Abstract

This study proposes a stage-aware governance framework for large language models (LLMs) that structures human oversight and accountability across different decision stages in AI-assisted literature review systems. Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly embedded in systematic review workflows, yet how human oversight and accountability should be structured across different decision stages remains unclear. This study evaluates three LLMs in a controlled two-stage literature review workflow—title-and-abstract screening and eligibility assessment—using identical evidence inputs and fixed inclusion criteria, with outputs benchmarked against expert consensus under fully reproducible conditions with standardized prompts and comprehensive logging. While LLMs closely matched expert decisions during screening (precision 0.83–0.91; F1 up to 0.89; Cohen’s κ 0.65–0.85), performance degraded substantially at the eligibility stage (F1 0.58–0.65; κ 0.52–0.62), indicating increased epistemic uncertainty when fine-grained criteria must be inferred from abstract-level information. Importantly, disagreements clustered in borderline cases rather than random error, supporting a stage-aware governance approach in which LLMs automate high-throughput screening while inter-model disagreement is operationalized as an actionable uncertainty signal that triggers human oversight in more consequential decision stages. These findings highlight the need for explicit oversight thresholds, responsibility allocation, and auditability in the responsible deployment of AI-assisted decision systems for evidence synthesis.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence systems are increasingly embedded in decision-making processes across research, policy, and organizational contexts, raising critical governance questions regarding reliability, accountability, and human oversight [1]. As AI systems begin to influence inclusion, exclusion, and prioritization decisions, ethical concerns shift from abstract principles to operational governance challenges, including how uncertainty is detected, how responsibility is allocated, and when automated judgments must be escalated to human decision-makers. These issues are particularly salient for large language models (LLMs), whose outputs often appear authoritative despite substantial variability across tasks, models, and decision contexts [2,3].

Large language models (LLMs) have become integral to research workflows as versatile text classification systems capable of summarizing, filtering, and structuring scientific information. A prominent application involves their use in automated multi-stage literature review pipelines, where predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria guide progressive screening and eligibility judgments. Recent studies show that LLM-assisted screening can substantially reduce manual effort and achieve high sensitivity at the title-and-abstract level, occasionally identifying relevant studies overlooked by human reviewers [4]. However, these gains are offset by elevated false positive rates and only modest reductions in total review time. Complementary work suggests that retrieval-augmented prompting may improve complex, criterion-driven eligibility assessments by supplying contextual information absent from abstracts. Despite these advances, persistent concerns remain regarding the reliability and interpretability of model outputs, as well as performance instability across review stages, prompting strategies, and model families, underscoring the need for governance-oriented evaluation rather than aggregate performance reporting [5].

Most existing evaluations treat LLMs as “black box” classifiers and rely on single global metrics such as accuracy or F1 score, thereby obscuring systematic variation across distinct stages of the review process. Such aggregation fails to address two governance-relevant questions in evidence synthesis [6]. First, to what extent can automated inclusion and exclusion decisions be considered reliable at different decision stages, ranging from broad screening to high-stakes eligibility assessment? Second, how consistent are decisions across different LLMs when identical criteria and evidence are applied, and can disagreement itself serve as a signal of uncertainty? While prior studies often report strong screening performance, it remains unclear whether these results generalize to eligibility decisions, which require finer interpretive judgment and stricter adherence to methodological criteria.

To address these questions, the present study examines a controlled two-stage literature review workflow in which both screening and eligibility assessments are applied to the same corpus of records in wearable-based health prediction research. Three widely used LLMs—OpenAI GPT-5-nano, Gemini 2.5-flash, and Perplexity Sonar—independently evaluated identical title-and-abstract inputs using a standardized prompt specifying fixed inclusion and exclusion rules. Model decisions were benchmarked against expert consensus labels, enabling stage-specific performance comparison and systematic analysis of inter-model agreement under fully logged and reproducible conditions. The study is guided by three research questions: how accurately LLMs replicate expert judgments across screening and eligibility stages; how consistent their decisions are across models; and how observed disagreement and performance variation can be translated into concrete governance mechanisms for hybrid human–AI review systems.

Unlike prior studies that merely report stage-dependent performance variation, this study explicitly translates differences in model accuracy and inter-model disagreement into a staged governance design logic. In doing so, disagreement is reframed not simply as an evaluation artifact but as an operational uncertainty signal that informs when automated decisions remain acceptable and when they must be escalated to human reviewers.

Overall, this study contributes by reframing LLM-assisted literature review not merely as a classification task but as a staged socio-technical decision system requiring explicit governance design. Rather than proposing a new model, it empirically demonstrates where automated decision-making remains reliable, where it degrades, and how inter-model disagreement can be operationalized as an uncertainty signal to guide human oversight. In doing so, the analysis supports the development of transparent, auditable, and stage-aware governance frameworks in which LLMs enhance scalability while human expertise retains responsibility for consequential decisions.

2. Related Works

Research on large language models (LLMs) for automated literature screening and classification has expanded rapidly, forming three principal directions: (i) automated relevance filtering, (ii) prompting and task structuring for multi-criterion decisions, and (iii) evaluation practices that emphasize agreement, uncertainty, and reproducibility. These research domains collectively establish the theoretical and technical basis for stage-aware workflows in systematic literature reviews.

2.1. Automated Literature Screening

Early efforts in automated literature screening primarily relied on feature-engineered machine learning algorithms and topic-modeling classifiers that represented documents using handcrafted lexical features or latent semantic structures [7]. While these approaches offered a transparent and reproducible basis for large-scale triage, their performance was often domain-dependent and required substantial manual calibration when inclusion criteria or corpora changed. This limitation constrained their scalability in dynamic or interdisciplinary review environments.

