Abstract

The objective of face aging is to generate facial images that present the effects of aging. The existing one-hot encoding method for aging and/or rejuvenation patterns overlooks the personalized patterns for different genders and races, causing errors such as a male beard appearing on an aged female face. A gender-preserving face aging model is proposed to address these issues, termed GFAM. GFAM employs a generative adversarial network and includes several subnetworks that simulate the aging process between two adjacent age groups to learn specific aging effects. Specifically, the proposed model introduces a gender classifier and gender loss function that uses gender information as a self-guiding mechanism for maintaining gender attributes. To maintain the identity information of synthetic faces, the proposed model also introduces an identity-preserving module. Additionally, age balance loss is used to mitigate the impact of imbalanced age distribution and enhance the accuracy of aging predictions. Moreover, we construct a dataset with balanced age distribution for the task of face age progression, referred to as Age_FR. This dataset is expected to facilitate current research efforts. Ablation studies have been conducted to extensively evaluate the performance improvements achieved by our method. We obtained relative improvements of 3.75% higher than the model without the gender preserving module. The experimental results provide evidence of the effectiveness of the proposed method, both through qualitative and quantitative analyses. Notably, the mean face verification accuracy for the age-progressed groups (0–20, 31–40, 41–50, and 51–60) was found to be 100%, 99.83%, 99.79%, and 99.11%, respectively, highlighting the robustness of our approach across various age ranges.

1. Introduction

The task of face aging involves generating natural-looking aged versions of face images while preserving the subject’s identity and distinctive facial features. Face aging has practical applications in fields such as locating missing children, kinship verification, and identifying fugitives, among others, which help to create a safe and secure society. Despite its practical value, face aging remains challenging owing to the need for adequate labeled age data on the same subject. Face aging has made remarkable progress in recent years, with numerous methods proposed. These methods produce more realistic aging effects and fewer ghosting artifacts compared to traditional solutions. The resultant methods can be broadly categorized into two groups: conditional generative adversarial network (cGAN)-based and generative adversarial network (GAN)-based methods. Although both cGAN-based and GAN-based methods have been used for face aging, there are notable differences between the two approaches. While cGAN-based methods have greater flexibility, as noted in references [1,2,3,4,5], GAN-based methods, as reported in references [6,7,8], tend to yield superior results in this field.

Generating accurate and high-quality aged faces is an inherently challenging task. Although several methods have been proposed for face aging, meeting three critical requirements for face aging simultaneously, namely aging accuracy, identity preservation, and gender preservation, remains a difficult problem. The faces generated using current methods do not satisfy all three requirements simultaneously. Owing to the inherent complexity of face aging, these methods may not guarantee the aging smoothness of the synthesized faces, particularly when the original face images are of young children. In such cases, age progression beyond a few years may not be practically achievable, which can affect the aging accuracy of the generated faces. Additionally, there could be situations where the aged appearance of a face appears younger than expected. Consequently, to address such variations in aging, the algorithm is trained to learn group-level patterns of aging and rejuvenation for each specific age group condition, such as the tendency for individuals to develop beards as they age. However, this approach has two drawbacks. Firstly, the use of one-hot encoding to represent age group-level aging and/or rejuvenation patterns disregards the personalized patterns of aging that are specific to an individual’s identity, particularly with regard to gender and race. Secondly, there is the issue of inaccurate depictions of gender-specific features, such as the appearance of a beard on an aged female face, which is especially true when the original face image is of a young child. For instance, toddlers often lack obvious gender characteristics, which can lead to inaccurate sex prediction by the learning model and, hence, inaccurate simulation.

For this reason, one of the primary goals is to achieve high natural and gender preservation in face aging. Although the progressive face aging with generative adversarial network (PFA-GAN) [7] is a skilled progressive facial aging model, it has limitations in capturing gender information during the aging process as it primarily focuses on the general aging pattern. Consequently, some of the generated samples may not retain the original gender information. Our proposed solution is the gender-preserving face aging model (GFAM), a novel deep learning model that incorporates gender- and identity-preserving components. Extending the PFA-GAN architecture, GFAM is specifically designed to tackle the challenges related to gender and identity preservation. Firstly, the image is input to the encoder to obtain the personality characteristics. Then, the personality traits are associated with aging through the decoder. Finally, the identity-preserving module utilizes a method of decomposition to extract the identity-specific features. These features are then employed to maintain the identification details of the synthesized faces. The addition of a gender classifier and gender loss, which utilizes gender information as a guiding mechanism, helps to simulate aging effects vividly while maintaining gender information to a finer extent. To improve the accuracy of age prediction models, we introduce a novel age balance loss, which is designed to address the issue of imbalanced age distribution in the training dataset.

