Abstract

Hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers represent the most frequently performed minimally invasive procedures for facial rejuvenation, yet their overall safety profile is critically influenced by the cross-linking technology employed. Polyethylene glycol diglycidyl ether (PEGDE) has recently been introduced as an alternative to 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether (BDDE). The present prospective observational study was undertaken to evaluate the safety of a PEGDE-crosslinked HA filler for the correction of severe nasolabial folds. A total of 60 patients received bilateral injections of 1 mL per side and were monitored over a six-month period. Safety assessment included systematic documentation of adverse events and non-invasive biophysical and imaging techniques, specifically corneometry, sebumetry, and high-frequency ultrasound (HFUS). The treatment was well tolerated: 15% of patients reported only mild and transient adverse events, such as pain, swelling, bruising, or discomfort, while no serious adverse events, vascular compromise, or ocular complications were observed. Corneometry demonstrated a statistically significant increase in cutaneous hydration, sebumetry confirmed stability of sebaceous activity, and HFUS documented correct placement, homogeneous distribution, and progressive integration of the filler without nodules or granulomatous reactions. These findings support the favorable short-term safety and local tolerance of PEGDE-crosslinked HA fillers in the treatment of severe nasolabial folds.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, aesthetic medicine has progressively evolved as a minimally invasive alternative to surgical interventions, bolstered by advancements in the understanding of facial aging and by patients’ growing preference for procedures that offer reduced invasiveness, shorter recovery periods, and enhanced safety profiles. Among the available modalities, injectable dermal fillers containing hyaluronic acid (HA) constitute the most commonly performed procedures for facial rejuvenation. Their capacity to restore lost volume, redefine facial contours, and ameliorate wrinkles such as nasolabial folds (NLF) has established their integral role in routine dermatological and aesthetic practices [1,2,3].

International reports and clinical experience indicate that HA fillers rank among the most commonly performed minimally invasive procedures, with sustained year-on-year growth [1,2,3]. European data corroborate a similar trend, reflecting a worldwide shift toward minimally invasive approaches with favorable safety-to-benefit ratios. This widespread dissemination highlights the necessity for ongoing reassessment of the safety profile of filler technologies in clinical practice, particularly as new formulations enter the market [4,5,6,7,8].

Although dermal fillers are generally well tolerated, adverse events (AEs) may occur. Early procedure-related reactions, including erythema, edema, ecchymosis, pruritus, and discomfort, are relatively common yet self-limiting [3,5,6]. More infrequent but clinically significant complications encompass delayed inflammatory nodules, dyschromia, or granulomatous reactions, which can affect patient satisfaction and necessitate medical intervention [6,7,8]. In rare instances, severe events such as vascular occlusion, skin necrosis, or ocular involvement with visual loss have been documented, representing true emergencies that require immediate recognition and management [9,10,11,12,13]. Therefore, comprehensive anatomical knowledge, meticulous product selection, and thorough injector training are imperative to minimize risks. Additionally, hyaluronidase must always be readily accessible due to its unique ability to rapidly degrade HA hydrogels and restore perfusion in cases of intravascular injection [14].

The intrinsic properties of the filler material also play a pivotal role in determining its safety profile. Native HA exhibits a short in vivo half-life, being degraded within 24 to 48 h by endogenous hyaluronidases and eliminated through lymphatic and hepatic pathways [15,16]. To enhance persistence and mechanical resistance, HA is chemically stabilized via cross-linking agents. The most commonly utilized agent to date is 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether (BDDE), which has facilitated the development of highly effective and durable products. Nevertheless, residual BDDE and its by-products have raised concerns regarding long-term tolerance, antigenicity, and the potential for delayed inflammatory responses [17].

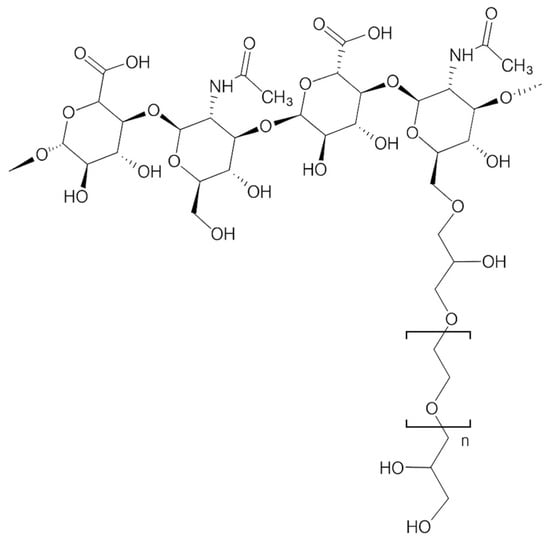

Polyethylene glycol diglycidyl ether (PEGDE) has recently gained recognition as an alternative cross-linking agent with several potential advantages over BDDE [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Structural representation of a hyaluronic acid polymer crosslinked through PEGDE.

