Abstract

The main purposes of this paper are to offer a low-cost solution that can be used in engineering education and to address the challenges that Industry 4.0 brings with it. In recent years, there has been a great shortage of engineering experts, and therefore it is necessary to educate the next generation of experts, but the hardware and software tools needed for education are often expensive and access to them is sometimes difficult, but most importantly, they change and evolve rapidly. Therefore, the use of cheaper hardware and free software helps to create a reliable and suitable environment for the education of engineering experts. Based on the overview of related works dealing with low-cost teaching solutions, we present in this paper our own low-cost Education Kit, for which the price can be as low as approximately EUR 108 per kit, for teaching the basic skills of deep learning in quality-control tasks in inspection lines. The solution is based on Arduino, TensorFlow and Keras, a smartphone camera, and is assembled using LEGO kit. The results of the work serve as inspiration for educators and educational institutions.

Keywords:

low-cost; education; Industry 4.0; Arduino; Keras; LEGO; deep learning; inspection; machine vision; convolution neural network 1. Introduction

Experts in a number of academic and practical fields are required in today’s industry. Education institutions and colleges have been requested to integrate Industry 4.0 methods and features into present curricula to ensure that future graduates are not caught unawares by the industry’s changing expectations. Cyber-physical systems are just one of the numerous major change agents in engineering education [1].

Companies and higher education institutions recognize a need to teach employees digital skills and basic programming [2] as a result of new trends and the new capabilities demanded by the labour market [3]. Higher education has become more competitive between institutions and countries, and European universities have modified their teaching techniques [4] in order to create increasingly skilled workers in many fields of knowledge [2].

Nowadays, with the tremendous growth of Industry 4.0, the demands for product quality control and enhancement are continuously increasing. The aim of quality control is to objectively assess the conformity of a product to requirements, identify nonconformities, prevent the further advancement of defective products, and based on the processed inspection results, take steps to prevent errors in the production process. At the same time, Industry 4.0 brings opportunities to achieve these requirements. Among other things, it represents a major advance in process automation and optimization and the digitalization of data collection [5,6].

The transformation of data into digital form, brought about by Industry 4.0, was one of the fundamental factors that enabled the formation of Quality 4.0. Its use reduces errors, removes barriers to interoperability and collaboration, and simply enables traceability and further development. The basic tools of Quality 4.0 include the management and analysis of large volumes of data, the use of modern technologies (Internet of Things (IoT), Cloud computing), as well as machine vision applications with the support of deep learning [2,7].

Machine vision, as a new technology, offers reliable and fast 24/7 inspections and assists manufacturers in improving the efficiency of industrial operations. Machine vision has rapidly replaced human eyesight in many areas of industry, as well as in other sectors [8].

The data made available by vision equipment will be utilized to identify and report defective products, as well as to analyse the reasons for shortcomings and to enable prompt and efficient intervention in smart factories [9]. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Computer Vision as the smart technologies have received significant attention in recent years, mainly due to their contributions to Intelligent Manufacturing Systems [10]. Research activities have been conducted in recent years in order to introduce intelligent machine vision systems for defective product inspection, based on the exploitation of gathered information by various integrated technologies into modern manufacturing lines, using a variety of machine-learning techniques [11,12].

The application of machine vision with deep-learning support as an aforementioned Quality 4.0 tool represents a major shift in the quality monitoring of products in the production process, and is becoming the new prevailing trend of inspection [13]. Among other things, this approach brings [14]:

- The possibility of decentralized management and decision making,

- Increased system autonomy,

- Fast and stable identification of defective products independent of the user and the time of use,

- The ability to react flexibly when adjusting the controlled product,

- The ability to solve complex tasks,

- An all-in-one solution without the need for additional special HW or SW.

For this direction of quality control, which brings with it many advantages, to be further expanded, it is necessary to educate new generations of young engineers and experts in this field, who will build on the already-known information and further develop this direction. There are commercial systems that students could use during their studies to learn about this field, such as Cognex In-Sight D900 [15], which includes the deep-learning In-Sight ViDi [16] software (SW) from Cognex, but the price is quite high, so their application in the learning process is practically unrealistic. It is for this reason that we decided to prepare our own Education Kit, based on available and cheap hardware (HW) resources such as Arduino [17], LEGO [18] building set, smartphone camera, and open-source software tools such as Python [19], Tensorflow [20] and Keras [21], so that students can acquire basic skills using deep learning in quality control tasks on the model line.

The paper is organized into six sections: Section 2 deals with a deep overview of related work aimed at the need for education on Industry 4.0 technologies, low-cost solutions for modern technology education, Arduino-based low-cost solutions and LEGO-based low-cost solutions. Section 3 describes proposing of our low-cost education kit and its hardware and software parts. In Section 4, the results of experimental evaluations of the proposed education kit are presented. In Section 5, we discuss the evaluation of the results, possible improvements and limitations. In Section 6 we conclude the whole work.

2. Related Works

In this section, we will address the need to educate the next generation of engineering experts, of which there is still a shortage. We will also present several low-cost solutions that can be used in their training.

2.1. Urge for Education of Industry 4.0 Technologies

To teach interdisciplinary knowledge in engineering programs, research and computer laboratories must be updated. Complex modules must be incorporated in the process, as well as real-world components. Individual HW and SW modules for modelling, testing, and creation of optimal production lines, cognitive robots, communication systems, and virtual reality models to demonstrate functionality of individual processes but also to evaluate reconfiguration of processes and the impact of smart features and embedded control systems on the design of production processes, are examples of this trend in teaching processes in the automotive industry [22].

Universities highlight their position as testbeds for innovation and educators for future generations in developing future technologies. Traditional education has made a significant contribution to present levels of industrial development and technical progress. However, in order for higher education to provide future generations with the necessary skills and knowledge, it is critical to consider how the Fourth Industrial Revolution will effect higher education institutions [1]. As a result, one of the top concerns of colleges and academic institutions is to incorporate Industry 4.0 concepts into engineering curricula [23].

With sensors incorporated in almost all industrial components and equipment, ubiquitous cyber-physical systems, and analysis of all important data, Engineering 4.0 education [24] should focus on skills that lead to digitalization in the manufacturing sector [25]. New, multifunctional professions are required as a result of Industry 4.0. These new professionals will need to expand their understanding of information technology and the procedures in which it must and should be implemented [26]. According to the report “High-tech skills and leadership for Europe”, there was a deficit of 500,000 IT experts in Europe in 2020 [27].