Recent advances have shifted toward zero-shot or minimally supervised LLMs capable of interpreting title-and-abstract content directly without task-specific retraining. Empirical evaluations show that these models can function as secondary reviewers with high sensitivity, complementing human screening particularly in rapidly expanding evidence domains [8]. However, persistently high false-positive rates indicate that fully autonomous deployment remains impractical, reinforcing the view that LLMs are best situated within human-in-the-loop triage architectures rather than end-to-end automation.

Comparative studies further demonstrate that domain-specific and fine-tuned biomedical models can match or outperform general-purpose LLMs in targeted labeling tasks while offering improved efficiency and interpretability [9]. These findings suggest that automated screening is not a substitute for expert judgment but a governance-sensitive augmentation mechanism, where throughput gains must be balanced against error tolerance and downstream decision consequences. In addition, recent benchmark analyses confirm that general-purpose LLMs tend to over-generalize relevance signals in early-stage classification, while domain-adapted scientific models offer more stable and auditable decision boundaries [10,11]. This indicates that model selection itself is a governance decision rather than a purely technical one.

2.2. Prompting Strategies and Structured Decision Tasks

Performance on complex, multi-criterion decisions—particularly eligibility assessment—has been shown to depend strongly on prompt formulation and task structuring. Studies report that prompts specifying explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria, constrained response formats, and decision rationales can substantially improve both sensitivity and specificity, while also enabling reproducible evaluation across models [10]. In this sense, structured prompting functions not merely as a technical optimization, but as an operational governance layer that constrains discretionary model behavior and renders decision logic auditable within hybrid human–AI review systems.

At the same time, recent research emphasizes that prompt design itself can become a source of systematic error or epistemic distortion if not carefully aligned with task requirements. Morris (2024), for instance, cautions that overly directive or poorly specified prompts may create an illusion of methodological rigor while masking underlying uncertainty, thereby complicating rather than clarifying eligibility judgments [12]. This insight highlights the importance of designing prompts that explicitly surface ambiguity and support staged human oversight, rather than assuming that stronger or more detailed prompts alone ensure decision reliability.

In contexts where eligibility judgments depend on implicit or underspecified information, retrieval-augmented prompting has been introduced to mitigate contextual sparsity. By incorporating external evidence or reference material into prompts, such approaches can stabilize model outputs and reduce inconsistency relative to purely zero-shot inference [11]. Nonetheless, these performance gains remain uneven across domains and are often accompanied by increased system complexity and reduced transparency, raising important questions about how to balance contextual enrichment with interpretability and accountability.

Few-shot prompting has likewise been shown to narrow performance gaps between commercial and open-source models, but its effectiveness depends on exemplar selection, schema complexity, and cognitive load [13]. Collectively, this literature indicates that prompt design is not merely a technical optimization problem but a key lever for governing reliability, interpretability, and accountability in LLM-driven decision tasks. Recent work further emphasizes that prompt constraints serve as an external “governance layer,” shaping how models operationalize ambiguity rather than eliminating it. This supports the view that prompt design should be evaluated not only in terms of predictive performance, but also in terms of its ability to reduce epistemic uncertainty and support transparent escalation workflows [14,15].

2.3. Agreement, Uncertainty, and Reproducible Evaluation

Across computing and information science, evaluations of automated classifiers—including LLMs—have traditionally relied on aggregate performance metrics such as accuracy or F1 score, often overlooking issues of stability, calibration, and epistemic uncertainty. As a result, such evaluations provide limited guidance for decision-critical applications. In response, recent scholarship has called for standardized tasks, transparent reporting, and the release of auditable artifacts that document prompts, parameters, and outputs [16]. These practices form a necessary foundation for governance, because accountability cannot be meaningfully assigned without traceable and reproducible decision processes. However, existing work stops at measuring agreement and uncertainty, whereas our framework operationalizes these metrics as enforceable escalation and oversight rules embedded in a staged review architecture.

Research on human–AI teaming further demonstrates that combined system performance is heterogeneous and highly task dependent [17]. From this perspective, model disagreement should be interpreted not as noise but as a diagnostic signal of epistemic uncertainty, revealing borderline cases or latent ambiguity in inclusion criteria. Agreement measures such as Cohen’s κ and cross-model consensus have therefore emerged as potential operational indicators for triggering human review within structured workflows.

Taken together, these strands suggest that effective deployment of LLMs in evidence synthesis requires more than performance optimization [1]. What is missing from the literature is an integrated framework that links stage-specific performance variation and inter-model disagreement to concrete governance mechanisms—such as oversight thresholds and escalation rules—within reproducible decision systems. The present study addresses this gap by comparing screening and eligibility stages under standardized conditions and demonstrating how disagreement patterns can be translated into actionable governance signals.

To further clarify the distinct contribution of this work, we provide a structured conceptual comparison between the proposed stage-aware governance framework and existing human-in-the-loop and responsible AI governance approaches. While prior frameworks emphasize static review processes or post hoc auditing, they do not differentiate oversight levels according to the epistemic and decision-critical characteristics of each stage. By contrast, our framework dynamically allocates human intervention based on observed disagreement and stage-specific performance variation, positioning it as an operational extension of responsible AI principles tailored to LLM-assisted literature review workflows [18].

