Abstract

Security and Quality of Service (QoS) in communication networks are critical factors supporting end-to-end dataflows in data centers. On the other hand, it is essential to provide mechanisms that enable different treatments for applications requiring sensitive data transfer. Both applications’ requirements can vary according to their particular needs. To achieve their goals, it is necessary to provide services so that each application can request both the quality of service and security services dynamically and on demand. This article presents QoSS, an API web service to provide both Quality of Service and Security for applications through software-defined networks. We developed a prototype to conduct a case study to provide QoS and security. QoSS finds the optimal end-to-end path according to four optimization rules: bandwidth-aware, delay-aware, security-aware, and application requirements (considering the bandwidth, delay, packet loss, jitter, and security level of network nodes). Simulation results showed that our proposal improved end-to-end application data transfer by an average of 45%. Besides, it supports the dynamic end-to-end path configuration according to the application requirements. QoSS also logs each application’s data transfer events to enable further analysis.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, we live in an interconnected world where daily use applications and services to enable video streaming, video game platforms, office applications, remote work, financial services that require handling sensitive information, and medical applications, among many others. Also, a massive amount of data is generated by a wide variety of devices. Specifically, IoT devices will be one of the primary sources of information and, therefore, could become the largest provider for big data science [1] and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-related applications.

Each application has different requirements regarding computing resources, data storage, network quality of service, and security schemes. The applications that make quick decisions require analyzing and processing large amounts of data in the shortest possible time. To achieve their goals, they need to have mechanisms that enable quality of service and security policies, especially when transferring their information among data centers connected with state-of-the-art communication networks.

Security and Quality of Service (QoS) are two critical network services that data center services are required to provide. Security mechanisms provide proof of identity, preserve protected information, and prevent database tampering, data alteration and modification, deviation, duplication, and theft of information [2].

QoS can improve the application’s performance according to their particular needs. The security and quality of service mechanisms are not independent. Some security mechanisms affect the effectiveness of QoS and vice versa. The intelligent management of quality of service parameters supports the provisioning of security strategies for applications that handle sensitive data. The network infrastructure must support several robust routing mechanisms that also provide reliability on the selected paths [3].

Software-defined network (SDN) provides a mechanism that enables applications to request certain services or network parameters such as quality of service, security schemes, or bandwidth, among others [4].

SDN can address the network programmability problem by allowing applications to program networks at run-time, whether intra-domain or even inter-domain, to meet their requirements [5]. This process is considered an advantage of SDN compared to traditional networks. SDNs are gradually spreading to large-scale (such as data centers), and complex networks (multi-agency collaborative networks) [6].

We designed QoSS, which is defined as an API Web prototype to conduct a case study to provide QoS and a security scheme to applications. The QoSS allows applications to send their network and security requirements and gets the optimal end-to-end path considering four optimization schemes: maximum bandwidth, maximum security level, minimum delay, and based on application requirements. In the application requirements optimization scheme, we use a multi-objective optimization method considering the network parameters such as bandwidth, delay, packet loss, and jitter. Also, the security level of each node is considered an additional parameter. In the application requirements optimization scheme, the network and security level parameters must comply with the application requirements. The QoSS configures the optimal path using the REST API provided by the SDN controller. Then, the application transfers data from the source to the destination nodes. The QoSS also logs each application’s data transfer events to enable further analysis.

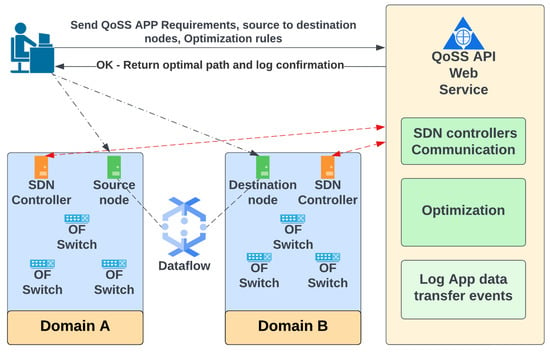

The QoSS API improves the applications’ performance in their data flow transfer process, providing a QoS-based optimal end-to-end path according to their requirements. Furthermore, it provides a secure scheme optimal end-end-end path for the application data-sensitive transfer process. Figure 1 shows the QoSS API web service general view.

Figure 1.

QoSS API Web Service general view.

We organized the rest of the article as follows: Section 2 presents the related work. Section 3 introduces our proposal called QoSS API: its design and implementation. Section 4 describes the experimental setup. Section 5 presents the performance evaluation and the discussion of the results. Section 6 presents the conclusions and future directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Software Defined Networking

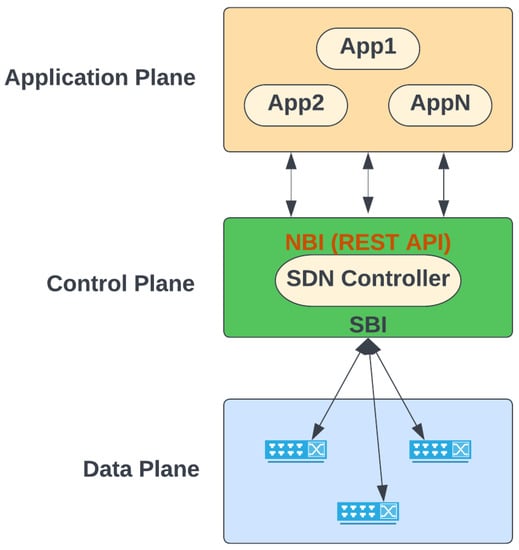

Software Defined Networking is a network architecture that separates the network control functions from the communications equipment. SDN allows the user/application to manage the traffic on the network. A remarkable feature of the SDN is that it integrates and enables network monitoring, traffic control, quality of service (QoS), and security. The SDN bases its architecture on three functional layers: the data plane, the control plane, and the application plane [7]. In SDN general architecture [8], the SDN controller resides in the control plane. Figure 2 shows a simplified view of the SDN general architecture.

Figure 2.

SDN General Architecture.

- Application plane: Consists primarily of SDN and End-User applications that require network services, such as network security, quality of service, traffic engineering, access control management, and load balancing, among others. The network is programmable through applications running on top of the controller interacting with devices on the underlying data plane. The programmable network capacity is a crucial aspect of SDN.

