Abstract

Thanaka (H. crenulata, N. crenulata, L. acidissima L.) is a common tree in Southeast Asia used by the people of Myanmar to create their distinctive face makeup meant for daily sun protection and skincare. Moreover, it is used as a traditional remedy to treat various diseases since it can also be applied as an insect repellent. In this systematic review, the chemical and biological properties of Thanaka have been summarised from 18 articles obtained from the Scopus database. Various extracts of Thanaka comprise a significant number of bioactive compounds that include antioxidant, anti-ageing, anti-inflammatory, anti-melanogenic and anti-microbial properties. More importantly, Thanaka exhibits low cytotoxicity towards human cell lines. The use of natural plant materials with various beneficial biological activities have been commonly replacing artificial and synthetic chemicals for health and environmental reasons as natural plant materials offer advantages such as antioxidant, antibacterial qualities while providing essential nourishment to the skin. This review serves as a reference for the research, development and commercialisation of Thanaka skincare products, in particular, sunscreen. Natural sunscreens have attracted enormous interests as a potential replacement for sun protection products made using synthetic chemicals such as oxybenzone that would cause health issues and damage to the environment.

1. Introduction

Thanaka is a common tree that can be found around Southeast Asia. Scientific names of Thanaka include Hesperethusa crenulata (syn. Naringi crenulata) and Limonia acidissima L. It is native to the Republic of Myanmar, India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Java and Pakistan. Common names include Thanaka to the Burmese and belinggai in Malaysia. The Thanaka tree was first described by Talbot (1909) as “a spinous, glabrous, small tree” with straight thorns, smooth leaf stalk, with 5–7 leaflets where the edge of the leaf is crenulate (minutely scalloped). The leaflets are also described as non-scented when crushed. The fruits are oblong in shape, with black, smooth textured rind, with red/purplish-tinged flesh. Thanaka is a small tree that can grow to a height of 10 m, commonly grown on dry hills or in dry jungles. The stem is light yellow in colour, with a yellowish-grey, smooth and corky bark.

Thanaka tree is unique to the people of Myanmar where the yellowish powder ground from the tree bark has been used as traditional skincare and cosmetic product for over 2000 years. The earliest written evidence of the use of Thanaka in Myanmar can be found in a 14th century poem written by King Razadarit’s companion and in 15th century literature works of Shin Manaratthasara, a Burmese monk-poet. Artefact evidence of the kyauk pyin (round stone slab) was found after an earthquake in 1930 in the ruins of Shwemawdaw Pagoda. Kyauk pyin (round stone slab) is traditionally used to grind Thanaka bark powder and it was said to belong to the daughter of King Bayinnaug that ruled in the 15th century. Meanwhile, some believe that the history of Thanaka may date back more than 2000 years ago where the legendary queen of Peikthano, Queen Phantwar loved Thanaka. Peikthano is an ancient Pyu city and according to historians, the Pyu people intermarried with Sino-Tibetan migrants and subsequently became a part of the Burman ethnicity [1]. The legend of Queen Phantwar is always a favourite children’s bedtime story in Myanmar.

In Myanmar, the use of Thanaka bark powder is a part of their unique culture and the people are proud to wear the Thanaka paste made by mixing the Thanaka powder with water. The Burmese would grind the bark powder by using kyauk pyin with water to form a paste that gives a cooling sensation and a sandalwood-like fragrance. As an old Asian proverb goes: “The world’s most beautiful women have a Thai smile, Indian eyes and Burmese skin”. The Burmese have indeed been known for their beautiful skin and people believed that it is due to the benefits of wearing Thanaka paste as a traditional skin conditioner, which is thought to prevent acne, smoothen the skin as well as provide sun protection. Additionally, the Thanaka paste has also been used as a mosquito repellent. In addition, skin conditioning, the Burmese women also wear the Thanaka paste as makeup by drawing floral patterns as the paste would dry and remain as solid yellowish crusts after the liquid is absorbed into the skin (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Burmese women wearing Thanaka paste. (Picture was taken by LT Gew during her visit to Yangon, Myanmar.)

Various chemical and biological studies have been performed on the bark, leaf, fruit and seed of Thanaka from 1971 until the present time. Nayar, Sutar and Bhan (1971) and Nayar and Bhan (1972) identified an alkaloid 4-methoxy-1-methyl-2-quinolone(I), two coumarins suberosin and marmesin from the petrol extracts of H. crenulata [2,3]. Meanwhile, Joo et al. (2004) also found marmesin in methanol/chloroform (1:1) extract of Thanaka which comprise UV-absorbing chromophores that could absorb a wide range of UV-A radiation found in the chemical structure of marmesin [4]. Kim et al. (2008) found 3 tyramine derivatives, acidissimina A, acidissimina B and acidissimina B epoxide and 2 phenolic compounds, oxiranyl-(3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxy-phenyl)-methanol and oxiranyl-(3,4,5-trimethoxy-phenyl)-methanol in ethyl acetate extract of L. acidissima [5].

