Abstract

This paper investigates the physiological responses of individuals driving both on a real route and within a vehicle simulator designed as a digital twin of that route. The analysis of observed data patterns in stress response bio signals provides sufficient evidence of similarity to validating the driving simulation digital twin as a reliable replacement for real-world experiences in controlled and consistent settings, or when overall trends of physiological variables, rather than specific variable levels, are of interest. The findings also stress the need for optimizing the precision of digital twins in complex settings. This study introduces a time-series-based validation approach for driving digital twins by comparing continuous physiological trajectories between real and simulated driving.

1. Introduction

Digital twins (DTs) require not only structural and functional similarity but also equivalence in human–system interaction dynamics. For driving digital twins, this implies that not only average behavioral or physiological responses must be comparable, but that the temporal evolution of these responses must follow similar trajectories in real and simulated environments. As a digital representation of a physical system, a digital twin enables users to interact with a virtual counterpart and to simulate real-world dynamics with increasing fidelity [1]. This technology offers clear benefits—reducing cost, risk, and development time while enabling scenario testing that would be impractical in the physical world [2,3]. Despite its growing relevance, an important question remains: to what extent can user interaction with a digital twin replicate the physiological responses of real-world interaction, including the variability, sequence and timing of these responses during the entire driving episode? Addressing this question is critical for validating the realism and applicability of digital twins in practice [4,5].

In this study, we focus on driving digital twins as a representative application area [6]. Driving simulators are frequently used in vehicle development because they offer advantages over real-world tests in terms of cost and environmental control, providing a standardized and safe testing environment. For a simulator and its corresponding route to function as a true digital twin, the physiological responses of a person while driving in the simulator must correspond to those elicited during real driving. Only under such conditions can driving DTs be considered valid, as this comparability enables the use of DTs as reliable tools for driver training, safety testing, and vehicle development under realistic yet controlled conditions. A key differentiator of advanced DTs compared to traditional simulators is their focus on continuous, real-time, and often bidirectional data integration between the physical and virtual entity. Understanding if the digital twin reproduces the sequence and timing of physiological responses as the driver encounters specific events (e.g., intersections, lane changes, traffic density changes) is essential in validating simulations used in driving DTs. Thus, the following research question arises:

RQ: To what extent do time-resolved physiological trajectories during real-world driving and during interaction with a driving simulation digital twin exhibit temporal equivalence, and under which conditions can such a digital twin replace real-world driving tests?

To address this question, we compare participants’ physiological responses while driving along a real route and within a simulator designed as its digital twin. Previous studies have examined this simulator–reality comparison in limited settings, for example on short route segments [7]. This study extends the primary analysis by Czaban and Himmels [8], which examined aggregated experimental data from a driving simulation using Bayesian dependent t-tests and repeated-measures ANOVAs to assess simulator validity using driving segment-wise means of physiological and cognitive indicators. The present paper constitutes a secondary re-analysis that differs fundamentally in its theoretical framing (DTs) and analytical approach (time series analysis of granular experimental data). This paper examines the role of driving simulators in DTs by comparing time-resolved physiological trajectories that are essential for DT functionality, rather than segment-wise means (which collapse rich temporal structures into single aggregate statistics). By analyzing normalized time series across entire drives, we preserve temporal dynamics and assess temporal equivalence, a requirement for real-time digital twin interaction. Taken together, these two papers address distinct but complementary research questions, employ different data structures, and contribute to related but distinct scientific debates.

Our findings indicate a certain degree of physiological equivalence between real and simulated driving, suggesting that, under certain conditions, interactions with a digital twin can reproduce key aspects of real-world experiences. The results contribute to understanding the physiological realism required for DTs to serve as valid substitutes in domains where real-world testing is costly, time-consuming, or unsafe [9].

2. Related Work

2.1. Digital Twins and Their Applications

Digital twins are virtual representations of physical entities—objects, processes, or people—that mirror their state and behavior across the lifecycle through data-driven models [10,11]. A defining characteristic of advanced DTs is continuous, dynamic, and bidirectional data exchange between the physical and virtual systems, enabling real-time synchronization, learning, and adaptation [1,10]. Through integration of real-time and historical data, DTs support continuous monitoring, adaptive interventions, and predictive modelling.

DT maturity levels range from digital models (offline simulations), to digital shadows (unidirectional real-time data updates), to true digital twins with bidirectional data flows and closed-loop control [11,12]. True DTs can simulate and predict future states, test interventions virtually, and implement optimized actions in the physical system. Their ability to simulate rare or unsafe scenarios makes them particularly valuable in domains where real-world experimentation is costly or infeasible [13,14]. DT technology enables the design, operation, and maintenance of physical assets across many domains: manufacturing, healthcare, agriculture, aerospace, construction, transportation, etc. [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

DTs are increasingly used for city management, infrastructure planning, and user acceptance of smart city technologies [1,24,25,26,27,28]. DTs enable continuous monitoring of urban dynamics (e.g., traffic, energy use), adaptive interventions such as traffic re-routing or infrastructure adjustments, and predictive modeling to assess long-term impacts of policy or design decisions.

DTs support precision agriculture by integrating IoT sensor data with system-level models [29] to enable continuous monitoring of crops, livestock, and environmental conditions, adaptive interventions such as irrigation or fertilization adjustments, and predictive modeling of yields, disease risk, and sustainability outcomes. This supports data-driven decision-making under variable environmental conditions.

In healthcare, DTs can represent patients, diseases, or treatments to support personalized medicine [1,9,10,15,17]. Such DTs enable continuous monitoring of disease progression, adaptive treatment optimization based on patient response, and predictive modeling of future disease trajectories and treatment outcomes, improving shared decision-making and care quality.

Automotive DTs are widely used for vehicle design, traffic management, and autonomous driving validation [12,22,30]. DT-based simulations allow continuous monitoring of vehicle and driver states, adaptive interventions such as driver assistance or control strategy adjustments, and predictive modeling under rare or hazardous scenarios [31]. Driving simulator DTs enable prediction of driver distraction and risk by replicating real-world scenarios [32].

2.2. Simulation for Driving Digital Twins

Simulations, which encompass virtual environments (VEs), virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR), have become indispensable tools for replicating real-world scenarios within controlled virtual settings. Although the technical definitions of these terms diverge slightly, they are unified by a common objective: the virtual recreation of real-world situations to investigate the extent to which human behavior in virtual and physical environments aligns or diverges. As a result of developments in computing power and rendering technologies, simulations have become an increasingly prominent feature of a diverse range of disciplines, including psychology, training and design [33]. These tools permit the isolated and controlled study of the impacts of spatial environments on human perception and behavior, in accordance with the principle of behavioral realism, which seeks to evoke responses in virtual settings that mirror those in real-world environments [34,35].

The value of simulations lies not only in their capacity to approximate the intricacies of the real world, but also in their utility in addressing practical concerns. They have been employed for the evaluation of design alternatives, the enhancement of training environments in areas such as medicine and the military, and the assurance of safety in hazardous scenarios [33,36]. A significant benefit of simulations is their capacity to integrate the ecological validity of field studies with the experimental control of laboratory studies, providing a reproducible framework for experimental scenarios that is often unfeasible in the physical world [37,38]. Nevertheless, ensuring the transferability of insights from virtual to real-world contexts remains a challenge. For example, while physiological responses in simulations frequently mirror those observed in real-world scenarios, psychological reactions can display significant discrepancies. This underscores the necessity of continuous validation and optimization of simulation models and methods [39,40].

Across domains, immersive simulations have demonstrated strong benefits for training, design, and behavioral research. In sports, adaptive virtual environments improve real-world skill acquisition and long-term performance by tailoring practice to individual ability [41]. In architecture and environmental design, immersive simulations support controlled evaluation of cognitive and physiological responses to built environments, enabling evidence-based design decisions [42]. In medical, technical, and ergonomic training, VR and AR provide safe, repeatable, and high-fidelity practice of complex skills that outperform traditional methods [43,44]. Finally, in safety-critical domains, simulations offer realistic yet risk-free environments for studying behavior and training first responders, enabling experimentation that would be impractical or unsafe in real-world settings [45,46].

