Abstract

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) is increasingly transforming creative industries through its ability to generate high-quality content, raising critical questions about authorship, ownership, and the future of creative labor. This paper addresses these challenges by conducting a systematic bibliometric review of 119 peer-reviewed articles on GenAI in the creative sectors, published between 2023 and 2025. The study applies PRISMA 2020 guidelines and keyword co-occurrence analysis using VOSviewer to identify thematic clusters and map research trends. The central research question is how the academic literature conceptualizes the role and impact of GenAI within creative industries and how this has evolved over time. Findings reveal nine major thematic areas, ranging from technical implementations to ethical, economic, and institutional perspectives. The analysis shows that recent research emphasizes not only the technological capacities of GenAI, but also its implications for value creation, creative agency, and industry structures. The main contribution of the paper lies in offering a structured overview of current research trajectories, clarifying conceptual ambiguities, and highlighting understudied areas—particularly regarding the intersection of GenAI, platform economies, and labor dynamics. The review also identifies a methodological gap in comparative empirical studies and proposes directions for future research. By mapping the evolving discourse on GenAI in creative industries, this study contributes to both scholarly understanding and policy development. It provides a foundation for interdisciplinary inquiry and a forward-looking agenda for critically assessing GenAI’s role in reshaping creative work.

1. Introduction

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has rapidly become a central force across industries due to its ability to autonomously generate text, images, video, and other creative outputs [1]. As these systems mature, their presence is particularly felt in domains where creativity, authorship, and originality were once considered uniquely human. The creative industries, spanning design, media, fashion, and advertising, are experiencing fundamental changes in how content is produced, evaluated, and monetized, due to the omnipresence of GenAI tools [2].

The adoption of GenAI in these sectors brings clear benefits: it reduces time spent on routine tasks, expands access to creative tools, and enables rapid ideation and prototyping. However, it also disrupts traditional models of creative labor and raises complex questions about intellectual property, human–AI collaboration, and the future of professional identity in creative work [3].

These tensions have sparked intense academic and public debate, as well as a growing body of research across disciplines. Scholars have examined how GenAI both augments and disrupts creative practices. For example, Ref. [4] demonstrates that AI-assisted collaboration can improve the quality of creative output but may reduce the diversity of ideas in group settings. In design-oriented research, Ref. [5] highlights that GenAI enables faster ideation and prototyping, yet it also introduces legal and ethical uncertainties, especially regarding intellectual property and algorithmic bias.

Beyond academia, public discourse reflects widespread concern among professionals about the unlicensed use of creative works in AI training datasets. A prominent example is the reaction of over 11,000 artists who publicly opposed the unauthorized use of their content to train GenAI systems [6]. These developments show that the impact of GenAI on creative work is not only technological but also social, legal, and deeply cultural, warranting integrative approaches across disciplines. To structure the interpretation of the findings, this review draws on theoretical perspectives from creative ecosystems, socio-technical systems, and platform economy theory. These frameworks offer complementary lenses for analyzing the evolving role of GenAI in creative production, institutional change, and value creation across digital platforms.

Despite growing academic interest in GenAI, only a limited number of systematic reviews have addressed its implications for the creative industries in a structured, interdisciplinary manner. Among the most relevant recent studies, Ref. [7] conducted a systematic review of 64 papers on generative artificial intelligence in creative contexts, focusing on the intersection of GenAI with creativity in art and music. However, this review addressed creative industries only marginally and did not frame them as systemic socio-technical environments. Ref. [8] offered a meta-analysis evaluating the effects of GenAI on creative performance, particularly originality and diversity, using terms such as “large language models” and “ideation.” While methodologically rigorous, their study did not explore sectoral transformations or structural dynamics. Ref. [9] presented a scoping review of GenAI applications among creative professionals, emphasizing empirical insights from design and media fields but without providing bibliometric or thematic mapping. In a broader technological review, Ref. [1] examined methods and applications of GenAI across multiple domains—focusing on technical advances such as transformers, diffusion models, and image synthesis—without thematically addressing creative industries. Ref. [10] explored GAN-enabled collaborative design tools, offering a technically rich discussion of visual design processes and human–computer interaction, though the paper lacked analysis of organizational or economic implications. These reviews provide valuable insights into specific aspects of GenAI and creativity, but none offer a structured, bibliometric, and thematically grounded synthesis of how GenAI is conceptualized and studied across the creative industries as a field. This paper aims to fill that gap.

Heigl [7] conducted a systematic review of 64 studies, primarily exploring how GenAI affects individual creative processes such as co-creation, digital aesthetics, and content generation, with a focus on human–AI interaction in design and media domains. Holzner et al. [8] conducted a meta-analysis examining the impact of GenAI tools on creative performance, particularly in terms of originality and idea diversity. However, they did not extend the analysis to sector-level implications. Tsao [9] conducted a scoping review of GenAI use in professional creative practice, mapping real-world applications by artists and designers and highlighting integration challenges. However, it remained primarily descriptive and lacked a structured bibliometric approach. Broader technical reviews, such as Sengar et al. [1], who analyze state-of-the-art GenAI techniques across domains, and Hughes et al. [10], who focus on the use of generative adversarial networks (GANs) in collaborative visual design, provide valuable insight into technological advances, but do not investigate the organizational, cultural, or economic transformations underway in the creative industries.

In brief, these studies mostly remain focused on individual creative processes or technical capabilities, rather than on the broader systemic changes affecting the structure, labor models, and institutional logic of the creative economy. Understanding these transformations is critical not only from a research perspective but also from policy, labor law, and educational standpoints.

As GenAI technologies become embedded in production processes, they reshape skill demands, disrupt established creative professions, and pose complex questions about copyright, attribution, and fair compensation [11,12]. Policymakers and educators require a clearer evidence base to anticipate these shifts and develop informed frameworks for regulation and curriculum development [13]. Moreover, the creative industries represent early examples of data-driven business ecosystems, in which value creation is increasingly shaped by algorithmic processes, platform economies, and hybrid workflows involving both human and machine agents [14]. In practical terms, this implies the emergence of new roles (e.g., prompt engineers, AI curators), reconfiguration of revenue models (e.g., platform-based monetization), and altered power relations between creators, platforms, and audiences [15]. In this study, creative industries are conceptualized as socio-technical ecosystems in which creative value emerges through the interaction of human creators, generative technologies, platform infrastructures, and audiences.

Despite the growing volume of research on GenAI in creative contexts, existing reviews predominantly focus on either technical developments or micro-level creative processes, offering limited insight into the broader structural and systemic transformations of the creative industries. In particular, there is a lack of integrative analyses that combine bibliometric mapping with a theoretically informed interpretation of how generative AI reshapes creative labor, organizational practices, and value creation mechanisms at the industry level.