3. Methodology

3.1. Task and Workflow

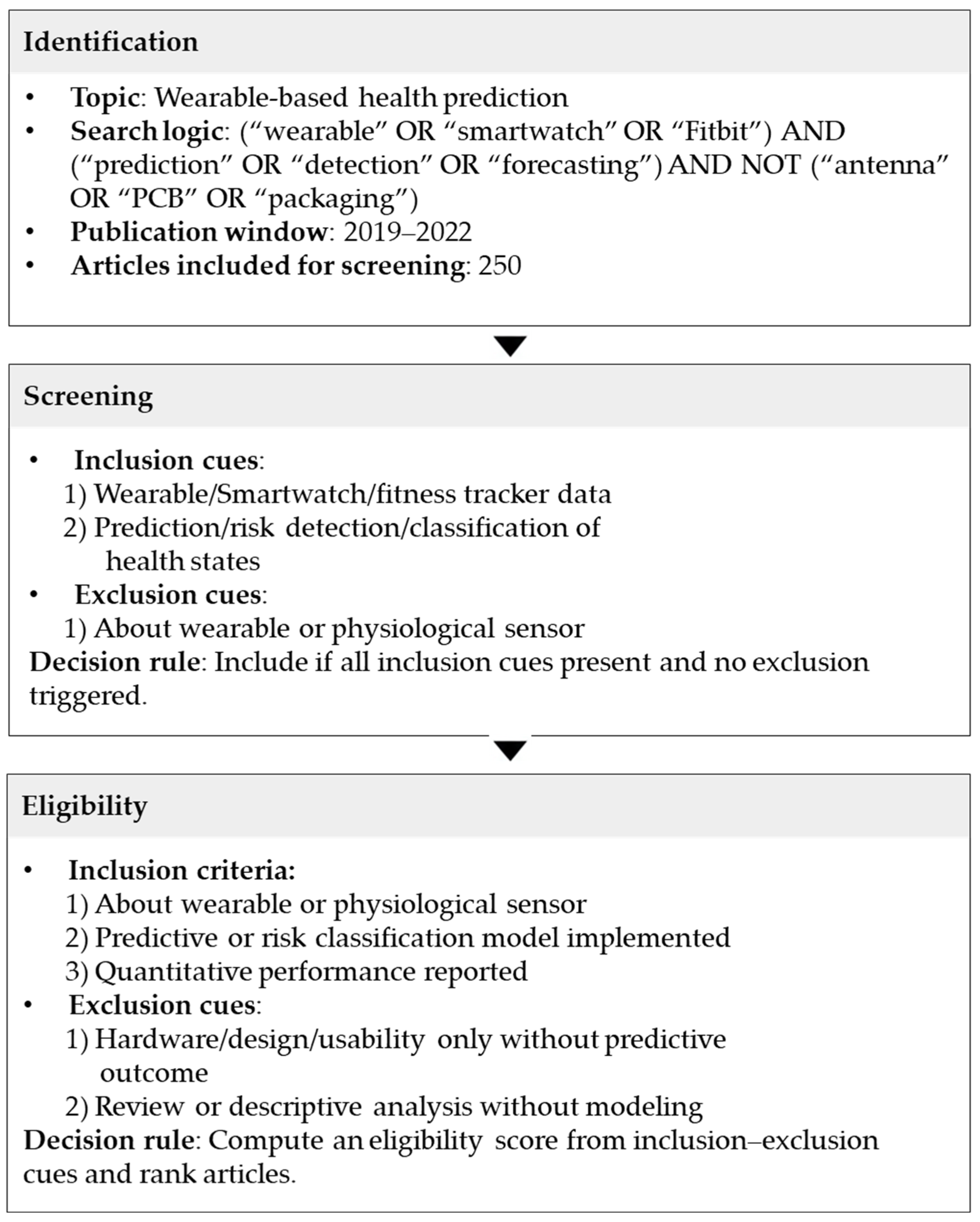

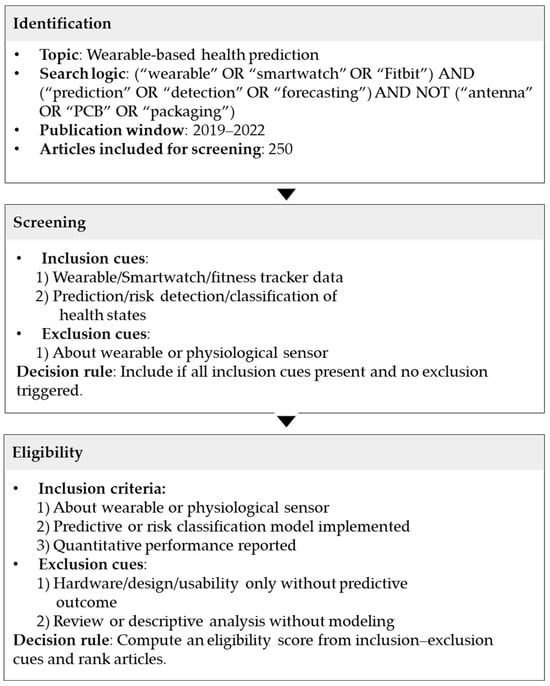

Building on prior work highlighting the stage-dependent nature of LLM performance in literature review pipelines, the present study conceptualizes the review process as a two-stage classification workflow consisting of an initial screening stage followed by a stricter eligibility assessment stage. Rather than treating this structure as a purely procedural choice, we frame it as a governance-relevant decision architecture in which the consequences of automated judgments differ systematically across stages. This design reflects standard practices in systematic and scoping reviews, where broad relevance judgments are first applied to reduce corpus size, after which more fine-grained criteria determine final inclusion. Figure 1 provides an overview of the workflow and its main components.

Figure 1.

Workflow for literature identification, screening, and eligibility assessment in the wearable-based health prediction topic.

