Abstract

Among existing preference elicitation methods, the trade-off method offers an advantage over others in mitigating the influence of probability weighting on preferences, as it does not require assuming a specific form for the probability weighting function. However, when accounting for the dependence of probability weighting on the choice-set outcome range (CSOR), the conventional trade-off method may lead to improper elicitation of preferences due to its inability to control the CSOR. In order to concurrently circumvent the impacts of the CSOR and probability weighting on preferences in the elicitation procedure, we introduce the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method (RFTM) and provide its full derivation and concrete implementation steps under the framework of rank-dependent utility theory (RDU). The RFTM not only retains the advantages of the conventional trade-off method but also evades the effects of the CSOR on preferences by fixing the CSOR. The results of empirical investigations into the efficacy of RFTM indicate that, compared to the existing trade-off method, utility functions derived from RFTM exhibit a lower degree of risk aversion. This result is compatible with existing experimental observations and conclusions, thus implying that RFTM can effectively elicit individual preferences, thereby preventing or mitigating the bias in preferences arising from CSOR variations in the conventional trade-off approach. Furthermore, the experimental results demonstrate that the probability weighting function remains nonlinear even within a fixed CSOR. This indicates that, under the premise of preferences depending on the CSOR, non-expected utility theories still hold promising development prospects in the future. In summary, RFTM not only provides a more effective and reliable approach for preference elicitation but also makes it feasible to study the impact of changes in the CSOR on preferences, thereby providing methodological support for the future development of CSOR-dependent non-expected utility theories.

Keywords:

risk decision-making; trade-off method; preference elicitation; choice-set outcome range; rank-dependent utility theory (RDU) JEL Classification:

D81; G41

1. Introduction

In risky decision-making, accurately measuring individual preferences forms the foundation for building and applying theoretical models. This measurement converts abstract subjective utilities into quantifiable data, supporting the development, validation, and implementation of risk decision theories. Yet, elicitation methods inherently rely on underlying theoretical models, necessitating their refinement as theories evolve. Specifically, when individuals confront choice sets comprising prospects (i.e., outcome probability distributions), expected utility theory (EUT) was traditionally viewed as adequately explaining choice behavior [1,2]. Consequently, drawing on the basic assumption proposed by EUT that preferences are linear with respect to probabilities, scholars developed preference elicitation methods such as certainty-equivalent methods and probability-equivalent methods [3,4]. However, behavioral phenomena such as the Allais paradox [5] that systematically deviate from EUT indicate that decision-makers’ preferences do not exhibit linear characteristics with respect to probabilities, and this has given rise to non-expected utility theories (non-EUT theories) represented by rank-dependent utility theory (RDU) and cumulative prospect theory (CPT) [6,7,8]. The core innovation of such non-EUT theories is manifested in the introduction of a probability weighting function into the utility model.

Probability weighting refers to individuals’ subjective distortion of objective probabilities in risky decision-making and is used to explain the nonlinear characteristics of individual preferences with respect to probabilities [9]. Although certainty- and probability-equivalent methods remain applicable under RDU and some other non-expected utility frameworks, they require presuming a parametric form for the probability weighting function. However, such assumed forms may mismatch actual weighting functions, leading to systematic biases in elicited preferences [10]. To solve the above problems, Wakker and Deneffe [4] introduced trade-off methods, which hold probabilities fixed across series preference elicitation tasks, thereby avoiding the influence of probability weighting on preference measurement.

Notably, the conventional trade-off method embeds a core assumption which most non-EUT theories like RDU hold too: probability weighting is independent of the choice-set outcome range (CSOR) [11,12,13,14]. However, empirical evidence has cast doubt on this assumption. Abdellaoui [15] found that the probability weighting function for gains differs from that for losses, and that the former curve lies below the latter. For losses, Etchart-Vincent [16] observed that probability weights decline with increases in outcome magnitude. Wu and Markle [17] showed that the double-matching principle implied by the assumption that probability weights are separable from the CSOR fails empirically. Examining the “stake effect” with gains outcomes, Fehr-Duda et al. [18] demonstrated through parametric fitting that the influence of outcome magnitude on preferences cannot be explained by outcome utility alone, but rather by the dependence of probability weighting on outcome magnitude. They found that probability weights are greater for smaller outcomes compared to larger ones. Although none of these studies rigorously controlled the CSOR, their coarse categorizations of outcomes (large vs. small; gains vs. losses) indirectly indicate that probability weights depend on the CSOR.

The dependence of probability weights on the CSOR challenges the validity of existing preference elicitation methods. Specifically, while certainty-equivalent and probability-equivalent methods can elicit preferences within a fixed CSOR, they induce systematic elicitation bias because they presuppose a probability weighting function. Although the trade-off method obviates the need to assume a parametric form for the probability weighting function, its chained-question design expands the CSOR as elicitation progresses. Consequently, even with probabilities held fixed during elicitation, the same probability receives different weights across choice problems, rendering the conventional trade-off method ill-suited for accurate preference measurement. Taken together, these points expose a methodological dilemma: as scholarship increasingly acknowledges that probability weighting depends on the CSOR, current methods cannot both hold the CSOR fixed and avoid parametric functional-form assumptions, thereby jeopardizing the validity of preference measurement.

