Abstract

The aim of this research is to develop a preliminary causal loop diagram (PCLD) of the tacit knowledge (TK) provisioning in a firm, from the knowledge-based human resource management (KB-HRM) perspective, which facilitates understanding phenomenon dynamics for designing strategies that ensure attraction, retention, and exploitation of TK. This research is qualitative and exploratory, conducted in two phases. In the first phase, we identified variables and KB-HRM processes involved by reviewing relevant documents from Web of Science to create a PCLD. The second phase involves designing this diagram. Findings suggest positive and negative interactions that favour and disfavour TK provisioning. Thus, organisational innovation is essential, requiring knowledge, particularly TK, and indispensable HR participation, as they possess and generate this knowledge. The diagram’s novelty is based on causality between twenty-three variables, grouped into three systems: (S1) acquisition of new TK, (S2) acquisition of existing TK, and (S3) loss of TK; and six KB-HRM-related processes. Therefore, PCLD presents the first step towards understanding TK provisioning complexity, as knowing TK inflows and outflows is crucial for firms to make better decisions and formulating strategies related to TK acquisition and retention.

1. Introduction

From a knowledge-based perspective, a firm’s competitive advantage depends on its ability to explore and exploit knowledge. The latter is considered a valuable, inimitable, scarce, and irreplaceable strategic resource that must be created, shared, and systemised [1]. Enterprises that seek to expand this resource are seen to generate better knowledge by increasing their diversity, which allows them to create combinations of knowledge [2], and to be more competitive. Managing inflow and outflow of knowledge in a firm is fundamental [3], particularly tacit knowledge (TK), as a critical enabler of organisational innovation [4]. Organisational innovation requires TK and active participation of people who contribute to the organisation, the so-called human resources (HRs). Indeed, they possess, regardless of hierarchical level, the ‘knowhow’, ‘know-what’, ‘know-why’ and ‘care-why’ [1].

Human resource management (HRM) in a firm is an important key enabler to promote organisational innovativeness. From a knowledge-based (KB) perspective, the knowledge-based HRM (KB-HRM) supports the processes of creation, sharing, and utilisation of knowledge in a firm [4]. Notably, KB-HRM is no longer focused on only filling vacant positions, monitoring job performance, and meeting short-term financial targets, but also on providing knowledge and capabilities to the enterprise, motivating knowledge generation and transfer, and ensuring opportunities for knowledge use [4,5].

Therefore, KB-HRM is considered to impact positively on a firm’s competitiveness and performance [4,6]; however, one current problem that firms face is loss of TK, caused by the absence or insufficiency of KB-HRM processes [6]. As a result, it is a challenge for firms to exploit TK held by HR in a timely and appropriate manner because it is implicit, and hard to communicate and formalise [7].

TK loss can have a negative impact on innovativeness, productivity, and competitiveness. Consequently, it is important to address organisational culture and structure, to design efficient and effective KB-HRM strategies and processes for knowledge management [6]. Particularly, it is key to understand and to monitor TK inflows and outflows, as well as barriers to effective knowledge transfer and retention [6,8,9]. Undoubtedly, acquisition and absorption of timely knowledge for a firm are a complex issue.

Therefore, considering knowledge is the fundamental resource for innovation [10], possessed by organisations and created by HRs that shape them [4,11], the following question arises from a KB-HRM perspective: what are the causalities between the variables involved in TK provisioning? Given the lack of empirical evidence on this topic, the aim of this research is to develop a preliminary causal loop diagram of TK provisioning in a firm, from a KB-HRM perspective, which facilitates understanding of phenomenon dynamics for designing strategies that ensure attraction, retention, and exploitation of TK.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.1.1. Tacit Knowledge

Knowledge is considered to drive the ability to take effective action, as it is conceived as a justified notion derived from a combination of grounded intuition, individual experience, contextual information, values, and expert insight [1,12]. Viewed as an organisational resource, knowledge differs from others because once it is generated, it can be combined and continuously recontextualised to give rise to new knowledge [13]. In a learning organisation, TK acquisition is fundamental [1]. Michael Polanyi [12] is a pioneering author who wrote about the tacit dimension of knowledge. He argues that this type of knowledge is related to people’s skills and is acquired through practice. TK is generated alongside perception gained through the senses and evolves through an individual’s life experiences. It is transmitted through socialisation and can be transformed into explicit knowledge—meaning formal and systematic—through a process known as externalisation [1].

Knowledge within a company exists in both tacit and explicit forms. TK is held by individuals and encompasses beliefs, mental models, and practical skills, while explicit knowledge is organised, structured, and readily available through formal organisational methods and procedures [1,12]. The main distinction between both, is that TK is incorporated and wordless, while explicit knowledge is codified using natural language. TK highlights a person’s ability to learn practically and apply that learning to achieve personal goals [14]. HR are not only capable of processing information, but also of generating knowledge [15]. By creating new knowledge, HR contributes to personal growth and company’s reinvention [1]. It is important to recognise that knowledge can be represented in various ways and results from multiple processes and interactions among individuals [1,12].

When HR professionals interact, they share and acquire knowledge, often returning with more TK than they originally possessed [16]. This transfer of knowledge is influenced by various factors, including cooperation (process of group interaction), conflict (ideas, actions, or strategies that oppose organisational objectives), and avoidance (protective attitudes of individuals or groups) [17]. These elements significantly impact on HR interactions effectiveness, whether among co-workers, subordinates, or leaders [18]. Individuals often possess more knowledge than they can verbally express or may be unaware of their own knowledge [12]. Nonetheless, TK plays a vital role in maintaining an organisation’s structure and coherence by being integrated into its routines [19].

