Abstract

Growing concern about the environmental impact of traditional packaging has driven the development of biodegradable edible films made from natural and functional biopolymers. Various by-products generated during harvesting can be subjected to valorization. Potato, a tuber with high starch content, and carrot, rich in β-carotene, represent important sources of polymeric matrix and bioactive compounds, respectively. Similarly, the use of biodegradable plasticizers such as pectin and polysaccharides derived from nopal mucilage is a viable alternative. This study assessed the physical and chemical properties of edible films composed of potato starch (PS), cactus mucilage (NM), carrot extract (CJ), citrus pectin (P), and glycerin (G). The films were produced by means of casting, with three mixtures prepared that had different proportions of CJ, P, and PS. The experiments were adjusted to a simple mixture design, and the data were analyzed in triplicate, using Pareto and Tukey diagrams at 5% significance. Results showed that adding CJ (between 5 to 6%), P (between 42 to 44%) and PS (between 43 to 45%) significantly affects all of the evaluated physical and chemical properties, resulting in films with luminosity values greater than 88.65, opacity ranging from 0.20 to 0.54 abs/mm, β-carotene content up to 26.11 μg/100 g, acidity between 0.22 and 0.31% and high solubility with a significant difference between treatments (p-value < 0.05) and low water activity (around of 0.47) (p-value > 0.05). These characteristics provide tensile strength up to 5.7 MPa and a suitable permeability of 1.6 × 10−2 g·mm/h·m2·Pa (p-value < 0.05), which ensures low diffusivity through the film. Similarly, increasing the CJ addition enables the functional groups of the other components to interact. Using carrot extract and potato starch is a promising approach for producing edible films with good functional qualities but with high permeability.

1. Introduction

Due to their smaller size and shape during harvest, residues from tubers, roots, and cereals represent an underutilized source with high potential for recovery, accounting for around 5 to 15% of total production [1,2,3]. These materials contain bioactive and functional compounds of industrial interest, which can be extracted and used in the formulation of biopolymers, edible coatings, antioxidant additives, or natural colorants. Their use not only reduces post-harvest losses but also promotes the circular economy by reintroducing by-products into value chains. Additionally, it contributes to agricultural sustainability by developing technological alternatives with lower environmental impact and increased resource efficiency.

In the current context, there is growing concern about the environmental impact of the waste generated by conventional food packaging, which has driven the search for materials with biodegradable properties. At the same time, the increasing demand for functional and healthy foods has highlighted the need to develop innovative packaging technologies [4,5]. In this sense, biodegradable edible films constitute a technologically viable alternative, which are formulated from biopolymers of natural origin. These packages, in addition to being environmentally sustainable, significantly contribute to preserving the organoleptic properties and extending the shelf life of food products by controlling humidity, oxygen, and other environmental factors that deteriorate food quality [6,7,8,9].

Various structural materials have been used in the production of edible films. These include polysaccharides (starch, cellulose, chitosan, pectin, gum arabic, agar, carrageenan, and alginate), as well as their modifications, which offer high transparency or opacity and good gas barrier properties, although they have low water resistance. Proteins (gelatin, casein, soy protein, gluten, and casein) also provide good mechanical strength and adhesion. Similarly, lipids (waxes, essential oils, and oils) form films with an excellent moisture barrier but low mechanical strength. Each structural material confers different properties to the film and is generally applied in mixtures to achieve good cohesiveness of the polymer network [8,10,11,12]. However, films require improved properties such as color, density, flexibility, texture, strength, stability, bioactivity, and response to external and internal (intelligent) agents. Therefore, additives such as plasticizers (glycerol, sorbitol, mannitol, polyethylene glycol (PEG), sugars), gums and hydrocolloids (xanthan gum, guar gum, tara gum, gellan gum, locust bean gum), emulsifiers and surfactants (lecithin, monoglycerides, polysorbates), bioactive compounds (polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, natural antimicrobials), crosslinking agents (organic acid salts), and fillers or nanofillers (nanocellulose and clays) are used [12,13,14]. The selection of raw materials greatly influences the quality features of the films, such as their barrier properties, mechanical strength, and biodegradability [15], in addition to promoting environmental care through the use of synthetic materials. However, their high production costs and limited performance compared to synthetic films make using other bio-based materials challenging for science and technology [11,16,17].

The development of edible films from natural products such as potato starch (Solanum tuberosum), nopal mucilage (Opuntia ficus indica) and carrot extract (Daucus carota), has proven to be a good alternative to reduce environmental impact, while valuing the potential of agricultural products that are also abundant, accessible and rich in bioactive compounds that can be used in the formulation of these biopolymers [10,11,16,17,18,19]. Potato starch forms films with good elasticity and transparency [20,21]. Nopal mucilage, on the other hand, has gelling, emulsifying, and moisturizing properties and is rich in polysaccharides with antioxidant capacity, as well as providing plasticity and gas barrier properties [21,22,23]. Likewise, carrot juice stands out for its high content of β-carotene, a compound with recognized antioxidant activity and nutritional properties [24,25]. While the use of pectin, due to its gelling capacity, allows the creation of three-dimensional networks that serve as support for the film, limiting the permeability to oxygen and carbon dioxide, in addition to being compatible with other biopolymers [23,26].

Carrots are widely cultivated vegetables with low nutritional requirements. Discarded carrots, such as those that are misshapen or very small, can be revalued as raw material for obtaining functional extracts rich in β-carotene (provitamin A), vitamins B and C, and minerals [27,28]. Carotenoids provide nutritional value and have antioxidant properties. They are ideal for extending the shelf life of food covered by films and for providing attractive colors [25]. These bioactive compounds can interact with other components of edible films, potentially improving barrier properties and flexibility. The use of discarded carrots contributes to a circular economy and sustainable production processes in edible films [29,30].

The incorporation of plant extracts rich in natural pigments and antioxidant compounds, in addition to providing bioactive properties, also modifies optical and physicochemical aspects of films, such as color, opacity, and solubility [31]. In particular, color is an essential attribute for consumer acceptance and can be significantly influenced by carotenoid concentration [32]. Likewise, β-carotene content can be used as an indicator of the antioxidant functionality and stability of films under storage conditions. Furthermore, the solubility of edible films is related to the material’s resistance to humid environments and its performance as a coating or envelope [9,17,33,34,35].

These raw materials, such as potato starch, carrot extract, and cactus mucilage, come from vegetable sources that have little economic value. For example, the starch is extracted from discarded potatoes and carrots. Cacti are also plants that have no commercial or nutritional use in these areas of the Peruvian Andes. These aspects are considered competitive advantages in the production of edible films.

In this regard, the study aims to develop edible films with different proportions of carrot extract, potato starch, and pectin, with a fixed portion of nopal mucilage and glycerin. After elaboration, the physical properties (color, opacity, tension, permeability, water solubility, and water activity) and chemical properties (acidity and β-carotene content) are evaluated. The work aims to provide evidence on the viability of these materials as a sustainable and functional option for the food packaging industry, promoting the use of underutilized, accessible, and low-impact resources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Raw Materials

Analyte grade chemicals such as sodium hydroxide, phenolphthalein, ethanol 99.9%, acetone, hexane 99.0% (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), citric acid, and 60% esterification citric pectin (Spectrum, Gardena, CA, USA) were used. Potato starch (Solanum tuberosum andigena) with an apparent amylose content of 42.09 ± 0.11% was provided by the Laboratorio de Investigación en Materiales para el Tratamiento de Aguas y Alimentos (LIMTA), fron the Universidad Nacional José María Arguedas, Perú, which was obtained from discarded potatoes of the Amarilla Reyna variety, grown in the Champaccocha Population Center, Andahuaylas, Peru.

