From Framework to Reliable Practice: End-User Perspectives on Social Robots in Public Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How do end users perceive safety, privacy, and ethical transparency when interacting with a public-facing social robot?

- RQ2: How do users evaluate accessibility and inclusivity in a real-world robot deployment?

- RQ3: To what extent do SecuRoPS-aligned design choices influence user trust and perceived reliability?

- RQ4: What practical reliability lessons emerge from deploying a social robot in a public educational environment?

- 1.

- Empirical Validation in Public Space—It presents one of the first in situ, end-user validations of a lifecycle-based framework for secure and ethical robot deployment, conducted in a real university reception environment.

- 2.

- Societal Insights into Trust, Ethics, and Accessibility—It provides rich qualitative and quantitative evidence showing how users perceive safety, privacy, inclusivity, and transparency when interacting with a public-facing robot, highlighting gaps in accessibility and the role of societal narratives in shaping trust.

- 3.

- Bridging Frameworks and Practice—It demonstrates how theoretical principles of ethical and secure design can be operationalised in practice, offering lessons that extend beyond compliance to anticipatory and inclusive design strategies.

- 4.

- Open-Source Technical Contribution—It delivers a publicly available GitHub repository containing reusable templates and implementation resources for the ARI platform, lowering barriers for beginners in robotics research and enabling reproducibility across institutions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Social Robots in Public Spaces: Contexts and Functions

