Abstract

Introduction: Artificial intelligence (AI) has developed into an increasingly important tool in dermatology. While new technologies integrated within laser devices are emerging, there is a lack of data on the applicability of publicly available AI models. Methods: The prospective study used an online questionnaire where participants evaluated diagnosis and treatment for 25 dermatological cases shown as pictures. The same questions were given to AI models: ChatGPT-4o, Claude Sonnet 4, Gemini 2.5 Flash, and Grok-3. Results: Dermatologists outperformed AI in diagnostic accuracy (suspected primary diagnosis-SD 75.6%) in pooled dermatologists vs. pooled AI (SD 57.0%), with laser specialists achieving the highest accuracy (SD 82.0%) and residents the lowest (SD 66.0%). There was a high heterogeneity across AI models. Gemini approached dermatologist performance (SD 72.0%), while Claude showed a low accuracy (SD 40.0%). While AI models reached near 100% accuracy in some classic/common diagnoses (e.g., acne, rosacea, spider angioma, infantile hemangioma), their accuracy dropped to near 0% on rare or context-dependent cases (e.g., blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, angiosarcoma, hirsutism, cutaneous siderosis). Inter-rater agreement was high among laser experts in terms of diagnostic accuracy and treatment choice. Agreement between residents and AI models was highest for diagnostic accuracy and treatment choice, while it was lowest between experts and AI models. Conclusions: Before AI-based tools can be integrated into daily practice, particularly regarding diagnosis and appropriate laser treatment recommendations, specific supervised medical training of the AI model is necessary, as open-source platforms currently lack the ability to contextualize presented data.

1. Introduction

Currently, artificial intelligence (AI) is primarily used to enhance diagnostic accuracy and support clinical decision-making. Among various implementations across medical specialties, the most widely used application is visual pattern identification as utilized in medical imaging [1,2,3]. Improvements in AI image classification and analysis have enabled the application of AI in dermatology, most importantly in melanoma detection [4,5,6,7]. There have been numerous efforts towards investigating the diagnostic performance of AI in comparison to that of physicians [7,8,9,10]. For example, a study conducted by Maron R. et al. showed that AI assistance can enhance dermatologists’ accuracy in distinguishing melanoma from nevus in image-based assessments, underscoring the potential of AI-based tools in assisting clinicians, as well as raising questions on how effective these tools are in practical scenarios, where patient age and medical history come into play [9].

In cosmetic dermatology, AI applications currently focus on skin analysis tools, as well as three-dimensional reconstructions of the face, to predict clinical outcomes of interventions, thus assisting in treatment planning [11,12]. Robot-assisted laser treatments continue to be a promising area of research, but so far, lack of safety data has prevented their practical implementation [11,12]. Lasers represent an integral part of dermatological practice, calling for specialized knowledge of the possible indications, as well as the choice of the correct laser device and settings. In the future, AI could assist less experienced physicians in clinical decision-making. To our knowledge, there is currently no comparative study on therapeutic decision-making, particularly regarding diagnosis and laser selection, of publicly available AI models versus clinicians. In this context, we aimed to directly compare dermatologists with varying levels of expertise and publicly available AI models in terms of diagnostic accuracy and laser treatment choice. More precisely, this study addressed the following research questions: (1) How does diagnostic accuracy of publicly available multimodal AI models compare with dermatologists at different levels of expertise when assessing dermatological images? (2) How do laser treatment recommendations compare between dermatologists and AI models?

To answer these questions, we conducted a prospective questionnaire study in which dermatologists (residents, board-certified dermatologists, and laser specialists) assessed 25 dermatological cases using standardized prompts. The same cases and prompts were presented and subsequently compared with four publicly available multimodal AI models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

All participating dermatologists were comprehensively informed of the study and its aims and had the choice to remain anonymous. Participants were informed via email with detailed instructions, as well as an outline of the survey structure, to ensure consistency throughout the study. The dermatologists received the questionnaire between 27 February 2025 and the 5 March 2025, and all surveys were completed by 11 June 2025.

The dermatologists received an online questionnaire in which a series of 25 clinical images was accompanied by a set of three questions (Supplemental Materials). The first question asked participants to identify the recommended first-line treatment (laser or alternative, if no laser). The Section 2 requested a diagnosis and possible differential diagnoses for the lesion, while the third question asked participants to confirm their treatment recommendation based on their diagnosis to see if their answer had changed. AI was presented with the same set of images and corresponding questions.

