Abstract

Intelligent systems draw much of their reliability from the quality of their ontologies; however, manual ontology assessment remains patchy, time-consuming, and difficult to scale. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a domain-independent, machine-learning-driven framework for ontology quality assessment and improvement in the Semantic Web. The framework combines structural, semantic, and documentation metrics with supervised learning models to predict quality issues and recommend targeted refinements through a four-phase workflow comprising ML model development, metric definition, automated improvement, and empirical evaluation. The approach is validated on educational knowledge graphs using 1500 ontology modules from the EDUKG repository, including a 100-module expert-annotated gold set (κ = 0.82). Experimental results show structural precision of 93.5% and semantic precision of 90.2%, with overall F1-scores close to 90%, while reducing ontology development time by 42% and quality assessment time by 65%. These findings demonstrate that coupling ML with structured quality metrics substantially enhances ontology reliability while preserving pedagogical and operational relevance in educational settings. Although empirical validation is conducted in the education domain, the modular and ontology-agnostic architecture can be adapted to other knowledge-intensive domains through retraining and domain-specific calibration, offering a reproducible foundation for continuous ontology quality improvement in Semantic Web applications.

1. Introduction

Ontologies lie at the heart of the Semantic Web, organizing knowledge, defining semantic relations among entities, and enabling intelligent retrieval and interoperability [1]. Because ontologies set the ground rules for meaning, the reliability of Semantic Web applications depends directly on their quality. Maintaining ontologies at a high level of quality is far from straightforward. Even small inaccuracies, inconsistencies, or inefficiencies can undermine reasoning processes, disrupt interoperability, and degrade overall system performance. Ontologies cannot be static; they must be updated and extended over time to remain coherent and scalable. Otherwise, growing data complexity and heterogeneity quickly make them less useful in practice [2].

Manual reviews and rigid rule-based checks do not age well in modern ontology-driven systems. They are difficult to keep consistent, hard to scale, and slow to adapt to fast-changing environments. Most quality-assessment tools are also tied to a single domain and therefore rarely transfer cleanly to mixed settings such as healthcare, e-government, or education. In this context, machine learning (ML) offers a different route. Beyond quality scoring, ML can detect anomalies, identify recurring quality patterns, and guide engineers toward practical optimization choices. When ML is embedded in structured quality-assessment frameworks, it also supports dynamic validation, adaptive learning, and ongoing refinement across varied ontology ecosystems. Together, these properties make quality control less brittle and less dependent on constant human supervision, helping ontologies remain reliable, well structured, and aligned with the semantic needs of their domains.

Yet everyday ontology evaluation still struggles once scale increases and context becomes richer. Manual review lies at one end of the spectrum: it is precise but slow and costly, and every check consumes scarce expert attention. At the opposite end stand fully automated procedures, which scale efficiently but often flatten domain nuances and overlook contextual or pedagogical intent. This tension is particularly pronounced in education, where technical soundness is necessary but not sufficient. Educational ontologies must not only be logically consistent but also organize knowledge coherently, support learners, and reflect concrete curricular and instructional goals.

Addressing these limitations calls for a different mix of methods. Any such approach must be technically rigorous, independent of a single ontology formalism, and flexible enough to operate across diverse data sources and deployment settings. Rather than stopping at structural checks alone, we combine machine-learning inference with a curated set of explicit quality indicators. As a result, validation becomes more dependable, more sensitive to context, and better able to feed back into gradual, step-by-step improvement. In this setting, ontologies are assessed not only for formal consistency but also for how well they fit their intended use context and how easily they can be reused across applications and, where appropriate, across domains.

To address these challenges, we propose a multi-phase framework that is not tied to a specific ontology formalism. It couples machine-learning models with explicit quality metrics to improve ontology quality while keeping evaluation efficient and grounded in real use cases. The framework is empirically validated on educational knowledge graphs, where ontologies are represented as modular subgraphs (hereafter referred to as ontology modules), each capturing a coherent subset of classes, properties, and relations within a given educational program or context. Although the experimental validation is conducted in the education domain, the framework is designed with a modular architecture and learning-based components so that it can, in principle, be adapted to other knowledge-intensive domains through retraining and metric recalibration.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the Semantic Web and situates ontologies within it. Section 3 reviews challenges in ontology quality assessment and related work. Section 4 presents the proposed methodology, and Section 5 reports the experimental evaluation and results. Section 6 discusses implications and limitations, and provides a comparative analysis with related approaches, Section 7 examines validity and cross-domain generalizability, and concludes the paper.

This work makes three main contributions. First, it introduces a structured, multi-phase framework that integrates machine-learning models with explicit, multi-dimensional quality metrics and can operate across different ontology formalisms. Second, it incorporates user-centered validation by involving teachers and domain experts, ensuring that automated recommendations are assessed not only for technical correctness but also for pedagogical relevance and practical usefulness in real educational settings. Third, it demonstrates measurable performance gains, shortening ontology development cycles, accelerating quality assessment, and improving operational efficiency. Together, these contributions strengthen both methodological rigor and practical impact and illustrate how AI-based support can help manage ontology quality at scale within the broader Semantic Web.

2. Background

2.1. Purpose and Technologies of the Semantic Web

The Semantic Web extends the familiar World Wide Web by structuring data so machines can interpret it, not just display it to humans. Rather than treating web pages as isolated documents, it encourages publishers to expose data in a way that software can combine, reuse, and reason over. As a result, information can flow across applications, organizations, and communities, supporting richer search, discovery, and knowledge building [3].

At the heart of this vision is a set of technologies standardized by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Among the core pieces is RDF, the Resource Description Framework, which represents facts as subject–predicate–object triples and offers a common format for data exchange and integration [4]. Building on RDF, OWL (Web Ontology Language) provides a way to define concepts and relationships in a domain so that machines can perform logical reasoning over them. To ask questions over this structured data, SPARQL serves as the query language that retrieves and manipulates RDF-based information. Every resource involved in this ecosystem is identified with a URI, allowing precise, unambiguous references and links across the Web [4].

The Semantic Web stack is rounded out by several additional W3C specifications, alongside the core standards. RDFS provides simple schema constructs, and SHACL lets us define and check constraints on RDF graphs. JSON-LD, in turn, makes it possible to write linked data in a JSON format that developers already know. When these pieces are combined with rule-based reasoning systems, they increase interoperability and make it much easier to represent and share complex knowledge on the Web [5].

The Semantic Web is widely regarded as a key means of organizing and managing knowledge in many areas [6,7]. Instead of leaving each system with its own isolated data format, it promotes shared standards and common vocabularies so that information from different sources can speak the same language. Once these standards are adopted, heterogeneous data sources can be brought together and analyzed side by side, allowing analysts to move deeper into the data and identify patterns and signals at a finer level of detail. In such an environment, search is no longer a simple matter of matching keywords. Once semantic annotations are in place, systems can align results more closely with the user’s intended meaning and discard much of the irrelevant material [8]. At the same time, relationships between concepts are written as structured links, giving machines a firmer basis for more advanced reasoning tasks.

From a technical angle, interoperability sits at the center of this ecosystem. After data has been cast into a machine-readable form, large portions of processing and analysis can be offloaded to automated routines, reducing manual effort and smoothing processing pipelines [9]. On the user-facing side, semantic technologies also reshape how systems craft and deliver their responses. They allow content and services to be tuned to user preferences and behavior, rather than offered in a one-size-fits-all way. Once diverse sources are aligned in a unified semantic layer, decision-makers in areas such as life sciences, education, and industry gain a more joined-up view, allowing decisions to be grounded in broader and more internally consistent evidence [10,11,12]. As data volume and complexity grow, informal structures quickly become untenable. Ontologies then provide the missing backbone: they give data an explicit form and simplify how it is organized, interpreted, and repurposed.

2.2. Role of Ontologies in the Semantic Web

In the Semantic Web, ontologies provide the schemata that organize and represent knowledge across domains. They define a shared vocabulary so that otherwise separate systems can exchange data without losing meaning. They are more than labels or taxonomies. As a semantic backbone, ontologies support reasoning, context-aware processing, and focused retrieval. For Zhu et al. [13], the key step is symbolic encoding: when human expertise is represented in this way, machines can perform more complex reasoning and interpret data at a deeper level. In that light, ontologies become a core piece of infrastructure for web systems that require both semantic depth and reliable interoperability.

What once appeared to be a theoretical concern now manifests in real-world systems: ontologies sit at the base of systems across a broad range of domains. When privacy and consent are at stake, ontologies spell out data-sharing rules in precise terms, reducing ambiguity and disagreement. One example is Gharib [14], who builds informed-consent models on top of an ontology so that each condition and permission is expressed in clear, tightly specified terms. Instead of relying on opaque text or ad hoc rules, the consent logic is captured in a form that both machines and humans can inspect.

From an educational perspective, ontologies take on another important role. Examining electrical engineering and informatics, Utama et al. [15] describe an ontology as a map that links the central ideas, concepts, and terms in a field. With that map in place, students and practitioners can navigate dense material more easily and see how topics relate to one another. Rather than facing a collection of disconnected notions, they gain a structured and coherent view of the discipline.

In clinical environments, ontologies reappear as integral components of diagnostic and care-related decision-making. When Massari et al. [16] incorporate ontology-based models into their systems, predictions of patient outcomes become more stable and more trustworthy. Jiwar and Othman [17] show how ontologies integrate scattered clinical details and contextual cues into a single, navigable structure. This integrated view helps physicians consider possible diagnoses and select appropriate treatments. As datasets grow larger and more complex, this integrative capacity becomes increasingly critical.