To address the above methodological impasse, we develop the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method (RFTM), an enhancement of the conventional trade-off method. RFTM offers three key advantages. First, it holds the CSOR fixed throughout the entire preference elicitation process, removing potential confounding of probability weighting by variation in the CSOR. Second, within a fixed CSOR, it enables separate estimation of the utility function and the probability weighting function, thereby achieving separability between the two to some extent. Third, RFTM does not rely on a specific decision theory (e.g., EUT, RDU, or CPT) and is compatible with any decision model that adopts weighted utility maximization as its decision criterion. Accordingly, RFTM delivers two primary theoretical contributions. First, by holding the CSOR fixed and avoiding ex ante functional-form assumptions for probability weighting, it offers a tool for precise preference elicitation. Second, by fixing the CSOR to separate outcome utility from probability weights, it establishes a methodological basis for developing CSOR-dependent non-EUT theories. On the applied side, RFTM enables more robust behaviorally informed policy design—for example, in insurance pricing and public risk management—thereby reducing decision errors stemming from preference elicitation bias.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews RDU and the conventional trade-off method, clarifying the theoretical foundations of RFTM. Section 3 details the construction of RFTM, explains how it improves on the conventional trade-off method, and presents key implementation guidelines. Section 4 designs and implements an experiment to elicit utility functions and probability weights based on the two preference elicitation methods and uses them to validate RFTM’s effectiveness. Section 5 analyzes the differences in curvature between the two utility functions and analyzes the forms of the two probability weighting functions. Section 6 discusses how RFTM and our other findings inform and advance the development of theories of risk decision-making.

2. Theoretical Foundations

Although both the conventional trade-off method and RFTM can be applied under EUT, CPT, and RDU, presenting their derivations requires committing to a specific decision model. Because RDU collapses to EUT when the probability weighting function is linear, and coincides with CPT for prospects with gain (or loss) outcomes, we present both the conventional trade-off method and RFTM within the RDU framework, focusing on gain prospects where all outcomes are nonnegative.

2.1. Rank-Dependent Utility Theory (RDU)

To account for the common consequence effect and other behavior effects which depart from EUT, the original prospect theory maps individual probabilities to decision weights, under which people overweight small probabilities and underweight moderate/high probabilities [19]. It should be noted that the meaning of decision weights differs substantially across decision domains. In the context of multi-attribute decision-making, decision weights typically refer to attribute weights, which are used to aggregate the utilities of different attributes [20,21]. In contrast, in the domain of risky decision-making, decision weights correspond to the weights assigned to each outcome in a prospect; within the analytical framework of prospect theory, they are monotonic functions of single objective probabilities. However, using decision weights based on single probabilities can violate first-order stochastic dominance (FSD). Quiggin [6] introduced RDU to resolve this problem. RDU applies probability weights to cumulative probabilities, from which decision weights are constructed.

A prospect (also called a lottery) is a probability distribution over a finite outcome set . For instance, comprises k outcomes with for , ordered and . Under RDU, the utility of a prospect P is defined as

Here, denotes the utility function and the decision weights. Decision weights derive from the probability weighting function : for , ; for , . (There are two paradigms for the specification of decision weights , whose fundamental difference lies in whether the weighting is based on the cumulative distribution or the decumulative distribution. When Quiggin [6] proposed RDU, decision weights were defined as transformations of the cumulative distribution. Subsequently, in developing CPT, Tversky and Kahneman [7] redefined decision weights as transformations of the decumulative distribution, which has been widely adopted in subsequent studies [15,18]. Accordingly, the present study follows the dominant paradigm established by Tversky and Kahneman [7] and specifies decision weights as functions of decumulative probabilities.) Hence, depends both on and on the rank position of among the outcomes. Note that if for all , RDU collapses to EUT as a special case.

2.2. The Conventional Trade-Off Method

The conventional trade-off method leverages indifferences between two-outcome prospects to directly elicit utility functions and probability weighting functions [4,15]. To elicit the utility function, begin by constructing prospects and , with known , , , and satisfying and . Next, ask the decision-maker to provide the outcome value that renders and indifferent. Under RDU, this indifference holds if

Once is elicited, update by replacing with and by replacing with , and then elicit such that and are indifferent. Analogously, this indifference yields

From (2) and (3), it follows that , meaning the utility difference between outcomes and equals the utility difference between and . Iterating this process yields a standard outcome sequence . In this sequence, utility differences between adjacent outcomes are constant. Normalizing with and implies for . Once the utility function is elicited, proceed to elicit the probability weighting function. Specifically, using the standard outcome sequence, elicit probabilities () such that is indifferent to the sure outcome . Under RDU, this implies . The sequence constitutes the standard probability sequence, with constant weighting differences between adjacent values.

