Abstract

This paper presents an innovative concept for the musealization of everyday public space through the use of natural stone cladding as an in situ palaeontological exhibition. Polished slabs of Holy Cross Mts marble, widely used as flooring in public buildings, contain abundant and well-preserved Devonian marine fossils, offering a unique opportunity to revitalize public engagement with palaeontology and geoheritage. The proposed exhibition transforms passers-by into active observers by integrating authentic fossil material directly into daily circulation routes, thereby emphasizing the educational and geotouristic potential of ordinary architectural elements. The case study focuses on the main hall of the University of the National Education Commission (Kraków, Poland), where over 1000 m2 of fossil-bearing limestone flooring is used as a continuous exhibition surface. The target audience includes students of Earth sciences, zoology, biological sciences, pedagogy, social sciences, and humanities, for whom the exhibition serves as both an educational supplement and a geotouristic experience. The scientific, educational, and touristic value of the proposed exhibition was assessed using a modified geoheritage valorization method and compared with established palaeontological collections in Kraków and Kielce. The expert valuation method used in the article enables a comparison of the described collection with other similar places on Earth, making its application universal and global. The results demonstrate that polished stone cladding can function as a valuable geoheritage asset of regional and global significance, offering an accessible, low-cost, and sustainable model for disseminating palaeontological knowledge within public space.

1. Introduction

Contemporary technological development has profoundly reshaped public engagement with Earth sciences, including palaeontology. While digital reconstructions and virtual environments have gained popularity, they often overshadow direct contact with authentic geological and palaeontological material [1]. As a result, museum exhibitions based on real specimens are increasingly undervalued, despite their fundamental role in scientific education and public understanding of Earth history (e.g., [2]).

Direct observation of real rock material, including polished stone sections used in architectural contexts, represents an underexplored yet highly effective educational resource. Such natural surfaces expose fossils in situ, preserving their spatial relationships, taphonomic features, and palaeoenvironmental context—attributes rarely conveyed by isolated museum specimens.

Public perception of palaeontology has long been dominated by media portrayals of dinosaurs, often emphasizing spectacle over scientific accuracy (e.g., [3,4]. Although these representations have popularized the field, they have also contributed to a narrow and distorted understanding of palaeontology as a discipline.

In the public sphaere, the importance of palaeontology should be restored as a science on the border of biological and geological sciences, which touches on the issues of the existence of life and its duration, as well as the future of life. The history of palaeontology is the history of the development of human consciousness and reaching for the limits of knowledge of the origin of the human being, as well as reaching with thought to the beginning of the existence of all life on planet Earth. The development of the fields of palaeontology, in the modern scientific sense, is inextricably linked to finding and collecting the remains of ancient creatures, which became fossils over millions or even billions of years after being buried in sediments and subjected to various taphonomic processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selected examples of fossils from different geological periods and in varying degrees of preservation. (A). Microfossils with preserved organic walls found in Cambrian clastic formations in the Świętokrzyskie Mountains in Poland (for a detailed description see [5]). (B). Pyritized skeleton of a Cretaceous radiolarian (Novixitus mclaughlini Pessagno) from anoxic deposits of the Pieniny Klippen Belt in Poland (details can be found in [6,7]).

This paper argues that restoring the visibility of palaeontology requires reintroducing real fossil material into everyday experience, beyond traditional museum spaces. The aim of this study is to propose and evaluate a new model of palaeontological exhibition embedded in public space, where fossil-bearing stone cladding transforms passers-by into viewers and contributes to the revitalization of disappearing knowledge about extinct species. This approach emphasizes geoheritage, geotourism, and experiential learning, positioning palaeontology at the intersection of geological, biological, and social sciences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Research Material

In this publication, we analyze the stone floor slabs made of Devonian limestone, covering over 1000 square meters, located in the main hall of the University of the Commission of National Education building in Kraków. They constitute a collection of palaeontological objects forming an exhibition of cognitive, educational, and scientific value. These fossiliferous limestone (marble) cladding, containing a large number of macroremains of shallow-marine invertebrates allows for palaeoecological and biostratonomic studies. We propose an educational exhibition based on fossils found directly in the cladding slabs. We also test the level of interest of passers-by if they could view the exhibitions during their daily walk through the university’s corridors.

The origin of the research material is related to the construction period of the main building of the current University of the Commission of National Education, Krakow (UKEN), which took place from 1966 to 1973. During this time, rock material was collected from known quarries in the Kielce area (the Holy Cross Mountains; 100 km north-east of Kraków), and the floor was laid. In the case of the marbles, the name “marbles” for the rocks in question has a technical and commercial meaning and, in this context, is related to their excellent polishing properties. Petrographically, these are compact and massive organogenic limestones, partially recrystallized, originating from the Palaeozoic core of the Holy Cross Mountains. Based on fossils, the age was determined as the Middle and Upper Devonian (e.g., [8]).

