Abstract

Current research on automotive supply networks predominantly examines single-type entities connected through one relationship type, resulting in oversimplified, single-layer network structures. This conventional approach fails to capture the complex interdependencies that exist among mineral resources, intermediate components, and finished products throughout the automotive industry. To overcome these analytical limitations, this study implements a multilayer network framework for examining global automotive supply chains spanning 2017 to 2023. The research particularly emphasizes the identification of critical risk sources through both static and dynamic analytical perspectives. The static analysis employs multilayer degree and strength centralities to illuminate the pivotal roles that countries such as China, the United States, and Germany play within these multilayer automotive supply networks. Conversely, the dynamic risk propagation model uncovers significant cascade effects; a disruption in a major upstream supplier can propagate through intermediary layers, ultimately impacting over 85% of countries in the finished automotive layer within a short temporal threshold. Furthermore, this study investigates how individual nations’ anti-risk capabilities influence the overall resilience of multilayer automotive supply networks. These insights offer valuable guidance for policymakers, enabling strategic topological modifications during disruption events and enhanced protection of the most vulnerable risk sources.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the automotive industry has undergone a paradigm shift that is transforming its entire supply chain. This transformation has the potential to redefine sector boundaries, alter the roles of key players and their sourcing practices, and shift the competitive advantages of countries and regions—ultimately reshaping established industrial geographies. Specifically, the automotive industry faced significant challenges in 2022 due to the cessation of stimulus payments in the United States and European Union, rising inflation, and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. These pressures were compounded in 2023 when geopolitical tensions led to a decline in automotive trade between the United States and China [1]. Another notable change in automotive industry has been the rapid adoption of electric vehicles, driven by increasingly stringent CO2 emissions targets [2]. This trend became especially prominent in 2020, as major automotive manufacturers announced substantial investments in electric vehicles following the reopening after COVID-19-related closures, marking a shift away from internal combustion engine vehicles. These interconnected factors have significantly disrupted global automotive industry.

An automotive supply network structure refers to the connectivity patterns among suppliers within these networks [3]. Nonetheless, there is a scarcity of research that explores automotive-related products through the lens of supply networks. Relevant research includes analyses of the copper supply network [4,5,6], aluminum supply network [7], iron supply network [8], and automotive components supply networks [9], as well as broader examinations of automotive supply networks [1]. Traditional single-layer network analyses often fail to capture the multidimensional nature of real-world systems, leading to significant oversimplification. For instance, a supply chain may appear robust in a single-layer topology analysis, but simultaneous disruptions across the financial, informational, and physical layers can trigger cascading failures not predicted by any one layer alone. These quantified limitations demonstrate that single-layer models systematically distort critical assessments of vulnerability, efficiency, and resilience.

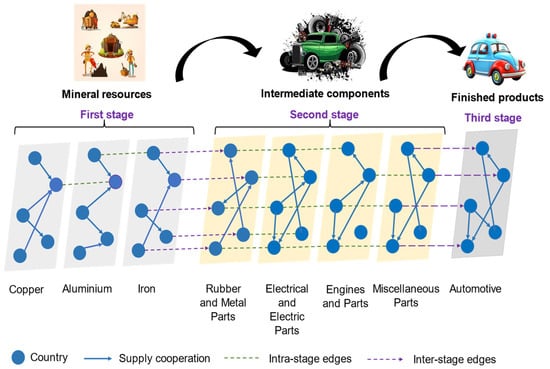

Figure 1 depicts the multilayer automotive supply network, emphasizing the necessity for additional research because of the uneven distribution of raw materials and the collaborative production efforts across nations within the automotive industry. While this visualization underscores the necessity for a multilayer perspective, it also reveals a critical gap: the complex, non-linear interdependencies between upstream component suppliers and downstream vehicle assemblers remain qualitatively depicted but quantitatively underexplored. Specifically, the model lacks the granularity to simulate how a disruption in a foundational material layer propagates through intermediate part and module layers, ultimately impacting final assembly resilience and cost. Our analysis addresses this gap by developing a dynamic, multi-commodity model to quantify these cross-layer dependencies, moving beyond topological description to predictive simulation.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the multilayer automotive supply networks.

Due to globalization and a continual pursuit of efficiency, multilayer automotive supply networks have grown increasingly interdependent. This interdependence is fundamental to understanding the business disruptions caused by recent natural and human-made disasters, such as the conflict between Russia and Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic [1,10]. Within these multilayer networks, a disruption originating from a single country or geographic area can propagate, impacting numerous other nations and locations. This phenomenon occurs because disturbances in one layer can trigger disruptions in dependent countries across other layers, leading to a cascading effect throughout the supply network [11]. The overall vulnerability of multiple stages in the supply network is significantly greater than that of isolated steps [2]. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate how this interdependence influences both the structural and functional behavior of multilayer automotive supply networks in the context of disruption risk propagation. Although various types of disruptions can impact these networks, this paper specifically examines node disruptions—instances where a node is unable to produce, shipment, or transfer products or services, resulting in a shock within the multilayer automotive supply networks.

To address these issues, we propose a methodology that visualizes and elucidates the structure of multilayer automotive supply networks while assessing potential risk sources associated with disruptions. Our study focuses on three primary objectives. First, we present an analytical framework employing a multilayer network model to illustrate collaborative relationships among nations for each commodity within multilayer automotive supply networks, including direct supply connections between upstream and downstream automotive-related products. This framework encompasses critical mineral layers, semifinished product layers, and automotive layer supply networks. Second, we identify key risk sources through static centrality measures, employing multilayer degree and strength centralities while considering each country’s multilayer structure. Additionally, we analyze shifts in countries’ relative positions based on their specializations in multilateral transactions. Third, we implement a risk propagation model to reveal hidden risk factors within multilayer automotive supply networks. We analyze two real-world disruption scenarios: restrictions on specific commodities and blocked export routes. Through dynamic analysis, we reveal hidden dependencies among countries regarding each commodity and direct supply links between upstream and downstream automotive-related products.

This paper is organized in the following manner. In Section 2, we review existing literature on automotive supply networks, emphasizing key findings thus far and identifying the gaps our analysis aims to address. Section 3 outlines the sources of data and the methodologies employed. The results of the static analytical model, including the topological relationships within multilayer supply networks and their centrality, are presented in Section 4. In Section 5, we discuss the findings related to risk propagation in both single-layer and multilayer automotive supply networks. Section 6 provides a discussion of these results. Finally, Section 7 offers conclusions and suggests potential avenues for future research emerging from this study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Automotive Supply Networks

The automotive manufacturing supply network has significantly expanded in scale and has become increasingly intricate [12,13]. Research on automotive supply networks has evolved across two primary levels of analysis: firm-level inter-organizational relationships and country-level international trade patterns. At the firm level, studies reveal these networks often exhibit exponential degree distributions rather than pure scale-free properties, making them more resilient to targeted attacks on hubs than scale-free networks, yet more vulnerable than random networks [14]. Spatially, manufacturers demonstrate distinct clustering patterns around geographically proximate suppliers, forming robust regional ecosystems [1,15]. Over recent decades, the global automotive supply network has evolved to become denser, broader, and more integrated, characterized by a center-periphery structure where regional clusters hold significant importance [15]. A notable topological feature is the isolated community formed by Chinese firms, largely attributable to domestic protectionist policies [1].

At the country level, analysis of global trade networks reveals dynamic structural shifts [16,17]. The trade barycenter (center of trade gravity) has shifted from Asia to Europe, indicating a significant restructuring of global supply chain geography [18]. While the prominence of primary clusters and individual nations fluctuates, interconnections between these clusters are strengthening over time [9]. Recent research by Smith and Sarabi (2021) identifies a high degree of integration with Europe and Central Asia, alongside emerging trends of sourcing inputs from East Asia and the Pacific, with the Middle East and North Africa becoming key export destinations [19]. Table 1 presents a systematic synthesis of empirical studies examining automotive supply network topology, highlighting the evolution of analytical approaches across different network levels and time periods.

Table 1.

Empirical studies on the topological structure of global automotive supply networks.

However, the majority of existing research, as summarized in Table 1, focuses on single-layer network representations, connecting entities through singular relationship types [24]. While these studies provide valuable insights into specific aspects, this approach offers a fragmented perspective on automotive supply systems that inherently involve multiple, simultaneous relationship types among their components. This oversimplification can lead to misleading conclusions about network resilience and functionality. The emerging multilayer network paradigm offers a more sophisticated framework that explicitly incorporates multiplexity, enabling the integration of different structural relationships and the synchronization of various dynamic processes across interconnected frameworks.