For the purpose of our analysis, the original set of 18 possible answers regarding first-line treatment was reduced to 6 broader categories: no laser treatment recommended, vascular lasers, devices for vascular lesions and hair removal, Q-switched lasers, full ablative lasers, and fractional lasers.

2.2. Participant Selection

Participants comprised dermatology residents, board-certified dermatologists, and dermatology specialists with additional expertise in laser treatments. Dermatology specialists with additional expertise in laser treatments were defined as board-certified dermatologists who routinely practice laser medicine as part of their clinical activity (on a near-daily basis) and who are actively involved in clinical or translational research in the field of laser dermatology.

A total of 18 dermatologists were invited to participate via personal invitation sent by email by the principal investigator. The survey was conducted through a closed Google Forms platform, with the choice to remain anonymous.

2.3. Image Selection

The images for this study were collected from various open access sources, resulting in a total selection of 33 images. To ensure a representative final selection, some images belonging to the same diagnosis were grouped together from different sources, resulting in 25 cases (Supplemental Materials).

2.4. Data Preparation and AI Model Selection

To minimize bias and ensure a fair comparison between AI diagnostic outputs and expert assessments, we implemented a rigorous image preprocessing pipeline. A central concern was that publicly available dermatological datasets may overlap with the pretraining corpora of large AI models, introducing data leakage or recognition bias.

To address this, we designed a sequence of transformations that obscure dataset identity while preserving diagnostic features. Each image underwent edge cropping (0.75%) followed by uniform white padding (1.5%); random geometric modifications, including scaling (0.9–1.1) and small rotations (−3° to +3°); and controlled photometric adjustments. The latter simulated natural variability in acquisition conditions: brightness and contrast were increased by 1–4%, saturation by 0.5–1%, and gamma correction applied with values between 0.8 and 1.2, mimicking subtle lighting and color balance shifts. Finally, pixel-level variability was introduced through Gaussian blur (kernel size 3), low-variance Gaussian noise, and imperceptible adversarial-style perturbations. Elastic deformations were considered but excluded due to the risk of obscuring fine lesion structures.

The pipeline was implemented in Python (3.12.7) using OpenCV (4.11.0), NumPy (1.26.4), PIL (10.4.0), SciPy (1.13.1), and PyTorch (2.9.0). All outputs were independently reviewed by two dermatologists (AJ and SMSJ), who confirmed that clinical interpretability was maintained.

This approach produced a dataset intentionally distinct from public repositories, minimizing recognition bias and ensuring that evaluation of multimodal AI systems, including ChatGPT-4o, Claude Sonnet 4, Gemini 2.5 Flash, and Grok-3, was conducted under conditions that assess true generalizability. These general-purpose models support image input and text-based reasoning, making them suitable for tasks involving dermatological assessment and explanation. All are accessible through widely used consumer platforms and may realistically be consulted by healthcare professionals or laypersons. By testing each model on our preprocessed dataset, we aimed to assess their diagnostic performance under realistic, unbiased conditions.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For the descriptive analysis, categorical variables were reported as absolute numbers with percentages. Mode with variation ratio was used to describe the most frequent first-line treatment selected before stating a suspected diagnosis (T1) and the suspected primary diagnosis (T2). Suspected primary diagnosis (SD) alone or the combination of SD and differential diagnosis (SD+DD), which evaluated at least one of the two, was assessed as a binary outcome (correct vs. incorrect). Diagnostic accuracy was defined as percentage of correct responses relative to the total number of evaluators and cases and was reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Clinically established synonyms commonly used in dermatological practice (e.g., iron tattoo for cutaneous siderosis, angioma for cherry angioma) were regarded as correct answers.

Comparisons of accuracy and proportions of selected treatments among groups were conducted using Pearson’s Χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. If a statistically significant difference was found, post hoc subgroup comparisons were adjusted using the Holm–Bonferroni method.

Inter-rater reliability, measuring the level of agreement among evaluators on the same cases, was measured using Gwet’s AC1 statistic with 95% CI [13]. The interpretation of AC1 is comparable to Cohen’s kappa and can be categorized as follows: <0, poor; 0–0.20, slight; 0.21–0.40, fair; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, good; and 0.81–1, very good agreement. Agreement between groups was assessed based on the majority consensus response (mode) within each group per case.

