Abstract

Contact dermatitis is a highly prevalent inflammatory disease of the skin with substantial impact on patients’ quality of life and occupational function. Although randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide the highest level of evidence for treatment evaluation, previous research has shown that the reporting quality of RCT abstracts is often suboptimal. This study aimed to assess the completeness of reporting of RCT abstracts on contact dermatitis according to the CONSORT extension for abstracts (CONSORT-A). A cross-sectional analysis of 304 abstracts indexed in PubMed between 1975 and 2024 was conducted. Each abstract was independently evaluated by two reviewers using the 17-item CONSORT-A checklist, with inter-rater agreement calculated by Cohen’s κ. The median adherence score was 5 out of 17 items (29.4%), with a range from 1 (5.9%) to 14 (82.4%). The reporting of study aims (82.9%), interventions (82.2%), and conclusions (91.1%) was frequent, whereas critical methodological elements such as participant criteria (4.6%), randomization (2.0%), trial registration (3.0%), and funding (0.7%) were rarely reported. Structured abstracts, hospital settings, significant study results, and more than seven authors were independent predictors of higher adherence in multivariate analysis. Abstracts published after 2008, when CONSORT-A was introduced, showed modest but significant improvement. These findings indicate that reporting quality of contact dermatitis RCT abstracts remains inadequate, underscoring the need for stricter journal requirements, structured abstract formats, and broader dissemination of CONSORT-A guidelines.

1. Introduction

Contact dermatitis, an inflammatory skin disorder, is characterized by the erythematous, pruritic lesions caused by exposure to some external agents. This type of dermatitis is one of the most common inflammatory skin diseases, and it significantly reduces quality of life, as it is often associated with different levels of occupational disability [1,2]. The most common form is irritant contact dermatitis (ICD), a result of the direct damage to the skin by irritants that compromises epidermal barrier function, which normally regulates permeability, maintains hydration, and exerts antimicrobial and antioxidant effects [3,4,5,6,7].

Years ago ICD was seen as a non-immunologic reaction, but recent evidence suggests that ICD involves an immune reaction [8,9,10,11]. In contrast, allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction mediated by the adaptive immune system [10,11,12]. The cornerstone for both ICD and ACD is elimination of the offending agent. Other non-pharmacological interventions, which could be recommended are avoidance of irritants (soaps, detergents, solvents, friction), use of protective gloves, and frequent application of emollients to restore barrier function. Identification of the allergen via patch testing and strict allergen avoidance is the key step in improvement of ACD [13,14]. Some patients, however, require pharmacological treatment, and topical corticosteroids are first-line for acute flares; systemic corticosteroids may be required in severe or widespread ACD [15,16,17]. Other therapies include antihistamines, which can help control pruritus (particularly in ACD), topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus), and monoclonal antibodies (dupilumab), which may be useful as steroid-sparing agents, especially in chronic ACD affecting sensitive areas but carry a significant risk of adverse effects [18,19,20].

To be up-to-date with recent improvements in patient care, clinicians often search for scientific articles, and the abstract of a scientific study frequently serves as the initial source of information regarding the outcomes of a clinical trial. Numerous readers, especially occupied clinicians, often depend exclusively on the abstract for swift updates on research outcomes [21,22]. In circumstances where access to the complete text is restricted (e.g., due to paywalls) or time is constrained, judgments regarding the application of a certain therapy may rely solely on the information provided in the abstract. Consequently, abstracts must provide adequate details regarding study aims, methodology, and outcomes to enable readers to evaluate the validity and application of the results in their particular patient case [21].

However, research has consistently shown that the reporting quality of clinical trial abstracts is often unsatisfactory and key information is frequently missing [23]. Poorly written or incomplete abstracts can mislead readers, hinder the inclusion of trials in systematic reviews, and reduce the impact of otherwise well-conducted studies on both the scientific community and clinical practice [24]. To address this problem of inadequate reporting, guidelines for writing randomized controlled trial (RCT) abstracts were developed. The CONSORT-A (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines were originally created for full-text trial reports in 2008, and later on the CONSORT-A extension for abstracts (CONSORT-A) was introduced [25]. This extension provides a checklist of 17 essential items to be included in RCT abstracts [21,25]. These recommendations emphasize, among other aspects, the clear identification of the study as a randomized trial in the title, a description of the trial design (including methods of randomization and blinding), and basic participant characteristics and setting (e.g., inclusion criteria and location of the study) [26,27].