The purpose of this study is to conduct a structured bibliometric analysis, combined with keyword co-occurrence analysis, of the literature on generative artificial intelligence in the creative industries to inform a future-oriented research agenda. Specific research objectives are as follows:

- RO1: To conduct a bibliometric analysis to investigate temporal trends, diversity across disciplines and countries, publication venues, document types, and the most influential publications on GenAI in the creative industries

- RO2. To map and visualize the density of research on GenAI in the creative industries

- RO3. To interpret the identified thematic clusters of research on GenAI in the creative industries

- RO4. To analyze the temporal evolution of research themes on GenAI in the creative industries

By addressing these objectives, this review makes three key contributions. First, it provides a structured, bibliometric overview of the rapidly expanding literature on generative AI in creative industries, offering transparency and reproducibility in line with PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Second, it advances a system-level perspective that complements existing micro-level and technology-focused reviews by foregrounding organizational, economic, and institutional dimensions. Third, it identifies underexplored research gaps and future directions, particularly concerning governance frameworks, labor transformation, and the long-term sustainability of creative ecosystems shaped by generative AI.

While several reviews have mapped the technical progress of GenAI in specific creative domains, few have adopted a systemic perspective that considers how GenAI reshapes institutional structures, labor dynamics, and platform governance in the creative industries. Existing reviews often focus narrowly on tool performance, artistic collaboration, or single-sector applications. This review addresses that gap by combining bibliometric mapping with thematic cluster analysis to examine how GenAI reconfigures creativity not only at the level of tools and practices but across broader socio-technical and economic systems.

2. Methodology

To systematically examine how GenAI is transforming the creative industries, we conducted a structured literature review integrating bibliometric and thematic methods. The methodological approach is detailed below.

2.1. Review Protocol

This study applies a systematic literature review (SLR) methodology to examine how GenAI is reshaping the creative industries. The review follows the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework, which provides a structured and transparent protocol for identifying, screening, and selecting relevant literature [16]. PRISMA is increasingly used in social sciences, business, and interdisciplinary research to enhance methodological rigor, minimize bias, and ensure replicability [17,18].

Given the multidimensional character of GenAI’s impact, which spans the creative industries along multiple dimensions, such as technology, creativity, labor, intellectual property, and organizational change, this review combines bibliometric analysis with thematic synthesis. Through bibliometric analysis [19], we capture structural patterns in a growing, fragmented field, such as GenAI deployment in the creative industries, analyzing the timeline of publications, authorship, publication venues, and citations. Thematic analysis is also used to conduct keyword co-occurrence analysis, identifying recurrent themes, conceptual clusters, and relationships among the core topics addressed in the literature.

2.2. Search Strategy, Screening, and Selection Process

The Scopus database was selected as the primary source for this review due to its comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed literature across fields relevant to this study, including business, management, the social sciences, the arts, and interdisciplinary studies [20].

The search was conducted in three stages in November 2025. Firstly, a Boolean query was developed to capture the intersection of GenAI and the creative industries. The search was applied to the title, abstract, and keywords fields, using the two sets of keywords. First, we used (i) keywords related to GenAI (“Generative Artificial Intelligence”, “Gen AI”, “Generative AI”), extended with names of commonly used GenAI tools in creative industries (“Midjourney”, “Stable Diffusion”, “ChatGPT”, “DALL-E”), and (ii) keywords reflecting the terminology used to describe creative industries (“Creative Industr*”, “Creative Sector*”, “Creative Business*”, “Creative Economy”). This approach yielded 146 documents. The specific GenAI tools, such as Midjourney, were selected because they are the most prominent generative platforms used in design, media, fashion, and content creation as of 2023–2025 [21]. Including platform-specific keywords ensures that applied, practice-driven studies are not missed due to purely generic indexing. Throughout the paper, the abbreviation “GenAI” is used as a standardized term, while full expressions (“Generative Artificial Intelligence”, “Generative AI”) appear only in formal contexts such as search queries, definitions, or cited paper titles.

Secondly, to ensure methodological rigor, the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied: (i) Language: only publications written in English were considered; (ii) Document types included: peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and book chapters; and (iii) Document types excluded: editorials, notes, errata, and books, due to their limited academic contribution or lack of peer review. This stage resulted in 136 documents.

The final stage was relevance-based screening of the retrieved papers to include a diverse yet coherent corpus of scholarly perspectives on GenAI in creative sectors and work. Titles and abstracts were assessed to determine if GenAI addressed creative practice, labor, cultural production, or business aspects of the industry. However, some technologically focused or artistically driven studies were also retained if they offered insights into creative processes or industry impact. Only publications that were clearly unrelated to creative domains or focused solely on technical model development without regard to creative production, industry practices, or socio-economic ramifications were removed. The screening process resulted in 119 papers.

This approach follows systematic review guidelines for fast-moving research topics, where overly restrictive criteria may prematurely remove relevant contributions and conceal emergent themes [22]. By deploying this angle, our review shows how GenAI is conceptualized and deployed across creative sectors, prioritizing thematic relevance over tight disciplinary boundaries. The selection process is summarized in Table 1, resulting in a final dataset of 119 publications, which are used as the basis for subsequent bibliometric mapping and thematic synthesis, presented in the following sections.

Table 1.

Overview of the search, screening, and selection process.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

Following the screening process, a final corpus of 119 publications was selected for complete analysis, which was conducted in two phases (Table 2). The combination of bibliometric and thematic analyses was employed, following the approach proposed by [23].

Table 2.

Overview of the data extraction and analysis process.

Firstly, the following information was extracted into a spreadsheet for the bibliometric analysis: author, document title, publication title, year of publication, author institutions and countries, financing bodies, paper abstract, author keywords, and Scopus keywords.

Secondly, the above-mentioned data were extracted in RIS format, which served as the basis for thematic analysis, conducted using VosViewer [24], a well-established tool for constructing and visualizing bibliometric networks. A minimum of 2 keyword occurrences per document was set, consistent with prior VOSviewer-based bibliometric analyses, such as [25].

As a further refinement step, generic umbrella terms with limited discriminative value (e.g., artificial intelligence, GenAI, creative industry, creative professionals, article) were excluded, as their high frequency and centrality tend to obscure finer-grained thematic structures. In addition, a thesaurus file was applied to consolidate synonymous and overlapping expressions. For example, highly generic terms such as “technology” or “algorithm” were removed, while more specific expressions like “text generation” or “image generation” were retained. Similarly, closely related variants (e.g., “AI-generated art” and “generative art”) were merged under a unified label to reduce redundancy. These preprocessing decisions enhance interpretive validity by improving thematic resolution and ensuring that detected clusters reflect substantively distinct research directions rather than frequency-driven noise. After these filtering and normalization procedures, the final set was curated to 115 keywords, which served as the basis for keyword co-occurrence analysis and cluster detection.