Moreover, we construct a new dataset named Age_FR, which has a balanced age distribution to facilitate ongoing and future studies on face age progression. Age_FR contains 181,824 face images of 9719 individuals annotated with identity, gender, and age information. The effectiveness of the proposed method has been demonstrated through extensive experiments conducted on the Age_FR dataset.

2. Related Works

2.1. Face Aging

Face-aging methods are classified into three groups, namely physical model-based, prototype-based, and deep learning-based methods.

Physical model-based methods [9,10] utilize complex parametric models to simulate facial changes over time. The primary issue with physical model-based methods is their computational inefficiency and limited generalizability owing to the effects of mechanical aging.

The prototype-based method [11] for face aging categorizes faces into different groups based on their age range and computes an average face for each group to generate prototypes that can be used to age test faces. However, this approach is limited as it may overlook personalized information, as the age patterns are determined by the average face of each group.

Recently, face-aging techniques using deep learning have gained popularity. Wang et al. [12] used a recurrent neural network (RNN) to express smooth transformation patterns between different ages. However, it requires a large dataset consisting of face pairs from the same subject over a long period as a training dataset. To tackle this challenge, numerous contemporary studies have employed unpaired facial images for training face-aging models through the use of GANs [13] or cGANs [14]. The visual quality of facial aging can be significantly improved when the model is based on the cGAN. The cGAN-based methods [1,2,3,4,5] combine the concepts of GAN and autoencoders to explore different age maps using one or two models conditional on the target age group. For example, Zhang et al. [1] introduced a conditional adversarial autoencoder framework that projects faces onto a latent subspace and decodes them to produce aged faces, achieving simultaneous aging progression and regression.

However, the models may lose identity-related information during the age transformation process. To address this, the identity preservation network has been proposed to ensure that the face identity remains unaltered. For instance, Wang et al. [2] presented an identity-preserving IPCGAN that uses a pre-trained class-based model on perceptual loss to preserve the identity information. Yang et al. [6] proposed a novel pyramid structure discriminator that takes in high-level age-specific features to provide better supervision for the smoothness of aging and improve the overall performance of the model from different perspectives.

Sometimes, the aging results can be blurry, possibly due to the manifold being constrained as a simple prior distribution. The image quality can also be damaged during the process of projection. Li et al. [15] used a global generator along with three local generators for the forehead, eyes, and mouth separately to enhance the aging details. In addition, Li et al. [16] incorporated a wavelet transform into their age synthesis model to better capture texture details. Similarly, A3GAN [8] also utilized wavelet information in the discriminator in a multiscale manner.

Yao et al. [17] presented a high-resolution face-aging editing model to generate realistic and high-resolution images. This model includes a reconstruction loss that helps to preserve the identity information during the age transformation process. The modulation network is used to adjust the latent vectors and improve the quality of the generated images, resulting in more realistic outputs. By using this approach, the discriminator can focus on its main role of distinguishing between real and fake images, which can further improve the quality of the generated images. However, despite these improvements, there may still be noticeable artifacts in the final results. Similarly, Despois et al. [3] introduced a method to improve the preservation of texture details during the face-aging process by incorporating aging maps through spatially adaptive denormalization blocks [18]. This approach adjusts the normalization of features based on age maps, resulting in more realistic and high-resolution face images, particularly in areas where aging effects are more pronounced, such as wrinkles and fine lines. S2GAN [19] utilizes personalized aging-based encoded transforms to obtain age-specific representations of the input faces during decoding. Meanwhile, Li et al. [5] introduced a spatial attention mechanism to the dual conditional GAN structure [4], which improves the preservation of identity information while minimizing ghost artifacts in the generated images.

Training each unit of the face age progression (FAP) framework independently results in artifacts owing to the accumulation of errors as they are passed through the units. Huang et al. [7] put forward a recursive FAP framework based on GAN to address the issue of artifacts. The proposed approach trains the entire chain of transformers end-to-end to mitigate these artifacts. Although the method maintains good preservation of identity and age information, it has limited effects on gender information preservation. Makhmudkhujaev et al. [20] proposed a customized self-guidance approach that alters facial features for different age groups. Their method utilized a single generative and discriminative model, which was trained successfully in an unpaired manner. Liu et al. [21] proposed a framework that learns to separate age-related features from identity-related features in face images to generate aging faces while preserving identity. Huang et al. [22] proposed a multi-task learning framework that combines age-invariant face recognition with face age synthesis and utilized these high-quality synthesized faces to further boost age-invariant face recognition. Huang et al. [23] proposed a framework that integrates the advantages of a flow-based method model and GANs. Especially, Zhao et al. [24] proposed a new disentangled learning strategy for children’s face prediction that may help settle the missing child identification problem. Table 1 shows the major deep learning-based face aging methods.

