Abstract

The exploitation of agri-food industrial by-products to produce novel foods is a promising strategy in the framework of policies promoting the bioeconomy and circular economy. Within this context, this study aims to examine the effect of food neophobia and food technology neophobia in the acceptance of a novel food by consumers (through an EU research project: Sybawhey). As a case study, a functional yogurt-like product was developed by synergistic processing of halloumi cheese whey, enriched with banana by-products. The present study contributes to the literature by examining consumers’ perceptions for such a novel food, identifying the profile of potential final users and classifying them according to their “neophobic tendency”. A comparative approach among groups from Greece, Cyprus and Uganda was adopted to explore whether respondents have a different attitude towards this novel yogurt. Results suggest that there is a potential for increasing consumption of novel foods derived by agri-food industrial by-products, but more information about the importance of using by-products are required to enhance consumers’ acceptance of this novel food. Such results may be useful to policy makers, aiming to promote strategies towards the effective reuse of food outputs leading to the manufacture of sustainable novel foods.

1. Introduction

Sustainable food systems that facilitate the valorization of food waste and by-product streams to produce new raw materials for the manufacturing of safe, healthy, and nutritious food are vital [1]. Through the bioeconomy and circular economy contexts, the ambition of novel food policies is to transform by-products and waste into useful raw materials for industrial applications. In this direction, by-products from dairy industries (e.g., whey) receive great attention in sustainable food management. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [2], dairy whey is, “the liquid substance obtained by separating the coagulum from milk, cream, or skim milk in cheese making”. Whey disposal is an immense obstacle for the dairy industry, being expensive and challenging. In Greece and Cyprus, the dairy whey is stored and transported to pig farms where it is used for feeding purposes while it could be used as a source of proteins and sugars. Whey valorization using microbial fermentation to produce health-promoting yogurt provides sustainable alternatives for the exploitation of whey surplus. Although waste management and recovery of raw materials is a common challenge worldwide, it is still less adopted by developing countries, especially in Africa [3]. Africa produces one of the largest amounts of fruits in the world. To benefit from this, Africa needs to take full advantage of its resources. The banana and plantain tree industry is of vital importance to Uganda. With the objective to increase the sustainability of the banana sector, banana utilization into high-value products, making use of novel food technologies and current trends in the food manufacture, is a challenge.

According to the EU Regulation 2015/2283 [4], a novel food is “a newly developed, innovative food; a food produced using new technologies and production processes; or a food that is or has been traditionally eaten outside of the EU and has not been consumed within the EU to a significant degree”. Hence, the legal concept comprises novel foods, whether based on the production process, ingredients, or culture [5].

Inserting a novel food in the market is likely to pose challenges. Policy initiatives aimed towards food waste management are often under question, as various concerns affect their effectiveness. In the food sector, food neophobia is such an issue. Valuable resources are sacrificed to produce technologically superior and novel food products without success in the market. Prior research on evaluating consumers’ perceptions for such products and their performance in the market is usually absent, resulting in limited demand and market failure [6,7]. There are uncertainties which contribute to low consumption intentions [8]. Consumers’ perceptions and attitudes towards the consumption of novel food products, arising from the exploitation of agri-food industrial by-products and wastes, are quite critical and dubious for food innovations [9]. Consumers bring their own set of requirements and goals [10], and thereby knowing them beforehand, the probability of failure can be reduced. According to Johns et al. [11], the establishment of a novel product relates to the rate of diffusion to the number of individuals who have already adopted it. Thus, relative quantitative and qualitative research is necessary for the examination of such products’ acceptance by the market and consumers. This is essential to safeguard as much as possible the resources of food producers.

An element that may affect food perceptions is food neophobia (FN), which is characterized as an individual personality trait [12], manifested in the extent to which a person is reluctant or afraid to test a novel or unfamiliar food. At the same time, FN is also considered as a form of behavior associated with or involving the rejection or avoidance of novel foods within a particular situation [13]. Thus, food-related personality traits have been highlighted as a significant driver of food preferences [13].

Research on FN was remarkably aided by the deployment of the food neophobia scale (FNS) [12]. Damsbo-Svendsen et al. [14] found that the availability of novel foods has greatly increased, and the interpretation of what “novel” foods are has changed since the FNS was developed. Additionally, neophobia may concern specific groups of food products (e.g., herbophobia) [15]. The development of the FNS motivated the increase in research into neophobia, but little of the published research has been aimed at food product development [16]. Since FN can influence preferences towards novel foods [17], food product developers and marketers are faced with the issue of understanding its potential impact on consumers’ food choices. Hence, the food industry needs more systematic knowledge on consumer behavior, especially their perceptions in food risks and benefits.

The FNS has been verified and validated as an applicable method for assessing reactions to non-traditional ethnic foods [12,18,19]. However, it is suspected that some statements in the FNS are not relevant [14]. In line with this, Ritchey et al. [20] demonstrated that excluding two or four statements from the FNS improves the method when it is used. Studies have found that the FNS accurately predicts responses to new or unknown foods [20,21,22,23]. Several studies on FN using the FNS have shown large individual variations. The variations indicated in these studies were related to culture [20], socio-economic status [24], socio-demography using mainly gender and age [25,26,27]. These variations have also been described in temperamental traits, such as sensation seeking [28], emotivity [29], anxiety [30], and neuroticism [31].