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is widely used in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications due to its high biocompatibility, hydrophilicity, and low toxicity profile [18]. When incorporated into HA hydrogels, PEG-based crosslinking creates flexible and highly hydrated bridges between polymer chains, resulting in networks characterized by increased water uptake, enhanced viscoelasticity, and slower enzymatic degradation compared with non-crosslinked HA [15,19,20,21,22].

Compared with BDDE, PEGDE generates longer and more hydrophilic crosslinking bridges, which contribute to improved aqueous solubility and gradual biodegradation through hydrolysis and enzymatic cleavage of the HA backbone, while PEG fragments are eliminated via renal excretion [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. In vitro and ex vivo evidence suggests that PEG-based crosslinking may reduce residual epoxide-related reactivity, limit protein adsorption, and attenuate immune recognition, potentially lowering the likelihood of delayed inflammatory responses relative to BDDE-based systems [20,21,22,23].

Despite these theoretical and preclinical advantages, prospective clinical data specifically addressing the in vivo safety, tissue integration, and local biocompatibility of PEGDE-crosslinked fillers remain limited. This gap underscores the need for real-world evaluations to better characterize their behavior in aesthetic dermatology.

The PEGDE-crosslinked HA filler evaluated in this work was specifically formulated with stabilized sodium hyaluronate (28 mg/mL), supplemented with glycine and L-proline to enhance collagen synthesis, dermal remodeling, and tissue integration [21,22,23]. The product is distinguished by favorable viscoelastic properties, slow biodegradation, and reliable placement within deep anatomical planes, characteristics that are anticipated to ensure both efficacy and safety in clinical application. These advantages have prompted interest in PEGDE as a next-generation cross-linking agent, forming more hydrophilic and flexible bonds than BDDE and thereby promoting smoother tissue integration and reduced immunogenic recognition. However, despite these theoretical benefits, real-world, prospective data specifically addressing the in vivo safety and tissue integration of PEGDE-based HA fillers remain limited [24,25,26].

To date, most research concerning HA fillers has predominantly concentrated on efficacy outcomes, including wrinkle reduction, the longevity of volumetric correction, and patient satisfaction [1,2,3,27]. Fewer studies have systematically evaluated safety parameters, particularly through objective, instrumental methods. Nevertheless, documenting local tissue tolerance is vital to comprehensively understand the risk profile associated with dermal fillers. Accordingly, non-invasive biophysical techniques such as corneometry and sebumetry serve as valuable tools. Corneometry offers an indirect assessment of stratum corneum hydration, which indicates the integrity of the epidermal barrier and the absence of dehydration or inflammation [28,29,30,31]. Sebumetry measures sebum levels, providing insights into sebaceous gland activity and potential local irritative responses [29,30]. The application of these technologies in filler research may yield surrogate markers of safety that extend beyond mere clinical observation [31,32].

High-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) has also become an essential modality for assessing filler distribution, the depth of placement, and tissue interactions. HFUS is increasingly employed in dermatology to monitor dermal and subcutaneous structures, detect nodules or granulomas, and evaluate the persistence and homogeneity of filler implants [33,34,35]. Moreover, ultrasound facilitates differentiation between genuine complications and benign post-treatment findings, thereby enhancing clinical decision-making and patient reassurance [35,36]. The combination of corneometry, sebumetry, and HFUS provides complementary, reproducible endpoints that extend the evaluation of safety beyond clinical observation [37,38,39].

Within this framework, the present prospective observational study was designed to specifically characterize the in vivo safety profile and tissue integration of a PEGDE-crosslinked HA filler for the correction of severe NLF. By combining clinical documentation of adverse events with non-invasive biophysical measurements and high-frequency ultrasound imaging, this study aims to provide objective, real-world data on local tolerance and tissue behavior of PEGDE-based HA in aesthetic practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective post-market observational study was conducted at the Centro Medico Polispecialistico, Pavia (Italy). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Local Ethics Committee (CET 6 Lombardia, protocol number P-20200010552) in accordance with the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, as well as the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All procedures adhered to applicable ethical standards, and written informed consent was obtained from every participant before enrollment. The study design followed a real-world framework, reflecting standard clinical practice without any experimental intervention or modification to routine filler procedures.

2.2. Study Population

A total of 70 patients were initially screened; 10 (14.3%) were excluded due to non-compliance with the study protocol, resulting in 60 subjects for the final analysis. The cohort consisted of 58 females (96.6%) and 2 males (3.4%), with a mean age of 56.3 years (median: 58; range: 36–70 years). The sample size was determined based on feasibility and comparability with previous real-world studies on HA fillers, deemed sufficient to capture early and mid-term adverse events.