Given the clinical and public health importance of contact dermatitis, it is crucial to determine whether the abstracts of RCTs in this area provide complete and accurate information. Ideally, these abstracts should allow dermatologists, allergologists, general practitioners, pharmacists, and other specialists to quickly evaluate the quality of the presented abstract and if the results of the study could help improve care of a particular patient.

Standardized reporting in abstracts is particularly important in fields like dermatology, where clinicians often screen a large number of new studies. A consistent and complete abstract facilitates comparison of research findings and supports evidence-based decision-making. Therefore, this study aims to assess the adherence of RCT abstracts on contact dermatitis to the CONSORT-A checklist and identify factors associated with better reporting.

2. Materials and Methods

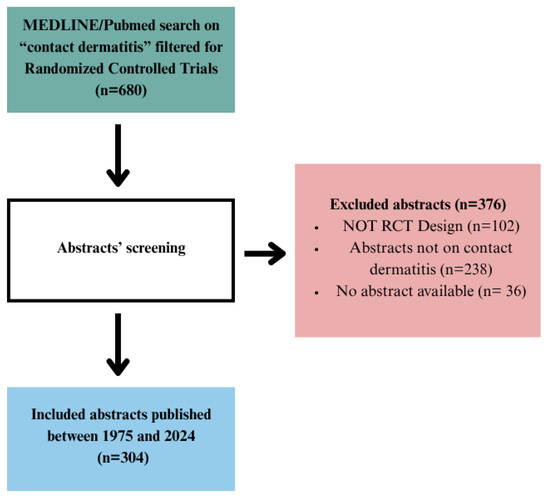

We have conducted a cross-sectional observational study on the abstracts of RCTs with the topic of contact dermatitis, indexed in MEDLINE/Pubmed (Figure 1). RCTs were included if they were designed with a control group, comparing intervention with either placebo, active treatment, or no treatment at all. Studies were excluded if they were conducted in animals or if the study design was anything other than RCT. Studies that did not have abstracts or did not include contact dermatitis as a topic were also excluded from our analysis. The selection process for the abstract inclusion in the study was performed by two authors presented with clear inclusion criteria. Any disagreement between two authors was resolved through discussion with the third author, the team member with the most experience in RCT conduction.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for contact dermatitis search strategy and study selection.

Although CONSORT-A guidelines were published in 2008, the study period was from 1975 to 2024 with the idea of comparing abstract quality before and after the guidelines were published. Additionally, analyzing a wider period, beyond the quality of reporting, could reveal interesting data on funding in this area or on how interventions for contact dermatitis have changed over the last five decades. The year 2025 was excluded because of the possibility of studies being published after this study has been finished. We have used on MEDLINE/PubMed the following search strategy: contact dermatitis AND (randomizedcontrolledtrial[Filter]). The list of the extracted abstracts is available upon a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Included RCT abstracts on contact dermatitis were independently assessed by two authors according to the CONSORT-A guidelines. One of the authors is a dermatology specialist with the experience of participating in RCTs, and the second author is an experienced research professional included in the conduction of clinical trials at the University Hospital Split. Any disagreement between the two authors was resolved through discussion with the third author, the team member with the most experience in RCT conduction and CONSORT-A research.

We have presented the data as an overall number and proportion and either median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean and the standard deviation (SD), where appropriate. The data was also presented as a mean value and 95% confidence interval (CI). To determine the appropriate descriptive statistics for continuous variables, the normality of distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. To determine interobserver agreement and reliability between the two independent reviewers, the Cohen κ coefficient was calculated. The interobserver agreement was considered sufficient for a kappa coefficient higher than 0.6. To compare abstract quality scores before and after CONSORT-A guidelines were published, the Mann–Whitney U test was used after data distribution was proven non-normal using Shapiro–Wilk test. Univariate regression with overall quality score as a dependent variable was used to determine the impact of each factor on the quality of reporting. Factors that were significantly associated with the higher quality of reporting in the univariate regression were included in the multivariate regression analysis to determine independent predictors and adjust for potential confounding variables. Adjusted R2 was calculated to determine how much variance could be explained with our multivariate regression model adjusted to all variables we included in the model. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 25). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 presents characteristics of included abstracts. Most of the included abstracts had non-pharmacological intervention (207/304, 68.1%) and reported on single-center studies (283/304, 93.1%). None of the included studies reported industry funding. A little over half of the studies reported significant results (162/304, 53.3%). Around three-quarters of studies were published in journals belonging to the first quartile (222/304, 74.3%), with the mean journal impact factor being 5.40 and the average number of study authors being 4.91.

