Abstract

In response to the evolving dynamics of global supply chains, business-to-business (B2B) sharing economy models within the logistics industry have gained importance for innovation and sustainability over the last few years. According to a literature review, the sharing economy has become a pivotal innovation in the business environment, especially for resource utilisation efficiency and the potential to advance sustainable development policies. Despite the known positive impact on the economy and environment, integrating sharing economy models into logistics and supply chains remains limited. This highlights a key research area that requires a thorough examination of the barriers and opportunities for business-to-business (B2B) sharing economy platforms in logistics and supply chains that reflect environmental policy goals and promote cleaner, more efficient logistics systems. This paper outlines the significance of B2B sharing economy platforms as a crucial part of smart and resource-efficient supply chains. Using a system theory approach, B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics and SC were identified and systematically and comprehensively analysed across four critical aspects: sharing storage, sharing parking space, shared labour, and collaborative transportation. The scope of the research is limited to the smart and sustainable dimensions of logistics and supply chains, with a particular focus on the analysis of B2B sharing economy platforms. The novelty of this study lies in its empirical and theory-informed analysis of B2B sharing platforms as a key driver for smart and resource-efficient logistics. While prior studies have largely focused on consumer-facing sharing models or conceptual frameworks, this paper systematically evaluates operational B2B platforms. The analysis reveals that while B2B platforms offer valuable solutions in collaborative transport, storage, labour, and parking, they are underutilised and insufficiently aligned with environmental and digital objectives. The study introduces a spider chart analysis grounded in system theory to evaluate platforms against six dimensions, uncovering trade-offs between flexibility and sustainability. These insights contribute to understanding the strategic positioning of such platforms and propose a direction for smarter, resource-efficient supply chains.

1. Introduction

The global imperative to protect the environment is increasingly recognised as fundamental to ensuring economic and social development that supports future generations and enables the transition to cleaner, more sustainable logistics practices [1]. Sustainable development is crucial for the future of humanity, as it significantly impacts business operations and supply chains (SC) [2]. As Ji and coauthors [3] argue, integrating sustainability into company operations is a critical precondition for international competitiveness in smart logistics, which is increasingly defined by optimised resource usage, environmental efficiency, and digital innovation. Smart logistics refers to the integration of digital technologies, data-driven optimisation, and automation across supply chain functions to improve responsiveness and efficiency [4,5,6].

In this context, the sharing economy has emerged as a key factor for sustainability. The sharing economy, an element of the circular economy, is a socio-economic model that promotes sharing rather than ownership. In this way, individuals, companies, and other relevant stakeholders can use goods and services more efficiently through technology-enabled platforms. The model promotes resource optimisation and waste prevention, reduces environmental impact, and supports social cohesion and business model innovation. These features are particularly important in the European context, where the supply chain’s resilience is threatened by limited raw materials and long-term goals to achieve a sustainable, carbon-neutral economy [7]. Optimising resource use and extending asset life cycles are therefore strategic imperatives to support cleaner production and sustainable consumption [8,9].

The rise of the sharing economy has transformed several industries with its innovative approach, helping to overcome long-standing inefficiencies. The potential impact is particularly significant in the logistics sector, which is expected to account for up to 40% of global greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 [10]. This sector is a huge consumer of materials and energy, a dominant user of single-use packaging and a key contributor to waste and emissions. However, logistics remains largely conventional and has been slow to adopt circular economy strategies, especially those based on the sharing economy. This is why B2B sharing economy logistics and SC platforms represent a promising trend. They offer new ways to organise supply chains based on sustainability and efficiency principles, providing companies with flexible access to assets such as storage space, transport, labour, and parking infrastructure, among others. As environmental pressures and market demands intensify, incorporating these models becomes a strategic innovation and necessity [11,12].

While sharing economy applications have flourished primarily in business-to-consumer (B2C) domains, such as ride-hailing services or parcel lockers, the integration of sharing economy models into logistics and supply chain management remains limited. This discrepancy reveals a significant gap between the recognised theoretical potential of sharing-based models and their practical implementation in logistics systems. Previous research has predominantly focused on B2C sharing economy platforms, emphasising consumer behaviour, trust mechanisms, and urban mobility innovations, whereas the strategic role of B2B sharing platforms in logistics and supply chains has received considerably less attention [13].

Although the sharing economy has been widely examined, the dominant body of research remains centred on B2C models, particularly in areas such as urban mobility, accommodation, and consumer services. These studies mainly address issues related to individual users, including trust, platform governance, and usage behaviour. However, the application of sharing economy principles in B2B logistics and supply chains represents a fundamentally different phenomenon. B2B sharing platforms operate within inter-organisational networks, involving strategic resource sharing, long-term contractual relationships, and systemic interdependencies among multiple supply chain actors. Consequently, insights derived from B2C-oriented studies cannot be directly transferred to B2B logistics contexts.

Despite their growing practical relevance, empirical and systematic analyses of operational B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics and supply chains remain scarce [13]. Existing studies are largely conceptual and fragmented [14], embedded within broader discussions of digitalisation or the circular economy, and do not provide structured, comparative evaluations of active platforms. In particular, there is a lack of studies that simultaneously assess the smart and sustainability-oriented characteristics of B2B sharing platforms from a systems perspective.