Inclusion criteria required subjects to be male or female, aged between 18 and 70 years at the time of enrollment, presenting with congenital or acquired NLF with a score ≥1.5 on the Modified Fitzpatrick Wrinkle Scale. Additional requirements included the ability to understand the study and comply with protocol demands, willingness to provide a complete medical history, and the capacity to sign informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, breastfeeding, or intention to conceive during the study period; prior filler or surgical correction in the NLF area within 3 months; previous permanent implants in the treatment site; active cutaneous inflammation, infection, or unhealed wounds in the target area; autoimmune/connective tissue disorders; prior radiation or ultrasound therapy in the treatment site; known hypersensitivity to HA, PEG, or product excipients; history of severe allergies or anaphylaxis; untreated epilepsy; tendency to develop hypertrophic scars; recent (<2 weeks) use of aspirin, NSAIDs, anticoagulants, or photosensitizing drugs; and systemic immunosuppressive or corticosteroid therapy. Patients were withdrawn in cases of loss to follow-up, voluntary withdrawal, protocol deviations, or if deemed necessary for safety by the investigator.

2.3. Treatment Protocol

All patients received a single injection session of a PEGDE-crosslinked HA filler (Neauvia Intense, 28 mg/mL stabilized sodium hyaluronate enriched with glycine and L-proline; Matex Lab, Brindisi, Italy). The product was administered bilaterally in the NLF with a mean volume of 1 mL per side. Injections were performed under aseptic conditions using either a 27G needle or a 25G/22G blunt-tip cannula, according to anatomical requirements. Cannula injections were performed through a lateral entry point along the anatomical trajectory of the fold, with retrograde linear threading in the deep subcutaneous or, when indicated, supraperiosteal plane. The deep plane was selected to minimize the risk of intravascular compromise and to ensure stable and homogeneous product placement. Needle injections followed the same anatomical alignment, employing linear threading or small boluses in the deep subcutaneous plane.

2.4. Safety Monitoring and Assessments

Safety was evaluated through both clinical observation and non-invasive instrumental assessments. Clinical follow-up consisted of immediate observation after injection and scheduled visits at 24 h, 48 h, 7 days, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months. AEs were defined as any undesirable local or systemic effect temporally related to the procedure, whereas SAEs included life-threatening reactions, hospitalization, permanent impairment, or vascular/ocular complications. Telephone interviews at 24 h and 48 h were used to collect patient-reported outcomes regarding erythema, edema, pain, ecchymosis, or unexpected symptoms. At each in-person visit, standardized photographic documentation was performed under identical lighting and camera settings, and any AE was recorded in a predefined case report form. Patients were instructed to report any intercurrent adverse event throughout follow-up, and spontaneous self-reports were reviewed by the investigators to confirm causality and resolution status.

2.5. Biophysical Measurements

Two standardized, non-invasive devices were employed to assess cutaneous physiology. Corneometry (Corneometer® CM825, Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH, Cologne, Germany) was used to quantify stratum corneum hydration [28]. Measurements were performed in a controlled environment (22–23 °C, 55–60% humidity) and expressed in arbitrary units (AU). Three consecutive readings were obtained per site, and the mean value was analyzed. Sebumetry (Sebumeter® SM815, Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH) was used to measure sebaceous secretion, based on photometry of a tape sampling system, with results expressed in Sebumeter units (0–350, approximated to µg/cm2) [29,30].

2.6. Ultrasound Evaluation

High-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) examinations were performed using a linear-array probe (L16-4HE, Mindray Medical International Ltd., Shenzhen, China) with a central frequency of 16 MHz and a scan depth of 20 mm, suitable for visualization of the dermis and superficial subcutaneous tissue. Examinations were conducted at baseline, immediately post-injection, and at 1, 3, and 6 months of follow-up. HFUS was used to confirm filler placement, tissue integration, and the absence of nodules, granulomas, or vascular compromise [33,34,35].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi software (version 2.2.5, Sydney, Australia) and R (version 4.0, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) [40,41]. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or 95% confidence interval (CI), and categorical variables as absolute frequencies and percentages. Normality of data distribution was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For normally distributed variables, paired Student’s t-tests were applied to compare pre- and post-treatment measurements of corneometry and sebumetry. Non-parametric data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, when applicable. Paired Student’s t-tests were used to compare pre- and post-treatment differences in corneometry and sebumetry values. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Adverse Events