3. Range-Fixed Trade-Off Method (RFTM)

As discussed above, the conventional trade-off method does not hold the choice-set outcome range (CSOR) fixed during the elicitation of the standard outcome sequence. If the variation in CSOR influences probability weighting, the same probability will receive different decision weights across choice problems. Consequently, for the outcome sequence elicited by the conventional trade-off method, the utility differences between adjacent outcomes are not the same, and the probability sequence inferred from it is not a genuine standard sequence. To address this concern, we advance the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method (RFTM), building on the conventional trade-off approach. For ease of exposition, we introduce the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method using pure-gain prospects as an example.

3.1. The Construction of RFTM

This study modifies the conventional trade-off method by (i) moving from two- to three-outcome prospects and (ii) keeping the maximum and minimum outcomes fixed across prospect pairs corresponding to different choice problems, which keeps the CSOR constant throughout the elicitation of the standard outcome sequence. The details of the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method are as follows.

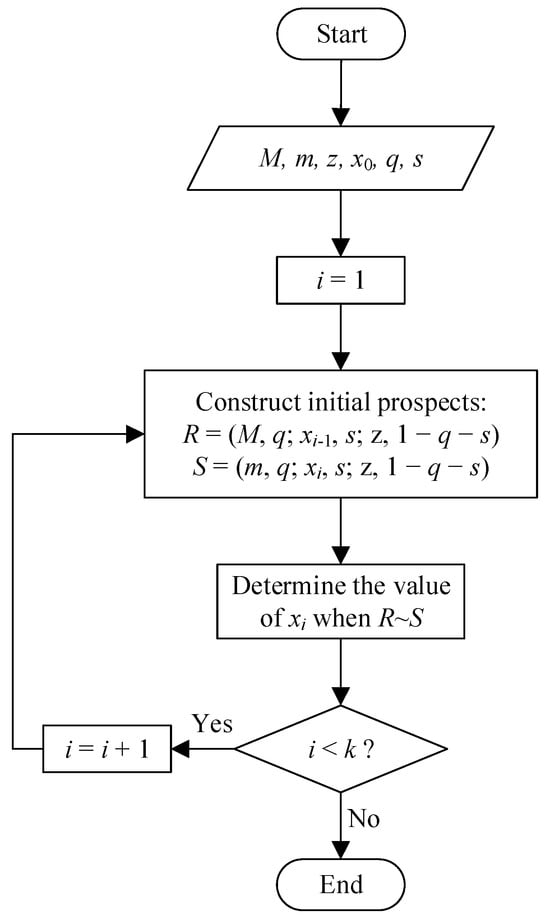

Using the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method, outcome utilities and probability weights can be elicited sequentially. To elicit outcome utilities, as illustrated in Figure 1, first construct two initial prospects and , where the outcomes , , , and the probabilities , are given, is unknown, and . Then ask the decision-maker to provide the outcome that renders them indifferent between and . Under RDU, this indifference implies

Figure 1.

Procedure for eliciting the standard outcome sequence using RFTM.

Here, and . Once is obtained, as shown in Figure 1, update by replacing with and update by replacing with ; then elicit that makes and indifferent. Under RDU, this indifference yields

Combining (4) and (5) yields , i.e., the utility difference between and equals that between and . As illustrated in Figure 1, by repeating the above procedure, outcome values can be successively obtained, where . The elicited values are referred to as a standard outcome sequence, in which the utility differences between adjacent outcomes are equal, that is, for , . With normalization and , we have for .

To elicit probability weights, given the elicited standard outcome sequence, the decision-maker is asked to indicate the probability value () that renders indifferent to . Under RDU, this implies

This procedure yields the standard probability sequence , with for .

3.2. Implementation Guidelines for RFTM

From the construction of the RFTM, it follows that eliciting preferences first requires eliciting a standard outcome sequence. The maximal length of this sequence depends closely on the chosen outcomes and probabilities in the two initial prospects. Consider a standard outcome sequence with elements . It is known that , where , . If , concavity of (diminishing marginal utility) implies

Moreover, concavity further yields

To guarantee elicitable outcomes within , impose

Since , and , the function increases in . Hence, combining (9) with implies

From (9), fixing and , a smaller permits a larger —i.e., a longer standard sequence. Note that, since , reducing corresponds to increasing . Thus, for fixed , choosing smaller and/or larger increases the attainable sequence length.

In short, to obtain a sequence of length , (i) satisfy ; (ii) choose with so that []. If the resulting sequence is shorter than , further reduce and/or raise until at least outcomes are obtained.