All tests were considered statistically significant at p-value <0.05. Analyses were performed with R software version 4.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Overall, 18 dermatologists took part in the study. Six (33.3%) were residents, six were board-certified dermatologists, and six were experts in lasers, with 50.0% of participants having more than ten years of experience in dermatology (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of dermatologists included in the study.

3.2. Diagnostic Accuracy

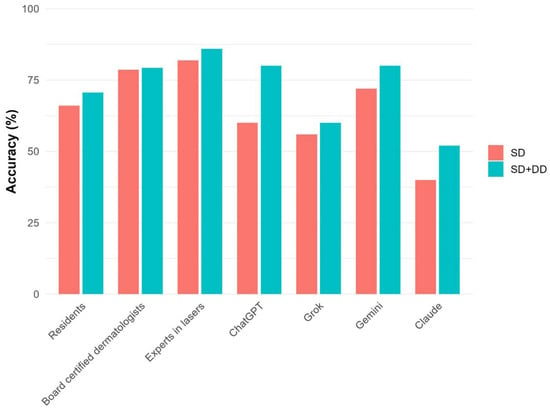

The overall diagnostic accuracy of dermatologists was 75.6% (95% CI: 71.4, 79.3) for SD and 78.7% (74.6, 82.2) for SD+DD (Table 2), with an increasing trend from residents (70.7% for SD+DD) to experts in lasers (86.0%) (Figure 1). Statistically significant differences were found between residents and experts for both SD and SD+DD (p = 0.002) and between residents and board-certified dermatologists for SD (p = 0.02) (Supplementary Table S1). In comparison, AI models’ accuracy was at 57.0% (47.2, 66.3) for SD and 68.0% (58.3, 76.3) for SD+DD. Differences between dermatologists and AI were all statistically significant (Supplementary Table S1). Gemini outperformed other AI systems with an SD of 72.0% (95% CI: 52.4–85.7%) and an SD+DD of 80.0% (95% CI: 60.9–91.1%), closely approaching the performance range of board-certified dermatologists. In contrast, Claude had the lowest diagnostic accuracy (SD: 40.0%, 95% CI: 23.4–59.3%). The detailed diagnostic accuracy for each case, in total and by the group of evaluators, is reported in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S1. For common or classic dermatological conditions such as acne vulgaris, rosacea, spider angioma, and infantile hemangiomas, AI models achieved up to 100% accuracy. In contrast, performance dropped markedly for rare disorders (such as blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome and angiosarcoma) and context-dependent presentations (such as hirsutism, cutaneous siderosis), with some cases showing 0% accuracy for both primary and differential diagnoses. Additionally, AI models often performed poorly on common dermatological diagnoses (such as venous lake of the lip, lentigo maligna, and lentigines solares).

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy for each group of evaluators, in total and in detail.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic accuracy for each group of evaluators in detail.

3.3. Treatment Recommendations

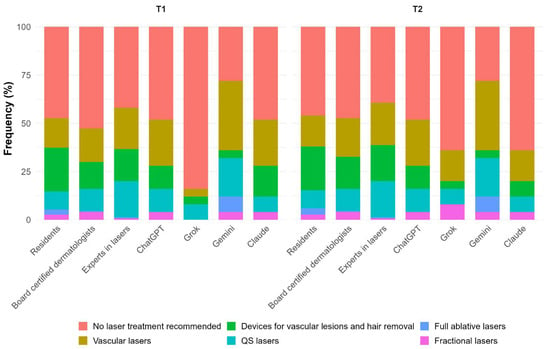

Table 3 describes the first-line treatment selected by each group of evaluators. Dermatologists recommended no laser treatment as first-line approach in 47.3% (T1) and 44.2% (T2) of cases. When considering T2, vascular lasers, as well as devices for vascular lesions and hair removal, were selected by 19.3% of participants and Q-switched lasers by 13.1%, while fractional and full ablative lasers were selected by 2.4% and 1.6%, respectively (Figure 2). Regarding AI, the distribution of T1 and T2 was very similar, with no laser treatment recommended for T2 in 51.0% of cases. Vascular lasers and Q-switched lasers were recommended in 23.0% and 12.0% of cases, respectively, devices for vascular lesions and hair removal in 7.0%, fractional lasers in 5.0%, and full ablative lasers in 2.0%. No significant differences were detected between dermatologists and AI with respect to laser recommendations (Supplementary Table S1). When analyzing different groups of dermatologists, some heterogeneity was detected, especially for T1 (p = 0.048), with experts suggesting vascular and Q-switched lasers more frequently, although no significant differences were found between groups in post hoc comparisons (Figure 2). A significant heterogeneity between AI algorithms was also detected for T1 (p = 0.02), especially between Grok and Gemini (p = 0.003), with Gemini favoring more interventional approaches.