Across the public sector, ontologies often operate quietly in the background, supporting digital initiatives without drawing attention to themselves. In the context of e-government, Altahir [18] notes that different agencies may refer to the same concept using different terms. Once a shared ontology is introduced, agencies can align their vocabularies and converge on a common understanding of key concepts. Narayanasamy et al. [19], approaching the problem from another angle, show that ontologies sharpen communication between people and machines, improving transparency and efficiency in government systems.

From a technical standpoint, ontologies offer a clear advantage: they can be revised, reused, and integrated into other systems without requiring a complete redesign. Pileggi and Lamia [20] describe ontologies as scalable, formally defined artifacts that can be shared and interlinked across the Web to support semantic integration. Building on this idea, Al-Zebari et al. [21] and Raza et al. [22] report improvements in both retrieval accuracy and processing speed when data is organized around an ontology. In fast-moving sectors such as e-commerce, these gains are tangible, as users expect rapid and precise responses.

Information retrieval is one domain where ontologies make a particularly strong impact. Unlike traditional keyword-based engines that primarily match strings of words, ontology-driven systems can follow concepts, their meanings, and the relations between them. This typically yields results that align more closely with user intent and contextual meaning. Illustrating this point, Xu and Sun [23] employ core ontologies for semantic annotation in the Semantic Web of Things and report improved retrieval performance and richer contextual understanding in applications such as academic search and e-retail.

Many knowledge graphs, beyond search systems alone, are built on ontologies that define which entities exist and how they are linked. In these systems, the ontology often functions as a schema that shapes both nodes and edges within the graph. Huck [24] observes that such ontological frameworks also reinforce metadata practices and enable more advanced forms of reasoning in AI and ML. Together, these properties provide both structural clarity and inferential power, explaining why ontologies occupy a central position in modern knowledge-representation architectures.

Beyond the technical literature, ontologies have a visible impact across diverse disciplines. Rovetto et al. [25], writing in the context of space safety engineering, demonstrate how ontologies can be used to organize and share knowledge within that domain. Their work shows that cross-domain collaboration on ontologies does more than align vocabularies: it supports innovation, facilitates knowledge transfer, and enables good practices to move between communities. From this broader perspective, the value of ontologies lies not only in technical integration but also in their ability to foster shared understanding across fields.

At the center of the Semantic Web vision lies a straightforward yet powerful idea: a web that connects information across systems and treats it in a more informed and interconnected way. Within this vision, ontologies play a central role by providing both explicit structure and shared meaning. Once such an ontological layer is in place, machines are no longer limited to storing or rendering raw records; they can interpret represented knowledge and perform reasoning over it. In this sense, data becomes something that can be actively processed, not merely displayed.

Building on this foundation, a wide range of applications has emerged, from semantic search and clinical decision support to learning platforms, e-government services, and everyday AI tools. As Semantic Web technologies continue to mature, this ecosystem is likely to expand further. In this context, ontologies remain a critical foundation for systems that must scale, remain transparent, and adapt to evolving domain requirements over time.

2.3. Challenges and Quality Assessment in Ontologies

The Semantic Web is only as useful as the ontologies that underpin it. Maintaining those ontologies over years rather than months is demanding work. As data accumulates and usage patterns evolve, ontologies must adapt while avoiding uncontrolled growth into complex structures that are difficult to maintain. Developers therefore tend to make incremental, carefully considered edits: adding classes, refining relations, or pruning obsolete elements to preserve clarity, efficiency, and human interpretability. At the same time, ontologies are expected to interoperate with other systems, standards, and domains, allowing shared data to move smoothly while retaining consistent meaning.

For ontology engineers, internal consistency and factual accuracy are non-negotiable. When contradictions, missing links, or incorrect relations arise, systems may produce false inferences or unreliable answers [26]. Meanwhile, as knowledge bases expand with newly asserted facts, ontologies must incorporate these additions without losing coherent internal logic [27]. Manual verification of these properties is slow and error-prone, and the review process itself can introduce new mistakes. To address these issues, many researchers rely on automated techniques that assess ontology quality by detecting errors and redundancies and by applying established metrics to evaluate structural robustness and semantic soundness [28]. In high-stakes domains such as healthcare and AI, systematic quality assessment increases trust in ontologies and supports their practical deployment [29].

Machine learning introduces an additional mechanism for managing ontology quality. Rather than waiting for errors to manifest in downstream behavior, ML models can monitor how an ontology evolves and flag inconsistencies as they arise. In many cases, these systems not only identify problematic fragments but also suggest, or automatically apply, straightforward repairs, reducing routine manual effort. With such support, ontologies can remain flexible while preserving precision as domains evolve. For organizations that depend on data-driven systems, ML-based quality assessment improves confidence in the ontologies that underpin intelligent processing and knowledge-intensive applications. In this work, we build on these advances by integrating metric-based checks with ML models within a structured framework, enabling ontology quality to be monitored and improved in a more systematic and scalable manner.

3. Literature Review

As data sets grow larger and more tangled, keeping ontology quality high becomes increasingly difficult. To prevent these models from turning into rigid, outdated structures, developers and maintainers have to revisit, adjust, and clean them regularly so they stay useful. Designing a solid ontology, in turn, is demanding work because it requires deep knowledge of the domain and a clear sense of the real settings in which the model will be used.

In their work, Kollapally et al. [30] show that ontology enrichment with ML and large language models must account for contextual variation, including dialects and shifting language on social media. Because this context evolves over time, the technical task of adding new terms and relations is only part of the difficulty. No less important is the human effort required to agree on how concepts should be defined, grouped, and linked. Neuhaus and Hastings [31] take the argument further: for them, building an ontology is not merely a matter of encoding what is known, but also of negotiating consensus among stakeholders with divergent perspectives.

Merging ontologies from different domains is a substantial challenge in its own right. Horsch et al. [32] observe that separate teams often build their domain ontologies in isolation. These independently developed models can then clash or fail to align, making shared semantic standards difficult to establish. In biomedical research, this problem is particularly acute. New ontologies often need to be integrated into existing ones, complicating both data integration and downstream analysis [33]. Gkoutos et al. [34] trace this difficulty to the need to encode highly complex relationships over massive datasets, a combination that often leaves matching and alignment methods struggling to cope.

In rapidly changing data environments, keeping an ontology in good condition presents another challenge. Sassi et al. [2] stress that in such settings, adaptation and versioning move from being peripheral tasks to occupying a central role. Whenever new information arrives, the ontology is revised so that it reflects current knowledge, while its overall structure and purpose largely remain intact. Neuhaus and Hastings [31] point out that this continuous cycle of updates can place significant pressure on both staff and technical infrastructure, especially when multiple ontology versions must be maintained, compared, and migrated in parallel. As large-scale reasoning is applied to ontologies that continue to expand and evolve, their size and complexity increase rapidly [35], and inference tasks become progressively slower and harder to execute in operational settings [35].

Beyond these technical issues, language and culture introduce additional complications. Xue and Liu [36] note that ontologies developed in different linguistic or cultural contexts are difficult to reconcile, which in turn hinders data integration across diverse sources. As a result, language barriers often limit ontology reuse across regions and communities. To mitigate this problem, ontologies must incorporate sufficient flexibility to support adaptation to multiple languages and contexts rather than being tightly bound to a single setting.

3.1. Existing Approaches to Ontology Quality Improvement

Over recent years, efforts to improve ontology quality have evolved substantially. Early research focused primarily on detecting inconsistencies, redundant elements, and gaps in logical structure. Most techniques relied on rule-based systems and formal consistency checks, with constraints being manually specified to capture structural errors and verify relationships. These approaches were effective when ontologies were relatively small and stable. As ontologies and datasets grew larger and more dynamic, however, their reliance on manual effort made them increasingly difficult to scale.

As ontology projects matured, formal verification tools began to play a more prominent role. Description Logic (DL) reasoners such as Pellet and HermiT are commonly used to assess logical consistency. Rather than relying on ad hoc checks, these engines identify contradictions and analyze subsumption relationships between classes. Their main limitation is computational cost: performance degrades sharply as knowledge bases grow in size or change frequently. To reduce the burden on human editors, later approaches introduced automated validation schemes that combine logical reasoning with heuristic rules.

In many systems, heuristic rule sets are integrated with reasoning engines to restructure hierarchies, align classes and properties, and detect obvious anomalies. Because these rules are defined in advance, however, such systems often struggle to adapt to highly specialized domains or heterogeneous datasets.

More recent approaches draw on Natural Language Processing, statistical techniques, and data mining. Through text mining and concept extraction, candidate entities and relations can be derived from both structured sources and free text. Although these methods reduce routine manual effort, maintaining coherence across domains and scaling to large, rapidly evolving corpora remains challenging. Moreover, many of these approaches target isolated tasks such as concept learning or consistency checking, rather than providing an integrated pipeline for continuous ontology quality assessment.

3.2. ML-Based Approaches for Ontology Quality Improvement

In recent years, ML has become a central mechanism for addressing the limitations of traditional and semi-automated ontology quality approaches [37]. Earlier methods rely on fixed rule sets that quickly fall out of step with evolving knowledge structures, whereas ML models can adapt as data and domains change, thereby reducing the need for manual intervention [38,39]. This adaptive behavior makes ML-based assessment more responsive and better suited to dynamic, data-intensive environments. In practice, ML-driven pipelines offer advantages in scalability, automation, adaptability, and accuracy, enabling large and complex ontologies to be analyzed more efficiently than with manual or purely rule-based techniques.

In domains such as biomedical informatics, natural language processing, and data integration, ontology design and maintenance are increasingly shaped by ML techniques. Healthcare provides a concrete illustration: Massari et al. [16] present a decision tree–based ontology model for diabetes prediction that explicitly leverages structured domain knowledge. This work illustrates how Ontology-Driven Machine Learning (ODML) can improve predictive accuracy while maintaining interpretability for domain experts [40].