2.4. Methodological Reliability, Limitations, and Systemic Design

To ensure methodological transparency and minimize bias, all stages of the review process, identification, screening, selection, and analysis, were conducted independently by the authors and cross-checked through iterative discussion. The adoption of PRISMA 2020 guidelines reinforced replicability, analytical structure, and procedural clarity throughout the review protocol [16].

Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The decision to rely exclusively on the Scopus database, while justified by its robust and interdisciplinary coverage of peer-reviewed journals in business, management, the social sciences, and the arts, may have excluded relevant studies indexed in other databases such as Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, or the ACM Digital Library. Scopus was selected because it offers broader coverage of social science and creative industry journals compared to Web of Science and provides standardized metadata compatible with bibliometric tools such as VOSviewer. Including multiple databases would have substantially increased duplication and required a more complex deduplication protocol, which was beyond the scope of this review. Nevertheless, future research could benefit from integrating multiple databases to further enhance coverage and robustness.

This limitation is particularly relevant in fast-evolving domains such as AI governance, digital ethics, and creative technology, where emerging insights often appear in less traditionally indexed outlets or grey literature [26]. Another limitation concerns the language and document-type filters applied. While focusing on English-language peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and book chapters ensured quality and consistency, it may have excluded valuable contributions published in other languages or in non-traditional formats. In technical fields such as software engineering, grey literature reviews have been shown to offer significant insights [27,28]. However, this review focuses not on the technical implementation of GenAI, but on its broader implications for the creative industries.

3. Results

This chapter synthesizes the findings from the systematic review, combining bibliometric mapping and thematic analysis.

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

The bibliometric profile of the 119 selected publications reveals several structural trends that help understand the current state of research, focusing on temporal trends and emerging research interests, disciplinary and geographic diversity, and publication venues and document types, thus contributing to RO1.

3.1.1. Temporal Trends and Emerging Research Interest

The temporal distribution of publications indicates a rapid growth in scholarly attention to the topic. While only five relevant documents were published in 2023, the number increased sharply to 37 in 2024 and further to 76 in 2025, with an early publication already appearing in 2026. This exponential rise reflects the broader diffusion of GenAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Midjourney) into public and professional discourse during 2023–2025 [21], as well as increasing scholarly interest in their implications for creative labor, production, and value creation [11]. The temporal trend suggests that the field is currently in a formative phase, with a steep upward trajectory and growing academic momentum.

3.1.2. Disciplinary Diversity and Geographic Fragmentation

The reviewed publications span a wide range of subject areas, underscoring the interdisciplinary nature of the field (Table 3). The majority of papers are indexed under computer science (69), followed by social sciences (41), business, management, and accounting (22), and arts and humanities (21). Other contributing fields include engineering, economics, psychology, and decision sciences. This disciplinary dispersion highlights the multifaceted nature of the research domain, in which technological innovation intersects with the social, economic, and cultural dimensions of creative work.

Table 3.

Subject areas of published documents.

From a geographic perspective, the authorship of the analyzed publications reflects notable international diversity (Table 4). The most significant number of studies originated from China (18), the United States (17), and the United Kingdom (12), indicating strong research engagement from countries with advanced AI sectors. They are followed by India (10), Italy (9), and a group of Asia-Pacific and European countries, including Australia, Indonesia, and Spain, with six papers. A long tail of additional countries, with four or fewer publications, highlights growing global interest in the implications of generative AI for the creative industries, but with limited regional concentration.

Table 4.

Countries of document authors.

The institutional affiliations are similarly scattered, with no single institution contributing more than three papers. Only four authors published more than one paper within the sample. These findings point to a fragmented research landscape with no centralized scholarly community or dominant epistemic network at this stage.

3.1.3. Publication Venues and Document Types

The documents were published across a wide variety of sources, underscoring the lack of a clearly established outlet for research on GenAI and the creative industries. Only a few journals or conference proceedings published more than two papers on the topic. The most frequent venues include AI and Society (4 papers), ACM International Conference Proceedings (3 papers), and Media International Australia (3 papers). Other outlets such as Studies in Computational Intelligence, Communications in Computer and Information Science, and Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics appear only twice each.

By document type, journal articles account for 52 of the included papers, followed by conference papers (33) and book chapters (30). Only four review articles were found. The large share of conference papers and book chapters suggests that the field is still in an exploratory phase, with much of the output produced in early-stage or experimental formats. Such a distribution is typical for emerging research areas, where scholarly communities and publishing norms are still taking shape.

3.1.4. Most Influential Publications

Citation analysis reveals that, although the field is still emerging, several publications have already had a notable scholarly impact. Across the 119 reviewed documents, a total of 344 citations were recorded (as of December 2025), indicating that the academic conversation on generative AI in creative industries is gaining traction.

Table 5 presents the ten most cited papers, which together account for over 200 citations. These works predominantly focus on intellectual property issues, the augmentation of human creativity, ethical dilemmas, and user acceptance of generative AI technologies. The most cited article explores the legal implications of GenAI models [29]. At the same time, other influential works examine collaborative creativity [30], design challenges [31], and anxiety-related barriers to adoption [32].

Table 5.

Ten most cited publications.

3.2. Thematic Analysis

The thematic structure of the literature was derived through keyword co-occurrence analysis to identify dominant conceptual patterns and relationships within research on GenAI in the creative industries.

3.2.1. Density of Publications

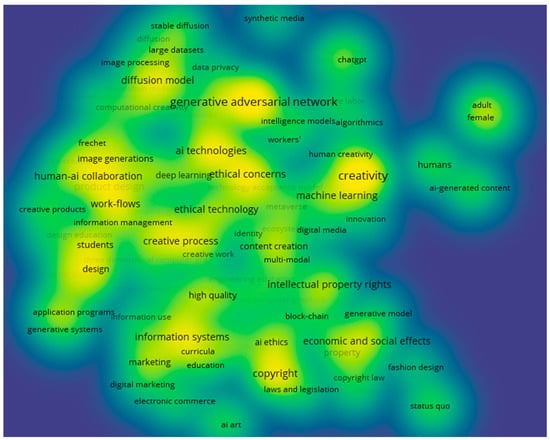

Figure 1 presents a density visualization of the keyword co-occurrence network, directly supporting RO2. The visualization indicates a relatively distributed density pattern, suggesting that the literature engages with a broad set of interrelated topics at comparable levels of prominence, such as generative adversarial networks, creativity and machine learning, intellectual property rights and copyright, information systems, diffusion models, human–AI collaboration, ethical concerns, and content creation.

Figure 1.

Density visualization of keywords related to generative AI in creative industries; Note: Figure represents the most frequent words. The list of all words is in the Table 6; Source: Authors’ work.

