1. Introduction

Water hardness is primarily characterized by elevated concentrations of polyvalent cations, notably Calcium (Ca

2+) and Magnesium (Mg

2+) ions [

1]. While other polyvalent ions, such as Aluminum (Al

3+), Iron (Fe

2+), Strontium (Sr

2+), Zinc (Zn

2+), and Manganese (Mn

2+), can also contribute to hardness, their concentrations in natural waters are typically significantly lower than those of Ca

2+ and Mg

2+. The quantitative assessment of water hardness is conventionally based on the total concentration of Ca

2+ and Mg

2+, expressed in parts per million (ppm) or milligrams per liter (mg/L) [

2,

3]. The origin of water hardness is predominantly geological, arising from the interaction of water with soil and rock formations. As rainwater permeates the earth’s surface, it dissolves various minerals, leading to the accumulation of dissolved solids in natural water bodies. Total hardness is specifically defined as the cumulative concentration of Calcium and Magnesium, conventionally expressed as milligrams of Calcium Carbonate (CaCO

3) per liter (mg/L). The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies water into four main categories: soft water (≤60 mg/L), moderately hard water (60–120 mg/L), hard water (120–180 mg/L), and very hard water (>181 mg/L) [

1,

4]. In India, the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) specifies a permissible limit for hardness ranging from 300 to 600 mg/L. Despite India’s considerable water resources, increasing population density, expanding irrigation activities, and rapid industrialization exert substantial pressure on available water supplies. A recent report by the Central Ground Water Board, Government of India 2024, highlighted that elevated total hardness levels are prevalent in groundwater across many regions of the country, with some areas exhibiting concentrations exceeding 600 mg/L (

https://cgwb.gov.in/cgwbpnm/public/uploads/documents/17363272771910393216file.pdf, accessed on 27 December 2024).

Hard water significantly impacts skin health, contributing to various issues including an increased risk of atopic eczema (AE) [

5], higher prevalence of eczema [

6] and xerosis [

7]. Mineral ions in hard water react with soap fatty acids to form insoluble metallic soap, disrupting the skin barrier and raising IgE levels [

8]. Hard water exacerbates dryness and redness, reduces hydration [

9], and directly impacts the skin by disrupting its natural epidermal gradient, affecting keratinocyte differentiation [

10,

11], inhibiting epidermal repair [

12], and disrupting the bilayer lipid water barrier [

13]. Hard water’s alkalinity and buffering capacity can modify skin surface pH, altering epidermal enzyme activity (e.g., LEKTI, which is pH-sensitive and crucial for barrier function) [

14]. In terms of strength and elasticity, hard water mineral deposits can increase hair porosity and brittleness, making it more susceptible to breakage, especially when wet or during styling [

15]. The surface of hard water treated hair has a ruffled appearance with higher mineral deposition and decreased thickness when compared with the surface of distilled water treated hair [

16]. Hard water decreases strength of hair and thus increases breakage [

17]. Besides skin and hair health, hard water presents a significant challenge in various applications, including the effective use of cosmetic products. The elevated levels of these minerals can interfere with the intended function of soaps, face cleansers, shampoos, conditioners, and other personal care items, potentially diminishing their efficacy and altering their sensory attributes.

In the cosmetics industry, lather, or foam, plays a significant role in the user experience and perception of product effectiveness, though it is not a direct indicator of cleansing ability [

18,

19,

20]. A good lather enhances the sensory experience, making products feel more luxurious and effective. Liquid foams are colloidal systems in which a discontinuous gas phase is dispersed in a continuous liquid phase, giving rise to a multitude of gas bubbles [

21]. These bubbles can be either closely packed together forming the characteristic “cellular structure” of the foam, or float freely in the liquid [

22]. Much of the usefulness and appeal of liquid foams lies in their rheological properties. They combine the properties of an elastic solid at low stress with those of a liquid when the yield stress is exceeded [

23]. Hard water can significantly impact the foaming properties of cosmetic products by reducing foamability due to the precipitation of surfactants [

24]. For example, SDS solutions in hard water exhibit lower initial foam volumes compared to deionized water [

25,

26]. The impact of hard water on foam in cosmetic applications has significant implications for product development and cosmetic manufacturers must consider the water quality in target markets when formulating products. For example, in regions with hard water, formulations may require higher surfactant concentrations or the use of surfactant blends to maintain desired foam properties [

27,

28]. High ionic strength generally acts to destabilize both surfactant-stabilized foams and charged colloidal systems by screening electrostatic repulsions, leading to thinner films and faster drainage in foams, and increased aggregation in colloids [

29,

30,

31]. Given these well-documented detrimental impacts of hard water on skin and hair health, and its pervasive presence in many regions globally, it is critically important for the cosmetics industry to understand how its products interact with such water conditions. Consumers in hard water areas rely on cleansing and care products to maintain skin and hair health, and if these products themselves are compromised by water quality, their intended benefits are diminished. This fundamental challenge to both product performance and consumer well-being forms the core rationale for our investigation into the effects of hard water on cosmetic foams.

Looking at the importance of foams in cosmetics and the impact that hard water may have on the foam, the primary purpose of this study is to systematically investigate and characterize the differences in foam properties generated by two leading marketed cosmetic products—a face cleanser and a hair shampoo—under hard and soft water conditions. This study’s specific aims are as follows:

- (a)

Quantitatively assess and compare key foam analysis parameters, including foam volume and stability, under varying water hardness.

- (b)

Analyze the microscopic characteristics of the foam, specifically examining bubble counts and area, to understand the structural implications of hard water.

- (c)

Evaluate the rheological and tribological properties of the foams produced, providing insights into their texture, feel, and performance under different water conditions.

By conducting these detailed investigations, this study seeks to provide robust empirical evidence regarding the direct influence of water hardness on the functional performance and sensory attributes of common cosmetic products, thereby offering valuable insights for product development and consumer understanding in regions affected by hard water.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hard Water Preparation

Hard water was prepared as per the OECD guideline [

32]. To prepare 1 L of 375 ppm OECD hard water, 600 mL of de-ionized water (DI) was taken in a 1000 mL volumetric flask and added 6.0 mL of OECD Hard Water Solution A and then 8.0 mL of OECD Hard Water Solution B. The solution was mixed, and DI water was added to the flask to make up the volume. The pH of the sample should be 7.0 ± 0.2 at room temperature.

Hard water Solution A. 19.84 g anhydrous magnesium chloride (or 42.36 g MgCl2·6H2O) and 46.24 g anhydrous calcium chloride (CaCl2) was dissolved in DI water and diluted to 1000 mL. The solution was sterilized by membrane filtration. The solution was stored in the refrigerator and used for up to one month.

Hard Water Solution B. 35.02 g of sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) was dissolved in DI water and diluted to 1000 mL. The solution was sterilized by membrane filtration. The solution was stored in the refrigerator and used for up to one month.

2.2. Cosmetic Samples

Two marketed competitor products, a face cleanser and a hair shampoo (containing water, blend of anionic/amphoteric/non-ionic surfactants, rheology modifiers, chelating agents and fragrances) were procured for the characterization of foam they create in soft and hard water.

Hair Shampoo composition: Aqua, Sodium Lauryl Sulfate, Sodium Laureth Sulfate, Cocamidopropyl Betaine, Glycol Distearate, Dimethicone, Sodium Citrate, Cocamide MEA, Sodium Xylenesulfonate, Parfum, Citric Acid, Sodium Benzoate, Sodium Chloride, Guar Hydroxypropyltrimonium Chloride, Glycerin, Tetrasodium EDTA, Trisodium Ethylenediamine Disuccinate, Polyquaternium-6, Linalool, Hexyl Cinnamal, Panthenol, Panthenyl Ethyl Ether, Magnesium Nitrate, Methylchloroisothiazolinone, Magnesium Chloride, Methylisothiazolinone.

Face cleanser composition: Water, Triethanolamine, Myristic Acid, Lauric Acid, Glycerin, Cocamidopropyl Betaine, Lauryl Phosphate, Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose, Ehtylparaben, Methylparaben, Propylparaben, Phenoxyethanol, Fragrance, O-Cymen-5-Ol (Isopropyl Methtylphenol), Benzophenone-4, Butylated Hydroxy Toluene

Foam was prepared by mixing these samples to a 1.5% concentration with hard or soft water. Hard water was prepared to as per the OECD protocol mentioned above while deionized water (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA, CAS no. 7732-18-5) was used as a representative for soft water without further purification.

2.3. Equipment and Methods

The generation and stability of foam are primary attributes influencing the perceived efficacy and sensory experience of cleansing products like face cleansers and hair shampoos. A rich, stable foam is often associated with effective cleaning and a luxurious feeling. Therefore, measuring initial foam volume and its decay over time (stability) directly correlates with consumer expectations and product performance. Beyond macroscopic volume, the microscopic structure of foam (bubble size and quantity) is crucial. Smaller, more numerous bubbles typically indicate a finer, more stable foam that feels creamier and richer. Analyzing bubble counts and mean bubble area provides direct evidence of structural degradation. For cosmetic products, a shear-thinning behavior is highly desirable: high viscosity at low shear (prevents dripping from packaging) and lower viscosity at high shear (allows smooth spreading during application). Evaluating this under hard and soft water conditions reveals if water hardness alters the product’s fundamental “feel” and ease of use. The frictional properties of foams directly relate to tactile sensations like “slipperiness,” “smoothness,” “creaminess,” and “rinse-feel.” By combining tribology with foam analysis and rheology, the study provides a holistic view of how hard water impacts foams. Foam analysis testing was performed on a KRÜSS DFA100—Dynamic Foam Analyzer. For the foam height and structure analysis, the instrument was fitted with the SH4511 sparging cradle, FL4551 filter, and CY4572 prism column (50 mL volume). The camera height was set to 100 mm, at proximal position. Rheological analysis was performed using a DHR-2 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) fitted with a 40 mm crosshatched parallel plate and advanced Peltier plate, test gap set to 2 mm. Solvent trap covers were employed to minimize atmospheric exposure of the sample at the geometry edge.

2.3.1. Foam Analysis Test Procedure

Air was sparged through the liquid at a rate of 0.3 L/min for 30 s, followed by a 600 s measuring period. Foam height and bubble size distribution were analyzed. The test was performed in duplicate.