1.1.2. KB-HRM and Knowledge Transfer

KB-HRM focuses on recognising and developing TK that HRs possess, as well as contributing to its sharing for benefiting the firm [4]. Knowledge transfer involves transmitting and absorbing knowledge; undoubtedly, for knowledge to benefit or be useful to the firm, it must be accessed and disseminated [1], so there must be systems that help to capture and motivate knowledge dissemination, such as KB-HRM, whose main objective is to maximise knowledge [20] through attracting, selecting, positioning, retaining, and transforming workers who possess the most valuable resource for the firm’s innovation: TK [21]. In practice, it is difficult to focus KB-HRM only on TK. Even though TK differs from explicit knowledge, they complement each other.

1.1.3. KB-HRM Processes

TK is inherent to people [1,12,14], so all KB-HRM processes are fundamental to TK provisioning. The recruitment process is key to identifying and attracting potential HRs [5] who possess knowledge required by the firm. The selection process identifies a candidate who possesses both (relevant) knowledge and skills (mainly creativity and collaboration) demanded by the firm and a potential to learn knowledge necessary for innovation (learning capacity). Hence the importance of recruiting talented people [3,4,21,22]. Therefore, recruitment and selection processes are determinants for a firm’s TK provisioning [4] and for improving knowledge-sharing behaviour, as people possess knowledge of other firms [3]. It should be noted that TK acquisition is seen as an alternative to overcome organisational inertia or alignment [23].

The performance management process is relevant for directing HR behaviour [5], an essential step in HR development [24]. Furthermore, it serves as feedback to motivate them to work innovatively and take advantage of opportunities for learning [22]. This is crucial for TK acquisition. A knowledge-based performance appraisal approach values participation and contribution in firms’ knowledge process.

Training and development process aims to optimise HR knowledge and skills. This contributes to the overall knowledge process within the organisation, as it helps to regulate and enhance HR knowledge and experience in a holistic manner [21].

Reward management process enhances knowledge process by offering tangible rewards (such as remuneration and benefits) and intangible rewards (such as a supportive work environment and opportunities for learning and development) [25]. Research by Chen and Huang [26] has shown that remuneration serves as an incentive for HR to generate current ideas and share their knowledge.

The labour relations process is centred on ensuring HR occupational well-being. A labour contract outlines working conditions such as wages, occupational health, safety, working hours, and training, as well as rights and responsibilities of the firms and employees [27]. For KB-HRM, labour contracts serve as a legally binding framework and are an important formal control mechanism that supports knowledge process [9,28].

Job design process involves defining job duties and requirements [5] based on firms’ needs and perspectives. This process is essential for knowledge management, as it identifies knowledge and skills required for filling a position. Job information is crucial for all KB-HRM processes.

Ultimately, KB-HRM processes aim to create long-term psychological bonds between the firm and its employees, aligning their goals to preserve organisational knowledge [29]. Recruiting and retaining competent as well as committed HRs favours TK stock for organisational innovation.

1.2. Theories and Methodologies Support

Knowledge creation theory posits that generating knowledge is a behaviour or mindset centred on sharing personal knowledge with others. In this context, each employee in the firm is regarded as a HR, possessing TK and ability to create new knowledge. This theory suggests that a firm’s success hinges on its ability to acquire and maintain knowledge, which facilitates collective use of this knowledge by its HR for continuous innovation [1].

Knowledge theory and a resource-based view (RBV) recognise that knowledge is essential for a firm’s competitive advantage [10]. Consequently, both approaches emphasise the importance of developing organisational capabilities—such as systems, processes, structures, and culture—to preserve a firm’s knowledge assets and human capital [6]. RBV highlights that TK is a critical resource that significantly contributes to innovation [10]. Additionally, it asserts that TK is a valuable, limited, non-substitutable, and hard-to-imitate resource vital for firm performance and their competitive advantage [30].

1.3. Previous Research

Based on a literature review conducted in Web of Science (WoS), there is a substantial number of publications addressing topics of knowledge and HR. However, when these two topics are combined, there is a significant decrease in the number of existing documents, particularly regarding TK or knowledge acquisition within organisations. According to retrieved documents, HRM role of facilitating TK exchange within organisations includes promoting a knowledge-based organisational structure and culture, as well as preventing loss of TK [6]. Furthermore, it highlights the relationship between HR slack and firm performance, which is influenced by factors such as knowledge accumulation (firm age), workforce size, hours worked, and salaries [31]. It is important to note that no literature was found that addresses the issue of TK from a systemic perspective to measure or propose a model.

Studies on HR and knowledge can be categorised into three main groups based on their objectives. The first group focuses on research that examines HRM impact and knowledge management on a firm’s effectiveness and performance (for example, ref. [32]). In the second group, research focuses on KB-HRM, emphasising exchange or transfer of KB-HRM (for example, ref. [24]). Studies in the third group concentrate on fostering innovation and knowledge [4,21] by managing HR flexibility [33], and developing learning capabilities [30].

Research on knowledge often has a limited focus, particularly in knowledge sourcing. Many studies investigate how firms perform and innovate based on their acquisition of knowledge, with personnel recruitment being a key factor [23]. In examining knowledge and system dynamics, it has been found that these studies typically analyse knowledge transfer within organisations. They consider fundamental mechanisms such as job rotation, communities of practice, mentoring systems, and documentation [13]. These studies emphasise the importance of technology management and knowledge management in facilitating innovation. Furthermore, they address knowledge sharing and transfer in a digital age [34] and explore cross-border knowledge search [2].

In addition, some findings of the literature review are variables related to TK provision, and those variables can be classified into two categories based on their impact. The first category encompasses factors related to new TK acquisition, including hiring practices [35], HR slack [31], HR expertise [36], HR formal education [37], organisational structure [6,38], and organisational culture [6,38,39]. The second category considers factors associated to interchange knowledge processes that lead to new TK, such as knowledge management [38,39], organisational leadership [39], engagement [11,40,41], teamwork [42], job rotation [35], co-workers trust [11,40,41,42], interfunctional conflict [40], knowledge hiding [20], communication/dialogue [40,42,43,44], learning motivation [38,39,44,45], reflexivity [43], digital technology [38,39,45], training [35], and external knowledge [46]. These factors play a crucial role in effective, new TK acquisition.