2.2. Museum Collections for Comparison

To characterize the cognitive and educational value of the proposed palaeontological collection using cross-sections in the floor cladding slabs at the main building of the UKEN, three exhibitions were selected, showcasing palaeontological objects available in the city of Kraków, in public educational buildings as follows: (1) Building A0 of the AGH University of Krakow (AGH), (2) the Nature Education Centre of the Jagiellonian University (UJ) in Kraków, and (3) the Geological Museum located in the building of the Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences (ING PAN) also in Kraków. Additionally, a collection from the Geonatura Kielce (Geoeducation Center—(GC)), home to the Holy Cross Mts marble stratotype area, was selected for comparison.

2.3. Comparative Framework and Assessment Methods

To compare palaeontological collections located in research facilities in Krakow and Kielce, we employed the point valuation methodology, a common approach in assessing unique inanimate objects. Valuation methods fall within the point valuation framework, where individual criteria are assigned specific point values. The methods discussed in the literature mainly concern the valorisation of inanimate natural objects situated in their original locations [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Some valuation methods are also applicable to mining facilities [21]. For this valuation, the method outlined by Brilha [22] was chosen and adapted to evaluate facilities located within buildings (ex situ) (Supplementary Materials: Table S1).

The proposed valorization consists of two components: (1) Scientific and Cognitive Value and (2) Potential Educational and Touristic Uses.

The scientific and cognitive value of the collection was assessed using seven criteria: representativeness, key locality, scientific knowledge, integrity, geological diversity, rarity, use limitations, didactic potential, and diversity. Each feature was scored on a scale of 1 to 4, as defined in (Supplementary Materials: Table S1). If a given criterion was absent, experts assigned 0 points. The maximum value of this component for the assessed geosite was 28.

The potential educational and touristic uses of the collection were assessed based on eleven criteria: didactic potential, diversity, vulnerability, accessibility, use limitations, safety, uniqueness, observation conditions, deterioration of geological/palaeontological elements, legal protection, and interpretative potential. Each criterion was assigned a score from 1 to 4 (Supplementary Materials: Table S1). If a given criterion was absent, experts awarded 0 points. The maximum score for this component for the assessed geosite was 44. Then, the sums of the values for each criterion were divided by the maximum possible sum for each component, so that all values fell between 0 and 1. Based on this, four groups were identified (Table 1). The boundaries between them were adopted from J. Warszyńska [23].

Table 1.

Geosite groups separated based on the valorization results [24].

The final valorization index (Total Geoheritage Value) was calculated based on a weighted average, with the Scientific and Cognitive Value component receiving a weight of 0.7 and the Potential Educational and Touristic Uses component receiving a weight of 0.3. The weight values emphasize the importance of scientific and cognitive values over potential educational and touristic values, which can be more easily increased by implementing activities related to sharing and promotion [25].

Therefore, the formula for calculating TGV is as follows:

where SCU—Scientific and Cognitive Value, PETU—Potential Educational and Touristic Uses.

TGV = 0.7SCV + 0.3PETU

2.4. Characteristics of the Experts Evaluating the Selected Collections

To objectify the valorization results, the triangulation method was employed [26], involving the selection of four experts to evaluate the aforementioned collections containing palaeontological elements. All are academic teachers in the field of Earth sciences and published scientists in their respective fields. They are also competent in guiding tours, presenting objects of inanimate nature.

Expert 1 is a geologist and sedimentologist specializing primarily in clastic sedimentary rocks. Expert 2 is a specialist in geotourism. Expert 3 is a geologist with experience in geotourism. Expert 4 is a geologist and paleontologist with experience in taphonomy, micropalaeontology, and stratigraphy.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Proposed Palaeontological Exhibition at UKEN

The cladding panels located in the main building of the UKEN contain numerous palaeontological elements that together form a unique, continuous in situ exhibition. The exhibition is distributed across the ground floor and the first-floor hall of the main building (Podchorążych St. 2) and covers a total area of almost 1000 m2 (ground floor—513 m2; first-floor hall—432 m2). The floor is composed of irregular, polished slabs with maximum diagonals reaching several tens of centimeters (Figure 2). On a national scale, this floor represents an exceptional palaeontological resource due to the abundance, diversity, and visibility of fossil remains preserved directly within the architectural fabric of a public educational building. Unlike traditional museum collections, the fossils are not selected or isolated; instead, they occur naturally, forming extensive fossil assemblages that are observable during everyday movement through the building.

Figure 2.

Natural stone flooring composed of irregularly arranged slabs (Holy Cross Mts marble). (A) Dominant gray limestone with numerous cross-sections of fossil bivalve shells and fossil stromatoporoid structures (Jaźwica or Bolechowice quarry). (B) Slabs of various shades, predominantly brown to cherry-coloured, with numerous stromatoporoids (Bolechowice quarry). Photos are taken by authors.