Based on the previous studies mentioned, polyphenol contents are commonly found in various Thanaka extracts. Polyphenol is a common class of non-volatile secondary plant metabolite used throughout the years for their potential health benefits which, depending on their chemical structures, may provide antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-carcinogenic properties that could help in the prevention of diseases. Among the sub-classes of polyphenols, coumarin is found to be commonly present in Thanaka extracts. Coumarin, or 2H-1-benzopyran-2-one, is part of a large class of phenolic substance made from fused α-pyrone rings and benzene [6]. At least 1300 different coumarins have been identified. These natural coumarins can be classified into six types, mainly simple coumarins, furanocoumarins, dihydrofuranocoumarins, pyranocoumarins, phenylcoumarins and bicoumarins [7]. Coumarins are characterised by UV-light absorption, which results in a characteristic blue fluorescent that is also photosensitive, easily altered by natural light [7,8]. Coumarins are also ascribed to many pharmacological activities such as anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-clotting, hypotensive and anti-cancer [7]. Thus, coumarins are used in many medicinal applications. Moreover, coumarin has a sweet odour that is similar to newly mown hay, resulting in its use in perfume formulations since 1882 [7]. Coumarins are also used in the formulations of skincare products such as aftershave lotions, cleansing products, moisturisers and sunscreen products.

In this review, the chemical and biological properties of Thanaka and its cosmeceutical applications have been summarised. The use of natural plant materials with various beneficial biological activities are now a trend in replacing artificial and synthetic chemicals for the regulation of health and environmental matters as natural plant materials offer advantages such as antioxidant, antibacterial qualities and providing essential nourishment to the skin. This review will serve as a reference for the development of skincare products containing Thanaka, particularly, sunscreen. Natural sunscreens have attracted enormous interests as the replacement of sun protection products made using synthetic chemicals such as oxybenzone that would not only cause health issues but also damage the environment such as water pollution and coral reef destruction.

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standard [9]. The guidelines helped in the selection of related and necessary information and enabled the evaluation and examination of the quality and meticulousness of the review.

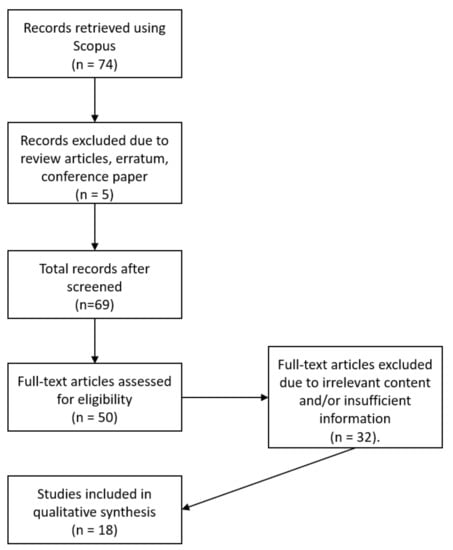

Resourcing of articles was conducted through the Scopus database in June 2020. The first stage of the systematic review process included the identification of keywords, followed by the searching process for related terms based on encyclopaedias and past research. In this case, the keywords used for this review were based on the common and scientific names of the plant of interest in order to perform a detailed review covering most aspects of this plant, using the search string as shown in Table 1. The contemporary result successfully retrieved a total of 74 records from the Scopus database.

Table 1.

Database Search string (SCOPUS).

Screening of the records was conducted to select suitable references. In this case, no duplication occurred hence the 74 records were further screened based on several inclusion and exclusion criteria. The first criterion was the article type which focused on primary source research articles. Hence, publications in the form of review, erratum and conference proceedings were excluded and, in this case, a total of five articles were excluded. It is worth mentioning that the systematic review only focused on articles published in English, while there was no limitation placed on the timeline due to the few publications retrieved. Most importantly, articles with full-text access were selected. Articles retrieved from the Scopus search were downloaded as full-texts through search engines such as Lancaster University OneSearch, Google Scholar, Elsevier and ResearchGate. Overall, a total of 50 articles were selected for the eligibility screening process.

For eligibility screening, the title, abstract and the main contents of all 50 articles were examined thoroughly to ensure that relevant and sufficient information fit the objectives of the review. Hence, 32 articles were excluded. Out of the 32 articles were excluded, 14 articles were not relevant to the topic in this manuscript and 13 articles had insufficient of information on Thanaka. Ultimately, the remaining 18 articles were selected for the qualitative synthesis as shown in Figure 2. The information tabulated in Table 4 was obtained through Google search engines and websites of the companies that manufacture Thanaka products in Southeast Asia.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the systematic review information adopted with modification from PRISMA.