This study addresses this research gap by systematically mapping and evaluating active B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics and supply chains through a framework grounded in system theory. The study is based on the hypothesis that B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics remain underutilised despite their potential to support smart and sustainable supply chains. To examine this hypothesis, platforms are identified and analysed across four core functional domains: sharing storage, sharing parking space, shared labour, and collaborative transportation. A system theory approach enables a structured and holistic analysis of platform functionalities, interdependencies, and their integration within broader logistics and supply chain ecosystems. Using a spider chart-based assessment across six strategic dimensions, the study reveals mismatches between digital innovation and sustainability orientation. The contribution of this paper lies in applying a requisitely holistic system theory perspective to a fragmented research domain, thereby offering an integrative analytical tool for understanding the structural barriers and underutilised potential of B2B sharing economy platforms in advancing smart and sustainable logistics and supply chains. Accordingly, the study addresses the following research question: to what extent do current logistics-related B2B sharing platforms incorporate smart and sustainable features?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sharing Economy in Logistics and Supply Chain

Recent studies (e.g., Chung [4], Shee and coauthors [5], Verbivska and coauthors [6]) highlight the growing importance of digitalisation in logistics for achieving sustainability objectives. However, the integration of B2B sharing platforms into these developments remains limited. Furthermore, sustainability is often treated as a secondary outcome rather than a core design principle. This paper responds to calls for more critical, structured evaluation of platform maturity and systemic contributions.

In response to the evolving dynamics of global supply chains, the intersection of B2B sharing economy models with the logistics industry offers opportunities for innovation, sustainability, and cleaner production. As environmental policies increasingly emphasise resource efficiency and emissions reduction, adopting sharing economy principles enables a strategic shift toward digital, decentralised, and resource-optimised platforms. These models optimise warehouse usage, reduce transportation costs, and address pressing issues such as labour shortages and environmental pressures. They align with broader environmental and climate policy goals and specifically advocate for advancing smart, sustainable logistics.

The sharing economy, a subset of the circular economy, is a socio-economic system that facilitates access to underutilised resources through digital platforms [15]. Starting in B2C markets, its principles permeate B2B contexts, especially logistics, where sharing platforms help reallocate logistics resources between companies [16]. This evolution has significant implications for promoting waste reduction, resource longevity, and business model innovation [8,9]. With Europe facing limited raw material reserves, optimising resource use is a sustainability imperative and a strategic priority for industrial resilience [7].

Digitisation has played a transformative role in enabling these models, particularly in manufacturing, where digital tools allow capacity matching and collaboration between partners [17,18]. This development is consistent with the circular economy principles and represents a broader shift in the logic of procurement and services across all industrial sectors. In logistics, the sharing economy has redefined relationships and resource flows by enabling agile, adaptive models that deliver adaptable, sustainable solutions [19]. Belk distinguishes between true sharing and pseudo-sharing, offering a conceptual lens to assess how B2B platforms operate within market-driven logic [20]. This provides a useful theoretical grounding for examining logistics-related applications.

However, the B2B sharing economy faces unique implementation challenges, including liability risks, cybersecurity threats, and a lack of formal regulatory frameworks [21,22]. Despite its projected market value of about EUR 1.39 trillion by 2024 [22], actual adoption within logistics remains limited. This gap between theoretical potential and practical utilisation underscores the urgency for empirical investigations needed for future utilisation and commercialisation

In a B2B alliance, collaboration is driven by strategic motivations, including reducing transaction costs and co-creating value [23], yet the long-term success of these platforms often hinges on the central actor’s ability to manage value flows and coordination [24]. Sposato, with coauthors, further highlights the transformative potential of these models beyond logistics, suggesting their integration into social and spatial innovation frameworks [25].

2.2. Smart Logistics and Digital Integration

Smart logistics and the sharing economy are closely intertwined, enabling more efficient, flexible, and environmentally sustainable operations. Sharing-based logistics models have been extensively studied for their potential to reduce transaction costs, promote resource pooling, and optimise asset use across transportation and warehousing systems [26,27,28]. Digital platforms enable seamless exchanges and mobility solutions that reduce waste and enhance collaboration [29,30,31].

Logistics networks become increasingly urban and complex. Adopting B2B sharing platforms, such as those facilitating shared storage or collaborative transportation, helps reduce congestion and emissions, supporting the goals of smart and sustainable cities [32]. This alignment calls for regulatory frameworks that reflect the operational logic of sharing economy models and prioritise environmental sustainability [33].

Digitalisation remains a core enabler in this ecosystem. Smart logistics platforms leverage digital tools for real-time tracking, predictive analytics, and dynamic resource matching, collectively improving operational agility and environmental performance [34,35]. These features also align well with circular economy goals and cleaner production principles.

In practical terms, the sharing economy supports smart logistics through shared transport services, collaborative warehousing, and efficient use of parking or loading infrastructure—solutions that alleviate urban challenges and lower costs [36,37,38]. Using platform-based data also facilitates environmental impact assessments and strategic decision-making, thereby enhancing overall supply chain sustainability [39].

Furthermore, integrating sharing economy principles within smart cities highlights the role of technology and data in optimising logistics processes and improving urban livability [40,41]. Shared mobility and resource pooling are also essential to reducing emissions and congestion, aligning closely with sustainability targets [42]. Ultimately, the sharing economy and smart logistics share goals of resource efficiency, technological advancement, and environmental responsibility. Their synergistic potential is particularly valuable in dense urban areas where digital coordination and sustainable logistics strategies are urgently needed.

2.3. Sustainability as a Key Concept of the Sharing Economy Model

Sustainability is a key principle of the sharing economy, contributing to cleaner logistics through resource circularity, emission reduction, and social value creation. Martin [43] notes that while the sharing economy can promote sustainable consumption, it must be accompanied by structural shifts in business models and regulations to avoid reinforcing unsustainable patterns. Studies by Curtis and Lehner [43], Boar and coauthors [44], and Chuah and coauthors [45] affirm that the sharing economy has positive environmental, social, and economic impacts, but also point to the need for institutional tools to sustain this focus [46,47].

Smart logistics, particularly last-mile delivery, poses major sustainability challenges, including emissions, land use, and congestion [48,49]. Here, sharing platforms for urban logistics, such as shared lockers or collaborative deliveries, offer innovative solutions for balancing demand and environmental concerns [5,50]. The sharing economy’s promotion of use over ownership also supports transitions to more circular, possession-light urban economies [47].