The Holy Cross Mts marble used for the cladding originates from several quarries in the Kielce region and represent Middle Devonian carbonate platform deposits, dating back at least 390 million years [27,28,29,30]. These rocks were deposited in a warm shallow-marine environment, analogous to modern carbonate platforms such as the Bahamas (e.g., [31,32]. Lagoonal and reef-associated facies dominate, indicating stable tropical conditions conducive to the development of reef-building organisms [29].

Numerous macrofossils visible in the slabs testify to the high biodiversity of Devonian shallow seas. The most common fossils include stromatoporoids (Stromatopora sp. and Amphipora sp.; Figure 3 and Figure 4) and bivalves (Megalodon sp.; Figure 5); corals (Tetracorallia) and gastropods (Loxonema) occur subordinately. Fossils occur both in life position and as disarticulated or fragmented remains, often showing evidence of post-mortem transport, mechanical breakage, and redeposition. This allows direct observation of biostratonomic and taphonomic processes, which are rarely accessible to non-specialists.

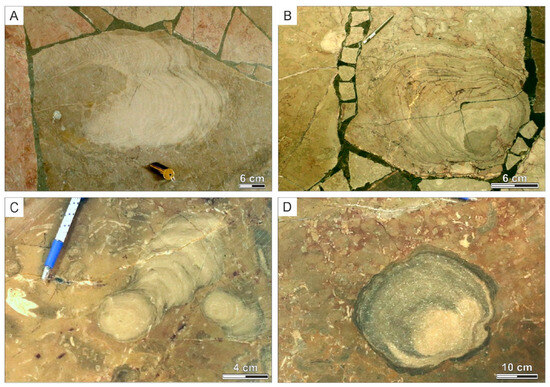

Figure 3.

Fossils of Stromatopora sp., an extinct group, in limestone from the Bolechowice quarry (Holy Cross Mountains). (A) Cross-section showing the internal structure composed of thin layers growing upward (coffee point on the first floor, near the pillar). (B) Longitudinal section of a specimen with the boundaries of layer growth highlighted by red incrustations of microcrystalline iron oxides (ground floor, near the gatehouse). (C,D) Oval, bulbous specimens with a spherical structure composed of concentric layers (ground floor, near the lift). Photos are taken by authors.

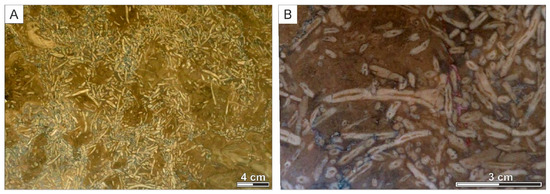

Figure 4.

Fossils of Amphipora sp., an extinct group, in limestone from the Bolechowice quarry. (A) Numerous white twig-like forms forming the so-called “spaghetti-like” or “vermicelli-like” rock (first floor, near the dining hall). (B) Details of the structure of individual specimens (a single twig) with dark axial channel (first floor, near the dining hall). Photos are taken by authors.

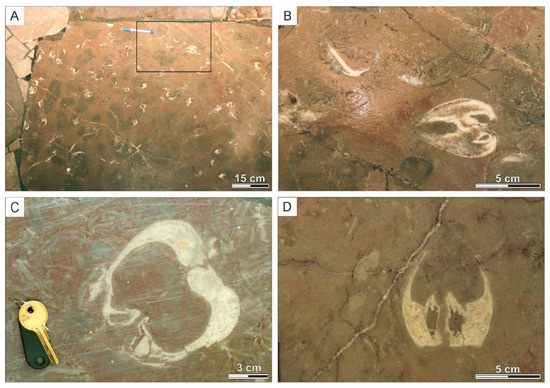

Figure 5.

Bivalve fossils in cherry-red limestone from the Jaźwica or Bolechowice quarries. (A) Limestone slab with numerous cross-sections of well-preserved Megalodon sp. shells (bright spots in the floor of the ground-floor corridor near the porter’s lodge). (B) Enlargement of the selected area in figure (A); Cross-section through articulated bivalve shells of the genus Megalodon, with a visible hinge connecting the two valves. (C) Cross-section of thick-shelled bivalve with a visible hinge structure. (D) Another cross-section of articulated shells (C,D—slabs on the ground floor, near the lift). Photos are taken by authors.

Additionally, trace fossils preserved as feeding and bioturbation structures occur in several slabs, providing insight into organism–substrate interactions and benthic activity within soft marine sediments (see also: [27,28,29,33,34].

3.2. Musealization of Passers-By and Exhibition Design Concept

The fundamental element of the proposed exhibition is the musealization of passers-by, achieved by embedding palaeontological content directly into everyday circulation routes within the university building. The exhibition does not require an intentional visit or prior interest in Earth sciences. Instead, it operates through repeated, incidental exposure, gradually transforming passers-by into conscious viewers.

To enhance interpretability, informational posters are planned in selected zones marked by the highest concentration and diversity of fossils. These posters will include descriptions of the rock types, fossil groups, and palaeoenvironmental settings represented in the slabs. Visitors will be encouraged to independently identify fossil forms visible in the floor.

