Abstract

Background: Photoaging results from cumulative ultraviolet-induced damage, mainly affecting sun-exposed areas such as the face, neck, and forearms. It manifests with textural roughness, irregular pigmentation, and wrinkles, reflecting structural degeneration across cutaneous layers. Objectives: This retrospective, uncontrolled, pilot study evaluated the efficacy of a biorejuvenating intradermal treatment combining free hyaluronic acid (HA) and glycerol in improving skin quality assessed by VISIA® CR. Secondary objectives included morphological and structural evaluation with PRIMOS 3D and LC-OCT, and exploratory clustering of post-treatment topography. Methods: Seventeen Caucasian women (45–67 years; mean 54, Fitzpatrick I–III) received HA-glycerol (CROMA Revitalis) via three-session picotage (n = 10) or two-session four-point injection (n = 7). VISIA® CR5 (spots, wrinkles, texture, pores, UV spots, porphyrins), PRIMOS 3D (roughness, volumetric parameters), and LC-OCT (stratum corneum and epidermal thickness, DEJ undulation) were analyzed. Results: VISIA® CR5 showed significant reductions in visible spots and porphyrins, with trends toward improvement in wrinkles and UV spots. PRIMOS 3D demonstrated qualitative improvement in most patients, and LC-OCT documented a significant increase in stratum corneum thickness with positive remodeling trends. Conclusions: This retrospective uncontrolled pilot study suggests that HA–glycerol intradermal biorejuvenation may improve multiple markers of photoaging, although conclusions are limited by sample size and short follow-up.

1. Introduction

Skin aging is a complex and multifactorial process influenced by both intrinsic factors—such as genetic predisposition and metabolic function—and extrinsic factors, the most significant being exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation [1,2,3]. When cutaneous aging is primarily driven by chronic sun exposure, the process is referred to as photoaging, a distinct clinical entity characterized by specific structural and functional changes in the skin [4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

The earliest and most evident signs of photoaging typically appear in chronically sun-exposed areas, including the face, lateral neck, and extensor forearms [11,12,13,14]. Clinically, photoaged skin may exhibit textural roughness, irregular pigmentation, telangiectasias, and fine to coarse wrinkles. These manifestations reflect underlying changes that can involve all cutaneous layers [4,15,16,17,18,19].

At the epidermal level, the most prominent features of photoaging are represented by epidermal hyperplasia and/or focal epidermal atrophy and/or dyskeratosis, often resulting in a complex tissue alteration, visible both on classical histopathology and through virtual biopsies obtained by means of non invasive imaging technologies, such as reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and laser confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT) [5,20]. The typical regular epidermal architecture observed in healthy epidermis may disappear, replaced by a disorganized architecture. Keratinocytes become polygonal with ill-defined borders, frequently exhibiting varying degrees of cellular atypia [5,20,21]. In parallel, the dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ) undergoes significant architectural degradation, characterized by a reduction in its natural undulating pattern and a progressive tendency toward flattening and linearization, which compromises mechanical stability and nutrient exchange between the epidermis and dermis [4,22,23].

Although photoaging overlaps with the natural process of chronoaging, it contributes disproportionately to the visible deterioration of skin quality, being increasingly recognized as a target for both preventive and corrective aesthetic treatments, driven by its impact on psychosocial well-being and patient demand for noninvasive skin rejuvenation strategies [2,24,25,26,27,28]. This has led to growing interest in intradermal hyaluronic acid (HA)-based formulations, which have demonstrated the ability to restore hydration, support extracellular matrix integrity, and promote cutaneous remodeling [29,30]. In the field of biorejuvenation, HA is frequently combined with glycerol, a highly hygroscopic molecule that enhances the hydrating properties of the formulation and helps prolong clinical benefits [31,32,33,34,35]. By attracting and retaining water within the extracellular matrix, glycerol improves skin turgor, elasticity, and barrier function, complementing the regenerative action of free HA [30,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. These agents are not intended for volumization but rather to improve cutaneous hydration, elasticity, smoothness, and radiance, leading to a refreshed and revitalized appearance. Unlike dermal fillers, skin quality enhancers are administered over broader surface areas to achieve uniform textural and tonal improvements without altering facial contours [30,36,38,39,40].

In this retrospective pilot study, we aimed to evaluate the clinical results and instrumental outcomes of a novel injectable formulation combining free hyaluronic acid and glycerol in individuals with moderate-to-severe facial photoaging.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Methodology

The study was designed as a retrospective analysis aimed at evaluating the effects of an intradermal biorejuvenation treatment with free hyaluronic acid combined with glycerol in the management of photoaged skin, using quantitative assessments obtained through VISIA® CR imaging and LC-OCT skin morphometry across two treatment protocols.

2.2. Study Population

Patients included in this retrospective analysis were adults aged over 40 years, with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes I to III, who had undergone the specified treatment for photoaging and presented with clinical signs such as fine wrinkles, uneven skin tone, pigmentary spots, and skin laxity. Included patients had completed the full treatment protocol, attended the scheduled follow-up visits, as documented in their medical records, and a complete set of imaging was available for analysis.