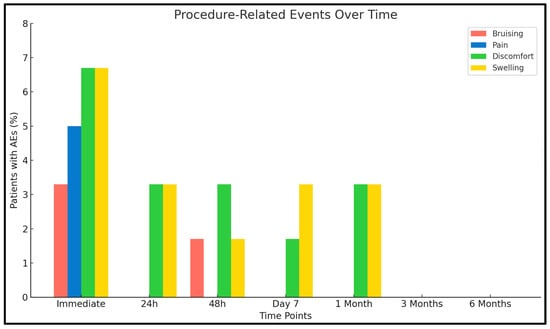

Treatment was consistently well tolerated across the study population [Figure 2]. Nine patients (n = 9/60; 15.0%) experienced mild and transient AEs immediately following injection. The most common AEs included localized pain (n = 3/60; 5.0%), swelling (n = 4/60; 6.7%), bruising (n = 2/60; 3.3%), and discomfort (n = 4/60; 6.7%). At 24 h post-treatment, seven patients (11.7%) continued to report mild AEs, primarily swelling (3.3%) and discomfort (3.3%). At 48 h, residual symptoms persisted in five patients (8.3%), including swelling (1.7%), bruising (1.7%), and discomfort (3.3%). By day 7, AEs were observed in three patients (5.0%), limited to minimal swelling or discomfort. At one month, 5 patients (8.3%) reported transient late-onset sensations of tightness or discomfort, all resolving spontaneously and without clinical relevance. No adverse events were detected at the 3- or 6-month evaluations. Importantly, no SAEs were reported during the entire follow-up, and no cases of vascular occlusion, necrosis, nodules, hypersensitivity reactions, or ocular complications occurred. The temporal resolution pattern and low cumulative incidence of AEs confirm the excellent tolerability and biocompatibility of the PEGDE-crosslinked HA filler [42,43,44].

Figure 2.

Distribution of procedure-related AEs over time. Bars represent the percentage of patients (n = 60) reporting specific AEs at each time point.

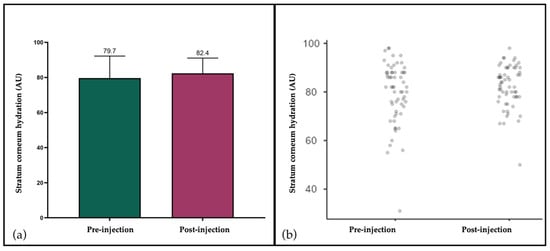

3.2. Corneometry

Baseline values demonstrated a mean of 78.8 AU (SD: 12.0), which rose to 82.3 AU (SD: 9.3) after injection [Figure 3]. The difference was statistically significant (paired t-test: t = –5.71; df = 59; p < 0.001). These findings imply that the PEG cross-linked HA filler did not impair epidermal hydration or barrier function, and the observed enhancement indicates that implantation maintained or marginally improved cutaneous hydration [28,29,45].

Figure 3.

Stratum corneum hydration assessed by corneometry before and after filler injection. (a) Mean values (±SD) showing a significant increase from baseline (79.7 AU) to post-injection (82.4 AU); (b) Individual patient values (n = 60) demonstrating consistent distribution and the absence of relevant outliers.

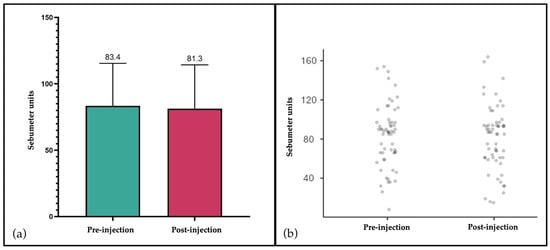

3.3. Sebumetry

Sebum levels exhibited minimal fluctuations between baseline and post-treatment assessments [Figure 4]. The mean baseline value was recorded at 82.3 µg/cm2 (SD: 33.7), compared to 82.4 µg/cm2 (SD: 31.3) subsequent to injection. This discrepancy was not statistically significant (paired t-test: t = –0.151; df = 59; p = 0.881). The stability of sebum production further corroborates the local biocompatibility of the filler, showing no stimulatory effect on sebaceous activity or pilosebaceous inflammation [29,30].

Figure 4.

Sebum levels assessed by sebumetry before and after filler injection. (a) Mean values (±SD) expressed in Sebumeter units, showing stable sebum secretion between baseline (83.4) and post-injection (81.3); (b) Individual patient values (n = 60) confirming minimal variation and absence of treatment-related stimulation of sebaceous activity.

3.4. Ultrasound Evaluation

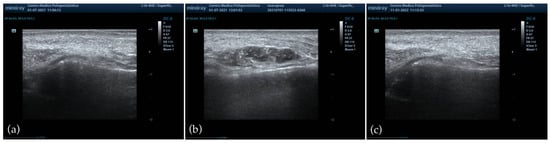

HFUS was performed in all patients at baseline, immediately after injection, and at 1, 3, and 6 months of follow-up. At baseline, imaging confirmed the absence of residual permanent or biodegradable fillers in the NLF area, thereby ensuring adherence to the exclusion criteria, and no abnormalities were detected in soft tissues or vascular structures. Immediately post-injection, ultrasound documented a homogeneous distribution of the filler in the deep anatomical plane, without evidence of vascular compromise or superficial misplacement. Subsequent evaluations at 1 and 3 months confirmed the persistence of correct filler positioning, showing progressive integration into the surrounding tissues and the absence of nodules, granulomas, or inflammatory infiltrates [Figure 5]. At the final six-month assessment, ultrasound confirmed the continued absence of late-onset inflammatory reactions or foreign body responses, and the filler appeared well integrated, with preserved homogeneity and no abnormal findings.