2.3.2. Rheological Analysis

The following rheological measurements were made on foams that were prepared using the same setup and procedure described above: Air was sparged through the liquid at a rate of 0.3 L/min for 30 s. An aliquot of this foam was removed and placed onto the rheometer for analysis.

Shear Rate Sweeps: The foam was exposed to a shear rate sweep, 0.1 1/s to 1000 1/s, logarithmically scaled, 4 points per decade of shear rate, shear applied for 20 s at each rate with viscosity calculated over the final 10 s of each step.

Oscillation Stress Sweeps: The foam was exposed to an oscillatory stress sweep ranging from 0.1 Pa to 1000 Pa, 1 Hz oscillation frequency. A step termination was set such that if at any point the oscillation strain exceeded 1500% the test would immediately end. Testing was performed on the foam immediately following foam 3 production, and 5 min after foam production. Both of these tests were performed in duplicate.

2.3.3. Tribological Analysis

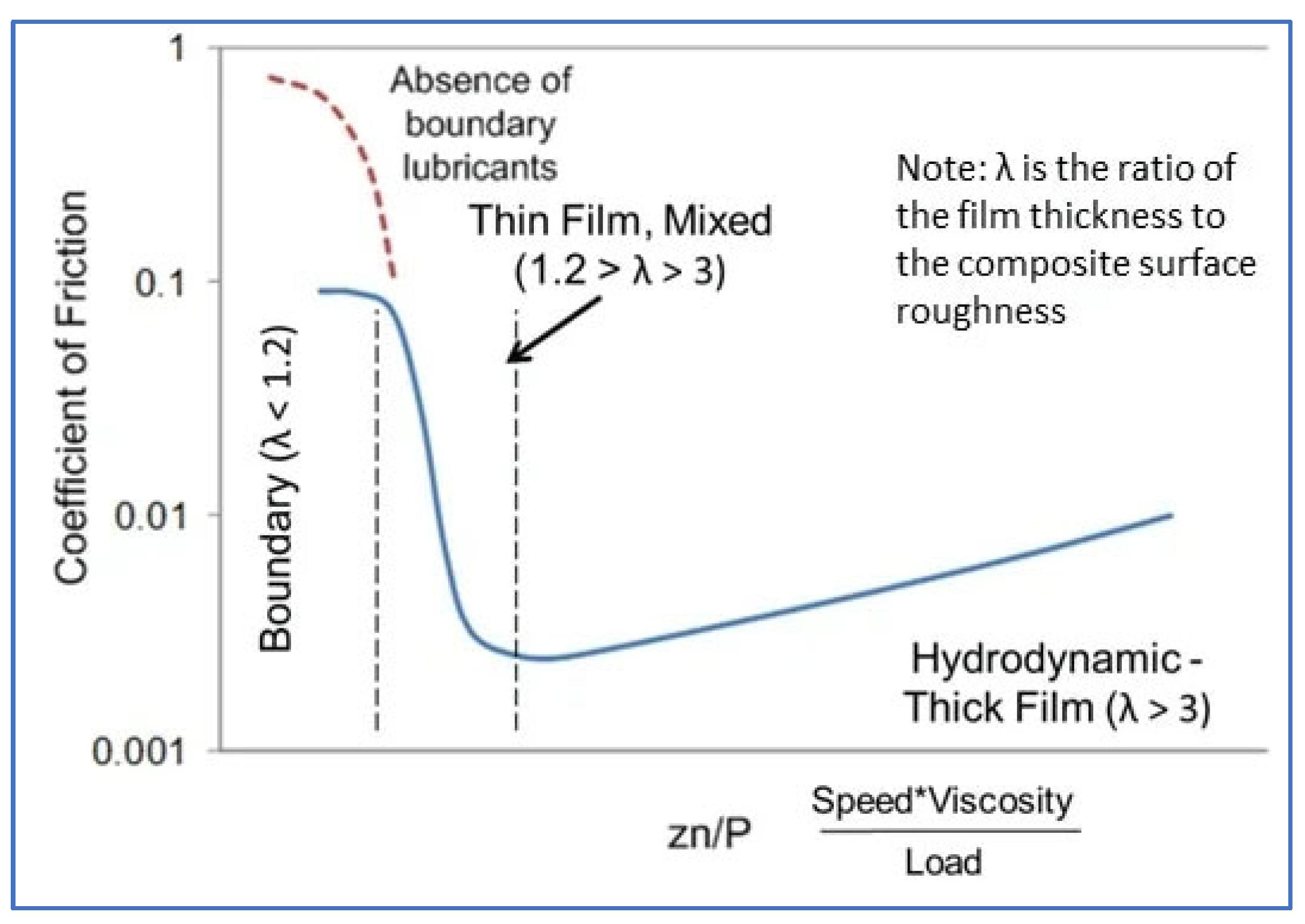

The foam was loaded onto a silicone substrate immediately after foam production. A defined axial load of 1 N was imposed, and the angular velocity was swept from 0.05 mm/s to 20 mm/s. Coefficient of friction was calculated as the ratio of sliding force to load force and plotted as a function of sliding speed. A plot illustrating the frictional characteristics of a liquid lubricant, under conditions such as mixed and hydrodynamic regimes and boundary, is known as the Stribeck curve. Each of the regimes is defined by the ratio between the surface roughness and the film thickness (illustrated conceptually in

Figure 1). This curve characterizes the frictional behavior of lubricants delineating three key regimes:

Boundary Lubrication: At low sliding speeds, surfaces are in direct contact, and lubrication is minimal, leading to higher friction.

Mixed Lubrication: As speed increases, the lubricant begins to be entrained between the surfaces, leading to a reduction in friction.

Hydrodynamic Lubrication: At high speeds, a complete fluid film separates the surfaces, resulting in the lowest friction.

Testing was performed in duplicate; the lower substrate was held at 32 °C throughout.

3. Results

3.1. Foam Analysis

The ability of face cleansers and hair shampoos to generate and maintain a stable foam is crucial for consumer perception and product performance.

Table 1, focusing on the initial (0 s) and final (600 s) foam volumes, provides a quantitative measure of foam generation and, more importantly, its stability over a ten-minute period.

The stability of foam, a critical attribute for consumer perception and performance of cleansing products, was significantly influenced by water hardness, as demonstrated by the contrasting foam decay profiles presented in

Table 1. For both the face cleanser and hair shampoo formulations, a pronounced reduction in foam volume was observed when tested in hard water conditions compared to soft water. Specifically, the face cleanser exhibited a substantial foam decay of ~38% in hard water, nearly 2.4 times greater than the 16% decay measured in soft water. Similarly, the hair shampoo experienced a ~35% foam decay in hard water, approximately 1.8 times higher than its 19% decay in soft water. These findings underscore the well-documented challenges posed by metal ions present in hard water, which can interact with surfactants, leading to the precipitation of insoluble salts and a consequent destabilization of the foam structure. The consistent pattern of increased foam decay in hard water across both product categories highlights the importance of considering water quality in the formulation and evaluation of cleansing products to ensure optimal consumer experience and product efficacy across diverse geographical regions.

Table 2 provides crucial insights into the stability and drainage characteristics of the two compositions under water hardness conditions, specifically focusing on the drainage half-life. The drainage half-life, defined as the time at which the liquid portion reaches 50% of its initial value, is a direct indicator of foam stability. A longer half-life signifies a more stable foam that retains its liquid content for a longer duration.

These results consistently demonstrate that foams generated in soft water exhibit significantly longer drainage half-lives compared to those in hard water for both product types. Specifically, the face cleanser in soft water maintained its foam structure for an average of 165 s before half of its liquid drained, a nearly 3.4-fold increase compared to the 48.9 s observed in hard water. Similarly, the hair shampoo foam in soft water displayed a mean drainage half-life of 160 s, which is approximately 1.8 times longer than its 89.9 s in hard water. This disparity highlights the detrimental impact of hard water ions on the stability of the liquid films that constitute the foam, likely through interaction with surfactants that lead to thinning and eventual rupture of the lamellae. These findings reinforce the notion that water quality plays a paramount role in dictating the physical stability and longevity of foam, directly impacting the perceived richness and effectiveness of cleansing products during use.