To overview, most research on TK is more qualitative than quantitative; findings suggest that KB-HRM contributes significantly to innovation and performance in firms. While addressing HRM impact on knowledge process [4], there is a lack of empirical evidence from studies focused on examining causality of TK provisioning in firms [47].

2. Materials and Methods

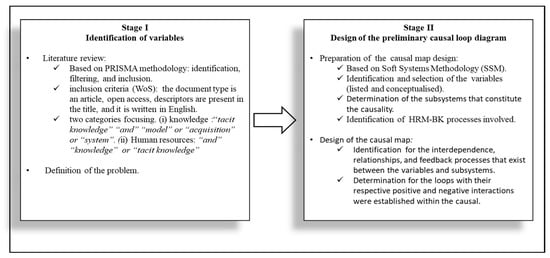

Exploratory qualitative research [48] is used to understand TK dynamics in a firm’s context, from its interrelationships with KB-HRM processes [4]. This research was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, variables are identified to configure PCLD and KB-HRM processes involved. The second phase involves designing this diagram. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodology for PCLD design. Own elaboration.

2.1. Phase I: Variables Identification

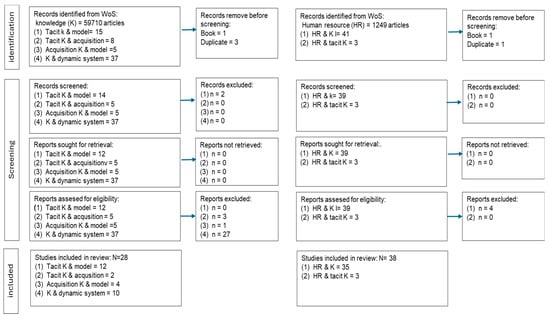

The collection and identification of variables began with a systematic approach for selecting and including documents from WoS. This database was used because it is one of the most comprehensive and rigorous in terms of content, as well as for its functional aspects that facilitate research. Three steps were followed, outlined by Page et al. [49]: (i) identification, (ii) filtering, and (iii) inclusion. The review applied five inclusion criteria: (a) document type is an article, (b) it is open access, (c) descriptors are present in the title, (d) it is written in English, and (e) publication date of all years. Exclusion criteria were applied to documents that did not meet inclusion criteria, as well as those deemed irrelevant to this study’s objective, mainly because it corresponds to another field of study. To streamline search, classification, and review of documents, this literature review was divided into two categories: the first category includes documents focusing on knowledge, while the second category encompasses studies examining knowledge from a HR perspective. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Literature review on knowledge and human resources. Based on PRISMA methodology [49].

For the first category, the key descriptor is “knowledge”, and we identified 59,725 registers. For search specification, the key descriptor was combined, separately, with 3 other descriptors: The first combination added “and” and descriptor “tacit”, and 188 articles were identified. To refine the search, “model” was added, 15 registers were found, and after the filtering stage, 12 articles were included. For the second category, the 3 descriptors previously mentioned were combined with “and” and “acquisition”, and 8 registers were identified, from which 3 were excluded because of duplicity and 3 because of eligibility. Therefore, only 2 articles were included for review. During third category, “and” and “acquisition” were combined, resulting in 578 registers, and the search was refined, using descriptor “model”, identifying 31 registers. It is important to mention that, after a superficial review of the identified documents, there were articles not related to the field of this research. Thus, search was refined by category on WoS: management, business, economic, manufacturing engineering, industrial engineering, and multidisciplinary engineering, finding 5 registers that were recuperated. After eligibility evaluation, 4 articles were retained. Forth, a combination was configured with descriptors “system”, “and”, and “dynamic”, obtaining 37 registers. After evaluating eligibility, only 10 articles were considered for review. Finally, for the first category, a total of 28 studies were retained.

In the second category, key descriptor “human resource” was used, as well as acronym “HHRR”, and “or” and “HR”, and 1249 documents were identified. These articles were classified in WoS categories: management, business, economic, manufacturing engineering, industrial engineering, multidisciplinary engineering, and industrial relation. Then, for refining the search, they were combined with descriptor “and” and “knowledge”, and 41 registers were identified, excluding 1 because of duplicity, another 1 because it is a book’s chapter, and 4 because of irrelevance, so a total of 35 articles were included. Next, that descriptors combination was added to descriptor “and” and descriptor “tacit”, and 3 articles were identified and included for review. Finally, descriptors “and”, “model”, “or”, “measure”, “or”, and “Dynamic” were added, and this combination did not showed results. Thus, the second category has a total of 38 studies for review.

Once articles were retrieved, and three key aspects were identified: study’s objective, methodology used, and variables related to TK provisioning within firms. A summary of publications that include these variables are then compiled, leading to a clear definition of the problem.

2.2. Phase II: Design of a Preliminary Causal Loop Diagram

Thereafter, variables identified during the literature review were listed and conceptualised. From this list and empirically, those considered relevant for explaining TK procurement causality in the firm were selected. Subsystems that constitute this causality were established to categorise the variables. Additionally, KB-HRM processes involved were identified at this stage. This step involves analysing interdependence, relationships, and feedback processes that exist between variables and subsystems, based on the literature findings. Subsequently, loops with their respective positive and negative interactions were established within the PCLD.