3.2.2. Thematic Clusters

Table 6 presents a structured overview of the identified thematic clusters, summarizing their representative keywords, average links, occurrences, and temporal dynamics. Detailed cluster information is presented in Appendix A. The interpretive labels for each cluster were derived using a combination of dominant keyword frequencies, semantic coherence among co-occurring terms, and their theoretical relevance to GenAI research in creative industries. This approach ensured that labels were not only data-driven but also contextually meaningful.

Table 6.

Overview of thematic clusters derived from keyword co-occurrence analysis.

C1: Organizational, market, and decision contexts. The first cluster captures how generative AI transforms market dynamics, managerial decisions, and information systems within creative sectors. Keywords such as “decision making,” “electronic commerce,” and “cultural and creative industry” reflect a focus on AI-driven shifts in business models, employment structures, and platform economies. Studies examine the impact of GenAI on platform governance [30], marketing personalization and consumer targeting [39], labor precarity and automation risks [29], and strategic adaptation in creative firms [40]. Collectively, these contributions signal a move toward systemic integration of GenAI in organizational workflows and market-facing activities.

C2: Ethical, legal, and socio-economic implications. The second cluster focuses on how generative AI challenges existing norms around authorship, copyright, and cultural labor. Studies explore the legal ambiguity of AI-generated content [41], ethical tensions in creative professions [42], and the use of blockchain to secure authorship rights [43]. Others examine how GenAI affects diversity and control in creative outputs, raising concerns about the commodification of artistic expression [44]. Together, these works point to a growing need for adaptive regulation and new ethical frameworks.

C3: Human–AI collaboration and professional workflows. The third cluster focuses on the evolving interaction between humans and generative AI in professional and creative environments. Keywords such as “workflows,” “human–AI collaboration,” and “employment” point to shifting task boundaries, skill demands, and co-creation processes. Studies examine how GenAI tools are integrated into everyday practices in the cultural and creative sectors [45], how they affect autonomy and identity in creative labor [46], and the tensions that emerge between automation and authorship [47,48]. These insights reveal that collaboration with GenAI is not only technical but deeply embedded in professional values and institutional routines.

C4: Generative model technologies and diffusion-based methods. This cluster centers on the technical evolution and application of foundational generative models, including diffusion architectures, large language models, and deep learning. The literature focuses on their creative potential [49], use in media-specific domains such as anime and cultural heritage [50,51], and the mechanisms by which they produce novelty and divergence in generated content [52]. These studies examine not only model performance but also conceptual questions about how creativity and control are embedded in algorithmic systems, raising new ethical and epistemological concerns.

C5: Applied design practice and creative production. This cluster examines how generative AI supports creative tasks in design education, ideation, and visual development. Studies explore its integration into classroom settings and personalized learning for design students [53], its role in augmenting ideation quality and speed [54], and its application in character and concept design workflows [55,56]. These contributions position GenAI as a practical co-creator that enhances visual output while reshaping traditional creative processes and skill development.

C6: Creativity and human-centered perspectives. The sixth cluster explores how generative AI intersects with human creativity, emotional perception, and ethical reflection. Studies examine how users perceive and evaluate AI-generated versus human-created content [57], how GenAI influences individual creative processes and self-expression [58,59], and how these systems affect emotional engagement and authorship in domains such as music and film [60]. Together, these works highlight the need to assess not only what GenAI can create but also how it transforms the human experience of creativity.

C7: Adoption, learning systems, and content-creation ecosystems. This cluster focuses on the systemic embedding of GenAI into digital production environments, emphasizing the infrastructural and ecosystem-level conditions for adoption. Unlike clusters centered on creativity or collaboration, here the emphasis is on technology integration, adaptive deployment, and multimodal capabilities in content generation workflows. Studies analyze the role of AIGC (AI-generated content) platforms in shaping industry-wide adoption patterns [61], how culturally adaptive frameworks guide responsible integration [62], and how GenAI tools enable real-time, high-quality content creation across formats such as text, images, and video [63,64]. These works underline the transition from experimental use to operational normalization of GenAI within digital content ecosystems.

C8: Platformed GenAI applications and creative labor. This cluster explores how generative AI technologies are embedded in platform-based creative economies and how they reconfigure labor, authorship, and artistic identity. Studies in this group examine the shifting boundaries of creative control in digital art [65], the spatial and semantic logic of creativity under AI systems [66], and the role of machine learning in extending or displacing human input in creative enterprises [67,68]. Unlike clusters focused on technical infrastructure or collaboration, C8 centers on how platform logics and algorithmic mediation redefine what counts as creativity, who produces it, and under which conditions.

C9: Model architectures and evaluation for synthetic media. The final cluster focuses on the development, refinement, and evaluation of generative model architectures, particularly GANs, autoencoders (neural networks used to compress and reconstruct input data, often applied in image generation), and diffusion models, for creating synthetic visual content. Studies investigate interactive co-creation using StyleGAN [69], model performance in fashion design applications [70], and the use of pedagogical environments to teach image generation techniques [71]. Emphasis is also placed on the role of metrics such as Fréchet Inception Distance in assessing output quality [72]. The cluster reflects a strong methodological orientation, bridging creative experimentation with robust model benchmarking.

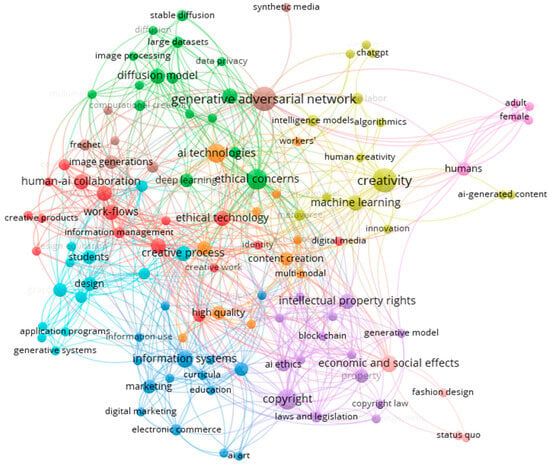

Figure 2 presents the cluster visualization derived from keyword co-occurrence analysis and illustrates the internal structure and relational logic of the research field, contributing to RO3. The visualization reveals clusters related to creative practices, technological foundations, ethical and legal issues, and organizational contexts.

Figure 2.

Cluster visualization of thematic structure; Notes: Membership of the specific word to the cluster has been indicated by the specific colour. The figure represents the most frequent words. The list of all words is in Table 6; Source: Authors’ work.

