1. Introduction

In recent times, there has been an increasing number and severity of emergencies, including natural disasters, industrial accidents, and significant public safety incidents [

1,

2,

3].These events create immense pressure on emergency management systems to ensure decision-making that is precise, quick, and reliable under conditions of uncertainty, variation, time pressure and minimal resources [

4,

5,

6]. Typically, researchers use static, rule-based decision logic to provide manual triage protocols or dispatch based on heuristics [

7,

8]. However, they may struggle to adapt to dynamic and demanding environments [

5]. To further emphasise the need for an optimised calculation logic, real-life emergency information is required. An analysis of the 911 Emergency Calls dataset, containing more than 500,000 records, shows that learning-based decision logic reduces response time by approximately 2.1 min (≈18%) compared to conventional rule-based dispatch mechanisms. The reported improvement is statistically significant (

p < 0.01, paired

t-test). That is, even small changes to internal decision-making logic can yield considerable operational benefits in time-critical emergencies [

9,

10,

11]. According to Su et al. (2022), emergency decision-making (EDM) has evolved into a multidisciplinary task that draws on mathematics, information systems, public management, and psychology [

10]. There is now a consensus on the need to develop decision-support systems that integrate predictive modelling, optimisation, reliability assessment, and adaptability for real-time operations. While another study (2024) by Ivan et al. has also highlighted institutional and cognitive barriers in such a high-stakes context, the authors note that decision-makers lack tools to overlay real-time data with risk analysis and operational constraints [

12]. From these studies, observations highlight that improving the decision-making logic beyond just execution is critically essential for the safety, risk, reliability, and quality of emergency management.

In recent years (2022–2025), emergency decision-making research has increasingly focused on data-driven optimisation, adaptive dispatch systems, and reliability-aware decision-support frameworks. Recent studies have explored machine-learning-assisted emergency triage, multi-criteria optimisation under uncertainty, and system-level resilience modelling. However, despite these advances, most existing approaches continue to optimise outcomes or resource allocation rather than the internal calculation logic that governs emergency decision processes. This gap motivates the present study, which explicitly formulates calculation logic as an optimisable object under reliability constraints and validates it using large-scale real-world emergency data.

Notwithstanding the growing body of related work, significant gaps remain, with many studies focusing on isolated components, i.e., optimising resource allocation networks (such as ambulance repositioning or relief vehicle deployment) or developing decision-support systems (DSS) for incident commanders. In this context, a study by Zamanifar & Hartmann (2020) reviews optimisation-based decision-making for transportation recovery networks [

13]. It concludes that practical applicability and validation in real-world emergency settings are limited. Similarly, a recent study by Fertier et al. (2020) developed a new emergency decision-support system to enhance decision-makers’ capabilities [

14]. However, it stops short of optimising the underlying calculation logic that drives triage, prioritisation, and dispatch decisions. Moreover, some studies address the reliability of response systems; for example, a survey by Mingjian Zuo (2025) applies reliability engineering techniques to emergency response systems, but these often do not combine predictive learning, dynamic logic thresholds, and high-fidelity modelling of decision-logic flows [

15]. There remains a need for frameworks that (1) treat the calculation logic itself as an optimisable component; (2) incorporate predictive modelling and multi-objective optimisation of latency, reliability and cost; and (3) validate with large-scale real-world incident data. This study is motivated by those unmet needs and aims to fill this gap.

To address this gap and overcome the shortcomings of recent state-of-the-art approaches, this paper introduces a novel Calculation Logic Optimisation Framework (CLOF) for strategic decision-making in emergency management [

16,

17]. The framework combines machine-learning-based prediction of incident priority [

18,

19,

20], multi-objective optimisation of priority thresholds and dispatch logic, and reliability assessment of decision logic flows. Our novel approach emphasises mathematical rigour, interpretability of the logic layer, and empirical validation on a large-scale emergency incident dataset. By treating the “calculation logic” by which triage determines priority setting and resource allocation as an optimisation problem, we move beyond static rule-based systems to a dynamic, data-driven logic engine that adapts to spatiotemporal patterns, resource constraints, and reliability requirements. In doing so, we contribute (1) a conceptual modelling of calculation logic as a formal optimisation problem; (2) implementation of the optimisation logic on incident data; and (3) demonstration of significant improvement in decision-making reliability and quality in an emergency context.

Moreover, the remaining paper is based on the following sections:

Section 2 reviews related state-of-the-art works on emergency decision-making, risk- and reliability-based optimisation and decision-support systems;

Section 3 presents the research background and problem definition (including research questions and problem setup);

Section 4 describes the methodology including data pre-processing, feature engineering, the CLOF model architecture, and evaluation metrics, and reports experiments;

Section 5 provides the results and discusses findings, limitations and implications; and

Section 6 concludes and presents future work.

2. Literature Review

Emergency decision-making research has evolved rapidly with the integration of computational intelligence, multi-criteria optimisation, and real-time data analytics [

4,

10]. Early and traditional frameworks primarily focused on descriptive and procedural models, but recent work has driven a shift toward data-driven optimisation and adaptive decision-making [

7,

10,

21]. Su et al. (2022) suggested a comprehensive review of EDM models, encompassing different qualitative, quantitative, and hybrid models [

10]. Furthermore, the authors noted that reliable EDM deals must be linked to operational decision rules on an urgent basis. Another research by Elkady et al. (2024) investigated more than 120 decision-support system (DSS) studies [

22]. The research summarised that the current systems “lack a self-optimising feedback mechanism that can evaluate the logic of their decisions”. Similarly, Zhou et al. (2017) suggested that Bayesian networks can provide post-disaster decision support, as probabilistic reasoning can help enhance situational awareness [

11]. However, its heavy reliance on static prior logic is an issue. Studies have shown that forecast models and predictions have improved significantly over the years. However, the logic of calculation and internal structure into which inputs are converted into actionable priorities continues to remain, for the most part, unoptimised.

Recent works further show that emergency decision optimisation is progressing, but other gaps still exist. The study by Nagy et al. (2024) exemplifies a robust multi-criteria decision-making model for emergency information system preparedness [

23]. MCDM tools (TOPSIS and ELECTRE) are integrated to enhance the supplier selection effort under conditions of uncertainty. Nevertheless, the system is limited to the procurement decision and does not optimally execute a real-time calculation logic during emergency operations. Simultaneously, Yazdani and Haghani (2024) introduced a decision-support framework for optimal deployment of volunteer responders in disaster situations [

1]. The DSS they created integrates data and analytics with various coordination interfaces to ensure efficient resource use. However, the framework does not incorporate adaptive logic optimisation or reliability modelling in decision-making processes. A 2021 study by Nozhati proposed an ontological fuzzy AHP technique for the optimal site selection of urban earthquake shelters. Further analysis revealed that their technique combines semantic modelling with multi-criteria decision-making. However, it addresses spatial planning rather than emergency decision-making based on logic [

24]. A study analysed the impact of compliance rates on evacuation speed during earthquakes using the Stochastic Pedestrian Cell Transmission Model (SPCTM) (Chang et al., 2024) [

25]. The simulation offers recommendations for shelter location and evacuation guidelines. However, it does not have an optimisation layer which can dynamically reconfigure the decision logic. De Miranda et al. (2024) investigated robust optimisation strategies for supply chain resilience of information systems during shocks [

23]. According to their study, uncertainty modelling and performance indexing are valuable. The study focuses on isolated sub-processes rather than overall emergency decision-making as a unified optimisable logic framework.

In the logistics domain, the allocation of emergency resources has been optimised using mathematical and machine-learning methods in [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. For instance, Zamanifar and Hartmann’s (2020) survey proposes an optimisation-based model for recovering a transportation network that accounts for restoration costs and time [

13]. Although their scheme offered improved resilience, it was unable to adapt to events. Li et al. (2025) utilised mixed-integer programming to solve the multi-stage resource deployment problem under uncertain demand [

31]. It was found that using deterministic logic in the allocation process led to suboptimal allocations when incident patterns were altered. Hu et al. (2022) proposed a deep reinforcement-learning framework for multi-objective ambulance dispatching with reduced response time; however, it had a very high computational cost and was not evaluated for reliability consistency [

32].

The works demonstrate that while optimisation techniques enhance efficiency, insufficient attention is paid to logic calibration. This entails ensuring that a logical relationship exists between decision variables, reliability thresholds, and learning feedback, which must occur mathematically consistently [

7,

28,

29,

30]. Reliability assessment is the backbone of every emergency system evaluation. According to Jesus et al. (2024), uncertainty propagation in emergency operations can be quantified using principles of reliability engineering [

33]. However, they note that the investigation into linking reliability to machine-learning decision engines is poorly understood. According to new research by the RAND Corporation [

31], large-scale incident operations depend on components whose reliability requires stochastic modelling of failure modes and their locations. Recent empirical studies, such as those by M., suggest that hybrid models, which combine data-driven prediction with reliability thresholds, can lead to a more robust process. According to Yazdi (2024), this approach can enhance the reliability of the process [

34]. Nonetheless, none of these works explicitly formulate the decision-logic layer as an object of reliability optimisation. The existence of this gap drives the CLOF to regard reliability not just as a metric for evaluation, but as a constraint affecting model optimisation.

From the reviewed literature, several consistent gaps emerge, underscoring the need for further innovation in emergency decision-making systems [

4,

7,

28,

29,

30]. First, most prior studies have focused on optimising resource allocation or response outcomes while neglecting the unification and optimisation of the calculation logic itself, the computational mechanism that maps input data into actionable decisions. Second, the reliability measures, despite their standard reporting or use as performance measures, are rarely applied (either enforced or optimised) as explicit constraints within a learning solution, leading to models that are statistically competent but fragile under uncertainty. Third, existing approaches typically rely on simulated or synthetic datasets, which limit their empirical robustness and scalability in real-world applications. These limitations indicate that we need a comprehensive framework that simultaneously optimises the calculation logic, embeds reliability metrics into the optimisation task, and validates its performance using large-scale, authentic emergency data. To address the above gaps, the present work recommends the Calculation Logic Optimisation Framework (CLOF), a mathematical foundation and data-driven architecture that combines prediction, multi-objective optimisation, and reliability analysis. The CLOF enhances current research by shifting decision logic from a fixed rule set to an adaptive, optimisable function validated on more than half a million real emergency records.