- Control plane: Consists of a set of software-based SDN controllers that provide a consolidated control functionality of an open interface. SDN controllers interact between the North, South, and East/West interfaces. One of its purposes is to coordinate the flow forwarding among network devices (nodes) based on its default routing algorithm. The controller default routing algorithm typically focuses on finding the path with the shortest distance among end-to-end nodes.

- Data plane or infrastructure layer: It consists mainly of forwarding elements, including physical and virtual switches accessible through an open interface that allows packet switching and forwarding. The flows provide the basis for forwarding decisions. A flow is a set of values in the packet fields that act as matched criteria (a filter) and actions (the instructions).

The terms Northbound Interface and Southbound Interface are used to identify two access points to hardware and software. A description of the two main SDN controllers interfaces is described below:

- Southbound interface (SBI): Provides a communication environment between the controller and switches or communication devices. Install the appropriate flow rules in the device forwarding table. OpenFlow [9] is the open-source community’s most widely implemented Southbound interface standard.

- Northbound interface (NBI): Provides communication between the SDN controller and network applications running at the application plane. This communication is crucial, as the requirements of each network application can vary considerably. The applications can communicate with the SDN using various APIs, such as ad-hoc and REST APIs, to request network resources or services according to their needs.

Placing the network control logic at the central controller provides flexibility, optimizes network management, and flow monitoring, which is very important in the practical usage of SDN [10].

Our proposal resides in the application plane and communicates to the SDN controller using the REST API provided by the Northbound interface. We used these SDN functionalities to create, query, and delete flow rules in OpenFlow (OF) switches to forward data flow according to applications’ QoS and node security requirements.

For additional information, a review of SDN controllers is presented in [11], and in [12], the authors presented a comparative study of SDN controllers. For the aim of our research, we used OpenDaylight [13] SDN controller.

2.2. Security Level Evaluation

This section describes the Security Level evaluation process to provide a secure end-to-end path mechanism applied to our research scenario.

Several methods can be considered for determining the value of the path’s security level. Some research proposals focus on the attack graph-based method that uses information from network elements (nodes) and their relationships (edges) between elements to determine their risk and identify the route that can be used to attack a target node. In [14], proposes to measure the risk of a specific path through an arithmetic evaluation of the network elements and edges based on the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) [15], in addition to analyzing the vulnerability correlation between each node. In [16] the authors propose an attack graph-based Moving Target Defense (MTD) technique focused on the SDN, which shuffles the network configuration of a host based on its criticality, which can be exploited by attackers when the host is in the attacked path. Both proposals use CVSS to get certain vulnerability assessment scores; however, the authors in [14] mentioned that the CVSS scores have the problem that they do not reflect the specialized parts for each security environment since they are a method for universal evaluation. In addition, the authors in [17] determined that the CVSS is not enough to prioritize software vulnerabilities since their environments have different characteristics.

The QoSS API includes a decision variable that can be modified to use the CVSS evaluation. However, as a use case, we propose employing a strategy based on elements that are part of an Information Security Management System (ISMS). Under this approach, Internet Service Providers (ISP) or data center services providers should deploy an ISMS in accordance with the best practices in information security to apply policies and procedures for information assets managing sensitive data. ISMS requires a risk assessment of essential information assets for its mission-critical operations. ISMS could comply with international standards such as ISO/IEC 27001 [18]. In the case of risk management, it can be based on MAGERIT 3.0 [19], among others.

ISO/IEC 27001 and MAGERIT are well-known international standards and methodologies that private and public organizations widely use.

The traditional risk assessment method for information security uses assets, threats, and vulnerabilities. It is not our research scope to define a new methodology for risk assessment.

To calculate the end-to-end path security level, we simulated a scenario where we defined essential information assets (network nodes) for data center (domains) communications. We used predefined information security threats based on the MAGERIT 3.0 catalog of elements.

Each information asset can include a set of threats. Each threat must be evaluated according to various criteria for risk management or assessment methodology. For the aim of our research and to provide a case study, we focused on using only the information asset vulnerability criterion.

As part of our research, each threat’s criterion is evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5. Level 1 refers to Without any protection and level 5 is considered a level with Reinforced protection. Table 1 shows the proposed assessment list for our scenario’s information asset vulnerability criterion.

Table 1.

Threat evaluation criterion.

The value assigned to the criterion can be related to the number of security controls already implemented in the information asset, ranging from 1 to 5. It is important to note that this assignment is not a previously defined rule in any of the methodologies; it is only a guide for our simulation scenario, but it can be used in a real scenario.

According to the MAGERIT 3.0 catalog of elements, each information asset can have several threats. For the case of our research, we selected some of the general threats that can be used to calculate the security level. These threats are displayed below:

- Unauthorized access.

- Malicious code.

- Denial of service.

- Vulnerability of programs (software).

- Deliberate attacks.

- Communication services failure.

- Interception of information (listening).

- Routing errors.

Each threat is evaluated based on the values in Table 1 for the information asset vulnerability criterion to determine the security level. In a real scenario, it is essential to emphasize that the IT Specialists or the person directly responsible for the information asset, in partnership with the Information Security Officer or a person with a similar role, evaluate the criteria for each information asset.

We get the security level of the information asset by calculating the average values of the total number of threats. Finally, to get the end-to-end path security level, we get the security level average value of the information assets (network nodes) in the path. Table 2 shows a textual representation of the numeric value using a rating scale.

Table 2.

Security level rating scale.

2.3. Quality of Service in SDN

This section presents an overview of the quality of service (QoS) proposals in software-defined networks.

QoS is an essential element in data center services that impact the application performance requiring intensive network communication. Regarding QoS in SDN, we identified proposals considering their architecture and path selection algorithm. Examples of these proposals are described below:

In OpenQoS [20], and VSDN [21] use the shortest path among nodes. In some cases, they also use the delay parameter in their path selection process. Most of the QoS proposals control bandwidth parameter for data flows allocation [22,23,24]. In CECT, Ref. [25] proposed a strategy to reallocate network resources and minimize network congestion taking the available bandwidth as a constraint. In AmoebaNet [5], authors proposed a service that uses a Dijkstra shortest path variant algorithm to compute an end-to-end network path, using only a bandwidth parameter as a constraint. Most of the proposals analyzed describe experiments considering QoS within a single domain and one controller for the SDN, except in AmoebaNet. The main goal of the research works described above is to use the bandwidth as the network parameter for their routing algorithm.