Patients were excluded if, according to available clinical documentation at the time of treatment, they had active dermatological conditions such as infections, dermatitis, or psoriasis, or were receiving systemic pharmacologic treatments potentially interfering with the outcomes, including topical or systemic retinoids, or had received aesthetic medical procedures in the last year.

2.3. Objectives

2.3.1. Primary Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of a biorejuvenating intradermal treatment with hyaluronic acid and glycerol in improving skin quality, as measured by quantitative VISIA® CR parameters.

2.3.2. Secondary Objectives

To assess fine morphological and surface topographic changes in the skin using PRIMOS 3D optical analysis (volumetric and roughness metrics, Color by Distance).

To evaluate microstructural changes in epidermal and dermo-epidermal morphology using LC-OCT imaging (stratum corneum thickness, viable epidermis thickness, and dermo-epidermal junction undulation).

To perform an exploratory morphological classification of post-treatment PRIMOS Color by Distance patterns, grouping patients into descriptive clusters to investigate potential predictors of treatment response.

2.4. Procedures

Clinical and instrumental data from participants treated with biorejuvenation protocols were retrospectively reviewed. Evaluations were conducted at two time points: baseline (T0) and follow-up (T2), two weeks after the completion of each participant’s assigned treatment regimen. Assessments included standardized VISIA® CR5 imaging, PRIMOS 3D optical skin analysis, and LC-OCT morphometry.

2.4.1. Injection Protocols

Biorejuvenation treatment consisted of intradermal injections of a formulation containing free (non-crosslinked) hyaluronic acid combined with glycerol (CROMA Revitalis, Croma-Pharma GmbH, Leobendorf, Austria). The product contained non-crosslinked hyaluronic acid (concentration: 15 mg/mL; average molecular weight ~ 1.2–1.5 MDa) combined with 20 mg/mL glycerol, according to manufacturer specifications. All procedures were performed under aseptic conditions with 30G needles, ensuring product delivery into the deep dermis (2.5–3 mm). Treatment focused primarily on the midface and lower face—areas most affected by photoaging. Participants underwent one of the following two treatment protocols, as documented in their clinical records:

- Protocol A (Standard): Three treatment sessions were carried out at two-week intervals. The traditional picotage technique was used, involving approximately 50 microinjections (0.02 mL per injection) evenly distributed across the treatment area. This approach is well established in clinical biorejuvenation and is associated with significant regenerative effects, although it may involve a slightly greater procedural complexity and recovery time compared to less intensive techniques [41].

- Protocol B (Customized): Two treatment sessions were conducted, also spaced two weeks apart. Each session consisted of four injection points in total (two per hemiface), with 0.25 mL of product administered per point. Injection sites were customized based on individual photoaging patterns to optimize diffusion and reduce procedural invasiveness. Following injection, a gentle manual massage was applied to promote homogeneous intradermal diffusion of the product.

2.4.2. Instrumental Assessment

Assessments included standardized facial imaging with the Visia® CR system and in vivo skin analysis using LC-OCT. These evaluations were performed both at baseline and at follow-up. Given the different structures of the two protocols, the total duration between baseline and follow-up was approximately 8 weeks for Protocol A and 6 weeks for Protocol B.

Previously described acquisition procedures have been followed both for Visia® CR5 (with PRIMOS module) and LC-OCT. These technologies enable simultaneous evaluation of superficial aesthetic changes and deep microstructural modifications, providing a comprehensive view of skin regeneration.

Visia® CR5 is a high-resolution multispectral imaging system employing standard and cross-polarized light, which reduces glare and enhances contrast. It generates a set of 2D parameters (Table 1), allowing standardized assessment of pigmentary, vascular, and morphological features [42,43].

Table 1.

2D parameters assessed with Visia® CR5.

PRIMOS, integrated within Visia® CR5, applies fringe projection technology to reconstruct 3D skin models. It provides quantitative volumetric data as well as color-coded surface maps for precise evaluation of depressions, elevations, and reliefs (Table 2).

Table 2.

3D parameters measured with PRIMOS.

LC-OCT, using a broadband infrared laser (safe and repeatable for patients) [44], offers simultaneous vertical and horizontal sections, 3D reconstructions with cellular level resolution, and penetration depth up to ~500 µm, with dermal collagen structures evaluable up to 250–300 µm. Key quantifiable parameters include stratum corneum and viable epidermis thickness, dermo-epidermal junction undulation, keratinocyte density and morphology, and cellular atypia [44,45,46]. With AI-based segmentation, it also enables 3D analysis of dermal fibers, melanin, and microvasculature [45,46]. Key quantifiable parameters are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Microstructural parameters evaluated with LC-OCT by automated image analysis.

All LC-OCT acquisitions were performed by the same experienced operator. Image analysis was carried out by two independent dermatologists who were blinded to treatment protocol and time point. For each patient, measurements were taken from three standardized anatomical fields (malar prominence, zygomatic area, and lateral periorbital region) to ensure reproducibility.