Table 1.

Major deep learning-based face aging methods.

2.2. Image-to-Image Translation

Face progression and rejuvenation can be viewed as an image-to-image translation task, for example, translating images from young to old age domains and vice-versa. The effectiveness of GAN in producing visually attractive images has greatly enhanced the translation of images between two domains, whether they are paired (Pix2Pix) [25] or unpaired (CycleGAN) [26] training data. Multi-domain transfer algorithms such as StarGAN [27] and STGAN [28] can modify various facial attributes, but they are designed assuming that these attributes are different and easily distinguishable. These methods are not well-suited for face aging translation because the appearance of the face at a specific age is closely related to other facial attributes, such as gender and ethnicity, which can unintentionally be altered during the translation. Moreover, methods based on multi-domain transfer have difficulty in modeling age transition-related conformational distortions, such as changes in the head shape.

Or-El et al. [29] presented a method for synthesizing lifespan age transformations (LATS) based on StyleGAN2 [30]; the decoder in this approach performs modulated convolutions on the identity features while injecting the target age latent vector learned from the mapping network. The architecture allows for translations between highly correlated domains and obtains a continuously traversable age latent space while preserving the identity and image quality. Additionally, LATS emphasizes face synthesis without background information to reduce the unexpected artifacts caused by the background.

However, these methods have limited success in modeling the nonlinear transformations of facial shape and texture for older individuals. Therefore, He et al. [31] proposed a novel model to extract the key facial characteristics, including shape, texture, and identity, to enable efficient modeling of age transformations. The present work prioritizes the acquisition of distinct gender characteristics and personalization for face aging. To address the challenge of preserving gender characteristics during aging, the model incorporates a gender-preserving component that ensures the generated faces retain gender-specific features such as the jawline and cheekbones. Additionally, the model includes an identity-preserving component that aims to maintain the unique identity of the individual throughout the aging process.

3. Gender-Preserving Face-Aging Model

3.1. Overview

The main study objective is to robustly transform the face age while maximally retaining gender information in the generated face images. We develop a long-term aging model for natural facial features and gender preservation in the faces by combining several identical short-term aging models, each of which aims to learn the differences between two adjacent age groups. This approach provides finer control over the aging process, allowing us to better identify and address specific challenges at each stage. In the following section, we provide a detailed description of our network architectures, which are critical to the successful implementation of our proposed approach.

Suppose we have a set of face images , and given an image , our objective is to train sub-generators to generate multiple faces of several fixed age groups corresponding to the identity in . To achieve this, we utilize the age-invariant feature extraction network (AFEN) [32] to maintain the identity information during the generation process. By incorporating an age balance loss into the model training process, the impact of age imbalance is effectively mitigated. In addition, a gender classifier is introduced to utilize gender information as self-guiding data to preserve the gender attributes of the generated faces.

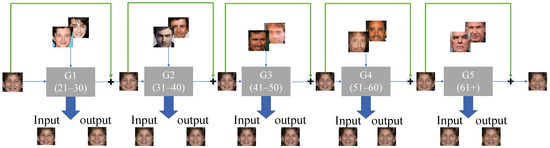

Considering the dataset’s wide range of ages, the interval is divided into six groups: up to 20, 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, and above 61 years. Inspired by the methodology presented in previous work [12], which employed an RNN to effectively capture the transformation patterns across various age groups, we adopt five sub-generators to model the transition patterns between adjacent age groups. By applying a skip connection in the sub-network, the network allows easy control over the aging flow, as shown in Figure 1. Assuming the age group depends on the age group , six age groups can be formulated as shown in Equation (1):

where is the input image and is the -th sub-generator.

Figure 1.

Architecture exploiting several GANs to model the aging patterns.

Finally, given any young face from the source age group, we can generate the corresponding aged face from the target age group through the aging network.