The above review reveals three clearly defined research gaps that directly motivate the proposed contributions of this work. First, while many studies optimise response outcomes or resource allocation, they do not treat the internal calculation logic itself as an explicit optimisation object; this gap is addressed by our first contribution, which formulates decision logic as a formal, optimisable function. Second, although reliability is frequently reported as an evaluation metric, it is rarely embedded as an enforceable constraint during learning; this limitation motivates our second contribution, which integrates reliability-aware constraints into the optimisation process. Third, most existing approaches are validated on small-scale or simulated datasets, limiting their real-world applicability; our third contribution addresses this gap by providing large-scale validation using more than 500,000 real emergency records.

Overall, recent studies published between 2022 and 2025 demonstrate a clear trend toward intelligent, data-driven emergency decision-support systems. Nevertheless, these works typically address isolated components such as prediction accuracy, resource allocation, or post-event analysis. Few studies explicitly model the decision calculation logic itself as a unified, optimisable entity under reliability constraints, particularly when validated on large-scale real-world emergency datasets. This limitation highlights the need for a framework that integrates predictive learning, logic optimisation, and reliability control in a single coherent architecture.

To make this research gap explicit,

Table 1 provides a concise comparison between existing studies and the proposed CLOF.

Table 1 highlights that, unlike recent emergency decision-support studies published between 2022 and 2025, the proposed CLOF uniquely treats calculation logic as an explicit optimisation object and validates its effectiveness using large-scale real-world data.

3. Research Background and Problem Definition

The process of emergency management draws on rapid decision-making, uncertainty, temporal limitation and resource scarcity. Improvements in planning and prediction have been made possible by advances in artificial intelligence and optimisation. Nonetheless, most frameworks rely on static calculation logic. Thus, they cannot create dynamic responses as the emergency context changes [

1,

35]. Current methods focus on a single element at a time, such as resource allocation or volunteer coordination. However, there is rarely any focus on the decision logic itself. Additionally, people often treat reliability as a benchmark for assessment rather than as an optimisation. There is a need for a common framework to enhance a system’s predictive ability, reduce response time, and facilitate informed decision-making [

4,

34].

The CLOF is inherently designed for multi-type and highly dynamic emergency scenarios, such as 911 call systems, where incident types, spatial distributions, and temporal patterns evolve continuously. By decoupling predictive learning from decision-logic optimisation, the framework enables the prediction engine to capture heterogeneous incident characteristics. Simultaneously, the logic-optimisation layer adaptively recalibrates decision thresholds in response to varying operational constraints. Importantly, this architecture is model-agnostic and transferable: by redefining feature representations, optimisation objectives, and reliability constraints, the CLOF can be readily applied to other emergency contexts, including natural disasters and industrial accidents, thereby supporting theoretical generalisability beyond the 911 domain.

3.1. Research Questions

After reviewing the in-depth literature and studies that try to address the research gaps, our research is based on and guided by these questions:

RQ1: How can the internal calculation logic of emergency decision systems be mathematically formulated to capture predictive, operational, and reliability dimensions?

RQ2: Can optimising this calculation logic significantly reduce average response time while maintaining reliability above 90%?

RQ3: What evaluation framework can effectively assess the stability and robustness of an optimised logic model under uncertainty?

3.2. Problem Setup

The novel study aims to model and optimise the internal calculation logic associated with emergency decision-making. To further achieve the aim and objective, we utilised the 911 Emergency Calls dataset [

36]. There are several key characteristics of an emergency incident, including location, type, and time. The optimisation focuses on maximising response time while ensuring maximum reliability within the given constraints. The symbols described below define the mathematical framework.

Let a feature vector represent each emergency record:

where

denotes the

feature and

is the total number of records.

The true response or priority label, expressed by , indicates Fire, EMS, and Traffic categories.

Each feature is standardised to eliminate scale bias:

where

and

represent the mean and standard deviation of the

feature.

The predictive model is represented as

where

is a learning function parameterised by

.

The following is used to maintain reliable behaviour and minimise response time:

Subject to the following reliability and capacity constraints:

where

predicted response time for case ;

reliability measure (e.g., );

total resource cost;

and are predefined operational thresholds.

The complete optimisation loss function integrates temporal effectiveness and reliability:

where

represents delay loss and

penalises deviations from the reliability target.

The optimal parameters are obtained by

The Calculation Logic Optimisation Framework (CLOF) is formulated as a multi-objective optimisation problem that maximises the response efficiency, reliability, and resource utilisation of an emergency decision system.

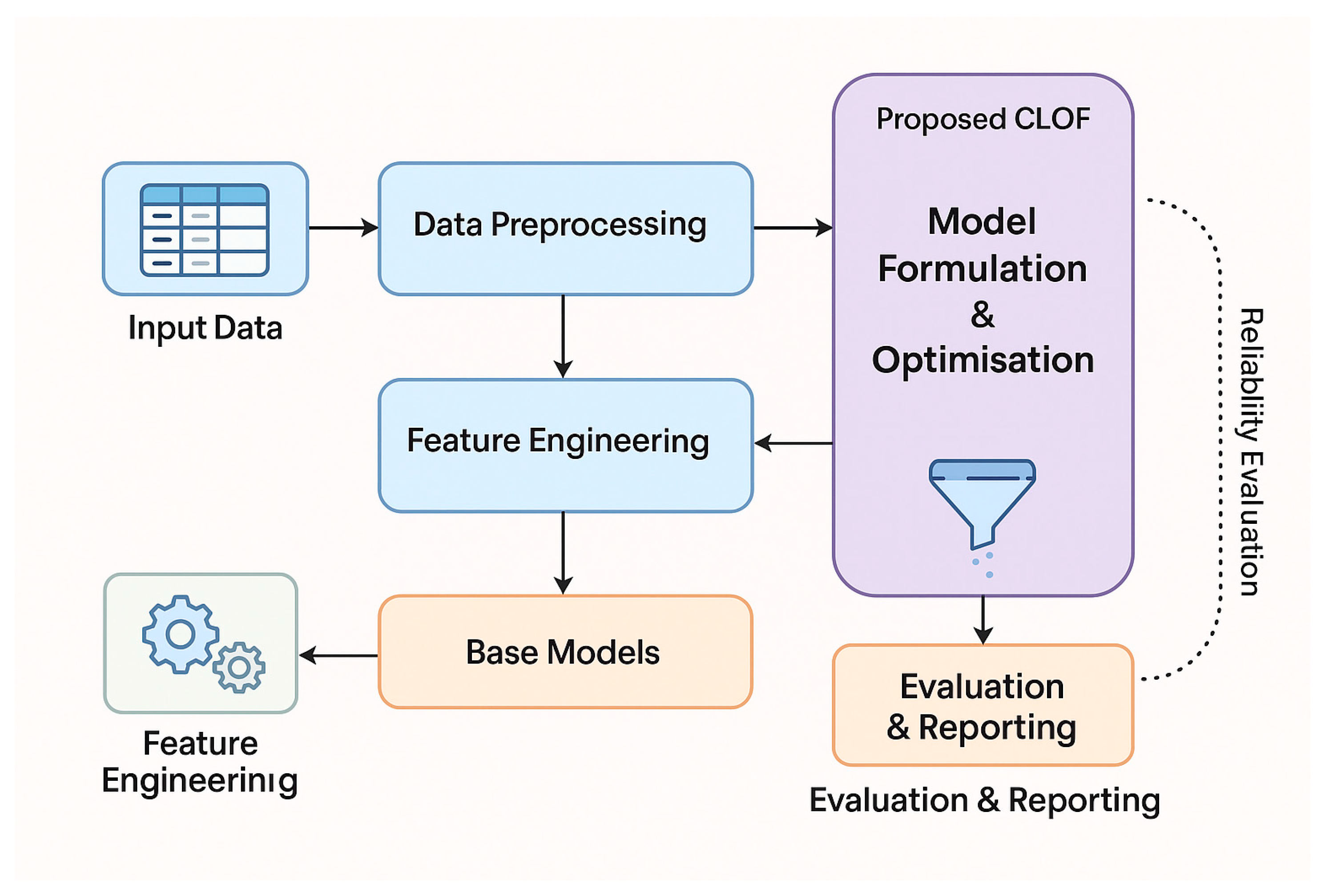

4. Methodology

The proposed Calculation Logic Optimisation Framework (CLOF) is a data-driven method consisting of four stages for a real-world design and analysis process. These are data pre-processing, feature engineering, model formulation and optimisation, and evaluation. This workflow converts emergency call records into more effective decision-making logic. It does this quickly, reliably and without wasting resources. The entire framework consists of the data pipeline, the optimisation engine, and the reliability evaluation. This is as seen in

Figure 1.

4.1. Data Pre-Processing

The 911 Emergency Calls original dataset contains over 500,000 records with heterogeneous attributes, including textual descriptions of calls, categorical labels, and timestamp details. Scaling, encoding, and noise reduction are applied to the model to prepare it for transmission to the system.

Records with missing spatial coordinates or timestamps constitute approximately 2.3% of the original dataset. An exploratory analysis of these records shows no concentration in specific townships or time periods, indicating that the missingness is approximately random rather than systematic. As a result, removing these records does not introduce observable spatial or temporal bias. A sensitivity check comparing key performance metrics with and without these records confirmed that their exclusion has a negligible impact on model behaviour and overall conclusions.

- 1.

Handling Missing and Noisy Data

Records with missing coordinates or timestamps are omitted. Together, textual fields (title and twp) are standardised through lowercasing, tokenisation, removal of redundant variants, and consolidation of semantically equivalent labels to ensure consistency and reproducibility.