3. Results

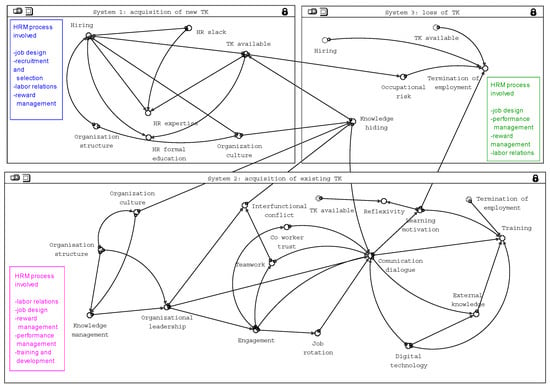

Based on variables identification and selection, a PCLD for TK provisioning in a firm is designed. This diagram illustrates causal variables and interrelationships that were considered key determinants for TK provision from a KB-HRM perspective. It includes a total of twenty-three variables, categorised into three systems: (S1) acquisition of new TK, (S2) acquisition of existing TK, and (S3) loss of TK. The KB-HRM processes involved and interacting with TK provisioning are job design, recruitment and selection, training and development, reward management, labour relations, and performance management [4,26]. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 provide additional details on these processes. Notably, these findings indicate that these variables can have positive and negative interactions. Thus, each variable can either facilitate or hinder TK provisioning. It is important to notice links between variables are bidirectional.

Table 1.

KB-HRM determinants and processes mediating new TK acquisition.

Table 2.

Determinant variables and KB-HRM processes involved in existing TK acquisition.

Table 3.

Determinant variables and HRM processes responsible for TK loss.

3.1. Stratification of KB-HRM Variables and Processes by System

Key variables constituting each system and involved KB-HRM processes are defined below.

3.1.1. System 1: New TK Acquisition

S1 is conceptualised as a system that favours entry of new TK into a firm; therefore, it integrated by KB-HRM processes (job design, recruitment and selection, labour relations, and reward management) and variables that influence new TK acquisition. See Table 1.

The relationship between variables in the S1 system are specifically described below, highlighting system complexity: Hiring (H) is considered to increase HR expertise (HRexp) and HR formal education (HRfe). About HR slack (HRs), H decreases but HRexp increases. The former, together with HRfe, increases the TK available (TKa). Meanwhile, organisational structure (Os) increases H and organisational culture (Oc). Oc also increases H and Os. Finally, TKa decreases H and increases Oc.

3.1.2. System 2: Existing TK Acquisition

The S2 system is designed to facilitate TK flow within a firm. It is established through KB-HRM processes (labour relations, job design, reward management, performance management, and training and development) and variables, which influence the existing acquisition of TK. See Table 2.

Specifically, interrelationships between variables of S2, are knowledge management (KM) positively affects leadership organisation (Lo), Lo favours engagement (E), and E increases teamwork (Tw), job rotation (Jr), and co-worker trust (CwT). Tw negatively affects interfunctional conflict (Ic) and favours E. Tw, Jr, and CwT favour communication/dialogue (C/D). C/D relates positively with E and Tw. Ic has a negative effect on Km, Lo, and E, and a positive effect on knowledge hiding (Kh), and Kh negatively affects C/D. C/D has a positive effect on Lo, CwT, learning motivation (Lm), training (T), external knowledge (EK), and TKa. Lm decreases termination of employment (Te) and increases reflexivity (R), and R positively affects TKa. Digital technology (Dt) favours C/D, T, and EK. T positively impacts C/D, Lm, and has a negative impact on Te. EK favours T. Os is positively related to Lo and KM, and also favours organisational culture (Oc). Lastly, TKa favours C/D and Oc.

3.1.3. System 3: Loss of TK

S3 system is characterised by its role in promoting TK outflow from a firm. Consequently, KB-HRM processes (job design, performance management, reward management, and labour relations) and related variables typically have a negative impact on available TK. It is important to identify these variables and HRM processes that contribute to TK loss. See Table 3.

Specifically, interrelationships between variables of S3 are occupational risk (Or) has a positive effect on termination of employment (Te), this (Te) increases H, and together with knowledge hiding (Kh), this reduces TKa, and TKa has a negative effect on Or. In the next section, a detailed description of interrelation among variables in S1, S2, and S3 is provided.

3.2. Integration of Procurement System: Causalities

Variable hiring is determinant for TK provision, as it increases HR expertise and HR formal education, which increases the base of available TK, and the firm’s possibility to benefit. Regardless of duration of employment relationship with HR, TK of each HR contributes in a particular way to a firm’s capabilities. It is considered that, through employment contracts, the firm prevents and controls TK provisioning [33].

TK availability within a firm positively influences the development of a knowledge-based organisational culture [3]. This culture promotes effective knowledge management, which, in turn, enhances organisational leadership and strengthens employee engagement. These improvements lead to better organisational communication and contribute to employee skills development [68] through practices such as teamwork, job rotation, and co-worker trust. Furthermore, social actions like dialogue and reflection facilitate individual learning. As employees gradually share their knowledge with the existing knowledge base, organisation benefits from this TK, encouraging others to learn through exchange and restructuring [32]. Consequently, dialogue plays a crucial role in knowledge creation and in fostering a collective understanding [1].

Teamwork, job rotation, and co-workers trust positively influence communication/dialogue. This promotes exchange, development, and preservation of TK available, leading to increased learning motivation and helping to prevent TK leakage [32]. As a result, there is a decrease in employee turnover, while also fostering reflexivity due to interdependence of tasks and shared cooperative goals [69].

TK availability positively influences communication and dialogue, which, in turn, increases organisational leadership, and co-worker trust. This increase in trust leads to greater engagement and vice versa. Therefore, effective communication is essential for fostering trust. Through dialogue, it becomes possible to reconcile different meanings among HRs. This interaction not only helps achieving work objectives but also enhances HR knowledge and skills. Trust is a prerequisite for TK exchange [10].

Thus, motivation to participate in TK exchange and to learn may depend on interactions between HR and ways for designing work. Additionally, organisational values regarding knowledge use play a crucial role. This highlights the importance of organisational culture and structure in facilitating TK sourcing, transfer, and application [6]. An emphasis on learning orientation within culture fosters firm’s intellectual capital [32], while organisational structure helps to coordinate knowledge-based behaviours through workflows, reporting lines, and interactions. These two variables positively influence each other, creating a reciprocal relationship that particularly affects factors such as hiring, knowledge management [6], and organisational leadership.