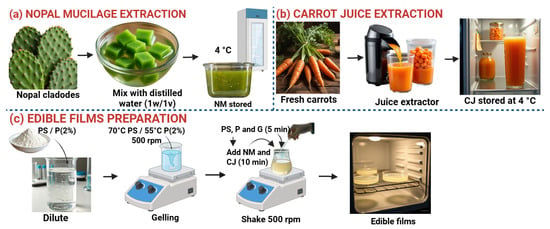

2.2. Nopal Mucilage Extraction

Fresh nopal (Opuntia ficus indica) cladodes were selected, and the spines were manually removed. They were washed with distilled water to remove impurities. They were then carefully peeled and cut into cubes of approximately 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm. The pieces were placed in distilled water in a 1:1 (w/w) ratio and left to stand for 24 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the mixture was filtered, and the mucilage (NM) was obtained and stored at 4 °C until use [21]. The characteristics of the mucilage were pH 4.57 ± 0.01, 0.18 ± 0.01% as malic acid, 1.53 ± 0.15 °Brix, and color: L 74.07 ± 0.64, a* −2.70 ± 1.21, b* 4.93 ± 0.92.

2.3. Carrot Extract Extraction

Discarded fresh carrots (Daucus carota) were collected from fields in the district of Talavera in Andahuaylas, Peru (7.33 ± 0.35 °Brix, 0.23 ± 0.01% as malic acid, and 28.51 ± 3.04 maturity index that indicates commercial maturity). They were thoroughly washed with distilled water, then peeled and chopped. A domestic juice extractor was used to obtain the extract (pH 6.70 ± 0.13, color: L 36.23 ± 0.64, a* 41.80 ± 2.87, b* 46.67 ± 2.46, and β-Carotenes 25.46 ± 2.58 mg/100 g of extract), which was sieved through mesh No. 50. The juice (CJ) was stored refrigerated at 4 °C until it was incorporated in the preparation of edible films.

2.4. Edible Film Production

A 2% w/v starch solution was prepared in distilled water and gelled at 70 °C with stirring at 500 rpm for 20 min (PS). In parallel, a 2% w/v pectin solution (P) was prepared in distilled water at 55 °C under similar conditions. Once both solutions were cooled, edible films were formulated according to the proportions indicated in Table 1. These formulations were proposed based on the fact that PS and P act as a structural matrix, as has been used in numerous trials [36]. The amounts of CJ allow for the development of an adequate color with the addition of β-carotene (a functional antioxidant), and they obey previous tests that allowed for the film’s maneuverability. G and MN in these fixed amounts are used when the base matrix is PS [36,37]. The proportions of the components (by volume) are fixed based on the structural polymer PS. The mixture was prepared in 100 mL containers, first incorporating PS, followed by P and glycerin (G) with stirring at 500 rpm for 5 min. NM and CJ were then added and stirred for another 10 min. The mixture was allowed to stand for 30 min at room temperature, then poured into 135 mm diameter glass molds and placed in an oven at 65 °C for 24 h. Finally, the films were placed in a desiccator at 48% relative humidity (Figure 1) [38,39].

Table 1.

Formulations for preparing edible films.

Figure 1.

Preparation of edible films. Source: Authors’ own work.

2.5. Opacity and Color Determination

Film sheets of 12 mm × 45 mm were cut, and absorbance was measured at 600 nm in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Genesys 150 model, Waltham, MA, USA). Opacity was calculated by dividing absorbance by film thickness (Abs/mm) [40].

Regarding color, the edible films were cut into 50 mm × 45 mm sheets and were taken to a colorimeter (Konica Minolta, CR-5 model, Tokyo, Japan), and readings were taken in L a* b* space. The yellow index (YI) (Equation (1)), the whiteness index (WI) (Equation (2)), and the color index (CI) (Equation (3)) were also determined [41].

where: L* represents lightness from 0 (black) to 100 (white); a* represents redness from +(red) to −(green); and b* from +(yellow) to −(blue).

2.6. Solubility Determination

First, 0.1 g of film (P0) was dissolved in 100 mL of solvent medium with pH 4, 5, 7, and 8, prepared with citric acid, NaOH, and ultrapure water, and left to stand for 24 h. Afterwards, the samples were filtered, and the retained samples were dried at 70 °C until a constant weight (Pf) was obtained. The solubility percentage was determined by Equation (4) [42].

2.7. Water Activity

The film samples were placed in a desiccator at 48% RH for 24 h, then transferred to a water activity analyzer (Rotronic, HygroPalm23-AW model, Bassersdorf, Switzerland), previously calibrated.

2.8. β-Carotenes Determination

A sample of 1 g of film was taken and homogenized in a 10 mL mixture of acetone and ethanol (1:1). The mixture was then left to stand for 24 h at 4 °C. It was then filtered and transferred to a flask, where 25 mL of hexane and 12.5 mL of distilled water were added (to remove polar or water-soluble compounds and eliminate interference during reading). The mixture was stirred and left to stand for 30 min. The absorbance of the organic phase was measured at 470 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Genesys 150 model, Waltham, MA, USA), with hexane as the blank. The β-carotene content was calculated from a standard curve [43].

2.9. Acidity Determination

In 100 mL of distilled water, 2 g of the sample was dissolved, and the mixture was homogenized at 500 rpm for 60 min. Two drops of 1% phenolphthalein were then added as an indicator and titrated with 0.1 N NaOH. Acidity is determined as the percentage of malic acid [44].

2.10. Tensile Strength (TS) and Elongation (%E) Tests

The samples were measured using a texturometer (Shimadzu EZ-SX model, Kyoto, Japan) in accordance with the ASTM D882-10 standard [45]. The samples were 50 mm × 10 mm with an average thickness of 0.15 mm at a speed of 1.0 mm/s.

2.11. Water Vapor Permeability (WVP) Analysis

It was performed following the ASTM E-96 method [46]. Test tubes were sealed with film of each formulation and placed in a desiccator containing a saturated NaCl solution, which generated an environment of 80% relative humidity at constant temperature (18 °C). Weighing was performed every 2 h until equilibrium was reached.

2.12. Functional Group Analysis by FTIR

The film samples were mixed with KBr (1/100 w/w) (IR grade, Darmstadt, Germany) and pressed into pellets, which were then transferred to the transmission module of an FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet IS50 model, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Readings were taken in the range of 4000 to 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

The experiments were conducted using a simple mixture experimental design with three treatments. The experimental data were collected in triplicate and represented in bar charts and tables, with consideration of the arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation. Likewise, to evaluate the significant difference, a three-factor ANOVA was applied, and the effects of the variables CJ, PS, and P were represented using a Pareto chart. Similarly, a Simplex-Lattice mixture design at the minimum level (m = 1 or three points), given the declared experimental constraints, was used to fit a linear model with an emphasis on individual effects. Its application is methodologically valid when experimental feasibility and evidence suggest linear behavior [47,48]. To evaluate the difference in means between treatments, Tukey’s test was applied at 5% significance. Excel spreadsheets and Statistics V12 were used.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Color and Opacity

The opacity and color of edible films are critical factors influencing their application in food packaging. The CJ color reported L of 36.23, while the chroma a* was 41.80 with a high tendency toward red, and b* was 46.47 with a tendency toward yellow (Table 2). This suggests that the addition of CJ considerably influences the color of the films produced, due to the content of chromophore compounds such as carotenoids (β-carotene: intense orange, α-carotene: yellow-orange, and lutein: greenish yellow) [49,50].