3. Chemical Constituents and Phytochemical Screening of Thanaka

Table 2 showed the chemical constituents and phytochemical analysis of Thanaka. In 1971, Nayar et al. found that the alkaloid, 4-methoxy-1-methyl-2-quinolone, from the Thanaka stem bark petroleum extract, could be purified through chromatography on neutral alumina and crystallised for molecular structure identification using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [2]. Later in 1972, Nayar and Bhan used the same method as Nayar et al. 1971 and identified sitosterol in the petrol fraction, suberosin and 7-methoxy-6-(2,3-epoxy-6-methylbutyl) coumarin from petro-benzene (19:1) fraction, as well as 4-methoxy-1-methyl-2-quinolone, marmesin and suberenol from petrol-benzene (9:1) fraction [3]. Niu et al. (2001) extracted Thanaka stem bark powder using 70% acetone, crude resuspended in water and repeated extraction with ethyl acetate, followed by column chromatography over silica gel to form a fraction of chloroform, chloroform acetate (9:1 and 4:1) and acetone. Then, crystalline from the eluted fractions were characterised through optical rotation, IR spectra, UV spectra, mass spectrometry (MS) and NMR, to determine 21 bioactive compounds in Thanaka stem bark: alkaloids (crenulatine, n-benzoyltyramine methyl ether, tembamid, 4-Methoxy-6-hydroxy-1-methyl-2-quinolone), flavanones (2′,4′,5,7-Tetrahydroxyflavanone, 3,4′,5,7-Tetrahydroxyflavanone), aromatic compounds (syringlaldehyde, 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene), coumarins (7-hydroxycoumarin, angustifolin, pimpinellin, moellendorffilin), triterpenoid (lupeol), tetranortriterpenoids (limonexin, limonin, deacetylnomilinate), steroids (stigmast-4-en-6β-ol-3-one, schleicheol 2, 3 β-hydroxy-5α,8 α-epidioxyergosta-6,22-diene) and lignans (syringaresinol, lyoniresinol) [10]. In 2004, Joo et al. 2004 extracted Thanaka bark using methanol and chloroform (1:1, v/v) solvent, purified through silica gel chromatography, eluted with chloroform followed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) with 40:1 (v/v) of chloroform and methanol and further purified with silica gel chromatography [4]. The second TLC was carried out to obtain the fraction with the strongest fluorescence spots. The fraction chosen was further purified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to obtain the final dried crystallised active compound for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Joo et al. (2004) characterised the active compound as marmesin and identified that its structure was able to absorb a wide range of UV-A radiation [4]. Kim et al. (2008) conducted repeated column chromatography on ethyl acetate extracts of Thanaka bark and found 3 tyramine derivatives (acidissimina A, acidissimina B and acidissimina B epoxide) and two phenolic compounds (oxiranyl-(3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxy-phenyl)-methanol and oxiranyl-(3,4,5-trimethoxy-phenyl)-methanol) [5]. Sarada et al. (2011) identified 20 bioactive compounds (listed in Table 2) found in Thanaka stem bark ethanol extract, meanwhile,16 bioactive compounds (listed in Table 2) in Thanaka leaf ethanol extract through Gas chromatography Mass spectrometry (GC-MS), with 5 compounds in common including 3,5-dimethyl-Octane, 1,1,3-triethoxy-Propane, 3-ethyl-5-(2-ethylbutyl)-Octadecane, 9-hexyl-Heptadecane and 1,3,5-trimethyl-2-octadecyl-cyclohexane) [11]. Sampathkumar and Ramakrishnan (2012) identified 27 compounds (listed in Table 2) through GC-MS from Thanaka leaf ethanol extract prepared by hot extraction method using Soxhlet apparatus [12].

Some researchers conducted phytochemical analysis on the Thanaka extracts prior to mass spectrometry analysis or chromatography profiling. Sampathkumar and Ramakrishnan (2012b) conducted phytochemical analysis on the stem, bark and leaf of Thanaka extracted with ethanol reported that the ethanolic leaf extract results in the presence of proteins, lipids, phenols, tannins, flavonoids, saponins and quinones, while the ethanolic stem extract contains proteins, lipids, phenols, carbohydrate, reducing sugar, tannin, flavonoid, saponin and alkaloids; the ethanolic bark extract also reportedly contained almost the same contents as the stem extract except there was no alkaloid determined while triterpenoid and quinone were present in the bark extract [13]. Sampathkumar and Ramakrishnan (2012) then profiled the extracts of stem, bark and leaf using high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) and observed 10 peaks with Rf values in the range of 0.08 to 0.65 in stem ethanol extract; 8 peaks with Rf values in the range of 0.07 to 0.63 in bark ethanol extract; and 8 peaks with Rf values in the range of 0.09 to 0.49 in leaf ethanol extract. Pratheeba et al. (2019) reported that the phytochemical components of Thanaka leaf extracted with different solvents that varied between the hexane (non-polar) extract possess alkaloids, quinones and carbohydrates while ethyl acetate (slightly polar) extracts possess only saponins and carbohydrates. While methanol (polar) and acetone (polar) possess similar components (phenols, alkaloids, saponins, tannins and carbohydrates) except methanol extract possess extra components of proteins and flavonoids. They then conducted GC-MS analysis on the Thanaka fruit acetone extract and identified 8 compounds as listed in Table 2 [14]. Meanwhile, Vasant and Narasimhacharya (2013) conducted phytochemical analysis on petroleum ether extracts of Thanaka fruit and reported fibres (47 g/kg), phytosterols (38.7 g/kg), polyphenols (67.4 g/kg), flavonoids (0.6 g/kg), saponins (0.18 g/kg) and ascorbic acid (0.54 g/kg), however, they did not conduct any further MS analysis or profiling as their main objectives were to observe the regulating effects of Thanaka fruit in fluoride-induced hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia [15]. Coincidentally, Pandavadra and Chanda (2014) also conducted only phytochemical analysis without further MS analysis or profiling on the crude powder of Thanaka stem bark and leaf, reporting that the Thanaka crude stem bark powder contained alkaloids, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides, triterpenes and steroids while the Thanaka crude leaf powder contained alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, cardiac glycosides, triterpenes and steroids [16].