Figure 5.

HFUS evaluation of the NLF. (a) Baseline imaging showing absence of pre-existing filler material and normal soft tissue architecture; (b) immediate post-injection assessment demonstrating homogeneous distribution of the PEGDE-crosslinked HA filler in the deep anatomical plane, without vascular compromise or superficial misplacement; (c) six-month follow-up confirming progressive tissue integration, preserved homogeneity, and absence of nodules, granulomas, or late-onset inflammatory reactions.

4. Discussion

This prospective observational study confirmed the favorable safety profile and local tolerance of a PEGDE-crosslinked HA filler for the correction of severe NLF. Over six months, 60 patients were monitored, and treatment was well tolerated, with only mild and temporary AEs and no serious complications. The integration of instrumental methods provided objective evidence that the filler preserved skin homeostasis, maintained epidermal barrier function, and achieved homogeneous tissue incorporation without inflammatory reactions.

In our cohort, 15% of patients experienced mild immediate post-injection AEs such as swelling, pain, bruising, or discomfort. These were localized, self-limiting, and related to mechanical trauma from needle or cannula insertion. The occurrence of AEs decreased over the first week, and none were reported after three months. Importantly, no SAEs such as vascular occlusion, necrosis, or ocular complications were observed during follow-up. These results are consistent with previous evidence, which reported early local reactions in 10–25% of cases, typically resolving spontaneously within days [4,5,6,7,8]. The absence of SAEs is particularly relevant, since vascular and vision-related complications, although rare (<0.1%), remain the most feared risks of filler injections [9,10,11,12,13,42].

A distinctive feature of this study was the use of non-invasive biophysical techniques to assess local tolerance. Corneometry demonstrated a significant increase in hydration after filler injection, suggesting that barrier integrity was preserved and possibly enhanced rather than compromised. The increase in stratum corneum hydration observed after treatment is consistent with the intrinsic hydrophilicity of HA and the highly hydrated structure of PEGDE-crosslinked hydrogels. The polymer network exerts an osmotic water-binding effect that may transiently elevate superficial hydration without indicating irritation or inflammation. This interpretation is supported by the absence of erythema, barrier alteration, or inflammatory findings on HFUS. Sebumetry confirmed stable sebaceous secretion, thereby excluding inflammatory stimulation at the pilosebaceous level. Previous reports have highlighted the utility of these approaches in objectively quantifying cutaneous physiology beyond clinical observation [28,29,30,31,32,45]. These observations are compatible with the known hydrophilic behavior of HA-based hydrogels.

Similarly, HFUS confirmed correct anatomical placement, homogeneous filler distribution, and progressive tissue integration, with no evidence of nodules, granulomas, or late-onset inflammatory changes during the six-month follow-up. These results corroborate prior studies demonstrating the utility of ultrasound in monitoring filler positioning, identifying vascular compromise, and differentiating benign nodules from inflammatory complications [33,34,35,46]. The absence of abnormal findings in our study strengthens the evidence of safety and biointegration. These findings are consistent with recent evidence showing that HA-based injectable formulations enriched with amino acids demonstrate good local biocompatibility and predictable soft-tissue integration, as reported in mesotherapy and neck rejuvenation protocols [47,48]. Such studies underscore the relevance of combining clinical evaluation with instrumental and imaging techniques to objectively assess tissue response and treatment safety.

The favorable safety profile observed in this study can be attributed to the intrinsic characteristics of PEG cross-linking. While BDDE has historically been the gold standard cross-linking agent, residual molecules have raised concerns regarding immunogenicity and delayed inflammatory reactions [17]. Preclinical studies indicate that PEGDE may form hydrophilic and flexible cross-links that could reduce protein adsorption and attenuate immune recognition mechanisms [18,19,20,21,22,23,25]. In vitro and preclinical data have reported trends toward slower enzymatic degradation, lower inflammatory responses, and enhanced dermal integration of PEG cross-linked hydrogels [19,20,21,22,24,26]. The clinical and instrumental data from our study align with this experimental evidence, supporting the favorable safety profile of PEGDE-crosslinked HA, in line with preclinical observations [25,46].

Most clinical literature on HA fillers has focused on efficacy, patient satisfaction, or persistence, while systematic safety evaluations have been comparatively rare [1,2,3,27]. Observational studies on BDDE-based fillers reported early local reactions in 12–20% of cases, while delayed nodules were found in <1% [5,6,7,8]. Our findings are consistent with these reports, and future comparative studies may help clarify whether different crosslinking technologies influence local tolerance.