However, current research on the long-term sustainability performance of B2B sharing platforms remains limited. Most empirical studies focus on B2C applications, leaving a gap in evaluating the effectiveness of B2B platforms in reducing emissions, improving cost-efficiency, or enhancing stakeholder value.

2.4. B2B Sharing Platforms’ Potential for Logistics and Supply Chains

Integrating B2B sharing economy models into logistics and supply chains enables the combination of economic, environmental and technological innovations. These models are consistent with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [51], particularly in decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation.

B2B platforms encourage the sharing of warehouses, transportation assets, and labour, enabling flexible scaling and the use of redundant infrastructure. Similarly, Tetřevová and Kolmašová [52] emphasise that B2B models contribute to sustainable infrastructure by promoting efficient use of resources and reducing the need for new physical assets. As Acquire and coauthors [53] discuss, sharing economy platforms introduce new forms of governance that coordinate actors through digital interfaces and algorithms. Digital convergence is important in reducing emissions and increasing efficiency [29,30,31]. In the B2B logistics context, such models enable real-time resource allocation and strategic decision-making, which are increasingly vital for achieving adaptive logistics systems.

Mont and coauthors [54] highlight that research on the sharing economy has remained largely conceptual, with insufficient empirical validation, especially in the context of B2B in logistics and SC. This limitation is particularly relevant in a pandemic, when SC dynamics seek more informed insights into platform practice and operation. Although the literature generally supports the theoretical potential of B2B sharing platforms for developing cleaner, more resilient logistics systems, there remains a lack of empirical studies that examine platform typologies, strategic orientations, and their alignment with sustainability goals. This study addresses this gap by systematically reviewing existing B2B sharing platforms and assessing their contribution to smart and sustainable logistics, providing conceptual clarity and the necessary empirical evidence.

2.5. Summary of the Literature and Identification of the Research Gap

The existing body of literature on the sharing economy in logistics and supply chains is heterogeneous in terms of focus, methodology, and analytical depth. Table 1 provides a comparative overview of selected key studies, highlighting their primary contributions and the limitations that motivate the present research.

Table 1.

Overview of key studies on the sharing economy in logistics and supply chains.

The summary of prior research highlights a clear research gap. While the sharing economy has been extensively examined in B2C contexts and conceptually discussed in relation to logistics and sustainability, empirical and systems-oriented studies that comparatively analyse operational B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics and supply chains remain scarce. Existing studies are predominantly conceptual, focus on consumer-facing platforms, or examine adoption factors without analysing platform characteristics in a structured and comparative manner. This study directly addresses this gap by providing a system theory-based evaluation of active B2B sharing platforms, integrating smart and sustainability dimensions within a holistic analytical framework.

3. Methodology

The methodology of this study is grounded in a requisite holistic system theory approach, as defined by Mulej [55] and Zenko and Mulej [56], which is particularly suitable for analysing complex and interdependent elements within logistics and supply chains. This perspective supports the examination of B2B sharing economy platforms not as isolated entities, but as interconnected components embedded within broader logistics and supply chain ecosystems.

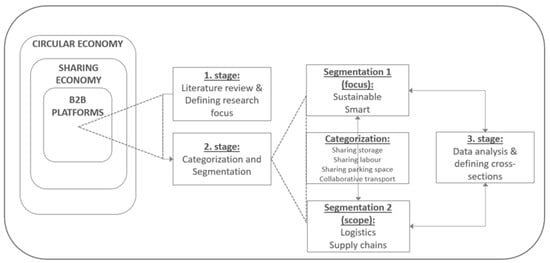

Based on this theoretical foundation, an analytical framework was developed to assess the smart and sustainability-oriented features of B2B sharing economy platforms (Figure 1). The framework provides a structured and systematic approach for identifying, categorising, and evaluating platforms, enabling insights into their current positioning and revealing patterns of underutilisation. The detailed methodological steps, including platform selection, categorisation, and analytical procedures, are presented in the following subsections.

Figure 1.

Framework for assessing the sustainability and smart features of B2B sharing economy platforms.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the methodological approach follows a structured, multi-stage logic grounded in system theory. The framework guides the identification, categorisation, segmentation, and comparative evaluation of B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics and supply chains. The individual methodological steps are described in detail in the following subsections.

3.1. Identification and Selection of B2B Sharing Economy Platforms

The identification of B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics and supply chains was conducted through a structured web-based search. The search process aimed to capture a diverse yet analytically meaningful set of operational platforms rather than to establish an exhaustive population, given the dynamic and rapidly evolving nature of digital logistics markets.

Keywords such as “B2B sharing logistics platform”, “shared warehousing platform”, “collaborative freight platform”, “logistics sharing marketplace” and related combinations were used. The search was performed using publicly accessible sources, including platform websites, specialised logistics portals, and industry reports.

To ensure relevance and comparability, platforms were included based on the following criteria:

- Active operation during 2024;

- Explicit business-to-business (B2B) orientation;

- Relevance to logistics or supply chain functions;

- Availability of sufficient publicly accessible information for analysis.

Platforms that focused exclusively on consumer-facing services (B2C) or lacked transparent information on their operational scope were excluded.

The final sample comprises 23 B2B sharing economy platforms, a purposeful and illustrative selection rather than a statistically representative dataset. This approach is consistent with exploratory and systems-oriented research designs, where analytical depth and functional diversity are prioritised over population completeness. Through extensive review of platforms, it was found that many B2B platforms are promoted as sharing economy platforms but generally do not offer these kinds of features; therefore, the sample of the research is narrow and focused, which is consistent with the findings of Belk [20].