Because of their contributions to Intelligent Manufacturing Systems, the Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision areas have grown in importance in recent years [10]. Smart factories require great precision and accuracy in the measurements and inspection of industrial gears as a result of technological advancements and the realizations of Industry 4.0. For such demanding applications, machine vision technology allows for image-based inspection and analysis. Human expertise in the area of computer vision is rapidly evolving. Visual sensors, unlike other types of sensors, can theoretically span the entire amount of information required for autonomous driving, registration of traffic violations, numerous medical duties, and so on, due to the fullness of image information. The demand for computer-vision specialists is increasing by the day. Simultaneously, it is important to educate the fundamentals of computer vision to specialists in application domains [28].

The Swedish initiative Ingenjör4.0 [29] represents an interesting education program. It is a unique, web module-based upskilling program developed in cooperation by 13 Swedish universities. The modules can be combined as the participant wishes, making it easy to customise the upskilling based on the unique needs of the company and individual. Ingenjör4.0 allows for a one-of-a-kind, innovative, large-scale, and life-long learning experience for industry professionals. It is aimed at professionals with an engineering background—but also at other professionals such as operators, technicians, management, etc., with an interest in smart and connected production.

2.2. Low-Cost Solutions for Modern Technology Education

In recent years, digitalization has played an increasingly essential role in solving these challenges and expectations in students’ education. Several studies say that the trend of digitalization in education is one of the most current solutions in the face of Industry 4.0 [30]. It is critical to offer courses aimed on Industry 4.0 technologies at a reasonable cost, as this is critical for students in nations where Industry 4.0 is developing with a lower quality and for the country overall. Many higher education institutions, faculties, and universities, have found a solution in the use of less expensive hardware, such as microcontroller platforms, sensors, and actuators, as well as software that can be used to program the hardware and is free for educational purposes [31], which can definitely help students in approaching programming industrial equipment and machines. Traditional hands-on laboratories are critical in engineering for students to learn engineering practical skills. However, due to a large number of students, economic factors (a significant number of resources, such as equipment and rooms, but also employees), or time constraints, it is not always possible to build as many practical sessions as the professors like [32].

This article [32] describes a student initiative to design and install a low-cost, machine vision-based, quality control system within a learning factory. A prototype system was created utilizing low-cost hardware and freely available open-source software.

The development and implementation of two experimental boards for the myDAQ are described in this paper [33], plus an experimental board for operational amplifiers and a single-quadrant multiplier. These two experimental boards increase the number of remote exercises available for electrical and electronic engineering instruction, making them an ideal complement to existing systems.

This study [32] proposes the usage of a remote laboratory assigned to online practical activities for students. The hands-on laboratory has a power system where the practical aspects of photovoltaic studies can be taught. Photovoltaic modules or a programmable source, a low-cost DC/DC buck-boost converter, and a load, make up the system. The online laboratory increases learners’ autonomy in conducting experiments and has a beneficial influence on students’ motivation [32].

Paper [34] describes the design of the FYO (Follow Your Objective) platform, a low-cost tangible programming platform made up of a physical intuitive programming board, puzzle-based tangible blocks, and a zoomorphic mobile robot that could be used to teach and improve programming skills in children as young as six years old. The preliminary trials and platform findings are analysed and presented; the results demonstrate that a physical puzzle-based platform can improve children’s programming skills.

In this work [35], an approach for emulating real-world embedded systems using low-cost, single-board computer hardware is given, allowing students to focus on the critical parts of system design. A customised teaching scenario that includes a laboratory vehicle built with low-cost hardware allows for practical teachings in the field of “Connected Car Applications” (Car2x). The evaluation results illustrate the practical viability, as well as its widespread acceptability and positive impact on learning success.

Authors in [36] believe that because of the rapid improvements in technology, educators are constantly challenged to come up with new and relevant laboratory projects. This can be a time-consuming and costly process that, if neglected, will result in out-of-date laboratory projects and a decline in student learning outcomes. They made a construction of three different laboratory projects created for electrical engineering students, exemplifying a technique that can handle this difficulty using low-cost modern technology and supervised student work.

The authors in [37] present the TekTrain project. It aims to create an innovative system that includes a highly customizable hardware platform as well as a dedicated software framework. TekTrain was created to help students improve their programming and technical skills while broadening their STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) knowledge. Its core competencies are modularity and the ability to integrate a wide range of sensors, all of which are adaptable to the needs of the user. The iterative procedure for developing the robotic platform that enables the execution of Internet of Things applications, as well as its features, are presented in this paper.

2.3. Arduino-Based Low-Cost Solutions

The use of a low-cost laboratory tool called Flexy2 for control education is described in this work [38]. A computer fan serves as an actuator, and a flexible resistor serves as a sensor, in this simple air-flow dynamical system. Flexy2 is intended to aid practical learning in courses involving automatic control and programming [38].

Arduino’s popularity has risen in recent years, mainly due to its role in the Internet of Things, which is having a significant impact across a variety of industries (industry, transportations, energy, agriculture, home automation, etc.). Several national and European programs have been established to train EU businesses on how to embrace and spread IoT technologies. In this paper, we explain the creation of an Arduino remote lab to support online, IoT-learning, experimentation environments, which are critical for providing high-quality IoT education programs [39].

The goal of this article [40] is to describe the design and construction of a low-cost laboratory plant for control system training. A DC motor with an incremental quadratic encoder is included in the equipment. To create a digital control system, the Arduino platform is used. Raspberry Pi may also be used to communicate with laboratory equipment and the REX Control System to create control algorithms.

Authors in [41,42] describe an experimental, Arduino-based, low-cost, self-balancing robot designed for control teaching at the University of Seville. The fundamental idea is that by building and controlling this robot, students may learn electronics, computer programming, modelling, control, and signal processing.

In paper [43], authors use the Arduino platform for their low-cost teaching devices such as the Thermo-opto-mechanical system TOM1A, a mobile robot of Segway type, an RC-circuit and D/A converter, for analysis of simple dynamical systems or the model of the hydraulic system with three connected tanks [43].