Among all the chromatography results, one common compound (Caryophyllene) was found in studies carried out by Sarada et al. (2011) and Pratheeba et al. (2019). However, the biological functions of the identified compounds in Table 2 were not discussed and investigated by the respective authors.

Table 2.

Chemical constituents and phytochemical analysis of Thanaka.

Table 2.

Chemical constituents and phytochemical analysis of Thanaka.

| Scientific Name and Parts | Solvent Extraction | Instrumental Analysis and Characterizations Tests | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem bark | Methanol and chloroform (1:1) Evaporated extract purified by silica gel chromatography, eluted with chloroform. | Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) performed with 40:1 mixture of chloroform and methanol. Further purification done through silica gel chromatography and 2nd TLC performed to obtain fraction with strongest fluorescence spots. Fractions then purified using reverse-phase High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and dried to obtain crystallized active compound by Mass Spectrometry (MS) analysis. | Active compound characterized as marmesin (2,3-dihydro-2-(1-hydrozy-1-methylethyl)-furanocoumarin), which tested to be able to absorb wide range of UV-A radiation (λmax at 335 nm). | [4] |

| Petroleum | Extract was purified by chromatography on neutral alumina, then rechromatography and recrystallization. Crystalline compound was analysed through nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. | Alkaloid compound identified as 4-methoxy-1-methyl-2-quinolone. | [2] | |

| Petroleum | Solvent chromatographed on neutral alumina.

Crystalline compounds were analysed through NMR spectroscopy. |

| [3] | |

| Extracted with 70% acetone to obtain the crude and suspended in water, then repeated extraction using ethyl acetate |

| Compounds identified:

N-Benzoyltyramine methyl ether Tembamid 4-Methoxy-6-hydroxy-1-methyl-2-quinolone

3,4′,5,7-Tetrahydroxyflavanone

1,3,5-Trimethoxybenzene

Angustifolin Pimpinellin Moellendorffilin

Limonin Deacetylnomilinate

Schleicheol 2 3 β-Hydroxy-5α,8 α-epidioxyergosta-6,22-diene

Lyoniresinol | [10] | |

| Ethanol | Gas chromatography Mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis | 20 phytocomponents identified in bark ethanolic extract, namely:

| [11] | |

| Ethyl Acetate | Column chromatography | Compounds identified:

| [5] | |

| Stem bark & Leaf | Crude powder, no extraction was performed. | Phytochemicals analysis | Phytochemicals found in Leaf: Alkaloids Flavonoids TanninsCardiac glycosides Triterpenes Steroids | [16] |

| Phytochemicals found in Stem bark: Alkaloids Flavonoids Cardiac glycosides Triterpenes Steroids | ||||

| Ethanol | Phytochemicals analysis | Present in leaf: Protein Lipid Phenol Tannin Flavonoid Saponin Quinone | [12] | |

| Present in stem: Protein Lipid Carbohydrate Reducing Sugar Phenol Tannin Flavonoid Saponin Alkaloid Present in bark: Protein Lipid Carbohydrate Reducing Sugar Phenol Tannin Flavonoid Saponin Triterpenoid Quinone | ||||

| High-performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC) profiling | Leaf 8 peaks with Rf values in the range of 0.09 to 0.49 Stem 10 peaks with Rf values in the range of 0.08 to 0.65 Bark 8 peaks with Rf values in the range of 0.07 to 0.63 | |||

| Leaf | Ethanol | GC-MS analysis | 16 phytocomponents in leaf ethanolic extract, namely

| [11] |

| Hot extraction method using Soxhlet apparatus by mixing powdered leaf in ethanol. | GC-MS analysis | 27 compounds identified in leaf extract, namely

| [13] | |

| Acetone | GC-MS analysis | 8 compounds were found, namely

| [14] | |

| Hexane Ethyl acetate Acetone Methanol | Phytochemical analysis | Hexane Alkaloids Quinones Carbohydrate Ethyl acetate Saponins Carbohydrates Acetone Phenols Alkaloids Saponins Tannins Carbohydrates Methanol Phenol Flavanoids Alkaloids Saponins Tannins Proteins Carbohydrates | ||

| Fruits | Petroleum ether | Phytochemical analysis Fibre content: Acid and alkaline treatment Phytosterol: Ferric chloride/sulfuric acid Saponin & Flavonoid: Vanillin/sulfuric acid Polyphenol: Folin-Ciocalteu Ascorbic acid content: 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine reagent | Fibres (47 g/kg) Phytosterols (38.7 g/kg) Polyphenols (67.4 g/kg) Flavonoids (0.6 g/kg) Saponins (0.18 g/kg) Ascorbic acid (0.54 g/kg) | [15] |

Unit (g/kg) expressed as gram per 1 kg of Thanaka fruit powder.