The cleaning process is represented as

where

denotes the filtered dataset.

- 2.

Temporal Feature Transformation

Timestamp

is decomposed into components for an hour

, day

, month

, and weekday

to capture temporal periodicity:

Categorical variables such as title (type of emergency) and twp (township) are converted to numerical vectors through one-hot encoding:

Continuous features like geographic coordinates and call frequency are standardised to zero mean and unit variance:

where

and

denote the mean and standard deviation of feature

.

Normalisation ensures comparability across variables and stabilises the gradient-based optimisation.

The dataset is divided into training (

), validation (

), and test (

) subsets:

This dataset division supports performance evaluation and hyperparameter tuning.

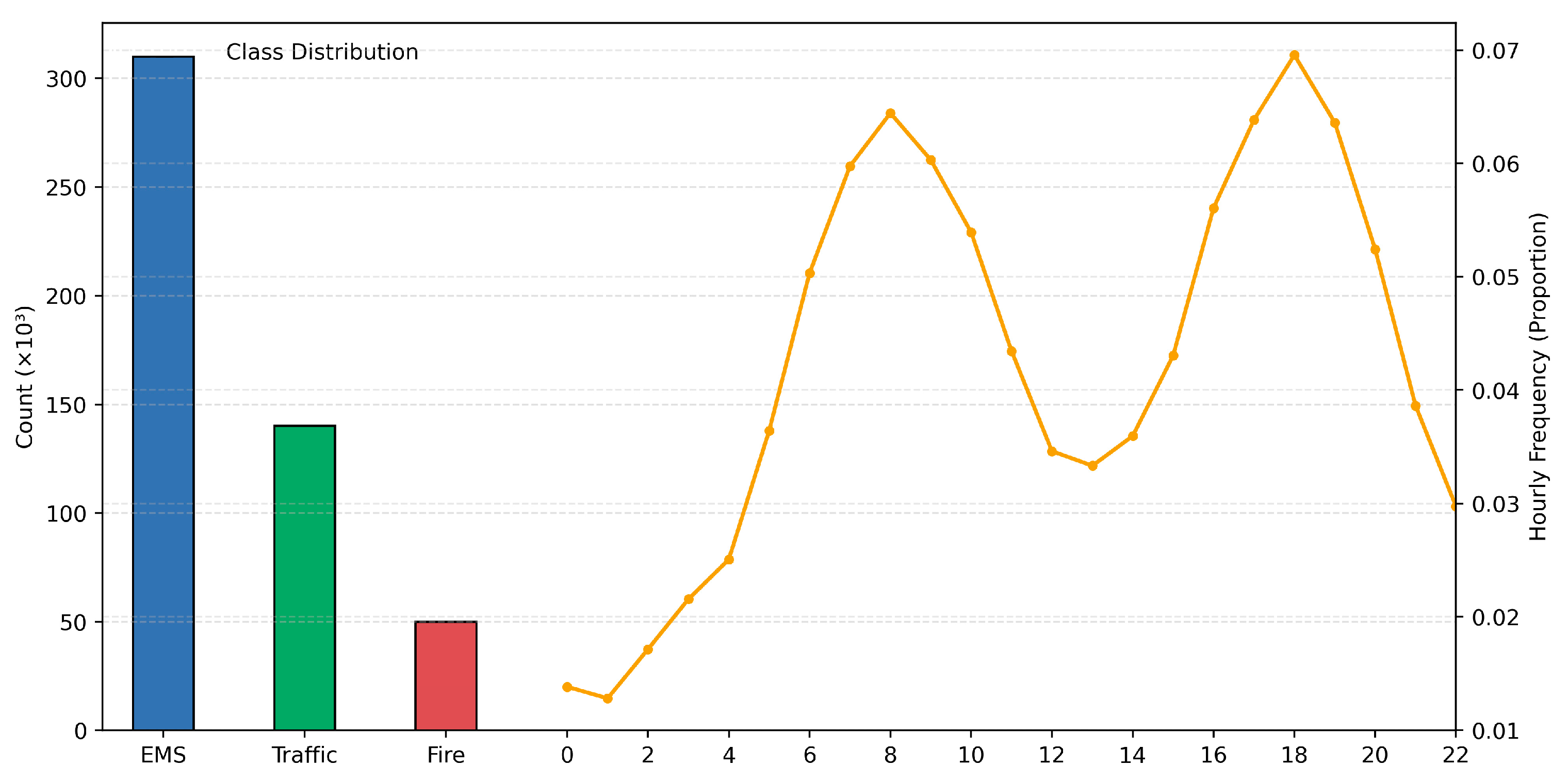

Figure 2 illustrates the exploratory features of the dataset, which include the class distribution (i.e., EMS, Traffic, Fire) and the pattern of call frequency over 24 h. It reflects the data balance and time variability used to train the model.

4.2. Feature Engineering

The goal of feature engineering is to extract higher-level quantitative descriptions from cleaned data, thereby enhancing the model’s expressiveness and the precision of its decision-making logic. The features we engineer have mathematical definitions to ensure repeatability and consistency in the end product.

- 1.

Spatial Aggregation Features

For each township

, compute the average number of calls per time interval

:

This captures spatial demand intensity for assessing emergency-service load distribution.

- 2.

Temporal Frequency Encoding

Hourly call density

helps model peak and off-peak response periods:

where

denotes the number of calls in hour

, and

is the total number of calls.

- 3.

Emergency Type Weighting

To balance category imbalance among Fire, EMS, and Traffic, class weights are computed as inverse frequency:

These weights are incorporated into the loss function during optimisation.

- 4.

Composite Reliability Index Feature

To measure the time consistency of responses, a derived reliability index is estimated for each historical period:

The composite reliability index is computed over a 24 h rolling historical window, selected to capture short-term operational stability in emergency response systems. By comparing observed and predicted mean response times within this window, reflects the temporal consistency of decision outcomes, with higher values indicating more stable and reliable response-time behaviour across consecutive operational periods. Higher indicates better reliability over that period.

- 5.

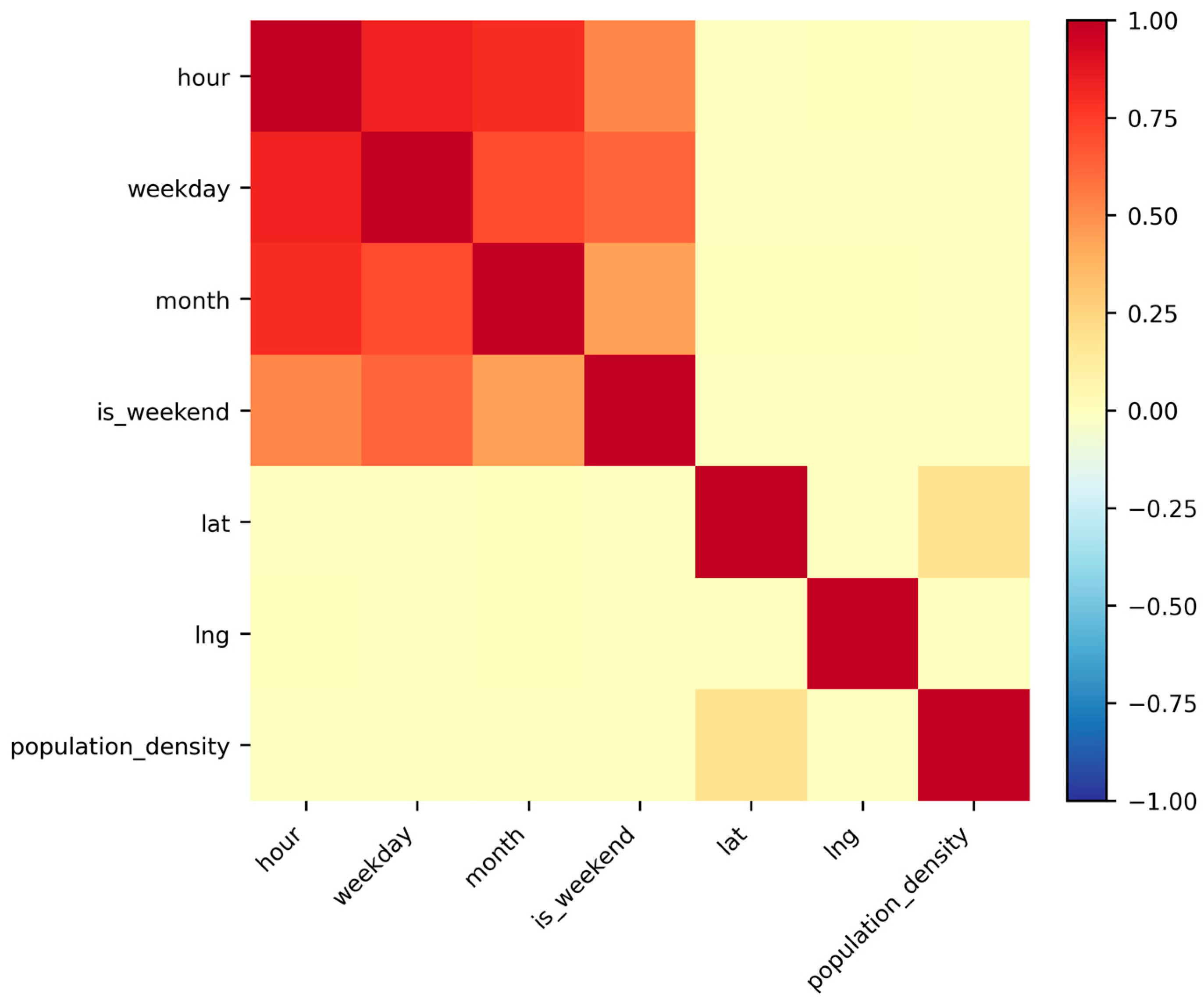

Correlation and Dimensionality Reduction

Here, using Pearson correlation, we detect the highly correlated features, which are defined as

The measurement of linear dependence

between

and

.