Table 1.

Characteristics included contact dermatitis RCT abstracts.

The interobserver agreement was calculated using Cohen’s coefficient for all the items included in the CONSORT-A guidelines, and all values were above the recommended threshold of 0.60, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interobserver agreement for contact dermatitis RCT abstract items.

As seen in Table 3, only one study abstract out of 304 described the recruitment process properly (0.3%), two study abstracts had adequate information about funding (0.7%), and six study abstracts reported the randomization process correctly (2.0%). The conclusion part of the abstract was the best described one, with 277 study abstracts containing adequate information about that segment (91.1%).

Table 3.

Reporting frequency of CONSORT-A items in reviewed contact dermatitis abstracts.

Title and author information were properly provided by 60 and 66 study abstracts (19.7% and 21.7%). Trial design was adequately described by 59 studies (19.4%). Regarding the methods section, only 14 study abstracts included information about participants (4.6%), while most of the studies described objectives and information as guidelines proposed in the abstract (252 and 244, 82.9% and 82.2%).

Not a single item in the result section was properly described in the study abstract by more than half of the studies, while the number of patients randomized in each group had the highest score, with 147 abstracts describing it properly (48.4%), but only 13 study abstracts reported the number of patients analyzed in each group (4.3%). The harms of the study were described by only 41 abstracts (13.5%).

The median quality score was 5 (IQR 4–6) out of 17 (29.41%). The maximum score was 14 out of 17 (82.35%), while the minimum score was 1 out of 17 (5.88%). The overall reporting quality score is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Overall reporting quality score of RCT abstracts on contact dermatitis.

Table 5 shows that the highest mean score was in studies that reported hospital as the place of conduction, with a mean score of 54.62% (CI 32.03–77.21), while the studies, which had unstructured abstracts had the lowest mean score (26.45%, CI 24.90–28.00).

Table 5.

Overall reporting quality score for each contact dermatitis study characteristic.

Previously reported study characteristics were included in the univariate model, assessing the individual effect of each characteristic on the overall score. The exception was the reporting of industry funding because only two of the included abstracts reported that characteristic. The number of participants higher than 100 increased the overall score by 4.566% (p < 0.05); reporting of significant results increased the overall score by 4.578% (p < 0.001), while hospital setting increased the overall score by as much as 24.537% (p < 0.001). Structured abstracts (p < 0.001), the quartile in which the publication journal was included (p < 0.05), and the number of authors (p < 0.05) also significantly affected the overall reporting score (Table 6). Characteristics with statistically significant impact in univariate analysis were included as predictors in multivariate analysis. The type of intervention, number of study centers, and impact factor of the publication were excluded from the multivariate analysis.

Table 6.

Linear-regression-derived estimates on contact dermatitis abstract items.

Adjusted R2 for multivariate analysis was 0.246, which means that the multivariate analysis model used explains 24.6% of the variance of the overall score. The setting of the study (p < 0.001), structured abstract (p < 0.001), significance of the results of the study (p < 0.01), and publication having more than 7 (p < 0.05) authors remained significant predictors of overall score in the multivariate regression analysis.

Most of the studies had emollients as an intervention (57, 18.8%), followed by provocation tests and allergens (53, 17.4%). The use of corticosteroids was the most studied pharmacological intervention, with 29 studies (9.5%) investigating their effect on contact dermatitis. Education and prevention programs (26, 8.6%) and incontinence and wound healing products (23, 7.6%) complete the five most common groups of interventions. Studies investigating effects of new drug dosage forms (2, 0.7%) and diet interventions (3, 1.0%) were the least represented ones.

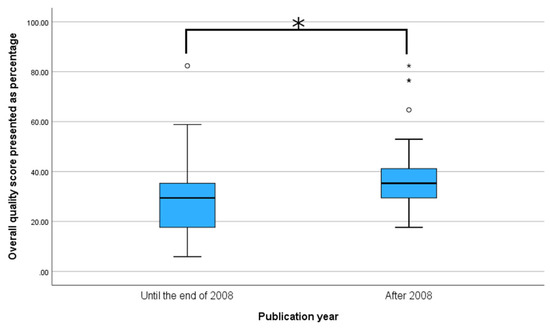

Since CONSORT-A guidelines were published in 2008, overall quality scores were compared for the period until 2009 and the period including 2009 and afterwards. Study abstracts after the publication of CONSORT-A guidelines had significantly higher overall scores (35.29 (11.76)%, median and IQR) compared to studies published before the guidelines (29.41 (17.65)%, median and IQR, p < 0.001), as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean overall reporting score for periods before and after publishing CONSORT-A guidelines. * p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test.