Table 2.

Color and opacity of edible films.

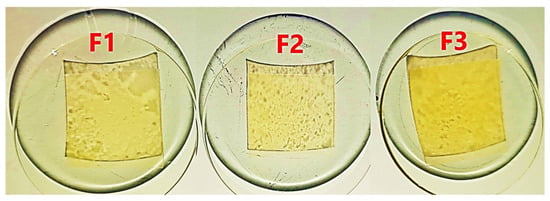

Table 2 shows that the luminance L* trended toward F2 > F1 > F3, with a minimum value of 88.65, suggesting an attractive appearance for food applications [51]. While parameter a* reported red tendencies in the order F3 > F1 > F2, while b* showed yellow tendencies in the order F1 > F3 > F2; these shades are related to the CJ content in the formulations (F3 > F1 > F2). While parameter a* showed tendencies toward red in the order F3 > F1 > F2, and b* displayed tendencies toward yellow in the order F1 > F3 > F2 (Figure 2), these shades are linked to the carotenoid content in the formulations (F3 > F1 > F2) (Figure 2) and how they interact with the chromatic components of cactus mucilage, such as betalains, glycosides, flavonoids, and phenolic acids, which have chromophore properties and range in shades from red to violet [52,53,54,55]. Although F3 (6% CJ) was expected to have higher a* and b* values, b* turned out to be slightly lower than F1 (5% CJ). This is likely due to the red hue that prevails in the films, due to the high stability of β-Carotenes, as opposed to the greater susceptibility of α-Carotenes to oxidation and exposure to ambient light [50,56].

Figure 2.

Edible film images. Source: Authors’ own work.

The Whiteness Index (WI) quantifies color neutrality, with values above 60 being desirable. The Yellowness Index (YI) measures yellowing tendency, with low values (<15) being preferable for neutral applications, although values above 20 indicate a yellowing tendency. The Color Index (CI) represents total saturation, indicating the color intensity of the material. Values below 5 correspond to relatively colorless materials [57,58].

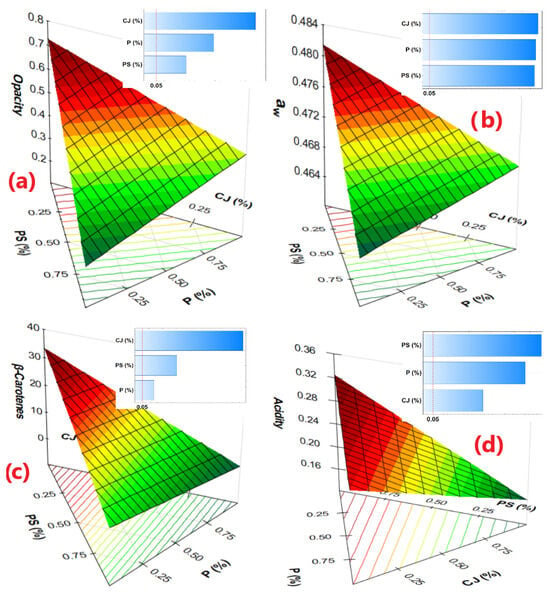

Experimental results on the formulations showed values ranging from 39.72 to 56.76 for WI and from 18.02 to 26.38 for YI, while CI ranged from 4.11 to 6.55. These variations were significantly influenced by the CJ and PS content in the colorimetric properties (Figure 2). The tendency towards yellowing increases considerably from F2 (18.02 with 4% CJ) to F1 (26.38 with 5% CJ), with F3 slightly similar to F1; this is reflected in the behavior of IC, while the whiteness decreases. PS contributed to transparency and chromatic neutrality, significantly improving transparency, being more influenced by P, while the increase in CJ significantly decreases it. This was observed when measuring the opacity, which was greater for F3 (0.56 ± 0.01 abs/mm) (Table 2), due to its higher CJ content, as evidenced in the image in Figure 2. On the other hand, the addition of PS and P shows a significant effect (p-value < 0.05), which allows a considerable decrease in the opacity of the films produced, while, for any increase in CJ, the opacity increases considerably (Figure 3a). It can be inferred that for an approximation to 0% CJ, a very low opacity of less than 0.3 abs/mm is observed (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Effects and response surface of (a) Opacity, (b) Water activity, (c) β-Carotenes, (d) Acidity of edible films.

After the film forms, the starch can reorganize and become more heterogeneous due to the presence of other components (CJ, P, NM), forming crystalline domains and irregular microstructures that scatter light, which would cause an increase in opacity [59]. This phenomenon was observed in edible films made from cassava starch, corn, and plantain [19,59,60]. Therefore, to reduce opacity, pectin or fillers such as modified cellulose are added to minimize light diffraction through the film [61,62].

This is evident in the F1 formulation, which contains less PS. While cactus mucilage acted as a stabilizer for the polymer matrix (although its content was minimal in the films), these compositional variations enable the design of films with specific optical properties tailored to particular applications [42,43,44].

The combination of these natural ingredients, along with modifying the transparency, provides the film with medium color indices with saturation towards orange, typical of carotenoids, in addition to improving its barrier properties, effectively aiding in the conservation and protection of fruits and vegetables during storage [42,43,44,45]. Additionally, the pectin treatment enhances the organoleptic qualities of the juice, increasing its clarity, flavor, and color [46].

3.2. Solubility and Water Activity

The solubility ranges from 93.19% to 99.32%, increasing significantly at alkaline pH (Table 3). This is because PS, CJ, and P polysaccharides, when incorporated into the polymer matrix of the film, ionize in the aqueous medium, exposing their carbonyl, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups. These groups form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl ions in the alkaline medium [39,63,64,65]. Similarly, it was observed that the formulation with higher pectin content (F1) showed higher solubility, while F3 had lower values. The high values are because the individual components of the film exhibit medium to high solubility in aqueous media; this hydrophilic behavior is typical for films made with plant-based polymers [66], and glycerol [67,68], which results in the formulated films lacking high stability as packaging material for food with high humidity [9,34].

Table 3.

Solubility and water activity in edible films.

The aw values found guarantee the absence of proliferation of molds and yeasts, which would allow producing films with high microbiological stability [69]. This would be attributed to the presence of the plasticizer glycerol and NM [39,70] Although the addition of CJ and PS considerably increases the aw values (Figure 3b), due to the polar groups that they present, as well as the formation of a semi-crystalline network with the capacity to retain water, contributing to the aw, as reported by Pei et al., Choque-Quispe et al., and Arias et al. [39,71,72], this would be due to the presence of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups in the surface monolayer of the film [64]. Thus, the obtained films could be recommended for use in materials or foods with low humidity, due to the hydrophilic ability of the film components. Although levels lower than 4% CJ or even up to 0% could produce films with aw lower than 0.4 (extrapolated from Figure 3b), as was observed in films made with starch and glycerin [70,72]

3.3. Total β-Carotenes and Acidity of Edible Films

Considerable variation of β-Carotenes was observed in the elaborated films between 9.12 to 26.11 µg/100 g, reporting higher F3 content (Table 3) due to the higher CJ content in their formulation (Table 1), suggesting that the addition of CJ influences the visual properties of the films, and a synergistic effect is achieved with the addition of PS, as evidenced in the response surface in Figure 3c. In this context, color intensity can serve as an indirect measure of β-carotene content, enabling the assessment of the functional and chromatic properties of films without the need for destructive analysis [73,74]. In addition, the use of CJ not only provides color but also bioactive compounds with antioxidant properties [75,76].