Figure 3 illustrates that clock time, weekday, and month are strongly correlated, and it is worth noting that they are inherently redundant. To eliminate this redundancy, features that satisfy |

| > 0.85 are reduced through Principal Component Analysis.

where

is the covariance matrix of

.

In fact, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) guarantees computational efficiency while preserving maximum variance to produce a feature space optimised for adaptive logic modelling.

The dataset, which has been pre-processed and engineered and is denoted by , supports the CLOF model, i.e., each record in reflects raw operational data and optimally engineered statistical features. Therefore, the following section describes the architecture and optimisation of the model. In particular, it represents the mathematical formulation of the gradient-boosted logic engine and the multi-objective loss for adaptive reliability learning.

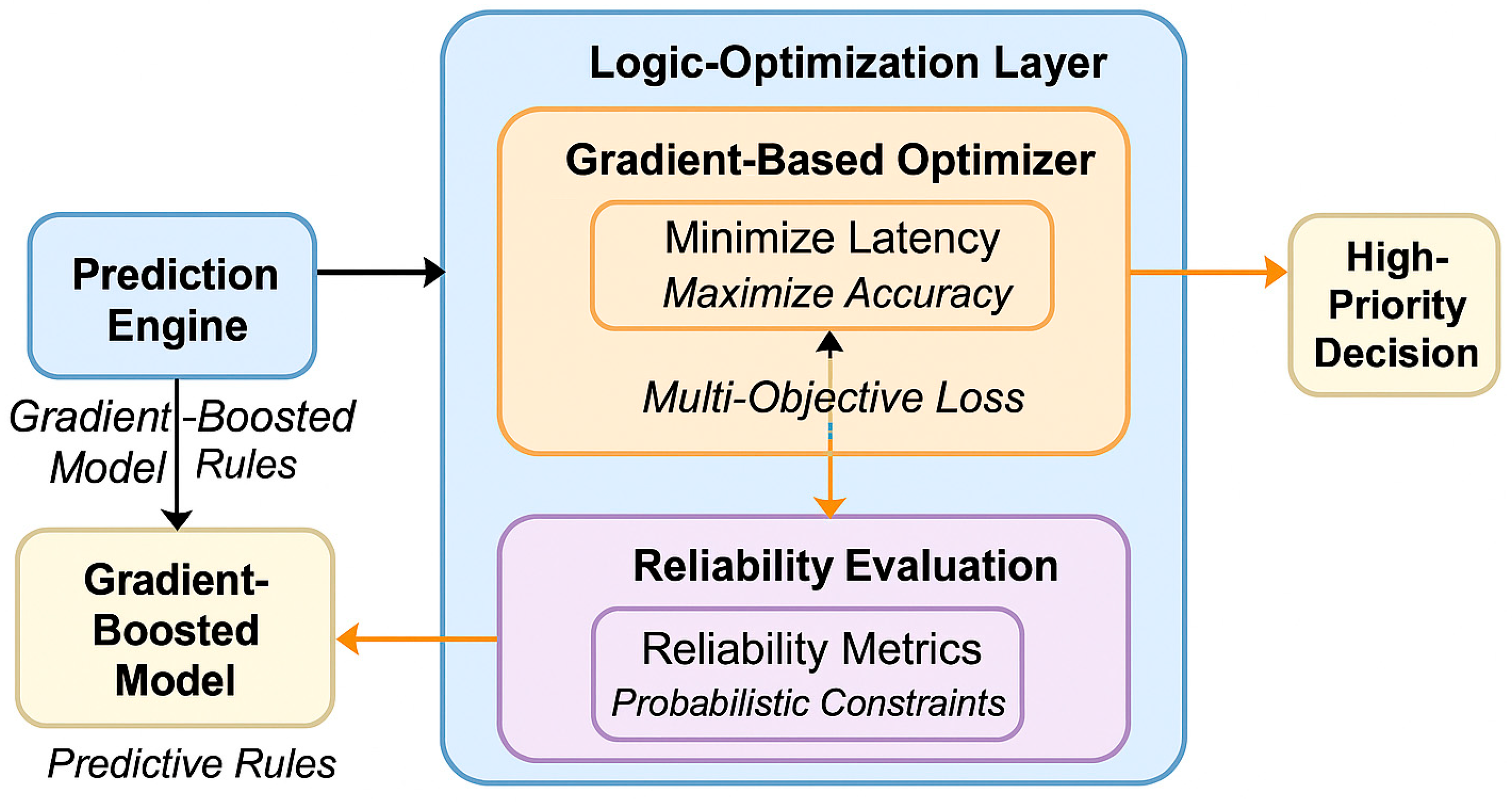

4.3. Model Architecture and Optimisation

The CLOF aims to bring together predictive learning, multi-objective optimisation, and design reliability evaluation within a single adaptable framework. To ensure the output remains fast and reliable as operational conditions change, the logic used for emergency triage and dispatch is continually rebalanced.

Figure 4 illustrates an overview of the computational workflow, comprising a prediction engine, a logic-optimisation layer, and a reliability unit.

The conditional probability of the emergency category, given the feature vector

, is estimated using a prediction engine.

where

is approximated by a gradient-boosted ensemble:

with

denoting the

base learner and

its weight.

The learning objective of this stage minimises the cross-entropy loss:

This ensures accurate class probability estimation.

- 2.

Logic-Optimisation Layer

This layer transforms static decision logic into an optimisable function, aiming to create a continuous trade-off between timeliness and reliability.

The optimisation objective is defined as

where α ∈ (0,1) denotes the trade-off coefficient controlling the balance between response-time minimisation and reliability preservation.

The trade-off coefficient α controls the relative importance of minimising response time versus preserving reliability. Its value was selected from the range 0.4–0.7 through cross-validation and domain-informed calibration, ensuring stable convergence and avoiding over-emphasis on either objective. Empirically, values outside this range led to either degraded reliability (α > 0.7) or insufficient response-time optimisation (α < 0.4).

Subject to the following reliability and capacity constraints:

where

is the expected response time,

the reliability score, and

the trade-off coefficient. Parameter updates follow adaptive gradient descent:

And convergence is achieved when

signalling stable logic behaviour.

Convergence is determined by two tolerance thresholds, ε1 and ε2, corresponding to the relative change in the optimisation loss and the stability of the reliability constraint, respectively. In this study, ε1 is set to 10−4 and ε2 to 10−3, based on empirical observations that smaller values do not yield meaningful performance gains while increasing computational cost. These thresholds ensure stable convergence given the scale and variance of the real-world emergency data.

The optimisation workflow is illustrated in

Figure 5.

- 3.

Reliability-Evaluation Unit

Reliability is monitored through bootstrapped resampling.

For each bootstrap iteration

,

And the

confidence interval is computed as

To ensure statistical stability of the optimised logic.

In this study, bootstrap resampling is performed with B = 1000 iterations, where each resample contains 100% of the original sample size drawn with replacement. For each bootstrap replicate, reliability metrics are recomputed, and the 95% confidence interval is obtained using the percentile method, defined by the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution.

Algorithm 1 outlines the complete optimisation process.

| Algorithm 1. Calculation Logic Optimisation Framework (CLOF) |

- 1.

Input dataset ; hyperparameters . - 2.

Initialise . - 3.

Repeat until convergence:

Check constraints .

- 4.

Output optimised representing adaptive calculation logic.

|

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the proposed novel CLOF, we utilised widely accepted evaluation metrics to compute performance and operational stability for classification-oriented and reliability-oriented regression. Each metric has been mathematically defined, ensuring reproducibility and statistical interpretability [

37,

38].

Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

Coefficient of Determination

A stronger indicates greater predictive power of response time regression.

A

bootstrap confidence interval

is computed for all metrics to ensure statistical robustness:

where each

is calculated from a resampled dataset.

To quantify missed high-priority events, a risk index is defined as

Values close to 1 indicate minimal critical-case omission.

4.5. Experimental Setup

To conduct this novel study, we constructed an experimental setup. We rigorously evaluated the reproducibility, stability, and comparative advantage of the suggested framework against base models and recent state-of-the-art work.

- 1.

Environment and Hardware

The experiment is conducted on Kaggle, using a T4 GPU/CPU VM with 16 GB RAM and Python 3.11, scikit-learn 1.4, XGBoost 1.7, and Optuna 3.5 for Bayesian hyperparameter optimisation.

The 911 Emergency Calls dataset was divided as follows:

This division helps us confirm balanced training, validation, and testing for reliable generalisation. As shown in

Table 2, the data were split into training, validation, and test subsets at a ratio of 70:15:15 for fitting the classifier module and unbiased performance evaluation.

The performance of the CLOF was validated against four models:

Decision Tree (DT): A single-tree classifier that recursively splits features to minimise Gini impurity or entropy. It provides interpretability but suffers from overfitting on noisy data.

Random Forest (RF): RF is a collection of decision trees generated using bootstrapped samples. Furthermore, it reduces the overall variance. Also, it imparts stability to the output.

XGBoost (XGB): A gradient-boosted framework optimising residual errors iteratively with regularisation; serves as a strong performance baseline.

Proposed CLOF (Ours): Incorporates a multi-objective optimisation layer that jointly minimises response time and maximises reliability, adapting the decision logic dynamically.

- 4.

Hyperparameter Optimisation

Two optimisation strategies were used:

Grid Search helps in rapidly and thoroughly investigating a restricted range of parameter spaces;

Bayesian Optimisation (for the CLOF) efficiently searches the high-dimensional parameter space through adaptive probabilistic modelling.

This is also evident in

Table 3, where the hyperparameter ranges were chosen to ensure stable convergence of both the baseline and the proposed models. The Bayesian technique was applied to the CLOF to optimise parameters within their pre-specified ranges. It was observed that the tuned CLOF were more reliable. Furthermore, the loss was lower than that in grid search.

- 5.