3.2.3. Temporal Trends of Publications

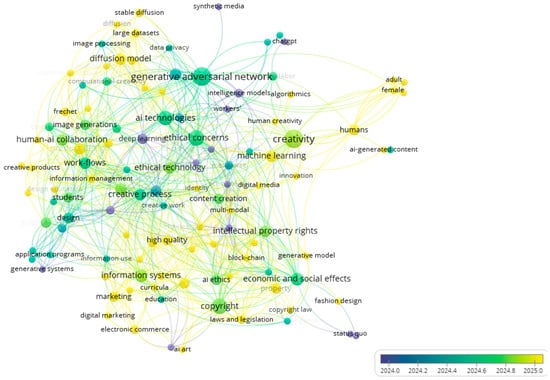

Figure 3 presents an overlay visualization based on the average publication year of keywords, contributing to RO4. Earlier research (2023–early 2024) is primarily focused on technical concepts such as deep learning, image generation, and diffusion models, reflecting initial interest in GenAI’s capabilities and mechanisms. Publications from mid-2024 onward increasingly engage with applied contexts, including design workflows, human–AI collaboration, and creative processes. The most recent contributions (late 2024–2025) emphasize broader contextual terms such as employment, decision-making, and information systems, suggesting growing attention to the organizational, market, and societal implications. This progression points to a gradual broadening of the research agenda—from model-level analysis toward systemic and institutional perspectives.

Figure 3.

Overlay visualisation of average publication year. Note: The figure represents the most frequent words. The list of all words is in the Table 6. Source: Authors’ work.

Taken together, the presented analyses demonstrate that research on generative AI in the creative industries is rapidly expanding, conceptually diverse, and increasingly oriented toward broader socio-economic and institutional questions, while still anchored in a strong technological core.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Summary of Research

This paper presents a structured synthesis of the emerging literature on GenAI in the creative industries, covering the period from 2023 to 2025. All research objectives outlined in the introduction were systematically addressed: RO1 through temporal and disciplinary bibliometric analyses; RO2 and RO3 through keyword co-occurrence mapping and cluster detection; and RO4 through tracking the temporal evolution of research themes. By applying bibliometric techniques and thematic keyword analysis to a curated set of Scopus-indexed publications, the review identifies key research domains, evolving trends, and conceptual relationships. The analysis highlights nine thematic clusters, ranging from technical model development and design practices to legal frameworks, labor dynamics, and organizational adaptation. The presented results enable a clearer understanding of how generative AI is reshaping the creative ecosystem at the levels of tools, workflows, institutions, and markets.

4.2. Theoretical Contributions and Research Agenda

This review makes three distinct contributions to the literature on GenAI in the creative industries, addressing conceptual, methodological, and agenda-setting levels.

At the conceptual level, it advances prior literature reviews on creativity and GenAI by repositioning creativity from an individual- or task-level outcome [7,8] to a systemic property of creative ecosystems. Rather than treating generative AI primarily as a creativity-enhancing tool, the review conceptualizes creativity as increasingly shaped by organizational arrangements, platform logics, and data-driven infrastructures. This shift broadens existing creativity-focused accounts toward a more contextualized understanding of creative production.

At the methodological level, the review extends research on professional creative practice and workflows [9] by embedding human–AI collaboration within organizational and labor structures. While earlier studies focused on how creative professionals use GenAI, this review highlights how such use is conditioned by changing employment relations, emerging roles, and institutional constraints. In doing so, it connects micro-level collaboration dynamics with meso-level organizational transformation.

At the agenda-setting and policy-relevant level, the review complements technically oriented surveys of generative models and applications [1,10] by introducing market, governance, and decision-making contexts as integral components of the theoretical landscape. By identifying clusters related to platform governance, value redistribution, and strategic decision-making, the review expands the analytical scope of GenAI research beyond performance and architecture toward economic and policy-relevant dimensions.

Building on the contributions summarized in Table 7, we formulate a forward-looking research agenda in areas that remain theoretically underdeveloped or empirically overlooked.

Table 7.

Theoretical positioning of this review in relation to the existing literature.

Table 8 summarizes the proposed research agenda by aligning specific gaps with the broader theoretical domains introduced earlier. Each entry captures a concise research direction, offering a question-driven structure supported by appropriate methodological suggestions and data types. The final two columns clarify how each direction builds on the review’s theoretical contributions and its practical relevance for future academic, policy, or industry initiatives.

Table 8.

Research agenda.

We have derived a research agenda through an integrative process: the thematic cluster analysis revealed underexplored areas; these were cross-referenced with gaps in the existing literature (as discussed in Table 7) and then formulated into actionable, theoretically grounded research questions. In doing so, the agenda provides a structured foundation for advancing both scholarly inquiry and real-world applications in the evolving landscape of generative AI in the creative industries.

In the creativity domain, future studies are encouraged to move beyond isolated task-level assessments and investigate how platform infrastructures and data biases shape creative outcomes and cultural representation. Within the workflow domain, empirical work is needed to unpack the organizational and labor conditions that enable or constrain meaningful human–AI collaboration, particularly in dynamic or precarious creative sectors. Finally, in the technical model’s domain, research should not only track architectural progress but also interrogate the redistribution of value, legal accountability, and geographical disparities emerging from AI deployment. In particular, the analysis reveals geographic asymmetries in both research production and platform ownership, with institutions and companies based in North America and parts of East Asia dominating publication output, funding, and infrastructure development. This imbalance raises concerns regarding language representation, cultural diversity, and the applicability of GenAI tools across underrepresented regions. Without intentional strategies for inclusion, such asymmetries may reinforce epistemic inequality and limit the global relevance of creative AI research. By addressing these dimensions, future research can build a more holistic and practically relevant understanding of how generative AI reconfigures the creative industries—not just technologically, but structurally and systemically.

4.3. Practical Implications

The findings of this review are intended to support a wide range of stakeholders navigating the integration of generative AI into creative domains. Table 9 maps relevant actors to typical decision domains and how this study’s findings can inform their choices.

Table 9.

Intended audience and corresponding use cases.

The following groups of stakeholders may benefit from the results of this literature review in the following manner:

- Academic researchers may use the synthesized cluster structure and research agenda to target underexamined intersections between creativity, labor, and technology. The agenda highlights the need for longitudinal, comparative, and experimental designs that move beyond tool-focused studies and toward institutional, cultural, and socio-technical contexts.

- Policymakers and regulators are confronted with rapidly evolving challenges related to copyright, data ownership, and fair compensation in creative ecosystems. This review’s focus on data licensing regimes, value redistribution, and the role of GenAI in labour dynamics provides a conceptual basis for designing adaptive and inclusive regulatory frameworks that reflect new modes of content generation and distribution.

- Industry managers, particularly in media, design, advertising, and fashion, face decisions about integrating GenAI into production workflows and organizational strategies. The review identifies key considerations, including organizational readiness, emerging hybrid roles, and capability development. These insights can support strategic investments in technology adoption, workforce training, and cross-functional team restructuring.

