Abstract

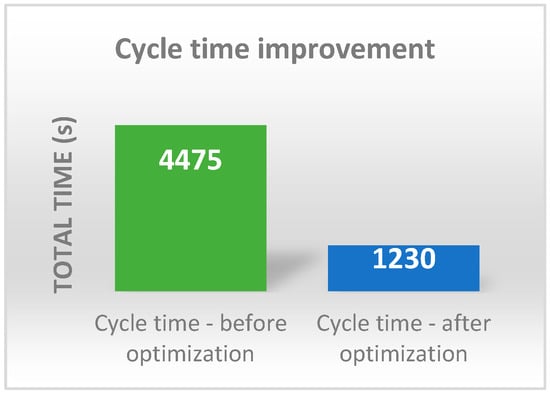

High-precision calibration of inertial measurement units for automotive safety systems combines fixed automated chamber cycles with semi-manual loading, alignment, and transfer. Motion waste and ergonomic constraints can therefore dominate throughput and cycle time stability. This study redesigns a production calibration workstation using time-and-motion analysis, operator observation, and structured root-cause analysis based on the Ishikawa diagram and the five whys. Three interventions were implemented and validated with pre- and post-measurements: bundled handling that consolidates full-set transfers and reduces non-value-adding motions; a fixture and material handling redesign with a manual lifting aid to reduce physical load and enable reliable single-operator operation; and a modular workstation layout that supports the phased addition of chambers. Total cycle time decreased from 4475 s to 1230 s, a 72 percent reduction, and weekly output rose from 800 to 4500 units without additional staffing or significant automation investment. Overall equipment efficiency improved from 75.3 percent to 85.2 percent, while the quality rate remained at 98.8 percent.

1. Introduction

High-precision calibration processes are fundamental to ensuring the reliability of modern automotive safety systems, particularly those that incorporate inertial measurement units (IMUs) as core sensing elements within advanced driver-assistance systems (ADASs) and autonomous driving platforms. IMUs capture multi-axis acceleration, angular rate, and orientation information that enable functions such as crash detection, emergency braking, lane stabilization, and vehicle motion prediction [1]. Because even small deviations in calibration can produce cascading decision errors, these units require stringent alignment and verification under controlled conditions to meet safety standards and regulatory expectations [2]. Consequently, calibration is categorized as a high-precision, safety-critical operation that is sensitive to process variation, operator workload, and workstation configuration [3].

Within operations management, extensive research has examined the roles of lean methods, ergonomic improvements, and workstation optimization in driving process efficiency, reducing variation, and improving takt-time compliance. Lean frameworks emphasize eliminating non-value-adding tasks and stabilizing workflows. At the same time, ergonomic research shows that reductions in physical strain, awkward posture, and handling complexity significantly enhance consistency in operator-driven tasks [4]. Although these principles are well documented in repetitive assembly and high-volume production, their application in precision-dependent calibration, where accuracy requirements impose unique handling and workflow constraints, remains limited in the literature. This represents a significant gap, as semi-manual calibration operations continue to play a vital role in high-reliability manufacturing environments [5].

Calibration operations involving IMUs are partially automated test chamber routines, and data logging is typically machine-driven. Yet, the surrounding activities, such as fixture handling, positioning, alignment, and transfer, remain manual. As illustrated in Figure 1, IMU-based airbag control units require precise, repeatable placement into specialized fixtures before calibration can proceed. This hybrid arrangement creates bottlenecks governed not only by equipment capabilities but also by human-factor constraints, including lifting effort, reach distances, cognitive load, and movement frequency [6]. Such environments differ fundamentally from traditional assembly lines, requiring joint consideration of ergonomics, lean flow, and human–machine interaction principles within OM theory [7].

Figure 1.

Illustrative examples of airbag control units used in automotive applications. Images are for explanatory purposes only and are not linked to any specific product or customer [8,9,10].

1.1. Background and Theoretical Motivation

The operation management literature has long emphasized reducing non-value-adding activities, simplifying workflows, and stabilizing process variability to achieve efficient, reliable production performance. Lean frameworks advocate systematic removal of waste (Muda), continuous improvement (Kaizen), and implementation of standardized work to enhance throughput and operational stability [11]. However, while these principles are widely applied in assembly processes and high-volume manufacturing, their theoretical application in precision-dependent calibration environments where accuracy demands strongly constrain workflow design remains significantly underdeveloped. This gap suggests a need to expand OM theory beyond traditional assembly contexts to account for hybrid processes that combine manual precision with automated testing routines.

Ergonomic science contributes additional insights into performance in semi-manual operations by demonstrating how physical strain, posture, reach distance, and repetitive handling motions influence operator fatigue and error rates. These ergonomic effects become amplified in tasks involving delicate sensor handling or precise alignment, as small deviations may compromise accuracy or increase rework [12]. Integrating ergonomic principles into operations management frameworks has been shown to improve cycle-time consistency, reduce operator burden, and enhance system reliability in high-reliability sectors. Yet, integrating ergonomics with lean principles, particularly in sensor calibration, remains an emerging research frontier with limited theoretical development.

Recent advances in OM research highlight the growing importance of hybrid human–machine systems, in which human dexterity and machine precision must be jointly optimized to achieve system-wide performance. Studies show that digitalized work environments, augmented feedback systems, and partially automated workflows reshape operator roles and introduce new interactions between ergonomic factors and operational efficiency [13]. In precision calibration processes such as IMU alignment, operators perform critical tasks that cannot yet be fully automated, making ergonomic load, motion economy, and workstation configuration key determinants of takt-time adherence and process robustness. Despite this relevance, OM theory has not fully articulated how human factors and lean design jointly influence performance in calibration settings where accuracy constraints dominate.

Taken together, these bodies of literature indicate that precision calibration environments lie at the intersection of lean process design, ergonomic intervention, and human–machine task allocation. Yet, empirical research connecting these domains remains limited, particularly in the context of automotive sensor calibration. This gap highlights the need for theory-building studies that explore how lean workflow redesign, ergonomic improvements, and modular workstation configuration jointly influence operational outcomes such as cycle-time stability, throughput, and scalability under demand uncertainty [14].

Motivated by this gap, this study examines how lean work redesign and ergonomic intervention jointly shape throughput, cycle-time stability, and scalable capacity planning in a semi-manual, precision-dependent calibration workstation for inertial measurement units in automotive safety production. The novelty of this work lies in treating calibration as a hybrid human–machine system in which accuracy constraints constrain the design space and in which ergonomic load is not only a safety issue but also a direct driver of cycle-time variability and bottleneck behavior. This study contributes to operations management theory by identifying and empirically validating three linked mechanisms that explain performance change in this context: task consolidation through bundled handling, ergonomic load reduction that stabilizes execution and enables single operator operation, and modular workstation configuration that enables phased capacity expansion under demand uncertainty. Practically, this study provides a low-capital, implementation-ready framework for improving similar safety-critical calibration operations.