2.2. Ethics, Privacy, and Responsible Social Robotics

2.3. Cybersecurity Frameworks vs. Embodied, Public-Facing Robots

2.4. Trust, Acceptance, and Transparency in HRI

2.5. Accessibility and Inclusivity in Public Deployments

2.6. From Threat Landscape to Lifecycle Governance: SecuRoPS

2.7. Reproducibility, Tooling, and Entry Barriers

2.8. Positioning This Study

3. Methodology

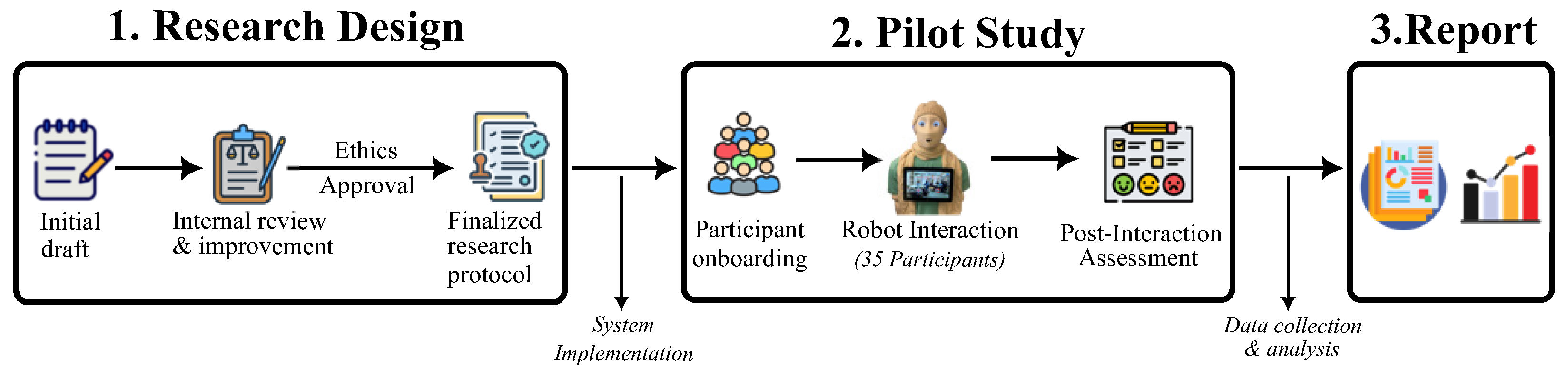

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Ethical Considerations

3.3. Participants

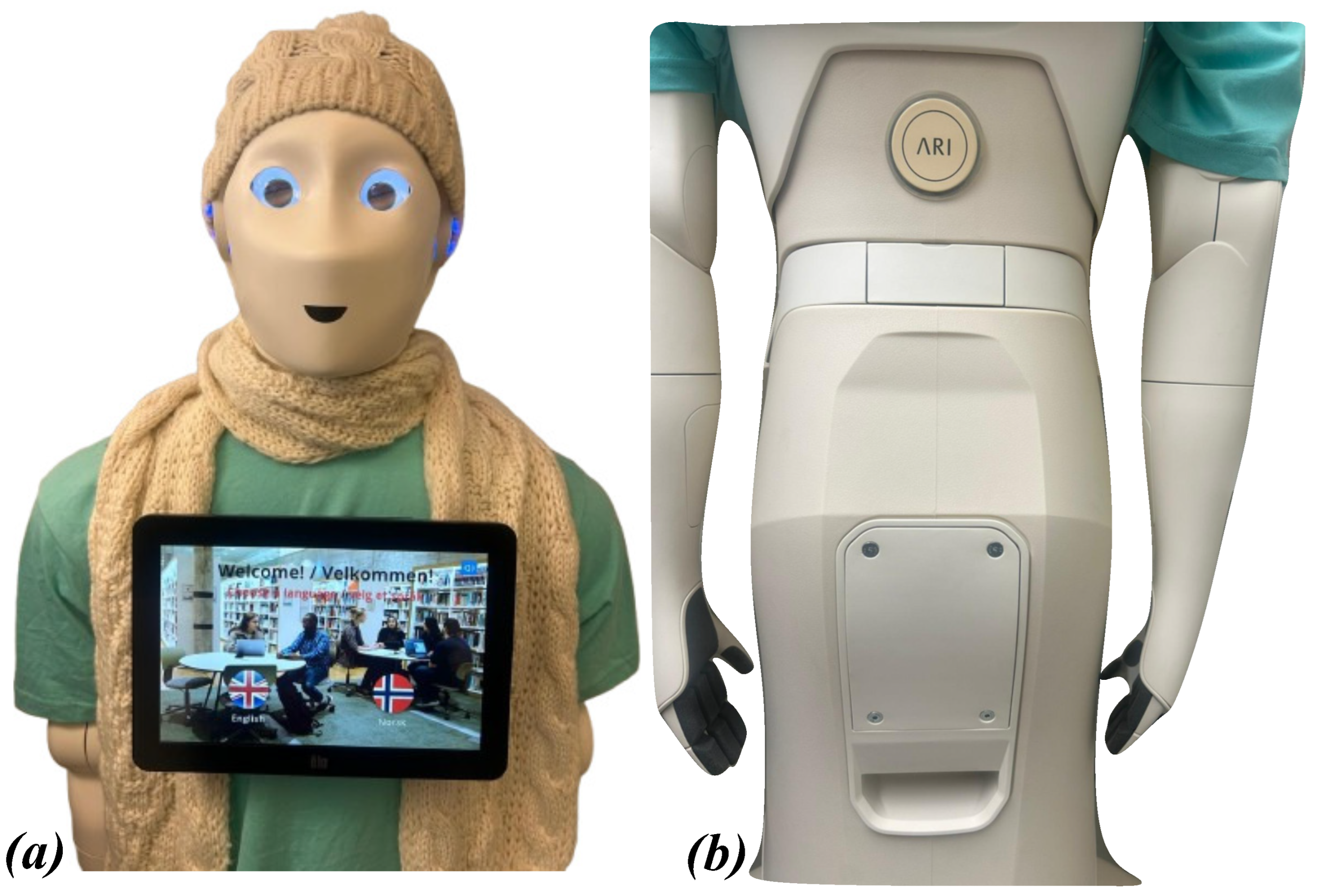

3.4. System Implementation

3.5. Procedure

- Phase 1: Informed Consent. Participants accessed a digital Participant Information Sheet via a QR code and provided informed consent using the Nettskjema platform (see Appendix A).