However, HR may be reluctant to share or exchange their TK [9], which can lead to negative feelings and tension, resulting in interfunctional conflict [40]. This conflict has been shown to promote knowledge hiding and negatively impact knowledge management, organisational leadership, and employee engagement. Therefore, fostering a positive organisational culture and teamwork is crucial, as these elements can help reduce interfunctional conflict. Engagement is particularly important, as it encourages positive perceptions among HR and fosters a sense of mutual understanding and collaboration [70].

This creates a potential reciprocity loop between teamwork and engagement, which may help to reduce knowledge hiding. For HR recipients and TK providers, engagement and co-workers trust are identified as intangible assets that could be transformed into tangible benefits for individuals and the organisation in the future [11]. Evidence indicates that HRM influences behaviours, attitudes, and motivation (e.g., refs. [22,71]), while also emphasising the importance of developing long-term working relationships between HR and the firm [29].

HR is undoubtedly a valuable part of a firm’s knowledge base [29]. However, when HR professionals engage in behaviours such as withholding information, distorting facts, fostering mistrust, and exhibiting hostility [59], the practice of knowledge hiding increases. This has a detrimental effect on communication/dialogue, and TK availability. Co-worker trust becomes essential, as it influences the level of TK shared throughout the organisation. Key HR personnel are likely to respond similarly to support they receive from their colleagues. If trust is lacking, a “distrust loop” may be created, leading HR professionals to withhold knowledge because others refuse to share their TK. In this context, organisational leadership plays a critical role in fostering collaboration among HR and enhancing their organisational commitment [41].

On the other hand, one key factor influencing TK procurement for the firm is training. Through training, HR acquire necessary knowledge, and develop their capacity to absorb, identify, transform, and exploit internal and external knowledge. This process fosters innovation and enhances firm’s performance while also potentially reducing termination of employment. Research suggests that training facilitates knowledge exchange, which in turn promotes communication and dialogue. Thus, training and knowledge exchange are crucial for HR to share and transfer their TK effectively. Specifically, training increases learning motivation, strengthens organisational structure, and enhances organisational leadership [72]. These factors collectively motivate the firm to further develop knowledge [35,65].

One important variable that positively influences training is external knowledge. This type of knowledge challenges traditional thinking within a firm, helps eliminate outdated or limited information, and inspires innovation. Expanding the knowledge base not only enhances creativity but also reduces rigidity within the organisation [46]. Additionally, a larger network of firms contributes to a more robust knowledge base. Therefore, the process by which a firm searches for and integrates knowledge across different bases and organisational boundaries is crucial to making TK available [34].

However, the most important aspect is that HR is motivated to seek and integrate external knowledge with internal knowledge to optimise processes and products [3]. Digital technology positively influences external knowledge, training, and communication/dialogue. It enables the firm to overcome geographical limitations, streamline information and knowledge flows, and to reduce operational and coordination costs [73]. These factors contribute positively to TK available.

Nonetheless, one of the factors that influences the TK loss available and increases hiring is termination of employment, which can occur due to several reasons such as limited-term contracts, dismissals, retirements, deaths, and incapacities. When TK is not present, it may lead to occupational risks; otherwise, its availability could be reduced. Clearly, a decline in TK can result in dysfunctions that may negatively affect the firm. This underscores the importance of an organisation’s ability to identify, mobilise, and promote HR knowledge while laying the groundwork for competitive strategies [74]. HR slack is thought to help maintain TK available. Although it incurs costs, it helps prevent valuable TK loss for the firm [31,75] and reduces hiring needs.

3.3. KB-HRM and Available TK

KB-HRM enhances available TK when its processes prioritise fostering creativity [20] and expands the firm’s HR learning and knowledge. This approach transforms HR into a renewable resource capable of generating new knowledge. Consequently, HR skills and behaviours significantly influence KB-HRM effects on HR outcomes [76].

KB-HRM processes are conceived as being involved in all systems that integrate firm’s TK provisioning. However, relevance of each process is more pronounced in specific systems due to their nature. For instance, in System 1 (S1), processes of job design, recruitment and selection, as well as labour relations and reward management, are crucial for acquiring new TK. In System 2 (S2), key processes for exchanging existing TK include labour relations, job design, reward management, performance management, training, and development. Finally, in System 3 (S3), processes that relate to TK loss include job design, performance management, reward management, and labour relations. KB-HRM processes design is intended to be flexible, creating an environment for feeding, using, and retrieving knowledge within HR [33].

This flexibility is crucial for ensuring KB-HRM to foster a connection between HR job satisfaction and knowledge-seeking behaviours [77]. HR willingness to share and receive knowledge is intricately linked to their level of engagement. This engagement facilitates developing new knowledge and competencies that are essential for a firm’s future. Finally, TK provisioning complexity is illustrated in a theoretical model presented in Figure 3, representing system variables to which it is integrated.

Figure 3.

Preliminary causal loop diagram of TK provisioning.

Two loops are visualised as follows: Loop 1 shows a process where knowledge enters, is shared, and is lost. This is a loop where the three systems are set together, and it involves all HRM processes. This loop is formed by variables: hiring (S1 y S3) → available TK (S1, S2 and S3) → organisation culture (S1 y S2) → knowledge management (S2) → organisational leadership (S2) → engagement (S2) → teamwork (S2) → communication/dialogue (from S2) training (S2) → employment termination (S2 and S3).

Loop 2 shows a TK communication process which is integrated by variables: communication/dialogue (S2) → training (S2) → learning motivation (S2) → reflexivity (S2) → available TK (from S1,S2 and S3) → knowledge hiding (S2) → interfunctional conflict (S2) → organisational leadership (S2) → engagement (S2) → co-worker trust (S2), where it can be observed that HRM processes are directly involved as follows: training and development labour relations, job design, reward management, and performance management.