This study has several limitations. The six-month follow-up, although adequate for the assessment of early and mid-term safety, does not allow evaluation of late-onset reactions. Moreover, the single-center design, relatively small sample size, and strong female predominance (96.6% of participants) may limit the generalizability of the findings. The absence of a comparator arm, such as a BDDE-based filler, prevents any inference regarding differences between crosslinking technologies. Future multicenter studies with larger and more heterogeneous populations will be essential to validate and expand upon these observations.

Despite these limitations, the prospective design, real-life setting, and integration of clinical, biophysical, and ultrasound data represent significant strengths.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this prospective real-world study confirms the excellent safety, local tolerance, and tissue compatibility of PEGDE-crosslinked hyaluronic acid fillers for the correction of severe nasolabial folds. The integration of clinical, biophysical, and ultrasound findings showed that PEGDE-based fillers maintain epidermal hydration, sebaceous balance, and homogeneous tissue distribution over time, without inflammatory or vascular complications.

Further multicenter and long-term comparative studies are warranted to validate these observations and to better delineate the indications and long-term safety profile of PEGDE-based HA fillers in aesthetic dermatology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Z., A.C., G.C. and S.B.; methodology, A.C. and S.G.; software, Z.F.; validation, E.E., H.G. and R.R.; formal analysis, L.B., S.B. and M.R.; investigation, L.B., G.C. and S.S.; resources, R.M. and S.S.; data curation, S.G., C.A.M. and L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Z., G.C. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, A.C., Z.F., L.B., E.E., C.A.M., M.R. and H.G.; visualization, S.G., E.E., C.A.M. and Z.F.; supervision, N.Z., S.G., M.R. and E.E.; project administration, N.Z. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Pavia (protocol number P-20200010552), in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH), Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (approval date: 16 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the text was reviewed using an external English-language editing tool for the purpose of language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors S.S. and R.M. are employees of UB-CARE S.R.L., which is part of the MatexLab Group. Nicola Zerbinati is the Scientific Director of MatexLab. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AE(s) | Adverse Event(s) |

| SAE(s) | Serious Adverse Event(s) |

| HA | Hyaluronic Acid |

| NLF(s) | Nasolabial Fold(s) |

| BDDE | 1,4-Butanediol Diglycidyl Ether |

| PEGDE | Polyethylene Glycol Diglycidyl Ether |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| HFUS | High-Frequency Ultrasound |

| AU(s) | Arbitrary Unit(s) |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| ICH | International Conference on Harmonization |