Beyond clinical prediction, ML has also been applied to ontology enrichment in tasks such as sentiment analysis and social media categorization. Kollapally et al. [30] note, however, that maintaining ontologies in these rapidly evolving contexts requires careful attention to domain-specific nuances. When logical concept analysis is incorporated, more abstract and general concepts can be identified, making ontologies easier to adapt and reuse across settings [41].

Across the ontology lifecycle, ML now plays a role in concept learning, inconsistency detection, ontology alignment, evolution, and quality assessment. NLP models such as BERT and Word2Vec support ontology learning by identifying semantic patterns in large text corpora, while classification and graph-based models help uncover missing links, redundancies, and contradictions. Embedding-based methods enable ontology alignment, and incremental or reinforcement-learning approaches facilitate continuous adaptation as domains evolve. For quality assessment, ML models estimate coherence, completeness, and task suitability, providing signals that guide ontology refinement in real applications.

Despite these advances, most ML-based solutions remain tailored to specific domains or tasks and are not easily reusable as general-purpose quality frameworks, particularly in educational settings. This limitation motivates the need for approaches that explicitly structure ML components, quality metrics, and human feedback into a reusable and ontology-agnostic pipeline.

3.3. Limitations and Open Challenges

This subsection reviews limitations and open challenges identified in existing ML-based ontology quality approaches and motivates the design choices of the proposed framework; it does not describe limitations specific to the present study.

Recent progress does not eliminate fundamental challenges associated with applying ML to ontology quality, including scalability, explainability, and responsible use. These challenges are especially pronounced in domains that involve sensitive data or affect individuals directly. A central issue concerns the nature of the data used to train ML models: what data are available, how representative they are, and in what condition they reach the model. In educational settings, this includes understanding which parts of datasets such as EDUKG are used, how ontology modules are sampled, and which assumptions underlie preprocessing and annotation.

Most ML methods assume the availability of large, well-structured training datasets. Their performance degrades when metadata are incomplete, relations are inconsistent, or input data are noisy. Under such conditions, models may learn spurious patterns, embed bias, and appear reliable only according to surface-level performance metrics. Addressing these risks requires careful preprocessing, well-defined sampling strategies, and validation protocols tailored to the domain. Although widely recommended, such practices are often only partially implemented in real deployments. Even when they are applied, models may still inherit biases present in the source data and expert annotations.

Interpretability presents another major obstacle. Deep learning models can achieve high predictive accuracy while obscuring the reasoning behind individual outputs. In domains such as healthcare, law, and public administration, this lack of transparency is particularly problematic because decisions must be explainable and contestable. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques can partially mitigate this issue by exposing aspects of model reasoning in human-interpretable form. Applied in this way, XAI supports auditing, governance, and trust in ontology-based systems. The importance of interpretability also emerged in educational contexts, where users frequently request clearer justifications for system-generated recommendations.

Computational efficiency remains a persistent concern. Models such as Graph Neural Networks and Transformer-based architectures demand substantial computational resources during both training and inference. In large or frequently updated ontology environments, this can hinder real-time deployment and increase operational costs. A more pragmatic strategy involves using lighter, more energy-efficient models that preserve acceptable accuracy while keeping runtimes predictable. Consequently, many practical systems rely on tree-based methods or compact neural networks to balance performance and efficiency.

Ontology alignment and semantic integration remain difficult even with advanced ML techniques. Terminology drift, varying levels of granularity, and evolving domain contexts introduce mismatches that fully automated methods struggle to resolve. Human-in-the-loop workflows therefore remain essential. By allowing algorithms to propose alignments and experts to validate or revise them, such workflows preserve intended semantics while improving interoperability. This hybrid pattern (combining automated inference with expert oversight) is widely recognized as a practical compromise in real deployments.

Ethical and fairness concerns further complicate ontology quality management. When models are trained on biased data, those biases can propagate into ontologies and be amplified over time. In fields such as public policy, healthcare, and education, such distortions have tangible consequences, shaping classifications, priorities, and access to services. Fairness-aware learning, transparent evaluation, and responsible data governance are therefore critical throughout the ontology lifecycle. Even in educational contexts, biased modeling of curricular structures or prerequisite relationships may disadvantage particular groups of learners.

Future research should avoid treating ML systems and domain experts as separate components. Instead, ontology quality pipelines should integrate human expertise and ML models in a mutually reinforcing manner, enabling practitioners to understand and influence system behavior. Greater attention is also needed for data curation, documentation, and long-term maintenance, as well as for ensuring interpretability under realistic computational constraints. The multi-phase framework proposed in this paper represents an initial step toward addressing these challenges by structuring the interaction between ML models, explicit metrics, and expert feedback.

Ethical safeguards should be embedded throughout the ontology lifecycle—from early modeling decisions to deployment and maintenance—rather than added retrospectively. Under these conditions, ML can support Semantic Web ontologies that are not only effective but also trustworthy and ethically defensible as domains evolve. Existing studies, however, rarely combine these safeguards with concrete quality metrics and systematic user-centered evaluation, particularly in education. The proposed framework seeks to address part of this gap by integrating ML-based assessment, explicit metrics, and expert feedback into a single, repeatable process.

4. Materials and Methods

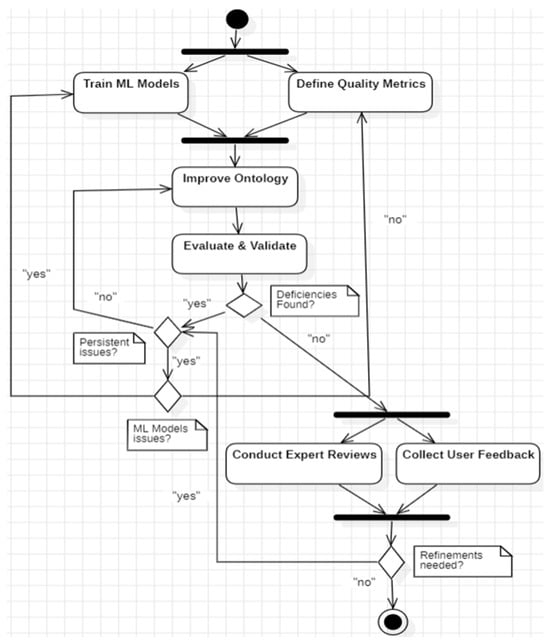

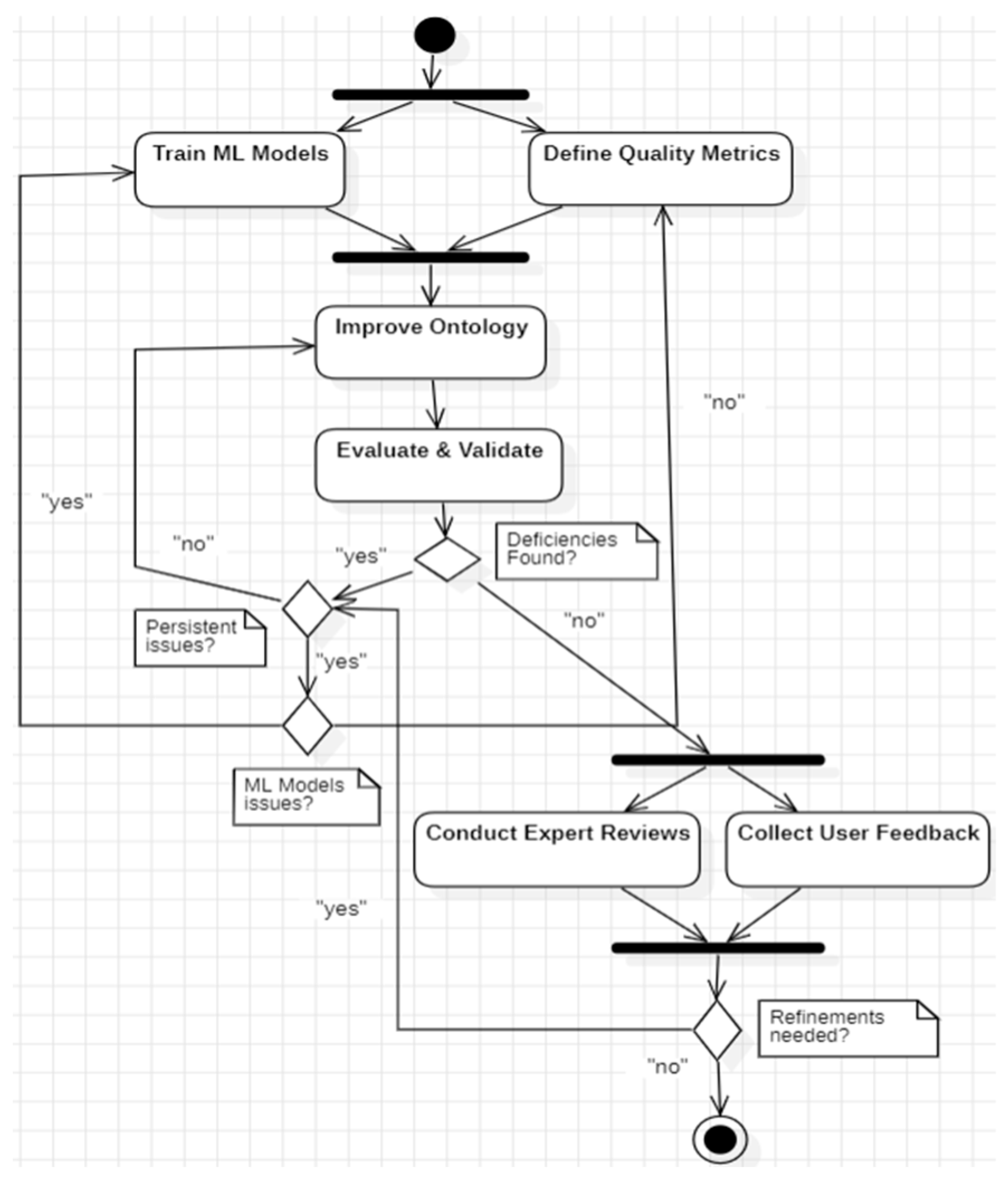

We propose a systematic, ontology-agnostic, multi-phase framework to improve ontology quality on the Semantic Web. At its core, the framework weaves together ML techniques and multi-dimensional quality metrics to offer a robust and scalable way to evaluate and enhance ontologies. With each pass, the reliability of the ontologies is gradually strengthened over time. The framework is organized into four phases (Figure 1). Methodologically, the work follows an applied, empirical design that combines quantitative evaluation of ML-based predictions with qualitative expert and user validation (as detailed in Section 5). In this paper, the four phases are instantiated and evaluated in an educational knowledge-graph setting, while being designed so they can be adapted to other ontology-based domains.