3.4. Model’s Implications and Limitations

This proposed model adheres to TK provisioning policies of each firm, as these policies can influence a system’s functioning and objectives [78]. It is developed within an organisational culture that promotes continuous interactive learning, which supports knowledge absorption and application, as well as HR integration and collaboration [23]. Therefore, TK’s causal provisioning diagram is based on the premise that the firm has a knowledge base, enabling a better understanding of new knowledge and access to external information. This foundation can enhance a firm’s competitive advantage and create synergies through interaction of complementary knowledge.

However, this model does not account for variables such as knowledge accumulation, HR number, salaries, and working hours. Instead, it focuses on demonstrating certain variables and interrelationships identified in a literature review, along with additional relevant factors—such as those associated with S3—to help clarify dynamic behaviours of TK provisioning.

4. Discussion

TK procurement in a firm is influenced by the organisational context, which affects HR capacity to seek and integrate internal and external knowledge [79]. HR plays a crucial role, acting as users and providers in TK exchange processes. This exchange promotes collaboration, interaction, understanding, and coordination among HR within a firm [44]. Therefore, TK exchange is essential for building strong relationships and serves as a foundation for mutual learning. This learning is positively correlated with a capacity to absorb knowledge and TK availability, where reflection and dialogue are key components. So, knowledge sharing is considered a key process in knowledge management, due to its ability to change knowledge distribution in a firm, increasing knowledge entropy [80].

HRM in a knowledge context plays a crucial role in TK procurement. It moulds and guides HR behaviours, facilitating processes required for acquiring, and managing knowledge [6], enhancing performance at individual and organisational levels [22]. KB-HRM involves identifying, selecting, developing, and retaining HRs [71] who possess TK critical for the firm.

Through a systems approach, a better understanding of TK sourcing in a firm can be achieved [13]. Understanding TK provisioning complexities is essential to mitigate risks and costs associated to TK scarcity for firms [38]. However, a literature review reveals a limited number of studies that examine this topic from a systemic perspective. This research contributes to the literature by designing a PCLD of TK provisioning through KB-HRM lens, and the goal is to enhance our understanding of dynamics involved in TK provisioning and to inform development of strategies that promote TK attraction, retention, and effective use. This model highlights the TK inputs and outputs flow within an organisation.

It is important to note that among studies discussing TK and HRM, there is a scarcity of research that develops models illustrating TK flows. Most existing proposals focus on one or a limited number of variables that influence knowledge acquisition (e.g., [9], as well as knowledge sharing and acquisition [7,9,39,45,47,81])

PCLD of TK provisioning is based on relationships among twenty-three variables identified in a literature review. Additionally, it involves six KB-HRM processes [4]: job design, recruitment and selection, labour relations, reward management, training and development, and performance management. These processes are crucial for system’s functionality due to their significant impact on TK acquiring and managing within a firm [82].

Ultimately, the PCLD goal is to encourage a systemic perspective for understanding firms, enabling them to address their challenges through innovative thinking and learning [83]. One of the most significant risks firms face is a lack of sufficient knowledge, particularly concerning TK provisioning, which is essential for organisational innovation [1]. This challenge often involves considerable time and financial resources [38].

Limitations and Future Research

This research is a first theoretical approach to understanding TK provision complexity from a HRM perspective, and, therefore, has some limitations that could lead to a narrow understanding of the phenomenon due to limited number of variables considered in the PCLD. Furthermore, causal relationships are determined based on findings of reviewed literature, which requires further study of interaction and effect of each variable. Another limitation is that the diagram design does not consider organisational and contextual contingencies, which may well influence variables behaviour and HRM processes, causing contradictions or undesirable consequences for TK provision.

To address this, future research should involve a more comprehensive review of variables in publications not only from WoS but also from other repositories like Scopus. This would help to provide a broader perspective on the situation, in addition to changing some causes found. Additionally, future studies should focus on examining TK provisioning causality by characterising the firm and analysing each KB-HRM process. It would also be beneficial to measure effectiveness and costs associated with the phenomenon. In the future, it is proposed to further study duality of roles that TK can have, as a result and as a mechanism. Another proposed future study is to take into practice PCLD proposed in this study to ease TK dynamics understanding.

Due to knowledge management, complexity is not only limited to rational knowledge and rationality, and we propose in another future work to study proposed PCLD from a thermodynamic perspective of the theory of knowledge fields [80], because of dynamism observed on TK transformation processes into explicit knowledge, and vice versa. This could promote managers and leaders in a firm to act as organisational integrators, non-lineally, from all knowledge fields: rational, emotional, and spiritual, leading to a new work spirituality reflected in an organisational change and social corporate responsibility.

Undoubtedly, knowledge complexity leads to a deep descriptive analysis of knowledge entropy discerned in PCLD. Additionally, integrating chaos theory and system dynamics will widen results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.-E. and M.A.-F.; methodology, M.A.-F. and G.S.-E.; formal analysis, G.S.-E. and M.A.-F.; investigation, M.A.-F., G.S.-E., L.P.L.-R., B.G.-J. and M.F.-M.; data curation, G.S.-E., M.A.-F. and L.P.L.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.-F., G.S.-E. and L.P.L.-R.; writing—review and editing, supervision, M.A.-F., G.S.-E., L.P.L.-R., B.G.-J. and M.F.-M.; project administration, M.A.-F., G.S.-E., L.P.L.-R., B.G.-J. and M.F.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable; this study does not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable; this study does not involve humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analysed during this research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado, Unidad Profesional Interdisciplinaria de Ingeniería y Ciencias Sociales y Administrativas (UPIICSA), for facilities granted for this work. We also thank Sistema Nacional de Investigadoras e Investigadores del Conahcyt, Conahcyt postgraduate scholarship, and Programa de Estímulo al Desempeño Docente (PEDD), the Comisión de Operación y Fomento de Actividades Académicas (COFAA-IPN), as well as all participants in this research for their collaboration and willingness. Authors are grateful to editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments and discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCLD | Preliminary causal loop diagram |