3.2. Bubble Analysis

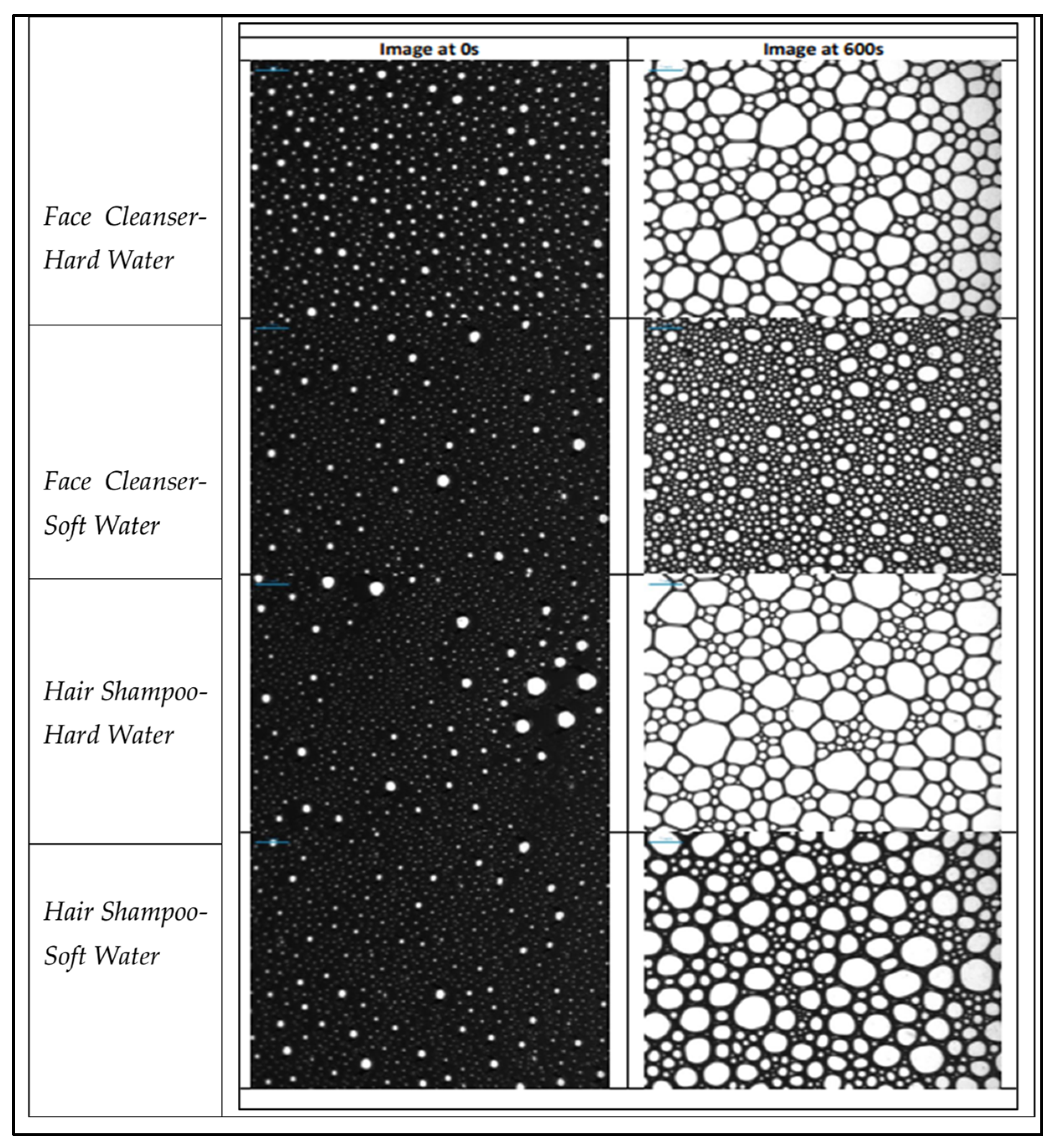

Beyond the macroscopic measures of foam volume and drainage, the analysis of bubble count density provides a crucial microscopic understanding of foam quality and stability, directly influencing the consumer’s tactile experience of richness and creaminess (

Table 3).

At initial formation (0 s), all samples demonstrated a relatively high bubble count, suggesting the generation of a fine-textured foam. However, significant differences emerged in the foam’s ability to maintain this fine structure over time, particularly influenced by water hardness. Both the face cleanser and hair shampoo experienced a dramatic reduction in bubble count per square millimeter after 600 s when tested in hard water. For instance, the face cleanser in hard water saw its bubble count plummet from 75.9 to a mere 5.06, indicating extensive bubble coalescence and rupture. Similarly, the hair shampoo in hard water exhibited a drastic decrease from 107 to 4.81 bubbles/mm2. In stark contrast, soft water conditions preserved the fine bubble structure much more effectively. The face cleanser in soft water retained a substantial 52.8 bubbles/mm2 from an initial 94.6, demonstrating remarkable stability at the micro-level. The hair shampoo in soft water also performed significantly better than in hard water. These findings underscore that hard water not only reduces overall foam volume but fundamentally compromises the delicate bubble structure, leading to a coarser, less stable foam that would likely be perceived as less luxurious and effective by the user.

The mean bubble area in

Table 4 presents a quantitative measure of foam texture and stability, as significant increases typically indicate bubble coalescence and coarsening, which negatively impact perceived foam quality. At initial foam generation (0 s), both Face Cleanser and Hair Shampoo consistently produced fine bubbles, with initial mean areas ranging from 9400 to 13,200 µm

2. This uniformity suggests effective initial foam formation across all tested conditions (hard and soft water). However, the evolution of these bubble structures over 600 s was drastically influenced by water hardness. In hard water conditions, both formulations experienced a profound increase in mean bubble area, signaling extensive bubble coalescence. For instance, the Face Cleanser in hard water saw its mean bubble area swell from 13,200 µm

2 to 198,000 µm

2—an approximate 15-fold increase. Similarly, the Hair Shampoo in hard water exhibited an even more dramatic expansion, from 9400 µm

2 to 209,000 µm

2, nearly a 22-fold increase. This stark enlargement of bubble size points to significant film thinning and rupture, leading to rapid bubble aggregation and a coarse, unstable foam structure. In sharp contrast, soft water conditions preserved the fine bubble architecture. The Face Cleanser in soft water maintained decent stability, with its mean bubble area increasing only from 10,600 µm

2 to 19,000 µm

2. While the Hair Shampoo in soft water also showed better performance than in hard water, its final mean bubble area of 83,100 µm

2 indicates more considerable bubble growth compared to the Face Cleanser in soft water. However, it will not be prudent to compare Face Cleanser with Hair Shampoo as their compositions are very different. These findings underscore that hard water not only diminishes foam volume and count but fundamentally compromises the microscopic integrity of the foam, leading to larger, less stable bubbles. A microscopic image of the foam bubbles generated by the two formulations in both soft and hard water both immediately and after 10 min is shown in

Figure 2 indicating lower bubble counts and higher bubble area with hard water as quantified and represented in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

3.3. Rheology of the Foam

3.3.1. Controlled Rate Viscosity Profile

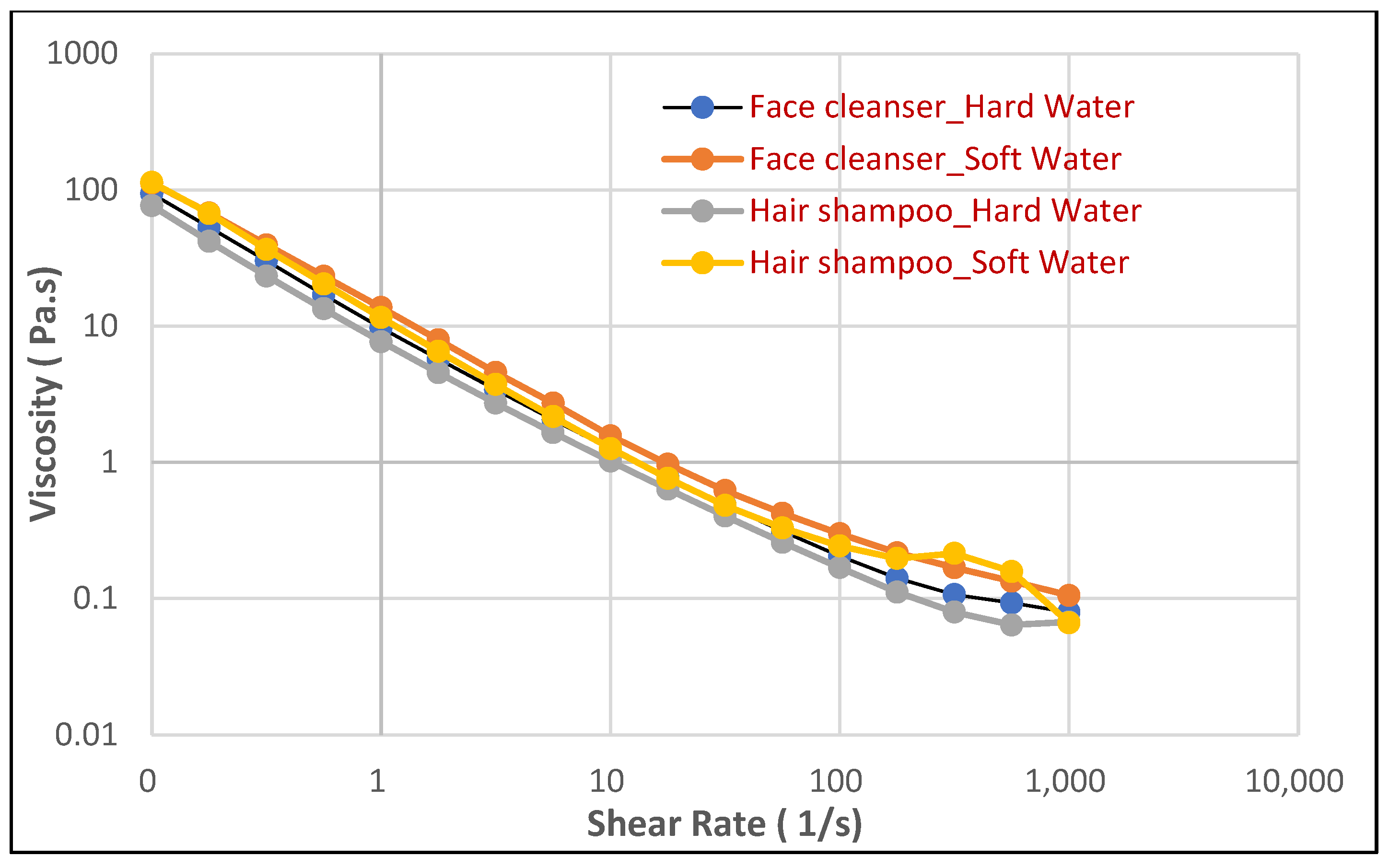

The controlled rate viscosity profile, which elucidates the relationship between viscosity and shear rate, is crucial for understanding the flow behavior of foams and predicting their performance during dispensing and application. The controlled rate viscosity profiles presented in

Figure 3 offer insights into the flow behavior of the foams generated from both the face cleanser and hair shampoo formulations under varying water hardness conditions.

Across all samples, a consistent non-Newtonian, shear-thinning behavior was observed, characterized by a decrease in viscosity with increasing shear rate. This rheological property is highly desirable for personal care products as it allows for easy dispensing from packaging (where shear rates are low, leading to higher apparent viscosity, preventing dripping) and smooth spreading during application (where high shear rates reduce viscosity, facilitating distribution across the skin or hair).

Interestingly, in contrast to the significant impact observed on foam stability, drainage, and structural integrity, the viscosity profiles themselves appeared largely unaffected by water hardness for both the face cleanser and the hair shampoo. The curves for hard water and soft water for each product are remarkably similar, showing almost-overlapping trends across the entire range of shear rates. This suggests that while hard water severely compromises the inherent stability and mechanical resilience of the foam structure (as evidenced by reduced foam volume, faster drainage, and lower complex moduli), it does not substantially alter the overall bulk flow properties of the freshly generated foam under controlled shear. Furthermore, the viscosity profiles of the face cleanser and hair shampoo foams are also quite similar to each other, indicating that both products generate foams with comparable handling and spreading characteristics irrespective of water quality. This finding implies that the consumer’s initial tactile perception of the product’s “thickness” or “spreadability” might not be immediately impacted by water hardness, even as the foam’s ability to sustain itself is significantly diminished.