Candidate records are first identified through standard bibliographic database searches and deduplication procedures. Both screening and eligibility assessments operate on the same title-and-abstract information, thereby holding the available evidence constant across stages. The key distinction lies in the decision logic applied at each stage. Screening relies on broad conceptual inclusion and exclusion criteria intended to maximize sensitivity and minimize false negatives, whereas eligibility assessment applies stricter methodological, population-level, and outcome-specific criteria. This contrast reflects a shift not only in task complexity but also in decision criticality.

This design choice is analytically consequential. By fixing the underlying textual evidence while varying criterion granularity, the workflow isolates the effect of task definition on model behavior. As a result, observed performance differences can be interpreted as changes in epistemic uncertainty rather than artifacts of additional information or prompt variation. This approach directly addresses a limitation of prior evaluations that conflate evidence availability, prompting strategy, and task difficulty.

From a system-level perspective, the two-stage workflow approximates realistic deployment scenarios in which LLMs function as decision-support components rather than autonomous agents. The staged structure enables explicit analysis of where automation remains reliable, where uncertainty escalates, and where governance mechanisms—such as human oversight and escalation rules—must be introduced to maintain decision accountability.

3.2. Corpus and Gold-Standard Labels

The evaluation corpus consists of peer-reviewed journal articles related to wearable- and sensor-based health prediction, monitoring, and data-driven modeling. Records were retrieved using structured keyword combinations linking wearable or sensor technologies with prediction, risk assessment, behavioral monitoring, and related analytical concepts. After retrieval, standard deduplication procedures were applied, and only English-language publications were retained.

To establish a robust reference standard, gold-standard labels were generated through a multi-expert annotation process consistent with best practices in systematic review methodology. Two domain experts independently annotated all records at both the screening and eligibility stages. For screening, annotators evaluated records based solely on title-and-abstract information using broad inclusion and exclusion criteria designed to reflect early-stage relevance judgments.

Eligibility assessment employed the same evidence but applied a more detailed and restrictive set of criteria. Rather than issuing a single binary verdict, annotators evaluated each criterion separately, producing a structured representation of the decision process. This criterion-level annotation supports transparency and enables adjudication grounded in explicit reasoning rather than post hoc justification.

Disagreements between the two primary annotators were resolved by a third expert who reviewed the criterion-level assessments and adjudicated final labels. This procedure not only enhances label reliability but also preserves information about borderline cases, which is essential for analyzing disagreement as a governance-relevant signal rather than mere annotation noise.

3.3. Models and Prompting Setup

Three widely used large language models were evaluated under a strictly controlled prompting protocol: OpenAI GPT-5-nano (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA), Google Gemini 2.5-flash (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA), and Perplexity Sonar (Perplexity AI, San Francisco, CA, USA). The models were selected not to identify a superior architecture, but to examine whether governance-relevant patterns—such as stage-specific performance degradation and disagreement—persist across heterogeneous model configurations. GPT-5-nano and Gemini 2.5-flash were chosen as lightweight, efficiency-oriented variants from two major proprietary model families, reflecting typical defaults in applied experimentation and system prototyping [19]. Perplexity Sonar was included as a contrasting retrieval-augmented configuration that integrates live search rather than relying exclusively on parametric knowledge.

All models received identical inputs and instructions. For each record, the input consisted solely of the title and abstract, accompanied by a structured prompt that specified the task (screening or eligibility), the relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a constrained output format requiring a binary include or exclude decision. No additional contextual information, external metadata, or task-specific tuning was provided.

All evaluations were conducted in a zero-shot setting, and each record was processed independently to avoid cross-record contamination or memory effects. Prompts and raw model outputs were logged in full to support reproducibility and post hoc analysis. By fixing the criteria, evidence, and prompt structure across all models, the experimental configuration isolates differences attributable to model architecture and retrieval capability rather than procedural variation.

From a system-design standpoint, this setup approximates realistic deployment conditions in which LLMs are integrated as interchangeable components within a decision-support pipeline. The comparison between base and retrieval-augmented architectures under identical task definitions allows for controlled analysis of whether access to external information alters classification behavior when evidence constraints are otherwise fixed.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

Model behavior was evaluated using two complementary families of metrics: (i) inter-model agreement measures and (ii) alignment metrics relative to expert reference labels. This dual perspective reflects the system-level objective of the study, which is not only to assess how accurately individual models reproduce expert decisions, but also to examine the stability and consistency of decisions across models operating under identical criteria and evidence constraints.

Inter-model agreement metrics capture the extent to which different LLMs arrive at the same inclusion or exclusion decisions when provided with the same inputs and task definitions. For each pair of models, the proportion of observed agreement was computed, along with Cohen’s κ, which adjusts for chance agreement based on marginal label distributions:

where denotes the expected agreement under independent label assignments. Cohen’s κ is particularly suitable in this context because it accounts for imbalanced class distributions and provides a conservative estimate of agreement beyond raw concordance. These agreement measures enable assessment of whether models exhibit convergent decision behavior or diverge systematically, an issue that is central to interpreting disagreement as either noise or a meaningful signal of uncertainty.

To evaluate how closely each model’s decisions align with the expert-derived reference standard, standard binary classification metrics were computed. Let TP, FP, TN, and FN denote true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, respectively. Based on these quantities, precision, recall, F1 score, and specificity were calculated as follows:

Precision reflects the proportion of model-included records that are also included by experts, while recall captures the model’s ability to identify expert-included records. The F1 score provides a balanced summary of these two dimensions, and specificity quantifies the correct exclusion of records deemed irrelevant by experts. Together, these metrics characterize trade-offs between sensitivity and selectivity that are particularly salient in literature review workflows. All metrics were computed separately for the screening and eligibility stages to avoid conflating performance across tasks with distinct objectives and decision thresholds. This stage-specific reporting aligns with prior calls to move beyond single aggregate metrics and to explicitly account for task granularity in the evaluation of AI-assisted decision systems. All analyses were implemented in Python 3.13 using standard scientific computing libraries, ensuring transparency and reproducibility of the evaluation process.