1.2. Operational Context and Process Characteristics

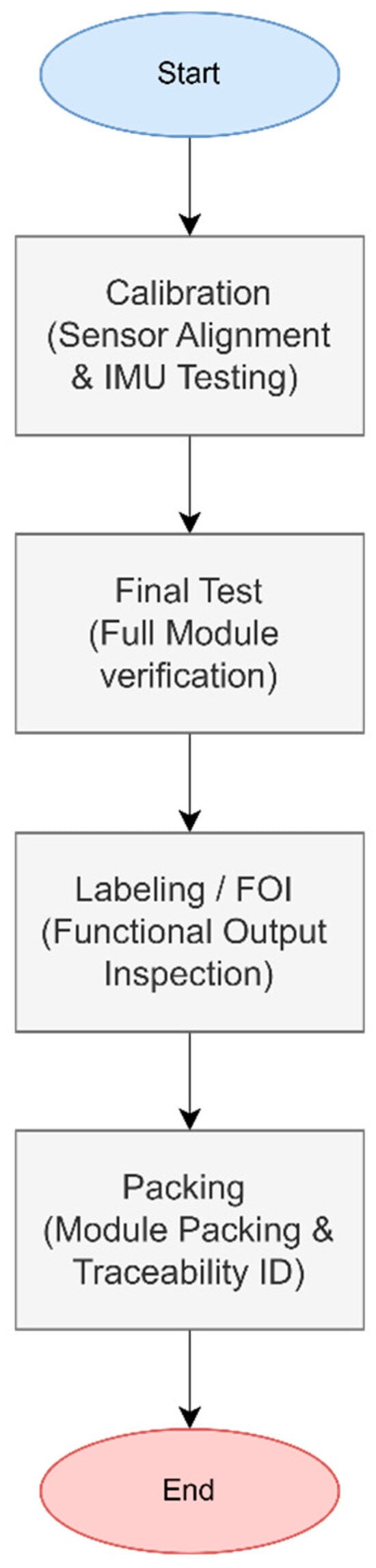

The calibration of IMUs takes place within a broader production value stream encompassing printed circuit assembly, electronic functional testing, labeling, and final system verification. As illustrated in Figure 2, the calibration stage sits at the center of this flow, acting as a transitional bottleneck between upstream assembly and downstream validation. Because calibration ensures sensor accuracy before final module integration, any inefficiencies at this stage propagate immediately to subsequent testing stations, creating work-in-process (WIP) accumulation and delaying throughput. Conversely, variability in upstream assembly arrival rates generates uneven input patterns that amplify takt-time fluctuations, complicated capacity planning, and resource scheduling [6,15].

Figure 2.

End-of-Line Manufacturing & Quality Assurance Workflow.

Unlike conventional assembly sequences, where task timing is relatively stable, calibration workflows exhibit hybrid characteristics combining automated chamber cycles with manual positioning, fixture loading, and handling steps. Operators must precisely align each IMU module within specialized fixtures and engage test initiation protocols that cannot be fully automated due to sensor tolerances. In the baseline state, fixture loading included a manual fastening/unfastening step using screw connections to secure the fixture during IMU positioning. This screw-based operation was treated as a distinct element in the time study and required approximately ~3 min per fixture-loading operation. These manual fastening steps contributed directly to operator-dependent variability during the loading/unloading portion of the cycle. This combination of machine-driven accuracy and human-driven flow introduces additional variability: ergonomic load, reach distance, and alignment difficulty directly influence cycle-time repeatability. Research in complex human–machine systems highlights that such interdependence increases the likelihood of bottleneck formation when operator performance interacts with fixed equipment cycle times [16].

The positioning of calibration within this flow magnifies its sensitivity to variability. Upstream disruptions such as assembly rework, operator delays, or PCB shortages immediately alter the arrival pattern into calibration. At the same time, downstream test stations depend on stable calibration output to maintain line balance. This dynamic reinforces classical bottleneck theory, which argues that overall system throughput is constrained by the slowest or most variable process stage [17]. In calibration environments, this bottleneck behavior is further intensified by ergonomic load, fixture complexity, and manual alignment requirements.

Given the interplay between manual precision and automated testing routines, calibration represents an operational domain where performance is shaped simultaneously by human ergonomics, equipment architecture, and flow variability. These characteristics underscore the need to rethink traditional OM constructs, such as takt design, workstation layout, ergonomic task structuring, and modular capacity scaling, within precision-critical calibration systems. Related ergonomics and time-and-motion approaches have been applied in manufacturing to link operator motion, handling effort, and execution variability to performance outcomes [18].

Baseline measurements confirmed that the calibration station was constrained mainly by manual handling and operator-dependent variability rather than by the automated chamber routine alone. Currently, the workstation supports 800 units per week. It requires two operators, with a production time of 163 s per unit, a quality rate of 98.8 percent, and an overall equipment efficiency of 75.3 percent. In comparison, the maximum weekly shipment quantity was 2271 units. The complete end-to-end cycle, including loading, unloading, movement, alignment, and chamber preparation, was approximately 4475 s.

1.3. Root-Cause Diagnosis Using Ishikawa and 5 Whys

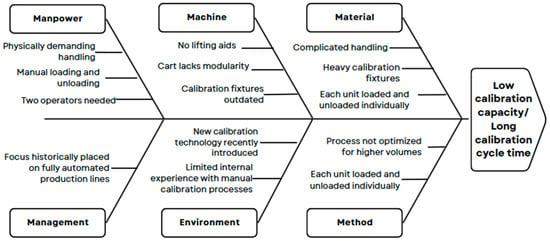

To identify the drivers of inefficiency in the calibration process, a structured root-cause analysis was conducted using the Ishikawa (cause-and-effect) method. The analysis grouped potential causes into five classical operational categories: manpower, machine, material, method, and management. As shown in Figure 3, these factors collectively influence cycle-time variability, ergonomic strain, and overall process stability. Ishikawa analysis is widely used across domains to visualize cause–and–effect structures and uncertainty in complex processes [19]. The Ishikawa analysis was implemented as an evidence-guided diagnosis, not only as a brainstorming exercise. First, the problem statement was defined as low calibration capacity and a long calibration cycle time, based on baseline time-study records and direct observation of the workstation. Second, potential causes were identified through repeated Gemba observations, operator walk-throughs, and recorded time elements, such as handling, walking, waiting, and loading. Each candidate’s cause was retained only if it was observed directly, consistently reported by operators, or supported by time-measured data. Third, the shortlisted causes were screened for their expected impact on cycle time and stability, and the most influential causes were then traced using the five whys to link observable symptoms, such as long loading times or operator fatigue, to actionable root causes in fixture design, material handling, and process flow. This step links the diagnostic results in Figure 3 to the intervention domains implemented and evaluated in Section 3 and Section 4.

Figure 3.

Ishikawa Diagram for Low Calibration Capacity/Long Calibration Cycle Time.

The manpower dimension revealed substantial ergonomic challenges, including excessive physical load, repetitive lifting, and two-operator dependency for fixture handling. These conditions increase operator fatigue and are known to degrade consistency in precision-dependent tasks, an effect widely recognized in human–factors engineering and operations literature [20]. Operators also performed non-value-adding actions, such as repositioning fixtures and walking between stations, which added motion waste that directly contributed to takt-time instability. This aligns with prior research showing that physical strain and unnecessary motion significantly elevate cycle-time variation in semi-manual production environments.

The machine category highlighted limitations in existing calibration fixtures and carts. The fixtures required substantial manual force to load and unload, while the cart system lacked modularity, forcing operators to manipulate individual trays rather than consolidated bundles. In OM theory, such equipment-related constraints are recognized as structural sources of waste, as they restrict flow, increase handling time, and limit opportunities for standardization and scalability [21]. Moreover, the absence of ergonomic fixture design created a mismatch between operator capability and task requirement, an issue commonly associated with error propagation and inconsistent cycle times in precision-critical work.

Process-related causes included redundant handling steps, an unoptimized sequence flow, and a lack of task consolidation. Operators transferred units one by one, rather than in batches, generating unnecessary touchpoints and increasing overall movement. Such issues are consistent with lean research showing that fragmented workflows lead to elevated non-value-added time, motion waste, and instability in cycle-time adherence [22]. Furthermore, the absence of standardized work instructions led to procedural ambiguity, resulting in discrepancies across operators and shifts.