2.2. Risk Analysis of Supply Networks

A range of both foreseeable and unexpected events, such as natural disasters, human-induced crises, and internal failures, have persistently posed threats to the profitability and stability of supply networks, particularly at a global scale [27]. Risks like inadequate supplier performance, misrepresentation of supplier capabilities, and conflicting objectives can lead to considerable disruptions in supply and inventory, along with issues related to quality and performance [28]. The impact and origins of disruptions within automotive supply networks have been revealed following the onset of COVID-19 in 2020 [29,30].

Supply network risk analysis employs two complementary methodological approaches: static risk indicators and dynamic propagation models. Static approaches evaluate network resilience by examining vulnerabilities at individual nodes through random failures or targeted attacks. These methods utilize metrics like degree distributions [31], path lengths, clustering coefficients [32,33], and centrality measures (degree, betweenness, closeness) to identify bottlenecks and assess disruption risks [34,35,36]. While useful for mapping initial vulnerability, a fundamental limitation is their inability to model how a disruption, once initiated, propagates through the network’s connectivity [30,37,38].

Dynamic risk propagation models address this critical gap by simulating how disruptions spread via network connections [39]. Cascading failure frameworks, often employing linear threshold models, typically represent nodes in binary states (operational/disrupted), with propagation occurring when risk transmission exceeds critical thresholds [37,40,41]. A key finding across these studies is that the indirect impacts of disasters through propagation can be substantially greater than direct effects [42], and overlooking this ripple effect leads to a significant underestimation of systemic risk [43,44].

Extensive research confirms that network topology is a primary determinant of risk propagation patterns [45]. Structural characteristics strongly correlate with propagation speed, extent, and overall network resilience [46,47]. However, the relationship involves critical trade-offs. For instance, while scale-free networks exhibit robustness to random failures [3,48], their hub-and-spoke structure can accelerate risk propagation if a central hub is compromised [46]. Similarly, high internal connectivity within modules can facilitate cascading disruptions [44], while smaller, more isolated groups may exhibit greater resilience to external shocks [47]. These insights underscore that a holistic understanding of disruption risk requires integrating both static topological analysis and dynamic behavioral modeling.

2.3. Research Gap and Contributions

Despite substantial progress, critical gaps persist in the literature on automotive supply chain risk.

First, while existing studies provide valuable insights within single-layer contexts, there is a scarcity of research investigating the multilayer structure of the complete global automotive supply network. This limits a comprehensive understanding of both static architectural characteristics and dynamic risk propagation processes in multiplex environments. Therefore, we pose research question 1 (RQ1): How can the global automotive supply network be modeled and analyzed as a multilayer system to capture its full structural complexity and dynamic behavior?

Second, current approaches predominantly evaluate node importance based on aggregate trade volumes or single-layer structural properties. This overlooks the multidimensional nature of systemic significance, which encompasses the strategic roles of trading partners and complex interdependencies spanning upstream and downstream layers. This leads to research question 2 (RQ2): In a multilayer supply network, how can we comprehensively quantify a country’s systemic importance to identify critical risk hubs that may be overlooked in single-layer or aggregated analyses?

Third, existing disruption risk propagation models focus predominantly on single-layer networks. While the simultaneity of risks in complex systems is acknowledged, current modeling approaches often consider commodities in isolation, neglecting the transformational relationships and cross-layer dependency pathways that define integrated supply networks. Consequently, we ask research question 3 (RQ3): How do disruptions propagate across different commodity layers, and which cross-layer pathways are primary amplifiers of systemic risk?

To address these questions, this study makes the following contributions:

We propose an analytical framework based on multilayer network theory to model the global automotive supply chain across eight commodity layers, explicitly representing direct supply connections from raw materials to finished vehicles.

From a static perspective, we analyze systemic risk using multilayer degree and strength centralities, providing a holistic assessment of country importance that incorporates trade volumes, partner influence, and cross-layer positioning.

From a dynamic perspective, we develop novel disruption risk propagation models to simulate cascading failures under realistic scenarios, quantifying risk transmission pathways and revealing hidden vulnerabilities that remain invisible to single-layer analysis.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data and Network Construction

The multilayer automotive supply networks encompass numerous commodities across diverse production stages. Due to the intricate interdependencies between upstream and downstream commodities and the limitations of publicly available trade datasets, this study focuses on eight representative commodity categories that capture the essential structure of these complex networks. This categorization is not arbitrary but is derived from a principled, two-stage methodology to ensure both theoretical validity and analytical tractability. First, the full spectrum of automotive-related commodities in the UN Comtrade database, classified under the Harmonized System (HS), was mapped onto the production stages defined by the OECD’s Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) tables for the transport equipment sector. This mapping identified fundamental, non-substitutable inputs spanning the entire value chain. Second, an aggregation and filtering analysis was applied. Commodity groups were consolidated to achieve a balance between granularity and model parsimony, ensuring each resultant layer represented a critical, functionally distinct node in the production pathway—from primary mineral resources (L1: Copper; L2: Aluminum; L3: Iron & Steel) to intermediate components (L4: Rubber & Plastics; L5: Fabricated Metal Parts; L6: Electrical & Electronic Components; L7: Engines & Powertrain) and the final output (L8: Finished Automobiles). A final selection filter required each candidate layer to exhibit sufficient network density and significant annual trade volume to support robust statistical analysis of inter-layer dynamics. Consequently, layers L1-L8 collectively provide a validated, simplified-yet-comprehensive topology of the global automotive supply network, enabling the investigation of cross-layer dependencies that are obscured in single-commodity or aggregated models.

The foundational raw material inputs are represented by highly concentrated layers: L1 (Copper) corresponds solely to HS Code 2603 (Copper ores and concentrates), L2 (Aluminum) to HS Code 2606 (Aluminium ores and concentrates), and L3 (Iron) to HS Code 2601 (Iron ores and concentrates). This precise representation at the ore level is deliberate, as it captures the geographically concentrated extraction phase. The intermediate production stages are modeled through four layers composed of more diverse SITC code aggregates. L4 (Rubber and Metal Parts) encompasses SITC codes pertaining to tires, inner tubes, and specific metal mountings and fittings (e.g., 6251, 62591, 69915), grouping complementary sub-assemblies supplied to integrators. L5 (Electrical and Electric Parts) aggregates codes for key electronic components and lighting systems (76211, 76212, 77812, 77823). L6 (Engines and Parts) is constructed from codes representing internal combustion engines and their associated electrical ignition and lighting equipment (71321–71323, 77831–77834). L7 (Miscellaneous Parts) serves as a broader category for essential chassis, body, braking, and transmission components not captured in the preceding layers (7841, 78421–78439, 82112). Finally, L8 (Finished Automotive Products) represents the terminal output of the chain, comprising HS codes for complete vehicles (8702, 8703, 8704). The complete, code-level definition for each layer is meticulously documented in Appendix A, Table A1, which provides the full description and code list for replication.

The raw trade data were subject to common reporting issues, including missing values and asymmetries between partner records. To handle the latter, we reconciled discrepant import and export reports by calculating their arithmetic mean, establishing a single, consistent value for each bilateral trade flow.

Multilayer automotive supply networks consist of eight layers. The single-layer supply networks are constructed as , where is the set of nations in layer . indicates a specific year ranging from 2017 to 2023 and . Additionally, the set of edges is represented as , where indicates that country exported commodities to country in the layer in year . The matrix of trade dependency is indicated by , where is the aggregate export trade dependency value of commodities from country to country in the layer in year .

According to the definitions provided for these eight single layer networks, the multilayer automotive supply networks are denoted as , where represents the collection of single-layer supply networks, and refers to the collection of connections between identical nodes across various single-layer supply networks. This is referred to as the cross layer.

3.2. Static Structure Metrics of Global Automotive Supply Networks

In a single-layer supply network, the structural measures are presented in Appendix B. In multilayer supply networks, we establish an overlap ratio between nodes and edges across pairs of single-layer supply networks to evaluate the multifaceted roles of individual countries within the global supply chain. Subsequently, we employ the Pearson correlation coefficient, following the methodology proposed by [49], to analyze inter-layer relationships among different commodities within these supply networks. Finally, the shortest-path distance between nodes is used to assess the similarity of routes across layers based on their minimum path distances.

The total overlap of nodes and edges represents the percentage of shared nodes and edges between two network layers. The calculation method for determining this overlap is outlined below:

where and indicate the set of nodes and edges, respectively, in the supply network layer. and represent the set of nodes and edges in the supply network, respectively. The overlap of nodes and edges in multilayer automotive supply networks is defined as and , respectively. The degree of overlap between nodes and edges ranges from 0 to 1. Higher overlap values indicate greater structural similarity between supply networks, demonstrating stronger correlation between the two individual networks.