3.2. GAN-Based Architecture

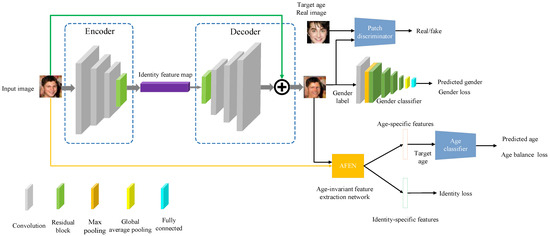

The GAN-based framework is composed of multiple sub-generators, and each of them is made up of four main components: generator, discriminator, gender classifier, and identity-preserving model. These sub-generators are responsible for learning the aging patterns between two neighboring age groups. To achieve this, each sub-generator undergoes extensive training using a combination of several loss functions, including adversarial loss, identity loss, age balance loss, and gender loss. The ultimate goal of the framework is to generate realistic and high-quality aged faces while preserving the identity information of the input face. The complete framework and optimization process are illustrated in Figure 2, and the following subsections provide a detailed description of the proposed face aging framework.

Figure 2.

The sub-generator framework is devised to facilitate the transformation of a young face into an aged one, which falls into the next age group.

The generator uses convolutional layers, with a residual blocks-based generator structure, to learn the age transformation. The input faces from the source age group are denoted by . The generator output from to the target age group is represented as . To enforce the generator to produce samples toward the decision boundary, the least-squares GANs [33] utilize the least-squares loss function instead of the traditional GAN’s negative log-likelihood loss function. The adversarial loss is defined as follows:

where denotes the source age group and refers to the input image; denotes the target age group and represents the generated image. is the discriminator, which is used to distinguish between the generated image and a real image. represents the expectation operation.

The PatchDiscriminator [25] is adopted as the discriminator in this work. Each branch performs binary classification to determine the validity of the image as real or fake with respect to its corresponding age domain. The synthesized face in the target age group should not be classified as a fake sample by the discriminator . However, the discriminator lacks the ability to determine whether the learned aging effect is genuine or not based on gender. Therefore, a gender classifier is added to preserve the gender attributes in the aged face.

3.3. Gender Classifier

The dataset may contain images with gender imbalances within the age groups. To address this issue, a gender classifier is used to preserve the gender attributes by considering the target gender as a condition and utilizing the gender label as self-guiding information. Based on the cross-age celebrity dataset (CACD) [34], 79,143 individuals are initially labeled as female and 79,057 individuals are labeled as male. The model was trained using an 80% and 20% split for training and testing, respectively. Subsequently, the corresponding gender labels are created for the training dataset. The gender classifier is then trained using the gender label of the input face. The ResNet18 framework [35] is adopted as the base network, as illustrated in Figure 2. The gender loss is defined by the softmax loss to obtain an adequately pre-trained gender classifier model. Our gender classifier achieved an average accuracy of 90.42%.

3.4. Identity-Preserving Module

Preserving the identity information of the synthesized faces is crucial. However, due to the adversarial loss, the generator can produce samples that adhere to the target data distribution, resulting in generated samples resembling any person in the targeted age group. Figure 2 illustrates the implementation of the proposed decomposition method [19] to extract age- and identity-specific features. This model decomposes all features extracted from a facial image into two separate components using the spherical coordinate system. The identity-specific features are then employed to maintain the identity information of the generated faces. The identity loss is defined as follows:

where is the number of training samples. refers to the input image, and represents the generated image. represents features extracted from a specific layer of a pre-trained neural network.

To further ensure that the generated faces fall into the target age group , the age-specific features are leveraged, and an age classifier is trained to identify the correct age of the generated image. Most of the training images used are from adults aged 20–60, while some are from children under 10 years old and senior adults over 60 years old. Therefore, the models trained using such imbalanced data may perform poorly on underrepresented groups, such as those aged above 60 years. The balanced mean-squared error (MSE) loss [36] is utilized in the model instead of the traditional MSE loss to account for the label imbalances in a statistical manner, thereby mitigating the influence of imbalanced label distribution on the MSE. The balanced MSE calculates the discrepancy between the predicted and target ages. The batch-based Monte Carlo implementation of the balanced MSE loss is employed, where all labels in a training batch are treated as random samples and require no label preprocessing beforehand. For labels in a training batch, , the loss can be rewritten like the softmax function to represent the loss between the estimated age and the target age :

where is a one-dimensional hyperparameter that can be optionally learned during training.

3.5. Optimization

As illustrated in Figure 2, the complete loss function for achieving face aging goals incorporates four key elements: (1) adversarial loss that strives to generate aged facial images of superior quality that cannot be differentiated from real ones; (2) identity loss that seeks to preserve the same identity; (3) age balance loss that is expected to enhance the accuracy of aging while also serving as a potential solution to the issue of age imbalance within datasets; (4) gender loss that helps to improve aging accuracy.