Finally, management-related factors included inadequate anticipation of future demand increases, limited consideration of operator ergonomics in prior workstation designs, and insufficient alignment between production planning and capacity constraints. These gaps led to reactive rather than proactive capacity management, conflicting with OM best practices in scalable system design and bottleneck mitigation. As automotive sensor demand grows, these systemic weaknesses further compromise the calibration stage’s ability to respond effectively to rising call-offs.

1.4. Research Questions and Study Contributions

Prior literature in work measurement and lean operations emphasizes method/time study, standardization, and systematic elimination of non-value-adding work as core mechanisms for improving flow and performance in industrial processes [23,24,25]. In parallel, ergonomics and human factors research shows that redesigning work systems can improve both worker well-being and operational performance (e.g., productivity and quality), and controlled industrial evidence reports measurable performance gains from ergonomically improved workstations [26,27]. For hybrid human–machine systems, automation changes—not just replaces—human work, shifting coordination demands and influencing performance stability depending on how functions are allocated between people and machines [16]. Although integrated lean–ergonomics case studies demonstrate that simultaneous operational and human-factor improvements are feasible, these studies still provide limited guidance on how these mechanisms interact in precision-dependent calibration environments, where accuracy constraints, safety/quality gates, and tool–fixture interfaces shape which changes are feasible [28]. At the same time, case-based empirical research is widely recognized as a strong approach for developing and refining operations management theory in complex real-world settings, especially when controlled experimentation is impractical, and context matters [29,30,31,32,33]. Table 1 summarizes how this study is positioned relative to these research streams, the metrics they typically report, and why direct numeric benchmarking across sites is often not meaningful. Building on the theoretical gaps and the root-cause analysis presented earlier, this study addresses the following research questions:

Table 1.

Study positioning relative to established research streams, typical metrics, and comparability constraints.

RQ1:

How do lean-inspired task consolidation and bundled handling mechanisms reduce non-value-adding time in high-precision calibration operations?

RQ2:

How does ergonomic load reduction influence operator performance and cycle-time stability in semi-manual, accuracy-critical calibration processes?

RQ3:

How can modular workstation design support scalable capacity expansion under fluctuating demand while preserving calibration accuracy.

2. Research Design and Optimization Methodology

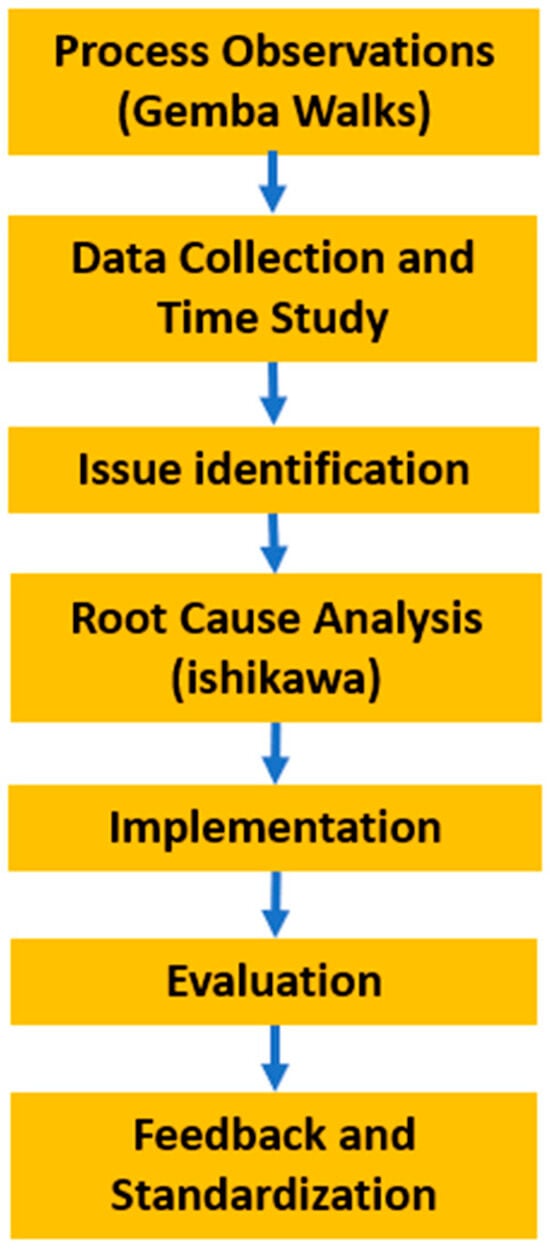

This study adopts a field-based, theory-building research design consistent with contemporary approaches in operations management, where empirical observation and iterative intervention provide the foundation for generating practically relevant and theoretically meaningful insights [29,30,31]. The research process followed a structured sequence: direct process observation, systematic data collection, issue identification, root-cause analysis, pilot implementation of improvement concepts, evaluation, and, finally, standardization of successful practices. This multi-stage methodology ensures methodological rigor by linking an in-depth understanding of actual work practices with analytical diagnosis and evidence-based refinement. The complete method is illustrated in Figure 4, which visually summarizes the sequential logic and iterative refinement embedded in the research process [38].

Figure 4.

Optimization methodology for calibration process.

The first-stage process observation component of Gemba Walks focused on directly examining operator activities at the calibration workstation to reveal real operational behaviors that are often hidden in procedural documentation. Observing operator posture, fixture interaction, walking patterns, and coordination with both upstream and downstream stations enabled the identification of non-value-adding movements, ergonomic constraints, and sources of variability that contribute to takt-time instability. Such direct observation is foundational in lean-based empirical research, as it allows researchers to uncover system inefficiencies rooted in human–equipment interaction and actual workflow execution rather than planned or assumed processes [4,5].

The second stage involved data collection and time studies, which provided quantitative evidence of the calibration process’s performance characteristics. Using established work-measurement procedures, cycle times, handling times, walking durations, and wait times were recorded across multiple operators and shifts. These measurements captured both average performance and sources of high-variance execution. Quantitative time studies are widely recognized in operations research and lean practice for providing the empirical grounding necessary to diagnose bottlenecks, validate the presence of non-value-adding work, and prioritize improvement opportunities [12,13]. Sample anonymized element-level time-study results underlying the cycle-time analysis are provided in Appendix A.

The third stage issue was identified, and root-cause analysis synthesized insights from observations and measurements into a structured diagnosis. The Ishikawa diagram revealed that ergonomic strain, fragmented workflows, non-modular equipment, and inconsistent standardization were significant sources of cycle-time variability. Applying the 5 Whys technique helped distinguish surface-level symptoms, e.g., long loading times or operator fatigue, from structural causes embedded in workstation design, fixture characteristics, and process flow. These analytical tools are widely recommended in operations and ergonomics literature for uncovering systemic drivers of variability that undermine operational performance [18,19,21,22].

The final stages of implementation, evaluation, and standardization transformed analytical insights into actionable improvements. Interventions included a redesigned loading fixture enabling bundled handling, a modular cart and worktable to support batch preparation, a simple lifting aid to reduce ergonomic load, and layout modifications for additional calibration chambers. These pilots were evaluated using cycle-time metrics, ergonomic assessments, and operator feedback, demonstrating significant improvements in stability and throughput. Successful changes were institutionalized through updated standard operating procedures and training, consistent with lean principles, emphasizing the role of standardized work in sustaining operational gains [17,37].

Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) Procedure

To select the most effective improvement concept while balancing time, ergonomics, and implementation constraints, we applied a transparent multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) procedure (weighted decision matrix) supported by direct time-study measurements and structured shop-floor observation.