3.2. Categorisation of Platforms into Functional Domains

Following identification, platforms were categorised into four core functional domains—sharing storage, sharing parking space, shared labour, and collaborative transportation—which are partly derived from Rathanyake and coauthors’ [57] classification of shareable resources.

This categorisation was derived through a thematic synthesis of prior literature on sharing economy applications in logistics and supply chains (e.g., Antikainen et al.; Carissimi & Creazza; Van Duin et al.) and reflects the most frequently identified resource-sharing functions within logistics systems.

Although some platforms offer multiple services, each platform was assigned to the category representing its primary functional focus, as communicated on its official website and core service description. This analytical simplification was necessary to enable systematic comparison while remaining consistent with a system theory perspective, which emphasises dominant functions within complex systems.

3.3. Scope Distinction: Logistics Versus Supply Chain

To address the distinction between logistics-focused and supply chain-oriented platforms, platforms were additionally assessed based on the scope of their offered solutions. Platforms were classified as

- logistics-focused when their services primarily addressed operational activities such as transport, warehousing, labour, or parking;

- supply chain-oriented when their solutions extended beyond logistics operations to include coordination, visibility, or integration across multiple supply chain stages.

This distinction enabled clearer interpretation of the empirical findings and supported analysis of the limited integration of sharing economy platforms into broader supply chain structures.

3.4. Analytical Framework and Evaluation Dimensions

The analysis was guided by a requisite holistic system theory approach [55,56], which is particularly suitable for examining complex, interdependent socio-technical systems such as logistics platforms. Rather than analysing isolated features, this approach supports the examination of platforms as interconnected system elements embedded within broader logistics and supply chain ecosystems.

Based on qualitative platform descriptions and conceptual alignment with system theory principles, six evaluation dimensions were inductively derived:

- Diverse solutions for efficiency and optimisation;

- Technological innovation and digital integration;

- Flexibility and scalability;

- Sustainability and smart logistics emphasis;

- Addressing specific industry challenges;

- Marketplace model predominance.

These dimensions reflect key systemic attributes, including efficiency, adaptability, sustainability orientation, technological capacity, and coordination mechanisms.

3.5. Spider Chart Analysis

A spider chart-based assessment was used to support a comparative, holistic evaluation of platform characteristics. Consistent with system theory principles, this method enables the visual synthesis of multidimensional qualitative attributes and facilitates the identification of patterns, trade-offs, and imbalances across platform types.

Qualitative characteristics were translated into numerical scores on a 0–4 scale, reflecting the extent to which each platform demonstrated each dimension. Equal weighting was applied across all dimensions to avoid normative prioritisation and to preserve the exploratory nature of the analysis.

The spider chart does not aim to produce statistically generalisable results but rather to reveal structural patterns and relational trade-offs between digital innovation, sustainability orientation, and functional scope.

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Identified B2B Platforms

A comprehensive analysis of B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics and supply chains (SC) was conducted, identifying 23 platforms, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics and SC.

The limited number of identified platforms indicates that, despite strong theoretical support for sharing-based logistics models, B2B sharing economy platforms remain weakly institutionalised within logistics systems. From a system theory perspective, this suggests that resource-sharing mechanisms have not yet achieved systemic integration across logistics and supply chain structures.

4.2. Platform Distribution by Functional Domain

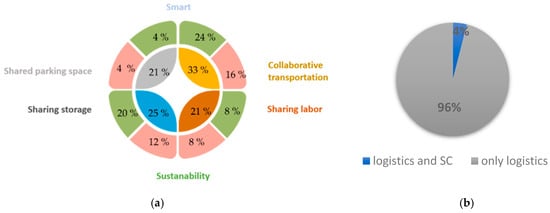

Regarding the categorisation of four pivotal aspects (Figure 2a), the largest number of identified platforms covered collaborative transport (33%), followed by sharing storage (25%) and both shared labour and shared parking space (each at 21%).

Figure 2.

Share of platforms regarding type and focus (a) and scope of platforms (b).

The dominance of collaborative transportation platforms reflects the relative maturity of transport-related digital coordination mechanisms compared to other logistics resources. From a system theory perspective, this indicates that transport functions act as dominant subsystems within current B2B sharing configurations, while other resources, such as labour and parking, remain peripheral and weakly integrated.

4.3. Platform Scope: Logistics vs. Supply Chains (Figure 2b)

Regarding scope and strategic orientation (platforms were grouped based on whether they offered solutions focused solely on logistics or encompassed the entire supply chain), 96% of the platforms prioritised logistics. In contrast, only one platform offered broader SC functionalities (Figure 2b).

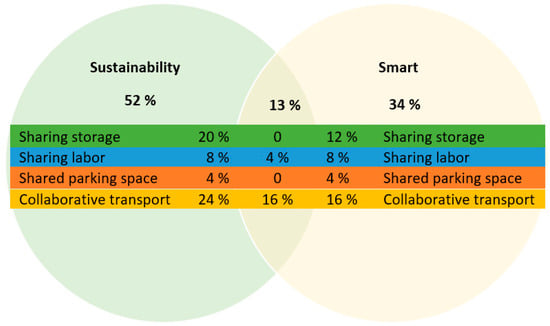

In addition, platforms were analysed based on their strategic orientation using website communication indicators. A Venn diagram was constructed to assess overlaps and distinctions in strategic emphasis by grouping keywords into sustainability and smart logistics themes. As illustrated in Figure 3, the share of platforms that use terms related to sustainability on their websites (such as sustainability, environment, circular economy, carbon footprint, and similar) is 52%. Significantly fewer, 34% of these platforms highlight the smart concept (smart, smart solutions, smart cities and similar). Only 13% of platforms use both terms (sustainability and smart) or other related terms on their websites.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram defining cross-sections of sustainability and smart terms in different types of platforms.