2.4.3. Standardized Home Skincare Routine

To minimize confounding variables, all patients were instructed to follow the same standardized home skincare routine during the entire treatment period. Facial cleansing was performed twice daily using a mild syndet cleanser (pH 5.5). Patients were advised to apply a non-comedogenic hydrating cream containing glycerin and ceramides once daily, and a broad-spectrum SPF 50+ sunscreen every morning. The use of exfoliating agents, retinoids, vitamin C serums, α/β hydroxy acids, and other active ingredients was prohibited for at least four weeks prior to baseline and throughout the study. No patient used additional topical or systemic treatments that could influence study outcomes.

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

Statistical analyses were performed to evaluate treatment effectiveness. Data normality was verified prior to analysis. Paired Student’s t-tests were used for within-group comparisons (baseline vs. post-treatment), while independent t-tests were applied for between-group comparisons (Protocol A vs. B). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In addition to p-values, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated for significant and near-significant results to estimate the magnitude of change, interpreted as small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8).

Exploratory Morphological Classification

In addition to quantitative outcomes, PRIMOS Color by Distance images were qualitatively reviewed by two independent dermatologists to identify recurring topographic patterns. Patients were assigned to three descriptive morphological subgroups (Clusters 1–3) according to post-treatment surface topography:

- Cluster 1: centrally distributed, relatively homogeneous depressions with preserved facial symmetry;

- Cluster 2: diffuse or peripheral irregularities with heterogeneous morphology;

- Cluster 3: multiple persistent irregular depressions.

This exploratory classification was not derived from a statistical clustering algorithm, but rather aimed at generating hypotheses regarding potential morphological predictors of treatment response. Inter-observer agreement was verified qualitatively, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. According to institutional policy, formal Ethics Committee approval was not required because this was a retrospective analysis of fully anonymized clinical data, with no possibility of patient identification. All patients had previously provided written informed consent for treatment and for the use of anonymized data for research and publication purposes.

3. Results

A total of 17 Caucasian female patients, aged between 45 and 67 years (mean age: 54 years), who had undergone one of the two treatment protocols were eligible for study inclusion (n = 10 for Protocol A; n = 7 for Protocol B). Fitzpatrick skin phototypes were documented, with 29% classified as phototype I (n = 5), 47% as phototype II (n = 8), and 24% as phototype III (n = 4). No serious adverse events were reported.

3.1. Visia® CR—Skin Quality Parameters

VISIA® CR5 skin quality measurements are summarized in Table 4. At baseline, image-based skin analysis using the VISIA® CR5 system documented mild to moderate signs of photodamage across the study population. Mean baseline scores were 0.39 for visible spots, 0.17 for wrinkles, 0.24 for skin evenness, 0.11 for pores, 0.40 for UV spots, and 0.16 for porphyrins.

Table 4.

Pre- and post-treatment VISIA® CR5 parameters by treatment protocol.

Baseline values were comparable between treatment subgroups. Protocol A (Standard, three sessions) showed slightly lower scores for most parameters compared to Protocol B (Simplified, two sessions), although the differences were not statistically significant.

At follow-up, VISIA® CR5 analysis demonstrated improvements across several parameters in both subgroups. Statistically significant changes were observed for visible spots in the three-session protocol (p = 0.008, Cohen’s d = 2.3, very large effect) and for porphyrins in both protocols (p = 0.044, Cohen’s d = 0.9, large effect). Additional borderline significant trends were recorded for wrinkles (p = 0.054, Cohen’s d = 0.7, medium-to-large effect—Figure 1) and UV spots (p = 0.052, Cohen’s d = 0.6, medium effect) in the three-session protocol. Other parameters did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05). Between-group comparison of post-treatment values showed no statistically significant differences for the remaining measures. Baseline comparability analysis showed no significant differences between Protocol A and Protocol B for any VISIA® CR5 parameter (all p > 0.05). The two groups were also similar in terms of age distribution and Fitzpatrick phototype. Full baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 1.

53-year-old woman—wrinkle improvement assessed by VISIA CR. (A) Baseline (T0); (B) Follow-up visit (T2). Wrinkle score decreased from 67% to 50%.

Table 5.

Baseline demographic and VISIA® CR5 imaging characteristics of patients by treatment protocol.

3.2. PRIMOS—Volumetric Analysis

Morphological skin changes were quantitatively assessed using the PRIMOS 3D optical skin analysis system (Table 5).

For the evaluation of wrinkle depth and surface irregularities, the parameters Rising Volume (mm3) and Mean Projection Rising (mm) were analyzed. Negative Δ values were considered indicative of improvement.

PRIMOS analysis showed post-treatment decreases in mean values across both parameters in the two protocols, although standard deviations were wide, suggesting a trend toward improvement. (Table 6) No statistically significant differences were detected between the groups. Effect sizes were small to medium (Cohen’s d range 0.3–0.5), consistent with modest but measurable volumetric changes.