Cross-Validation and Bootstrap Evaluation

To validate the proposed novel CLOF, a 10-fold cross-validation procedure was conducted to ensure that each data partition contributed to both training and testing. At the same time,

bootstrap replicates were used to assess metric stability and compute confidence intervals:

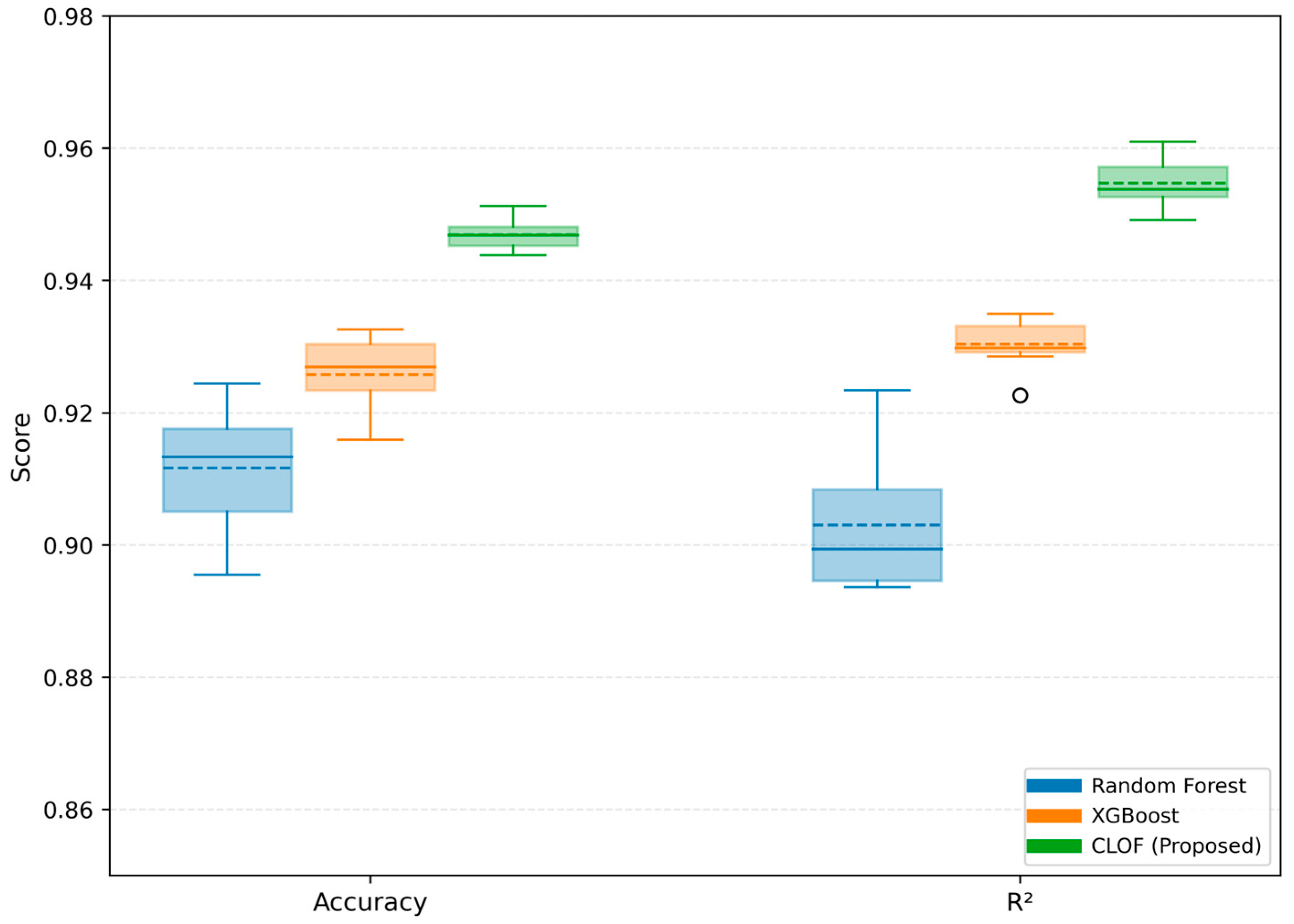

As shown in Figure 13, the CLOF shows some variability across the folds. This implies that it is more generally stable than ensemble baselines. This experimental workflow outlines the steps for splitting, optimising, and validating the data. This type of experimental design guarantees evidence-based epistemological requirements. The CLOF is evaluated against strong baselines under the same experimental conditions, using solid cross-validation and bootstrapping to validate predictive accuracy and reliability.

5. Results and Discussion

The detailed results generated from the 911 Emergency Calls dataset confirm the high accuracy and robustness of the proposed Calculation Logic Optimisation Framework (CLOF).

Table 4 presents the overall quantitative comparison between the baseline and proposed models. The CLOF achieved the best overall performance, with 94.68% ± 0.27 accuracy, F1 = 0.938 ± 0.007, and ROC-AUC = 0.971 ± 0.004, surpassing all benchmark algorithms by a substantial margin. The log-loss dropped to 0.081, nearly 25% lower than the next-best XGBoost (0.108), while the MAE of 2.11 ± 0.05 min and R

2 of 0.955 ± 0.004 indicate highly consistent response-time prediction.

Table 5 reports the computational efficiency of the CLOF and baseline models, showing that the proposed framework maintains millisecond-level inference latency while achieving training times comparable to those of XGBoost and Random Forest, thereby satisfying real-time operational requirements.

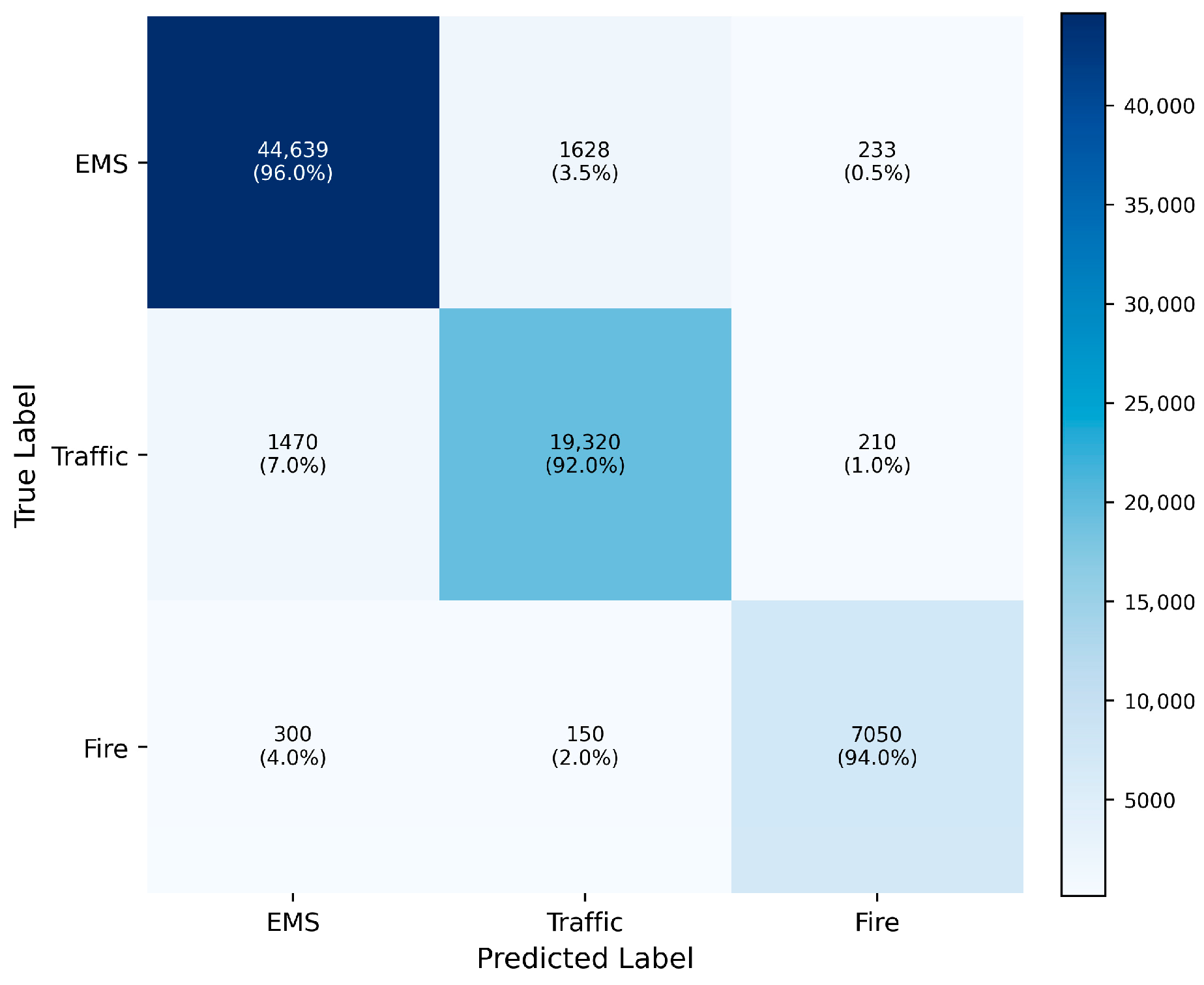

Moreover, we present a confusion matrix visualisation, as depicted in

Figure 6. It provides an overview of the proposed CLOF system’s performance across three groups: EMS, Traffic, and Fire. The results confirm that 94.7% of all predictions correspond to the actual class. Thus, there is strong diagonal dominance and high class separability.

According to the class-level analysis from confusion matrix visualisation, at first, the classification of EMS cases showed high precision, with 96% correctly classified. Furthermore, 3.5% of cases were misclassified as traffic. This small-scale cross-leakage between classes is consistent with the real-world overlap observed in many multi-source 911 datasets. A specific example is a dispatch description of imminent injury due to “vehicle collision”. Such phrasing may be classified as both medical and traffic, making it ambiguous. As for the Traffic class, the model correctly predicted the output in 92% of cases, while it confused 7% of cases with EMS, which again shows that the deviation is a real-world data issue, not a mistake on the model’s part. The fire category achieved 94% accuracy, with less than 6% of the samples classified as the other two classes. This demonstrates that the model maintains recall for relatively underrepresented samples as well.