The progress in technology in recent years, promotes the growth of new processing technologies [32], setting a fertile ground for both novel food and food packaging techniques to emerge [33,34]. The increase in the research interest in food processing and production derives from the benefits that are perceived from healthier, and safer foods, by saving energy, and water with less waste production [35] to enhance environmental sustainability [36] and increase food production. The success of emerging food technologies largely depends on individuals’ behavioral responses to the innovation. These technologies promote innovations in the food sector, nonetheless, not all technologies are equally accepted [33]. Humans are aware of hazards associated with food applications [37]. According to Cox and Evans [18], the FNS is not the suitable tool for assessing acceptance of foods produced by new technologies, so they developed and validated the Food Technology Neophobia Scale (FTNS) to establish the acceptance limits of foods produced by new technologies, by identifying segments of the population that have greater, or lesser technology neophobia. The ability to determine clusters that are willing to accept novel foods produced by new technologies can be helpful, especially when they can provide benefits [38].

According to some studies, acceptance of new food technologies is a result of heterogeneous preferences and attitudes among humans, which may influence their food choices [13,34,39,40,41]. The essential factors that contribute to consumers’ resistance to try foods produced by new technologies include functional barriers associated with the demographic indicators and lifestyle factors, knowledge and attitudes, perceived ease of use and usefulness, benefits and risks and psychological barriers [40,41,42].

Within the above context, the present study aims to classify participants according to their “neophobic tendency” and subsequently to investigate their acceptance behavior for a novel food produced from agri-food industrial by-products. A scenario was presented about a functional yogurt derived from halloumi whey enriched with banana by-products which can potentially provide health benefits. Τhe study aims at filling a literature gap contributing to the current literature, to both explore consumers’ perceptions of novel foods derived from agri-food industrial by-products in study areas and to profile respondents grouping them into clusters based on the impact of food phobia and technophobia and furthermore analyse their perceptions and attitudes towards novel foods derived from agri-food industrial by-products.

Research findings might be the first step in the study areas for a better understanding of consumers’ reactions towards foods derived from by-products and their future marketplace acceptance. The knowledge derived from the study could guide food manufacturers in developing novel and functional products in line with consumers’ understanding and in the framework of policies supporting the bioeconomy and circular economy. It should be highlighted that there is a segment of innovative consumers that represent a key market, playing an essential role in the success of a novel product as they legitimize the novel products to other consumers.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: The Material and Methods section describes the performed statistical methods and the research process. The following section presents the results of the study. Finally, the discussion and the conclusions of the study are presented.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Research Procedure, Study Areas and Sample Size

The present study uses data from the Marie Skłodowska-Curie RISE 2015 project, “Sybawhey-Industrial Symbiosis for Valorising Whey and Banana Wastes and By-products for the Production of Novel Foods”. Sybawhey aimed at a transnational partnership between Europe and Africa on developing innovative and sustainable processes to convert and combine by-products and waste streams from the dairy and banana industry, with limited positive or negative economic and environmental impact, into useful food products with high input to the same or different industrial plants.

Selection criteria of study areas took into account the novel functional yogurt, as it draws on great volumes of underused by-products from banana production in Uganda, and the environmentally-toxic halloumi whey produced by Cyprus dairies. The novel food (Scheme 1) includes new substances, namely green banana flour and halloumi cheese whey, as alternative sources of fibers and proteins with high nutritional value. Examples of similar types of novel foods, especially accepted by EFSA, include fresh dairy products such as yogurts, in which native guar gum may be used as a food ingredient or yogurt containing Chia seeds (Salvia hispanica) [43]. The countries were defined by the Sybawhey project as they were partnership members, where the market analysis concerned Greek consumers, as a new marketplace for this novel functional yogurt.

Scheme 1.

Hallumi whey-based yogurt-like product enriched with green banana peel flour (product subject of study).

Quantitative analysis was used, based on 700 questionnaires conducted with randomly selected respondents in the urban areas of Greece (n = 384), Cyprus (n = 222), and Uganda (n = 94). This was achieved by collecting data through three surveys carried out in the period July–September 2017 for the Cyprus sample, during September–November 2017 for the Uganda sample and for the Greek sample in the period August 2018–February 2019 (each study area was a different deliverable of the Sybawhey project with different deadlines). Surveys in Cyprus and Greece were conducted using personal (one-to-one) interviews in public places (e.g., the university campus, supermarkets, etc.). In Uganda, a researcher randomly recruited individuals to fill in the questionnaire in the university campus. The respondents participated voluntarily based on their willingness and availability to participate in each survey.

2.2. Questionnaire Design

Prior to the sampling, a preliminary field research, including several focus groups (individuals with different income and educational levels) and a pilot study, was conducted for refining, and developing the survey instrument. Research subjects were (i) the classification of participants according to the “neophobic tendency”, (ii) the examination of the current attitudes of participants towards the acceptance of a novel yogurt developed by agri-food industrial by-products and the factors responsible for each behavior (acceptance/rejection), and (iii) the presentation of the findings in a comparative form for each study area. The sequencing of questions is as important as the questions themselves [44], and it was designed to maintain interest in the questionnaire.