Driving simulators are a key enabling technology for driving digital twins because they allow controlled, repeatable, and safe replication of driving scenarios while capturing human responses under standardized conditions [6,47]. For a driving simulator to function as a meaningful component of a DT, its validity must be assessed against real driving in terms of subjective experience, behavior, and, crucially for this paper, physiological responses.

Driving simulator validity is typically examined through (i) subjective measures (e.g., perceived realism or stress), (ii) physiological measures (e.g., heart rate and electrodermal activity, while accounting for confounds such as simulator sickness), and (iii) objective behavioral measures (e.g., speed regulation and lane keeping) [48,49,50,51]. Validity is often discussed as absolute (numerical equivalence) versus relative (similar trends), with the latter frequently sufficient for research and design inference [52,53].

Driving simulators can reliably reproduce diverse road types and scenarios, enabling the study of driving dynamics such as speed, lane keeping, and errors [54,55]. Physiological and behavioral validation studies show strong similarities between real and simulated driving, including comparable heart rate, brain activity, and gaze patterns, supporting simulator presence, cognitive engagement, and both relative and absolute validity [7,56,57]. Nonetheless, simulator findings must be complemented with on-road validation to ensure generalizability, robustness, and safety in real-world applications [47,58,59].

Recent simulator validity reviews emphasize inferential statistics and correlation-based approaches but do not include time-series trajectory comparisons as a primary validation strategy [51]. This matters for DT contexts because DT functionality is inherently temporal: the intended use is typically not a single averaged state but an evolving state over time. Accordingly, this study evaluates temporal equivalence by comparing time-resolved physiological trajectories between real driving and the driving DT, complementing segment-wise aggregation with trajectory-level similarity assessment.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Context

To understand if a driving simulation DT can replicate a physical experience, we analyze data from an experimental study comparing the responses of participants in a simulated versus a real driving environment. The study focuses on measuring and comparing physiological stress measurements between the two experimental environments. The physiological stress response is believed to be related to performance [60], and therefore similar stress responses in the two driving environments will signal similar performance levels.

An initial simulation validation analysis from the experimental study was reported in [8]. In that work, the authors briefly describe the experiment and then use Bayesian comparisons of segment-wise means of physiological and cognitive measures to compare the simulation and real driving environments in aggregate. This approach provides evidence for absolute and relative validity at the level of aggregated segments, but it does not analyze the continuous temporal evolution of the physiological signals. Unlike the segment-based analysis in [8], this study focuses on continuous physiological trajectories, enabling time-resolved comparison of real and simulated driving dynamics. This allows evaluation of temporal equivalence rather than aggregated mean differences, which is essential for validating driving digital twins in real-time interaction settings.

3.2. Driving Simulation DT

The simulated driving DT was designed using a physical driving simulator (see Figure 1) that closely resembles a real vehicle and a virtual route that replicates a real-world driving experience, ensuring the simulator’s validity [61].

Figure 1.

The Driving Simulator and Golf 8 Cockpit View from Participant’s Perspective.

First, the driving simulator was built to closely replicate the vehicle used in the real-world test. The simulator uses components from a Volkswagen Golf 7, while the real vehicle is a Volkswagen Golf 8, which has similar dimensions, steering and pedal functionality as the previous model. The driving simulator is a mid-fidelity simulator [50] based on a D-Box motion system with three degrees of freedom and equipped with an original vehicle (Sparco) driver’s seat. The simulator has a Golf 7 force-feedback steering wheel and pedal set, providing realistic steering and ground feedback. The visual system consists of three 55-inch LCD screens, creating a 180° horizontal field of view to enhance participant immersion. The speedometer is digitally displayed on a screen. A high level of similarity between the simulator and real vehicle exists in terms of ergonomics and control elements (steering wheel, turn signal levers, other buttons, and pedal system) because the two Volkswagen models are based on similar platforms. The steering wheels of both models share a similar shape and tactile feel, including multifunction buttons, ensuring a consistent user interface. The pedal system is also comparable in terms of arrangement and resistance, allowing for an authentic transfer of driving inputs between the simulator and the real vehicle. Despite technological advancements in the Golf 8, such as a more digitized instrument cluster, the fundamental control concept remains similar.

Second, the simulated driving route was designed to closely replicate the real-world driving route (23 km, including urban, rural, and highway driving). Both the starting and ending points of the simulated route were identical to those of the real-world drive, ensuring high fidelity in route replication. This minimizes potential discrepancies in user experience due to hardware differences, ensuring the validity of the physiological and behavioral data collected.

The driving route was designed using the Silab (V7.2) software, developed by the Würzburg Institute for Traffic Sciences. This software allows the integration of OpenStreetMap data as a foundation, incorporating the topographical features of the real-world environment. Since OpenStreetMap provides not only road layouts but also precise street widths and lengths, the route could be reconstructed with a high degree of accuracy. The surrounding environment was designed by selecting pre-modeled buildings, with particular attention given to choosing structures that most closely resembled their real-world counterparts. Elements such as trees and other landscape features were added accordingly to create a realistic overall representation. For prominent landmarks along the route, especially the starting point, characteristic buildings were meticulously recreated using Blender and integrated into the simulation. This ensured that key orientation points from the real-world environment were recognizable in the virtual setting. Traffic signs, road markings, lights, and special road surfaces were replicated at identical locations in the simulator, ensuring high consistency and realistic visual perception relative to the real-world route. Figure 2 shows several sections of the real and the simulated routes.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Driving Route Sections (Real and Simulated).

3.3. Experimental Procedure

The experimental procedure was divided into several consecutive phases to ensure a systematic implementation. Participants were welcomed and introduced to the study protocol before completing a pre-study survey to collect demographic information and initial subjective assessments. After the pre-study survey, physiological sensors were attached and the participants proceeded to the real driving phase. During this phase, continuous physiological measurements were recorded. Subsequently, participants returned to the lab to transition into the simulation phase. To minimize the likelihood of simulator sickness and allow for adaptation, participants completed three short warm-up drives on standardized routes [62]. After this acclimatization period, participants drove a simulated route on the DT of the previously driven real-world route, with identical physiological parameters recorded. For practical reasons, the drives were conducted in a fixed order: the real drive always preceded the simulator drive. This simplified the experimental procedure and prevented potential safety risks in real traffic due to possible simulator sickness. The experiment concluded with a final debrief and participant farewell. Thus, both the real and simulated driving conditions were tested under comparable circumstances, enabling robust analyses and meaningful comparisons.