Table 3.

First-line treatment selected by each group of evaluators, in total and in detail.

Figure 2.

First-line treatment selected by each group of evaluators in detail.

The detailed most frequent first-line treatments selected for each case, in total and by group of evaluators, is described in Supplementary Table S3.

3.4. Inter-Rater Agreement

The inter-rater reliability, as assessed by the AC1 statistic, in total and by group of evaluators, is shown in Table 4. Regarding diagnostic accuracy, AC1 among dermatologists was 0.51 (0.33, 0.69) and 0.56 (0.40, 0.73) for SD and SD+DD, respectively. The agreement within subgroups increased with growing clinical experience, ranging from 0.32 for residents (SD+DD) to 0.72 for experts.

Table 4.

Inter-rater reliability for diagnostic accuracy and for first-line treatment selected, in total and by group of evaluators.

AI algorithms showed a comparable level of moderate agreement for both SD (AC1 = 0.44; 95% CI: 0.21, 0.66) and SD+DD (0.60; 0.35, 0.85), though all estimates were characterized by wide confidence intervals. Agreement between dermatologists and AI, according to majority consensus, was generally moderate for SD (AC1 = 0.52). By subgroup, residents aligned most with AI on SD (0.77, 0.51–1.00), followed by board-certified dermatologists (0.52, 0.14–0.89) and laser experts (0.41, 0.00–0.83).

When considering the first-line treatment selected, a moderate agreement was found among dermatologists for T1 (0.47; 0.35, 0.59) and T2 (0.45; 0.33, 0.56), with an increasing trend between residents (0.41 for T2) to experts (0.56 for T2) and some heterogeneity between groups (Table 4). AI algorithms showed a similar level of agreement for T1 (0.46; 0.32, 0.61) and T2 (0.52; 0.37, 0.68). A moderate agreement was also detected between dermatologists and AI (AC1 = 0.40 for T1 and 0.45 for T2), with the highest agreement observed with residents (0.49 and 0.54 for T1 and T2 respectively), although comparable levels were also found with other groups of dermatologists.

4. Discussion

Lately, there have been exciting advances in the application of AI in dermatology, particularly in image classification tasks such as melanoma detection.5,6 While several studies have compared AI performance with that of dermatologists in controlled settings, fewer have evaluated how current general-purpose AI systems perform in complex real-world dermatological decision-making [7,8,9,10]. AI is increasingly being integrated into laser dermatology, primarily to enhance diagnostic accuracy, optimize treatment planning, and enable automated or semi-automated delivery of laser therapies [11,12]. Some devices already have embedded AI algorithms, which assist with energy selection, skin typing, and lesion targeting, aiming to improve treatment, safety, and reproducibility [11,12,14]. At the same time, traditional methods in aesthetic dermatology remain subjective and lack standardization [15]. This study aimed to assess and compare diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic decision-making between dermatologists at varying levels of experience and widely accessible multimodal AI models, using preprocessed clinical images and standardized questions.

Our study demonstrated that board-certified dermatologists, particularly those with laser specialization, significantly outperformed general-purpose AI models in diagnostic accuracy. Laser experts achieved the highest scores in both primary and differential diagnosis, followed by general dermatologists and residents. Among the AI systems, performance varied. While Gemini approached human-level accuracy, Claude performed substantially worse. As expected, AI experienced difficulty in correctly diagnosing context-dependent clinical images (e.g., cutaneous siderosis, hirsutism) and rare disorders (e.g., blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome). Yet surprisingly, AI also had low diagnostic accuracy for some common dermatological diagnosis such as venous lake of the lip and lentigo maligna, as well as lentigines solares. These findings highlight that current AI systems, when operating without patient history or clinical context, are still limited in their ability to reliably replicate expert-level dermatologic reasoning.