4. Discussion

Our study’s findings present a stark assessment of the quality of abstract reporting in RCTs concerning contact dermatitis. Although the CONSORT-A was established in 2008 in order to enhance transparency and rigor in clinical research communication, our analysis reveals that numerous essential elements of trial design and methodology remain consistently underreported. Of the 304 included abstracts, the median adherence score was just 5 out of 17 checklist items, equating to a modest 29.41%. This indicates that, on average, less than one in three recommended items are present in the abstract of a specific RCT, despite these components being considered crucial for the precise evaluation of trial validity and relevance. The adherence range was extensive, with the lowest-scoring abstract meeting only one checklist item, whereas the most thorough achieved 14 out of 17, nevertheless falling short of complete compliance. What is especially significant is not just the overall quality of reporting but also its distribution among various components of the abstract. Specifically, findings (91.1%), objectives (82.9%), and interventions (82.2%) were predominantly well-documented. These aspects provide the narrative “front end” of a clinical abstract, frequently emphasized by authors and easily discernible to readers. Their relatively high rates of inclusion are predictable given they are often considered as fundamental to the communication function of an abstract.

By comparison, other variables such as finance (0.7%), recruitment (0.3%), and randomization (2.0%) were strikingly underrepresented. These flaws are not only technical oversights; they reflect substantial gaps. Every excluded item entails repercussions. Without details on randomization processes, readers cannot reliably evaluate the possibility of selection bias. In the absence of funding disclosure, possible conflicts of interest remain concealed. The absence of recruitment details renders the study’s generalizability and timing ambiguous. The trends indicate that certain elements of the CONSORT-A checklist have been assimilated by the academic community, while others continue to be peripheral in the abstract-writing process. This reporting disparity likely stems from both institutional and cultural influences, including editing policies, word count constraints, and the ongoing emphasis on outcome-driven narratives rather than methodological clarity [21].

To situate these findings within the wider scientific dialog, we look at the work by McPhie et al., which analyzed 198 RCT abstracts published in prestigious dermatology publications from 2015 to 2019. Their study, despite its methodological differences in scope and selection, provides a valuable comparison in both thematic and empirical aspects. McPhie and associates reported an average adherence of 42%, far surpassing the 30.65% recorded in our study [28]. Multiple explanations may elucidate this discrepancy. Their sample was only derived from the top 10 dermatology publications, which may impose more rigorous editorial standards, including compliance with reporting rules. Secondly, their timeframe was confined to a five-year interval following the CONSORT-A release, possibly encompassing a phase of increased awareness and adherence. In contrast, our study covers a somewhat wider temporal range (1975–2024), including a considerable number of abstracts published before or shortly after the implementation of CONSORT-A. Despite these contextual disparities, both studies agree on a critical observation: the quality of reporting is inadequate, and certain CONSORT-A elements are consistently overlooked. Both datasets revealed extremely low reporting rates for methodological rigor metrics. For instance, randomization and funding were documented in about 2–3% and less than 1% of abstracts, respectively, in both studies. The agreement among independent studies enhances the reliability of our results and highlights the widespread nature of underreporting.

Both studies concur on the predominance of well-documented features, including aims, interventions, and findings; however, they disagree in their identification of the determinants of reporting quality. Our analysis identified structured abstracts, hospital-based settings, and multi-authorship (specifically with more than seven authors) as statistically significant predictors of increased adherence, even in multivariate analyses. In contrast, McPhie et al. identified journal impact factor, abstract word count, and the existence of a registered/published protocol as the most significant criteria. The structured abstract format, while significant in univariate analysis in their study, lost significance upon correction. This disparity is enlightening. It indicates that various editorial ecosystems and institutional cultures may influence reporting behavior in distinct manners. In prestigious journals, external influences like impact factor measurements, trial registration requirements, and compliance with open scientific principles may exert a greater influence. Conversely, our extensive sample indicates that institutional context (e.g., hospital environment) and collaborative authorship frameworks can substantially influence reporting behaviors, potentially via internal review processes, mentorship, and availability of research support infrastructure [28].