Digital extensions constitute an integral part of the exhibition design. QR codes placed near poster locations will link to dedicated web resources hosted by UKEN, offering expanded descriptions, high-resolution photographs, bibliographic references, and 3D reconstructions of Devonian marine ecosystems. Augmented Reality elements will allow users to visualize reconstructed organisms directly above their fossil remains, reinforcing the connection between fossil evidence and living organisms.

This approach emphasizes experiential learning, repetition, and surprise, fostering long-term cognitive engagement rather than short-term informational transfer.

3.3. Comparative Analysis with Selected Palaeontological Exhibitions

To evaluate the uniqueness and scientific value of the UKEN in situ exhibition, it was compared with selected palaeontological collections located in Kraków (AGH University of Kraków, Jagiellonian University Nature Education Center, and Institute of Geological Sciences of the Polish Academy of Sciences—ING PAN) and Kielce (Geonatura Geoeducation Center).

All analyzed collections contain Devonian palaeontological material and are publicly accessible within educational or museum institutions. However, they differ significantly in exhibition form, interpretative infrastructure, and visitor engagement model.

At AGH University of Krakow, Devonian fossils are few and belong to the exhibition titled “Paleobiology: Innovations in the History of Life.” The exhibition mainly includes reconstructions and replicas of fossils found in the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland. These include a solitary rugose coral (Figure 6B), casts of skeletal plates of placoderm (Figure 6C), and replica of the world’s oldest tetrapod tracks (Figure 6D), as well as specimen of trilobite (Odontochile) from Morocco (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Fragment of the permanent exhibition in the AGH University of Krakow—“Palaeobiology: innovations in the history of life” concerning the adaptation of organisms to life in Devonian environment. (A) Odontochile sp. trilobite (Morocco). (B) A solitary rugose coral (Holy Cross Mountains, Poland). (C) Casts of skeletal plates and scales of a placoderm (Holy Cross Mountains). (D) Scaled-down replica of the world’s oldest tetrapod trackways (Holy Cross Mountains). Photos are taken by authors.

The Jagiellonian University Nature Education Center presents extensive, well-labelled ex situ fossil collections supported by multimedia and reconstructions. Among the fossils, there are numerous specimens of extinct cephalopods belonging to the family Goniatitidae (Figure 7A,B), corals (Figure 7C) and brachiopds (Figure 8D), originating primarily from Poland.

Figure 7.

Fragment of the permanent exhibition at the Nature Education Centre of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków—“The history of life on Earth from the Precambrian to the present day”, devoted to the Devonian system, with fossils from the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland. (A,B) Extinct cephalopods (family Goniatitidae). (C) Corals of the species Acanthophyllum heterophyllum. (D) Brachiopod of the species Spirifer elegans. Photos are taken by authors.

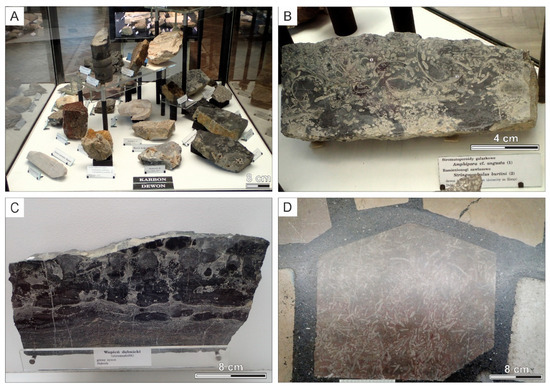

Figure 8.

Fragment of the permanent exhibition at the Geological Museum of the Research Centres of the Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków—“Geological structure of the Kraków area”, focusing on Devonian rocks and fossils. (A) Carbonate rocks from various marine environments in Sourthern Poland. (B) Branchial stromatoporoid (Amphipora cf. angusta) and hinged brachiopod (Stringocephalus burtini). (C) Stromatolite with massive stromatoporoids and traces of organism penetration in hard sea bottom. (D) Fossils of Amphipora sp. Photos are taken by authors.

ING PAN offers classical museum displays. The section of the exhibition devoted to the Devonian period includes fossils from the area around Kraków city, where there are facies of dark organogenic and nodular limestones known as the Dębnik limestone, which are characteristic of this region and are widely used as cladding slabs in Polish medieval architecture. The fossils at the exhibition include various limestones and dolomites (Figure 8A,C), stromatoporoids (Figure 8B–D), brachiopods (Figure 8B), and corals (Thamnopora sp., Stelechophyllum sp.).

The Geonatura Geoeducation Center in Kielce offers a comprehensive exhibition integrating fossils, reconstructions, multimedia, and direct access to nearby geological sites. The palaeontological collection includes, among others: cephalopods (clymeniids and goniatitids; Figure 9A,B), stromatoporoids (Figure 9C), rugose corals (Tetracorallia; Figure 9D), as well as trilobites, crinoids, bivalves, gastropods, and brachiopods.