Generally, laser experts recommended interventional treatment more frequently, particularly vascular and Q-switched lasers, and demonstrated greater internal consistency. AI models were generally more conservative, except Gemini, which leaned toward strategies that are more interventional. Furthermore, some models shifted their treatment strategies after stating the suspected diagnosis: Claude becoming more cautious, Grok more aggressive. This highlights inconsistencies and susceptibility to external input in the decision-making process.

Overall, the agreement patterns indicate that current general-purpose AI come close to clinician diagnostic reasoning when differential diagnosis is considered (SD+DD) but diverge on treatment selection, particularly for case-specific first-line choices (T1, T2). Agreement on the suspected primary diagnosis (SD) was highest with residents and lower with experts, suggesting that AI is not as capable in weighing clinical context and paying attention to detail compared to laser experts. These findings are consistent with the previous literature demonstrating that AI models can reach or exceed dermatologist-level accuracy under narrow, controlled conditions [4,16]. However, practical implementation reveals limitations in generalizability, especially for underrepresented skin types, rare conditions, or ambiguous clinical contexts [17,18]. Our results reaffirm that expert human judgment remains essential in dermatologic practice, particularly where image interpretation must be integrated with clinical and contextual details.

This study has several limitations. First, participant recruitment was based on personal invitation by the principal investigator and therefore represents a convenience sample. As a result, the cohort may overrepresent academically active dermatologists. Additionally, one of the major limitations in applying AI in laser treatment selection is that for many indications, several methods may be correct, and no single standard of care exists (for example, vascular lesions with PDL/KTP/Nd:YAG/IPL or pigmentation with Q-switched or picosecond devices). Modality choice must therefore be individualized to lesion characteristics, anatomic site, Fitzpatrick phototype, patient preferences, and downtime tolerance. During questionnaire development, it was noted that AI systems were unable to specify treatment parameters such as wavelength, fluence, or pulse duration. Due to this limitation, exact laser setting parameters were excluded from the study. Although the AI models could suggest general treatment modalities, this lack of accuracy makes them unfit for independent therapeutic guidance in laser dermatology.

Additionally, when evaluating the results from our study, concerns about the ethical and regulatory implications of AI in clinical dermatology need to be considered. Use of AI with patient images raises serious questions about data security, unauthorized use, and potential privacy breaches [2,3,19,20,21]. In addition, the question of who is ethically and legally responsible for errors influenced by AI recommendations remains open [21]. This is especially relevant in the field of laser dermatology, where wrong decision-making can result in long-lasting complications such as post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, burns, and scarring.

Looking ahead, task-specific AI models developed and validated explicitly for dermatology, including laser-based diagnostics and therapy, may offer improved performance. With appropriate supervised training data, regulatory oversight, and clinical integration, such systems could support personalized treatment planning or assist in the real-time calibration and guidance of laser procedures. However, until such technologies are rigorously validated and their risks managed, general-purpose AI should be seen as an assistive tool, not a replacement for specialist knowledge.

5. Conclusions

In this comparative study, dermatologists, especially laser specialists, outperformed publicly available multimodal AI models in diagnostic accuracy for dermatological images. While treatment recommendations at the broad modality level appeared similar in distribution, AI models showed substantial variability and limited ability to incorporate clinical context, particularly in rare or context-dependent cases. These findings support that current general-purpose AI tools should not be used for unsupervised diagnostic or laser-treatment decision-making; task-specific training, clinical validation, and regulatory oversight are required before safe integration into routine practice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cosmetics13010005/s1, Study Questionnaire, Study Cases, Supplementary Table S1. Comparisons of diagnostic accuracy and first-line treatment selected by group of evaluators, Supplementary Table S2. Diagnostic accuracy for each case, in total and by group of evaluators, Supplementary Table S3. Most frequent first-line treatment selected for each case, in total and by group of evaluators, Supplementary Figure S1. Diagnostic accuracy for each case by group of evaluators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J. and S.M.S.J.; methodology, A.J., K.H. and S.M.S.J.; investigation, A.J. and S.M.S.J.; AI experiments, A.M.; data curation and statistical analysis, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.; writing—review and editing, A.J., A.M., S.C., A.B., F.B., S.B., L.F., C.F., H.-J.L., M.L., Z.M., S.M., D.O., A.R.-T., B.S., R.V.-B., C.V., N.Y., K.H. and S.M.S.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study used pre-existing images and did not involve human participants; consequently, the requirement for ethical committee approval was waived (cantonal ethics commission No.: KEK 2025-00943¨, 7 October 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

The study used pre-existing images and did not involve human participants; consequently, informed consent is not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for the study.