3.4. Measurements

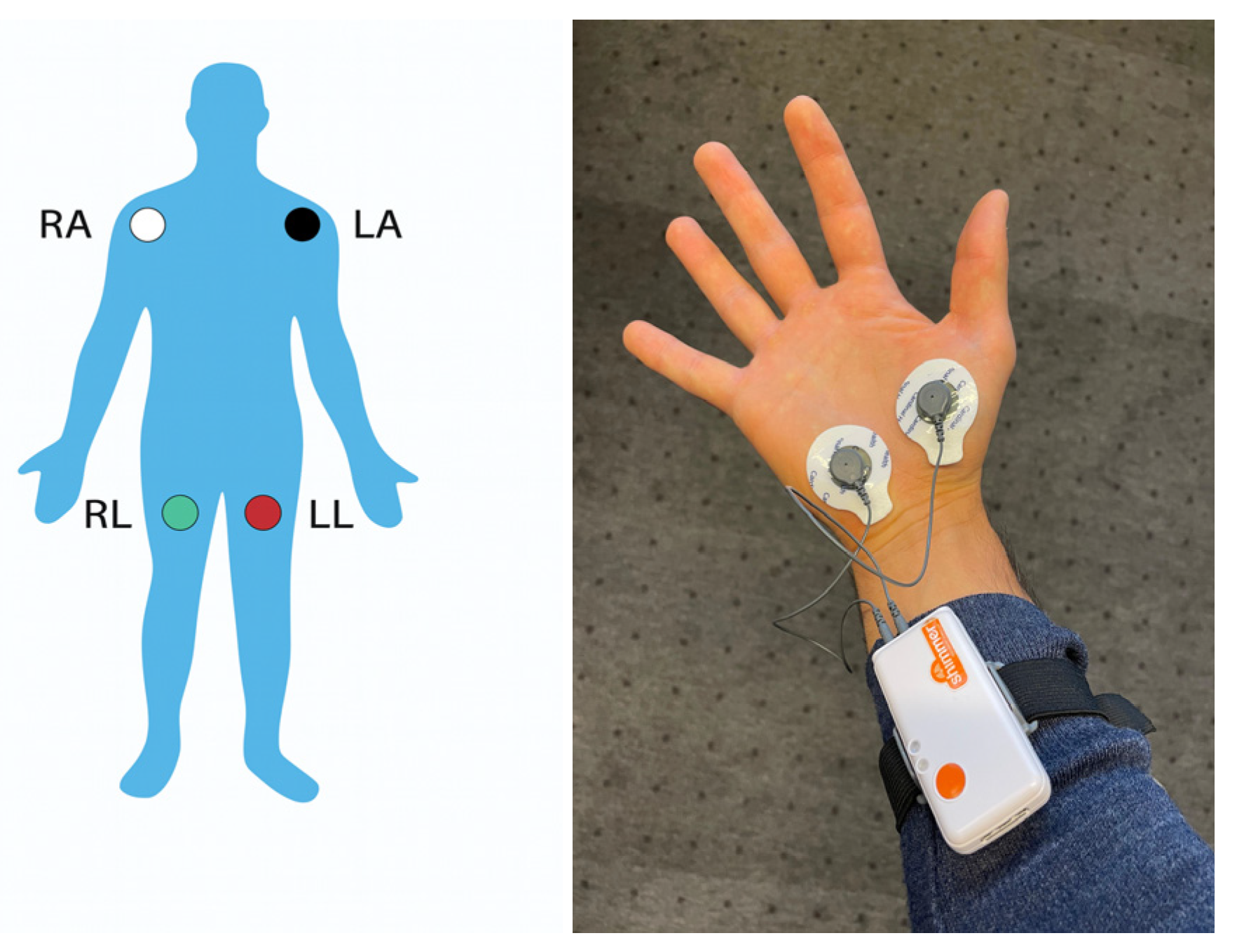

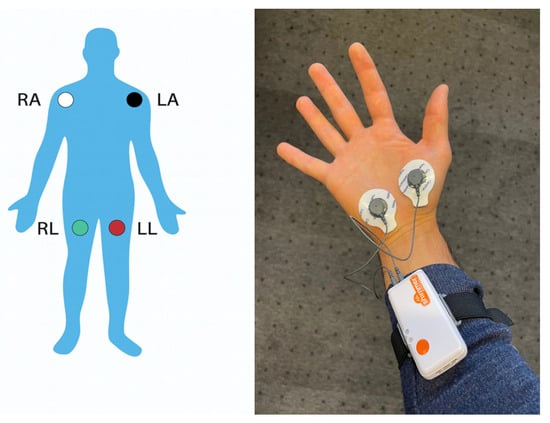

To understand the effect of the real and simulated ride experience on study participants, physiological measurements of their stress response were collected using electrocardiogram (ECG) and galvanic skin response (GSR) devices. ECG and GSR can measure several biological markers that are widely recognized as reliable indicators of autonomic nervous system (ANS) activation and regulation—which determines the physiological stress responses [60]. It is important to note that these physiological markers are mainly involuntary, and not easily manipulated or hidden, like psychological or behavioral metrics can be. Therefore, physiological markers can offer robust insights into the amount of stress experienced during various activities, and the associated expected performance level (which tends to follow an inverted U curve) [60]. Inverted U-shaped relationships have been found for similar variables as well, for example, between task demand (workload) and performance [63], in agreement with stress–performance results. Both ECG and GSR indicators can be used to predict if a driver has situational awareness or if he is distracted or fatigued [64,65]. Figure 3 depicts the placement of the ECG and GSR sensors.

Figure 3.

Placement of ECG and GSR sensors.

ECG markers included the heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) measures—RR interval (RR-Int), root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), and standard deviation of NN intervals (SDNN). HR, measured in beats per minute (bpm), exhibits a significant increase during stress conditions, reflecting the activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). This increase indicates the body’s heightened metabolic demand as it prepares for a “fight-or-flight” response to perceived threats. Elevated heart rate under stress is a well-documented phenomenon [66,67]. The RR interval, defined as the time between consecutive heartbeats, demonstrates an inverse relationship with heart rate, decreasing during stress. The Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD) serves as a measure of short-term heart rate variability and typically decreases under stress. Similarly, the Standard Deviation of NN Intervals (SDNN) also decreases [68,69]. ECG measurements were taken using the Shimmer3 EXG sensor (Shimmer, Dublin, Irleand), with electrodes placed in a four-point configuration. These were positioned below the left and right clavicles, above the right iliac crest, and on the left iliac crest (serving as the reference electrode). The Shimmer3 EXG sensor has been validated in several studies and proven reliable for physiological measurements [70,71,72].

GSR markers included the skin conductance response (SCR), peak amplitude (PA), and skin conductance level (SCL), which are electrodermal activity measures that increase significantly during stress due to the activation of sweat glands [60]. The GSR data were recorded using the Shimmer3 GSR+ sensor, which operates exosomatically with direct current [73]. Electrodes were placed on the palms of the participants’ non-dominant hands to ensure they could comfortably grip the steering wheel in both the real vehicle and the simulator. The Shimmer3 GSR+ sensor is frequently used in research and has provided valid results in similar contexts [74,75,76].