Our proposal QoSS consists of an API Web service prototype to provide QoS and a security scheme to applications. The QoSS differs from the other QoS proposal mainly because it provides several optimization schemes according to the needs of the application. Furthermore, our proposal improves the application’s performance by allowing the dynamic end-to-end path configuration considering four optimization schemes: maximum bandwidth, maximum security, minimum delay, and application requirements (based on network bandwidth, delay, packet loss, jitter, and security level that must comply with application requirements). Regarding QoS and Security Level in our proposal, the applications have the flexibility and the option to request an end-to-end path with the highest security level. In addition, applications can request an end-to-end path that meets a certain security level and QoS requirements. The QoSS API also allows applications to log data transfer events to enable further analysis for service agreements or business needs. These are the main contributions of our proposal.

2.4. Application Programming Interface

The Application Programming Interface (API) is a mechanism that allows two software components or agents to communicate with each other [26]. APIs allow interoperability among different platforms on the web.

APIs emerged from the need to exchange information with various data providers to solve particular objectives. When designing an API, it is essential to consider its usability, scalability, and performance. There are different APIs paradigms. Some examples are listed below:

- Native library APIs: Provide additional functionality through classes or other functions. They are specific to programming languages such as Java, C++, Python, .Net, and others.

- SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol): SOAP APIs are web services that rely on a strict XML protocol to define the message exchange format for requests and responses.

- RPC-based (Remote Procedure Call): RPC-based APIs are web services that call a method on a remote server using HTTP.

- REST (Representational State Transfer): REST APIs are web services that allow a client or program to request resources using URL routes and the operation to perform (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE). REST APIs use HTTP as the transport protocol for message requests and responses. It is the most commonly used type of API across several platforms and cloud providers.

For the aim of our research, we designed a prototype of an API Web based on REST. The primary purpose of REST is to improve different non-functional properties of the web system, such as performance, scalability, simplicity, reliability, and visibility [27].

REST APIs are generally based on the following rules:

- Resources are part of URLs.

- Each resource has one URL for collections (plural) and another URL for a specific element (singular).

- Use nouns instead of verbs for resources.

- Use HTTP methods to specify the action to the web server (POST, GET, PUT, and DELETE) for CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations.

- Use standard HTTP response status code to indicate success or an error.

- REST APIs return JSON or XML responses. Lately, JSON is most used and has become a standard for modern APIs.

3. Design and Implementation

In this section, we present the design of QoSS, an API Web that provides QoS and security following application requirements. Our proposal’s main objective is to find the optimal end-to-end path considering four optimization schemes: bandwidth-aware, delay-aware, security-aware, and application requirements (considering the bandwidth, delay, packet loss, jitter, and security level of each node in the network). Besides, it supports the dynamic end-to-end path configuration according to applications requirements. The QoSS API Web prototype also records each application data transfer to enable further analysis.

The problem formalization for optimal end-to-end path selection according to the applications’ QoS and Security level requirements is described below.

3.1. Path Selection: Problem Formalization

In a communication network topology, there are n paths for data flow transfer from source to destination nodes (typically referred to as end-to-end paths), and it is represented in Equation (1):

where:

- s = Source node,

- d = Destination node,

- P = Set of paths from the source node s to the destination node d,

- p = End-to-end path, ,

- l = Network links for each node on an end-to-end path.

The network parameter values are different for each path. These parameters are the metrics for network conditions. Our proposal uses the bandwidth , delay , jitter , and packet loss to provide network QoS. We also use the parameter to provide the path security level.

The default routing algorithm selects network paths considering the cost or distance between network nodes. The SDN controller uses these metrics to select the shortest path (). It is represented in Equation (2) as the minimum cost value in n possible paths:

The default routing algorithm does not consider other additional parameters that provide network conditions. Some applications should consider these parameters to improve network performance instead of just considering the shortest path. The path () considers the network parameters and security level used by our proposal. It is represented in Equation (3):

Regarding the end-to-end path Security Level, the general process to calculate it is described in Section 2.2 and is represented in Equation (4).

where:

- = End-to-end path, ,

- S = Security level for each network node , ,

- s = Thread vulnerability network node evaluation, ,

- t = Values set for each threat for a given node, , ,

- c = Criterion score set for a given threat, , .

We used a symbol to identify a path with better metrics conditions. It must have the maximum available bandwidth and security level among the n paths and are represented in Equations (5) and (6) respectively. Also, this path must have the minimum value of each of the corresponding end-to-end parameters such as delay, jitter, and packet loss among the n paths, represented in Equations (7)–(9).

In end-to-end network path selection, in the case of the bandwidth parameter, it has a concave metric composition where the end-to-end paths were selected considering the minimum capacity bandwidth of the network links that rules the maximum bandwidth for the corresponding . The parameters, such as delay and jitter, have an additive metric composition rule for the end-to-end path. To get the path security level value, we calculated it as the average of the values of each network node in the end-to-end path, as represented in Equation (4). For the scope of our research, we used these criteria for end-to-end path calculation based on QoS constraints and security levels:

where:

- = Path available bandwidth,

- = Path security level

- = Path delay,

- = Path jitter,

- = Path packet loss.

The applications and their network requirements set are represented in Equations (10) and (11):

where:

In Equation (12), the application requires a minimum bandwidth limit rate, and in Equation (13) a minimum security level. In Equations (14)–(16), each metric has a maximum tolerable limit required by the application. The network and security level parameters must comply with the application’s requirements:

As mentioned above, our proposal supports four optimization rules: maximum bandwidth (Equation (5)), maximum security (Equation (6)), minimum delay (Equation (7)), and according to application requirements (complying with lower limits for bandwidth, delay, jitter, packet loss rate, and level of security parameters). The application requirements rule process is described below:

Each application requires a set of network parameters, as described in Equations (12)–(16). To resolve the multi-objective problem [28], we used the -constraint method [29] for path selection. We define the following objective function, represented in Equations (17)–(19):

We used the delay parameter as the primary objective, subject to the constraints of the other objectives (end-to-end available bandwidth, security level, jitter, and packet loss). From the set of feasible paths, we minimize the delay to get the optimal path when the available bandwidth and security level are greater than or equal to the application and packet loss rate and jitter are less than or equal to what is required by the application. Equations (20) and (21):