| GCP | Good Clinical Practice |

References

- Fallacara, A.; Manfredini, S.; Durini, E.; Vertuani, S. Hyaluronic Acid Fillers in Soft Tissue Regeneration. Facial Plast. Surg. 2017, 33, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdan Allemann, I.; Baumann, L. Hyaluronic acid gel (Juvéderm) preparations in the treatment of facial wrinkles and folds. Clin. Interv. Aging 2008, 3, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funt, D.; Pavicic, T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: An overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 6, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagien, S.; Monheit, G.; Jones, D.; Bank, D.; Sadick, N.; Nogueira, A.; Mashburn, J.H. Hyaluronic Acid Gel With (HARRL) and Without Lidocaine (HAJU) for the Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Nasolabial Folds: A Randomized, Evaluator-Blinded, Phase III Study. Dermatol. Surg. 2018, 44, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, G.; Philipp-Dormston, W.G.; Van Den Elzen, H.; Van Der Walt, C.; Nathan, M.; Kolodziejczyk, J.; Kerson, G.; Dhillon, B. A Prospective, Open-Label, Observational, Postmarket Study Evaluating VYC-17.5L for the Correction of Moderate to Severe Nasolabial Folds Over 12 Months. Dermatol. Surg. 2017, 43, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monheit, G.; Beer, K.; Hardas, B.; Grimes, P.E.; Weichman, B.M.; Lin, V.; Murphy, D.K. Safety and Effectiveness of the Hyaluronic Acid Dermal Filler VYC-17.5L for Nasolabial Folds: Results of a Randomized, Controlled Study. Dermatol. Surg. 2018, 44, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp-Dormston, W.G.; Eccleston, D.; De Boulle, K.; Hilton, S.; van den Elzen, H.; Nathan, M. A prospective, observational study of the volumizing effect of open-label aesthetic use of Juvéderm® VOLUMA® with Lidocaine in mid-face area. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2014, 16, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, S.; Maas, C.S.; Grimes, P.E.; Beer, K.; Monheit, G.; Snow, S.; Murphy, D.K.; Lin, V. Safety and Effectiveness of VYC-17.5L for Long-Term Correction of Nasolabial Folds. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2020, 40, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.H.; Beynet, D.P.; Gharavi, N.M. Overview of Deep Dermal Fillers. Facial Plast. Surg. 2019, 35, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobanko, J.F.; Dai, J.; Gelfand, J.M.; Sarwer, D.B.; Percec, I. Prospective Cohort Study Investigating Changes in Body Image, Quality of Life, and Self-Esteem Following Minimally Invasive Cosmetic Procedures. Dermatol. Surg. 2018, 44, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyon, V.C.; Liu, C.; Fitzgerald, R.; Humphrey, S.; Jones, D.; Carruthers, J.D.A.; Beleznay, K. Update on Blindness from Filler: Review of Prognostic Factors, Management Approaches, and a Century of Published Cases. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2024, 44, 1091–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, A.E.; Ahluwalia, J.; Song, S.S.; Avram, M.M. Analysis of U.S. Food and Drug Administration Data on Soft-Tissue Filler Complications. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLorenzi, C. New High Dose Pulsed Hyaluronidase Protocol for Hyaluronic Acid Filler Vascular Adverse Events. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2017, 37, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroumpouzos, G.; Treacy, P. Hyaluronidase for Dermal Filler Complications: Review of Applications and Dosage Recommendations. JMIR Dermatol. 2024, 7, e50403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žádníková, P.; Šínová, R.; Pavlík, V.; Šimek, M.; Šafránková, B.; Hermannová, M.; Nešporová, K.; Velebný, V. The Degradation of Hyaluronan in the Skin. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chylińska, N.; Maciejczyk, M. Hyaluronic Acid and Skin: Its Role in Aging and Wound-Healing Processes. Gels 2025, 11, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruijtier-Pölloth, C. Safety assessment on polyethylene glycols (PEGs) and their derivatives as used in cosmetic products. Toxicology 2005, 214, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodo, G.; Trapani, A.; Torre, M.L.; Giammona, G.; Trapani, G.; Mandracchia, D. Hyaluronic acid and its derivatives in drug delivery and imaging: Recent advances and challenges. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 97, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.; Truong, N.F.; Segura, T. Design of cell-matrix interactions in hyaluronic acid hydrogel scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faivre, J.; Pigweh, A.I.; Iehl, J.; Maffert, P.; Goekjian, P.; Bourdon, F. Crosslinking hyaluronic acid soft-tissue fillers: Current status and perspectives from an industrial point of view. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2021, 18, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faivre, J.; Gallet, M.; Tremblais, E.; Trévidic, P.; Bourdon, F. Advanced Concepts in Rheology for the Evaluation of Hyaluronic Acid-Based Soft Tissue Fillers. Dermatol. Surg. 2021, 47, e159–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puljic, A.; Frank, K.; Cohen, J.; Otto, K.; Mayr, J.; Hugh-Bloch, A.; Kuroki-Hasenöhrl, D. A Scientific Framework for Comparing Hyaluronic Acid Filler Crosslinking Technologies. Gels 2025, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, F.; Cosentino, M.; Legnaro, M.; Luini, A.; Sigova, J.; Mocchi, R.; Lotti, T.; Zerbinati, N. Immune profile of hyaluronic acid hydrogel polyethylene glycol crosslinked: An in vitro evaluation in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, J.G.; Lin, P.; Schmidt, C.E. Biodegradable hydrogels composed of oxime crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol), hyaluronic acid and collagen: A tunable platform for soft tissue engineering. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2015, 26, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Jeong, C.H.; Han, J.H.; Lim, S.J.; Kwon, H.C.; Kim, Y.J.; Keum, D.H.; Lee, K.H.; Han, S.G. Comparative toxicity study of hyaluronic acid fillers crosslinked with 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether or poly (ethylene glycol) diglycidyl ether. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 296, 139620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbinati, N.; Lotti, T.; Monticelli, D.; Rauso, R.; González-Isaza, P.; D’Este, E.; Calligaro, A.; Sommatis, S.; Maccario, C.; Mocchi, R.; et al. In Vitro Evaluation of the Biosafety of Hyaluronic Acid PEG Cross-Linked with Micromolecules of Calcium Hydroxyapatite in Low Concentration. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Cockerham, K. Hyaluronic acid dermal fillers: Can adjunctive lidocaine improve patient satisfaction without decreasing efficacy or duration? Patient Prefer. Adherence 2011, 5, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rattanawiwatpong, P.; Wanitphakdeedecha, R.; Bumrungpert, A.; Maiprasert, M. Anti-aging and brightening effects of a topical treatment containing vitamin C, vitamin E, and raspberry leaf cell culture extract: A split-face, randomized controlled trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.K.; Cheng, N.Y.; Yang, C.C.; Yen, Y.Y.; Tseng, S.H. Investigating the clinical implication of corneometer and mexameter readings towards objective, efficient evaluation of psoriasis vulgaris severity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezerskaia, A.; Pereira, S.F.; Urbach, H.P.; Verhagen, R.; Varghese, B. Quantitative and simultaneous non-invasive measurement of skin hydration and sebum levels. Biomed. Opt. Express 2016, 7, 2311–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.A.; Kim, B.R.; Chun, M.Y.; Youn, S.W. Relation between pH in the Trunk and Face: Truncal pH Can Be Easily Predicted from Facial pH. Ann. Dermatol. 2016, 28, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léger, D.; Gauriau, C.; Etzi, C.; Ralambondrainy, S.; Heusèle, C.; Schnebert, S.; Dubois, A.; Gomez-Merino, D.; Dumas, M. “You look sleepy…” The impact of sleep restriction on skin parameters and facial appearance of 24 women. Sleep. Med. 2022, 89, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.; Jia, Q.N.; Jin, H.Z.; Li, F.; He, C.; Yang, J.; Zuo, Y.; Fu, L. Long-Term Follow-Up of Longevity and Diffusion Pattern of Hyaluronic Acid in Nasolabial Fold Correction through High-Frequency Ultrasound. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 144, 189e–196e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merola, F.; Scrima, M.; Melito, C.; Iorio, A.; Pisano, C.; Giori, A.M.; Ferravante, A. A novel animal model for residence time evaluation of injectable hyaluronic acid-based fillers using high-frequency ultrasound-based approach. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 11, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlosek, R.K.; Migda, B.; Skrzypek, E.; Słoboda, K.; Migda, M. The use of high-frequency ultrasonography for the diagnosis of palpable nodules after the administration of dermal fillers. J. Ultrason. 2021, 20, e248–e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, S.; Arginelli, F.; Farnetani, F.; Ciardo, S.; Bertoni, L.; Manfredini, M.; Zerbinati, N.; Longo, C.; Pellacani, G. Clinical Applications of In Vivo and Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbinati, N.; Rauso, R.; Protasoni, M.; D’Este, E.; Esposito, C.; Lotti, T.; Tirant, M.; Van Thuong, N.; Mocchi, R.; Zerbinati, U.; et al. Pegylated hyaluronic acid filler enriched with calcium hydroxyapatite treatment of human skin: Collagen renewal demonstrated through morphometric computerized analysis. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33, 1967–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Dong, L.; Guo, Z.; Liu, L.; Fan, Z.; Wei, C.; Mi, S.; Sun, W. Collagen-Hyaluronic Acid Composite Hydrogels with Applications for Chronic Diabetic Wound Repair. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 5376–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagaiah, P.; Valle, Y.; Sigova, J.; Zerbinati, N.; Vojvodic, P.; Parsad, D.; Schwartz, R.A.; Grabbe, S.; Goldust, M.; Lotti, T. Emerging drugs for the treatment of vitiligo. Expert. Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2020, 25, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi, Version 2.2; Computer Software; The Jamovi Project: Sydney, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 4.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Zerbinati, N.; Płatkowska, A.; Guida, S.; Stabile, G.; Mocchi, R.; Barlusconi, C.; Sommatis, S.; Garutti, L.; Rauso, R.; Cipolla, G.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Neauvia Intense in Correcting Moderate-to-Severe Nasolabial Folds: A Post-Market, Prospective, Open-Label, Single-Centre Study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundarò, S.P.; Salti, G.; Malgapo, D.M.H.; Innocenti, S. The Rheology and Physicochemical Characteristics of Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Their Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaldi, G.; Galasso, G.; Capillo, M.C.; Alonci, G.; Bighetti, S.; Bettolini, L.; Sommatis, S.; Mocchi, R.; Carugno, A.; Zerbinati, N. Rheology as a Tool to Investigate the Degradability of Hyaluronic Acid Dermal Fillers. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 18, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubik, P.; Bighetti, S.; Bettolini, L.; Gruszczyński, W.; Łukasik, B.; Guida, S.; Stabile, G.; Murillo Herrera, E.M.; Carugno, A.; D’Este, E.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of the Use of 1470 nm Laser Therapy in Patients Suffering from Acne Scarring of the Facial Skin. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 18, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubik, P.; Bighetti, S.; Bettolini, L.; Gruszczyński, W.; Łukasik, B.; Guida, S.; Stabile, G.; Paolino, G.; Murillo Herrera, E.M.; Carugno, A.; et al. The Effectiveness and Safety of 1470 nm Non-Ablative Laser Therapy for the Treatment of Striae Distensae: A Pilot Study. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J. Progress in Neck Rejuvenation Injection Therapy. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2025, 49, 5266–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Qorri, E.; Sbarbati, A.; Gehrke, S.A.; Marchetti, M.; Desiderio, V.; Amuso, D.; Tari, S. Mesotherapy with hyaluronic acid solutions enriched by amino acids in the neck area: Open-label uncontrolled, monocentric study. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2025, 27, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).