4. Experiments

We conducted a new large-scale cross-age face dataset based on four published datasets for photorealistic cross-age face synthesis research. Table 2 lists the breakdown of the four published datasets and the new dataset into the different age categories and showcases individuals from diverse age groups. The dataset comprises 182,004 face images from 9719 subjects annotated with identity, gender, and age labels. Compared to the previous CACD dataset, our dataset has a better balance of data, with large age gaps from 0 to 116 years, particularly in terms of images featuring subjects under 10 years old and over 60 years old. This is essential for forcing the model to generate faces that exhibit desirable rejuvenation and/or aging effects in these age groups. Images are taken in real scenes (in the wild) and include not only celebrities but also ordinary people, increasing the diversity of the data.

Table 2.

Statistics on the age range distribution for four available cross-age face datasets (CACD, AdienceFaces, CASIA-WebFace, and UTKFaces) and Age_FR. N/A means ‘Not Applicable’.

4.1. Data Collection and Annotation

The AdienceFaces benchmark dataset [37] is designed for gender and age classification with diverse gender, age, and ethnic backgrounds. The images were sourced from multiple platforms, including the Internet and social media. The dataset comprises approximately 16K images of 2284 subjects captured in the wild and labeled into eight ordinal groups of age ranges: babies (0–2), infants (4–6), children (8–13), teenagers (15–20), young adults (25–32), adults (38–45), middle-aged (48–53), and seniors (60 and above years). The dataset’s annotations for age and gender information for every image make it an excellent resource for identifying facial attributes such as age and gender from face images.

The UTKFace dataset [1] is a comprehensive collection of 23,699 facial images that represent a diverse population of individuals with ages ranging from 0 to 116 years. These images were sourced from publicly available platforms and feature people from various parts of the world. Notably, the dataset exhibits substantial diversity in terms of pose, facial expression, illumination, occlusion, and resolution. Additionally, it is annotated with information on ethnicity, gender, and age, which makes it a valuable resource for applications in computer vision, such as gender classification, age estimation, and face recognition.

The CASIA-WebFace dataset [38] has a collection of 10,575 individuals and 494,414 face images. Each person in the dataset is represented by at least two facial images, all captured at 250 × 250 resolution with varying lighting, poses, and expressions. To ensure that the dataset is appropriate for age-invariant face recognition tasks, we carefully reviewed and filtered out any images with unsuitable lighting, pose, expression, or occlusion by sunglasses.

The CACD dataset [34] contains 163,446 face images of 2000 celebrities which were captured under less controlled conditions. In addition to the significant differences in posture, lighting, and facial expressions (also known as PIE variations), the dataset was compiled through a Google image search, which poses a significant challenge due to the discrepancies between the person’s actual face in each image and the provided labels. The data were manually verified to obtain a precise dataset with correct identity labels, resulting in a final dataset consisting of 158,200 facial images. Since age and gender labels are required for model training, they were manually generated.

Data processing on the image was conducted as follows. (1) Data cleaning and normalization. To filter the images with borders, which can reduce the accuracy of face recognition, the input images were preprocessed and normalized. This involves cropping the borders and retaining only the facial portion. The multi-task cascaded convolutional network was utilized to detect the facial landmarks and areas and align the facial images based on the identified eye coordinates. Figure 3 shows some face images that have been aligned and normalized from the Age_FR dataset. (2) Data annotation. The dataset’s original gender and age annotations were collected and identity annotations were created manually. The Age_FR dataset contains annotations including identity, gender, and age information, which renders it well-suited for employment in tasks related to face aging. (3) Manual inspection. After annotation, the accuracy of all images and their related annotations were confirmed through manual inspection.

Figure 3.

Example images from the Age_FR dataset. The images in the top row are original images, while those in the bottom row depict images that have been aligned and normalized.

To create the Age_FR dataset, the following data selection procedure was used to maintain age balance. Firstly, images from all age groups were selected from the CACD dataset. Next, face data from UTKFace and AdieneFaces, for individuals aged between 0–20 and over 60 years old, were included in the dataset. Since CASIA-WebFace does not contain age labels, only individuals over 60 years old were included in the dataset, and their age was marked as 65. The Age_FR dataset finally contained 182,004 face images from four parts: (1) CACD, 158,000 images; (2) UTKFace, 5971 images; (3) AdieneFaces, 4105 images; (4) CASIA-WebFace, 13,928 images. The CACD dataset offers paired face data that can effectively train sub-generators ,, , and . In addition, by utilizing the samples from AdienceFaces, UTKFace, and CASIA-WebFace datasets, we can train sub-generator to capture the aging patterns beyond 60 years of age.