Beyond conventional alignment metrics, the present study introduces three operational indicators to quantify epistemic and model-induced uncertainty in LLM-assisted review workflows. First, the Inter-Model Disagreement Rate (IMDR) captures the proportion of records for which different LLMs produce conflicting include/exclude decisions. Higher IMDR values indicate increased epistemic uncertainty at that stage. Second, a Confidence Proxy Score (CPS) is computed based on the internal consistency of each model’s output (e.g., the stability of reasoning patterns and response completeness). This serves as a lightweight reliability signal without requiring model calibration. Third, a Logical Consistency Check (LCC) evaluates whether the model’s decision aligns coherently with the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria embedded in the prompt. Records failing the LCC are flagged as high-risk and automatically routed for human review. Together, these indicators allow the workflow to operationalize uncertainty not as an abstract concept but as a measurable signal that guides adaptive human oversight across review stages.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the proposed governance signals (IMDR, CPS, and LCC) are embedded within the multi-stage review workflow. IMDR and CPS operate during the screening stage to quantify epistemic and model-induced uncertainty, while LCC is applied at the eligibility stage as a structural validity checkpoint that triggers mandatory human adjudication when eligibility criteria cannot be reliably inferred from abstract-level evidence.

4. Results

4.1. Inter-Model Agreement

Table 1 summarizes pairwise agreement and Cohen’s κ coefficients among the three evaluated models. Agreement is consistently highest during the screening stage, where pairwise observed-agreement percentages range from 82 to 92 percent. The associated κ coefficients (0.65–0.85) fall within the substantial-agreement range of conventional interpretive guidelines, confirming that, despite architectural differences, all three systems applied remarkably similar inclusion/exclusion boundaries when operating under broad conceptual criteria. The high degree of concordance suggests that coarse-grained relevance judgments rely predominantly on shared statistical priors embedded within general LLM training data, rather than unique domain representations.

Table 1.

Inter-model agreement for screening and eligibility decisions.

In contrast, agreement decreases noticeably during the eligibility stage. For this more stringent decision level, observed pairwise agreement drops into the 76–81 percent range, while κ falls to 0.52–0.62—moderate at best. The most prominent decline occurs for the OpenAI–Gemini pair, where κ decreases from 0.847 (screening) to 0.624 (eligibility). Similarly, the OpenAI–Perplexity comparison yields κ values of 0.707 (screening) and 0.518 (eligibility), while the Gemini–Perplexity pair shows the lowest absolute agreement across stages (κ = 0.653 and 0.527).

These consistent downward trends reinforce the notion that as decision criteria become more narrowly specified and multi-dimensional, architectural or training-data differences among LLMs are amplified. In eligibility assessment, subtle interpretive disparities—for instance, how models weigh methodological relevance or population specificity—translate into divergent labeling decisions. The eligibility task thus acts as a magnifier of intrinsic variability, revealing where instruction-following generalizes well and where context inference remains brittle.

Importantly, the high screening-stage κ values affirm that under well-defined broad prompts, even lightweight configurations yield relatively stable cross-model behavior. This supports the earlier methodological claim that prompt structuring and clarity are sufficient to harmonize model judgments for high-recall triage scenarios. Conversely, the eligibility results indicate that identical prompt templates are insufficient to fully align reasoning trajectories once subtler inferential elements, such as implied methodological fit, become determinative.

The observed differences in Cohen’s κ across review stages are not merely descriptive but directly inform the governance implications of the study. In screening, κ values above 0.70 indicate that model decisions indicate substantial consistency with expert judgments under the present setup and may support high-recall triage with bounded oversight, depending on the review’s risk tolerance. By contrast, the decline of κ below 0.60 in the eligibility stage signals a transition from reliable automation to decision contexts requiring human adjudication. These stage-specific variations demonstrate that agreement is not only a performance metric but also a governance boundary that determines when automated decisions remain acceptable and when they must be escalated for expert review.

4.2. Alignment with Expert Labels

The comparative analysis against expert annotations provides a complementary perspective on model accuracy and bias across LLMs. Table 2 reports precision, recall, F1 score, and specificity for each model and review stage. Overall, the results support the stage-dependent pattern outlined in Section 3, showing strong alignment with expert judgments during screening and a pronounced decline during eligibility assessment.

Table 2.

Screening performance across LLM models.

During the screening stage, all evaluated systems exhibit robust agreement with human reviewers. Precision ranges from 0.83 to 0.91, recall from 0.79 to 0.87, and F1 scores from 0.81 to 0.89, while specificity remains consistently high (0.89–0.93). These results indicate effective filtering of clearly irrelevant records and reliable identification of relevant literature. Among the models, OpenAI GPT-5-nano achieves the highest screening F1 (0.89), followed closely by Gemini 2.5-flash (0.86), with Perplexity Sonar showing slightly lower F1 but comparable recall, likely reflecting its retrieval-augmented inference.

Under broad inclusion criteria, all models approximate expert-level screening decisions with minimal systematic bias. High recall values (≥0.80) suggest a conservative inclusion tendency that prioritizes sensitivity over precision, a desirable characteristic for early-stage triage aimed at minimizing false negatives. The close clustering of screening F1 scores across architectures further corroborates prior findings that diverse foundation models can achieve near-human performance in automated relevance filtering when prompts and criteria are consistently specified.