- Procedure

- Generate candidate concepts from the cause analysis (Ishikawa diagram + 5 Whys) and operator/engineer workshops, then remove non-feasible options.

- Apply hard constraints (must-pass gates): safety compliance; compatibility with the existing calibration equipment; no adverse impact on product quality; and practical implementation within the production cell.

- Score each feasible concept against the criteria in Table 2 using a 1–5 scale (1 = worse than baseline, 3 = similar to baseline, 5 = clearly better than baseline).

Table 2. Criteria, measurement basis, and scoring used in the decision matrix.

Table 2. Criteria, measurement basis, and scoring used in the decision matrix. - Compute an overall concept score as a weighted sum: Sk = Σi (wi · s{k,i}), where wi are criterion weights (Σ wi = 1) and s{k,i} are 1–5 scores for concept k.

- Validate robustness using observed distributions of cycle-time elements: improvements were required to hold for the bulk of observed cycles and operators. Specifically, we checked that the improved configuration reduced time not only on average but also across the central spread of observations (5th–95th percentile range), thereby avoiding a design that helps only extremes or rare conditions.

- Select the top-ranked concept(s) and confirm in a pilot implementation, followed by a post-change time study using the same element definitions.

Rationale for using the 5th–95th percentile check: production data include occasional atypical events such as interruptions, rare rework, or unusually fast/slow cycles. Using the 5th–95th percentile range focuses the robustness evaluation on the central majority of observations while limiting the influence of extremes, which improves generalizability across operators and shifts.

3. Operational Improvement Interventions

This section presents the set of operational interventions introduced to address the inefficiencies identified during the diagnostic phase. Consistent with contemporary research in operations management, the interventions were designed to simultaneously enhance process stability, reduce ergonomically induced variability, and increase capacity without resorting to capital-intensive automation. The redesigned workflow and ergonomic interventions enabled a major capacity jump. The existing system delivered 800 units/week. After ergonomic optimization, material-handling redesign, and the manual lift, the workstation supported 4500 units/week with a single operator. The improvements, therefore, target both structural workflow redesign and human–machine interaction, reflecting the hybrid operational characteristics of precision calibration environments [18,22].

The interventions were grouped into four domains:

- Ergonomic and handling optimization;

- Redesign of material-handling equipment;

- Introduction of a manual lifting aid;

- Preparation for modular capacity scaling through additional calibration chambers.

Each intervention was evaluated for its impact on cycle time, operator effort, and overall process reliability, allowing for a systematic assessment of operational performance improvements across human, technological, and flow dimensions [17,37].

Table 3 summarizes the workstation’s baseline performance indicators. A cycle time of 163 s per unit, significant manual handling, and a two-operator dependency underscored the structural constraints limiting throughput and takt-time adherence under growing demand. These conditions substantiated the need for an integrated redesign of the loading fixture, material-handling equipment, and workstation layout [15,22].

Table 3.

Key production and performance indicators.

To make the optimization logic explicit, the redesign employed a structured concept-selection procedure. Candidate alternatives were generated for each intervention domain based on the Ishikawa results and Gemba observations, then screened using a multi-criteria decision matrix. The primary objective was to reduce total manual time per calibration cycle while maintaining calibration quality and respecting constraints on chamber interface geometry, floor space, safety, and the requirement for minimal capital change. Alternatives were scored using multi-criteria: expected reduction in cycle time based on the time study; expected reduction in physical load and awkward postures based on observed handling and operator feedback; and implementation feasibility within the existing workstation. The selected concepts were then piloted and validated using the same time-measurement approach as in the baseline. Ergonomic suitability was assessed for a representative operator range by verifying reach, clearance, and lift heights for shorter and taller users, approximately spanning the 5th to 95th percentiles of the working population.

3.1. Ergonomic and Handling Optimization

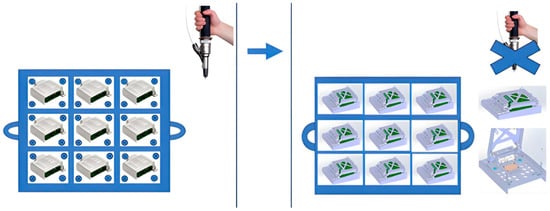

The existing one-by-one loading method resulted in excessive shoulder and lower back strain, repetitive lifting cycles, and unstable execution patterns. The redesigned loading fixture, as shown in Figure 5, introduces bundled handling, reducing 6–10 individual lifts to only one consolidated ergonomic motion per batch. Alignment guides and a simplified clamping mechanism further reduce the demands on operator precision. Specifically, the simplified clamping mechanism replaces the baseline screw-fastening/unfastening step during fixture loading, removing approximately ~3 min of manual work per loading operation (see Section 4.1.1). Literature consistently shows that ergonomic strain correlates strongly with motion variability and takt-time instability in hybrid human–machine systems [18,20,38].

Figure 5.

Improvement from the current to the new loading fixture design.

3.2. Material Handling Redesign

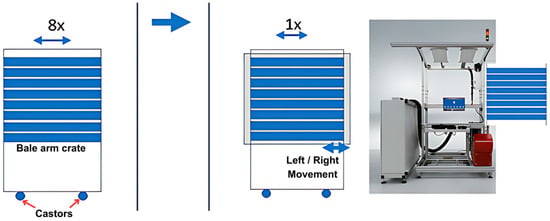

An unstructured cart and a narrow, unstable worktable exacerbated material flow problems. The redesigned manual cart, as shown in Figure 6, adds modular trays that enable pre-staging multiple batches, reducing walking cycles and micro-interruptions. Operators were required to perform frequent one-by-one lifts, twisting motions, and manual fixture alignment, all of which exceeded recommended ergonomic thresholds for shoulder and lower back loading.

Figure 6.

Improvement from the current to the new manual cart and worktable.

This increases flow stability and reduces dependence on operator judgment. Likewise, the redesigned worktable, as shown in Figure 6, introduces widened loading zones and alignment guides, enabling predictable tray positioning. Lean workstation research consistently demonstrates that modular staging and reduced micro-motions improve stability, reduce waste, and enhance throughput in semi-manual operations. The new solution reduced the cycle time, eliminated redundant handling between the cart and calibration chambers, and enabled easier single-operator management.

Digital equipment modeling and layout verification. To support the redesign of the manual cart, worktable, and fixture-transfer interfaces, the key workstation objects (cart, trays, fixture set, worktable, chamber access envelope, and lift interface) were represented as simplified 3D geometry in a commercial parametric CAD environment (SolidWorks 2024). The purpose of the model was not detailed mechanical simulation, but clearance and interface verification: (i) confirming that bundled trays and the fixture set fit within the available cell footprint and chamber access zones; (ii) checking reach distances and hand access to grasping points; and (iii) validating transfer paths between the staging area, worktable, and chambers before hardware fabrication. Due to industrial confidentiality, detailed CAD files and exact tool geometries are not shared; however, the redesign principles, observed handling effects, and performance outcomes are reported in full.

Movement and load assessment (observation-based, three-plane review). Analysis of operator movement and physical load was primarily evidence-based and conducted during normal production. It combined time-and-motion measurements (element-level timings), repeated Gemba observations of the complete loading/unloading cycle, and operator feedback used to confirm recurrent handling difficulties and unsafe/unstable motions. Loads were quantified using the measured masses of the handled items (fixture set, trays/containers, and intermediate assemblies), and the redesign targeted reductions in peak manual lifts, sustained carries, and awkward postures. In addition to overall handling effort, key actions were reviewed in the three principal anatomical planes: sagittal (forward bending/extension), frontal (side reaching/abduction), and transverse (trunk and shoulder rotation). The final solution reduces trunk flexion and rotation during transfers, lowers shoulder elevation by bringing grasp points into the preferred reach zone, and stabilizes placement through alignment features and standardized staging positions.