The overwhelming focus on logistics rather than broader supply chain integration highlights a structural fragmentation within B2B sharing economy platforms. In system theory terms, platforms predominantly operate at the operational subsystem level, with limited connectivity to higher-level supply chain coordination and governance structures.

4.4. Sustainability and Smart Orientation

Beyond structural fragmentation in platform scope, an additional imbalance arises at the strategic orientation level.

The limited overlap between sustainability and smart orientation suggests a misalignment between digital innovation and environmental objectives. From a system theory perspective, this reflects a lack of functional coupling between technological subsystems and sustainability-driven system goals, resulting in partial rather than holistic system optimisation.

From a system theory perspective, this weak coupling between smart and sustainability orientations indicates that platform development is driven by isolated optimisation goals rather than by an overarching system purpose.

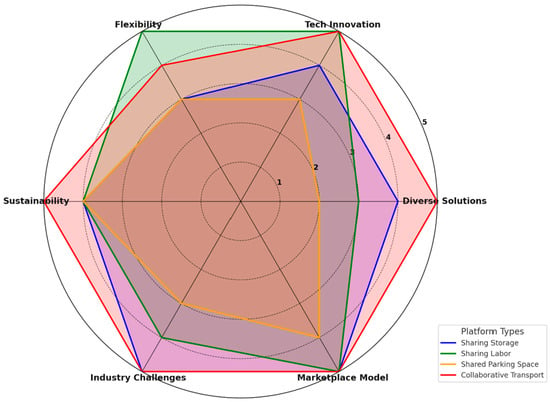

To grasp the comprehensive nature of the platforms, understand their balanced or unbalanced distribution of characteristics, and appreciate the diverse areas where they excel or may need improvement, a spider chart analysis of the B2B sharing economy platforms was conducted (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Spider chart of B2B sharing economy platform analysis.

4.5. Results of the Spider Chart Analysis

The spider chart analysis reveals pronounced asymmetries across evaluation dimensions. Platform types that score highly in digital innovation and efficiency often exhibit a weaker sustainability orientation, suggesting trade-offs rather than synergies among system functions. The absence of balanced performance across all six dimensions indicates that B2B sharing economy platforms currently function as isolated optimisation mechanisms rather than as integrated system components.

The spider chart scores (explained in more detail in the methodology) reveal meaningful differences across platform types (see Figure 4 and Table 3). Collaborative transport platforms scored highest in digital innovation (3.75) and diverse solutions (3.50), reflecting their technological maturity and service offerings. Sharing labour platforms showed the strongest flexibility and scalability (3.75), but had the lowest scores in sustainability (2.00) and technological innovation (2.00), indicating their operational adaptability but limited ecological and digital orientation. Parking sharing platforms scored highest in sustainability (3.25), suggesting alignment with urban and environmental priorities, but scored lower in addressing specific industry challenges (2.00). Storage sharing platforms displayed balanced scores across most dimensions but lacked emphasis in digital innovation (2.50). These differences indicate distinct patterns of emphasis across platform types, reflecting uneven development across the evaluated dimensions.

Table 3.

Spider chart results.

The pattern of scores not only revealed each platform type’s relative strengths and weaknesses but also underscored the limited systemic integration across dimensions. While some platforms excelled in digital innovation or sustainability, few demonstrated balanced performance across all six dimensions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings in Relation to Existing Literature

The results of this study provide empirical support for earlier conceptual research highlighting the potential of sharing economy models to enhance efficiency and sustainability in logistics and supply chains [15,19,20], as well as through collaborative resource use and sustainable business practices [13]. While prior studies have extensively discussed the theoretical benefits of B2B sharing platforms, empirical evidence examining operational platforms has remained limited [16] and fragmented [19]. It was found that many B2B platforms are promoted as sharing economy platforms, but generally do not offer these features; therefore, the research sample is narrow and focused. This is consistent with Belk’s [20] research. The findings of this study demonstrate that, despite increasing digitalisation in logistics, B2B sharing economy platforms remain relatively scarce and unevenly distributed across functional domains, similar to the findings of Ivanković and Maehle [13], who investigated B2B underdevelopment due to power asymmetry among beneficiaries. Better development of transportation sharing platforms in the B2C segment [14] emphasises consumer behaviour, trust mechanisms, and urban mobility innovations. Even though B2C is not directly transferable to B2B, lessons learned (e.g., user perspective, trust, governance, user behaviour) can be useful for logistics and supply-chain managers entering B2B sharing platforms, as shown in the investigated Market Model Predominance (Figure 4 and Table 3).

The predominance of collaborative transportation platforms compared to other resource-sharing domains confirms earlier observations that transport-related activities are more amenable to digital coordination and market-based sharing mechanisms [56]. In contrast, the limited presence of platforms supporting shared labour, parking infrastructure, or storage capacity indicates that other logistics resources remain weakly integrated into sharing-based models [13]. These extend prior conceptual work by empirically illustrating that sharing economy adoption in logistics remains functionally selective [15] rather than systemically comprehensive [19].

Furthermore, the overwhelming focus of identified platforms on logistics operations rather than broader supply chain integration aligns with the existing literature, which suggests that sharing initiatives primarily address operational inefficiencies rather than structural supply chain coordination [16,17]. While sharing economy concepts are increasingly discussed in supply chain research, the results indicate that their practical application remains largely confined to isolated logistics subsystems. Prior conceptual research on B2B sharing economy models in logistics and supply chains [16] also highlighted the limited empirical validation [19] and fragmented integration of such platforms in operational settings [52].

5.2. System Theory Interpretation of Observed Patterns

From a system theory perspective [55,56], the observed patterns indicate that B2B sharing economy platforms currently function as partially integrated subsystems rather than as fully embedded components of logistics and supply chain systems. The dominance of logistics-focused platforms reflects a configuration in which optimisation efforts are concentrated at the operational level, while higher-level coordination and governance mechanisms remain underdeveloped. Such fragmentation is consistent with system theory insights, which emphasise that isolated subsystem optimisation rarely leads to holistic system performance [56].