This study [44] presents a novel, open-source didactic device for control systems’ engineering education, which uses thermal control of a 3D printer heating block as the underlying dynamic process. The teaching aid is constructed on a printed circuit board that replicates the physical outline and standardized electrical connections of the Arduino Uno microcontroller prototyping board. The teaching tool described here can be produced at a low cost, making it available to students as a take-home experiment.

A new reference design for an air levitation system is presented in [45] in order to educate control engineering and mechatronics. The device is designed as a swappable and compact expansion shield for Arduino prototyping boards with embedded microcontrollers. To encourage quick and low-cost replication, the fully documented hardware design incorporates off-the-shelf electronic components and 3D printed mechanical elements, as well as editable design files available online.

Paper [46] describes an apparatus that fits on a standard expansion module format known as a Shield, and is compatible with a variety of microcontroller prototyping boards from the Arduino ecosystem. This low-cost, compact, repeatable, and open design is aimed at assisting control systems or mechatronics instruction through hands-on student experimentation or even low-cost research.

The well-known ball-on-beam laboratory experiment, in which a spherical ball without direct actuation is merely balanced by the inclination of a supporting structure, such as a beam, rail, or tube, is described in this article [47]. The design presented here is entirely open-source, relying on only a few off-the-shelf components and 3D printing to achieve an extremely cheap hardware cost. Furthermore, the final equipment fits on a standard extension module format known as a Shield, which is compatible with a variety of Arduino-compatible microcontroller prototyping boards

2.4. LEGO-Based Low-Cost Solutions

LEGO presents tools that encourage students to think creatively in a playful way. LEGO encourages children to think analytically because there are no rules, allowing the students to make their own. This improves the student’s problem-solving methods, organization, and preparation prior to construction [48].

A typical control systems laboratory usually costs thousands of dollars to set up. The use of LEGO NXT kits and ROBOTC software to teach a control systems laboratory to undergraduate engineering students is described in this study [49]. The gear and software together cost less than USD 350, making this a very cost-effective option for setting up a control systems laboratory.

The goal of this work [50] is to create a model that can emulate a human hand using LEGO Mindstorms EV3 as an educational tool for students. It would be exciting if students could design an exoskeleton system that met their needs. The use of LEGO as a platform can simplify and reduce the cost of explaining robotics, mechanical design, and biomedical applications.

2.5. Summary of Related Works

Based on an in-depth review of the literature, it can be stated that the use of low-cost equipment and the design of low-cost kits is a common thing in academic and university practice. The results of the survey confirm that it is possible to use low-cost equipment to teach high-tech technologies in the context of Industry 4.0. The use of hardware such as the Arduino or the LEGO kit has proven to be popular in academia. This inspired and encouraged us to create our own low-cost kit. In addition, we found that the topic we want to address (deep learning, machine vision, quality control) is not addressed in these works, and our kit can therefore be a benefit in this area.

The deep overview of the literature can also serve readers and especially university lecturers as a source of inspiration and encouragement for their future research or development of their own low-cost educational solutions. The rapid digitalisation of the industry urges the learning of new digital technologies, which is not limited to students at universities.

3. Materials and Methods

This part of the article will be devoted to the goals and tasks of our Education Kit, as well as their elaboration. We will present the design of the hardware part of the Kit and the software solution of the tasks that we have decided to solve with our Education Kit in the teaching process to begin with.

3.1. Goal and Tasks of Education Kit

Our goal was to design an Education Kit for the purpose of teaching machine vision with the support of deep learning, that would be simple, inexpensive, illustrative, easy to modify, and, most importantly, that students would enjoy working with it and that it would stimulate their desire for exploration. In proportion to this goal, we also decided to choose different levels of difficulty for the tasks:

- Simple binary classification task (checking the quality of the OK/NOK state of the product, while the trained convolutional neural network (CNN) knows both states),

- More complex one-class classification (OCC) task (quality control of the OK/NOK state of a product, where the trained convolutional neural network only knows the OK state and has to correctly distinguish all other products as NOK).

3.2. Preparation of the Hardware Part of the Education Kit

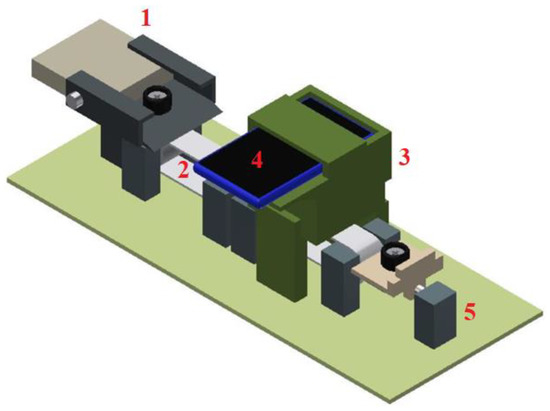

As we wanted to keep our kit simple in every way, the design of the production line made in the Inventor environment, which can be seen in Figure 1, was simple and easy to understand. The design consists of a loading slider (1) which is used to let the product onto the conveyor belt (2), then once the product on the belt reaches the camera tunnel (3), a signal is sent to the smartphone (4) to create an image which is further evaluated by the convolutional neural network in the computer, and based on the prediction of the convolutional neural network, the sorting mechanism (5) at the end of the line classifies the product.

Figure 1.

Design of the production line in Inventor: 1—loading slider, 2—conveyor belt, 3—camera stand in connection with the camera tunnel, 4—mobile, 5—sorting mechanism.

To ensure that the components for our Education Kit are simple and easily accessible we have chosen:

- LEGO building set for building the line,

- Arduino UNO for controlling sensors and actuators,

- A smartphone camera to capture images of products on the conveyor line.