The design process of the questionnaire included three sections. The first section referred to socio-demographics aspects. These questions were very useful in explaining the determinants of profiles. The second section of the questionnaire focused on a 9-item version of FNS and FTNS. The respondents were asked to indicate the degree of their agreement or disagreement, using a five-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree) (Table 1).

Table 1.

FNS and FTNS survey questions.

In the last section of the questionnaire the scenario used offered the participants a description of the proposed functional novel yogurt. This stage was crucial since it was necessary to make credible the proposed functional novel yogurt, including its implications in terms of wellbeing. Consequently, the information provided should be accurate, sufficient, and fully understandable. Specifically, respondents were presented with the following scenario: “Suppose that a novel “functional” yogurt that contains dietary fibers, natural flavorings with fruity aromas (banana flavor) and beneficial microbial cultures (probiotics) appears on the market. This “functional” yogurt is derived from halloumi whey, which has been enriched with by-products (e.g., peel) of banana processing. Suppose also that a typical yogurt (200 g) costs an average of €0.90”. Consequently, the acceptance of this functional novel yogurt was investigated and then the factors contributing to each behavior (acceptance/rejection), as well the willingness to pay for it. The main factors controlling the acceptance are cost, health aspects, curiosity, and environmental issues. These variables have emerged from the focus group discussions.

To address the other critical aim of the present study, the following questions led to the investigation of the profiles of potential final users of the novel yogurt in the study areas.

- “Do you know that by-products/wastes of the food industry can be reused as raw materials to produce food and their ingredients?”

- “Are you willing to spend time to learn about the exploitation of by-products/wastes from the food industry to produce food and ingredients? (Internet, TV, scientific workshops, leaflets, etc.)?”

- “Are you willing to consume this novel “functional” yogurt?”

- “Are you willing to pay more to get it and taste it?”

2.3. Measuring Scales of Food Neophobia and Food Technology Neophobia

FNS consists of ten statements and FTNS consists of thirteen statements, scored in a Likert scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to seven (strongly agree). FN in this study was measured by using five statements and FTN was measured by using four statements selected from the widely used scales [12,18]. Due to the minimum number of FNS and FTNS statements included at this study (Table 1), the clusters were labeled according to the “neophobic tendency”. A five-point scale was used in the surveys of Cyprus and Uganda, instead of the seven-point scale traditionally used with the FNS and FTNS.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The multivariate analysis was selected, having scientific and applicability advantages [45]. Multivariate analysis is an ever-expanding set of techniques for data analysis that encompasses a wide range of possible research situations [46]. Data were recorded in a specific formulated sociological matrix using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25.0 for Windows). Three statistical methods were used for data analysis: descriptive statistics (DS), two-step cluster analysis (TSCA) and categorical regression model (CatReg). Prior to the CatReg model, a reliability analysis was used to determine the extent to which the neophobia items are related to each other. The value of Cronbach’s alpha (a) reliability coefficient was found equal to 0.657 for the Greek sample, indicating satisfactory internal reliability. The Cyprus sample it was found equal to 0.293 and the African sample it was found equal to 0.227.

Through DS, results were analysed concerning respondents’ profile regarding the neophobic tendency and the acceptability of the novel yogurt. Classification of respondents regarding their neophobic tendency in relation to food and food technology was obtained by using two-step cluster analysis (TSCA). The two-step clustering methodology was first employed as a scalable algorithm designed to handle large datasets, revealing natural groupings within a dataset that would otherwise not be apparent. While TSCA requires only one dataset, it uses a two-step procedure. At the first stage pre-clusters the cases into several smaller sub-clusters and at the second stage clusters the sub-clusters of the first stage into the desired number of clusters. The algorithm can also automatically select the number of clusters. Since the number of sub-clusters is smaller than the number of original records, traditional clustering methods can be used effectively [47,48]. Authors chose the number of clusters based on the subject segmentation approach used by Torri et al. [49] where the subjects were divided into three groups.

Categorical regression (CatReg) methodology was used to the results of the two-step clustering methodology, in order to explore in depth, the possible associations between the variables of the study and to explain the clustering results. CatReg is a modern regression technique, much more holistic and effective than the multiple regression analysis and the analysis of multiple regression with categorical variables [47]. The CatReg model can deal more optimally with both qualitative and quantitative data, as it works on two discrete and simple stages. Firstly, the nominal and ordinal variables are transformed to interval scales to maximize the relationship between each predictor and the dependent variable, and secondly, multiple regression analysis is applied to the transformed variables [47,50,51]. The relative importance measure indicates the percentage of explanation of the dependent variable while they can also be used to predict the future values of the dependent one [47,52,53]. Although the methodology of the chosen empirical techniques is rather novel in food phobia and technophobia issues, it has been selected due to the ability to optimally handle categorical variables.