As mentioned earlier, the RFTM proposed in this paper within the RDU framework is equally applicable to other theories that adopt weighted utility maximization as the decision criterion, such as CPT and original prospect theory. These theories all assume that the outcome utility function and the probability weighting function are unique, in the sense that they do not vary with the CSOR.

The RFTM proposed in this paper is designed to address the characteristic that the probability weighting function depends on the CSOR, without considering the possibility that the outcome utility function may also depend on the CSOR. However, even if the utility function depends on the CSOR, the RFTM remains applicable. In this case, the standard outcome sequence elicited via the RFTM must satisfy the condition that the minimum outcome and the maximum outcome correspond to the two endpoints of the CSOR (i.e., and , respectively). To meet this requirement, one can directly set and then, similar to the procedure described above, adjust the probability and/or to ensure that . Specifically, when , one can increase and/or decrease until ; when (i.e., when the number of elements in the standard outcome sequence is fewer than ), one can decrease and/or increase until (at which point the standard outcome sequence contains exactly elements).

It should be noted that, from a prescriptive perspective, although the approach of adjusting probabilities is theoretically feasible, it may entail substantial cognitive costs. In light of this, under the premise that the outcome utility function depends on the CSOR, the RFTM can be further developed into to a semiparametric method. Specifically, after eliciting the standard outcome sequence via the RFTM, a parametric method is first used to fit the outcome utility function. The utility values of each outcome in the standard outcome sequence are then determined based on the fitted utility function. Finally, on this basis, the standard probability sequence is elicited nonparametrically.

4. Experiment: Validation of the Effectiveness of RFTM

As noted above, a growing body of literature shows that probability weights depend on the choice-set outcome range (CSOR). For instance, Etchart-Vincent [16] shows in the loss domain (nonpositive outcomes) that when outcomes rise (the absolute magnitude of the nonzero outcome shrinks), the decision weights on the better outcome increase. Likewise, Fehr-Duda et al. [18] find for gains (nonnegative outcomes) that the probability weighting function curve—apart from its endpoints—shifts upward as outcomes decrease. These findings consistently indicate that probability weights are markedly larger when the CSOR is narrow than when it is wide.

Taking the case of the gain domain as an example, if probability weights rise as the CSOR narrows, then when using the conventional trade-off method to elicit the standard outcome sequence, the decision weight assigned to a given probability will fall as the CSOR expands during elicitation. From (2), this implies that utility gaps between adjacent outcomes in the purported “standard sequence” grow along the elicitation. Consequently, the resulting utility function is more curved (i.e., overstating risk aversion) relative to the true utility. Moreover, although the conventional trade-off method can keep the CSOR fixed when eliciting probability weights, the elicited standard outcome sequence is invalid, rendering the derived probability weights invalid as well. In short, accurately eliciting the utility function is pivotal for reliable preference elicitation.

Given that RFTM can hold the CSOR fixed throughout elicitation, it more effectively elicits the utility function. Relative to the conventional trade-off method, the utility function obtained under RFTM should exhibit lower curvature. Accordingly, we assess RFTM’s effectiveness by comparing the utility functions it yields to those obtained via the conventional trade-off method. We also examine whether, within a fixed CSOR, the probability weighting function is linear, as assumed by Baucells et al. [22] and Kontek and Lewandowski [12], by eliciting a standard probability sequence with RFTM and analyzing the resulting function’s form.

4.1. Subjects

The required sample size was computed using G*Power 3.1 [23]. Setting statistical power , significance level , and effect size (Cohen’s d) , the required sample size was 51. Accordingly, a total of 55 subjects were recruited for this experiment, where 47% were male, and the mean age was 21.09 ± 0.78 years. None had prior experience with risk decision experiments. Each received a USB drive valued at 25 CNY as compensation.

4.2. Methods and Stimuli

This study aims to test the effectiveness of the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method (RFTM) by comparing the utility functions elicited by it and by the conventional trade-off method. To this end, a within-subject design was adopted with two sub-experiments: Sub-Experiment A used the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method, and Sub-Experiment B used the conventional trade-off method. All subjects completed both sub-experiments and produced a standard outcome sequence and a standard probability sequence.

The experimental stimuli comprised two sets aligned with Sub-Experiments A and B. For Sub-Experiment A, stimuli were dynamically updated from the initial prospects and based on subjects’ choices, hence constructing the stimuli amounts to specifying the values of outcomes and probabilities . Targeting a 6-element standard outcome sequence, following the operational guidance above, we selected CNY, CNY, CNY, CNY, , and .

Similarly, stimuli for Sub-Experiment B were iteratively adjusted from the initial prospects and based on subjects’ choices. Hence, constructing the stimuli amounts to specifying outcomes and probability . In line with Abdellaoui [15], we used , CNY, CNY, and CNY.