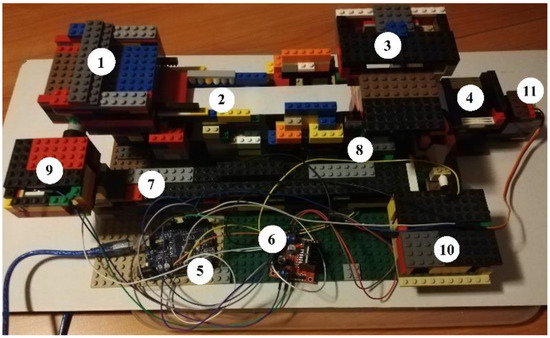

Starting from the proposed model of the production line and the selected components that should make up the line, we have created a model of the production line, which can be seen in Figure 2. The production line assembled from the LEGO building set consists of a loading slider (1), a conveyor belt (2), a camera stand in combination with a camera tunnel (3), a sorting mechanism (4), an Arduino UNO (5) for controlling the sensors and actuators, but also for communication with the computer, an H-bridge L298N (6) to control the motors of line, a battery pack (7) to power the line motors, an infrared (IR) obstacle sensor TCRT5000 (8) built into the leg of the camera tunnel to record the presence of the product in the camera tunnel, and servomotors controlling the line movements (9–11)—twice DS04 360 for the loading slider and conveyor belt and once FS90R for sorting mechanism.

Figure 2.

LEGO bricks production line—front view: 1—loading slider, 2—conveyor belt, 3—camera stand in connection with camera tunnel, 4—sorting mechanism, 5—Arduino UNO, 6—double H-bridge L298N, 7—battery pack, 8—infrared obstacle sensor TCRT5000, 9, 10—servomotors DS04 360, 11—servomotor FS90R.

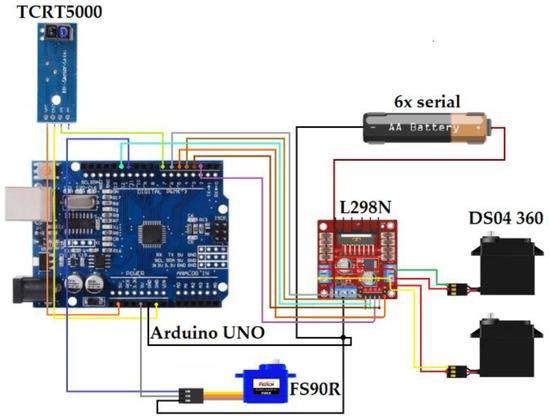

The components of our production line, such as Arduino UNO, H-bridge or IR sensor and servomotors, were chosen according to our experience that we have gained while studying and teaching how to work with different types of development boards. The Arduino UNO, as an open-source project created under The Creative Commons licenses [51] gives us the possibility to use any of its many clones at any time when we need to reduce the production costs of our Education Kit, which has been met with a positive response. The remaining components are commonly used during teaching and are thus familiar to students and available in stores selling Arduino accessories. The wiring diagram of the components connected to the Arduino can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Arduino wiring diagram.

3.3. Preparation of the Software Part of the Education Kit

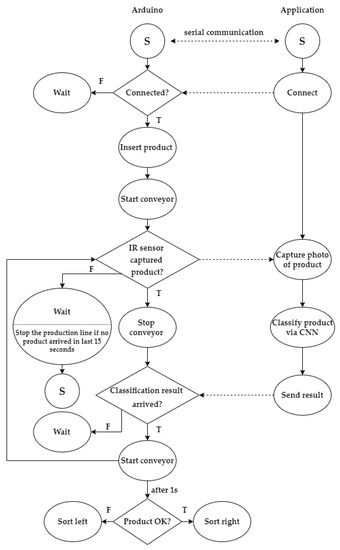

Before preparing the datasets and designing the convolutional neural network architecture, we designed a flowchart of the processes running on the line during production. The processes of the production line should simulate serial production and therefore they run in an infinite loop. We designed the process of production to stop the production line once no product arrived in front of the IR sensor in last 15 s. The process diagram, which can be seen in Figure 4, includes processes controlled by the Arduino, such as:

Figure 4.

Process diagram (dashed line—information flow).

- Opening and closing the loading slider, where after opening it is possible to insert the product into the production process,

- Operating the conveyor belt, ensuring the movement of the product through the production line and stopping the product in the camera tunnel after it has been detected by the IR sensor,

- Reading the value of the IR sensor,

- Sorting products with the sorting mechanism, used to separate OK and NOK products according to the result of convolutional neural network prediction.

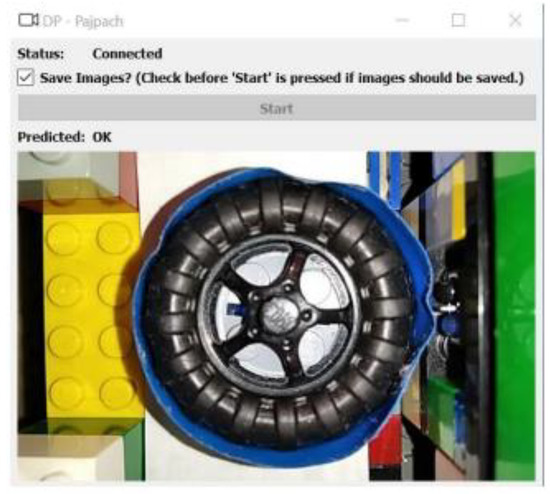

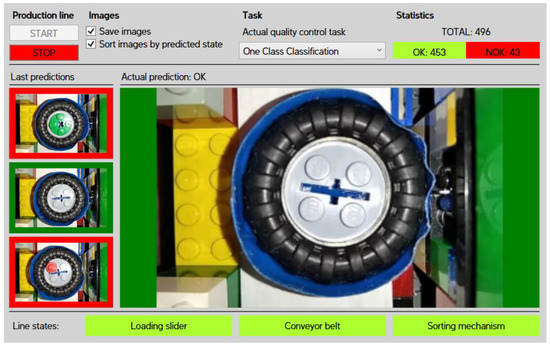

The diagram also includes processes controlled by an application written in Python, running on a computer that provides the user with a simple graphical user interface (GUI), shown in Figure 5 with the choice to save the snapshots, to display the product currently being evaluated, and to display the result of the prediction of the convolutional neural network.

Figure 5.

GUI of the application during product classification in the first task.