- Phase 2: Demographic Data Collection. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire covering age, gender, faculty affiliation, and prior experience with social robots via a second secure Nettskjema form (see Appendix B).

- Phase 3: Interaction with the ARI Robot. Participants interacted with the robot as it delivered institutional information using multiple modalities, including web-based presentations, image slideshows, videos, and PowerPoint-style content. Participants were optionally invited to test the virtual keyboard and data-entry functionality, following the interaction guidelines provided in Appendix C.

- Phase 4: Post-Interaction Assessment. Participants completed a structured feedback survey via Nettskjema, assessing perceptions of physical safety, data privacy, physical and cybersecurity protections, interface usability, accessibility, ethical transparency, and GDPR compliance (see Appendix D).

3.6. Data Management and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Participant Demographics

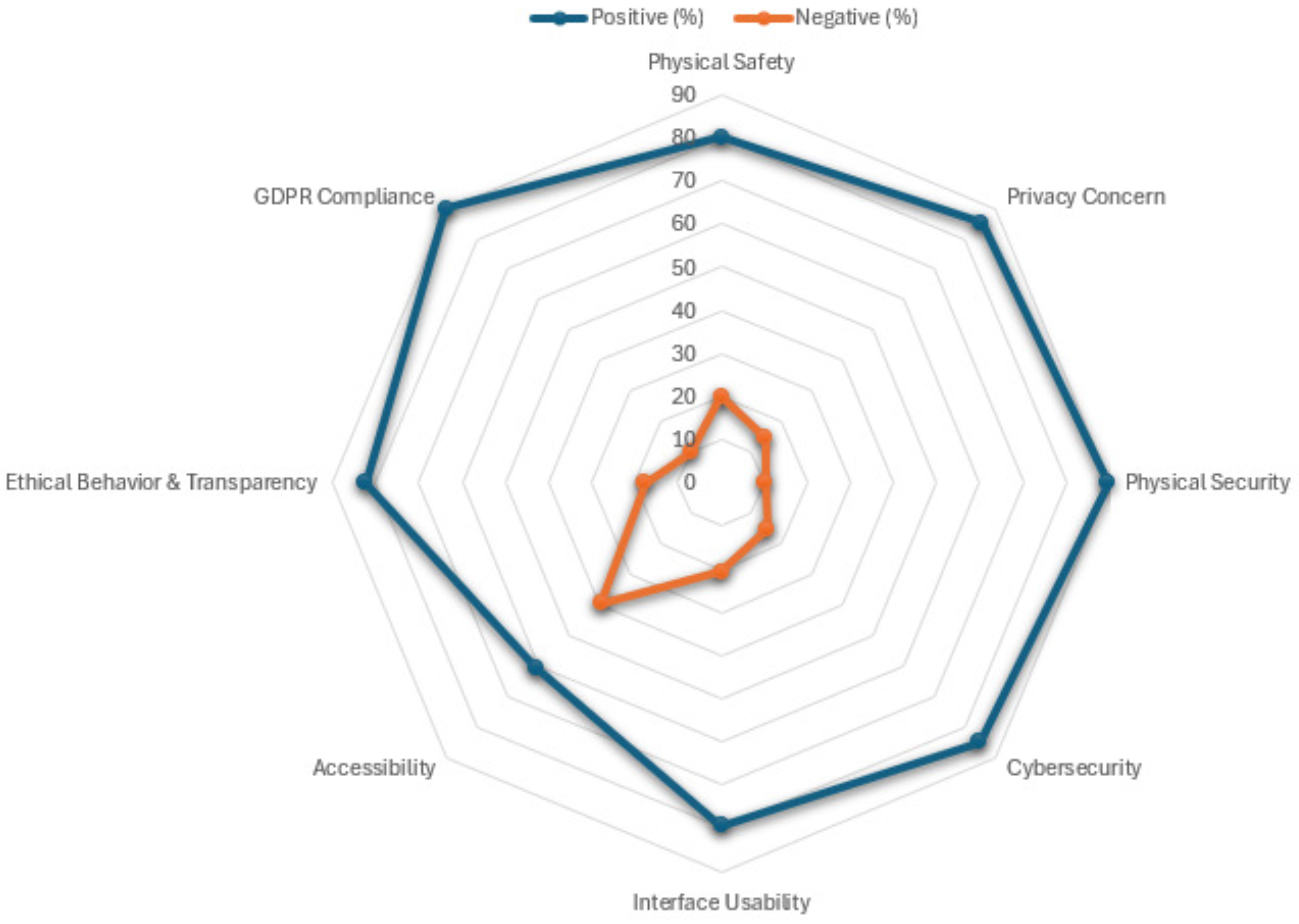

4.2. Quantitative Findings

4.3. Exploratory Comparisons

4.4. Qualitative Insights

- Trust and Perceived Safety: Many participants described the robot as “safe,” “friendly,” and “non-threatening.” The robot’s appearance, stationary deployment, and bilingual interaction were frequently cited as factors contributing to these perceptions. These findings reinforce the importance of physical design cues and multimodal communication in establishing trust.

- Usability and Interaction Flow: While the interface was generally perceived as intuitive, participants suggested improvements such as clearer navigation cues, a larger on-screen keyboard, and a more natural voice. Several respondents recommended incorporating motion or voice control to enhance engagement and reduce the perception of static interaction.

- Accessibility and Inclusivity: Accessibility concerns emerged consistently. Participants highlighted challenges related to screen height for wheelchair users and the absence of alternative input modalities such as speech input or sign language support. These comments indicate that accessibility limitations were not incidental but systematically experienced by certain user groups.

- Transparency in Data Practices: Although participants acknowledged GDPR compliance, several suggested that privacy assurances should be communicated more explicitly during interaction (e.g., through verbal explanations or on-screen prompts). This underscores the importance of visible and ongoing transparency rather than implicit compliance alone.