| TK | Tacit knowledge |

| HR | Human Resource |

| KB-HRM | Knowledge-based human resource management |

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| RBV | Resource-based view |

| S1 | System 1 |

| S2 | System 2 |

| S3 | System 3 |

References

- Nonaka, I. La Organización Creadora de Conocimiento; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, Y. Research on the Differential Mechanisms of Knowledge Cross-Border Searching on Firms’ Dual Innovation in the Digital Context: Based on Simulation of System Dynamics Model. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 2493380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, A.; Dezi, L.; Gregori, G.L.; Mueller, J.; Miglietta, N. Improving innovation performance through knowledge acquisition: The moderating role of employee retention and human resource management practices. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianto, A.; Sáenz, J.; Aramburu, N. Knowledge-based human resource management practices, intellectual capital and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 81, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, S.; Morris, S. Administración de Recursos Humanos; Cengage Learning: CDMX, México, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Phaladi, M. Human resource management as a facilitator of a knowledge-driven organisational culture and structure for the reduction of tacit knowledge loss in South African state-owned enterprises. SA J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolino, L.; Lizcano, D.; López, G.; Lloret, J. A Multiagent System Prototype of a Tacit Knowledge Management Model to Reduce Labor Incident Resolution Times. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, F.L.; Semensato, B.I.; Prioste, D.B.; Winandy, E.J.; Bution, J.L.; Couto, M.H.; Bottacin, M.A.; Mac Lennan, M.L.; Teberga, P.M.; Santos, R.F.; et al. Innovation in the main Brazilian business sectors: Characteristics, types and comparison of innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 23, 135–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Song, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L. How does contract completeness affect tacit knowledge acquisition? J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 989–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Simulating the impacts of mutual trust on tacit knowledge transfer using agent-based modelling approach. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 17, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, M. The Tacit Dimension; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. System dynamics modelling for examining knowledge transfer during crises. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chergui, W.; Zidat, S.; Marir, F. An approach to the acquisition of tacit knowledge based on an ontological model. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 32, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, D.; Sensiper, S. The role of tacit knowledge in group innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1998, 40, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, N.M. Common Knowledge: How Companies Thrive by Sharing What They Know; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; 188p. [Google Scholar]

- Baumard, P. Tacit Knowledge in Organizations; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. On Organizational Learning; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2012; 480p. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.; Winter, S. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; 454p. [Google Scholar]