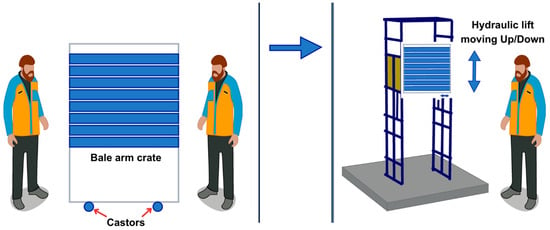

3.3. Introduction of Manual Lifting Aid

Current State: Manual lifting of fixtures and loading/unloading into the calibration chamber required two operators due to the fixtures’ weight and ergonomics. This increased handling time and operator physical strain.

Proposed State: A manual lift was introduced to assist with loading and unloading fixtures (or the new internal cart section) into and out of the calibration rack. This solution allows one operator to perform the task safely and efficiently.

Weight/handling assumptions and influencing factors: Each calibration fixture carries nine control units. The mass of one control unit is approximately 0.8 kg, resulting in 7.2 kg for the units per loaded fixture (9 × 0.8 kg). The calibration fixture itself, including tooling, guides, and clamping elements, is estimated at 10–12 kg, giving a total handled mass of approximately 17–19 kg; for reporting and comparison, 18.0 kg is used. This handled mass is unchanged between the baseline and improved states; the improvement affects the handling method and load distribution rather than the fixture content or weight. In the baseline state, the fixture is lifted manually by two operators, resulting in a peak manual load of approximately 9.0 kg per person. In the improved state, the manual lifting aid supports the fixture mass and the operator performs guided positioning and stabilization; the effective manual load is therefore estimated at approximately 3–5 kg, reflecting residual guiding/positioning forces rather than the full fixture weight. Based on workstation geometry, the baseline handling involved a vertical lift range of approximately 60 cm and a horizontal reach of approximately 60 cm, whereas the assisted handling reduced the vertical adjustment to approximately 20 cm and the horizontal reach to ≤30 cm.

Benefits: Implementing the manual lift reduced operating time by approximately 67%, minimized operator physical strain, and enabled faster, safer operations. The manual lifting aid, as shown in Figure 7, eliminates peak loads during tray transfer, ensuring vertical lifting occurs within the ergonomic safe zone.

Figure 7.

Integration of the manual lift into the calibration process.

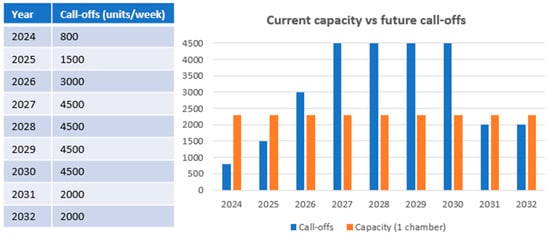

3.4. Preparation for Modular Capacity Scaling

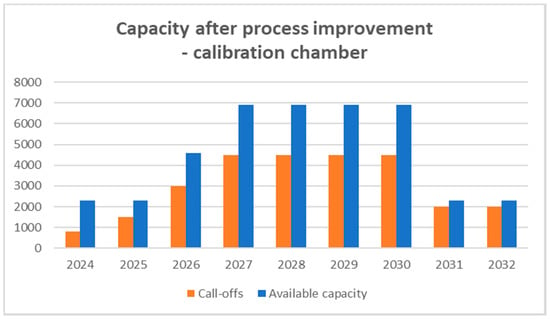

The projected annual call-offs revealed a structural mismatch between expected demand and the capability of the existing calibration setup. As shown in Figure 8, forecasted contracted call-offs surpass the current single-chamber capacity, motivating a phased modular expansion strategy.

Figure 8.

Future contracted call-offs vs. current chamber capacity.

While a single chamber is sufficient for low-volume periods 2024–2025 and 2031–2032, it cannot accommodate the substantially higher production requirements anticipated during 2026–2027 and 2028–2030. The chamber is permanently anchored and must remain precisely calibrated in situ, making relocation impractical and cost-prohibitive. This immobility underscores the need for a scalable workstation layout that seamlessly integrates additional chambers while maintaining environmental stability and uninterrupted calibration operations. This challenge is consistent with theories of bottleneck management in OM, where fixed-capacity resources constrain system throughput unless strategically elevated or reconfigured [15,17,37].

To accommodate rising production volumes, the workstation layout is redesigned to support phased expansion. The revised configuration ensures that present and future chambers remain fully accessible to both operators and maintenance personnel, avoid interference with testing and packaging operations, and preserve one-directional flow. This modular design philosophy aligns with lean principles emphasizing flexible, low-disruption scalability, enabling the system to absorb future demand spikes without major structural changes. By preparing the physical space, utilities, and operator pathways in advance, the calibration area becomes a “plug-and-produce” zone capable of incremental capacity elevation [22,35].

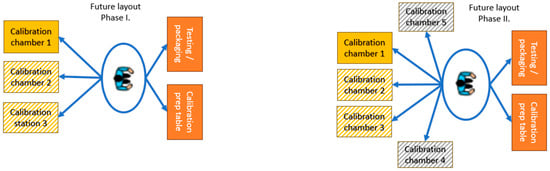

The capacity-scaling strategy is executed in two stages.

Phase I installs calibration chambers 2 and 3 to meet the high-volume requirements of 2026–2027.

Phase II prepares infrastructure for two additional chambers to support the even larger customer projects planned for 2028–2030, ensuring that expansion does not necessitate layout redesign or workflow disruption.

This phased approach reflects OM guidance on sequential system augmentation, where bottleneck elevation is achieved through carefully staged investments that minimize downtime and maximize throughput responsiveness [15,17]. Figure 9 illustrates the planned configuration for integrating additional chambers within the existing footprint.

Figure 9.

Plan for additional chamber introduction.

Beyond future scalability, the redesigned workflow and ergonomic interventions have already delivered substantial performance gains. The prior system supported approximately 800 units/week. Following ergonomic improvements, fixture redesign, material-handling optimization, and the deployment of the manual lift, the workstation now supports 4500 units/week with a single operator. When the additional chambers from Phases I and II are integrated, capacity is projected to rise to 6900 units/week, representing an eightfold improvement over the original baseline. These results demonstrate the synergistic effect of ergonomic enhancements, workflow stabilization, and modular layout planning as core levers for alleviating bottlenecks and improving end-to-end system throughput [15,17,37].

4. Evaluation of Operational Impact

This section presents a comprehensive assessment of the operational and system-level improvements achieved following the implementation of the redesign interventions. The evaluation considers ergonomic outcomes, cycle-time reductions, throughput gains, and capacity effects, followed by an economic appraisal of the investment. This dual analysis reflects established operations management practices, in which performance enhancement is validated through both technical efficiency and financial impact assessments [15,17,37].

4.1. Performance Evaluation and System-Level Impact

Before analyzing specific performance dimensions, it is essential to highlight that the implemented improvements collectively transformed the workstation’s behavior. The transition from handling individual fixtures to handling complete sets drastically reduced repetitive tasks, eliminated micro-motions, and enabled one operator to execute an operation previously dependent on two. These structural changes also enhanced flow predictability, simplified shift planning, and increased robustness in conditions of staff shortages, benefits typically emphasized in OM studies focused on capacity-constrained manual operations [15,22].