4.5. Results in Relation to the Research Questions

4.6. Mapping Pilot Study Activities to the SecuRoPS Framework

5. Discussion

5.1. Trust, Safety, and Ethical Transparency

5.2. Accessibility and Inclusivity as a Persistent Sociotechnical Challenge

5.3. Privacy, GDPR, and “Privacy-by-Interaction”

5.4. User Expectations, Bias, and Cultural Narratives

5.5. Interaction Dynamics and the Attention Economy

5.6. Contribution to Responsible Robotics and HRI

5.7. Comparison with Established Security Frameworks

5.8. Reliability and Lessons Learned

5.9. Limitations

5.10. Threats to Validity and Mitigation Measures

- Internal Validity: Social desirability bias may have influenced responses, particularly because the study took place within the participants’ institution, and the researcher was present. This was mitigated through anonymous Nettskjema data collection and reminders that negative feedback was valuable.

- Construct Validity: Concepts such as cybersecurity, privacy, and transparency may be interpreted differently by participants. Survey questions were written in plain language with clarifications distinguishing key constructs, and responses were triangulated with open-ended feedback.

- External Validity: Results are context-dependent and based on a single deployment setting. Participant diversity improved representativeness, but replication across additional public contexts and larger samples is needed.

- Technical Validity: The robot’s limited mobility and expressiveness may have affected perceptions of engagement and utility. These constraints were transparently reported, and participant suggestions were captured as priorities for future iterations. Technical safeguards were consistently enforced, ensuring that perceptions of privacy and security were grounded in actual system behaviour.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Participant Information Sheet

- Title: Real-World Validation of a Human-Centred Social Robot: A University Receptionist Case Study

- Invitation to Participate

- About the Study

- Your Role in the Study

- Voluntary Participation

- Duration of the Study

- Data Collection and Confidentiality

- Benefits and Risks

- Funding

- Further Information and Contact

Appendix B. Participant Demographic Information

- 1.