In contrast, performance deteriorates substantially at the eligibility stage, where decision granularity increases, and abstract-level evidence becomes insufficient for resolving multi-criterion distinctions. Across models, F1 scores fall to 0.58–0.65, accompanied by reduced precision (0.50–0.56) and specificity (0.52–0.58). Despite these declines, recall remains moderate (0.69–0.78), indicating that models continue to favor inclusion even when stricter eligibility criteria are applied. OpenAI GPT-5-nano and Gemini 2.5-flash exhibit comparable proportional reductions in F1, while Perplexity Sonar maintains slightly higher recall but does not compensate for lower precision, consistent with prior observations that LLMs struggle when eligibility depends on sparse or implicit contextual information.

Aggregated across models, the results reveal a consistent divergence between screening and eligibility performance, with high mean screening accuracy (F1 = 0.85) and moderate eligibility accuracy (F1 = 0.62). Taken together with agreement results, this divergence demonstrates that both model-to-model and model-to-expert coherence decrease as decision stakes increase. These findings empirically justify a governance strategy in which automation is concentrated at low-risk screening stages, while eligibility decisions are subject to explicit human oversight triggered by elevated disagreement and reduced alignment with expert judgment.

Taken together, these stage-dependent performance and agreement patterns highlight a clear boundary for the deployment of LLM-assisted review systems. The consistently higher agreement and accuracy observed during screening suggest that automation can be applied at early stages with bounded risk. In contrast, the decline in both alignment and inter-model consistency at the eligibility stage underscores the need for explicit human oversight and escalation. These results therefore support the adoption of stage-aware governance strategies that allocate automation and expert review differentially across screening and eligibility decisions. This staged differentiation provides an empirically grounded foundation for designing hybrid human–AI decision architectures that optimize both efficiency and reliability in systematic review workflows.

5. Discussions

The present study demonstrates that large language models exhibit clearly stage-aware behavior when embedded in a two-stage literature review workflow based on title-and-abstract evidence, with direct implications for the governance of AI-assisted decision systems. During the screening stage, all evaluated models achieved high precision, specificity, and substantial inter-model agreement, indicating that when relevance judgments rely on broad topical signals, heterogeneous LLM architectures tend to converge on similar decision boundaries. From a governance perspective, this convergence identifies early-stage screening as a low-criticality decision environment in which automation can be deployed with bounded risk, provided that responsibility for downstream inclusion decisions remains explicitly assigned to human reviewers.

In contrast, performance declined markedly at the eligibility stage despite identical textual inputs and prompt structures. The transition from screening to eligibility introduces stricter, multi-criterion requirements that depend on methodological and contextual details often underspecified in abstracts. As a result, both alignment with expert labels and inter-model agreement deteriorated. Disagreements clustered in underspecified records rather than clearly irrelevant ones, such as studies describing sensor-based monitoring without explicit prediction targets or analytic outcomes. This pattern is governance-relevant because eligibility decisions are typically high-consequence and weakly reversible, making error tolerance substantially lower than at the screening stage.

Importantly, reduced agreement at the eligibility stage should not be interpreted solely as a limitation of LLM capabilities. Instead, the observed divergence constitutes a structured and interpretable signal of epistemic uncertainty. Because disagreement concentrates in borderline cases that also challenge human reviewers, inter-model disagreement can be operationalized as an explicit escalation trigger, specifying when automated decisions must be deferred to human adjudication rather than executed autonomously. In governance terms, disagreement thus functions as a decision-control mechanism rather than a performance artifact.

Building on this insight, we now clarify how such disagreement can be translated into operational oversight rules. For example, a staged workflow may define an expected range of agreement for each decision stage based on historical model performance. When the observed disagreement among models exceeds this range, the record is automatically escalated for expert review. Conversely, when agreement falls within this expected band, the system can proceed with limited or sampled human oversight. This structure does not impose fixed numerical cutoffs, but it demonstrates how disagreement can serve as a dynamic and auditable governance threshold embedded within the review process.

To translate stage-aware governance into operational practice, the study defines a set of procedural oversight rules that allocate human review based on observed agreement and disagreement signals. During the screening stage, where models exhibit substantial alignment with expert decisions, automation may proceed without intervention when inter-model agreement exceeds a predefined threshold. When disagreement rises above this threshold, records are escalated for human adjudication. At the eligibility stage, which demonstrates consistently lower agreement and higher epistemic uncertainty, all borderline or conflicting cases are automatically routed for expert review. This escalation logic ensures that human oversight is concentrated where decision stakes and ambiguity are greatest, thereby preserving both efficiency and accountability within hybrid human–AI workflows. In addition, future implementations of this framework may approximate these thresholds using pilot calibration studies or adaptive audit sampling, ensuring that escalation decisions remain empirically grounded rather than arbitrary.

These findings connect directly to prior work on uncertainty transparency and human–AI collaboration, which emphasizes that users benefit when uncertainty is communicated through interpretable cues rather than opaque confidence scores [20]. In this context, cross-model disagreement offers a system-level uncertainty indicator that does not depend on internal confidence calibration. The present results extend this literature by showing that independently deployed models can collectively surface uncertainty even when individual systems provide only binary outputs, thereby enabling governance mechanisms that are both lightweight and model-agnostic.

Beyond uncertainty signaling, the study underscores the role of reproducible evaluation and controlled system configuration as prerequisites for accountable AI deployment. By enforcing identical criteria, prompt structures, and output formats across models, the analysis isolates intrinsic behavioral variation from procedural noise. Comprehensive logging of prompts and outputs further enables auditability, post hoc review, and responsibility tracing, which are essential components of governance in decision-support systems rather than optional methodological refinements.