The inadequate reporting of participant data is particularly concerning, as dermatological disorders such as contact dermatitis may differ substantially across patient groups (e.g., occupational vs. allergic forms, pediatric vs. adult onset). Without explicit eligibility criteria, clinicians may misinterpret whether study findings apply to their own patients. Randomization and blinding are essential for minimizing bias, and omissions in these areas directly affect how clinicians judge the reliability of treatment effects. Missing methodological details or biased interpretation within an abstract can therefore influence treatment decisions and potentially lead to inappropriate therapy choices or overlooked safety risks in specific patient groups.

Within the CONSORT-A methodology, the results domain encompasses numerical reporting of randomized participants, evaluated outcomes with effect sizes and confidence intervals, as well as any documented adverse effects. In our sample, none of these items exceeded the 50% reporting level. Significantly, merely 13 presentations (4.3%) disclosed the number of patients studied, a figure alarmingly low considering its critical role in evaluating attrition and distinguishing between per-protocol and intention-to-treat analyses. The hazards section was reported in merely 13.5% of abstracts. This presents significant ethical dilemmas: when a study examines an intervention for a non-life-threatening illness like contact dermatitis, a favorable safety profile may be as crucial as efficacy in influencing clinical adoption. The underreporting of adverse events compromises methodological transparency and may result in clinical misjudgment and increased patient risk [22].

The most notable omissions are in trial registration (3.0%) and funding disclosure (0.7%). These items are essential for monitoring selective reporting, identifying conflicts of interest, and ensuring transparency in the study process. Their almost total absence in decades of publications indicates that cultural and editorial standards have persistently undervalued these disclosures in abstracts, despite their increasing prominence in full manuscripts. It is important to emphasize that these are not solely bureaucratic components. Trial registration is essential for research integrity, providing protection against data dredging and post hoc outcome tampering. The lack of this information in abstracts prevents the reader from confirming that the stated outcomes align with the original intentions [22].

In contrast to the previous categories, reporting was notably high for conclusions (91.1%) and study aims (82.9%). This is unsurprising. These aspects frequently serve as the rhetorical focal points of abstracts, where authors strive to engage the attention of editors, reviewers, and prospective readers. Their prevalence in reporting highlights a recurring trend in academic publishing: a focus on communicative efficacy rather than technical thoroughness. A well-crafted conclusion and a defined purpose are necessary but inadequate by themselves. In the absence of the methodological framework advocated by the CONSORT-A checklist, such narratives may be misinterpreted without essential critical context.

A notable characteristic of our study, compared to previous research, is its extensive temporal range. Covering almost five decades (1975–2024), our research facilitated an exploration of longitudinal trends in compliance with CONSORT-A recommendations, especially before and after their release in 2008. The analysis of reporting quality before and after 2008 revealed a promising, albeit modest, outcome: abstracts published subsequent to the implementation of CONSORT-A exhibited a statistically significant enhancement in overall quality ratings (median 35.29% vs. 29.41%, p < 0.001). Although this indicates a certain level of adoption, the extent of enhancement was constrained, and the median following 2008 still demonstrates inadequate compliance overall.

It indicates that the distribution of CONSORT-A was probably inconsistent among the dermatological research community, exhibiting more significant impacts in specific journal tiers or geographical areas. Higher-impact or internationally indexed journals may have implemented these requirements more stringently, whilst lower-tier or regionally oriented publications may have fallen short [28].The observed improvement, although statistically significant, may indicate a gradual cultural transition towards more transparency, influenced not solely by CONSORT-A but also by wider movements in research ethics, reproducibility, and open science. In this context, the modest improvements observed after 2008 may indicate the onset of more profound changes in progress, a promising yet steady evolution in the principles governing clinical research reporting.

The results of this study hold considerable significance for academic academics, journal editors, peer reviewers, and doctors who depend on the abstract as a summary of scientific knowledge. The persistent inadequate adherence to CONSORT-A rules across almost all reporting items, despite the elapse of over 15 years since their inception, indicates a fundamental disjunction between the presence of guidelines and actual compliance in practice. Clinical researchers, especially those engaged in RCT design and reporting, should prioritize abstract literacy, recognizing that the abstract has a purpose beyond merely acting as a promotional summary. For numerous readers, it serves as the principal or even exclusive access point to the trial. Consequently, the exclusion of methodological elements such as blinding, allocation, or adverse effects is not merely a matter of conciseness; it is a choice that may undermine the interpretability and integrity of the research itself.