However, β-carotene shows sensitivity in acidic media, which compromises its stability, antioxidant function, and chemical structure [77,78,79].

On the other hand, the incorporation of pectin contributes to the formation of the film matrix and improves the stability of β-carotene by acting as a partial encapsulating agent, reducing its exposure to acidic environments [70,80,81,82]. Additionally, numerous studies have observed that glycerin acts as a plasticizer, enhances the flexibility and moisture retention of the film, thereby protecting β-carotene against oxidation and thermal decomposition during the casting process [63,64,65]. Furthermore, it improves the stability of β-carotene during storage [83,84].

Meanwhile, the mucilage (NM) provides gelling and water retention capacity due to its polysaccharide content, functioning as a dispersing agent [85,86]. This property facilitates the homogeneous incorporation of CJ, ensuring consistency in the color and distribution of carotenoids throughout the matrix, which is essential to achieve films with stable characteristics.

It has been observed that incorporating β-Carotene adds bioactive function (antioxidant and provitamin A) and enables the creation of active or “smart” packaging to extend shelf life and provide nutritional value. Furthermore, some systems can indicate changes through color. Although the effect is greatest when the carotene is encapsulated in the film or coating [87,88,89]

On the other hand, the acidity content in the films decreases considerably with the addition of CJ and P, while the addition of PS increases it (Figure 3d). This is due to the contribution of organic acids from carrot extract, cactus mucilage, and pectin. Values between 0.22 to 0.31% (Table 3) have been reported for the films produced. Acidity is a determining factor in the physical, chemical, and functional properties of edible films; high values degrade β-Carotenes [90], decreasing from 26.11 (F3) to 9.12 (F2) µg/100 g (Table 3). That is, higher acidity favors rapid isomerization and oxidation, with the consequent degradation of β-Carotenes, thus decreasing their content in the film [6,91].

Thus, higher acidity can promote cross-linking, that is, promote the formation of cross-links (reticles) with the polymer chains that form the film; its presence promotes the molecular cross-linking of the polymeric matrix. This generates a more structured and resistant network, providing useful properties such as greater mechanical strength (less brittle, stronger), a better barrier against moisture and oxygen, better adhesion to food, and a possible controlled release of Carotenoids, which would allow for a significant improvement of its functional characteristics [92,93]. For water activity, increased acidity reduces moisture absorption and strengthens barrier properties, which would improve the shelf life of the product [94]. Regarding chromatic stability, acid-biased films favor the preservation of β-Carotenes, tensile strength, elasticity, and texture [93]. Although values above 0.5% can generate undesirable acidic flavors and compromise the sensory qualities of the coated food, the optimum acidity is decisive for the good functionality of the edible film [94].

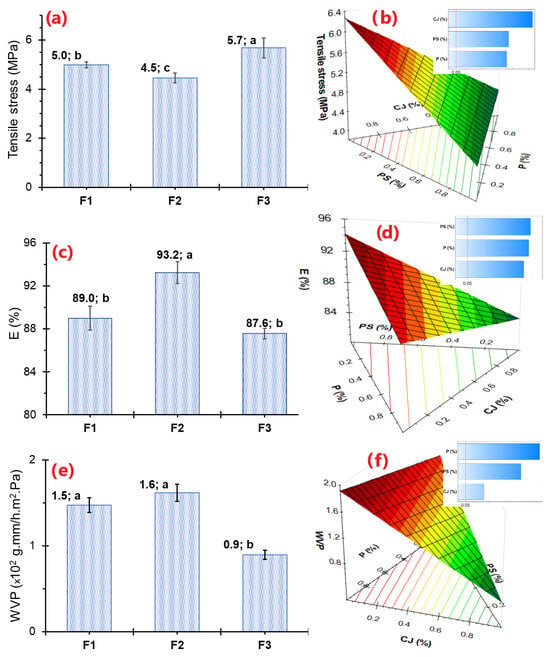

3.4. Mechanical Properties

Edible films are used as packaging, containers, or coating material, and their maneuverability depends on the resistance they offer, which is evaluated through tensile strength. It was observed that F3 reported higher tensile strength (5.7 MPa) while F2 reported lower (4.5 MPa), suggesting that F2 reported lower tensile strength (Figure 4a) and, as a result, higher flexibility. Meanwhile, for elongation (E), which is the maximum stretch point before the films break, a behavior opposite to that of tensile stress was observed; that is, high PS and medium P levels allow films with greater stretch to be formed, that is, the decrease in CJ or even films without CJ would report higher E, as observed in the RSM curve in Figure 4c. These values, found between 87.6 and 93.2% elongation (Figure 4c), are suitable for use in food coatings [95,96,97]. This reduction would be mainly influenced by the lower CJ content (Figure 4b,d), resulting in fewer molecular interactions with the sugars and proteins of starch and pectin. The addition of β-carotene generally decreases tensile strength because its hydrophobic domains disrupt starch hydrogen bonds, although encapsulated carotenoids or carotenoid-containing particles can increase elongation and modify brittleness depending on loading and dispersion [37,87].

Figure 4.

(a) Films’ tensile strength values, (b) Response surface and Pareto effects for film tensile strength, (c) Films’ elongation values, (d) Response surface and Pareto effects for film elongation, (e) Films’ water vapor permeability values, (f) Response surface and Pareto effects for film Water Vapor Permeability.

The values found are much lower than those reported for other films made with potato starch because these films use different plasticizers, such as sorbitol, and incorporate other materials like proteins (gelatin, casein, and whey), polysaccharides (chitosan, agar-agar, carrageenan, and modified celluloses), lipids, and bioactive compounds (chitosan, agar-agar, carrageenan, and modified celluloses) [38,39,98,99]. Although the values found in this research suggest that the films have good mechanical properties, they are able to adapt to surfaces if they are used as coatings adequately.

Although the effect of glycerin was not considered in this study, it would be a determining factor in tensile strength. This compound reduces intermolecular interactions between polymers, decreasing structural cohesion and promoting flexibility at the expense of mechanical strength. On the other hand, nopal mucilage, which is amorphous and hydrophilic in nature, provides limited structural rigidity, while starch limits the formation of structural rigidity [93,100,101,102]. Thus, the components of the films produced do not guarantee a strongly cross-linked matrix, which translates into a lower capacity to withstand tensile stress.

3.5. Water Vapor Permeability (WVP)

Low water vapor permeability values are desirable, as this means less water transfer or moisture loss when used as a packaging material. They also guarantee the preservation of texture in coated foods. However, the negative side lies in the breathability of the coated material or food, which can cause problems such as condensation and deterioration of certain food products [103,104].