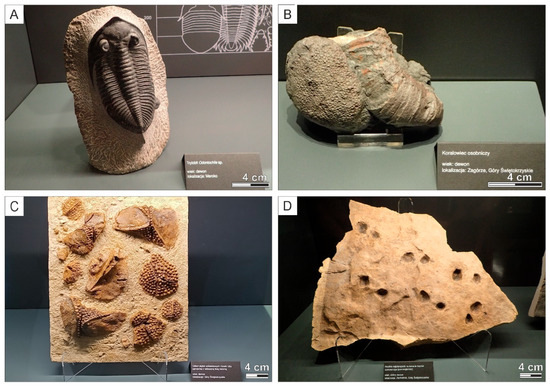

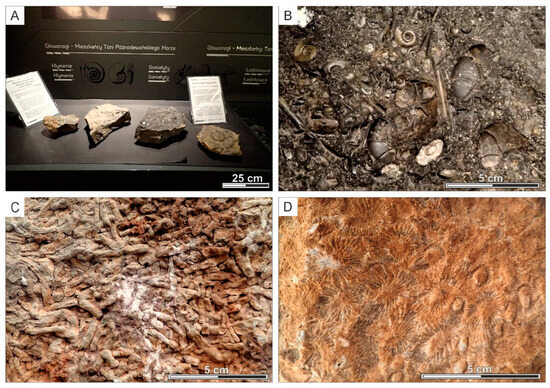

Figure 9.

Geoeducation Center of the Geonatura Kielce—a permanent exhibition devoted to the geological heritage of the Holy Cross Mountains. (A,B) Extinct cephalopods. (C) Fossils of Amphipora sp. (D) Colonial rugose corals. Photos are taken by authors.

To demonstrate the uniqueness of the proposed collection located in the UKEN building, an expert evaluation was conducted and compared with other accessible collections in Kraków and Kielce (AGH, UJ, ING PAN, GC). The evaluation was independently performed by four experts. Their assessments were then analysed according to the principles of expert triangulation. Regarding the first group of criteria, Scientific and Cognitive Values, all assessed collections were classified as Class II collections with high scientific and cognitive values. The highest-scoring collection was GC located in Kielce (16 points), while the lowest-scoring collection was at the UKEN (13.25 points). The detailed assessments of experts 1 and 2 are consistent with the average assessments; expert 3 gave the highest assessments to the UKEN and UJ collections, and the lowest to the AGH collection, while expert 4 gave the highest assessments to the GC and UKEN collections, and the lowest assessments to the UJ collection (Supplementary Materials: Table S2).

The experts were nearly unanimous in their final ratings, as evidenced by the standard deviation values of 2.16 for ING PAN. For AGH and UJ, this agreement was moderate (3.10–3.56), while for UKEN and GC, the ratings varied, with standard deviation values of 4.35 and 4.76, respectively. Examining the individual criteria, the ratings also varied; the same criterion may be rated highest by one expert and lowest by another. This stems directly from their knowledge and experience, as illustrated in Table S3 of Supplementary Materials, where experts did not completely agree on the occurrence of the listed fossil types. The smallest differences in ratings are found in the “use limitations assessment”.

The second set of results assessed the potential for educational and touristic uses. The collections assessed according to this group of criteria were placed in Group I, which includes collections with special educational and touristic value (AGH, UJ, ING PAN, and GC), and in Group II, which comprises collections with high educational and touristic value (UKEN). These results should not be surprising, as all the collections made available are easily accessible, described, and available for educational and touristic purposes. Although UKEN is not yet a publicly available collection, it has also received very high ratings.

In the expert assessment of this group of criteria, the experts rated the Kielce collection the highest (36.75 points), and the UKEN collection the lowest (29.25 points). The experts were almost unanimous in their assessments, as evidenced by the very low to moderate standard deviation values, ranging from 1.26 (UJ, GC) to 3.20 (ING PAN). Only the UKEN collection assessments yielded slightly higher standard deviation values of 5.56 (Supplementary Materials: Table S2).

The experts unanimously assessed only one criterion—Safety. There were slight discrepancies in the other criteria (Supplementary Materials: Table S2). The final collection score (Total Geoheritage Value) ranged from 18.05 points (UKEN) to 22.23 points (GC). All collections are characterized by high cognitive value and educational and tourist potential and were placed in Group II according to Warszyńska’s classification [23].

Quantitative geoheritage valorization shows that all assessed collections possess high scientific and cognitive value. The UKEN collection scored slightly lower in formal educational and touristic potential due to the current lack of dedicated exhibition infrastructure, but it achieved high scores for geological diversity, scientific knowledge, and integrity. The Total Geoheritage Value places the UKEN exhibition within the same high-value category as established museum collections.

4. Discussion

4.1. Educational Significance of In Situ Palaeontological Exhibitions

The results demonstrate that in situ palaeontological exhibitions integrated into public space offer substantial educational advantages over traditional ex situ displays. By preserving fossils within their original sedimentary matrix, polished stone slabs provide access to authentic geological information, including spatial distribution, fossil associations, and taphonomic features. These characteristics are rarely accessible in conventional museum settings, typically isolated to enhanced taxonomic clarity.

The exhibition at UKEN facilitates observational learning based on real-world rock data rather than abstract representations. Viewers are encouraged to interpret fossil morphology, recognize biological affinities, and relate fossil assemblages to depositional environments. This approach supports experiential learning and strengthens the connection between palaeontology, geology, and biology, responding directly to the need identified by the viewers to emphasize the educational potential of real rock material and polished sections.

Moreover, the exhibition enables repeated exposure to the same fossil-bearing surfaces, fostering long-term learning processes (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Such cumulative engagement is particularly relevant in academic environments, where students may encounter the exhibition throughout their studies, gradually developing more advanced interpretative skills [35,36].

4.2. From Passer-By to Viewer: Cognitive and Social Dimensions of Musealization

A central contribution of this study is the demonstration that musealization can occur outside institutional museum frameworks. The transformation of passers-by into viewers is achieved through the integration of palaeontological content into everyday circulation spaces, eliminating physical, temporal, and psychological barriers typically associated with museums. This model promotes spontaneous, self-directed engagement with scientific content. The absence of predetermined visitor pathways allows individuals to construct their own interpretative trajectories, guided by curiosity rather than obligation. Such informal learning environments have been shown to enhance motivation and inclusivity, particularly for audiences who are not traditionally engaged with the Earth sciences.

The social dimension of the exhibition is also significant. Shared spaces encourage discussion, peer learning, and interdisciplinary exchange, especially within a university context. Students from zoological, biological, pedagogical, and social science disciplines are exposed to palaeontological content in a non-specialist setting, broadening the societal relevance of the discipline.

4.3. Geoheritage and Geotourism Implications of Urban Palaeontological Exhibitions

The integration of fossil-bearing stone cladding into public architecture expands the concept of geoheritage beyond natural outcrops and protected geosites. The UKEN exhibition represents an example of urban geoheritage, where geological and palaeontological values are embedded within the built environment.

From a geotourism perspective, such exhibitions offer low-impact, sustainable alternatives to traditional geotouristic destinations. They are accessible year-round, independent of weather conditions, and require minimal infrastructure. The scientific authenticity of the fossils enhances the credibility and educational value of the experience, while their unexpected presence in everyday settings increases public awareness of geoheritage.

Importantly, the exhibition demonstrates that materials commonly perceived as decorative or functional can possess significant scientific value. Recognizing polished fossil-bearing stone as geoheritage contributes to the protection and appreciation of geological resources that are often overlooked or undervalued.

4.4. Comparative Analysis of the UKEN Exhibition and Traditional Palaeontological Displays

The comparative analysis of the UKEN in situ exhibition and traditional Palaeontological displays highlights fundamental differences in philosophy exhibition, modes of engagement, and educational outcomes. While museums such as the AGH University of Krakow Museum, the Jagiellonian University Geological Museum, the Institute of Geological Sciences of the Polish Academy of Sciences (ING PAN), and the Geopark and Geological Center in Kielce prioritize curated narratives and taxonomically organized collections, the UKEN exhibition emphasizes contextual integrity and everyday accessibility [8].

Traditional museum exhibitions are based on ex situ specimens, carefully selected, prepared, and displayed to illustrate taxonomic diversity and evolutionary trends. This approach allows for precise identification and controlled interpretation but often removes fossils from their original sedimentary and paleoecological context [37]. In contrast, the UKEN exhibition preserves fossils within continuous rock surfaces, enabling observation of fossil assemblages, spatial relationships, and sedimentological features that are rarely visible in museum showcases.

From an educational perspective, museum exhibitions support structured learning guided by explanatory texts and expert curation, whereas the UKEN exhibition facilitates exploratory and self-directed learning. The absence of predetermined viewing paths at UKEN encourages viewers to construct personal interpretative frameworks, guided by curiosity and repeated exposure rather than formal instruction. This difference is particularly relevant in academic environments, where informal learning complements formal curricula.

The comparative analysis also reveals differences in audience reach and inclusivity. Museum exhibitions primarily attract intentional visitors with a pre-existing interest in Earth sciences, while the UKEN exhibition engages a broader and more diverse audience, including students and staff from non-geological disciplines. This broader reach enhances the societal impact of palaeontology and supports interdisciplinary knowledge transfer [38].

Importantly, the UKEN exhibition does not replicate museum functions; instead, it operates as a complementary platform. Museums provide depth, taxonomic resolution, and historical continuity, while in situ exhibitions offer authenticity, immediacy, and constant availability. Together, these approaches form a multi-layered system of palaeontological communication, in which public-space exhibitions serve as gateways to more specialized institutional collections.