4. Biological Properties of Thanaka

4.1. Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidants, or free-radical scavengers, are substances that prevent or slow down the cell damage caused by free radicals, which is an unstable molecule produced by the body reacting to environmental stress, thus protecting human health [17]. Sources of antioxidants can be natural or artificial; however, natural sources of antioxidants from plants are generally preferred by people as they are believed to be safer. Polyphenols that can be found commonly in most plants are considered a highly effective antioxidant, as the structural chemistry of polyphenols derived from plants is ideal for scavenging free radicals, which have been shown to possess more effective antioxidants in vitro than vitamins E and C [17]. Antioxidants are also able to preserve food.

Total phenolic content (TPC) and diphenyl-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) are commonly employed to determine the antioxidant activities of plant extracts using spectrophotomer. The amount of phenolic content of the plant extract is evaluated using the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method. The commonly used standards are gallic acid, pyrocatechol and tannic acid. The DPPH assay is widely used to antioxidant activities by measuring the total radical scavenging capacity of antioxidants toward the stable free-radical, subsequently reacts with hydrogen donor compounds.

Antioxidant activities of Thanaka extracts were evaluated by several scientists as mentioned in Table 3. In particular, Wangthong et al. in 2010 evaluated various extracts of Thanaka stem bark using different solvents including hexane, methanol, ethyl acetate, 85% aqueous ethanol and water. Through DPPH antioxidant assay, they found that the 85% ethanol extracts of Thanaka stem bark possessed the highest antioxidant activity while hexane had the lowest activity [18]. They also evaluated the TPC in the Thanaka stem bark extracts where the methanol extracts possessed the highest amount of TPC while hexane extract possessed the lowest TPC amount. In 2012, Shermin et al. also performed a DPPH antioxidant test on Thanaka stem bark extracts of different solvents including chloroform, petroleum ether and methanol. The results showed that the chloroform extract possessed the highest antioxidant activity followed by petroleum ether, then methanol [19]. In 2017, Sonawane and Arya evaluated the antioxidant activity of the protein hydrolysates obtained from Thanaka seeds through DPPH, 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) and metal chelating ability assay. They found that the DPPH assay was not suitable for protein hydrolysates, while in FRAP assay the absorbance reading did increase as the concentration of protein hydrolysates increased; however, the results are lower compared to the Trolox standard. In ABTS assay and metal chelating ability assay, the relationship between the concentration of protein hydrolysates and antioxidant activity was linear and the antioxidant activity was observed to be higher than Trolox standard [20]. Later in 2020, Sonawane et al. tested Thanaka seed protein hydrolysates in storage and colour stability of anthocyanins. They reported that the storage stability of anthocyanin slightly increased by 10 h and 34 min at 0.12% protein hydrolysate concentration but decreased at a higher concentration by 2%, while the colour stability of anthocyanin increased as the concentration of Thanaka seed protein hydrolysates increased [21]. In 2018, Jantarat et al. formulated four herbs including Thanaka bark powder into an herbal ball and tested for its antioxidant activity through DPPH assay resulting in antioxidant activity lower than the gallic acid standard by 40-fold [22].

Table 3.

Biological activities of Thanaka.

4.2. Antimicrobial Activity

It is worth mentioning that traditionally Thanaka is used as an acne treatment remedy as well as an antifungal. This resulted in scientists’ enthusiasm to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of Thanaka. Wangthong et al. (2010) did both minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) assay by treating various solvent extracts of Thanaka stem bark onto Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli (E. coli) and by using clindamycin as the standard. The results showed that all extracts possessed a slight antibacterial activity that is 10-to-20-fold lower against E. coli and 300-folds lower against S. aureus when compared with the clindamycin standard [18]. Interestingly, the herbal ball comprised of four herbs, i.e., Andrographis paniculata, Centella asiatica, Benchalokawichian and Thanaka bark powder was prepared by Jantarat et al., 2018, showed antibacterial activity against Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) at a concentration of 31.25 μg/mL in both MIC and MBC assay [22].