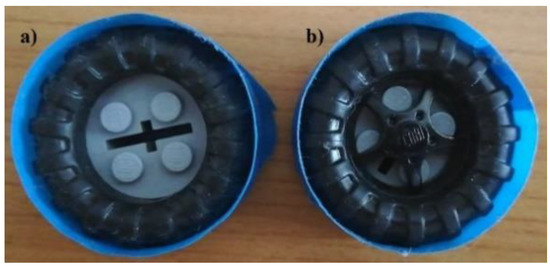

Since we decided to start with two tasks of different difficulty, it was necessary to specify the process for each task. For binary product classification, i.e., classification where the trained convolutional neural network can distinguish between just two known product types, the procedure is relatively straightforward. First, we needed to create a dataset of product images, which can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Products for the first task: (a) NOK (wheel without spoke), (b) OK (wheel with spoke).

Both products were photographed in the camera tunnel in different positions on the production line and with different rotation of the products. Subsequently, in order to increase the dataset size and improve the robustness of the neural network in future prediction, we applied brightness adjustment, Figure 7, and noise (Gauss, salt & pepper, speckle), Figure 8, to the images. The final dataset contained a total of 3000 images of both product states—OK and NOK, which were represented in the dataset in the ratio 50:50. Overall, 1920 images of the dataset were used for training, 600 for testing and the rest—480 images—were used for validation.

Figure 7.

Adjusting the brightness: (a) darkening, (b) lightening.

Figure 8.

Noise application: (a) Gaussian, (b) S&P, (c) speckle.

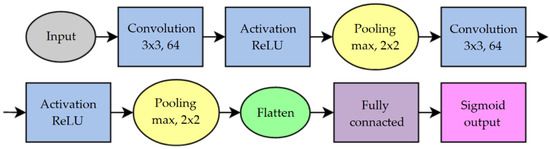

Next, we designed a convolutional neural network, whose block diagram can be seen in Figure 9, and according to the proposed architecture, we then built and trained a convolutional neural network model in Python containing two convolutional layers with ReLU activation functions, two max pooling layers, a flattening layer, a fully connected layer, and an output layer with a sigmoid-type activation function. The video example of Task 1 can be seen in [52].

Figure 9.

Block diagram of CNN architecture design for binary classification.

Before starting the training process, we set compile and fit parameters of our convolutional neural network to:

- Loss—binary crossentropy [53],

- Optimizer—adam [54],

- Batch size—32,

- Epochs—20,

- Validation split—0.2.

The summary of our convolutional neural network for the binary classification task can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of convolutional neural network for binary classification.

In the second task, product quality control using one-class classification will the trained convolutional neural network needed to be able to classify incoming products into two classes—OK (wheel without a spoke) and NOK (any other product). Figure 10 shows the OK products, marked by the yellow rectangle, and some of the many NOK products, marked by the red rectangle.

Figure 10.

Products for the second task: desired state—yellow rectangle, undesired state—red rectangle.

The process of preparing the dataset for training a convolutional neural network as well as designing the architecture of network itself is different from the previous task. In this task, we can only use the images of the products in the desired state from the camera tunnel, supplemented with brightness-adjusted images. The same as can be seen in Figure 7, to create the training dataset that consisted of 1150 images. With noise-added images, it is possible that we would introduce error into the resulting prediction during training. The images of the undesired states, along with a portion of the images of the desired states, are subsequently only used when testing the trained CNN. We also augmented the test dataset, some elements of which can be seen in Figure 11, with various other objects that the convolutional neural network must correctly classify as undesired states during testing. The final test dataset contained 1300 images, of which 200 were in the desired state and the rest in the undesired state.

Figure 11.

Different types of images found in the test dataset.

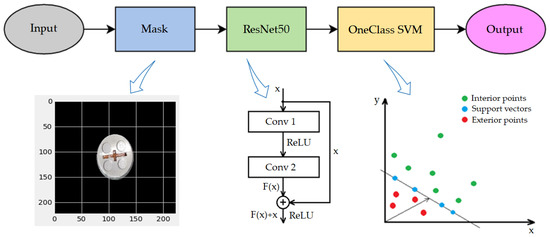

In designing the architecture of the convolutional neural network we adopted a procedure where first a mask is applied to the image to ensure the removal of the influence of the coloured parts of the LEGO building blocks from the background of the image. Then, the pretrained ResNet50, for which the architecture is described in [55], is used to extract features, and finally the output of ResNet50 is used as an input to the one-class support vector machine (OC-SVM) method. This provides a partitioning between the interior (desired) and the exterior (undesired) states based on the support vectors, for which optimal count needs to be found by fine-tuning the nu parameter of the OC-SVM method via grid search. The proposed architecture can be seen in Figure 12. A video example of Task 2 can be seen in [56].

Figure 12.

Proposed CNN architecture for one-class classification.

4. Experimental Results

Despite its simplicity, our illustrative and easy-to-modify Education Kit offers the student a variety of options for solving different tasks of machine vision with support of deep learning that can be simulated in the production process, including:

- Binary classification—convolutional neural network classifies just two types of products on the line,

- One-class classification—convolutional neural network distinguishes known OK states from NOK states,

- Multiclass classification—convolutional neural network classifies products into several known classes (the production line can be modified by modifying the sorting mechanism at the end).

When designing our Education Kit, we focused on making it simple, illustrative, and easy to modify, as well as inexpensive in terms of purchasing the components to build it. The estimated cost can be seen in Table 2 (not including the cost of the computer and mobile phone).

Table 2.

Cost of creating the Education Kit (not including the cost of the computer and mobile phone).

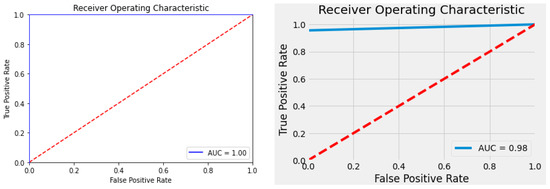

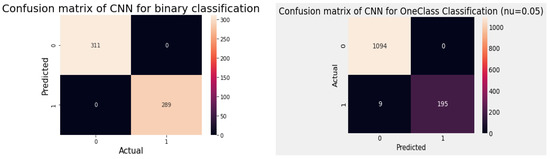

The results that can be achieved with our Education Kit, despite its simplicity, correspond in both tasks, as can be seen in Table 3—Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) scores and Figure 13—Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and Figure 14—confusion matrices, to a very accurate prediction.

Table 3.

Evaluation of CNN prediction accuracy for both tasks.

Figure 13.

ROC curves for both tasks (left curve—binary classification, right curve—one-class classification).