4.1. Phase 1: Development of ML Models for Quality Assessment

As a first step, we construct ML models that are designed to be domain-agnostic and tailored for ontology quality evaluation. Instead of targeting a specific discipline, the models analyze RDF/OWL ontologies through their shared features, structural regularities, and recurring quality markers. As a result, they can be reused across multiple domains with only limited reconfiguration, provided suitable training data are available. Each model focuses on generic signals: class-hierarchy depth, property usage, relationship density, and annotation completeness, capturing both structural soundness and documentation quality without relying on domain-specific semantics. In the EDUKG case study, these signals are extracted as feature vectors at the level of ontology modules and linked to expert judgements of quality (see Section 5). We implemented and compared several ML families, including deep neural networks, random forests, and gradient-boosting machines, and trained them to detect key quality facets, including hierarchical and structural consistency, completeness of entity and property relationships, annotation richness and clarity, and the integrity and connectivity of the overall organization.

Concretely, each model outputs a continuous score in [0,1] for every ontology module and for each quality dimension. In this study, these dimensions are aggregated into structural and semantic checks. Higher scores indicate a greater likelihood that a module requires revision. During evaluation, the scores are converted into binary decisions (“adequate” vs. “needs revision”) for the computation of precision, recall, and F1 (Section 5.2) and are also used to rank modules by their predicted need for attention.

Feature engineering prioritizes broadly transferable predictors so the models can be ported via retraining or transfer learning to new ontology corpora. As modular, reusable components, these ML models are easily fine-tuned for deployment across a wide range of ontology-driven domains. Hyperparameters and training procedures can be adapted to each target corpus, while the overall architecture of the models remains stable.

4.2. Phase 2: Quality Metrics Framework Development

In the second phase, a multi-dimensional set of domain-neutral quality metrics is introduced. Rather than relying only on classic ontology indicators, this scheme also brings in new measures derived from ML-based feature analysis. Taken together, these metrics allow for a broad, scalable, and interpretable assessment along four complementary dimensions. The relative weight of each dimension can be tuned so that the framework reflects the priorities of a particular deployment setting.

4.2.1. Structural Metrics: Organization and Hierarchy

To examine how concepts and relations are configured, we run three structural checks. First, class–subclass topology and overall graph connectivity are analyzed to assess balance and navigability and to identify dead ends or overly convoluted paths. Second, we examine the use and spread of properties by evaluating completeness and distribution across classes and interpreting what these patterns reveal about how relations function in the schema. Third, the graph is scanned for redundant or weakly connected components; where possible, these checks are supported by standard DL reasoners to ensure that logical defects are detected systematically.

4.2.2. Semantic Metrics: Logical Soundness and Conceptual Coherence

At this stage, we move away from pure structure and focus on meaning and logical soundness. We examine semantic consistency among related entities to guard against contradictory axioms; we identify missing, redundant, or conflicting property constraints that can yield brittle or ambiguous inferences; and we evaluate concept alignment and reasoning behavior by checking how consistently concepts match one another and whether the reasoner produces stable entailments across the ontology.

4.2.3. Documentation Metrics: Metadata Quality and Completeness

A clear description is essential if an ontology is to be reused, governed, and audited. With that goal in mind, we look at three aspects. We first check basic metadata by verifying that labels, comments, and key metadata fields are present and used consistently, since gaps or irregular patterns are often early warnings that documentation will be difficult to maintain. We then assess the usefulness of annotations by determining whether they help a human reader understand and curate the content, rather than merely rephrasing class names. Finally, we examine consistency across modules by comparing documentation style, terminology, and level of detail to ensure coherence rather than abrupt shifts between modules.

4.2.4. Usage Metrics: Applicability and Reusability

In day-to-day use, an ontology only proves its worth if it can leave its original context and still work elsewhere. To get a sense of that portability, we look at three aspects. We examine links to other resources by assessing how readily the ontology can be mapped to external ontologies and datasets, since stable links suggest readiness to join a wider ecosystem. We also consider behavior in real systems, using smooth interoperability across applications and platforms as evidence of standards compliance. Finally, we assess reuse in nearby workflows by testing whether parts of the ontology can be transferred into related workflows or domains without major redesign, using successful reuse as a concrete indicator of downstream value.

The framework does not depend on any specific ontology, and its metrics and their weights can be retuned to match the goals of a given domain. For example, higher diagnostic accuracy in healthcare, stronger interoperability in e-government, or greater process reliability in industrial systems. In the present work, the emphasis is on educational knowledge graphs, but the same metric families can be reweighted to reflect different domain priorities.

4.3. Phase 3: Automated Quality Improvement System

The third phase introduces an automated feedback loop that ties together the ML predictions from Phase 1 and the quality metrics from Phase 2. Rather than acting as a single check, this loop is intended to keep the ontology improving over time. It is implemented as four linked functions: analysis and detection, improvement, validation, and reporting. First, the ontology is scanned with the combined metrics to find inconsistencies, missing or incomplete links, and weak semantic relations. After these issues are identified, the system proposes fixes such as adjusting hierarchies, refining properties, or tightening specific relations. In low-risk cases, it can also apply some of these corrections automatically. In this work, “low-risk” refers to local, non-semantic changes (e.g., adding missing labels/comments, removing obvious redundancy, or repairing isolated structural defects) that do not alter core meaning or prerequisite logic, whereas “high-risk” refers to semantic or domain-impacting edits (e.g., modifying constraints, prerequisite relations, or class definitions) that require manual approval. Next, the proposed changes are checked to confirm that logical soundness, structural integrity, and semantic coherence are still intact, so that no new errors or semantic drift are introduced. Finally, the outcomes are summarized in dashboards and short reports that highlight detected issues, applied changes, and updated quality indicators.

The modules feed into one another as they run. They spot issues, suggest or apply fixes, check the results again, and record the changes. This loop steadily improves the ontology’s quality. Because the architecture is modular, each module can be lifted into a new domain. Just the ML models need to be retrained on fresh data, and the metrics adjusted to that context. Figure 1 makes explicit the decision points at which persistent issues or suspected model errors trigger upstream changes to the models or to the metric definitions.

4.4. Phase 4: Evaluation and Validation

The fourth phase is devoted to a wide evaluation of the method, covering both technical metrics and practical use. Here, the evaluation focuses on an educational ontology corpus, but the protocol itself is designed to be reusable in other domains. This step lines up results from multiple evaluation angles, providing empirical support for the framework and indicating how it might transfer to related settings.

4.4.1. Quantitative Evaluation

We start with a basic round of measurement and benchmarking. For both structural and semantic checks, we compute precision, recall, and F1. We also evaluate recommendation accuracy by examining whether suggested changes are correct and meaningful in context. Finally, we track runtime and resource usage across ontologies of varying size and complexity to assess performance and scalability, comparing repeated runs to verify stability.

4.4.2. Qualitative Evaluation

Numbers are not enough on their own, so we pair them with expert judgment and user feedback. Domain specialists review sample recommendations to judge realism and usefulness in everyday work. We then use case-based feedback to gauge user satisfaction and the likelihood of continued use. Participants also describe operational fit, including perceived transparency, ease of justification, and how smoothly the framework integrates with existing tools and processes.

All of this feeds into a continuous feedback loop. We use evaluation results to tweak both the ML models and the quality metrics, allowing the system to grow with its Semantic Web environment. Each new round of assessment teaches it more about its context and nudges its behavior toward sharper, more relevant performance.

Figure 1 summarizes the iterative ML-based workflow for ontology quality improvement. At the start of this workflow, two activities run in parallel: training the ML model (Phase 1) and defining the quality metrics (Phase 2). Once these two phases produce their results, they feed into an automatic improvement component (Phase 3) as well as an evaluation stage (Phase 4).

During evaluation, the system checks whether the ontology satisfies the defined quality criteria. When problems are observed, minor issues lead to direct ontology fixes within the improvement system (Phase 3), whereas major issues trigger upstream actions such as model retraining or adjustment of the metric definitions in Phases 1 or 2. Feedback from experts and end users is used in a continuous loop to gradually improve ontology quality. This iterative design helps the system scale, remain consistent, and adapt to different types of knowledge domains once their data and requirements have been encoded into the framework.

Figure 1.

A UML activity diagram illustrating the workflow for ML-driven ontology quality enhancement and cross-domain refinement.

Figure 1.

A UML activity diagram illustrating the workflow for ML-driven ontology quality enhancement and cross-domain refinement.