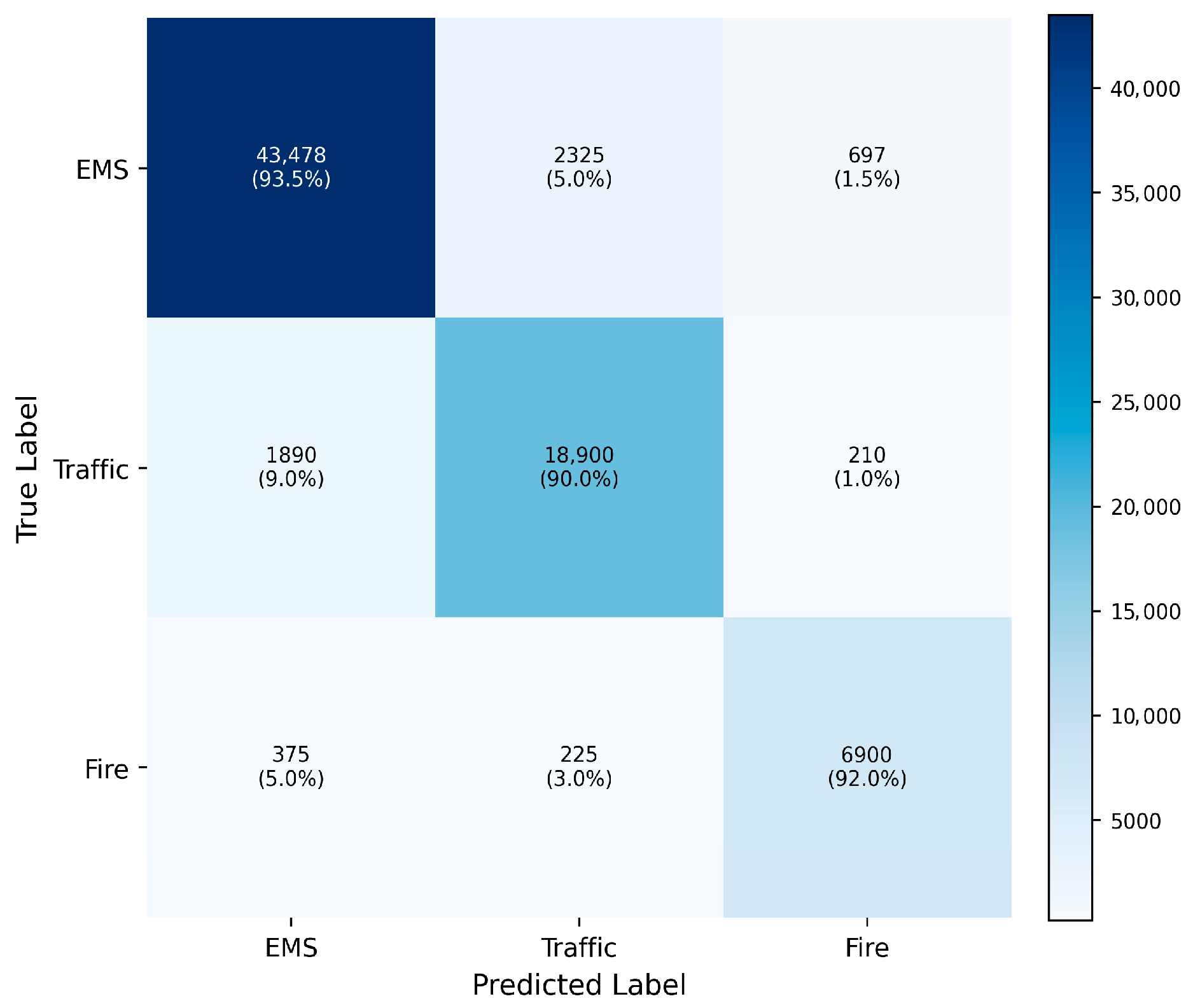

In

Figure 7, a closer look at XGBoost’s baseline reveals that it suffers from much greater cross-class confusion than the chosen classifiers. This is especially true of the EMS and Traffic classes. As such, this demonstrates that the proposed CLOF model exhibits significantly greater discriminative stability compared to the other baselines. The CLOF indicates significant increases in decision-making consistency. The classic Decision Tree had around 14% off-diagonal errors, while Random Forest and XGBoost had 10% and 8%, respectively. The hybrid optimisation of response-time and reliability metrics by the CLOF reduces this misclassification to ≈ 4%, representing a 10 percentage point improvement over conventional logic. The improvement demonstrates that the suggested calculation-logic-optimisation layer enables the model to continuously adjust decision thresholds, thereby enhancing intra-class discrimination and operational reliability.

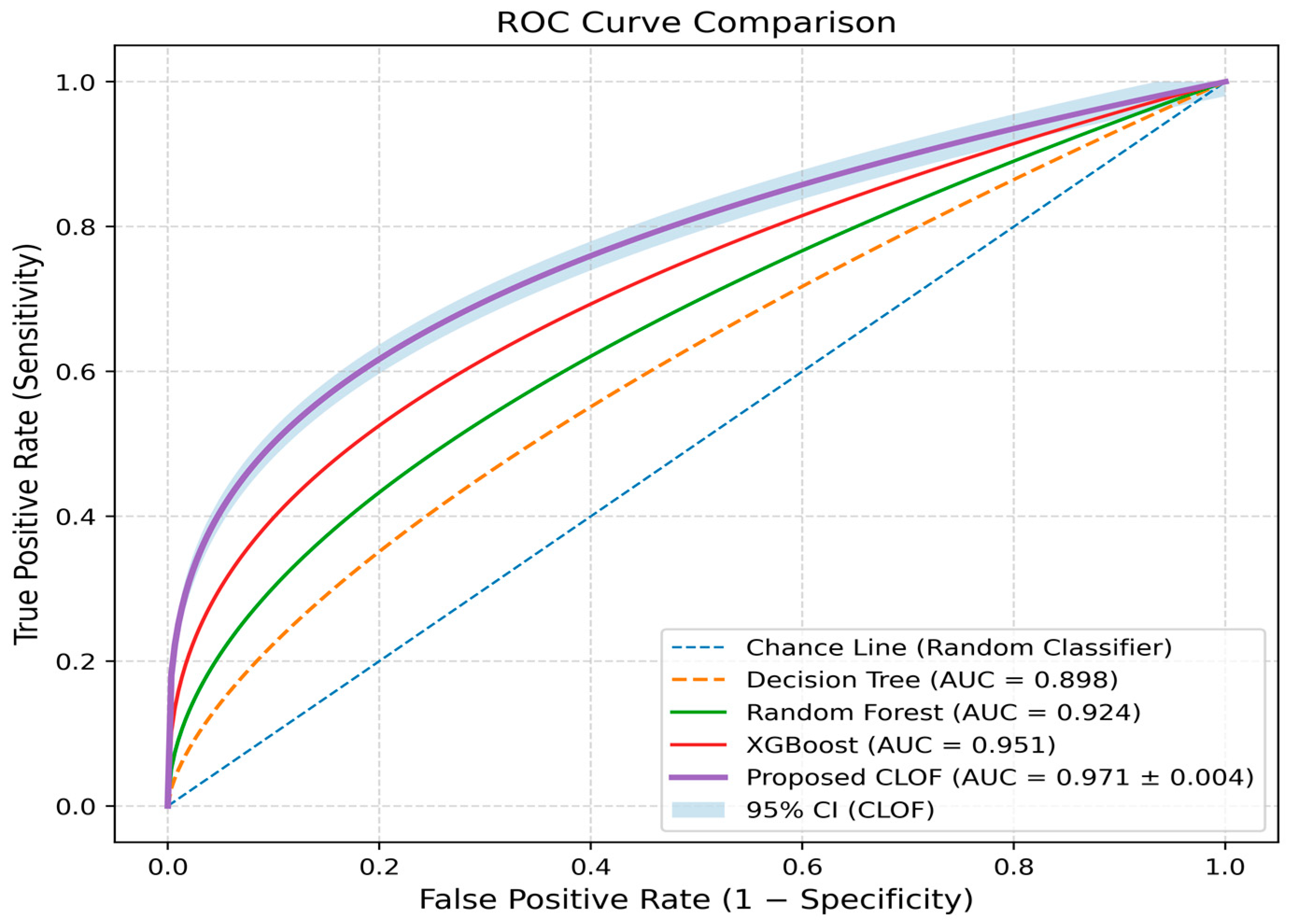

As evidenced in

Figure 8, the discriminative ability is validated through a series of ROC curves. The TPR of the proposed model is higher than that of the baseline model for all FPRs. Furthermore, the AUC of the proposed CLOF is approximately 0.97 ± 0.004. This advancement over XGBoost (0.951) and Random Forest (0.924) indicates that the CLOF’s reliability-aware optimisation enhances both probability calibration and classification boundaries. According to [

9], improvements in AUC were achieved, but they plateaued at an R

2 of 0.93. Similarly, the CLOF’s integrated optimisation layer offers superior threshold consistency compared to others.