Assortativity quantifies the tendency of a network’s nodes to connect with other nodes that share similar characteristics. Inter-layer assortativity assesses how nodes with specific degrees in one layer are linked to nodes with comparable degrees in other layers. This metric reflects the correlation between node degrees across different layers of the multilayer network. The formula for the Pearson correlation coefficient is expressed as follows:

where and indicate the degree vector of layer and , respectively. and represent the standard deviation of vector and , respectively. This coefficient ranges from −1, indicating fully disassortative mixing, to +1, which represents fully assortative mixing. Two layers are considered assortative (or disassortative) in their interlayer correlations if they exhibit a positive (or negative) correlation.

Inter-layer similarity, defined by the shortest-path distance between nodes, evaluates the similarity of routes across various layers according to their minimum path distances. If the entries of represent the shortest path distances between any two nodes in layers , and , the measure is articulated as follows:

The centrality analysis of the multilayer supply network employs degree centrality and strength centrality as its primary diagnostic metrics. This focused selection is not an omission but a targeted strategy justified by the distinct physical and economic logic of supply chains and the specific vulnerability profile we seek to illuminate.

Supply network risk, particularly concerning resilience to disruptions, is first-order a problem of direct exposure and dependency concentration. Degree centrality—specifically in-degree in our directed network—provides the most fundamental measure of exposure by enumerating a node’s number of direct suppliers. A country with low in-degree is operationally vulnerable; the failure of even one of its few suppliers can cause an immediate bottleneck. This metric directly maps to the strategic imperative of supplier diversification.

However, degree alone is insufficient, as it treats all connections equally. Strength centrality addresses this by incorporating trade flow volumes. A node may have multiple suppliers (high in-degree) but source 90% of a critical component from a single partner. Its risk profile is defined by this concentrated dependency, not by the count of minor alternative sources. Strength centrality quantifies this volume concentration risk, identifying nodes whose operation is critically reliant on the integrity of a single, high-capacity link.

3.3. Risk Propagation of Single Layer Automotive Supply Networks

This subsection introduces dynamic risk propagation models aimed at detailing the risk propagation pathways and identifying critical risk sources within single-layer supply networks. For such networks, the risk propagation model specifically addresses supply limitations related to a particular commodity. In earlier research, Yue et al. (2023) [40] developed a risk propagation model based on a linear threshold approach to illustrate how risks spread throughout global supply networks. This current study employs the aforementioned model to evaluate the risks arising from supply restrictions on a specific commodity across various countries.

In the single-layer supply network for layer in year , a country faces a supply shortfall. Nodes can exist in two conditions: normal and disrupted. At the outset, seed node has original demands represented by and supplies denoted by . In step , seed country reduces its material supply and is considered to be in a disrupted state due to catastrophic events. Consequently, the supply constraint risk from country will extend to downstream countries via its material flows. The supply reduction ratio ranges from 0 to 1. The decrease in supply is , and the revised supplies are . For downstream country with , the material flow from to is modified to , where represents the initial weight of the directed edge from node to node in layer . The decrease in material supply from country correlates with the weight between countries and . If this supply reduction exceeds the anti-risk capacity , designated as , country will shift from a normal state to a disrupted one. When country experiences disruption, its material supply diminishes, leading to a continuous spread of risk to downstream nations. This risk propagation continues through single-layer supply networks until no further supply disruptions can occur. The proposed risk propagation model determines both the number of disrupted nodes and the iteration count for each specific seed node across all layer networks.

3.4. Risk Propagation of Multilayer Automotive Supply Networks

In multilayer automotive supply networks, disruption risk propagation models are developed for two realistic scenarios: (1) restrictions on the supply of specific commodities and (2) blocked export channels. Scenario 1 examines supply restrictions on particular commodities within a given country. As illustrated in Figure 2, when nodes are disrupted in a single-layer supply network during the initial stage, corresponding nodes in subsequent single-layer supply networks become affected through cascading effects. Within these multilayer automotive supply networks, the single-layer supply networks for mineral resources, such as copper , aluminum , and iron , serve as upstream components for the intermediate networks supplying rubber and metal parts , electrical and electronic parts , engines and parts , as well as miscellaneous parts . Finally, automotive supply network operates downstream from the intermediate component supply networks.

Figure 2.

Risk propagation in multilayer automotive supply networks.

In the risk propagation model for multilayer automotive supply networks, supply restrictions from a specific commodity supply network , initiated by seed node , first affect the single-layer supply network as explained in Section 3.3. Subsequently, the disrupted nodes in , referred to as node set , will cause the same nodes to be impacted in , where represents the downstream network of . The total number of nodes in is . These disrupted nodes will transmit risks in . The collection of disrupted nodes in is identified as , and . The risk of disruption will continue to spread through in toward the downstream network . This cascading process demonstrates how a disruption in an upstream single-layer supply network (such as a mineral resource network) propagates risk across the entire multilayer automotive supply network, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Multilayer automotive supply networks exhibit nine risk propagation pathways: five three-layer cascades (L1 → L5 → L8, L2 → L6 → L8, L3 → L4 → L8, L3 → L6 → L8, L3 → L7 → L8) and four direct two-layer cascades (L4 → L8, L5 → L8, L6 → L8, L7 → L8). The disruption impact is quantified using an indicator that averages the ratio of affected-to-total nodes across all network layers within each propagation scenario, calculated under different threshold conditions.

Scenario 2 illustrates a severe situation where all commodities face supply restrictions in a particular country, resulting in completely blocked export channels. Unlike scenario 1, the supply restriction impacts from node in networks , , , and six additional single-layer networks occur simultaneously during the initial stage. Following this, the affected nodes in , specifically , cause disruptions in the same nodes within . Likewise, the affected nodes in also transmit disruption risks to . Importantly, the combined set of nodes affected in during the first stage, along with the nodes disrupted in due to and , collectively propagate disruption risks in , resulting in additional affected nodes . The disruptions in the single automotive supply network arise from the combined effects of nodes , , and being compromised. The influence of node on multilayer automotive supply networks is assessed by calculating the average ratio of affected nodes relative to the total number of nodes across these networks under all possible threshold settings within the eight single-layer supply networks. Within the context of this multilayer supply network, we define a hidden systemic risk as a vulnerability that meets two concurrent, quantitative criteria: (1) it has the potential for extensive nodal disruption, and (2) it manifests with accelerated propagation dynamics following an initial failure.

4. Static Analysis Results

This section presents the structural characteristics of the multilayer automotive supply network, with all findings derived directly from the processed UN Comtrade data for the eight defined commodity layers (L1–L8) from 2017 to 2023. The results are presented to answer specific research questions about the structure of single-layer supply network, Topological correlation between multilayer automotive supply networks, and Centrality of multilayer automotive supply networks.

4.1. Structure of Single-Layer Supply Network

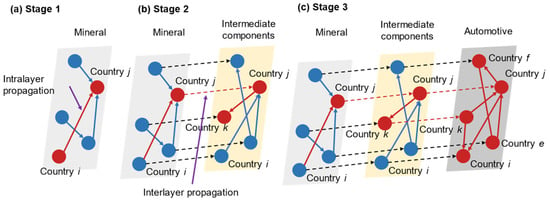

The total number of countries involved and their cooperative relationships reflect the size of the global supply network. Figure 3 illustrates the scale of the single-layer supply network, highlighting an upward trend in both the global rubber and metal components layer as well as the electrical and electronic parts layer. Notably, the relevant industries have experienced a swift rise in the number of participating countries, significant growth in established trade relationships, and increased density. As depicted in Figure 3a, the quantity of countries within the intermediate components and automotive layers is comparable; however, it surpasses that of the mineral resource layers. Nonetheless, there are clear differences in the engagement levels of the same countries across these layers. These differences are specifically demonstrated by the variations in the number of cooperative relationships and the density within each layer, as shown in Figure 3b,c. Over the research period, the layers ranked by the highest number of cooperative relationships and density are the miscellaneous parts layer, followed by the engines and parts layer, and then the automotive layer. Furthermore, the miscellaneous parts layer exhibits the highest network density, suggesting that these parts are extensively utilized globally. Conversely, the aluminium layer shows the lowest network density, likely due to the geographical concentration of aluminium resources primarily in Bauxite, with many consuming nations importing large amounts of aluminium and its products to satisfy domestic needs [7].

Figure 3.

Basic structural characteristics of the single-layer supply networks. (a) number of nodes; (b) number of edges; (c) density; (d) components; (e) diameter; (f) average path length.

The components illustrate the overall interconnectedness of the network. A lower value suggests that countries are likely to form close trade clusters. As shown in Figure 3d, the components within the mineral resource layers are considerably greater than those in the intermediate components and automotive layers, indicating that the latter two are more interconnected than the mineral resources. This suggests significant potential for growth in mineral resource trade when compared to the more established global markets for intermediate components and automotive products.