Table 6.

PRIMOS volumetric changes (Δ pre–post) by protocol.

3.3. PRIMOS—Roughness Metrics

Surface roughness was evaluated through the indices SPp (maximum peak height), SPpm (mean peak height), SRa (average roughness), and SWp (maximum waviness).

PRIMOS analysis showed post-treatment decreases in mean values across all evaluated roughness parameters in both protocols, although standard deviations were wide (Table 7). None of the changes reached statistical significance (p > 0.05), and corresponding effect sizes were small (Cohen’s d < 0.3).

Table 7.

PRIMOS roughness metrics (pre–post comparison).

3.4. PRIMOS—Color by Distance

Skin surface topography was further evaluated using PRIMOS Color by Distance. This qualitative analysis provided an overview of topographic irregularities before and after treatment.

At follow-up, a perceivable improvement was observed in 16 of 17 patients (94.1%) across both protocols. Improvement was categorized as complete, partial, or absent (Table 8).

Table 8.

PRIMOS Color by Distance—qualitative outcomes by treatment protocol.

3.5. PRIMOS—Exploratory Morphological Classification

To further explore interindividual variability, patients were qualitatively classified into three morphological clusters based on post-treatment PRIMOS Color by Distance patterns. The distribution of patients and corresponding clinical outcomes across these clusters is summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Distribution of patients by morphological cluster and clinical improvement.

3.6. LC-OCT Parameters

Skin microarchitecture was evaluated using LC-OCT. The following parameters were analyzed: stratum corneum thickness (SC thickness), viable epidermis thickness, dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ) undulation, keratinocyte density, volume, compactness, and cellular atypia.

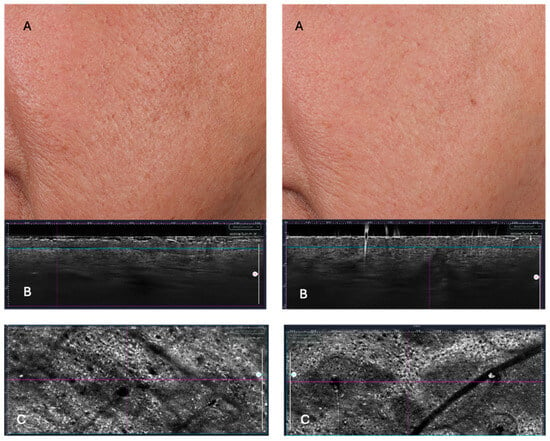

In the pooled population, SC thickness significantly increased (p = 0.032; Cohen’s d = 1.15, large effect), while epidermal thickness and DEJ undulation showed non-significant positive trends (p = 0.255 and p = 0.079, respectively; effect sizes medium-to-large, d = 0.6–0.8). Keratinocyte morphology and cellular atypia remained stable (Table 10, Figure 2).

Table 10.

LC-OCT microstructural parameters (pre–post comparison, total population, n = 17). Bold p-values indicate those closest to statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Surface Roughness (PRIMOS) and LC-OCT changes from T0 to T2. Pre- and post-treatment comparison (T0—left vs. T2—right). PRIMOS imaging captures (A) visible improvements in surface smoothness and reduction in scar depth, while LC-OCT (B,C) reveals underlying structural changes, including increased epidermal thickness and enhanced dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ) complexity. The greater DEJ undulation observed post-treatment is a hallmark of tissue rejuvenation, promoting better epidermal anchoring and nutrient diffusion.

Although no statistically significant differences were observed between the two protocols, post-treatment analysis showed overall positive trends in both groups, with protocol B showing a higher increment of epidermal thickness and DEJ undulation percentage.

4. Discussion

The data from our study supports the overall efficacy of intradermal biorejuvenation with free HA combined with glycerol in improving clinical and instrumental markers of photoaging. Multimodal assessment conducted with VISIA® CR, PRIMOS 3D, and LC-OCT confirmed across pigmentary, surface, and microstructural parameters, highlighting the regenerative impact of the treatment beyond superficial cosmetic effects. Comparable results were observed with both protocols, suggesting that efficacy is primarily related to the formulation itself rather than to procedural complexity. Unlike previous studies evaluating HA–glycerol formulations using biophysical parameters or clinical scoring, our study is, to our knowledge, the first to integrate multimodal imaging (VISIA® CR, PRIMOS 3D, and LC-OCT) to simultaneously assess pigmentary, topographic, and microstructural changes. The use of LC-OCT provides novel high-resolution in vivo evidence of epidermal and dermo-epidermal remodeling following HA–glycerol intradermal treatment, offering mechanistic insight beyond traditional clinical endpoints. VISIA® CR5 was designated as the primary outcome measure because it quantifies clinically observable and patient-relevant features—pigmentation, wrinkles, texture and pores—which represent the main aesthetic targets of biorejuvenation treatments. These parameters directly reflect real-world treatment effectiveness and are closely aligned with patient-perceived improvement. LC-OCT was therefore used as a secondary mechanistic endpoint to document microstructural correlates of these clinical changes, complementing but not replacing the primary clinical outcomes.

