of recent developments. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 59, 102828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Verma, I.; Gupta, S. KVMInspector: KVM Based introspection approach to detect malware in cloud environment. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2020, 51, 102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Tang, Z.; Wang, J. A novel few-shot malware classification approach for unknown family recognition with multi-prototype modeling. Comput. Secur. 2021, 106, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Gao, X. APTMalInsight: Identify and cognize APT malware based on system call information and ontology knowledge framework. Inf. Sci. 2021, 546, 633–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liras, L.F.M.; de Soto, A.R.; Prada, M.A. Feature analysis for data-driven APT-related malware discrimination. Comput. Secur. 2021, 104, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).