While many platforms demonstrate strong digital and technological capabilities, sustainability-related features are often weakly articulated or insufficiently integrated into platform value propositions. Similar tensions between technological innovation and sustainability goals have been conceptually noted in prior sharing economy research [20], but the present study provides empirical evidence of this misalignment in B2B logistics platforms. A theory-based framework identified by Benoit and coauthors [81] might successfully aggregate supply and demand and provide powerful market positions, much as companies such as Uber and Airbnb have dominated the P2P sharing economy.

The spider chart analysis highlights pronounced asymmetries across evaluation dimensions, revealing trade-offs rather than synergies between digital innovation, flexibility, and sustainability orientation. In system theory terms, this pattern reflects sub-optimisation, where improvements within individual subsystems do not translate into overall system effectiveness [56]. As a result, B2B sharing economy platforms currently deliver incremental efficiency gains rather than transformative system-level change in logistics and supply chains.

Fragmentation was also identified within the legislative framework and regulations, as they differ significantly across regions and countries. Some regions and companies are more influential than others; therefore, regulatory challenges and power imbalances may prevent businesses from fully delivering their value proposition within B2B platforms. The B2B role is therefore crucial in mitigating ecosystem risks and challenges while orchestrating key activities, e.g., relationship management, contracting/and matchmaking [13].

5.3. Implications for Smart and Sustainable Logistics

In addition to the theoretical contributions, this study offers intriguing implications for supply chain and logistics managers. First, the study offers a framework for managers to consider when implementing and promoting the co-creation of value through collaborative resource use, as the transformative potential of B2B sharing economy platforms for smart and sustainable logistics remains largely underutilised. Although digital platforms enable greater flexibility, responsiveness, and resource efficiency, their limited integration with sustainability objectives and broader supply chain coordination constrains their systemic impact. This observation is consistent with studies that identify governance, coordination, and incentive alignment as key barriers to the wider adoption of sharing-based models [19] in logistics [20]. Knowledge of variables that facilitate co-creation, as presented in Figure 4, can enable managers to develop and adapt a strategy that fosters co-creation among supply-chain actors. An awareness of potential value co-creation can help them optimise its benefits and mitigate potential risks, as also described by Vasil and coauthors [14].

For logistics and supply chain actors, such fragmentation may hinder the realisation of synergistic benefits associated with shared resource utilisation, coordinated planning, and reduced environmental impact. Therefore, B2B may enable managers to increase strategic resource sharing among multiple supply-chain actors and expand organisational networks [82]. Without stronger coupling between logistics subsystems and supply chain-level coordination mechanisms, sharing economy platforms risk reinforcing existing structural silos rather than enabling holistic system optimisation [16,83].

Digitalisation and the informatisation of data for real-time data sharing can be improved with standardised solutions within B2B platforms. These platforms, addressing storage, labour, transport and parking, also allow different access levels for different employees, as well as general (e.g., parking) or limited (e.g., labour) use, enabling greater efficiency in data management and increasing productivity.

5.4. Research Contribution and Novelty

This study contributes to the literature in several important ways. First, it provides one of the few empirical and comparative analyses of operational B2B sharing economy platforms in logistics and supply chains, addressing a research gap previously dominated by conceptual and B2C-oriented studies [1,15]. Second, applying a requisite holistic system-theory approach enables evaluating platforms as interconnected socio-technical system components rather than isolated digital solutions, extending earlier conceptual frameworks [55,56].

Third, by integrating smart and sustainability dimensions within a single analytical framework, the study offers a novel lens for assessing alignment between technological innovation and sustainability objectives in B2B sharing platforms. The findings reveal that, despite their theoretical promise, current platforms remain underutilised as drivers of systemic transformation in logistics and supply chains. By empirically documenting these structural imbalances, this study advances the understanding of B2B sharing economy platforms and provides a foundation for future research on their deeper systemic integration and long-term sustainability impacts.

6. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the transformative potential of B2B sharing economy platforms in enhancing logistics and supply chains (SC) through improved efficiency, sustainability, and innovation. Using a system theory lens, the analysis revealed how such platforms contribute to smarter logistics ecosystems by facilitating the shared use of resources, reducing inefficiencies, and supporting sustainability-driven practices.

The findings confirm the potential for expanding B2B platforms in the logistics and supply chain sectors. Their implementation must be strategic enough and supported by industry stakeholders and policymakers to unlock their full potential. The platforms must also be well aligned with key environmental policies and follow the goals of the green transition and urban sustainability agendas.

Moreover, applying Mulej’s system theory [55,56] provided a coherent analytical framework for a deeper understanding of the platforms’ complexity in the context of operational, digital, smart, and sustainable features. This approach proved particularly valuable in identifying systemic gaps, such as the disconnect between digital innovation and environmental alignment, and offers a replicable framework for future analysis.

The study identifies a critical opportunity: closing the gap between the potential of B2B sharing platforms and adoption. Achieving this will require coordinated action, including raising stakeholder awareness, fostering enabling regulatory environments, and incentivising collaborative innovation across the logistics sector.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations. The categorisation and assessment of platform characteristics were based on publicly available data from the web, which may not be comprehensive enough to provide insight into internal strategies or real-world operations. Therefore, some subjectivity in interpretation is inevitable. Although coding followed platform descriptions (see Table 2), the absence of primary data limits validation.