- Age:□ Under 18, □ , □ , □ , □ , □ Over 55

- 2.

- Gender:□ Male, □ Female, □ Non-binary, □ Prefer not to say

- 3.

- Faculty/Unit:□ Faculty of Health, Welfare and Organisation□ Faculty of Computer Science, Engineering and Economics□ Faculty of Teacher Education and Languages□ Norwegian Theatre Academy□ The Norwegian National Centre for English and other Foreign Languages in Education□ Library□ Other (Please specify)___________________________________________________

- 4.

- Previous Experience with Social Robots (if any):□ None□ Some experience□ Extensive experience

- 5.

- Have you interacted with robots for educational purposes before?□ Yes, □ No

Appendix C. Research Guideline

- Title: Real-World Validation of a Human-Centred Social Robot: A University Receptionist Case Study

- Overview of Research

- Research Procedure

- 1.

- Introduction:

- Greet the participant and provide the Participant Information Sheet digitally via QR code. Obtain informed consent through Nettskjema.

- Provide a second QR code that links to the Participant Demographic Information form on Nettskjema, which participants will complete before interacting with the robot.

- 2.

- Robot Interaction: The participant will interact with the robot, providing information about the university and local events.

- 3.

- Post-Interaction Assessment: The participant will complete the feedback form, focusing on selected aspects of the SecuRoPS framework.

- 4.

- Feedback Collection: Collect and anonymize the data.

- 5.

- Data Handling: All data will be securely stored in Nettskjema and Østfold University Office 365 OneDrive, and will be used exclusively for research purposes.

- Ethical Considerations

- Maintain participant confidentiality.

- Ensure transparency in the robot’s functionalities and data collection practices.

Appendix D. Post-Interaction Assessment Survey

- 1.

- Based on your experience and interaction with the robot ARI, do you perceive physical safety as one of the main characteristics of the robot? □ Yes, □ NoIf so, where?_________________________________________________________If not, how can the physical safety of users be improved?______________________________________________________________________________________

- 2.

- Based on your interaction and experience with the robot and the information provided, do you feel that your privacy is at risk due to ARI’s data handling?□ Yes, □ NoIf so, why?__________________________________________________________If not, how do you think the robot’s data handling could be better managed?____________________________________________________________________

- 3.

- Assume that ARI’s design prevents access through WiFi or any other wireless means. Do you think the robot’s implementors adopted ways to prevent it from physical tampering? Take a look at ARI, including from behind. □ Yes, □ NoIf so, how?__________________________________________________________If not, how can the physical non-tampering of the robot be enhanced?__________________________________________________________________________

- 4.

- Based on your interaction with ARI, can you see any perceived cybersecurity vulnerabilities in the robot design that could be exploited during interaction with users? □ Yes, □ NoIf so, how?__________________________________________________________If not, which cybersecurity vulnerabilities should be addressed?_______________________________________________________________________________

- 5.

- Based on your experience and interaction with ARI, do you think the robot has an acceptable interface usability? □ Yes, □ NoIf so, how?__________________________________________________________If not, how can the usability of this robot be improved?_______________________________________________________________________________________

- 6.

- Based on your interaction with the robot, do you think it accommodates diverse user needs in terms of accessibility? □ Yes, □ NoIf so, how?__________________________________________________________If not, how can the usability of this robot be improved?_______________________________________________________________________________________

- 7.

- Based on your experience with the robot today, do you think ARI demonstrates ethical behaviour (e.g., giving misleading or biased information) and transparency in data collection? □ Yes, □ NoIf so, how?__________________________________________________________If not, how can compliance with ethical guidelines and transparency in data collection be improved?____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 8.