4.2. Implementation Details

The proposed model is initialized using the He initialization method [39] and implemented based on the PyTorch platform. All models are trained with a maximum of 40 epochs on four Nvidia Titan X Pascal GPUs with 48G memory, and the batch size is 16. The model is then optimized using the Adam optimization method [40], and the learning rate is 1.0 × 10−4. The hyperparameters in Equation (5) are empirically set as: = 100, = 5.0 × 10−4, = 0.4, and = 0.1.

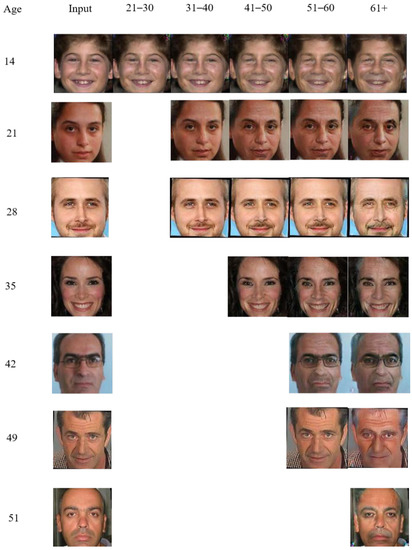

4.3. Qualitative Comparison

Figure 4 shows some sample results of face aging on images from the CACD and FGNET datasets. Although some faces appear unnatural, the results indicate that the proposed method is capable of preserving both identity and gender while generating faithful, diverse aged faces.

Figure 4.

Sample results for the proposed model on images from the CACD and FGNET datasets for face aging.

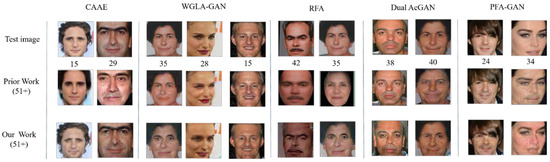

To illustrate the efficiency of the proposed GFAM, comparisons were performed with some of the latest state-of-the-art methods. As depicted in Figure 5, the proposed method demonstrated superior performance in producing aging effects on faces while maintaining identity information compared to the CAAE [1] method. Moreover, it outperformed the GAN-based WGLA-GAN [16] method in generating realistic aging details such as wrinkles and color distortion. Our approach also excelled over the RNN-based RFA [12] method in conserving the original identity information and preserving aging details. In terms of preserving details such as face shape and original skin tone, our method surpassed the cGAN-based approach of dual AcGAN [5]. Although PFA-GAN [7] performed better than our model in reducing ghosting, it is worth noting that our model preserves gender-specific information for women, such as the absence of beard growth.

Figure 5.

Performance comparisons with current methods on the CACD and FGNET datasets for face aging. The top row shows the test faces with the real age, and the middle and bottom rows show the generated faces using currently used models and the GFAM model, respectively, for the target age group (51+).

4.4. Quantitative Comparison

Identity Preservation. A face verification experiment was conducted for every synthesized face to ensure that their identity property was accurately preserved. We conducted paired comparisons between the input image and the generated faces for each individual test face (such as test versus aged face 31–40, test versus aged face 41–50, and test versus aged face 51–60). As shown in Table 3, for the CACD dataset, we performed a total of 34,432 face verification tests (8608 per age group), comparing each test face to the corresponding generated faces for the four age ranges (20–30, 31–40, 41–50, and 51–60); the mean verification accuracy for these four age-progressed groups are 100%, 99.83%, 99.79%, and 99.11%, respectively. We performed face verification on test faces and synthetic faces using a commonly used online face recognition API called Face++ [41] to check that the original identity attributes are preserved during aging. The false accept rate (FAR) and threshold were set to 10−5 and 76.5 in Face++ APIs, respectively. Our method outperformed IPCGAN owing to the identity-preserving module. The face verification results confirm that the proposed method is relatively superior at preserving the original identity information.

Table 3.

Quantitative comparisons using the face verification rate (VR) on the CACD dataset. The boldface entries represent the best values.