5. Results

To assess the framework, we combined quantitative metrics with a qualitative review and asked how far it actually improved ontology quality. We chose education as a concrete testbed and applied the framework to educational ontologies, although it is meant to be domain-independent. Educational ontologies come with deep hierarchies, dense semantic links, and uneven documentation, which makes them a demanding test of robustness and adaptability. Seen in this light, the study functions as a proof of concept. The findings support the idea that the general method outlined in Section 4 works in real-world conditions and can be deployed and evaluated in practice without being tied to any specific ontology. At the same time, all reported results should be read as evidence from a single domain rather than as definitive proof of cross-domain performance.

The evaluation pipeline unfolded in three stages. In the first stage, we focused on preprocessing and module generation: we cleaned the educational data, brought them into a common format, and encoded them as modular RDF/OWL ontologies. The second stage then used trained ML models to examine the ontologies from several angles, including structure, semantics, and documentation quality. Finally, the system generated feedback in the form of practical suggestions, such as reorganized course hierarchies, adjusted property definitions, and consistency checks.

Findings were delivered through dashboards and concise structured reports. Together, these gave educators and quality-assurance teams something solid to work from when interpreting the results and deciding what to address first. In this work, the setup is tuned to educational ontologies. The workflow itself, however, is not tied to that domain. It can be picked up in other ontology-driven contexts by retraining the ML models and tweaking the quality metrics. Subsequent deployments would follow the same evaluation logic but would require domain-specific calibration of thresholds and feature weights.

5.1. Experimental Setup and Dataset

EDUKG [42] is an RDF/OWL resource that models educational entities and their relations. In our setup, it provided the raw material for the ontology modules used to train and validate the ML models. Because EDUKG is not organized as a set of predefined ontologies, we first carved it into modular ones by extracting one-hop subgraphs around program-level instances (for example, GeneralBachelor, Cpge, Atc). Each subgraph was then serialized in OWL/RDF, preserving the classes, properties, and links that are relevant in its local context.

This process yielded 1500 ontology modules in total. These modules describe course hierarchies, prerequisite relations, and program overviews. To run the evaluation, we first selected 100 modules as a stratified sample from the larger pool. Stratification was performed to preserve diversity in program type and module complexity (approximated by size and relation density), with sampling being performed proportionally to the observed distribution in the full corpus. Two domain experts independently rated each module for consistency, completeness, and reusability. Their judgements were closely aligned, with Cohen’s κ reaching 0.82. On the back of that concordance, we treated the 100 annotated modules as a gold-standard pool for training and validation. In contrast, the remaining 1400 modules were held out for large-scale testing so we could probe how stable and reproducible the method is. This separation between a carefully annotated reference set and a larger, unseen pool mirrors common ML practice and reduces the risk of overfitting to a small number of examples.

To avoid tying the framework to any single domain, we based feature extraction on signals that do not depend on a particular ontology. For features, we used class-hierarchy depth, property-usage frequency, relationship density, and the level of annotation coverage. We then compared multiple ML families (random forests, gradient-boosting machines, and deep neural networks) to balance predictive accuracy against computational efficiency. This setup operationalizes the general framework in an educational setting while preserving full RDF/OWL compatibility and enabling replication in other domains via retraining and metric reweighting.

Within the 100-module gold set, we compared models using five-fold stratified cross-validation, with folds being balanced by overall expert quality rating. For the tree-based models, we performed a small grid search over the number of estimators (100–400), maximum depth (4–12), and minimum samples per split. The final gradient-boosting configuration used 300 trees, a maximum depth of 6, and a learning rate of 0.05, which gave the best trade-off between accuracy and runtime. Random forests were configured with 200 trees and a maximum depth of 10. The neural model consisted of three fully connected hidden layers (64, 32, and 16 units) with ReLU activations, dropout of 0.2, and early stopping based on a 10% validation slice of each training fold. All models were implemented using standard libraries (scikit-learn for tree-based methods and PyTorch 2.2.2 for the neural network) and trained on a workstation with an Intel i7-class CPU and 32 GB of RAM.

During evaluation, the continuous facet scores produced by these models were thresholded into binary labels using cut-offs tuned on the validation folds of the 100-module gold set. Specifically, for each fold we selected the decision threshold that maximized F1 on the validation portion of that fold, and we then applied the resulting thresholds to compute precision, recall, and F1 against expert annotations. To check robustness, we also verified that performance did not change materially for small perturbations around the selected thresholds (a sensitivity check over nearby cut-offs). Precision, recall, and F1 reported in Section 5.2 are computed from these binary decisions against the expert annotations. The same scores also serve as ranking signals: ontology modules are ordered by their predicted need for revision, and this ranking underpins the mean average precision (MAP) values.

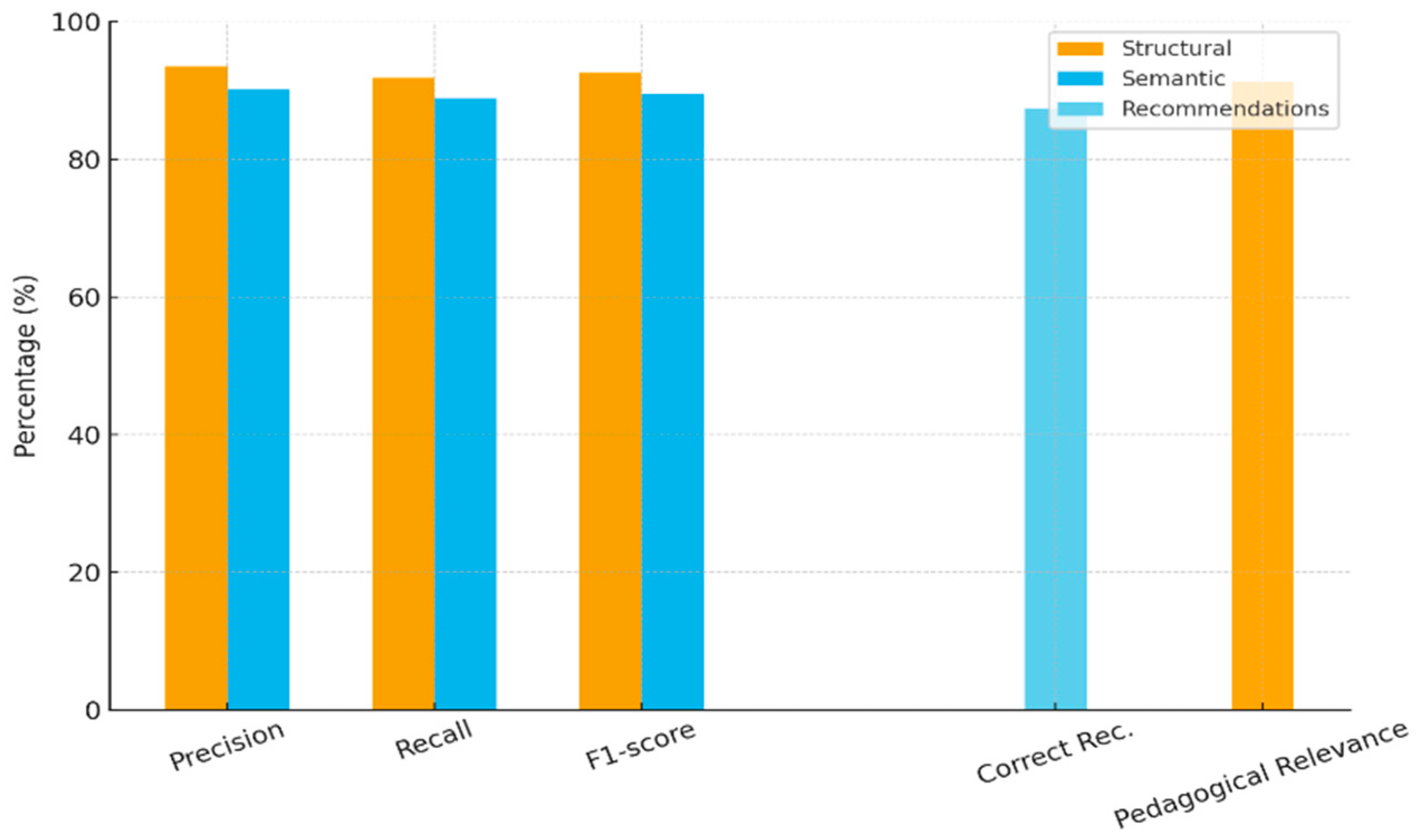

5.2. Quantitative Evaluation Results

Performance was measured using standard metrics: precision, recall, F1-score, recommendation accuracy, and system-level efficiency (MAP and processing time). We began with the expert-annotated set of 100 modules and then scaled to the full corpus of 1500 to test stability under varying structural and semantic complexity. For clarity, the “structural” and “semantic” results below report predictive performance of the ML assessors against expert labels, whereas recommendation accuracy and pedagogical relevance reflect downstream evaluation of the proposed fixes by experts and practitioners; baseline comparisons, where used, refer to rule-/reasoner-driven checks without learned scoring. The framework achieved precision of 93.5% for structural checks and 90.2% for semantic checks, with recall of 91.8% and 88.9%, respectively (Table 1). In both cases, F1-scores stayed above 89%, so the system does not gain accuracy by sacrificing recall. The very high structural precision suggests that hierarchical and organizational patterns are being captured reliably. Semantic performance is a little lower, which is to be expected given the difficulty of modeling prerequisite links and abstract conceptual relations. Within the 100-module gold set, performance on the validation folds closely matched performance on the corresponding training folds, which supports the claim that the framework behaves robustly within this domain. These values should nevertheless be interpreted as upper bounds for this particular dataset rather than as guaranteed performance levels in other application areas.

Table 1.