Figure 3e,f demonstrates a downward trend, indicating that pairs of countries within each layer can form trade relationships with fewer intermediary nations or may engage directly. The reduction in average path length is linked to the globalization of trade and the increasing prevalence of bilateral and multilateral trade agreements [50]. However, in 2023, the copper supply network layer shows a longer average path length, and its decrease is less significant compared to the other seven layers. This suggests that global trade cooperation in the copper sector is not keeping pace with advancements observed in the other layers. A noteworthy point is the substantial decrease in network diameter observed in 2021, which may be interpreted as evidence of a rebound in automotive markets following the COVID-19 pandemic, with cooperative relationships likely becoming more direct and efficient.

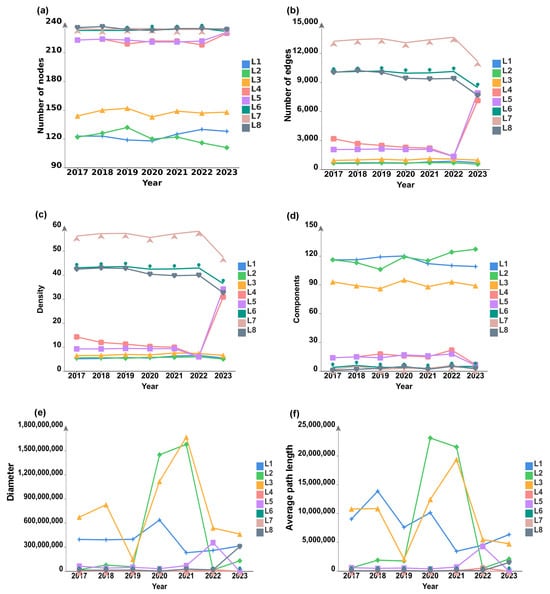

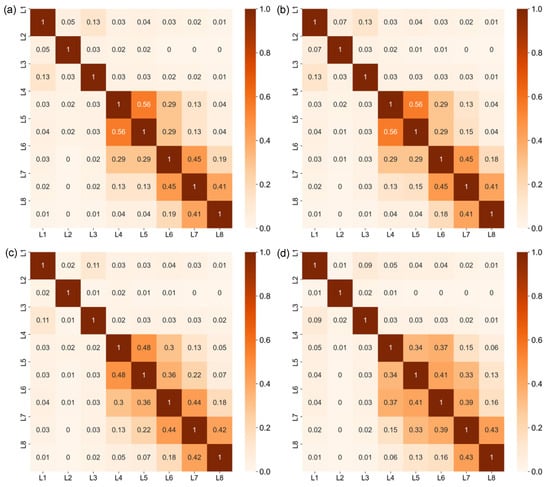

4.2. Topological Correlation Between Multilayer Automotive Supply Networks

Grasping the concept of node overlap is essential for understanding how interconnected or influential various entities are within the multilayer automotive supply networks. As illustrated in Figure 4, the average node overlap between mineral and other commodity supply networks remains below 0.6 from 2017 to 2023. This low level of overlap is largely due to the high concentration of the mineral market. For example, China leads globally in trade volumes related to mining, selection, smelting, copper processing, and waste management, and it sources from the largest number of countries across the entire industrial chain [51].

Figure 4.

Mean node overlapping of multilayer automotive supply networks in 2017 (a), 2019 (b), 2021 (c), and 2023 (d).

Furthermore, the average node overlap among rubber and metal parts, electrical and electronic components, engines and associated parts, miscellaneous parts, and automotive supply networks exceeds 0.9. This finding indicates that most countries trading in rubber and metal parts, electrical and electronic components, engines, and miscellaneous automotive items are also active participants in the broader automotive supply chain. Additionally, the number of countries overlapping between intermediate components and automotive layers has shown an upward trend; specifically, the mean overlap ratio between electrical and electronic components and automotive supply networks rose slightly from 0.94 in 2017 to a peak of 0.98 in 2023. This indicates that nodes within the electrical and electronic parts supply network are increasingly involved in the automotive supply network, reflecting a consistent and gradual strengthening of the relationship between these two supply networks.

Multilayer automotive supply networks exhibit considerable overlap in connections when a finite number of node pairs are linked across various layers. As depicted in Figure 5, the average edge overlap between the mineral layer and other layers is notably low. This reduced link overlap primarily results from the significant differences in the number of collaborative connections. In contrast to the mineral layers, adjacent supply networks of intermediate components and finished products tend to have a relatively high average edge overlap. For example, cooperation among different countries across various products—such as rubber and metal parts, electrical and electronic parts, engines and related parts, miscellaneous parts, and automotive—indicates a substantial overlap across these five layers. This occurs because the production of automotive vehicles in any country typically requires inputs from many other commodities. For instance, an automotive unit relies not only on rubber and metal parts but also on electrical and electronic parts, engines and parts, along with miscellaneous parts. Furthermore, in 2023, the highest average edge overlap was observed between the miscellaneous parts layer and the automotive layer. The key takeaway is that if a connection in the miscellaneous parts layer frequently correlates with a connection in the automotive layer, this relationship can be utilized to predict the likelihood of an edge appearing in the automotive layer, with its value reflecting the strength of that association.

Figure 5.

Mean edge overlapping of multilayer automotive supply networks in 2017 (a), 2019 (b), 2021 (c), and 2023 (d).

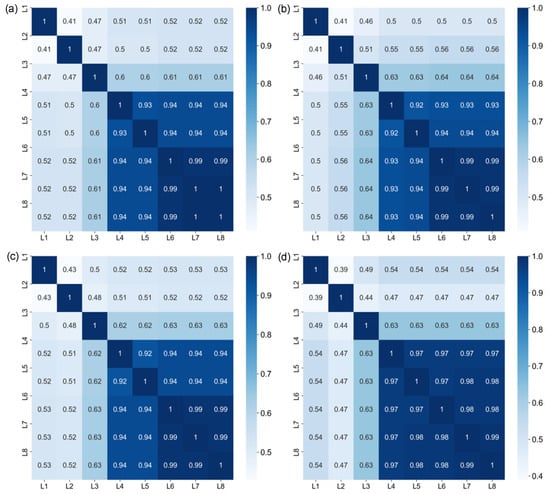

Figure 6 illustrates a notably low level of correlation between mineral layers and other layers, indicating that these layers exert limited influence on one another. While this low correlation between mineral layers and others is somewhat anticipated, it is noteworthy that the interlayer similarity among the supply networks of copper, aluminum, and iron exceeds 0.4. There exists a significant network of cooperative relationships among these mineral resources. Furthermore, the layers associated with rubber and metal parts, as well as electrical and electronic parts, engines and related parts, miscellaneous parts, and automotive products exhibit considerable inter-layer similarity, with their proportions being quite substantial. This phenomenon arises because these commodities are interconnected through shared resources and possess distinct characteristics. Additionally, the inter-layer similarity matrices show minimal changes from 2017 to 2023, suggesting a lack of significant local structural adjustments.

Figure 6.

Inter-layer similarity of multilayer automotive supply networks in 2017 (a), 2019 (b), 2021 (c), and 2023 (d).

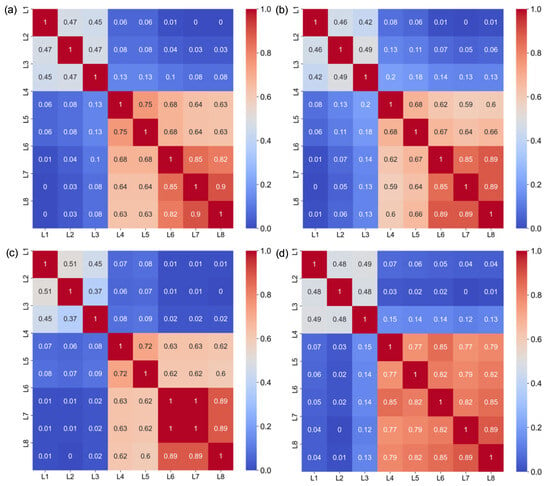

As depicted in Figure 7, the multilayer automotive supply networks exhibit positive assortativity coefficients. This finding suggests that these networks demonstrate a rich-club effect, characterized by the tendency for highly central nodes to connect with one another. Additionally, the highest degree of assortativity is observed among the layers dealing with rubber and metal parts, electrical and electronic parts, engines and related parts, miscellaneous parts, and automotive supply networks. For instance, the notably high assortativity between the rubber and metal parts layer and the electrical and electronic parts layer implies that countries with a significantly elevated average degree in the rubber and metal parts supply network are likely to have a similarly high average degree in the electrical and electronic parts network. Moreover, the purple region in Figure 7 expands from 2017 to 2023, indicating an upward trend in inter-layer assortativity among the layers.

Figure 7.

Inter-layer assortativity of multilayer automotive supply networks in 2017 (a), 2019 (b), 2021 (c), and 2023 (d).