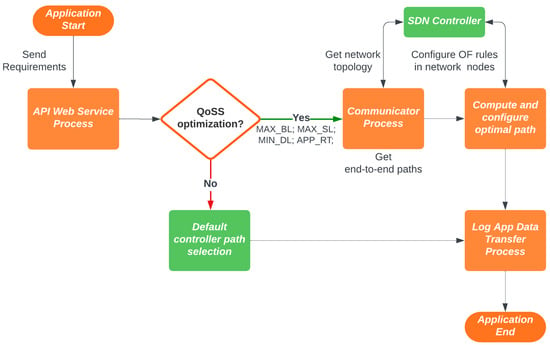

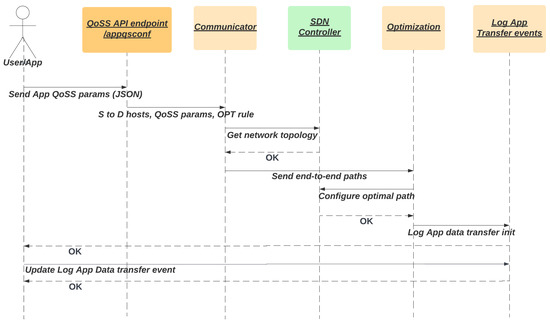

3.2. API Web Design

The QoSS general design is based on the REST API web paradigm. Figure 3 shows the interaction between the different modules and their communication. It starts with the application that sends to the QoSS API its network service requirements (these can be the quality of service and security level). QoSS API gets the network topology querying the SDN Controller REST API to compute the optimal end-to-end path and performs its configuration on the OF switches through communication by the SDN Controller REST API. QoSS creates a record of the application data transfer events. Figure 4 shows the QoSS API general sequence diagram.

Figure 3.

QoSS General Process.

Figure 4.

QoSS API general sequence diagram.

The QoSS API consists of the following general processes:

- API Web Service (endpoints)

- (a)

- apptransfer (Log app data transfer process)

- (b)

- appflowrule (Applications flow rule control)

- (c)

- appqsconf (Get applications QoS parameters)

- Communicator

- (a)

- Get network topology

- (b)

- Get end-to-end paths

- Optimization

- (a)

- Compute optimal path

- (b)

- Configure optimal path

3.3. API Web Service

This process describes an API Web design that allows applications to communicate via HTTP commands, such as:

- get: fetch an existing resource.

- post: create a new resource.

- put: create or update a resource.

- delete: delete a resource.

We designed the following Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) or API endpoints:

3.4. API Endpoint: Apptransfer

The application’s transfer log is stored using the apptransfer endpoint. Table 3 shows the resource description for apptransfer endpoint.

Table 3.

RESOURCE: apptransfer.

Table 4 shows the apptransfer endpoint specification.

Table 4.

API endpoint specification: apptransfer.

| Listing 1. Response array of JSON objects for apptransfer endpoint. |

| { |

| "idtlog": 12, |

| "idapp": "6000", |

| "snode": 1, |

| "dnode": 20, |

| "ipsource": "1", |

| "ipdest": "6", |

| "r_bl": 85, |

| "r_dl": 30, |

| "r_sl": 0, |

| "r_jl": 8, |

| "r_plr": 0.0, |

| "optrule": "MAX_BL", |

| "idflow": 6, |

| "priority": 201, |

| "ipprot": 6, |

| "appclass": "BE", |

| "optpath": "1, 2, 5, 4, 17, 18, 20", |

| "starttime": "2022:07:18 10:29:20", |

| "endtime": "2022:07:18 10:32:41" |

| }, |

| {. . .} |

| Listing 2. Request <body> JSON object for apptransfer endpoint. |

| { |

| "idtlog": 12, |

| "snode": 1, |

| "dnode": 20, |

| "ipsource": "1", |

| "ipdest": "6", |

| "r_bl": 85, |

| "r_dl": 30, |

| "r_sl": 0, |

| "r_jl": 8, |

| "r_plr": 0.0, |

| "optrule": "MAX_BL", |

| "idflow": 6, |

| "priority": 201, |

| "ipprot": 6, |

| "appclass": "BE", |

| "optpath": "1, 2, 5, 4, 17, 18, 20", |

| "starttime": "2022:07:18 10:29:20", |

| "endtime": "2022:07:18 10:32:41" |

| } |

| Listing 3. Request <body> JSON object for apptransfer endpoint. |

| { |

| "idflow": 6, |

| "optpath": "1, 2, 5, 4, 17, 18, 20", |

| "starttime": "2022:07:18 10:29:20", |

| "endtime": "2022:07:18 10:32:41" |

| } |

3.5. API Endpoint: Appflowrule

The appflowrule endpoint receives a JSON file to manage application-specific flow rules. Table 5 shows the appflowrule endpoint specification.

Table 5.

API endpoint specification: appflowrule.

| Listing 4. Request <body> JSON object for appflowrule endpoint. |

| { |

| "priority": 200, |

| "date_created": "2022-08-09 12:00:00" |

| } |

3.6. API Endpoint: Appqsconf

The appqsconfig endpoint receives a JSON file with the application QoS and Security level requirements. Table 6 shows the appqsconfig endpoint specification.

Table 6.

API endpoint specification: appqsconfig.

| Listing 5. Request <body> JSON object for appqsconfig endpoint. |

| { |

| "ipsource": 10.0.0.1, |

| "ipdest": 10.0.0.6, |

| "r_bl": 85, |

| "r_dl": 30, |

| "r_sl": 5, |

| "r_jl": 8, |

| "r_plr": 0.008, |

| "optrule": "MAX_BL", |

| "priority": 201, |

| "apikey":"secretapik123xxxx" |

| } |

In Listing 5, the application sends a JSON file to the QoSS API web containing the IP addresses of the source and destination nodes, as well as the end-to-end requirements in terms of minimum bandwidth, minimum security level, maximum delay, maximum jitter, maximum packet loss, flow priority, and the optimization rule, which in this case is the maximum bandwidth that meets the minimum requirement.

3.7. Communicator Process

The QoSS starts the communicator process to get the network topology querying the SDN controller. Then, it creates an internal network to:

- Assign weights on each link (bandwidth, security level, delay, jitter, packet loss rate)

- Find the end-to-end paths from the source to destination hosts.

The Communicator process creates a set of end-to-end paths to be used by the Optimization process.

3.8. Optimization Process

The QoSS proposes that applications can request the optimization rule according to their requirements in network parameters to transfer their data flows. This process can support four optimization rules: maximum bandwidth, maximum security level, minimum delay, and according to application requirements (complying with bandwidth, delay, jitter, packet loss rate, and the security level parameters).