4.3. Cytotoxicity and Cell Viability

Since it is a traditional remedy that is used on the skin, it is important to know the cytotoxicity of Thanaka to determine the safety of use. Wangthong et al. in 2010 evaluated both cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of Thanaka stem bark extracts on the human melanoma A-375 cell line. According to their observation, the original bark powder did not show any signs of cytotoxicity towards the A-375 cells, while the water, methanol and 85% ethanol extracts showed very low cell cytotoxicity. However, ethyl acetate, hexane and dichlromethane showed slightly higher cytotoxicity against A375 cells but overall, much lower than the doxorubicin standard. As for genotoxicity, Wangthong et al., 2010 claimed that all extracts and original bark powder exhibited no genotoxicity [18]. Ma et al. (2020) evaluated the cytotoxicity of Thanaka leaf extract mediated tin (IV) oxide nanoparticles (SnO2 NPs) against human cervical cancer (SiHa) cell line and resulted in the cell viability of SiHa cells to reduce as the concentration of Thanaka leaf extract mediated SnO2 NPs increased. They also assessed the morphology of the SiHa cell to observe for cell apoptosis. SiHa cells displayed the existence of necrotic and apoptotic cell morphology after treating the SiHa cells with the Thanaka leaf SnO2 NPs for 24 h [23].

Additionally, toxicity model such as Artemia salina (A. salina) brine shrimp and Culex quinquefasciatus (C. quinquefasciatus) mosquito larvae were employed in cytotoxicity screening of Thanaka extracts [14,19]. Shemin et al. (2012) evaluated the cytotoxicity of Thanaka stem bark extracts on brine shrimp A. salina and observed that there is slightly higher cytotoxicity in petroleum ether and chloroform extracts, while very low cytotoxicity was observed in methanol extract; however, the cytotoxicity of all extracts is much lower than the vincristine sulphate standard [19]. Pratheeba et al. (2019) evaluated the larvicidal efficacy activity of various Thanaka leaf extracts against C. quinquefasciatus. A higher mortality rate was observed in C. quinquefasciatus larvae at 24 h post-treatment with acetone extract of Thanaka leaf with lethal concentration 50 (LC50) and lethal concentration 90 (LC90) values as low as 1.02 mg/L and 1.93 mg/L respectively, followed by methanol extract with 1.13 mg/L LC50 and 2.24 mg/L LC90 values, ethyl acetate extract with 1.81 mg/L LC50 and 4.14 mg/L LC90 and hexane extract with 9.74 mg/L LC50 and 2.34 mg/L LC90 [14].

4.4. Other Biological Properties

Since Thanaka bark powder has been traditionally used for UV-protection and skin conditioning by the Burmese, it encouraged scientist to evaluate its tyrosinase inhibition activity. Tyrosinase is a copper-containing enzyme that is recognised for melanogenesis and pigmentation activity [25]. Therefore, tyrosinase inhibition activity is important to prevent forming of pigments on the skin. Wangthong et al. (2010) evaluated the tyrosinase inhibition activity of the Thanaka stem bark extracts. The overall tyrosinase inhibition activity of Thanaka stem bark extracts and pure powder are mild when compared with the Kojic acid standard; however, when compared among the various Thanaka extracts, dichloromethane extract had the highest tyrosinase inhibition activity, whereas methanol had the lowest tyrosinase inhibition activity [18].

The anti-inflammatory activity of the Thanaka stem bark extracts was also evaluated by Wangthong et al. (2010). Inflammation is a response pattern of the body towards injury or allergens that involves the accumulation of cells and exudates in irritated tissues to prevent and protect from further damage. However, inflammatory reactions cause pain, redness, swelling and heat to the body; hence, the role of anti-inflammatory activity is important in relieving these symptoms. The anti-inflammatory activity of various Thanaka stem bark extracts was performed in the murine macrophage-like cell line RAW 264.7 using the stem bark extracts and they observed that all extracts possessed an 80–90% high anti-inflammatory activity at non-toxic dosages (80% cell viability) ranked in the order: Hexane > dichloromethane > ethyl acetate > 85% ethanol > methanol > water. Hence, it is proven that the stem bark extracts of Thanaka possess high anti-inflammatory activity and a mild level of tyrosinase inhibition activity [18].

Vasant and Narasimahcharya (2013) experimented on the ability of petroleum ether extract of Thanaka fruit powder on the regulation of fluoride-induced hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia in colony-bred male albino rats. Hyperglycaemia is the condition of high glucose level circulating in the blood and when persistently high, may cause diabetes while hyperlipidaemia is the condition of elevation of cholesterol or triglycerides in blood circulation, both conditions are menacing to health. In rat groups fed with Thanaka fruit powder (2.5 g/kg in feed, 5 g/kg in feed, 10 g/kg infeed), it showed dose-dependent significant results in the decrease of plasma glucose levels, G-6-Pase activity, plasma total lipid (TL), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C), apolipoprotein (AI) content and hepatic lipid profiles, while an increase in plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) content is also observed [15]. Therefore, the petroleum ether extract of Thanaka fruit extract can regulate hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia conditions.

Wound healing activity of Thanaka leaf biomolecules coating silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) was also evaluated by Bhuvaneswari et al. (2014) on Wistar male albino rats and compared with standard drug Betadine [24]. Silver nanoparticles are antimicrobial agents that have been used in skin ointments and creams to deliver extensive applications to prevent infection of burns and open wounds [26]. The results showed that the Thanaka leaf AgNPs had higher wound healing activity than the standard drug betadine [24]. However, the authors did not compare the Thanaka leaf AgNPs healing effect with only Thanaka leaf extract; therefore, no conclusions could be made as to whether the wound healing is mainly because of the silver nanoparticles or if the Thanaka extract boosted the healing effect of AgNPs or both.