Quality assessment performance (values are averaged over five-fold stratified cross-validation on the 100-module gold set).

On the whole, the system recommended well. According to expert ratings, 87.4% of the system’s suggestions were judged correct, and in many cases it pointed directly to the parts that needed improvement (Table 2). Looked at from the teaching side, the picture is very encouraging: 91.3% of the suggested changes were judged relevant to real educational needs. That close match with classroom reality shows that the output is not only statistically sound but also in line with everyday practice and basic pedagogical principles. In concrete terms, teachers can fold these recommendations into their planning instead of treating them as ideas that only work on paper. The high recommendation accuracy also indicates that false positives, while present, do not dominate the revision workload. All of this suggests that when ML-based inference is steered by clear, structured quality metrics, it can keep technical rigor while still producing advice that fits the context and realities of teaching.

Table 2.

Improvement recommendation accuracy (expert/practitioner ratings on the evaluation subset).

From the system-wide metrics, the framework appears to run efficiently. At 0.892, the mean average precision shows that ontology modules requiring revision, treated as the relevant elements in the ranking, are usually placed near the top of the list. For each ontology, processing finishes in roughly 1.8 s, so users experience the feedback as almost immediate (Table 3). These figures indicate that the framework can be slotted into routine maintenance workflows with little disruption and without putting much extra strain on existing infrastructure. In our experiments, these timings remained stable across repeated runs and across different ontology sizes within the EDUKG-derived corpus.

Table 3.

System performance metrics (computed on the full 1500-module corpus; processing time is reported per ontology module).

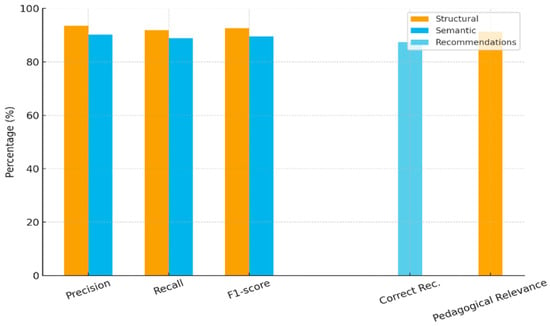

Figure 2 summarizes the main quantitative results. From a structural point of view, precision, recall, and F1 all stay above 91%, which points to consistently strong performance. By comparison, semantic scores are slightly lower, yet they still remain above 88% and thus stay in a robust range. As for the recommendations, accuracy reaches 87.4%, while pedagogical relevance is even higher at 91.3%. These numbers show that the suggested refinements are not only statistically reliable but also closely aligned with real teaching needs.

Figure 2.

Combined accuracy and relevance results validated on the annotated 100-module subset and confirmed on the full 1500-module dataset. Although some bars partially overlap due to the combined visualization of related metrics, this presentation does not affect interpretation of the results; exact values are reported in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Speed and scalability hold up as well. A MAP of 0.892 shows that relevant ontology elements are reliably pushed toward the top of the ranking, rather than buried in the list. Each ontology is processed in about 1.8 s, which is quick enough to give feedback that feels almost immediate while still supporting larger deployments (Table 3). As a whole, these properties make the framework a practical choice for continuous development and maintenance in educational settings, without introducing significant computational overhead. Although the evaluation is domain-specific, the methodology is robust and, given targeted retraining and metric tuning, is well positioned to transfer to other ontology-driven contexts. Such transfers will require fresh gold-standard annotations and careful comparison with domain-specific baselines to confirm that the gains observed here carry over.

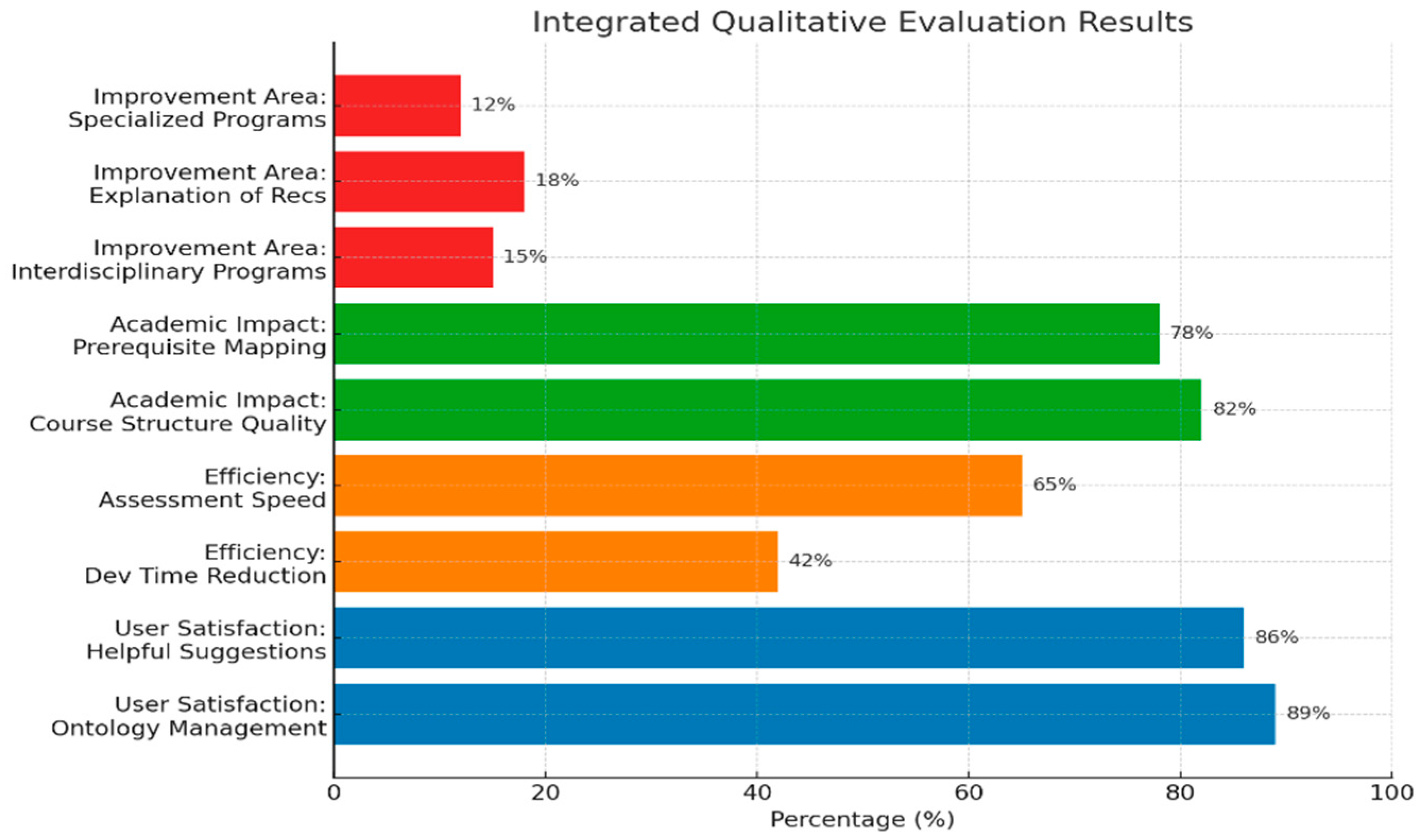

5.3. Qualitative Evaluation Results

We ran a post-use satisfaction study with N = 48 educational practitioners from three institutions (lecturers = 27, program coordinators = 12, quality-assurance officers = 9). Over four weeks, participants employed the system for routine tasks (ontology updates, prerequisite validation, and quality-report review) alongside their existing tools.

Perceptions were captured using a 12-item questionnaire on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree … 5 = strongly agree). The instrument examined perceived improvement in ontology management, usefulness of system recommendations, learnability, and intention to reuse. To limit response bias, three items were reverse-coded, and internal consistency was strong (Cronbach’s α = 0.86).

Two outcome variables (improved ontology management and helpful quality suggestions) record the share of respondents selecting 4 or 5 on the relevant items (Table 4). Free-text comments were inductively coded by two raters with agreement κ ≥ 0.75. Overall, 89% of users reported improved ontology management, and 86% rated the suggestions helpful, indicating high perceived usefulness and usability. These proportions correspond to roughly nine out of ten participants reporting positive experiences, despite differences in role and institutional context.

Table 4.

User satisfaction metrics.

Efficiency gains were evaluated through time-and-motion logging in two case studies (Institution A = 18 users; Institution B = 14 users). Participants completed matched ontology-creation and quality-audit tasks before and after adopting the framework. The logging API and a screen-time tracker recorded active task duration and throughput (ontologies per hour). Median reductions of 42% in development time and 65% improvement in quality-assessment speed (Table 5) were statistically significant (Wilcoxon p < 0.05). These figures reflect paired comparisons for the same users before and after adoption, thereby controlling for individual differences in expertise.

Table 5.

Efficiency improvements.

Academic impact was further examined by an expert panel (n = 9) comprising curriculum leads, program directors, and instructional designers. A four-subscale rubric (course-structure quality, prerequisite mapping, documentation completeness, and cross-program consistency) was used with 0–4 ordinal anchors. Rubric reliability was strong (ICC(2,k) = 0.82). Experts independently scored 60 ontologies before and after applying system recommendations. As shown in Table 6, 82% of ontologies improved in course-structure quality and 78% improved in prerequisite mapping (Wilcoxon p < 0.05). Improvements on the remaining subscales were more modest but followed the same general trend.

Table 6.

Academic impact.