Section 3.1 describes the process for computing the optimal path according to the optimization rule required by the applications.

Once the QoSS gets the optimal path, it configures the flow rules containing the optimal path with the application priority higher than the controller forwarding method. Each data flow rule is allocated and configured in the OF switches for the end-to-end path through the SDN controller.

The following section describes the simulation model and experiment setup for the application dataflow transfer process among hosts located in distributed domains.

4. Experimental Setup

Simulation Model

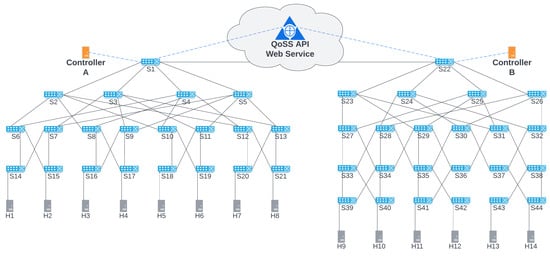

The simulation model considers a network topology for host-to-host data flow transfers between two SDN-enabled distributed clouds. We propose a distributed network, as illustrated in Figure 5. We aim to find the optimal path to transfer the most dataflow through the end-to-end nodes. In this case, we transfer dataflow between H1 and H14 hosts.

Figure 5.

Experimental topology.

Mininet [30] is one of the most used platforms in the literature for SDN emulation. It has compatibility and flexibility with other applications and controllers. We used Mininet for experimental setup and network testbed.

We installed Mininet in a virtual machine with a Linux Debian operating system, with 4vCPUs, 16 GB of RAM, and 200 GB of disk space (NLSAS disks). Two other virtual machines were used for the OpenDaylight SDN controllers with the same specifications.

List of software and tools used:

- Linux Debian 10

- Mininet 2.3

- OpenDayLight (ODL) SDN Controller

- Iperf for data stream transfers performance

- Anaconda Scientific Python

- QoSS API web service:

- –

- Python Flask with SQLAlchemy, JWT

- –

- Python 3 programming language

- –

- Built-in Python Flask Web Server

- –

- Postman for API Rest testing

- –

- Visual Studio Code

Figure 5 shows the experimental topology of an SDN-enabled network with two domains. Controllers A and B managed their domains, respectively. Since they are independent domains, each controller gets its domain’s status and network information. In [31], the authors describe an inter-domain approach where each local SDN controller communicates with a global SDN controller. In our proposal, we developed the QoSS API to communicate with the SDN controllers and find the end-to-end paths among each domain host.

For this scenario, the network parameters configured in each link are delay, jitter, and bandwidth, and propose a security level for each node. We simulated the network parameters and the security level values. Regarding the security level parameter, we simulated it according to the evaluation process described in Section 2.2 and represented in Equation (4). Table 7 shows a vulnerability evaluation score for a network node link interface (S6,S14). The resulting score of 2 indicates that the network node has Low protection according to the threat criterion evaluation in Table 1.

Table 7.

Vulnerability evaluation simulation scenario: Threats evaluation for the network node link interface (S6,S14). Evaluation’s result (average): 2.

Table 8 shows the security level evaluation for one of the end-to-end paths from H1 to H14 hosts. This path has Low security as referred in Table 2 but is closer to Medium according to its evaluation result of 2.7. Additional security controls could be applied to network nodes’ threat evaluation to increase the security level score.

Table 8.

Vulnerability evaluation simulation scenario: Path Security Level from hosts H1 to H14. Evaluation’s result (average): 2.7.

The QoSS API provides applications to request a secure end-to-end path based on an optimization scheme considering the path security level value.

In the Mininet simulator, we assigned values for each link’s delay, jitter, and bandwidth parameters. The security level was added as an additional metric in the QoSS API optimization process. The metrics values corresponding to each link in the experimental topology for A and B domains are represented in Table A1 and Table A2 listed in Appendix A.

In this work, we used the OpenDayLight (ODL) [13] controller for its flexibility in getting the network topology information and providing a REST API that enables network programmability. The QoSS API assigned the flow rules on each OF switch to accomplish application QoS or security level optimization using its API endpoints described in Section 3.

Mininet emulates the experimental network topology where each domain uses its ODL controllers. Controller A Domain has 21 OpenFlow (OF) switches and 8 compute hosts, while Controller B Domain has 23 OF switches and 6 compute hosts.

The QoSS API gets the network topology querying the SDN controller REST API, then it finds the end-to-end paths from source and destination nodes. If nodes belong to different domains, it is necessary to perform an end-to-end path selection process in each domain, establishing the end-to-end path between the source/destination node. Once the QoSS API gets the optimal path, it configures the flow rules on each OF device through the SDN controller. Finally, the QoSS API end-to-end optimal path is used to forward the application dataflow transfer from the source to the destination node.

In our experiment, the controller default routing method is based on the path with minimum hops from H1 to H14 hosts.

We defined the following steps for tests execution:

- Experimental topology development using the Python CLI provided by Mininet.

- Create an inter-domain approach network topology with two domains (A and B). Use one ODL external controller per domain.

- Run network performance tests from H1 to H14 with IPERF using TCP and UDP dataflows with Controller default data flow forwarding:

- (a)

- First tests set: Execute data transfer test (H1 to H14). Get the elapsed time in seconds.

- (b)

- Second tests set: Execute data transfer test (H1 to H14). Get the number of Mbps transferred for a specific period of time.

- Repeat step 3 with QoSS API using different optimization rules (MAX_BL, MIN_DL, and APP_RT).

- Get results.

5. Performance Evaluation

We used IPERF [32] to test network performance between hosts H1 and H14, applying the ODL controller default routing method and QoSS API web-based on MIN_DL, and MAX_BL optimization rules in the simulation model. IPERF was configured with default values and set time intervals to 200 s for each data transfer. We repeated the experiment 20 times for TCP, and UDP data flows.

The QoSS API selected the end-to-end paths that matched the bandwidth, delay, jitter, and security level criterion. Table 9 shows the QoSS optimal paths and the ODL default path metrics used in the test sets.

Table 9.

ODL default and QoSS optimal paths metrics from Hosts 1 to 14 in the simulation model.