The reported values for the elaborated polymers ranged from 0.9 × 10−2 to 1.6 × 10−2 g·mm/h·m2·Pa (Figure 4e), showing a significant effect of PS, CJ, and P. However, the addition of CJ allows for a considerable decrease in permeability, which suggests that a film made without CJ could be more permeable (Figure 4f). This is likely due to the contribution of sugars, which tend to crystallize and lodge in the molecular interstices and pores of the film, thereby decreasing hygroscopicity. In fact, a considerable decrease in permeability has been observed with the addition of β-Carotenes, although this depends on the form of addition and the form of dispersion in the polymeric matrix [37,105].

While the addition of PS may facilitate hydrogen bond formation between the starch hydroxyl groups and water [73], it does not promote mold and yeast growth because of the low aw values it presents (Table 3). Nevertheless, the values found are relatively higher than those of films made with other materials such as modified starches, mucilages, oils, and chitosan, which report values in the order of 10−9 to 10−2 g·mm/h·m2·Pa [74,75,76,77]. However, the films could still be effectively used as packaging for foods or materials with low humidity.

Likewise, an inverse trend has been observed between WPA and tensile strength (see Figure 4a,c,e). This suggests that films with higher tensile strength have denser, more tightly intertwined matrices with greater hydrophobicity, which minimizes pathways for water vapor diffusion. This behavior has been reported for films primarily made from starch, glycerin, proteins, and gelatin [95,96,97,106,107].

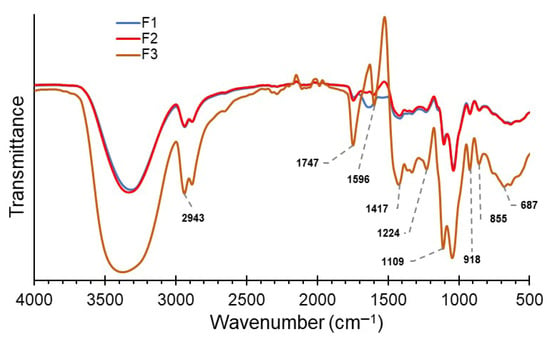

3.6. FTIR Analysis

Figure 5 shows the FTIR spectrum of the edible films, showing the significant presence of hydroxyl groups in the band around 3400 cm−1, coming from the starches, sugars, and water of CJ, PS, P, and MN, being more intense for F3. Similarly, a considerable increase in the F3 C-H aliphatic stretching vibrations is observed near 2943 cm−1, due to the polysaccharides in the film components. The spectrum around 1747 cm−1 is attributed to the carbonyl groups of the P esters and Carotenes of CJ. Furthermore, C–O–C and C–O vibrations are observed between 1417 and 1109 cm−1, primarily in starch and pectin. In the 1500 to 500 cm−1 range (fingerprint), the interaction of the functional groups of PS, P, and NM is mainly observed, which is magnified by the presence of CJ (F3), since carotenoids allow molecular integration. Thus, enabling better structural cohesion of the edible film [16,73].

Figure 5.

FTIR spectrum for edible films.

In general, the addition of CJ significantly increases the peak intensities in the spectra, which are associated with the carbonyl bonds of the carotenoids. Other studies have observed that the addition of CJ improves the structural stability of the resulting films. Furthermore, the increased intensity of most F3 peaks would indicate molecular interactions between the hydroxyl groups of CJ and the polysaccharides of the other components; this would allow for an improvement in the film’s textural properties [25,65,73]

Overall, a panoramic view of the films made with PS, CJ, P, G, and MN demonstrates how the interaction between natural polymers and bioactive compounds can modulate functional properties critical for food packaging applications. The incorporation of CJ significantly influenced color and opacity, as carotenoids such as β-carotene, α-carotene, and lutein contributed characteristic orange-yellow hues. In contrast, their interaction with NM chromophore molecules contributed red-violet hues. These effects were reflected in the color parameters, yellowness index (YI), whiteness index (WI), and color index (CI), which showed that higher CJ contents increased color saturation but reduced transparency, an effect partially counteracted by PS and P. In terms of solubility, values above 95% confirmed the hydrophilic nature of the films, particularly favored in alkaline pH, where the polysaccharides of PS, P, MN, and CJ, due to their functional groups, allow hydrogen bonds to form with the aqueous medium. However, this high solubility limits their application in high-moisture foods, despite the stabilizing role of NM. Water activity (aw) values remained below critical limits for microbial growth (<0.476), ensuring microbiological stability. However, CJ and PS tended to increase it by forming semi-crystalline domains capable of retaining water. Regarding β-carotene content, it increased with the incorporation of CJ, providing both color intensity and antioxidant functionality. Acidity values (0.22–0.31%) influenced polymer crosslinking, strengthening the film matrix and improving its performance as a barrier. Mechanically, the tensile strength (4.5–5.7 MPa) and elongation (87–93%) were influenced by PS and P, whereas CJ reduced the strength due to carotenoid interactions with starch hydrogen bonds. Finally, the water vapor permeability (0.9 × 10−2–1.6 × 10−2 g mm/h m2 Pa) decreased with the addition of CJ due to the crystallization of sugars and the filling of interstitial spaces by carotenoids, improving the barrier properties. Taken together, these results show that the combined action of PS, CJ, P, G, and NM allows the design of edible films with tunable optical, mechanical, and functional properties, reinforcing their potential as active and sustainable materials for food packaging.