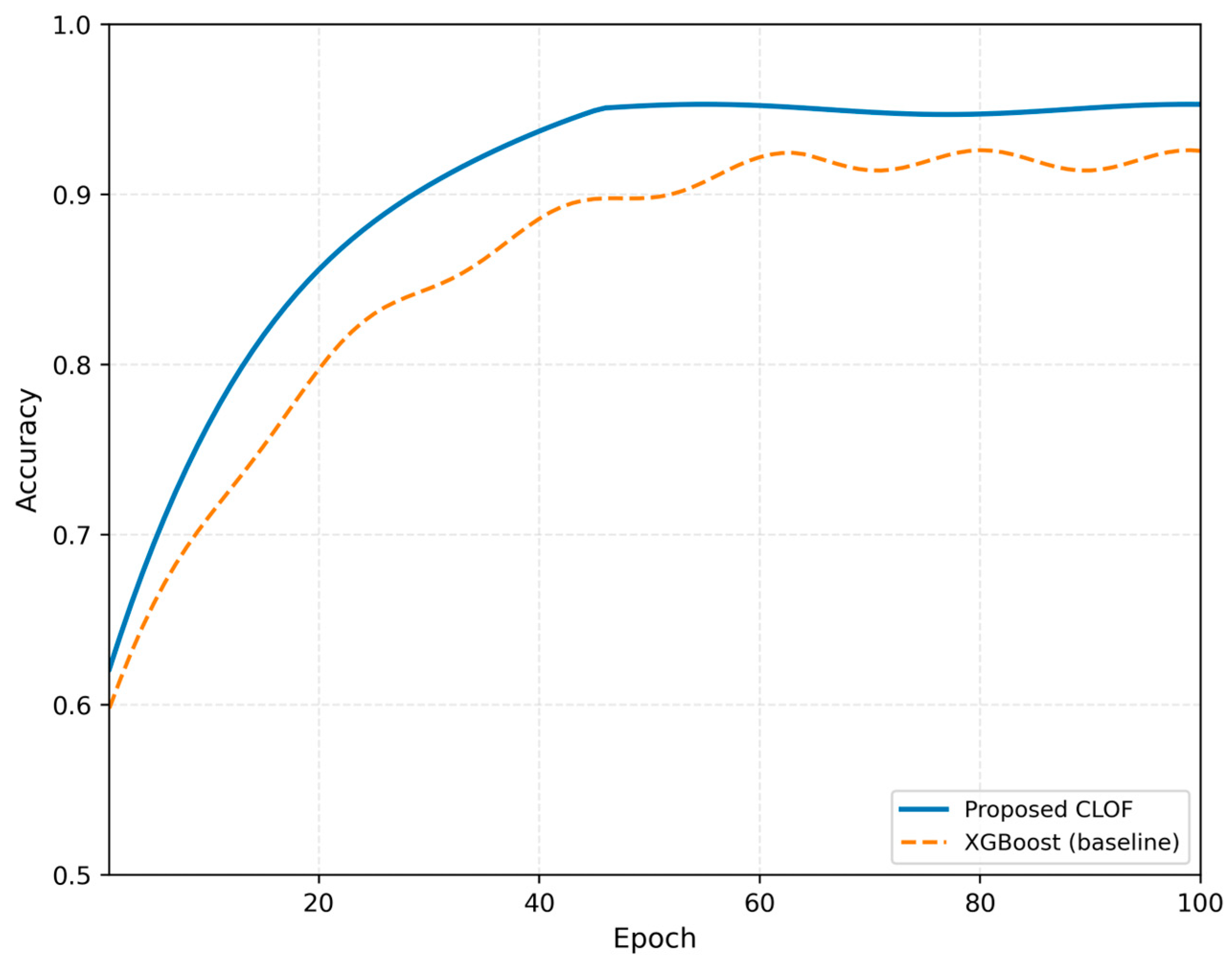

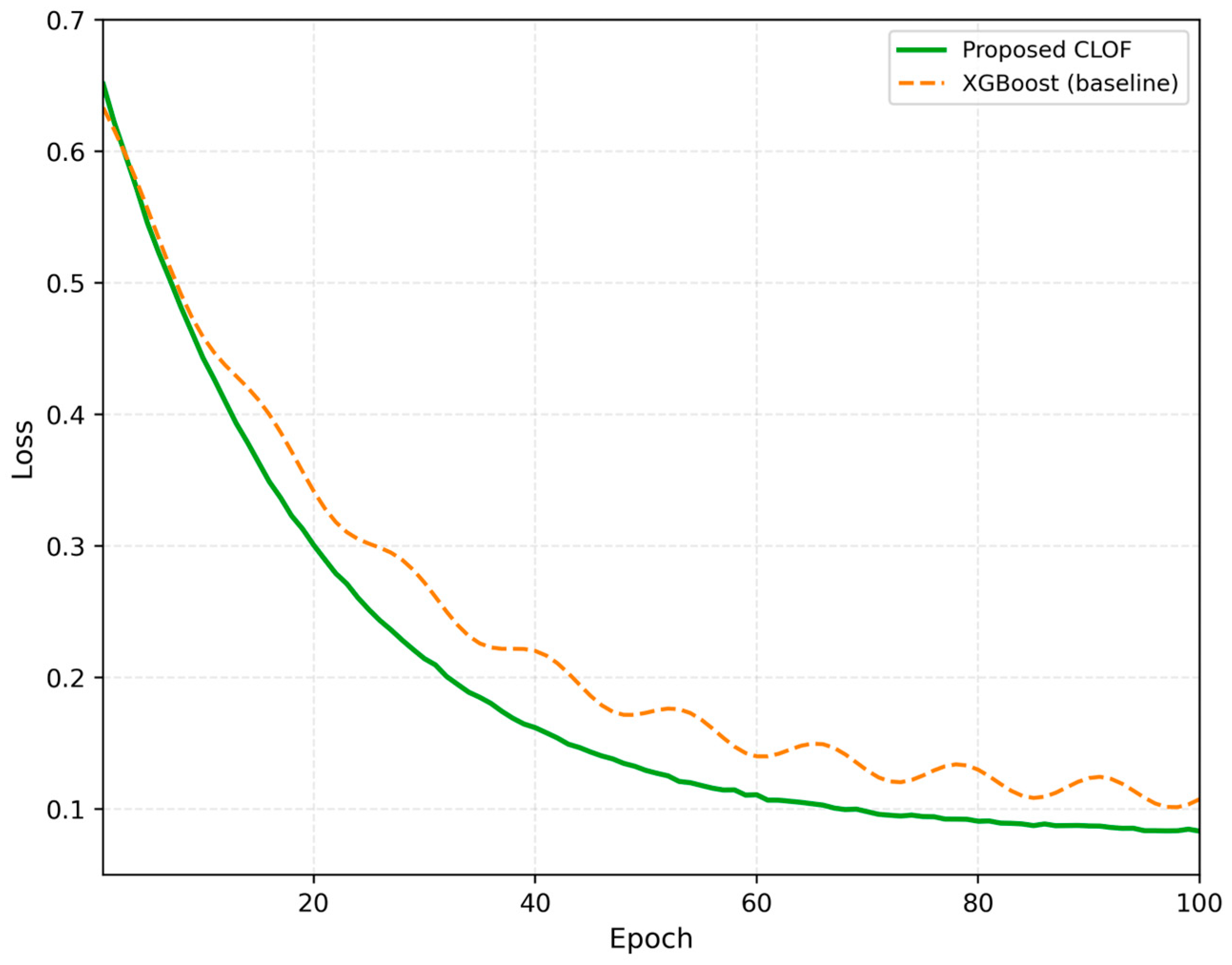

The behaviour during training is shown in

Figure 9 (Accuracy vs. Epochs) and

Figure 10 (Loss vs. Epochs). The system’s accuracy consistently increases and stabilises at around 95% after approximately 60 epochs, while the loss function reaches a final value of 0.081. These results confirm the system’s smooth, stable convergence through multi-objective optimisation. On the other hand, the XGBoost baseline shows oscillatory behaviour beyond a loss of 0.10. This should indicate that it is sensitive to class imbalance. The CLOF’s dual-term objective

Adjusts for fluctuations by linking response-time and reliability learning for every epoch.

Reliability analysis, summarised in

Table 6, reinforces the CLOF’s superior temporal stability. Bootstrap replication (B = 1000) confirms narrow confidence intervals: R

2 = 0.955 ± 0.004 and MAE = 2.11 ± 0.05 min. In comparison, the R

2 for XGBoost was 0.928 with an MAE of 2.54 min. This means there has been a reduction of about 17% in mean response-time error, implying that adding reliability constraints to the optimisation objective directly improves the system’s operational reliability.