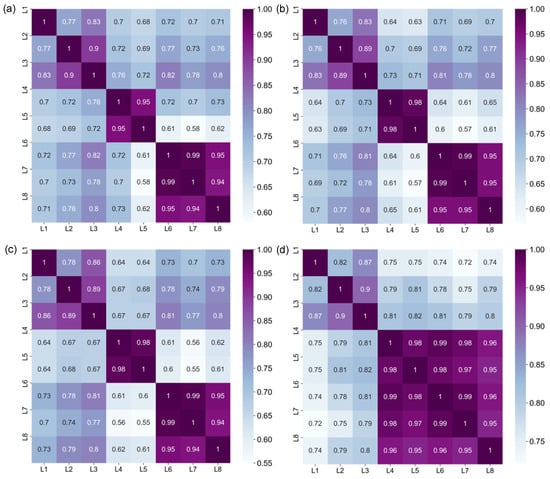

4.3. Centrality of Multilayer Automotive Supply Networks

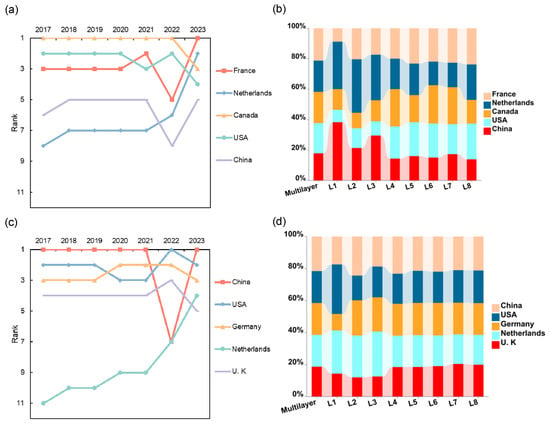

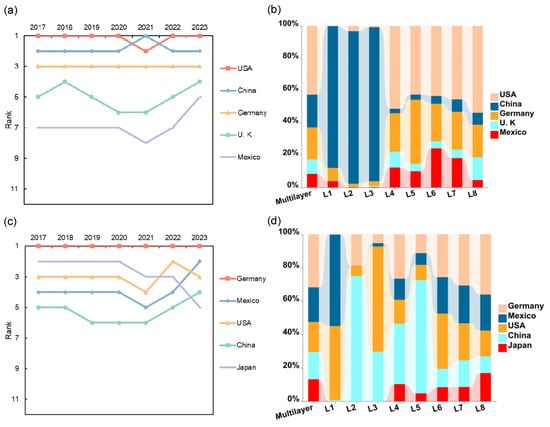

To effectively demonstrate the topological features of the networks and emphasize the significance of key import and export nations in the multilayer automotive supply networks, we present a bump chart showcasing the five countries that form the core of the multilayer automotive supply networks from 2017 to 2023, based on degree and strength centralities. The final list of countries is determined by their centrality rankings in 2023.

Figure 8a,b illustrates that the top five importers, identified by in-degree centrality within the multilayer automotive supply networks, are predominantly situated in Europe and America, mostly comprising industrialized nations. From 2017 to 2022, France, Canada, and the USA consistently ranked among the top five import partners, reflecting their substantial number of import connections in these networks. Since 2021, the Netherlands has experienced significant growth in its rankings, along with an increase in the variety of countries it imports from. Moreover, the data for each single-layer supply network in 2023, presented in the stacked histogram (Figure 8b), highlight the importance of these importers within each layer. The Netherlands and China have remained the primary sources of imports in the copper, aluminum, and iron supply networks. Many countries with central roles in the rubber and metal parts, as well as engines and parts supply networks, are located in America, including the USA and Canada. Additionally, the USA and France are pivotal in the electrical and electronic parts and automotive supply networks, while Canada and France hold central roles in the miscellaneous parts supply network.

Figure 8.

Changes in core countries with high in-degree and out-degree in the multilayer automotive supply networks.

Additionally, the most prominent nations regarding out-degree centrality within the multilayer automotive supply networks, as illustrated in Figure 8c,d, include China, the USA, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. These five countries are ranked at the top and possess the largest number of export partners. The principal exporters are primarily found in North America, Europe, and Asia, predominantly comprising industrialized nations. In 2023, China secured the leading position, exporting automotive products to a vast majority of countries around the globe. Since 2017, the Netherlands has seen substantial growth in both its rankings and the diversity of countries it exports to. Furthermore, the results for each individual layer of the supply networks in 2023, presented in the stacked histogram (Figure 8d), highlight the significance of these exporters within their respective layers. The Netherlands stands out in terms of export partners for copper, aluminum, and iron, followed at a distance by the USA, China, and Germany. Countries such as China and Germany exhibit clear advantages in the export channels for rubber and metal parts, as well as electrical components and engines. The USA and China also hold high out-degree positions in the miscellaneous parts and automotive supply networks.

As illustrated in Figure 9a, several countries in America—particularly the USA—have significantly contributed to multilayer automotive supply networks, especially those with high in-strength centrality. From 2017 to 2023, the USA consistently ranked first, with the exception of 2021. Over the past three years, both the United Kingdom and Mexico have improved their standings. Meanwhile, Germany has maintained a steady role as an import country, holding second place. Additionally, the findings for each individual layer of the supply networks in 2023, presented in the stacked histogram (Figure 9b), demonstrate the significance of these key importing nations within each layer. Notably, China plays a central role in the supply networks for copper, aluminum, and iron. The USA and Germany are pivotal in the networks for rubber and metal parts, electrical components, miscellaneous parts, and automotive supplies. Furthermore, the USA and Mexico hold central positions in the engines and parts supply network.

Figure 9.

Changes in core countries with high in-strength and out-strength in the multilayer automotive supply networks.

Regarding export countries with high out-strength centrality, a limited yet stable group of long-established industrialized nations is crucial in the multilayer automotive supply networks depicted in Figure 9c. For example, Germany consistently ranks as an exporting hub, while Japan and the USA exhibit considerable fluctuations in their dynamic rankings. Over the last seven years, both China and Mexico have seen remarkable improvements in their positions. The results for each single-layer supply network in 2023, also shown in the stacked histogram (Figure 9d), highlight the most significant exporting countries for each layer. The USA leads in export volumes for copper and iron, with Mexico and China following at a distance. In the supply networks for aluminum, as well as rubber and metal parts, China and Germany play key roles. Finally, Germany and the USA are essential in the networks for electrical components and engines and parts, while for miscellaneous parts and automotive supply networks, Germany and Mexico hold central positions.

5. Dynamic Analysis Results

This section presents the outcomes of the risk propagation simulations, which are based on the weighted, directed adjacency matrices of the eight supply networks in 2023 and the cascade model detailed in Section 3.3 and Section 3.4. The results quantify the systemic impact of disruptions originating from different countries and layers, moving beyond static topological analysis to reveal the dynamic behavior of the multilayer automotive supply network under disruption risks.

5.1. Risk Propagation in a Single-Layer Supply Network

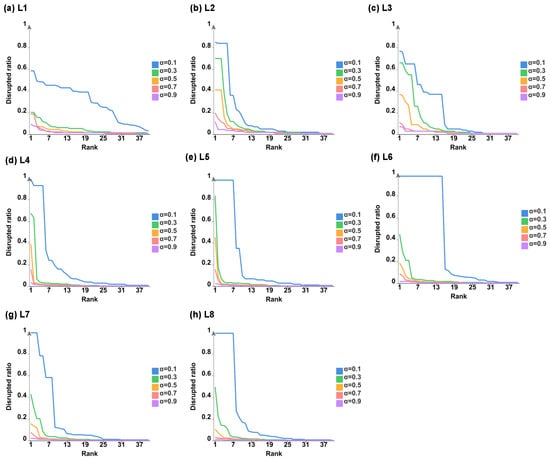

Table 2 identifies the five countries that most significantly impact single-layer supply networks when α is set to 0.1 and p equals 1. Figure 10 illustrates how supply constraints from different risk sources affect these networks. The analysis reveals distinct patterns based on resource type. For copper, aluminum, and iron supply networks, the countries with the greatest influence are those rich in the corresponding mineral resources, predominantly located in Africa and the Americas. These resource-abundant nations include Canada, Bolivia, Chile, Guyana, Brazil, and Mauritania. In contrast, supply networks for rubber and metal parts, electrical components, engines and parts, and miscellaneous automotive supplies are dominated by highly industrialized countries. Germany, the USA, Japan, and China emerge as the major players in these manufacturing-intensive sectors.

Table 2.

Top 5 countries in terms of disrupted ratios with α set to 0.1 and p set to 1.

Figure 10.

Impacts of supply restrictions in single-layer supply networks.