4.3. Procedure

The experiment was programmed and administered via z-Tree 5.1.11 [24] in a lab equipped with multiple computer terminals. Prior to the main experiment, subjects completed a practice question and explained their responses to verify comprehension of the choice tasks. Once understanding was confirmed, the main experiment commenced.

The experiment consists of two sub-experiments, A and B, corresponding to the RFTM and the conventional trade-off method, respectively. Each sub-experiment elicits one standard outcome sequence containing six elements (i.e., ) and one standard probability sequence containing five elements (i.e., ).

In Sub-Experiment A, during the elicitation of the standard outcome sequence, participants are repeatedly asked to determine the value that renders them indifferent between prospect and prospect . During the elicitation of the standard probability sequence, participants are repeatedly asked to determine the probability that renders them indifferent between prospect and prospect . Compared with directly asking participants to state indifference values, indifference values obtained through choice-based elicitation tasks are more reliable [15,25]. Accordingly, a bisection procedure is adopted to design the choice tasks, and indifference values are inferred from participants’ choices.

The elicitation of serves as an illustrative example of the bisection procedure. First, two initial prospects are constructed, i.e., and , where is the value of that renders and indifferent. Given that , the lower bound of the initial interval containing is set to , and the upper bound is set to . The midpoint is then used in prospect , and participants are asked to choose the more attractive prospect between and . If the participant chooses prospect , then , and the lower bound is updated to ; if the participant chooses prospect , then , and the upper bound is updated to . The value of in prospect is subsequently updated using the bisection rule (i.e., ), and the participant is again asked to choose between the two prospects. Following the existing literature, after five iterations, the midpoint of the resulting interval is taken as the value of [15]. Once is determined, the same procedure is used to elicit .

Based on the elicited standard outcome sequence, the bisection procedure is further applied to determine the probability that renders participants indifferent between and , thereby obtaining the standard probability sequence . In line with prior studies, the number of iterations required to determine each probability value is set to six [15].

In Sub-Experiment B, similar to Sub-Experiment A, subjects were first asked to choose between the initial prospect and the prospect constructed using the bisection method based on the initial prospect, where . If the subject chose prospect , implying , we updated and repeated the operation; else, and repeated the operation. After 5 iterations, the program then recorded the midpoint of the final interval where lies as . We updated by replacing (i.e., 200 CNY) with , and proceeded to elicit through . Then, we elicited () for indifference between and , with 6 bisection iterations each.

As such, eliciting each () required 5 choices per subject, while each () required 6 choices. To assess data reliability, after eliciting both standard outcome sequence and standard probability sequence, subjects re-answered the fourth question for each element in both sequences.

To minimize possible order effects, this study took two measures. First, the two sub-experiments were separated by one week to reduce subjects’ memory of the first sub-experiment. Second, the implementation order of the two sub-experiments was randomized for each subject.

5. Results

5.1. Reliability

We assessed reliability through the consistency of subjects’ repeated choices on identical problems. Descriptive statistics revealed choice reversals in 7.27% of repeated responses (i.e., 88 out of 1210 repeated responses). Among them, during the elicitation of the standard outcome sequence, the choice reversal rate in Sub-Experiment A (7.58%) was similar to that in Sub-Experiment B (6.36%); during the elicitation of the standard probability sequence, the choice reversal rate in Sub-Experiment A (7.64%) was also similar to that in Sub-Experiment B (7.64%). These rates are lower than those reported in comparable studies [15]. Thus, it can be considered that the subjects’ responses in this study have high stability. Additionally, in terms of inferential statistics, we performed paired t-tests on repeated responses and computed Pearson correlations (r) between them, with analysis results shown in Table 1. The “t (54)” rows show no significant overall differences between repeated responses to the same questions. The “r” rows reveal strong correlations (0.75–0.93) between repeated responses for each question. Hence, choices on identical problems showed high test–retest consistency. The above two aspects of analysis consistently indicate that the experimental design of this study demonstrates good reliability in terms of subjects’ response consistency.

Table 1.

Reliability checks (first vs. second response).

5.2. Utility Function Comparison

As the experimental procedure, based on the series of prospect choices made by each subject in the two sub-experiments, a standard outcome sequence corresponding to Sub-Experiment A and a standard outcome sequence corresponding to Sub-Experiment B were obtained for each subject, denoted as and , respectively. Table 2 presents the mean values for each element in these sequences. Adopting the widely used power utility function [7,15], the least squares method was employed to fit the parameters for the standard outcome sequences elicited from each subject in each sub-experiment. Consequently, each subject yielded two values corresponding to the two sub-experiments, resulting in a set of 55 values corresponding to the 55 subjects within each sub-experiment.

Table 2.

Means of elements in standard outcome sequences.

Aggregately, the mean was 0.830 in Sub-Experiment A and 0.640 in Sub-Experiment B; an independent t-test confirmed the former significantly exceeds the latter (). Individually, 47 of 55 subjects showed higher in Sub-Experiment A than in Sub-Experiment B; a paired t-test revealed significant differences in values between the two sub-experiments ().