3. Results

3.1. Study Area: Greece

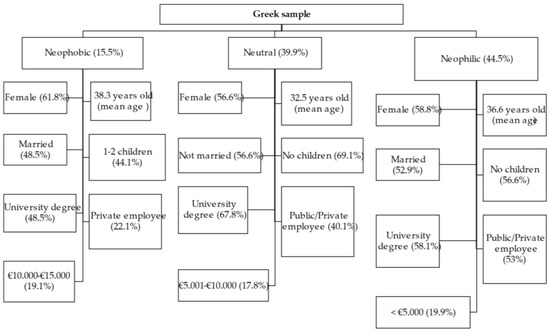

The results of TSCA for the classification of the sample according to the “neophobic tendency” led to three clusters. By analyzing the outcomes, it became obvious that respondents comprise three distinct clusters in terms of “neophobic tendency”. On the one hand, is the group with “low” neophobic tendency, labeled as “neophilic” consisting of the second cluster (44.5%). The first cluster can be labeled as “neutral” (39.9%), and the neophobic respondents consist of the third cluster (15.5%). Then using DS, each cluster has been grouped and profiled. Figure 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of each cluster.

Figure 1.

Profiles of “neophobic tendency” in Greece.

Investigating further the “neophobic tendency”, to find out how it is influenced by personal characteristics, the CatReg model was employed. The CatReg model yielded a value of coefficient of multiple determination R2 = 0.246 which indicates that 24.6% of the variance of the transformed values of the dependent variable explained by the transformed values of the independent variables of the regression equation. While examining the relative importance measures of the independent variables the relative importance of independent variables showed that the most influential factors (importance > 0.1) predicting “neophobic tendency” correspond to “age” (accounting for 35.7%) followed by “educational level” (23.7%), “annual family income” (18.9%) and “occupation” (13%) (Table 2). The presentation of the results is narrowed only by the relative importance measures, while the dependent variable cumulatively explained by the above independent variables by 24.6%.

Table 2.

Measures of correlations and tolerance of Greek sample.

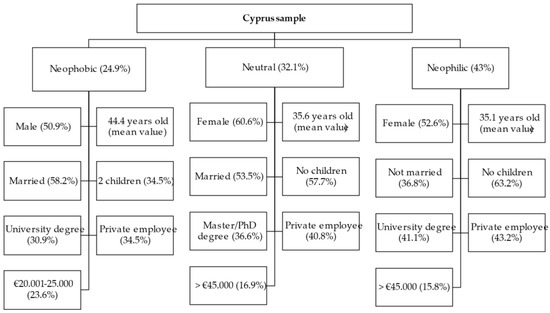

3.2. Study Area: Cyprus

The analysis of the Cyprus sample for the segmentation according to the “neophobic tendency”, led to three clusters. After the DS method, the demographic characteristics of each cluster appeared. The first cluster can be labeled as “neophobic” (24.9%), the second cluster is characterized by “low” neophobic tendency (43% “neophilic”) and the third cluster is the neutral cluster (32.1%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Profiles of “neophobic tendency” in Cyprus.

A CatReg model was employed also at this sample. Since R2 = 0.479, it is indicated that 47.9% of the variance in the “neophobic tendency” ranking is explained by the regression of the optimally transformed variables used. The relative importance measures of the independent variables showed that the most influential factors predicting the dependent variable correspond to “annual family income” (accounting for 28.3%), followed by “age” (27.9%), “family size” (18.7%) and “occupation” (10.4%) (Table 3). Thus, the dependent variable cumulatively explained by the above independent variables by 47.9%.

Table 3.

Measures of correlations and tolerance of Cyprus sample.

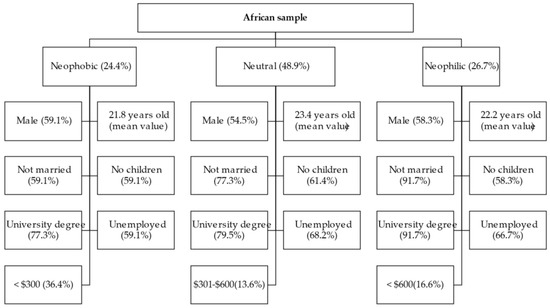

3.3. Study Area Uganda

Following the same methodology as mentioned above, the “neophobic tendency” clusters and characteristics of them in Uganda are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Profiles of “neophobic tendency” in Uganda.

The relationship between the items was further investigated through CatReg (Table 4). The most influential factors predicting neophobic profiles correspond to “annual family income” (accounting for 59.4%), followed by “marital status” (28.9%), and “age” (11%) (Table 2). The dependent variable cumulatively explained by the above independent variables by 64.8% (R2 = 0.648).

Table 4.

Measures of correlations and tolerance of Uganda sample.

Food innovations are often rejected by consumers because of food phobia and technophobia towards novel foods. One of the main research objectives was to present a scenario about a novel “functional” yogurt. As a qualitative variable (“yes”, “I am not sure”, “no”) to indicate the main factors that determine the acceptance and rejection factors, the mean value was applied to measure it (scored by a Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The Greek sample presented a high rate of acceptability of this novel yogurt (57.6%). Regarding the acceptability of the novel yogurt in Cyprus, our findings showed that 63.9% of the sample were willing to consume it. Uganda’s sample presents the highest rate of acceptability among the three samples (75.5%).