- Educational institutions can draw from the identified shifts in creative labour and the emerging importance of human–AI collaboration to redesign curricula, emphasize interdisciplinary learning, and prepare students for future roles that blend creative intuition with algorithmic co-creation.

- Professional associations and labour unions are increasingly tasked with representing workers whose roles are being transformed by automation and augmentation. The findings related to job mobility, hybrid workflows, and institutional change can inform advocacy strategies, standard-setting, and skills certification frameworks.

These implications reflect the systemic nature of GenAI integration, emphasizing the need for cross-sectoral coordination and ongoing evaluation of unintended consequences. These implications illustrate how the findings on GenAI-driven thematic clusters translate into tangible economic and regulatory concerns, particularly regarding authorship rights, platform monetization, and algorithmic transparency in creative ecosystems.

4.4. Concluding Remarks

This review contributes to a more integrated understanding of how GenAI is reshaping the creative industries, not only by enhancing individual creativity or technical performance but by transforming the institutional, organizational, and economic contexts in which creative production occurs. Through the combination of bibliometric mapping and thematic co-occurrence analysis, it identifies emerging intellectual directions and clusters that signal a broader paradigm shift—from tool-centred inquiry to system-level theorizing.

While this synthesis captures current developments across 2023 to 2025, it is necessarily constrained by the publication window and database scope. Future reviews may benefit from including additional corpora such as grey literature, policy reports, or sector-specific white papers to better capture practice-led innovation and regulatory dynamics. Moreover, as generative AI technologies continue to evolve rapidly, longitudinal and comparative studies will be essential to understand their sustained impact across different creative sectors and regions.

Taken together, the findings and proposed research agenda are intended to inform scholarly work, guide strategic decision-making in industry and education, and support more inclusive and future-oriented policy development in the era of generative creativity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., M.P.B. and T.B.; methodology, M.B., M.P.B. and T.B.; software, M.B.; validation, M.P.B. and T.B.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B.; data curation, M.P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.P.B. and T.B.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, M.P.B. and T.B.; project administration, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Detailed cluster information.

Table A1.

Detailed cluster information.

| Label | Cluster | Links | Total Link Strength | Occurrences | Avg. Pub. Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ai art | 1 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| ai tools | 1 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| behavioral research | 1 | 11 | 11 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| case-studies | 1 | 12 | 14 | 4 | 2025.00 |

| computer music | 1 | 13 | 13 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| cultural and creative industry | 1 | 15 | 15 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| curricula | 1 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| decision making | 1 | 21 | 21 | 4 | 2025.00 |

| digital marketing | 1 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| education | 1 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| electronic commerce | 1 | 14 | 17 | 3 | 2025.00 |

| engineering education | 1 | 11 | 11 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| fashion design | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2025.50 |

| information systems | 1 | 30 | 36 | 6 | 2024.83 |

| information use | 1 | 12 | 13 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| labour market | 1 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2024.00 |

| marketing | 1 | 16 | 20 | 4 | 2025.00 |

| social sciences computing | 1 | 13 | 13 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| ai ethic | 2 | 17 | 18 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| ai ethics | 2 | 19 | 20 | 4 | 2024.75 |

| automation | 2 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| block-chain | 2 | 18 | 19 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| copyright | 2 | 25 | 32 | 9 | 2024.67 |

| copyright infringement | 2 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| copyright law | 2 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| economic and social effects | 2 | 26 | 28 | 6 | 2024.67 |

| entertainment industry | 2 | 19 | 19 | 2 | 2024.00 |

| generative model | 2 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| intellectual property rights | 2 | 18 | 20 | 5 | 2024.80 |

| interactive computer graphics | 2 | 20 | 21 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| laws and legislation | 2 | 22 | 26 | 3 | 2025.00 |

| property | 2 | 23 | 26 | 4 | 2025.00 |

| status quo | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2024.00 |

| utaut | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2024.00 |

| visual languages | 2 | 16 | 18 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| co-creation | 3 | 10 | 13 | 3 | 2024.67 |

| creative products | 3 | 10 | 11 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| creative work | 3 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| cultural industries | 3 | 12 | 12 | 3 | 2024.67 |

| digital media | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| digital technologies | 3 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| education computing | 3 | 11 | 11 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| employment | 3 | 19 | 19 | 3 | 2025.00 |

| human computer interaction | 3 | 33 | 36 | 5 | 2024.80 |

| human engineering | 3 | 11 | 12 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| human-ai collaboration | 3 | 9 | 12 | 5 | 2024.80 |

| identity | 3 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| information management | 3 | 19 | 20 | 3 | 2025.00 |

| metaverse | 3 | 12 | 12 | 3 | 2024.33 |

| new forms | 3 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| product design | 3 | 21 | 24 | 5 | 2025.00 |

| work-flows | 3 | 17 | 23 | 5 | 2024.60 |

| arts computing | 4 | 16 | 17 | 3 | 2025.00 |

| computational creativity | 4 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2024.67 |

| data privacy | 4 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| deep learning | 4 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 2024.00 |

| diffusion | 4 | 10 | 12 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| diffusion model | 4 | 18 | 20 | 5 | 2025.00 |

| ethical concerns | 4 | 37 | 47 | 9 | 2024.67 |

| foundation models | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| image processing | 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| large datasets | 4 | 14 | 18 | 3 | 2025.00 |

| large language models | 4 | 14 | 15 | 5 | 2024.40 |

| multimedia systems | 4 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| neural-networks | 4 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| stable diffusion | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2025.00 |

| user experience | 4 | 11 | 11 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| virtual reality | 4 | 13 | 14 | 3 | 2024.33 |

| application programs | 5 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| artificial intelligence tools | 5 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| blending | 5 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| creative process | 5 | 16 | 16 | 5 | 2024.60 |

| design | 5 | 19 | 20 | 4 | 2024.50 |

| design education | 5 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| design tool | 5 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 2024.33 |

| generative systems | 5 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2024.00 |

| graphic design | 5 | 20 | 22 | 4 | 2024.75 |

| graphic designers | 5 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| students | 5 | 13 | 15 | 4 | 2024.75 |

| three dimensional computer graphics | 5 | 13 | 14 | 3 | 2024.00 |

| visual design | 5 | 19 | 19 | 3 | 2025.00 |

| adult | 6 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| ai-generated content | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| creativity | 6 | 28 | 32 | 13 | 2024.84 |

| ethical technology | 6 | 20 | 22 | 5 | 2024.80 |

| female | 6 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| humans | 6 | 11 | 16 | 4 | 2025.00 |

| innovation | 6 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| machine learning | 6 | 16 | 17 | 5 | 2025.00 |