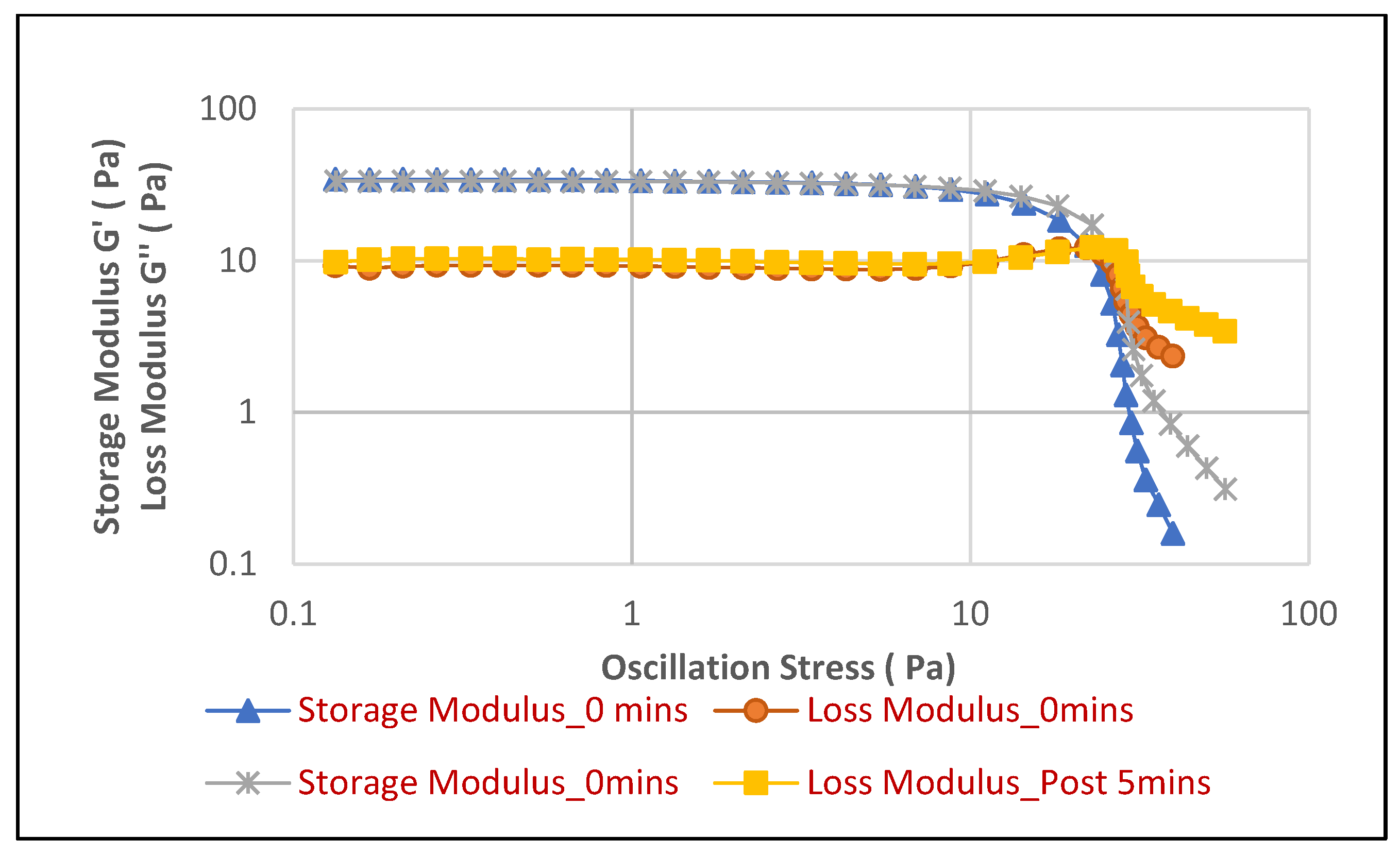

3.3.2. Stress Sweep Test

The analysis of the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) provides a detailed rheological fingerprint of the foam’s viscoelastic properties, revealing its elastic (solid-like) and viscous (liquid-like) behavior under stress, and thus its structural integrity and stability. The storage modulus (G′) represents the elastic, solid-like component of the foam, indicating its ability to store deformation energy, while the loss modulus (G″) reflects its viscous, liquid-like component, signifying energy dissipation. A foam is considered more stable and solid-like when G′ significantly dominates G″ over a wide range of oscillation stresses.

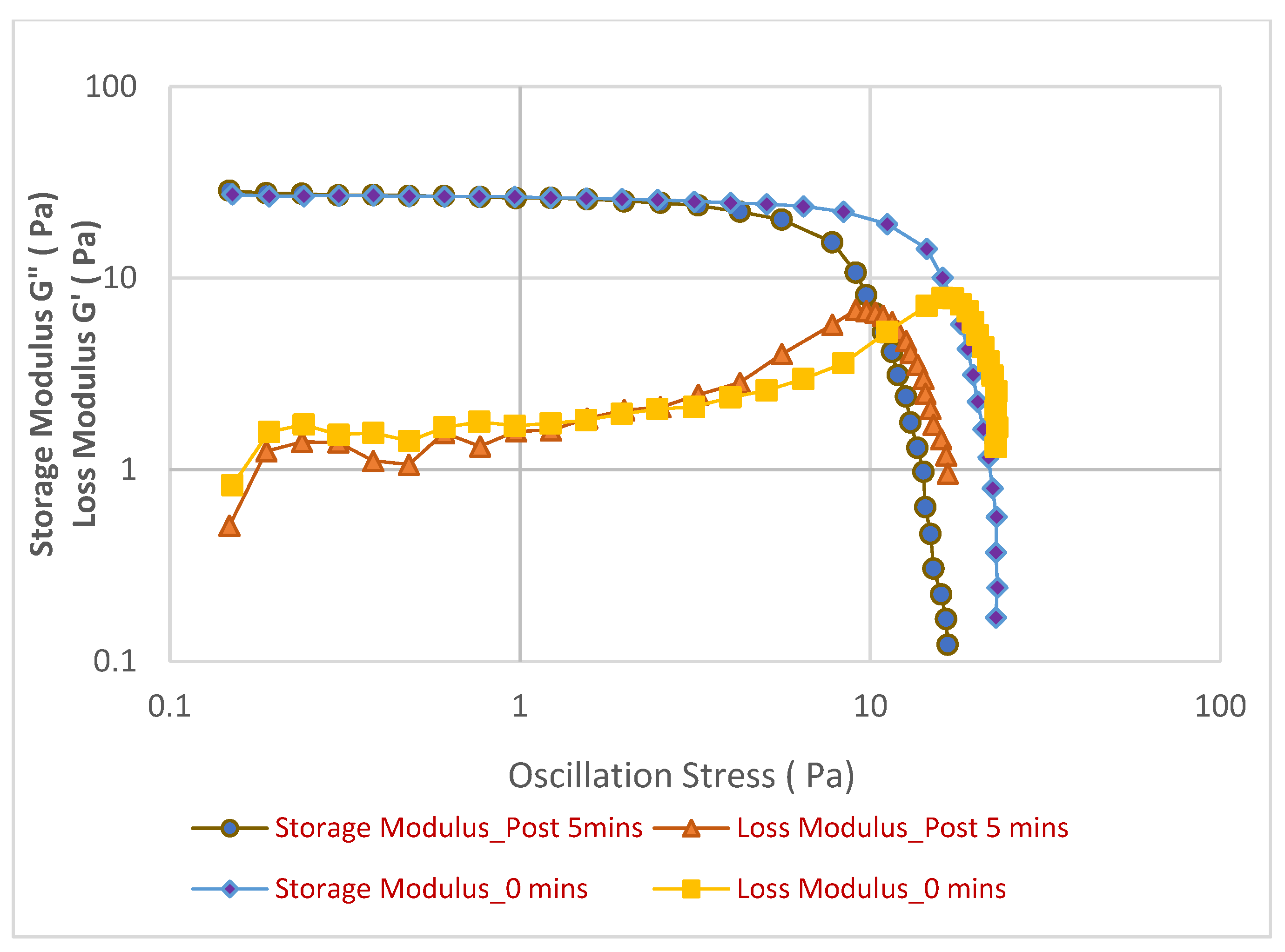

Figure 4 illustrates the behavior of the face cleanser foam in soft water, while

Figure 5 depicts its performance in hard water, both immediate and 5 min post-creation.

Upon comparing the rheological profiles of the face cleanser foam in soft water (

Figure 4) versus hard water (

Figure 5), distinct differences emerge that suggest a more stable and consistently performing foam in soft water. In soft water, the foam exhibits a highly consistent and robust elastic structure, evidenced by the Storage Modulus (G′ ) values for both “0 min” and “Post 5 min” being nearly identical across the entire stress sweep. This indicates that the foam’s elastic strength and its resistance to structural breakdown remain unchanged over time. The yield point, where G′ sharply drops, occurs consistently at approximately 10 Pa for both time points.

In contrast, while the initial elastic strength (G′ at “0 min”) in hard water appears slightly higher, around 25–30 Pa, compared to soft water, the foam’s stability over time is subtly compromised. Specifically, the G′ curve for “Post 5 min” in hard water shows a slightly earlier yield point, occurring around 7–8 Pa, compared to the “0 min” measurement at approximately 10 Pa. This subtle but noticeable shift indicates a minor reduction in the foam’s resilience and its ability to withstand stress after a 5 min period in hard water. Therefore, despite potentially starting with a slightly higher initial rigidity, the face cleanser foam in soft water demonstrates superior long-term stability and a more consistent elastic performance, maintaining its structural integrity more reliably over time under applied stress compared to its behavior in hard water.