4. Conclusions

Edible films are a type of packaging material that helps preserve food or other perishable items in the environment. By using varying doses of potato starch (PS), carrot extract (CJ), and pectin (P), along with fixed amounts of cactus mucilage and glycerin, it has allowed the elaboration of edible films with suitable qualities. In terms of color, shades were observed with L, a*, and b* tending toward red–yellow, while the yellow index and whiteness index were influenced by the addition of CJ, in addition to presenting high transparency. The reported values of water activity around 0.47 and acidity between 0.22 to 0.31% allow stability of the β-Carotenes found between 9.12 and 26.11 µg/100 g, although the films report medium permeability to water vapor and tension at rupture and high elongation. The addition of CJ allows for the improvement of the polymeric matrix of the films, due to the interaction of its functional groups with the other components, evaluated through FTIR. The use of carrot extract and potato starch from the discarded parts of these crops offers an alternative for developing films to be used as packaging material in low-humidity products, although these could be enhanced by incorporating other plasticizers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.-Q. and C.A.L.-S.; methodology, D.C.-Q. and C.A.L.-S.; software, S.D.O. and S.P.-M.; validation, A.M.-Q., L.Q.C. and J.W.E.-S.; formal analysis, S.D.O., F.T.T., S.P.-M., M.C.-F. and L.H.T.-G.; investigation, D.C.-Q., S.D.O., F.T.T., S.P.-M., R.H.A.; L.Q.C. and H.M.C.S.; resources, D.C.-Q.; data curation, S.D.O. and S.P.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.L.-S., S.P.-M. and S.D.O.; writing—review and editing, D.C.-Q., C.A.L.-S., L.H.T.-G., J.W.E.-S. and S.D.O.; visualization, M.C.-F., A.M.-Q. and J.W.E.-S.; supervision, D.C.-Q.; project administration, S.D.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The authors funded the publication costs.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be requested from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Water Treatment Materials Research Laboratory (LIMTA) and the Vice-Rectorate for Research at the José María Arguedas National University, Andahuaylas, Perú. Likewise, to the rheology laboratory at the Universidad Nacional Intercultural de Quillabamba, Peru.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kaur, G.J.; Orsat, V.; Singh, A. Challenges and potential solutions to utilization of carrot rejects and waste in food processing. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2036–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangeli, R.; Cicatiello, C. Lost vegetables, lost value: Assessment of carrot downgrading and losses at a large producer organisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkort, A.J.; Linnemann, A.R.; Struik, P.C.; Wiskerke, J.S.C. On processing potato 3: Survey of performances, productivity and losses in the supply chain. Potato Res. 2023, 66, 385–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.D.; Nawanir, G.; Mahmud, F.; Mohamad, F.; Ahmad, M.H.; AbdulGhani, A. Sustainability of biodegradable plastics: New problem or solution to solve the global plastic pollution? Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 5, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Pirsa, S. Production of biodegradable film based on polylactic acid, modified with lycopene pigment and TiO2 and studying its physicochemical properties. J. Polym. Environ. 2020, 28, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montes, E.; Castro-Muñoz, R. Edible films and coatings as food-quality preservers: An overview. Foods 2021, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Lall, A.; Kumar, S.; Patil, T.D.; Gaikwad, K.K. Plant based edible films and coatings for food packaging applications: Recent advances, applications, and trends. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1428–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.F.; Díaz, O.; Cobos, A.; Pereira, C.D. A review of recent developments in edible films and coatings-focus on whey-based materials. Foods 2024, 13, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Filho, J.G.; Bertolo, M.R.V.; Fernandes, S.S.; Lemes, A.C.; da Cruz Silva, G.; Junior, S.B.; de Azeredo, H.M.C.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Egea, M.B. Intelligent and active biodegradable biopolymeric films containing carotenoids. Food Chem. 2024, 434, 137454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, S.A.; Matar, A.; Ismail, A.M.; Farag, H.A.S. Sodium alginate edible films incorporating cactus pear extract: Antimicrobial, chemical, and mechanical properties. Ital. J. Food Sci. Riv. 2024, 36, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coqueiro, J.M.; Singh, R.K.; Kupski, L.; Fernandes, S.S.; Otero, D.M. Techno-functional properties of Cactaceae polysaccharides for food packaging application: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 312, 144099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.P.; Bangar, S.P.; Yang, T.; Trif, M.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, D. Effect on the properties of edible starch-based films by the incorporation of additives: A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Weiss, A.; Ihl, M.; Sobral, P.J.d.A.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Bifani, V. Natural additives in bioactive edible films and coatings: Functionality and applications in foods. Food Eng. Rev. 2013, 5, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. Preparation and incorporation of functional ingredients in edible films and coatings. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2021, 14, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ma, S.; Wang, Q.; McClements, D.J.; Liu, X.; Ngai, T.; Liu, F. Fortification of edible films with bioactive agents: A review of their formation, properties, and application in food preservation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 5029–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoni, C.G.; Avena-Bustillos, R.J.; Azeredo, H.M.C.; Lorevice, M.V.; Moura, M.R.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; McHugh, T.H. Recent advances on edible films based on fruits and vegetables—A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis, R.Q.; Rios, P.D.A.; de Oliveira Rios, A.; Olivera, F.C. Biodegradable packaging of cellulose acetate incorporated with norbixin, lycopene or zeaxanthin. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 147, 112212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Díaz, A.S.; Méndez-Lagunas, L.L. Mucilage-based films for food applications. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 6677–6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ju, J.; Diao, Y.; Zhao, F.; Yang, Q. The application of starch-based edible film in food preservation: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 2731–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pooja, N.; Ahmed, N.Y.; Mal, S.S.; Bharath, P.A.S.; Zhuo, G.-Y.; Noothalapati, H.; Managuli, V.; Mazumder, N. Assessment of biocompatibility for citric acid crosslinked starch elastomeric films in cell culture applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choque-Quispe, D.; Diaz-Barrera, Y.; Solano-Reynoso, A.M.; Choque-Quispe, Y.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E.; Martínez-Huamán, E.L.; Aguirre Landa, J.P.; Correa-Cuba, O.; et al. Effect of the Application of a Coating Native Potato Starch/Nopal Mucilage/Pectin on Physicochemical and Physiological Properties during Storage of Fuerte and Hass Avocado (Persea americana). Polymers 2022, 14, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xing, Y.; Liu, G.; Bao, D.; Hu, W.; Bi, H.; Wang, M. Extraction, purification, structural features, biological activities, and applications of polysaccharides from Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. (cactus): A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1566000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Palma, R.M.; Martinez-Munoz, P.E.; Contreras-Padilla, M.; Feregrino-Perez, A.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.E. Evaluation of water diffusion, water vapor permeability coefficients, physicochemical and antimicrobial properties of thin films of nopal mucilage, orange essential oil, and orange pectin. J. Food Eng. 2024, 366, 111865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparella, A.; Kongala, P.R.; Serio, A.; Rossi, C.; Shaltiel-Harpaza, L.; Husaini, A.M.; Ibdah, M. Challenges and opportunities in the sustainable improvement of carrot production. Plants 2024, 13, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhoden, T.; Aggarwal, P.; Singh, A.; Kaur, S.; Grover, S. Application of red carrot pomace carotenoids for the development of biofunctional edible film: A sustainable approach. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 15, 27575–27592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syarifuddin, A.; Muflih, M.H.; Izzah, N.; Fadillah, U.; Ainani, A.F.; Dirpan, A. Pectin-based edible films and coatings: From extraction to application on food packaging towards circular economy-A review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 9, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantiniotou, M.; Athanasiadis, V.; Kalompatsios, D.; Lalas, S.I. Optimization of carotenoids and other antioxidant compounds extraction from carrot peels using response surface methodology. Biomass 2024, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikselová, M.; Šilhár, S.; Mareček, J.; Frančáková, H. Extraction of carrot (Daucus carota L.) carotenes under different conditions. Czech J. Food Sci. 2008, 26, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannata, C.; Rutigliano, C.A.C.; Restuccia, C.; Muratore, G.; Sabatino, L.; Geoffriau, E.; Leonardi, C.; Mauro, R.P. Effects of polysaccharide-based edible coatings on the shelf life of fresh-cut carrots with different pigmentations. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 20, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowicz, M.; Galus, S.; Ciurzyńska, A.; Nowacka, M. The potential of edible films, sheets, and coatings based on fruits and vegetables in the context of sustainable food packaging development. Polymers 2023, 15, 4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoor, A.; Yousuf, B.; Pandith, J.A.; Ahmad, S. Plant-derived active substances incorporated as antioxidant, antibacterial or antifungal components in coatings/films for food packaging applications. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidiyanti, J.; Aji, A.S.; Irwanti, W.; Putri, F.R.; Nurjanah, R. Sensory Evaluation And β-Carotene Content Test in The Development of Yellow Pumpkin Brownies Products with The Substitution of Natural Sweeteners from Stevia Leaves (Stevia rabaudiana). J. Glob. Nutr. 2025, 5, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, T.B.R.; Mendonça, C.R.B.; Zambiazi, R.C. Methods of protection and application of carotenoids in foods-a bibliographic review. Food Biosci. 2022, 48, 101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, L.; Rech, R.; Flôres, S.H.; Nachtigall, S.M.B.; de Oliveira Rios, A. Poly (acid lactic) films with carotenoids extracts: Release study and effect on sunflower oil preservation. Food Chem. 2019, 281, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, S.; Nasir, N.T.B.M.; Erken, İ.; Çakmak, Z.E.; Çakmak, T. Antioxidant composite films with chitosan and carotenoid extract from Chlorella vulgaris: Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of carotenoids and surface characterization of chitosan films. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 095404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Mártinez, L.; Pérez-Cervera, C.; Andrade-Pizarro, R. Effect of glycerol and sorbitol concentrations on mechanical, optical, and barrier properties of sweet potato starch film. NFS J. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupuna-Yerovi, D.S.; Schmidt, H.; Rios, A.d.O. Biodegradable sodium alginate films incorporated with lycopene and β-carotene for food packaging purposes. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2025, 31, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choque-Quispe, D.; Choque-Quispe, Y.; Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E.; Solano-Reynoso, A.M.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Taipe-Pardo, F.; Martínez-Huamán, E.L.; Aguirre Landa, J.P.; Agreda Cerna, H.W. Effect of the addition of corn husk cellulose nanocrystals in the development of a novel edible film. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choque-Quispe, D.; Froehner, S.; Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Choque-Quispe, Y.; Solano-Reynoso, A.M.; Taipe-Pardo, F.; Zamalloa-Puma, L.M.; Calla-Florez, M. Preparation and chemical and physical characteristics of an edible film based on native potato starch and nopal mucilage. Polymers 2021, 13, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez-Moreno, M.; Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A.; Barros-Castillo, J.C.; Solís-Pacheco, J.R.; Calderón-Santoyo, M. Characterization of sodium alginate coatings with Meyerozyma caribbica and impact on quality properties of avocado fruit. LWT 2021, 152, 112346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krochta, J.M.; Mulder-Johnston, C.d. Edible and biodegradable polymer films: Challenges and opportunities. Food Technol. 1997, 51, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Turhan, K.N.; Şahbaz, F. Water vapor permeability, tensile properties and solubility of methylcellulose-based edible films. J. Food Eng. 2004, 61, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, L.F.; Villarreal, J.E.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L. The increase in antioxidant capacity after wounding depends on the type of fruit or vegetable tissue. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentería-Ortega, M.; Colín-Alvarez, M.d.L.; Gaona-Sánchez, V.A.; Chalapud, M.C.; García-Hernández, A.B.; León-Espinosa, E.B.; Valdespino-León, M.; Serrano-Villa, F.S.; Calderón-Domínguez, G. Characterization and Applications of the Pectin Extracted from the Peel of Passiflora tripartita var. mollissima. Membranes 2023, 13, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM-D882-10; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- ASTME-96/E-96M-05; Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials. ASTM international: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009.