From a theoretical standpoint, the findings contribute to three complementary streams of research. First, they reinforce human–AI collaboration theories by demonstrating that effective integration depends on task-specific delegation boundaries rather than uniform automation [2,21]. Second, they align with information science perspectives on decision complexity, showing how information incompleteness at the abstract level structurally elevates uncertainty for both humans and models. Third, from a cognitive offloading perspective, the results caution against indiscriminate reliance on LLMs in high-stakes eligibility decisions and instead support explicit governance rules that delimit where automation ends and human responsibility begins [22].

Taken together, the findings support a governance-oriented division of labor in which LLMs reliably accelerate early-stage screening, while disagreement-informed escalation channels human effort toward ambiguous eligibility decisions. Rather than replacing expert judgment, LLMs function as configurable components within a socio-technical decision system whose effectiveness depends on how uncertainty is surfaced, how escalation thresholds are defined, and how accountability is assigned across stages.

The observed differences across models may also reflect differences in their underlying architectural and training design choices [23]. GPT-5-nano and Gemini 2.5-flash appear to be consistent with speed and broad generalization, which is consistent with their strong alignment and convergence during the screening stage. However, such configurations may yield weaker contextual inference and lower agreement during the eligibility stage, where methodological nuance becomes critical. By contrast, Perplexity Sonar exhibits higher sensitivity to borderline cases, which may increase recall while also introducing greater variability in eligibility judgments. These distinctions imply that governance should be model-sensitive: models that perform consistently under low-criticality screening can be prioritized for high-throughput automation, whereas models that surface greater variability in eligibility decisions warrant stricter human verification at later decision stages to manage inclusion risk and potential bias amplification.

The framework also clarifies how specific risks identified in LLM-assisted review—such as hallucination, bias propagation, and over-reliance on automated outputs—can be mitigated through stage-specific governance controls. Hallucination risk is managed by requiring cross-model agreement or human adjudication in high-uncertainty eligibility decisions. Bias propagation is constrained through standardized prompts and mandatory human review when disagreement exceeds pre-specified thresholds [24]. Over-reliance is addressed by preserving human accountability for consequential inclusion decisions and by routing borderline cases to expert adjudication rather than accepting automated outputs by default. This explicit risk-to-control mapping strengthens the coherence and operational clarity of the stage-aware governance model.

Finally, several avenues for future research follow this work. Future studies should examine whether stage-dependent patterns generalize beyond wearable-based health prediction to domains with different evidence structures. Incorporating full-text inputs, structured rationales, or evidence highlighting may reduce ambiguity in eligibility assessment. Most importantly, future research should formalize disagreement thresholds and escalation rules—such as audit rates, sampling strategies, or responsibility checkpoints—to translate uncertainty-aware governance from principle into operational practice.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study examined the governance implications of deploying large language models within a controlled, two-stage literature review workflow based exclusively on title-and-abstract evidence. By holding inclusion criteria, prompt templates, and evidence inputs constant across models, the analysis isolated behavioral differences attributable to decision stage rather than procedural variation. The results demonstrate a clear stage-dependent pattern: LLMs exhibit strong alignment with expert judgments and substantial inter-model agreement during initial screening, but both accuracy and agreement decline when stricter eligibility assessments are required. This divergence does not merely reflect performance degradation but delineates a structural governance boundary for AI-assisted decision-making systems. Our framework extends responsible AI and human-in-the-loop governance by embedding measurable, stage-specific escalation rules into LLM-assisted literature review workflows.

From a system design and governance perspective, these findings underscore the value of stage-aware deployment strategies. Screening tasks, which rely primarily on broad topical relevance, constitute relatively low-criticality decision contexts in which LLM-based automation can be deployed with bounded risk. Eligibility assessment, by contrast, exposes systematic limitations arising from information sparsity and interpretive ambiguity. Crucially, the observed decline in agreement at later stages marks the point at which automated decision authority should be withdrawn and responsibility explicitly reassigned to human experts. Recognizing and operationalizing this boundary is central to accountable AI deployment in evidence synthesis workflows.

A key practical implication of this work is the identification of inter-model disagreement as an interpretable and actionable governance signal. Because disagreement concentrates on borderline cases that also challenge human reviewers, it provides a principled escalation criterion for routing decisions to expert review without reliance on opaque or poorly calibrated confidence scores. In this sense, disagreement functions not as an error metric but as a control variable within a governance framework. Such disagreement-aware triage supports a transparent division of labor in which LLMs manage high-volume screening, while human reviewers focus on decisions where uncertainty and consequences are highest [25].

Beyond immediate workflow implications, the study contributes to broader theoretical understanding of human–AI collaboration in multi-stage decision environments. The findings illustrate how task granularity systematically shapes the relative contribution of automated systems and human expertise: LLMs perform reliably when decision rules are coarse, and evidence signals are strong but struggle as tasks demand nuanced interpretation under incomplete information. These results reinforce the view that effective AI assistance depends less on universal performance gains than on explicit governance structures that regulate when, where, and how automation is applied [26].

The study also highlights reproducible evaluation practices as a foundational requirement for trustworthy AI systems. Consistent eligibility criteria, standardized prompt templates, version-controlled inputs, and comprehensive logging enable clear separation between intrinsic model behavior and procedural artifacts. Without such audit-ready infrastructures, claims of improved AI performance cannot be meaningfully translated into governance decisions or accountability assignments.