Figure 10 demonstrates that certain risk sources can disrupt operations in many countries. For instance, when the anti-risk capacity parameter is set at 0.1, over 50% of nations in the automotive supply network layer (L8) will experience disruptions due to the influences of the top five countries: China, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the USA. Moreover, the distribution of disrupted scales resulting from different sources is not uniform. Specifically, risk sources ranked below 11th are likely to cause disruptions in fewer than 10% of countries within the electrical and electric parts layer (L5) when the threshold is at 0.1. This research demonstrates that the vulnerability of the eight single-layer networks responds differently to various threshold parameter settings. Two distinct patterns emerge from the analysis. First, the disruption ratios for layers affected by the top five risk sources in aluminum and iron minerals demonstrate a gradual, consistent decrease across varying threshold parameters. This pattern indicates moderate sensitivity to threshold adjustments. Second, a markedly different pattern characterizes copper minerals, rubber and metal parts, electrical and electronic parts, engines and parts, miscellaneous parts, and automotive supplies. For these sectors, disruption ratios decline sharply as thresholds increase from 0.1 to 0.3, but then stabilize when thresholds rise further from 0.3 to 0.9. This biphasic response reveals heightened sensitivity to lower threshold values, with relative stability at higher thresholds.

The consistently high disruption ratios in the copper (L1), aluminum (L2), and iron (L3) layers, particularly at low anti-risk capacity thresholds (θ < 0.3), are primarily a function of extreme supplier concentration. These raw material markets are characterized by oligopolistic global supply, where a small number of countries dominate production and export. In network terms, this translates to very low in-degree (few suppliers) and high strength centrality (high dependency volume) for most importing nodes. For example, a disruption at a major mining hub like Chile for copper creates a supply shortfall with no immediate alternative source for many dependent countries, leading to rapid and widespread failure propagation. The gradual, consistent decrease in disruption ratios as the threshold (θ) increases from 0.1 to 0.9 indicates that these layers are moderately sensitive to improvements in risk capacity; enhancing resilience requires significant effort to overcome the inherent lack of diversification.

In contrast, the disruption ratios for layers L4 (rubber & metal parts) through L8 (finished automobiles) exhibit a biphasic response: a sharp decline as θ increases from 0.1 to 0.3, followed by stabilization at higher thresholds. This pattern is driven by two factors: inventory buffering capacity and product complexity/substitutability. The initial sharp decline occurs because many countries in these layers maintain safety stocks that can absorb short-term disruptions. Once these buffers are exceeded (at lower θ values), failures cascade quickly. The subsequent stabilization indicates that beyond a certain point, further improvements in individual node resilience yield diminishing returns because the disruptions have become systemic, constrained by the network’s core structure. The high density and interconnectedness of these layers facilitate both robust operation under normal conditions and rapid cascade propagation once critical thresholds are breached.

The findings suggest that enhancing risk management capabilities in countries with lower operational levels will yield greater improvements in supply network resilience for six specific sectors: copper minerals, rubber and metal components, electrical parts, engines and parts, miscellaneous parts, and automotive supplies. These sectors demonstrate higher sensitivity to risk management improvements compared to aluminum and iron mineral networks. Given this differential sensitivity, countries participating in the copper minerals, rubber and metal parts, electrical parts, engines and parts, miscellaneous parts, and automotive supply layers require prioritized attention for strengthening their risk mitigation strategies relative to participants in other supply network layers.

5.2. Risk Propagation in the Multilayer Supply Networks

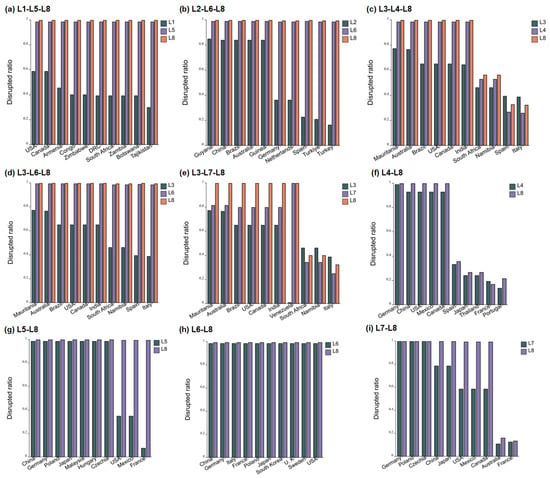

In multilayer automotive supply networks, the propagation of risk for a specific commodity can occur through nine distinct pathways: (copper–electrical and electronic parts–automotive), (aluminium–engines and parts–automotive), (iron–rubber and metal parts–automotive), (iron–engines and parts–automotive), (iron–miscellaneous parts–automotive), (rubber and metal parts–automotive), (electrical and electronic parts–automotive), (engines and parts–automotive), and (miscellaneous parts–automotive). Specifically, within a particular country, limitations in the supply of copper will initially lead to risk propagation within the copper layer of the supply network. Following this, the risks will extend to the electrical and electronic parts layer due to the hierarchical relationship between the copper layer and the electrical and electronic parts layer. Ultimately, the automotive layer will be influenced by the compromised nodes in the electrical and electronic parts layer. This situation is illustrated as the pathway (copper–electrical and electronic parts–automotive). In this context, the effects of risks instigated by various countries are assessed using the average disrupted ratio based on different threshold parameter settings for single-layer networks. Figure 11 displays the risk impacts initiated by the top ten countries across the various pathways.

Figure 11.

Impacts of risks triggered by the top ten countries in terms of a specific commodity following nine paths.

Figure 11a illustrates the effects of the top ten sources of risk along the pathway (copper–electrical and electronic parts–automotive). The findings indicate that restrictions in copper supply within the USA will cause disruptions in over 58% of countries at the copper layer, which will subsequently trigger disruptions in 98% and 99% of countries at the electrical and electronic parts and automotive layers, respectively. Besides the USA, other countries such as Canada, Armenia, Congo, Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Africa, and Zambia—who ranked highest for copper exports in 2023—will also contribute to significant disruptions in the electrical and electronic parts and automotive supply network layers. However, this does not imply that nations with high copper exports necessarily have a substantial influence on multilayer automotive supply networks. For instance, while Chile is the leading copper exporter, it ranks 14th regarding disruption impact within these networks. In contrast, Zambia, which has the fifth largest disruption size in the automotive supply network, only places 38th in terms of copper exports. This indicates that conventional methods often overlook the complex interdependencies among layers within multilayer automotive supply networks, potentially missing hidden vulnerabilities and underestimating the true impact of specific risk sources.

Furthermore, analysis of disruption propagation reveals asymmetric effects across network layers. As shown in Figure 11a–e, the increase in disruption ratio from the mineral resource layer to the intermediate component layer is markedly smaller than the amplification observed between the intermediate component layer and the automotive layer. This pattern suggests that disruptions experience exponential rather than linear magnification as they move upstream through the supply network. This difference primarily results from the robust structural connection between the layers of intermediate components and finished products. The disruption risks associated with the aluminum layer are somewhat more significant compared to those linked to the copper and iron layers. Notably, Venezuela exerts the most substantial influence on multilayer automotive supply networks when there are limitations on iron supply, resulting in a smaller range of disruptions within the iron layer, differing from the top nine countries shown in Figure 11e. Figure 11h demonstrates that the increase in disruption magnitude from the aluminum layer to the engines and parts layer is minimal, closely mirroring the similarly constrained increase from the engines and parts layer to the automotive layer. This pattern likely reflects the particularly strong interdependencies between the aluminum sector and engines and parts manufacturing, which may create more efficient risk absorption mechanisms compared to the relationships between other mineral resources and the engines and parts layer. Significantly, restrictions imposed by China and Germany on intermediate components lead to over 80% of the countries experiencing avalanches within both the intermediate component and automotive layers, as indicated in Figure 11f–i. Additionally, Asian nations, particularly China and Japan, exert greater influence on the electrical and electronic parts and miscellaneous parts layers than their North American counterparts, as shown in Figure 11g,i, which subsequently results in a larger disruption size in the finished product layer.

The progression of disruptions in pathways such as L1 → L5 → L8 (copper → electrical parts → automotive) demonstrates that the impact is exponentially amplified at each step. The increase in disruption ratio from the mineral layer to the intermediate component layer is markedly smaller than the jump from the intermediate layer to the automotive layer. This occurs due to cascade accumulation. A country disrupted in the copper layer may be a critical supplier to multiple countries in the electrical parts layer. When these downstream nodes fail, they collectively impact a wider set of nodes in the automotive layer than would be affected by the initial copper disruption alone. This non-linear amplification is a direct consequence of the multilayer structure, where a node’s failure in an upstream layer multiplies its impact on downstream layers.

The patterns in Figure 11 reveal “hidden risks” not apparent from single-layer analysis. For instance, the significant impact of the USA in the L1 → L5 → L8 pathway, despite a moderate disruption ratio in the copper layer (L1), is due to its strategic position in the cross-layer dependency network. The US supplies copper to key producers in the electrical parts layer (L5). The failure of these specific, highly connected L5 nodes then triggers a massive cascade in the automotive layer (L8). This mechanism shows that a node’s multilayer systemic risk is not simply its centrality in one layer, but its role in supplying critical inputs to highly central nodes in dependent downstream layers. This explains why traditional metrics can underestimate risk.