4.1.1. Cycle-Time Analysis

The optimization project resulted in a major reduction in the total calibration cycle. The original duration of the complete process, including loading, unloading, movement, alignment, and chamber preparation, was approximately 4475 s. After introducing the redesigned fixture, an improved cart-handling mechanism, and an ergonomic lifting solution, the cycle time was reduced to 1230 s, saving 3245 s per cycle. Figure 10 visualizes this improvement.

Figure 10.

Cycle time calculation and improvement.

These reductions stem from three mechanisms:

- Elimination of repetitive screw-fastening/unfastening during fixture loading (~3 min per operation in the baseline).

- Consolidation of fixture handling into full-set transfers rather than unit-by-unit motions.

- Removal of unnecessary walking between the worktable, cart, and chamber.

The magnitude of the reduction reflects documented findings that motion waste accounts for the largest proportion of cycle time in precision-dependent manual tasks [18,20,38].

4.1.2. Operator Effort and Ergonomic Benefits

The introduction of a manual lift, a modular fixture system, and a redesigned cart significantly reduced physical strain. Previously, the fixture weight and placement height required two operators for safe handling. With the new system, one operator can safely and consistently load and unload the entire fixture set. Observations showed reduced bending, twisting, and shoulder-level lifting, resulting in lower cumulative fatigue throughout the shift.

The reduction in ergonomic burden also stabilized operator performance. In manual calibration processes where precision, repeatability, and stability are critical, ergonomic variability often translates into cycle-time scatter and takt-time deviations. The improved setup, therefore, contributes not only to safety but also to flow stability, reinforcing conclusions from human–automation interaction research [16,18].

Manual handling analysis and influencing factors: To address manual-handling constraints that previously required two operators, a concise weight/handling exposure assessment was performed for the baseline and improved processes. The mass of handled items (fixture/tooling bundles and unit containers) was measured using a calibrated shop-floor scale; lift heights and horizontal reaches were measured using a tape measure referenced to the workstation datum height; and handling frequency was derived from the time-study sample. The assessment focused on the primary influencing factors affecting physical workload: handled mass, vertical lift range, horizontal reach, posture asymmetry (twisting), coupling/grip quality, and handling frequency. These factors were used as an ergonomic screening input to ensure that the transition from two-operator to one-operator operation did not increase individual physical workload and that peak manual load exposure was reduced by design (Table 4).

Table 4.

Manual handling exposure summary (baseline vs. improved).

4.1.3. Throughput Increase and Capacity Impact

From a productivity standpoint, the cycle-time reduction directly translated into a significant increase in throughput. The original system supported approximately 800 units/week, constrained by manual fixture handling, two-operator dependency, and non-standardized transfer motions. With the new setup, the workstation achieved 4500 units/week with a single operator, without requiring additional floor space or machinery.

This improvement also stabilized takt adherence, simplified scheduling, and strengthened resilience to operator shortages. In terms of scalability, the modular layout and improved handling logic aligned the process with predictable future expansions. As shown in Figure 11, after adding calibration chambers in planned phases, the total available capacity rises to 6900 units/week, far above the maximum customer forecast of 4500 units/week, thus creating a strategic buffer for business fluctuations and new project onboarding.

Figure 11.

Capacity increase visualization.

4.1.4. Summary of Key Operational Parameters

Table 5 summarizes the key operational parameters before and after the improvement project. The production time per unit decreased from 163 s to 95 s, the operator count decreased from 2 to 1, and OEE increased from 75.3% to 85.2%. Notably, the quality rate remained stable at 98.8%, confirming that higher throughput did not compromise performance.

Table 5.

Comparison of key operational parameters—current vs. future state.

The improvement in OEE can be attributed to reduced manual handling time, fewer idle periods during loading/unloading, standardization of handling equipment, and more consistent execution of cycle times. These outcomes align with lean workstation design literature, which highlights how modularity, ergonomic stability, and standardized equipment enable measurable improvements in both efficiency and quality [5,22].

4.2. Financial Evaluation and Return-on-Investment Analysis

The financial assessment followed lean operations management recommendations by evaluating the payback of each improvement phase relative to realized and projected capacity increases. Investments were structured into phases that aligned with forecasted customer call-offs, thereby avoiding premature capital expenditure. Table 6 summarizes the investment allocation across the ergonomic redesign, workstation modification, and expansion of calibration chambers. Table 7 presents the corresponding annual benefits.

Table 6.

Staged investment plan.

Table 7.

Key input parameters for ROI evaluation.

This phased investment strategy ensures that capacity is available when required, provides flexibility for future volume fluctuations, and maximizes financial efficiency, consistent with established financial evaluation principles in OM [29,30].

Return-on-Investment (ROI) Outcome

The ROI analysis from the Table 8 shows that the Phase 1 investments pay back almost immediately. In 2024 alone, the return exceeded 42,000%, driven by labor consolidation and cycle-time reduction. Sustained production volumes and the staged expansion strategy drive cumulative ROI to grow exponentially, reaching 84,000% by 2032. The analysis also highlights how aligning investment with real demand reduces financial risk while enabling continuous competitiveness.

Table 8.

Results of the ROI analysis.

The ROI outcome reflects OM theory on bottleneck elevation and flow-based economic gains: when throughput increases without a proportional increase in fixed costs, the financial return becomes disproportionately large [15,17]. The results, therefore, validate both the operational and economic soundness of the proposed improvements.

5. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that targeted ergonomic improvement, workstation redesign, and modular capacity planning can collectively reshape system performance in precision-dependent calibration environments. The convergence of human-factor optimization and structural workflow redesign produced outcomes far exceeding incremental improvements, yielding step-change improvements in cycle time, throughput, labor utilization, and scalability. These findings reinforce a core principle in operations management: interventions that simultaneously reduce variability and elevate bottlenecks deliver nonlinear improvements in overall system capability [15,17].

5.1. Quantitative Comparative Impact

Compared with the baseline workstation configuration, the integrated redesign produced a clear step change in measurable operational performance. The end-to-end calibration cycle time decreased from 4475 s to 1230 s, representing a 72% reduction. The production time per unit decreased from 163 s/pcs to 95 s/pcs, corresponding to a 42% reduction. Weekly throughput increased from 800 to 4500 units/week, which is a 5.6-fold improvement, while output quality remained unchanged at 98.8%. Overall equipment efficiency increased from 75.3% to 85.2%, an improvement of 9.9 percentage points. The transition from a two-operator to a one-operator configuration was achieved without increasing individual physical workload, supported by reduced reach and lift exposure and assisted handling. Table 9 summarizes these before–and–after results and links each outcome to the primary intervention mechanism.

Table 9.

Before–after quantitative comparison of key outcomes and primary mechanisms.

5.2. Mechanism-Level Performance Drivers from Element Timing

The element-level time-study decomposition shows that the largest reductions were concentrated in manual handling and interface steps. Staging and preparation decreased from 413 s to 146 s in element E1, and loading and alignment decreased from 556 s to 231 s in element E2. Connector and interface actions decreased from 347 s to 113 s in element E4. The screw-fastening step in element E3, which required about 180 s per fixture-loading operation in the baseline, was eliminated through the redesigned securing approach. Transfer to the next stage decreased from 271 s to 69 s in element E8, and within-cell walking and handling decreased from 117 s to 52 s in element E9. Together, these reductions explain how ergonomic redesign and bundled handling reduced both total time and operator-dependent variability, enabling consistent single-operator execution under normal production conditions [18,20,38].

5.3. Ergonomics and Flow Stability in Hybrid Manual–Automated Calibration

A key insight concerns the interaction between ergonomics and flow stability. The redesigned fixture, manual lift, and modular cart system reduced physical strain while simultaneously reducing motion variation, which directly supports takt-time adherence. In environments where calibration precision depends on stable operator performance, ergonomic improvements do more than reduce fatigue; they improve system predictability by lowering the likelihood of micro-delays, restarts, and handling-related disturbances. This aligns with prior research indicating that human-centered design is an underutilized yet powerful lever for improving flow in hybrid manual–automated processes [18,20,38].