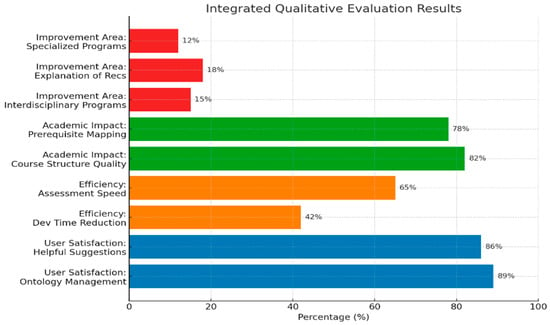

The open-ended feedback converged on three primary areas that need strengthening: better handling of interdisciplinary programs (15%), clearer explanations of system recommendations (18%), and improved support for specialized academic programs (12%) (Table 7). Future work will focus on three priorities: explainability of recommendations, flexible handling of interdisciplinary programs, and support for highly specialized programs.

Table 7.

Areas for improvement.

Figure 3 brings together user satisfaction, time savings, academic impact, and the main areas where users see room for improvement. In terms of satisfaction, 89% of participants report that ontology management has become easier, while 86% say the recommendations help them in their everyday work. Speed-wise, the system cuts effort: development tasks finish about 42% faster, and assessment activities take roughly 65% less time. When experts reviewed these outcomes, they stressed that the benefits go beyond convenience or automation and also support academic quality. Users, for their part, highlight two clear priorities for future work: more transparency about how the system produces its suggestions and more flexibility so it can adapt to a wider range of domains. The qualitative results portray a tool that fits reasonably well into existing workflows but still needs clearer explanations and broader coverage of program types.

Figure 3.

Integrated summary of qualitative evaluation results. User satisfaction (blue), efficiency improvements (orange), academic impact (green), and areas for improvement (red) are expressed as percentages of positive responses or observed gains.

Both the quantitative and qualitative findings point in the same direction. They indicate that the framework does more than streamline the workflow; it also sharpens how ontology quality is assessed. This translates into more efficient work and higher satisfaction for staff in educational settings.

Up to this point, however, our evidence comes mainly from a single domain. A natural next step, therefore, is to deploy the framework in other areas and see how it behaves there. Even under this constraint, the overall picture remains encouraging. Thanks to its modular design and stable performance, the framework can be tailored to other ontology-based systems. Each new domain, though, will need its own round of careful recalibration and retraining. Future studies should also report comparative baselines, confidence intervals, and raw descriptive statistics, so that the observed benefits can be weighed more precisely against alternative approaches.

6. Discussion and Benchmark Comparison

6.1. Discussion

The implementation and evaluation of the framework clarified its performance and usability. They also highlighted where it still needs work. We can now see both its strengths and the areas where further development would add the most value. The quantitative picture shows that the framework scores strongly on both structure and meaning. With regard to structural quality, it achieves 93.5% precision, 91.8% recall, and an F1-score of 92.6%. Semantic evaluation comes out slightly lower, with 90.2% precision, 88.9% recall, and an F1-score of 89.5%. Even so, these values still indicate solid performance. Overall, the system can detect and assess hierarchical and relational quality issues in complex ontologies.

If we look beyond raw accuracy scores, the recommendation results show how the framework behaves once it is put to work. In practice, 87.4% of its suggestions are rated as correct, and 91.3% are judged pedagogically relevant. In short, the system’s proposals are technically consistent and still make sense to teachers and learners. That balance matters in education, where an ontology has to be formally sound and, at the same time, readable and usable in everyday teaching. The relatively small gap between “correct” and “pedagogically relevant” recommendations also suggests that most technically sound edits translate into changes that practitioners can adopt without major rework.

On the operational side, the framework also holds up well. It maintains a strong level of analytical accuracy, with a mean average precision of 0.892. Processing a single ontology takes around 1.8 s, so users experience the feedback as almost instant. Because the computational cost is low, the system can slot into continuous quality-monitoring workflows, even in institutions that update ontologies frequently but have limited resources. These runtimes were obtained on standard workstation hardware, which indicates that the approach is deployable without specialized infrastructure.

From the users’ point of view, the qualitative results tell a similar story. Survey data show that 89% of participants felt ontology management had improved, and 86% reported that the system’s suggestions were genuinely helpful in their daily work. In the case studies, ontology-development time dropped by about 42%, and assessment work sped up by roughly 65%. This raises productivity without sacrificing clarity or trust. Because these figures come from paired pre/post measurements on the same users, they capture genuine efficiency gains rather than differences between user groups.

Finally, the expert reviews indicate a clear academic contribution. After the recommendations were applied, 82% of the examined ontologies showed better course-structure quality, and 78% had more clearly defined prerequisite links. Together, these changes strengthen the consistency and pedagogical coherence of educational ontologies. They also suggest that the framework is a useful tool both for curriculum design and for integrating semantic information across different systems. Even so, the expert panel focused on 60 ontologies in a single institutional context, so the academic impact should be confirmed with larger and more varied samples in future work.

Even with the strong overall results, participants still saw areas that need work. In their comments, 15% of users asked for more flexible handling of interdisciplinary programs. Another 18% emphasized the lack of clear explanations for how individual recommendations are produced. Support for highly specialized academic structures was also raised as an issue, with 12% requesting better coverage of these cases. These remarks set clear priorities for future work: stronger explainability, greater adaptability, and more transparent behavior across diverse use situations. In particular, improving the way the system explains why a specific change is recommended is likely to be as important as improving raw predictive performance.

Viewed as a whole, the framework shows a balanced profile. It combines high analytical accuracy, efficient computation, and broad user acceptance, while still attracting focused, constructive criticism. For now, the main limitations are based on adapting the approach beyond standard educational ontologies and on making the machine-learning components easier to understand. Progress in explainable AI, hybrid neuro-symbolic reasoning, and adaptive metric weighting is likely to ease these issues by improving both fairness and transparency in automated ontology assessment. Complementary baselines and confidence intervals would also help future evaluations to position this framework more precisely against alternative quality-assessment tools. More broadly, while the framework is designed to be ontology-agnostic, the present evidence is based on a single domain; cross-domain validation therefore remains a priority for future work rather than a conclusion drawn here.

From a broader Semantic Web perspective, the findings illustrate how combining ML with structured quality metrics and user-centered evaluation can significantly improve ontology management. The framework’s role is to support, not substitute for, rule-based checks and expert judgment. What it contributes is scalable, data-driven evidence that accelerates quality assurance. Oversight, however, remains firmly in human hands. The approach nudges ontology quality work toward systems that are smarter, easier to maintain, and better tuned to what users actually need. Looking ahead, the framework should be tried and adapted in other domains to see how well it works outside the educational setting. Each such deployment will require renewed training data, domain-specific calibration of metrics, and a careful check that the gains observed here remain plausible once the ontology structure and user needs change.