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Squeo, G.; De Angelis, D.; Leardi, R.; Summo, C.; Caponio, F. Background, applications and issues of the experimental designs for mixture in the food sector. Foods 2021, 10, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska, M.; Markowski, M. Color characteristics of carrots: Effect of drying and rehydration. Int. J. Food Prop. 2012, 15, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.S.; Bang, H.; Pike, L.; Patil, B.S.; Lee, E.J. Comparing carotene, anthocyanins, and terpenoid concentrations in selected carrot lines of different colors. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.; Gaglio, R.; Greco, G.; Gentile, C.; Settanni, L.; Inglese, P. Effect of Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage edible coating on quality, nutraceutical, and sensorial parameters of minimally processed cactus pear fruits. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanarez-Tenorio, L.E.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Cira-Chávez, L.A.; Estrada-Alvarado, M.I.; Márquez-Ríos, E.; Del Toro-Sánchez, C.L.; Suárez-Jiménez, G.M. Physicochemical characterization, antioxidant activity and total phenolic and flavonoid content of purple prickly pear (Opuntia gosseliniana) at two stages of coloration. Biotecnia 2022, 24, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy-Barrera, E. Analysis of betalains (betacyanins and betaxanthins). In Recent Advances in Natural Products Analysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 593–619. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.; Ribeiro, M.H.; Almeida, C.M.M. Physicochemical, nutritional, and medicinal properties of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. and its main agro-industrial use: A review. Plants 2023, 12, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, V.; Okun, Z.; Shpigelman, A. Utilization of hydrocolloids for the stabilization of pigments from natural sources. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 68, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, N.; Burdurlu, H.S.; Karadeniz, F. Kinetics of colour changes in dehydrated carrots. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschler, R. Visual and instrumental evaluation of whiteness and yellowness. In Colour Measurement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 88–124. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, A.K.R. 9—Instrumental measures of whiteness. In Principles of Colour and Appearance Measurement; Choudhury, A.K.R., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 344–374. [Google Scholar]

- Naveen, R.; Loganathan, M. Role of varieties of starch in the development of edible films—A review. Starch-Stärke 2024, 76, 2300138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, T.R.; Adhitasari, A.; Paramita, V.; Yulianto, M.E.; Ariyanto, H.D. Effect of different starch on the characteristics of edible film as functional packaging in fresh meat or meat products: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 87, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Improving the performance of edible food packaging films by using nanocellulose as an additive. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 166, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.R.S.B.; Abid, M.B.; Shamim, A.; Suradi, S.S.; Marsi, N.B.; Kormin, F.B. A review on biodegradable composite films containing organic material as a natural filler. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 2126–2161. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.q.; Li, Y.; Guo, S.x.; Yao, X.; Zheng, Z.x.; Li, F.f.; Wu, M. Effect of pH on the Properties of Potato Flour Film-Forming Dispersions and the Resulting Films. Starch-Stärke 2024, 76, 2300251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Guha, P. Organic acid-compatibilized potato starch/guar gum blend films. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 268, 124714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, P.; Lata, K.; Kaur, T.; Jambrak, A.R.; Sharma, S.; Roy, S.; Sinhmar, A.; Thory, R.; Singh, G.P.; Aayush, K. Recent advances in the preservation of postharvest fruits using edible films and coatings: A comprehensive review. Food Chem. 2023, 418, 135916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W.; Shi, W.; Gong, D.; Zhang, G. Improvement of solubility, emulsification property and stability of potato protein by pH-shifting combined with microwave treatment and interaction with pectin. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duan, Q.; Yue, S.; Alee, M.; Liu, H. Enhancing mechanical and water barrier properties of starch film using chia mucilage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosif, M.M.; Najda, A.; Bains, A.; Zawiślak, G.; Maj, G.; Chawla, P. Starch–mucilage composite films: An inclusive on physicochemical and biological perspective. Polymers 2021, 13, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, L.; Pauliuc, D.; Oroian, M. Honey microbiota, methods for determining the microbiological composition and the antimicrobial effect of honey–A review. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayquipa-Cuellar, E.; Salcedo-Sucasaca, L.; Azamar-Barrios, J.A.; Chaquilla-Quilca, G. Assessment of prickly pear peel mucilage and potato husk starch for edible films production for food packaging industries. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Palanisamy, C.P.; Srinivasan, G.P.; Panagal, M.; Kumar, S.S.D.; Mironescu, M. A comprehensive review on starch-based sustainable edible films loaded with bioactive components for food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, L.V.A.; Silva, V.d.S.; Vieira, J.M.M.; Fakhouri, F.M.; de Oliveira, R.A. Plant-based films for food packaging as a plastic waste management alternative: Potato and cassava starch case. Polymers 2024, 16, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhoden, T.; Singh, A.; Aggarwal, P.; Kaur, S. Enhancing the functionality of corn starch-based edible films through carotenoid emulsions prepared from yellow carrot pomace: Implications on structural, morphological and thermal properties. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 6049–6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, C.R.; Paccola, C.S.; Al-Ghamdi, S.; Rasco, B.; Tang, J.; Sablani, S.S. Stability of color, β-carotene, and ascorbic acid in thermally pasteurized carrot puree to the storage temperature and gas barrier properties of selected packaging films. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Siddiqui, S.; Gehlot, R. Physicochemical and bioactive compounds in carrot and beetroot juice. Asian J. Dairy Food Res. 2019, 38, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Abrol, G.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, K.D. Carrot and Carrot Products: A Superb Functional Food. In Functional Compounds and Foods of Plant Origin; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 269–290. [Google Scholar]