Figure 14.

Confusion matrices for both tasks (left matrix—binary classification, right matrix—one-class classification).

5. Discussion

The practical evaluation of the proposed education kit in the whole form (hardware and software) in the context of training and adaptability by the end users (students) was not able to performed because of pandemic restrictions (closed laboratories for education). The software part of the educational kit (dataset, proposing of CNN, experiments with dataset), however, is currently included in our education course “Machine vision and computational intelligence”, where students propose their own software quality evaluation solutions based on this kit. The education kit was presented during a lecture, and this topic was enjoyable for the students since they had unusual number of questions and showed interest in diploma theses in similar topics.

Individual types of occurred errors cannot be classified using the current dataset, which was designed for the second task. To do so, the training dataset would need to be augmented with images of specific possible occurred errors, and the task and the neural network architecture would need to be adapted to multiclass classification. Following that, we could improve our solution by adding the ability to mark the location of defects, which would help in detecting production errors. For example, if the error always occurred in the same location, we would know (if it is in the real production process) that these are not random errors and that we must check the previous processes on the line.

As can be seen in the confusion matrix for the second task, it would be possible to further work on CNN’s accuracy in recognizing OK products. To this end, it would be possible to extend the training dataset, where there would be various errors and defects on the inspected products. It could be possible to generate hundreds or even thousands of images of real damaged products. For this task, modern techniques such as real-time dataset generation by 3D modelling software (as Blender [64]) or 3D game engines (as Unity Computer Vision [65]) can be utilized. With such an augmented dataset, it would be possible to use other CNN structures aimed at recognizing the location of objects in the image (in our case, the location of defects and errors on the product) such as the architecture YOLO: You only look once [66], or SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector [67].

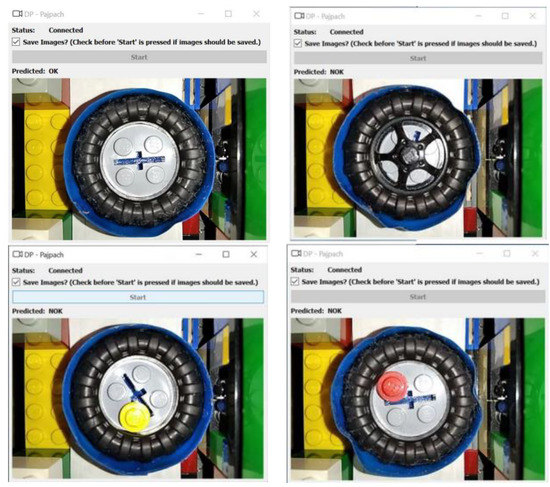

Python is a great programming language for working with images and creating and training convolutional neural networks, but it did not provide us with as many options when designing GUI. This deficiency could be remedied by using Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF), which gives the user a lot of freedom in designing the GUI window and is also more user-friendly. However, WPF is based on the NET platform, so we need to use one of the libraries that allow us to load a trained convolutional neural network from Python, such as ML.NET. ML.NET supports basic classifications such as binary and multiclass, allows loading pretrained neural networks, but also includes a model builder for creating and training neural networks. A GUI window design created in a WPF environment that could be used with ML.NET library can be seen in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

GUI window design in WPF environment.

Testing of the proposed convolutional neural networks in the production process of our production line was carried out in both tasks on 20 pieces of products that passed through the line. Examples of the testing for both tasks can be seen in the videos available on the link in the Supplementary Materials section. A sample of some of the testing results for the second task can be seen in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Results of testing CNN for second task—one-class classification.

6. Conclusions

This article deals with the proposal of a low-cost education kit aimed at selected digital technologies for Industry 4.0, such as convolutional neural networks, deep learning, machine vision and quality control.

Industry 4.0 brings with it many challenges and opportunities for young, enthusiastic engineers. However, in order to meet these challenges, they need to have a solid foundation in the field, and it is this foundation that the school can provide them with, where they have the opportunity to become acquainted with the issues and try solving various tasks in this area. However, solving the problems requires various hardware and software tools, which are often expensive, not always easy to access and need to be constantly improved as technology advances.

Universities emphasize their role as innovation testbeds and educators for future generations in the development of future technologies. Traditional education has contributed significantly to current levels of economic development and technological advancement. As a result, incorporating Industry 4.0 concepts into engineering curricula is one of the top priorities of academic institutions. Based on a review of the available literature and current research projects, it can be concluded that using low-cost equipment and designing low-cost kits is a typical occurrence in academic and university practice. The survey’s findings show that in the context of Industry 4.0, low-cost equipment can be used to educate high-tech technologies. In academics, hardware such as the Arduino or the LEGO kit have shown to be popular. We were motivated and encouraged to design our own low-cost kit as a result of this review. Furthermore, we discovered that the topics we wish to address (deep learning, machine vision, and quality control) are not covered in these works, indicating that our kit could be useful in these fields. The deep overview of the literature can serve readers as an inspiration for their future research or development of their own low-cost educational solutions. Moreover, the need for learning new digital technologies is not just for universities; it is necessary to cover the whole range of education levels from primary, secondary, and higher education to even postgraduate lifelong learning of professionals with an engineering background (e.g., following the Swedish Ingenjör4.0).

In this work, we presented our own design and implementation of a low-cost education kit. Based on the literature review, we have identified that current works and low-cost solutions do not address topics such as deep learning, convolutional neural networks, machine vision and quality control. This was an encouragement to create a new low-cost educational solution that could be an original solution and enrich the current state of the field. The kit is simple, illustrative, easy to modify, and interesting and appealing for students to work with, as it combines elements of electronics (Arduino), mechanics (production line), control (sensors and actuators), computer science (convolutional neural networks, GUI) and communication—the entire mechatronics spectrum. The Education Kit uses inexpensive and readily available components, such as the Arduino, the LEGO kit, and the smartphone camera, to ensure its modifiability and accessibility to schools. With our proposed Kit, various product quality control tasks can be solved using machine vision-supported convolutional neural networks, such as binary classification, multiclass classification, real-time YOLO applications, or one-class classification tasks, to distinguish a desired state from any other, undesired, state. The educational kit’s software component (dataset, CNN proposal, dataset experiments) is presently included in our education course “Machine vision and computational intelligence”, where students propose their own software quality-evaluation solutions based on this kit. The education kit was provided during a lecture, and the students found this topic to be interesting since they asked an uncommon number of questions and expressed interest in diploma thesis themes on similar issues.