Future research could enhance this framework by incorporating longitudinal or regional analyses to track platform evolution over time or in different geographic contexts. In addition, a deeper investigation into platform governance models, user adoption dynamics, and integration within smart city infrastructures would enrich understanding. Applying advanced modelling techniques, such as network analysis or scenario simulations, could further illuminate the interdependencies and systemic roles of B2B platforms, address bargaining power disparities, ensure fairness, reliability, and transparency, and promote more efficient data sharing and mass personalisation, thereby bringing breakthroughs in B2B platform development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R., B.R. and M.O.; methodology, M.R., B.R. and M.O.; formal analysis, M.R., B.R. and M.O.; investigation, M.R., B.R. and M.O.; data curation, M.R., B.R. and M.O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R., B.R. and M.O.; writing—review and editing, M.R. and M.O.; visualization, M.R. and M.O.; supervision, M.R., B.R. and M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Authors received funding from the European Union-Next Generation EU & the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Innovation, Slovenia. Research was carried out within the project entitled “Establishing an environment for green and digital logistics and supply chain education”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tomsana, A.; Itoba-Tombo, E.F.; Human, I.S. An analysis of environmental obligations and liabilities of an electricity distribution company to improve sustainable development. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Papadopoulos, T.; Luo, Z.; Roubaud, D. Upstream supply chain visibility and complexity effect on focal company’s sustainable performance: Indian manufacturers’ perspective. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 290, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Sui, Y.; Wang, H. Sustainable development for shipping companies: A supply chain integration perspective. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 98, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.H. Applications of smart technologies in logistics and transport: A review. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 153, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shee, H.; Miah, S.J.; De Vass, T. Impact of smart logistics on smart city sustainable performance: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 821–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbivska, L.; Zhygalkevych, Z.; Fisun, Y.; Chobitok, I.; Shvedkyi, V. Digital technologies as a tool of efficient logistics. Rev. Univ. Zulia 2023, 14, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Raw Materials Alliance. European Raw Materials Alliance for a More Resilient and Greener Europe. 2022. Available online: https://erma.eu/european-raw-materials-alliance-for-a-more-resilient-and-greener-europe/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Pimenov, D.Y.; Mia, M.; Gupta, M.K.; Machado Á, R.; Pintaude, G.; Unune, D.R.; Khanna, N.; Khan, A.M.; Tomaz, Í.; Wojciechowski, S.; et al. Resource saving by optimisation and machining environments for sustainable manufacturing: A review and future prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 166, 112660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadollah, A.; Nasir, M.; Geem, Z.W. Sustainability and optimisation: From conceptual fundamentals to applications. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environmental Agency (EEA). Transport and Environment Reporting Mechanism (TERM)—Aviation and Shipping Emissions in Focus. 2019. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/articles/aviation-and-shipping-emissions-in-focus/download.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Miller, J.; Skowronski, K.; Saldanha, J. Asset ownership & incentives to undertake non-contractible actions: The case of trucking. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 58, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregurec, I.; Tomičić Furjan, M.; Tomičić-Pupek, K. The impact of COVID-19 on sustainable business models in SMEs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanković, K.W.; Maehle, N. Co-Creating Value for Business and Society: A B2B Sharing Economy Ecosystem Perspective. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 19, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasil, M.M.; Chopdar, P.K.; Buhalis, D.; Das, S.S. Value co-creation in the sharing economy: Revisiting the past to inform future. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1443–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antikainen, M.; Aminoff, A.; Heikkilä, J. Business model experimentations in advancing B2B sharing economy research. In Proceedings of the ISPIM Innovation Symposium, Stockholm, Sweden, 17–20 June 2018; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, A.; Trenz, M.; Veit, D. Three Differentiation Strategies for Competing in the Sharing Economy. MIS Q. Exec. 2019, 18, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, A. Challenges and Solution Approaches for Blockchain Technology. Doctoral Dissertation, Universität Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ocicka, B.; Wieteska, G. Sharing economy in logistics and supply chain management. LogForum 2017, 13, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissimi, M.C.; Creazza, A. The role of the enabler in sharing economy service triads: A logistics perspective. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2022, 5, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondys, K. Implementation of the Sharing Economy in the B2B Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. The B2B Sharing Economy Is Growing. So Are the Associated Risks. Built In. 2021. Available online: https://builtin.com/articles/b2b-sharing-economy-vetting (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Pathak, B.; Ashok, M.; Tan, Y.L. Value co-destruction: Exploring the role of actors’ opportunism in the B2B context. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laczko, P.; Hullova, D.; Needham, A.; Rossiter, A.-M.; Battisti, M. The role of a central actor in increasing platform stickiness and stakeholder profitability: Bridging the gap between value creation and value capture in the sharing economy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 76, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sposato, P.; Preka, R.; Cappellaro, F.; Cutaia, L. Sharing economy and circular economy. How technology and collaborative consumption innovations boost closing the loop strategies. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhlia, S.; Davila, A.; Cumbie, B. Trust, but verify: The role of ICTs in the sharing economy. In Information and Communication Technologies in Organizations and Society: Past, Present and Future Issues; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, H. Sharing economy: A potential new pathway to sustainability. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2013, 22, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobel, O. Coase and the platform economy. In Forthcoming in Sharing Economy Handbook; University of Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Kietzmann, J. Ride on! Mobility business models for the sharing economy. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, J.; Tainio, M.; Cheshire, J.; O’Brien, O.; Goodman, A. Health effects of the London bicycle sharing system: Health impact modelling study. BMJ 2014, 348, g425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mi, Z. Environmental benefits of bike sharing: A big data-based analysis. Appl. Energy 2018, 220, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Huang, R. How to achieve sustainable development of smart city: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 27, 8835–8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, H. Sharing economy: Promote its potential to sustainability by regulation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, M.; Jawab, F.; Arif, J.; Khaoua, Y.; El Jaouhari, A.; Moustabchir, H. From City Logistics to a Merger of Smart Cities and Smart Logistics. In Proceedings of the 2022 14th International Colloquium of Logistics and Supply Chain Management (LOGISTIQUA), EL JADIDA, Morocco, 25–27 May 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczak, J.; Kijewska, K. Smart Logistics in the development of Smart Cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 39, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G.; Ilıcak, Ö. Smart urban logistics: Literature review and future directions. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 81, 101197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, K. Smart city logistics on cloud computing model. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 151, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, A.; Borgarello, M.; Viani, S.; Maggiore, S.; Nsangwe-Businge, C.; Caruso, C. Estimating the potential of ride sharing in urban areas: The Milan metropolitan area case study. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2021, 9, 1080362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Nguyen, D.K.; Tian, X.L. Assessing the impact of the sharing economy and technological innovation on sustainable development: An empirical investigation of the United Kingdom. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 209, 123743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Franklin, R. From the digital Internet to the physical Internet: A conceptual framework with a stylised network model. J. Bus. Logist. 2021, 42, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Jin, M.; Li, S.; Feng, D. Smart logistics based on the internet of things technology: An overview. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 24, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C. The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S.; Lehner, M. Defining the sharing economy for sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boar, A.; Bastida, R.; Marimón, F. A Systematic Literature Review. Relationships between the Sharing Economy, Sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.H.-W.; Tseng, M.-L.; Wu, K.-J.; Cheng, C.-F. Factors influencing the adoption of sharing economy in B2B context in China: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 175, 105892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C.; Öberg, C.; Sandström, C. How sustainable is the sharing economy? On the sustainability connotations of sharing economy platforms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderluh, A.; Hemmelmayr, V.C.; Nolz, P.C. Sustainable Logistics with Cargo Bikes—Methods and Applications. In Sustainable Transportation and Smart Logistics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasińska-Morawska, K.; Sułkowski, Ł.; Buła, P.; Brzozowska, M.; Morawski, P. Smart Logistics—Sustainable technological innovations in customer Service at the Last-Mile Stage: The Polish Perspective. Energies 2022, 15, 6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakikes, I.; Nathanail, E. Simulation techniques for evaluating smart logistics solutions for sustainable urban distribution. Procedia Eng. 2017, 178, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosusi, A.A.; Ozdeser, H.; Seraj, M.; Adegboye, O.R. Achieving carbon neutrality in energy transition economies: Exploring the environmental efficiency of natural gas efficiency, coal efficiency, and resources efficiency. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 27, 2103–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duin, R.; Quak, H.J.; Anand, N.; Van den Band, N. Designing sharing logistics as a disruptive innovation in city logistics. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference Green Cities, Prague, Czech Republic, 2–4 May 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tetřevová, L.; Kolmašová, P. B2B sharing as part of the sharing economy model. In Proceedings of the Hradec Economic Days, Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 25–26 March 2021; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquier, A.; Carbone, V.; Massé, D. How to create value (s) in the sharing economy: Business models, scalability, and sustainability. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2019, 9, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O.; Palgan, Y.V.; Bradley, K.; Zvolska, L. A decade of the sharing economy: Concepts, users, business and governance perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulej, M. Teorije Sistemov (Str. 272); Ekonomsko-Poslovna Fakulteta: Maribor, Slovenija, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zenko, Z.; Mulej, M. Diffusion of innovative behaviour with social responsibility. Kybernetes 2011, 40, 1258–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, I.; Ochoa, J.J.; Gu, N.; Rameezdeen, R.; Statsenko, L.; Sandhu, S. A critical review of the key aspects of sharing economy: A systematic literature review and research framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargomatic. About Us. Available online: https://www.cargomatic.com (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Convoy. Home. Available online: https://convoy.com (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Delivery.com. Home. Available online: https://www.delivery.com (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- EasyPost. Home. Available online: https://www.easypost.com (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Find Storage Fast. Home. Available online: https://www.findstoragefast.com (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Flexe. About Us. Available online: https://www.flexe.com (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- FLOOW2. About Us. Available online: https://www.floow2.com (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- GarageScanner. Home. Available online: https://www.garagescanner.com (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Loadsmart. About Us. Available online: https://www.loadsmart.com (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- LogistCompare. Home. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/company/logistcompare.com (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Parkey. Home. Available online: https://www.parkey.io (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- project44. About Us. Available online: https://www.project44.com (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- ShipBob, Inc. About Us. Available online: https://www.shipbob.com (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- ShipMonk. About Us. Available online: https://www.shipmonk.com (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Shipwell. About Us. Available online: https://www.shipwell.com (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Stashbee Limited. Home. Available online: https://stashbee.com (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- StorQuest. Home. Available online: https://www.storquest.com (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Stowga. Home. Available online: https://www.stowga.com (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Uber Freight. About Us. Available online: https://www.uberfreight.com (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- uShip. About Us. Available online: https://www.uship.com (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Warehouse Exchange. Home. Available online: https://warehouseexchange.com (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- WiseTech Global. About Us. Available online: https://www.wisetechglobal.com (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- YourParkingSpace. About Us. Available online: https://www.yourparkingspace.co.uk (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Benoit, S.; Merfeld, K.; Tunn, V.S.; Schaefers, T.; Andreassen, T.W. The B2B sharing economy: Framework, implications, and future research. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 191, 115244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.P.; Kar, A.K.; Gupta, M.; Pappas, I.O.; Papadopoulos, T. Unravelling the dark side of sharing economy–managing and sustaining B2B relationships on digital platforms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 113, A4–A10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duin, R.; van den Band, N.; de Vries, A.; Muschoor, P.; el Ouasghiri, M.; Warffemius, P.; Anand, N.; Quak, H.J. Sharing logistics in urban freight transport: A study in 5 sectors. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference Green Cities 2022; Akademia Morska w Szczecinie: Szczecin, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.