By examining RCT abstracts across nearly five decades, we were able to identify inadequacies in the reporting quality of contact dermatitis RCT abstracts, including the modest improvement in reporting after the introduction of the CONSORT-A checklist. In addition, the use of both univariate and multivariate analyses allowed us to explore independent predictors of reporting quality while accounting for potential confounders. However, several limitations should also be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample was restricted to PubMed-indexed abstracts, which may limit the generalizability of findings, as journals not indexed in MEDLINE were not included and there is potential for missing relevant studies published in other databases or in the gray literature. Secondly, the assessment focused exclusively on abstracts and did not account for the quality of full-text reporting, which may in some cases be more comprehensive. Nonetheless, given clinicians’ increasing reliance on abstracts for rapid decision-making, the quality of abstract reporting remains important in all areas of clinical medicine. Therefore, we believe adding CONSORT-A guidelines to the instructions for authors in scientific journals could enhance reporting quality and indirectly, as a consequence, provide better data to clinicians.

5. Conclusions

This study presents the first comprehensive longitudinal analysis of how randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on contact dermatitis are reported in the biomedical literature, revealing substantial underreporting at the abstract level. Despite clear and widely available CONSORT-A guidelines, critical aspects of trial design, methodology, and transparency, such as randomization methods, adverse effects, trial registration, and funding, remain consistently omitted. These omissions undermine scientific integrity and represent missed opportunities to strengthen credibility and reproducibility. Although structured abstracts, hospital settings, and multi-authorship relate to better reporting, improvement since 2008 has been modest, underscoring that guideline dissemination alone is insufficient. Our findings emphasize that transparent reporting must become an integral, expected standard of scientific communication. Ultimately, ensuring completeness and methodological clarity in abstracts is not merely a technical requirement but a fundamental ethical responsibility that safeguards the reliability and value of scientific knowledge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B.; data curation, M.Š.C. and D.R.; formal analysis, D.R.; investigation, M.Š.C. and L.R.; methodology, T.D. and L.R.; software, T.D. and A.Ć.; supervision, J.B.; validation, A.Ć.; writing—original draft, M.Š.C.; writing—review and editing, T.D., D.R., L.R., A.Ć. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request to corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sheikh, H.M.; Jha, R.K. Triggered Skin Sensitivity: Understanding Contact Dermatitis. Cureus 2024, 16, e59486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancredi, V.; Buononato, D.; Caccavale, S.; Di Brizzi, E.V.; Di Caprio, R.; Argenziano, G.; Balato, A. New Perspectives in the Management of Chronic Hand Eczema: Lessons from Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesqué, D.; Aerts, O.; Bizjak, M.; Gonçalo, M.; Dugonik, A.; Simon, D.; Ljubojević-Hadzavdić, S.; Malinauskiene, L.; Wilkinson, M.; Czarnecka-Operacz, M.; et al. Differential diagnosis of contact dermatitis: A practical-approach review by the EADV Task Force on contact dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 1704–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, P.M. Skin barrier function. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008, 8, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivic, M.; Slugan, A.; Leskur, D.; Rusic, D.; Seselja Perisin, A.; Modun, D.; Durdov, T.; Bozic, J.; Vukovic, D.; Bukic, J. Efficacy and Safety Assessment of Topical Omega Fatty Acid Product in Experimental Model of Irritant Contact Dermatitis: Randomized Controlled Trial. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Hwang, H.-J.; Seo, W.-D.; Do, S.-H. Oat (Avena sativa L.) Sprouts Restore Skin Barrier Function by Modulating the Expression of the Epidermal Differentiation Complex in Models of Skin Irritation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Salvo, E.; Gangemi, S.; Genovese, C.; Cicero, N.; Casciaro, M. Polyphenols from Mediterranean Plants: Biological Activities for Skin Photoprotection in Atopic Dermatitis, Psoriasis, and Chronic Urticaria. Plants 2023, 12, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malekpour, M.; Etebari, A.; Hezarosi, M.; Anissian, A.; Karimi, F. Mouse Model of Irritant Contact Dermatitis. Iran J. Pharm. Res. 2022, 21, e130881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonitsis, N.G.; Tatsioni, A.; Bassioukas, K.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Allergens responsible for allergic contact dermatitis among children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermat. 