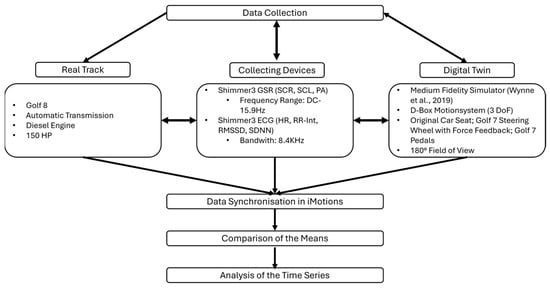

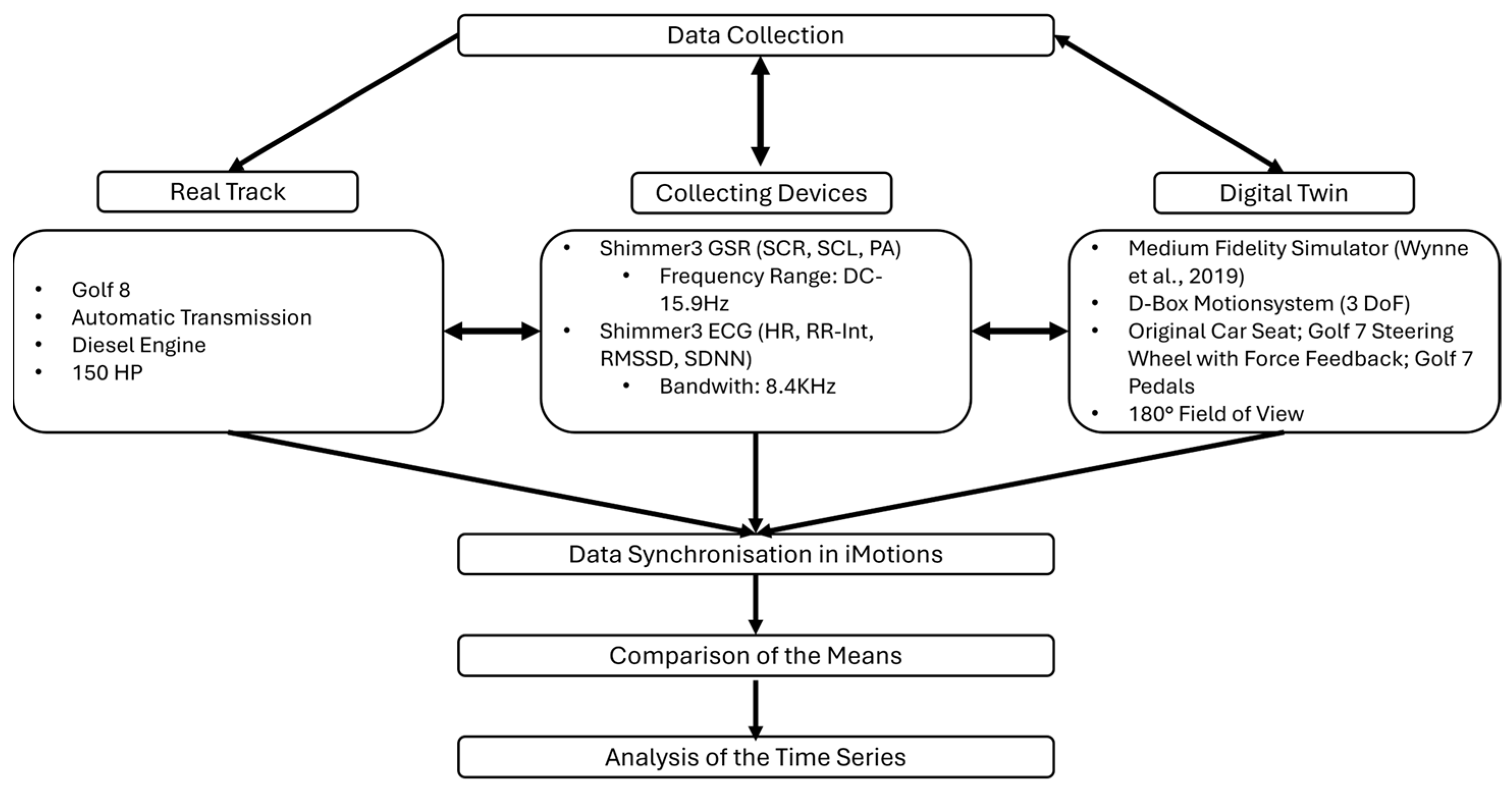

One of the challenges in data collection was synchronizing the data streams from the measurement devices to a common starting and ending point. To achieve this, iMotions Software 9.4 was utilized. The raw data collected during the experiment were processed using the integrated R algorithms of the iMotions software, which enabled both noise filtering and data segmentation. This processing included the calculation of heart rate (HR), heart rate variability metrics (HRV) such as the RR interval, RMSSD, and SDNN, as well as the segmentation of tonic and phasic GSR values (SCR, PA, SCL). These calculations and data preparations served as the foundation for further analysis of the participants’ physiological responses in both the real and simulated driving environments.

Figure 4 summarizes the data collection and preparation procedures, as well as the data analysis steps.

Figure 4.

Data Collection and Analysis [50].

Figure 4.

Data Collection and Analysis [50].

3.5. Participants and Sampling

The data was collected during the third quarter of 2023 in a small sized town in Germany. A convenience sampling method was used, with quotas set for age and gender to ensure a balanced sample. A total of 72 participants initially took part in the experiment; however, due to equipment failures and incomplete data for several experimental observations, only data from 68 participants is included in the final analysis. Participants were incentivized with €30 for their participation in the study. The final sample consists of 37 women (54.4%) and 31 men (45.6%), aged between 18 and 63 years (M = 30.07, SD = 11.58). Regarding educational background, most participants indicated they have either completed or are pursuing higher education (85.3%), while 8.8% have a high school diploma, and 5.9% have completed secondary school qualifications. In terms of regional origin, 41.2% identify as living in rural areas, 13.2% describe themselves as urban dwellers, and 45.6% categorize themselves as residents of small to medium-sized towns. Furthermore, none of the participants had any prior experience with a driving simulator.

The Ethics Committee of the University of Bayreuth approved the study. All participants took part voluntarily, and each participant was informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason.

3.6. Route Description

The driving route (both real and simulated) was approximately 23 km long. The route was divided into seven segments to encompass a wide range of driving scenarios and environmental conditions, intended to impose different cognitive demands on the driver and influence the driver’s physiological response. These segments included urban driving (5.3 km), rural roads (9.7 km), and highway driving (8 km). The division of the route into seven segments was based on the actual course of the selected circuit. The route was designed as a loop starting and ending at the university, ensuring coverage of all three driving environments (urban, rural, and highway). The highway section formed one continuous segment, while the urban and rural sections were naturally interspersed due to the loop’s geographical layout (e.g., rural stretches interrupted by short urban passages). This reflected the practical nature of the chosen route and allowed for a realistic representation of transitions between different driving contexts.

To mitigate the risk that physiological stress responses in simulated driving are weakly differentiated under low task demands [77], the study combined three different driving environments (urban, rural and highway), thereby increasing situational variability and supporting analysis across differing cognitive and environmental demands. This segmentation ensured that the driving simulator could realistically replicate diverse real-world scenarios, validating its versatility and applicability as a research tool. It should be noted that the segments were presented in a mixed order. Each driving environment was characterized by distinct attributes:

- Urban Driving: This environment had high stimulus density from crossings, intersections, signals, and congestion, requiring frequent speed changes and rapid decisions, and increasing mental workload and stress.

- Rural Roads: This environment involved longer stretches at steady speeds with occasional curves and overtaking and navigating narrow roads, producing a moderate cognitive and physiological load.

- Highway Driving: This environment involved high-speed driving under consistent conditions, with challenges such as merging, lane changes, and vehicle interactions requiring sustained attention and anticipation, despite some overall monotony.

4. Results

This section presents the empirical results of the study. First, descriptive statistics of the physiological stress indicators are reported for both the real and simulated drives across all route segments. Subsequently, the time series analysis is introduced to examine the similarity between simulator and real-world conditions in greater temporal detail. Finally, the main findings are summarized and discussed with respect to physiological stress patterns observed in both environments.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 report the minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation for each variable (SCR, SCL, PA, HR, RR-interval, RMSSD, and SDNN), both for the real drive (Real Ride) and the simulated drive (Sim. Ride), and separately for each one of the seven driving route segments. Driving route segments 1, 3, and 5 are classified as rural traffic, segments 2, 6, and 7 as urban traffic, and segment 4 as highway traffic. Paired t-tests (N = 68; SPSS v27; two-tailed; α = 0.05; pairwise deletion) are conducted to examine whether there are any significant differences between the two driving environments, and the corresponding p-values are also included in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 1.

Descriptives for Skin Conductance Response in real and simulated ride; 7 segments.

Table 2.

Descriptives for Skin Conductance Level in real and simulated ride; 7 segments.

Table 3.

Descriptives for Peak Amplitude in real and simulated ride; 7 segments.

Table 4.

Descriptives for Heart Rate in real and simulated ride; 7 segments.

Table 5.

Descriptives for RR-Interval in real and simulated ride; 7 segments.

Table 6.

Descriptives for RMSSD in real and simulated ride; 7 segments.

Table 7.

Descriptives for SDNN in real and simulated ride; 7 segments.

Data were screened for outliers; extreme values (>3 × IQR) were winsorized to the nearest non-extreme bound to limit their influence while retaining observations [78]. The normality assumption was evaluated on the difference scores (Real − Sim) for each segment and measure using Q–Q plots, histograms, and Shapiro–Wilk/Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. While the normality tests frequently rejected perfect normality—consistent with the behavior of physiological measures that often exhibit mild asymmetry [79]—visual inspection indicated only slight to moderate skewness without substantial anomalies.

Given the sample size (N = 68), the paired-sample t-test is robust to moderate deviations from normality of the difference scores [80], and by the Central Limit Theorem, the sampling distribution of mean differences is approximately normal for N ≥ 30, particularly when underlying departures are mild [81]. No correction for multiple comparisons was applied because the seven route segments represent a priori distinct driving contexts rather than repeated tests of the same effect, and the six physiological measures capture different constructs. Note that, in a within-subject design, the paired analysis reduces error variance by accounting for inter-individual variability. Consequently, the standard deviation of the difference scores is typically smaller than the raw standard deviations of each condition, which can yield relatively large t-values even when mean differences appear numerically small.

4.2. Time Series Analysis

By analyzing time-resolved physiological trajectories, we can assess whether the digital twin tracks the real-time evolution of stress responses in a way that is compatible with its intended use: continuous monitoring, adaptive interventions, and predictive modelling. To achieve this, the dataset was restructured into a long-format time series representation to enable trajectory-based analysis across the full driving duration. Through this process, columns are transformed into rows, converting a dataset from a wide format to a long format [82]. In our case, each segment of the route (column) becomes a new observation (row). This allows us to calculate averages for the entire duration of the drive rather than focusing solely on individual segments. To compare the physiological data between the entire real driving route and its DT, across participants, we first calculated the mean values of the physiological parameters and then performed a paired t-test.