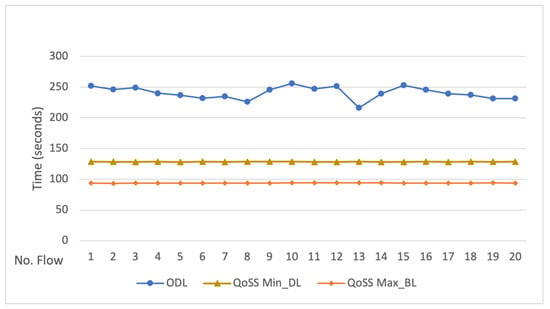

Our first experiment goal is to measure the application completion time when transferring 1 GB of data using the ODL controller default method compared to the QoSS API maximum bandwidth (MAX_BL) optimization rule. The controller default transfer time was 240.31 s on average, with a standard deviation of 10.16 s. Meanwhile, the QoSS API MAX_BL optimal path requires less than half of the time to transfer the same amount of data, with an average of 91.34 s and a standard deviation of 0.20 s, a 62% improvement. We also compared the ODL default method to the QoSS API minimum delay (MIN_DL) optimization rule. Figure 6 shows the evaluation results.

Figure 6.

ODL vs. QoSS API optimization rules comparison. Time elapsed (in seconds) for each test to transfer 1 GB of raw data.

The second set of experiments considered the ODL controller default and QoS application requirements. In this scenario, we evaluated the advantages of using the QoSS API APP_RT optimization rule compared to the path provided by the ODL SDN controller.

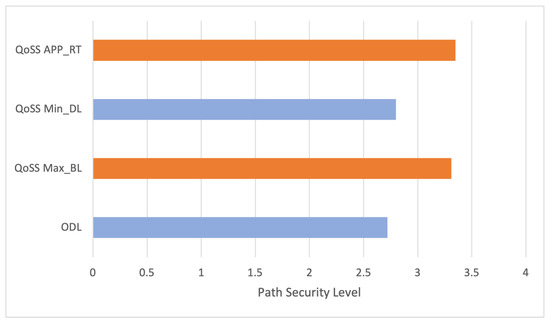

The application QoS and security level requirements for end-to-end paths were: bandwidth ≥ 70 Mbps, delay ≤ 145 ms, jitter ≤ 15 ms, and the security level . We used the QoSS optimization rule based on application requirements (APP_RT). The metric values for the QoSS API APP_RT selected end-to-end path are shown in Table 9.

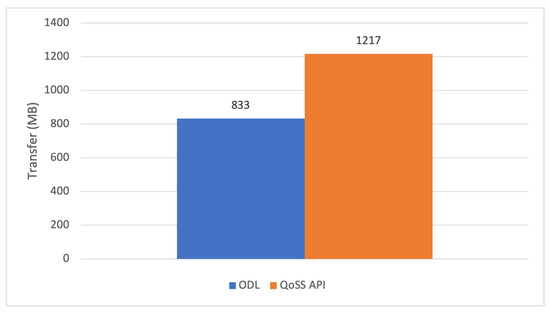

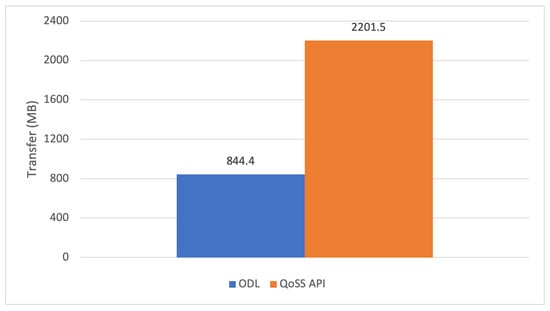

IPERF was used to transfer data flows between H1 and H14 hosts. Using TCP and UDP flows, we measured the data transfer capacity in MB with a time interval of 200 s. As in the previous cases, we performed the IPERF tests 20 times.

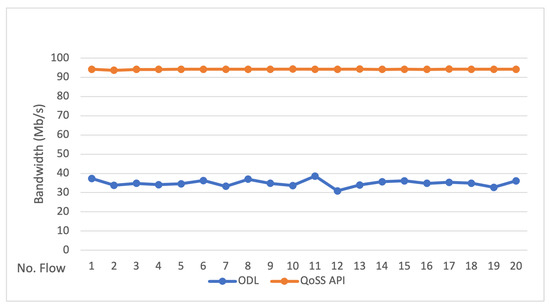

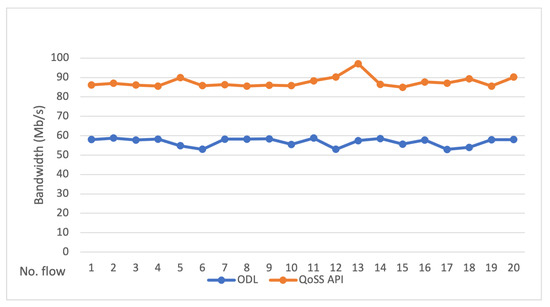

The ODL controller obtained an average of 833 MB with UDP dataflows, and the QoSS API APP_RT transferred 1217 MB. In this test, the QoSS transferred around 45% more data than the ODL controller in the same time interval. Regarding the TCP flow tests, the controller transferred 844.4 MB, and the QoSS API APP_RT transferred 2201 MB. The UDP and TCP test results are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. The TCP and UDP transfer rate comparison between the controller default versus the QoSS API APP_RT flow forwarding methods are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 7.

UDP Data transfer comparison. Controller default (ODL -SPF) vs. QoSS API (APP_RT). Time interval: 200 s.

Figure 8.

TCP Data transfer comparison. Controller default (ODL -SPF) vs. QoSS API (APP_RT). Time interval: 200 s.

Figure 9.

TCP Data transfer rate comparison. Controller default vs. QoSS API (APP_RT).

Figure 10.

UDP Data transfer rate comparison. Controller default vs. QoSS API (APP_RT).

The test results showed that the QoSS API APP_RT optimal path considering a QoS approach has a higher performance than the path provided by the SDN controller default method. In the test results, it is observed that the QoSS API improved the application data transfer process by an average of 45%, and in some cases, 62% compared to the SDN controller method.

The controller default algorithm seeks to establish a path regardless of the network conditions. This algorithm selects the shortest path by default, considering a single metric for the routing process.

Concerning the security level required by the application (≥3), Figure 11 shows that only the QoSS APP_RT and the QoSS Max_BL optimal paths meet the requirement while the ODL default path does not. As a result, our proposal enables applications to use an end-to-end network path with a specific security level requirement while also benefiting from its performance.