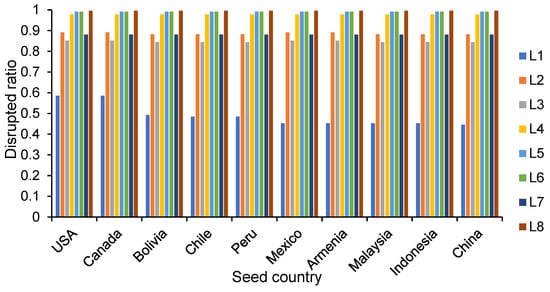

Extreme events can cause widespread supply constraints that affect all commodities within a specific country. To address this scenario, disruption risk spread is modeled according to the methodology outlined in Section 3.4, as such events represent critical risks that cannot be overlooked. When these disruptions occur, exports of all commodities within multilayer automotive supply networks to the affected country are severely curtailed. These supply shocks propagate simultaneously through each individual layer of the supply network. The interdependencies between layers—both at preceding and subsequent stages—amplify the disruptions as they cascade through the network. Consequently, the disruption magnitude in any given layer reflects not only the direct impact of supply constraints on that layer’s designated commodity, but also the cumulative effects from all upstream disruptions.

Figure 12 highlights the primary risk sources and their impacts on various layers within multilayer automotive supply networks. The ten most significant risk sources for the automotive industry encompass resource-rich countries like Chile and Mexico, along with technologically advanced nations such as China and the USA. Although these ten primary risk sources exert comparable effects on the iron, rubber and metal parts, electrical and electronic parts, engines and parts, miscellaneous parts, and automotive layers, they significantly differ in their influences on other layers. Moreover, the automotive industry’s heavy reliance on mineral resources is underscored by the substantial impacts from resource-rich nations (namely Chile and Mexico), which surpass even those from China. Consequently, advancing technologies for novel materials and reducing reliance on traditional mineral resources is vital. Geographically, North American nations—particularly the United States, Canada, and Mexico—play pivotal roles in maintaining the resilience of multilayer automotive supply networks. Supply constraints in the USA and Canada would likely trigger significant disruptions across all network layers, making stable exports from these countries essential for the smooth functioning of multilayer automotive supply networks.

Figure 12.

Impacts of shocks triggered by the top ten countries for all commodities.

The resulting disruption ratios are severe because this scenario triggers synchronized failures. A country like the USA or China is not just a major supplier in one layer but in several critical layers concurrently. The failure of such a multiplex hub removes capacity from multiple points in the production network at once, overwhelming the system’s redundancy and buffering capabilities. The disruption propagates not only sequentially along pathways but also in parallel, leading to a systemic collapse that is far more severe than the failure in any single layer.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

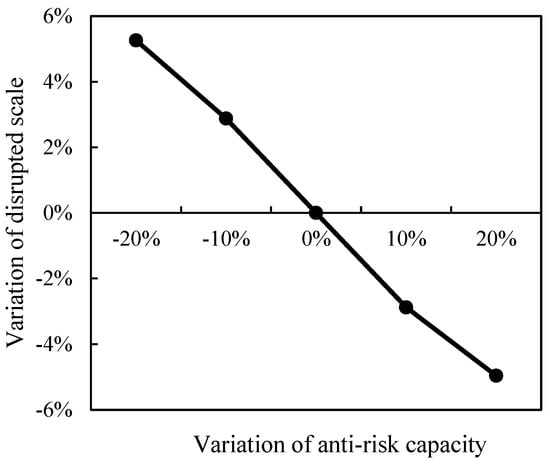

To assess the robustness of the multilayer network’s resilience and to quantify the marginal utility of investments in nodal preparedness, a sensitivity analysis was conducted on the core model parameter, the anti-risk capacity (θ). This parameter represents a node’s intrinsic threshold to absorb supply shocks before failure. The analysis systematically varied θ by ±20% from its calibrated baseline and measured the corresponding percentage change in the total system-wide disruption scale, defined as the proportion of nodes ultimately failed in a cascade.

The results, presented in the accompanying Figure 13, reveal a pronounced and predominantly linear negative relationship between a network’s aggregate anti-risk capacity and its overall disruption scale. A 20% reduction in the anti-risk capacity parameter precipitates a significant 5.26% increase in total disruption. Conversely, a commensurate 20% enhancement in capacity yields a substantial 4.96% reduction in disruption scale. The response is notably symmetric, indicating that the system’s vulnerability is equally sensitive to improvements and deteriorations in resilience.

Figure 13.

Sensitivity analysis of anti-risk capacity in the multilayer supply networks.

6. Discussion and Policy Implications

This study’s findings offer valuable insights for both the automotive sector and policymakers in various nations engaged in multilayer automotive supply networks, aiming to foster stable growth from a systemic viewpoint. The analytical framework presented here demonstrates how a multilayer network model can effectively represent and analyze global supply networks for specific industries. The primary implications can be summarized into seven key points.

6.1. Identification of Multiplex Hubs

The static analysis identifies China, the USA, and Germany as pivotal hubs within the multilayer network, as evidenced by their high multilayer degree and strength centrality (Figure 8 and Figure 9). This contrasts with the profile of nations like Japan and the United Kingdom, which, despite their significance in single-layer automotive trade, occupy a less central role in the multiplex structure. This discrepancy demonstrates that single-layer analysis fails to capture the full complexity of a country’s systemic importance, which is derived from its influential position across multiple, interdependent commodity layers.

Policymakers should prioritize establishing multilateral stability agreements specifically with China, the USA, and Germany. These agreements should focus on joint stress-testing of cross-layer dependencies, coordinated strategic stockpiling of critical components, and enhanced information sharing. This approach creates a “first line of defense” around the most systemically critical nodes, moving beyond bilateral trade agreements to multilayer resilience pacts.

6.2. Regional and Industrial Disparities in Risk Sources

Critical risk sources exhibit distinct regional and industrial characteristics within single-layer supply networks. Table 2 reveals that supply constraints from key countries across Africa and the Americas—including Canada, Bolivia, Chile, Guyana, Brazil, and Mauritania—create significant vulnerabilities in copper, aluminum, and iron supply networks, leading to cascading disruptions across multiple industries. In contrast, supply restrictions from several industrialized nations, such as Japan, the United States, China, and Germany, have substantial effects on the intermediate component (including rubber and metal parts, electrical components, engines, and miscellaneous parts) and finished product (automobiles) supply networks.

Resource-rich countries should focus on diversifying their export markets and investing in infrastructure stability to avoid becoming single points of failure. Industrialized nations, conversely, should prioritize supply chain mapping, supplier diversification, and fostering domestic production capabilities for critical intermediate goods to mitigate the impact of upstream shocks.

6.3. Non-Linear Effects of Anti-Risk Capacity

Enhancing a nation’s capacity to withstand supply chain risks across the eight single-layer networks produces two distinct effects on network vulnerability. As illustrated in Figure 10, changes in risk magnitude—triggered by varying threshold parameters in different countries—exhibit contrasting trends that reveal the complex nature of supply chain interdependencies. Domestic production capacity plays a critical role in risk mitigation, particularly in the automotive sector. Boosting domestic production of automotive-related goods proves essential for strengthening resilience against disruptions from reduced international trade. This relationship highlights how a nation’s anti-risk capabilities can have divergent effects on single-layer network stability, offering valuable insights for developing cost-effective systemic risk mitigation strategies. The copper supply network exemplifies these dynamics clearly. For countries with low ratios of domestic copper production to imports, increasing exploration and utilization of domestic copper resources can significantly enhance network resilience. Conversely, decreased domestic production ratios for rubber, metal components, electrical parts, engines, miscellaneous components, and automotive imports in key supplier countries noticeably weaken the robustness of their respective supply network layers.

Governments and industry bodies should establish and incentivize baseline resilience standards focused on achievable improvements in inventory management and multi-sourcing, particularly for sectors showing high sensitivity. For sectors like aluminum and iron, more significant support, such as tax incentives for capital investment, may be necessary. This ensures public and private resources are allocated for maximum systemic benefit.

6.4. Existence and Impact of Hidden Risks

It is crucial to take certain hidden risks within multilayer automotive supply networks seriously. Figure 11 highlights the primary risk sources across nine propagation paths under supply constraints on specific commodities. Various hidden risk factors emerge when considering the complex interdependencies between upstream and downstream layers. For example, while the USA has a minimal effect on the iron supply network during supply restrictions, its influence amplifies through intricate connections with intermediate components. This cascading interaction ultimately affects the greatest number of countries in the finished product sector, particularly automobiles. Similarly, as illustrated in Figure 12, limited export routes in resource-rich developing nations such as Chile and Peru can significantly impact finished product manufacturing, especially automotive production. These critical risk sources often remain hidden from conventional static analysis methods, creating blind spots in supply chain risk assessment.