5.4. Modular Capacity Planning and Scalable Bottleneck Elevation

Another contribution is the demonstration of phased capacity expansion using a modular layout approach. The inability to relocate the original calibration chamber imposed a structural constraint, yet the redesigned layout enables additional chambers to be integrated without major disruption to ongoing operations. This supports both medium-term customer commitments and long-term strategic flexibility. By preparing the footprint, access envelopes, and flow pathways in advance, the system can elevate capacity through staged additions while preserving calibration integrity and reducing implementation risk, consistent with guidance on flexible manufacturing systems and capacity planning [18,20,38].

5.5. Methodological Implications for Operations Management Research and Practice

From a methodological perspective, this study demonstrates the value of combining direct time-and-motion study with structured diagnosis and transparent concept selection. Integrating element-level empirical evidence with a practical selection logic and system-level capacity planning provides a multi-level view that strengthens managerial decision-making. This approach responds to calls in the OM literature to connect micro-level operational detail with macro-level performance planning in real industrial settings [18,20,38].

5.6. Economic Implications of Human-Centered Redesign

Finally, the findings show that operational redesign can deliver substantial financial returns even before capital-intensive investments are made. The ROI outcomes indicate that ergonomic optimization and standardized material handling can yield significant value by eliminating labor redundancy, stabilizing flow, and improving effective utilization while maintaining quality. These gains are not only efficiency improvements; they strengthen responsiveness, reduce overload risk, and support reliable performance in safety-critical environments. This underscores the economic logic of improving human–machine coordination as a strategic operations lever.

6. Managerial Implications

The results of this study provide several actionable insights for managers responsible for safety-critical, precision-dependent manufacturing operations. First, the findings demonstrate that ergonomic design should be treated as a strategic operational lever rather than a compliance requirement. Simple redesigns—such as consolidated fixture handling, assisted lifting, and modular staging—can unlock capacity gains of several hundred percent. Managers overseeing manual or semi-manual calibration processes should therefore prioritize systematic ergonomic audits before considering automation investments, as these low-cost interventions can remove substantial process variation and stabilize takt-time performance.

A second implication concerns the design of scalable production layouts. The futurized-expansion model developed here shows how managers can prepare facilities for future volume increases without prematurely committing to high-cost equipment. Modular layouts, standardized interfaces, and predefined service zones provide a structural framework that supports growth while minimizing disruption to ongoing operations. This approach is particularly valuable in industries with fluctuating customer demand or long equipment qualification cycles, where early overinvestment carries significant financial and operational risk.

Third, the transition from a two-operator to a one-operator configuration highlights the importance of viewing labor efficiency holistically. Rather than focusing solely on headcount reduction, managers should evaluate how changes in fixture design, workstation geometry, and material flow influence operator stability, engagement, and performance consistency. Workforce planning for complex manual tasks should incorporate ergonomics, cognitive load, and repeatability metrics, rather than just labor hours, to ensure sustainable utilization in the long term.

A fourth implication relates to investment prioritization. The financial evaluation shows that targeted process improvements can deliver exceptionally high ROI even before capital expansion begins. Managers should therefore integrate operational diagnostics with financial modelling at the early stages of redesign projects, ensuring that investment decisions consider not only direct labor savings but also throughput gains, stability, and future scalability. Such integration prevents misalignment between operational opportunities and financial justification, enabling faster approval cycles for improvement initiatives.

Finally, this study underscores the importance of designing processes that enhance organizational resilience. By reducing manual variability, simplifying workflow dependencies, and preparing for future capacity through modular expansion, the redesigned system is less vulnerable to operator absences, equipment downtime, or sudden changes in customer call-offs. Managers aiming to build adaptive, disruption-resilient manufacturing systems can benefit from integrating ergonomic redesign, standard work, and modular layout planning as complementary components of a resilience strategy.

7. Conclusions

This study examined how ergonomic optimization, workstation redesign, and modular capacity planning can collectively improve the performance of a precision-intensive calibration process in the automotive electronics sector. The results show that the dominant constraints were not embedded in the automated chamber routine alone, but in the surrounding manual handling, alignment variability, and physical transfer operations that governed stability and repeatability across shifts. Accordingly, the interventions were designed to elevate the bottleneck by reducing ergonomic load and operator-dependent variation while preserving process reliability and workplace safety.

Based on a structured diagnostic assessment and empirical evaluation, the key conclusions are:

- Ergonomic and handling redesign delivered automation-like performance gains. Consolidated fixture handling, a manual lift, and redesigned material-handling equipment eliminated non-value-adding motion, stabilized execution, and reduced cumulative strain. These interventions reduced the end-to-end cycle time from 4475 s to 1230 s (−72%) and enabled predictable takt-time execution.

- Workflow standardization enabled reliable single-operator operation and major throughput expansion. By removing variability in loading and alignment tasks and improving flow stability, the process shifted from a two-operator to a one-operator configuration, and weekly throughput increased from 800 to 4500 units/week without major automation investment.

- Performance improvements were achieved without degrading output quality or operational consistency. The quality rate remained 98.8%, and overall equipment efficiency improved from 75.3% to 85.2%, indicating that productivity gains were achieved while maintaining process robustness in a safety-critical environment.

- Modular capacity planning provided a scalable and low-risk path for growth with strong economic justification. The redesigned calibration area supports phased installation of additional chambers, increasing capacity to a projected 6900 units/week without major reconfiguration. The ROI analysis indicates exceptionally high returns driven primarily by labor consolidation, cycle-time reduction, and increased system availability.

Taken together, these findings support an operation management perspective in which human-centered redesign is not a “local ergonomic upgrade” but a system-level lever that can alleviate bottlenecks, reduce variability, and unlock capacity in hybrid manual–automated processes. More broadly, this study contributes evidence that integrating ergonomic science, lean workstation redesign, and modular capacity planning can jointly shape operational and financial outcomes in precision-dependent manufacturing environments, offering actionable guidance for practitioners facing strict qualification constraints and fluctuating demand.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.; methodology, J.K.; formal analysis, M.N.R.; investigation, P.B.; resources, P.B.; data curation, I.O.; validation, I.O.; visualization, I.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.; writing—review and editing, M.N.R. and A.S.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S.; technical support, J.D.; manuscript proofreading, J.D.; critical review, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the European Union under the REFRESH—Research Excellence For Region Sustainability and High-tech Industries project (No. CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048) via the Operational Programme Just Transition. It was also supported by the project Students Grant Competition SP2025/065 titled “Research, Development, and Innovation in the Field of Transport and Logistics 2025,” financed by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports and the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Further information can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This appendix provides a concise, anonymized excerpt of the empirical time-study outputs used in the cycle-time analysis and workstation improvement design. To respect industrial confidentiality, all product identifiers, internal equipment codes, and layout-sensitive details were removed. Only generic task element names and their timing statistics are reported.

Timing protocol (summary): A calibration cycle is defined as the complete sequence from the start of loading the calibration setup through unloading and transfer of the calibrated units to the next internal step. The cycle was decomposed into repeatable elements with clearly defined start/stop boundaries (the table below). Manual elements were timed by direct observation during normal production; machine-controlled dwell time was taken from the equipment cycle indicator/log when available. The results are reported in seconds. Sampling size is indicated as N (baseline) and N (improved).

Sampling size: Multiple cycles were recorded under each condition. Exact N values are maintained in the time-study log and can be provided confidentially to the editor upon request.