LC-OCT analysis confirmed significant increases in stratum corneum thickness (large effect size) and positive trends in epidermal thickness and DEJ undulation, indicating enhanced barrier function, hydration and dermo-epidermal remodeling. The stability of keratinocyte morphology and absence of atypia further support the safety of the intervention.

These morphometric changes support the concept that HA and glycerol exert regenerative effects that extend beyond superficial cosmetic effects to deeper layers, improving the functional architecture of the skin.

Our findings are consistent with existing literature highlighting the hydrating and regenerative effects of hyaluronic acid in counteracting photoaging, with glycerol acting as a complementary agent that enhances the biomechanical properties of the skin.

HA is well established not only as a filler but also as a biostimulator thanks to its capability to promote extracellular matrix homeostasis, enhance fibroblast motility, and upregulate collagen synthesis through CD44- and RHAMM-mediated signaling [29,30]. Beyond its hygroscopic capacity to bind up to 1000 times its own weight in water, HA acts as a viscoelastic regulator within the dermis, improving cell turgor, mechanotransduction, and tissue tension [32,36,37,38]. These effects contribute to fibroblast activation, increased dermal density, and restoration of ECM integrity, as demonstrated by in vivo studies reporting enhanced collagen turnover and improved viscoelastic parameters after HA microinjections [32,36,37,38]. Such findings support the dual hydrodynamic and regenerative role of HA, which underlies its long-term efficacy in counteracting photoaging and promoting structural skin remodeling.

Glycerol contributes to skin rejuvenation by improving surface texture and hydration and by reducing dermal stiffness, as demonstrated by the improvement in facial soft tissues documented in previous studies [47,48,49,50]. These biomechanical changes are believed to reflect a decrease in compressive stress within the epidermis and a restoration of cytoskeletal structure, potentially leading to improved cellular function [51,52]. Furthermore, computational models have shown that high concentrations of glycerol reduce stratum corneum drying stresses, leading to a redistribution of strain patterns in deeper skin layers and decreased perceived tightness, confirming its mechanobiological role [53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

These results align with the structural improvements observed in our study and suggest that glycerol plays a key role in modulating both superficial and deep tissue behavior, acting synergistically with HA to promote durable, regenerative outcomes in photoaged skin [47].

VISIA® CR analysis documented a significant reduction in some parameters. Wrinkle scores and UV showed a tendency toward improvement, with medium-to-large effect sizes, although the changes did not reach statistical significance. This may reflect underpowering due to the limited sample size. These results are consistent with the hydrating and smoothing properties of hyaluronic acid and glycerol reported in the previous literature [34,36,41].

PRIMOS 3D analysis demonstrated trends toward reduced wrinkle depth and surface irregularities, with qualitative 3D improvement observed in 94.1% of patients. Although surface roughness metrics trended downward, the changes did not reach statistical significance, likely due to small sample size and interindividual variability. The overall trend toward smoother skin, together with small-to-medium effect sizes, suggests measurable architectural remodeling.

Interestingly, the significant reduction documented by VISIA® CR analysis of visible spots and porphyrins, with large to very large effect sizes, not only confirms a relevant clinical impact on photodamaged skin, but also an influence on the microbial load. Recent evidences introduced the concept of “Porphyr’ageing”, ref. [62] identifying bacterial porphyrins as active contributors to the skin ageing process, as they can penetrate the stratum corneum and interact with viable epidermal cells, inducing IL-8 release, ROS generation, and melanin synthesis through TSPO/PBR-dependent pathways, while downregulating fibroblast genes involved in extracellular matrix maintenance, including COL1A1, SIRT1, and TERT. Clinically, their abundance correlates with wrinkle length and the number of invisible and brown spots, reinforcing their role as biomarkers of inflammageing and photoinduced damage. Therefore, the observed post-treatment decrease in porphyrin signal may not only reflect aesthetic improvement but could indicate a reduction in pro-oxidant bacterial metabolites and restoration of a healthier skin-microbiota equilibrium [62]. This hypothesis deserves further confirmation through metagenomic or metabolomic analyses designed to assess microbiota modulation following HA–glycerol biorejuvenation.

An exploratory morphological classification further identified three patient clusters based on post-treatment topography, with centrally distributed and symmetric depressions (Cluster 1) associated with the most consistent clinical improvements. This finding supports the hypothesis that baseline surface morphology may serve as a predictive marker of treatment response, warranting further validation in prospective studies.

Despite these encouraging results, the study has some limitations. The small sample size and the inclusion of only Caucasian women limit the generalizability of the findings. The retrospective design may also introduce bias and does not allow causal inference.