The analysis of skin conductance showed that for the real drive, the Skin Conductance Response (SCR) (Table 1) had a mean value of 9.49 (range: 0.00–17.80; SD = 2.57), which was almost identical to the mean value of 9.53 (range: 1.61–16.72; SD = 2.49) for the simulated drive (p = 0.829). However, for the tonic Skin Conductance Level (SCL) (Table 2), a highly significant difference was observed: In the real drive, the mean was 12.87 (range: 2.32–57.18; SD = 6.31), while in the simulated drive, the mean was significantly higher at 14.47 (range: 2.32–102.55; SD = 8.62; p < 0.001). The Peak Amplitude (PA) (Table 3) also showed significant differences, with a mean of 0.29 (range: 0.00–0.84; SD = 0.18) in the real drive compared to 0.39 (range: 0.03–1.05; SD = 0.24) in the simulation (p < 0.001).

Significant differences were also found in heart rate (HR) (Table 4) between the real and simulated drives. The mean HR during the real drive was 82.79 bpm (range: 51.52–114.24; SD = 12.89), which was higher than in the simulated drive (mean = 77.02 bpm; range = 48.31–106.50; SD = 11.14; p < 0.001). The average RR interval (Table 5) was 758.50 ms (range: 530.12–1208.01; SD = 129.13) in the real drive, significantly shorter than 814.15 ms (range: 534.41–1231.49; SD = 133.13) in the simulated drive (p < 0.001). Regarding heart rate variability, represented by RMSSD (Table 6) and SDNN (Table 7), no significant differences were observed between the two conditions (RMSSD: p = 0.165; SDNN: p = 0.524).

Our analysis uses the continuous time series of physiological recordings. After normalizing timestamps to a common [0,1] scale, we compute Pearson correlations of the full physiological trajectories and visually inspect their temporal evolution.

The analysis focuses on normalized physiological time series, enabling direct comparison of temporal signal dynamics between real and simulated driving across the full interaction period.

Although averaging gives an insight into the similarity of the driving behavior of drivers in the simulator and on the real road, this is only a rough indication. Peaks and extreme values, which indicate intense or stress-related responses, are smoothed out by averaging, resulting in a loss of valuable information [83]. Mean values obscure important characteristics of time series data by failing to capture variability and response stability, which are critical for interpretation [84]. Context-specific effects, such as those arising during cornering or emergency braking, are also lost through averaging, masking the true nature of responses [85]. Moreover, averaging hinders analysis of adaptation and learning over time and prevents examination of dynamic interactions between variables [53]. For these reasons, we want to go one step further and investigate the time series similarity in more detail. To achieve this, we use the Pearson Correlation Coefficient on normalized time series. This linear correlation between two variables X and Y ranges from −1 and 1, where 1 is a perfect positive linear correlation, −1 is a perfect negative linear correlation, and 0 is no linear correlation. We also normalize the time series to a common scale, enabling a meaningful comparison independent of absolute values or differing measurement durations.

Conducting this time-series analysis required addressing several technical challenges that go beyond the procedures described in [8] and constitutes an analytical innovation for physiological DT validation:

- (1)

- Synchronizing real and simulated data streams with differing durations;

- (2)

- Normalizing the time axis to a dimensionless scale to allow comparison of drives with different lengths;

- (3)

- Restructuring the dataset via unpivoting so that each route segment becomes a separate observation in order to increase the effective sample size per segment and enable calculation of mean values over the entire drive instead of only segment-level averages;

- (4)

- Selecting similarity metrics that are both robust to noise and interpretable for practitioners (i.e., combining Pearson Correlation Coefficients of normalized trajectories with visual inspection of the curves, which jointly reveal pattern similarity and deviations that are completely invisible in segment-wise means).

To ensure a meaningful comparison between the time series from the simulator and real-world driving, we normalized the time axis for both datasets to a common scale of [0,1]. This normalization adjusts the timestamps of each dataset so that their relative progression is comparable, irrespective of their differing durations or absolute time values. The normalization is performed using the following formula, where Timestamp is the original time value for each data point, Timestampmin and Timestampmax are the minimum and maximum time values within the dataset:

This formula ensures that the earliest timestamp maps to 0 and the latest timestamp maps to 1, creating a dimensionless time scale that is independent of the original measurement duration. By normalizing both the simulator and real-world datasets, we aligned their time axes, enabling direct visual comparison of the signal dynamics.

TimeStamp denotes the original time value of a measurement, while TimeStampmin and TimeStampmax represent the first and last recorded time values of the respective dataset. Through this normalization, the starting point of every drive is mapped to 0 and the end to 1, creating a dimensionless and aligned time scale. This ensures that the temporal progression of the biosignals can be directly compared between real-world and simulated conditions, independent of absolute drive duration. In simple terms, this normalization ensures that all drives “start at 0 and end at 1”, no matter how long they actually lasted in minutes or seconds. Without this step, two time series with slightly different durations could not be compared fairly, because one would have more data points or a longer timeline than the other. By converting all timestamps into the same normalized scale, we align both curves so that the same relative moments of the drive can be compared—for example, the beginning (0.0), the middle (0.5), or the final part of the drive (1.0). We then use this NormalizedTime as the common time axis to visually overlay both time series and to calculate correlation values, ensuring a fair, consistent, and meaningful comparison of signal patterns between the real and simulated driving conditions. This step is critical for comparing datasets with different lengths or temporal resolutions, as it eliminates the impact of absolute time differences. The normalized time series were then plotted to visually assess their similarity.