Figure 11.

ODL vs. QoSS API Path Security Level Comparison.

6. Conclusions

The QoSS API web enhances applications’ performance by providing dynamic and on-demand QoS and security-level optimal end-to-end paths. The path selection process considers network conditions and application requirements. The QoSS API web is adaptive for any routing condition that can be established. In contrast, the controller default algorithm does not address these essential features to improve the routing service.

Our proposal QoSS API provides end-to-end paths that meet the QoS requirements established by applications, such as bandwidth, delay, jitter, and packet loss rate, improving their performance by an average of 45%, and in some cases by 62%. Furthermore, QoSS provides end-to-end paths with a specific security level that can be used for data-sensitive applications. QoSS also creates a log of each application’s data transfer events to enable further analysis for a decision-making process. QoSS API web prototype also enhances the development of SDN testbeds.

In future work, we will improve the QoSS API web service to provide additional application requirements such as computing resources, storage, and security services for data-sensitive applications. Also, to support AI-related applications and a software-defined data center cloud architecture.

Author Contributions

All the authors were involved in research design and conceptualization; Writing—original draft, J.E.L.-R., J.E.G.-T. and R.R.-R.; Methodology, J.E.L.-R., A.T., S.V.-R. and A.G.-M.; Formal analysis, J.E.G.-T., A.T. and R.R.-R.; Writing—review and editing, J.E.L.-R., R.R.-R., S.V.-R. and A.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONACYT, Mexico), and the Centro de Investigacion Cientifica y de Educacion Superior de Ensenada, Baja California, (CICESE, Mexico).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Appendix A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: | |

| SDN | Software Defined Network |

| ISMS | Information Security Management System |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| REST | Representational State Transfer |

Appendix A

Table A1 and Table A2 show the metrics values corresponding to each link in the experimental topology for A and B domains.

Table A1.

Controller A Network Node metrics in the simulation model.

Table A1.

Controller A Network Node metrics in the simulation model.

| Link | Metrics | Link | Metrics | Link | Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1, S2 | 20, 2.2, 0, 100 | S4, S12 | 20, 3.6, 0, 100 | S11, S18 | 20, 2, 0, 70 |

| S1, S3 | 25, 3.5, 0, 100 | S5, S7 | 20, 3.5, 10, 100 | S11, S19 | 25, 2, 0, 100 |

| S1, S4 | 10, 2.5, 0, 100 | S5, S9 | 12, 4.5, 0, 100 | S12, S20 | 55, 2, 0, 100 |

| S1, S5 | 5, 3.8, 0, 100 | S5, S11 | 25, 2.7, 0, 100 | S12, S21 | 15, 2, 0, 80 |

| S2, S6 | 20, 2.3, 0, 100 | S5, S13 | 15, 3.5, 0, 100 | S13, S20 | 15, 2, 5, 80 |

| S2, S8 | 15, 4.2, 0, 100 | S6, S14 | 80, 2, 10, 80 | S13, S21 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S2, S10 | 25, 3.8, 0, 100 | S6, S15 | 60, 2, 0, 60 | S14, H1 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S2, S12 | 10, 3.6, 0, 100 | S7, S14 | 25, 2, 0, 100 | S15, H2 | 0, 2, 0, 80 |

| S3, S7 | 25, 3.5, 5, 100 | S7, S15 | 20, 2, 5, 80 | S16, H3 | 0, 2, 0, 70 |

| S3, S9 | 20, 4.5, 0, 100 | S8, S16 | 20, 2, 0, 100 | S17, H4 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S3, S11 | 10, 2.7, 0, 100 | S8, S17 | 15, 2, 0, 70 | S18, H5 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S3, S13 | 20, 3.5, 5, 100 | S9, S16 | 10, 2, 5, 50 | S19, H6 | 0, 2, 0, 70 |

| S4, S6 | 15, 2.3, 0, 100 | S9, S17 | 15, 2, 5, 80 | S20, H7 | 0, 2, 0, 80 |

| S2, S8 | 10, 4.2, 0, 100 | S10, S18 | 15, 2, 0, 80 | S21, H8 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S4, S10 | 15, 3.8, 0, 100 | S10, S19 | 10, 2, 0, 50 |

100Metrics: delay (ms), security, jitter (ms), and bandwidth (Mbps).

Table A2.

Controller B Network Node metrics in the simulation model.

Table A2.

Controller B Network Node metrics in the simulation model.

| Link | Metrics | Link | Metrics | Link | Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S22, S23 | 15, 2.5, 0, 100 | S27, S34 | 15, 4.4, 5, 80 | S34, S39 | 10, 2, 0, 80 |

| S22, S24 | 10, 4.5, 0, 100 | S28, S33 | 15, 4.4, 0, 100 | S34, S40 | 20, 2, 0, 100 |

| S22, S25 | 5, 3.8, 0, 100 | S28, S34 | 20, 3.8, 0, 80 | S35, S41 | 15, 2, 0, 100 |

| S22, S26 | 5, 3.6, 0, 100 | S28, S35 | 15, 2.2, 10, 60 | S35, S42 | 15, 2, 0, 80 |

| S23, S27 | 15, 3.5, 0, 100 | S29, S34 | 15, 3.8, 0, 70 | S36, S41 | 10, 2, 0, 70 |

| S23, S29 | 15, 2.7, 0, 100 | S29, S35 | 20, 2.2, 0, 80 | S36, S42 | 15, 2, 0, 100 |

| S23, S31 | 25, 3.6, 0, 100 | S29, S36 | 20, 3.6, 0, 100 | S37, S43 | 20, 2, 0, 100 |

| S24, S28 | 10, 4.2, 0, 100 | S30, S35 | 15, 2.2, 0, 70 | S37, S44 | 10, 2, 0, 70 |

| S24, S30 | 15, 4.4, 0, 100 | S30, S36 | 15, 3.6, 0, 100 | S38, S43 | 15, 2, 0, 80 |

| S24, S32 | 20, 2.7, 0, 100 | S30, S37 | 15, 4, 5, 80 | S38, S44 | 15, 4.5, 0, 100 |

| S25, S27 | 10, 3.4, 0, 100 | S31, S36 | 15, 2, 5, 80 | S39, H9 | 0, 020, 100 |

| S25, S29 | 15, 2.7, 0, 100 | S31, S37 | 10, 2, 0, 100 | S40, H10 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S25, S31 | 10, 3.6, 0, 100 | S31, S38 | 20, 2, 0, 70 | S41, H11 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S26, S28 | 15, 4.2, 0, 100 | S32, S37 | 20, 2, 0, 100 | S42, H12 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S26, S30 | 10, 4.4, 0, 100 | S32, S38 | 25, 2.5, 0, 100 | S43, H13 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S26, S32 | 5, 2.7, 0, 100 | S33, S39 | 15, 2, 0, 100 | S44, H14 | 0, 2, 0, 100 |

| S27, S33 | 10, 3, 5, 100 | S33, S40 | 10, 2, 0, 70 |

Metrics: delay (ms), security, jitter (ms), and bandwidth (Mbps).