- Lugar, C.; Novićević, R. Knowledge based human resource management and employee creativity: The dual mediation of knowledge sharing and knowledge hiding. Econ. Ecol. Socium 2021, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tal, M.J.Y.; Emeagwali, O.L. Knowledge-based HR Practices and Innovation in SMEs. Organizacija 2019, 52, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Lepak, D.P.; Hu, J.; Baer, J.C. How Does Human Resource Management Influence Organizational Outcomes? A Meta-analytic Investigation of Mediating Mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1264–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B. Exploration of talent mining based on machine learning and the influence of knowledge acquisition. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Litvaj, I.; Drbúl, M.; Rasheed, M. Improving Quality of Human Resources through HRM Practices and Knowledge Sharing. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. Reward Management: A Handbook of Remuneration Strategy and Practice; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2007; 748p. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-J.; Huang, J.-W. Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance—The mediating role of knowledge management capacity. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIT. Informe Sobre el Diálogo Social 2022: La Negociación Colectiva en Aras de Una Recuperación Inclusiva, Sostenible y Resiliente; OIT: Ginebra, Suiza, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.H.; Liu, T. Knowledge transfer in buyer-supplier relationships: The role of transactional and relational governance mechanisms. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 78, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepak, D.P.; Snell, S.A. Examining the Human Resource Architecture: The Relationships Among Human Capital, Employment, and Human Resource Configurations. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 517–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, E.; Chadee, D.; Raman, R. Managing Indian IT professionals for global competitiveness: The role of human resource practices in developing knowledge and learning capabilities for innovation. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2013, 11, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecuona, J.; Reitzig, M. Knowledge worth having in “excess”: The value of tacit and firm-specific human resource slack. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 954–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Nhut, Q.; Quoc, T.V.; Xuan, N.N.A.; Le, D.V. Leveraging Knowledge Management to Enhance Human Resource Management Efficiency: Insights from Mekong Delta Service Enterprises. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 15, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Sanchez, A.; Vicente-Oliva, S. Supporting agile innovation and knowledge by managing human resource flexibility. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2023, 15, 558–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, H.; Cui, X.; Peng, X.; Udemba, E.N. Reverse knowledge transfer in digital era and its effect on ambidextrous innovation: A simulation based on system dynamics. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebal, M.; Ferdous, A.; Chambers, C. An integrated model of marketing knowledge—A tacit knowledge perspective. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2019, 21, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, D.; Popper, M. Tacit knowledge as a multilayer phenomenon: The ‘onion’ model. Learn. Organ. 2019, 26, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoene, M.A.; Buszko, A. Quantitative Model of Tacit Knowledge Estimation for Pharmaceutical Industry. Eng. Econ. 2014, 25, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, P.; Shahabipour, A.; Hosnavi, R. A model for assessment of uncertainty in tacit knowledge acquisition. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, M.; Khanachah, S. Provide a model for acquisition and recording of organizational lessons learned in the framework of the knowledge handbook with emphasis on effective components. Sigma J. Eng. Nat. Sci.-Sigma Muhendis. Ve Fen Bilim. Derg. 2024, 42, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.B.; Wittmann, C.M.; Hansen, J.D. A process model of tacit knowledge transfer between sales and marketing. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-P. To Share or Not to Share: Modeling Tacit Knowledge Sharing, Its Mediators and Antecedents. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, T.; Eckert, C.; Clarkson, P. Extemalizing tacit overview knowledge: A model-based approach to supporting design teams. Ai Edam-Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 2007, 21, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, K.; Conway, E.; Fu, N.; Bailey, K.; Kelly, G.; Hannon, E. Enhancing knowledge exchange and combination through HR practices: Reflexivity as a translation process. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-W.; Lin, J.-R. Knowledge sharing and knowledge effectiveness: Learning orientation and co-production in the contingency model of tacit knowledge. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2013, 28, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Nunes, J.M.B.; Ragsdell, G.; An, X. Somatic and cultural knowledge: Drivers of a habitus-driven model of tacit knowledge acquisition. J. Doc. 2019, 75, 927–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gao, H. How External Knowledge Acquisition Contribute to Innovation Performance: A Chain Mediation Model; Sage Open: London, UK, 2023; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska, W.; Erickson, G.S. Tacit knowledge acquisition & sharing, and its influence on innovations: A Polish/US cross-country study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 71, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass Inc. Pub: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; 346p. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.A. Using knowledge engineering to preserve corporate memory. In The Psychology of Expertise: Cognitive Research and Empirical AI; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 170–187. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Clasificación Internacional Normalizada de la Educación CINE Montreal: UNESCO. 2011. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000220782 (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Gürlek, M.; Gurlek, M. Knowledge management and human resources management. In Tech Development Through HRM; Emerald Publishing Limited: England, UK, 2020; 25p. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, B.; Sang, W.; Yang, J.; Ji, S.; Tang, Z. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Leadership on Employees’ Tacit Knowledge Sharing in Start-Ups: A Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. To Be Fully There: Psychological Presence at Work. Hum. Relat. 1992, 45, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.; Veloso, A.; Oliveira, A.; Silva, I. The influence of work engagement and trust in the tacit knowledge transfer: Proposal of a model. Estud. Gerenciales 2021, 37, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, T.; Khan, O.J.; Schnellbächer, B.; Heidenreich, S. Strategic accord and tension for business model innovation: Examining different tacit knowledge types and open action strategies. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 2050039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Zhao, M.; Calantone, R. Adding interpersonal learning and tacit knowledge to March’s exploration-exploitation model. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. A Matter of Trust: Effects on the Performance and Effectiveness of Teams in Organizations; Ridderprint: Lisboa, Portugal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit, F.R.; Greer, L.L.; Jehn, K.A. The paradox of intragroup conflict: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, C.E.; Zweig, D.; Webster, J.; Trougakos, J.P. Knowledge hiding in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukas, H. Do we really understand tacit knowledge? In Complex Knowledge: Studies in Organizational Epistemology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sinkula, J.M.; Baker, W.E.; Noordewier, T. A Framework for Market-Based Organizational Learning: Linking Values, Knowledge, and Behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacopoulou, E. The Dynamics of Reflexive Practice: The Relationship Between Learning and Changing. In Organizing Reflection; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.N.; Luh, D.B. A social network supported CAI model for tacit knowledge acquisition. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2018, 28, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeister, M.; Rodríguez-Castellanos, A. Knowledge acquisition, training, and the firm’s performance: A theoretical model of the role of knowledge integration and knowledge options. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-W.; Bathelt, H.; Zeng, G. Learning in Context: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Analyze Knowledge Acquisition at Trade Fairs. Z. Fur Wirtsch. 2020, 64, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOBMEX. Ley Federal del Trabajo; Ediciones Fiscales ISEF: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sveiby, K.; Simons, R. Collaborative climate and effectiveness of knowledge work—An empirical study. J. Knowl. Manag. 2002, 6, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtner, A.; Tschan, F.; Semmer, N.K.; Nägele, C. Getting groups to develop good strategies: Effects of reflexivity interventions on team process, team performance, and shared mental models. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 102, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, M.L.; Virick, M. Perceived Support, Knowledge Tacitness, and Provider Knowledge Sharing. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 717–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The Impact of High-Performance Human Resource Practices on Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, R.; Dysvik, A.; Kuvaas, B.; Nerstad, C.G.L. It Takes Three to Tango: Exploring the Interplay among Training Intensity, Job Autonomy, and Supervisor Support in Predicting Knowledge Sharing. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 54, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin, S.; Ho, T.C. Digital technology, digital capability and organizational performance: A mediating role of digital innovation. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2019, 11, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J. Development of a method for ontology-based empirical knowledge representation and reasoning. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 50, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, L.; Cai, S. Systems Dynamics Application to Motivating Tacit Knowledge Management. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing, Dalian, China, 18 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, C.; Kalshoven, K. How High-Commitment HRM Relates to Engagement and Commitment: The Moderating Role of Task Proficiency. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudawska, A. Commitment-based human resource practices, job satisfaction and proactive knowledge-seeking behavior: The moderating role of organizational identification. Manag. Bus. Adm. Central Eur. 2024, 33, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. Policy as a field of management theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1977, 2, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Von Krogh, G. Perspective—Tacit knowledge and knowledge conversion: Controversy and advancement in organizational knowledge creation theory. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Bejinaru, R. The Theory of Knowledge Fields: A Thermodynamics Approach. Systems 2019, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, H.; Khan, S.U.R.; Iqbal, J.; Akhunzada, A. A Tacit-Knowledge-Based Requirements Elicitation Model Supporting COVID-19 Context. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 24481–24508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, R.W.; McEvoy, G.M.; Beer, M.; Spector, B.; Lawrence, P.R.; Mills, D.Q.; Walton, R.E. Managing Human Assets. ILR Rev. 1984, 39, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P. Systems thinking. In Rethinking Management Information Systems: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.