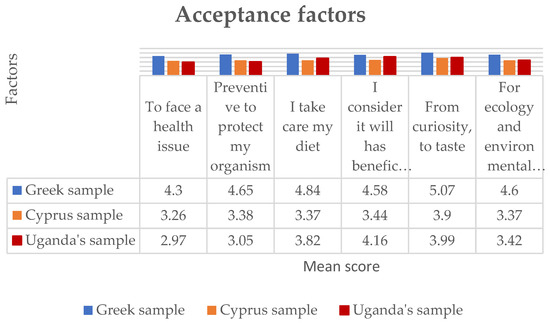

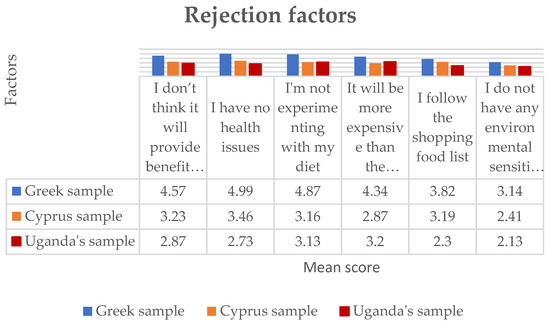

Figure 4 and Figure 5, present the main factors of respondents’ acceptance and rejection of the novel yogurt, in a comparative form for each study area. In particular, the most important reason was found to be the curiosity about the taste of the novel yogurt in Greece and Cyprus, and in Uganda the main factor was found in the beneficial effects of the novel yogurt. In addition, in these samples, we found similarities as many respondents indicated that health benefits (“I take care of my diet”, “Preventive to protect my organism”, “I consider it will has beneficial effects on my health in the long term”, “To face a health issue”) and environmental protection issues were also important reasons of acceptance. The reasons respondents indicated for not willing to taste the novel yogurt, or were not sure, was the absence of a health issue, followed by factors such as the unwillingness for diet experiments (“I’m not experimenting with my diet”), the lack of perceived benefits of the novel yogurt (“I don’t think it will provide benefits to my health”), the price of the novel yogurt (“It will be more expensive than the typical yogurt”), the predefined shopping food list (“I follow the shopping food list”), and the environmental issue (“I do not have any environmental sensitivities”). In Uganda, respondents reject the novel yogurt mostly for the expected price (“It will be more expensive than the typical yogurt”).

Figure 4.

Acceptance factors of the novel yogurt in the study areas.

Figure 5.

Rejection factors of the novel yogurt in the study areas.

3.4. Profile of Potential Final Users

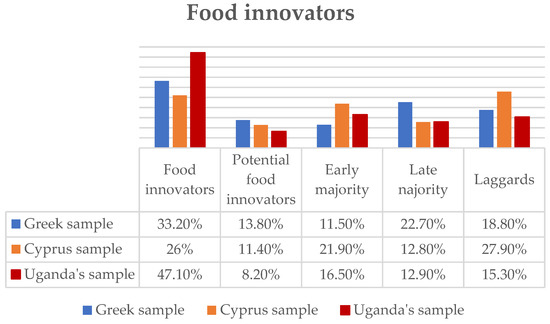

To explore a possible relationship between the food phobia and technophobia index and potential final users, respondents were divided into five groups. TSCA was applied to determine the type of respondent according to declared intentions. Then, using DS analysis, Figure 6 of respondents’ profiles emerged, in accordance with the generalizations of the related theories [54].

Figure 6.

Food innovators of study areas in a comparative form.

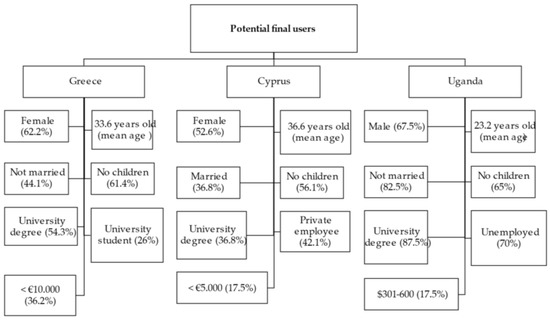

A CatReg model was employed to find out how it is influenced by personal characteristics. The most influential factors predicting these profiles correspond to “annual family income” (accounting for 29.9%), followed by “age” (20.6%), “family size” (18.9%), “marital status” (13.9%) and “educational level” (11.1%) in Greece. In Cyprus, the relative importance measures of the independent variables show that the most influential factors correspond to “educational level” accounting for 31.9%, followed by “age” (26.4%), “family size” (17.9%) and “annual family income” (10.5%), while in Uganda the most influential factors correspond to “marital status” (55.2%) and “age” (23%). A key point of concern was also the identification of the profile of the potential target group of final users in the study areas. Hence, DS was employed by the cluster of food innovators to reveal this profile (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Potential final users’ profiles of study areas in a comparative form.

4. Discussion

Familiarity and experience with innovative and novel foods enhances consumer acceptance [55,56] and are important drivers for these products. Attempts to introduce novel foods need to build on perceptions into the determinants of acceptance of such novel food products. This study revealed three profiles of neophobic tendency (“neophilic”, “neutral” and “neophobic”). The respondents within the corresponding clusters are quite different mostly among the European and the African sample. It is possible that these differences mostly stem from the cultural background. Observing the variables that shape the profiles of “neophobic tendency” in Greece and Cyprus, the technophobia variables (which belong to FTNS) are of great importance. Thus, it could be summarized that most of these consumers express phobia for the production process of the novel yogurt than a general phobia for novelty foods as such and may impact the degree to which a novel product is accepted. These results are also confirmed in a similar study in Italy [57]. Food phobia was shown to be the strongest predictor in Uganda. It is of interest that the most educated are the least neophobic. Knowledge has a significant and positive impact on consumer acceptance. The acceptance of specific functional ingredients is linked to the knowledge of their effects on health.

Samples express a “low” to “neutral” neophobic tendency, accompanied with a high acceptance rate of the novel yogurt. Consequently, it could be said that the high rate of novel food acceptance is linked to a low neophobic tendency or the opposite. Food acceptance is also a function of food phobia and technophobia, but this has not been considered in relation to the market acceptance and diffusion of new food products. In addition, food phobia and technophobia can affect an individual’s decision to consume novel foods and can be an important barrier to increasing consumption. FNS and FTNS provide a potential tool for food manufacturers, but it would need to be used with other measures to identify the target group.

The results reported herein suggest that there is a potential for increasing consumption of novel foods derived by agri-food industrial by-products, but more information about the importance of using by-products are required to improve consumer acceptance of this novel food. For this purpose, marketing tools could focus on increasing the level of knowledge about the contents of agri-food industrial by-products and its environmental and economic related aspects. Indeed, more information about these aspects may reduce the food phobia and technophobia of respondents and promote consumption. These results also indicate that the acceptance factors of novel foods are determined by curiosity in the European sample, rather than the received health benefits which were indicated in Uganda, as the novel yogurt is a “functional” food and improves health properties. The key factors of acceptance are a combination of social and individual factors, as individual factors interact with social factors. Marketing strategies could support the growth of novel foods consumption by working on different operational levers [58]. Education is essential to change the way people think. It is important to take advantage of the media and social media as potential tools for education. Promotional and informational tools should provide information on both new food technologies and products based on agri-food industrial by-products. Marketing tools, by improving the accessibility of the novel food and by giving consumers opportunities to taste it-perhaps with free samples-could be beneficial for supporting the development of a market niche. Segmenting respondents into several similarly behaving clusters and targeting them separately is the first step to more successful promotional, communication, and positioning strategies. The profiles help to explore and document different consumer attitudes towards novel foods. Moreover, the necessity to establish a link between food phobia, technophobia and purchasing behavior, is crucial to develop the neophobia into a fitting role as a food-marketing tool. These are associated to the inclusion of new technologies throughout the supply chain and are intended to lower the direct or indirect resource use. Several implications can be drawn for policy and market interventions, which address the demand and the supply sides of the novel food market. The evidence presented in this study has important implications for policy design, investment, and future research. In addition, study outcomes have significant implications for policy makers and stakeholders, which could launch campaigns that raise awareness about the exploitation of agri-food industrial wastes and by-products in the deployment of novel foods, to improve consumers’ perceptions. EU priority aims to achieve circular economy standards and resource efficiency in the food system [59]. We must realize that the introduction of policies and plans attempting to develop new foods in different ways and at different levels is imperative. Some of them may focus on starting or increasing production of new and novel foods or implementing new technologies, while other policies will aim to initiate or boost an entire industry, motivated mainly by food security. The need for greater efforts to support emergent innovation systems that strengthen novel food systems is almost demanding. Finally, policymakers should not forget the possibility to jointly investing in a closer collaboration with the private sector to build innovative capacity and skills that can accelerate novel food system improvement.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study, which are common to most studies about novel food acceptance. This is one of the first attempts in the study area of classification according to “neophobic tendency” and is limited to a rather small sample in urban centers. Furthermore, by focusing on a novel food product as a scenario, it is unable to generalize the findings to other novel foods or the food market in general. It would be therefore useful to corroborate the results by extending the aim of the study to other areas and other food innovations. Nevertheless, the observations made in this study provide a starting point for further research which could extend the investigation to a more representative sample and provide valuable information.

5. Conclusions

Within the increasing interest in analyzing food phobia and technophobia, our results suggest that the methods employed are a suitable instrument to profile the phobia towards novel foods and new food technologies and to measure acceptance of novel foods produced accompanied with food phobia and technophobia variables, constituting a valid alternative methodology as it can facilitate the application and analysis internationally. Our results also confirm that the nine-item version of the FNS and the FTNS may be a proper instrument in developing countries. Thus, the findings of this study expand the knowledge of food phobia and technophobia in developing countries, where studies are still limited. The two-step cluster analysis showed the presence of different segments of potential consumers, which can be targeted with different tools and by different actors. To validate these propositions more research and more evidence is needed. In addition, the present study is a novel tool to delineate the factors that predict acceptance of novel foods.