| male | 6 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| platform | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| young adult | 6 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| ai technologies | 7 | 22 | 26 | 8 | 2024.63 |

| content creation | 7 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 2024.75 |

| ecosystems | 7 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2024.00 |

| high quality | 7 | 13 | 15 | 4 | 2025.00 |

| learning algorithms | 7 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| learning systems | 7 | 19 | 21 | 4 | 2024.25 |

| multi-modal | 7 | 11 | 11 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| multimedia contents | 7 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2023.50 |

| technology acceptance model | 7 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2024.00 |

| text images | 7 | 10 | 11 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| workers’ | 7 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2024.00 |

| algorithmics | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| chatgpt | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2024.00 |

| creative labor | 8 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 2024.67 |

| digital art | 8 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| generative ai art | 8 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| generative artificial intelligence (genai) | 8 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| human creativity | 8 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| intelligence models | 8 | 10 | 11 | 3 | 2024.00 |

| websites | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| auto encoders | 9 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2024.50 |

| frechet | 9 | 15 | 17 | 3 | 2025.00 |

| frechet inception distance | 9 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 2025.00 |

| generative adversarial networks | 9 | 32 | 39 | 13 | 2024.62 |

| image enhancement | 9 | 13 | 15 | 3 | 2024.67 |

| image generations | 9 | 20 | 21 | 4 | 2024.75 |

| synthetic media | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2024.00 |