Moreover, some outcomes did not reach statistical significance, and the exploratory clustering should be regarded as hypothesis-generating, requiring validation in larger prospective studies. The two-week follow-up is insufficient to assess lasting dermal remodeling, as HA-based biorejuvenation typically requires 8–12 weeks for stabilization of extracellular matrix changes. Our findings should therefore be interpreted as early-phase responses rather than long-term outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective pilot study provides preliminary evidence that intradermal biorejuvenation with free hyaluronic acid combined with glycerol is safe and may improve clinical and microstructural markers of photoaging, as documented by multimodal imaging techniques. Improvements were observed in VISIA® CR parameters, PRIMOS 3D qualitative morphology, and LC-OCT microarchitecture, particularly in stratum corneum thickness and dermo-epidermal junction features. Although no major differences emerged between the two treatment protocols, results suggest that the biological effect is primarily driven by the formulation rather than procedural complexity. The study is limited by its small sample size, retrospective design, short follow-up period, and lack of mechanistic validation. Larger prospective controlled studies with longer follow-up are warranted to confirm the durability of results, clarify mechanisms, and further explore predictors of response, such as baseline topographic clusters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.F. and V.G.; methodology, T.F. and M.S.; formal analysis, T.F.; investigation, T.F. and M.S.; data curation, T.F. and A.D.G.; resources, P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.F.; writing—review and editing, V.G. and P.G.; visualization, T.F.; supervision, V.G. and P.G.; project administration, V.G.; funding acquisition, P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received financial support for medical writing and journal submission from Croma-Pharma® GmbH. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Croma-Pharma® GmbH for providing financial support exclusively for medical writing and journal submission, without any editorial influence.

Conflicts of Interest

This research received financial support for medical writing and journal submission from Croma-Pharma® GmbH. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