The results provide some guidance for the food sector and the food industry, in the terms of bioeconomy and circular economy, about the acceptance of a novel food derived from agri-food by-products and also to the identification of the target group of the market. By taking a transnational perspective on the topic of novel foods, this study revealed several insights which will not only be useful about novel foods but also for gaining insight in most areas related to food consumption and preference. Conducting research in different cultures takes a special effort, but it is worthwhile. It is of high importance to further prioritize investments in scientific research and niche market development and to capitalize on the sustainability and profitability of food systems. The above findings could serve as the impetus for action and further research. The need for further research on issues such as improved technologies in the agri-food sector, novel food value chains, and the policy interventions could encourage policies promoting bioeconomy and circular economy principles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T. and A.M.; methodology, P.T., A.M., E.L. and S.A.N.; software, P.T. and A.M.; validation, K.G. and S.A.N.; formal analysis, P.T. and A.M.; investigation, P.T., A.M. and E.M.; resources, F.T.M. and E.M.; data curation, E.L., F.T.M. and K.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T., A.M. and E.L.; writing—review and editing, E.L. and S.A.N.; visualization, P.T.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, F.T.M. and K.G.; funding acquisition, F.T.M. and K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 691228.

Data Availability Statement

Exclude this statement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Foster, T.; Hort, J. Measuring consumer emotional response and acceptance to sustainable food products. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 108992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Available online: https://bit.ly/2YVTTRW (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Guerrero, L.A.; Maas, G.; Hogland, W. Solid waste management challenges for cities in developing countries. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on Novel Foods, Amending Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 258/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1852/200. Available online: https://bit.ly/2UotbiU (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Tuorila, H.; Hartmann, C. Consumer responses to novel and unfamiliar foods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santeramo, F.G.; Carlucci, D.; De Devitiis, B.; Seccia, A.; Stasi, A.; Viscecchia, R.; Nardone, G. Emerging trends in European food, diets, and food industry. Food Res. Int. 2018, 104, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barrena, R.; Sánchez, M. Neophobia, personal consumer values and novel food acceptance. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.G.; Fischer, A.R.H.; van Trijp, H.C.M.; Stieger, M. Tasty but nasty? Exploring the role of sensory-liking and food appropriateness in the willingness to eat unusual novel foods like insects. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 48, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahl, S.; Strack, M.; Mensching, A.; Mörlein, D. Alternative protein sources in western diets: Food product development and consumer acceptance of spirulina-filled pasta. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, E.; Fovino, L.G.N. Food neophobia or distrust of novelties? Exploring consumers’ attitudes toward GMOs, insects, and cultured meat. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johns, N.; Edwards, J.S.A.; Hartwell, H. Food neophobia and the adoption of new food products. Nutr. Food Sci. 2011, 41, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Salvy, S. Food neophobia in humans. Psychol. Food Choice 2006, 3, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Damsbo-Svendsen, M.; Frøst, M.B.; Olsen, A. Development of novel tools to measure food neophobia in children. Appetite 2017, 113, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Pieroni, A. Nutritional ethnobotany in Europe: From emergency foods to healthy folk cuisines and contemporary foraging trends. In Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, A.S.; King, S.C.; Meiselman, H.L. Consumer segmentation based on food neophobia and its application to product development. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuorila, H.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Pohjalainen, L.; Lotti, L. Food neophobia among the finns and related responses to familiar and unfamiliar foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2001, 12, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.N.; Evans, G. Construction and validation of a psychometric scale to measure consumers’ fears of novel food technologies: The food technology neophobia scale. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuorila, H.; Meiselman, H.L.; Bell, R.; Cardello, A.V.; Johnson, W. Role of sensory and cognitive information in the enhancement of certainty and inking for novel and familiar foods. Appetite 1994, 23, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchey, P.N.; Frank, R.A.; Hursti, U.; Tuorila, H. Validation and cross national comparison of the food neophobia scale (FNS) using confirmatory factor analysis. Appetite 2003, 40, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado Beltrán, L.; Camarena Gómez, D.M.; Díaz León, J. The Mexican consumer, reluctant or receptive to new foods? Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 734–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Fumi, M.D.; Porretta, S. Influence of preparation method on the hedonic response of preschoolers to raw, boiled or oven-baked vegetables. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähteenmäki, L.; Grunert, K.; Ueland, Ø.; Åström, A.; Arvola, A.; Bech-Larsen, T. Acceptability of genetically modified cheese presented as real product alternative. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flight, I.; Leppard, P.; Cox, D.N. Food neophobia and associations with cultural diversity and socio-economic status amongst rural and urban Australian adolescents. Appetite 2003, 41, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Loewen, E.R. Temperament and food neophobia in children and their mothers. Appetite 1997, 28, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelchat, M.L.; Pliner, P. “Try it. You’ll like it”. Effects of information on willingness to try novel foods. Appetite 1995, 24, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P. Development of measures of food neophobia in children. Appetite 1994, 23, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galloway, A.T.; Lee, Y.; Birch, L.L. Predictors and consequences of food neophobia and pickiness in young girls. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- MacNicol, S.A.M.; Murray, S.M.; Austin, E.J. Relationships between personality, attitudes and dietary behaviour in a group of Scottish adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 1753–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, R.; Pliner, P. The food situations questionnaire: A measure of children’s willingness to try novel foods in stimulating and non-stimulating situations. Appetite 2000, 35, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Pollard, T.M.; Wardle, J. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: The food choice questionnaire. Appetite 1995, 25, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perrea, T.; Grunert, K.G.; Krystallis, A. Consumer value perceptions of food products from emerging processing technologies: A cross-cultural exploration. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C.; Sütterlin, B. Biased perception about gene technology: How perceived naturalness and affect distort benefit perception. Appetite 2016, 96, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidigal, M.C.T.R.; Minim, V.P.R.; Simiqueli, A.A.; Souza, P.H.P.; Balbino, D.F.; Minim, L.A. Food technology neophobia and consumer attitudes toward foods produced by new and conventional technologies: A case study in brazil. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rollin, F.; Kennedy, J.; Wills, J. Consumers and new food technologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, A.H.; Goddard, E.; Vandermoere, F.; Blanchemanche, S.; Bieberstein, A.; Marette, S.; Roosen, J. Do environmental attitudes and food technology neophobia affect perceptions of the benefits of nanotechnology? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, S.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Gennaro, B.D.; Corbo, F. Factors determining neophobia and neophilia with regard to new technologies applied to the food sector: A systematic review. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2018, 11, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.; Kermarrec, C.; Sable, T.; Cox, D.N. Reliability and predictive validity of the food technology neophobia scale. Appetite 2010, 54, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Steur, H.; Odongo, W.; Gellynck, X. Applying the food technology neophobia scale in a developing country context. A case-study on processed matooke (cooking banana) flour in central Uganda. Appetite 2016, 96, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewer, L.J.; van der Lans, I.A.; Fischer, A.R.H.; Reinders, M.J.; Menozzi, D.; Zhang, X.; Zimmermann, K.L. Public perceptions of agri-food applications of genetic modification—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 30, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronteltap, A.; van Trijp, J.C.M.; Renes, R.J.; Frewer, L.J. Consumer acceptance of technology-based food innovations: Lessons for the future of nutrigenomics. Appetite 2007, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Anders, S.; An, H. Measuring consumer resistance to a new food technology: A choice experiment in meat packaging. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470 Establishing the Union List of Novel Foods in Accordance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Novel Foods. Available online: https://bit.ly/3Foam59 (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Josselin, J.; Maux, B.L. Statistical Tools for Program Evaluation: Methods and Applications to Economic Policy, Public Health, and Education; Spriner: Rennes, France, 2017; pp. 1–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizou, E.; Michailidis, A.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Investigating the drivers that influence the adoption of differentiated food products: The case of a greek urban area. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, F.J.; Black, C.W.; Babin, J.B.; Anderson, E.R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning EMEA: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Michailidis, A.; Partalidou, M.; Nastis, S.A.; Papadaki-Klavdianou, A.; Charatsari, C. Who goes online? Evidence of internet use patterns from rural Greece. Telecommun. Policy 2011, 35, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, F.; Apostolidou, I.; Michailidis, A. Mapping sustainable tomato supply chain in greece: A framework for research. Foods 2020, 9, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torri, L.; Tuccillo, F.; Bonelli, S.; Piraino, S.; Leone, A. The attitudes of Italian consumers towards jellyfish as novel food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 79, 103782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Kontogeorgos, A.; Liltsi, P.; Apostolidou, I.; Michailidis, A.; Loizou, E. Small women’s cooperatives in less favored and mountainous areas under economic instability. Agric. Econ. Rev. 2016, 17, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kountios, G.; Ragkos, A.; Bournaris, T.; Papadavid, G.; Michailidis, A. Educational needs and perceptions of the sustainability of precision agriculture: Survey evidence from greece. Precis. Agric. 2018, 19, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridou, D.; Michailidis, A.; Trigkas, M. Socio-economic factors influencing farmers’ willingness to undertake environmental responsibility. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 14732–14741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizou, E.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Michailidis, A.; Tsakiri, M.; Theodossiou, G. Linkages of the energy sector in the greek economy: An input-output approach. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2015, 9, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Thawadi, S. Public perception of algal consumption as an alternative food in the kingdom of bahrain. Arab J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Profiling consumers who are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute in a western society. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, E.; Gaviglio, A.; La Sala, P.; Fiore, M. Impact of information and food technology neophobia in consumers’ acceptance of shelf-life extension in packaged fresh fish fillets. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 17, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Forleo, M.B. The potential of edible seaweed within the western diet. A segmentation of italian consumers. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 20, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Food 2030 Pathways for Action: Research and Innovation Policy as a Driver for Sustainable, Healthy, and Inclusive Food Systems. Available online: https://bit.ly/3umI2v4 (accessed on 23 August 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).