Analyses conducted at both the aggregate and individual levels consistently indicate that the outcome utility function elicited in Sub-Experiment B exhibits greater curvature than that elicited in Sub-Experiment A. This experimental finding is consistent with the hypothesis derived from prior empirical evidence [16,18], indicating that the results of this study are compatible with those of existing research. Taken together, these findings suggest that, compared with the conventional trade-off method, the RFTM is more effective in eliciting preferences.

5.3. Probability Weighting Function

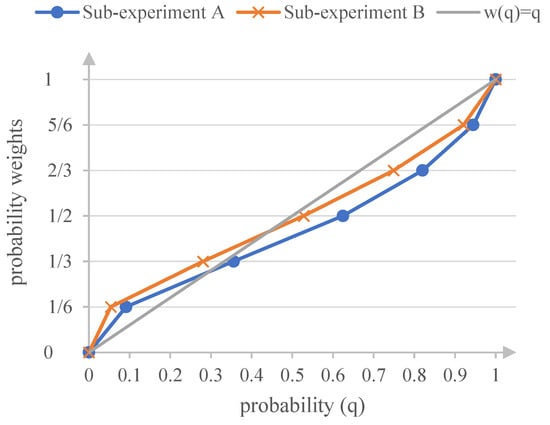

From the experimental procedure, it is known that for each subject in each sub-experiment, a standard probability sequence was elicited, where the probability weight . Figure 2 depicts the elicited probability weighting functions for both sub-experiments, based on the means of in each sub-experiment. Figure 2 shows that probability weighting is nonlinear in both sub-experiments, resembling the inverse S-shaped characteristic of RDU.

Figure 2.

Elicited probability weights in each sub-experiment.

To statistically assess whether the probability weighting functions elicited in the two sub-experiments exhibit linearity, the key criterion is whether the elicited probabilities are equal to the corresponding probability weights , that is, whether the condition holds. A statistically significant deviation between and indicates nonlinearity in the probability weighting function. Accordingly, all statistical tests were conducted separately within each probability weighting level. At each probability weighting level (), 55 observations of the probability were obtained, with each observation contributed by a distinct subject. Therefore, within each probability weighting level, the observations are mutually independent.

Prior to hypothesis testing, the Shapiro–Wilk test was conducted to assess the normality of the probability distributions at each probability weighting level. The results suggested that the normality assumption was violated for most probability weighting levels, with the majority of -values falling below 0.05. Given these findings, one-sample -tests, which rely on the assumption of normality, were not employed. Instead, nonparametric one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were consistently used to examine whether the median of the observed probabilities () at each weighting level differed from the corresponding probability weight . All tests were two-tailed, with the significance level set at 0.05. This analytical strategy ensures that the independence assumption underlying each statistical test is satisfied at each probability weighting level, thereby enhancing the validity and robustness of the inferential results. The detailed test results are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test results presented in Table 3 indicate that, in Sub-Experiment A, no significant difference was observed between and , whereas statistically significant differences emerged at all other probability weighting levels. Specifically, for smaller probabilities, , while for larger probabilities, . These results demonstrate that the probability weighting function elicited in Sub-Experiment A deviates significantly from the linearity assumption and exhibits an inverse S-shaped pattern, with the intersection between and the diagonal occurring at approximately .

A similar pattern was observed in Sub-Experiment B. Except for the probability weighting level corresponding to , where no significant difference between and was detected, statistically significant differences were found at all remaining levels. Again, for smaller probabilities and for larger probabilities. These findings indicate that the probability weighting function elicited in Sub-Experiment B also deviates significantly from linearity and displays an inverse S-shaped form, with the intersection point between and the diagonal located at approximately .

From a theoretical perspective, the probability weighting function derived by Prelec [26] based on the axiom of compound invariance implies an intersection point with the diagonal, which is fixed at . This theoretical prediction has been widely supported by empirical studies, with estimated intersection points typically falling within the range of 0.33 to 0.40 [27,28]. In comparison with these theoretical and empirical benchmarks, the intersection point of approximately 0.50 obtained in Sub-Experiment B—elicited using the conventional trade-off method—represents a substantial deviation from the established consensus. By contrast, the intersection point of approximately 0.33 obtained in Sub-Experiment A using the RFTM aligns closely with the theoretical prediction of and the commonly reported empirical range. From the perspective of construct validity, this result provides strong evidence that the RFTM achieves greater measurement accuracy in capturing the true shape of individuals’ probability weighting functions.