References

- Xuan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, H.; Chung, I.; Wang, W.; Yang, W. Hierarchically Authorized Transactions for Massive Internet-of-Things Data Sharing Based on Multilayer Blockchain. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, L.; Oliveira, R.; Barcellos, M.; Gaspary, L.; Madeira, E. Virtual network security: Threats, countermeasures, and challenges. J. Internet Serv. Appl. 2015, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Liu, J.; Qi, C.; Wang, M.; Cheng, H.; Chen, J. RouteGuardian: Constructing secure routing paths in software-defined networking. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2017, 22, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallins, W. Software-Defined Networks and OpenFlow. Internet Protocol J. 2013, 16, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.A.; Wu, W.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Sasidharan, S.; DeMar, P.; Guok, C.; Macauley, J.; Pouyoul, E.; Kim, J.; et al. AmoebaNet: An SDN-enabled network service for big data science. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018, 119, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Fu, Q.; Xi, X.; Chen, Z.; Zou, E.; Fu, B. A policy conflict detection mechanism for multi-controller software-defined networks. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2019, 15:5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Lee, A.; Wang, P.; Luo, M.; Chou, W. A roadmap for traffic engineering in software defined networks. Comput. Netw. 2014, 71, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, D.; Ramos, F.; Verissimo, P.; Rothenberg, C.E.; Azodolmolky, S.; Uhlig, S. Software-Defined Networking: A Comprehensive Survey. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 14–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenFlow. Open Networking Foundation. Available online: https://www.opennetworking.org (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Isyaku, B.; Mohd Zahid, M.S.; Bte Kamat, M.; Abu Bakar, K.; Ghaleb, F.A. Software Defined Networking Flow Table Management of OpenFlow Switches Performance and Security Challenges: A Survey. Future Internet 2020, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, M.; Shrimankar, D.; Tembhurne, O. Controllers in SDN: A review report. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 36256–36270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Maashi, M.S.; Tanwar, S.; Badotra, S.; Aljebreen, M.; Bharany, S. A Comparative Study of Software Defined Networking Controllers Using Mininet. Electronics 2022, 11, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenDayLight Project. Available online: https://www.opendaylight.org (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Shin, G.Y.; Hong, S.S.; Lee, J.S.; Han, I.S.; Kim, H.K.; Oh, H.R. Network Security Node-Edge Scoring System Using Attack Graph Based on Vulnerability Correlation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common Vulnerability Scoring System SIG. Available online: https://www.first.org/cvss/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Yoon, S.; Cho, J.-H.; Kim, D.S.; Moore, T.J.; Free-Nelson, F.; Lim, H. Attack Graph-Based Moving Target Defense in Software-Defined Networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2020, 17, 1653–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.; Fuertes, W.; Arévalo, P.; Macas, M. An Environment-Specific Prioritization Model for Information-Security Vulnerabilities Based on Risk Factor Analysis. Electronics 2022, 11, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/EIC 27001 Information Security Management Homepage. Available online: https://www.iso.org/isoiec-27001-information-security.html (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- PILAR MAGERIT 3 Risk Management Methodology. Available online: https://pilar.ccn-cert.cni.es/index.php/en/methodology/pilar-methodology (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Egilmez, H.E.; Dane, S.T.; Bagci, K.T.; Tekalp, A.M. OpenQoS: An OpenFlow Controller Design for Multimedia Delivery with End-to-End Quality of Service over Software-Defined Networks. In Proceedings of the Signal & Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference, Hollywood, CA, USA, 3–6 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, H.; Durresi, A. Video over Software-Defined Networking (VSDN). In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Network-Based Information Systems, Gwangju, Korea, 4–6 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, M.; Gorkemli, B.; Tatlicioglu, S.; Komurcuoglu, M.; Karakaya, O. Quality of Service Control and Resource Priorization with Software Defined Networking. In Proceedings of the 1st IEEE Conference on Network Softwarization (NetSoft), London, UK, 13–17 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan, K.; Meng, K.; Ong, H.; Tat, W.M.; Sivanand, S.; Leong, L.S. Realizing the Quality of Service (QoS) in Software-Defined Networking (SDN) Based Cloud Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT), Bandung, Indonesia, 28–30 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tomovic, S.; Prasad, N.; Radusinovic, I. SDN control frame- work for QoS provisioning. In Proceedings of the IEEE 22nd Telecommunications Forum, Belgrade, Serbia, 25–27 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tajiki, M.M.; Akbari, B.; Shojafar, M.; Ghasemi, S.H.; Barazandeh, M.L.; Mokari, N.; Chiaraviglio, L.; Zink, M. CECT: Computationally efficient congestion-avoidance and traffic engineering in software-defined cloud data centers. Clust. Comput. 2018, 21, 1881–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioglu, E.D.; Kalipsiz, O. API Message-Driven Regression Testing Framework. Electronics 2022, 11, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniaș, O.; Florea, D.; Gyalai, R.; Curiac, D.-I. Automated Specification-Based Testing of REST APIs. Sensors 2021, 21, 5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coello, C.A.; Lamont, G.B.; Van Veldhuizen, D.A. Evolutionary Algorithms for Solving Multi-Objective Problems; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, M.; Shadkam, E.; Jahani, N. A hybrid COA/ϵ-constraint method for solving multiobjective problems. Int. J. Found. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mininet SDN Simulator. Available online: http://www.mininet.org (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Lee, G.M.; Ryu, D.K.; Park, G. Software-defined networking approaches for link failure recovery: A survey. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4255. [Google Scholar]

- IPERF Network Performance Tool. Available online: https://iperf.fr (accessed on 25 April 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).