References

- Sachs, D.L.; Varani, J.; Chubb, H.; Fligiel, S.E.; Cui, Y.; Calderone, K.; Voorhees, J.J. Atrophic and hypertrophic photoaging: Clinical, histologic, and molecular features of 2 distinct phenotypes of photoaged skin. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khavkin, J.; Ellis, D.A. Aging skin: Histology, physiology, and pathology. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. 2011, 19, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, S.; Pellacani, G.; Ciardo, S.; Longo, C. Reflectance Confocal Microscopy of Aging Skin and Skin Cancer. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2021, 11, e2021068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Casari, A.; Beretti, F.; Cesinaro, A.M.; Pellacani, G. Skin aging: In vivo microscopic assessment of epidermal and dermal changes by means of confocal microscopy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013, 68, e73–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C. Well-Aging: Early Detection of Skin Aging Signs. Dermatol. Clin. 2016, 34, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langton, A.K.; Ayer, J.; Griffiths, T.W.; Rashdan, E.; Naidoo, K.; Caley, M.P.; Birch-Machin, M.A.; O’Toole, E.A.; Watson, R.E.B.; Griffiths, C.E.M. Distinctive clinical and histological characteristics of atrophic and hypertrophic facial photoageing. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandahl, K.; Olsen, J.; Friis, K.B.E.; Mortensen, O.S.; Ibler, K.S. Photoaging and actinic keratosis in Danish outdoor and indoor workers. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2019, 35, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berneburg, M.; Plettenberg, H.; Krutmann, J. Photoaging of human skin. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2000, 16, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu Haytoglu, N.S.; Gurel, M.S.; Erdemir, A.; Falay, T.; Dolgun, A.; Haytoglu, T.G. Assessment of skin photoaging with reflectance confocal microscopy. Ski. Res. Technol. 2014, 20, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosset, S.; Bonnet-Duquennoy, M.; Barre, P.; Chalon, A.; Kurfurst, R.; Bonte, F.; Nicolas, J.F. Photoageing shows histological features of chronic skin inflammation without clinical and molecular abnormalities. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 149, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, C.S.; Chang, H.; Salzmann, S.; Müller, C.S.; Ekanayake-Mudiyanselage, S.; Elsner, P.; Thiele, J.J. Photoaging is associated with protein oxidation in human skin in vivo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2002, 118, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contet-Audonneau, J.L.; Jeanmaire, C.; Pauly, G. A histological study of human wrinkle structures: Comparison between sun-exposed areas of the face, with or without wrinkles, and sun-protected areas. Br. J. Dermatol. 1999, 140, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Domyati, M.; Attia, S.; Saleh, F.; Brown, D.; Birk, D.E.; Gasparro, F.; Ahmad, H.; Uitto, J. Intrinsic aging vs. photoaging: A comparative histopathological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2002, 11, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, C.E.; Wang, T.S.; Hamilton, T.A.; Voorhees, J.J.; Ellis, C.N. A photonumeric scale for the assessment of cutaneous photodamage. Arch. Dermatol. 1992, 128, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Helfrich, Y.R.; Maier, L.E.; Cui, Y.; Fisher, G.J.; Chubb, H.; Fligiel, S.; Voorhees, J. Clinical, histologic, and molecular analysis of differences between erythematotelangiectatic rosacea and telangiectatic photoaging. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurat, J.H. Dermatoporosis: The functional side of skin aging. Dermatology 2007, 215, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierkötter, A.; Krutmann, J. Environmental influences on skin aging and ethnic-specific manifestations. Dermato-Endocrinology 2012, 4, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, N.M.; Watson, R.E.B.; Jones, C.J.P.; Shuttleworth, C.A.; Kielty, C.M.; Griffiths, C.E.M. Clinical features of photodamaged human skin are associated with a reduction in collagen VII. Br. J. Dermatol. 1997, 137, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, E.M.T.; Longo, C.; Curchin, C.; Soyer, H.P.; Prow, T.W.; Pellacani, G. In vivo assessment of chronological ageing and photoageing in forearm skin using reflectance confocal microscopy. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 167, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Casari, A.; De Pace, B.; Simonazzi, S.; Mazzaglia, G.; Pellacani, G. Proposal for an in vivo histopathologic scoring system for skin aging by means of confocal microscopy. Ski. Res. Technol. 2013, 19, e167–e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Zalaudek, I.; Argenziano, G.; Pellacani, G. New Directions in Dermatopathology: In Vivo Confocal Microscopy in Clinical Practice. Dermatol. Clin. 2012, 30, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, S.; De Pace, B.; Ciardo, S.; Farnetani, F.; Pellacani, G. Non-invasive Imaging for Skin Cancers—The European Experience. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 2019, 8, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goberdhan, L.T.; Pellacani, G.; Ardigo, M.; Schneider, K.; Makino, E.T.; Mehta, R.C. Assessing changes in facial skin quality using noninvasive in vivo clinical skin imaging techniques after use of a topical retinoid product in subjects with moderate-to-severe photodamage. Skin Res. Technol. 2022, 28, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, X.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Xue, P.; Liu, B.; Ju, Y.; Fan, X. Tailoring biomaterials for skin anti-aging. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 28, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csekes, E.; Račková, L. Skin Aging, Cellular Senescence and Natural Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Gao, X.; Xie, W. Research Progress in Skin Aging, Metabolism, and Related Products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelini, S.; Greco, M.E.; Vespasiani, G.; Trovato, F.; Chello, C.; Musolff, N.; Pellacani, G. Non-Invasive Imaging for the Evaluation of a New Oral Supplement in Skin Aging: A Case-Controlled Study. Ski. Res. Technol. 2025, 31, e70171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovato, F.; Ceccarelli, S.; Michelini, S.; Vespasiani, G.; Guida, S.; Galadari, H.I.; Pellacani, G. Advancements in Regenerative Medicine for Aesthetic Dermatology: A Comprehensive Review and Future Trends. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, V.; Federica, T.; Giuseppina, R.; Simone, M.; Giovanni, P. Hyaluronic Acid Fillers in Reconstructive Surgery. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e16693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Youn, C.; Lee, C.; Lee, K.C.; Shin, H.; Yeom, K.B.; Hong, W. Facial Skin Quality Improvement After Treatment with CPM-HA20G: Clinical Experience in Korea. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e16795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baspeyras, M.; Rouvrais, C.; Liégard, L.; Delalleau, A.; Letellier, S.; Bacle, I.; Schmitt, A.M. Clinical and biometrological efficacy of a hyaluronic acid-based mesotherapy product: A randomised controlled study. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2013, 305, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rho, N.K.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, W. Injectable “Skin Boosters” in Aging Skin Rejuvenation: A Current Overview. Arch. Plast Surg. 2024, 51, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fluhr, J.W.; Mao-Qiang, M.; Brown, B.E.; Wertz, P.W.; Crumrine, D.; Sundberg, J.P.; Elias, P.M. Glycerol regulates stratum corneum hydration in sebaceous gland deficient (asebia) mice. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 120, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagrafena, I.; Morin, M.; Paraskevopoulos, G.; Nilsson, E.J.; Hrdinová, I.; Kováčik, A.; Björklund, S.; Vávrová, K. Structure and function of skin barrier lipids: Effects of hydration and natural moisturizers in vitro. Biophys. J. 2024, 123, 3951–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine-Börger, L.; Hofmann, M.; Kerscher, M. Microinjections with hyaluronic acid in combination with glycerol: How do they influence biophysical viscoelastic skin properties? Ski. Res. Technol. 2022, 28, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succi, I.B.; da Silva, R.T.; Orofino-Costa, R. Rejuvenation of periorbital area: Treatment with an injectable nonanimal non-crosslinked glycerol added hyaluronic acid preparation. Dermatol. Surg. 2012, 38, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, J.; Carruthers, A. Hyaluronic acid gel in skin rejuvenation. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2006, 5, 959–964. [Google Scholar]