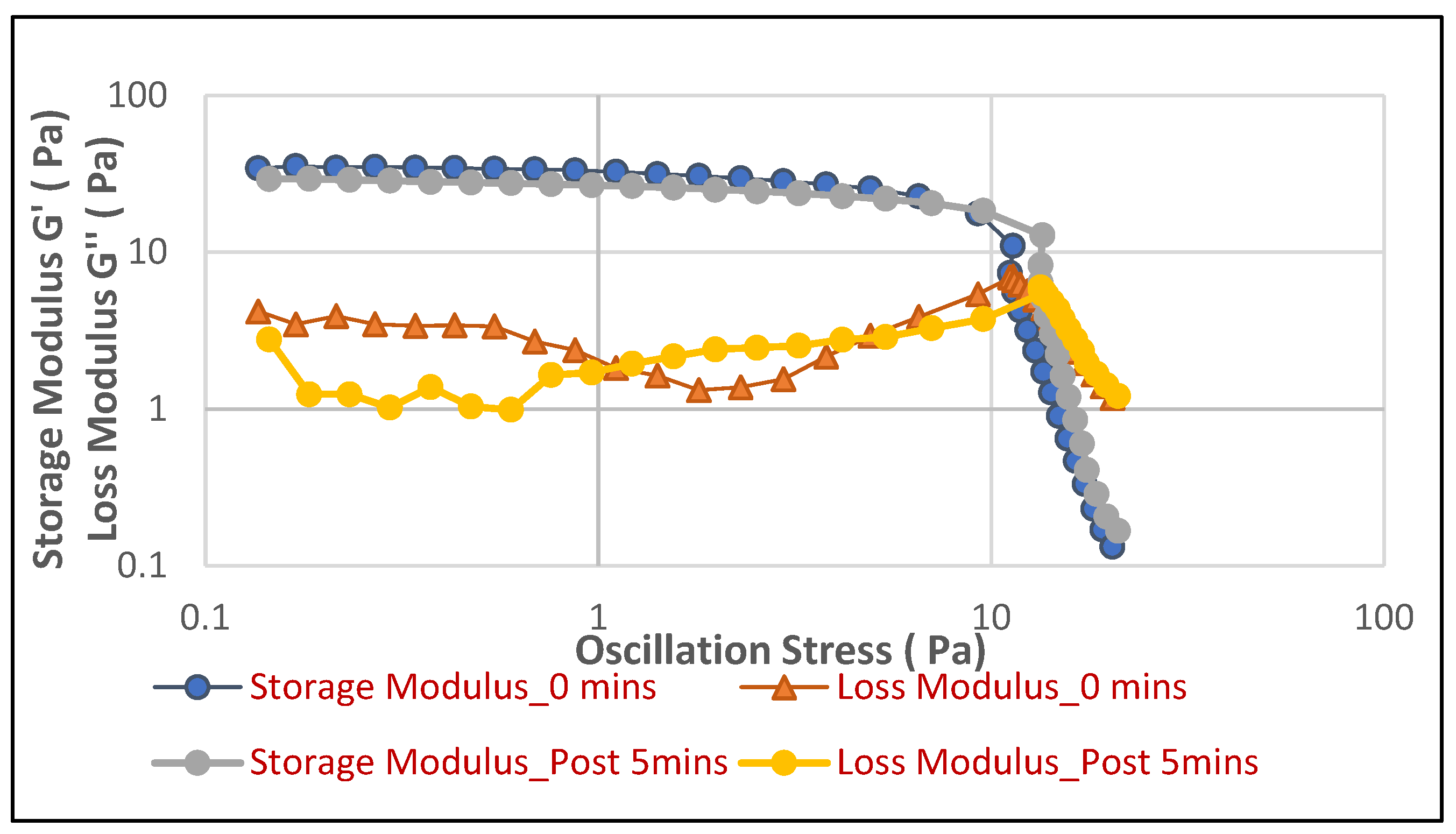

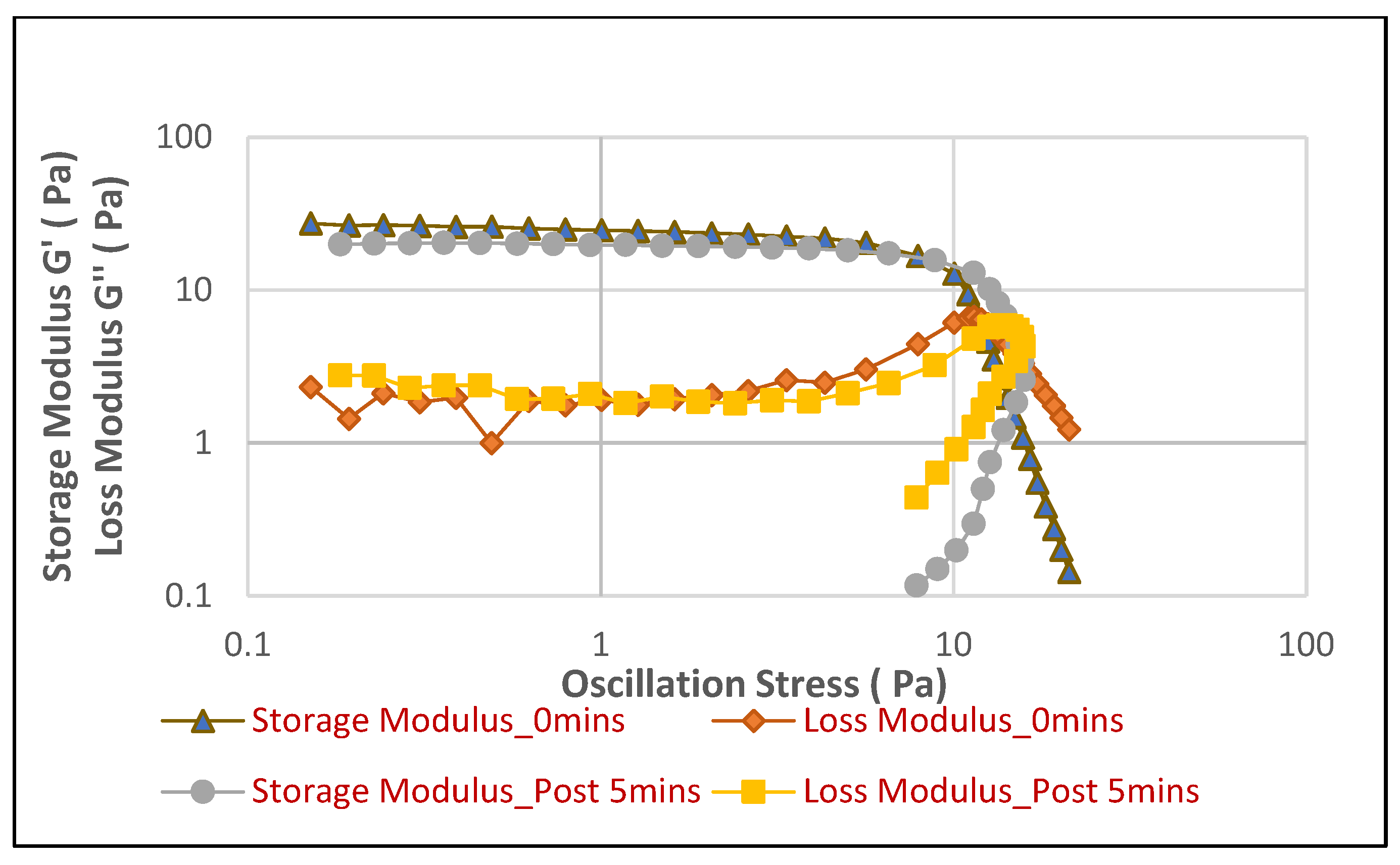

Figure 6 illustrates the behavior of the hair shampoo foam in soft water, while

Figure 7 depicts its performance in hard water, both immediate and 5 min post-creation.

In soft water conditions (

Figure 6), the hair shampoo foam demonstrates superior mechanical stability. The storage modulus (G′) maintains a high plateau of approximately 30–40 Pa in the linear viscoelastic region, consistently dominating the loss modulus (G″). This strong elastic response indicates a well-structured, solid-like foam capable of effectively resisting deformation. The foam maintains this robust structure up to considerably high oscillation stresses (around 30–40 Pa) before G′ begins to decline and G″ eventually crosses over, marking the yield point. Furthermore, the G′ and G″ profiles for both immediate and 5 min measurements are remarkably similar, suggesting that the foam’s elastic and viscous properties are highly stable over time, maintaining its integrity after creation. Conversely, the hair shampoo foam generated in hard water (

Figure 7) exhibits a significantly compromised rheological profile. The initial plateau value of G′ is notably lower, ranging from approximately 15–20 Pa, and its dominance over G″ is much less pronounced. More critically, the G′ values begin to decrease and G″ crosses over G′ at much lower oscillation stresses (typically between 10 and 20 Pa), indicating a considerably lower yield stress and a rapid transition from elastic to predominantly viscous behavior. This early crossover signifies that the foam in hard water yields and flows much more easily under mechanical stress, dissipating more energy than it stores. A slight degradation in G′ for the 5 min hard water sample compared to the immediate one also suggests a temporal weakening of the foam structure in the presence of hard water ions. These rheological findings are highly consistent with the previously observed macroscopic instabilities (reduced foam volume and accelerated drainage) and microscopic changes (increased bubble coarsening) in hard water, collectively affirming that hard water fundamentally undermines the internal network and mechanical resilience of the hair shampoo foam.