2021, 64, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontana, M.; Hansel, K.; Bianchi, L.; Sensini, C.; Malatesta, N.; Stingeni, L. Advancing the understanding of allergic contact dermatitis: From pathophysiology to novel therapeutic approaches. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1184289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litchman, G.; Nair, P.A.; Atwater, A.R.; Bhutta, B.S. Contact Dermatitis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459230/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Uter, W.; Werfel, T.; Lepoittevin, J.-P.; White, I.R. Contact Allergy—Emerging Allergens and Public Health Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak-Bilić, G.; Vučić, M.; Japundžić, I.; Meštrović-Štefekov, J.; Stanić-Duktaj, S.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Irritant and Allergic Contact Dermatitis—Skin Lesion Characteristics. Acta Clin. Croat. 2018, 57, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skiveren, J.G.; Ryborg, M.F.; Nilausen, B.; Bermark, S.; Philipsen, P.A. Adverse skin reactions among health care workers using face personal protective equipment during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey of six hospitals in Denmark. Contact Dermat. 2022, 86, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, S.J.; Van Vogt, E.; Candy, B.; Steele, L.; Reynolds, C.; Stuart, B.; Parker, R.; Axon, E.; Roberts, A.; Doyle, M.; et al. Topical Anti-Inflammatory Treatments for Eczema: A Cochrane Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Clin. Exp. Allergy J. Br. Soc. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 54, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usatine, R.P.; Riojas, M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am. Fam. Physician 2010, 82, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M.O.; Sieborg, J.; Nymand, L.K.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Ezzedine, K.; Schlapbach, C.; Molin, S.; Zhang, J.; Zachariae, C.; Thomsen, S.F.; et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of topical corticosteroid phobia among patients with chronic hand eczema—Findings from the Danish Skin Cohort. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 91, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Ruiz, I.; Gil-Villalba, A.; Navarro-Triviño, F.J. Exploring New Horizons in Allergic Contact Dermatitis Treatment: The Role of Emerging Therapies. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2025, 116, T731–T739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olbrich, H.; Sadik, C.D.; Ludwig, R.J.; Thaçi, D.; Boch, K. Dupilumab in Inflammatory Skin Diseases: A Systematic Review. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Kastl, S.; Battista, T.; Di Guida, A.; Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Ventura, V.; Patruno, C. Effect of Dupilumab on Sexual Desire in Adult Patients with Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis. Medicina 2022, 58, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Clarke, M.; Moher, D.; Wager, E.; Middleton, P.; Altman, D.G.; Schulz, K.F.; CONSORT Group. CONSORT for reporting randomized controlled trials in journal and conference abstracts: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuqbil, R.M.; Aldhubiab, B. Bioadhesive Nanoparticles in Topical Drug Delivery: Advances, Applications, and Potential for Skin Disorder Treatments. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, M.; Andrews, M.; Wilson, R.; Callender, D.; O’Malley, P.G.; Douglas, K. Reporting quality of randomised controlled trial abstracts among high-impact general medical journals: A review and analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, F.; Deng, L.; Kau, C.H.; Jiang, H.; He, H.; Walsh, T. Reporting quality of randomized controlled trial abstracts: Survey of leading general dental journals. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1939 2015, 146, 669–678.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speich, B.; Schroter, S.; Briel, M.; Moher, D.; Puebla, I.; Clark, A.; Maia Schlüssel, M.; Ravaud, P.; Boutron, I.; Hopewell, S. Impact of a short version of the CONSORT checklist for peer reviewers to improve the reporting of randomised controlled trials published in biomedical journals: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, R.; Shan, W.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Evaluating the completeness of the reporting of abstracts since the publication of the CONSORT extension for abstracts: An evaluation of randomized controlled trial in ten nursing journals. Trials 2023, 24, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Ravaud, P.; Baron, G.; Boutron, I. Effect of editors’ implementation of CONSORT guidelines on the reporting of abstracts in high impact medical journals: Interrupted time series analysis. BMJ 2012, 344, e4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhie, M.L.; Bridgman, A.C.; Voineskos, S.H.; Chan, A.W.; Drucker, A.M. Reporting of randomized controlled trial abstracts in dermatology journals according to CONSORT-A guidelines. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 185, 673–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).