5. Cosmeceutical Products Containing Thanaka in the Southeast Asia Market

In Table 4, we tabulated the Thanaka cosmetic products that are manufactured and sold in Southeast Asian countries such as Myanmar, Thailand and Malaysia. Notable brands, namely, Shwe Pyi Nann [27] and Truly Thanaka [28] from Myanmar, Suppaporn [29] and De Leaf [30] from Thailand, Thanaka Malaysia [31] and Bio Essence [32] from Malaysia are commonly found over the counter in shopping malls and pharmacies as well as online. Local brands from Myanmar (snake brand, Pann Chit Thu, Myat Bhoon Pwint), Malaysia (Taté Skincare Malaysia [33]) are also producers of Thanaka cosmeceutical products.

Table 4.

Some of Thanaka products in the market in Southeast Asia.

Shwe Pyi Nann Co. Ltd. is the leading manufacturer and exporter of Thanaka to Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines, which lead to the production of Thanaka products in Thailand and Malaysia. Companies manufacturing Thanaka products are mainly found in Southeast Asia since Thanaka bark thrives in the hot weather of countries located near the equator, where sunlight is more intense as compared to other parts of the Earth. Thus, in order to protect our skin from harmful UV rays, the demand for sunblock products and after-sun treatment is essential in Southeast Asian countries.

The Burmese apply Thanaka powder directly onto their skin as sunscreen. However, the yellow patches left on the cheek (Figure 1) are not widely accepted by other countries except Myanmar. Hence, to benefit more people with the natural sunscreen, Thanaka skincare products such as soap, loose powder, foundation powder, face scrub, body lotion and face scrub are produced. In order to meet the consumers and market demand, Thanaka is also formulated into cleanser, serum, moisturiser, acne spot treatment cream and tone up cream. Most of the manufacturers add active ingredients such as vitamins, collagen and hyaluronic acid to increase the synergic effect and provide treatment to various skin conditions. Some of the products of Shwe Pyi Nannare are enhanced with the scent of flowers and herbs to make the products appear more attractive to consumers. In general, a scent is added to the beauty product to neutralise the unpleasant odour of its ingredients.Brands such as Truly Thanaka, de Leaf and ThanakaMalaysia produce Thanaka products containing vitamins A, C and E, collagens, 24 k gold, hyaluronic acid, aloe vera, turmeric, glutathione, jasmine rice and pomegranate powder that beneficial to the skin, such as protect our skin from environmental damage such as pollution, improve our skin condition and help to fight the effects of ageing such as wrinkles and pigmentation. Furthermore, quality ingredients such as bamboo charcoal were added as an exfoliator, meanwhile, kaffir lime and honey were added to enhance the cleansing effect and body brightening.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Thanaka has been used as the traditional skincare by the people of Myanmar for over 2000 years due to the belief in its anti-ageing, acne-clearing and sun protecting benefits. The people in Southeast Asia also use it as a traditional remedy for various purposes such as insect repellent and wound healing. Among its renowned benefits, its antioxidant, anti-bacterial and cytotoxicity are the most studied properties using various Thanaka extracts. The phytochemical analysis is among the favourite method by scientists to discover the natural bioactive compounds in Thanaka.