4.5. Ablation Study

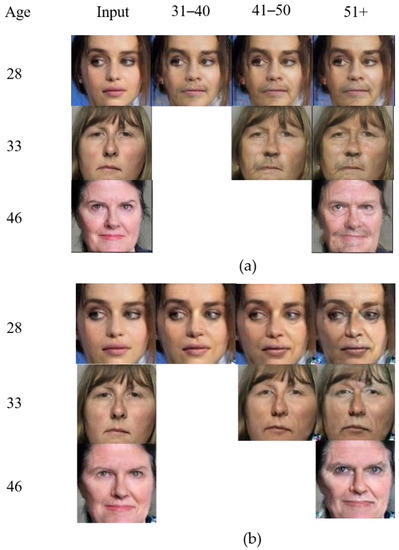

Qualitative study on the effect of the gender-preserving module. Experiments were conducted to explore the contributions of the proposed gender-preserving module. All experiments in this category were performed on images from the CACD dataset. Figure 6 displays multiple visual illustrations of facial images produced by the proposed model. The results show that when the gender classifier is not included, the generated results suffer from severe gender errors, indicating that the proposed method preserves gender information.

Figure 6.

Samples of the visual results from the ablation study using the gender preserving module. (a) Performance without gender classifier; (b) Performance with gender classifier.

Quantitative study on the effect of the gender-preserving module. Table 4 displays the gender accuracy of two models: one without the gender-preserving module and the other with the module. It was observed that our model achieved a gender accuracy of 79.69%, which is 3.75% higher than the model without the gender-preserving module. These results demonstrate that the inclusion of the gender-preserving module leads to improved gender accuracy compared to models that lack this module.

Table 4.

Gender accuracy with and without the gender-preserving module on the CACD dataset.

The effect of the identity-preserving module. By performing an ablation study on face verification, we assessed the models with and without the identity-preserving module, using the same experimental setup as in Section 4.4. Table 5 presents the results, which indicate that incorporating the identity-preserving module results in an improvement in the performance of face verification.

Table 5.

Face verification accuracy with and without the identity-preserving module on FG-NET. The bold represents the best value.

The effect of age classifier. Our study focuses on assessing the accuracy of the GFAM with and without an age classifier. We utilized a facial age estimation tool called Face++ to predict the age group of synthetic faces. The FG-NET dataset was chosen as the input image for the model because it provides a larger age range compared to the CACD dataset. The dataset consists of 1002 images of 82 individuals whose ages range from 0 to 69. The 1002 images are categorized into five age groups: 0–20, 21–31, 31–40, 41–50, and 50+. The images are fed into the GFAM, with or without an age classifier, to produce aged faces, which are grouped into four age categories: 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, and 51–60. Afterward, we compared the estimated age groups with the target age groups and calculated the percentage of faces that matched. Table 6 shows the effect of the age classification term and illustrates that incorporating an age classifier improves age classification accuracy compared to models without one.

Table 6.

Aging effects with and without an age classifier term on FG-NET. The bold represents the best value.

5. Conclusions

The proposed GFAM framework addresses the challenges associated with generating accurate and high-quality aged faces through a gender-preserving face aging synthesis approach based on the GAN. Facial aging synthesis involves three critical factors, namely aging accuracy, gender preservation, and identity preservation. We proposed a comprehensive framework to generate accurate and high-quality aged faces while preserving gender attributes and identity information. Our approach leverages multiple subnetworks that simulate the aging process from youth to old age, allowing us to capture the unique effects of aging between adjacent age groups. By effectively using a gender classifier and gender loss, our approach can maintain gender attributes during the aging synthesis process while also ensuring that the generated faces retain their original identity with the use of an identity-preserving module. To further enhance the accuracy of aging predictions, we utilized an age balance loss to address the issue of imbalanced age distribution. Furthermore, we created a dataset called Age_FR, which has a well-balanced distribution of ages, to propel the research on face age progression. We demonstrated the efficiency of the suggested approach through both quantitative and qualitative analyses in our experiments. However, currently, it is difficult for GFAM to generate detailed aging predictions for children aged 0–13 due to limited high-quality facial data for those.

To address this challenge, we plan to collect more extensive and targeted data and design a model specifically tailored to accurately predict the aging of missing children. Although this study focuses on the face aging framework, further investigations into the potential of facial rejuvenation may also be worth exploring in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and H.J.L.; methodology, S.L.; software, S.L.; validation, S.L.; formal analysis, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and H.J.L.; supervision, H.J.L.; project administration, H.J.L.; funding acquisition, H.J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a project for Joint Demand Technology R&D of Regional SMEs funded by the Korea Ministry of SMEs and Startups in 2023 (No. RS-2023-000207672).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Qi, H. Age progression/regression by conditional adversarial autoencoder. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 5810–5818. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, X.; Luo, W.; Gao, S. Face aging with identity-preserved conditional generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7939–7947. [Google Scholar]