- Based on your interaction with the robot, do you think the robot is complying with applicable privacy laws like GDPR? □ Yes, □ NoIf so, how?__________________________________________________________If not, how can legal compliance be improved?______________________________________________________________________________________________

| 1 | https://sikt.no/ (accessed on 23 February 2025). |

References

- Khan, M.U.; Erden, Z. A Systematic Review of Social Robots in Shopping Environments. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 9565–9586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Yeo, S.J.I. Airport Robots: Automation, Everyday Life and the Futures of Urbanism. In Artificial Intelligence and the City; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ragno, L.; Borboni, A.; Vannetti, F.; Amici, C.; Cusano, N. Application of Social Robots in Healthcare: Review on Characteristics, Requirements, Technical Solutions. Sensors 2023, 23, 6820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G. Social Robots in Education: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Information 2025, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rødsethol, H.K.; Ayele, Y.Z. Social Robots in Public Space; Use Case Development. In Proceedings of the Book of Extended Abstracts for the 32nd European Safety and Reliability Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 28 August–1 September 2022; Research Publishing Services: Singapore, 2022; pp. 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruma, S.O.; Ayele, Y.Z.; Sechi, F.; Rødsethol, H. Security Aspects of Social Robots in Public Spaces: A Systematic Mapping Study. Sensors 2023, 23, 8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruma, S.O.; Sánchez-Gordón, M.; Gkioulos, V. Enhancing Security, Privacy, and Usability in Social Robots: A Software Development Framework. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2026, 96, 104052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaurock, M.; Čaić, M.; Okan, M.; Henkel, A.P. A Transdisciplinary Review and Framework of Consumer Interactions with Embodied Social Robots: Design, Delegate, and Deploy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1877–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callari, T.C.; Vecellio Segate, R.; Hubbard, E.M.; Daly, A.; Lohse, N. An Ethical Framework for Human-Robot Collaboration for the Future People-Centric Manufacturing: A Collaborative Endeavour with European Subject-Matter Experts in Ethics. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, K.; Shahriari, M. IEEE Standard Review—Ethically Aligned Design: A Vision for Prioritizing Human Wellbeing with Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Canada International Humanitarian Technology Conference (IHTC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 20–22 July 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nist, G.M. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0; Technical Report NIST CSWP 29 ipd; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MITRE. MITRE ATT&CK. 2025. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Jiang, D.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y. Mastering the Complex Assembly Task with a Dual-Arm Robot: A Novel Reinforcement Learning Method. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2023, 30, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruma, S.O. Towards a User-centred Security Framework for Social Robots in Public Spaces. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Oulu, Finland, 14–16 June 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruma, S.; Colomo-Palacios, R.; Gkioulos, V. Architectural Views for Social Robots in Public Spaces: Business, System, and Security Strategies. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2025, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, M.; Pamucar, D.; Gokasar, I.; Zaidan, B.B.; Martinez, L.; Pedrycz, W. Assessing Alternatives of Including Social Robots in Urban Transport Using Fuzzy Trigonometric Operators Based Decision-Making Model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 122743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subero-Navarro, Á.; Pelegrín-Borondo, J.; Reinares-Lara, E.; Olarte-Pascual, C. Proposal for Modeling Social Robot Acceptance by Retail Customers: CAN Model + Technophobia. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, D.; Cirasa, C.; Høgsdal, H.; Di Nuovo, S.F. The Use of Social Robots in Educational Settings: Acceptance and Usability. In Social Robots in Education: How to Effectively Introduce Social Robots into Classrooms; Lampropoulos, G., Papadakis, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torras, C. Ethics of Social Robotics: Individual and Societal Concerns and Opportunities. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock-Homburg, R.M.; Kegel, M.M. Ethical Considerations in Customer–Robot Service Interactions: Scoping Review, Network Analysis, and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2025, 17, 1129–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.; Zhao, Y.; Alfares, H.; Shafiekhani, P. Ethical Considerations in the Use of Social Robots for Supporting Mental Health and Wellbeing in Older Adults in Long-Term Care. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 12, 1560214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callander, N.; Ramírez-Duque, A.A.; Foster, M.E. Navigating the Human-Robot Interaction Landscape. Practical Guidelines for Privacy-Conscious Social Robots. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Boulder, CO, USA, 11–15 March 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staab, R.; Jovanović, N.; Balunović, M.; Vechev, M. From Principle to Practice: Vertical Data Minimization for Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–23 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 4733–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockheed Martin Corporation. Cyber Kill Chain™. Online Resource. 2025. Available online: https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/capabilities/cyber/cyber-kill-chain.html (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Möller, D.P.F. NIST Cybersecurity Framework and MITRE Cybersecurity Criteria. In Guide to Cybersecurity in Digital Transformation: Trends, Methods, Technologies, Applications and Best Practices; Möller, D.P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 231–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Ying, L.; Chen, L.; Duan, H.; Liu, M.; Xue, Z. Dr. Docker: A Large-Scale Security Measurement of Docker Image Ecosystem. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference, Sydney, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 2813–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Gu, H.; Ling, X.; Ye, W.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z. Understanding Trust and Rapport in Hotel Service Encounters: Extending the Service Robot Acceptance Model. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2024, 15, 842–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Li, Y.; Miah, S.; Liu, W. Customer Acceptance of Frontline Social Robots—Human-robot Interaction as Boundary Condition. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 199, 123035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekçetin, T.N.; Evsen, S.; Pekçetin, S.; Acarturk, C.; Urgen, B.A. Real-World Implicit Association Task for Studying Mind Perception: Insights for Social Robotics. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Boulder, CO, USA, 11–15 March 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaguer Gómez, G. Should We Trust Social Robots? Trust without Trustworthiness in Human-Robot Interaction. Philos. Technol. 2025, 38, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barfield, J. Designing Social Robots to Accommodate Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Human Information Interaction and Retrieval, Austin, TX, USA, 19–23 March 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruma, S.O.; Sánchez-Gordón, M.; Colomo-Palacios, R.; Gkioulos, V.; Hansen, J.K. A Systematic Review on Social Robots in Public Spaces: Threat Landscape and Attack Surface. Computers 2022, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L.; Johny, A. Robot Operating System (ROS) for Absolute Beginners: Robotics Programming Made Easy; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radley-Gardner, O.; Beale, H.G.; Zimmermann, R. (Eds.) Fundamental Texts on European Private Law, 2nd ed.; Hart Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruma, S. ARI—Ostfold-University-College-Robot-Receptionist; Østfold University College: Halden, Norway, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, F.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Sheng, L.; Zhu, D.; Zhao, J.; Gu, Z. Crossmodal Interactions in Human-Robot Communication: Exploring the Influences of Scent and Voice Congruence on User Perceptions of Social Robots. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 26 April–1 May 2025; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.L.; Scholz, C.; De Winter, J.; Makrini, I.E.; Vanderborght, B. Investigating the Role of Multi-modal Social Cues in Human-Robot Collaboration in Industrial Settings. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2023, 15, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.S.; Marshall, A.; Arora, A.; McIntyre, J.R. Virtuous Integrative Social Robotics for Ethical Governance. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnert, M. Ability and Disability: Social Robots and Accessibility, Disability Justice, and the Socially Constructed Normal Body. In The De Gruyter Handbook of Robots in Society and Culture; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Volume 3, p. 429. [Google Scholar]