Several limitations and avenues for future research warrant consideration. First, the analysis focuses on title-and-abstract evidence, which reflects common early-stage review practice but constrains eligibility reasoning. Second, the corpus is limited to wearable-based health prediction research, and generalization to other domains should be examined. Third, while inter-model disagreement proved informative, future work must formalize escalation thresholds, audit rates, and responsibility checkpoints to transform uncertainty signals into fully operational governance rules. In addition, a future extension of this work will include a structured scenario or simulation-based analysis to quantitatively examine how stage-aware governance affects decision outcomes compared with uniform oversight strategies. Such analysis would further validate the practical benefits of allocating automation and human review differentially across screening and eligibility stages.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that large language models are most effective when embedded within transparent, stage-aware governance frameworks that explicitly encode uncertainty, delegation boundaries, and accountability. Rather than positioning LLMs as autonomous decision-makers, the findings define their role as configurable components within socio-technical evidence synthesis systems, where scalability is achieved through automation and reliability is preserved through structured human oversight and reproducible evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.; Software, H.S.; Data curation, H.S.; Writing—original draft, H.S.; Writing—review & editing, J.K.; Supervision, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under the metaverse support program to nurture the best talents (IITP-2024-RS-2023-00256615) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Taeihagh, A. Governance of Generative AI. Policy Soc. 2025, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Modeling Generative AI and Social Entrepreneurial Searches: A Contextualized Optimal Stopping Approach. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Chen, H.; Juefei-Xu, F.; Ma, L. Look Before You Leap: An Exploratory Study of Uncertainty Analysis for Large Language Models. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2025, 51, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oami, T.; Okada, Y.; Nakada, T. Performance of a Large Language Model in Screening Citations. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2420496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, J. How industry recipe and boundary belief influence similar modular business model innovations. J. Open Innov. 2023, 9, e100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, P.; Jungmann, F.; Holland, R.; Bhagat, K.; Hubrecht, I.; Knauer, M.; Vielhauer, J.; Makowski, M.; Braren, R.; Kaissis, G.; et al. Evaluation and Mitigation of the Limitations of Large Language Models in Clinical Decision-Making. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2613–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.G.; Fütterer, T.; Gfrörer, T.; Lavelle-Hill, R.; Murayama, K.; König, L.; Scherer, R. Screening Smarter, Not Harder: A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Screening Algorithms and Heuristic Stopping Criteria for Systematic Reviews in Educational Research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 36, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.; Gartlehner, G.; Yaacoub, S.; Boutron, I.; Schwingshackl, L.; Stadelmaier, J.; Ravaud, P. Sensitivity and Specificity of Using GPT-3.5 Turbo Models for Title and Abstract Screening in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Ann. Intern. Med. 2024, 177, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorlund, K.; Lloyd-Price, L.; Jafar, R.; Nourizade, M.; Burbridge, C.; Hudgens, S. Screening Oncology Articles in a Qualitative Literature Review Using Large Language Models: A Comparison of GPT-4 versus Fine-Tuned Open Source Models Using Expert-Annotated Data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e23196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Sang, J.; Arora, R.; Chen, D.; Kloosterman, R.; Cecere, M.; Bobrovitz, N. Development of Prompt Templates for Large Language Model–Driven Screening in Systematic Reviews. Ann. Intern. Med. 2025, 178, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.; Ho, S.X.; Oo, S.V.F.; Chua, S.L.; Zaw, M.W.W.; Tan, D.S.W. Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models for Clinical Trial Screening. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e13611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.R. Prompting Considered Harmful. Commun. ACM 2024, 67, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfner, F.J.; Jürgensen, L.; Donle, L.; Mohamad, F.A.; Bodenmann, T.R.; Cleveland, M.C.; Bridge, C.P. Is Open-Source There Yet? A Comparative Study on Commercial and Open-Source LLMs in Their Ability to Label Chest X-Ray Reports. Radiology 2024, 313, e241139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. Academic Library with Generative AI: From Passive Information Providers to Proactive Knowledge Facilitators. Publications 2025, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, D.; Ali, S.J.; Dinev, G.M. AI-Enhanced Hybrid Decision Management. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2023, 65, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvert, R. Incentivizing Reproducibility. Commun. ACM 2016, 59, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, M.; Almaatouq, A.; Malone, T.W. When Combinations of Humans and AI Are Useful: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, V.; Almeida, J.M.; Meira, W. The Role of Computer Science in Responsible AI Governance. IEEE Internet Comput. 2024, 28, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Du, J.; Hu, Y.; Keloth, V.; Peng, X.; Raja, K.; Zhang, R.; Lu, Z.; Xu, H. Benchmarking Large Language Models for Biomedical Natural Language Processing Applications and Recommendations. Nat. Commun. 2023, 16, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, J.; Böcking, L.; Spitzer, P.; Kühl, N.; Vössing, M.; Satzger, G. Balancing the Unknown: Exploring Human Reliance on AI Advice under Aleatoric and Epistemic Uncertainty. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2025, 32, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toufiq, M.; Rinchai, D.; Bettacchioli, E.; Kabeer, B.S.A.; Khan, T.; Subba, B.; Chaussabel, D. Harnessing Large Language Models for Candidate Gene Prioritization and Selection. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M. Responsible Governance of Generative AI: Conceptualizing GenAI as Complex Adaptive Systems. Policy Soc. 2025, 44, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, M.; Hawamdeh, S. Debunk Lists as External Knowledge Structures for Health Misinformation Detection with Generative AI. Systems 2025, 13, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkenberg, A.; Hochman, G. It’s Scary to Use It, It’s Scary to Refuse It: The Psychological Dimensions of AI Adoption—Anxiety, Motives, and Dependency. Systems 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, G.; Skamnia, E.; Economou, P. AI-Assisted Literature Review: Integrating Visualization and Geometric Features for Insightful Analysis. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 15, e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vössing, M.; Kühl, N.; Lind, M.; Satzger, G. Designing Transparency for Effective Human-AI Collaboration. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 877–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.