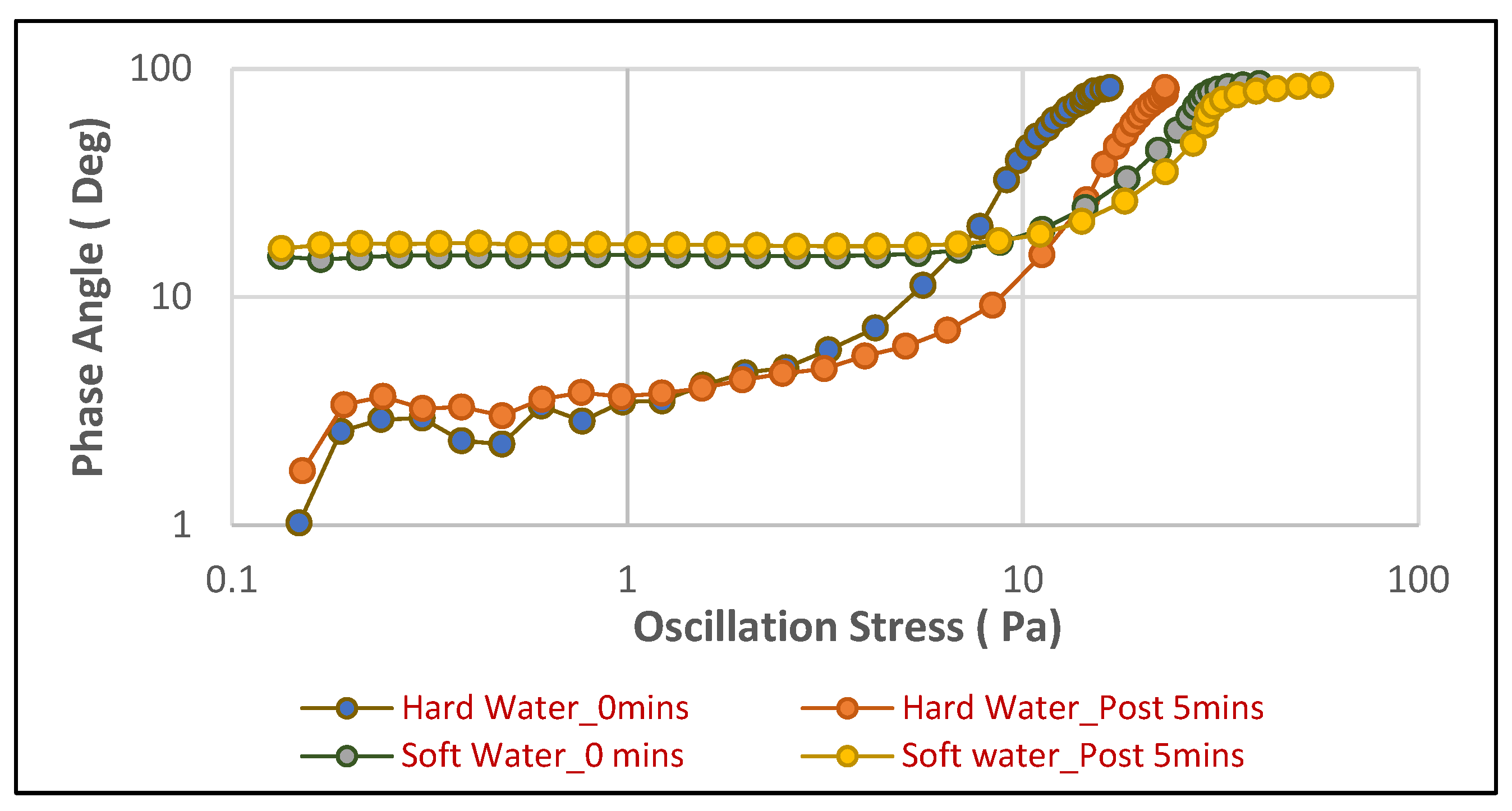

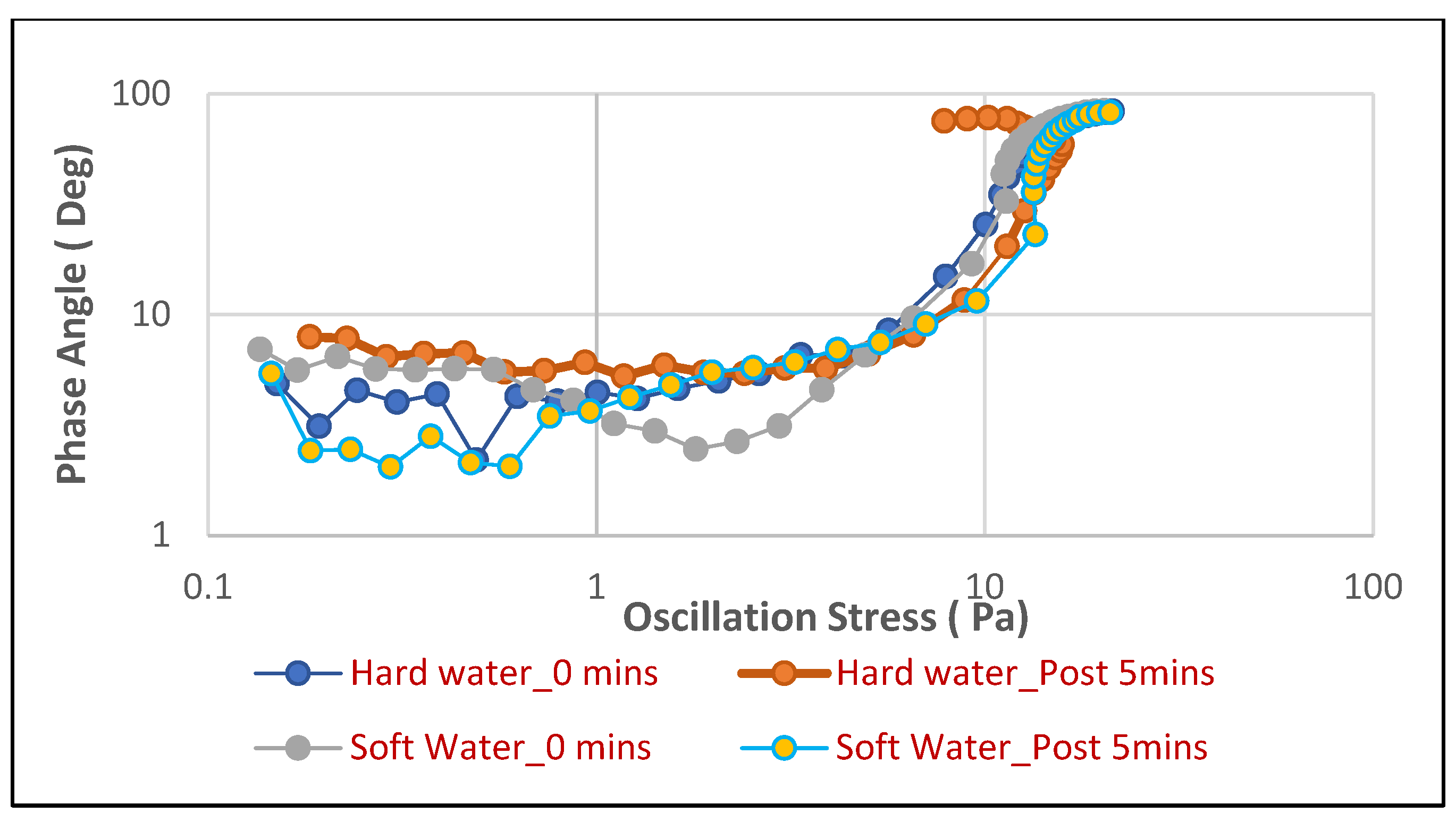

The phase angle (δ) provides a critical rheological metric, indicating the balance between the elastic (solid-like) and viscous (liquid-like) behavior of a foam. A lower phase angle signifies a more elastic and stable foam structure, while an increase in phase angle points towards a more viscous, less resilient system.

Figure 8 illustrates the phase angle for the face cleanser foam, and

Figure 9 for the hair shampoo foam, both under varying water hardness conditions and over time.

A consistent and pronounced impact of water hardness on the viscoelastic properties of foams is evident across both product types. For the face cleanser (

Figure 8), foams generated in soft water consistently maintain a low phase angle, typically between 15 and 20 degrees, across a broad range of oscillation stresses. This indicates a highly elastic, solid-like structure that effectively resists deformation. The overlap of the immediate and 5 min soft water curves further emphasizes the temporal stability of this robust foam. In stark contrast, face cleanser foam in hard water (orange and red lines) exhibits significantly higher initial phase angles (around 30–40 degrees), indicating a more viscous nature from the outset. Crucially, as oscillation stress increases, the phase angle for hard water foams rapidly rises, approaching 90 degrees at relatively low stresses (10–20 Pa), signifying a swift and complete transition to a liquid-like behavior, indicating a fragile and easily deformable structure.

Similarly, for the hair shampoo (

Figure 9), soft water conditions lead to foams with generally low and stable phase angles (around 5–10 degrees at lower stresses), reflecting a predominantly elastic character. While there is some fluctuation in the hair shampoo soft water curves, they largely maintain a much lower phase angle compared to their hard water counterparts, especially at higher stresses. Conversely, hair shampoo foams in hard water exhibit higher phase angles from the beginning and show a more rapid increase towards 90 degrees with increasing oscillation stress. This indicates that hard water also causes the hair shampoo foam to become more viscous and less elastic, yielding more readily under stress.

This widespread increase in phase angle across both products in hard water directly correlates with the previously observed macroscopic foam volume decay, accelerated drainage, and microscopic bubble coarsening. These results collectively highlight that hard water fundamentally compromises the integrity of the lamellar films, reducing their elasticity and causing the foam to behave like an unstable liquid that readily breaks down under mechanical stress, profoundly impacting the consumer’s perception of lather quality and richness.

3.4. Tribology of the Foam

Rheology studies the flow and deformation of films of materials separating surfaces in relative motion. Tribology, on the other hand, is the study of the friction, lubrication and wear of interacting surfaces—in other words, surfaces in close contact. Unlike rheology testing, where the sample under test is held in a defined gap between surfaces moving relative to each other, tribology testing entails bringing those surfaces into contact under a defined pressure and sliding one against the other, measuring the frictional drag over a range of sliding speeds.