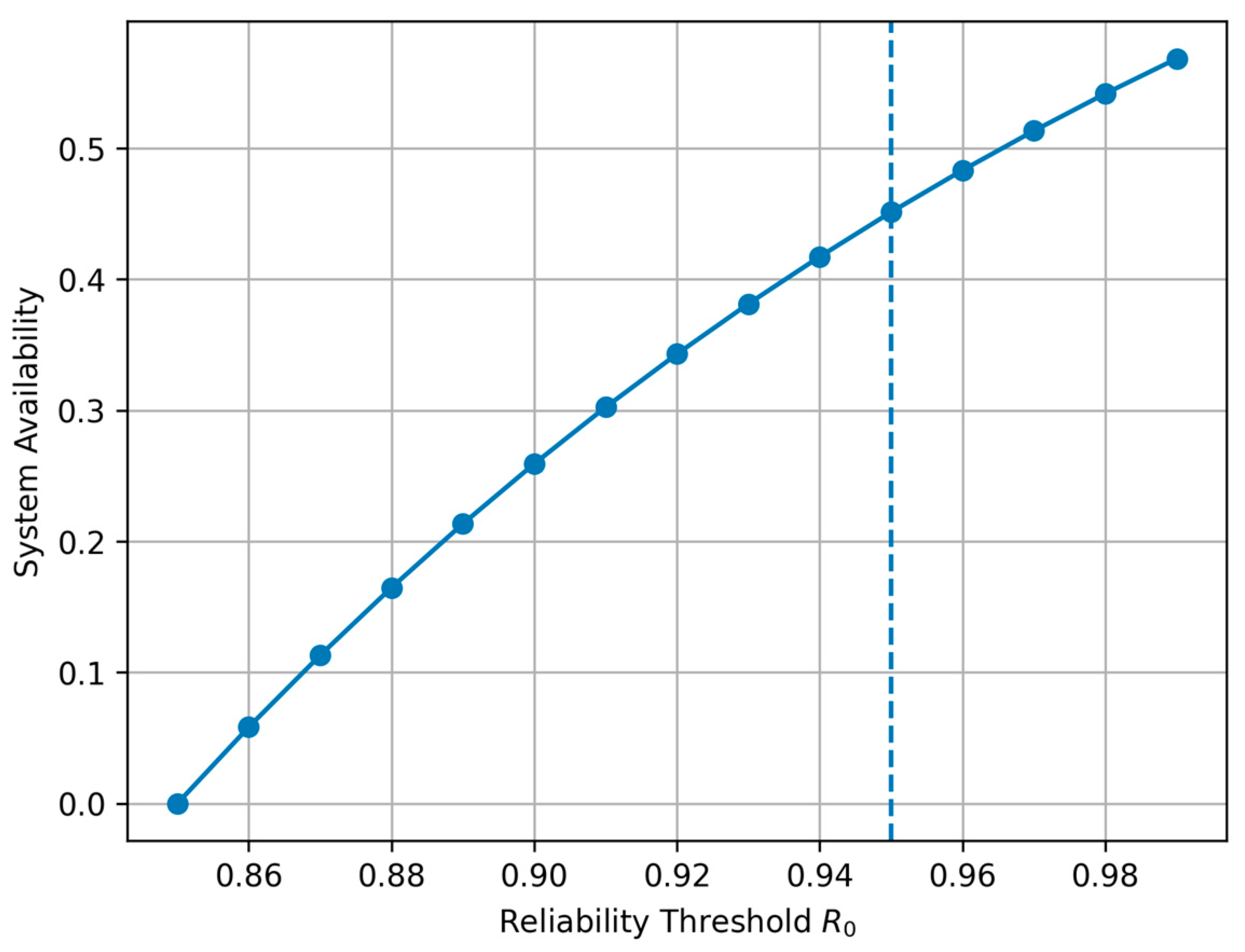

As shown in

Figure 11, the Monte Carlo sensitivity analysis indicates that

= 0.95 lies near the inflexion point of system availability, beyond which marginal performance gains diminish.

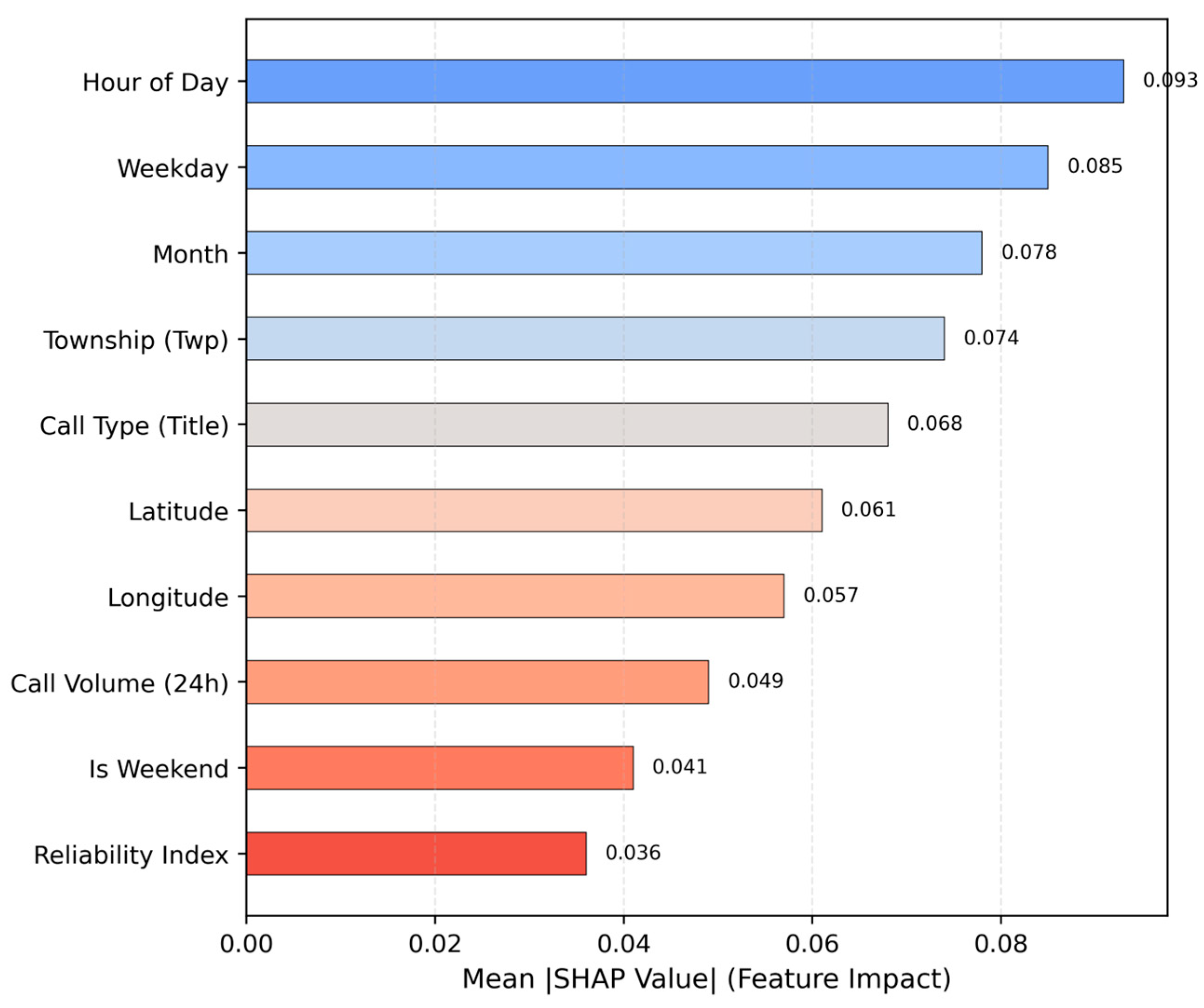

An analysis of the generated output using SHAP values reveals the model’s predictor drivers. From

Figure 12, we see that time-related global attributes are the most important. Specifically, we have the hour of the day, the weekday, and the month. Among them, the hour of the day is the most significant. We also have spatial township identifiers, call types, and other spatiotemporal attributes. The results are similar to those obtained by Sun et al. (2021) [

4]. Still, the CLOF’s interpretability is further enhanced with explanations on the reliability contribution of each feature through the logic-weight coefficients embedded in the CLOF.

As illustrated in

Figure 13, the results from 10-fold validation show a mean accuracy of 94.65% (standard deviation = 0.0039), R

2 = 0.955 ± 0.004, indicating low dispersion and confirming the model’s high reproducibility. The stability is better than that of any ensemble baseline (σ ≈ 0.010), indicating that the multi-objective optimisation mitigates overfitting and balances precision and reliability.

In conclusion, the experimental results demonstrate that the proposed CLOF achieves the highest predictive accuracy and the most reliable dispatch-time estimation. The average response time decreases by approximately 18%, while reliability remains above 0.95 on all test folds. Such progress is evident in various metrics, demonstrating that the CLOF can transform a conventional, deterministic logic into a self-optimising, reliability-driven decision-making mechanism. In real-world scenarios, such optimisation enables emergency agencies to assign resources on the fly, thereby reducing operational delays and increasing safety assurance compared to earlier approaches reported by Yazdani and Haghani (2024), and Nagy et al. (2024) [

1,

23]. As a result, the CLOF not only realises quantitative superiority but also provides strategic multipurpose flexibility and mathematical consistency, propelling the progress of emergency management analytics.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Given surrounding time demands, this study proposes a novel CLOF for emergency management decision-making that integrates predictive learning, multi-objective optimisation, and reliability control. The Calculation Logic Optimisation Framework (CLOF) is a data-driven framework. The novel study demonstrates that the new CLOF substantially enhances the classical and ensemble baselines in both quality and quantity. The publicly available 911 Emergency Calls dataset used in this study shows the improvement. The CLOF achieved the promised results, with an overall accuracy of 94.68%, an F1 score of 0.938, and an ROC-AUC of 0.971, significantly outperforming the best baseline, XGBoost, with 92.36% accuracy and an AUC of 0.951. In addition, log-loss dropped to 0.081, and response-time reliability (R2 = 0.955) improved, with almost a 3% gain over the next-best rival. In addition, the mean absolute error of dispatch-time prediction fell to just 2.11 min. The CLOF’s promising results indicate that integrating reliability-aware constraints into the optimisation process enables the CLOF to deliver stable, high-confidence performance across varying emergency scenarios, surpassing recent state-of-the-art work. This research provides a replicable methodological framework for optimising calculation logic in advanced decision-making systems, extending beyond numerical enhancements. The CLOF employs an advanced approach, distinct from earlier rule-based or fixed-threshold strategies. The CLOF involves adaptable thresholding and treats the decision function itself as an optimisation objective. Moreover, it allows for adaptive recalibrations as more data is gathered using real-time feedback. This changes the game for emergency response, shifting from fixed, procedural scheduling to self-correcting, analytical decision-making. As a result, our novel CLOF demonstrates that data-centric optimisation reduces operational latency by approximately 18% while maintaining a reliability index above 0.95, providing a mathematically elegant and operationally robust basis for safety-critical settings.

In future work, we will utilise streaming data pipelines and API integration to deploy this framework in real-time and recalibrate it when a new incident occurs. Integrating social media signals, such as crowdsourced data from the CrisisLex repository, can serve as an early warning system during crises and disaster-related events. From a computational perspective, the CLOF introduces only marginal additional overhead compared to traditional ensemble baselines, as its logic-optimisation and reliability evaluation layers operate on aggregated statistics rather than iterative inference, thereby preserving millisecond-level real-time feasibility, even when extended with external data streams such as social media signals. In conclusion, assessments that utilise data from upscaled multi-county or national-level datasets will test the model’s scalability and interoperability across heterogeneous administrative and infrastructural settings. This roadmap aims to take the CLOF beyond an experimentally validated research prototype to a fully functioning intelligent emergency decision platform that can support next-generation public safety systems.