4.5. Implications for Earth Science Education and Knowledge Preservation

The findings underscore the potential of public-space palaeontological exhibitions as tools for preserving and revitalizing knowledge about extinct species. In an era marking rapid technological change and declining familiarity with natural history, direct contact with authentic fossil material plays a crucial role in maintaining scientific literacy.

By embedding palaeontology into everyday life, the exhibition counters the marginalization of Earth sciences and supports interdisciplinary education. The approach aligns with contemporary educational strategies that emphasize active learning, sustainability, and the integration of science into societal contexts.

Furthermore, the model proposed in this study is transferable to other urban settings where fossil-bearing stone is used in architecture. Its scalability and low maintenance requirements make it a viable strategy for long-term dissemination of palaeontological and geoheritage knowledge.

5. Conclusions

The palaeontological exposition occurring in the immediate surroundings, as proposed in UKEN, unnoticed in everyday activities, will draw the attention of passers-by, mostly students, showing extinct species of animals in their natural environment created by using light and multimedia effects. Unexpected presentation appearing in a public place can contribute to the wider understanding of the exhibition in the space-time perspective as a place visited by the passer-by–viewer and makes the exhibition appear unexpectedly in the place of the daily presence, transforming passers-by into visitors, while introducing an element of surprise into their everyday life. In this way, the palaeontological exhibition breaks the stereotypical approach to the visitors-exhibition relationship, at the same time broadening their perception of the surrounding reality and influencing their imagination.

Taking into account the research results presented in this article, the authors recommend that the collection be made available in a modern format in the future, so that every student passing through it is aware of the millions of years of geological history they are traversing as they move through the university corridors. This can be achieved through the use of 3D visualizations, augmented reality, and short educational films, which students can access by scanning a QR code.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/resources15010007/s1, Table S1: Detailed description of the assessment criteria; Table S2: Assessment results; Table S3: Collection features.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.-Ž. and M.B.; methodology, A.C.-Ž. and M.B.; validation, A.C.-Ž. and M.B.; formal analysis, A.C.-Ž. and M.B.; investigation, M.B., P.S., E.W. and S.B.; resources, M.B., P.S., E.W., K.A. and S.B.; data curation, A.C.-Ž. M.B., A.W., A.C. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-Ž. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, A.C.-Ž., M.B. and K.B.; visualization, A.C. and P.S.; supervision, M.B. and K.B.; project administration, A.C.-Ž.; funding acquisition, M.B. and K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by (1) the University of the National Education Commission, Krakow (Grant No. WPBU/2024/03/00125), and (2) from the Statutory Funds of the Faculty of Geology, Geophysics and Environmental Protection, AGH University of Krakow (Project 16.16.140.315).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments on the original version of the manuscript, which helped to achieve its final form.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tamborini, M. Technoscientific approaches to deep time. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part A 2020, 79, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, V. Palaeontology: Monsters from Lost Worlds. In Science, Entertainment and Television Documentary; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2016; pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, V. The extinct animal show: The paleoimagery tradition and computer generated imagery in factual television programs. Public Underst. Sci. 2009, 18, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipps, J.H. The future of paleontology—The next 10 years. Palaeontol. Electron. 2017, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, M.; Natkaniec-Nowak, L.; Naglik, B.; Bąk, K.; Dulemba, P. Organic-walled Microfossils from the Early Middle Cambrian sediments of the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland: Possible Implications for Sedimentary Environment in the SE Margin of the Baltica. Acta Geol. Sin. Ed. 2017, 91, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, M.; Sawłowicz, Z. Pyritized radiolarians from the Mid-Cretaceous deposits of the Pieniny Klippen Belt—A model of pyritization in an anoxic environment. Geol. Carpathica 2000, 51, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, K.; Bąk, M.; Dulemba, P.; Okoński, S. Late Cenomanian environmental conditions at the submerged Tatric Ridge, Central Western Carpathians during the period preceding Oceanic Anoxic Event 2—A palaeontological and isotopic approach. Cretac. Res. 2016, 63, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolska, A.; Ciurej, A.; Kowalik, S. Wykorzystanie surowca naturalnego w wystroju wnętrza gmachu głównego Uniwersytetu Pedagogicznego im. Komisji Edukacji Narodowej w Krakowie (The use of a natural resource in the interior design of the main building of the Pedagogical University of Cracow). Biul. Państwowego Inst. Geol. 2018, 472, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrowicz, Z.; Kućmierz, A.; Urban, J.; Otęska-Budzyn, J. Waloryzacja Przyrody Nieożywionej Obszarów i Obiektów Chronionych w Polsce; Wydawnictwo Państwowego Instytutu Geologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi, V.M.; Cendrero, A.; Albertos, J.A.C. A statistical approach to the validation and optimisation of geoheritage assessment procedures. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coratza, P.; Bruschi, V.M.; Piacentini, D.; Saliba, D.; Soldati, M. Recognition and assessment of geomorphosites in Malta at the Il-Majjistral nature and history park. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytrowski, P.; Kicińska, A. Waloryzacja geoturystyczna obiektów przyrody nieożywionej i jej znaczenie w perspektywie rozwoju geoparków. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2011, 29, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fassoulas, C.; Mouriki, D.; Dimitriou-Nikolakis, P.; Iliopoulos, G. Quantitative Assessment of Geotopes as an Effective Tool for Geoheritage Management. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koźma, J. Opracowanie Zasad Identyfikacji i Waloryzacji Geotopów dla Potrzeb Sporz Dzania Dokumentacji Projektowych Geoparków w Polsce z Zastosowaniem Systemów GPS i GIS; Archiwum Państwowego Instytutu Geologiczneg: Warszawa, Poland; Wrocław, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Panizza, V.; Mennella, M. Assessing geomorphosites used for rock climbing. The example of Monteleone Rocca Doria (Sardinia, Italy). Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Pereira, D. Methodological guidelines for geomorphosite assessment. Géomorphologie Reli. Process. Environ. 2010, 2, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Panizza, M. Geomorphosites: Definition, assessment and mapping. Géomorphologie Reli. Process. Environ. 2005, 11, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.L.; Fonseca, A. Geoheritage assessment based on large-scale geomorphological mapping: Contributes from a Portuguese limestone massif example. Géomorphologie Reli. Process. Environ. 2010, 2, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, E.; González-Trueba, J.J. Assessment of geomorphosites in natural protected areas: The Picos de Europa National Park (Spain). Géomorphologie Reli. Process. Environ. 2005, 11, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouros, N.C. Geomorphosite assessment and management in protected areas of Greece Case study of the Lesvos island—Coastal geomorphosites. Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybár, P. Assessment of attractiveness (value) of geotouristic objects. Acta Geoturistica 2010, 1, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Brilha, J. Inventory and quantitative assessment of geosites and geodiversity sites: A review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warszyńska, J. Waloryzacja miejscowości z punktu widzenia atrakcyjności turystycznej (zarys metody). Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Jagiellońskiego. Pr. Geogr. 1970, 27, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Chrobak-Žuffová, A. Comparison of Expert Assessment of Geosites with Tourist Preferences, Case Study: Sub-Tatra Region (Southern Poland, Northern Slovakia). Resources 2023, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, A.; Bąk, K. Poznawczo-Edukacyjne Aspekty Atrakcji Geoturystycznych Podtatrza; Wydawnictwo Naukowe UP: Kraków, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Jakość w Badaniach Jakościowych; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnocki, J. Marmury świętokrzyskie. Materiały do znajomości skał w Polsce. Biul. Państwowego Inst. Geol. 1952, 80, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczak, J. Morphogenesis and systematics of the Devonian stromatoporoidea from the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland. Palaeontol. Pol. 1971, 26, 5–147. [Google Scholar]