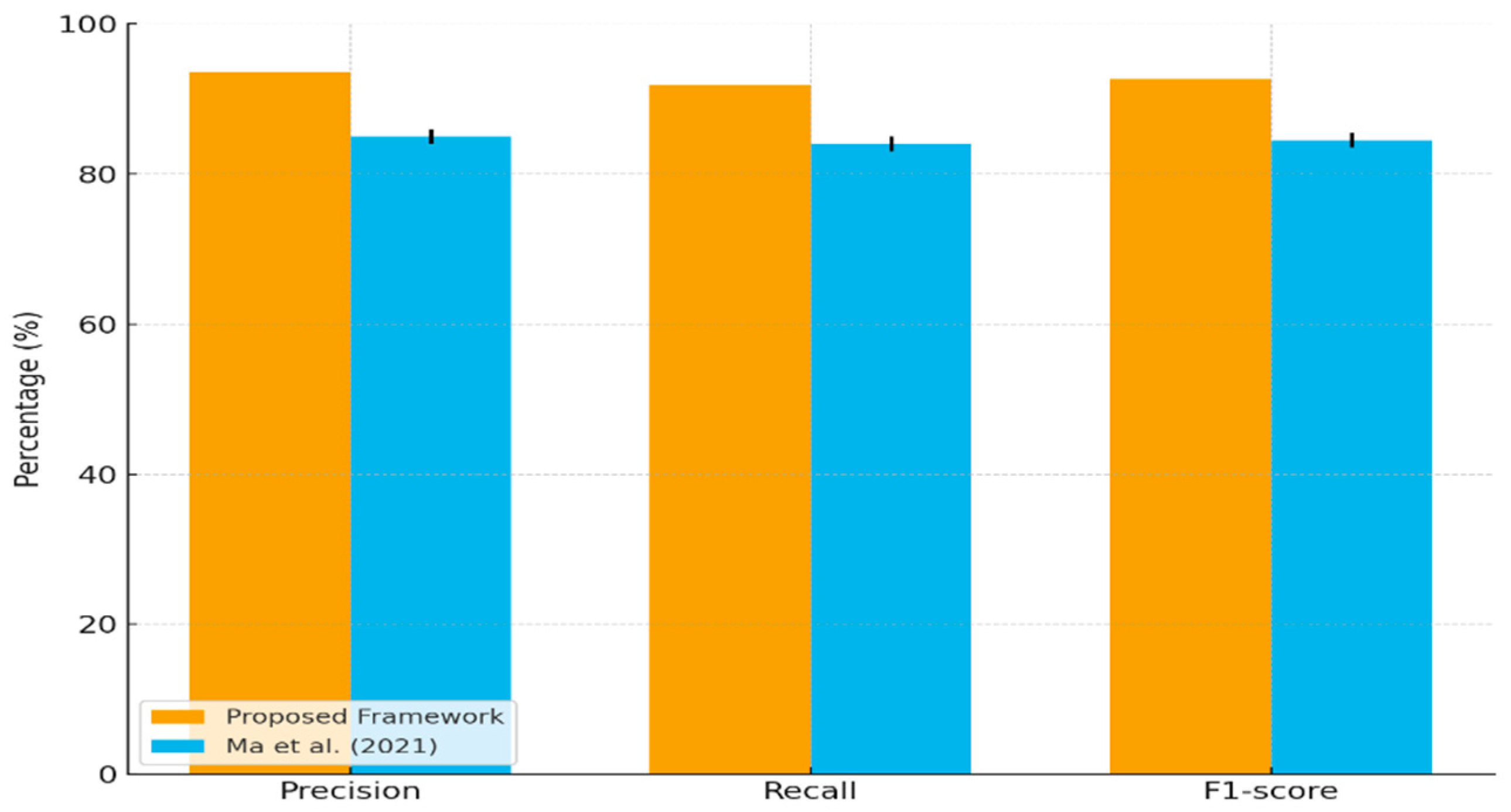

6.2. Benchmark Comparison

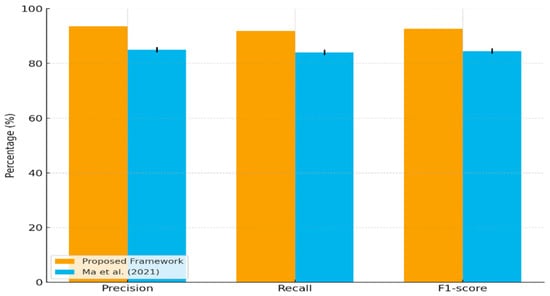

To further interpret these findings, this subsection situates the observed results within the context of prior work on ontology quality assessment. We look not only at performance scores but also at how each method is built. Among recent approaches, Ma et al. [38] are the closest match. Their method blends machine-learning techniques with logical reasoning to debug ontologies. In their study, reported precision lies around 84–86%, recall around 83–85%, and F1 in the 84–85% range.

Looking at our own results, the framework delivers 93.5% precision, 91.8% recall, and an F1-score of 92.6%. Within the educational setting studied here, these values are higher than the ranges reported by Ma et al. [38], suggesting that our framework can detect structural and semantic problems with fewer missed or wrongly flagged cases. We trace this gain to a different design choice. Rather than relying primarily on logical checks or model predictions alone, the framework couples multiple quality metrics with validation anchored in systematic expert and user feedback. In doing so, it moves beyond approaches that focus exclusively on structure or inference and instead exploits a richer and more context-aware signal. It is important to note, however, that Ma et al. evaluate their system on different ontologies and tasks, so the comparison is indicative rather than a strict head-to-head benchmark.

The work of Bakker et al. [43] uses large language models to learn ontologies directly from text. Its reported precision and recall sit in the mid-80% range. The evaluation, however, focuses only on extraction accuracy. Semantic coherence and overall completeness of the learned ontologies are left untested. This contrast highlights that higher extraction accuracy alone does not guarantee ontology quality once reuse, reasoning stability, and user interpretation are considered. These differences suggest that combining supervised ML with structured, domain-agnostic metrics can raise both accuracy and interpretability, while additional validation is still needed to confirm similar benefits beyond education-focused datasets.

Figure 4 compares our framework with Ma et al. [38]. It shows higher precision, recall, and F1 for the proposed framework, with error bars indicating the reported uncertainty (±1%) for Ma et al.’s values. The bars for our framework correspond to the mean scores reported in Table 1, whereas Ma et al.’s bars represent the midpoints of their reported ranges with ±1% variation to reflect uncertainty. This visual comparison is intended to provide contextual insight rather than a definitive benchmark, given the differences in datasets and evaluation protocols.

Figure 4.

Direct comparison of precision, recall, and F1 between the proposed framework and Ma et al. [38]. Bars for Ma et al. include ±1% error to reflect reported ranges (precision ≈ 84–86%, recall ≈ 83–85%, F1 ≈ 84–85%). Our framework values are from Table 1 (precision 93.5%, recall 91.8%, F1 92.6%).

Several prior contributions further contextualize this comparison. Bayoudhi et al. [44] focus on rule-based detection of inconsistencies in OWL 2 DL ontologies and evaluate their approach only on technical case studies, without involving users. Zhang et al. [37] assess structural quality in biomedical RDF datasets and report high URI error rates, but do not examine usability or end-user impact. Ma et al. [38] combine ML with logical reasoning and validate their approach using a small expert panel of fewer than ten participants, which limits generalizability. Bakker et al. [43] explore ontology learning with large language models and report precision and recall in the 70–75% range, alongside weaknesses in property completeness. Wilson et al. [29] propose a conceptual quality model that integrates pragmatic and social dimensions and explicitly foregrounds expert and user roles. Eivazzadeh et al. [45] present a healthcare study based on stakeholder-driven surveys, demonstrating the value of context-sensitive validation. Finally, Diniz Gomes et al. [46] report on a survey of 74 ontology engineers, in which more than 85% observed quality and speed gains from tooling, while also pointing to integration and documentation gaps.

To complement the textual comparison, Table 8 synthesizes prior qualitative and mixed-method studies and clarifies how our framework extends the literature. Rather than privileging a single evaluation lens, it couples quantitative rigor with user-driven validation to offer a fuller view of ontology quality. Our contribution lies in bringing together supervised ML, ontology-agnostic metrics, and systematic user and expert feedback in one reusable pipeline, rather than introducing a completely new evaluation dimension. In brief, the benchmarking suggests higher quantitative accuracy and broader user-centered validation than is typical of ontology-debugging or LLM-only approaches, while acknowledging that the evidence here comes from a single educational domain. As discussed in Section 6.1, transferring these gains to other domains will require careful recalibration of both training data and quality metrics.

Table 8.

Comparison of prior qualitative and mixed evaluation studies of ontology quality.

The framework therefore bridges quantitative precision with qualitative validation and moves ontology quality assessment toward more holistic, data-driven, and user-aware methodologies for the Semantic Web.

7. Conclusions

This study introduced a systematic, multi-phase framework that integrates ML with structured quality assessment to raise ontology quality across the Semantic Web. The approach does not treat evaluation and improvement as separate steps. It unifies multi-dimensional metrics, supervised learning, and a feedback loop to detect and correct structural and semantic deficiencies automatically. Applied to large-scale educational knowledge graphs, the framework achieved strong structural performance (precision = 93.5%, recall = 91.8%, F1 = 92.6%) and solid semantic results (F1 = 89.5%), while delivering notable efficiency gains (42% faster development and 65% faster assessment) and high user satisfaction (89% reporting improved management). Guiding ML-based inference with structured quality metrics turns out to work well: it produces dependable and efficient improvements. These results are supported by strong inter-annotator agreement (κ = 0.82) and a separation between a gold-standard reference set and a larger unseen corpus, which strengthens internal validity. At the same time, the reported figures reflect a single-domain deployment and should be interpreted accordingly.

Seen through a methodological lens, the work rests on two main pillars. In the first strand, we couple quantitative ontology metrics with machine-learning models so that one framework can both assess quality and propose focused refinements. In contrast, the second strand introduces a modular, repeatable pipeline that links automated analysis with expert and user feedback. As a result, quality assurance shifts from a one-off check to an ongoing, data-driven process that remains transparent and open to human oversight.

A study of 1500 ontology modules, combining quantitative indicators with qualitative feedback, showed that the framework is robust and usable in applicative contexts. Within this setting, it outperformed prevailing debugging and ontology-learning approaches on standard accuracy metrics, in particular when compared with the ranges reported by Ma et al. [38]. Because different studies rely on different datasets and evaluation protocols, these comparisons should be read as indicative benchmarks rather than definitive rankings.

With respect to external validity, generalization is supported primarily by design rather than by empirical breadth. Because the learning components are decoupled from domain semantics and rely on ontology-agnostic quality metrics, the workflow can be adapted with only limited retraining and metric calibration. In practice, this design supports potential deployment in healthcare (e.g., SNOMED CT, LOINC, FHIR), e-government (e.g., CPSV-AP, DCAT-AP), and industrial knowledge systems (e.g., Industry 4.0 and product-lifecycle management). Realizing this potential will require domain-specific annotations, explicit baselines, and careful validation in each new context, as cross-domain performance cannot be inferred directly from the educational results. In this sense, the present work outlines a scalable and transferable approach to ontology quality management rather than claiming universal effectiveness.

Opportunities for refinement remain. Future work should widen validation to genuinely heterogeneous ontology ecosystems instead of remaining within a single family of domains. It should also integrate explainable ML techniques, both to clarify how recommendations are produced and to surface issues of fairness, bias, and ethical data governance throughout the ontology lifecycle. Further directions include cross-domain transfer learning, adaptive metric weighting, and hybrid neuro-symbolic reasoning, all of which may deepen interpretability and improve robustness under changing domain conditions.

In sum, the proposed framework is built on a scalable, modular, and user-centered AI approach that balances technical rigor with everyday efficiency. Thereby, it marks a substantive step toward more intelligent, data-driven, and trustworthy knowledge infrastructures across the Semantic Web. The present study offers an initial, education-focused demonstration of this potential, laying the groundwork for broader empirical validation in future deployments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.J. and N.S.; methodology, W.J.; validation, W.J. and N.S.; investigation, W.J. and N.S.; writing—review and editing, W.J. and N.S.; project administration, W.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Project No. KFU253444).

Data Availability Statement

The ontology modules used in this study were derived from publicly available resources, including the EDUKG knowledge graph (https://github.com/THU-KEG/EDUKG, accessed on 15 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jaziri, W.; Gargouri, F. Ontology Theory, Management and Design: An Overview and Future Directions, Ontology Theory, Management and Design: Advanced Tools and Models; Gargouri, F., Jaziri, W., Eds.; IGI-Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2010; 46p. [Google Scholar]