References

- Haug, C.J.; Drazen, J.M. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Clinical Medicine, 2023. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katwaroo, A.R.; Adesh, V.S.; Lowtan, A.; Umakanthan, S. The diagnostic, therapeutic, and ethical impact of artificial intelligence in modern medicine. Postgrad. Med. J. 2023, 100, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Bin Saleh, K.; Badreldin, H.A.; et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du-Harpur, X.; Watt, F.; Luscombe, N.; Lynch, M.D. What is AI? Applications of artificial intelligence to dermatology. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 183, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jairath, N.; Pahalyants, V.M.; Shah, R.B.; Weed, J.; Carucci, J.A.; Criscito, M.C. Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology: A Systematic Review of Its Applications in Melanoma and Keratinocyte Carcinoma Diagnosis. Dermatol. Surg. 2024, 50, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahm, W.J.; Sohail, N.; Burshtein, J.; Goldust, M.; Tsoukas, M. Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology: A Comprehensive Review of Approved Applications, Clinical Implementation, and Future Directions. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 1568–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escalé-Besa, A.; Yélamos, O.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Fuster-Casanovas, A.; Catalina, Q.M.; Börve, A.; Aguilar, R.A.-E.; Fustà-Novell, X.; Cubiró, X.; Rafat, M.E.; et al. Exploring the potential of artificial intelligence in improving skin lesion diagnosis in primary care. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, R.C.; Utikal, J.S.; Hekler, A.; Hauschild, A.; Sattler, E.; Sondermann, W.; Haferkamp, S.; Schilling, B.; Heppt, M.V.; Jansen, P.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Its Effect on Dermatologists’ Accuracy in Dermoscopic Melanoma Image Classification: Web-Based Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haenssle, H.A.; Fink, C.; Schneiderbauer, R.; Toberer, F.; Buhl, T.; Blum, A.; Kalloo, A.; Hassen, A.B.H.; Thomas, L.; Enk, A.; et al. Man against machine: Diagnostic performance of a deep learning convolutional neural network for dermoscopic melanoma recognition in comparison to 58 dermatologists. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1836–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, A.; Cappelli, M.O.; Ring, C.; Saedi, N. Artificial intelligence in cosmetic dermatology: An update on current trends. Clin. Dermatol. 2024, 42, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, A.; Ring, C.; Heitmiller, K.; Gabriel, Z.; Saedi, N. The role of artificial intelligence in cosmetic dermatology—Current, upcoming, and future trends. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwet, K.L. Handbook of inter-rater reliability: The Definitive Guide to Measuring the Extent of Agreement Among Raters; Advanced Analytics, LLC: Houston, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, D.T.; Ta, Q.B.; Ly, C.D.; Nguyen, C.H.; Park, S.; Choi, J.; O Se, H.; Oh, J. Smart Low Level Laser Therapy System for Automatic Facial Dermatological Disorder Diagnosis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thunga, S.; Khan, M.; Cho, S.I.; Na, J.I.; Yoo, J. AI in Aesthetic/Cosmetic Dermatology: Current and Future. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 24, e16640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomolin, A.; Netchiporouk, E.; Gniadecki, R.; Litvinov, I.V. Artificial Intelligence Applications in Dermatology: Where Do We Stand? Front. Med. 2020, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshjou, R.; Vodrahalli, K.; Novoa, R.A.; Jenkins, M.; Liang, W.; Rotemberg, V.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Bailey, E.E.; Gevaert, O.; et al. Disparities in dermatology AI performance on a diverse, curated clinical image set. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliorent, R.; Fardman, B.; Podwojniak, A.; Javaid, K.; Tan, I.J.; Ghani, H.; Truong, T.M.; Rao, B.; Heath, C. Artificial intelligence in dermatology: Advancements and challenges in skin of color. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrami, E.J.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Consulting ChatGPT: Ethical dilemmas in language model artificial intelligence. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 90, 879–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, E.R.; Trager, M.H.; Kontos, D.; Weng, C.; Geskin, L.J.; Dugdale, L.S.; Samie, F.H. Ethical considerations for artificial intelligence in dermatology: A scoping review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2024, 190, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowski, M.; Kropidłowska, J.; Kvinen, A.; Barańska-Rybak, W. A Systemic Review of Large Language Models and Their Implications in Dermatology. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2025, 66, e202–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.