- de Saille, S.; Kipnis, E.; Potter, S.; Cameron, D.; Webb, C.J.R.; Winter, P.; O’Neill, P.; Gold, R.; Halliwell, K.; Alboul, L.; et al. Improving Inclusivity in Robotics Design: An Exploration of Methods for Upstream Co-Creation. Front. Robot. AI 2022, 9, 731006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorafshanian, M.; Aitsam, M.; Mejri, M.; Di Nuovo, A. Beyond Data Collection: Safeguarding User Privacy in Social Robotics. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Bristol, UK, 25–27 March 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, L. Homes as Human–Robot Ecologies: An Epistemological Inquiry on the “Domestication” of Robots. In The Home in the Digital Age; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Arduengo, M.; Sentis, L. The Robot Economy: Here It Comes. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2021, 13, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogiannis, C.; Baldini, F.; Wang, A.; Zhao, D.; Trautman, P.; Steinfeld, A.; Oh, J. Core Challenges of Social Robot Navigation: A Survey. ACM Trans. Hum.-Robot Interact. 2023, 12, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, C.; Hoda, R.; Feldt, R. Qualitative Research Methods in Software Engineering: Past, Present, and Future. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2025, 51, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjøberg, D.I.K.; Bergersen, G.R. Construct Validity in Software Engineering. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2023, 49, 1374–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evaluation Criteria | Positive (%) | Negative (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Safety | 80.0 | 20.0 |