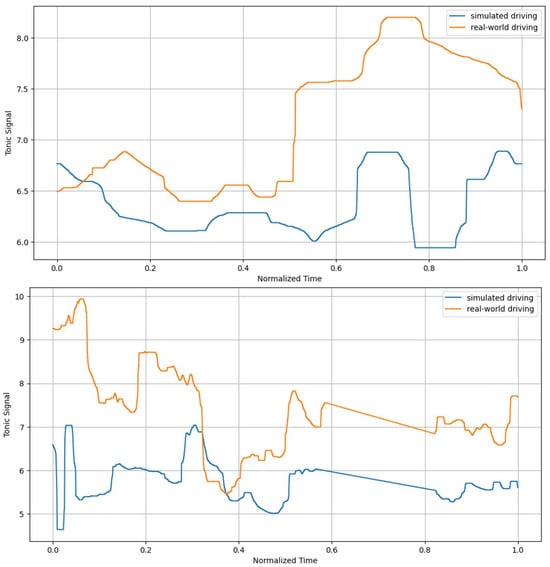

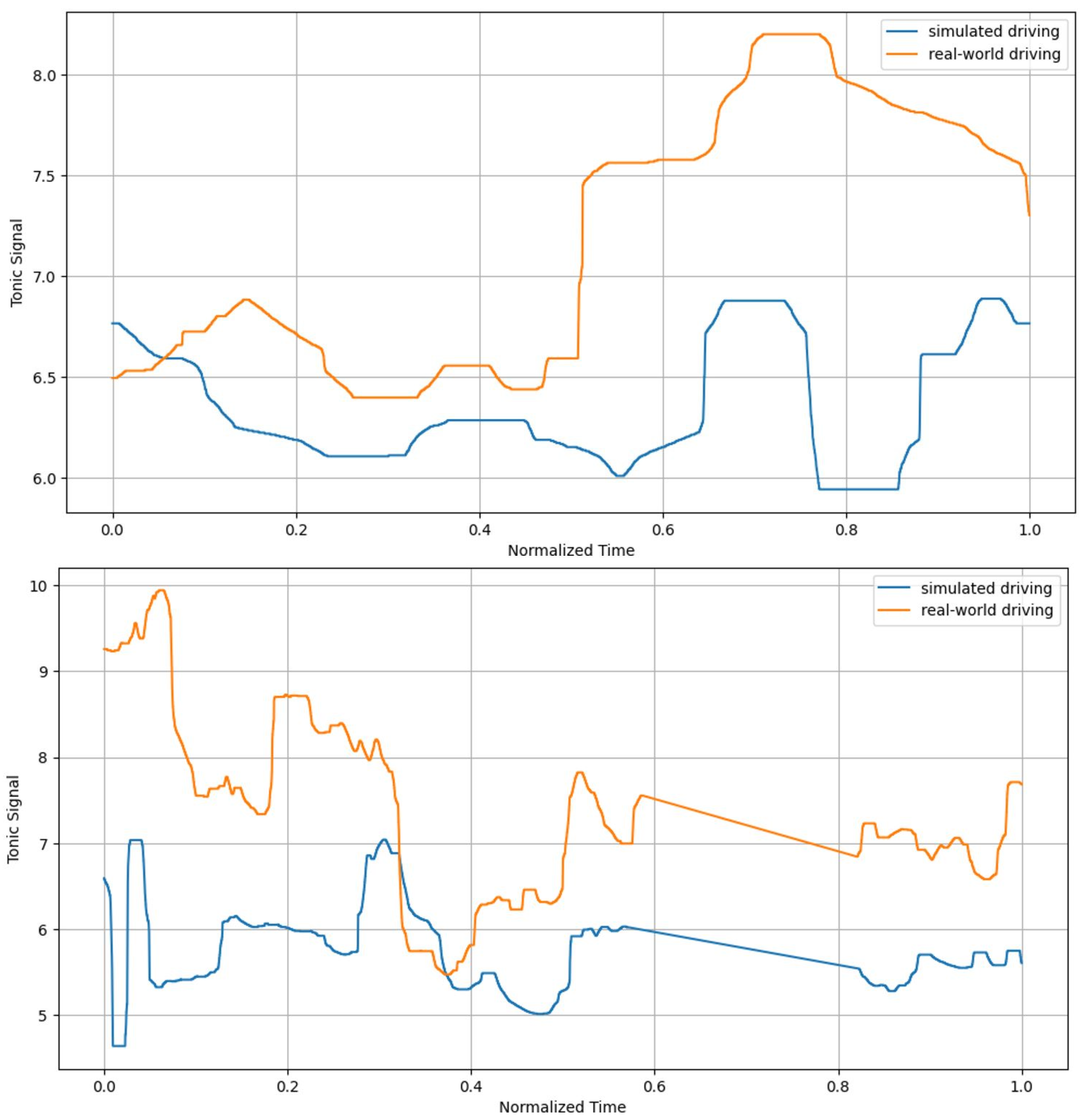

Figure 5 illustrates a biosignal time series for a participant driving the urban and rural segments, comparing data collected in the simulator and real-world conditions. The Pearson Correlation Coefficients for the urban drive (r = 0.31) and the rural drive (r = 0.34) suggest a moderate level of linear similarity between the simulator and real-world measurements. The normalization revealed strong parallels in the overall patterns of the tonic signal across both environments. This visual alignment, combined with the Pearson Correlation Coefficients, provides robust evidence for the comparability of the simulator and real-world measurements, supporting the validity of using simulators in such studies.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Two Time Series (for a participant driving the urban and rural segments, real and simulated; see code on GitHub [86].

Figure 5.

Comparison of Two Time Series (for a participant driving the urban and rural segments, real and simulated; see code on GitHub [86].

4.3. Discussion of Results

Analysis of the biosignal data reveals several notable findings regarding the physiological stress responses of the participants. In terms of cardiovascular responses, the real ride generally produces higher heart rate values, indicating greater physical exertion and more intense emotional experiences. In contrast, the simulated ride produces a less pronounced heart rate response, suggesting a less physically demanding experience. The longer RR intervals and higher RMSSD values during the simulated ride indicate a more relaxed heart rate variability, reflecting a less stressful physiological response. The real ride, with shorter RR intervals and higher SDNN values, results in greater cardiovascular stress and more intense responses. In addition, in terms of skin responses, the simulated ride tended to elicit greater sympathetic activation, as reflected by increased skin conductance response (SCR) and greater variability, particularly in the later stages. This suggests that the simulated experience may be perceived as more emotionally arousing or stressful, despite potentially being less physically challenging than the real ride. This trend is further supported by higher peak values and greater variability in skin conductance during the simulated rides.

The Skin Conductance Response (SCR) generally indicates higher sympathetic activation during the simulated ride in most segments, as reflected by somewhat higher mean values and greater fluctuations. The maximum values are also higher during the simulated ride, suggesting stronger autonomic responses.

Overall, the simulated ride leads to a stronger and more variable activation of the sympathetic nervous system compared to the real ride, which may indicate higher emotional stress or arousal during the simulation. In all seven segments, there is a general trend that the simulated rides exhibit higher Skin Conductance Level (SCL) than the real rides. This could suggest that the simulated experiences were either perceived as more intense or that the reactions were more strongly stimulated, even though they may offer fewer physical challenges compared to the real ride. The standard deviations are also generally higher in the simulated ride, which points to greater variability in skin conductance values, suggesting a more diverse range of reactions among participants.

The simulated rides exhibit higher peak amplitudes (PAs) in all segments compared to the real rides, suggesting that the simulated experiences generally elicit stronger peak responses. Particularly in later segments, the simulated rides show intense reactions and greater variability, possibly reflecting a broader emotional range.

The heart rate (HR) during the real ride is higher in all segments compared to the simulated ride, suggesting greater physical load. The higher maximum heart rate values during the real rides may reflect stronger peak reactions due to physical exertion or intense emotional experiences. In contrast, the simulated ride shows lower mean and maximum values, suggesting that it was less physically demanding or less exciting.

The RR intervals (RR-Int) are longer in all segments during the simulated versus the real ride, suggesting less physiological strain and more relaxed heart rate variability.

The mean RMSSD is higher during the simulated ride, indicating stronger parasympathetic activity and greater relaxation. Similarly, SDNN values tend to be higher, reflecting greater heart rate variability during simulation.

Overall, the analysis shows that the real ride generally produces higher heart rate values, indicating greater physical exertion, while the simulated ride elicits greater sympathetic activation in skin responses, pointing to higher emotional arousal.

Together, these findings suggest that simulated driving induces greater variability in physiological responses—especially sympathetic activation and heart rate variability—whereas real driving produces stronger, more consistent physical stress responses. This highlights the different physiological characteristics of real versus simulated experiences.

In summary, physiological data show complementary stress patterns in real and simulated driving: real driving induces stronger cardiovascular activation reflecting higher physical load, whereas simulation induces greater sympathetic responses reflecting higher emotional arousal. This supports the validity of driving simulators for studying stress while highlighting inherent physiological differences from real-world driving.

5. Summary, Limitations and Outlook

This study examines the similarity of physiological responses in real and simulated driving to assess the validity of simulators as proxies for real-world experience. The results show both meaningful similarities and systematic differences, indicating that while some physiological aspects are well replicated, others diverge due to inherent contextual and perceptual limitations of virtual environments.

The mean values comparison across route segments identifies similarities and differences between real and simulated driving. Higher skin conductance measures in the simulator suggest increased arousal potentially due to unfamiliarity or simulator configuration. Real-world driving elicited higher heart rates and shorter RR intervals, indicating greater physical and emotional strain. Notably, no significant differences were found in RMSSD and SDNN, suggesting comparable autonomic responses across environments.

The time series analysis shows higher correlation for rural driving, suggesting simulators better replicate less complex environments, while lower urban correlations reflect greater behavioral variability not fully captured by simulation. Despite only moderate correlations, the overall temporal trends are similar, indicating that key aspects of driver behavior are reproduced. These results highlight the value of time series analysis for studying comparability and support the use of simulators in time-dependent driving research.

Taken together, the mean and time-series analyses suggest that the driving simulation DT can serve as a useful tool for studying general physiological response patterns under controlled conditions. However, it does not fully replace real-world driving tests, particularly in complex or high-variability environments.

We believe the combination of DT framing and physiological time series analysis we present in this paper is novel and fills a gap at the intersection of DT research and real-time user interaction. We acknowledge there is a small but growing body of research that employs time-series techniques in driving simulation studies (i.e., dynamic time warping and similarity metrics linking ECG/EMG signals to risk patterns in intersection scenarios, as well as Pearson correlations of driving behavior time series) to quantify consistency between real and simulated driving. However, to the best of our knowledge, no prior study (1) conceptualizes a driving simulator explicitly as a digital twin, (2) evaluates physiological time series trajectories as the primary comparison object, and (3) links trajectory similarity to the conditions under which a digital twin may replace real-world testing.