Although the extensive chromatography analysis of Thanaka was performed on extracts of various solvents, the authors did not further discuss the biological functions of each compound in most of the publications reviewed in Table 2. Conversely, most of the biological assays were performed using extracts of Thanaka without further isolation of pure bioactive compounds from the extracts (Table 3). This gap could be improved by collaboration between chemists and biologists in the discovery of bioactive compounds in natural products. Moreover, most authors utilised organic solvents such as hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, ethanol and methanol (Table 3) to perform the extraction. Wangthong et al. (2010) mentioned that the solubility of extracts and toxicity of organic solvents may affect the accuracy of results as most of the biological assays use polar buffer solutions [18]. Thus, the use of green solvents (such as glycerol) in extracting bioactive ingredients may be a good alternative to organic solvents in the extraction of natural products, particularly, in the development of skincare products. The development of green skincare products will significantly prevent users from experiencing any allergic skin reactions. Furthermore, green solvents require minimum waste management. It is hoped that this review may serve as a reference that will lead to new scientific discoveries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W.L., L.T.G. and M.K.A.; methodology, L.T.G.; original draft preparation of the manuscript, M.W.L. and L.T.G.; review and editing the manuscript, L.T.G. and M.K.A.; supervision, L.T.G.; funding acquisition, L.T.G. and M.K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) (Grant no.: FRGS/1/2020/STG01/SYUC/02/1) awarded by Ministry of Education Malaysia (MOE).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledged Sunway Postgraduate Research Scholarship (PGSUREC2020/006) which was granted to MW Lim by Sunway University, Malaysia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Yeni. Beauty That’s More Than Skin Deep. 2011. Available online: https://www2.irrawaddy.com/article.php?art_id=21842 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Nayar, M.N.S.; Sutar, C.V.; Bhan, M.K. Alkaloids of the stem bark of Hesperethusa crenulata. Phytochemistry 1971, 10, 2843–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayar, M.; Bhan, M.K. Coumarins and other constituents of Hesperethusa crenulata. Phytochemistry 1972, 11, 3331–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.H.; Lee, S.C.; Kim, S.K. UV absorbent, marmesin, from the bark of Thanakha, Hesperethusa crenulata L. J. Plant Biol. 2004, 47, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Yang, M.C.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, I.K.; Ha, S.K.; Choi, P.; Bae, W.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, K.R. Three new tyramine and two new phenolic constituents from Limonia acidissima. Planta Med. 2008, 74, PB116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, Y.; Katayama, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Tanaka, H.; Kon, K. A new antitumor antibiotic product, demethylchartreusin isolation and biological activities. J. Antibiot. 1992, 45, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matos, M.J.; Santana, L.; Uriarte, E.; Abreu, O.A.; Molina, E.; Yordi, E.G. Coumarins—An important class of phytochemicals. Phytochem. Isol. Characterisation Role Hum. Health 2015, 25, 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanachi, A.; Leonetti, F.; Pisani, L.; Catto, M.; Carotti, A. Coumarin: A natural, privileged and versatile scaffold for bioactive compounds. Molecules 2018, 23, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.M.; Li, S.H.; Peng, L.Y.; Lin, Z.W.; Rao, G.X.; Sun, H.D. Constituents from Limonia crenulata. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2001, 3, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarada, K.; Margret, R.J.; Mohan, V. GC-MS Determination of bioactive components of Naringi crenulata (Roxb) Nicolson. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2011, 3, 1548–1555. [Google Scholar]

- Sampathkumar, S.; Ramakrishnan, N. GC-MS analysis of methanolic extract of Naringi crenulata (Roxb.) Nicols. stem. J. Pharm. Res. 2012, 5, 1102–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Sampathkumar, S.; Ramakrishnan, N. Pharmacognostical analysis of Naringi crenulata leaves. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, S627–S631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratheeba, T.; Vivekanandhan, P.; Faeza, A.N.; Natarajan, D. Chemical constituents and larvicidal efficacy of Naringi crenulata (Rutaceae) plant extracts and bioassay guided fractions against Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 19, 101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasant, R.A.; Narasimhacharya, A.V. Limonia fruit as a food supplement to regulate fluoride-induced hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandavadra, M.; Chanda, S. Development of quality control parameters for the standardization of Limonia acidissima L. leaf and stem. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, S244–S248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.; Miller, N.; Paganga, G. Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangthong, S.; Palaga, T.; Rengpipat, S.; Wanichwecharungruang, S.P.; Chanchaisak, P.; Heinrich, M. Biological activities and safety of Thanaka (Hesperethusa crenulata) stem bark. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 132, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shermin, S.; Aktar, F.; Ahsan, M.; Hasan, C.M. Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activitiy of Limonia acidissima L. Dhaka Univ. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 11, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, S.K.; Arya, S.S. Bioactive L acidissima protein hydrolysates using Box-Behnken design. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, S.K.; Patil, S.; Arya, S.S. Effect of protein hydrolysates from Limonia (L.) acidissima and Citrullus (C.) lanatus on anthocyanin degradation. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20 (Suppl. 2), S231–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantarat, C.; Sirathanarun, P.; Chuchue, T.; Konpian, A.; Sukkua, G.; Wongprasert, P. In vitro antimicrobial activity of gel containing the herbal ball extract against Propionibacterium acnes. Sci. Pharm. 2018, 86, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, C.; Wu, X.; Yang, G. Synthesis of L. Acidissima mediated tin oxide nanoparticles for cervical carcinoma treatment in nursing care. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 101745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuvaneswari, T.; Thiyagarajan, M.; Geetha, N.; Venkatachalam, P. Bioactive compound loaded stable silver nanoparticle synthesis from microwave irradiated aqueous extracellular leaf extracts of Naringi crenulata and its wound healing activity in experimental rat model. Acta Trop. 2014, 135, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merimsky, O.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Fishman, P. A focus on anti-tyrosinase antibodies in melanoma and vitiligo. Decade Autoimmun. 1999, 261, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Durán, N.; Marcato, P.D.; Alves, O.L.; De Souza, G.I.; Esposito, E. Mechanistic aspects of biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by several Fusarium oxysporum strains. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2005, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanaka Shop. Available online: https://www.thanakashop.com/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Truly Thanaka. Available online: https://www.trulythanaka.com/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Supaporn Group. Available online: https://supapornherb.com/en (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- De Leaf. Available online: https://deleafthanaka.com/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Thanaka Malaysia. Available online: https://thanakamalaysia.com.my/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Bio essence. Available online: https://bio-essence.com.my/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Taté Skincare Malaysia. Available online: http://tateskincare.blogspot.com/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).