The future developments of the educational kit can be achieved especially on the software side of the solution. The training dataset can be augmented with images of specific hypothetical faults, and the task and neural network architecture can be than changed to allow multiclass classification. Modern techniques, such as real-time dataset generation by 3D modelling software or 3D game engines, can be used for such dataset augmentation. Following that, we may expand our educational kit by allowing users to mark the location of faults.

We believe that our kit will become a quality learning tool in educating the next generation of young engineers, and will help them open the door to the world of Industry 4.0 technologies.

Supplementary Materials

Video examples can be found here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1psvumJAJmNU7LAPjgiwPiyzHSMzzeWR-?usp=sharing (accessed on 8 December 2021).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and O.H.; methodology, O.H.; software, M.P.; validation, O.H. and P.D.; resources, M.P., O.H., E.K. and P.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, O.H.; supervision, E.K. and P.D.; project administration, P.D.; funding acquisition, P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovak research and Development Agency under the contract no. APVV-17-0190 and by the Cultural and Educational Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic 016STU-4/2020 and 039STU-4/2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kozak, S.; Ruzicky, E.; Stefanovic, J.; Schindler, F. Research and education for industry 4.0: Present development. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Cybernetics and Informatics, K and I 2018, Lazy pod Makytou, Slovakia, 31 January–3 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A.F.; Gonçalves, M.J.A.; Taylor, M.D.L.M. How Higher Education Institutions Are Driving to Digital Transformation: A Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.; Haenlein, M. Rulers of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of artificial intelligence. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 63, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, D.; Salgado Sánchez, P.; Fernández, J.; Tinao, I.; Lapuerta, V. Challenge-Based Learning in Aerospace Engineering Education: The ESA Concurrent Engineering Challenge at the Technical University of Madrid. Acta Astronaut. 2020, 171, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagermann, H.; Wahlster, W.; Helbig, J. Final Report of the Industrie 4.0 Working Group; Federal Ministry of Education and Research: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 82, pp. 1–84.

- Lasi, H.; Fettke, P.; Kemper, H.-G.; Feld, T.; Hoffmann, M. Industry 4.0. Bus. Inform. Syst. Eng. 2014, 6, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saufi, S.R.; Bin Ahmad, Z.A.; Leong, M.S.; Lim, M.H. Challenges and Opportunities of Deep Learning Models for Machinery Fault Detection and Diagnosis: A Review. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 122644–122662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penumuru, D.P.; Muthuswamy, S.; Karumbu, P. Identification and classification of materials using machine vision and machine learning in the context of industry 4.0. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 1229–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.Y.; Xu, X.; Klotz, E.; Newman, S.T. Intelligent Manufacturing in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Review. Engineering 2017, 3, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierleoni, P.; Belli, A.; Palma, L.; Sabbatini, L. A Versatile Machine Vision Algorithm for Real-Time Counting Manually Assembled Pieces. J. Imaging 2020, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbarrad, T.; Salhaoui, M.; Kenitar, S.; Arioua, M. Intelligent Machine Vision Model for Defective Product Inspection Based on Machine Learning. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2021, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognex Corporation White Paper: Industry 4.0 and Machine Vision. Available online: https://www.cognex.com/resources/white-papers-articles/whitepaperandarticlemain?event=f6c6ef16-20ec-4564-bc74-7c42a9a4900a&cm_campid=a2f3e52b-c355-e711-8127-005056a466c7 (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Villalba-Diez, J.; Schmidt, D.; Gevers, R.; Ordieres-Meré, J.; Buchwitz, M.; Wellbrock, W. Deep Learning for Industrial Computer Vision Quality Control in the Printing Industry 4.0. Sensors 2019, 19, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cognex Corporation Deep Learning for Factory Automation Combining Artificial Intelligence with Machine Vision. Available online: https://www.cognex.com/resources/white-papers-articles/deep-learning-for-factory-automation (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Cognex Corporation In-Sight D900 Vision System In-Sight ViDi Detect Tool Analyzes. Available online: https://www.cognex.com/library/media/literature/pdf/datasheet_is-d900.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- Cognex Corporation In-Sight ViDi Detect Tool. Available online: https://www.cognex.com/library/media/literature/pdf/datasheet_is-vidi_detect.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Arduino.cc Arduino Uno Rev3 | Arduino Official Store. Available online: https://store.arduino.cc/products/arduino-uno-rev3/ (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Zosh, J.M.; Hopkins, E.J.; Jensen, H.; Liu, C.; Neale, D.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Solis, S.L.; Whitebread, D. Learning through Play A Review of the Evidence; LEGO Fonden: Billund, Denmark, 2017; ISBN 9788799958917. [Google Scholar]

- Millman, K.J.; Aivazis, M. Python for scientists and engineers. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2011, 13, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A system for large-scale machine learning. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, OSDI 2016, Savannah, GA, USA, 2–4 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Keras: The Python deep learning library. Astrophys. Source Code Libr. 2018, ascl-1806. [Google Scholar]