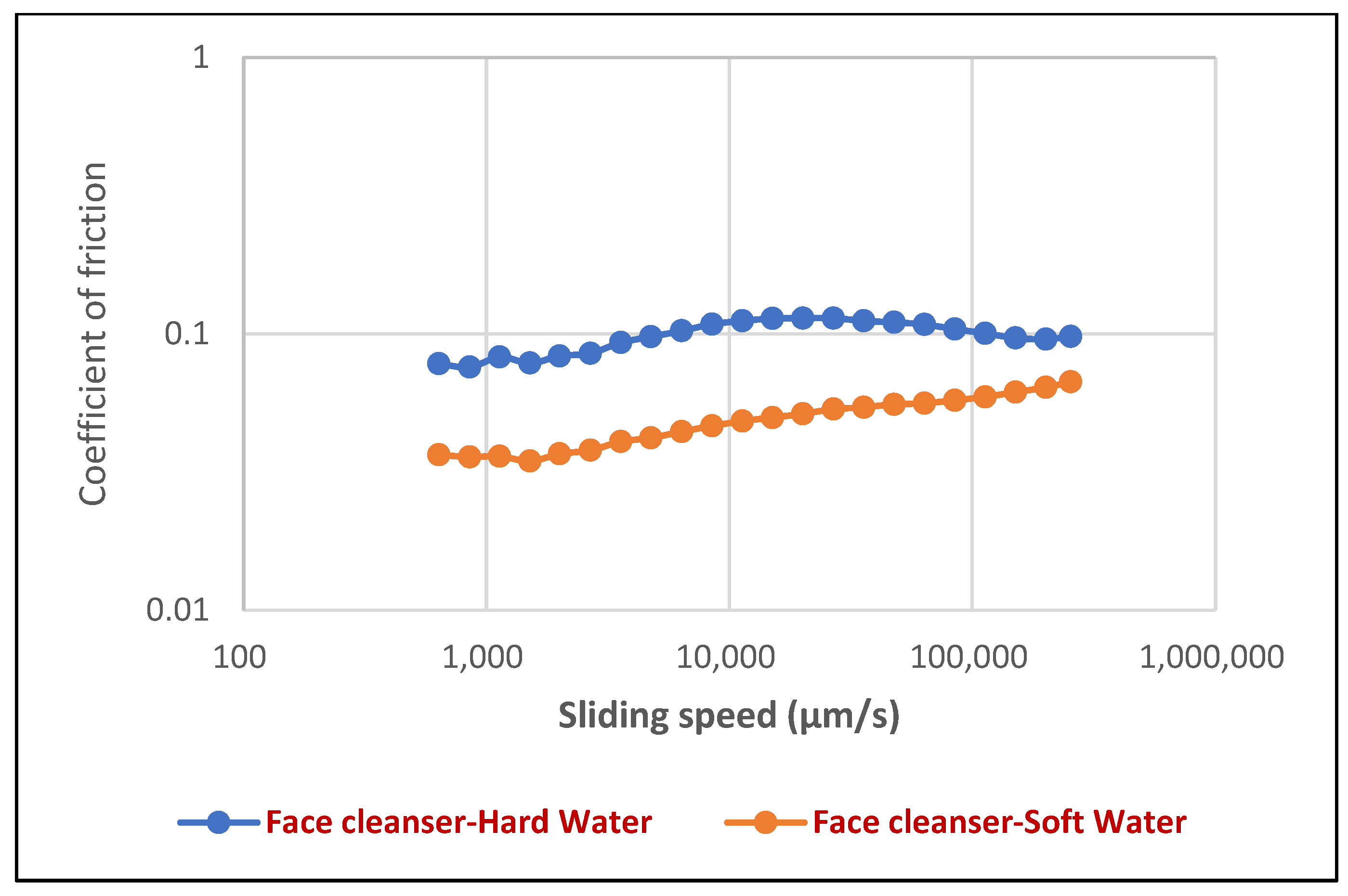

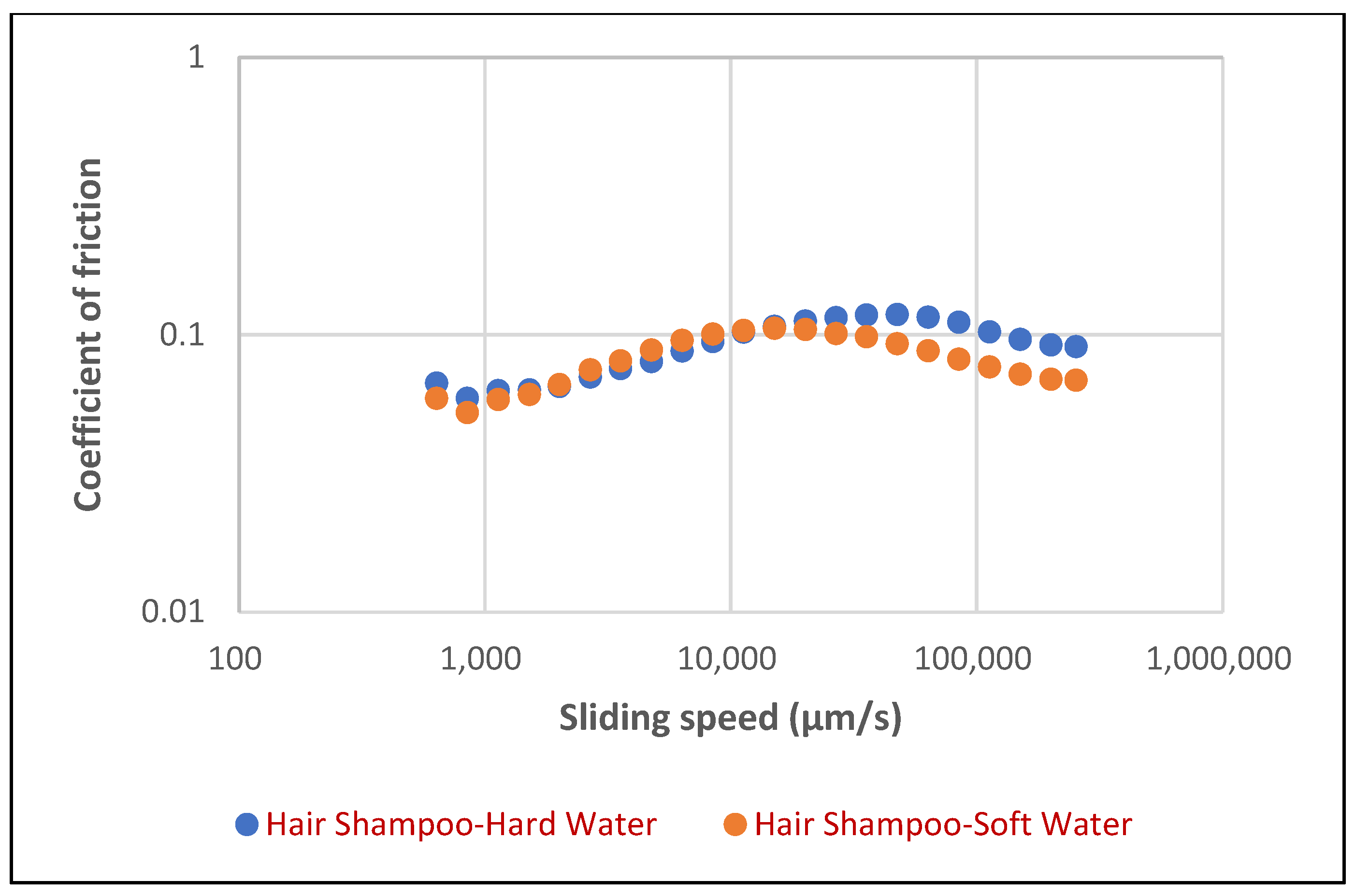

The tribological characterization of foam systems, specifically for face cleanser and hair shampoo formulations, revealed distinct behaviors influenced by both sliding speed and water hardness, as depicted in

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

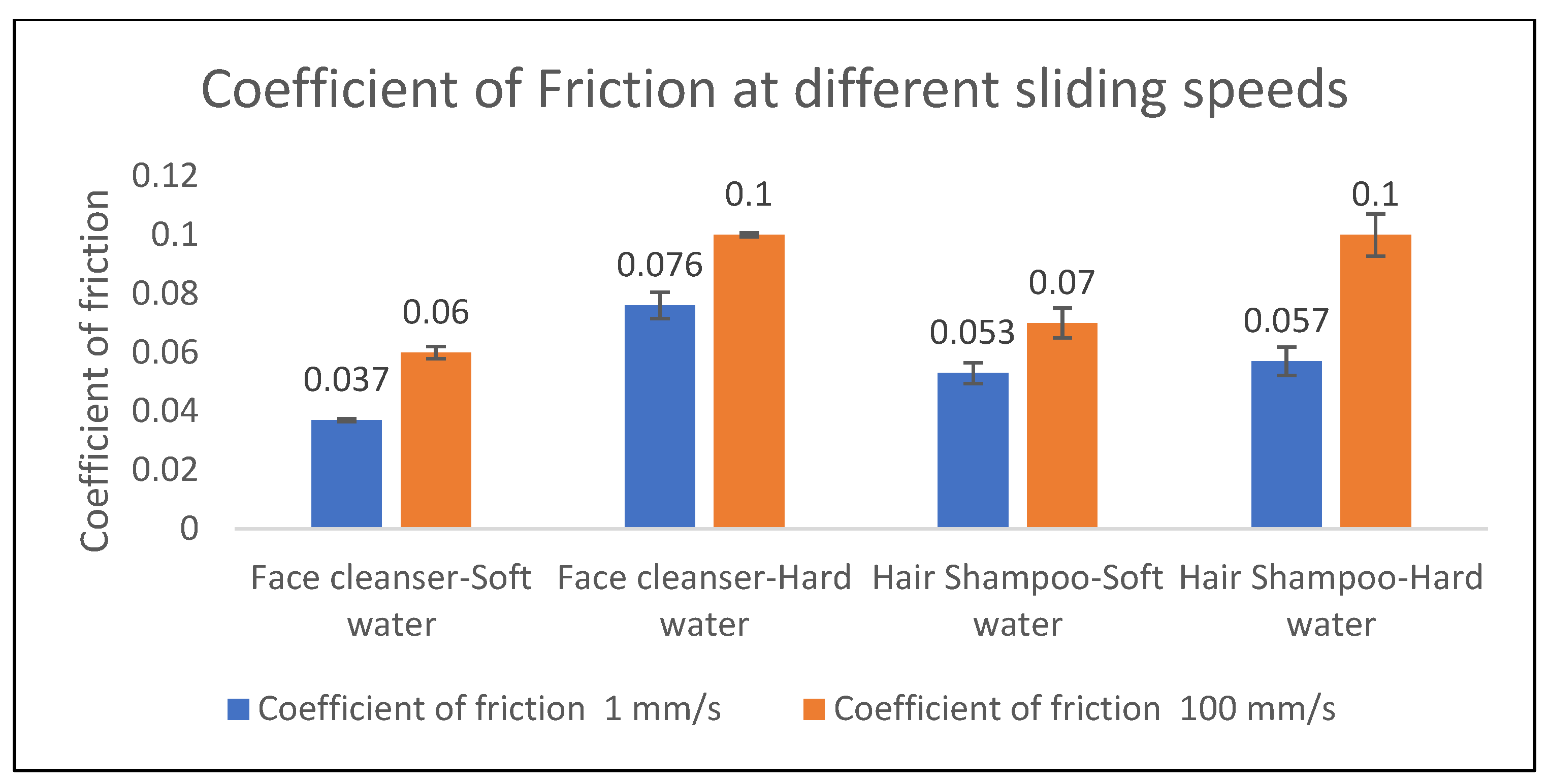

For the face cleanser foam (

Figure 10), a clear trend emerged where the coefficient of friction generally increased with rising sliding speed, ranging from approximately 100 to 100,000 µm/s, before showing a slight plateau or minor decrease at the highest speeds. Crucially, the presence of hard water consistently resulted in a higher coefficient of friction compared to soft water across the entire velocity spectrum, indicating a significant impact of water mineral content on the frictional properties of face cleanser foam. Typical coefficient of friction values for the face cleanser ranged from about 0.08 to 0.12 in hard water and 0.05 to 0.10 in soft water. Specifically, as shown in