Table A1.

Element-level time-study summary (anonymized; all values in seconds).

Table A1.

Element-level time-study summary (anonymized; all values in seconds).

| Element ID | Element Definition (Start/Stop Boundary) | Baseline (Two-Operator) Time (s) Mean ± SD (Min-Max) | Improved (One-Operator) Time (s) Mean ± SD (Min-Max) | Main Change Driver/Note |

| E1 | Stage components and fixtures at the workstation (from first contact with incoming carrier to components positioned for loading). | 413 ± 58 (320–520) | 146 ± 24 (110–190) | Reduced by consolidating items into stable bundles and pre-staging. |

| E2 | Load units into calibration fixture (s) and align (from first placement into fixture to aligned/ready for securing). | 556 ± 74 (440–710) | 231 ± 31 (180–295) | Reduced by improved reach/placement and a standardized handling sequence. |

| E3 | Secure/fasten fixture (if required) (from start of securing action to fixture fully secured). | ~180 (approx.; ~3 min per fixture-loading step) | 0 (eliminated by redesign) | Baseline screw fastening was removed by the redesigned securing method. |

| E4 | Connect/disconnect necessary interfaces (e.g., connectors, clamps) (from first connection action to ready-to-run state). | 347 ± 46 (275–430) | 113 ± 17 (85–150) | Reduced by improved access, fewer touchpoints, and standardized routing. |

| E5 | Start/confirm calibration run (from initiating the run to confirmed stable run condition). | 224 ± 37 (170–305) | 76 ± 13 (55–105) | Reduced by a simplified start sequence and fewer restarts. |

| E6 | Machine-controlled calibration dwell time (from stable run confirmation to end-of-run signal). | 1978 ± 235 (1610–2555) | 406 ± 72 (290–525) | May change due to batching/parallel runs and reduced waiting/idle time. |

| E7 | Unload units from fixture(s) (from opening/unlocking access to units cleared from fixture). | 389 ± 62 (295–535) | 137 ± 22 (102–185) | Reduced by improved fixture handling and reduced ergonomic strain. |

| E8 | Transfer and place calibrated units to the next internal container/stage (from first lift to units safely staged). | 271 ± 41 (205–360) | 69 ± 12 (48–92) | Reduced by batch transfer and shorter walking/handling distance. |

| E9 | Walking/handling between workstation, cart, and adjacent staging within the cell (from start of walking to return). | 117 ± 19 (85–165) | 52 ± 10 (35–72) | Reduced by workstation layout change and material handling redesign. |

| TOTAL | Total cycle time (sum of elements E1–E9). | 4475 | 1230 | Total reduction reflects combined effects of task consolidation, handling redesign, and process standardization. |

References

- Tech Briefs Media Group. IMU Contributions to Navigation and Safety for ADAS and Autonomous Vehicles. 2020. Available online: https://www.techbriefs.com/component/content/article/36151-imu-contributions-to-navigation-and-safety-for-adas-and-autonomous-vehicles (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Bajpai, A. Revolutionizing Automotive Technology: AI-Powered Calibration. 2024. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/revolutionizing-automotive-technology-precision-through-bajpai-uljlc (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Automotive Technology. Automotive Testing and Calibration Essentials. 2021. Available online: https://www.automotive-technology.com/articles/revolutionize-your-vehicles-automotive-testing-and-calibration-essentials (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Mobile2B. Optimizing Process Planning in Automotive Manufacturing. 2022. Available online: https://www.mobile2b.com/blog/process-planning-automotive-manufacturing-industry (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Miqueo, A.; Torralba, M.; Yagüe-Fabra, J.A. Lean Manual Assembly 4.0: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deron, A.; Rooda, J. Equipment Effectiveness: OEE Revisited. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2005, 18, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüttimann, B.G.; Stöckli, M.T. Going Beyond Triviality: The Toyota Production System—Lean Manufacturing Beyond Muda and Kaizen. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2016, 9, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Continental Engineering Services. Airbag Control Unit T25. 2023. Available online: https://conti-engineering.com/components/airbag-control-unit-t25/ (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- DENSO Corporation. Safety & Cockpit Systems. 2023. Available online: https://www.denso.com/global/home/business/products-and-services/mobility/safety-cockpit/ (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Bosch Mobility. Occupant Protection Systems. 2023. Available online: https://www.bosch-mobility.com/en/company/search-results?q=occupant%20protection&lang=en&scenario=1 (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Lean Production. Single-Minute Exchange of Die (SMED). 2020. Available online: https://www.leanproduction.com/smed/ (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Boysen, N.; Schulze, P.; Scholl, A. Assembly Line Balancing: What Happened in the Last Fifteen Years? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 301, 797–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortada, A.; Soulhi, A. Improvement of Assembly Line Efficiency by Using Lean Manufacturing Tools and Line Balancing Techniques. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2023, 17, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlik, E.; Ijomah, W.; Corney, J. Current State and Future Perspective Research on Lean Remanufacturing—Focusing on the Automotive Industry. IFIP Adv. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2013, 397, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, W.J.; Spearman, M.L. Factory Physics, 3rd ed.; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2011; p. 720. ISBN 978-1577667391. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, R.; Sheridan, T.B.; Wickens, C.D. A Model for Types and Levels of Human Interaction with Automation. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 2000, 30, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldratt, E.M. The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement, 3rd ed.; North River Press: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolini, M.; Faccio, M.; Gamberi, M.; Pilati, F. Motion Analysis System (MAS) for production and ergonomics assessment in the manufacturing processes. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 139, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, V.R. Measurement Uncertainty of Liquid Chromatographic Analyses Visualized by Ishikawa Diagrams. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2003, 41, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J.A.; Caldwell, J.L.; Thompson, L.A.; Lieberman, H.R. Fatigue and its management in the workplace. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 96, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Realyvásquez-Vargas, A.; Arredondo-Soto, K.C.; Blanco-Fernandez, J.; Sandoval-Quintanilla, J.D.; Jiménez-Macías, E.; García-Alcaraz, J.L. Work Standardization and Anthropometric Workstation Design as an Integrated Approach to Sustainable Workplaces in the Manufacturing Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, R.S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Singh, S.; Sachdeva, A. Productivity gains through standardization-of-work in a manufacturing company. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanawaty, G. Introduction to Work Study; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, T. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, W.P.; Dul, J. Human factors: Spanning the gap between OM and HRM. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2010, 30, 923–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikdar, A.A.; Al-Hadhrami, M.A. Operator Performance and Satisfaction in an Ergonomically Designed Assembly Workstation. J. Eng. Res. 2005, 2, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, M.; Ramos, A.L.; Carneiro, P.; Gonçalves, M.A. Integration of lean manufacturing and ergonomics in a metallurgical industry. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Saf. 2018, 2, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketokivi, M.; Choi, T. Renaissance of Case Research as a Scientific Method. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, C.; Tsikriktsis, N.; Frohlich, M. Case Research in Operations Management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, J. Building Operations Management Theory Through Case and Field Research. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.-L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphyllou, E. Multi-Criteria Decision Making Methods: A Comparative Study; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, V.; Stewart, T.J. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: An Integrated Approach; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liker, J.K. The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, J. How to Optimize Your Automotive Manufacturing Process. Katana. 2024. Available online: https://katanamrp.com/blog/automotive-manufacturing-process/ (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Abdulmalek, F.A.; Rajgopal, J. Analyzing the benefits of lean manufacturig and value stream mapping via simulation: A process sector case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2007, 107, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebel, B.W.; Freivalds, A. Methods, Standards, and Work Design, 12th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.