- Huba, M.; Kozák, Š. From e-Learning to Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the ICETA 2016-14th IEEE International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications, Proceedings, Košice, Slovakia, 24–25 November 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Leiden, A.; Posselt, G.; Bhakar, V.; Singh, R.; Sangwan, K.S.; Herrmann, C. Transferring experience labs for production engineering students to universities in newly industrialized countries. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 297, 12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Souza, R.G.; Quelhas, O.L.G. Model Proposal for Diagnosis and Integration of Industry 4.0 Concepts in Production Engineering Courses. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Assante, D.; Caforio, A.; Flamini, M.; Romano, E. Smart education in the context of industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 8–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sackey, S.M.; Bester, A. Industrial engineering curriculum in industry 4.0 in a South African context. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2016, 27, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolacu, M.; Svasta, P.M.; Berg, W.; Popp, H. Education 4.0 for tall thin engineer in a data driven society. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 23rd International Symposium for Design and Technology in Electronic Packaging, SIITME 2017-Proceedings, Constanta, Romania, 26–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Merkulova, I.Y.; Shavetov, S.V.; Borisov, O.I.; Gromov, V.S. Object detection and tracking basics: Student education. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Produktion2030 Ingenjör4.0. Available online: https://produktion2030.se/en/ingenjor-4-0/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Muktiarni, M.; Widiaty, I.; Abdullah, A.G.; Ana, A.; Yulia, C. Digitalisation Trend in Education during Industry 4.0. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujovic, A.; Todorovic, P.; Stefanovic, M.; Vukicevic, A.; Jovanovic, M.V.; Macuzic, I.; Stefanovic, N. The development and implementation of an aquaponics embedded device for teaching and learning varied engineering concepts. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 35, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.D.; Cano, J.M.; Vazquez, J.R.; López-García, D.A. A Low-Cost Remote Laboratory for Photovoltaic Systems to Explore the Acceptance of the Students. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Porto, Portugal, 27–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Klinger, T.; Kreiter, C.; Pester, A.; Madritsch, C. Low-cost Remote Laboratory Concept based on NI myDAQ and NI ELVIS for Electronic Engineering Education. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Porto, Portugal, 27–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Caceres, P.C.; Venero, R.P.; Cordova, F.C. Tangible programming mechatronic interface for basic induction in programming. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 17–20 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.; Bergande, B.; Seyser, D. Yes We CAN: A low-cost approach to simulate real-world automotive platforms in systems engineering education for non-computer science majors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 17–20 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bye, R.T.; Osen, O.L. On the Development of Laboratory Projects in Modern Engineering Education. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 8–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrios, S.; Fotios, G.; Emmanouil, S.; Areti, P.; Dimitris, R.; Christos, S.C. A novel, fully modular educational robotics platform for Internet of Things Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 1st Conference on Online Teaching for Mobile Education (OT4ME), Virtual, 22–25 November 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kalúz, M.; Klaučo, M.; Čirka, L.; Fikar, M. Flexy2: A Portable Laboratory Device for Control Engineering Education. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pacheco, A.; Martin, S.; Castro, M. Implementation of an arduino remote laboratory with raspberry pi. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 8–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Docekal, T.; Golembiovsky, M. Low cost laboratory plant for control system education. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, J.; Alvarado, I.; de la Peña, D.M. Low cost two-wheels self-balancing robot for control education powered by stepper motors. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 17518–17523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Alvarado, I.; Peña, D.M. La Low cost two-wheels self-balancing robot for control education. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 9174–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huba, M.; Bistak, P. PocketLab: Next step to Learning, Experimenting and Discovering in COVID Time. In Proceedings of the ICETA 2020-18th IEEE International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications, Košice, Slovakia, 12–13 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Takács, G.; Gulan, M.; Bavlna, J.; Köplinger, R.; Kováč, M.; Mikuláš, E.; Zarghoon, S.; Salíni, R. HeatShield: A low-cost didactic device for control education simulating 3d printer heater blocks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 8–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Takács, G.; Chmurčiak, P.; Gulan, M.; Mikuláš, E.; Kulhánek, J.; Penzinger, G.; Vdoleček, M.; Podbielančík, M.; Lučan, M.; Šálka, P.; et al. FloatShield: An Open Source Air Levitation Device for Control Engineering Education. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 17288–17295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, G.; Mihalik, J.; Mikulas, E.; Gulan, M. MagnetoShield: Prototype of a Low-Cost Magnetic Levitation Device for Control Education. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Porto, Portugal, 27–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Takacs, G.; Mikulas, E.; Vargova, A.; Konkoly, T.; Sima, P.; Vadovic, L.; Biro, M.; Michal, M.; Simovec, M.; Gulan, M. BOBShield: An Open-Source Miniature “Ball and Beam” Device for Control Engineering Education. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Vienna, Austria, 21–23 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abusobaih, A.; Havranek, M.; Abdulgabber, M.A. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) LEGO Sets in Education. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Information Technology, ICIT 2021-Proceedings, Amman, Jordan, 14–15 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wadoo, S.A.; Jain, R. A LEGO based undergraduate control systems laboratory. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Long Island Systems, Applications and Technology Conference, LISAT 2012, Farmingdale, NY, USA, 4 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Prituja, A.V.; Ren, H. Lego exoskeleton: An educational tool to design rehabilitation device. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Real-Time Computing and Robotics, RCAR 2017, Okinawa, Japan, 14–18 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arduino So You Want to Make an Arduino. Available online: https://www.arduino.cc/en/main/policy (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Video: Task 1-Low-Cost Education Kit. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zg2fDgxmjJrgdvptcWoYaNNW2-4IHG3R/view?usp=sharing (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Keras Probabilistic Losses. Available online: https://keras.io/api/losses/probabilistic_losses/#binarycrossentropy-class (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Keras Adam. Available online: https://keras.io/api/optimizers/adam/ (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Video: Task 2-Low-Cost Education Kit. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cdWCA8je7U-19vPTNSRAY8z87QIW0lKO/view?usp=sharing (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- LEGO Classic 10717 Bricks. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/LEGO-Classic-10717-Bricks-Piece/dp/B07G4R3HD5/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Arduino Uno REV3. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Arduino-A000066-ARDUINO-UNO-R3/dp/B008GRTSV6/ (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- L298N DC Stepper Motor Driver Module. Available online: https://www.ebay.com/itm/191674305541 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Duracell CopperTop AA Alkaline Batteries. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Duracell-CopperTop-Batteries-all-purpose-household/dp/B000IZQO7U/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- TCRT5000 Barrier Line Track Sensor. Available online: https://www.ebay.com/itm/264489365657?hash=item3d94cb7099:g:6KkAAOSwpKNdmbuS (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- KOOKYE Mini Servo Motor. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/KOOKYE-360-Continuous-Rotation-Helicopter/dp/B01HSX1IDE (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Feetech FS90R. Available online: https://www.ebay.com/itm/173052213397 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Blender. Available online: https://www.blender.org/ (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Borkman, S.; Crespi, A.; Dhakad, S.; Ganguly, S.; Hogins, J.; Jhang, Y.C.; Kamalzadeh, M.; Li, B.; Leal, S.; Parisi, P.; et al. Unity perception: Generate synthetic data for computer vision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.04259. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.04259 (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).