6. Discussion

To elicit preferences under the premise that probability weights depend on the choice-set outcome range (CSOR), this paper improves the conventional trade-off method and provides a method that can elicit individual preferences within a fixed choice-set outcome range, namely the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method (RFTM). RFTM mitigates not only the influence of probability weights on preference elicitation but also the influence of CSOR on elicited preferences. To verify the effectiveness of RFTM, an experiment was conducted. Results show that, compared to the utility function obtained based on the conventional trade-off method, the utility function obtained based on RFTM has smaller curvature. This is compatible with existing experimental observations. Additionally, even with a fixed CSOR, the elicited probability weighting function remains an inverse S-shape.

The above experimental results indicate that RFTM can elicit individual preferences more effectively compared to the conventional trade-off method. Existing experimental observations have already revealed the dependence of probability weights on CSOR. For instance, Fehr-Duda et al. [18] showed that, for gains, the weighting function (away from endpoints) shifts upward as outcomes decrease. As another example, Etchart-Vincent [16] reported, for losses, that as prospect outcomes increase (i.e., the absolute values of nonzero outcomes decrease), the probability weights corresponding to better outcomes increase accordingly. Collectively, these findings indicate that weights on better outcomes are markedly higher in narrower CSORs than in wider ones. Taking the context of gains as an example, if the probability weights corresponding to better outcomes rise with narrower CSORs, then in the process of eliciting the standard outcome sequence using the conventional trade-off method, as the CSOR widens progressively, the probability weight corresponding to the same probability declines. This will cause the utility differences between adjacent elements in the “standard outcome sequence” to progressively increase. Therefore, the utility function obtained based on the conventional method exhibits a stronger degree of risk aversion (greater concavity) relative to the true function. Conversely, RFTM maintains a constant CSOR throughout preference elicitation process, thereby better avoiding the impact of CSOR’s variability on preference elicitation, and eliciting more accurate utilities than the conventional trade-off method. Comparing the utility functions elicited based on the conventional trade-off method and RFTM reveals that the former has greater curvature than the latter. This experimental result is compatible with the aforementioned existing experimental observations, thereby verifying the effectiveness of RFTM.

Results further reveal that individuals subjectively distort probabilities even within a fixed CSOR. While Kontek and Lewandowski [12] and Baucells et al. [22] acknowledge preference dependence on CSOR, they attribute it solely to utility function variability across ranges and assume no probability distortion. Yet, our findings show inverse S-shaped weighting under both conventional trade-off method and RFTM, implying probability distortion persists even in fixed CSORs. Thus, the observed S-shaped certainty equivalents by Kontek & Lewandowski [12] and Baucells et al. [22] across ranges may stem from nonlinear probability weighting. These insights suggest that, even under the premise of considering the CSOR dependence characteristics of preferences, non-EUT theories still have promising development prospects in the future. Specifically, future advancements should incorporate probability weighting’s CSOR dependence into non-EUT frameworks.

This study is subject to several limitations. As discussed above, the proposed RFTM is applicable to a broad class of decision theories that rely on weighted utility maximization, including rank-dependent utility (RDU), cumulative prospect theory (CPT), and classical prospect theory. These frameworks typically assume that both the outcome utility function and the probability weighting function are invariant to the CSOR. The RFTM developed in this study primarily aims to address potential dependence of the probability weighting function on the CSOR. However, it does not explicitly account for the possibility that the outcome utility function itself may also vary with the CSOR. If the utility function depends on the CSOR, then from a measurement perspective, the fully nonparametric RFTM remains applicable but may involve relatively high decision costs. In such cases, the fully nonparametric RFTM approach could be extended to a semiparametric framework, allowing for a trade-off between decision costs and theoretical precision. A systematic examination of whether utility functions depend on the CSOR would require a dedicated experimental design and therefore lies beyond the scope of the present study.

These considerations point to several avenues for future research. First, building on a semiparametric version of the RFTM, future studies could systematically examine whether outcome utility functions and probability weighting functions depend on the outcome range of the choice set. If evidence suggests that both forms of dependence are present, it would be of interest to explore whether a coupling mechanism exists between them. Second, conditional on the existence of such dual dependence, the RFTM could be further refined to elicit preferences in a fully nonparametric manner while accounting for CSOR dependence in both components. Third, incorporating new empirical evidence, future research may revisit existing theoretical accounts of the mechanisms underlying preference range dependence, assessing their robustness and scope of applicability, and thereby contributing to the ongoing development of decision theory.

7. Conclusions

We refine the conventional trade-off method into the Range-Fixed Trade-off Method (RFTM), enabling preference elicitation under a fixed choice-set outcome range (CSOR). RFTM offers three key advantages. First, it maintains a constant CSOR throughout the preference elicitation, thereby mitigating CSOR’s impact on elicited preferences. Second, it can avoid the influence of probability weights on the preference elicitation, eliminating the need to presuppose the specific functional form of probability weighting function, thereby avoiding interference from the selected functional form on research conclusions. Third, it enables separate elicitation of utility and probability weighting functions within a fixed CSOR, which not only provides methodological assurance for investigating the influence of CSOR on preference but also provides feasibility for the future development of CSOR-dependent non-EUT theories.