References

- Sengar, S.S.; Hasan, A.B.; Kumar, S.; Carroll, F. Generative artificial intelligence: A systematic review and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 23661–23700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneadza, J.S.; Arku, Z.; Kumi, D.K.; Boateng, S.L.; Boateng, R. AI and Content Creation Research: A Snapshot of What We Know and What We Don’t Know. In AI and the Creative Economy; Boateng, R., Boateng, S.L., Anning-Dorson, T., Penu, O.K.A., Eds.; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, O.; Karayel, D. Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) in Business: A Systematic Review on the Threshold of Transformation. J. Smart Syst. Res. 2024, 5, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnaou, A.; El Asri, H. Artificial Intelligence and Collaborative Learning: Impacts on Creativity, Critical Thinking, and Problem-Solving. J. Educ. Res. Pract. 2025, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poth, A.; Wildegger, A.; Levien, D.A. Considerations about integration of GenAI into products and services from an ethical and legal perspective. In European Conference on Software Process Improvement; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Times. 11,500 Artists Decry Unlicensed Use of Their Work to Train AI, 2025. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/11500-artists-decry-unlicensed-use-of-their-work-to-train-ai-mz862dz3t (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Heigl, R. Generative artificial intelligence in creative contexts: A systematic review of research themes and future directions. J. Innov. Entrep. 2025, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzner, M.; Dumpert, F.; Martens, J. Generative AI and creativity: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, J.; Liang, C.X.; Nogues, C.; Wong, A. Perceptions and integration of generative artificial intelligence in creative practices and industries: A scoping review and conceptual model. AI Soc. 2025, 92, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.T.; Zhu, L.; Bednarz, T. Generative adversarial networks–enabled human–artificial intelligence collaborative applications for creative and design industries: A systematic review of current approaches and trends. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 4, 604234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bughin, J.; Seong, J.; Manyika, J.; Chui, M.; Joshi, R. Notes from the AI Frontier: Modeling the Impact of AI on the World Economy; McKinsey Global Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/artificial-intelli-gence/notes-from-the-ai-frontier-modeling-the-impact-of-ai-on-the-world-economy#/ (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Floridi, L.; Chiriatti, M. GPT-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds Mach. 2020, 30, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancela-Outeda, C. The EU’s AI act: A framework for collaborative governance. Internet Things 2024, 27, 101291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Generative AI and the SME Workforce: New Survey Evidence 2025. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/generative-ai-and-the-sme-workforce_2d08b99d-en.html (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Kornberger, M.; Pflueger, D.; Mouritsen, J. Evaluative infrastructures: Accounting for platform organization. Account. Organ. Soc. 2017, 60, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borji, A. Generated Faces in the Wild: Quantitative Comparison of Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and DALL-E 2. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.00586. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2020, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosa Del Vasto, P.M.; Arco Castro, M.L. Artificial intelligence (AI) in sustainable tourism: Bibliometric analysis. Cuad. Tur. 2024, 53, 157–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boell, S.K.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. On being ‘systematic’ in literature reviews in IS. J. Inf. Technol. 2015, 30, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mao, R.; Huang, H.; Dai, Q.; Zhou, X.; Shen, H.; Rong, G. Processes, challenges and recommendations of Gray Literature Review: An experience report. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 137, 106607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, A.; Fatima, R.; Wen, L.; Afzal, W.; Azhar, M.; Torkar, R. On using grey literature and google scholar in systematic literature reviews in software engineering. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 36226–36243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesterman, S. Good models borrow, great models steal: Intellectual property rights and generative AI. Policy Soc. 2025, 44, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, K.; Horvát, E.Á. Extending human creativity with AI. J. Creat. 2024, 34, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jang, E.; Ma, F.; Wang, T. Generative AI in the Wild: Prospects, Challenges, and Strategies. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; Volume 747, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Han, B.; Ryu, S.; Hua, M. Acceptance of Generative AI in the Creative Industry: Examining the Role of AI Anxiety in the UTAUT2 Model. In HCI International 2023–Late Breaking Papers; HCII 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Degen, H., Ntoa, S., Moallem, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; p. 14059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschelli, G.; Musolesi, M. On the creativity of large language models. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 3785–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis Bueno, C.; Chow, P.-S.; Popowicz, A. Not “what”, but “where is creativity?”: Towards a relational–materialist approach to generative AI. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgadir Mohamed, Y.; Mohamed, A.H.H.M.; Khanan, A.; Bashir, M.; Adiel, M.A.E.; Elsadig, M.A. Navigating the ethical terrain of AI-generated text tools: A review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 197061–197120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, E.A.; Yamakawa, M.; Miwa, K. Human bias in evaluating AI product creativity. J. Creat. 2024, 34, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongmeensuk, S. Rethinking copyright exceptions in the era of generative AI: Balancing innovation and intellectual property protection. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2024, 27, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, K. AI and work in the creative industries: Digital continuity or discontinuity? Creat. Ind. J. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, G.; Vandi, A. Towards Synthetic Imaginaries: Augmenting Fashion Product, Communication, and Retail Design with GAI. In International Conference on Fashion Communication: Between Tradition and Future Digital Developments; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilirò, D. Generative Artificial Intelligence, Creativity, and Innovation. In The Generative AI Impact: Reframing Innovation in Society 5.0; Crupi, A., Marinelli, L., Cacciatore, E., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Leeds, UK, 2025; pp. 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J. Painting in gray: The legal and ethical ambiguities of AI-generated art. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2025, 23, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senftleben, M. Copyright data improvement for AI licensing: The role of content moderation and text and data mining rules. In A Research Agenda for EU Copyright Law; Bonadio, E., Sganga, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, B.P.; Kshetri, N.; Sharma, S.R.; Paudel, S.R.; Baral, S. blockAuth: A Blockchain-Driven Framework for Verifiable Content Creation and Secure Distribution in the Generative AI Era. In Securing AI-Generated Media with Blockchain Technologies; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2026; pp. 99–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; He, J. Impacts of Generative AI on Style Diversity in Graphic Design Based on Deep Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2nd Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area International Conference on Digital Economy and Artificial Intelligence, Dongguan China, 28–30 March 2025; pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kes-Erkul, A. Positioning AI in Creative Industries: Challenges and Opportunities for Workforce. In Artificial Intelligence Technical and Societal Advancements; Kose, U., Demirezen, M.U., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, X. A Study on the Pathways of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) Collaborating with Cultural and Creative Product Innovation Design Driven by New-Form Productivity. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Education, Knowledge and Information Management, Cambridge, UK, 20–22 June 2025; pp. 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalsgaard, P. GenAI and the crisis of creative labor: Automation, augmentation, and the artist’s role. In Adjunct Proceedings of the Sixth Decennial Aarhus Conference: Computing X Crisis, Aarhus, Denmark, 18–22 August 2025; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohedas, S.D.; Alcarria, F.J. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Media Production. The Emerging Role of Artificial Intelligence Artist in Spain. Comun. E Soc. 2025, 47, e025011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-C. (B). Unlocking creativity with artificial intelligence (AI): Field and experimental evidence on the Goldilocks (curvilinear) effect of human–AI collaboration. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2025, 154, 3294–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.C.; Luo, S.N.; Fan, L.; Dai, C. Leveraging AI and diffusion models for anime art creation: A study on style transfer and image quality evaluation. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2025, 22, 1131–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micalizzi, A. Creating the “new” and the “different”: The making of novelty in diffusion-based AI systems. In Computational Arts and Creative Products Languages Spaces and Practices; Micalizzi, A., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Wang, E.; Arshad, M. Design of personalized creation model for cultural and creative products based on evolutionary adaptive network. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowar, S.; Mukhopadhayay, N.D. Generative AI Is Changing Personalized Learning to Help Us Build a Sustainable Future. In Generative AI Approaches to Sustainable Development in Higher Education; Meletiadou, E., Ed.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: New York, New York, USA, 2025; pp. 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavletich, C. Assessing Quality of AI-Assisted Ideation: A Study in Graphic Design Education. In Artificial Intelligence in Vocational Education and Training; Chan, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztaş, Y.E.; Arda, B. Re-evaluating creative labor in the age of artificial intelligence: A qualitative case study of creative workers’ perspectives on technological transformation in creative industries. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 4119–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tan, Z.; Ma, Y. Combinediff: A GenAI creative support tool for image combination exploration. J. Eng. Des. 2025, 36, 731–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fišer, N.; Martín-Pascual, M.Á.; Andreu-Sánchez, C. Emotional impact of AI-generated vs. human-composed music in audiovisual media: A biometric and self-report study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerny, M. Creativity, Artificial Intelligence and (Neo-) Romantic Implicit Religion. Acta Inform. Pragensia 2025, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Kim, S.; Chen, Y. Generative AI visual creativity system combined with knowledge retrieval. J. Comput. Methods Sci. Eng. 2025, 14727978251346065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzarelli, A.; Anantrasirichai, N.; Bull, D.R. Intelligent Cinematography: A review of AI research for cinematographic production. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Hai-Yan, X.; Yi-Linkg, X.; Shao-Ju, L. Comparative Analysis of AIGC Software Applications in Apparel Design. In Proceedings of the 18th Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Symposium Proceedings (TBIS 2025), Hangzhou, China, 17–20 August 2025; pp. 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, G. Culturally Adaptive Integration of Generative AI in Film Production and Education. In Proceedings of the 2025 7th International Conference on Internet of Things, Automation and Artificial Intelligence (IoTAAI), Guangzhou, China, 25–27 July 2025; pp. 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohedas, S.D.; Alcarria, F.J. The integration of generative artificial intelligence in the audiovisual post-production workflow. Prism. Soc. 2025, 48, 96–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.; Kishor Kumar Reddy, C.; Manoj Kumar Reddy, D.; Hanafiah, M.M. Single Modality to Multi-modality: The Evolutionary Trajectory of Artificial Intelligence in Integrating Diverse Data Streams for Enhanced Cognitive Capabilities. In Multimodal Generative AI; Singh, A., Singh, K.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhisree, C.; Paul, A.; Venunadh, A.; Bhowmick, R.S. Generative AI Under Scrutiny: Assessing the Risks and Challenges in Diverse Domains. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Cybernetics, Cognition and Machine Learning Applications (ICCCMLA), Hamburg, Germany, 19–20 October 2024; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoryk, A.; Antipina, I.; Havrosh, O.; Shunevych, Y.; Shvets, V. Machine thinking and human imagination: New horizons for creativity in the digital age. Int. J. Cult. Hist. Relig. 2025, 7, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdvibulvech, C. Machine Learning-Driven Extended Creativity for Reshaping Traditional Artistic Pieces. In Machine Learning and Soft Computing. ICMLSC 2025. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Huang, L., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 2487, pp. 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bansal, R.; Liang, J. Generative AI in Artistic Enterprises: A Semantic Web Approach to Automated Painting Creation. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. IJSWIS 2025, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, M.C.; Manongga, D.; Hendry, H.; Bayu, T.I. Interactive Co-Creation with StyleGAN for Enhancing Visual Design Using Generative AI. In 2025 4th International Conference on Creative Communication and Innovative Technology (ICCIT), Kota Cirebon, Indonesia, 15–16 August 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Kowshik, B.S.; Hasita, Y.; Santhanalakshmi, S.; Baba, N.Y. Revolutionizing Fashion: Exploring GAN’s Creative Potential for Style Enhancement. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Computing and Communication Networks. ICCCN 2024; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Kumar, A., Swaroop, A., Shukla, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; p. 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudillo, M. Transforming Perceptions: Pedagogical Efficacy of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Art-Tech Education. In Artificial Intelligence in Education Technologies: New Development and Innovative Practices (AIET 2024); Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies; Schlippe, T., Cheng, E.C.K., Wang, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; p. 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthana, M.; Sejana, R.; Krishnakumar, H.; Priya, D.K. The Essential Concepts of Generative AI Democratization. In Democratized Generative AI: Principles, Challenges and Applications; Balasubramaniam, S., Kadry, S., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 35–67. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.