- Guida, S.; Galadari, H.; Vespasiani, G.; Pellacani, G. Skin biostimulation and hyaluronic acid: Current knowledge and new evidence. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monheit, G.D.; Coleman, K.M. Hyaluronic acid fillers. Dermatol. Ther. 2006, 19, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, B.; Khalili, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Amiri, R.; Aflatoonian, M. Employing hyaluronic acid-based mesotherapy for facial rejuvenation. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 6605–6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witmer, W.K.; Lebovitz, P.J. Clinical Photography in the Dermatology Practice. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2012, 31, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linming, F.; Wei, H.; Anqi, L.; Yuanyu, C.; Heng, X.; Sushmita, P.; Li, L. Comparison of two skin imaging analysis instruments: The VISIA® from Canfield vs the ANTERA 3D®CS from Miravex. Ski. Res. Technol. 2018, 24, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogien, J.; Tavernier, C.; Fischman, S.; Dubois, A. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT): Principles and practical use. Ital. J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 158, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvel-Picard, J.; Bérot, V.; Tognetti, L.; Orte Cano, C.; Fontaine, M.; Lenoir, C.; Suppa, M. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography as a tool for three-dimensional in vivo quantification of healthy epidermis: A pilot study. J. Biophotonics 2022, 15, e202100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnier, F.; Pedrazzani, M.; Fischman, S.; Viel, T.; Lavoix, A.; Pegoud, D.; Korichi, R. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography coupled with artificial intelligence algorithms to identify quantitative biomarkers of facial skin ageing. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoprete, R.; Hourblin, V.; Foucher, A.; Dufour, O.; Bernard, D.; Domanov, Y.; Potter, A. Reduction of wrinkles: From a computational hypothesis to a clinical, instrumental, and biological proof. Ski. Res. Technol. 2023, 29, e13267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.; Luebberding, S.; Oltmer, M.; Streker, M.; Kerscher, M. Age-related changes in skin mechanical properties: A quantitative evaluation of 120 female subjects. Ski. Res. Technol. 2011, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlaczyk, M.; Lelonkiewicz, M.; Wieczorowski, M. Age-dependent biomechanical properties of the skin. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2013, 30, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, H.S.; Joo, Y.H.; Kim, S.O.; Park, K.C.; Youn, S.W. Influence of age and regional differences on skin elasticity as measured by the Cutometer®. Ski. Res. Technol. 2008, 14, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caubet, C.; Jonca, N.; Brattsand, M.; Guerrin, M.; Bernard, D.; Schmidt, R.; Serre, G. Degradation of corneodesmosome proteins by two serine proteases of the kallikrein family, SCTE/KLK5/hK5 and SCCE/KLK7/hK7. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2004, 122, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, I.A.; Tabiowo, A.; Fryer, P.R. Evidence that major 78-44 kDa concanavalin A-binding glycopolypeptides in pig epidermis arise from the degradation of desmosomal glycoproteins during terminal differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 1987, 105, 3053–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, N.; Yay, A.; Bíró, T.; Tiede, S.; Humphries, M.; Paus, R.; Kloepper, J.E. β1 integrin signaling maintains human epithelial progenitor cell survival in situ and controls proliferation, apoptosis and migration of their progeny. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.P.; Bornslaeger, E.A.; Norvell, S.M.; Palka, H.L.; Green, K.J. Desmosomes: Intercellular adhesive junctions specialized for attachment of intermediate filaments. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1999, 185, 237–302. [Google Scholar]

- Niiyama, S.; Yoshino, T.; Yasuda, C.; Yu, X.; Izumi, R.; Ishiwatari, S.; Mukai, H. Galectin-7 in the stratum corneum: A biomarker of the skin barrier function. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2016, 38, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonca, N.; Guerrin, M.; Hadjiolova, K.; Caubet, C.; Gallinaro, H.; Simon, M.; Serre, G. Corneodesmosin, a component of epidermal corneocyte desmosomes, displays homophilic adhesive properties. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 5024–5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L.; Lo, C.H.; Huang, C.C.; Lu, M.P.; Hu, P.Y.; Chen, C.S.; Liu, F.T. Galectin-7 downregulation in lesional keratinocytes contributes to enhanced IL-17A signaling and skin pathology in psoriasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e130740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohman, H.; Vahlquist, A. In vivo studies concerning a pH gradient in human stratum corneum and upper epidermis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1994, 74, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nomura, J.; Hori, J.; Koyama, J.; Takahashi, M.; Horii, I. Detection and characterization of endogenous protease associated with desquamation of stratum corneum. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1993, 285, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, K.; Fujimoto, E.; Fujimoto, N.; Akiyama, M.; Satoh, T.; Maeda, H.; Tajima, S. In vitro amyloidogenic peptides of galectin-7: Possible mechanism of amyloidogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 29195–29207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.L.; Chiang, P.C.; Lo, C.H.; Lo, Y.H.; Hsu, D.K.; Chen, H.Y.; Liu, F.T. Galectin-7 regulates keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation through JNK-miR-203-p63 signaling. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meunier, M.; De Tollenaere, M.; Jarrin, C.; Chapuis, E.; Bracq, M.; Lapierre, L.; Zanchetta, C.; Tiguemounine, J.; Scandolera, A.; Reynaud, R. Bacterial porphyrins in healthy skin: Microbiota components impact melanogenesis and age-related processes leading to Porphyr’ageing. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2025; Early View. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).