| Privacy Concern | 85.3 | 14.7 |

| Physical Security | 89.7 | 10.3 |

| Cybersecurity | 84.8 | 15.2 |

| Interface Usability | 79.4 | 20.6 |

| Accessibility | 60.6 | 39.4 |

| Ethical Behaviour & Transparency | 82.4 | 17.6 |

| GDPR Compliance | 90.0 | 10.0 |

| SecuRoPS Phases | Pilot Study Activity |

|---|---|

| Business Needs Assessment | Identified the need for evaluating secure, ethical, and inclusive deployment of a social robot in an educational setting. |

| Evaluation of SRPS Application Context | Østfold University College was selected as a realistic and relevant public space for deployment. |

| Robot Type Selection | ARI robot chosen based on its capabilities, compatibility with Docker, and development environment constraints. |

| Stakeholder Engagement and Dialogue | Collaboration with the university communication department and ethics committee (Sikt) to ensure alignment and compliance. |

| Feasibility and Impact Analysis | Considered accessibility needs, user privacy concerns, and potential institutional benefits. |

| Requirement Specification | Developed application requirements for multilingual support, audio/visual interaction, secure data handling, and usability. |

| Risk Assessment & Threat Modelling | Security risks mitigated through covered ports, VPN/firewall, and stationary operation. Data minimization enforced through design. |

| Proven Methodology-Driven Design | Followed PAL Robotics SDK implementation methods and guidelines for structured application design. |

| Implementation of Security, Safety, and User-Centeredness Measures | Built secure HTML/CSS/JS-based UI; implemented overlay navigation, visual/audio aids, and GDPR-aligned data collection process. |

| User Experience, Usability, and Security Testing | Post-interaction surveys and direct observation provided feedback on trust, safety, and accessibility. |

| Ethical, Legal, and Regulatory Scrutiny | Received formal approval from Sikt; data handling compliant with Norwegian data protection laws. |

| Strategic Deployment | Robot deployed in a public-facing location at the university with pre-programmed interactive content. |

| Continuous Monitoring and Iterative Improvement | On-site observations and usability feedback recorded for future design improvements. |

| Retrospective and Lessons Learned | Reflections incorporated into recommendations and design templates published with the study. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oruma, S.O.; Colomo-Palacios, R.; Gkioulos, V. From Framework to Reliable Practice: End-User Perspectives on Social Robots in Public Spaces. Systems 2026, 14, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020137

Oruma SO, Colomo-Palacios R, Gkioulos V. From Framework to Reliable Practice: End-User Perspectives on Social Robots in Public Spaces. Systems. 2026; 14(2):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020137

Chicago/Turabian StyleOruma, Samson Ogheneovo, Ricardo Colomo-Palacios, and Vasileios Gkioulos. 2026. "From Framework to Reliable Practice: End-User Perspectives on Social Robots in Public Spaces" Systems 14, no. 2: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020137

APA StyleOruma, S. O., Colomo-Palacios, R., & Gkioulos, V. (2026). From Framework to Reliable Practice: End-User Perspectives on Social Robots in Public Spaces. Systems, 14(2), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020137