- Stutz, H.; Bresgen, N.; Eckl, P.M. Analytical tools for the analysis of β-carotene and its degradation products. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 650–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-Y.; Lai, Y.-R.; How, S.-C.; Lin, T.-H.; Wang, S.S.S. Encapsulation with a complex of acidic/alkaline polysaccharide-whey protein isolate fibril bilayer microcapsules enhances the stability of β-carotene under acidic environments. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 160, 105344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Ribeiro, C.D.; Otero, D.M.; Larroza, I. Encapsulation: Strategy for β-carotene Preservation. Nutr. Food Sci. Int. J. 2019, 9, 555751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Chen, T.; Huang, M.; Ren, G.; Lei, Q.; Fang, W.; Xie, H. Exploration of the microstructure and rheological properties of sodium alginate-pectin-whey protein isolate stabilized Β-carotene emulsions: To improve stability and achieve gastrointestinal sustained release. Foods 2021, 10, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singaram, A.J.V.; Guruchandran, S.; Ganesan, N.D. Review on functionalized pectin films for active food packaging. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2024, 37, 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixé-Roig, J.; Oms-Oliu, G.; Ballesté-Muñoz, S.; Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Martín-Belloso, O. Improving the in vitro bioaccessibility of β-carotene using pectin added nanoemulsions. Foods 2020, 9, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Tian, C.; Luo, J.; Sun, X.; Quan, M.; Zheng, C.; Zhan, J. Influence of technical processing units on the α-carotene, β-carotene and lutein contents of carrot (Daucus carrot L.) juice. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 16, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hao, H.; Thuy, N.M.; Giau, T.N.; Van Tai, N.; Minh, V.Q. Effect of foaming agent and drying temperature on drying rate and quality of foam-mat dried papaya powder. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2024, 13, e10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Barradas, O.; Esteban-Cortina, A.; Mendoza-Lopez, M.R.; Ortiz-Basurto, R.I.; Díaz-Ramos, D.I.; Jiménez-Fernández, M. Chemical modification of Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage: Characterization, physicochemical, and functional properties. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 8783–8798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.; Badalamenti, S.; Lombardo, A.; Forte, A. Use of prickly pear (nopal) mucilage in construction applications: Research and results. Life Saf. Secur. 2024, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Assis, R.Q.; Pagno, C.H.; Costa, T.M.H.; Flôres, S.H.; Rios, A.d.O. Synthesis of biodegradable films based on cassava starch containing free and nanoencapsulated β-carotene. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2018, 31, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago-Vanzela, E.S.a.a.; Do Nascimento, P.; Fontes, E.A.F.; Mauro, M.A.; Kimura, M. Edible coatings from native and modified starches retain carotenoids in pumpkin during drying. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Priyadarshi, R.; Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Biswas, D.; Chandel, V.; Rhim, J.-W. Recent progress in pectin extraction, characterization, and pectin-based films for active food packaging applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T.; Alamzad, R.; Graf, B.A. Effect of pH on the chemical stability of carotenoids in juice. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, E94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Deshmukh, R.K.; Tripathi, S.; Gaikwad, K.K.; Das, S.S.; Sharma, D. Recent advances in the carotenoids added to food packaging films: A review. Foods 2023, 12, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, Y.; Maitland, E.; Pascall, M.A. The effect of citric acid concentrations on the mechanical, thermal, and structural properties of starch edible films. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 1801–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, V.P.B.; de Oliveira, K.Á.R.; Queiroga, T.S.; de Souza, E.L. Development and Application of Mucilage and Bioactive Compounds from Cactaceae to Formulate Novel and Sustainable Edible Films and Coatings to Preserve Fruits and Vegetables—A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Saha, M.; Gupta, M.K.; Rangan, L.; Uppaluri, R.; Das, C. Comparative efficacy of citric acid/tartaric acid/malic acid additive-based polyvinyl alcohol-starch composite films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2024, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongjareonrak, A.; Benjakul, S.; Visessanguan, W.; Tanaka, M. Effects of plasticizers on the properties of edible films from skin gelatin of bigeye snapper and brownstripe red snapper. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 222, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongjareonrak, A.; Benjakul, S.; Visessanguan, W.; Prodpran, T.; Tanaka, M. Characterization of edible films from skin gelatin of brownstripe red snapper and bigeye snapper. Food Hydrocoll. 2006, 20, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökkaya Erdem, B.; Dıblan, S.; Kaya, S. A comprehensive study on sorption, water barrier, and physicochemical properties of some protein-and carbohydrate-based edible films. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 2161–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; Liu, D.; Qin, J.; Yang, M. Functional pH-sensitive film containing purple sweet potato anthocyanins for pork freshness monitoring and cherry preservation. Foods 2024, 13, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartika, M.; Rambe, F.R.; Parinduri, S.; Harahap, H.; Nasution, H.; Lubis, M.; Manurung, R. Tensile properties of edible films from various types of starch with the addition of glycerol as plasticizer: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1115, 012075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, R.; Ahmed, J.; Thakur, R.; Sarkar, P. Starch-based edible packaging: Rheological, thermal, mechanical, microstructural, and barrier properties—A review. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Martinez, B.M.; Martínez-Flores, H.E.; Berrios, J.D.J.; Otoni, C.G.; Wood, D.F.; Velazquez, G. Physical characterization of biodegradable films based on chitosan, polyvinyl alcohol and Opuntia mucilage. J. Polym. Environ. 2017, 25, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.L.; Motsa, N.; Abdillah, A.A. A comprehensive characterization of biodegradable edible films based on potato peel starch plasticized with glycerol. Polymers 2022, 14, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, M.; Ruan, C.-Q. The reduce of water vapor permeability of polysaccharide-based films in food packaging: A comprehensive review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 321, 121267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Morales-Sanchez, E.; Velazquez, G.; Vázquez, M. Measurement of the water vapor permeability of chitosan films: A laboratory experiment on food packaging materials. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 2403–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, M.J.; López-Rubio, A.; Sentandreu, E.; Lagaron, J.M. Development of multilayer corn starch-based food packaging structures containing β-carotene by means of the electro-hydrodynamic processing. Starch-Stärke 2016, 68, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitoyannis, I.; Nakayama, A.; Aiba, S.-I. Edible films made from hydroxypropyl starch and gelatin and plasticized by polyols and water. Carbohydr. Polym. 1998, 36, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hassan, A.A.; Norziah, M.H. Starch–gelatin edible films: Water vapor permeability and mechanical properties as affected by plasticizers. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 26, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.