- Racki, G. Evolution of the bank of reef complex in the Devonian of the Holy Cross Mountains. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 1993, 37, 87–182. [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz, M.; Racki, G.; Skompski, S.; Szulczewski, M. 2006—Zapis procesów i zdarzeń w dewonie i karbonie Gór Świętokrzyskich. In Materiały Konferencyjne. Przewodnik LXLVII Zjazdu Nauk. PTG; Skompski, S., Żylińska, A., Eds.; Ameliówka, Poland, 2006; pp. 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hine, A.C.; Neumann, A.C. Shallow carbonate bank margin growth and structure, Little Bahama Bank, Bahamas. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 1977, 61, 376–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, A.C.; Wilber, R.J.; Bane, J.M.; Neumann, A.C.; Lorenson, K.R. Offbank transport of carbonate sands along open, leeward bank margins: Northern Bahamas. Mar. Geol. 1981, 42, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różkowska-Dembińska, M. Korale dewońskie Gór Świętokrzyskich. Wiadomości Muz. Ziemi 1949, 4, 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kiełczewska, J. Świętokrzyskie marmury i wapienie—mały przewodnik po polskich zabytkach. Cz. 1. 2013. Available online: https://surowce-naturalne.pl/swietokrzyskie-marmury-i-wapienie-maly-przewodnik-po-polskich-zabytkach-cz-i/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Betzner, J.P.; Marek, E.A. Teacher and student perceptions of earth science and its educational value in secondary schools. Creat. Educ. 2014, 5, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trend, R. Influences on future UK higher education students’ perceptions and educational choices across Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences (GEES). J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2009, 33, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, J.T.M.; de Souza Carvalho, I. Geological or Cultural Heritage? The Ex Situ Scientific Collections as a Remnant of Nature and Culture. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniewicz, P. Bringing the history of the Earth to the public by using storytelling and fossils from decorative stones of the City of Poznań, Poland. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 1827–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.