- Despois, J.; Flament, F.; Perrot, M. AgingMapGAN (AMGAN): High-resolution controllable face aging with spatially-aware conditional GANs. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 613–628. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, L.; Liu, X.; Shen, H.T. Dual Conditional GANs for Face Aging and Rejuvenation. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018; pp. 899–905. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z. Age progression and regression with spatial attention modules. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2020, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 11378–11385. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y.; Jain, A.K. Learning face age progression: A pyramid architecture of gans. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Shan, H. PFA-GAN: Progressive face aging with generative adversarial network. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 16, 2031–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Sun, Z.; Tan, T. A 3 GAN: An attribute-aware attentive generative adversarial network for face aging. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2021, 16, 2776–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.T.; Mark, L.S.; Shaw, R.E.; Pittenger, J.B. The perception of human growth. Sci. Am. 1980, 242, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Thalmann, N.M.; Thalmann, D. A plastic-visco-elastic model for wrinkles in facial animation and skin aging. In Fundamentals of Computer Graphics: World Scientific, Proceedings of the Second Pacific Conference on Computer Graphics and Applications, Beijing, China, 26–29 August 1994; World Scientific Inc.: River Edge, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kemelmacher-Shlizerman, I.; Suwajanakorn, S.; Seitz, S.M. Illumination-aware age progression. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 3334–3341. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yan, Y.; Cui, Z.; Feng, J.; Yan, S.; Sebe, N. Recurrent face aging with hierarchical autoregressive memory. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 41, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional generative adversarial nets. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1411.1784. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Hu, Y.; Li, Q.; He, R.; Sun, Z. Global and local consistent age generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Beijing, China, 20–24 August 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1073–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Hu, Y.; He, R.; Sun, Z. Global and local consistent wavelet-domain age synthesis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 14, 2943–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Puy, G.; Newson, A.; Gousseau, Y.; Hellier, P. High resolution face age editing. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 8624–8631. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.; Liu, M.-Y.; Wang, T.-C.; Zhu, J.-Y. Semantic image synthesis with spatially-adaptive normalization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2337–2346. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Kan, M.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. S2gan: Share aging factors across ages and share aging trends among individuals. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9440–9449. [Google Scholar]

- Makhmudkhujaev, F.; Hong, S.; Park, I.K. Re-Aging GAN: Toward Personalized Face Age Transformation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3908–3917. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Wan, L.; Yu, H. Multimodal face aging framework via learning disentangled representation. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2022, 83, 103452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Shan, H. When Age-Invariant Face Recognition Meets Face Age Synthesis: A Multi-Task Learning Framework and A New Benchmark. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 7917–7932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Shan, H. AgeFlow: Conditional age progression and regression with normalizing flows. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.07239. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Po, L.; Wang, X.; Yan, Q.; Shen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wong, C.-K.; Pang, C.-S.; Ou, W.; et al. ChildPredictor: A Child Face Prediction Framework with Disentangled Learning; IEEE Transactions on Multimedia; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2223–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; Uh, Y.; Yoo, J.; Ha, J.-W. Stargan v2: Diverse image synthesis for multiple domains. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 8188–8197. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Ding, Y.; Xia, M.; Liu, X.; Ding, E.; Zuo, W.; Wen, S. Stgan: A unified selective transfer network for arbitrary image attribute editing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3673–3682. [Google Scholar]

- Or-El, R.; Sengupta, S.; Fried, O.; Shechtman, E.; Kemelmacher-Shlizerman, I. Lifespan age transformation synthesis. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 739–755. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aittala, M.; Hellsten, J.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Analyzing and improving the image quality of stylegan. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 8110–8119. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Liao, W.; Yang, M.Y.; Song, Y.-Z.; Rosenhahn, B.; Xiang, T. Disentangled lifespan face synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3877–3886. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Lee, H.J. Effective Attention-Based Feature Decomposition for Cross-Age Face Recognition. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Li, Q.; Xie, H.; Lau, R.Y.; Wang, Z.; Smolley, S.P. Least squares generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2794–2802. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.-C.; Chen, C.-S.; Hsu, W.H. Cross-age reference coding for age-invariant face recognition and retrieval. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 768–783. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Zhang, M.; Yu, C.; Liu, Z. Balanced MSE for Imbalanced Visual Regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 7926–7935. [Google Scholar]

- Eidinger, E.; Enbar, R.; Hassner, T. Age and gender estimation of unfiltered faces. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2014, 9, 2170–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.; Lei, Z.; Liao, S.; Li, S.Z. Learning face representation from scratch. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1411.7923. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1026–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- MEGVII Inc. Face++ Research Toolkit. Available online: https://www.faceplusplus.com/faceid-solution/ (accessed on 21 May 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).