This study is subject to certain limitations. In particular, allowing outcome utility functions to depend on the outcome range of the choice set may entail relatively high decision costs, in which case a semiparametric version of RFTM may be preferable. Future research may proceed in several directions: examining whether and how outcome-range dependence affects utility and probability weighting functions; refining RFTM to accommodate such dependence in both components, if present; and reassessing the generalizability of existing theories of preference range dependence in light of new empirical evidence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.L. and C.L.; Methodology, R.L.; Validation, R.L.; Formal analysis, R.L.; Data curation, R.L.; Writing—original draft, R.L.; Writing—review & editing, R.L. and C.L.; Supervision, C.L.; Project administration, C.L.; Funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72271108) and the Humanities and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 20YJA630028).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. As it involved only the collection of anonymous data without sensitive content or human experimentation, the Research Committee of the School of Business and Management at Jilin University granted an exemption for this study in accordance with Chinese Measures for Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Human Beings [29] (https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm (accessed on 20 January 2026)) (Exemption Approval Number: 20250827).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All materials, data, and code for all studies are made available in the project’s Open Science Framework page (https://osf.io/a85sk (accessed on 20 January 2026)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- von Neumann, J.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, H. The Utility of Wealth. J. Polit. Econ. 1952, 60, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, J.C.; Schoemaker, P.J.H. Probability versus Certainty Equivalence Methods in Utility Measurement: Are They Equivalent? Manag. Sci. 1985, 31, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakker, P.; Deneffe, D. Eliciting von Neumann–Morgenstern Utilities When Probabilities Are Distorted or Unknown. Manag. Sci. 1996, 42, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allais, M. Le comportement de l’homme rationnel devant le risque: Critique des postulats et axiomes de l’école américaine. Econometrica 1953, 21, 503–546. [Google Scholar]

- Quiggin, J. A Theory of Anticipated Utility. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1982, 3, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Advances in Prospect Theory: Cumulative Representation of Uncertainty. J. Risk Uncertain. 1992, 5, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blavatskyy, P. A Simple Nonparametric Method for Eliciting Prospect Theory’s Value Function and Measuring Loss Aversion under Risk and Ambiguity. Theory Decis. 2021, 91, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, U.; Starmer, C.; Sugden, R. Third-Generation Prospect Theory. J. Risk Uncertain. 2008, 36, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchouicha, R.; Vieider, F.M. Accommodating Stake Effects under Prospect Theory. J. Risk Uncertain. 2017, 55, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreia-Vioglio, S.; Dillenberger, D.; Ortoleva, P. Cautious Expected Utility and the Certainty Effect. Econometrica 2015, 83, 693–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontek, K.; Lewandowski, M. Range-Dependent Utility. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 2812–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Day, R. Target-Adjusted Utility Functions and Expected-Utility Paradoxes. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Tymula, A.; Wang, X.; Imaizumi, Y.; Kawai, T.; Kunimatsu, J.; Matsumoto, M.; Yamada, H. Dynamic Prospect Theory: Two Core Decision Theories Coexist in the Gambling Behavior of Monkeys and Humans. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdellaoui, M. Parameter-Free Elicitation of Utility and Probability Weighting Functions. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 1497–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchart-Vincent, N. Is Probability Weighting Sensitive to the Magnitude of Consequences? An Experimental Investigation on Losses. J. Risk Uncertain. 2004, 28, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Markle, A.B. An Empirical Test of Gain–Loss Separability in Prospect Theory. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1322–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr-Duda, H.; Bruhin, A.; Epper, T.; Schubert, R. Rationality on the Rise: Why Relative Risk Aversion Increases with Stake Size. J. Risk Uncertain. 2010, 40, 147–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Ding, W.; Zhang, S.; Xu, H. Large Group Decision-Making with a Rough Integrated Asymmetric Cloud Model under Multi-Granularity Linguistic Environment. Inf. Sci. 2024, 678, 120994. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S. Classification and Identification of Medical Insurance Fraud: A Case-Based Reasoning Approach. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2025, 31, 1345–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baucells, M.; Lewandowski, M.; Kontek, K. A Contextual Range-Dependent Model for Choice under Risk. J. Math. Psychol. 2024, 118, 102821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischbacher, U. z-Tree: Zurich Toolbox for Ready-Made Economic Experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostic, R.; Herrnstein, R.J.; Luce, R.D. The Effect on the Preference-Reversal Phenomenon of Using Choice Indifferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1990, 13, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelec, D. The Probability Weighting Function. Econometrica 1998, 66, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.; Wu, G. On the Shape of the Probability Weighting Function. Cogn. Psychol. 1999, 38, 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakker, P.P. Prospect Theory: For Risk and Ambiguity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China; Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China; Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China; National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Measures for Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Human Beings; The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China (gov.cn): Beijing, China, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm (accessed on 20 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.