These findings indicate a need to improve DT precision in complex, particularly urban, driving contexts. Future work should better differentiate driving scenarios, examine links between physiological stress and driving performance, and address limitations in ecological validity such as reduced motion cues, environmental variability, and perceived risk. Future studies should also mitigate potential order effects through randomized designs, and employ adaptive simulation algorithms that enable real-time bidirectional data integration, better capture real-world variability, and improve alignment with actual driving behavior. Furthermore, researchers could explore DT interface designs that enhance realism and physiological engagement to improve user interaction and performance.

The insights from this study contribute valuable knowledge to both theory and practical applications of digital twins. From a theoretical perspective, our findings enhance the understanding of user interaction with DTs, especially regarding how physiological equivalence between simulation and reality can serve as an indicator of accuracy. This offers a basis for future research exploring the psychological and perceptual alignment between DTs and their physical counterparts, further developing criteria for evaluating DT effectiveness. From a practical perspective, our findings make an essential contribution to the evaluation of DTs’ ability to replicate real-world environments in general, and to the specific area of vehicle simulation in particular. The observed similarities suggest that certain physiological and behavioral dynamics of real driving can be approximated within the simulator, though substantial contextual and sensory differences remain. These limitations emphasize that simulation-based DTs should currently be viewed as complementary, rather than equivalent, to real-world testing. This insight is of significant interest for industries where real-world experiences are costly, time-consuming, impractical, dangerous, or unethical. The results suggest that DTs can be a valuable tool for studying general physiological trends under controlled and consistent conditions, but that further optimizations are necessary for increasing accuracy for complex environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., E.S., A.C., C.C., J.R. and S.W.; methodology, M.C., E.S., C.C., J.R. and S.W.; software, M.C. and E.S.; validation: M.C.; formal analysis, M.C., E.S., C.C., J.R. and S.W.; investigation, M.C.; resources, M.C., J.R. and S.W.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C., E.S., A.C., C.C., J.R. and S.W.; writing—review and editing, M.C., E.S., A.C., C.C., J.R. and S.W.; visualization, E.S.; supervision, C.C., E.S., J.R. and S.W.; project administration, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Bayreuth (application number: 25-008 and date 30 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Eldar Sultanow was employed by the company Capgemini Deutschland GmbH. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Semeraro, C.; Lezoche, M.; Panetto, H.; Dassisti, M. Digital twin paradigm: A systematic literature review. Comput. Ind. 2021, 130, 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, M.; Attaran, S.; Celik, B.G. The impact of digital twins on the evolution of intelligent manufacturing and industry 4.0. Adv. Comput. Intell. 2023, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Srivastava, R.; Fuenmayor, E.; Kuts, V.; Qiao, Y.; Murray, N.; Devine, D. Applications of digital twin across industries: A review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, M.; Murat, U.; Oksuz, B.; Parlaktuna, A.M.; Pisirir, E.; Testik, M.C. Digital twins in manufacturing: Systematic literature review for physical–digital layer categorization and future research directions. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 35, 679–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.; Chen, C.H.; Zhong, R.Y. A review of digital twin in product design and development. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 48, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piromalis, D.; Kantaros, A. Digital twins in the automotive industry: The road toward physical-digital convergence. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.J.; Chahal, T.; Stinchcombe, A.; Mullen, N.; Weaver, B.; Bédard, M. Physiological responses to simulated and on-road driving. Int. J. Psychophysiol. Off. J. Int. Organ. Psychophysiol. 2011, 81, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czaban, M.; Himmels, C. Investigating simulator validity by using physiological and cognitive stress indicators. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2025, 114, 831–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, I.; Inojosa, H.; Dillenseger, A.; Haase, R.; Akgün, K.; Ziemssen, T. Digital twins for multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 669811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barricelli, B.R.; Casiraghi, E.; Fogli, D. A survey on digital twin: Definitions, characteristics, applications, and design implications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 167653–167671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.; Fan, Z.; Day, C.; Barlow, C. Digital twin: Enabling technologies, challenges and open research. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108952–108971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botín-Sanabria, D.M.; Mihaita, A.-S.; Peimbert-García, R.E.; Ramírez-Moreno, M.A.; Ramírez-Mendoza, R.A.; Lozoya-Santos, J.D.J. Digital twin technology challenges and applications: A comprehensive review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chircu, A.; Czarnecki, C.; Friedmann, D.; Pomaskow, J.; Sultanow, E. Towards a digital twin of society. In Proceedings of the 56th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mihai, S.; Yaqoob, M.; Hung, D.V.; Davis, W.; Towakel, P.; Raza, M.; Karamanoglu, M.; Barn, B.; Shetve, D.; Prasad, R.V.; et al. Digital twins: A survey on enabling technologies, challenges, trends and future prospects. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 2255–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller-Andorno, N.; Christen, M.; Krauthammer, M.; Witt, C. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine–Objectives and Recommendations for the Responsible Use of DIGITAL Twins; Position paper; University of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Iranshahi, K.; Brun, J.; Arnold, T.; Sergi, T.; Müller, U.C. Digital twins: Recent advances and future directions in engineering fields. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 26, 200516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaga Priya, P.; Reethika, A. A Review of Digital Twin Applications in Various Sectors; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 239–258. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Fang, S.; Dong, H.; Xu, C. Review of digital twin about concepts, technologies, and industrial applications. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 58, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moenck, K.; Rath, J.-E.; Koch, J.; Wendt, A.; Kalscheuer, F.; Schüppstuhl, T.; Schoepflin, D. Digital twins in aircraft production and MRO: Challenges and opportunities. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2020, 15, 1051–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; San, O.; Kvamsdal, T. Digital twin: Values, challenges and enablers from a modeling perspective. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21980–22012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanDerHorn, E.; Mahadevan, S. Digital twin: Generalization, characterization and implementation. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 145, 113524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Liu, C.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, H. Digital twin analysis for driving risks based on virtual physical simulation technology. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif. 2022, 6, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Pan, W. Opportunities and challenges of digital twin applications in modular integrated construction. In Proceedings of the 37th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (ISARC); Osumi, H., Furuya, H., Tateyama, K., Eds.; International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction (IAARC): Kitakyushu, Japan, 2020; pp. 278–284. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, T.; Zhang, K.; Shen, Z.-J.M. A systematic review of a digital twin city: A new pattern of urban governance toward smart cities. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2021, 6, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ma, L.; Broyd, T.; Chen, W.; Luo, H. Digital twin enabled sustainable urban road planning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Parlikad, A.K.; Woodall, P.; Don Ranasinghe, G.; Xie, X.; Liang, Z.; Konstantinou, E.; Heaton, J.; Schooling, J. Developing a digital twin at building and city levels: Case study of West Cambridge campus. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 05020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, D.; Kohl, P.; Kummert, A. Smart cities and innovations: Addressing user acceptance with virtual reality and digital twin city. IET Smart Cities 2022, 4, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrotter, G.; Hürzeler, C. The digital twin of the city of Zurich for urban planning. PFG–J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Geoinf. Sci. 2020, 88, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdouw, C.; Tekinerdogan, B.; Beulens, A.; Wolfert, S. Digital twins in smart farming. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Ling, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, K.; Guo, G. A systematic review on the current research of digital twin in automotive application. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, M.U.; Yan, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhai, Y.; Han, P.; Nawaz, S.A.; Raza, M.A.; Akbar, M.W.; Hussain, A. Autonomous driving test system under hybrid reality: The role of digital twin technology. Internet Things 2024, 27, 101301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Du, R.; Abdelraouf, A.; Han, K.; Gupta, R.; Wang, Z. Driver digital twin for online recognition of distracted driving behaviors. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 3168–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, I.; Rohrmann, B. Subjective responses to simulated and real environments: A comparison. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.; Avons, S.E.; Meddis, R.; Pearson, D.E.; Ijsselsteijn, W. Using behavioral realism to estimate presence: A study of the utility of postural responses to motion stimuli. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2000, 9, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJsselsteijn, W.A.; de Ridder, H.; Freeman, J.; Avons, S.E. Presence: Concept, determinants, and measurement. In Human Vision and Electronic Imaging V; Rogowitz, B.E., Pappas, T.N., Eds.; SPIE Proceedings: San Jose, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 520–529. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrlitsias, C.; Michael-Grigoriou, D. Social interaction with agents and avatars in immersive virtual environments: A survey. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 2, 786665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.M.; Blascovich, J.J.; Beall, A.C. Immersive virtual environment technology as a basic research tool in psychology. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1999, 31, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weibel, R.P.; Grübel, J.; Zhao, H.; Thrash, T.; Meloni, D.; Hölscher, C.; Schinazi, V.R. Virtual reality experiments with physiological measures. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 138, 58318. [Google Scholar]

- Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; López-Tarruella Maldonado, J.; Llinares Millán, C. Psychological and physiological human responses to simulated and real environments: A comparison between photographs, 360° panoramas, and virtual reality. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 65, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Ma, L.; Zhang, W.; Salvendy, G.; Chablat, D.; Bennis, F. Predicting real-world ergonomic measurements by simulation in a virtual environment. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2011, 41, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Transfer of training from virtual to real baseball batting. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, S.; Rounds, J.D.; Kan, J.; Tripathi, V.; Cruz-Garza, J.G. Comparing physiological responses during cognitive tests in virtual environments vs. in identical real-world environments. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botden, S.M.B.I.; Jakimowicz, J.J. What is going on in augmented reality simulation in laparoscopic surgery? Surg. Endosc. 2009, 23, 1693–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, K.J.; Gagnon, D.J. Augmented reality integrated simulation education in health care. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2016, 12, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagavathula, R.; Williams, B.; Owens, J.; Gibbons, R. The reality of virtual reality: A comparison of pedestrian behavior in real and virtual environments. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2018, 62, 2056–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narciso, D.; Melo, M.; Rodrigues, S.; Dias, D.; Cunha, J.; Vasconcelos-Raposo, J.; Bessa, M. Assessing the perceptual equivalence of a firefighting training exercise across virtual and real environments. Virtual Real. 2024, 28, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.A. Driving in a Simulator Versus On-Road: The Effect of Increased Mental Effort While Driving on Real Roads and a Driving Simulator. Ph.D. Thesis, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Blaauw, G.J. Driving experience and task demands in simulator and instrumented car: A validation study. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 1982, 24, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dużmańska, N.; Strojny, P.; Strojny, A. Can simulator sickness be avoided? A review on temporal aspects of simulator sickness. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynne, R.A.; Beanland, V.; Salmon, P.M. Systematic review of driving simulator validation studies. Saf. Sci. 2019, 117, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, Y. Driving simulator validation studies: A systematic review. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2025, 138, 103020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, N.M.; Velaga, N.R.; Sharmila, R.B. Exploring behavioral validity of driving simulator under time pressure driving conditions of professional drivers. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 89, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnros, J. Driving behavior in a real and a simulated road tunnel—A validation study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 1998, 30, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, F. Validation of a driving simulator for work zone design. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2005, 1937, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldstra, J.L.; Bosker, W.M.; de Waard, D.; Ramaekers, J.G.; Brookhuis, K.A. Comparing treatment effects of oral THC on simulated and on-the-road driving performance: Testing the validity of driving simulator drug research. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 2911–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.J.; Laya, O. Drivers visual search in a field situation and in a driving simulator. In Vision in Vehicles VI; Gale, A.G., Brown, I.D., Haselgrave, C.M., Taylor, S.P., Eds.; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Kidlington, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Xu, S.; Ma, J.; Rong, J. The study of driving simulator validation for physiological signal measures. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 96, 2572–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milleville-Pennel, I.; Charron, C. Driving for real or on a fixed-base simulator: Is it so different? An explorative study. Presence 2015, 24, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, A.; Pulfer, B.; Tonella, P. Mind the gap! a study on the transferability of virtual versus physical-world testing of autonomous driving systems. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2022, 49, 1928–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakakis, G.; Grigoriadis, D.; Giannakaki, K.; Simantiraki, O.; Roniotis, A.; Tsiknakis, M. Review on psychological stress detection using biosignals. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2022, 13, 440–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klüver, M.; Herrigel, C.; Heinrich, C.; Schöner, H.-P.; Hecht, H. The behavioral validity of dual-task driving performance in fixed and moving base driving simulators. Transp. Res. Part FTraffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 37, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Krüger, H.-P.; Buld, S. Avoidance of Simulator Sickness by Training the Adaptation to the Driving Simulation; VDI Berichte: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2003; pp. 385–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Z.; Kang, C.; Wu, C.; Chai, C.; Shi, J.; Li, H. Promote or inhibit: An inverted U-shaped effect of workload on driver takeover performance. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2020, 21, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avetisyan, L.; Yang, X.J.; Zhou, F. Towards context-aware modeling of situation awareness in conditionally automated driving. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2025, 42, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Wang, Q.; Wang, K.; Song, X. Fatigue and distracted driving recognition method based on multimodal information fusion. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 83815–83827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, T.; Schmahl, C.; Wüst, S.; Bohus, M. Salivary cortisol, heart rate, electrodermal activity and subjective stress responses to the Mannheim multicomponent stress test (mmst). Psychiatry Res. 2012, 198, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C.; Lambertz, M.; Nelesen, R.; Bardwell, W.; Choi, J.-B.; Dimsdale, J. Effects of stress on heart rate complexity—A comparison between short-term and chronic stress. Biol. Psychol. 2009, 80, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, L.; Wdowczyk-Szulc, J.; Valenti, C.; Castoldi, S.; Passino, C.; Spadacini, G.; Sleight, P. Effects of controlled breathing, mental activity and mental stress with or without verbalization on heart rate variability. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 35, 1462–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clays, E.; De Bacquer, D.; Crasset, V.; Kittel, F.; De Smet, P.; Kornitzer, M.; Karasek, R.; De Backer, G. The perception of work stressors is related to reduced parasympathetic activity. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2011, 84, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthiesen, A.; Majgaard, G.; Scirea, M. The process of creating interactive 360-degree VR with biofeedback. In HCI International 2023 Posters; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Ntoa, S., Salvendy, G., Eds.; volume 1836 of Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Minen, M.; Gregoret, L.; Seernani, D.; Wilson, J. Systematic evaluation of driver’s behavior: A multimodal biometric study. In HCI International 2023 Posters; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Ntoa, S., Salvendy, G., Eds.; volume 1836 of Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli, A.; Lai, N.; Balali, V.; Heydarian, A. How are drivers’ stress levels and emotions associated with the driving context? a naturalistic study. J. Transp. Health 2023, 31, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucsein, W. Electrodermal Activity; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A.; Phoon, J.; Saha, S.; Dobbins, C.; Billinghurst, M. A neurophysiological approach for measuring presence in immersive virtual environments. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 474–485. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Kralj, A.; Moyle, B.; Li, Y. Developing 360-degree stimuli for virtual tourism research: A five-step mixed measures procedure. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2024, 26, 485–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llinares, C.; Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; Montañana, A. A comparative study of real and virtual environment via psychological and physiological responses. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebherr, M.; Mueller, S.M.; Schweig, S.; Maas, N.; Schramm, D.; Brand, M. Stress and simulated environments: Insights from physiological marker. Front. Virtual Real. 2021, 2, 618855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyitrai, T.; Virág, M. The effects of handling outliers on the performance of bankruptcy prediction models. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2019, 67, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumley, T.; Diehr, P.; Emerson, S.; Chen, L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2002, 23, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, S.G.; Kim, J.H. Central limit theorem: The cornerstone of modern statistics. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2017, 70, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg Hansen, K. Unpivoting columns to rows. In Practical Oracle SQL: Mastering the Full Power of Oracle Database; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Terumitsu, H.; Tetsuo, Y.; Tsuyoshi, T. Development of the driving simulation system Movic-t4 and its validation using field driving data. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2007, 12, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, N.; Theeuwes, J.; van der Horst, R. Driving simulator validity: Some considerations. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 1996, 1550, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godley, S.T.; Triggs, T.J.; Fildes, B.N. Driving simulator validation for speed research. Accid. Aanalysis Prev. 2002, 34, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultanow, E. Simulator vs. Real World. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/Sultanow/fh-hof/tree/main/simulator_vs_realworld (accessed on 15 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.