Figure 12, the face cleanser in hard water exhibited a CoF of 0.076 at 1 mm/s and 0.1 at 100 mm/s. These values were notably higher than the 0.037 and 0.06 observed in soft water at the same respective speeds, representing an increase of approximately 105% at 1 mm/s and 67% at 100 mm/s.

In contrast, the hair shampoo foam (

Figure 11) exhibited a more complex tribological profile. Its coefficient of friction initially increased with sliding speed, reaching a distinct peak in the intermediate speed range, roughly between 10,000 and 30,000 µm/s, after which it progressively decreased. In contrast to face cleanser, the hair shampoo (

Figure 12) showed a more nuanced response to water hardness. While hard water did result in slightly higher CoF values (0.057 at 1 mm/s and 0.091 at 100 mm/s) compared to soft water (0.053 at 1 mm/s and 0.07 at 100 mm/s), the difference was less pronounced, particularly at lower sliding speeds (an increase of about 7.5% at 1 mm/s). While hard water often showed a slightly higher coefficient of friction at lower speeds, the differences diminished and even converged or slightly inverted at higher sliding velocities. The coefficient of friction for hair shampoo foam generally ranged from approximately 0.06 to 0.11, demonstrating a more speed-dependent lubrication mechanism compared to the face cleanser foam. These findings highlight the inherent differences in the tribological performance of these cosmetic foam systems, underscoring the importance of formulation and environmental factors like water hardness in determining their frictional characteristics. Further investigation into the specific mechanisms of surfactant–ion interaction and the rheological properties of these foams under shear could provide deeper insights into their unique tribological fingerprints.

4. Discussion

The performance and sensory attributes of cleansing products, particularly their lathering/foaming characteristics, are paramount to consumer satisfaction. This investigation comprehensively examined the impact of water hardness on various facets of foam stability and rheology for a face cleanser and a hair shampoo, providing insights from macroscopic observations down to microscopic structural changes and mechanical properties. The collective findings robustly demonstrate that water hardness is a critical determinant of foam quality, consistently leading to a degradation across all measured parameters.

Macroscopically, the foams exhibited significant instability in hard water. Both the face cleanser and hair shampoo showed a pronounced increase in foam decay percentage and substantially shorter drainage half-lives when tested in hard water compared to soft water. This degradation is primarily driven by the direct interaction of divalent cations with the anionic headgroups of the surfactants present in both formulations. These multivalent ions readily bind with negatively charged surfactant molecules, leading to the formation of insoluble precipitates and effectively reducing the concentration of active surfactants available to stabilize the air–water interfaces. Furthermore, these cations screen the electrostatic repulsion between surfactant headgroups, thereby weakening the interfacial film. This physical collapse signifies the inability of the foam structure to retain liquid and maintain its volume over time in the presence of hard water. These macroscopic observations are directly corroborated and elucidated by microscopic analysis of the foam structure. In hard water, foams from both products experienced a dramatic reduction in bubble count per square millimeter and a concurrent, massive increase in mean bubble area over 10 min. This observation is a direct consequence of the weakened and less elastic lamellar films, which are less effective at resisting rupture. The loss of functional surfactant and reduced electrostatic repulsion, caused by hard water ions, diminishes the interfacial viscoelasticity of the films, rendering them unable to self-heal or withstand mechanical stresses. This leads to accelerated gravitational drainage and subsequent film rupture, facilitating bubble coalescence. This indicates extensive bubble coalescence and rupture, leading to a much coarser and less dense foam structure [

33]. Conversely, in soft water, both products maintained significantly higher bubble counts and smaller mean bubble areas, signifying superior resistance to coarsening and better preservation of the delicate bubble architecture. This direct correlation between water hardness and microscopic structural degradation underscores that the physical instability observed macroscopically stems from a fundamental compromise of the individual bubble films.

Rheological characterization further elucidated the mechanical properties and structural resilience of the foams. In soft water, where surfactant functionality is preserved, the foams consistently exhibited high storage modulus values that dominated the loss modulus across a broad range of oscillation stresses, signifying a predominantly elastic, solid-like network with strong structural integrity. This robust viscoelastic behavior is attributed to the well-ordered and highly elastic surfactant layers at the air–water interfaces, which enable the foam lamellae to store deformation energy effectively and resist rupture. Overall amplitude sweep analyses revealed that foams in soft water consistently exhibited higher complex modulus (G*) values in their linear viscoelastic region and withstood significantly greater oscillation stresses before yielding. This points to a more robust, elastic foam network capable of resisting external mechanical forces [

34]. Delving deeper into the viscoelastic components, the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) analyses provided a clear distinction. In soft water, for both the face cleanser and hair shampoo, G′ consistently dominated G″ throughout a broad range of oscillation stresses, maintaining high plateau values and indicating a predominantly elastic, solid-like foam structure that effectively stores mechanical energy [

35]. The stability of these G′ and G″ profiles over 5 min further confirmed the temporal integrity of the foam in soft water. Conversely, in hard water, the interaction of divalent cations with surfactants fundamentally destabilizes the interfacial films, leading to a profoundly compromised rheological profile. The initial G′ values were lower, and critically, the loss modulus (G″) either became comparable to or rapidly surpassed G′ at much lower oscillation stresses. This early crossover of G″ over G′ signifies a transition to a predominantly viscous, liquid-like behavior, indicating that the foam dissipates more energy than it stores and is highly prone to structural breakdown and flow under minimal stress [

36]. This rheological fragility in hard water directly underpins the observed physical instability. The phase angle (δ) analyses provided an additional, compelling perspective on this viscoelastic shift. In soft water, both the face cleanser and hair shampoo foams maintained low phase angles, reflecting their highly elastic and resilient nature [

37]. These low phase angles persisted across a wide range of stresses, signifying robust structural integrity. However, in hard water, both products exhibited higher initial phase angles and, more critically, a rapid and steep increase in phase angle as oscillation stress increased. This rapid shift towards 90 degrees (purely viscous behavior) at relatively low stresses unequivocally demonstrates that hard water causes the foam to lose its elastic character rapidly, behaving more like a fluid under mechanical deformation.

All samples exhibited a typical shear-thinning behavior, where viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate. The overlapping viscosity curves for hard and soft water suggest that while hard water severely compromises the internal structure and resilience of the foam, it does not substantially alter the overall flow behavior of the freshly generated foam under controlled shear. This implies that the initial sensory perception related to product dispensing and spreadability might be consistent across water types, even as the subsequent foam stability dramatically differs.

The tribological properties of foam systems, as exemplified by the face cleanser and hair shampoo formulations, are intricate and significantly influenced by both sliding speed and the chemical composition of the aqueous medium. Our findings reveal distinct tribological profiles for each product, underscoring the importance of formulation in dictating interfacial friction. In hard water, the formation of insoluble surfactant–cation complexes reduces the lubricating efficiency of the foam films. These precipitates can increase the effective roughness at the interface, thereby increasing frictional resistance. The overall thinning and weakening of the foam lamellae, as evidenced by microscopic and rheological data, compromise their ability to sustain a robust lubricating film, shifting the tribological regime towards boundary lubrication and increasing direct surface contact.

The general increase in CoF with sliding speed for the face cleanser may indicate a transition from a more boundary-lubricated regime at lower speeds to a mixed-lubrication regime, where the increasing shear forces lead to less effective film formation or increased resistance to shear within the foam structure itself [

38]. The less pronounced effect of water hardness on the CoF of the hair shampoo foam suggests a more robust or less ion-sensitive surfactant system within its formulation. Hair shampoos often contain different types of surfactants, polymers, and conditioning agents that may be more resilient to hard water ions, either by chelating them or by forming more stable foam structures that maintain their lubricating properties irrespective of water hardness. The observed differences in tribological behavior between the face cleanser and hair shampoo foams highlight the tailored formulation strategies for these personal care products. The relatively consistent and higher friction for face cleansers in hard water might be perceived as a less “slippery” or “squeaky clean” feel, which could be desirable for a cleansing product.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the investigation comprehensively highlights that water hardness significantly compromises foam stability across all hierarchical levels, from macroscopic volume retention and drainage to microscopic bubble integrity and macroscopic rheological and tribological performance. The presence of hard water ions fundamentally weakens the internal foam structure, leading to accelerated bubble coalescence, increased liquid drainage, and a critical loss of elastic, solid-like mechanical properties, causing the foam to behave more like an unstable liquid. This multi-faceted approach encompassing macroscopic, microscopic, rheological, and tribological analyses provides a robust and unprecedented understanding of this widespread phenomenon. This fundamental insight is invaluable for developing next-generation cosmetic products that deliver consistent efficacy and superior sensory attributes in diverse global water conditions, ultimately enhancing consumer satisfaction and minimizing product waste due to poor performance. These findings also emphasize the critical importance for researchers to consider water quality, particularly hardness, when developing cleansing products to ensure optimal product efficacy. Additionally, leveraging foam boosters and rheology modifiers can enhance foam stability and integrity to ensure consumer satisfaction and product performance across diverse water qualities.