Regulatory frameworks should require major automotive manufacturers to map their supply chains beyond tier-1 suppliers and conduct regular stress-test simulations based on multilayer network models. This would force the proactive identification and mitigation of hidden risks before they trigger system-wide failures, shifting the focus from reactive crisis management to proactive vulnerability detection.

6.5. Necessity of Coordinated Governance

The intricate nature of multilayer supply networks, especially in the automotive industry, means that disruptions in one region can ripple through the entire system. Uncoordinated policies can lead to inefficiencies or even exacerbate systemic fragility. This complexity necessitates a coordinated approach among various stakeholders, including governments, industries, and international organizations.

Policymakers must actively seek to align national strategies within international frameworks. This includes collaborative efforts to develop common standards for supply chain transparency, sustainability, and resilience. International agreements can facilitate more robust and responsible sourcing of materials, creating a cohesive global approach to mitigating systemic risk.

In conclusion, the empirical findings of this study dictate an integrated policy approach that is fundamentally different from traditional, reactive supply chain management. The recommendations—ranging from tiered international partnerships and role-based strategies to mandatory due diligence and international coordination—are logically interlinked components of a systemic resilience strategy. They collectively address the core insight that the vulnerability of the automotive industry is a networked phenomenon, requiring a networked solution. By adopting this evidence-based framework, policymakers and industry leaders can transition from managing discrete crises to building enduring, systemic resilience.

7. Conclusions

This study has addressed a critical gap in supply chain risk analysis by developing a multilayer network framework for the global automotive industry. Prior research, predominantly reliant on single-layer network models, has consistently underestimated systemic risks by failing to capture the complex interdependencies among mineral resources, intermediate components, and finished products. Our analysis, integrating both static topology and dynamic propagation perspectives, demonstrates that a country’s true systemic risk is not a function of its importance in any single layer but emerges from its position and influence across the entire multiplex structure.

First, modeling the multilayer system. Our integrated static and dynamic analysis confirm that the automotive supply network is an intrinsically multiplex system. The framework successfully models eight interconnected commodity layers, revealing that the system’s true risk profile emerges from the interplay between these layers, not from their isolated properties. This architecture fundamentally differs from single-layer representations.

Second, quantifying multidimensional importance. Our static multilayer centrality analysis demonstrates that a country’s systemic risk is a function of its cross-layer positioning and influence. The principal findings reveal that China, the United States, and Germany function as pivotal hubs whose importance is derived from their roles across multiple layers. Their disruption would have cascading effects far exceeding single-layer predictions. Conversely, nations like Japan and the United Kingdom exhibit a different, more nuanced risk profile when their roles across all commodity layers are considered, highlighting the limitation of aggregate or single-layer metrics.

Third, uncovering cross-layer propagation. The dynamic simulations explicitly map how risk transmits across layers. They uncover hidden vulnerabilities, demonstrating how seemingly minor disruptions in upstream mineral layers are non-linearly amplified through intermediate component layers, leading to severe downstream impacts. This identifies the specific cross-layer dependency pathways that act as primary risk amplifiers, a phenomenon invisible to single-layer analysis.

The implications of this research are twofold. For policymakers and industry managers, the findings provide a strategic tool for moving from reactive crisis management to proactive resilience building. The analytical framework enables the identification of critical leverage points, suggesting that efforts should be prioritized towards diversifying sources for high-cascade-potential commodities and fortifying the specific cross-layer pathways that link upstream suppliers to downstream manufacturers.

Despite these contributions, this study has limitations that chart a clear path for future research. The reliance on country-level trade data, while providing a crucial macro-level perspective, aggregates the complex activities of individual firms. Future work should integrate firm-level data to model intra-national supply networks, offering a more granular understanding of risk propagation. Secondly, the current risk propagation model, though effective, employs a simplified linear threshold mechanism. Incorporating more complex, stochastic elements or agent-based behaviors that reflect real-world decision-making (e.g., panic buying, contractual renegotiation) would enhance the model’s realism. Finally, expanding the model to encompass a broader range of commodities and incorporating financial and informational flow layers would create a truly comprehensive multiplex simulation of supply chain crises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y. and Q.Z.; methodology, X.Y.; software, X.Y.; validation, X.Y. and Q.Z.; formal analysis, X.Y. and Q.Z.; resources, X.Y.; data curation, X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Y.; writing—review and editing, Q.Z.; visualization, Q.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hubei Province (24Q109) and the Research Program of Wuhan Polytechnic University (2024Y35 and 2024RZ086).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Commodities’ code of the multilayer automotive supply networks.

Table A1.

Commodities’ code of the multilayer automotive supply networks.

| Automotive | Group Description | HS/SITC Code | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral | Copper | HS Code 2603 | Copper ores and concentrates |

| Aluminium | HS Code 2606 | Aluminium ores and concentrates | |

| Iron | HS Code 2601 | Iron ores and concentrates | |

| Intermediate components | Rubber and Metal Parts | SITC Code 6251 | Tyres, pneumatic, new, of a kind used on motor cars (including station wagons and racing cars) |

| SITC Code 62551 | Tyres, pneumatic, new, other, having a herring-bone or similar tread | ||

| SITC Code 62559 | Tyres, pneumatic, new, other | ||

| SITC Code 62591 | Inner tubes | ||

| SITC Code 62592 | Retreaded tyres | ||

| SITC Code 62593 | Used pneumatic tyres | ||

| SITC Code 62594 | Solid or cushion tyres, interchangeable tyre treads and tyre flaps | ||

| SITC Code 69915 | Other mountings, fittings and similar articles suitable for motor vehicle | ||

| SITC Code 69961 | Anchors, grapnels and parts thereof, of iron or steel | ||

| Electrical and Electric Parts | SITC Code 76211 | Receivers, radio-broadcast, not capable of operating without an external source of power… incorporating sound-recording or reproducing apparatus | |

| SITC Code 76212 | Receivers, radio-broadcast, not capable of operating without an external source of power… not incorporating sound-recording or reproducing apparatus | ||

| SITC Code 77812 | Electric accumulators (storage batteries) | ||

| SITC Code 77823 | Sealed-beam lamp units | ||

| Engines and Parts | SITC Code 71321 | Reciprocating internal combustion piston engines for propelling vehicles, of a cylinder capacity not exceeding 1000 cc | |

| SITC Code 71322 | Reciprocating internal combustion piston engines for propelling vehicles, of a cylinder capacity exceeding 1000 cc | ||

| SITC Code 71323 | Compression-ignition internal combustion piston engines (diesel or semi-diesel) | ||

| SITC Code 77831 | Electrical ignition or starting equipment of a kind used for spark-ignition or compression-ignition internal combustion engines | ||

| SITC Code 77833 | Parts of the equipment of heading 778.31 | ||

| SITC Code 77834 | Electrical lighting or signalling equipment (excluding articles of subgroup 778.2) | ||

| Miscellaneous Parts | SITC Code 7841 | Chassis fitted with engines, for the motor vehicles of groups 722, 781, 782 and 783 | |

| SITC Code 78421 | Bodies (including cabs), for the motor vehicles of group 781 | ||

| SITC Code 78425 | Bodies (including cabs), for the motor vehicles of groups 722, 782 and 783 | ||

| SITC Code 78431 | Bumpers and parts thereof, of the motor vehicles of groups 722, 781, 782 and 783 | ||

| SITC Code 78432 | Other parts and accessories of bodies (including cabs), of the motor vehicles of groups 722, 781, 782 and 783 | ||

| SITC Code 78433 | Brakes and servo-brakes and parts thereof, of the motor vehicles of groups 722, 781, 782 and 783 | ||

| SITC Code 78434 | Gearboxes of the motor vehicles of groups 722, 781, 782 and 783 | ||

| SITC Code 78435 | Drive-axles with differential, whether or not provided with other transmission components | ||

| SITC Code 78436 | Non-driving axles and parts thereof, of the motor vehicles of groups 722, 781, 782 and 783 | ||

| SITC Code 78439 | Other parts and accessories, of the motor vehicles of groups 722, 781, 782 and 783 | ||

| SITC Code 82112 | Seats of a kind used for motor vehicles | ||

| Finished product | Automotive | HS Code 8702 | Vehicles; public transport passenger type |

| HS Code 8703 | Motor cars and other motor vehicles principally designed for the transport of persons | ||

| HS Code 8704 | Motor vehicles for the transport of goods |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Density

The density of a graph is the ratio of actual to potential network edges and an indicator reflecting the tightness of the network. It is computed as follows: